Leslie Howard: Difference between revisions

Saratoga Sam (talk | contribs) →Theatre credits: Added wiki link and corrected title for "Peg o' My Heart"; pointed "The Wren" to a wiki link rather than IBDb and added new cite |

|||

| (652 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|British actor (1893–1943)}} |

|||

{{Other people|Leslie Howard}} |

|||

{{other people}} |

|||

{{Use British English|date=October 2012}} |

{{Use British English|date=October 2012}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date= |

{{Use dmy dates|date=June 2020}} |

||

{{Infobox person |

{{Infobox person |

||

| name |

| name = Leslie Howard |

||

| image |

| image = Leslie Howard GWTW.jpg |

||

| caption |

| caption = Howard as Ashley Wilkes in ''[[Gone with the Wind (film)|Gone with the Wind]]'', 1939 |

||

| birth_date |

| birth_date = {{birth date|1893|4|3|df=y}} |

||

| birth_place |

| birth_place = [[Forest Hill, London|Forest Hill]], [[County of London|London]], England |

||

| death_date |

| death_date = {{death date and age|1943|6|1|1893|4|3|df=y}} |

||

| death_place |

| death_place = At sea off the coast of [[Galicia, Spain]], near [[Cedeira]] |

||

| death_cause = [[BOAC Flight 777|Aircraft shot down]] |

|||

| birth_name = Leslie Howard Steiner |

|||

| |

| birth_name = Leslie Howard Steiner |

||

| occupation = {{hlist|Actor|director|producer|writer}} |

|||

| years_active = 1917–1943 |

|||

| years_active = 1913–1943 |

|||

| spouse = Ruth Evelyn Martin (1916–1943; his death; 2 children) |

|||

| known for = {{cslist |[[Sir Percy Blakeney]] in ''[[The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934 film)|The Scarlet Pimpernel]]'' (1934)|[[Professor Higgins]] in ''[[Pygmalion (1938 film)|Pygmalion]]'' (1938)|[[Ashley Wilkes]] in ''Gone with the Wind'' (1939) |semi=true}} |

|||

| children = [[Ronald Howard (British actor)|Ronald Howard]] (1918–1996)<br>Leslie Ruth Howard <br>(1924–2013) |

|||

| spouse = {{marriage|Ruth Evelyn Martin|1916}} |

|||

| children = 2, including [[Ronald Howard (British actor)|Ronald]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

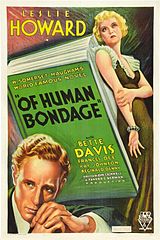

'''Leslie Howard''' (3 April 1893{{spaced ndash}}1 June 1943) was an English stage and film actor, director, and producer.<ref name="WVobit">Obituary ''[[Variety Obituaries|Variety]]'', 9 June 1943.</ref> Among his best-known roles was [[Ashley Wilkes]] in ''[[Gone with the Wind (film)|Gone with the Wind]]'' (1939) and roles in ''[[Berkeley Square (film)|Berkeley Square]]'' (1933), ''[[Of Human Bondage (1934 film)|Of Human Bondage]]'' (1934), ''[[The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934 film)|The Scarlet Pimpernel]]'' (1934), ''[[The Petrified Forest]]'' (1936), ''[[Pygmalion (1938 film)|Pygmalion]]'' (1938), ''[[Intermezzo (1939 film)|Intermezzo]]'' (1939), ''[["Pimpernel" Smith]]'' (1941) and ''[[The First of the Few]]'' (1942). |

|||

'''Leslie Howard Steiner''' (3 April 1893{{spaced ndash}}1 June 1943) was an English actor, director, producer and writer.<ref name="WVobit">Obituary, ''[[Variety Obituaries|Variety]]'', 9 June 1943.</ref> He wrote many stories and articles for ''[[The New York Times]]'', ''[[The New Yorker]]'', and ''[[Vanity Fair (magazine)|Vanity Fair]]'' and was one of the biggest box-office draws and movie idols of the 1930s. |

|||

Howard's [[World War II|Second World War]] activities included acting and filmmaking. He was active in anti-Nazi propaganda and reputedly involved with British or Allied Intelligence, which may have led to his death in 1943 when an airliner on which he was a passenger was shot down over the [[Bay of Biscay]], sparking conspiracy theories regarding his death. |

|||

Active in both Britain and Hollywood, Howard played [[Ashley Wilkes]] in ''[[Gone with the Wind (film)|Gone with the Wind]]'' (1939). He had roles in many other films, including ''[[Berkeley Square (1933 film)|Berkeley Square]]'' (1933), ''[[Of Human Bondage (1934 film)|Of Human Bondage]]'', ''[[The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934 film)|The Scarlet Pimpernel]]'' (both 1934), ''[[The Petrified Forest]]'' (1936), ''[[Pygmalion (1938 film)|Pygmalion]]'' (1938), ''[[Intermezzo (1939 film)|Intermezzo]]'' (1939), ''[["Pimpernel" Smith]]'' (1941), and ''[[The First of the Few]]'' (1942). He was nominated for the [[Academy Award for Best Actor]] for ''Berkeley Square'' and ''Pygmalion''. |

|||

Howard's [[Second World War]] activities included acting and filmmaking. He helped to make anti-German propaganda and shore up support for the Allies; two years after his death, the ''British Film Yearbook'' described Howard's work as "one of the most valuable facets of British propaganda". He was rumoured to have been involved with British or Allied Intelligence, sparking conspiracy theories regarding his death in 1943 when the [[Luftwaffe]] shot down [[BOAC Flight 777]] over the Atlantic (off the coast of [[Cedeira]], A Coruña), on which he was a passenger.<ref name=":0">{{cite news |url=https://www.lavozdegalicia.es/noticia/vigo/2009/06/04/patrick-gerassi-conexion-viguesa-leslie-howard/0003_7761757.htm |title=Patrick Gerassi, la conexión viguesa de Leslie Howard |date=2009-06-04 |work=La Voz de Galicia |access-date=2018-08-27 |language=es-ES}}</ref> |

|||

==Early life== |

==Early life== |

||

[[File:LESLIE HOWARD 1893-1943 Actor and Film Director lived here.jpg|thumb|upright|[[English Heritage]] [[blue plaque]] at 45 Farquhar Road, Upper Norwood, London]] |

|||

Howard was born '''Leslie Howard Steiner''' to a British mother, Lilian (''née'' Blumberg), and a [[Hungarian people|Hungarian]] father, Ferdinand Steiner, in [[Forest Hill, London]], UK. His father was Jewish and his mother was raised a Christian; her own grandfather was a Jewish immigrant from [[East Prussia]] who had married into the English upper classes.<ref>Eforgan 2010, pp. 1–10.</ref><ref name=elchieht>Nathan, John. [http://www.thejc.com/arts/book-reviews/42794/leslie-howard-the-lost-actor "Leslie Howard: The Lost Actor, The life and death of a non-spy."] ''The Jewish Chronicle,'' 20 December 2010. Retrieved: 20 December 2010.</ref> He was educated at [[Alleyn's School]], London. Like many others around the time of the [[World War I|First World War]], the family changed their name, using "Stainer" as less German-sounding. He worked as a bank clerk before [[wikt:enlist|enlisting]] at the outbreak of the First World War. He served in the [[British Army]] as a [[subaltern]] in the [[Northamptonshire Yeomanry]], but suffered [[Combat stress reaction|shell shock]], which led to his relinquishing his [[Officer (armed forces)#Commissioned officers|commission]] in May 1916. |

|||

Howard was born Leslie Howard Steiner to a [[British people|British]] mother, Lilian (''[[née]]'' Blumberg), and a [[History of the Jews in Hungary|Hungarian Jewish]] father, Ferdinand Steiner, in Forest Hill, London. His younger brother was actor [[Arthur Howard]]. Lilian had been raised as a [[Christians|Christian]], but she was of partial Jewish ancestry—her paternal grandfather Ludwig Blumberg, a Jewish merchant who had married into the English upper-middle classes.<ref>Eforgan 2010, pp. 1–10.</ref><ref name=elchieht>Nathan, John. [http://www.thejc.com/arts/book-reviews/42794/leslie-howard-the-lost-actor "Leslie Howard: The Lost Actor, The life and death of a non-spy."] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201021130910/https://www.thejc.com/arts/book-reviews/42794/leslie-howard-the-lost-actor |date=21 October 2020 }} ''The Jewish Chronicle'', 20 December 2010. Retrieved: 20 December 2010.</ref><ref>[http://forward.com/the-assimilator/133218/quintessential-british-actors-jewishness-not-gone/ Quintessential British Actor's Jewishness Not 'Gone With the Wind'] Ivry, Benjamin. The Jewish Daily Forward. Forward.com. Published 17 November 2010. Accessed 28 December 2015.</ref> |

|||

He received his formal education at [[Alleyn's School]], London. Like many others around the time of the [[First World War]], the family anglicised its name, in this case to "Stainer", although Howard's name remained Steiner in official documents, such as his military records. |

|||

Howard was a 21-year-old bank clerk in [[Dulwich]] when the First World War began; in September 1914 he voluntarily enlisted (under the name Leslie Howard Steiner) as a Private with the [[British Army]]'s [[Inns of Court Regiment|Inns of Court Officer Training Corps]] in London.<ref>Leslie Howard Steiner's WW1 British Army service file, document order code WO 374/65089, [[The National Archives (United Kingdom)|The National Archives, London]], published at [https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/39887-leslie-howard-filmstar-of-the-30s-40s/ 'The Great War Forum.org' website, 4 November 2005.]</ref> In February 1915 he received a commission as a [[Subaltern (military)|subaltern]] with the 3/1st [[Northamptonshire Yeomanry]], with which he trained in England until 19 May 1916, when he resigned his commission and was medically discharged from the British Army with [[neurasthenia]].<ref>''[[The London Gazette]]'' (Supplement) dated 18 May 1916, [https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/29587/supplement/4961/data.pdf p. 4961]</ref><ref>Leslie Howard's World War I British Army service file, document order code WO 374/65089, The National Archives, London, published at [https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/39887-leslie-howard-filmstar-of-the-30s-40s/ 'The Great War Forum.org' website, 4 November 2005.]</ref> |

|||

In March 1920, Howard gave public notice in ''[[The London Gazette]]'' that he had [[Name change#United Kingdom|changed his surname]], and would thereafter be known by the name of Howard instead of Steiner.<ref>"Notice of Change of Name by Deed Poll" in ''The London Gazette'', Issue 31809 dated 5 March 1920, [https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/31809/page/2821/data.pdf p. 2821]</ref> |

|||

==Theatre career== |

==Theatre career== |

||

[[File:Petrified-Forest-1935-1.jpg|thumb|upright=2.0|[[Humphrey Bogart]] (left) and Leslie Howard (standing center) in the Broadway stage production of ''The Petrified Forest'' (1935)]] |

|||

Howard began acting on the [[West End theatre|London stage]] in 1917 but had his greatest theatrical success in the United States on Broadway, in plays such as ''[[Aren't We All?]]'' (1923), ''[[Outward Bound (play)|Outward Bound]]'' (1924), and ''[[The Green Hat]]'' (1925). He became an undisputed Broadway star in ''[[Her Cardboard Lover]]'' (1927). After his success as [[time travel]]ler Peter Standish in ''[[Berkeley Square (play)|Berkeley Square]]'' (1929), he launched his [[Cinema of the United States|Hollywood]] career by repeating the Standish role in the 1933 film version of the play. |

|||

Howard began his professional acting career in regional tours of ''Peg O' My Heart'' and ''[[Charley's Aunt]]'' in 1916–17 and on the [[West End theatre|London stage]] in 1917, but had his greatest theatrical success in the United States in [[Broadway theatre]], in plays such as ''[[Aren't We All?]]'' (1923), ''[[Outward Bound (play)|Outward Bound]]'' (1924) and ''[[The Green Hat (play)|The Green Hat]]'' (1925). He became an undisputed Broadway star in ''Her Cardboard Lover'' (1927). After his success as [[time travel]]ler Peter Standish in ''[[Berkeley Square (play)|Berkeley Square]]'' (1929), Howard launched his [[Cinema of the United States|Hollywood]] career in the film version of ''[[Outward Bound (film)|Outward Bound]]'', but didn't like the experience and vowed never to return to [[Cinema of the United States|Hollywood]]. However, he did return, many times—later repeating the Standish role in the 1933 film version of ''[[Berkeley Square (1933 film)|Berkeley Square]]''. |

|||

The stage, however, continued to be an important part of his career. Howard frequently juggled acting, producing |

The stage, however, continued to be an important part of his career. Howard frequently juggled acting, producing and directing duties in the Broadway productions in which he starred. Howard was also a dramatist, and starred in the Broadway production of his own play ''Murray Hill'' (1927). He played Matt Denant in [[John Galsworthy]]'s 1927 Broadway production ''[[Escape (1927 play)|Escape]]'' in which he first made his mark as a dramatic actor. His stage triumphs continued with ''[[The Animal Kingdom (1932 film)|The Animal Kingdom]]'' (1932)<ref name="Howard IBDb"/> and ''[[The Petrified Forest (play)|The Petrified Forest]]'' (1934).<ref name="dn010835">{{cite news |last=Mantle |first=Burns |title='Petrified Forest' And 'Old Maid' Are New Plays |work=Daily News |date=January 8, 1935 |location=New York, New York |page=144 |via=[[Newspapers.com]]}}</ref> He later repeated both roles in the film versions. |

||

1927 [[Broadway theatre|Broadway]] production ''[[Escape (1927 play)|Escape]]''. (He also wrote, but did not act in ''Elizabeth Sleeps Out'' (1936).) He was always best known for his acting, enjoying triumphs in ''[[The Animal Kingdom]]'' (1932) and ''[[The_Petrified_Forest#Cast|The Petrified Forest]]'' (1935)<ref>[http://ibdb.com/production.php?id=7922 " 'The Petrified Forest'."] ''Internet Broadway Database.'' Retrieved: 21 May 2009.</ref> (repeating both roles on film in 1932 and 1936, respectively). But he had the bad timing to open on Broadway in [[William Shakespeare]]'s ''[[Hamlet]]'' (1936) just a few weeks after [[John Gielgud]] launched a rival production of the same play that was far more successful<ref>Croall, Jonathan. ''Gielgud: A Theatrical Life 1904–2000.'' London: Continuum, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8264-1333-8.</ref> with both critics and audiences. Howard’s production, his final stage role, lasted only 39 performances. |

|||

Howard loved to play Shakespeare, but according to producer [[John Houseman]] he could be lazy about learning lines. He first sprang to fame playing in ''[[Romeo and Juliet]]'' (1936) in the role of the leading man. During the same period he had the misfortune to open on Broadway in ''[[Hamlet]]'' (1936) just a few weeks after [[John Gielgud]] launched a rival production of the same play that was far more successful<ref>Croall, Jonathan. ''Gielgud: A Theatrical Life 1904–2000.'' London: Continuum, 2001. {{ISBN|978-0-8264-1333-8}}.</ref> with both critics and audiences. Howard's production, his final stage role, lasted for only 39 performances before closing. |

|||

Howard was inducted into the [[American Theatre Hall of Fame]] in 1981.<ref>[http://www.nytimes.com/1981/03/03/theater/26-elected-theater-hall-fame-26-broadway-voted-into-theater-hall-fame.html "26 Elected to the Theater Hall of Fame."] ''The New York Times'', 3 March 1981.</ref> |

|||

Howard was inducted into the [[American Theatre Hall of Fame]] in 1981.<ref>[https://www.nytimes.com/1981/03/03/theater/26-elected-theater-hall-fame-26-broadway-voted-into-theater-hall-fame.html "26 Elected to the Theater Hall of Fame."] ''The New York Times'', 3 March 1981.</ref> |

|||

==Film career== |

==Film career== |

||

[[File: |

[[File:Scarlet-Pimpernel-Howard-Oberon.jpg|thumb|upright|left|Howard as Sir Percy Blakeney ([[alter ego]] of [[the Scarlet Pimpernel]]) next to [[Merle Oberon]] as Lady Blakeney in ''[[The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934 film)|The Scarlet Pimpernel]]'' (1934)]] |

||

In 1920 Howard |

In 1920 Howard suggested to his friend [[Adrian Brunel]] that they form a film production company. After Howard's initial suggestion of calling it British Comedy Films Ltd., the two eventually settled on the name Minerva Films Ltd. The company's board of directors consisted of Howard, Brunel, [[C. Aubrey Smith]], [[Nigel Playfair]] and [[A. A. Milne]]. One of the company's investors was [[H. G. Wells]]. Although the films produced by Minerva—which were written by A. A. Milne—were well received by critics, the company was only offered £200 apiece for films that cost it £1,000 to produce, and Minerva Films was short-lived.<ref name="Brooke">{{cite AV media |last=Brooke |first=Michael |title=Howard, Leslie (1893–1943) |url=http://www.screenonline.org.uk/people/id/476673/ |publisher=BFI Screenonline}}</ref><ref>Eforgan 2010, pp. 39–46.</ref><ref>Howard, L.R. 1959, pp. 46–48, 66–67</ref> Early films include four written by A. A. Milne, including ''The Bump'', starring [[C. Aubrey Smith]]; ''Twice Two''; ''Five Pounds Reward''; and ''Bookworms'', the latter two starring Howard. Some of these films survive in the archives of the [[British Film Institute]]. |

||

In British and Hollywood productions, Howard often played [[stiff upper lip]]ped Englishmen. He appeared in the film version of ''[[Outward Bound (film)|Outward Bound]]'' (1930), though in a different role from the one he portrayed on Broadway. He had [[Billing (filmmaking)|second billing]] under [[Norma Shearer]] in ''[[A Free Soul]]'' (1931), which also featured [[Lionel Barrymore]] and future ''[[Gone with the Wind (film)|Gone With the Wind]]'' rival [[Clark Gable]] eight years prior to their [[American Civil War|Civil War]] masterpiece. He starred in the film version of ''Berkeley Square'' (1933), for which he was nominated for an [[Academy Award]] for [[Academy Award for Best Actor|Best Actor]]. He played the title role in ''[[The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934 film)|The Scarlet Pimpernel]]'' (1934), which is often considered the definitive portrayal.<ref>{{cite book |last=Richards |first=Jeffrey |title=Swordsmen of the Screen: From Douglas Fairbanks to Michael York |publisher=Routledge |date=2014 |page=163}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Pygmalion-1938.jpg|thumb|[[Scott Sunderland (actor)|Scott Sunderland]], Leslie Howard and [[Wendy Hiller]] in ''[[Pygmalion (1938 film)|Pygmalion]]'' (1938), which Howard co-directed]] |

|||

[[File:Leslie Howard - Myrna Loy - 32.JPG|thumb|left|with [[Myrna Loy]] in ''The Animal Kingdom'' (1932)]] |

|||

Howard co-starred with [[Bette Davis]] in ''[[The Petrified Forest]]'' (1936) |

When Howard co-starred with [[Bette Davis]] in ''[[The Petrified Forest]]'' (1936) – having earlier co-starred with her in the film adaptation of [[W. Somerset Maugham]]'s book ''[[Of Human Bondage (1934 film)|Of Human Bondage]]'' (1934) – he reportedly insisted that [[Humphrey Bogart]] play [[gangster]] Duke Mantee, repeating his role from the stage production. This re-launched Bogart's screen career, and the two men became lifelong friends; Bogart and [[Lauren Bacall]] later named their daughter "Leslie Howard Bogart" after him.<ref>Sklar 1992, pp. 60–62.</ref> In the same year Howard starred with [[Norma Shearer]] in a film version of Shakespeare's ''[[Romeo and Juliet (1936 film)|Romeo and Juliet]]'' (1936). |

||

Bette Davis was again Howard's co-star in the romantic comedy ''[[It's Love I'm After]]'' (1937) (also co-starring [[Olivia de Havilland]]). He played Professor Henry Higgins in the film version of [[George Bernard Shaw]]'s play ''[[Pygmalion (1938 film)|Pygmalion]]'' (1938), with [[Wendy Hiller]] as Eliza, which earned Howard another [[Academy Award for Best Actor|Academy Award nomination for Best Actor]]. In 1939, as war approached, he played opposite [[Ingrid Bergman]] in ''[[Intermezzo (1939 film)|Intermezzo]]''; that August, Howard was determined to return to the country of his birth. He was eager to help the war effort, but lost any support for a new film, instead being obliged to relinquish £20,000 of holdings in the US before he could leave the country. |

|||

Howard had earlier co-starred with Davis in the film adaptation of [[W. Somerset Maugham]]'s book ''[[Of Human Bondage (1934 film)|Of Human Bondage]]'' (1934) and later in the romantic comedy ''[[It's Love I'm After]]'' (1937) (also co-starring [[Olivia de Havilland]]). Howard starred with [[Ingrid Bergman]] in ''Intermezzo'' (1939) and [[Norma Shearer]] in a film version of Shakespeare's ''[[Romeo and Juliet (1936 film)|Romeo and Juliet]]'' (1936). |

|||

Howard is perhaps best remembered for his role as Ashley Wilkes in ''[[Gone with the Wind (film)|Gone |

Howard is perhaps best remembered for his role as Ashley Wilkes in ''[[Gone with the Wind (film)|Gone with the Wind]]'' (1939), his last American film, but he was uncomfortable with Hollywood, and returned to [[UK|Britain]] to help with the [[Second World War]] effort. He starred in a number of Second World War films, including ''[[49th Parallel (film)|49th Parallel]]'' (1941), ''[["Pimpernel" Smith]]'' (1941) and ''[[The First of the Few]]'' (1942, known in the U.S. as ''Spitfire''), the latter two of which he also directed and co-produced.<ref>{{cite web |last=Costanzi |first=Karen |url=http://www.things-and-other-stuff.com/movies/profiles/leslie-howard.html |title=Leslie Howard: Actor & Patriot |publisher=things-and-other-stuff.com |access-date=2010-07-23}}</ref> His friend and ''The First of the Few'' co-star [[David Niven]] said Howard was "...not what he seemed. He had the kind of distraught air that would make people want to mother him. Actually, he was about as naïve as General Motors. Busy little brain, always going."<ref>Finnie, Moira. [http://moirasthread.blogspot.com/2008/04/few-kind-words-for-leslie-howard.html "A Few Kind Words for Leslie Howard."] ''Skeins of Thought'', 2008. Retrieved: 4 August 2010.</ref> |

||

In 1944, after his death, British exhibitors voted him the second |

In 1944, after his death, British exhibitors voted him the second-most popular local star at the box office.<ref>[http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article63154283 "Bitter Street fighting."] ''[[Townsville Daily Bulletin]]'', 6 January 1944, p. 2 via ''National Library of Australia'', Retrieved: 11 July 2012.</ref> His daughter said he was a "remarkable man".<ref>{{cite web |title=The Man Who Gave a Damn |publisher=Repo Films for Talking Pictures TV |date=2016}}</ref> |

||

<gallery mode="packed" heights="160px"> |

|||

==Personal life== |

|||

File:A Free Soul (1931) film poster.jpg|''[[A Free Soul]]'' (1931) [[film poster]] |

|||

Howard married Ruth Evelyn Martin in 1916<ref>"Leslie H. Steiner = Ruth E. Martin." ''GRO Register of Marriages: Colchester, March 1916, 4a 1430.</ref> and they had two children. His son [[Ronald Howard (British actor)|Ronald Howard]] (1918–1996)<ref>"Ronald H. Stainer, mmn = Martin." ''GRO Register of Births: Lambeth, June 1918, 1d 598.</ref> became an actor and is noted for portraying the title character in the 1954 television series ''[[Sherlock Holmes (1954 TV Series)|Sherlock Holmes]]''. |

|||

File:Leslie Howard-Ann Harding in The Animal Kingdom.jpg|Howard and [[Ann Harding]] in ''[[The Animal Kingdom (1932 film)|The Animal Kingdom]]'' (1932) |

|||

File:Leslie Howard - Myrna Loy - 32.JPG|Howard and [[Myrna Loy]] in ''[[The Animal Kingdom (1932 film)|The Animal Kingdom]]'' (1932) |

|||

File:Of Human Bondage Poster.jpg|''[[Of Human Bondage (1934 film)|Of Human Bondage]]'' (1934) film poster |

|||

File:Leslie Howard and Norma Shearer as Romeo and Juliet.jpg|Howard and [[Norma Shearer]] in ''[[Romeo and Juliet (1936 film)|Romeo and Juliet]]'' (1936) |

|||

File:Romeo and Juliet lobby card 2.jpg|''[[Romeo and Juliet (1936 film)|Romeo and Juliet]]'' (1936) lobby card with [[John Barrymore]] and [[Basil Rathbone]] |

|||

File:Spitfire-1943-Howard-John.jpg|Howard and [[Rosamund John]] in ''[[The First of the Few]]'' (1942) |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

==Personal life== |

|||

[[Arthur Howard|Arthur]], Howard's younger brother, was also an actor, primarily in British comedies. A sister, [[Irene Howard|Irene]], was a costume designer. Another sister, Doris Stainer, founded a small school, Hurst Lodge, in [[Sunningdale]], Berkshire, UK, and remained its [[head teacher|headmistress]] for some years. |

|||

Howard married Ruth Evelyn Martin (1895–1980) in March, 1916.<ref>"Leslie H. Steiner = Ruth E. Martin." ''GRO Register of Marriages: Colchester'', March 1916. 4a 1430.</ref> Their children were [[Ronald Howard (British actor)|Ronald "Winkie"]] (1918–1996) and Leslie Ruth "Doodie" (1924–2013) who appeared with her father and David Niven in the film ''[[The First of the Few]]'' (1942), playing the role of nurse to David Niven's character, and was a major contributor in the filmed biography of her father, ''Leslie Howard: The Man Who Gave a Damn''. His son, [[Ronald Howard (British actor)|Ronald Howard]], became an actor and played the title role in the television series ''[[Sherlock Holmes (1954 TV Series)|Sherlock Holmes]]'' (1954).<ref>"Ronald H. Stainer, mmn = Martin." ''GRO Register of Births: Lambeth'', June 1918, 1d 598.</ref> His younger brother [[Arthur Howard|Arthur]] was also an actor, primarily in British comedies. His sister [[Irene Howard|Irene]] was a costume designer and a casting director for [[Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer]].<ref>Ronald Howard, ''In Search of My Father: A Portrait of Leslie Howard'', St. Martin's Press, New York 1981 {{ISBN|0-312-41161-8}}</ref> His sister Doris Stainer founded the [[Hurst Lodge School]] in [[Sunningdale]], [[Berkshire]], in 1945 and remained its headmistress until the 1970s.<ref>''[[The Times]]'', issue 50336 dated Saturday, 29 December 1945, p. 1</ref> |

|||

Howard was widely known as a "ladies' man", and he once said that he "didn't chase women but ... couldn't always be bothered to run away".<ref name="ron" /><ref name="Gazeley">Gazeley, Helen. [https://web.archive.org/web/20101003134606/http://www.telegraph.co.uk/property/3357830/Memories-of-Hollywood-in-the-hills-of-Surrey.html "Memories of Hollywood, in the hills of Surrey."] ''The Daily Telegraph'' (London), 29 April 2007. Retrieved: 4 August 2010.</ref> He reportedly had affairs with [[Tallulah Bankhead]] when they appeared on stage in the UK in ''Her Cardboard Lover'' (1927), with [[Merle Oberon]] while filming ''The Scarlet Pimpernel'' (1934) and with [[Conchita Montenegro]], with whom he had appeared in the film ''Never the Twain Shall Meet'' (1931).<ref>[https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0022197/ IMDb Never the Twain Shall Meet (1931)] ''imdb.com'', accessed 1 June 2018</ref> There were also rumours of affairs with Norma Shearer and [[Myrna Loy]] during filming of ''The Animal Kingdom''.<ref>[https://www.theguardian.com/film/2010/sep/12/leslie-howard-found-footage "Leslie Howard found footage."]''The Guardian'', 12 September 2010. Retrieved: 3 May 2012.</ref> Howard reportedly fathered a daughter - [[Carol Grace]], born 1924 - by Rosheen Marcus; Carol married writer [[William Saroyan]] and then actor [[Walter Matthau]].<ref>[http://matthau.com/carol/biography.html "Matthau family official website"], matthau.com; accessed April 17, 2021.</ref> |

|||

Howard fell in love with Violette Cunnington in 1938 while working on ''Pygmalion''. She was secretary to [[Gabriel Pascal]] who was producing the film; she became Howard's secretary and lover and they travelled to the United States and lived together while he was filming ''Gone with the Wind'' and ''Intermezzo'' (both 1939). His wife and daughter joined him in Hollywood before production ended on the two films, making his arrangement with Cunnington somewhat uncomfortable for everyone.<ref>Howard, L. R. 1959.</ref>{{page needed|date= October 2022}}<ref>Howard, L., ed. with R. Howard 1982.</ref>{{page needed|date= October 2022}}<ref>Howard, R. 1984.</ref>{{page needed|date= October 2022}} He left the United States for the last time with his wife and daughter in August, 1939 and Cunnington soon followed. She appeared in ''"Pimpernel" Smith'' (1941) and ''The First of the Few'' (1942) in minor roles under the stage name of Suzanne Clair. She died of pneumonia in her early thirties in 1942, just six months before Howard's death. Howard left her his [[Beverly Hills]] house in his will.<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20081215012903/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,933383,00.html "Milestones, 8 May 1944."] ''Time'' magazine, 8 May 1944.</ref><ref>Gates, Anita. [https://www.nytimes.com/2004/11/07/movies/moviesspecial/07gate2.html "The Good Girl Gets the Last Word (interview with Olivia de Havilland)."] ''The New York Times'', 7 November 2004. Retrieved 22 July 2010.</ref> |

|||

Howard's [[will (law)|will]] revealed an [[estate (law)|estate]] of $251,000, or [[pounds sterling|£]]62,761 (in 1943 [[pounds sterling]] [[based on 2005 values this is approximately £1,802,495.92]]<ref>Parker, John. "1939." ''Who's Who in the Theatre'', 10th ed. London: Pitmans, 1947.</ref> |

|||

The Howard family's home in Britain was Stowe Maries, a 16th-century, six-bedroom farmhouse on the edge of [[Westcott, Surrey]].<ref name="Gazeley"/> His will revealed an estate of £62,761, the equivalent of £{{Formatprice|{{Inflation|UK|62761|1943|{{inflation-year|UK}}|r=-6}}}} as of {{inflation-year|UK}}.{{Inflation-fn|UK}}<ref>Parker, John. "1939." ''Who's Who in the Theatre'', 10th ed. London: Pitmans, 1947.</ref> An [[English Heritage]] [[blue plaque]] was placed at 45 Farquhar Road, Upper Norwood, London in 2013.<ref name='EngHet'>{{cite web |url=http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/discover/blue-plaques/search/howard-leslie-1893-1943 |title=Howard, Leslie (1893–1943) |publisher=[[English Heritage]] |access-date=4 May 2014}}</ref> |

|||

There are also rumors of affairs with [[Norma Shearer]] and [[Myrna Loy]] (during filming of ''The Animal Kingdom'').<ref>[http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2010/sep/12/leslie-howard-found-footage "Leslie Howard found footage."]''The Guardian,'' 12 September 2010. Retrieved: 3 May 2012.</ref> |

|||

==Death== |

==Death== |

||

{{ |

{{Further|BOAC Flight 777}} |

||

[[File: |

[[File:BOAC777passengerlist.jpg|thumb|[[BOAC Flight 777]] passenger list]] |

||

[[File:Bay of Biscay map.png|thumb|BOAC Flight 777 was shot down over the Bay of Biscay.]] |

|||

Howard died in 1943 when flying to [[Bristol]], UK, from [[Lisbon]], Portugal, on [[BOAC Flight 777]]. The aircraft, "G-AGBB" a [[Douglas DC-3]], was shot down by ''[[Luftwaffe]]'' [[Junkers Ju 88|Junkers Ju 88C6]] maritime fighter aircraft over the [[Bay of Biscay]].<ref name=goss>Goss 2001, pp. 50–56.</ref> Howard was among the 17 fatalities, including four ex-KLM flight crew.<ref name="Crash"/><ref>[http://www.cwgc.org/search/casualty_details.aspx?casualty=3168815 "Casualty details: Leslie Howard."] ''Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC)''. Retrieved: 4 August 2010.</ref> |

|||

In May 1943, Howard travelled to [[Portugal]] to promote the British cause. He stayed in Monte [[Estoril]], at the Hotel Atlântico, between 1 May and 4 May, then again between 8 May and 10 May and again between 25 May and 31 May 1943.<ref>[[Exiles Memorial Center]].</ref> The following day, 1 June 1943, he was aboard [[KLM|KLM Royal Dutch Airlines]]/[[BOAC Flight 777]], "G-AGBB" a [[Douglas DC-3]] flying from [[Lisbon]] to [[Bristol]], when it was shot down by ''[[Luftwaffe]]'' [[Junkers Ju 88]] C-6 maritime fighter aircraft over the Atlantic (off [[Cedeira]], [[A Coruña]]).<ref name=":0" /><ref name=goss>Goss 2001, pp. 50–56.</ref> He was among the 17 fatalities, including four KLM flight crew.<ref name="Crash"/><ref>[http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/3168815 "Casualty details: Leslie Howard."] ''Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC)''. Retrieved: 4 August 2010.</ref> |

|||

The BOAC DC-3 ''Ibis'' had been operating on a scheduled Lisbon–Whitchurch route throughout 1942–1943 that did not pass over what would commonly be referred to as a war zone. By 1942, however, the Germans considered the region an "extremely sensitive war zone."<ref name="Rosevink and Hintze, p. 14">Rosevink and Hintze 1991, p. 14.</ref> On two occasions, 15 November 1942, and 19 April 1943, the camouflaged airliner had been attacked by [[Messerschmitt Bf 110]] fighters (a single aircraft and six Bf 110s, respectively) while en route; each time, the pilots escaped via evasive tactics.<ref name=dutchairlines>[http://web.archive.org/web/20041106060816/home.hetnet.nl/~dutchairliners/klm/DC3.htm "Douglas DC-3-194 PH-ALI 'Ibis'."] ''web.archive.org,'' 2004. Retrieved: 23 July 2010.</ref> On 1 June 1943, "G-AGBB" again came under attack by a ''schwarm'' of eight V/KG40 Ju 88C6 maritime fighters. The DC-3's last radio message indicated it was being fired upon at longitude 09.37 West, latitude 46.54 North.<ref name="Crash">[http://aviation-safety.net/database/record.php?id=19430601-0 "ASN Aircraft accident Douglas DC-3-194 G-AGBB Bay of Biscay."] ''Aviation Safety Network.'' Retrieved: 23 July 2010.</ref> |

|||

The BOAC DC-3 ''Ibis'' had been operating on a scheduled Lisbon–Whitchurch route throughout 1942–43 that did not pass over what would commonly be referred to as a [[War|war zone]]. By 1942, however, the Germans considered the region an "extremely sensitive war zone".<ref name="Rosevink and Hintze, p. 14">Rosevink and Hintze 1991, p. 14.</ref> On two occasions, 15 November 1942 and 19 April 1943, the camouflaged airliner had been attacked by [[Messerschmitt Bf 110]] fighters (a single aircraft and six Bf 110s, respectively) while ''en route''; each time, the pilots escaped by evasive tactics.<ref name=dutchairlines>{{cite web |url=http://home.hetnet.nl/~dutchairliners/klm/DC3.htm |title=Douglas DC-3-194 PH-ALI 'Ibis' |access-date=2017-05-14 |url-status=bot: unknown |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20041106060816/http://home.hetnet.nl/~dutchairliners/klm/DC3.htm |archive-date=6 November 2004 }}. Retrieved: 23 July 2010.</ref> |

|||

According to German documents, the DC-3 was shot down at longitude 10.15 West, latitude 46.07 North, some {{convert|500|mi|km}} from [[Bordeaux]], France, and {{convert|200|mi|km}} northwest of [[A Coruña, Spain]]. ''Luftwaffe'' records indicate that the Ju 88 maritime fighters were operating beyond their normal patrol area to intercept and shoot down the aircraft.<ref name="ron" />''Bloody Biscay: The Story of the Luftwaffe's Only Long Range Maritime Fighter Unit, V Gruppe/[[Kampfgeschwader 40]], and Its Adversaries 1942–1944'' (Chris Goss, 2001) quotes First ''[[Oberleutnant]]'' Herbert Hintze, ''Staffel Führer'' of 14 ''Staffeln'' and based in Bordeaux, that his ''Staffel'' shot down the DC-3 because it was recognised as an enemy aircraft, unaware that it was an unarmed civilian airliner. Hintze further states that his pilots were angry that the ''Luftwaffe'' leaders had not informed them of a scheduled flight between Lisbon and the UK, and that had they known, they could easily have escorted the DC-3 to Bordeaux and captured it and all aboard. The German pilots photographed the wreckage floating in the Bay of Biscay and after the war, copies of these captured photographs were sent to Howard's family.<ref name="goss"/> |

|||

On 1 June 1943, "G-AGBB" again came under attack by a swarm of eight V/KG40 Ju 88 C-6 maritime fighters. The DC-3's last radio message indicated it was being fired upon at longitude 09.37 West, latitude 46.54 North.<ref name="Crash">[http://aviation-safety.net/database/record.php?id=19430601-0 "ASN Aircraft accident Douglas DC-3-194 G-AGBB Bay of Biscay."] ''Aviation Safety Network.'' Retrieved: 23 July 2010.</ref> |

|||

The following day, a search of the Bay of Biscay was undertaken by "N/461", a [[Short Sunderland]] flying boat from No. 461 RAAF Squadron. Near the same coordinates where the DC-3 was shot down, the Sunderland was attacked by eight Ju 88s and after a furious battle, managed to shoot down three of the attackers, scoring an additional three "possibles," before crash-landing at [[Penzance]]. In the aftermath of these two actions, all BOAC flights from Lisbon were subsequently re-routed and operated only under the cover of darkness.<ref name="N461"/> |

|||

According to German documents, the DC-3 was shot down at {{coord|46|07|N|10|15|W}}, some {{convert|500|mi|km}} from [[Bordeaux]], France, and {{convert|200|mi|km}} northwest of [[La Coruña, Spain]]. ''Luftwaffe'' records indicate that the Ju 88 maritime fighters were operating beyond their normal patrol area to intercept and shoot down the aircraft.<ref name="ron" /> ''[[Oberleutnant]]'' Herbert Hintze, ''[[Staffelkapitän]]'' of 14 ''Staffel'', V./[[Kampfgeschwader 40]], and based in Bordeaux, stated that his ''Staffel'' shot down the DC-3 because it was recognized as an enemy aircraft. |

|||

The news of Howard's death was published in the same issue of ''[[The Times]]'' that reported the "death" of Major William Martin, the red herring used for the ruse involved in [[Operation Mincemeat]].<ref>''The Times'', Thursday, 3 June 1943, p. 4.</ref> |

|||

Hintze further stated that his pilots were angry that the ''Luftwaffe'' leaders had not informed them of a scheduled flight between Lisbon and the UK, and that had they known, they could easily have escorted the DC-3 to Bordeaux and captured it and all aboard. The German pilots photographed the wreckage floating in the Bay of Biscay, and after the war, copies of these captured photographs were sent to Howard's family.<ref name="goss"/> |

|||

==Theories regarding the air attack== |

|||

A long-standing hypothesis states that the Germans believed that [[Prime Minister of the United Kingdom|UK Prime Minister]] [[Winston Churchill]], was on board the flight.<ref>Wilkes, Donald E., Jr. [http://www.law.uga.edu/dwilkes_more/other_1ashley.html "The Assassination of Ashley Wilkes."] ''The Athens Observer'', 8 June 1995 p. 7A, via ''law.uga.edu.'' Retrieved: 23 July 2010.</ref> Churchill, in his autobiography, expressed sorrow that a mistake about his activities might have cost Howard his life.<ref>Churchill 1950, p. 830.</ref> The ''BBC'' television series "Churchill‘s Bodyguard" (original broadcast 2006) suggested that [[Abwehr|(''Abwehr'') German intelligence]] agents had learned of Churchill’s proposed departure and route. Churchill’s bodyguard, Detective Inspector [[Walter H. Thompson]] later wrote that Churchill, at times, seemed clairvoyant about threats to his safety, and, acting on a premonition, changed his departure to the following day. |

|||

The following day, a search of the waters on the route was undertaken by "N/461", a [[Short Sunderland]] flying boat from [[No. 461 Squadron RAAF]]. Near the same coordinates where the DC-3 was shot down, the Sunderland was attacked by eight Ju 88s and, after a furious battle, it managed to shoot down three of the attackers, with an additional three "possibles", before crash-landing at [[Praa Sands]] near [[Penzance]]. In the aftermath of these two actions, all BOAC flights from Lisbon were re-routed and operated only under the cover of darkness.<ref name="N461"/> |

|||

Speculation by historians also centred on whether British code breakers had decrypted top secret [[Enigma machine|Enigma messages]] outlining the assassination plan, and Churchill may have wanted to protect the code breaking operation so the ''[[Oberkommando der Wehrmacht]]'' would not suspect that their Enigma machines were compromised. German spies (who commonly watched the airfields of neutral countries), may then have mistaken Howard and his manager, as they boarded their aircraft, for Churchill and his bodyguard, as Howard's manager Alfred Chenhalls physically resembled Churchill, while Howard was tall and thin, like Thompson. Although the overwhelming majority of published documentation of the case repudiates this theory, it remains a possibility. The timing of Howard's takeoff and the flight path were similar to Churchill's flight, making it easy for the Germans to have mistaken the two flights.<ref>[http://www.7digital.com/stores/historytv/artists/churchills-bodyguard/complete-series-%281%29/ " 'Churchill‘s Bodyguard' – Complete Series."] ''Nugus Martin Productions'' via ''7digital.com'', 2006. Retrieved: 23 July 2010.</ref> |

|||

The news of Howard's death was published in the same issue of ''[[The Times]]'' that reported the "death" of [[Major William Martin]], the "Man who never was" created for the ruse involved in [[Operation Mincemeat]].<ref>''The Times'', Thursday, 3 June 1943, p. 4.</ref> |

|||

Two books focusing on the final flight, ''Flight 777'' (Ian Colvin, 1957), and ''In Search of My Father: A Portrait of Leslie Howard'' ([[Ronald Howard (British actor)|Ronald Howard]], 1984), concluded that the Germans deliberately shot down Howard's DC-3 to assassinate him, and demoralize Britain.<ref name="ron">Howard 1984</ref><ref>Colvin 2007, p. 187.</ref> Howard had been travelling through Spain and Portugal lecturing on film, but also meeting with local propagandists and shoring up support for the [[Allies of World War II|Allies]]. The British Film Yearbook for 1945 described Leslie Howard's work as "one of the most valuable facets of British propaganda".<ref>Noble 1945, p. 74.</ref> |

|||

===Theories regarding the air attack=== |

|||

The Germans could have suspected even more surreptitious activities, since Portugal, like Switzerland, was a crossroads for internationals, and spies, from both sides. British historian James Oglethorpe, investigated Howard's connection to the secret services.<ref>[http://lesliehowardsociety.multiply.com "Leslie Howard."] ''lesliehowardsociety.multiply.com''. Retrieved: 22 July 2010.</ref> Ronald Howard's book explores the written German orders to the Ju 88 ''Staffel'', in great detail, as well as British communiqués that verify intelligence reports indicating a deliberate attack on Howard. These accounts indicate that the Germans were aware of Churchill's real whereabouts at the time and were not so naive as to believe he would be travelling alone on board an unescorted, unarmed civilian aircraft, which Churchill also acknowledged as improbable. Ronald Howard was convinced the order to shoot down Howard's airliner came directly from [[Joseph Goebbels]], [[Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda|Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda]] in [[Nazi Germany]], who had been ridiculed in one of Leslie Howard's films, and believed Howard to be the most dangerous British propagandist.<ref name="ron" /> |

|||

[[File:Monumento á memoria do actor Leslie Howard.jpg|thumb|Monument to the memory of Leslie Howard and his companions in [[Cedeira]], [[Galicia (Spain)|Galicia, Spain]]]] |

|||

A long-standing but ultimately unsupported hypothesis suggested that the Germans believed that the [[Prime Minister of the United Kingdom|British Prime Minister]], [[Winston Churchill]], was on board the flight.<ref>Wilkes, Donald E., Jr. [http://www.law.uga.edu/dwilkes_more/other_1ashley.html "The Assassination of Ashley Wilkes."] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120111080221/http://www.law.uga.edu/dwilkes_more/other_1ashley.html |date=11 January 2012}} ''The Athens Observer'', 8 June 1995 p. 7A, via ''law.uga.edu.'' Retrieved: 23 July 2010.</ref> Churchill's history of World War II suggested that the Germans targeted the commercial flight because the British Prime Minister's "presence in North Africa [for the 1943 [[Casablanca conference]]] had been fully reported", and German agents at the Lisbon airfield mistook a "thickset man smoking a cigar" boarding the plane for Churchill returning to England. This thickset man was Howard's agent, Alfred Chenhalls.<ref>[[Neill Lochery|Lochery, Neill]]. ''Lisbon: War in the Shadows of the City of Light, 1939-1945''. New York: Public Affairs, 2011, pp. 156, 159.</ref> The death of the fourteen civilians including Leslie Howard "was a painful shock to me", Churchill wrote; "the brutality of the Germans was only matched by the stupidity of their agents".<ref>Winston Churchill, ''The Second World War: The Hinge of Fate'' (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1950) Vol. 4 p. 830.</ref> |

|||

Most of the 13 passengers were either British executives with corporate ties to Portugal, or lower-ranking British government civil servants. There were also two or three children of British military personnel.<ref name="ron" /> The bumped passengers were the teenage sons of [[Cornelia Stuyvesant Vanderbilt]]: [[George Henry Vanderbilt Cecil|George]] and [[William Amherst Vanderbilt Cecil|William Cecil]], who had been recalled to London from their Swiss boarding school. Being bumped by Howard saved their lives. William Cecil is best associated with his ownership and preservation of his grandfather George Washington Vanderbilt's Biltmore estate in North Carolina. William Cecil described a story in which he met a woman, several months after his return to London, who said she had secret war information, and used his mother's phone to put in a call to the British Air Ministry. She told them that she had a message from Leslie Howard.<ref>Covington 2006, pp. 102–103.</ref> |

|||

Two books focusing on the final flight, ''Flight 777'' (Ian Colvin, 1957) and ''In Search of My Father: A Portrait of Leslie Howard'' ([[Ronald Howard (British actor)|Ronald Howard]], 1984), asserted that the target was Howard instead: that Germans deliberately shot down Howard's DC-3 to demoralise Britain.<ref name="ron">Howard 1984</ref><ref>Colvin 2007, p. 187.</ref> Howard had been travelling through Spain and Portugal lecturing on film, but also meeting with local propagandists and shoring up support for the [[Allies of World War II|Allies]]. The ''British Film Yearbook'' for 1945 described Leslie Howard's work as "one of the most valuable facets of British propaganda".<ref>Noble 1945, p. 74.</ref> |

|||

A 2008 book by Spanish writer José Rey Ximena<ref>Rey Ximena 2008</ref> claims that Howard was on a top-secret mission for Churchill to dissuade [[Francisco Franco]], Spain's authoritarian dictator and [[head of state]], from joining the [[Axis powers]].<ref name="UPI">[http://www.upi.com/Entertainment_News/2008/10/06/Book_Howard_kept_Spain_from_joining_WWII/UPI-48541223340587/ "Book: Howard kept Spain from joining WWII."] ''[[United Press International]]'', 6 October 2008. Retrieved: 25 May 2009.</ref> Via an old girlfriend, [[Conchita Montenegro]],<ref name="UPI"/> Howard had contacts with Ricardo Giménez Arnau, a young diplomat in the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Further circumstantial background evidence is revealed in Jimmy Burns's 2009 biography of his father, spymaster Tom Burns.<ref>Ridley, Jane. [http://www.spectator.co.uk/books/5457543/from-madrid-with-love.thtml "From Madrid with Love."] ''The Spectator'' via ''spectator.co.uk,'' 24 October 2009. Retrieved: 4 August 2010.</ref> According to author [[William Stevenson (Canadian writer)|William Stevenson]] in ''A Man called Intrepid'', his biography of [[William Stephenson|Sir William Samuel Stephenson]] (no relation), the senior representative of British Intelligence for the western hemisphere during the Second World War,<ref>Stevenson 2000, p. 179.</ref> Stephenson postulated that the Germans knew about Howard's mission and ordered the aircraft shot down. Stephenson further claimed that Churchill knew in advance of the German intention to shoot down the aircraft, but allowed it to proceed to protect the fact that the British had broken the German Enigma code.<ref>[http://www.trueintrepid.com/CndPress.htm "Intrepid Book Brings Spy's Life From Shadows."] ''trueintrepid.com.'' Retrieved: 23 July 2010.</ref> Former CIA agent Joseph B. Smith recalled that, in 1957, he was briefed by the National Security Agency on the need for secrecy and that Leslie Howard's death had been brought up. The NSA claimed that Howard knew his aircraft was to be attacked by German fighters and sacrificed himself to protect the British code-breakers.<ref>Smith 1976, p. 389.</ref> |

|||

The Germans could have suspected even more surreptitious activities, since Portugal, like [[Switzerland]], was a crossroads for internationals and spies from both sides. British historian James Oglethorpe investigated Howard's connection to the secret services.<ref>[http://lesliehowardsociety.multiply.com "Leslie Howard."] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101024013919/http://lesliehowardsociety.multiply.com/ |date=24 October 2010 }} ''lesliehowardsociety.multiply.com''. Retrieved: 22 July 2010.</ref> Ronald Howard's book explores the written German orders to the Ju 88 squadron in great detail, as well as British communiqués that purportedly verify intelligence reports indicating a deliberate attack on Howard. These accounts indicate that the Germans were aware of Churchill's real whereabouts at the time and were not so naïve as to believe he would be travelling alone on board an unescorted, unarmed civilian aircraft, which Churchill also acknowledged as improbable. Ronald Howard was convinced the order to shoot down Howard's airliner came directly from [[Joseph Goebbels]], [[Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda|Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda]] in [[Nazi Germany]], who had been ridiculed in one of Leslie Howard's films, and believed Howard to be the most dangerous British propagandist.<ref name="ron" /> |

|||

The 2010 biography by Estel Eforgan, ''Leslie Howard: The Lost Actor'', examines currently available evidence and concludes that Howard was not a specific target,<ref>Eforgan 2010, pp. 217–245.</ref> corroborating the claims by German sources that the shootdown was "an error in judgement".<ref name="N461">Matthews, Rowan. [http://www.n461.com/howard.html "N461: Howard & Churchill."] ''n461.com, '' 2003. Retrieved: 23 July 2010.</ref> There is a monument in San Andrés de Teixido, Spain, dedicated to the victims of the crash. Howard's aircraft was shot down over the sea north of this village.<ref>Castro, Jesus (translated by Rachael Harrison). [http://www.eyeonspain.com/blogs/jesuscastro/2961/the-actor-the-jew-and-churchill%E2%80%99s-double.aspx "The actor, the Jew and Churchill’s double."] ''eyeonspain.com.'' Retrieved: 18 August 2011.</ref> |

|||

Most of the 13 passengers were either British businessmen with commercial connections to Portugal, or lower-ranking British government civil servants. There were also two or three children of British military personnel.<ref name="ron" /> Two passengers were bumped off the flight, [[George Henry Vanderbilt Cecil|George]] and [[William Amherst Vanderbilt Cecil|William Cecil]], the teenage sons of [[Cornelia Stuyvesant Vanderbilt]], who had been recalled to London from their Swiss boarding school, thus saving their lives.<ref>Covington 2006, pp. 102–103.</ref> |

|||

A 2008 book by Spanish writer José Rey Ximena<ref>Rey Ximena 2008</ref> argues that Howard was on a top-secret mission for Churchill to dissuade Spanish dictator [[Francisco Franco]] from joining the [[Axis powers]].<ref name="UPI">[http://www.upi.com/Entertainment_News/2008/10/06/Book_Howard_kept_Spain_from_joining_WWII/UPI-48541223340587/ "Book: Howard kept Spain from joining WWII."] ''[[United Press International]]'', 6 October 2008. Retrieved: 25 May 2009.</ref> Via an old girlfriend, [[Conchita Montenegro]],<ref name="UPI"/> Howard had contacts with Ricardo Giménez Arnau, a young diplomat in the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. |

|||

Further merely circumstantial background evidence is revealed in Jimmy Burns's 2009 [[biography]] of his father, spymaster Tom Burns.<ref>Ridley, Jane. [http://www.spectator.co.uk/books/5457543/from-madrid-with-love.thtml "From Madrid with Love"] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101207010519/http://www.spectator.co.uk/books/5457543/from-madrid-with-love.thtml |date= 7 December 2010 }} ''The Spectator'' via ''spectator.co.uk'', 24 October 2009. Retrieved: 4 August 2010.</ref> According to author [[William Stevenson (Canadian writer)|William Stevenson]] in ''A Man Called Intrepid'', his biography of [[William Stephenson|Sir William Samuel Stephenson]] (no relation), the senior representative of British Intelligence for the western hemisphere during the Second World War,<ref>Stevenson 2000, p. 179.</ref> Stephenson postulated that the Germans knew about Howard's mission and ordered the aircraft shot down. Stephenson further argued that Churchill knew in advance of the German intention to shoot down the aircraft, but allowed it to proceed to protect the fact that the British had broken the German Enigma code.<ref>[http://www.trueintrepid.com/CndPress.htm "Intrepid Book Brings Spy's Life From Shadows."] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110529122053/http://www.trueintrepid.com/CndPress.htm |date=29 May 2011 }} ''trueintrepid.com''. Retrieved: 23 July 2010.</ref> Former CIA agent Joseph B. Smith recalled that, in 1957, he was briefed by the National Security Agency on the need for secrecy and that Leslie Howard's death had been brought up. The NSA stated that Howard knew his aircraft was to be attacked by German fighters and risked himself to protect the British code-breakers.<ref>Smith 1976, p. 389.</ref> |

|||

A secretly taped account by one of the pilots involved appears in Sönke Neitzel and Harald Welzer's ''Soldiers: German POWs on Fighting, Killing, and Dying''. In a recently declassified transcript of a surreptitiously recorded conversation by two German Luftwaffe prisoners of war{{who|If one of them is one of the responsible pilots, and this must be specified, because it effectively debunks all the preceding circumstantial theories|date=August 2020}} talking about the shooting down of Howard's flight, one seems to express pride in his accomplishment, but states clearly he knew nothing of the passengers' identities or importance until hearing an English broadcast later that evening. Asked why he shot down a civil aircraft, he states it was one of four such planes he shot down: "Whatever crossed our path was shot down."<ref>Sönke Neitzel and Harald Welzer, ''Soldiers: German POWs on Fighting Killing, and Dying''. Translated by Jefferson Chase. Vintage Books (NY: 2013). p. 139.</ref> |

|||

The 2010 biography by Estel Eforgan, ''Leslie Howard: The Lost Actor'', examines then recently available evidence and concludes that Howard was not a specific target,<ref>Eforgan 2010, pp. 217–245.</ref> corroborating the statements by German sources that the shootdown was "an error in judgement".<ref name="N461">Matthews, Rowan. "N461: Howard & Churchill", ''n461.com '', 2003. Retrieved: 23 July 2010.</ref> |

|||

There is a monument in [[San Andrés de Teixido]], Spain, dedicated to the victims of the crash. Howard's aircraft was shot down over the sea north of this village.<ref>Castro, Jesus (translated by Rachael Harrison). [http://www.eyeonspain.com/blogs/jesuscastro/2961/the-actor-the-jew-and-churchill%E2%80%99s-double.aspx "The actor, the Jew and Churchill's double"] ''eyeonspain.com.'' Retrieved: 18 August 2011.</ref> |

|||

=== ''The Mystery of Flight 777'' (documentary) === |

|||

''[[The Mystery of Flight 777]]'', by film-maker Thomas Hamilton, explores the circumstances, theories and myths which have grown around the shooting down of Howard's plane. The film also aims to examine in detail some of the other passengers on board. Originally intended as a short companion piece to the Leslie Howard film, this project expanded in scope and as of January 2021 is still in production.{{cn|date=March 2024}} |

|||

==Biographies== |

==Biographies== |

||

Howard |

Howard's premature death preempted any autobiography. A compilation of his writings, ''Trivial Fond Records'', edited and with occasional comments by his son Ronald, was published in 1982. This book includes insights on his family life, first impressions of America and Americans when he first moved to the United States to act on Broadway, and his views on democracy in the years prior to and during the Second World War. |

||

Howard's son and daughter each published memoirs of their father: ''In Search of My Father: A Portrait of Leslie Howard'' (1984) by Ronald Howard, and ''A Quite Remarkable Father: A Biography of Leslie Howard'' (1959) by Leslie Ruth Howard. |

|||

Estel Eforgan's ''Leslie Howard: The Lost Actor'' is a full-length book biography published in 2010. |

Estel Eforgan's ''Leslie Howard: The Lost Actor'' is a full-length book biography published in 2010. |

||

===''Leslie Howard: The Man Who Gave a Damn''=== |

|||

''Leslie Howard: A Quite Remarkable Life'', a film documentary biography produced by Thomas Hamilton of Repo Films, was shown privately at the NFB Mediatheque, Toronto, Canada in September 2009 for contributors and supporters of the film. Subsequently re-edited and retitled "Leslie Howard: The Man Who Gave a Damn", the documentary was officially launched on 2 September 2011 in an event held at Leslie Howard's former home "Stowe Maries" in Dorking, and reported on BBC South News the same day.<ref>[http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9HRiDKqq1xw&noredirect=1 "Leslie Howard: The Man Who Gave A Damn-Premier".] ''Youtube'', 7 September 2011.</ref> Lengthy rights negotiations with Warners then delayed further screenings until May 2012, although the situation now appears to have been resolved and Repo Films now intends to enter the film into various International Film Festivals. |

|||

''Leslie Howard: A Quite Remarkable Life'', as it was initially known, is a film documentary biography produced by Thomas Hamilton of Repo Films. It was shown privately at the NFB Mediatheque, [[Toronto]], Canada in September 2009 for contributors and supporters of the film. Subsequently, re-edited and retitled ''[[Leslie Howard: The Man Who Gave a Damn]]'', the documentary was officially launched on 2 September 2011 in an event held at Howard's former home "Stowe Maries" in [[Dorking]], and reported on [[BBC South]] News the same day.<ref>{{YouTube|9HRiDKqq1xw|"Leslie Howard: The Man Who Gave A Damn-Premier"}}, 7 September 2011.</ref> Lengthy rights negotiations with [[Warners]] then delayed further screenings until May 2012. |

|||

From 2012 to early 2014 the film remained in limbo due to these issues. However, in early 2014, independent producer [[Monty Montgomery (producer)|Monty Montgomery]] and Hamilton entered a co-production agreement to complete and release the documentary. This involved a complete re-edit of the documentary, from June 2014 to February 2015, with added material including archival interviews ([[Michael Powell]], [[John Houseman]], [[Ronald Howard (British actor)|Ronald Howard]] and [[Irene Howard]] - all originally filmed in 1980 for the BBC's [[British Greats]] series), much historical footage and an additional interview. In addition a score was commissioned from composer [[Maria Antal]] and considerable post-production sweetening was undertaken on the original material. |

|||

==Filmography== |

|||

{|class=wikitable |

|||

This new version, of '' Leslie Howard: The Man Who Gave a Damn'' was screened as a "work in progress" at the [[San Francisco Mostly British Film Festival]] on 14 February 2015, with Hamilton, Tracy Jenkins and [[Derek Partridge]] in attendance. The film won the award for Best Documentary Film. |

|||

! rowspan=2|Year |

|||

Subsequent screenings (with minor changes to the commentary) took place at the [[Chichester International Film Festival]] on 18 August 2015 at the [[Regent Street Cinema]], London in December 2015 and at the [[Margaret Mitchell Museum]] in Atlanta in May 2016 as part of the [[Britweek Atlanta]] launch. |

|||

''Leslie Howard: The Man Who Gave a Damn'' had its world premiere broadcast on [[Talking Pictures TV]] on 27 December 2017, followed by the US TV premiere on [[Turner Classic Movies]] on 4 June 2018, which opened a month-long tribute to Howard's films.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/2140483/Leslie-Howard-The-Man-Who-Gave-a-Damn/ |title=Leslie Howard: The Man Who Gave a Damn |publisher=[[Turner Classic Movies|TCM]] |access-date=2018-06-05 }}</ref> It airs regularly on Talking Pictures TV and occasionally on Turner Classic Movies. |

|||

==Complete filmography== |

|||

{|class="wikitable sortable" |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan=2| Year |

|||

! rowspan=2| Country |

! rowspan=2| Country |

||

! rowspan=2| Title |

! rowspan=2| Title |

||

! colspan= |

! colspan=6| Credited as |

||

|- |

|- |

||

! |

! style="width:10%;"|Director |

||

! |

! style="width:10%;"|Producer |

||

! |

! style="width:10%;"|Actor |

||

! style="width:10%;"|Screenwriter |

|||

! Role |

! Role |

||

! Notes |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| 1914 |

| 1914 |

||

| UK |

|||

| Great Britain |

|||

| ''The Heroine of Mons'' |

| ''{{sort|her|[[The Heroine of Mons]]}}'' |

||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

|||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| Short |

|||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| cast member |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| 1917 |

| 1917 |

||

| UK |

|||

| Great Britain |

|||

| ''The Happy Warrior'' |

| ''{{sort|hap|[[The Happy Warrior (1917 film)|The Happy Warrior]]}}'' |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

|||

| Rollo |

| Rollo |

||

| |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| 1919 |

| 1919 |

||

| UK |

|||

| Great Britain |

|||

| ''[[The Lackey and the Lady]]'' |

| ''{{sort|lac|[[The Lackey and the Lady]]}}'' |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| Tony Dunciman |

|||

|- |

|||

| rowspan=5|1920 |

|||

| Great Britain |

|||

| ''Twice Two'' |

|||

| |

|||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| |

| |

||

| {{sort|dun|Tony Dunciman}} |

|||

| |

| |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| {{sort|1920.1|1920}} |

|||

| Great Britain |

|||

| UK |

|||

| ''The Temporary Lady'' |

|||

| ''Twice Two'' |

|||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

|||

| Short |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| {{sort|1920.2|1920}} |

|||

| Great Britain |

|||

| UK |

|||

| ''The Bump'' |

|||

| ''{{sort|bump|The Bump}}'' |

|||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

|||

| Short |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| {{sort|1920.3|1920}} |

|||

| Great Britain |

|||

| UK |

|||

| ''Bookworms'' |

| ''Bookworms'' |

||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

|||

| Richard |

| Richard |

||

| Short |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| {{sort|1920.4|1920}} |

|||

| Great Britain |

|||

| UK |

|||

| '' Reward'' |

|||

| ''Five Pounds Reward'' |

|||

| |

|||

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

|||

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

|||

| |

| |

||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| Tony Marchmont |

| Tony Marchmont |

||

| Short |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| 1921 |

| {{sort|1921.1|1921}} |

||

| UK |

|||

| Great Britain |

|||

| '' |

| ''Two Many Cooks'' |

||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

|||

| Short |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| {{sort|1921.2|1921}} |

|||

| 1930 |

|||

| UK |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|United States |

|||

| ''{{sort|temp|The Temporary Lady}}'' |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|''[[Outward Bound (film)|Outward Bound]]'' |

|||

| |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF| |

|||

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF| |

|||

| |

|||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|Tom Prior |

|||

| |

|||

| Short |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| 1930 |

|||

| rowspan=4|1931 |

|||

| US |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF| United States |

|||

| |

| ''[[Outward Bound (film)|Outward Bound]]'' |

||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF| |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF| |

|||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|Bertram "Berry" Rhodes |

|||

|- bgcolor=#F0F8FF |

|||

| United States |

|||

| ''[[Devotion (1931 film)|Devotion]]'' |

|||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| David Trent |

|||

|- bgcolor=#F0F8FF |

|||

| United States |

|||

| ''[[A Free Soul]]'' |

|||

| |

| |

||

| {{sort|pri|Tom Prior}} |

|||

| |

| |

||

|- |

|||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| {{sort|1931.1|1931}} |

|||

| Dwight Winthrop |

|||

| US |

|||

|- bgcolor=#F0F8FF |

|||

| United States |

|||

| ''[[Never the Twain Shall Meet (1931 film)|Never the Twain Shall Meet]]'' |

| ''[[Never the Twain Shall Meet (1931 film)|Never the Twain Shall Meet]]'' |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

|||

| Dan Pritchard |

|||

| {{sort|pri|Dan Pritchard}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| {{sort|1931.2|1931}} |

|||

| rowspan=3|1932 |

|||

| US |

|||

| Great Britain |

|||

| ''[[ |

| ''{{sort|fre|[[A Free Soul]]}}'' |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

|||

| Max Tracey |

|||

| {{sort|win|Dwight Winthrop}} |

|||

|- bgcolor=#F0F8FF |

|||

| |

|||

| United States |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{sort|1931.3|1931}} |

|||

| US |

|||

| ''[[Five and Ten (1931 film)|Five and Ten]]'' |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

|||

| |

|||

| {{sort|rho|Bertram "Berry" Rhodes}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{sort|1931.4|1931}} |

|||

| US |

|||

| ''[[Devotion (1931 film)|Devotion]]'' |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

|||

| |

|||

| {{sort|tre|David Trent}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{sort|1932.1|1932}} |

|||

| UK |

|||

| ''[[Service for Ladies (1932 film)|Service for Ladies]]'' |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

|||

| |

|||

| {{sort|tra|Max Tracey}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{sort|1932.2|1932}} |

|||

| US |

|||

| ''[[Smilin' Through (1932 film)|Smilin' Through]]'' |

| ''[[Smilin' Through (1932 film)|Smilin' Through]]'' |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| Sir John Carteret |

|||

|- bgcolor=#F0F8FF |

|||

| United States |

|||

| ''[[The Animal Kingdom]]'' |

|||

| |

| |

||

| {{sort|cart|Sir John Carteret}} |

|||

| |

| |

||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| Tom Collier |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| {{sort|1932.3|1932}} |

|||

| rowspan=3|1933 |

|||

| US |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|United States |

|||

| |

| ''{{sort|ani|[[The Animal Kingdom (1932 film)|The Animal Kingdom]]}}'' |

||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF| |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF| |

|||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|Peter Standish |

|||

|- bgcolor=#F0F8FF |

|||

| United States |

|||

| ''[[Captured!]]'' |

|||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

|||

| Captain Fred Allison |

|||

| {{sort|col|Tom Collier}} |

|||

|- bgcolor=#F0F8FF |

|||

| |

|||

| United States |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{sort|1933.1|1933}} |

|||

| US |

|||

| ''[[Secrets (1933 film)|Secrets]]'' |

| ''[[Secrets (1933 film)|Secrets]]'' |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

|||

| John Carlton |

|||

| {{sort|car|John Carlton}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| {{sort|1933.2|1933}} |

|||

| rowspan=3|1934 |

|||

| US |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|United States |

|||

| |

| ''[[Captured!]]'' |

||

| |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF| |

|||

| |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF| |

|||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|Stephen "Steve" Locke |

|||

| {{sort|all|Captain Fred Allison}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| {{sort|1933.3|1933}} |

|||

| Great Britain |

|||

| US |

|||

| ''[[The Lady Is Willing (1934 film)|The Lady Is Willing]]'' |

|||

| ''[[Berkeley Square (1933 film)|Berkeley Square]]'' |

|||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

|||

| Albert Latour |

|||

| {{sort|sta|Peter Standish}} |

|||

|- bgcolor=#F0F8FF |

|||

| |

|||

| United States |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{sort|1934.1|1934}} |

|||

| US |

|||

| ''[[Of Human Bondage (1934 film)|Of Human Bondage]]'' |

| ''[[Of Human Bondage (1934 film)|Of Human Bondage]]'' |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

|||

| Philip Carey |

|||

| {{sort|car|Philip Carey}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| {{sort|1934.2|1934}} |

|||

| 1935 |

|||

| UK |

|||

| Great Britain |

|||

| ''[[The |

| ''{{sort|lad|[[The Lady Is Willing (1934 film)|The Lady Is Willing]]}}'' |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

|||

| [[The Scarlet Pimpernel|Sir Percy Blakeney]] |

|||

| {{sort|lat|Albert Latour}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{sort|1934.3|1934}} |

|||

| US |

|||

| ''[[British Agent]]'' |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

|||

| |

|||

| {{sort|loc|Stephen "Steve" Locke}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{sort|1934.4|1934}} |

|||

| UK |

|||

| ''{{sort|sca|[[The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934 film)|The Scarlet Pimpernel]]}}'' |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

|||

| |

|||

| {{sort|sca|[[The Scarlet Pimpernel|Sir Percy Blakeney]]}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{sort|1936.1|1936}} |

|||

| US |

|||

| ''{{sort|pet|[[The Petrified Forest]]}}'' |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

|||

| |

|||

| {{sort|squ|Alan Squier}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| |

| {{sort|1936.2|1936}} |

||

| US |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|United States |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|''[[The Petrified Forest]]'' |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF| |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF| |

|||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|Alan Squier |

|||

|- bgcolor=#F0F8FF |

|||

| United States |

|||

| ''[[Romeo and Juliet (1936 film)|Romeo and Juliet]]'' |

| ''[[Romeo and Juliet (1936 film)|Romeo and Juliet]]'' |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

|||

| [[Romeo Montague|Romeo]] |

| [[Romeo Montague|Romeo]] |

||

| |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| |

| {{sort|1937.1|1937}} |

||

| US |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|United States |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|''[[Stand-In]]'' |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF| |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF| |

|||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|Atterbury Dodd |

|||

|- bgcolor=#F0F8FF |

|||

| United States |

|||

| ''[[It's Love I'm After]]'' |

| ''[[It's Love I'm After]]'' |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

|||

| Basil Underwood |

|||

| {{sort|und|Basil Underwood}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{sort|1937.2|1937}} |

|||

| US |

|||

| ''[[Stand-In]]'' |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

|||

| |

|||

| {{sort|dod|Atterbury Dodd}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| 1938 |

| 1938 |

||

| UK |

|||

| Great Britain |

|||

| ''[[Pygmalion (1938 film)|Pygmalion]]'' |

| ''[[Pygmalion (1938 film)|Pygmalion]]'' |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

|||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

|||

| [[Pygmalion (play)|Professor Henry Higgins]] |

|||

| {{sort|hig|[[Pygmalion (play)|Professor Henry Higgins]]}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{sort|1939.1|1939}} |

|||

| US |

|||

| ''[[Intermezzo (1939 film)|Intermezzo]]'' |

|||

| |

|||

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

|||

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

|||

| |

|||

| {{sort|bra|Holger Brandt}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| |

| {{sort|1939.2|1939}} |

||

| US |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|United States |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|''[[Intermezzo (1939 film)|Intermezzo]]'' |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF| |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF| |

|||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| bgcolor=#F0F8FF|Holger Brandt |

|||

|- bgcolor=#F0F8FF |

|||

| United States |

|||

| ''[[Gone with the Wind (film)|Gone with the Wind]]'' |

| ''[[Gone with the Wind (film)|Gone with the Wind]]'' |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| align |

| style="text-align:center; background:#90ff90;"|Yes |

||

| |

|||

| [[Ashley Wilkes]] |

|||

| {{sort|wil|[[Ashley Wilkes]]}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| 1940 |

|||

| rowspan=5|1941 |

|||

| UK |

|||

| Great Britain |

|||

| ''[["Pimpernel" Smith]]'' |

|||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| Professor Horatio Smith |

|||

|- |

|||

| Great Britain |

|||

| ''Common Heritage'' |

| ''Common Heritage'' |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

|||

| align=center bgcolor=#90ff90|Yes |

|||

| |

|||

| Himself |

|||