Free love: Difference between revisions

Most art historians agree that Bosch's painting is not at all a means of supporting "free love". In fact, it is quite the opposite. The Garden of Earthly Delights has a moralizing theme. In it, he warns viewers about the dangers of sin. Tag: section blanking |

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

||

| (394 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Social movement that accepts all forms of love}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=August 2013}} |

|||

{{About|the social movement||Free Love (disambiguation){{!}}Free Love}} |

|||

{{Love sidebar |In history}} |

|||

{{use American English|date=February 2019}} |

|||

{{Libertarian socialism |Concepts}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=January 2024}} |

|||

{{multiple image |

|||

| border = thumb |

|||

| perrow = 1/2/2 |

|||

| total_width = 280 |

|||

| image1 = 20110715204810!Tahquitz 1.jpg |

|||

| crop = 1000 |

|||

| alt1 = |

|||

| image2 = CL Society 630.jpg |

|||

| alt2 = |

|||

| image3 = Decicca 201205 12.jpg |

|||

| alt3 = |

|||

| image4 = CL Society 38- Kiss at protest.jpg |

|||

| alt4 = |

|||

| image5 = Snow White Christmas raid -10- (50433977138).png |

|||

| align = <center>'''Clockwise from top''':</center> |

|||

| footer_align = center |

|||

| footer = Free love |

|||

| direction = |

|||

}} |

|||

{{love sidebar|social}} |

|||

'''Free love''' is a [[social movement]] that accepts all forms of [[love]]. The movement's initial goal was to separate the [[State (polity)|state]] from sexual and romantic matters such as [[marriage]], [[birth control]], and [[adultery]]. It stated that such issues were the concern of the people involved and no one else.<ref>McElroy, Wendy. "The Free Love Movement and Radical Individualism." Libertarian Enterprise .19 (1996): 1.</ref> The movement began during the 19th century and was advanced by [[hippies]] during the 1960s and early 70s. |

|||

{{TOC limit|limit=3}} |

|||

== Principles == |

|||

'''Free love''' is a [[social movement]] that rejects [[:marriage]], which is seen as a form of social and financial bondage. The Free Love movement's initial goal was to separate the state from sexual matters such as marriage, [[birth control]], and [[adultery]]. It claimed that such issues were the concern of the people involved, and no one else.<ref>McElroy, Wendy. "The Free Love Movement and Radical Individualism." Libertarian Enterprise .19 (1996): 1.</ref> |

|||

Much of the free love tradition reflects a [[Liberalism|liberal]] philosophy that seeks [[freedom (political)|freedom]] from [[State (polity)|state]] regulation and [[Christian Church|church]] interference in [[personal relationship]]s. According to this concept, the [[free union]]s of [[adult]]s (or persons at or above the [[age of consent]]) are legitimate relations which should be respected by all third parties whether they are emotional or sexual relations. In addition, some free love writing has argued that both men and women have the [[Right to sexuality|right to sexual pleasure]] without social or legal restraints. In the [[Victorian era]], this was a radical notion. Later, a new theme developed, linking free love with radical social change and depicting it as a [[wikt:harbinger|harbinger]] of a new [[Anti-authoritarianism|anti-authoritarian]], anti-repressive sensibility.<ref>{{cite web|author=Dan Jakopovich |title=Chains of Marriage|work=Peace News|url=http://www.peacenews.info/webextras/article.php?id=33 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110514004631/http://www.peacenews.info/webextras/article.php?id=33 |url-status=dead|archive-date=14 May 2011}}</ref> |

|||

According to the modern stereotype, earlier middle-class Americans wanted the home to be a place of stability in an uncertain world. To this mentality are attributed strongly defined gender roles, which led to a minority reaction in the form of the free-love movement.<ref name="Spurlock, John C 1988">Spurlock, John C. Free Love Marriage and Middle-Class Radicalism in America. New York: New York UP, 1988.</ref> |

|||

Much of the free-love tradition is an offshoot of [[anarchism]], and reflects a [[Libertarianism|libertarian]] philosophy that seeks [[freedom (political)|freedom]] from [[State (polity)|state]] regulation and [[Christian Church|church]] interference in [[personal relationship]]s. According to this concept, the [[free union]]s of [[adult]]s are legitimate relations which should be respected by all third parties whether they are emotional or sexual relations. In addition, some free-love writing has argued that both men and women have the right to sexual pleasure without social or legal restraints. In the [[Victorian era]], this was a radical notion. Later, a new theme developed, linking free love with radical social change, and depicting it as a [[wikt:harbinger|harbinger]] of a new [[Anti-authoritarianism|anti-authoritarian]], anti-repressive sensibility.<ref>[http://www.peacenews.info/webextras/article.php?id=33 Dan Jakopovich, ''Chains of Marriage'', Peace News]</ref> |

|||

While the phrase ''free love'' is often associated with [[promiscuity]] in the popular imagination, especially in reference to the [[counterculture of the 1960s]] and 1970s, historically, the free-love movement has not advocated multiple sexual partners or short-term sexual relationships. Rather, it has argued that sexual relations that are freely entered into should not be regulated by law, and may be initiated or terminated by the parties involved at will.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Aviram|first=Hadar|date=1 July 2008|title=Make Love, Now Law: Perceptions of the Marriage Equality Struggle Among Polyamorous Activists|url=https://doi.org/10.1080/15299710802171332|journal=Journal of Bisexuality|volume=7|issue=3–4|pages=261–286|doi=10.1080/15299710802171332|s2cid=143940591|issn=1529-9716}}</ref> Nevertheless, it has been acknowledged that many men who participated in the free love movement also saw free love as a way to get free sex.<ref name=menandwomenroles>{{cite news|url=https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna19053382|title=Free love: Was there a price to pay?|first=Brian|last=Alexander|publisher=NBC News|date=July 19, 2024|accessdate=July 19, 2024}}</ref> |

|||

Most people until the late 20th century believed that marriage was an important aspect of life to "fulfil earthly human happiness." According to today's stereotype, earlier middle-class Americans wanted the home to be a place of stability in an uncertain world. To this mentality are attributed strongly defined gender roles, which led to a minority reaction in the form of the free love movement.<ref name="Spurlock, John C 1988">Spurlock, John C. Free Love Marriage and Middle-Class Radicalism in America. New York, NY: New York UP, 1988.</ref> |

|||

The term "sex radical" is often used interchangeably with the term "free lover".<ref name="Mendelman-2019">{{cite book |last=Mendelman |first=Lisa |title=Modern Sentimentalism: Affect, Irony, and Female Authorship in Interwar America |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DarDDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA197 |access-date=19 April 2020 |series=Oxford studies in American literary history |year= 2019 |publisher=OUP |location=Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-258971-2 |pages=197– |oclc=1140202743 |archive-date=25 June 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210625214803/https://books.google.com/books?id=DarDDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA197 |url-status=live }}</ref> By whatever name, advocates had two strong beliefs: opposition to the idea of forced sexual activity in a relationship and advocacy for a woman to use her body in any way that she pleases.<ref name="Passet, Joanne E 2003">Passet, Joanne E. Sex Radicals and the Quest for Women's Equality. Chicago, IL: U of Illinois P, 2003.</ref> |

|||

While the phrase ''free love'' is often associated with [[promiscuity]] in the popular imagination, especially in reference to the [[counterculture of the 1960s]] and 1970s, historically the free-love movement has not advocated multiple sexual partners or short-term sexual relationships. Rather, it has argued that love relations that are freely entered into should not be regulated by law. |

|||

Laws of particular concern to free love movements have included those that prevent an unmarried couple from living together, and those that regulate [[:adultery]] and [[:divorce]], as well as [[:age of consent]], [[:birth control]], [[:homosexuality]], [[:abortion]], and sometimes [[:prostitution]]; although not all free-love advocates agree on these issues. The abrogation of individual rights in marriage is also a concern—for example, some jurisdictions do not recognize [[spousal rape]], or they treat it less seriously than non-spousal rape. Free-love movements since the 19th century have also defended the right to publicly discuss sexuality and have battled [[obscenity]] laws. |

|||

The term "sex radical" is also used interchangeably with the term "free lover", and was the preferred term by advocates because of the negative connotations of "free love".{{Citation needed|date=February 2010}} By whatever name, advocates had two strong beliefs: opposition to the idea of forceful sexual activity in a relationship and advocacy for a woman to use her body in any way that she pleases.<ref name="Passet, Joanne E 2003">Passet, Joanne E. Sex Radicals and the Quest for Women's Equality. Chicago,IL: U of Illinois P, 2003.</ref> |

|||

===Relationship to feminism=== |

|||

Laws of particular concern to free love movements have included those that prevent an unmarried couple from living together, and those that regulate [[:adultery]] and [[:divorce]], as well as [[:age of consent]], [[:birth control]], [[:homosexuality]], [[:abortion]], and sometimes [[:prostitution]]; although not all free love advocates agree on these issues. The abrogation of individual rights in marriage is also a concern—for example, some jurisdictions do not recognize [[spousal rape]] or treat it less seriously than non-spousal rape. Free-love movements since the 19th century have also defended the right to publicly discuss sexuality and have battled [[obscenity]] laws. |

|||

{{See also|Sex-positive feminism}} |

|||

The history of free love is entwined with the history of [[feminism]]. From the late 18th century, leading feminists, such as [[Mary Wollstonecraft]], have challenged the institution of marriage, and many have advocated its abolition.<ref name="historyguide1">Kreis, Steven. "Mary Wollstonecraft, 1759–1797". The History Guide. 23 November 2009 <http://www.historyguide.org/intellect/wollstonecraft.html {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140111055540/http://www.historyguide.org/intellect/wollstonecraft.html |date=11 January 2014 }}>.</ref> |

|||

According to feminist critique, a married woman was solely a wife and mother, denying her the opportunity to pursue other occupations; sometimes this was legislated, as with bans on married women and mothers being employed as [[teacher]]s. In 1855, free love advocate [[Mary Gove Nichols]] (1810–1884) described marriage as the "annihilation of woman", explaining that women were considered to be men's property in [[coverture|law]] and public sentiment, making it possible for tyrannical men to deprive their wives of all freedom.<ref name="Gove-NicholsAuto1855">{{cite book |title=Mary Lyndon, or Revelations of a Life. An Autobiography |url=https://archive.org/stream/marylyndonorreve00nich#page/166/mode/2up |last=Nichols | first=Mary S. Gove|author-link=Talk:Free love#Mary Sargeant Gove Nichols|year=1855| publisher=Stringer & Townsend | location=New York | page=166|access-date=14 January 2009}} Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org).</ref><ref>Nichols, Mary Gove, 1855. ''Mary Lyndon: Revelations of a Life''. New York: Stringer and Townsend; p. 166. Quoted in [http://www.h-net.org/~women/papers/freelove.html Feminism and Free Love] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060115040524/http://www.h-net.org/~women/papers/freelove.html |date=15 January 2006 }}</ref> For example, the law often allowed a husband to beat his wife. Free-love advocates argued that many children were born into unloving marriages out of compulsion, but should instead be the result of choice and affection—yet children born out of wedlock did not have the same rights as children with married parents.<ref name="Silver-Isenstadt2002">{{cite book | title=Shameless: The Visionary Life of Mary Gove Nichols | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jmGUJudA3bsC&pg=PP21 | last=Silver-Isenstadt | first=Jean L | year=2002 | publisher=The Johns Hopkins University Press | location=Baltimore, Maryland | isbn=978-0-8018-6848-1 | access-date=14 December 2009 | archive-date=14 June 2016 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160614061408/https://books.google.com/books?id=jmGUJudA3bsC&pg=PP21 | url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

In 1857, [[Francis Barry (philosopher)|Francis Barry]] wrote that "marriage is a system of rape," stating that the woman is a victim where she can do nothing but be oppressed by her husband, as he tortures her in her home, which becomes a house of bondage.<ref>e. Spurlock, John. "A Masculine View of Women's Freedom: Free Love in the Nineteenth Century." International Social Science Review 69.3/4 (1994): 34–45. Print.</ref> In one of his articles, Barry wrote: |

|||

In 1857, in the ''Social Revolutionist'', Minerva Putnam complained that "in the discussion of free love, no woman has attempted to give her views on the subject" and challenged every woman reader to "rise in the dignity of her nature and declare herself free."<ref>Joanne E. Passet, ''Grassroots feminists: women, free love, and the power of print'' (1999), p. 119</ref> |

|||

<blockquote>'The Object of this [women’s emancipation] Society,’ according to Article 2 of its [free love] constitution, ‘shall be to secure absolute freedom to woman, through the overthrow of the popular system of marriage.’<ref name="Spurlock, John 1994">Spurlock, John. "A Masculine View of Women's Freedom: Free Love in the Nineteenth Century." International Social Science Review 69.3/4 (1994): 34–45. Print.</ref></blockquote> |

|||

The figureheads of the free love movement were often men, both in leading organizations and contributing to its ideology. Almost all books endorsing free love in the 1850s were by men, except for [[Mary Gove Nichols]]'s 1855 autobiography.<ref>Spurlock 1994, p. 36</ref> This was the first full-length case against marriage written by a woman.<ref>Spurlock 1994, p. 37</ref> Of the four major free-love periodicals in the [[Reconstruction era]], half had woman editors.<ref>Spurlock 1994, p. 36</ref><ref name="Spurlock, John 1994">Spurlock, John. "A Masculine View of Women's Freedom: Free Love in the Nineteenth Century." International Social Science Review 69.3/4 (1994): 34–45. Print. {{jstor|41882150}}</ref> |

|||

At the turn of the 20th century, some free-love proponents extended the critique of marriage to argue that marriage as a social institution encourages emotional possessiveness and psychological enslavement.{{Citation needed|date=August 2009}} |

|||

To proponents of free love, the act of sex was not just about reproduction. Access to [[birth control]] was considered a means to women's independence, and leading birth-control activists also embraced free love. Sexual radicals remained focused on their attempts to uphold a woman's right to control her body and to freely discuss issues such as [[contraception]], marital-sex abuse (emotional and physical), and [[sexual education]]. These people believed that by talking about female sexuality, they would help empower women. To help achieve this goal, such radical thinkers relied on the written word, books, pamphlets, and periodicals, and by these means the movement was sustained for over fifty years, spreading the message of free love all over the United States.<ref>Passet, Joanne E. Sex Radicals and the Quest for Women's Equality. |

|||

{{TOC limit|limit=3}} |

|||

Chicago, IL: U of Illinois P, 2003.</ref> However, many feminists would point out that the 1960s free love movement did not significantly change views about women's role in mainstream America.<ref name=menandwomenroles /> [[Haight Ashbury Free Clinics|Haight-Ashbury Free Clinic]] founder Dr. David Smith, who was a prominent participant in the 1967 [[Summer of Love]], acknowledged in 2007 how many of the men who participated in the event viewed women as prone.<ref name=menandwomenroles /> |

|||

==History== |

|||

==Free love and the women's movement== |

|||

{{See also|Sex-positive feminism}} |

|||

The history of free love is entwined with the history of [[:feminism]]. From the late 18th century, leading feminists, such as [[Mary Wollstonecraft]], have challenged the institution of marriage, and many have advocated its abolition. Wollstonecraft was one of the first women to contribute to the free love movement with her literary works. Her novels criticized the social construction of marriage and its effects on women. In her first novel, ''Mary: A Fiction'' written in 1788, the heroine is forced into a loveless marriage for economic reasons. She finds love in relationships with another man and a woman. The novel, ''Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman'', never finished but published in 1798, revolves around the story of a woman imprisoned in an asylum by her husband; Maria finds fulfilment outside of marriage, in an affair with a fellow inmate. Mary makes it clear that "women had strong [[sexual desire]]s and that it was degrading and immoral to pretend otherwise.”<ref>Kreis, Steven. "Mary Wollstonecraft, 1759–1797". The History Guide. 23 November 2009 <http://www.historyguide.org/intellect/wollstonecraft.html>.</ref> |

|||

===Early precedents=== |

|||

According to feminist stereotype, and to some extent in actuality, a married woman was solely a wife and mother, denying her the opportunity to pursue other occupations; sometimes this was legislated, as with bans on married women and mothers in the [[Teacher|teaching]] profession. In 1855, free love advocate Mary Gove Nichols (1810–1884) described marriage as the "annihilation of woman," explaining that women were considered to be men's property in law and public sentiment, making it possible for tyrannical men to deprive their wives of all freedom.<ref name="Gove-NicholsAuto1855">{{cite book |title=Mary Lyndon, or Revelations of a Life. An Autobiography | volume=|url=http://www.archive.org/stream/marylyndonorreve00nich#page/166/mode/2up |last=Gove Nichols | first=Mary S. |authorlink=Talk:Free love#Mary Sargeant Gove Nichols|year=1855| publisher=Stringer & Townsend | location=New York | page=166|accessdate=14 January 2009}} Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org).</ref><ref>Nichols, Mary Gove, 1855. ''Mary Lyndon: Revelations of a Life''. New York: Stringer and Townsend; p. 166. Quoted in [http://www.h-net.org/~women/papers/freelove.html Feminism and Free Love]</ref> For example, the law sometimes allowed a husband to physically discipline his wife. Free-love advocates like Nichols argued that many children are born into unloving marriages out of compulsion, but should instead be the result of choice and affection—yet children born out of wedlock did not have the same rights as children with married parents.<ref name="Silver-Isenstadt2002">{{cite book | title=Shameless: The Visionary Life of Mary Gove Nichols | url= http://books.google.com.au/books?id=jmGUJudA3bsC&pg=PP21#v=onepage&q=&f=false | last=Silver-Isenstadt| first=Jean L | year=2002 | publisher=The Johns Hopkins University Press | location=Baltimore, Maryland | page=|isbn=0-8018-6848-3 | accessdate=14 December 2009}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:The arrest of Adamites in a public square in Amsterdam. Etch Wellcome V0035701.jpg|thumb|The [[Adamites]] were a sect that rejected marriage. Pictured, they are being rounded up for their supposedly [[Heresy|heretical]] views.]] |

|||

A number of utopian social movements throughout history have shared a vision of free love. An [[early Christian]] sect known as the [[Adamites]] existed in North Africa in the 2nd, 3rd and 4th centuries and rejected marriage. They practiced [[nudism]] and believed themselves to be without [[original sin]]. |

|||

In the 6th century, adherents of [[Mazdakism]] in pre-Muslim [[Persia]] apparently supported a kind of free love in the place of marriage.<ref>Crone, Patricia, ''Kavad's Heresy and Mazdak's Revolt'', in: Iran 29 (1991), S. 21–40</ref> One folk story from the period that contains a mention of a free-love (and [[Naturism|nudist]]) community under the sea is "The Tale of Abdullah the Fisherman and Abdullah the Merman" from ''[[The Book of One Thousand and One Nights]]'' ({{Circa|10th–12th century}}).<ref>Irwin, Robert, ''Political Thought in The Thousand and One Nights'', in: Marvels & Tales – Volume 18, Number 2, 2004, pp. 246–257. Wayne State University Press</ref> |

|||

Sex, to proponents of free love, was not only about reproduction. Access to birth control was considered a means to women's independence, and leading birth-control activists like [[Margaret Sanger]] also embraced free love. |

|||

[[Karl Kautsky]], writing in 1895, noted that a number of "communistic" movements throughout the Middle Ages also rejected marriage.<ref>[[Karl Kautsky|Kautsky, Karl]] (1895), ''Die Vorläufer des neuen Sozialismus, vol. I: Kommunistische Bewegungen in Mittelalter'', Stuttgart: J.W. Dietz.</ref> Typical of such movements, the [[Cathar]]s of 10th to 14th century Western Europe freed followers from all moral prohibition and religious obligation, but respected those who lived simply, avoided the taking of human or animal life, and were celibate. Women had an uncommon equality and autonomy, even as religious leaders. The Cathars and similar groups (the [[Waldenses]], Apostle brothers, [[Beghards]] and [[Beguines]], [[Lollards]], and [[Hussites]]) were branded as [[heresy|heretics]] by the Roman Catholic Church and suppressed. Other movements shared their critique of marriage but advocated free sexual relations rather than celibacy, such as the [[Brethren of the Free Spirit]], [[Taborite]]s, and [[Picards]]. |

|||

In the 1850s, [[Hannah R. Brown]] contributed to the journal, the “Una,” made lecture tours, and edited her personal journal, “the Agitator.” In one of her articles, she stated, “the woman is regarded as a sort of appendage to the goods and glories [of a man].” She advocated that true marriages could be formed if only women were allowed to choose freely.<ref name="Spurlock, John C 1988"/> |

|||

Free love was an element in radical thinking during the "[[English Revolution]]" of 1640–1660, most strongly associated with the "[[Ranters]]".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hill |first=Christopher |title=The World Turned Upside Down |publisher=Penguin Books |year=1972}}</ref> <ref>{{Cite web |last=Morton |first=A. L. |title=A Glorious Liberty |date=15 August 2012 |url=https://www.brh.org.uk/site/articles/a-glorious-liberty/ |access-date=16 March 2023}}</ref> There were also perceptive critiques, within these radical movements, such as by [[Gerrard Winstanley]]: <blockquote>The mother and child begotten in this manner is like to have the worst of it, for the man will be gone and leave them ... after he hath had his pleasure. ..... By seeking their own freedom they embondage others. <ref>{{Cite book |last=Hill |first=Christopher |title=The World Turned Upside Down |publisher=Penguin Books |year=1972 |pages=319}}</ref></blockquote> |

|||

Francis Barry was also a prominent advocate for the free love movement in the middle to late 19th century. He agreed that marriage socially bound a woman to a man, and that women should be free. Although this movement largely concerned women, the chief organizers were mostly men, one of them being Francis Barry. This helped foster a male ideology, and proved to women, such as [[Mary Gove Nichols]] and [[Victoria Woodhull]] that some men were just as serious as they were about this issue. Although men were the main contributors to the organized and written part of the free love movement, the movement itself was still associated with loud and flashy women. There were two reasons that free love was more agreeable to men. The first reason was that women lost more than men did, if marriage were to become “undermined.” The second reason was that free love “rested on the faith in individualism,” a quality that most women were afraid of or unable to accept.<ref name="Spurlock, John 1994"/> |

|||

===Enlightenment thought=== |

|||

In 1857, [[Minerva Putnam]] complained that, “in the discussion of free love, no woman has attempted to give her views on the subject.” There were six books during this time that endorsed the concept of free love. Of the four major free love periodicals following the civil war, only two of them had female editors. Mary Gove Nichols was the leading female advocate, and the woman who most people looked up to, for the free love movement. She wrote her autobiography, which became the first case against marriage written from a woman's point of view.<ref name="Spurlock, John 1994"/> |

|||

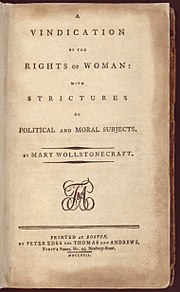

[[File:Vindication1b.jpg|thumb|upright=0.8|left|alt=Title page reads "A VINDICATION OF THE RIGHTS OF WOMAN: WITH STRICUTRES ON POLITICAL AND MORAL SUBJECTS. BY MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT. PRINTED AT BOSTON, BY PETER EDES FOR THOMAS AND ANDREWS, Faust's Statue, No. 45, Newbury-Street, MDCCXCII."|Title page from ''[[A Vindication of the Rights of Woman]]'' (1792), by [[Mary Wollstonecraft]], an early feminist and proponent of free love.]] |

|||

The ideals of free love found their champion in one of the earliest English [[feminism|feminists]], [[Mary Wollstonecraft]]. In her writings, Wollstonecraft challenged the institution of marriage, and advocated its abolition. Her novels criticized the social construction of marriage and its effects on women. In her first novel, ''Mary: A Fiction'' written in 1788, the heroine is forced into a loveless marriage for economic reasons. She finds love in relationships with another man and a woman. The novel, ''Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman'', never finished but published in 1798, revolves around the story of a woman imprisoned in an asylum by her husband. Maria finds fulfilment outside of marriage, in an affair with a fellow inmate. Wollstonecraft makes it clear that "women had strong [[sexual desire]]s and that it was degrading and immoral to pretend otherwise."<ref name="historyguide1"/> |

|||

Sex radicals remained focused on their attempts to uphold a woman's right to control her body and to freely discuss issues such as contraception, marital sex abuse (emotional and physical), and sexual education. These people believed that by talking about female sexuality, they would help empower women. To help achieve this goal, sex radicals relied on the written word, books, pamphlets, and periodicals. This method helped these people sustain this movement for over 50 years, and helped spread their message all over the United States.<ref>Passet, Joanne E. Sex Radicals and the Quest for Women's Equality. |

|||

Chicago,IL: U of Illinois P, 2003.</ref> |

|||

Wollstonecraft felt that women should not give up freedom and control of their sexuality, and thus did not marry her partner, [[Gilbert Imlay]], despite the two conceiving and having a child together in the midst of the [[Reign of Terror|Terror]] of the French Revolution. Though the relationship ended badly, due in part to the discovery of Imlay's infidelity, and not least because Imlay abandoned her for good, Wollstonecraft's belief in free love survived. She later developed a relationship with the anarchist [[William Godwin]], who shared her free love ideals, and published on the subject throughout his life. However, the two did decide to marry, just months before her death from complications in [[childbirth|parturition]]. |

|||

In recent years, women have created works of art to help keep the free love movement alive, often in ways that even the artist does not realize. [[Sara Bareilles]]’ songs, "Fairytale" and "Love Song" are modern examples of how women are participating in the Free Love movement; although, artists such as Bareilles do not write their songs specifically for the Free Love movement.<ref>Bareilles, Sara. "Sara Bareilles". Sara Bareilles . 20 November 2009 <http://www.sarabmusic.com/site.html?section=music>.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Visions of the Daughters of Albion copy G plate 01.jpg|thumb|right|upright=0.8|Frontispiece to [[William Blake]]'s ''[[Visions of the Daughters of Albion]]'' (1793), which contains Blake's critique of Christian values of marriage. Oothoon (centre) and Bromion (left) are chained together, as Bromion has raped Oothoon and she now carries his baby. Theotormon (right) and Oothoon are in love, but Theotormon is unable to act, considering her polluted, and ties himself into knots of indecision.]] |

|||

The famous feminist [[Gloria Steinem]] at one point stated, “you became a semi-nonperson when you got married.” She also famously coined the expression 'A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle.' Steinem dismissed marriage in 1987 as not having a 'good name.' Steinem got married in 2000, stating that the symbols that feminists once "rebelled against" now are freely chosen, or society had changed.<ref>Frey, Jennifer Gender Equity: A Woman Needs a Man like a Fish Needs a Bicycle. Signs of the Times, 7 09. 2000. Web. 21 Nov 2009 <http://george.loper.org/trends/2000/Sep/91.html>.</ref> |

|||

A member of Wollstonecraft's circle of notable radical intellectuals in England was the [[Romanticism|Romantic]] poet [[William Blake]], who explicitly compared the sexual oppression of marriage to [[slavery]] in works such as ''[[Visions of the Daughters of Albion]]'' (1793), published five years after Wollstonecraft's ''Mary''. Blake was critical of the marriage laws of his day, and generally railed against traditional Christian notions of [[chastity]] as a virtue.<ref>{{cite web |title=Poetry Foundation's bio of William Blake |url=http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/william-blake |access-date=17 July 2014 |url-status=live |archive-date=18 July 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140718164236/http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/william-blake}}</ref> At a time of tremendous strain in his marriage, in part due to Catherine's apparent inability to bear children, he directly advocated bringing a second wife into the house.<ref>{{cite book |last=Hamblen |first=Emily |title=On the Minor Prophecies of William Blake |year=1995 |publisher=Kessinger Publishing |page=10}}{{cite book |last=Berger |first=Pierre |title=William Blake: Poet and Mystic |publisher=E.P. Dutton & Company |year=1915 |page=45}}</ref> His poetry suggests that external demands for marital fidelity reduce love to mere duty rather than authentic affection, and decries jealousy and egotism as a motive for marriage laws. Poems such as "Why should I be bound to thee, O my lovely Myrtle-tree?" and "Earth's Answer" seem to advocate multiple sexual partners. In his poem "[[London (William Blake poem)|London]]" he speaks of "the Marriage-Hearse" plagued by "the youthful Harlot's curse", the result alternately of false Prudence and/or Harlotry. ''[[Visions of the Daughters of Albion]]'' is widely (though not universally) read as a tribute to free love since the relationship between Bromion and Oothoon is held together only by laws and not by love. For Blake, law and love are opposed, and he castigates the "frozen marriage-bed". In ''Visions'', Blake writes: |

|||

==History of free love movements== |

|||

{{poemquote| |

|||

===Historical precedents=== |

|||

Till she who burns with youth, and knows no fixed lot, is bound |

|||

A number of utopian social movements throughout history have shared a vision of free love. The all-male [[Essenes]], who lived in the Middle East from the 1st century BC to the 1st century AD apparently shunned sex, marriage, and slavery.<ref>See [[Essenes#Contemporary ancient sources]]</ref> They also renounced wealth, lived communally, and were pacifist<ref>Although they appear to have been involved in a revolt against the Roman occupiers</ref> vegetarians. An early Christian sect known as the [[Adamites]]—which flourished in North Africa in the 2nd, 3rd and 4th centuries—also rejected marriage. They practised [[nudism]] while engaging in worship and considered themselves free of [[original sin]]. |

|||

In spells of law to one she loathes? and must she drag the chain |

|||

Of life in weary lust? (5.21-3, E49) |

|||

In the 6th century, adherents of [[Mazdakism]] in pre-Muslim [[Persia]] apparently supported a kind of free love in the place of marriage,<ref>Crone, Patricia, ''Kavad's Heresy and Mazdak's Revolt'', in: Iran 29 (1991), S. 21–40</ref> and like many other free-love movements{{Citation needed|date=July 2008}}, also favored vegetarianism, [[pacificism]], and [[communalism]]. Some writers have posited a conceptual link between the rejection of [[private property]] and the rejection of marriage as a form of ownership{{Citation needed|date=July 2008}}. One folk story from the period that contains a mention of a free-love (and nudist) community under the sea is "The Tale of Abdullah the Fisherman and Abdullah the Merman" from ''[[The Book of One Thousand and One Nights]]'' (c. 8th century).<ref>Irwin, Robert, ''Political Thought in The Thousand and One Nights'', in: Marvels & Tales – Volume 18, Number 2, 2004, pp. 246–257. Wayne State University Press</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

[[Karl Kautsky]], writing in 1895, noted that a number of "communistic" movements throughout the Middle Ages also rejected marriage.<ref>[[Karl Kautsky|Kautsky, Karl]] (1895), ''Die Vorläufer des neuen Sozialismus, vol. I: Kommunistische Bewegungen in Mittelalter'', Stuttgart: J.W. Dietz.</ref> Typical of such movements, the [[Cathar]]s of 10th to 14th century Western Europe freed followers from all moral prohibition and religious obligation, but respected those who lived simply, avoided the taking of human or animal life, and were celibate. Women had an uncommon equality and autonomy, even as religious leaders. The Cathars and similar groups (the [[Waldenses]], Apostle brothers, [[Beghards]] and [[Beguines]], [[Lollards]], and [[Hussites]]) were branded as [[heresy|heretics]] by the Roman Catholic Church and suppressed. Other movements shared their critique of marriage but advocated free sexual relations rather than celibacy, such as the [[Brethren of the Free Spirit]], [[Taborite]]s, and [[Picards]].{{clr}} |

|||

[[File:Visions of the Daughters of Albion copy G plate 01.jpg|thumb|right|237px|upright|Frontispiece to [[William Blake]]'s ''[[Visions of the Daughters of Albion]]'' (1793), which contains Blake's critique of Judeo-Christian values of marriage. Oothoon (centre) and Bromion (left), are chained together, as Bromion has raped Oothoon and she now carries his baby. Theotormon (right) and Oothoon are in love, but Theotormon is unable to act, considering her polluted, and ties himself into knots of indecision.]] |

|||

===Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe=== |

|||

In 1789, radical [[Swedenborgianism|Swedenborgian]]s [[August Nordenskjöld]] and C.B. Wadström published the ''Plan for a Free Community'',<ref>''Plan for a Free Community upon the Coast of Africa under the Protection of Great Britain; but Intirely Independent of All European Laws and Governments.'' London: R. Hindmarsh, 1789.</ref> in which they proposed the establishment of a society of sexual liberty, where slavery was abolished and the "[[White (people)|European]]" and the "[[Negro]]" lived together in harmony. In the treatise, marriage is criticised as a form of political repression. The challenges to traditional morality and religion brought by the [[Age of Enlightenment]] and the emancipatory politics of the [[French Revolution]] created an environment where such ideas could flourish. Though at first an ardent, even dogmatic supporter of such liberating aspects of the Revolution, in his policies as Emperor Napoleon later repudiated them, a move typical of revolutionaries who come to power. A group of radical intellectuals in England (sometimes known as the English [[Jacobin (politics)|Jacobins]]) supported the [[French Revolution]], [[abolitionism]], feminism, and free love. Among them was [[William Blake]], who explicitly compares the sexual oppression of marriage to [[slavery]] in works such as ''Visions of the Daughters of Albion'' (1793). |

|||

Blake believed that humans were "fallen", and that a major impediment to a free love society was corrupt human nature, not merely the intolerance of society and the jealousy of men, but the inauthentic hypocritical nature of human communication.<ref>S. Foster Damon ''William Blake: His Philosophy and Symbols'' (1924), p. 105.</ref> He also seems to have thought that marriage should afford the joy of love, but that in reality it often does not,<ref>Wright, Thomas (2003). ''Life of William Blake''. p. 57.</ref> as a couple's knowledge of being chained often diminishes their joy: |

|||

Another member of the circle was pioneering English feminist [[Mary Wollstonecraft]]. Wollstonecraft felt that women should not give up freedom and control of their sexuality, and thus didn't marry her partner, [[Gilbert Imlay]], despite the two conceiving and having a child together in the midst of the [[Reign of Terror|Terror]] of the French Revolution. Though the relationship ended badly, due in part to the discovery of Imlay's infidelity, and not least because Imlay abandoned her for good, Wollstonecraft's belief in free love survived. She developed a relationship with early English anarchist [[William Godwin]], who shared her free love ideals, and published on the subject throughout his life. However, the two did decide to marry, just days before her death due to complications at [[parturition]]. In an act understood to support free love, their child, [[Mary Shelley|Mary]], took up with the then still-married English romantic poet [[Percy Bysshe Shelley]] at a young age. Percy also wrote in defence of free love (and vegetarianism) in the prose notes of ''[[Queen Mab]]'' (1813), in his essay ''On Love'' (c1815) and in the poem ''[[Epipsychidion]]'' (1821): |

|||

{{poemquote|I never was attached to that great sect, |

|||

Whose doctrine is, that each one should select |

Whose doctrine is, that each one should select |

||

Out of the crowd a mistress or a friend, |

Out of the crowd a mistress or a friend, |

||

And all the rest, though fair and wise, commend |

And all the rest, though fair and wise, commend |

||

To cold oblivion... |

To cold oblivion ... |

||

True love has this, different from gold and clay, |

True love has this, different from gold and clay, |

||

That to divide is not to take away. |

That to divide is not to take away.}} |

||

</poem> |

|||

In an act understood to support free love, the child of Wollstonecraft and Godwin, [[Mary Shelley|Mary]], took up with the then still-married English romantic poet [[Percy Bysshe Shelley]] in 1814 at the young age of sixteen. Shelley wrote in defence of free love in the prose notes of ''[[Queen Mab]]'' (1813), in his essay ''On Love'' ({{Circa|1815}}), and in the poem ''[[Epipsychidion]]'' (1821). |

|||

Sharing the free-love ideals of the earlier social movements—as well as their feminism, pacifism, and simple communal life—were the [[utopian socialist]] communities of early-nineteenth-century France and Britain, associated with writers and thinkers such as [[Claude Henri de Rouvroy, Comte de Saint-Simon|Henri de Saint-Simon]] and [[Charles Fourier]] in France, [[Robert Owen]] in England, and, perhaps most far-reaching, the German composer [[Richard Wagner]]. Fourier, who coined the term ''feminism,'' argued that true freedom could only occur without masters, without the ethos of work, and without suppressing passions: the suppression of passions is not only destructive to the individual, but to society as a whole. He argued that all sexual expressions should be enjoyed as long as people are not abused, and that "affirming one's difference" can actually enhance social integration. The Saint-Simonian feminist [[Pauline Roland]] took a free-love stance against marriage, having four children in the 1830s, all of whom bore her name. Wagner's position seems quite similar; he not only advocated something like free love in several of his works, he practiced what he preached, and began a family with [[Cosima Liszt]], then still married to the conductor [[Hans von Bülow]]. Cosima had been one of three children born out of wedlock to the ultra-popular Hungarian composer and pianist [[Franz Liszt|Ferenc (Franz) Liszt]] by Countess [[Marie d'Agoult]]. Though apparently scandalous at the time, such liaisons seemed the actions of admired artists who were following the dictates of their own wills, rather than those of social convention, and in this way they were in step with their era's liberal philosophers of the cult of passion, such as Fourier, and their actual or eventual openness can be understood to be a prelude to the freer ways of the twentieth century. [[Friedrich Nietzsche]] spoke occasionally in favor of something like free love, but when he proposed marriage to that famous practitioner of it, [[Lou Andreas-Salome]], she berated him for being inconsistent with his philosophy of the free and supramoral Superman, a criticism that Nietzsche seems to have taken seriously, or to have at least been stung by. The relationship between composer [[Frédéric Chopin]] and writer [[George Sand]] can be understood as exemplifying free love in a number of ways. Behavior of this kind by figures in the public eye did much to erode the credibility of conventionalism in relationships, especially when such conventionalism brought actual unhappiness to its practitioners. |

|||

===Utopian socialism=== |

|||

That European outpost, Australia, which began its existence as a penal colony, had a much more flexible view of cohabitation and sexual bonding than was known in Europe itself at the time, "Neither the male nor the female convicts thought it was disgraceful, or even wrong, to live together out of wedlock."<ref>Robert Hughes, "The Fatal Shore, The Epic History of Australia's Founding," page 258. (New York, 1986, ISBN 0-394-75366-6.</ref> |

|||

Sharing the free-love ideals of the earlier social movements—as well as their feminism, pacifism, and simple communal life—were the [[utopian socialist]] communities of early-nineteenth-century France and Britain, associated with writers and thinkers such as [[Claude Henri de Rouvroy, Comte de Saint-Simon|Henri de Saint-Simon]] and [[Charles Fourier]] in France, and [[Robert Owen]] in England. Fourier, who coined the term ''feminism,'' argued for true freedom, without suppressing passions: the suppression of passions is not only destructive to the individual, but to society as a whole.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Goldstein |first=Leslie F. |date=1982 |title=Early Feminist Themes in French Utopian Socialism: The St.-Simonians and Fourier |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2709162 |journal=Journal of the History of Ideas |volume=43 |issue=1 |pages=91–108 |doi=10.2307/2709162 |jstor=2709162 |access-date=9 March 2022 }}</ref> He argued that all sexual expressions should be enjoyed as long as people are not abused, and that "affirming one's difference" can actually enhance social integration.<ref>{{cite book |last=Fourier |first=Charles |title=Le Nouveau Monde amoureux |publisher=Éditions Anthropos |year=1967 |place=Paris |pages=389, 391, 429, 458–459, 462–463}} Written 1816–18, not published widely until 1967.</ref> |

|||

===Nineteenth-century United States=== |

|||

Christian socialist writer [[John Humphrey Noyes]] has been credited with coining the term ''free love'' in the mid-nineteenth century, although he preferred to use the term '[[Group marriage|complex marriage]]'. Noyes founded the [[Oneida Society]] in 1848, a utopian community that "[rejected] conventional marriage both as a form of legalism from which Christians should be free and as a selfish institution in which men exerted rights of ownership over women". He found scriptural justification: "In the resurrection they neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are like the angels in heaven" (Matt. 22:30).<ref>William Blake before him had made the same connection: "In Eternity they neither marry nor are given in marriage." ([[Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion]], 30.15; E176)</ref> Noyes also supported [[eugenics]]; and only certain people were allowed to become parents. Another movement was established in [[Berlin Heights, Ohio]]. |

|||

===Origins of the movement=== |

|||

Free love advocates sometimes traced their roots back to [[Josiah Warren]] and to experimental communities, viewed sexual freedom as a clear, direct expression of an individual's self-ownership. Free love particularly stressed [[women's rights]] since most sexual laws discriminated against women: for example, marriage laws and anti-birth control measures.<ref name="freelove">[http://www.ncc-1776.org/tle1996/le961210.html The Free Love Movement and Radical Individualism By Wendy McElroy]</ref> The most important American free love journal was ''[[Lucifer the Lightbearer]]'' (1883–1907) edited by [[Moses Harman]] and [[Lois Waisbrooker]]<ref>Joanne E. Passet, "Power through Print: Lois Waisbrooker and Grassroots Feminism," in: ''Women in Print: Essays on the Print Culture of American Women from the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries'', James Philip Danky and Wayne A. Wiegand, eds., Madison, WI, University of Wisconsin Press, 2006; pp. 229–50.</ref> but also there existed [[Ezra Heywood]] and Angela Heywood's ''[[The Word (free love)|The Word]]'' (1872–1890, 1892–1893).<ref name="freelove"/> Also [[M. E. Lazarus]] was an important American individualist anarchist who promoted free love.<ref name="freelove"/> |

|||

The eminent sociologist [[Herbert Spencer]] argued in his ''Principles of Sociology'' for the implementation of free divorce. Claiming that marriage consists of two components, "union by law" and "union by affection", he argued that with the loss of the latter union, legal union should lose all meaning and dissolve automatically, without the legal requirement for a divorce.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RmpMZ7K2L3YC|title="A Revolution in Christian Morals": Lambeth 1930–Resolution #15. History & Reception|author=Theresa Notare|year=2008|pages=78–79|isbn=978-0549956099|access-date=18 March 2016|archive-date=14 June 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160614061356/https://books.google.com/books?id=RmpMZ7K2L3YC|url-status=live}}</ref> Free love particularly stressed [[women's rights]] since most sexual laws discriminated against women: for example, marriage laws and anti-birth control measures.<ref name="freelove">{{cite web |url=http://www.ncc-1776.org/tle1996/le961210.html |title=The Free Love Movement and Radical Individualism By Wendy McElroy |access-date=2 November 2009 |archive-date=14 June 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110614215038/http://www.ncc-1776.org/tle1996/le961210.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

====United States==== |

|||

Elements of the free-love movement also had links to [[Abolitionism|abolitionist]] movements, drawing parallels between slavery and "[[sexual slavery]]" (marriage), and forming alliances with black activists. They also had many opponents, and Moses Harman spent two years in jail after a court determined that a journal he published was "obscene" under the notorious [[Comstock Law]]. In particular, the court objected to three letters to the editor, one of which described the plight of a woman who had been raped by her husband, tearing stitches from a recent operation after a difficult childbirth and causing severe hemorrhaging. The letter lamented the woman's lack of [[legal recourse]]. [[Ezra Heywood]], who had already been prosecuted under the Comstock Law for a pamphlet attacking marriage, reprinted the letter in solidarity with Harman and was also arrested and sentenced to two years in prison. |

|||

[[File:OneidaCommunityHomeBld.JPG|thumb|The [[Oneida Community]] was a utopian group established in the 1840s, which practiced a form of free love. Postcard of the [[Oneida Community Mansion House]] from 1907.]] |

|||

{{anchor|Free Love Movement in Victorian America}} |

|||

''Free love'' began to coalesce into a movement in the mid- to late 19th century. The term was coined by the Christian socialist writer [[John Humphrey Noyes]], although he preferred to use the term '[[Group marriage|complex marriage]]'. Noyes founded the [[Oneida Community]] in 1848, a utopian community that "[rejected] conventional marriage both as a form of legalism from which Christians should be free and as a selfish institution in which men exerted rights of ownership over women". He found scriptural justification: "In the resurrection they neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are like the angels in heaven" (Matt. 22:30).<ref>William Blake before him had made the same connection: "In Eternity they neither marry nor are given in marriage." ([[Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion]], 30.15; E176)</ref> Noyes also supported [[eugenics]]; and only certain people (including Noyes himself) were allowed to become parents. Another movement was established in [[Berlin Heights, Ohio]]. |

|||

In 1852, a writer named [[M. E. Lazarus|Marx Edgeworth Lazarus]] published a tract entitled "Love vs. Marriage pt. 1", in which he portrayed marriage as "incompatible with social harmony and the root cause of mental and physical impairments." Lazarus intertwined his writings with his religious teachings, a factor that made the Christian community more tolerable to the free love idea.<ref name="Passet, Joanne E 2003"/> Elements of the free-love movement also had links to [[Abolitionism|abolitionist]] movements, drawing parallels between slavery and "[[sexual slavery]]" (marriage), and forming alliances with black activists. |

|||

American feminist [[Victoria Woodhull]] (1838–1927), the first woman to run for presidency in the U.S. in 1872, was also called "the high priestess of free love". In 1871, Woodhull wrote: |

|||

American feminist [[Victoria Woodhull]] (1838–1927), the first woman to run for presidency in the U.S., in 1872, was also called "the high priestess of free love". {{anchor|Free Lover}}In 1871, Woodhull wrote: "Yes, I am a Free Lover. I have an inalienable, constitutional and natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or as short a period as I can; to change that love every day if I please, and with that right neither you nor any law you can frame have any right to interfere".<ref>[http://gos.sbc.edu/enwiki/w/woodhull.html "And the Truth Shall Make You Free"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060106225055/http://gos.sbc.edu/enwiki/w/woodhull.html |date=6 January 2006 }} (20 November 1871)</ref> |

|||

[[File:Victoria Woodhull caricature by Thomas Nast 1872.jpg|thumb|upright|right|Cartoon by [[Thomas Nast]] portraying [[Victoria Woodhull]] as an advocate of free love]] |

|||

The women's movement, free love and [[Spiritualism (religious movement)|Spiritualism]] were three strongly linked movements at the time, and Woodhull was also a spiritualist leader. Like Noyes, she also supported [[eugenics]]. Fellow social reformer and educator Mary Gove Nichols was happily married (to her second husband), and together they published a newspaper and wrote medical books and articles,<ref name="Gove1842">{{cite book |title=Lectures to Ladies on Anatomy and Physiology | volume= |url=http://www.archive.org/stream/lecturestoladies00nichiala#page/n5/mode/2up |last=Gove | first=Mary S. | edition= |year=1842| publisher=Saxton & Peirce | location=Boston | page=|accessdate=13 January 2009}} Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org).</ref><ref name="Gove1846">{{cite book |chapter=Lectures to Women on Anatomy and Physiology |title=with an Appendix on Water Cure |url=http://www.archive.org/stream/lecturestowomen00nichgoog#page/n9/mode/1up |last=Gove Nichols | first=Mary S. | edition= |year=1846| publisher=Harper & Brothers | location=New York | page=|accessdate=13 January 2009}} Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org).</ref><ref name="Gove-Nichols1855">{{cite book |chapter=Experience in the Water Cure: A familiar exposition of the Principles and Results of Water Treatment, in the Cure of Acute and Chronic Diseases| title=in Fowlers and Wells' Water-Cure Library: Embracing all the most popular works on the subject|volume=Vol. 2 of 7 |url=http://www.archive.org/stream/anintroductiont01nichgoog#page/n56/mode/1up | last=Gove Nichols | first=Mary S.| edition= | year=1855 | publisher=Fowlers and Wells | location=New York| page= | accessdate=29 October 2009}} Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org).</ref> a novel, and a treatise on marriage, in which they argued the case for free love. Both Woodhull and Nichols eventually repudiated free love. |

|||

The [[women's suffrage movement]], free love and [[Spiritualism (religious movement)|Spiritualism]] were three strongly linked movements at the time, and Woodhull was also a spiritualist leader. Like Noyes, she also supported [[eugenics]]. Fellow social reformer and educator Mary Gove Nichols was happily married (to her second husband), and together they published a newspaper and wrote medical books and articles.<ref name="Gove1842">{{cite book |last=Gove |first=Mary S. |year=1842 |title=Lectures to Ladies on Anatomy and Physiology |url=https://archive.org/stream/lecturestoladies00nichiala#page/n5/mode/2up |publisher=Saxton & Peirce |location=Boston |access-date=13 January 2009 |via=Internet Archive}}</ref><ref name="Gove1846">{{cite book |chapter=Lectures to Women on Anatomy and Physiology |title=with an Appendix on Water Cure |chapter-url=https://archive.org/stream/lecturestowomen00nichgoog#page/n9/mode/1up |last=Gove Nichols |first=Mary S. |year=1846 |publisher=Harper & Brothers |location=New York |access-date=13 January 2009 |via=Internet Archive}}</ref><ref name="Gove-Nichols1855">{{cite book |chapter=Experience in the Water Cure: A familiar exposition of the Principles and Results of Water Treatment |title=Cure of Acute and Chronic Diseases| series=Fowlers and Wells' Water-Cure Library: Embracing all the most popular works on the subject |volume=2 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/stream/anintroductiont01nichgoog#page/n56/mode/1up |last=Gove Nichols |first=Mary S.| year=1855 |publisher=Fowlers and Wells |location=New York| access-date=29 October 2009 |via=Internet Archive}}</ref> Both Woodhull and Nichols eventually repudiated free love.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gsddNlV-rGwC&pg=PA30 |title=Evolutionary Rhetoric: Sex, Science, and Free Love in Nineteenth-Century ... - Wendy Hayden - Google Books |date=14 February 2013 |isbn=9780809331024 |accessdate=27 August 2022|last1=Hayden |first1=Wendy |publisher=SIU Press }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tVeh3C8XGP4C&pg=PA82 |title=Encyclopedia of Rape - Google Books |isbn=9780313326875 |accessdate=27 August 2022|last1=Smith |first1=Merril D. |year=2004 |publisher=Greenwood Publishing }}</ref> |

|||

Publications of the movement in the second half of the 19th century included Nichols' Monthly, The Social Revolutionist, Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly (ed. Victoria Woodhull and her sister [[Tennessee Clafin]]), [[The Word (free love)|The Word]] (ed. [[Ezra Heywood]]), [[Lucifer, the Light-Bearer]] (ed. [[Moses Harman]]) and the German-language Detroit newspaper Der Arme Teufel (ed. [[Robert Reitzel]]). Organisations included the New England Free Love League, founded with the assistance of American libertarian [[Benjamin Tucker]] as a spin off from the New England Labor Reform League (NELRL). A minority of [[freethought|freethinkers]] also supported free love.<ref>Kirkley, Evelyn A. 2000. ''Rational Mothers and Infidel Gentlemen: Gender and American Atheism, 1865–1915.'' (Women and Gender in North American Religions.) Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. 2000. Pp. xviii, 198</ref> |

|||

Publications of the movement in the second half of the 19th century included Nichols' Monthly, ''The Social Revolutionist'', ''[[Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly]]'' (ed. Victoria Woodhull and her sister [[Tennessee Celeste Claflin|Tennessee Claflin]]), ''[[The Word (US magazine)|The Word]]'' (ed. [[Ezra Heywood]]), ''[[Lucifer, the Light-Bearer]]'' (ed. [[Moses Harman]]) and the German-language Detroit newspaper ''Der Arme Teufel'' (ed. Robert Reitzel). Organisations included the New England Free Love League, founded with the assistance of American libertarian socialist [[Benjamin Tucker]] as a spin-off from the New England Labor Reform League (NELRL). A minority of [[freethought|freethinkers]] also supported free love.<ref>Kirkley, Evelyn A. 2000. ''Rational Mothers and Infidel Gentlemen: Gender and American Atheism, 1865–1915.'' (Women and Gender in North American Religions.) Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. 2000. pp. xviii, 198</ref> |

|||

The most radical free love journal was ''The Social Revolutionist'', published in the 1856–1857, by John Patterson. The first volume consisted of twenty writers, of which only one was a woman.<ref name="Spurlock, John 1994"/> |

|||

The most radical free love journal was ''The Social Revolutionist'', published in 1856–1857 by John Patterson. The first volume consisted of twenty writers, of which only one was a woman.<ref name="Spurlock, John 1994"/> |

|||

In an edition of [[Lucifer, the Light-Bearer]], there is a blurb about women and marriage: |

|||

<blockquote>in order to live the purest life, must be free, must enjoy the full privilege of soliciting the love of any man, or of none, if she so desires. She must be free and independent socially, industrially," – Page 265. This is only one specimen of the many radical and vitally important truths contained in "A CITYLESS AND COUNTRYLESS WORLD," by [[Henry Olerich]]. Bound in red silk, with gold lettering on side and back; nearly 400 pages. Read it and you will see the defects of paternalism as set forth by Bellamy. Price $1. For sale at this office.<ref>Ward, Dana Anarchy Archives. Anarchy Archives, 25 September 2001. Web. 21 November 2009 <http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/anarchist_Archives/coldoffthepresses/luciferv2.html>.</ref></blockquote> This quote demonstrated the journal's fight to get women to see the light of how marriage truly was in the early twentieth century. |

|||

In 1852, a writer named [[Marx Edgeworth Lazarus]] published a tract entitled "Love vs. Marriage pt. 1," in which he portrayed marriage as "incompatible with social harmony and the root cause of mental and physical impairments." Lazarus intertwined his writings with his religious teachings, a factor that made the Christian community more tolerable to the free love idea.<ref name="Passet, Joanne E 2003"/> |

|||

Sex radicals were not alone in their fight against marriage ideals. Some other nineteenth-century Americans saw this social institution as flawed, but hesitated to abolish it. Groups such as the Shakers, the Oneida Community, and the Latter-day Saints were wary of the social notion of marriage. These organizations and sex radicals believed that true equality would never exist between the sexes as long as the church and the state continued to work together, worsening the problem of subordination of wives to their husbands.<ref name="Passet, Joanne E 2003"/> |

Sex radicals were not alone in their fight against marriage ideals. Some other nineteenth-century Americans saw this social institution as flawed, but hesitated to abolish it. Groups such as the Shakers, the Oneida Community, and the Latter-day Saints were wary of the social notion of marriage. These organizations and sex radicals believed that true equality would never exist between the sexes as long as the church and the state continued to work together, worsening the problem of subordination of wives to their husbands.<ref name="Passet, Joanne E 2003"/> |

||

Free-love movements continued into the early 20th century in [[bohemianism|bohemian]] circles in New York's [[Greenwich Village]]. A group of Villagers lived free-love ideals and promoted them in the political journal ''[[The Masses]]'' and its sister publication ''[[The Little Review]],'' a literary journal. Incorporating influences from the writings of the English thinkers and activists [[Edward Carpenter]] and [[Havelock Ellis]], women such as [[Emma Goldman]] campaigned for a range of sexual freedoms, including homosexuality and access to contraception. Other notable figures among the Greenwich-Village scene who have been associated with free love include [[Edna St. Vincent Millay]], [[Max Eastman]], [[Crystal Eastman]], [[Floyd Dell]], [[Mabel Dodge Luhan]], [[Ida Rauh]], [[Hutchins Hapgood]], and [[Neith Boyce]]. [[Dorothy Day]] also wrote passionately in defense of free love, women's rights, and contraception—but later, after converting to Catholicism, she criticized the sexual revolution of the sixties. |

|||

The free love movement evolved through four stages between 1853 and 1910. The first stage was a collective stage, where sex radicals put out print materials. The second stage was when the sex radicals encountered strong opposition; editors risked being arrested for writing about sexual topics. During the third stage, sex radicals challenged the government's power to control women's bodies and their private lives. The fourth and final stage was when the movement started to lose its drive. A new type of women's movement was born, thus making it impossible to keep the free love movement alive.<ref name="Passet, Joanne E 2003"/> |

|||

The development of the idea of free love in the United States was also significantly impacted by the publisher of ''[[Playboy (magazine)|Playboy]]'' magazine, [[Hugh Hefner]], whose activities and persona over more than a half century popularized the idea of free love to some of the general public.{{clear}} |

|||

[[File:Carpenter1875.jpg|thumb|right|150px|[[Edward Carpenter]] in 1875]] |

|||

===Turn of the twentieth century=== |

|||

====United Kingdom==== |

====United Kingdom==== |

||

[[File:Portrait of Havelock Ellis (1859-1939), Psychologist and Biologist (2575987702) crop.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Havelock Ellis]] was a pioneer [[sexology|sexologist]] and advocate of free love.]] |

|||

Toward the end of the nineteenth century in the United Kingdom, free love was a topic of discussion among a minority of freethinkers, socialists, and feminists. Many of them were associated with [[The Fellowship of the New Life]], such as [[Olive Schreiner]] and [[Edward Carpenter]]. Carpenter was one of the first writers to defend homosexuality in the English language. Like many of the movements before them who were associated with free love, the group also favored a simple communal life, [[pacifism]], and vegetarianism. The best-known modern British advocate of free love was the philosopher [[Bertrand Russell]], later Third Earl Russell, who said that he did not believe he really knew a woman until he had made love with her. Russell consistently addressed aspects of free love throughout his voluminous writings, and was not personally content with conventional monogamy until extreme old age. |

|||

Free love was a central tenet of the philosophy of the [[Fellowship of the New Life]], founded in 1883 by the Scottish intellectual [[Thomas Davidson (philosopher)|Thomas Davidson]].<ref>{{cite web|first=James A.|last=Good|url=http://www.autodidactproject.org/other/TD.html|title=The Development of Thomas Davidson's Religious and Social Thought|access-date=17 July 2014|archive-date=12 October 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181012175347/http://www.autodidactproject.org/other/TD.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Fellowship members included many illustrious intellectuals of the day, who went on to radically challenge accepted Victorian notions of morality and sexuality, including poets [[Edward Carpenter]] and [[John Davidson (poet)|John Davidson]], animal rights activist [[Henry Stephens Salt]],<ref>George Hendrick, ''Henry Salt: Humanitarian Reformer and Man of Letters'', University of Illinois Press, p. 47 (1977).</ref> sexologist [[Havelock Ellis]], feminists [[Edith Ellis|Edith Lees]], [[Emmeline Pankhurst]] and [[Annie Besant]] and writers [[H. G. Wells]], [[George Bernard Shaw|Bernard Shaw]], [[Bertrand Russell]] and [[Olive Schreiner]].<ref>[[Jeffrey Weeks (sociologist)|Jeffrey Weeks]], ''Making Sexual History'', Wiley-Blackwell, p. 20 (2000).</ref> Its objective was "The cultivation of a perfect character in each and all," and believed in the transformation of society through setting an example of clean simplified living for others to follow. Many of the Fellowship's members advocated [[pacifism]], [[vegetarianism]] and [[simple living]].<ref>Colin Spencer, ''The Heretic's Feast:A History of Vegetarianism'', Fourth Estate, p. 283 (1996).</ref> |

|||

[[Edward Carpenter]] was an early activist for the rights of [[homosexual]]s.<ref name="WWiH">{{cite encyclopedia |last=Smith |first=Warren Allen |author-link=Warren Allen Smith |title=Carpenter, Edward (1844–1929) |url=https://archive.org/details/whoswhoinhellhan00smit/page/186/mode/2up |url-access=registration |encyclopedia=Who's Who in Hell, A Handbook and International Directory for Humanists, Freethinkers, Naturalists, Rationalists, and Non-Theists |publisher=Barricade Books |publication-place=New York |year=2000 |isbn=978-1-56980-158-1 |oclc=707072872 |page=186 |via=Internet Archive}}</ref> He became interested in progressive education, especially providing information to young people on the topic of sexual education. For Carpenter, sexual education meant forwarding a clear analysis of the ways in which sex and gender were used to oppress women, contained in Carpenter's radical work ''Love's Coming-of-Age''. In it he argued that a just and equal society must promote the sexual and [[economic freedom]] of women. The main crux of his analysis centred on the negative effects of the institution of marriage. He regarded marriage in England as both enforced celibacy and a form of prostitution. |

|||

====Australia==== |

|||

There was also an interest in free love among the late 19th-century Left in Australia. In 1886, the [[Chummy Fleming#Melbourne Anarchist Club|Melbourne Anarchist Club]] led a debate on the topic, and a couple of years later released an anonymous pamphlet on the subject: 'Free Love—Explained and Defended' (possibly written by [[David Andrade]] or [[Chummy Fleming]]). The view of the Anarchist Club was formed in part as a reaction to the infamous [[Whitechapel murders]] by the notorious [[Jack the Ripper]]; his atrocities were at the time popularly understood by some – at least, by anarchists – to be a violation of the freedom of certain extreme classes of "working women," but by extension of all women. |

|||

[[File:Carpenter1875.jpg|thumb|left|upright|[[Edward Carpenter]] in 1875]] |

|||

[[File:Portrait of Havelock Ellis (1859-1939), Psychologist and Biologist (2575987702) crop.jpg|left|thumb|150px|[[Havelock Ellis]]]] |

|||

The best-known British advocate of free love was the philosopher [[Bertrand Russell]], later Third Earl Russell, who said that he did not believe he really knew a woman until he had made love with her. Russell consistently addressed aspects of free love throughout his voluminous writings, and was not personally content with conventional [[monogamy]] until extreme old age. His most famous work on the subject was ''[[Marriage and Morals]]'', published in 1929. The book heavily criticizes the [[Victorian morality|Victorian notions of morality]] regarding sex and marriage. Russell argued that the laws and ideas about sex of his time were a potpourri from various sources, which were no longer valid with the advent of [[contraception]], as the sexual acts are now separated from the conception. He argued that family is most important for the welfare of children, and as such, a man and a woman should be considered bound only after her first pregnancy.<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20090815045823/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,787544,00.html "Sex Seer"], in ''Time'', 4 November 1929</ref> |

|||

[[Newcastle, New South Wales|Newcastle]] libertarian [[Alice Winspear]], the wife of pioneer socialist [[William Robert Winspear]], wrote: "Let us have freedom — freedom for both man and woman—freedom to earn our bread in whatever vocation is best suited to us, and freedom to love where we like, and to live only with those whom we love, and by whom we are loved in return." A couple of decades later, the [[Melbourne]] anarchist feminist poet [[Lesbia Harford]] also championed free love. |

|||

''Marriage and Morals'' prompted vigorous protests and denunciations against Russell shortly after the book's publication.<ref name=SexEdPioneers>{{cite web|title=Pioneers of Sex Education |url=http://www2.hu-berlin.de/sexology/ATLAS_EN/html/pioneers_of_sex_education.html |author=Haeberle, Erwin J. |year=1983 |access-date=17 February 2008 |publisher=The Continuum Publishing Company |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080313020717/http://www2.hu-berlin.de/sexology/ATLAS_EN/html/pioneers_of_sex_education.html |archive-date=13 March 2008 }}</ref> A decade later, the book cost him his professorial appointment at the [[City College of New York]] due to a court judgment that his opinions made him "morally unfit" to teach.<ref name=Denied>{{cite web|title=Appointment Denied: The Inquisition of Bertrand Russell |author=Leberstein, Stephen |url=http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3860/is_200111/ai_n9008065 |publisher=Academe |date=November–December 2001 |access-date=17 February 2008 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081004082928/http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3860/is_200111/ai_n9008065 |archive-date=4 October 2008 }}</ref> Contrary to what many people believed, Russell did not advocate an extreme [[libertine]] position. Instead, he felt that sex, although a natural impulse like hunger or thirst, involves more than that, because no one is "satisfied by the bare sexual act". He argued that abstinence enhances the pleasure of sex, which is better when it "has a large psychical element than when it is purely physical".<ref name="Hauerwas">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fEKu6SoJR6cC|title=After Christendom?: How the Church Is to Behave If Freedom, Justice, and a Christian Nation Are Bad Ideas|author=Stanley Hauerwas|year=2011|publisher=Abingdon Press|isbn=978-1426722011|access-date=18 March 2016|archive-date=14 June 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160614044823/https://books.google.com/books?id=fEKu6SoJR6cC|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

====United States==== |

|||

Anarchist free-love movements continued into early 20th century in [[bohemianism|bohemian]] circles in New York's [[Greenwich Village]]. A group of Villagers lived free-love ideals and promoted them in the political journal ''[[The Masses]]'' and its sister publication ''[[The Little Review]],'' a literary journal. Incorporating influences from the writings of English homosexual socialist [[Edward Carpenter]] and international sexologist [[Havelock Ellis]], women such as [[Emma Goldman]] campaigned for a range of sexual freedoms, including homosexuality and access to contraception. Other notable figures among the Greenwich-Village scene who have been associated with free love include [[Edna St. Vincent Millay]], [[Max Eastman]], [[Crystal Eastman]], [[Floyd Dell]], [[Mabel Dodge Luhan]], [[Ida Rauh]], [[Hutchins Hapgood]], [[Neith Boyce]]; a certain extreme was reached by self-proclaimed Satanist [[Anton LaVey]]. [[Dorothy Day]] also wrote passionately in defense of free love, women's rights, and contraception – but later, after converting to Catholicism, she criticized the sexual revolution of the sixties. |

|||

Russell noted that for a marriage to work requires that there "be a feeling of complete equality on both sides; there must be no interference with mutual freedom; there must be the most complete physical and mental intimacy; and there must be a certain similarity in regard to standards of value". He argued that it was, in general, impossible to sustain this mutual feeling for an indefinite length of time, and that the only option in such a case was to provide for either the easy availability of [[divorce]], or the social sanction of extra-marital sex.<ref name="Hauerwas"/> |

|||

The development of the idea of free love in the United States was also significantly impacted by the publisher of ''[[Playboy (magazine)|Playboy]]'' magazine, [[Hugh Hefner]], whose activities and persona over more than a half century popularized the idea of free love to the general public.{{clr}} |

|||

Russell's view on marriage changed as he went through personal struggles of subsequent marriages; in his autobiography he writes, "I do not know what I think now about the subject of marriage. There seem to be insuperable objections to every general theory about it. Perhaps easy divorce causes less unhappiness than any other system, but I am no longer capable of being dogmatic on the subject of marriage."<ref>{{Cite book|last=Russell|first=Bertrand|year=2014|title=The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell|page=391|doi=10.4324/9781315824499|isbn=978-1315824499}}</ref> |

|||

====Japan==== |

|||

The anarchist feminist, social critic, novelist, and [[Emma Goldman]] translator [[Noe Ito]] (1895–1923) and her lover, fellow anarchist [[Sakae Osugi]] (1885–1923), promoted free love in Japan.{{Citation needed|date=October 2012}} The entire nation was shocked by their extrajudicial execution by a squad of [[military police]] in what became known as the [[Amakasu Incident]], after the name of its perpetrator, who was imprisoned for his crime. Their story is told in the 1969 movie ''Erosu purasu Gyakusatsu'' ([[Eros Plus Massacre]]). |

|||

Russell was also a very early advocate of repealing [[sodomy laws]].<ref>{{cite news|work=The Times|title=Homosexual Acts, Call To Reform Law|date=7 March 1958|page=11}}</ref> |

|||

====USSR==== |

|||

After the [[October Revolution]] in Russia, [[Alexandra Kollontai]] became the most prominent woman in the Soviet administration. Kollontai was also a champion of free love. [[Clara Zetkin]] recorded that Lenin opposed free love as "completely un-Marxist, and moreover, anti-social".<ref>Zetkin, Clara, 1934, ''Lenin on the Woman Question,'' New York: International , p.7. Published in ''Reminiscences of Lenin.''<br>A more extensive quote from Lenin follows: "It seems to me that this superabundance of sex theories [...] springs from the desire to justify one's own abnormal or excessive sex life before bourgeois morality and to plead for tolerance towards oneself. This veiled respect for bourgeois morality is as repugnant to me as rooting about in all that bears on sex. No matter how rebellious and revolutionary it may be made to appear, it is in the final analysis thoroughly bourgeois. It is, mainly, a hobby of the intellectuals and of the sections nearest to them. There is no place for it in the party, in the class-conscious, fighting proletariat.”</ref> Zetkin also recounted Lenin's denunciation of plans to organise Hamburg's women prostitutes into a “special revolutionary militant section”: he saw this as “corrupt and degenerate.” |

|||

Despite the traditional marital lives of Lenin and most Bolsheviks, they believed that sexual relations were outside the jurisdiction of the state. The Soviet government abolished centuries-old Czarist regulations on personal life, which had prohibited homosexuality and made it difficult for women to obtain divorce permits or to live singly. However, by the end of the 1920s, [[Joseph Stalin|Stalin]] had taken over the Communist Party and begun to implement socially conservative policies. Homosexuality was classified as a mental disorder, and free love was further demonized. |

|||

====France==== |

====France==== |

||

[[File:Emilearmand01.jpg| |

[[File:Emilearmand01.jpg|right|thumb|upright|[[Émile Armand]]]] |

||

An important propagandist of free love was [[individualist anarchist]] [[Émile Armand]]. He advocated [[naturism]] and [[polyamory]] in what he termed ''la camaraderie amoureuse''.<ref name="armand">[http://www.iisg.nl/womhist/manfreuk.pdf "Emile Armand and la camaraderie amourouse – Revolutionary sexualism and the struggle against jealousy." by Francis Rousin] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110514110104/http://www.iisg.nl/womhist/manfreuk.pdf |date=14 May 2011 }} Retrieved 10 June 2010</ref> He wrote many propagandist articles on this subject such as "De la liberté sexuelle" (1907) where he advocated not only a vague free love but also multiple partners, which he called "plural love".<ref name="armand"/> In the individualist anarchist journal ''L'en dehors'' he and others continued in this way. Armand seized this opportunity to outline his theses supporting revolutionary sexualism and camaraderie amoureuse that differed from the traditional views of the partisans of free love in several respects. |

|||

In the bohemian districts of [[Montmartre]] and [[Montparnasse]], many were determined to shock the "[[bourgeois]]" sensibilities of the society they grew up in; many, such as the anarchist [[Benoît Broutchoux]], favored free love. At the same time, the [[cross-dressing]] radical activist [[Madeleine Pelletier]] practised celibacy, distributed birth-control devices and information, and performed abortions. |

|||