Female genital mutilation: Difference between revisions

→Overview: rewording: "Uncircumcised women are seen as highly sexualized; philosopher Martha Nussbaum argues that the practice presupposes women to be 'whorish and childish'" to be a WP:ITA, since she is only one source for the former part |

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Altered pages. Formatted dashes. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | #UCB_CommandLine |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Ritual cutting or removal of some or all of the vulva}} |

|||

{{redirect|FGM}} |

|||

{{ |

{{Redirect|FGM}} |

||

{{Distinguish|Vaginoplasty|Labiaplasty|Labia stretching|Vulvoplasty}} |

|||

{{pp-semi-indef}}{{use dmy dates|date=December 2012}} |

|||

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

|||

{{infobox |

|||

{{featured article}} |

|||

|image1 = [[File:Campaign road sign against female genital mutilation (cropped).jpg|270px|alt=photograph]] |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=August 2018}} |

|||

|caption1 = Road sign near [[Kapchorwa]], [[Uganda]], where FGM is outlawed but still practised by the [[Pokot people|Pokot]], [[Sebei people|Sabiny]] and Tepeth people.<ref>Masinde, Andrew. [http://www.newvision.co.ug/news/639566-fgm-despite-the-ban-the-monster-still-rears-its-ugly-head-in-uganda.html "FGM: Despite the ban, the monster still rears its ugly head in Uganda"], ''New Vision'', Uganda, 5 February 2013.</ref> |

|||

{{Infobox |

|||

|headerstyle = background-color: |

|||

|image1 = [[File:Campaign road sign against female genital mutilation (cropped) 2.jpg|300px|alt=Billboard with surgical tools covered by a red X. Sign reads: STOP FEMALE CIRCUMCISION. IT IS DANGEROUS TO WOMEN'S HEALTH. FAMILY PLANNING ASSOCIATION OF UGANDA]] |

|||

|title = Female genital mutilation |

|||

|caption1 = Anti-FGM road sign near [[Kapchorwa]], Uganda, 2004 |

|||

|titlestyle = background-color:#99BADD;<!--color:white;--> |

|||

|label2 = Definition |

|||

|labelstyle = width: |

|||

|data2 = "Partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons" ([[World Health Organization|WHO]], [[UNICEF]], and [[United Nations Population Fund|UNFPA]], 1997).<ref name=WHO2014>[[#WHO2014|WHO 2014]].</ref> |

|||

|datastyle = |

|||

| |

|label3 = Areas |

||

|data3 = Africa, Southeast Asia, Middle East, and within communities from these areas<ref>[[#UNICEF2013|UNICEF 2013]], 5.</ref> |

|||

|data2 = Partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons<ref name=WHO1/> |

|||

|label3 = Areas practised |

|||

|data3 = Most common in 27 countries in [[Sub-Saharan Africa|sub-Saharan]] and [[Northeast Africa|north-east Africa]], as well as in [[Yemen]] and [[Iraqi Kurdistan]]<ref name=UNICEF2013p2>[http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf "Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A Statistical Overview and Exploration of the Dynamics of Change"], United Nations Children's Fund, July 2013 (hereafter UNICEF 2013), p. 2.</ref> |

|||

|label4 = Numbers |

|label4 = Numbers |

||

|data4 = Over 230 million women and girls worldwide: 144 million in Africa, 80 million in Asia, 6 million in Middle East, and 1-2 million in other parts of the world (as of 2024)<ref name=UNICEF2023>{{cite web|url=https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/female-genital-mutilation/ |title=Female genital mutilation (FGM)|work=[[UNICEF]]|access-date=July 5, 2023}}</ref><ref name=UNICEF2016>[[#UNICEF2016|UNICEF 2016]].</ref> |

|||

|data4 = 125 million in those countries<ref name=UNICEF2013p22/> |

|||

|label5 = Age |

|label5 = Age |

||

|data5 = |

|data5 = Days after birth to puberty<ref name="UNICEF2013p50"/> |

||

|label6 = Prevalence |

|||

|data6 = {{collapsed infobox section begin|Ages 15–49}} |

|||

|label6 = |

|||

| |

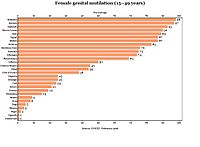

|data7 = {{hlist|[[Somalia]] (98%)| [[Guinea]] (97%)| [[Djibouti]] (93%)| [[Sierra Leone]] (90%)| [[Mali]] (89%)| [[Egypt]] (87%)| [[Sudan]] (87%)| [[Eritrea]] (83%)| [[Burkina Faso]] (76%)|[[Gambia]] (75%)| [[Ethiopia]] (74%)| [[Mauritania]] (69%)| [[Liberia]] (50%)| [[Guinea-Bissau]] (45%)|[[Chad]] (44%)| [[Côte d'Ivoire]] (38%)| [[Nigeria]] (25%)| [[Senegal]] (25%)| [[Central African Republic]] (24%)| [[Kenya]] (21%)|[[Yemen]] (19%)| [[United Republic of Tanzania]] (10%)| [[Benin]] (9%)| |

||

[[Iraq]] (8%)| [[Togo]] (5%)| [[Ghana]] (4%)| [[Niger]] (2%)| [[Uganda]] (1%) | [[Cameroon]] (1%)<ref name=UNICEF2016/>}} |

|||

{{collapsed infobox section end}} |

{{collapsed infobox section end}} |

||

{{collapsed infobox section begin| |

{{collapsed infobox section begin|Ages 0–14}} |

||

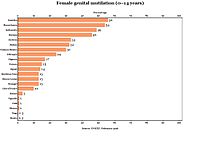

|data8 = {{hlist|[[Gambia]] (56%)| [[Mauritania]] (54%)| [[Indonesia]] (49%, 0–11) | [[Guinea]] (46%) |[[Eritrea]] (33%)| [[Sudan]] (32%) | [[Guinea-Bissau]] (30%)| [[Ethiopia]] (24%) | [[Nigeria]] (17%)|[[Yemen]] (15%)| [[Egypt]] (14%)| [[Burkina Faso]] (13%)| [[Sierra Leone]] (13%)| [[Senegal]] (13%)| [[Côte d'Ivoire]] (10%)| [[Kenya]] (3%)| [[Uganda]] (1%)| [[Central African Republic]] (1%)| [[Ghana]] (1%)| [[Togo]] (0.3%) | [[Benin]] (0.2%)<ref name=UNICEF2016/>}} |

|||

|label7 = |

|||

|data7 = FGM is outlawed in the following practising countries, as of 2013: Benin (2003), Burkina Faso (1996), Central African Republic (1966, amended 1996), Chad (2003), Côte d’Ivoire (1998), Djibouti (1995, amended 2009), Egypt (2008), Eritrea (2007), Ethiopia (2004), Ghana (1965, amended 2007), Guinea (1965, amended 2000), Guinea-Bissau (2011), Iraqi Kurdistan (2011), Kenya (2001, amended 2011), Mauritania (2005), Niger (2003), Nigeria, some states (1999–2006), Senegal (1999), Somalia (2012), Sudan, some states (2008–2009), Togo (1998), Uganda (2010), United Republic of Tanzania (1998), and Yemen (2001).<ref>[http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], p. 9.</ref><p>It is also outlawed in 33 countries outside Africa and the Middle East,<ref name=UNICEF2013p8/> including across the European Union, North America, Scandinavia, Australia and New Zealand. |

|||

{{collapsed infobox section end}} |

{{collapsed infobox section end}} |

||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Sex and the law}} |

|||

'''Female genital mutilation''' ('''FGM'''), also known as '''female genital cutting''' and '''female circumcision''', is defined by the [[World Health Organization]] (WHO) as "all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons."<ref name=WHO1>[http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/overview/en/index.html "Classification of female genital mutilation"], World Health Organization, 2013 (hereafter WHO 2013).</ref> FGM is practised as a cultural ritual by [[Ethnic groups in Africa|ethnic groups]] in 27 countries in [[sub-Saharan Africa|sub-Saharan]] and [[Northeast Africa]], and to a lesser extent in Asia, the Middle East and within immigrant communities elsewhere.<ref name=where/> It is typically carried out, with or without anaesthesia, by a traditional circumciser using a knife or razor.<ref>[http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], p. 43, p. 44, footnote: "In the majority of countries, FGM/C is usually performed by traditional practitioners and, more specifically, by traditional circumcisers. ... 'Traditional practitioners' include traditional circumcisers, traditional birth attendants, traditional midwives and other types of traditional practitioners. In Egypt, traditional practitioners also include ''dayas'', ''ghagarias'' and ''barbers''." |

|||

*[http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], p. 45: "In most cases, a blade or razor was used for cutting in Egypt, and one in four daughters underwent the procedure without an anaesthetic of any kind. It is plausible to expect this proportion to be much higher in countries where the practice is mostly performed by traditional circumcisers rather than medical personnel."</ref> The age of the girls varies from weeks after birth to puberty; in half the countries for which figures were available in 2013, most girls were cut before the age of five.<ref name=UNICEF2013p50>[http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], p. 50.</ref> |

|||

'''Female genital mutilation''' ('''FGM''') (also known as '''female genital cutting''', '''female genital mutilation/cutting''' ('''FGM/C''') and '''female circumcision'''{{efn|[[Martha Nussbaum]] (''Sex and Social Justice'', 1999): "Although discussions sometimes use the terms 'female circumcision' and 'clitoridectomy', 'female genital mutilation' (FGM) is the standard generic term for all these procedures in the medical literature ... The term 'female circumcision' has been rejected by international medical practitioners because it suggests the fallacious analogy to male circumcision ..."{{sfn|Nussbaum|1999|loc=119}}}}) is the cutting or removal of some or all of the [[vulva]] for non-medical reasons. [[Prevalence of female genital mutilation|FGM prevalence]] varies worldwide, but is majorly present in some countries of Africa, Asia and Middle East, and within their diasporas. {{As of|2024}}, [[UNICEF]] estimates that worldwide 230 million girls and women (144 million in Africa, 80 million in Asia, 6 million in Middle East, and 1-2 million in other parts of the world) had been subjected to [[Female genital mutilation#Types|one or more types]] of FGM.<ref name=UNICEF2023/> |

|||

The practice involves one or more of several procedures, which vary according to the ethnic group. They include removal of all or part of the [[clitoris]] and [[clitoral hood]]; all or part of the clitoris and [[inner labia]]; and in its most severe form ([[infibulation]]) all or part of the inner and [[labia majora|outer labia]] and the closure of the vagina. In this last procedure, which the WHO calls [[#WHO Type III|Type III]] FGM, a small hole is left for the passage of urine and menstrual blood, and the vagina is opened up for intercourse and childbirth.<ref name=TypeIIIdef/> The health effects depend on the procedure but can include recurrent infections, chronic pain, cysts, an inability to get pregnant, complications during childbirth and fatal bleeding.<ref name=Abdulcadira>Abdulcadira, Jasmine; Margairaz, C.; Boulvain, M; Irion, O. [http://www.smw.ch/content/smw-2011-13137/ "Care of women with female genital mutilation/cutting"], ''Swiss Medical Weekly'', 6(14), January 2011 (review).</ref> |

|||

Typically carried out by a traditional cutter using a blade, FGM is conducted from days after birth to puberty and beyond. In half of the countries for which national statistics are available, most girls are cut before the age of five.<ref>For the circumcisers and blade: [[#UNICEF2013|UNICEF 2013]], 2, 44–46; for the ages: 50.</ref> Procedures differ according to the country or ethnic group. They include removal of the [[clitoral hood]] (type 1-a) and [[clitoral glans]] (1-b); removal of the [[Labia minora|inner labia]] (2-a); and removal of the inner and [[Labia majora|outer labia]] and closure of the vulva (type 3). In this last procedure, known as [[#Type III|infibulation]], a small hole is left for the passage of urine and [[Menstruation|menstrual fluid]], the [[vagina]] is opened for [[Sexual intercourse|intercourse]] and opened further for childbirth.{{sfn|Abdulcadir|Margairaz|Boulvain|Irion|2011}} |

|||

Around 125 million women and girls in Africa and the Middle East have undergone FGM.<ref name=UNICEF2013p22>[http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], p. 22 and footnote 62. This estimate uses data from 1997 to 2012 for the 29 countries in which FGM is concentrated.</ref> Over eight million have experienced Type III, which is most common in Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan.<ref>Yoder, Stanley P. and Khan, Shane. [http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/WP39/WP39.pdf "Numbers of women circumcised in Africa"], United States Agency for International Development, March 2008 (hereafter Yoder and Khan (USAID) 2008), p. 14. This report was written at the request of the World Health Organization.</ref> The practice is an ethnic marker, rooted in gender inequality, ideas about purity, modesty and aesthetics, and attempts to control women's sexuality.<ref name=root>[[Stanlie M. James|James, Stanlie M.]] "Female Genital Mutilation," in Bonnie G. Smith (ed.). ''The Oxford Encyclopaedia of Women in World History'', Oxford University Press, 2008 (pp. 259–262), [http://books.google.com/books?id=EFI7tr9XK6EC&pg=PA261 p. 261]: "The most frequently mentioned rationale is the need to control women, especially their sexuality." |

|||

*[[Martha Nussbaum|Nussbaum, Martha]]. "Judging Other Cultures: The Case of Genital Mutilation," ''Sex and Social Justice'', Oxford University Press, 1999 (hereafter Nussbaum 1999), p. 124: "Female genital mutilation is unambiguously linked to customs of male domination." |

|||

*[http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596442_eng.pdf WHO 2008], p. 5: "In every society in which it is practised, female genital mutilation is a manifestation of gender inequality that is deeply entrenched in social, economic and political structures," and [http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/ WHO 2013]: "FGM is recognized internationally as a violation of the human rights of girls and women. It reflects deep-rooted inequality between the sexes, and constitutes an extreme form of discrimination against women." |

|||

*[[Anika Rahman|Rahman, Anika]] and [[Nahid Toubia|Toubia, Nahid]]. ''Female Genital Mutilation: A Guide to Laws and Policies Worldwide'', Zed Books, 2000 (hereafter Rahman and Toubia 2000), [http://books.google.com/books?id=kEG6GaudxQEC&pg=PA5 pp. 5–6]: "A fundamental reason advanced for female circumcision is the need to control women's sexuality ... FC/FGM is intended to reduce women's sexual desire, thus promoting women's virginity and protecting marital fidelity, in the interest of male sexuality." |

|||

*[http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/FactSheet23en.pdf "Harmful Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children"], [[Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights]], Fact Sheet No. 23, section 1A: "It is believed that, by mutilating the female's genital organs, her sexuality will be controlled; but above all it is to ensure a woman's virginity before marriage and chastity thereafter." |

|||

*[[Gerry Mackie|Mackie, Gerry]]. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/2096305 "Ending Footbinding and Infibulation: A Convention Account"], ''American Sociological Review'', 61(6), December 1996, (pp. 999–1017), pp. 999–1000 (hereafter Mackie 1996): "Footbinding and infibulation correspond as follows. Both customs are nearly universal where practiced; they are persistent and are practiced even by those who oppose them. Both control sexual access to females and ensure female chastity and fidelity. Both are necessary for proper marriage and family honor. Both are believed to be sanctioned by tradition. Both are said to be ethnic markers, and distinct ethnic minorities may lack the practices. Both seem to have a past of contagious diffusion. Both are exaggerated over time and both increase with status. Both are supported and transmitted by women, are performed on girls about six to eight years old, and are generally not initiation rites. Both are believed to promote health and fertility. Both are defined as aesthetically pleasing compared with the natural alternative. Both are said to properly exaggerate the complementarity of the sexes, and both are claimed to make intercourse more pleasurable for the male."</ref> It is supported by both women and men in countries that practise it, particularly by the women, who see it as a source of honour and authority, and an essential part of raising a daughter well.<ref>[[Gerry Mackie|Mackie, Gerry]] and LeJeune, John. [http://www.polisci.ucsd.edu/~gmackie/documents/UNICEF.pdf "Social Dynamics of Abandonment of Harmful Practices: A New Look at the Theory"], Innocenti Working Paper, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, 2008 (hereafter Mackie and LeJeune 2008), pp. 6–7: "In the majority of cases it is mothers or grandmothers who organize and support the cutting of their daughters, and in many places the practice is considered 'women's business'. ... The perpetuation of FGM/C and professed support of the practice by women represent one of the chief puzzles that researchers have sought to better understand." |

|||

*Also see [http://www.jstor.org/stable/2096305 Mackie 1996], p. 1009 (available [http://dss.ucsd.edu/~gmackie/documents/MackieASR.pdf here]). |

|||

*Interview with Sudanese surgeon [[Nahid Toubia]], [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/1916917.stm "Changing attitudes to female circumcision"], BBC News, 8 April 2002: "By taking on this practice, which is a woman's domain, it actually empowers them. It is much more difficult to convince the women to give it up, than to convince the men." |

|||

*For recent figures showing support and opposition among women, see [http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], pp. 54–55.</ref> |

|||

The practice is rooted in [[gender inequality]], attempts to control [[human female sexuality|female sexuality]], [[Religious views on female genital mutilation|religious beliefs]] and ideas about purity, modesty, and beauty. It is usually initiated and carried out by women, who see it as a source of honour, and who fear that failing to have their daughters and granddaughters cut will expose the girls to [[social exclusion]].<ref>[[#UNICEF2013|UNICEF 2013]], 15; {{harvnb|Toubia|Sharief|2003}}.</ref> Adverse health effects depend on the type of procedure; they can include recurrent infections, difficulty urinating and passing menstrual flow, [[chronic pain]], the development of [[cyst]]s, an inability to get pregnant, complications during childbirth, and fatal bleeding.{{sfn|Abdulcadir|Margairaz|Boulvain|Irion|2011}} There are no known health benefits.<ref name="WHO2018health">[[#WHO2018|WHO 2018]].</ref> |

|||

FGM has been outlawed in most of the countries in which it occurs, but the laws are poorly enforced.<ref>[http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], p. 8: "Twenty-six countries in Africa and the Middle East have prohibited FGM/C by law or constitutional decree. Two of them – South Africa and Zambia – are not among the 29 countries where the practice is concentrated. ... Legislation prohibiting FGM/C has also been adopted in 33 countries on other continents, mostly to protect children with origins in practising countries." |

|||

*For poor enforcement, see, for example, Rentas, Khadijah. [http://www.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/africa/07/08/uganda.circumcision/ "Uganda seeks to ban female circumcision"], CNN, 8 July 2009.</ref> There has been an international effort since the 1970s to eradicate the practice and in 2012 the [[United Nations General Assembly]] voted unanimously to take all necessary steps to end it.<ref name=UN/> The opposition is not without its critics, particularly among anthropologists; [[Eric Silverman]] writes that FGM is one of anthropology's central moral topics, raising questions about pluralism and multiculturalism within a debate framed by [[Colonialism|colonial]] and [[Postcolonialism|post-colonial]] history.<ref>[[Eric Silverman|Silverman, Eric K.]] [http://www.jstor.org/stable/25064860 "Anthropology and Circumcision"], ''Annual Review of Anthropology'', 33, 2004, pp. 419–445 (hereafter Silverman 2004), pp. 427–428. |

|||

There have been international efforts since the 1970s to persuade practitioners to abandon FGM, and it has been outlawed or restricted in most of the countries in which it occurs, although the laws are often poorly enforced. Since 2010, the United Nations has called upon healthcare providers to stop performing all forms of the procedure, including [[#reinfibulation|reinfibulation]] after childbirth and symbolic "nicking" of the clitoral hood.<ref name="UN2010Askew">[[#UN2010|UN 2010]]; {{harvnb|Askew|Chaiban|Kalasa|Sen|2016}}.</ref> The opposition to the practice is not without its critics, particularly among [[anthropologist]]s, who have raised questions about [[cultural relativism]] and the universality of human rights.<ref>{{harvnb|Shell-Duncan|2008|loc=225}}; {{harvnb|Silverman|2004|loc=420, 427}}.</ref> According to the UNICEF, international FGM rates have risen significantly in recent years, from an estimated 200 million in 2016 to 230 million in 2024, with progress towards its abandonment stalling or reversing in many affected countries.<ref name=":0">{{Cite news |last=Kimeu |first=Caroline |date=2024-03-08 |title=Dramatic rise in women and girls being cut, new FGM data reveals |url=https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2024/mar/08/dramatic-rise-in-women-and-girls-being-cut-new-fgm-data-reveals |access-date=2024-03-12 |work=The Guardian |language=en-GB |issn=0261-3077 |quote=Many African countries have experienced a steady decline in the practice over the past few decades, but overall progress has stalled or been reversed.}}</ref> |

|||

*Also see [[Richard Shweder|Shweder, Richard]]. "'What About Female Genital Mutilation?" And Why Understanding Culture Matters in the First Place" (hereafter Shweder 2002), in Richard A. Shweder, [[Martha Minow]] and [[Hazel Rose Markus]] (eds.), ''Engaging Cultural Differences: The Multicultural Challenge In Liberal Democracies'', Russell Sage Foundation, 2002, p. 212. Also in [http://www.class.uh.edu/faculty/tsommers/moral%20diversity/shweder%20circumcision.pdf ''Daedalus'', 129(4)], Fall 2000.</ref> |

|||

==Terminology== |

==Terminology== |

||

[[File:Samburu female circumcision ceremony, Kenya.jpg|thumb| |

[[File:Samburu female circumcision ceremony, Kenya.jpg|thumb|upright=1.2|left|alt=photograph|[[Samburu people|Samburu]] FGM ceremony, [[Laikipia County|Laikipia]] plateau, Kenya, 2004]] |

||

The practice was mostly known as female circumcision (FC) until the early 1980s.<ref>Rahman and Toubia 2000, [http://books.google.com/books?id=kEG6GaudxQEC&pg=PR10 p. x]; [http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], pp. 6–7.</ref> The [[National Council of Churches of Kenya|Kenya Missionary Council]] began calling it the ''sexual mutilation of women'' in 1929, following the lead of Marion Scott Stevenson (1871–1930), a [[Church of Scotland]] missionary.<ref>Karanja, James. ''The Missionary Movement in Colonial Kenya: The Foundation of Africa Inland Church'', Cuvillier Verlag, 2009, p. 93, footnote 631. |

|||

*Scott, I.G. ''A Saint in Kenya: A Life of Marion Scott Stevenson'', Hodder & Stoughton, 1932.</ref> The term ''female genital mutilation'' was coined in the 1970s by Austrian-American feminist [[Fran Hosken]] (1920–2006), author of ''The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females'' (1979).<ref>Boyle, Elizabeth Heger. ''Female Genital Cutting: Cultural Conflict in the Global Community'', Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002 (hereafter Boyle 2002), p. 25. |

|||

*Johnsdotter, Sara and Essén, Birgitta. [http://www.iscgmedia.com/uploads/6/0/9/7/6097060/johnsdotter_cvs.pdf "Genitals and ethnicity: the politics of genital modifications"], ''Reproductive Health Matters'', 18(35), 2010, pp. 29–37 (hereafter Johnsdotter and Essén 2010), p. 30.</ref> The [[Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children]] began using that term in 1990, and the following year the WHO recommended it to the [[United Nations]].<ref>[http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596442_eng.pdf WHO 2008], p. 22.</ref> It has since become the dominant term within the medical literature to differentiate the severity of the procedures from [[male circumcision]], which involves removal of the foreskin.<ref>[[Martha Nussbaum|Nussbaum, Martha]]. "Judging Other Cultures: The Case of Genital Mutilation," ''Sex and Social Justice'', Oxford University Press, 1999 (hereafter Nussbaum 1999), [http://books.google.com/books?id=7zoaKIolT9oC&pg=PA119 p. 119]. |

|||

*Cappa, Claudia; Wardlaw, Tessa; and Shell-Duncan, Bettina. [http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/fgm_eng.pdf "Changing a harmful social convention: female genital cutting/mutilation"], ''Innocenti Digest'', UNICEF 2005 (hereafter UNICEF 2005).</ref> It is opposed by some commentators, including anthropologist [[Richard Shweder]], who has called it a gratuitous and invidious label.<ref>[[Richard Shweder|Shweder, Richard]]. "When Cultures Collide: Which Rights? Whose Tradition of Values? A Critique of the Global Anti-FGM Campaign," in Christopher L. Eisgruber and András Sajó (eds.), ''Global Justice And the Bulwarks of Localism'', Martinus Nijhoff, 2005, [https://humdev.sites.uchicago.edu/sites/humdev.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shweder/When%20Cultures%20Collide.pdf pp. 181–199] (hereafter Shweder 2005), p. 183.</ref> |

|||

Until the 1980s, FGM was widely known in English as "female circumcision", implying an equivalence in severity with [[male circumcision]].{{sfn|Nussbaum|1999|loc=119}} From 1929 the [[National Council of Churches of Kenya|Kenya Missionary Council]] referred to it as the sexual mutilation of women, following the lead of [[Marion Stevenson|Marion Scott Stevenson]], a [[Church of Scotland]] missionary.{{sfn|Karanja|2009|loc=[https://books.google.com/books?id=F1ezIgyomGIC&pg=PA93 93], n. 631}} References to the practice as mutilation increased throughout the 1970s.<ref name=WHO2008pp4,22>[[#WHO2008|WHO 2008]], 4, 22.</ref> In 1975 [[Rose Oldfield Hayes]], an American anthropologist, used the term ''female genital mutilation'' in the title of a paper in ''[[American Ethnologist]]'',{{sfn|Hayes|1975}} and four years later [[Fran Hosken]] called it mutilation in her influential ''The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females''.{{sfn|Hosken|1994}} The [[Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children]] began referring to it as female genital mutilation in 1990, and the [[World Health Organization]] (WHO) followed suit in 1991.<ref>[[#UNICEF2013|UNICEF 2013]], 6–7.</ref> Other English terms include ''female genital cutting'' (FGC) and ''female genital mutilation/cutting'' (FGM/C), preferred by those who work with practitioners.<ref name=WHO2008pp4,22/> |

|||

Other English terms in use include ''female genital cutting'' (FGC) and ''female genital mutilation/cutting'' (FGM/C).<ref>For FGC and other lesser used terms, see [[Comfort Momoh|Momoh, Comfort]]. "Female genital mutilation" (hereafter Momoh 2005), in Comfort Momoh (ed.), ''Female Genital Mutilation'', Radcliffe Publishing, 2005, [http://books.google.com/books?id=dVjIP0RfVAMC&pg=PA6 p. 6]. |

|||

*For FGM/C, see for example [http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], p. 7. |

|||

*[http://web.archive.org/web/20111123071434/http://www.usaid.gov/our_work/global_health/pop/techareas/fgc/annex.html "Annex to USAID Policy on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C): Explanation of Terminology"], USAID, 2000.</ref> The term ''infibulation'' (Type III FGM) derives from the [[Ancient Rome|Roman]] practice of fastening a [[Fibula (brooch)|fibula]] or brooch across the outer labia of female slaves.<ref>Abdalla, Raqiya Haji Dualeh. ''Sisters in Affliction: Circumcision and Infibulation of Women in Africa'', Zed Books, 1982, p. 10.</ref> |

|||

In countries where FGM is common, the practice's many variants are reflected in dozens of terms, often alluding to purification.<ref name=UNICEF2013p48>[[#UNICEF2013|UNICEF 2013]], 48.</ref> In the [[Bambara language]], spoken mostly in Mali, it is known as ''bolokoli'' ("washing your hands"){{sfn|Zabus|2008|loc=[https://books.google.com/books?id=xZmWF3qxHo4C&pg=PA47 47]}} and in the [[Igbo language]] in eastern Nigeria as ''isa aru'' or ''iwu aru'' ("having your bath").{{efn|For example, "a young woman must 'have her bath' before she has a baby."{{sfn|Zabus|2013|loc=[https://books.google.com/books?id=NCJiAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA40 40]}}}} A common Arabic term for purification has the root ''t-h-r'', used for male and female circumcision (''tahur'' and ''tahara'').{{sfn|El Guindi|2007|loc=[https://books.google.com/books?id=8VQxt634pfcC&pg=PA30 30]}} It is also known in Arabic as ''khafḍ'' or ''khifaḍ''.{{sfn|Asmani|Abdi|2008|loc=3–5}} Communities may refer to FGM as "pharaonic" for [[infibulation]] and "''[[Sunnah|sunna]]''" circumcision for everything else;{{sfn|Gruenbaum|2001|loc=2–3}} ''sunna'' means "path or way" in Arabic and refers to the tradition of [[Muhammad]], although none of the procedures are required within Islam.{{sfn|Asmani|Abdi|2008|loc=3–5}} The term ''infibulation'' derives from [[Fibula (brooch)|''fibula'']], Latin for clasp; the [[Ancient Rome|Ancient Romans]] reportedly fastened clasps through the foreskins or labia of slaves to prevent sexual intercourse. The surgical infibulation of women came to be known as pharaonic circumcision in [[Sudan]] and as Sudanese circumcision in [[Egypt]].{{sfn|Kouba|Muasher|1985|loc=96–97}} In [[Somalia]], it is known simply as ''qodob'' ("to sew up").{{sfn|Abdalla|2007|loc=[https://books.google.com/books?id=JO_SBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA190 190]}} |

|||

''xalaalays'' or ''gudniin'' in Somalia.<ref name=Abdalla2007p190>Abdalla, Raqiya D. "'My Grandmother Called it the Three Feminine Sorrows: The Struggle of Women Against Female Circumcision in Somalia" (hereafter Abdalla 2007), in Rogaia Mustafa Abusharaf (ed.), ''Female Circumcision: Multicultural Perspectives'', University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007, p. 190.</ref> Another term for procedures other than Type III is ''nuss'' ("half"), and a procedure similar to Type III, but where the inner labia are sewn together instead of the outer labia, is called ''al juwaniya'' ("the inside type") in Sudan.<ref>Gruenbaum 2001, pp. 3, 148.</ref> Type III is known as ''pharaonic circumcision'' in Sudan (''tahur faraowniya'', or "pharaonic purification")<ref>[[Janice Boddy|Boddy, Janice]]. ''Civilizing Women: British Crusades in Colonial Sudan'', Princeton University Press, 2007 (hereafter Boddy 2007), p. 1.</ref> – a reference to the practice in [[Ancient Egypt]] under the [[Pharaoh]]s – but as ''Sudanese circumcision'' in Egypt.<ref name=Elmusharaf2006>Elmusharaf, Susan; Elhadi, Nagla; and Almroth, Lars. [http://www.bmj.com/content/333/7559/124.full "Reliability of self reported form of female genital mutilation and WHO classification: cross sectional study"], ''British Medical Journal'', 332(7559), 27 June 2006.</ref> It is known simply as ''qodob'' (to "sew up") in Somalia.<ref name=Abdalla2007p190/> |

|||

==Methods== |

|||

==Procedures and health effects== |

|||

[[File:Clitoral anatomy updated.jpg|thumb|alt=diagram|upright=0.9|Anatomy of the [[clitoris]], showing the [[clitoral glans]], [[Crus of clitoris|clitoral crura]], [[Corpus cavernosum of clitoris|corpora cavernosa]], [[Bulb of vestibule|vestibular bulbs]], and [[Vagina#Vaginal opening and hymen|vagina]]l and [[Urinary meatus|urethral openings]]]] |

|||

The procedures are generally performed by a traditional cutter (''exciseuse'') in the girls' homes, with or without anaesthesia. The cutter is usually an older woman, but in communities where the male [[Barber#History|barber]] has assumed the role of health worker, he will also perform FGM.<ref>[[#UNICEF2013|UNICEF 2013]], 42–44 and table 5, 181 (for cutters), 46 (for home and anaesthesia).</ref>{{efn|UNICEF 2005: "The large majority of girls and women are cut by a traditional practitioner, a category which includes local specialists (cutters or ''exciseuses''), traditional birth attendants and, generally, older members of the community, usually women. This is true for over 80 percent of the girls who undergo the practice in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea, Mali, Niger, Tanzania, and Yemen. In most countries, medical personnel, including doctors, nurses, and certified midwives, are not widely involved in the practice."<ref name=UNICEF2005>[[#UNICEF2005|UNICEF 2005]].</ref>}} When traditional cutters are involved, non-sterile devices are likely to be used, including knives, razors, scissors, glass, sharpened rocks, and fingernails.{{sfn|Kelly|Hillard|2005|loc=491}} According to a nurse in Uganda, quoted in 2007 in ''The Lancet'', a cutter would use one knife on up to 30 girls at a time.{{sfn|Wakabi|2007}} In several countries, health professionals are involved; in Egypt, 77 percent of FGM procedures, and in Indonesia over 50 percent, were performed by medical professionals as of 2008 and 2016.<ref>[[#UNICEF2013|UNICEF 2013]], 43–45.</ref><ref name=UNICEF2016/> |

|||

==Classification{{anchor|classification}}== |

|||

===Circumcisers, methods, age of girls=== |

|||

===Variation=== |

|||

[[File:Clitoris anatomy labeled-en.svg|right|thumb|200px|alt=diagram|Anatomy of the [[vulva]], showing the [[clitoral glans]], [[Crus of clitoris|clitoral crura]], [[Corpus cavernosum of clitoris|corpora cavernosa]], and [[Bulb of vestibule|vestibular bulbs]]]] |

|||

The WHO, UNICEF, and UNFPA issued a joint statement in 1997 defining FGM as "all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs whether for cultural or other non-therapeutic reasons".<ref name=WHO2008pp4,22/> The procedures vary according to the ethnicity and individual practitioners; during a 1998 survey in Niger, women responded with over 50 terms when asked what was done to them.<ref name=UNICEF2013p48/> Translation problems are compounded by the women's confusion over which type of FGM they experienced, or even whether they experienced it.{{sfn|Yoder|Wang|Johansen|2013|loc=190}} Studies have suggested that survey responses are unreliable. A 2003 study in Ghana found that in 1995 four percent said they had not undergone FGM, but in 2000 said they had, while 11 percent switched in the other direction.{{sfn|Jackson|Akweongo|Sakeah|Hodgson|2003}} In Tanzania in 2005, 66 percent reported FGM, but a medical exam found that 73 percent had undergone it.{{sfn|Klouman|Manongi|Klepp|2005}} In Sudan in 2006, a significant percentage of infibulated women and girls reported a less severe type.{{sfn|Elmusharaf|Elhadi|Almroth|2006}} |

|||

The procedures are generally performed, with or without anaesthesia, by a traditional circumciser (a cutter or ''exciseuse''), usually an older woman who also acts as the local midwife, or ''daya'' in Egypt.<ref name=UNICEF2005p7/> They are often conducted inside the girl's family home.<ref name=UNICEF2013p46>[http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], p. 46.</ref> They may also be performed by the local male [[Barber#History|barber]], who assumes the role of health worker in some areas.<ref name=UNICEF2005p7>[http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/fgm_eng.pdf UNICEF 2005], p. 7: "The large majority of girls and women are cut by a traditional practitioner, a category which includes local specialists (cutters or exciseuses), traditional birth attendants and, generally, older members of the community, usually women. This is true for over 80 percent of the girls who undergo the practice in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea, Mali, Niger, Tanzania and Yemen. In most countries, medical personnel, including doctors, nurses and certified midwives, are not widely involved in the practice. |

|||

*[http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013] UNICEF 2013], pp. 42–44. |

|||

*El Hadi, Amal Abd. "Female Genital Mutilation in Egypt" in Meredeth Turshen (ed.), ''African Women's Health'', Africa World Press, 2000, p. 148: "In the main ''dayas'' (female traditional birth attendants) and barbers (male traditional health workers) perform the circumcision, particularly in rural areas and popular urban areas." |

|||

*[http://www.unicef.org/egypt/reallives_3121.html "How a local health barber gave up on FGM/C"], UNICEF, June 2006.</ref> Medical personnel are usually not involved, although a large percentage of FGM procedures in Egypt, Sudan and Kenya are carried out by health professionals, and in Egypt most are performed by physicians, often in people's homes.<ref>[http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], pp. 43, 45.</ref> |

|||

In 2017, during an international meeting of 98 FGM experts, which included physicians, social scientists, policymakers, and activists from 23 countries, a majority of the participants advocated for the revision of FGM/C classifications proposed by the WHO and other UN agencies.<ref name=Elsevier2020/> The experts agreed on legal prohibition of reinfibulation and ritual pricking. They also expressed worry over the harm presented by "the lawfulness of both female genital cosmetic surgeries and male circumcision" in the negation of FGM/C prevention campaigns. The participants, however, differed in their views on the ban of female genital cosmetic surgeries and regular vulvar checkups of female children.<ref name=Elsevier2020>{{Cite journal|last1=Abdulcadir|first1=Jasmine|last2=Bader|first2=Dina|last3=Dubuc|first3=Elise|last4=Alexander|first4=Sophie|date=February 2020|title=Hot topic survey: Discussing the results of experts' responses on controversial issues in FGM/C|url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1701216319311077|journal=[[Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada|Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada]]|volume=42|issue=2|pages=e26 |doi=10.1016/j.jogc.2019.11.064|access-date=22 November 2024}}</ref><ref name=ReproductiveHealth2017>{{cite journal|last1=Abdulcadir|first1=Jasmine|last2=Alexander|first2=Sophie|last3=Dubuc|first3=Elise|last4=Pallitto|first4=Christina|last5=Petignat|first5=Patrick|last6=Say|first6=Lale|date=15 September 2017|title=Female genital mutilation/cutting: sharing data and experiences to accelerate eradication and improve care|url=https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/counter/pdf/10.1186/s12978-017-0361-y.pdf|journal=[[Reproductive Health (journal)|Reproductive Health]]|volume=14|issue=Suppl 1 |pages=4|doi=10.1186/s12978-017-0361-y|doi-access=free |pmid=28950894 |pmc=5607488 |access-date=22 November 2024}}</ref> |

|||

When traditional circumcisers are involved, non-sterile cutting devices are likely to be used, including knives, razors, scissors, cut glass, sharpened rocks and fingernails. [[Cauterization]] is used in parts of Ethiopia.<ref>Kelly, Elizabeth, and Hillard, Paula J. Adams. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16141763 "Female genital mutilation"], ''Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology'', 17(5), October 2005, pp. 490–494 (review), p. 491. |

|||

*[http://www.who.int/gender/other_health/teachersguide.pdf "Female Genital Mutilation: A Teachers' Guide"], World Health Organization, 2005, p. 31: "FGM is carried out using special knives, scissors, razors, or pieces of glass. On rare occasions sharp stones have been reported to be used (e.g. in eastern Sudan), and cauterization (burning) is practised in some parts of Ethiopia. Finger nails have been used to pluck out the clitoris of babies in some areas in the Gambia. The instruments may be re-used without cleaning."</ref> A nurse in Uganda, quoted in 2007 in ''The Lancet'', said a circumciser would use one knife to cut up to 30 girls at a time.<ref>Wakabi, Wairagala. [http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(07)60508-X/fulltext "Africa battles to make female genital mutilation history"], ''The Lancet'', 369 (9567), 31 March 2007, pp. 1069–1070.</ref> With Type III the wound may be [[Surgical suture|sutured]] with surgical thread, or held closed with [[agave]] or [[acacia]] thorns. Depending on the involvement of healthcare professionals, any of the procedures may be conducted with a [[Local anesthetic|local]] or [[general anaesthetic]], or with neither. The most recent data for Egypt, where medical personnel often carry out the procedure, showed that in 60 percent of cases a local anaesthetic was used, in 13 percent a general, and in 25 percent none (two percent were missing/don't know).<ref name=UNICEF2013p46/> |

|||

===Types=== |

|||

The age at which FGM is performed depends on the country; it ranges from shortly after birth to the teenage years.<ref>[http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], p. 50. |

|||

[[File:FGC Types.svg|right|300px|alt=diagram]] |

|||

*Also see [[Nahid Toubia|Toubia, Nahid]]. [http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199409153311106 "Female Circumcision as a Public Health Issue"], ''The New England Journal of Medicine'', 331(11), 1994, pp. 712–716.</ref> The variation in ages signals that the practice is usually not regarded as a rite of passage between childhood and adulthood.<ref>[[Gerry Mackie|Mackie, Gerry]]. "Female Genital Cutting: The Beginning of the End" (hereafter Mackie 2000), in Bettina Shell-Duncan and Ylva Hernlund (eds.), ''Female "Circumcision" in Africa: Culture Controversy and Change'', Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2000 (pp. 253–282), p. 275. also [http://www.polisci.ucsd.edu/~gmackie/documents/BeginningOfEndMackie2000.pdf here]).</ref> In half the countries for which there are data, most girls are cut before the age of five, including over 80 percent in Eritrea, Ghana, Mali, Mauritania and Nigeria. The percentage is reversed in Chad, Central African Republic, Egypt and Somalia, where over 80 percent are cut between the ages of five and 14.<ref>[http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], pp. 47, 50.</ref> A 1997 survey found that 76 percent of girls in Yemen were cut within two weeks of birth.<ref>[http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/fgm_eng.pdf UNICEF 2005], p. 6.</ref> |

|||

[[#Household surveys|Standard questionnaires]] from United Nations bodies ask women whether they or their daughters have undergone the following: (1) cut, no flesh removed (symbolic nicking); (2) cut, some flesh removed; (3) sewn closed; or (4) type not determined/unsure/doesn't know.{{efn|UNICEF 2013: "These categories do not fully match the WHO typology. ''Cut, no flesh removed'' describes a practice known as nicking or pricking, which currently is categorized as Type IV. ''Cut, some flesh removed'' corresponds to Type I (clitoridectomy) and Type II (excision) combined. And ''sewn closed'' corresponds to Type III, infibulation."<ref name=UNICEF2013p48/>}} The most common procedures fall within the "cut, some flesh removed" category and involve complete or partial removal of the clitoral glans.<ref>{{harvnb|Yoder|Wang|Johansen|2013|loc=189}}; [[#UNICEF2013|UNICEF 2013]], 47.</ref> The World Health Organization (a UN agency) created a more detailed typology in 1997: Types I–II vary in how much tissue is removed; Type III is equivalent to the UNICEF category "sewn closed"; and Type IV describes miscellaneous procedures, including symbolic nicking.<ref>[[#WHO2008|WHO 2008]], 4, 23–28; {{harvnb|Abdulcadir|Catania|Hindin|Say|2016}}.</ref> |

|||

{{anchor|classification}} |

|||

====Type I{{anchor|Type I}}==== |

|||

===Classification=== |

|||

''Type I'' is "partial or total removal of the [[clitoral glans]] (the external and visible part of the clitoris, which is a sensitive part of the female genitals), and/or the prepuce/[[clitoral hood]] (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoral glans)".<ref>{{Cite web|title=Female genital mutilation|url=https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation|access-date=2021-04-29|website=www.who.int|language=en|archive-date=29 January 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210129023511/https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation|url-status=live}}</ref> Type Ia{{efn|A diagram in [[#WHO2016|WHO 2016]], copied from {{harvnb|Abdulcadir|Catania|Hindin|Say|2016}}, refers to Type 1a as ''circumcision''.<ref name=WHO2016types>[[#WHO2016|WHO 2016]], [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK368486/box/ch1.box1 Box 1.1 "Types of FGM"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170908222703/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK368486/box/ch1.box1 |date=8 September 2017 }}.</ref>}} involves removal of the [[clitoral hood]] only. This is rarely performed alone.{{efn|WHO (2018): Type 1 ... the partial or total removal of the clitoris ... and in very rare cases, only the prepuce (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoris)."<ref name=WHO2018health/>{{pb}} |

|||

WHO (2008): "[There is a] common tendency to describe Type I as removal of the prepuce, whereas this has not been documented as a traditional form of female genital mutilation. However, in some countries, medicalized female genital mutilation can include removal of the prepuce only (Type Ia) (Thabet and Thabet, 2003), but this form appears to be relatively rare (Satti et al., 2006). Almost all known forms of female genital mutilation that remove tissue from the clitoris also cut all or part of the clitoral glans itself."<ref>[[#WHO2008|WHO 2008]], 25. Also see {{harvnb|Toubia|1994}} and {{harvnb|Horowitz|Jackson|Teklemariam|1995}}.</ref>}} The more common procedure is Type Ib ([[clitoridectomy]]), the complete or partial removal of the [[clitoral glans]] (the visible tip of the clitoris) and clitoral hood.<ref name=WHO2014/><ref>[[#WHO2008|WHO 2008]], 4.</ref> The circumciser pulls the clitoral glans with her thumb and index finger and cuts it off.{{efn|Susan Izett and [[Nahid Toubia]] (WHO, 1998): "[T]he clitoris is held between the thumb and index finger, pulled out and amputated with one stroke of a sharp object."<ref name=WHO1998>[[#WHO1998|WHO 1998]].</ref>}} |

|||

==== |

====Type II{{anchor|Type II}}==== |

||

''Type II'' (excision) is the complete or partial removal of the [[Labia minora|inner labia]], with or without removal of the clitoral glans and [[Labia majora|outer labia]]. Type IIa is removal of the inner labia; Type IIb, removal of the clitoral glans and inner labia; and Type IIc, removal of the clitoral glans, inner and outer labia. ''Excision'' in French can refer to any form of FGM.<ref name=WHO2014/> |

|||

[[File:FGC Types.svg|thumb|200px|alt=diagram|Normal female anatomy and how FGM Types I–III differ from it]] |

|||

The procedure used varies according to ethnicity.<ref name=UNICEF2013p46/> Information about the procedures comes from anthropologists, local health workers, and from a series of surveys conducted by aid agencies since the late 1980s.<ref>[http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], pp. 3–5.</ref><!--check page numbers--> The surveys are based on questionnaires completed by the women themselves, who have responded using 50 different terms for the procedures. Apart from the difficulty of |

|||

comparing and translating these terms across different cultures and languages, the women may not be able to describe what was done to them, procedures vary according to practitioners, and there is considerable overlap between categories. As a result no typology is entirely accurate.<ref>[http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], p. 7. |

|||

*[[Carla Obermeyer|Obermeyer, Carla]]. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/649659 "Female Genital Surgeries: The Known, the Unknown and the Unknowable"], ''Medical Anthropology Quarterly'', 31(1), 1999, pp. 79–106 (hereafter Obermeyer 1999), p. 82; also available [http://csde.washington.edu/fogarty/casestudies/shellduncanmaterials/day%202/Obermeyer,%20C.%20%281999%29%20Female%20genital%20surgeries.pdf here]). |

|||

*For the language problems, see [http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], p. 48, and [http://www.jstor.org/stable/649659 Obermeyer 1999], p. 84.</ref> |

|||

====Type III{{anchor|Type III}}==== |

|||

The WHO divides the main procedures into three categories, Types I–III ''(see image right)''. The organization maintains a fourth category, [[#Type IV|Type IV]], for piercing the clitoris or prepuce (symbolic circumcision) and for miscellaneous procedures not related to FGM as a ritual, such as cutting into the vagina ([[gishiri cutting]]).<ref name=WHOclassification2008>[http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/overview/en/index.html "Classification of female genital mutilation"], World Health Organization, 2013. |

|||

{{quote box |

|||

*For more details, see [http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596442_eng.pdf "Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation"], World Health Organization, 2008 (hereafter WHO 2008), pp. 4, 22–28. |

|||

|border=1px |

|||

:*See p. 4, and Annex 2, p. 24, for the classification into Types I–IV; Annex 2, pp. 23–28, for a more detailed discussion.</ref> A 2006 study, in which 255 girls and 282 women in Sudan were asked to describe their cutting and were then examined, suggested that there was significant under-reporting of the severity of the procedures because the subjects were confusing the WHO's Types II and III.<ref name=Elmusharaf2006/> UNICEF instead uses the following categories: (1) cut, no flesh removed (pricking); (2) cut, some flesh removed; (3) sewn closed; and (4) type not determined/unsure/doesn't know.<ref>[http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], p. 48: "In the most recent MICS and DHS, types of FGM/C are classified into four main categories: 1) cut, no flesh removed, 2) cut, some flesh removed, 3) sewn closed, and 4) type not determined/not sure/doesn't know. These categories do not fully match the WHO typology. Cut, no flesh removed describes a practice known as nicking or pricking, which currently is categorized as Type IV. Cut, some flesh removed corresponds to Type I (clitoridectomy) and Type II (excision) combined. And sewn closed corresponds to Type III, infibulation."</ref> |

|||

|title=External images |

|||

|title_fnt=#555555 |

|||

|halign=left |

|||

|quote={{plainlist}} |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20180207062846/https://smw.ch/resource/jf/jimg/780/780/ratio/journal/file/view/article/smw/en/smw.2011.13137/smw_2011_13137_fig_01_conv.jpg/ Type IIIb (virgin)] |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20180207010148/https://smw.ch/resource/jf/jimg/780/780/ratio/journal/file/view/article/smw/en/smw.2011.13137/smw_2011_13137_fig_02_conv.jpg/ Type IIIb (sexually active)] |

|||

{{endplainlist}} |

|||

|qalign=center |

|||

|fontsize=95% |

|||

|bgcolor=#F9F9F9 |

|||

|width=300px |

|||

|align=right |

|||

|salign=right |

|||

|style=margin–top:1.5em;margin-bottom:1.5em;padding:1em |

|||

|source= — ''[[Swiss Medical Weekly]]''{{sfn|Abdulcadir|Margairaz|Boulvain|Irion|2011}}}} |

|||

''Type III'' ([[infibulation]] or pharaonic circumcision), the "sewn closed" category, is the removal of the external genitalia and fusion of the wound. The inner and/or outer labia are cut away, with or without removal of the clitoral glans.{{efn|WHO 2014: "Narrowing of the vaginal orifice with creation of a covering seal by cutting and appositioning the labia minora and/or the labia majora, with or without excision of the clitoris (infibulation).{{pb}}"Type IIIa, removal and apposition of the labia minora; Type IIIb, removal and apposition of the labia majora."<ref name=WHO2014/>}} Type III is found largely in northeast Africa, particularly Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan (although not in South Sudan). According to one 2008 estimate, over eight million women in Africa are living with Type III FGM.{{efn|USAID 2008: "Infibulation is practiced largely in countries located in northeastern Africa: Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan. ... Sudan alone accounts for about 3.5 million of the women. ... [T]he estimate of the total number of women infibulated in [Djibouti, Somalia, Eritrea, northern Sudan, Ethiopia, Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, Senegal, Chad, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Tanzania, for women 15–49 years old] comes to 8,245,449, or just over eight million women."{{sfn|Yoder|Khan|2008|loc=13–14}}}} According to UNFPA in 2010, 20 percent of women with FGM have been infibulated.<ref name=UNFPATypeIIIestimate>[http://www.unfpa.org/resources/promoting-gender-equality "Frequently Asked Questions on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150104112106/http://www.unfpa.org/resources/promoting-gender-equality |date=4 January 2015 }}, United Nations Population Fund, April 2010.</ref> In Somalia, according to [[Edna Adan Ismail]], the child squats on a stool or mat while adults pull her legs open; a local anaesthetic is applied if available: |

|||

====WHO Types I and II==== |

|||

The WHO's Type I is subdivided into two. Type Ia is the removal of the [[clitoral hood]], which is rarely, if ever, performed alone.<ref>[http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/overview/en/index.html WHO 2013]; [http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596442_eng.pdf WHO 2008], p. 24. |

|||

*[http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199409153311106 Toubia 1994]: "In my extensive clinical experience as a physician in Sudan, and after a careful review of the literature of the past 15 years, I have not found a single case of female circumcision in which only the skin surrounding the clitoris is removed, without damage to the clitoris itself."</ref> More common is Type Ib ([[clitoridectomy]]), the partial or total removal of the clitoris, along with the prepuce.<ref>[http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/overview/en/index.html WHO 2013]; [http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596442_eng.pdf WHO 2008], p. 4; [http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199409153311106 Toubia 1994], pp. 712–716.</ref> Susan Izett and [[Nahid Toubia]] of [[RAINBO]], in a 1998 report for the WHO, wrote: "the clitoris is held between the thumb and index finger, pulled out and amputated with one stroke of a sharp object. Bleeding is usually stopped by packing the wound with gauzes or other substances and applying a pressure bandage. Modern trained practitioners may insert one or two stitches around the clitoral artery to stop the bleeding."<ref>Izett and Toubia, [https://apps.who.int/dsa/cat98/fgmbook.htm "Female Genital Mutilation: An Overview"], World Health Organization, 1998.</ref> |

|||

{{blockquote|The element of speed and surprise is vital and the circumciser immediately grabs the clitoris by pinching it between her nails aiming to amputate it with a slash. The organ is then shown to the senior female relatives of the child who will decide whether the amount that has been removed is satisfactory or whether more is to be cut off. |

|||

Type II is partial or total removal of the clitoris and [[labia minora|inner labia]], with or without removal of the [[labia majora|outer labia]].<ref>[http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/overview/en/index.html WHO 2013]; [http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596442_eng.pdf WHO 2008], p. 4: "Partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora (excision)," and p. 24: "When it is important to distinguish between the major variations that have been documented, the following subdivisions are proposed: Type IIa, removal of the labia minora only; Type IIb, partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora; Type IIc, partial or total removal of the clitoris, the labia minora and the labia majora. Note also that, in French, the term "excision" is often used as a general term covering all types of female genital mutilation."</ref> Type II is known as excision in English, but in French ''excision'' refers to all forms of FGM.<ref>[http://www.unicef.org/media/files/FGCM_Lo_res.pdf UNICEF 2013], p. 7.</ref> |

|||

After the clitoris has been satisfactorily amputated ... the circumciser can proceed with the total removal of the labia minora and the paring of the inner walls of the labia majora. Since the entire skin on the inner walls of the labia majora has to be removed all the way down to the perineum, this becomes a messy business. By now, the child is screaming, struggling, and bleeding profusely, which makes it difficult for the circumciser to hold with bare fingers and nails the slippery skin and parts that are to be cut or sutured together. ... |

|||

====WHO Type III==== |

|||

{{ external media |

|||

| float = right |

|||

| width = 250px |

|||

| image1 = [http://www.smw.ch/fileadmin/smw/images/SMW-2011-13137-Fig-01.jpg Example of Type III FGM],<br/> ''[[Swiss Medical Weekly]]'', January 2011.<ref name=Abdulcadira/> |

|||

}} |

|||

Type III ([[infibulation]]) is the removal of all external genitalia and the fusing of the wound, leaving a small hole (2–3 mm)<ref name=Abdulcadira/> for the passage of urine and menstrual blood. The inner and outer labia are cut away, with or without excision of the clitoris.<ref name=TypeIIIdef>[http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/overview/en/index.html WHO 2013]; [http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596442_eng.pdf WHO 2008], p. 4: "Narrowing of the vaginal orifice with creation of a covering seal by cutting and appositioning the labia minora and/or the labia majora, with or without excision of the clitoris (infibulation)." |

|||

*For the wound being opened for intercourse and childbirth, see Elchalal, Uriel et al. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9326757 "Ritualistic Female Genital Mutilation: Current Status and Future Outlook"], ''Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey'', 52(10), October 1997, pp. 643–651 (hereafter Elchalal et al 1997).</ref> A pinhole is created by inserting something into the wound before it closes, such as a twig or rock salt. The wound may be sutured with surgical thread, or [[agave]] or [[acacia]] thorns may be used to hold the sides together; according to a 1982 study in Sudan, eggs or sugar might be used as an adhesive. The girl's legs are then tied from hip to ankle for 2–6 weeks until the tissue has bonded.<ref>[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9326757 Elchalal et al 1997]. |

|||

*For the eggs and sugar, see El Dareer, Asma. [http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/content/12/2/138.abstract "Attitudes of Sudanese People to the Practice of Female Circumcision"], ''International Journal of Epidemiology'', 1983, 12(2) (pp. 138–144, hereafter El Dareer 1983), p. 138. |

|||

*Momoh 2005, [http://books.google.com/books?id=dVjIP0RfVAMC&pg=PA6 pp. 6–7], also describes an infibulation: |

|||

:*"[E]lderly women, relatives and friends secure the girl in the [[lithotomy position]]. A deep incision is made rapidly on either side from the root of the clitoris to the [[Frenulum of labia minora|fourchette]], and a single cut of the razor excises the clitoris and both the labia majora and labia minora.<p> "Bleeding is profuse, but is usually controlled by the application of various [[poultice]]s, the threading of the edges of the skin with thorns, or clasping them between the edges of a split cane. A piece of twig is inserted between the edges of the skin to ensure a patent [[foramen]] for urinary and menstrual flow. The lower limbs are then bound together for 2–6 weeks to promote [[Hemostasis|haemostatis]] and encourage union of the two sides ... Healing takes place by [[primary intention]], and, as a result, the [[introitus]] is obliterated by a drum of skin extending across the orifice except for a small hole. Circumstances at the time may vary; the girl may struggle ferociously, in which case the incisions may become uncontrolled and haphazard. The girl may be pinned down so firmly that bones may fracture." |

|||

*For a 1977 study and description of Type III, see Pieters, Guy and Lowenfels, Albert B. [http://www.cirp.org/pages/female/pieters1 "Infibulation in the Horn of Africa"], ''New York State Journal of Medicine'', 77(6), April 1977, pp. 729–731. |

|||

*For another description of Type III from the 1970s, see [http://www.middle-east-info.org/league/somalia/hosken.pdf this extract] from Hosken, Fran. ''The Hosken Report'', quoting physician Jacques Lantier, ''La Cité Magique et Magie En Afrique Noire'', Libraire Fayard, 1972.</ref> Anthropologist [[Janice Boddy]] witnessed the infibulation in 1976 of two sisters in northern Sudan by a traditional circumciser using an anaesthetic: |

|||

Having ensured that sufficient tissue has been removed to allow the desired fusion of the skin, the circumciser pulls together the opposite sides of the labia majora, ensuring that the raw edges where the skin has been removed are well approximated. The wound is now ready to be stitched or for thorns to be applied. If a needle and thread are being used, close tight sutures will be placed to ensure that a flap of skin covers the vulva and extends from the mons veneris to the perineum, and which, after the wound heals, will form a bridge of scar tissue that will totally occlude the vaginal introitus.<ref name=Ismail2016p12>{{harvnb|Ismail|2016|loc=12}}.</ref>}} |

|||

{{quote box |

|||

|quote= |

|||

A crowd of ''habobat'' (grandmothers) have gathered in the yard – not a man in sight. ... The girl lies docile on an ''angarib'', beneath which smoulders incence in a cracked clay pot. Her hands and feet are stained with [[henna]] applied the night before. Several kinswomen support her torso; two others hold her legs apart. Miriam [the midwife] thrice injects her genitals with local anesthetic, then, in the silence of the next few moments, takes a small pair of scissors and quickly cuts away her clitoris and labia minora; the rejected tissue is caught in a bowl below the bed. ... I am surprised there is so little blood. ... Miriam staunches the flow with a white cotton cloth. She removes a surgical needle from her midwife's kit ... and threads it with suture. She sews together the girl's outer labia leaving a small opening at the vulva. After a liberal application of antiseptic the operation is over. |

|||

The amputated parts might be placed in a pouch for the girl to wear.{{sfn|El Guindi|2007|loc=[https://books.google.com/books?id=8VQxt634pfcC&pg=PA43 43]}} A single hole of 2–3 mm is left for the passage of urine and menstrual fluid.{{efn|Jasmine Abdulcadir (''Swiss Medical Weekly'', 2011): "In the case of infibulation, the urethral opening and part of the vaginal opening are covered by the scar. In a virgin infibulated woman the small opening left for the menstrual fluid and the urine is not wider than 2–3 mm; in sexually active women and after the delivery the vaginal opening is wider but the urethral orifice is often still covered by the scar."{{sfn|Abdulcadir|Margairaz|Boulvain|Irion|2011}}}} The vulva is closed with surgical thread, or [[agave]] or [[acacia]] thorns, and might be covered with a poultice of raw egg, herbs, and sugar. To help the tissue bond, the girl's legs are tied together, often from hip to ankle; the bindings are usually loosened after a week and removed after two to six weeks.{{sfn|Ismail|2016|loc=14}}{{sfn|Kelly|Hillard|2005|loc=491}} If the remaining hole is too large in the view of the girl's family, the procedure is repeated.{{sfn|Abdalla|2007|loc=[https://books.google.com/books?id=8VQxt634pfcC&pg=PA190 190]}} |

|||

Women gently lift the sisters as their ''angaribs'' are spread with multicolored ''birish''s, "red" bridal mats. The girls seem to be experiencing more shock than pain ... Amid trills of joyous ululations we adjourn to the courtyard for tea; the girls are also brought outside. There they are invested with the ''jirtig'': ritual jewelry, perfumes, and cosmetic pastes worn to protect those whose reproductive ability is vulnerable to attack from malign spirits and the evil eye. The sisters wear bright new dresses, bridal shawls called ''garmosis'' (singular), and their family's gold. Relatives sprinkle guests with cologne, much as they would at a wedding ... Newly circumcised girls are referred to as little brides (''arus''); much that is done for a bride is done for them, but in a minor key. Importantly, they have now been rendered marriageable.<ref name=Boddy1989p50>[[Janice Boddy|Boddy, Janice]]. ''Wombs and Alien Spirits: Women, Men, and the Zar Cult in Northern Sudan'', University of Wisconsin Press, 1989 (hereafter Boddy 1989), [http://books.google.com/books?id=TK6NIp5uVwsC&pg=PA50 p. 50].</ref> |

|||

|fontsize=95% |

|||

|bgcolor= |

|||

|width=85% |

|||

|align=center |

|||

|quoted= |

|||

|salign=right|source= |

|||

}} |

|||

The vagina is opened for sexual intercourse, for the first time either by a midwife with a knife or by the woman's husband with his penis.{{sfn|Abdalla|2007|loc=[https://books.google.com/books?id=8VQxt634pfcC&pg=PA190 190–191], [https://books.google.com/books?id=8VQxt634pfcC&pg=PA198 198]}} In some areas, including Somaliland, female relatives of the bride and groom might watch the opening of the vagina to check that the girl is a virgin.{{sfn|Ismail|2016|loc=14}}{{anchor|defibulation|deinfibulation|reinfibulation}} The woman is opened further for childbirth (''defibulation'' or ''deinfibulation''), and closed again afterwards (''reinfibulation''). Reinfibulation can involve cutting the vagina again to restore the pinhole size of the first infibulation. This might be performed before marriage, and after childbirth, divorce and widowhood.{{efn|Elizabeth Kelly, Paula J. Adams Hillard (''Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology'', 2005): "Women commonly undergo reinfibulation after a vaginal delivery. In addition to reinfibulation, many women in Sudan undergo a second type of re-suturing called El-Adel, which is performed to recreate the size of the vaginal orifice to be similar to the size created at the time of primary infibulation. Two small cuts are made around the vaginal orifice to expose new tissues to suture, and then sutures are placed to tighten the vaginal orifice and perineum. This procedure, also called re-circumcision, is primarily performed after vaginal delivery, but can also be performed before marriage, after cesarean section, after divorce, and sometimes even in elderly women as a preparation before death."{{sfn|Kelly|Hillard|2005|loc=491}}}}{{sfn|El Dareer|1982|loc=56–64}} Hanny Lightfoot-Klein interviewed hundreds of women and men in Sudan in the 1980s about sexual intercourse with Type III: |

|||

Boddy wrote that older women in Sudan recalled a procedure in which the circumciser would scrape away the external genitals with a straight razor, and with no anaesthetic.<ref>Boddy 1989, [http://books.google.com/books?id=TK6NIp5uVwsC&pg=PA51 p. 51].</ref> The infibulated woman's vulva is opened for sexual intercourse, by a penis or knife, and for childbirth. Hanny Lightfoot-Klein, a social psychologist, interviewed 300 Sudanese women and 100 Sudanese men in the 1980s and described the penetration by the men of their wives' infibulation: |

|||

{{blockquote|The penetration of the bride's infibulation takes anywhere from 3 or 4 days to several months. Some men are unable to penetrate their wives at all (in my study over 15%), and the task is often accomplished by a midwife under conditions of great secrecy, since this reflects negatively on the man's potency. Some who are unable to penetrate their wives manage to get them pregnant in spite of the infibulation, and the woman's vaginal passage is then cut open to allow birth to take place. ... Those men who do manage to penetrate their wives do so often, or perhaps always, with the help of the "little knife". This creates a tear which they gradually rip more and more until the opening is sufficient to admit the penis.<ref>{{harvnb|Lightfoot-Klein|1989|loc=380}}; also see {{harvnb|El Dareer|1982|loc=42–49}}.</ref>}} |

|||

{{quote box |

|||

|quote= |

|||

The penetration of the bride's infibulation takes anywhere from 3 or 4 days to several months. Some men are unable to penetrate their wives at all (in my study over 15%), and the task is often accomplished by a midwife under conditions of great secrecy, since this reflects negatively on the man's potency. Some who are unable to penetrate their wives manage to get them pregnant in spite of the infibulation, and the woman's vaginal passage is then cut open to allow birth to take place. ... Those men who do manage to penetrate their wives do so often, or perhaps always, with the help of the "little knife." This creates a tear which they gradually rip more and more until the opening is sufficient to admit the penis. In some women, the scar tissue is so hardened and overgrown with keloidal formations that it can only be cut with very strong surgical scissors, as is reported by doctors who relate cases where they broke scalpels in the attempt.<ref name=Lightfoot>Lightfoot-Klein, Hanny. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/3812643 "The Sexual Experience and Marital Adjustment of Genitally Circumcised and Infibulated Females in The Sudan"], ''The Journal of Sex Research'', 26(3), 1989, pp. 375–392 (also available [http://www.fgmnetwork.org/authors/Lightfoot-klein/sexualexperience.htm here]). |

|||

*Also see Lightfoot-Klein, Hanny. ''Prisoners of Ritual: An Odyssey Into Female Genital Circumcision in Africa'', Routledge, 1989.</ref> |

|||

|fontsize=95% |

|||

|bgcolor= |

|||

|width=85% |

|||

|align=center |

|||

|quoted= |

|||

|salign=right|source= |

|||

}} |

|||

====Type IV{{anchor|Type IV}}==== |

|||

Defibulation, or deinfibulation, reverses the closure of the vagina; this is performed before childbirth, or at the request of a woman seeking to have her genitals repaired.<ref>[http://www.smw.ch/content/smw-2011-13137/ Abdulcadira et al 2011]. |

|||

''Type IV'' is "[a]ll other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes", including pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization.<ref name=WHO2014/> It includes nicking of the clitoris (symbolic circumcision), burning or scarring the genitals, and introducing substances into the vagina to tighten it.<ref>[[#WHO2008|WHO 2008]], 24.</ref><ref>[[#UNICEF2013|UNICEF 2013]], 7.</ref> [[Labia stretching]] is also categorized as Type IV.<ref name="WHO 2008, 27">[[#WHO2008|WHO 2008]], 27.</ref> Common in southern and eastern Africa, the practice is supposed to enhance sexual pleasure for the man and add to the sense of a woman as a closed space. From the age of eight, girls are encouraged to stretch their inner labia using sticks and massage. Girls in Uganda are told they may have difficulty giving birth without stretched labia.{{efn|WHO 2005: "In some areas (e.g. parts of Congo and mainland Tanzania), FGM entails the pulling of the labia minora and/or clitoris over a period of about 2 to 3 weeks. The procedure is initiated by an old woman designated for this task, who puts sticks of a special type in place to hold the stretched genital parts so that they do not revert back to their original size. The girl is instructed to pull her genitalia every day, to stretch them further, and to put additional sticks in to hold the stretched parts from time to time. This pulling procedure is repeated daily for a period of about two weeks, and usually, no more than four sticks are used to hold the stretched parts, as further pulling and stretching would make the genital parts unacceptably long."<ref>[[#WHO2005|WHO 2005]], 31.</ref>}}<ref>For the countries in which labia stretching is found (Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe), see {{harvnb|Nzegwu|2011|loc=[https://books.google.com/books?id=xSqIrrswbG0C&pg=PA262 262]}}; for the rest, {{harvnb|Bagnol|Mariano|2011|loc=[https://books.google.com/books?id=xSqIrrswbG0C&pg=PA272 272–276] (272 for Uganda)}}.</ref> |

|||

*Also see Nour, N.M.; Michaels, K.B.; and Bryant, A.E. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2016816056 "Defibulation to Treat Female Genital Cutting: Effect on Symptoms and Sexual Function"], ''Obstetrics & Gynecology'', 108(1), July 2006, pp. 55–60. |

|||

*Conant, Eve. [http://www.newsweek.com/id/218692 "The Kindest Cut"], ''Newsweek'', 27 October 2009. |

|||

*Foldes, Pierre. [http://www.wasvisual.com/Video_by_Pierre_Foldes_on_Surgical_Repair_Of_The_Clitoris_After_Ritual_Genital_Mutilation_Results_On_453_Cases.html "Surgical Repair of the Clitoris after Ritual Genital Mutilation: Results of 453 Cases"], WAS Visual, accessed 17 September 2011.</ref> After giving birth, women may ask that the infibulation be restored.<ref name=Abdulcadira/> Reinfibulation may also be carried out if a woman's husband is travelling away from home for a protracted period, after divorce or to prepare elderly women for death.<!--check source--><ref name=Bergrren>Bergrren, Vanja et al. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17217115 "Being Victims or Beneficiaries? Perspectives on Female Genital Cutting and Reinfibulation in Sudan"], ''African Journal of Reproductive Health'', 10(2), August 2006. |

|||

*Serour G.I. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20138274 "The issue of reinfibulation"], ''International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstretrics'', 109(2), May 2010, pp. 93–96.</ref> |

|||

A definition of FGM from the WHO in 1995 included [[gishiri cutting]] and angurya cutting, found in Nigeria and Niger. These were removed from the WHO's 2008 definition because of insufficient information about prevalence and consequences.<ref name="WHO 2008, 27"/> Angurya cutting is excision of the [[hymen]], usually performed seven days after birth. Gishiri cutting involves cutting the vagina's front or back wall with a blade or penknife, performed in response to infertility, obstructed labour, and other conditions. In a study by Nigerian physician Mairo Usman Mandara, over 30 percent of women with gishiri cuts were found to have [[vesicovaginal fistula]]e (holes that allow urine to seep into the vagina).<ref>{{harvnb|Mandara|2000|loc=[https://books.google.com/books?id=rhhRXiJIGEcC&pg=PA98 98], 100; for fistulae, 102}}; also see {{harvnb|Mandara|2004}}</ref> |

|||

====WHO Type IV==== |

|||

A variety of procedures are known as Type IV, which the WHO defines as "all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, for example, pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization." These range from ritual nicking of the clitoris (ritual circumcision) to [[gishiri cutting]], angurya cutting, burning or scarring the genitals, and introducing substances into the vagina to tighten it.<ref name=WHO2008p24>[http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596442_eng.pdf WHO 2008], p. 24.</ref> [[Labia stretching]] is also categorized as Type IV FGM; in Tanzania and the Congo girls are told to stretch the clitoris and labia minora every day for 2–3 weeks; an older woman uses sticks to hold the stretched parts in place.<ref>[http://www.who.int/gender/other_health/teachersguide.pdf "Female Genital Mutilation: A Teachers' Guide"], World Health Organization, 2005, p. 31.</ref> Gishiri cutting involves cutting the vagina's anterior (front) wall to enlarge it, and angurya cuts involve scraping tissue away from around the vagina. Another procedure is [[hymenotomy]], the removal of a [[hymen]] regarded as too thick, which is practised by the [[Hausa people|Hausa]] in West Africa.<ref>Mandara, Mairo Usman. "Female genital cutting in Nigeria: View of Nigerian Doctors on the Medicalization Debate," in Shell-Duncan and Hernlund, 2000, p. 95ff. |

|||

*Also see James, Stanlie M. "Female Genital Mutilation," in Bonnie G. Smith (ed.). ''The Oxford Encyclopaedia of Women in World History'', Oxford University Press, 2008 (pp. 259–262), [http://books.google.com/books?id=EFI7tr9XK6EC&pg=PA259 p. 259]. |

|||

*[https://apps.who.int/dsa/cat98/fgmbook.htm Izett and Toubia (WHO), 1998].</ref> The WHO does not include cosmetic procedures such as [[labiaplasty]] or procedures used in [[sex reassignment surgery]] within its FGM categories (see [[#comparison|below]]).<ref name=WHOelective/> |

|||

==Complications== |

|||

===Short term=== |

|||

FGM has no known health benefits.<ref name=Berg2013>Berg, Rigmor C. and Denisona Eva. [http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07399332.2012.721417#tabModule "A Tradition in Transition: Factors Perpetuating and Hindering the Continuance of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C) Summarized in a Systematic Review"], ''Health Care for Women International'', 34(10), 2013 (review): "According to leading health organizations, there are no known health benefits to FGM/C ..."</ref> It has immediate and late [[complication (medicine)|complication]]s, which depend on several factors: the type of FGM; the conditions in which the procedure took place and whether the practitioner had medical training; whether unsterilized or surgical single-use instruments were used; whether surgical thread was used instead of agave or acacia thorns; the availability of antibiotics; how small a hole was left for the passage of urine and menstrual blood; and whether the procedure was performed more than once (for example, to close an opening regarded as too wide or re-open one too small).<ref name=Abdulcadira/> |

|||

[[File:Anti-FGM campaign, Walala Biyotey, 25 January 2014.jpg|thumb|left|upright=1.5|alt=photograph|FGM awareness session run by the [[African Union Mission to Somalia]] at the Walalah Biylooley refugee camp, [[Mogadishu]], 2014]] |

|||