Croats: Difference between revisions

Medizinball (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

m Typo fixing, replaced: districs → districts, per source - the quote is on page 274. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|South Slavic ethnic group}} |

|||

{{for|the medieval Catalan currency|Croat (coin)}} |

|||

{{For|the 17th-century light cavalry|Croats (military unit)}} |

|||

{{pp-protected|reason=Persistent disruptive editing |expiry=22 July 2014|small=yes}} |

|||

{{Redirect2|Croatians|Croatian people|the more generic usage|Croatians (demonym)}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2013}} |

|||

{{Redirect|Croat|the medieval Catalan currency|Croat (coin)|the surname|Croat (surname)}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=March 2023}} |

|||

{{Infobox ethnic group |

{{Infobox ethnic group |

||

| group = Croats |

| group = Croats<br /> ''Hrvati'' |

||

| native_name = |

|||

| image = |

|||

| native_name_lang = |

|||

{{image array|perrow=4|width=75|height=90 |

|||

| flag = |

|||

| image1 = Tomislav crop.jpg | caption1 = [[Tomislav of Croatia|Tomislav]] |

|||

| flag_caption = |

|||

| image2 = KraljTomislav.jpg | caption2 = [[Demetrius Zvonimir of Croatia|Zvonimir]] |

|||

| image = Oton Ivekovic, Dolazak Hrvata na Jadran.jpg |

|||

| image3 = Marko Marulic bust.jpg | caption3 = [[Marko Marulić]] |

|||

| caption = ''Dolazak Hrvata'' (''Arrival of Croats''), painting by [[Oton Iveković]], representing the migration of Croats to the [[Adriatic Sea]] |

|||

| image4 = Nikola Zrinski crop.jpg | caption4 = [[Nikola Šubić Zrinski|Nikola Š. Zrinski]] |

|||

| population = {{circa|'''7–8 million'''}}<ref>{{cite book|last=Bellamy|first=Alex J.|year=2003|title=The Formation of Croatian National Identity: A Centuries-Old Dream|publisher=Manchester University Press|location=Manchester, England|isbn=978-0-71906-502-6|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=T3PqrrnrE5EC|page=116|access-date=12 July 2020|archive-date=27 September 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230927201650/https://books.google.com/books?id=T3PqrrnrE5EC|url-status=live}}</ref>[[File:Map of the Croatian Diaspora in the World (2022).png|center|frameless|260x260px]] |

|||

| image5 = Ivan Gundulic crop.jpg | caption5 = [[Ivan Gundulić]] |

|||

| regions = {{Flag|Croatia}}<br />3,550,000 <small>(2021)</small><ref>{{Croatian Census 2011 |url=http://web.dzs.hr/Eng/censuses/census2011/results/htm/E01_01_04/e01_01_04_RH.html |title=2. Population by ethnicity, by towns/municipalities |access-date=2013-03-26 }}</ref><br />{{Flag|Bosnia and Herzegovina}}<br />544,780 <small>(2013)</small><ref>{{cite book|title=Sarajevo, juni 2016. Cenzus of Population, Households and Dwellings in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2013 Final Results|publisher=BHAS|url=http://www.popis2013.ba/popis2013/doc/Popis2013prvoIzdanje.pdf|access-date=30 June 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171224103940/http://www.popis2013.ba/popis2013/doc/Popis2013prvoIzdanje.pdf|archive-date=24 December 2017}}</ref> |

|||

| image6 = Ruder Boskovic crop.jpg| caption6 = [[Ruđer Bošković]] |

|||

| region1 = {{Flag|United States}} |

|||

| image7 = Josip Jelacic crop.jpg| caption7 = [[Josip Jelačić]] |

|||

| pop1 = 414,714 <small>(2012)</small><ref>[https://archive.today/20200212212618/http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_12_1YR_B04003&prodType=table- Results ] American Fact Finder (US Census Bureau)</ref>–1,200,000 <small>(est.)</small><ref>[https://hrvatiizvanrh.gov.hr/hrvati-izvan-rh-2463/croatian-diaspora/croatian-diaspora-in-the-united-states-of-america/2485 Croatian diaspora in the USA] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210507182154/https://hrvatiizvanrh.gov.hr/hrvati-izvan-rh-2463/croatian-diaspora/croatian-diaspora-in-the-united-states-of-america/2485 |date=7 May 2021 }}. "It has been estimated that around 1,200,000 Croats and their descendants live in the USA."</ref> |

|||

| image8 = Josip Juraj Strossmayer crop.jpg| caption8 = [[Josip Juraj Strossmayer|Strossmayer]] |

|||

| region2 = {{Flag|Germany}} |

|||

| image9 = Ivana Brlic-Mazuranic infobox crop.jpg | caption9 = [[Ivana Brlić-Mažuranić|Brlić-Mažuranić]] |

|||

| pop2 = 500,000 <small>(2021)</small><ref name=destatis/> |

|||

| image10 = ภาพถ่ายของAndria Mohorovicic.gif | caption10 = [[Andrija Mohorovičić|A. Mohorovičić]] |

|||

| ref2 = <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/en/hmiu/croatian-diaspora-in-federal-republic-of-germany/32|title=State Office for Croats Abroad |publisher=Hrvatiizvanrh.hr |access-date=18 March 2015|archive-date=30 September 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180930225834/http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/en/hmiu/croatian-diaspora-in-federal-republic-of-germany/32}}</ref> |

|||

| image11 = Stjepan Radic crop.jpg | caption11 = [[Stjepan Radić]] |

|||

| region3 = {{flag|Chile}} |

|||

| image12 = Josip_Broz_Tito_Bihać_1942.jpg | caption12 = [[Josip Broz Tito]] |

|||

| pop3 = 400,000 |

|||

| image13 = Ivo Andric crop.jpg | caption13 = [[Ivo Andrić]] |

|||

| ref3 = <ref>[http://hrvatskimigracije.es.tl/Diaspora-Croata.htm Diaspora Croata] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160509095402/http://hrvatskimigracije.es.tl/Diaspora-Croata.htm |date=9 May 2016 }} ''El Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de la República de Chile evalúa que en ese país actualmente viven 380.000 personas consideradas de ser de descendencia croata, lo que es un 2,4% de la población total de Chile.''</ref> |

|||

| image14 = Vladimir Prelog crop.jpg | caption14 = [[Vladimir Prelog]] |

|||

| region4 = {{flag|Argentina}} |

|||

| image15 = Goran Ivanisevic crop.jpg | caption15 = [[Goran Ivanišević|Ivanišević]] |

|||

| pop4 = 250,000 |

|||

| image16 = Blanka Vlasic crop.jpg | caption16 = [[Blanka Vlašić]] |

|||

| ref4 = <ref name="croata"/> |

|||

| region5 = {{flag|Austria}} |

|||

| pop5 = 220,000 |

|||

| ref5 = <ref name="hrvatiizvanrh.hr">{{cite web |author=Fer Projekt, Put Murvice 14, Zadar, Hrvatska, +385 98 212 96 00, www.fer-projekt.com |url=http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/hr/hmiu/hrvatska-manjina-u-republici-austriji/3 |title=Hrvatska manjina u Republici Austriji |publisher=Hrvatiizvanrh.hr |access-date=2017-03-10 |archive-date=2017-03-15 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170315173008/http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/hr/hmiu/hrvatska-manjina-u-republici-austriji/3 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

| region6 = {{flag|Australia}} |

|||

| pop6 = 164,362 <small>(2021)</small> |

|||

| ref6 =<ref name="abs1">{{cite web |title=People in Australia Who Were Born in Croatia |website=Australian Bureau of Statistics |date=2021 |publisher=Commonwealth of Australian |at=sec. "Cultural diversity" |url=https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/3204_AUS |access-date=23 June 2023}}</ref>– 250,000 <small>(est.)</small><ref>https://hrvatiizvanrh.gov.hr/hrvati-izvan-rh/hrvatsko-iseljenistvo/hrvatsko-iseljenisto-u-australiji/751 {{Bare URL inline|date=August 2024}}</ref> |

|||

| region7 = {{flag|Canada}} |

|||

| pop7 = 130,280 <small>(2021)</small> |

|||

| ref7 = <ref name=":2">{{Cite web |title=Population by national and/or ethnic group, sex and urban/rural residence |url=https://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=POP&f=tableCode:26 |access-date=17 June 2024}}</ref>– 250,000 <small>(est.)</small><ref>https://hrvatiizvanrh.gov.hr/hrvati-izvan-rh/hrvatsko-iseljenistvo/hrvatsko-iseljenistvo-u-kanadi/762 {{Bare URL inline|date=August 2024}}</ref> |

|||

| region8 = {{flag|New Zealand}} |

|||

| pop8 = 100,000 |

|||

| ref8 = <ref name="voxy.co.nz">{{Cite web |title=Carter: NZ Celebrates 150 Years of Kiwi-Croatian Culture |url=http://www.voxy.co.nz/politics/carter-nz-celebrates-150-years-kiwi-croatian-culture/5/1618 |access-date=2022-11-29 |website=voxy.co.nz |language=en |archive-date=31 December 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191231174022/http://www.voxy.co.nz/politics/carter-nz-celebrates-150-years-kiwi-croatian-culture/5/1618 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

| region9 = {{flag|Switzerland}} |

|||

| pop9 = 80,000 <small>(2021)</small> |

|||

| ref9 = <ref name="admin.ch"/> |

|||

| region10 = {{flag|Brazil}} |

|||

| pop10 = 70,000 |

|||

| ref10 = <ref name="croata"/> |

|||

| region11 = {{flag|Italy}} |

|||

| pop11 = 60,000 |

|||

| ref11 = <ref>{{cite web|url=https://hrvatiizvanrh.gov.hr/print.aspx?id=2476&url=print|title=Croatian diaspora in Italy|publisher=Središnji državni ured za Hrvate izvan Republike Hrvatske|access-date=25 January 2020|language=en|archive-date=5 July 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200705170145/https://hrvatiizvanrh.gov.hr/print.aspx?id=2476&url=print}}</ref> |

|||

| region12 = {{flag|Slovenia}} |

|||

| pop12 = 50,000 <small>(est.)</small> |

|||

| ref12 = <ref name="stat.si"/> |

|||

| region13 = {{flag|Paraguay}} |

|||

| pop13 = 41,502 <small>(2023)</small> |

|||

| ref13 = <ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.imin.hr/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Aktualno-stanje-i-projekcije.-Paragvaj_02.pdf|access-date=30 April 2023|title=Situación actual y proyecciones del desarrollo futuro de la población de origen croata en Paraguay|website=imin.hr|date=January 2023|archive-date=3 February 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230203203406/https://www.imin.hr/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Aktualno-stanje-i-projekcije.-Paragvaj_02.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| region14 = {{flag|France}} |

|||

| pop14 = 40,000 <small>(est.)</small> |

|||

| ref14 = <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/dossiers-pays/croatie/presentation-de-la-croatie/|title=Présentation de la Croatie|publisher=[[Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Development (France)|Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Development]]|access-date=28 June 2016|language=fr|archive-date=30 June 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160630102939/http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/dossiers-pays/croatie/presentation-de-la-croatie|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| region15 = {{flag|Serbia}} |

|||

| pop15 = 39,107 <small>(2022)</small> |

|||

| ref15 = <ref>{{cite web|url=https://popis2022.stat.gov.rs/popisni-podaci-eksel-tabele/|title=ПОПИС 2022 - еxcел табеле | О ПОПИСУ СТАНОВНИШТВА|access-date=2024-09-23}}</ref> |

|||

| region16 = {{flag|Sweden}} |

|||

| pop16 = 35,000 <small>(est.)</small> |

|||

| ref16 = <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/hr/hmiu/hrvatsko-iseljenistvo-u-svedskoj/36|title=Hrvatsko iseljeništvo u Švedskoj|language=hr|website=Hrvatiizvanrh.hr|access-date=18 March 2015|archive-date=20 February 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190220025126/http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/hr/hmiu/hrvatsko-iseljenistvo-u-svedskoj/36}}</ref> |

|||

{{collapsed infobox section begin|'''Other countries<br />(fewer than 30,000)'''}} |

|||

| region17 = {{flag|Hungary}} |

|||

| pop17 = 22,995 <small>(2016)</small> |

|||

| ref17 = <ref name="KSH">{{cite report |last=Vukovich |first=Gabriella |url=http://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xftp/idoszaki/mikrocenzus2016/mikrocenzus_2016_12.pdf |title=Mikrocenzus 2016 – 12. Nemzetiségi adatok |trans-title=2016 microcensus – 12. Ethnic data |language=hu |work=Hungarian Central Statistical Office |location=Budapest |year=2018 |access-date=9 January 2019 |isbn=978-963-235-542-9 |archive-date=8 August 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190808024307/http://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xftp/idoszaki/mikrocenzus2016/mikrocenzus_2016_12.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| region18 = {{flag|Ireland}} |

|||

| pop18 = 20,000 - 50,000 <small> (2019)</small> |

|||

| ref18 = <ref>{{cite news | url = https://novac.jutarnji.hr/aktualno/ugledni-ekspert-otkrio-koliko-je-tocno-hrvata-otislo-u-irsku-znam-i-zasto-taj-broj-pada/8419346/ | language = hr | newspaper = [[Jutarnji list]] | title = Ugledni ekspert otkrio koliko je točno Hrvata otišlo u Irsku: 'Znam i zašto taj broj pada' | first = Lidija | last = Gnjidić Krnić | date = 25 February 2019 | access-date = 4 September 2021}}</ref> |

|||

| region19 = {{flag|Netherlands}} |

|||

| pop19 = 10,000 |

|||

| ref19 = <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/en/hmiu/croatian-diaspora-in-the-kingdom-of-the-netherlands/29|title=State Office for Croats Abroad|website=Hrvatiizvanrh.hr|access-date=18 March 2015|archive-date=20 February 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190220025341/http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/en/hmiu/croatian-diaspora-in-the-kingdom-of-the-netherlands/29}}</ref> |

|||

| region20 = {{flag|Bolivia}} |

|||

| pop20 = 10,000 |

|||

| ref20 = <ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.hia.com.hr/iseljenici/iseljenici01.html |title=Veza s Hrvatima izvan Hrvatske |access-date=2015-03-18 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070304011728/http://www.hia.com.hr/iseljenici/iseljenici01.html |archive-date=2007-03-04 }}</ref> |

|||

| region21 = {{flag|South Africa}} |

|||

| pop21 = 8,000 |

|||

| ref21 = <ref name="hic.hr">{{cite web|url=http://www.hic.hr/dom/227/dom08.htm|title=Dom i svijet – Broj 227 – Croatia klub u Juznoj Africi|access-date=18 March 2015|archive-date=28 March 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170328134446/http://www.hic.hr/dom/227/dom08.htm|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

| region22 = {{flag|United Kingdom}} |

|||

| pop22 = 6,992 |

|||

| ref22 = <ref name="oecd.org"/> |

|||

| region23 = {{flag|Romania}} |

|||

| pop23 = 4,842 <small>(2021)</small> |

|||

| ref23 = <ref name=":2" /> |

|||

| region24 = {{flag|Montenegro}} |

|||

| pop24 = 6,021 <small>(2011)</small> |

|||

| ref24 = <ref name="monstat.org"/> |

|||

| region25 = {{flag|Peru}} |

|||

| pop25 = 6,000 |

|||

| ref25 = <ref name="croata"/> |

|||

| region26 = {{flag|Colombia}} |

|||

| pop26 = 5,800 <small>(est.)</small> |

|||

| ref26 = <ref name="croata"/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cancilleria.gov.co/republica-croacia|title=República de Croacia|work=Cancillería|date=26 September 2013|access-date=20 February 2015|archive-date=22 December 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141222030615/http://www.cancilleria.gov.co/republica-croacia|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| region27 = {{flag|Denmark}} |

|||

| pop27 = 5,400 |

|||

| ref27 = <ref name="joshuaproject.net"/> |

|||

| region28 = {{flag|Norway}} |

|||

| pop28 = 5,272 |

|||

| ref28 = <ref name="ssb.no">{{cite web|url=http://www.ssb.no/219754/population-by-immigrant-category-and-country-background|title=Population by immigrant category and country background.|date=1 January 2015|publisher=Statistics Norway|access-date=18 March 2015|archive-date=15 July 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180715093942/https://www.ssb.no/219754/population-by-immigrant-category-and-country-background|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| region29 = {{flag|Ecuador}} |

|||

| pop29 = 4,000 |

|||

| ref29 = <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/en/hmiu/croatian-diaspora-in-paraguay/33|title=State Office for Croats Abroad|website=Hrvatiizvanrh.hr|access-date=18 March 2015|archive-date=1 February 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190201083201/http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/en/hmiu/croatian-diaspora-in-paraguay/33}}</ref> |

|||

| region30 = {{flag|Slovakia}} |

|||

| pop30 = 2,001<ref>{{Cite web |title=SODB2021 – Obyvatelia – Základné výsledky |url=https://www.scitanie.sk/obyvatelia/zakladne-vysledky/struktura-obyvatelstva-podla-narodnosti/SR/SK0/SR |access-date=2022-08-25 |publisher=scitanie.sk |archive-date=31 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220531025903/https://www.scitanie.sk/obyvatelia/zakladne-vysledky/struktura-obyvatelstva-podla-narodnosti/SR/SK0/SR |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=SODB2021 – Obyvatelia – Základné výsledky |url=https://www.scitanie.sk/obyvatelia/zakladne-vysledky/struktura-obyvatelstva-podla-dalsej-narodnosti/SR/SK0/SR |access-date=2022-08-25 |website=scitanie.sk |archive-date=15 July 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220715111536/https://www.scitanie.sk/obyvatelia/zakladne-vysledky/struktura-obyvatelstva-podla-dalsej-narodnosti/SR/SK0/SR |url-status=live }}</ref>–2,600 |

|||

| ref30 = <ref name="Glas Koncila"/> |

|||

| region31 = {{flag|Czech Republic}} |

|||

| pop31 = 2,490 |

|||

| ref31 = <ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.czso.cz/documents/11292/27914491/1312_c01t14.pdf/17c97f0e-03e1-4a81-84e0-02695b9a637b?version=1.0|title=Croats of Czech Republic: Ethnic People Profile|work=czso.cz|publisher=[[Czech Statistical Office]]|access-date=17 April 2017|archive-date=9 March 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210309060248/https://www.czso.cz/documents/11292/27914491/1312_c01t14.pdf/17c97f0e-03e1-4a81-84e0-02695b9a637b?version=1.0|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| region32 = {{flag|Portugal}} |

|||

| pop32 = 499 |

|||

| ref32 = <ref>{{cite web|url=https://sefstat.sef.pt/Docs/Rifa2020.pdf|title=Sefstat|access-date=13 February 2022|archive-date=20 March 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220320102358/https://sefstat.sef.pt/Docs/Rifa2020.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| region33 = {{flag|Russia}} |

|||

| pop33 = 304 |

|||

| ref33 = <ref>[http://www.gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/perepis2010/croc/Documents/Vol4/pub-04-01.pdf Всероссийская перепись населения 2010. Национальный состав населения] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180906073144/http://www.perepis2002.ru/content.html?id=11 |date=6 September 2018 }} {{in lang|ru}}</ref> |

|||

{{collapsed infobox section end}} |

|||

| region34 = '''[[List of European countries|Europe]]''' |

|||

| pop34 = {{circa|'''5,200,000'''}} |

|||

| ref34 = |

|||

| region35 = '''[[List of North American countries|North America]]''' |

|||

| pop35 = {{circa|'''600,000–2,500,000'''}} |

|||

| ref35 = {{ref label|a|a}} |

|||

| region36 = '''[[List of South American Countries|South America]]''' |

|||

| pop36 = {{circa|'''500,000–800,000'''}} |

|||

| ref36 = |

|||

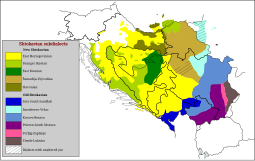

| langs = [[Croatian language|Croatian]]<br />{{hlist|([[Kajkavian]]|[[Shtokavian]]|[[Chakavian]])|}} |

|||

| rels = Predominantly [[Catholic Church in Croatia|Roman Catholic]]<ref name="Martin 1997">{{cite book|last=Marty|first=Martin E.|title=Religion, Ethnicity, and Self-Identity: Nations in Turmoil|year=1997|publisher=University Press of New England|quote=[...] the three ethnoreligious groups that have played the roles of the protagonists in the bloody tragedy that has unfolded in the former Yugoslavia: the Christian Orthodox Serbs, the Catholic Croats, and the Muslim Slavs of Bosnia.|isbn=0-87451-815-6|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/religionethnicit00mart}}</ref> |

|||

| related = Other [[South Slavs]]<ref name="ethnologue.com"/> |

|||

| footnotes = {{note label|a|a}} References:<ref name="Farkas">{{cite book|last=Farkas|first=Evelyn|page=99|title=Fractured States and U.S. Foreign Policy. Iraq, Ethiopia, and Bosnia in the 1990s|year=2003|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan US}}</ref><ref name="Paquin">{{cite book|last=Paquin|first=Jonathan|page=68|title=A Stability-Seeking Power: US Foreign Policy and Secessionist Conflicts|year=2010|publisher=McGill-Queen's University Press}}</ref><ref name="Directory of Historical Organizatio">{{cite book|page=205|title=Directory of Historical Organizations in the United States and Canada|year=2002|publisher=American Association for State and Local History}}</ref><ref name="Zanger">{{cite book|last=Zanger|first=Mark|page=80|title=The American Ethnic Cookbook for Students|year=2001|publisher=Greenwood}}</ref><ref name="Levinson, Ember">{{cite book |last1=Levinson |first1=Ember |last2=David |first2=Melvin |page=[https://archive.org/details/americanimmigran00davi/page/191 191] |title=American immigrant cultures: builders of a nation |url=https://archive.org/details/americanimmigran00davi |url-access=registration |year=1997 |publisher=Macmillan}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|page=690|title=Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs Appropriations for 1994: Testimony of members of Congress and other interested individuals and organizations|year=1993|publisher=United States. Congress. House. Committee on Appropriations. Subcommittee on Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs}}</ref><ref name="National Genealogical Inquirer">{{cite book|page=47|title=National Genealogical Inquirer|year=1979|publisher=Janlen Enterprises}}</ref> |

|||

| region37 = '''Other''' |

|||

| ref37 = {{circa|'''300,000–350,000'''}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Croats}} |

|||

| poptime = 7.5 - 8.5 million (est.)<ref name=diasporas/><ref name=HWC/><ref name=NationalMinor/><ref>[http://www.hia.com.hr/iseljenici/iseljenici01.html Croatian Expatriates ('''in Croatian''')]</ref> |

|||

| popplace = {{flagicon|CRO}} [[Croatia]] 3,874,321 (2011) census<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dzs.hr/Eng/censuses/census2011/results/htm/E01_01_04/e01_01_04_RH.html |title=Central Bureau of Statistics |publisher=Dzs.hr |date= |accessdate=2013-03-26}}</ref><br>{{flagcountry|Bosnia and Herzegovina}} 553,000 (2013) census<ref>[http://www.avaz.ba/vijesti/teme/u-bih-ima-484-posto-bosnjaka-327-posto-srba-i-14-6-posto-hrvata U BiH ima 48,4 posto Bošnjaka, 32,7 posto Srba i 14,6 posto Hrvata (Article on the preliminary report of 2013 census)]</ref> |

|||

| region1 = '''Europe''' |

|||

| pop1 = '''ca. 5.5 million''' |

|||

| ref1 = |

|||

| region2 = {{flagcountry|Germany}} |

|||

| pop2 = 227,510<ref name=destatis/> - 350,000 (est.) |

|||

| ref2 = <ref>[http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/en/hmiu/croatian-diaspora-in-federal-republic-of-germany/32 Croatian Diaspora in Federal Republic of Germany]</ref> |

|||

| region3 = {{flagcountry|Austria}} |

|||

| pop3 = 150,719 (2001) |

|||

| ref3 = <ref name=statistik.at/> |

|||

| region4 = {{flagcountry|Serbia}} |

|||

| pop4 = 57,900 (2011) |

|||

| ref4 = <ref name=SerbianCensus/> |

|||

| region5 = {{flagcountry|Switzerland}} |

|||

| pop5 = 40,484 (2006) |

|||

| ref5 = <ref name=admin.ch/> |

|||

| region6 = {{flagcountry|Slovenia}} |

|||

| pop6 = 35,642 (2002) |

|||

| ref6 = <ref name=stat.si/> |

|||

| region7 = {{flagcountry|Sweden}} |

|||

| pop7 = 35,000 (est.) |

|||

| ref7 = <ref>[http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/hr/hmiu/hrvatsko-iseljenistvo-u-svedskoj/36 Državni ured za Hrvate izvan Republike Hrvatske]</ref> |

|||

| region8 = {{flagcountry|France}} |

|||

| pop8 = 30,000 (est.) |

|||

| ref8 = <ref name="france embassy"/> |

|||

| region9 = {{flagcountry|Hungary}} |

|||

| pop9 = 23,561 |

|||

| ref9 = <ref name=nepszamlalas.hu/> |

|||

| region10 = {{flagcountry|Italy}} |

|||

| pop10 = 21,360 |

|||

| ref10 = <ref name=istat.it/> |

|||

| region11 = {{flagcountry|Netherlands}} |

|||

| pop11 = 10,000 |

|||

| ref11 = <ref>[http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/en/hmiu/croatian-diaspora-in-the-kingdom-of-the-netherlands/29 Croatian Diaspora in the Kingdom of the Netherlands]</ref> |

|||

| region12 = {{flagcountry|United Kingdom}} |

|||

| pop12 = 6,992 |

|||

| ref12 = <ref name=oecd.org/> |

|||

| region13 = {{flagcountry|Montenegro}} |

|||

| pop13 = 6,021 (2011) |

|||

| ref13 = <ref name=monstat.org/> |

|||

| region14 = {{flagcountry|Romania}} |

|||

| pop14 = 6,786 |

|||

| ref14 = <ref name=mimmc.ro/> |

|||

| region15 = {{flagcountry|Denmark}} |

|||

| pop15 = 5,400 |

|||

| ref15 = <ref name=joshuaproject.net/> |

|||

| region16 = {{flagcountry|Norway}} |

|||

| pop16 = 3,909 |

|||

| ref16 = <ref name="ssb.no">[http://www.ssb.no/innvbef_en/tab-2010-04-29-04-en.html Statistics Norway – Persons with immigrant background by immigration category and country background. 1 January 2010]</ref> |

|||

| region17 = {{flagcountry|Slovakia}} |

|||

| pop17 = 2,600 |

|||

| ref17 = <ref name="Glas Koncila"/> |

|||

| region18 = {{flagcountry|Czech Republic}} |

|||

| pop18 = 850–2000 |

|||

| ref18 = <ref>{{cite web|author=Joshua Project |url=http://www.joshuaproject.net/people-profile.php?peo3=11437&rog3=EZ |title=Croat of Czech Republic Ethnic People Profile |publisher=Joshuaproject.net |date= |accessdate=2013-03-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.croatianhistory.net/etf/cromor.html |title=Moravian Croats |publisher=Croatianhistory.net |date= |accessdate=2013-03-26}}</ref> |

|||

| region19 = '''North America''' |

|||

| pop19 = '''ca. 530,000 - 1.2 mil''' |

|||

| ref19 = |

|||

| region20 = {{flagcountry|USA}} |

|||

| pop20 = 414,714 (2012)<ref>[http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_12_1YR_B04003&prodType=table- Results ] American Fact Finder (US Census Bureau)</ref> - 1,200,000 (est.) |

|||

| ref20 = <ref>[http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/en/hmiu/croatian-diaspora-in-the-united-states-of-america/35 Croatian diaspora in the USA] ''It has been estimated that around 1.200.000 Croats and their descendants live in the USA.''</ref> |

|||

| region21 = {{flagcountry|Canada}} |

|||

| pop21 = 114,880 |

|||

| ref21 = <ref>[http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/dt-td/Rp-eng.cfm?LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=0&GK=0&GRP=1&PID=105396&PRID=0&PTYPE=105277&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2013&THEME=95&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF= 2011 National Household Survey: Data tables]</ref> |

|||

| region22 = '''South America''' |

|||

| pop22 = '''ca. 650,000''' |

|||

| ref22 = |

|||

| region23 = {{flagcountry|Argentina}} |

|||

| pop23 = 250,000 |

|||

| ref23 = <ref name="croata"/> |

|||

| region24 = {{flagcountry|Chile}} |

|||

| pop24 = 200,000<ref name="croata"/> - 380,000 |

|||

| ref24 = <ref>[http://hrvatskimigracije.es.tl/Diaspora-Croata.htm Diaspora Croata] ''El Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de la República de Chile evalúa que en ese país actualmente viven 380.000 personas consideradas de ser de descendencia croata, lo que es un 2,4% de la población total de Chile.''</ref> |

|||

| region25 = {{flagcountry|Brazil}} |

|||

| pop25 = 20,000 (est.) |

|||

| ref25 = <ref name="croata"/> |

|||

| region26 = {{flagcountry|Peru}} |

|||

| pop26 = 6,000 |

|||

| ref26 = <ref name="croata"/> |

|||

| region27 = {{flagcountry|Paraguay}} |

|||

| pop27 = 5,000 |

|||

| ref27 = <ref name="croata"/><ref>[http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/hr/hmiu/hrvatsko-iseljenistvo-u-ekvadoru/24 Državni ured za Hrvate izvan Republike Hrvatske]</ref> |

|||

| region28 = {{flagcountry|Ecuador}} |

|||

| pop28 = 4,000 |

|||

| ref28 = <ref>[http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/en/hmiu/croatian-diaspora-in-paraguay/33 Državni ured za Hrvate izvan Republike Hrvatske]</ref> |

|||

| region29 = '''Other''' |

|||

| pop29 = '''ca. 250,000''' |

|||

| ref29 = |

|||

| region30 = {{flagcountry|Australia}} |

|||

| pop30 = 126,264 (2011) |

|||

| ref30 = <ref name=abs.gov.au/> |

|||

| region31 = {{flagcountry|New Zealand}} |

|||

| pop31 = 2,550 (2006) - 60,000 (est.) |

|||

| ref31 = <ref>[http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/dalmatians/page-7 The Encyclopedia of New Zealand]</ref><ref>[http://www.hrvatiizvanrh.hr/hr/hmiu/hrvatsko-iseljenistvo-u-novom-zelandu/31 Državni ured za Hrvate izvan Republike Hrvatske]</ref> |

|||

| region32 = {{flagcountry|South Africa}} |

|||

| pop32 = 8,000 |

|||

| ref32 = <ref name=hic.hr/> |

|||

| langs = [[Croatian language|Croatian]] |

|||

| rels = Predominantly [[Roman Catholic]]. There is also a small community of ethnic Croats of Islamic faith<ref>"4. Population by ethnicity and religion". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-17.</ref> (see [[Croat Muslims]]) |

|||

| related = Other [[Slavs]], especially other [[South Slavs]]<br>{{small|[[Serbs]], [[Bosniaks]], [[Montenegrins (ethnic group)|Montenegrins]], [[Slovenes]] and [[Macedonians (ethnic group)|Macedonians]] are the most related}}<ref name=ethnologue.com/> |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Croats''' ({{IPAc-en|k|r|oʊ|æ|t|,_|k|r|oʊ|ɑː|t}}; {{lang-hr|Hrvati}}, {{IPA-sh|xřʋaːti|pron}}) are a [[nation]] and [[South Slavs|South Slavic]] [[ethnic group]] at the crossroads of [[Central Europe]], [[Southeast Europe]], and the [[Mediterranean]]. Croats mainly live in homeland [[Croatia]], [[Croats of Bosnia and Herzegovina|Bosnia and Herzegovina]] and nearby countries [[Serbia]] and [[Slovenia]]. Likewise, Croats are an officially recognized minority in [[Austria]], [[Czech Republic]], [[Hungary]], [[Italy]], [[Montenegro]], [[Romania]], [[Serbia]], and [[Slovakia]]. Responding to political, social and economic pressure, many Croats have migrated throughout the world, and established a notable [[Croatian diaspora]].<ref name=diasporas/><ref name="HWC"/> In Western Europe exist larger communities in [[Germany]], [[Austria]], [[Swizerland]], [[France]], and [[Italy]]. Outside Europe, there are even more significant Croatian communities in the [[United States]], [[Canada]], [[Chile]], [[Argentina]], and [[Australia]]. |

|||

The '''Croats''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|r|oʊ|æ|t|s}};<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.lexico.com/definition/Croat |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201202182900/https://www.lexico.com/definition/croat |archive-date=2 December 2020 |title=Croat |dictionary=[[Lexico]] UK English Dictionary |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]}}</ref> {{langx|hr|Hrvati}}, {{IPA|sh|xr̩ʋǎːti|pron}}) are a [[South Slavs|South Slavic]] [[ethnic group]] native to [[Croatia]], [[Bosnia and Herzegovina]] and other neighboring countries in [[Central Europe|Central]] and [[Southeastern Europe]] who share a common Croatian [[Cultural heritage|ancestry]], [[Culture of Croatia|culture]], [[History of Croatia|history]] and [[Croatian language|language]]. They also form a sizeable minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely [[Croats of Slovenia|Slovenia]], [[Burgenland Croats|Austria]], the [[Croats in the Czech Republic|Czech Republic]], [[Croats in Germany|Germany]], [[Croats of Hungary|Hungary]], [[Croats of Italy|Italy]], [[Croats of Montenegro|Montenegro]], [[Croats of Romania|Romania]], [[Croats of Serbia|Serbia]] and [[Croats in Slovakia|Slovakia]]. |

|||

Croats are noted for their cultural diversity, which has been influenced by a number of other neighboring cultures through the ages. The strongest influences came from [[Central Europe]] and the [[Mediterranean]] where, at the same time, Croats have made their own contribution. The Croats are predominantly [[Roman Catholicism|Roman Catholic]] by religion. The [[Croatian language]] is an official language in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and is a recognised minority language within Croatian autochthonous communities and minorities in Montenegro, Austria ([[Burgenland]]), Italy ([[Molise]]), Romania ([[Caraşova]], [[Lupac]]) and Serbia ([[Vojvodina]]). |

|||

Due to political, social and economic reasons, many Croats migrated to North and South America as well as New Zealand and later Australia, establishing a [[Croatian diaspora|diaspora]] in the aftermath of [[World War II]], with grassroots assistance from earlier communities and the Roman [[Catholic Church]].<ref name=diasporas/><ref name="HWC"/> In Croatia (the [[nation state]]), 3.9 million people identify themselves as Croats, and constitute about 90.4% of the population. Another 553,000 live in [[Croats of Bosnia and Herzegovina|Bosnia and Herzegovina]], where they are one of the three [[Constituent peoples of Bosnia and Herzegovina|constituent ethnic groups]], predominantly living in Western [[Herzegovina]], [[Central Bosnia]] and [[Bosnian Posavina]]. The minority in [[Serbia]] number about 70,000, mostly in [[Vojvodina]].<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1" /> The ethnic [[Tarara (Māori Croatian ethnic mix)|Tarara people]], indigenous to [[Northland Region|Te Tai Tokerau]] in New Zealand, are of mixed Croatian and [[Māori people|Māori]] (predominantly [[Ngāpuhi]]) descent. [[Tarara Day]] is celebrated every 15 March to commemorate their "highly regarded place in present-day [[Māori culture|Māoridom]]".<ref>{{Cite web |title=Croatian :: Ngati Tarara 'The Olive and Kauri' |url=http://www.croatianclub.org/history/ngati-tarara/ |access-date=2022-11-29 |website=croatianclub.org |archive-date=29 November 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221129045553/http://www.croatianclub.org/history/ngati-tarara/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last1=Kapiteli |first1=Marija |last2=Taonga |first2=New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu |title=Tarara Day |url=https://teara.govt.nz/en/photograph/30253/tarara-day |access-date=2022-11-29 |website=teara.govt.nz |language=en |archive-date=29 November 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221129045549/https://teara.govt.nz/en/photograph/30253/tarara-day |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

Croats are mostly [[Catholic]]s. The [[Croatian language]] is official in [[Croatia]], the [[European Union]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-13-825_en.htm|title=European Commission – Frequently asked questions on languages in Europe|website=europa.eu|access-date=6 August 2019|archive-date=16 December 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201216210501/https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_13_825|url-status=live}}</ref> and [[Bosnia and Herzegovina]].<ref>{{cite web |title=About BiH |url=http://www.bhas.ba/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=52&itemid=80&lang=en&Itemid= |website=Bhas.ba |publisher=Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina |access-date=7 August 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120711122914/http://www.bhas.ba/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=52&itemid=80&lang=en&Itemid= |archive-date=11 July 2012 }}</ref> Croatian is a recognized [[minority language]] within Croatian autochthonous communities and minorities in Montenegro, Austria ([[Burgenland]]), Italy ([[Molise]]), Romania ([[Carașova]], [[Lupac]]) and Serbia ([[Vojvodina]]). |

|||

== Etymology == |

|||

{{main|Names of the Croats and Croatia}} |

|||

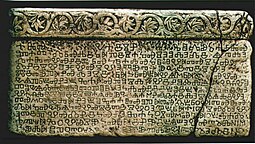

The foreign [[ethnonym]] variation "Croats" of the [[Names of the Croats and Croatia|native name]] "Hrvati" derives from [[Medieval Latin]] {{lang|la-x-medieval|Croāt}}, itself a derivation of [[West Slavic languages|North-West Slavic]] {{lang|zlw|*Xərwate}}, by [[Slavic liquid metathesis and pleophony|liquid metathesis]] from Common Slavic period ''*Xorvat'', from proposed [[Proto-Slavic language|Proto-Slavic]] ''[[wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Slavic/xъrvatъ|*Xъrvátъ]]'' which possibly comes from the 3rd-century [[Scythian languages|Scytho-Sarmatian]] form attested in the [[Tanais Tablets]] as {{lang|grc|Χοροάθος|italic=no}} (''{{lang|grc-latn|Khoroáthos}}'', alternate forms comprise {{Lang|grc-latn|Khoróatos}} and ''{{lang|grc-latn|Khoroúathos}}'').<ref name="Gluhak-1993">{{cite book|first=Alemko|last=Gluhak|title=Hrvatski etimološki rječnik|trans-title=Croatian Etymological Dictionary|language=hr|publisher=August Cesarec|year=1993|isbn=953-162-000-8}}</ref> The origin of the ethnonym is uncertain, but most probably is from [[Ossetian language|Proto-Ossetian]] / [[Scythian languages#Alanian|Alanian]] *''xurvæt-'' or *''xurvāt-'', in the meaning of "one who guards" ("guardian, protector").<ref>{{citation |first=Ranko |last=Matasović |author-link=Ranko Matasović |title=Ime Hrvata |trans-title=The Name of Croats |journal=Jezik (Croatian Philological Society) |location=Zagreb |year=2019 |volume=66 |issue=3 |pages=81–97 |url=https://hrcak.srce.hr/228825?lang=en |language=hr |access-date=4 April 2023 |archive-date=12 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221212011805/https://hrcak.srce.hr/228825?lang=en |url-status=live }}</ref> The earliest preserved mentions of the ethnonym in stone inscriptions and written documents in the territory of Croatia are dated to the 8th-9th century (e.g. ''Dux Croatorum'' on [[Branimir inscription]] and ''Dux Chroatorum'' on [[Charter of Duke Trpimir]]),<ref>{{cite journal |title=Kulturna kronika: Dvanaest hrvatskih stoljeća |url=http://www.matica.hr/vijenac/291/hrvatski-nacionalni-dan-na-expou-u-japanu-9037/ |journal=[[Vijenac]] |publisher=[[Matica hrvatska]] |location=Zagreb |issue=291 |date=28 April 2005 |access-date=10 June 2019 |language=hr}}</ref> while in native Croatian language the earliest writing is from the [[Baška tablet]] (c. 1100), which in [[Glagolitic script]] reads: ''zvъnъmirъ kralъ xrъvatъskъ'' ("Zvonimir, king of Croats").<ref name="Fučić-1971">{{cite journal |url=http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=21348 |first=Branko | last = Fučić | author-link = Branko Fučić |title=Najstariji hrvatski glagoljski natpisi |trans-title=The Oldest Croatian Glagolitic Inscriptions |journal=[[Slovo (journal)|Slovo]] |publisher=[[Old Church Slavonic Institute]] |volume=21 |date=September 1971 |language=hr |pages=227–254 |access-date=14 October 2011}}</ref> |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

{{Further|History of Croatia}} |

{{Further|History of Croatia}} |

||

=== |

===Arrival of the Slavs=== |

||

{{main| |

{{main|Origin hypotheses of the Croats|White Croatia|White Croats|Slavic migrations to Southeastern Europe}} |

||

[[File:Oton Ivekovic, Dolazak Hrvata na Jadran.jpg|thumb|250px|right|''The Coming of the Croats to the Adriatic'' by [[Oton Iveković]].]] |

|||

[[Early Slavs]], especially [[Sclaveni]] and [[Antae]], including the [[White Croats]], invaded and settled [[Southeastern Europe]] in the 6th and 7th century.{{sfn|Fine|1991|pp=26–41}} |

|||

====The "Dark Ages"==== |

|||

====Early medieval archaeology==== |

|||

Evidence is rather scarce for the period between the 7th and 8th centuries, CE. Archaeological evidence shows population continuity in coastal Dalmatia and Istria. In contrast, much of the Dinaric hinterland appears to have been depopulated, as virtually all hilltop settlements, from Noricum to Dardania, were abandoned (only few appear destroyed) in the early 7th century. Although the dating of the earliest Slavic settlements is still disputed, there is a hiatus of almost a century. The origin, timing and nature the Slavic migrations remains controversial, however, all available evidence points to the nearby Danubian and Carpathian regions rather than some distant "[[White Croatia|White Croat]]" homeland in Poland or Ukraine.<ref>{{Harvard citation text|Curta|2010|p=323 "If anything, the reconsideration of the problem in the light of the ''Making of the Slavs'' strongly suggests that the Slavs did not have to migrate from some distant Urheimat in order to become Slovenians and Croats."}}</ref> |

|||

Archaeological evidence shows population continuity in coastal [[Dalmatia]] and [[Istria]]. In contrast, much of the [[Dinaric Alps|Dinaric]] hinterland and appears to have been depopulated, as virtually all hilltop settlements, from [[Noricum]] to [[Dardania (Roman province)|Dardania]], were abandoned and few appear destroyed in the early 7th century. Although the dating of the earliest Slavic settlements was disputed, recent archaeological data established that the migration and settlement of the Slavs/Croats have been in late 6th and early 7th century.<ref name="Belos00">{{cite journal |last1=Belošević |first1=Janko |date=2000 |title=Razvoj i osnovne značajke starohrvatskih grobalja horizonta 7.-9. stoljeća na povijesnim prostorima Hrvata |url=https://morepress.unizd.hr/journals/index.php/pov/article/view/2231 |language=hr |journal=Radovi |volume=39 |issue=26 |pages=71–97 |doi=10.15291/radovipov.2231 |doi-access=free |access-date=3 July 2022 |archive-date=26 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230326033632/https://morepress.unizd.hr/journals/index.php/pov/article/view/2231 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Fabijanić |first=Tomislav |date=2013 |chapter=14C date from early Christian basilica gemina in Podvršje (Croatia) in the context of Slavic settlement on the eastern Adriatic coast |title=The early Slavic settlement of Central Europe in the light of new dating evidence |location=Wroclaw |publisher=Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology of the Polish Academy of Sciences |pages=251–260 |isbn=978-83-63760-10-6}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Bekić |first1=Luka |date=2012 |chapter=Keramika praškog tipa u Hrvatskoj |title=Dani Stjepana Gunjače 2, Zbornik radova sa Znanstvenog skupa "Dani Sjepana Gunjače 2": Hrvatska srednjovjekovna povijesno-arheološka baština, Međunarodne teme |chapter-url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348572968 |location=Split |publisher=Muzej hrvatskih arheoloških spomenika |pages=21–35 |isbn=978-953-6803-36-1}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Bekić |first1=Luka |date=2016 |title=Rani srednji vijek između Panonije i Jadrana: ranoslavenski keramički i ostali arheološki nalazi od 6. do 8. stoljeća |trans-title=Early medieval between Pannonia and the Adriatic: early Slavic ceramic and other archaeological finds from the sixth to eighth century |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348500715 |location=Pula |publisher=Arheološki muzej Istre |language=hr, en |pages=101, 119, 123, 138–140, 157–162, 173–174, 177–179 |isbn=978-953-8082-01-6}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Bilogrivić |first1=Goran |date=2018 |title=Urne, Slaveni i Hrvati. O paljevinskim grobovima i doseobi u 7. stoljeću |url=https://hrcak.srce.hr/220231 |language=hr |journal=Zb. Odsjeka povij. Znan. Zavoda povij. Druš. Znan. Hrvat. Akad. Znan. Umjet. |volume=36 |pages=1–17 |doi=10.21857/ydkx2crd19 |s2cid=189548041 |access-date=3 July 2022 |archive-date=12 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221212004535/https://hrcak.srce.hr/220231 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

====Croat ethnogenesis==== |

====Croat ethnogenesis==== |

||

[[File:Distribution of Croatian ethnonym in the Middle Ages.jpg|thumb|255px|left|The range of Slavic ceramics of the [[Penkovka culture|Prague-Penkovka culture]] marked in black, all known ethnonyms of Croats are within this area. Presumable migration routes of Croats are indicated by arrows, per V.V. Sedov (1979).]] |

|||

Much uncertainty revolves around the exact circumstances of their appearance given the scarcity of literary sources during the 7th and 8th century [[Middle Ages]]. Traditionally, scholarship has placed the arrival of the [[White Croats]] from [[White Croatia|Great/White Croatia]] in Eastern Europe in the early 7th century, primarily on the basis of the later [[Byzantine]] document ''[[De Administrando Imperio]]''. As such, the arrival of the Croats was seen as part of main wave or a second wave of Slavic migrations, which took over Dalmatia from [[Avar Khaganate|Avar hegemony]]. However, as early as the 1970s, scholars questioned the reliability of [[Constantine VII|Porphyrogenitus]]' work, written as it was in the 10th century. Rather than being an accurate historical account, ''De Administrando Imperio'' more accurately reflects the political situation during the 10th century. It mainly served as Byzantine propaganda praising Emperor [[Heraclius]] for repopulating the [[Balkans]] (previously devastated by the [[Pannonian Avars|Avars]], [[Sclaveni]] and [[Antes (people)|Antes]]) with Croats, who were seen by the Byzantines as tributary peoples living on what had always been 'Roman land'.<ref>{{Harvard citation text|Curta|2006|p=138}}</ref> |

|||

Scholars have hypothesized the name Croat (''Hrvat'') may be [[Iranian languages|Iranian]], thus suggesting that the Croatians were possibly a [[Sarmatians|Sarmatian]] tribe from the [[Pontus (region)|Pontic]] region who were part of a larger movement at the same time that the Slavs were moving toward the [[Adriatic Sea|Adriatic]]. The major basis for this connection was the perceived similarity between ''Hrvat'' and [[Tanais Tablets|inscriptions]] from the [[Tanais]] dated to the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, mentioning the name {{transliteration|grc|Khoro(u)athos}}. Similar arguments have been made for an alleged [[Goths|Gothic]]-Croat link. Whilst there is possible evidence of population continuity between Gothic and Croatian times in parts of Dalmatia, the idea of a Gothic origin of Croats was more rooted in 20th century [[Ustaše]] political aspirations than historical reality.<ref>{{harvtxt|Dzino|2010|p=20}}</ref> |

|||

The ethonym "Croat" is first attested during the 9th century CE,<ref name="harvtxt|Dzino|2010|p=175">{{harvtxt|Dzino|2010|p=175}}</ref> in the charter of Duke Trpimir; and indeed begins to be widely attested throughout central and eastern Europe during the 9th and 10th centuries.<ref>{{Harvard citation text|Borri|2011|p=215}}</ref> Much uncertainty revolves around the exact circumstances of their appearance given the scarcity of literary sources during the 7th and 8th century "Dark Ages". |

|||

====Other polities in Dalmatia and Pannonia==== |

|||

Traditionally, scholarship has placed the arrival of the Croats in the 7th century, primarily on the basis of the ''De Administrando Imperio''. As such, the arrival of the Croats was seen as a second wave of Slavic migrations, which liberated Dalmatia from Avar hegemony. However, as early as the 1970s, scholars questioned the reliability of Porphyrogenitus' work, written as it was in the 10th century.<ref name=autogenerated1>{{harvxtxt|Dzino|2010|p=175}}</ref> Rather than being an accurate historical account, the DAI more accurately reflects the political situation during the 10th century. It mainly served as Byzantine propaganda praising Emperor Heraclius for repopulating the Balkans (previously devastated by the Avars) with Croats (and Serbs), who were seen by the Byzantines as tributary peoples living on what had always been 'Roman land'.<ref>{{Harvard citation text|Curta|2006|p=138}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Oton Ivekovic, Dolazak Hrvata na Jadran.jpg|thumb|right|255px|Arrival of the Croats to the [[Adriatic Sea]] by [[Oton Iveković]]]] |

|||

Other, distinct polities and ethno-political groups existed around the Croat duchy. These included the [[Guduscani|Guduscans]] (based in Liburnia), [[Pagania]] (between the Cetina and [[Neretva]] River), [[Zachlumia]] (between Neretva and [[Dubrovnik]]), [[Bosnia (early medieval)|Bosnia]], and [[Principality of Serbia (early medieval)|Serbia]] in other eastern parts of ex-Roman province of "Dalmatia".<ref>{{cite book |last=Budak |first=Neven |author-link=Neven Budak |date=2008 |chapter=Identities in Early Medieval Dalmatia (7th – 11th c.) |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4dUWAQAAIAAJ |title=Franks, Northmen and Slavs: Identities and State Formation in Early Medieval Europe |editor=Ildar H. Garipzanov |editor2=[[Patrick J. Geary]] |editor3=[[Przemysław Urbańczyk]] |location=Turnhout |publisher=Brepols |pages=223–241 |isbn=9782503526157 |access-date=13 July 2022 |archive-date=10 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230810101105/https://books.google.com/books?id=4dUWAQAAIAAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> Also prominent in the territory of future Croatia was the polity of Prince [[Ljudevit (Lower Pannonia)|Ljudevit]] who ruled the territories between the [[Drava]] and [[Sava]] rivers ("[[Slavs in Lower Pannonia|Pannonia Inferior]]"), centred from his fort at [[Sisak]]. Although Duke Liutevid and his people are commonly seen as a "Pannonian Croats", he is, due to the lack of "evidence that they had a sense of Croat identity" referred to as ''dux Pannoniae Inferioris'', or simply a Slav, by contemporary sources.<ref>{{harvtxt|Dzino|2010|p=186}}</ref><ref>{{harvtxt|Wolfram|2002}} Liudewit is considered the first Croatian prince. Constantine Porphyrogenitus has Dalmatia and parts of Slavonia populated by Croatians. But this author wrote more than a hundred years after the Frankish Royal annals which never mention the name of the Croatians although a great many Slavic tribal names are mentioned in the text. Therefore, if one applies the methods of an ethnogenetic interpretation, the Croatian Liudewit seems to be an anachronism.</ref> A closer reading of the ''DAI'' suggests that Constantine VII's consideration about the ethnic origin and identity of the population of Lower Pannonia, [[Pagania]], [[Zachlumia]] and other principalities is based on tenth century political rule and does not indicate ethnicity,<ref>{{cite book|author1=Dvornik, F.|author2=Jenkins, R. J. H.|author3=Lewis, B.|author4=Moravcsik, Gy.|author5=Obolensky, D.|author6=Runciman, S.|editor=P. J. H. Jenkins|title=De Administrando Imperio: Volume II. Commentary|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DWVxvgAACAAJ|year=1962|publisher=University of London: The Athlone Press|pages=139, 142|ref={{harvid|Dvornik|1962}}|access-date=13 July 2022|archive-date=27 September 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230927201655/https://books.google.com/books?id=DWVxvgAACAAJ|url-status=live}}</ref>{{sfn|Curta|2006|p=210}}<ref name="Budak1994">{{Cite book|last=Budak|first=Neven|author-link=Neven Budak|title=Prva stoljeća Hrvatske|year=1994|location=Zagreb|publisher=Hrvatska sveučilišna naklada|url=http://inet1.ffst.hr/_download/repository/Budak_1994.pdf|pages=58–61|isbn=953-169-032-4|access-date=13 July 2022|archive-date=4 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190504192532/http://inet1.ffst.hr/_download/repository/Budak_1994.pdf}}</ref><ref name="Gracanin2008">{{citation |last=Gračanin |first=Hrvoje |date=2008 |title=Od Hrvata pak koji su stigli u Dalmaciju odvojio se jedan dio i zavladao Ilirikom i Panonijom: Razmatranja uz DAI c. 30, 75-78 |url=https://hrcak.srce.hr/36767?lang=hr |journal=Povijest U Nastavi |volume=VI |issue=11 |pages=67–76 |language=hr |access-date=13 July 2022 |archive-date=19 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221219202016/https://hrcak.srce.hr/36767?lang=hr |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Harvard citation text|Budak|2018|pp=51, 111, 177, 181–182}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Živković|first=Tibor|author-link=Tibor Živković|title=Portreti srpskih vladara (IX—XII vek)|year=2006|publisher=Zavod za udžbenike|location=Belgrade|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=d-KTAAAACAAJ|isbn=86-17-13754-1|pages=60–61}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Živković|first=Tibor|year=2012|title=Неретљани – пример разматрања идентитета у раном средњем веку|trans-title=Arentani – an Example of Identity Examination in the Early Middle Ages|journal=Istorijski časopis|volume=61|pages=12–13}}</ref> and although both Croats and Serbs could have been a small military elite which managed to organize other already settled and more numerous Slavs,{{sfn|Dvornik|1962|p=139, 142}}{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=37, 57}}<ref>{{cite book|last=Heather|first=Peter|author-link=Peter Heather|title=Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Y5poAgAAQBAJ|year=2010|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-974163-2|pages=404–408, 424–425, 444}}</ref> it is possible that Narentines, Zachlumians and others also arrived as Croats or with Croatian tribal alliance.{{sfn|Dvornik|1962|p=138–139|ps=:Even if we reject Gruber's theory, supported by Manojlović (ibid., XLIX), that Zachlumje actually became a part of Croatia, it should be emphasized that the Zachlumians had a closer bond of interest with the Croats than with the Serbs, since they seem to have migrated to their new home not, as C. says (33/8-9), with the Serbs, but with the Croats; see below, on 33/18-19 ... This emendation throws new light on the origin of the Zachlumian dynasty and of the Zachlumi themselves. C.'s informant derived what he says about the country of Michael's ancestors from a native source, probably from a member of the prince's family; and the information is reliable. If this is so, we must regard the dynasty of Zachlumje and at any rate part of its people as neither Croat nor Serb. It seems more probable that Michael's ancestor, together with his tribe, joined the Croats when they moved south; and settled on the Adriatic coast and the Narenta, leaving the Croats to push on into Dalmatia proper. It is true that our text says that the Zachlumi 'have been Serbs since the time of that prince who claimed the protection of the emperor Heraclius' (33/9-10); but it does not say that Michael's family were Serbs, only that they 'came from the unbaptized who dwell on the river Visla, and are called (reading Litziki) "Poles'". Michael's own hostility to Serbia (cf. 32/86-90) suggests that his family was in fact not Serb; and that the Serbs had direct control only over Trebinje (see on 32/30). C.'s general claim that the Zachlumians were Serbs is, therefore, inaccurate; and indeed his later statements that the Terbouniotes (34/4—5), and even the Narentans (36/5-7), were Serbs and came with the Serbs, seem to conflict with what he has said earlier (32/18-20) on the Serb migration, which reached the new Serbia from the direction of Belgrade. He probably saw that in his time all these tribes were in the Serb sphere of influence, and therefore called them Serbs, thus ante-dating by three centuries the state of affairs in his own day. But in fact, as has been shown in the case of the Zachlumians, these tribes were not properly speaking Serbs, and seem to have migrated not with the Serbs but with the Croats. The Serbs at an early date succeeded in extending their sovereignty over the Terbouniotes and, under prince Peter, for a short time over the Narentans (see on 32/67). The Diocleans, whom C. does not claim as Serbs, were too near to the Byzantine thema of Dyrrhachion for the Serbs to attempt their subjugation before C.'s time}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Dvornik |first=Francis |author-link=Francis Dvornik |date=1970 |title=Byzantine Missions Among the Slavs: SS. Constantine-Cyril and Methodius |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OwHZAAAAMAAJ |location=New Brunswick, New Jersey |publisher=Rutgers University Press |page=26 |isbn=9780813506135 |quote=Constantine regards all Slavic tribes in ancient Praevalis and Epirus—the Zachlumians, Tribunians, Diodetians, Narentans— as Serbs. This is not exact. Even these tribes were liberated from the Avars by the Croats who lived among them. Only later, thanks to the expansion of the Serbs, did they recognize their supremacy and come to be called Serbians. |access-date=21 July 2022 |archive-date=27 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230927201657/https://books.google.com/books?id=OwHZAAAAMAAJ |url-status=live }}</ref>{{sfn|Živković|2006|pp=60–61|ps=:Constantine Porphyrogenitus explicitly calls the inhabitants of Zahumlje Serbs who have settled there since the time of Emperor Heraclius, but we cannot be certain that the Travunians, Zachlumians and Narentines in the migration period to the Balkans really were Serbs or Croats or Slavic tribes which in alliance with Serbs or Croats arrived in the Balkans}} |

|||

The Croats became the dominant local power in northern Dalmatia, absorbing Liburnia and expanding their name by conquest and prestige. In the south, while having periods of independence, the Naretines merged with Croats later under control of Croatian Kings.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|url=http://enciklopedija.lzmk.hr/clanak.aspx?id=27481|title=Neretljani|encyclopedia=Hrvatski obiteljski leksikon|language=hr|access-date=12 December 2017|archive-date=13 December 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171213011404/http://enciklopedija.lzmk.hr/clanak.aspx?id=27481|url-status=live}}</ref> With such expansion, Croatia became the dominant power and absorbed other polities between Frankish, [[First Bulgarian Empire|Bulgarian]] and Byzantine empire. Although the [[Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja]] has been dismissed as an unreliable record, the mentioned "Red Croatia" suggests that Croatian clans and families might have settled as far south as [[Duklja]]/[[Zeta (crown land)|Zeta]].<ref>{{Harvard citation text|Fine|2005|p=6203}}</ref> According to Martin Dimnik writing for ''[[The New Cambridge Medieval History]]'', "at the beginning of the eleventh century the Croats lived in two more or less clearly defined regions" of the "Croatian lands" which "were now divided into three districts" including Slavonia/Pannonian Croatia (between rivers Sava and Drava) on one side and Croatia/Dalmatian littoral (between [[Gulf of Kvarner]] and rivers Vrbas and Neretva) and Bosnia (around [[Bosna (river)|river Bosna]]) on other side, and that "Croats, along with Serbs, also lived in Bosnia which at times came under the control of Croatian kings".<ref name="TNCMH" />{{rp|266–276}} |

|||

Scholars have often hypothesized the name Croat (''Hrvat'') to be Iranian, thus suggesting that the Croats were actually a Sarmatian tribe from the Pontic region who were part of a larger movement of Slavs toward the Adriatic. The major basis for this connection was the perceived similarity between Croat and inscriptions from the Tanais dated to the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, mentioning the name ''Horo(u)athos''. However, "it is difficult, if not impossible to connect these names".{{Contradict-inline|article=Name of Croatia|date=March 2014}}<!-- see especially [[:de:Kroaten#Namensherkunft]] --> Whether one accepts the etymological connection or not, anthropological theories suggest that ethnic groups are not static, ancient nations but are perpetually changing. This "seriously undermines any notion of an 'Iranian component' in the construction of early medieval Croat identity."<ref>{{harvtxt|Dzino|2010|p=21}}</ref>{{Clarify|reason=Non sequitur. In fact, the opposite conclusion would make more sense.|date=March 2014}}<!-- Why does the dynamic nature of ethnic groups affect negatively, if not outright preclude, the possibility that an Iranian component was absorbed in the early Croat ethnos, or somehow took part in the Croat ethnogenesis (probably along with other groups, such as Romance, Germanic and perhaps ancient Balkanic and Greek)? Quite the opposite, such admixture and absorption, partially changing an Iranian for a new Slavic identity, while keeping the name, would be a prime example for exactly this dynamic nature of ethnic groups. --> Similar arguments have been made for an alleged Gothic-Croat link. Whilst there is indeed evidence of population continuity between Gothic and Croat times in parts of Dalmatia, the idea of a Gothic origin of Croats was more rooted in the political aspirations of the [[Ustase|Croatian NDH party]] than historical reality.<ref>{{harvtxt|Dzino|2010|p=20}}</ref> |

|||

===Early medieval age=== |

|||

Contemporary scholarship views the rise of "Croats" as a local, Dalmatian response to the demise of the Avar khanate and the encroachment of Frankish and Byzantine Empires into northern Dalmatia.<ref>{{Harvard citation text|Ancic|1996}}</ref> They appear to have been based around Nin and Klis, down to the Cetina and south of Liburnia. Here, concentrations of the "Old Croat culture" abound, marked by some very wealthy warrior burials dating to the 9th century CE.<ref>{{Harvard citation text|Curta|2006|pp=141–42}}</ref> |

|||

{{main|Duchy of Croatia|Principality of Lower Pannonia}} |

|||

The lands which constitute modern Croatia fell under three major geographic-politic zones during the Middle Ages, which were influenced by powerful neighbor Empires – notably the Byzantines, the Avars and later [[Hungarians|Magyars]], [[Franks]] and [[Bulgars]]. Each vied for control of the Northwest Balkan regions. Two independent Slavic dukedoms emerged sometime during the 9th century: the [[Duchy of Croatia]] and [[Principality of Lower Pannonia]]. |

|||

====Pannonian Principality ("Savia")==== |

|||

====Other Polities in Dalmatia and Pannonia==== |

|||

{{more citations needed section|date=November 2015}} |

|||

Having been under Avar control, lower Pannonia became a march of the [[Carolingian Empire]] around 800. Aided by [[Vojnomir of Pannonian Croatia|Vojnomir]] in 796, the first named Slavic Duke of Pannonia, the Franks wrested control of the region from the Avars before totally destroying the Avar realm in 803. After the death of [[Charlemagne]] in 814, Frankish influence decreased on the region, allowing Prince [[Ljudevit Posavski]] to raise a rebellion in 819.<ref name="Wolfram 2002">{{Harvard citation text|Wolfram|2002}}</ref> The [[Frankish Empire|Frankish]] [[margrave]]s sent armies in 820, 821 and 822, but each time they failed to crush the rebels.<ref name="Wolfram 2002"/> Aided by Borna the Guduscan, the Franks eventually defeated Ljudevit, who withdrew his forces to the Serbs and conquered them, according to the Frankish Annals.{{citation needed|date=November 2015}} |

|||

For much of the subsequent period, Savia was probably directly ruled by the Carinthian [[Arnulf of Carinthia|Duke Arnulf]], the future East Frankish King and Emperor. However, Frankish control was far from smooth. The [[Royal Frankish Annals]] mention several Bulgar raids, driving up the Sava and Drava rivers, as a result of a border dispute with the Franks, from 827. By a peace treaty in 845, the Franks were confirmed as rulers over [[Slavonia]], whilst [[Syrmia|Srijem]] remained under Bulgarian clientage. Later, the expanding power of [[Great Moravia]] also threatened Frankish control of the region. In an effort to halt their influence, the Franks sought alliance with the Magyars, and elevated the local Slavic leader [[Braslav of Croatia|Braslav]] in 892, as a more independent Duke over lower Pannonia.{{citation needed|date=November 2015}} |

|||

Other, distinct polities also existed near the Croat duchy. These included the Guduscans (based in Liburnia), the Narentines (around the Cetina and Neretva) and the Sorabi (Serbs) who ruled some other parts of "Dalmatia".<ref>{{Harvard citation text|Budak|2008|p=223}}</ref> Also prominent in the territory of future Croatia was the polity of Prince Liutevid, who ruled the territories between the Drava and Sava ("Pannonia Inferior"), centred from his fort at Sisak. Although Duke Liutevid and his people are commonly seen as a "Pannonian Croats", "there is no evidence that they had a sense of Croat identity". Rather, he is referred to as ''dux Pannoniae Inferioris'', or simply a Slav, by contemporary sources.<ref>{{harvtxt|Dzino|2010|p=186}}</ref><ref>{{harvtxt|Wolfram|2002}} Liudewit is usually considered the first Croatian prince we know of. To be true, there is no doubt that Constantine Porphyrogenitus has Dalmatia and parts of Slavonia populated by Croatians. But this author wrote more than a hundred years after the Frankish Royal annals which never mention the name of the Croatians although you will find a great many Slavic tribal names there. Therefore, if one applies the methods of an ethnogenetic interpretation, the Croatian Liudewit seems to be an anachronism.</ref> However, soon, the Croats became the dominant local power in northern Dalmatia, absorbing Liburnia and expanding their name by conquest and prestige. Whilst always remaining independent, the Naretines at times came under the sway of later Croatian Kings. |

|||

In 896, his rule stretched from [[Vienna]] and [[Budapest]] to the southern Croat duchies, and included almost the whole of ex-Roman Pannonian provinces. He probably died {{circa}} 900 fighting against his former allies, the Magyars.<ref name="Wolfram 2002"/> The subsequent history of Savia again becomes murky, and historians are not sure who controlled Savia during much of the 10th century. However, it is likely that the ruler [[Tomislav of Croatia|Tomislav]], the first crowned King, was able to exert much control over Savia and adjacent areas during his reign. It is at this time that sources first refer to a "Pannonian Croatia", appearing in the 10th century Byzantine work ''De Administrando Imperio''.<ref name="Wolfram 2002"/> |

|||

Although the Chronicle of the Priest Duklja has been dismissed as an unreliable record, the mentioned "Red Croatia" suggests that Croatian clans and families might have settled as far south as [[Duklja]]/ Zeta.<ref>{{Harvard citation text|Fine|2005|p=6203}}</ref> |

|||

=== |

===Dalmatian Croats=== |

||

The [[Dalmatian Croat]]s were recorded to have been subject to the Kingdom of Italy under [[Lothair I]], since 828. The Croatian Prince [[Mislav of Croatia|Mislav]] (835–845) built up a formidable navy, and in 839 signed a peace treaty with [[Pietro Tradonico]], [[doge of Venice]]. The Venetians soon proceeded to battle with the independent Slavic pirates of the [[Pagania]] region, but failed to defeat them. The Bulgarian king [[Boris I of Bulgaria|Boris I]] (called by the [[Byzantine Empire]] Archont of Bulgaria after he made Christianity the official religion of Bulgaria) also waged a lengthy war against the Dalmatian Croats, trying to expand his state to the [[Adriatic]].{{citation needed|date=November 2015}} |

|||

{{Croats}} |

|||

{{main|Duchy of Croatia|Principality of Pannonian Croatia}} |

|||

The Croatian Prince [[Trpimir I of Croatia|Trpimir I]] (845–864) succeeded Mislav. In 854, there was a great battle between Trpimir's forces and the Bulgars. Neither side emerged victorious, and the outcome was the exchange of gifts and the establishment of peace. Trpimir I managed to consolidate power over Dalmatia and much of the inland regions towards [[Pannonia]], while instituting counties as a way of controlling his subordinates (an idea he picked up from the Franks). The first known written mention of the Croats, dates from 4 March 852, in [[statute]] by Trpimir. Trpimir is remembered as the initiator of the [[Trpimirović dynasty]], that ruled in Croatia, with interruptions, from 845 until 1091. After his death, an uprising was raised by a powerful nobleman from [[Knin]] – [[Domagoj of Croatia|Domagoj]], and his son [[Zdeslav of Croatia|Zdeslav]] was exiled with his brothers, Petar and [[Muncimir of Croatia|Muncimir]] to [[Constantinople]].{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=257}} |

|||

The lands which constitute modern Croatia fell under 3 major geographic-politic zones during the Middle Ages, which were influenced by powerful neighbour Empires - notably the Byzantines, the Avars and later Magyars, Franiks and Bulgars. Each vied for control of the Northwest Balkan regions. Nevertheless, two independent Slavic dukedoms emerged sometime during the 9th century: the [[Principality of Dalmatian Croatia|Croat Duchy]] and [[Pannonian Croatia|Principality of Lower Pannonia]]. |

|||

Facing a number of naval threats by [[Saracens]] and Byzantine Empire, the Croatian Prince Domagoj (864–876) built up the Croatian navy again and helped the coalition of emperor [[Louis II, Holy Roman Emperor|Louis II]] and the Byzantine to [[Louis II's campaign against Bari (866–871)|conquer Bari]] in 871. During Domagoj's reign [[piracy]] was a common practice, and he forced the Venetians to start paying tribute for sailing near the eastern Adriatic coast. After Domagoj's death, Venetian chronicles named him "The worst duke of Slavs", while [[Pope John VIII]] referred to Domagoj in letters as "Famous duke". Domagoj's son, of unknown name, ruled shortly between 876 and 878 with his brothers. They continued the rebellion, attacked the western Istrian towns in 876, but were subsequently defeated by the Venetian navy. Their ground forces defeated the Pannonian duke [[Kocelj]] (861–874) who was suzerain to the Franks, and thereby shed the Frankish vassal status. Wars of Domagoj and his son liberated Dalmatian Croats from supreme Franks rule. Zdeslav deposed him in 878 with the help of the Byzantines. He acknowledged the supreme rule of [[Byzantine Emperor]] [[Basil I]]. In 879, the [[Pope]] asked for help from prince Zdeslav for an armed escort for his delegates across southern Dalmatia and [[Zahumlje]],{{citation needed|date=October 2021}} but on early May 879, Zdeslav was killed near Knin in an uprising led by [[Branimir of Croatia|Branimir]], a relative of Domagoj, instigated by the Pope, fearing Byzantine power.{{citation needed|date=November 2015}} |

|||

;Pannonian Principality ("Savia") |

|||

Having been under Avar control, lower Pannonia became a march of the [[Carolingian Empire]] around 800. Aided by [[Vojnomir of Pannonian Croatia|Vojnomir]] in 796, the first named Slavic Duke of Pannonia, the Franks wrested control of the region from the Avars before totally destroying the Avar realm, 803. After the death of [[Charlemagne]] in 814, Frankish influence decreased on the region, allowing Prince [[Ljudevit Posavski]] to raise a rebellion in 819.<ref name="Wolfram 2002">{{Harvard citation text|Wolfram|2002}}</ref> The [[Franks|Frankish]] [[Margraves]] sent armies in 820, 821 and 822, but each time they failed to crush the rebels.<ref name="Wolfram 2002"/> Aided by Borna the Guduscan, the Franks eventually defeated Ljudevit, who withdrew his forces to the "Serbs", according to the Frankish Annals (historians debate what the Frankish sources exactly meant by 'Srb', and where this place or people were). For much of the subsequent period, Savia was probably directly ruled by the Carinthian [[Arnulf of Carinthia|Duke Arnulf]], the future East Frankish King and Emperor. However, Frankish control was far from smooth. The [[Royal Frankish Annals]] mention several Bulgar raids, driving up the Sava and Drava rivers, as a result of a border dispute with the Franks, from 827. By a peace treaty in 845, the Franks were confirmed as rulers over Slavonia, whilst Srijem remained under Bulgarian clientage. Later, the expanding power of [[Great Moravia]] also threatened Frankish control of the region. IN an effort to halt their influence, the Franks sought alliance with the Magyars, and elevated the local Slavic leader [[Braslav of Croatia|Braslav]] in 892, as a more independent Duke over lower Pannonia. He probably died c. 900 fighting against his former allies, the [[Magyars]].<ref name="Wolfram 2002"/> The subsequent history of Savia again becomes mirky, and historians are not sure who controlled Savia during much of the 10th century. However, it is likely that the strong ruler Tomislav, the first crowned King, was able to exert much control over Savia during his reign. It is indeed at this time that sources first refer to a "Pannonian Croatia", captured in the 10th century work, ''De Administrando Imperio''. However, after King Tomislav's death, Croatian rule over Savia likely deteriorated.<ref name="Wolfram 2002"/> |

|||

Branimir's (879–892) own actions were approved from the [[Holy See]] to bring the Croats further away from the influence of [[Byzantium]] and closer to Rome. Duke Branimir wrote to [[Pope John VIII]] affirming this split from Byzantine and commitment to the [[Papacy|Roman Papacy]]. During the solemn divine service in [[St. Peter's Basilica|St. Peter's]] church in [[Rome]] in 879, John VIII] gave his blessing to the duke and the Croatian people, about which he informed Branimir in his letters, in which Branimir was recognized as the Duke of the Croats (''Dux Chroatorum'').{{sfn|Fine|1991|p=261}} During his reign, Croatia retained its sovereignty from both the [[Holy Roman Empire]] and [[Byzantine]] rule, and became a fully recognized state.<ref name="Hrvatski leksikon">''Hrvatski leksikon'' (1996–1997) {{in lang|hr}}{{full citation needed|date=November 2014}}</ref><ref name="antoljak">Stjepan Antoljak, Pregled hrvatske povijesti, Split 1993., str. 43.</ref> After Branimir's death, Prince [[Muncimir of Croatia|Muncimir]] (892–910), Zdeslav's brother, took control of Dalmatia and ruled it independently of both Rome and Byzantium as ''divino munere Croatorum dux'' (with God's help, duke of Croats). In Dalmatia, duke [[Tomislav of Croatia|Tomislav]] (910–928) succeeded Muncimir. Tomislav successfully repelled Magyar mounted invasions of the [[Árpád dynasty|Arpads]], expelled them over the [[Sava|Sava River]], and united (western) Pannonian and Dalmatian Croats into one state.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Kralj Tomislav|url=https://hrvatski-vojnik.hr/kralj-tomislav/|date=2018-11-30|website=Hrvatski vojnik|language=hr|access-date=2020-05-27|archive-date=27 September 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200927105340/https://hrvatski-vojnik.hr/kralj-tomislav/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Evans|first=Huw M. A.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oZW2AAAAIAAJ&q=tomislav++croatia+unification|title=The Early Mediaeval Archaeology of Croatia, A.D. 600–900|date=1989|publisher=B.A.R.|isbn=978-0-86054-685-6|language=en|access-date=2 October 2020|archive-date=27 September 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230927203207/https://books.google.com/books?id=oZW2AAAAIAAJ&q=tomislav++croatia+unification|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last1=Bonifačić|first1=Antun|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KqJnAAAAMAAJ&q=tomislav++croatia+unification|title=The Croatian nation in its struggle for freedom and independence: a symposium|last2=Mihanovich|first2=Clement Simon|date=1955|publisher="Croatia" Cultural Pub. Center|language=en|access-date=2 October 2020|archive-date=27 September 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230927203209/https://books.google.com/books?id=KqJnAAAAMAAJ&q=tomislav++croatia+unification|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

;Dalmatian Croats |

|||

In the meantime, the [[Dalmatian Croat]]s were recorded to have been subject to the Kingdom of [[Italy]] under [[Lothair I]], since 828. The Croatian Prince [[Mislav of Croatia|Mislav]] (835–845) built up a formidable navy, and in 839 signed a peace treaty with [[Pietro Tradonico]], [[doge of Venice]]. The Venetians soon proceeded to battle with the independent Slavic pirates of the [[Pagania]] region, but failed to defeat them. The Bulgarian king [[Boris I of Bulgaria|Boris I]] (called by the [[Byzantine Empire]] Archont of Bulgaria after he made Christianity the official religion of Bulgaria) also waged a lengthy war against the Dalmatian Croats, trying to expand his state to the [[Adriatic]]. |

|||

===Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102)=== |

|||

The Croatian Prince [[Trpimir I of Croatia|Trpimir I]] (845–864) succeeded Mislav. In 854, there was a great battle between Trpimir's forces and the Bulgars. Neither side emerged victorious, and the outcome was the exchange of gifts and the establishment of peace. Trpimir I managed to consolidate power over Dalmatia and much of the inland regions towards [[Pannonia]], while instituting counties as a way of controlling his subordinates (an idea he picked up from the Franks). The first known written mention of the Croats, dates form 4 March 852, in [[statute]] by Trpimir. Trpimir is remembered as the initiator of the [[Trpimirović dynasty]], that ruled in Croatia, with interruptions, from 845 until 1091. After his death, an uprising was raised by a powerful nobleman from [[Knin]] - [[Domagoj of Croatia|Domagoj]], and his son [[Zdeslav of Croatia|Zdeslav]] was exiled with his brothers, Petar and [[Muncimir of Croatia|Muncimir]] to Constantinople.<ref name="John Van Antwerp Fine">{{cite book| last = Fine| first = John Van Antwerp| title = The early medieval Balkans: a critical survey from the sixth to the late twelfth century| url = http://books.google.com/?id=Y0NBxG9Id58C&pg=PA108| year = 1991| publisher = University of Michigan Press| isbn = 978-0-472-08149-3| page = 257 }}</ref> |

|||

{{main|Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102)}} |

|||

[[File:Oton Ivekovic, Krunidba kralja Tomislava.jpg|right|upright=1.10|255px|thumb|Coronation of King Tomislav by [[Oton Iveković]].]] |

|||