Gap penalty: Difference between revisions

restructure |

|||

| (100 intermediate revisions by 57 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

A '''Gap penalty''' is a method of scoring alignments of two or more sequences. When aligning sequences, introducing gaps in the sequences can allow an alignment algorithm to match more terms than a gap-less alignment can. However, minimizing gaps in an alignment is important to create a useful alignment. Too many gaps can cause an alignment to become meaningless. Gap penalties are used to adjust alignment scores based on the number and length of gaps. The five main types of gap penalties are constant, linear, affine, convex, and profile-based.<ref name=rosalind_glossary>{{Cite web|url=http://rosalind.info/glossary/gap-penalty/|title=Glossary|website=Rosalind|publisher=Rosalind Team|access-date=2021-05-20}}</ref> |

|||

The Gap Penalty is a scoring system used in bioinformatics for [[Sequence alignment|aligning]] a small portion of genetic code, more accurately, fragmented genetic sequence, also termed, [[DNA sequencing#Read_Trimming|reads]] against a reference genetic sequence (e.g. The Human Genome). The biological process of protein synthesis namely, [[Transcription (genetics)|transcription]] and [[:simple:Translation_(genetics)|translation]] or DNA replication can produce errors resulting in [[Mutation|mutations]] in the final [[Nucleic acid_sequence|nucleic acid sequence]]. Therefore, in order to make more accurate decisions in aligning reads, mutations are annotated as gaps in the sequence. Gaps are penalised via various Gap Penalty scoring methods. Gaps in a DNA sequence refer to substitutions or indels in a sequence, where indels can be insertions or deletions in the sequence. [[Insertion (genetics)|Insertions]] or [[Deletion (genetics)|deletions]] occur due to single mutations, unbalanced crossover in meiosis, slipped strand [[Slipped strand_mispairing|mispairing]] in the replication process and chromosomal [[Chromosomal translocation|translocation]].<ref>{{Cite journal|url = http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/CBBresearch/Fellows/Carroll/pubs/allTrees.pdf|title = Effects of Gap Open and Gap Extension Penalties|last = Carroll, Ridge, Clement, Snell|first = Hyrum , Perry, Mark, Quinn|date = January 1, 2007|journal = International Journal Of Bioinformatics Research And Applications|accessdate = 09/09/14|doi = |pmid = }}</ref> In alignments gaps are represented as contiguous dashes on a protein/DNA sequence alignment<ref>{{Cite web|url = http://rosalind.info/glossary/gap/|title = Glossary|date = |accessdate = 11/09/14|website = Rosalind|publisher = Rosalind Team|last = |first = }}</ref>. The scoring that occurs in Gap Penalty allows for the optimisation of sequence alignment in order to obtain the best alignment possible based on the information available. The three main types of gap penalties are constant, linear and affine gap penalty<ref>{{Cite web|url = http://rosalind.info/glossary/gap-penalty/|title = Glossary|date = |accessdate = 11/09/14|website = Rosalind|publisher = Rosalind Team|last = |first = }}</ref>. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The notion of a gap in an alignment is important in many biological applications, since the insertions or deletions comprise an entire sub-sequence and often occur from a single mutational event.<ref name=":0">{{Cite |

||

| ⚫ | * '''Genetic sequence alignment''' - In bioinformatics, gaps are used to account for genetic mutations occurring from [[Insertion (genetics)|insertions]] or [[Deletion (genetics)|deletions]] in the sequence, sometimes referred to as ''indels''. Insertions or deletions can occur due to single mutations, unbalanced crossover in [[meiosis]], [[slipped strand mispairing]], and [[chromosomal translocation]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Carroll, Ridge, Clement, Snell |first=Hyrum , Perry, Mark, Quinn |date=January 1, 2007 |title=Effects of Gap Open and Gap Extension Penalties |url=https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1289&context=facpub |journal=International Journal of Bioinformatics Research and Applications |access-date=2014-09-09}}</ref> The notion of a gap in an alignment is important in many biological applications, since the insertions or deletions comprise an entire sub-sequence and often occur from a single mutational event.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=Algorithms for Molecular Biology|date=2006-01-01|chapter=Gap Penalty|access-date=2014-09-13|chapter-url=http://www.biogem.org/downloads/notes/Gap%20Penalty.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130626060959/http://www.biogem.org/downloads/notes/Gap%20Penalty.pdf|archive-date=2013-06-26|url-status=dead}}</ref> Furthermore, single mutational events can create gaps of different sizes. Therefore, when scoring, the gaps need to be scored as a whole when aligning two sequences of DNA. Considering multiple gaps in a sequence as a larger single gap will reduce the assignment of a high cost to the mutations. For instance, two protein sequences may be relatively similar but differ at certain intervals as one protein may have a different subunit compared to the other. Representing these differing sub-sequences as gaps will allow us to treat these cases as “good matches” even though there are long consecutive runs with indel operations in the sequence. Therefore, using a good gap penalty model will avoid low scores in alignments and improve the chances of finding a true alignment.<ref name=":0" /> In genetic sequence alignments, gaps are represented as dashes(-) on a protein/DNA sequence alignment.<ref name="rosalind_glossary" /> |

||

Gap Penalty applications can be applied outside the biological cases. For instance gap penalty is used in the diff function in unix to compute the minimal difference between two files. Other applications include spell checking, plagiarism detection and speech recognition in software algorithms to name a few. |

|||

* '''Unix ''[[diff]]'' function''' - computes the minimal difference between two files similarly to plagiarism detection. |

|||

==Types of Gap Penalties== |

|||

* '''Spell checking''' - Gap penalties can help find correctly spelled words with the shortest [[edit distance]] to a misspelled word. Gaps can indicate a missing letter in the incorrectly spelled word. |

|||

* '''Plagiarism detection''' - Gap penalties allow algorithms to detect where sections of a document are plagiarized by placing gaps in original sections and matching what is identical. The gap penalty for a certain document quantifies how much of a given document is probably original or plagiarized. |

|||

== Bioinformatics applications == |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

This is the simplest type of gap penalty; where a fixed negative score is given to every gap, regardless of the gap length. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

A global alignment performs an end-to-end alignment of the query sequence with the reference sequence. Ideally, this alignment technique is most suitable for closely related sequences of similar lengths. The Needleman-Wunsch algorithm is a [[dynamic programming]] technique used to conduct global alignment. Essentially, the algorithm divides the problem into a set of sub-problems, then uses the results of the sub-problems to reconstruct a solution to the original query.<ref>{{Cite web|url = http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/1334661/bioinformatics/285871/Goals-of-bioinformatics#ref1115380|title = bioinformatics|date = 2013-07-26|access-date = 2014-09-12|website = Encyclopædia Britannica|last = Lesk|first = Arthur M}}</ref> |

|||

=== |

=== Semi-global alignment === |

||

The use of semi-global alignment exists to find a particular match within a large sequence. An example includes seeking promoters within a DNA sequence. Unlike global alignment, it compromises of no end gaps in one or both sequences. If the end gaps are penalized in one sequence 1 but not in sequence 2, it produces an alignment that contains sequence 2 within sequence 1. |

|||

| ⚫ | Compared to the constant gap penalty, the linear gap penalty takes into account the length (L) of each insertion/deletion in the gap. Therefore, if the penalty for each inserted/deleted element is B and the length of the gap L; the total gap penalty would be the product of the two BL.<ref>{{Cite book|title |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The most widely used gap penalty function is the affine gap penalty. The affine gap penalty combines the components in both the constant and linear gap penalty, taking the form A+( |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Using the affine gap penalty requires the assigning of fixed penalty values for both opening and extending a gap. This can be too rigid for use in a biological context. |

||

| ⚫ | The logarithmic gap takes the form G(L) |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Profile–profile alignment algorithms are powerful tools for detecting protein homology relationships with improved alignment accuracy.<ref name="pmid22000802">{{Cite journal |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

{{main|Smith–Waterman algorithm}} |

{{main|Smith–Waterman algorithm}} |

||

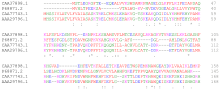

[[File: |

[[File:Protein alignment.svg|alt=text|thumb| |

||

Example of Protein Sequence Alignment |

Example of Protein Sequence Alignment |

||

]] |

]] |

||

A local sequence alignment matches a contiguous sub-section of one sequence with a contiguous sub-section of another.<ref>{{Cite journal |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| doi = 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80006-3 |

|||

| last1 = Vingron | first1 = M. |

|||

| last2 = Waterman | first2 = M. S. |

|||

| title = Sequence alignment and penalty choice. Review of concepts, case studies and implications |

|||

| journal = Journal of Molecular Biology |

|||

| volume = 235 |

|||

| issue = 1 |

|||

| pages = 1–12 |

|||

| year = 1994 |

|||

| pmid = 8289235 |

|||

| ⚫ | }}</ref> The Smith-Waterman algorithm is motivated by giving scores for matches and mismatches. Matches increase the overall score of an alignment whereas mismatches decrease the score. A good alignment then has a positive score and a poor alignment has a negative score. The [[local algorithm]] finds an alignment with the highest score by considering only alignments that score positives and picking the best one from those. The algorithm is a [[dynamic programming]] algorithm. When comparing proteins, one uses a similarity matrix which assigns a score to each possible residue pair. The score should be positive for similar residues and negative for dissimilar residue pairs. Gaps are usually penalized using a linear gap function that assigns an initial penalty for a gap opening, and an additional penalty for gap extensions, increasing the gap length. |

||

=== Scoring |

=== Scoring matrix === |

||

{{main|Substitution matrix}} |

{{main|Substitution matrix}} |

||

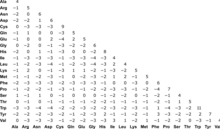

[[File:BLOSUM62. |

[[File:BLOSUM62.png|alt=text|thumb| |

||

Blosum-62 Matrix |

Blosum-62 Matrix |

||

]] |

]] |

||

[[Substitution matrix|Substitution matrices]] such as [[BLOSUM]] are used for sequence alignment of proteins.<ref name="NCBI">{{cite web |title=BLAST substitution matrices |publisher=NCBI |url= |

[[Substitution matrix|Substitution matrices]] such as [[BLOSUM]] are used for sequence alignment of proteins.<ref name="NCBI">{{cite web |title=BLAST substitution matrices |publisher=NCBI |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/html/sub_matrix.html |access-date=2012-11-27}}</ref> A Substitution matrix assigns a score for aligning any possible pair of residues.<ref name="NCBI" /> In general, different substitution matrices are tailored to detecting similarities among sequences that are diverged by differing degrees. A single matrix may be reasonably efficient over a relatively broad range of evolutionary change.<ref name="NCBI" /> |

||

The BLOSUM-62 matrix is one of the best substitution matrices for detecting weak protein similarities.<ref name="NCBI" /> BLOSUM matrices with high numbers are designed for comparing closely related sequences, while those with low numbers are designed for comparing distant related sequences. For example, BLOSUM-80 is used for alignments that are more similar in sequence, and BLOSUM-45 is used for alignments that have diverged from each other.<ref name="NCBI" /> For particularly long and weak alignments, the BLOSUM-45 matrix may provide the best results. Short alignments are more easily detected using a matrix with a higher "relative entropy" than that of BLOSUM-62. The BLOSUM series does not include any matrices with relative entropies suitable for the shortest queries.<ref name="NCBI" /> |

The BLOSUM-62 matrix is one of the best substitution matrices for detecting weak protein similarities.<ref name="NCBI" /> BLOSUM matrices with high numbers are designed for comparing closely related sequences, while those with low numbers are designed for comparing distant related sequences. For example, BLOSUM-80 is used for alignments that are more similar in sequence, and BLOSUM-45 is used for alignments that have diverged from each other.<ref name="NCBI" /> For particularly long and weak alignments, the BLOSUM-45 matrix may provide the best results. Short alignments are more easily detected using a matrix with a higher "relative entropy" than that of BLOSUM-62. The BLOSUM series does not include any matrices with relative entropies suitable for the shortest queries.<ref name="NCBI" /> |

||

=== Indels === |

=== Indels === |

||

{{main|Indel}} |

{{main|Indel}} |

||

During [[DNA |

During [[DNA replication]], the cellular replication machinery is prone to making two types of errors while duplicating the DNA. These two replication errors are insertions and deletions of single DNA bases from the DNA strand (indels).<ref name="Garcia-Diaz2006">{{Cite journal |last=Garcia-Diaz |first=Miguel |title= Mechanism of a genetic glissando: structural biology of indel mutations |journal=Trends in Biochemical Sciences |issue=4 |year=2006 |volume=31|doi=10.1016/j.tibs.2006.02.004 |pages=206–214 |pmid=16545956}}</ref> [[Indels]] can have severe biological consequences by causing mutations in the DNA strand that could result in the inactivation or over activation of the target protein. For example, if a one or two nucleotide indel occurs in a coding sequence the result will be a shift in the reading frame, or a [[frameshift mutation]] that may render the protein inactive.<ref name="Garcia-Diaz2006" /> The biological consequences of indels are often deleterious and are frequently associated with pathologies such as [[cancer]]. However, not all indels are frameshift mutations. If indels occur in trinucleotides, the result is an extension of the protein sequence that may also have implications on protein function.<ref name="Garcia-Diaz2006" /> |

||

==Types== |

|||

[[File:Comparison of Gap Penalty Funcitons.png|thumb|This graph shows the difference between types of gap penalties. The exact numbers will change for different applications but this shows the relative shape of each function.]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

This is the simplest type of gap penalty: a fixed negative score is given to every gap, regardless of its length.<ref name=":0" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://rosalind.info/glossary/constant-gap-penalty/|title=Glossary - Constant Gap Penalty|date=12 Aug 2014|website=Rosalind|publisher=Rosalind Team|access-date=12 Aug 2014}}</ref> This encourages the algorithm to make fewer, larger, gaps leaving larger contiguous sections. |

|||

ATTGACCTGA |

|||

|| ||||| |

|||

AT---CCTGA |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

=== Linear === |

|||

| ⚫ | Compared to the constant gap penalty, the linear gap penalty takes into account the length (L) of each insertion/deletion in the gap. Therefore, if the penalty for each inserted/deleted element is B and the length of the gap L; the total gap penalty would be the product of the two BL.<ref name="Hodgman C, French A, Westhead D, 2009 143–144">{{Cite book|title=BIOS Instant Notes in Bioinformatics|vauthors=Hodgman C, French A, Westhead D|publisher=Garland Science|year=2009|isbn=978-0203967249|pages=143–144}}</ref> This method favors shorter gaps, with total score decreasing with each additional gap. |

||

ATTGACCTGA |

|||

|| ||||| |

|||

AT---CCTGA |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The most widely used gap penalty function is the affine gap penalty. The affine gap penalty combines the components in both the constant and linear gap penalty, taking the form <math>A+B\cdot (L-1)</math>. This introduces new terms, A is known as the gap opening penalty, B the gap extension penalty and L the length of the gap. Gap opening refers to the cost required to open a gap of any length, and gap extension the cost to extend the length of an existing gap by 1.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://rosalind.info/problems/gaff/|title=Global Alignment with Scoring Matrix and Affine Gap Penalty|date=2012-07-02|website=Rosalind|publisher=Rosalind Team|access-date=2014-09-12}}</ref> Often it is unclear as to what the values A and B should be as it differs according to purpose. In general, if the interest is to find closely related matches (e.g. removal of vector sequence during genome sequencing), a higher gap penalty should be used to reduce gap openings. On the other hand, gap penalty should be lowered when interested in finding a more distant match.<ref name="Hodgman C, French A, Westhead D, 2009 143–144"/> The relationship between A and B also have an effect on gap size. If the size of the gap is important, a small A and large B (more costly to extend a gap) is used and vice versa. Only the ratio A/B is important, as multiplying both by the same positive constant <math>k</math> will increase all penalties by <math>k</math>: <math>kA+kB (L-1) = k(A+B(L-1))</math> which does not change the relative penalty between different alignments. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Using the affine gap penalty requires the assigning of fixed penalty values for both opening and extending a gap. This can be too rigid for use in a biological context.<ref name=":1">{{Cite book|title=Algorithms in Bioinformatics : A Practical Introduction|last=Sung|first=Wing-Kin|publisher=CRC Press|year=2011|isbn=978-1420070347|pages=42–47}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | The logarithmic gap takes the form <math>G(L)=A+C\ln L</math> and was proposed as studies had shown the distribution of indel sizes obey a power law.<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|last=Cartwright|first=Reed|date=2006-12-05|title=Logarithmic gap costs decrease alignment accuracy|journal=BMC Bioinformatics|volume=7|pages=527|doi=10.1186/1471-2105-7-527|pmc=1770940|pmid=17147805 |doi-access=free }}</ref> Another proposed issue with the use of affine gaps is the favoritism of aligning sequences with shorter gaps. Logarithmic gap penalty was invented to modify the affine gap so that long gaps are desirable.<ref name=":1" /> However, in contrast to this, it has been found that using logarithmatic models had produced poor alignments when compared to affine models.<ref name=":2" /> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Profile–profile alignment algorithms are powerful tools for detecting protein homology relationships with improved alignment accuracy.<ref name="pmid22000802">{{Cite journal|vauthors=Wang C, Yan RX, Wang XF, Si JN, Zhang Z|date=12 October 2011|title=Comparison of linear gap penalties and profile-based variable gap penalties in profile-profile alignments|journal=Comput Biol Chem|volume=35|issue=5|pages=308–318|doi=10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2011.07.006|pmid=22000802}}</ref> Profile-profile alignments are based on the statistical indel frequency profiles from multiple sequence alignments generated by PSI-BLAST searches.<ref name="pmid22000802" /> Rather than using substitution matrices to measure the similarity of amino acid pairs, profile–profile alignment methods require a profile-based scoring function to measure the similarity of profile vector pairs.<ref name="pmid22000802" /> Profile-profile alignments employ gap penalty functions. The gap information is usually used in the form of indel frequency profiles, which is more specific for the sequences to be aligned. ClustalW and MAFFT adopted this kind of gap penalty determination for their multiple sequence alignments.<ref name="pmid22000802" /> Alignment accuracies can be improved using this model, especially for proteins with low sequence identity. Some profile–profile alignment algorithms also run the secondary structure information as one term in their scoring functions, which improves alignment accuracy.<ref name="pmid22000802" /> |

||

== Comparing time complexities == |

== Comparing time complexities == |

||

{{Further|Time complexity}} |

|||

The use of alignment in [[computational biology]] often involves sequences of varying lengths. It is important to pick a model that would efficiently run at a known input size. The time taken to run the algorithm is known as the time complexity. |

|||

{| border="1" class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; margin: 1em auto 1em auto" |

{| border="1" class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; margin: 1em auto 1em auto" |

||

|+ Time complexities for various gap penalty models |

|+ Time complexities for various gap penalty models |

||

| Line 66: | Line 96: | ||

|- |

|- |

||

|} |

|} |

||

==Assigning Gap Penalty Values== |

|||

Gap penalty values are designed to reduce the score when an alignment has been disturbed by indels. The value should be small enough to allow a previously accumulated alignment to continue with an insertion in one of the sequences but should not be so large that this previous alignment score is removed completely. There are two strategies when assigning values to gaps: |

|||

# Keep the score similar regardless of gap length. Allow a constant overall gap penalty regardless of gap length. Therefore assign no gap extension penalty and only penalize the sequence when there is a gap open. This will penalize a large gap by the same extent as a small gap.<ref name="EBML-EBI">{{Cite web |title=About Gaps In Sequence Alignments |publisher=EMBL-EBI |url=http://www.ebi.ac.uk/help/gaps.html |accessdate=2012-11-27}} {{Dead link|date=May 2013}}</ref> |

|||

# Make the score becomes larger as a linear function of gap length. Have a larger gap opening penalty followed by a gap extension penalty that is smaller than the gap open penalty. This will penalize several small gaps by the same extent as 1 large gap.<ref name="EBML-EBI" /> |

|||

==Challenges== |

==Challenges== |

||

| ⚫ | There are a few challenges when it comes to working with gaps. When working with popular algorithms there seems to be little theoretical basis for the form of the gap penalty functions.<ref name="pmid14705025">{{cite journal |vauthors=Wrabl JO, Grishin NV |title=Gaps in structurally similar proteins: towards improvement of multiple sequence alignment |journal=Proteins |date=1 January 2004 |volume=54 |issue=1 |pages=71–87 |pmid=14705025 |doi=10.1002/prot.10508|s2cid=20474119 }}</ref> Consequently, for any alignment situation gap placement must be empirically determined.<ref name="pmid14705025" /> Also, pairwise alignment gap penalties, such as the affine gap penalty, are often implemented independent of the amino acid types in the inserted or deleted fragment or at the broken ends, despite evidence that specific residue types are preferred in gap regions.<ref name="pmid14705025" /> Finally, alignment of sequences implies alignment of the corresponding structures, but the relationships between structural features of gaps in proteins and their corresponding sequences are only imperfectly known. Because of this incorporating structural information into gap penalties is difficult to do.<ref name="pmid14705025" /> Some algorithms use predicted or actual structural information to bias the placement of gaps. However, only a minority of sequences have known structures, and most alignment problems involve sequences of unknown secondary and tertiary structure.<ref name="pmid14705025" /> |

||

| ⚫ | There are a few challenges when it comes to working with gaps. When working with popular algorithms there seems to be little theoretical basis for the form of the gap penalty functions.<ref name="pmid14705025">{{cite journal | |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

<references /> |

<references /> |

||

===Further reading=== |

===Further reading=== |

||

* {{cite journal | |

* {{cite journal |vauthors=Taylor WR, Munro RE |year=1997 |title=Multiple sequence threading: conditional gap placement |journal=Fold Des |volume=2 |issue=4 |pages=S33-9 |doi=10.1016/S1359-0278(97)00061-8|pmid=9269566 |doi-access=free }} |

||

* {{cite journal |doi=10.1007/BF02458279 |author=Taylor WR |year=1996 |title=A non-local gap-penalty for profile alignment |journal=Bull Math Biol |volume=58 |issue=1 |pages=1–18 |pmid=8819751}} |

* {{cite journal |doi=10.1007/BF02458279 |author=Taylor WR |year=1996 |title=A non-local gap-penalty for profile alignment |journal=Bull Math Biol |volume=58 |issue=1 |pages=1–18 |pmid=8819751|s2cid=189884646 }} |

||

* {{cite journal |doi=10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80006-3 | |

* {{cite journal |doi=10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80006-3 |vauthors=Vingron M, Waterman MS |year=1994 |title=Sequence alignment and penalty choice. Review of concepts, case studies and implications |journal=J Mol Biol |volume=235 |issue=1 |pages=1–12 |pmid=8289235}} |

||

* {{cite journal |author=Panjukov VV |year=1993 |title=Finding steady alignments: similarity and distance |journal=Comput Appl Biosci |volume=9 |issue=3 |pages=285–90 |pmid=8324629 |doi=10.1093/bioinformatics/9.3.285}} |

* {{cite journal |author=Panjukov VV |year=1993 |title=Finding steady alignments: similarity and distance |journal=Comput Appl Biosci |volume=9 |issue=3 |pages=285–90 |pmid=8324629 |doi=10.1093/bioinformatics/9.3.285}} |

||

* {{cite journal |author=Alexandrov NN |year=1992 |title=Local multiple alignment by consensus matrix |journal=Comput Appl Biosci |volume=8 |issue=4 |pages=339–45 |pmid=1498689 |doi=10.1093/bioinformatics/8.4.339}} |

* {{cite journal |author=Alexandrov NN |year=1992 |title=Local multiple alignment by consensus matrix |journal=Comput Appl Biosci |volume=8 |issue=4 |pages=339–45 |pmid=1498689 |doi=10.1093/bioinformatics/8.4.339}} |

||

* {{cite journal |author=Hein J |year=1989 |title=A new method that simultaneously aligns and reconstructs ancestral sequences for any number of homologous sequences, when the phylogeny is given |journal=Mol Biol Evol |volume=6 |issue=6 |pages=649–68 |pmid=2488477}} |

* {{cite journal |author=Hein J |year=1989 |title=A new method that simultaneously aligns and reconstructs ancestral sequences for any number of homologous sequences, when the phylogeny is given |journal=Mol Biol Evol |volume=6 |issue=6 |pages=649–68 |pmid=2488477|doi=10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040577 |doi-access=free }} |

||

* {{cite journal |author=Henneke CM |year=1989 |title=A multiple sequence alignment algorithm for homologous proteins using secondary structure information and optionally keying alignments to functionally important sites |journal=Comput Appl Biosci |volume=5 |issue=2 |pages=141–50 |pmid=2751764 |doi=10.1093/bioinformatics/5.2.141}} |

* {{cite journal |author=Henneke CM |year=1989 |title=A multiple sequence alignment algorithm for homologous proteins using secondary structure information and optionally keying alignments to functionally important sites |journal=Comput Appl Biosci |volume=5 |issue=2 |pages=141–50 |pmid=2751764 |doi=10.1093/bioinformatics/5.2.141}} |

||

* {{cite journal |doi=10.1093/nar/12.13.5529 | |

* {{cite journal |doi=10.1093/nar/12.13.5529 |vauthors=Reich JG, Drabsch H, Daumler A |year=1984 |title=On the statistical assessment of similarities in DNA sequences |journal=Nucleic Acids Res |volume=12 |issue=13 |pages=5529–43 |pmid=6462914 |pmc=318937}} |

||

[[Category:Computational phylogenetics]] |

[[Category:Computational phylogenetics]] |

||

[[Category:Bioinformatics]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 14:32, 2 July 2024

A Gap penalty is a method of scoring alignments of two or more sequences. When aligning sequences, introducing gaps in the sequences can allow an alignment algorithm to match more terms than a gap-less alignment can. However, minimizing gaps in an alignment is important to create a useful alignment. Too many gaps can cause an alignment to become meaningless. Gap penalties are used to adjust alignment scores based on the number and length of gaps. The five main types of gap penalties are constant, linear, affine, convex, and profile-based.[1]

Applications

[edit]- Genetic sequence alignment - In bioinformatics, gaps are used to account for genetic mutations occurring from insertions or deletions in the sequence, sometimes referred to as indels. Insertions or deletions can occur due to single mutations, unbalanced crossover in meiosis, slipped strand mispairing, and chromosomal translocation.[2] The notion of a gap in an alignment is important in many biological applications, since the insertions or deletions comprise an entire sub-sequence and often occur from a single mutational event.[3] Furthermore, single mutational events can create gaps of different sizes. Therefore, when scoring, the gaps need to be scored as a whole when aligning two sequences of DNA. Considering multiple gaps in a sequence as a larger single gap will reduce the assignment of a high cost to the mutations. For instance, two protein sequences may be relatively similar but differ at certain intervals as one protein may have a different subunit compared to the other. Representing these differing sub-sequences as gaps will allow us to treat these cases as “good matches” even though there are long consecutive runs with indel operations in the sequence. Therefore, using a good gap penalty model will avoid low scores in alignments and improve the chances of finding a true alignment.[3] In genetic sequence alignments, gaps are represented as dashes(-) on a protein/DNA sequence alignment.[1]

- Unix diff function - computes the minimal difference between two files similarly to plagiarism detection.

- Spell checking - Gap penalties can help find correctly spelled words with the shortest edit distance to a misspelled word. Gaps can indicate a missing letter in the incorrectly spelled word.

- Plagiarism detection - Gap penalties allow algorithms to detect where sections of a document are plagiarized by placing gaps in original sections and matching what is identical. The gap penalty for a certain document quantifies how much of a given document is probably original or plagiarized.

Bioinformatics applications

[edit]Global alignment

[edit]A global alignment performs an end-to-end alignment of the query sequence with the reference sequence. Ideally, this alignment technique is most suitable for closely related sequences of similar lengths. The Needleman-Wunsch algorithm is a dynamic programming technique used to conduct global alignment. Essentially, the algorithm divides the problem into a set of sub-problems, then uses the results of the sub-problems to reconstruct a solution to the original query.[4]

Semi-global alignment

[edit]The use of semi-global alignment exists to find a particular match within a large sequence. An example includes seeking promoters within a DNA sequence. Unlike global alignment, it compromises of no end gaps in one or both sequences. If the end gaps are penalized in one sequence 1 but not in sequence 2, it produces an alignment that contains sequence 2 within sequence 1.

Local alignment

[edit]

A local sequence alignment matches a contiguous sub-section of one sequence with a contiguous sub-section of another.[5] The Smith-Waterman algorithm is motivated by giving scores for matches and mismatches. Matches increase the overall score of an alignment whereas mismatches decrease the score. A good alignment then has a positive score and a poor alignment has a negative score. The local algorithm finds an alignment with the highest score by considering only alignments that score positives and picking the best one from those. The algorithm is a dynamic programming algorithm. When comparing proteins, one uses a similarity matrix which assigns a score to each possible residue pair. The score should be positive for similar residues and negative for dissimilar residue pairs. Gaps are usually penalized using a linear gap function that assigns an initial penalty for a gap opening, and an additional penalty for gap extensions, increasing the gap length.

Scoring matrix

[edit]

Substitution matrices such as BLOSUM are used for sequence alignment of proteins.[6] A Substitution matrix assigns a score for aligning any possible pair of residues.[6] In general, different substitution matrices are tailored to detecting similarities among sequences that are diverged by differing degrees. A single matrix may be reasonably efficient over a relatively broad range of evolutionary change.[6] The BLOSUM-62 matrix is one of the best substitution matrices for detecting weak protein similarities.[6] BLOSUM matrices with high numbers are designed for comparing closely related sequences, while those with low numbers are designed for comparing distant related sequences. For example, BLOSUM-80 is used for alignments that are more similar in sequence, and BLOSUM-45 is used for alignments that have diverged from each other.[6] For particularly long and weak alignments, the BLOSUM-45 matrix may provide the best results. Short alignments are more easily detected using a matrix with a higher "relative entropy" than that of BLOSUM-62. The BLOSUM series does not include any matrices with relative entropies suitable for the shortest queries.[6]

Indels

[edit]During DNA replication, the cellular replication machinery is prone to making two types of errors while duplicating the DNA. These two replication errors are insertions and deletions of single DNA bases from the DNA strand (indels).[7] Indels can have severe biological consequences by causing mutations in the DNA strand that could result in the inactivation or over activation of the target protein. For example, if a one or two nucleotide indel occurs in a coding sequence the result will be a shift in the reading frame, or a frameshift mutation that may render the protein inactive.[7] The biological consequences of indels are often deleterious and are frequently associated with pathologies such as cancer. However, not all indels are frameshift mutations. If indels occur in trinucleotides, the result is an extension of the protein sequence that may also have implications on protein function.[7]

Types

[edit]

Constant

[edit]This is the simplest type of gap penalty: a fixed negative score is given to every gap, regardless of its length.[3][8] This encourages the algorithm to make fewer, larger, gaps leaving larger contiguous sections.

ATTGACCTGA || ||||| AT---CCTGA

Aligning two short DNA sequences, with '-' depicting a gap of one base pair. If each match was worth 1 point and the whole gap -1, the total score: 7 − 1 = 6.

Linear

[edit]Compared to the constant gap penalty, the linear gap penalty takes into account the length (L) of each insertion/deletion in the gap. Therefore, if the penalty for each inserted/deleted element is B and the length of the gap L; the total gap penalty would be the product of the two BL.[9] This method favors shorter gaps, with total score decreasing with each additional gap.

ATTGACCTGA || ||||| AT---CCTGA

Unlike constant gap penalty, the size of the gap is considered. With a match with score 1 and each gap -1, the score here is (7 − 3 = 4).

Affine

[edit]The most widely used gap penalty function is the affine gap penalty. The affine gap penalty combines the components in both the constant and linear gap penalty, taking the form . This introduces new terms, A is known as the gap opening penalty, B the gap extension penalty and L the length of the gap. Gap opening refers to the cost required to open a gap of any length, and gap extension the cost to extend the length of an existing gap by 1.[10] Often it is unclear as to what the values A and B should be as it differs according to purpose. In general, if the interest is to find closely related matches (e.g. removal of vector sequence during genome sequencing), a higher gap penalty should be used to reduce gap openings. On the other hand, gap penalty should be lowered when interested in finding a more distant match.[9] The relationship between A and B also have an effect on gap size. If the size of the gap is important, a small A and large B (more costly to extend a gap) is used and vice versa. Only the ratio A/B is important, as multiplying both by the same positive constant will increase all penalties by : which does not change the relative penalty between different alignments.

Convex

[edit]Using the affine gap penalty requires the assigning of fixed penalty values for both opening and extending a gap. This can be too rigid for use in a biological context.[11]

The logarithmic gap takes the form and was proposed as studies had shown the distribution of indel sizes obey a power law.[12] Another proposed issue with the use of affine gaps is the favoritism of aligning sequences with shorter gaps. Logarithmic gap penalty was invented to modify the affine gap so that long gaps are desirable.[11] However, in contrast to this, it has been found that using logarithmatic models had produced poor alignments when compared to affine models.[12]

Profile-based

[edit]Profile–profile alignment algorithms are powerful tools for detecting protein homology relationships with improved alignment accuracy.[13] Profile-profile alignments are based on the statistical indel frequency profiles from multiple sequence alignments generated by PSI-BLAST searches.[13] Rather than using substitution matrices to measure the similarity of amino acid pairs, profile–profile alignment methods require a profile-based scoring function to measure the similarity of profile vector pairs.[13] Profile-profile alignments employ gap penalty functions. The gap information is usually used in the form of indel frequency profiles, which is more specific for the sequences to be aligned. ClustalW and MAFFT adopted this kind of gap penalty determination for their multiple sequence alignments.[13] Alignment accuracies can be improved using this model, especially for proteins with low sequence identity. Some profile–profile alignment algorithms also run the secondary structure information as one term in their scoring functions, which improves alignment accuracy.[13]

Comparing time complexities

[edit]The use of alignment in computational biology often involves sequences of varying lengths. It is important to pick a model that would efficiently run at a known input size. The time taken to run the algorithm is known as the time complexity.

| Type | Time |

|---|---|

| Constant gap penalty | O(mn) |

| Affine gap penalty | O(mn) |

| Convex gap penalty | O(mn lg(m+n)) |

Challenges

[edit]There are a few challenges when it comes to working with gaps. When working with popular algorithms there seems to be little theoretical basis for the form of the gap penalty functions.[14] Consequently, for any alignment situation gap placement must be empirically determined.[14] Also, pairwise alignment gap penalties, such as the affine gap penalty, are often implemented independent of the amino acid types in the inserted or deleted fragment or at the broken ends, despite evidence that specific residue types are preferred in gap regions.[14] Finally, alignment of sequences implies alignment of the corresponding structures, but the relationships between structural features of gaps in proteins and their corresponding sequences are only imperfectly known. Because of this incorporating structural information into gap penalties is difficult to do.[14] Some algorithms use predicted or actual structural information to bias the placement of gaps. However, only a minority of sequences have known structures, and most alignment problems involve sequences of unknown secondary and tertiary structure.[14]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Glossary". Rosalind. Rosalind Team. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ^ Carroll, Ridge, Clement, Snell, Hyrum , Perry, Mark, Quinn (January 1, 2007). "Effects of Gap Open and Gap Extension Penalties". International Journal of Bioinformatics Research and Applications. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Gap Penalty" (PDF). Algorithms for Molecular Biology. 2006-01-01. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-26. Retrieved 2014-09-13.

- ^ Lesk, Arthur M (2013-07-26). "bioinformatics". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2014-09-12.

- ^ Vingron, M.; Waterman, M. S. (1994). "Sequence alignment and penalty choice. Review of concepts, case studies and implications". Journal of Molecular Biology. 235 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80006-3. PMID 8289235.

- ^ a b c d e f "BLAST substitution matrices". NCBI. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ^ a b c Garcia-Diaz, Miguel (2006). "Mechanism of a genetic glissando: structural biology of indel mutations". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 31 (4): 206–214. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2006.02.004. PMID 16545956.

- ^ "Glossary - Constant Gap Penalty". Rosalind. Rosalind Team. 12 Aug 2014. Retrieved 12 Aug 2014.

- ^ a b Hodgman C, French A, Westhead D (2009). BIOS Instant Notes in Bioinformatics. Garland Science. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0203967249.

- ^ "Global Alignment with Scoring Matrix and Affine Gap Penalty". Rosalind. Rosalind Team. 2012-07-02. Retrieved 2014-09-12.

- ^ a b Sung, Wing-Kin (2011). Algorithms in Bioinformatics : A Practical Introduction. CRC Press. pp. 42–47. ISBN 978-1420070347.

- ^ a b Cartwright, Reed (2006-12-05). "Logarithmic gap costs decrease alignment accuracy". BMC Bioinformatics. 7: 527. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-7-527. PMC 1770940. PMID 17147805.

- ^ a b c d e Wang C, Yan RX, Wang XF, Si JN, Zhang Z (12 October 2011). "Comparison of linear gap penalties and profile-based variable gap penalties in profile-profile alignments". Comput Biol Chem. 35 (5): 308–318. doi:10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2011.07.006. PMID 22000802.

- ^ a b c d e Wrabl JO, Grishin NV (1 January 2004). "Gaps in structurally similar proteins: towards improvement of multiple sequence alignment". Proteins. 54 (1): 71–87. doi:10.1002/prot.10508. PMID 14705025. S2CID 20474119.

Further reading

[edit]- Taylor WR, Munro RE (1997). "Multiple sequence threading: conditional gap placement". Fold Des. 2 (4): S33-9. doi:10.1016/S1359-0278(97)00061-8. PMID 9269566.

- Taylor WR (1996). "A non-local gap-penalty for profile alignment". Bull Math Biol. 58 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1007/BF02458279. PMID 8819751. S2CID 189884646.

- Vingron M, Waterman MS (1994). "Sequence alignment and penalty choice. Review of concepts, case studies and implications". J Mol Biol. 235 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80006-3. PMID 8289235.

- Panjukov VV (1993). "Finding steady alignments: similarity and distance". Comput Appl Biosci. 9 (3): 285–90. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/9.3.285. PMID 8324629.

- Alexandrov NN (1992). "Local multiple alignment by consensus matrix". Comput Appl Biosci. 8 (4): 339–45. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/8.4.339. PMID 1498689.

- Hein J (1989). "A new method that simultaneously aligns and reconstructs ancestral sequences for any number of homologous sequences, when the phylogeny is given". Mol Biol Evol. 6 (6): 649–68. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040577. PMID 2488477.

- Henneke CM (1989). "A multiple sequence alignment algorithm for homologous proteins using secondary structure information and optionally keying alignments to functionally important sites". Comput Appl Biosci. 5 (2): 141–50. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/5.2.141. PMID 2751764.

- Reich JG, Drabsch H, Daumler A (1984). "On the statistical assessment of similarities in DNA sequences". Nucleic Acids Res. 12 (13): 5529–43. doi:10.1093/nar/12.13.5529. PMC 318937. PMID 6462914.