Lichfield: Difference between revisions

→Geography: Photo already exists in the infobox, don't repeat it. |

|||

| (507 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Cathedral city in Staffordshire, England}} |

|||

{{Other uses}} |

{{Other uses}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date= |

{{Use dmy dates|date=October 2014}} |

||

{{Use British English|date=August 2012}} |

{{Use British English|date=August 2012}} |

||

{{Infobox UK place |

{{More citations needed|date=November 2024|name=Sangsangaplaz}}{{Infobox UK place |

||

| official_name = Lichfield |

|||

| type = [[City status in the United Kingdom|City]] and [[civil parish]] |

|||

| local_name=City of Lichfield |

|||

| country = England |

|||

| civil_parish = Lichfield |

|||

| region = West Midlands |

|||

| static_image_name = Lichfield Collage.jpg |

|||

| static_image_width = 280 |

|||

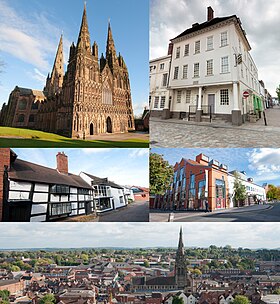

| static_image_caption=From top left: [[Lichfield Cathedral]]; [[Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum]]; Quonians Lane; [[Lichfield Garrick Theatre|Garrick Theatre]]; Cityscape. |

|||

| static_image_caption = From top left: [[Lichfield Cathedral]]; [[Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum]]; Quonians Lane; [[Lichfield Garrick Theatre|Garrick Theatre]] and skyline of the city. |

|||

|static_image_2_name= Lichfield City Arms.jpg |

|||

| static_image_2_name = |

|||

|static_image_2_width= 75px |

|||

| static_image_2_width = 75px |

|||

|static_image_2_caption=Coat of arms of Lichfield<br>'''Motto:''' ''Salve, magna parens'' (Hail great parent) |

|||

| static_image_2_caption = Coat of arms of Lichfield<br />'''Motto:''' ''Salve, magna parens'' (Hail, great parent) |

|||

| area_footnotes=<ref>{{cite web|url = http://www.lichfield.gov.uk/cc-statistics.ihtml|title = Lichfield City Council - Statistics|date = |publisher = |accessdate = }}</ref> |

|||

| area_footnotes = <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.lichfield.gov.uk/cc-statistics.ihtml|title=Lichfield City Council - Statistics|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110724162428/http://www.lichfield.gov.uk/cc-statistics.ihtml|archive-date=24 July 2011|df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

|||

| area_total_km2 =14.02 |

|||

| area_total_km2 = 14.02 |

|||

| population = 32,219 |

|||

| population = 34,738 |

|||

| population_ref =<ref>{{cite web|url =http://www.neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk/dissemination/LeadTableView.do?a=7&b=11125588&c=lichfield&d=16&e=61&g=6463512&i=1001x1003x1032x1004&m=0&r=1&s=1359584381859&enc=1&dsFamilyId=2491|title = Office for National Statistics - Lichfield Parish Population|date = 2013-01-30 |publisher = |accessdate = }}</ref> |

|||

| population_ref = |

|||

| population_density= {{convert|2298|/km2|/sqmi|abbr=on}} |

|||

|population_demonym = Lichfieldian |

|||

| os_grid_reference=SK115097 |

|||

| os_grid_reference = SK115097 |

|||

| latitude=52.6835 |

|||

| coordinates = {{coord|52.682|-1.829|display=inline,title}} |

|||

| longitude=-1.82653 |

|||

| post_town = LICHFIELD |

|||

| postcode_area = WS |

|||

| postcode_district = WS13, WS14 |

|||

| dial_code = 01543 |

|||

| constituency_westminster = [[Lichfield (UK Parliament constituency)|Lichfield]] |

|||

| london_distance = {{convert|121|mi}} [[Points of the compass|NNW]] |

|||

| shire_district = [[Lichfield District|Lichfield]] |

|||

| shire_county = [[Staffordshire]] |

|||

| website = [http://www.lichfield.gov.uk/ www.lichfield.gov.uk] |

|||

| module = {{Infobox mapframe|stroke-width=1|zoom=11|height=160|width=240}} City map |

|||

}} |

|||

| parts_type = Areas of the city |

|||

| p1 = [[Boley Park]] |

|||

| p2 = [[Chadsmead]] |

|||

| p3 = [[Curborough]] |

|||

| p4 = [[Darwin Park]] |

|||

| p5 = [[Fradley]] |

|||

| p6 = [[Leomansley]] |

|||

| p7 = [[Pipehill]] |

|||

| p8 = [[St Johns, Lichfield|St Johns]] |

|||

| p9 = [[Stowe, Lichfield|Stowe]] |

|||

| p10 = [[Streethay]] |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Lichfield''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|l|ɪ|tʃ|f|iː|l|d}}) is a [[city status in the United Kingdom|cathedral city]] and [[Civil parishes in England|civil parish]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ons.gov.uk/about-statistics/geography/products/geog-products-area/names-codes/administrative/index.html |title=Names and codes for Administrative Geography |date=31 December 2008 |publisher=Office for National Statistics |access-date=15 September 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url=http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100403045115/http://www.ons.gov.uk/about-statistics/geography/products/geog-products-area/names-codes/administrative/index.html |archive-date=3 April 2010 }}</ref> in [[Staffordshire]], [[England]]. Lichfield is situated {{convert|18|mi|km|0}} south-east of the county town of [[Stafford]], {{convert|9|mi|km|0}} north-east of [[Walsall]], {{convert|8|mi|km}} north-west of [[Tamworth, Staffordshire|Tamworth]] and {{convert|13|mi|km|0}} south-west of [[Burton upon Trent]]. At the time of the 2021 Census, the population was 34,738 and the population of the wider [[Lichfield District]] was 106,400.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Statistics - Lichfield City Council |url=https://www.lichfield.gov.uk/Statistics_749.aspx |access-date=2023-03-18 |website=www.lichfield.gov.uk}}</ref> |

|||

Notable for its three-spired medieval [[Lichfield Cathedral|cathedral]], Lichfield was the birthplace of [[Samuel Johnson]], the writer of the first authoritative ''[[A Dictionary of the English Language|Dictionary of the English Language]]''. The city's [[recorded history]] began when [[Chad of Mercia]] arrived to establish his [[Diocese of Lichfield|Bishopric]] in 669 AD and the settlement grew as the ecclesiastical centre of [[Mercia]]. In 2009, the [[Staffordshire Hoard]], the largest hoard of [[Anglo-Saxons|Anglo-Saxon]] gold and silver metalwork, was found {{convert|4|mi|km|abbr=on}} south-west of Lichfield. |

|||

'''Lichfield''' {{IPAc-en|ˈ|l|ɪ|tʃ|f|iː|l|d}} is a [[city status in the United Kingdom|cathedral city]] and [[Civil parishes in England|civil parish]]<ref>{{cite web|url = http://www.ons.gov.uk/about-statistics/geography/products/geog-products-area/names-codes/administrative/index.html|title = Names and codes for Administrative Geography|date = 31 December 2008|publisher = Office for National Statistics|accessdate = 15 September 2009}}</ref> in [[Staffordshire]], England. One of eight civil parishes with city status in England, Lichfield is situated roughly {{convert|16|mi|km|abbr=on}} north of [[Birmingham]]. At the time of the 2011 Census the population was estimated at 32,219 and the wider [[Lichfield District]] at 100,700.<ref>{{cite web|url = http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/interactive/vp2-2011-census-comparator/index.html|title = Office for National Statistics - Census 2011|date = 20 July 2012}}</ref> |

|||

The development of the city was consolidated in the 12th century under [[Roger de Clinton]], who fortified the [[Cathedral Close, Lichfield|Cathedral Close]] and also laid out the town with the ladder-shaped street pattern that survives to this day. Lichfield's heyday was in the 18th century, when it developed into a thriving coaching city. This was a period of great intellectual activity; the city was the home of many famous people including Samuel Johnson, [[David Garrick]], [[Erasmus Darwin]] and [[Anna Seward]], prompting Johnson's remark that Lichfield was "a city of philosophers". |

|||

Notable for its three-spired medieval [[Lichfield Cathedral|cathedral]], Lichfield was the birthplace of [[Samuel Johnson]], the writer of the first authoritative ''[[A Dictionary of the English Language|Dictionary of the English Language]]''. The city's [[recorded history]] began when [[Chad of Mercia]] arrived to establish his [[Diocese of Lichfield|Bishopric]] in 669 CE and the settlement grew as the ecclesiastical centre of [[Mercia]]. In 2009, the [[Staffordshire Hoard]], the largest hoard of [[Anglo-Saxons|Anglo-Saxon]] gold and silver metalwork, was found {{convert|5.9|km|mi|abbr=on}} southwest of Lichfield. |

|||

Today, the city still retains its old importance as an ecclesiastical centre, and its industrial and commercial development has been limited. The centre of the city has over 230 [[Listed buildings in Lichfield|listed buildings]] (including many examples of [[Georgian architecture]]) and preserves much of its historic character. |

|||

The development of the city was consolidated in the 12th century under [[Roger de Clinton]] who fortified the [[Cathedral Close, Lichfield|Cathedral Close]] and also laid out the town with the ladder-shaped street pattern that survives to this day. Lichfield's heyday was in the 18th century when it developed into a thriving coaching city. This was a period of great intellectual activity, the city being the home of many famous people including Samuel Johnson, [[David Garrick]], [[Erasmus Darwin]] and [[Anna Seward]], and prompted Johnson's remark that Lichfield was "a city of philosophers". |

|||

== Toponymy == |

|||

Today, the city still retains its old importance as an ecclesiastical centre, and its industrial and commercial development has been limited. The centre of the city retains an unspoilt charm with over 230 [[Listed buildings in Lichfield|listed buildings]] in its historic streets, fine [[Georgian architecture]] and old cultural traditions. People from Lichfield are known as Lichfeldians. |

|||

The origin of the modern name "Lichfield" is twofold. At [[Wall, Staffordshire|Wall]], {{convert|3.5|km|mi|abbr=on}} south of the current city, there was a [[Romano-British culture|Romano-British]] village, [[Letocetum]], a [[Common Brittonic]] place-name meaning "Grey wood", "[[grey]]" perhaps referring to varieties of tree prominent in the landscape, such as [[ash tree|ash]] and [[elm]].<ref>{{cite book|title=Lichfield: The place and street names, population and boundaries ', A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14: Lichfield|year=1990|pages=37–42|url=http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42340|access-date=22 November 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110526054813/http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42340|archive-date=26 May 2011|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://kepn.nottingham.ac.uk/map/place/Staffordshire/Lichfield |title=Lichfield |work=Key to English Place Names |publisher=Institute for Name Studies, [[University of Nottingham]] |access-date=12 May 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304063744/http://kepn.nottingham.ac.uk/map/place/Staffordshire/Lichfield |archive-date=4 March 2016 |url-status=dead |df=dmy-all }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Coates |first1=Richard |title=Celtic Voices, English Places: Studies of the Celtic Impact on Place-Names in Britain |last2=Breeze |first2=Andrew |publisher=Tyas |year=2000 |isbn=1900289415 |location=Stamford}}.</ref>{{rp|335}} In the post-Roman period, ''Letocetum'' developed into Old Welsh {{lang|owl|Luitcoyt}}.<ref name="Sims">{{cite book |author=Patrick Sims-Williams |author-link=Dating the Transition to Neo-Brittonic: Phonology and History, 400-600 |title=Britain 400–600: Language and History |publisher=Carl Winter Universitätsverlag |year=1990 |isbn=3-533-04271-5 |editor=Alfred Bammesberger |location=Heidelberg |page=260 |chapter=2}}</ref> |

|||

The earliest record of the name in English is the ''[[Vita Sancti Wilfrithi|Vita Sancti Wilfredi]]'' of around 715, describing when [[Chad of Mercia|Chad]] moves from York to Lichfield in 669. "Chad was made Bishop of the Mercians immediately after his deposition; Wilfred gave him the place (''locus'') at Lichfield (''Onlicitfelda'')".<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Sargent |first=Andrew |title=Lichfield and the Lands of St Chad |date=2020 |publisher=University of Hertfordshire Press |isbn=978-1-912260-24-9 |pages=Pages 90, 264 |language=English}}</ref> The prefix "on" indicates that the place given to Chad by Wilfrid was "in Lichfield", indicating the name was understood to apply to a region rather than a specific settlement.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Johnson |first=Douglas |title=VCH Staffordshire |publisher=Greenslade |edition=Volume 14, page 38}}</ref><ref>Hanks, Patrick; Hodges, Flavia (2002). ''The Oxford Names Companion''. Oxford University Press; p. 1107. {{ISBN|0198605617}}</ref> Bede's ''Ecclesiastical History of the English People'', completed in 731, states that Chad acquired ''Licidfelth'' as his episcopal seat (''sedes episcolpalem'').<ref name=":1">{{Cite book |title=The Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names, Based on the Collections of the English Place-Name Society |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2004 |isbn=9780521168557 |editor-last=Watts |editor-first=Victor |location=Cambridge}}, s.v. ''Lichfield''.</ref> |

|||

== Etymology == |

|||

The origin of the modern name "Lichfield" is twofold. At [[Wall, Staffordshire|Wall]], {{convert|3.5|km|mi|abbr=on}} south of the current city, there was a [[Romano-British culture|Romano-British]] village, [[Letocetum]], a [[Common Brittonic]] place name meaning "Greywood", "grey" perhaps referring to varieties of tree prominent in the landscape such as ash and elm.<ref>{{cite book|title=Lichfield: The place and street names, population and boundaries ', A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14: Lichfield|year=1990|pages=37–42|url=http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42340}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://kepn.nottingham.ac.uk/map/place/Staffordshire/Lichfield | title = Lichfield | work=Key to English Place Names | publisher = Institude for Name Studies, [[University of Nottingham]]|accessdate=12 May 2012}}</ref> This passed into [[Old English]] as ''Lyccid'',<ref name=Delamarre>{{cite book|last=Delamarre|first=Xavier|title=Noms de lieux celtiques de l'europe ancienne (-500/+500): Dictionnaire|year=2012|publisher=Éditions Errance|location=Arles, France|isbn=978-2-87772-483-8|page=175}}</ref> cf. {{lang-owl|Luitcoyt}},<ref name=Sims>{{cite book|title=Britain 400-600: Language and History|year=1990|publisher=Carl Winter Universitätsverlag|location=Heidelberg|isbn=3-533-04271-5|page=260|author=Patrick Sims-Williams|authorlink=Dating the Transition to Neo-Brittonic: Phonology and History, 400-600|editor=Alfred Bammesberger|chapter=2}}</ref> to which was appended {{lang-ang|feld}} "open country". This word {{lang|ang|Lyccidfeld}} is the origin of the word "Lichfield".<ref name=Delamarre /> |

|||

These and later sources show that the name ''Letocetum'' had passed into [[Old English]] as ''Licid'',<ref name="Delamarre">{{cite book|last=Delamarre|first=Xavier|title=Noms de lieux celtiques de l'europe ancienne (-500/+500): Dictionnaire|year=2012|publisher=Éditions Errance|location=Arles, France|isbn=978-2-87772-483-8|page=175}}</ref> to which was appended the Old English word {{lang|ang|feld}} ("open country"). This word {{lang|ang|Lyccidfeld}} is the origin of the word "Lichfield".<ref name="Delamarre" /><ref name=":1" /> |

|||

Popular etymology has it that a thousand Christians were martyred in Lichfield around 300 AD during the reign of [[Diocletian]] and that the name Lichfield actually means "field of the dead" (see ''[[lich]]''). There is no evidence to support this legend.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42340|title=Explaining the origin of the 'field of the dead' legend |publisher= British History Online |accessdate=20 November 2008}}</ref> |

|||

The modern day city of Lichfield and the Roman villa of Letocetum are just two miles (3 km) apart. While these names are distinct in modern usage, they had a common derivation in the Brittonic original *''Letocaiton'', indicating that "grey wood" referred to the region inclusive of modern-day Lichfield City and the Roman villa.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

[[Popular etymology]] has it that a thousand Christians were martyred in Lichfield around AD 300 during the reign of [[Diocletian]] and that the name Lichfield actually means "field of the dead" (see ''[[lich]]''). There is no evidence to support this legend.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42340|title=Explaining the origin of the 'field of the dead' legend|publisher=British History Online|access-date=20 November 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110526054813/http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42340|archive-date=26 May 2011|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

== History == |

== History == |

||

{{More citations needed|section|date=November 2024}} |

|||

=== Prehistory and antiquity === |

=== Prehistory and antiquity === |

||

{{Main|Letocetum}} |

{{Main|Letocetum}} |

||

The earliest evidence of settlement is [[Mesolithic]] flints discovered on the high ground of the cemetery at [[St Michael on Greenhill, Lichfield|St Michael on Greenhill]], which may indicate an early flint industry. Traces of [[Neolithic]] settlement have been discovered on the south side of the sandstone ridge occupied by [[Lichfield Cathedral]].<ref name=staf>{{Citation | last =Greenslade | first =M.W. | title =A History of the County of Stafford: Volume XIV: Lichfield| publisher = Victoria County History| year =1990 | isbn =978-0-19-722778-7 }}</ref> |

|||

{{convert|2.2|mi|km|abbr=on}} south-west of Lichfield, near the point where [[Icknield Street]] crosses [[Watling Street]], was the site of Letocetum (the [[Common Brittonic|Brittonic]] *Lētocaiton, "Greywood"). Established in AD 50 as a [[Roman Empire|Roman]] military fortress, it had become a civilian settlement ([[vicus]]) with a bath house and a [[mansio]] by the 2nd century.<ref name=staf/> Letocetum fell into decline by the 4th century and the Romans had left by the 5th century. There have been scattered Romano-British finds in Lichfield and it is possible that a burial discovered beneath the cathedral in 1751 was Romano-British.<ref name=staf/> There is no evidence of what happened to Letocetum after the Romans left; however, Lichfield may have emerged as the inhabitants of Letocetum relocated during its decline. A {{nowrap|Cair Luit Coyd}} ("[[Caer|Fort]] Greywood") was listed by [[Nennius]] among the 28 cities of [[Sub-Roman Britain|Britain]] in his ''[[Historia Brittonum]]'',<ref>[[Nennius]] ({{abbr|attrib.|Traditional attribution}}). [[Theodor Mommsen]] ({{abbr|ed.|Editor}}). [[s:la:Historia Brittonum#VI. CIVITATES BRITANNIAE|''Historia Brittonum'', VI.]] Composed after AD 830. {{in lang|la}} Hosted at [[s:la:Main Page|Latin Wikisource]].</ref> although these were largely historic remembrances of early [[Sub-Roman Britain]]. |

|||

The earliest evidence of settlement has been the discovery of [[Mesolithic]] flints on the high ground of the cemetery at [[St Michael on Greenhill, Lichfield|St Michael on Greenhill]], which may indicate an early flint industry. Traces of [[Neolithic]] settlement have been discovered on the south side of the sandstone ridge occupied by [[Lichfield Cathedral]].<ref name=staf>{{Citation | last =Greenslade | first =M.W. | authorlink = | title =A History of the County of Stafford: Volume XIV: Lichfield|edition= | publisher = Victoria County History| year =1990 | location = | page = | isbn =978-0-19-722778-7 }}</ref> |

|||

{{convert|2.2|mi|km|abbr=on}} southwest of Lichfield, near the point where [[Icknield Street]] crosses [[Watling Street]] was the site of Letocetum. Established in 50 AD as a military fortress, by the 2nd century it had become a civilian settlement with a bath house and a [[mansio]].<ref name=staf/> Letocetum fell into decline by the 4th century and the Romans had left by the 5th century. There have been scattered Romano-British finds in Lichfield and it is possible that a burial discovered beneath the cathedral in 1751 was Romano-British.<ref name=staf/> There is no evidence of what happened to Letocetum after the Romans left; however Lichfield may have emerged as the inhabitants of Letocetum relocated during its decline. |

|||

=== Middle Ages === |

=== Middle Ages === |

||

[[File: |

[[File:The West Front, Lichfield Cathedral - Anon - circa 1830.jpg|thumb|The three-spired [[Lichfield Cathedral]] was built between 1195 and 1249]] |

||

[[File:St Michael's Churchyard 1840.jpg|thumb|St Michael's Churchyard 1840]] |

|||

The early history of Lichfield is obscure. The first authentic record of Lichfield occurs in [[Bede]]'s history, where it is called ''Licidfelth'' and mentioned as the place where [[Chad of Mercia|St Chad]] fixed the [[episcopal see]] of the Mercians in 669. The first [[Christian]] king of [[Mercia]], [[Wulfhere of Mercia|Wulfhere]], donated land at Lichfield for St Chad to build a monastery. It was because of this that the ecclesiastical centre of Mercia became settled as the [[Diocese of Lichfield]], which was approximately {{convert|7|mi|km|0}} northwest of the seat of the Mercian kings at [[Tamworth, Staffordshire|Tamworth]]. |

|||

The early history of Lichfield is obscure. The first authentic record of Lichfield occurs in [[Bede|Bede's]] history, where it is called ''Licidfelth'' and mentioned as the place where [[Chad of Mercia|St Chad]] fixed the [[episcopal see]] of the Mercians in 669. The first [[Christians|Christian]] king of [[Mercia]], [[Wulfhere of Mercia|Wulfhere]], donated land at Lichfield for St Chad to build a monastery. It was because of this that the ecclesiastical centre of Mercia became settled as the [[Diocese of Lichfield]], which was approximately {{convert|7|mi|km|0}} northwest of the seat of the Mercian kings at [[Tamworth, Staffordshire|Tamworth]]. |

|||

In July 2009, the [[Staffordshire Hoard]], the largest collection of [[Anglo-Saxon]] gold ever found, was discovered in a field in the parish of [[Hammerwich]], {{convert|4|mi|km|1|abbr=on}} south-west of Lichfield; it was probably deposited in the 7th century. |

|||

The first cathedral was built on the present site in 700 when Bishop [[Hædde]] built a new church to house the bones of St Chad, which had become the centre of a sacred shrine to many pilgrims when he died in 672. The burial in the cathedral of the kings of Mercia, Wulfhere in 674 and [[Ceolred of Mercia|Ceolred]] in 716, further increased the city's prestige.<ref name="british-history.ac.uk">From: 'Lichfield: History to c.1500', A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14: Lichfield (1990), pp. 4–14. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42336 {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121021214211/http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42336 |date=21 October 2012 }} Date accessed: 24 July 2009.</ref> In 786 King [[Offa of Mercia|Offa]] made the city an archbishopric with authority over all the bishops from the [[Humber]] to the [[River Thames]]; his appointee was Archbishop [[Hygeberht]]. This may have been motivated by Offa's desire to have an archbishop consecrate his son [[Ecgfrith of Mercia|Ecgfrith]] as king, since it is possible [[Jænberht]] refused to perform the ceremony, which took place in 787. After King Offa's death in 796, Lichfield's power waned; in 803 the primacy was restored to Canterbury by [[Pope Leo III]] after only 16 years. |

|||

The ''[[Historia Brittonum]]'' lists the city as one of the 28 cities of Britain around AD 833. |

|||

During the 9th century, Mercia was devastated by Danish [[Vikings]]. Lichfield itself was unwalled and the cathedral was despoiled, so [[Peter of Lichfield|Bishop Peter]] moved the see to the fortified and wealthier [[Chester]] in 1075. At the time of the [[Domesday Book]] survey (1086), Lichfield was held by the [[bishop of Chester]]; Lichfield was listed as a small village. The lord of the manor was the Bishop of Chester until the reign of [[Edward VI of England|Edward VI]].[[File:Staffordshire hoard annotated.jpg|thumb|right|The [[Staffordshire Hoard]] was discovered in a field near Lichfield]] In 1102 Bishop Peter's successor, [[Robert de Limesey]], transferred the see from Chester to Coventry. The Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield had seats in both locations; work on the present Gothic cathedral at Lichfield began in 1195. (In 1837 the see of Lichfield acquired independent status, and the style 'Bishop of Lichfield' was adopted.) |

|||

In 1153 a markets charter was granted by King Stephen and, ever since, weekly markets have been held in the Market Square.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Markets - Lichfield City Council |url=https://www.lichfield.gov.uk/Markets_702.aspx#:~:text=Lichfield%20Markets&text=In%20the%201550%27s,%20during%20the,so%20to%20die%20in%20England. |access-date=2023-03-16 |website=www.lichfield.gov.uk}}</ref> |

|||

The first cathedral was built on the present site in 700 when Bishop [[Hædde]] built a new church to house the bones of St Chad, which had become the centre of a sacred shrine to many pilgrims when he died in 672. The burial in the cathedral of the kings of Mercia, Wulfhere in 674 and [[Ceolred of Mercia|Ceolred]] in 716, further increased the city's prestige.<ref name="british-history.ac.uk">From: 'Lichfield: History to c.1500', A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14: Lichfield (1990), pp. 4-14. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42336 Date accessed: 24 July 2009.</ref> In 786 King [[Offa of Mercia|Offa]] made the city an archbishopric with authority over all the bishops from the [[Humber]] to the [[River Thames]]; his appointee was Archbishop [[Hygeberht]]. After King Offa's death in 796, Lichfield's power waned; in 803 the primacy was restored to Canterbury by [[Pope Leo III]] after only 16 years. |

|||

[[File:Lichfield Cathedral 2010-10-13.jpg|thumb|Lichfield Cathedral in modern times.]] |

|||

The [[Historia Brittonum]] lists the city as one of the 28 cities of Britain around AD 833. |

|||

Bishop [[Roger de Clinton]] was responsible for transforming the scattered settlements to the south of Minster Pool into the ladder-plan streets existing today. Market Street, Wade Street, Bore Street and Frog Lane linked Dam Street, Conduit Street and Bakers Lane on one side with Bird Street and St John Street on the other. Bishop de Clinton also fortified the cathedral close and enclosed the town with a bank and ditch, and gates were set up where roads into the town crossed the ditch.<ref name="british-history.ac.uk"/> In 1291 Lichfield was severely damaged by a fire which destroyed most of the town; however the Cathedral and Close survived unscathed.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.localhistories.org/lichfield.html|title=Brief History of Lichfield|publisher=Local Histories|access-date=20 November 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081229164653/http://www.localhistories.org/lichfield.html|archive-date=29 December 2008|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

During the 9th century, Mercia was devastated by Danish [[Vikings]]. Lichfield itself was unwalled and the cathedral was despoiled, so [[Peter of Lichfield|Bishop Peter]] moved the see to the fortified and wealthier [[Chester]] in 1075.[[File:Staffordshire hoard annotated.jpg|thumb|right|The [[Staffordshire Hoard]] was discovered in a field near Lichfield]] His successor, [[Robert de Limesey]], transferred it to Coventry but it was eventually restored to Lichfield in 1148. Work began on the present Gothic cathedral in 1195. At the time of the [[Domesday Book]] survey, Lichfield was held by the [[bishop of Chester]], where the see of the bishopric had been moved 10 years earlier; Lichfield was listed as a small village. The lord of the manor was the bishop of Chester until the reign of [[Edward VI of England|Edward VI]]. |

|||

Bishop [[Roger de Clinton]] was responsible for transforming the scattered settlements to the south of Minster Pool into the ladder-plan streets existing today. Market Street, Wade Street, Bore Street and Frog Lane linked Dam Street, Conduit Street and Bakers Lane on one side with Bird Street and St John Street on the other. Bishop de Clinton also fortified the cathedral close and enclosed the town with a bank and ditch, and gates were set up where roads into the town crossed the ditch.<ref name="british-history.ac.uk"/> In 1291 Lichfield was severely damaged by a fire which destroyed most of the town; however the Cathedral and Close survived unscathed.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.localhistories.org/lichfield.html|title=Brief History of Lichfield |publisher= Local Histories|accessdate=20 November 2008}}</ref> |

|||

In 1387 [[Richard II of England|Richard II]] gave a charter for the foundation of the |

In 1387 [[Richard II of England|Richard II]] gave a charter for the foundation of the guild of St Mary and St John the Baptist; this guild functioned as the local government, until its dissolution by [[Edward VI of England|Edward VI]], who incorporated the town in 1548. |

||

=== Early Modern === |

=== Early Modern === |

||

[[File:John Snape Lichfield Plan.jpg|thumb|left|Map of Lichfield in 1781]] |

[[File:John Snape Lichfield Plan.jpg|thumb|left|Map of Lichfield in 1781]] |

||

The policies of [[Henry VIII of England|Henry VIII]] had a dramatic effect on Lichfield. The [[English Reformation|Reformation]] brought the disappearance of pilgrim traffic following the destruction of St Chad's shrine in 1538 which was a major loss to the city's economic prosperity. That year too the [[The Franciscan Friary, Lichfield|Franciscan Friary]] was dissolved, the site becoming a private estate. Further economic decline followed the outbreak of [[Black Death|plague]] in 1593, which resulted in the death of over a third of the entire population.<ref>{{cite web |

The policies of [[Henry VIII of England|Henry VIII]] had a dramatic effect on Lichfield. The [[English Reformation|Reformation]] brought the disappearance of [[pilgrim]] traffic following the destruction of St Chad's shrine in 1538, which was a major loss to the city's economic prosperity. That year too the [[The Franciscan Friary, Lichfield|Franciscan Friary]] was dissolved, the site becoming a private estate. Further economic decline followed the outbreak of [[Black Death|plague]] in 1593, which resulted in the death of over a third of the entire population.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42337|title='Lichfield: From the Reformation to c.1800', A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14: Lichfield (1990), pp. 14-24.|publisher=British History Online|access-date=22 November 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110526054843/http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42337|archive-date=26 May 2011|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

Three people were burned at the stake for [[heresy]] under Mary I. The last public burning at the stake in England took place in Lichfield, when [[Edward Wightman]] from [[Burton upon Trent]] was [[Execution by burning|executed by burning]] in the Market Place on 11 April 1612 for |

Three people were burned at the stake for [[heresy]] under Mary I. The last public burning at the stake for heresy in England took place in Lichfield, when [[Edward Wightman]] from [[Burton upon Trent]] was [[Execution by burning|executed by burning]] in the Market Place on 11 April 1612 for promoting himself as the divine [[Paraclete]] and Saviour of the world.<ref name="DNB">{{cite DNB |wstitle= Wightman, Edward |volume= 61 |last= Gordon |first= Alexander |author-link= Alexander Gordon (Unitarian) |pages= 195-196 |short= 1}}</ref><ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=9AxAAAAAYAAJ&dq=%22Edward+Wightman%22+treason&pg=PT379 Cobbett's complete collection of state trials and proceedings] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160503213240/https://books.google.com/books?id=9AxAAAAAYAAJ&pg=PT379&lpg=PT379&dq=%22Edward+Wightman%22+treason&source=bl&ots=4iNNPt1Fb1&sig=rhZEDpVPZoGMvaYAwawtyuf5nFg&hl=en&ei=K5txTIvhMcKB8gaQzsCtDQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBYQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=%22Edward%20Wightman%22%20treason&f=false |date=3 May 2016 }}, 735–736.</ref> |

||

[[File: |

[[File:Dr-Johnson.jpg|thumbnail|upright|200px|[[Samuel Johnson]] was born in Breadmarket Street in 1709]] |

||

[[File:Samuel Johnson Statue.jpg|thumb|200px|Statue of Dr Johnson in Lichfield's Market Square<br />"The Doctor's statue, which is of some inexpensive composite painted a shiny brown, and of no great merit of design, fills out the vacant dulness of the little square in much the same way as his massive personality occupies—with just a margin for [[David Garrick|Garrick]]—the record of his native town."—[[Henry James]], ''Lichfield and Warwick'', 1872]] |

|||

[[File:Cockle Lucas Johnson.jpg|thumb|200px|Photograph by [[Richard Cockle Lucas]] (sculptor) of Johnson statue taken in 1859]] |

|||

In the [[English Civil War]], Lichfield was divided. The cathedral authorities, |

In the [[English Civil War]], Lichfield was divided. The cathedral authorities, supported by some of the townsfolk, were for the king, but the townsfolk generally sided with the Parliament. This led to the fortification of the close in 1643. Lichfield's position as a focus of supply routes had an important strategic significance during the war, and both forces were anxious for control of the city. The Parliamentary commander [[Robert Greville, 2nd Baron Brooke|Lord Brooke]] led an assault on the fortified close, but was killed by a deflected bullet on St Chad's day in 1643, an accident welcomed as a miracle by the Royalists. The close subsequently yielded to the Parliamentarians, but was retaken by [[Prince Rupert of the Rhine]] in the same year; on the collapse of the Royalist cause in 1646 it again surrendered. The cathedral suffered extensive damage from the war, including the complete destruction of the central spire. It was restored at the Restoration under the supervision of [[John Hacket|Bishop Hacket]], and thanks in part to the generosity of [[King Charles II of England|King Charles II]]. |

||

Lichfield started to develop a lively coaching trade as a stop-off on the busy route between London and [[Chester]] from the 1650s onwards, making it Staffordshire's most prosperous town. In the 18th century, and reaching its peak in the period from |

Lichfield started to develop a lively coaching trade as a stop-off on the busy route between London and [[Chester]] from the 1650s onwards, making it Staffordshire's most prosperous town. In the 18th century, and then reaching its peak in the period from 1800 to 1840, the city thrived as a busy coaching city on the main routes from London to the north-west and Birmingham to the north-east. It also became a centre of great intellectual activity, being the home of many famous people including [[Samuel Johnson]], [[David Garrick]], [[Erasmus Darwin]] and [[Anna Seward]]; this prompted Johnson's remark that Lichfield was "a city of philosophers". In the 1720s [[Daniel Defoe]] described Lichfield as 'a fine, neat, well-built, and indifferent large city', the principal town in the region after Chester.<ref name="From 1990 pp. 14-24">From: 'Lichfield: From the Reformation to c.1800', A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14: Lichfield (1990), pp. 14-24. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42337 {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110526054843/http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42337 |date=26 May 2011 }} Date accessed: 24 July 2009.</ref> During the late 18th and early 19th century much of the medieval city was rebuilt with the red-brick [[Georgian architecture|Georgian style]] buildings still to be seen today. Also during this time, the city's infrastructure underwent great improvements, with underground sewerage systems, paved streets and gas-powered street lighting.<ref name=clay>{{Citation | last =Clayton | first =Howard | title =Coaching City| publisher = Abbotsford Publishing| year =1981 | isbn =978-0-9503563-1-0}}</ref> An infantry regiment of the [[British Army]] was formed at Lichfield in 1705 by Col. [[Luke Lillingstone]] in the King's Head tavern in Bird Street. In 1751 it became the 38th Regiment of Foot, and in 1783 the 1st [[Staffordshire Regiment]]; after reorganisation in 1881 it became the 1st battalion of the [[South Staffordshire Regiment]].<ref name="From 1990 pp. 14-24"/> |

||

=== Late Modern and contemporary === |

=== Late Modern and contemporary === |

||

The arrival of the [[Industrial Revolution]] and the railways in 1837 signalled the end of Lichfield's position as an important staging post for coaching traffic. |

The arrival of the [[Industrial Revolution]] and the railways in 1837 signalled the end of Lichfield's position as an important staging post for coaching traffic. While nearby Birmingham (and its population) expanded greatly during the Industrial Revolution, Lichfield remained largely unchanged in character. |

||

The first council houses were built in the Dimbles area of the city in the 1930s. The outbreak of [[World War II]] brought over 2,000 [[Evacuations of civilians in Britain during World War II|evacuees]] from industrialised areas. However, due to the lack of heavy industry in the city, Lichfield escaped lightly, although there were [[strategic bombing|air raids]] in 1940 and 1941 and |

The first council houses were built in the Dimbles area of the city in the 1930s. The outbreak of [[World War II]] brought over 2,000 [[Evacuations of civilians in Britain during World War II|evacuees]] from industrialised areas. However, due to the lack of heavy industry in the city, Lichfield escaped lightly, although there were [[strategic bombing|air raids]] in 1940 and 1941 and three Lichfeldians were killed. Just outside the city, [[Wellington Bomber]]s flew out of Fradley Aerodrome, which was known as [[RAF Lichfield]]. After the war the council built many new houses in the 1960s, including some high-rise flats, while the late 1970s and early 1980s saw the construction of a large housing estate at Boley Park in the south-east of the city. The city's population tripled between 1951 and the late 1980s. |

||

The city has continued expanding to the west. The Darwin Park housing estate has been under development for a number of years and has swelled the city's population by approximately 3,000. Plans |

The city has continued expanding to the west. The Darwin Park housing estate has been under development for a number of years and has swelled the city's population by approximately 3,000. Plans were approved for Friarsgate, a new £100 million shopping and leisure complex opposite [[Lichfield City Station]]. The police station, bus station, Ford garage and multi-storey car park were to be demolished to make way for 22,000 m<sup>2</sup> of retail space and 2,000 m<sup>2</sup> of leisure facilities, consisting of a flagship department store, six-screen cinema, hotel, 37 individual shops and 56 flats.<ref name=ldcfp>{{Citation| url = http://www.lichfielddc.gov.uk/site/scripts/documents_info.php?documentID=1328| title = Lichfield District Council:Friarsgate Plans| access-date = 26 January 2011| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20110928030819/http://www.lichfielddc.gov.uk/site/scripts/documents_info.php?documentID=1328| archive-date = 28 September 2011| url-status = dead| df = dmy-all}}</ref> These plans have not gone ahead<ref>{{Cite web|title=Meeting told building new Lichfield leisure centre on site of failed Friarsgate scheme would be too costly|url=https://lichfieldlive.co.uk/2020/09/25/meeting-told-building-new-lichfield-leisure-centre-on-site-of-failed-friarsgate-scheme-would-be-too-costly/|website=Lichfield Live|date=25 September 2020}}</ref> and new plans have been made for a cinema in the abandoned [[Debenhams]] building.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Kerr |first=Andrew |title=Lichfield District Council approves investment in long-awaited multi-screen cinema for the district. |url=https://www.lichfielddc.gov.uk/news/article/663/lichfield-district-council-approves-investment-in-long-awaited-multi-screen-cinema-for-the-district- |access-date=2023-03-16 |website=Lichfield District Council |language=en}}</ref> |

||

== Governance == |

== Governance == |

||

=== Local government === |

=== Local government === |

||

Historically the [[Bishop of Lichfield]] had authority over the city. It was not until 1548 with Edward VI's charter that Lichfield had |

Historically the [[Bishop of Lichfield]] had authority over the city. It was not until 1548, with [[Edward VI]]'s charter, that Lichfield had any form of secular government. As a reward for the support given to Mary I by the bailiffs and citizens during the Duke of Northumberland's attempt to prevent her accession, the Queen issued a new charter in 1553, confirming the 1548 charter and in addition granting the city its own Sheriff. The same charter made Lichfield a county separate from the rest of [[Staffordshire]]. It remained so until 1888. |

||

The City Council (not to be confused with [[Lichfield District Council]], which has authority over a wider area than Lichfield city) has 28 members from the |

The City Council (not to be confused with [[Lichfield District Council]], which has authority over a wider area than Lichfield city) has 28 members (from the nine wards of Boley Park, Burton Old Road West, Chadsmead, Curborough, Garrick Road, Leamonsley, St John's, Pentire Road and Stowe), who are elected every four years. After the 2019 parish council elections,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.lichfield.gov.uk/Councillors_739.aspx|title = Councillors - Lichfield City Council}}</ref> the [[Conservative Party (UK)|Conservatives]] remained in overall control, with the 28 seats being divided between the Conservatives (16), [[Liberal Democrats (UK)|the Liberal Democrats]] (8), [[Labour Party (UK)|Labour]] (3) and Independent (1) who subsequently joined the Labour group. The [[Worship (style)|Right Worshipful]] the [[Mayor]] of Lichfield (currently Councillor Robert Yardley<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.lichfield.gov.uk/Mayors_Sheriffs_and_Town_Clerks_since_1548_740.aspx|title=Mayors, Sheriffs and Town Clerks since 1548 - Lichfield City Council|website=www.lichfield.gov.uk}}</ref>) is the civic head of the council<ref name="lichfield.gov.uk">{{cite web |url=http://www.lichfield.gov.uk/cc-structure.ihtml |title=Lichfield City Council Officers and Structure |access-date=2012-06-22 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120715073152/http://www.lichfield.gov.uk/cc-structure.ihtml |archive-date=15 July 2012 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> and chairs council meetings. The council also appoints a Leader of Council to be the main person responsible for leadership of the council's political and policy matters. The council's current Leader is [[Councillor]] Mark Warfield. Lichfield is one of only 15 towns and cities in England and Wales which appoints a [[High Sheriff|Sheriff]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.lichfield.gov.uk/cc.ihtml |title=Lichfield City Council Functions |publisher=Lichfield.gov.uk |access-date=17 July 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100423113052/http://www.lichfield.gov.uk/cc.ihtml |archive-date=23 April 2010 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> |

||

=== Members of Parliament === |

=== Members of Parliament === |

||

The [[Lichfield (UK Parliament constituency)|Lichfield constituency]] sent two members to the parliament of 1304 and to a few succeeding parliaments, but the representation did not become regular until 1552; in 1867 it lost one member, and in 1885 its representation was merged into that of the county.<ref name="From 1990 pp. 14-24"/> The Lichfield constituency was abolished in 1950 and replaced with the [[Lichfield and Tamworth (UK Parliament constituency)|Lichfield and Tamworth constituency]]. This constituency lasted until 1983 when it was replaced with the [[Mid Staffordshire (UK Parliament constituency)|Mid Staffordshire constituency]]. |

The [[Lichfield (UK Parliament constituency)|Lichfield constituency]] sent two members to the parliament of 1304 and to a few succeeding parliaments, but the representation did not become regular until 1552; in 1867 it lost one member, and in 1885 its representation was merged into that of the county.<ref name="From 1990 pp. 14-24"/> The Lichfield constituency was abolished in 1950 and replaced with the [[Lichfield and Tamworth (UK Parliament constituency)|Lichfield and Tamworth constituency]]. This constituency lasted until 1983, when it was replaced with the [[Mid Staffordshire (UK Parliament constituency)|Mid Staffordshire constituency]]. |

||

Based on the resident's location in Lichfield District, there are technically two MPs. The current Member of Parliament for Lichfield, including the whole of the city, is the Labour Politician [[Dave Robertson (British politician)|Dave Robertson]], who has been MP for Lichfield since the [[2024 United Kingdom general election|2024 general election]]. Robertson won the seat from Conservative [[Michael Fabricant]], who had held the seat since 1997, by a majority of 810.<ref>https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/election/2024/uk/constituencies/E14001335</ref> |

|||

The current Member of Parliament for Lichfield is the Conservative [[Michael Fabricant]], who has been MP for Lichfield since 1997. Fabricant was first elected for the [[Mid Staffordshire (UK Parliament constituency)|Mid Staffordshire constituency]] in [[United Kingdom general election, 1992|1992]], regaining the seat for the Conservatives following [[Sylvia Heal|Sylvia Heal's]] victory for [[Labour Party (UK)|Labour]] at the [[Mid Staffordshire by-election, 1990|1990 by-election]]. Fabricant took the seat with a majority of 6,236 and has remained a Member of Parliament since. The Mid Staffordshire seat was abolished at the [[United Kingdom general election, 1997|1997 general election]], but Fabricant contested and won the Lichfield constituency, which partially replaced it, by just 238 votes. He has remained the Lichfield MP since, increasing his majority to 4,426 in [[United Kingdom general election, 2001|2001]], 7,080 in [[United Kingdom general election, 2005|2005]] and 17,683 in [[United Kingdom general election, 2010|2010]]. |

|||

[[Sarah Edwards (British politician)|Sarah Edwards]] was elected to the [[Tamworth (UK Parliament constituency)|Tamworth constituency]] in a [[2023 Tamworth by-election|byelection in 2023]]<ref name="bbc2023">{{cite news |title=Labour overturn 19,000 Tory majority for 'incredible' Tamworth win |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-67165541 |access-date=20 October 2023 |work=BBC News |date=20 October 2023}}</ref> and held the seat in the 2024 general election.<ref>https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/election/2024/uk/constituencies/E14001538</ref> [[Chris Pincher|Christopher Pincher]] was the previous MP until a [[Chris Pincher scandal|highly publicised scandal]] in 2022 after which he had the Conservative [[Whip (politics)|whip]] revoked and subsequently sat as an [[Independent politician|independent]] before announcing his resignation in September 2023. |

|||

==Geography== |

==Geography== |

||

Lichfield covers an area of approximately {{convert|5.41|sqmi|km2|abbr=on}} in the south |

Lichfield covers an area of approximately {{convert|5.41|sqmi|km2|abbr=on}} in the south-east of the county of Staffordshire in the West Midlands region of England. It is approximately {{convert|27|km|mi|abbr=on}} north of Birmingham and {{convert|200|km|mi|abbr=on}} north-west of London. The city is located between the high ground of [[Cannock Chase]] to the west and the valleys of the Rivers [[River Trent|Trent]] and [[River Tame, West Midlands|Tame]] to the east. It is underlain by red [[sandstone]], deposited during the arid desert conditions of the [[Triassic]] period. [[Keuper marl|Mercia Mudstone]] underlies the north and north-eastern edges of the city towards [[Curborough and Elmhurst|Elmhurst and Curborough]]. The red sandstone underlying the majority of Lichfield is present in many of its ancient buildings, including Lichfield Cathedral and the [[The Church of St Chad, Lichfield|Church of St Chad]].<ref name=bgs>{{Citation|url=http://maps.bgs.ac.uk/geologyviewer_google/googleviewer.html |title=British Geological Survey:Geology of Britain viewer |access-date=20 January 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110727004018/http://maps.bgs.ac.uk/geologyviewer_google/googleviewer.html |archive-date=27 July 2011 }}</ref> |

||

The ground within the city slopes down from 116m in the north |

The ground within the city slopes down from 116m in the north-west to 86m on the sandstone shelf where Lichfield Cathedral stands. To the south and east of the city centre is a ridge which reaches 103 m at [[St Michael on Greenhill, Lichfield|St Michael on Greenhill]]. Boley Park lies on top of a ridge with its highest point on Borrowcop Hill at 113m. To the south-east the level drops to 69 m where Tamworth Road crosses the city boundary into Freeford. There is another high ridge south-west of the city where there are two high points, one at Berry Hill Farm at 123 m and the other on Harehurst Hill near the city boundary at Aldershawe where the level reaches 134 m.<ref name=osmap>{{Citation| url = http://www.bing.com/maps/?FORM=MUKMMP&PUBL=Google&mkt=en-GB&crea=userid2508go2d31d19252d0b114ed487e8ed62ff0c8#JnE9LndzMTQrOWVqJTdlc3N0LjAlN2VwZy4xJmJiPTU2LjY0NzIyMTE5MTgxODYlN2UxMC4xNzMzMzk4NDM3NSU3ZTQ1LjcyNTQyNDg5MzQ3NzYlN2UtMTAuMTczMzM5ODQzNzU=| title = Ordnance Survey Map:Lichfield| access-date = 20 January 2011| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20110122184131/http://www.bing.com/maps/?FORM=MUKMMP&PUBL=Google&mkt=en-GB&crea=userid2508go2d31d19252d0b114ed487e8ed62ff0c8#JnE9LndzMTQrOWVqJTdlc3N0LjAlN2VwZy4xJmJiPTU2LjY0NzIyMTE5MTgxODYlN2UxMC4xNzMzMzk4NDM3NSU3ZTQ1LjcyNTQyNDg5MzQ3NzYlN2UtMTAuMTczMzM5ODQzNzU=| archive-date = 22 January 2011| url-status = live}}</ref> |

||

The city is built on the two sides of a shallow valley, into which flow two streams from the west, the Trunkfield Brook and the Leamonsley Brook, and out of which the Curborough Brook runs to the north |

The city is built on the two sides of a shallow valley, into which flow two streams from the west, the Trunkfield Brook and the Leamonsley Brook, and out of which the Curborough Brook runs to the north-east, eventually flowing into the [[River Trent]]. The two streams have been dammed south of the cathedral on Dam Street to form [[Minster Pool]] and near St Chad's Road to form [[Stowe Pool]].{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

||

{{wide image|Lichfield |

{{wide image|Lichfield Harehurst Hill 2.jpg|770px|Panorama from Harehurst Hill {{convert|1.5|mi|km|1|abbr=on}} south west of the cathedral, showing Lichfield's distinctive 5 spires }} |

||

{{wide image|Lichfield Harehurst Hill 2.jpg|800px|Panorama from Harehurst Hill 1.5 miles south west of the cathedral, showing Lichfield's distinctive 5 spires }} |

|||

=== Suburbs === |

=== Suburbs === |

||

Boley Park | Chadsmead | Christ Church | Darwin Park | The Dimbles | Leamonsley | Nether Stowe | Sandfields | Stowe | Trent Valley |

|||

=== Nearby places === |

|||

Major towns and cities are in upper case, not all nearby villages and hamlets are listed here: |

|||

<!-- {{GBdot|Lichfield}} |

<!-- {{GBdot|Lichfield}} |

||

{{gbmapping|}}--> |

{{gbmapping|}}--> |

||

{{Div col|colwidth=15em}} |

|||

* Boley Park |

|||

* Chadsmead |

|||

* Christ Church |

|||

* Darwin Park |

|||

* The Dimbles |

|||

* Leomonsley |

|||

* Nether Stowe |

|||

* Sandfields |

|||

* Stowe |

|||

* Streethay |

|||

* Trent Valley |

|||

{{Div col end}} |

|||

== Demography == |

|||

{{Geographic location |

|||

|Northwest = [[Longdon, Staffordshire|Longdon]], [[Armitage]], [[Mavesyn Ridware]], [[Rugeley|RUGELEY]], [[Stafford|STAFFORD]] |

|||

|North = [[Elmhurst, Staffordshire|Elmhurst]], [[Curborough and Elmhurst|Curborough]], [[Kings Bromley]], [[Abbots Bromley]], [[Uttoxeter]], [[Ashbourne, Derbyshire|Ashbourne]] |

|||

|Northeast = [[Streethay]], [[Fradley]], [[Alrewas]], [[Croxall]], [[Edingale]], [[Burton upon Trent|BURTON UPON TRENT]], [[Derby|DERBY]] |

|||

|West = [[Hammerwich]], [[Gentleshaw]], [[Cannock Wood]], [[Burntwood]], [[Chasetown]], [[Cannock|CANNOCK]] |

|||

|Centre = Lichfield |

|||

|East = [[Whittington, Staffordshire|Whittington]], [[Fisherwick]], [[Elford]], [[Thorpe Constantine]], [[Appleby Magna]], [[Measham]] |

|||

|Southwest = [[Brownhills]], [[Walsall Wood]], [[Bloxwich]], [[Walsall|WALSALL]], [[Wolverhampton|WOLVERHAMPTON]] |

|||

|South = [[Wall, Staffordshire|Wall]], [[Shenstone, Staffordshire|Shenstone]], [[Sutton Coldfield]], [[Birmingham|BIRMINGHAM]], [[Solihull]] |

|||

|Southeast = [[Swinfen and Packington|Swinfen & Packington]], [[Weeford]], [[Hopwas]], [[Hints, Staffordshire|Hints]], [[Tamworth, Staffordshire|TAMWORTH]], [[Coventry|COVENTRY]] |

|||

}} |

|||

== Demographics == |

|||

At the time of the |

At the time of the 2021 census, the population of the City of Lichfield was 34,738. Lichfield is 96.5% white and 66.5% Christian. 51% of the population over 16 were married. 64% were employed and 21% of the people were retired. All of these figures were higher than the national average.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.lichfield.gov.uk/cc-statistics.ihtml |title=Statistics |publisher=Lichfield |access-date=17 July 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110724162428/http://www.lichfield.gov.uk/cc-statistics.ihtml |archive-date=24 July 2011 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> |

||

{| class="wikitable" style=" |

{| class="wikitable" style="border:0; text-align:center; line-height:120%;" |

||

|+[[Population growth]] of the City of Lichfield since 1685 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! Year |

|||

! style="background:#9cc; color:navy; height:17px;"| Year |

|||

! 1685 |

|||

! style="background:#fff; color:navy;"| 1685 |

|||

! 1781 |

|||

! style="background:#fff; color:navy;"| 1781 |

|||

! 1801 |

|||

! style="background:#fff; color:navy;"| 1801 |

|||

! 1831 |

|||

! style="background:#fff; color:navy;"| 1831 |

|||

! 1901 |

|||

! style="background:#fff; color:navy;"| 1901 |

|||

! 1911 |

|||

! style="background:#fff; color:navy;"| 1911 |

|||

! 1921 |

|||

! style="background:#fff; color:navy;"| 1921 |

|||

! 1931 |

|||

! style="background:#fff; color:navy;"| 1931 |

|||

! 1951 |

|||

! style="background:#fff; color:navy;"| 1951 |

|||

! 1961 |

|||

! style="background:#fff; color:navy;"| 1961 |

|||

! 1971 |

|||

! style="background:#fff; color:navy;"| 1971 |

|||

! 1981 |

|||

! style="background:#fff; color:navy;"| 1981 |

|||

! 1991 |

|||

! style="background:#fff; color:navy;"| 1991 |

|||

! 2001 |

|||

! style="background:#fff; color:navy;"| 2001 |

|||

! style="background:#fff; color:navy;"| |

! 2011 |

||

! style="background:#fff; color:navy;"|2021 |

|||

|- style="text-align:center;" |

|- style="text-align:center;" |

||

! |

! Population |

||

| 3,040 |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 3,040 |

|||

| 3,555 |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 3,555 |

|||

| 4,840 |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 4,840 |

|||

| 6,252 |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 6,252 |

|||

| 7,900 |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 7,900 |

|||

| 8,616 |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 8,616 |

|||

| 8,393 |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 8,393 |

|||

| 8,507 |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 8,507 |

|||

| 10,260 |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 10,260 |

|||

| 14,090 |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 14,090 |

|||

| 22,660 |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 22,660 |

|||

| 25,400 |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 25,400 |

|||

| 28,666 |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 28,666 |

|||

| 27,900 |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 27,900 |

|||

| 32,219 |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 32,219 |

|||

| 34,738 |

|||

|- style="text-align:center;" |

|- style="text-align:center;" |

||

! %± |

|||

! style="background:#9cc; color:navy; height:17px;"| %± |

|||

| - |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| - |

|||

| 16.9% |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 16.9% |

|||

| 36.1% |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 36.1% |

|||

| 29.2% |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 29.2% |

|||

| 26.4% |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 26.4% |

|||

| 9.1% |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 9.1% |

|||

| -2.6% |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| -2.6% |

|||

| 1.35% |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 1.35% |

|||

| 19.1% |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 19.1% |

|||

| 37.3% |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 37.3% |

|||

| 60.8% |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 60.8% |

|||

| 12.1% |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 12.1% |

|||

| 12.9% |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 12.9% |

|||

| -2.7% |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| -2.7% |

|||

| 15.5% |

|||

| style="background:#fff; color:black;"| 15.5% |

|||

| 7.8% |

|||

|- style="text-align:center;" |

|- style="text-align:center;" |

||

|} |

|} |

||

== Economy == |

== Economy == |

||

[[File:tudorcafe.jpg|thumb|The Tudor Café in Bore Street was built in 1510]] |

{{More citations needed|section|date=November 2024}}[[File:tudorcafe.jpg|thumb|The Tudor Café in Bore Street was built in 1510]] |

||

Lichfield's wealth grew along with its importance as an ecclesiastical centre. The original settlement prospered as the place where pilgrims gathered to worship at the shrine of St Chad: this practice continued |

Lichfield's wealth grew along with its importance as an ecclesiastical centre. The original settlement prospered as the place where pilgrims gathered to worship at the shrine of St Chad: this practice continued until the [[English Reformation|Reformation]], when the shrine was destroyed. |

||

In the Middle Ages, the main industry in Lichfield was making woollen cloth |

In the Middle Ages, the main industry in Lichfield was making woollen cloth; there was also a leather industry. Much of the surrounding area was open pasture, and there were many surrounding farms. |

||

In the 18th century, Lichfield became a busy coaching centre. Inns and hostelries grew up to provide accommodation, and industries dependent on the coaching trade such as coach builders, corn and hay merchants, saddlers and tanneries began to thrive. The |

In the 18th century, Lichfield became a busy coaching centre. Inns and hostelries grew up to provide accommodation, and industries dependent on the coaching trade such as coach builders, corn and hay merchants, saddlers, and tanneries began to thrive. The Corn Exchange was designed by T. Johnson and Son and completed in 1850.<ref>{{NHLE|desc=The Corn Exchange|num=1209913|access-date=9 June 2023}}</ref> |

||

By the end of the 19th century, [[brewing]] was the principal industry, and in the neighbourhood were large market gardens which provided food for the growing populations of nearby Birmingham and the [[Black Country]]. |

The invention of the railways saw a decline in coach travel, and with it came the decline in Lichfield's prosperity. By the end of the 19th century, [[brewing]] was the principal industry, and in the neighbourhood were large market gardens which provided food for the growing populations of nearby Birmingham and the [[Black Country]]. |

||

Today there are a number of light industrial areas, predominantly in the east of the city, not dominated by any one particular industry. The district is famous for two local |

Today there are a number of light industrial areas, predominantly in the east of the city, not dominated by any one particular industry. The district is famous for two local manufacturers: [[Armitage Shanks]], makers of baths/bidets and showers, and [[Arthur Price|Arthur Price of England]], master cutlers and silversmiths. Many residents commute to Birmingham. |

||

The city is home to [[Central England Co-operative]] (and its predecessor [[Midlands Co-operative Society]]), the second largest independent consumer co-operative in the UK. |

|||

Lichfield City Council has predicted that once completed, the new Friarsgate retail and leisure development could attract 11,000 more visitors to the city every month, generating annual sales of around £61 million and creating hundreds of jobs in the city.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://iclichfield.icnetwork.co.uk/news/localnews//tm_headline=credit-squeeze-delays-friarsgate&method=full&objectid=22250839&siteid=108911-name_page.html|title=Economic benefits of new development to Lichfield |publisher= icLichfield |accessdate=20 November 2008}}</ref> |

|||

==Culture and community== |

==Culture and community== |

||

[[File:Lichfield Garrick Theatre.jpg|thumb|[[Lichfield Garrick Theatre]] was built in 2003]] |

[[File:Lichfield Garrick Theatre.jpg|thumb|[[Lichfield Garrick Theatre]] was built in 2003]] |

||

[[File:The Guildhall, Lichfield - geograph.org.uk - 1515107.jpg|thumb|[[Lichfield Guildhall]], completed in 1848]] |

|||

===Culture=== |

===Culture=== |

||

The [[Lichfield Bower|Lichfield Greenhill Bower]] |

The [[Lichfield Bower|Lichfield Greenhill Bower]] takes place annually on [[Spring Bank Holiday]]. Originating from a celebration that was held after the [[Court of Arraye]] in the 12th century, the festival has evolved into its modern form, but has kept many of its ancient traditions.<ref name=bower>{{Citation| url = http://www.lichfieldbower.co.uk/the-bower-and-it-s-origins/| title = Lichfield Bower: The Bower & Its Origins| access-date = 28 January 2011| url-status = dead| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100625013319/http://www.lichfieldbower.co.uk/the-bower-and-it-s-origins/| archive-date = 25 June 2010| df = dmy-all}}</ref> After a recreation of the Court of Arraye at the [[Lichfield Guildhall|Guildhall]], a procession of marching bands, [[Morris dance|morris men]] and carnival floats makes its way through the city and the Bower Queen is crowned outside the Guildhall. There is a funfair in the city centre, and another fair and jamboree in [[Beacon Park]].<ref name=bower/> |

||

[[The Lichfield Festival]], an international arts festival, has taken place every July for 30 years. The festival is a celebration of classical music, dance, drama, film, jazz, literature, poetry, visual arts and world music. Events take place at many venues around the city but centre on [[Lichfield Cathedral]] and the [[Lichfield Garrick Theatre|Garrick Theatre]]. Popular events include the medieval market in the Cathedral Close and the fireworks display which closes the festival.<ref name=lichfest>{{Citation |

[[The Lichfield Festival]], an international arts festival, has taken place every July for 30 years. The festival is a celebration of classical music, dance, drama, film, jazz, literature, poetry, visual arts and world music. Events take place at many venues around the city but centre on [[Lichfield Cathedral]] and the [[Lichfield Garrick Theatre|Garrick Theatre]]. Popular events include the medieval market in the Cathedral Close and the fireworks display which closes the festival.<ref name=lichfest>{{Citation| url = http://www.lichfieldfestival.org/about-us/| title = Lichfield Festival: About Us| access-date = 28 January 2011| url-status = dead| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20101112144506/http://www.lichfieldfestival.org/about-us/| archive-date = 12 November 2010| df = dmy-all}}</ref> |

||

Triennially the Lichfield [[Mystery Play|Mysteries]], the biggest community theatre event in the country, takes place at the |

Triennially the Lichfield [[Mystery Play|Mysteries]], the biggest community theatre event in the country, takes place at the cathedral and in the Market Place. It consists of a [[play cycle|cycle]] of 24 medieval-style plays involving over 600 amateur actors.<ref name=lichmyst>{{Citation| url = http://www.lichfieldmysteries.co.uk/| title = Lichfield Mysteries: Home Page| access-date = 28 January 2011| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20101121100740/http://www.lichfieldmysteries.co.uk/| archive-date = 21 November 2010| url-status = live}}</ref> Other weekend summer festivals include the Lichfield [[Folk festival|Folk Festival]]<ref name=lichfolk>{{Citation| url = http://www.lichfieldfolkfestival.co.uk/minisite/minisite_home.aspx| title = Lichfield Folk Festival| access-date = 28 January 2011| url-status = dead| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20110723094630/http://www.lichfieldfolkfestival.co.uk/minisite/minisite_home.aspx| archive-date = 23 July 2011| df = dmy-all}}</ref> and The Lichfield [[Cask ale|Real Ale]], Jazz and Blues Festival.<ref name=lichale>{{Citation| url = http://www.lichfieldarts.org.uk/rajb.asp| title = Lichfield Arts: What's On| access-date = 28 January 2011| url-status = dead| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20110222024612/http://www.lichfieldarts.org.uk/rajb.asp| archive-date = 22 February 2011| df = dmy-all}}</ref> |

||

Lichfield Heritage Weekend, incorporating [[Samuel Johnson|Dr |

Lichfield Heritage Weekend, incorporating [[Samuel Johnson|Dr Johnson's]] Birthday Celebrations, takes place on the third weekend in September with a variety of civic events including live music and free historical tours of local landmarks. |

||

===Community facilities=== |

===Community facilities=== |

||

[[File:Beacon Park.jpg|thumb|[[Beacon Park]], in the city centre, hosts a wide range of community events.]] |

[[File:Beacon Park.jpg|thumb|[[Beacon Park]], in the city centre, hosts a wide range of community events.]] |

||

There are many parks, gardens and open spaces in the city. The city centre park is [[Beacon Park]] which hosts a range of community events and activities throughout the year. Also in the city centre are two lakes, [[Minster Pool]] and [[Stowe Pool]]. The Garden of Remembrance, a memorial garden laid out in 1920 after [[World War I]], is located on Bird Street. Many other parks are located on the outskirts of the city: these include Brownsfield Park, Darnford Park, Shortbutts Park, Stychbrook Park, Saddlers Wood and Christian Fields.<ref name=sssi>{{Citation |

There are many parks, gardens and open spaces in the city. The city centre park is [[Beacon Park]], which hosts a range of community events and activities throughout the year. Also in the city centre are two lakes, [[Minster Pool]] and [[Stowe Pool]]. The Garden of Remembrance, a memorial garden laid out in 1920 after [[World War I]], is located on Bird Street. Many other parks are located on the outskirts of the city: these include Brownsfield Park, Darnford Park, Shortbutts Park, Stychbrook Park, Saddlers Wood and Christian Fields.<ref name=sssi>{{Citation| url = http://www.lichfielddc.gov.uk/site/scripts/documents.php?categoryID=200145| title = Lichfield District Council: Lichfield's Parks| access-date = 28 January 2011| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20110928030847/http://www.lichfielddc.gov.uk/site/scripts/documents.php?categoryID=200145| archive-date = 28 September 2011| url-status = dead| df = dmy-all}}</ref> |

||

There are two public sports and leisure facilities in the city. Friary Grange Leisure Centre in the north-west of the city offers racket sports, a swimming pool, and sports hall and fitness gym. King Edward VI Leisure Centre in the south of the city offers racket sports, a sports hall and an [[artificial turf]] pitch. |

There are two public sports and leisure facilities in the city. Friary Grange Leisure Centre in the north-west of the city offers racket sports, a swimming pool, and sports hall and fitness gym. King Edward VI Leisure Centre in the south of the city offers racket sports, a sports hall and an [[artificial turf]] pitch. |

||

Lichfield Library and Record Office |

Lichfield Library and Record Office was located on the corner of St John Street and The Friary. The building also included an adult education centre and a small art gallery. The library occupied this building in 1989, when it moved from the Lichfield Free Library and Museum on Bird Street. The library moved into the newly renovated St Mary's church on Market Square in 2018 |

||

The city is served by the Samuel Johnson Community Hospital located on Trent Valley Road. This hospital replaced the now |

The city is served by the Samuel Johnson Community Hospital located on Trent Valley Road. This hospital replaced the now-demolished Victoria Hospital in 2006. |

||

==Media== |

|||

Local news and television programmes are provided by [[BBC West Midlands]] and [[ITV Central]]. Television signals are received from the [[Sutton Coldfield transmitting station|Sutton Coldfield]] transmitter.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://ukfree.tv/transmitters/tv/Sutton_Coldfield|title=Sutton Coldfield (Birmingham, England) Full Freeview transmitter|date=1 May 2004|website=UK Free TV|access-date=25 September 2023}}</ref> |

|||

The city's local radio stations are [[BBC Radio WM]], [[Capital Mid-Counties]], [[Heart West Midlands]], [[Greatest Hits Radio Birmingham & The West Midlands]], [[Smooth West Midlands]], [[Hits Radio Birmingham]] and [[Cannock Chase Radio FM]], a community radio station that broadcast from [[Cannock Chase]].<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.cannockchaseradio.co.uk/|title=Cannock Chase Radio |access-date=25 September 2023}}</ref> |

|||

Local newspapers are [[Lichfield Mercury]] and Lichfield Live.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://lichfieldlive.co.uk/|title=Lichfield Live |access-date=25 September 2023}}</ref> |

|||

== Places of interest == |

== Places of interest == |

||

[[File:Hospital of St Johns.jpg|thumb|The [[Hospital of St John Baptist without the Barrs]] built in 1495 as an [[almshouse]].]] |

[[File:Hospital of St Johns.jpg|thumb|The [[Hospital of St John Baptist without the Barrs]] built in 1495 as an [[almshouse]].]] |

||

[[File:The entrance to Cathedral Close, Lichfield, with Lichfield Cathedral in the background.jpg|thumb|The entrance to Cathedral Close at night, with Lichfield Cathedral in the background]] |

[[File:The entrance to Cathedral Close, Lichfield, with Lichfield Cathedral in the background.jpg|thumb|The entrance to Cathedral Close at night, with Lichfield Cathedral in the background]] |

||

[[File:Free Library and Museum, Bird Street, Lichfield (6681161483).jpg|thumb|The Free Library and Museum]] |

|||

*[[Lichfield Cathedral]] - The only medieval cathedral in Europe with three spires. The present building was started in 1195, and completed by the building of the Lady Chapel in the 1330s. It replaced a Norman building begun in 1085 which had replaced one, or possibly two, Saxon buildings from the seventh century. |

*[[Lichfield Cathedral]] - The only medieval cathedral in Europe with three spires. The present building was started in 1195, and completed by the building of the Lady Chapel in the 1330s. It replaced a Norman building begun in 1085 which had replaced one, or possibly two, Saxon buildings from the seventh century. |

||

*[[Cathedral Close, Lichfield|Cathedral Close]] - Surrounding the |

*[[Cathedral Close, Lichfield|Cathedral Close]] - Surrounding the cathedral, the close contains many buildings of architectural interest. |

||

*[[Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum]] - A museum to Samuel Johnson's life, work and personality. |

*[[Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum]] - A museum to Samuel Johnson's life, work and personality. |

||

*[[Erasmus Darwin House]] - Home to Erasmus Darwin, the house was restored to create a museum which opened to the public in 1999. |

*[[Erasmus Darwin House]] - Home to Erasmus Darwin, the house was restored to create a museum which opened to the public in 1999. |

||

* |

*The Hub at St Mary's - located in [[St Mary's Church, Lichfield|St Mary's Church]] in the market square, it is a community hub and event venue which also houses the local library. |

||

*[[ |

*[[Lichfield Guildhall]] - a historic building in the centre of Lichfield, located in Bore Street, it has been central to the government of the city for over 600 years. |

||

*[[Bishop's Palace, Lichfield|Bishop's Palace]] - Built in 1687, the palace was the residence of the Bishop of Lichfield until 1954; it is now used by the Cathedral School. |

*[[Bishop's Palace, Lichfield|Bishop's Palace]] - Built in 1687, the palace was the residence of the Bishop of Lichfield until 1954; it is now used by the Cathedral School. |

||

*[[Dr Milley's Hospital]] - Located on Beacon Street, it dates back to 1504 and was a women's hospital. |

*[[Dr Milley's Hospital]] - Located on Beacon Street, it dates back to 1504 and was a women's hospital. |

||

*[[Hospital of St John Baptist without the Barrs, Lichfield|Hospital of St John Baptist without the Barrs]] - A distinctive Tudor building with a row of eight brick chimneys. This was built outside the city walls (barrs) to provide accommodation for travellers arriving after the city gates were closed. It now provides homes for elderly people and has an adjacent Chapel. |

*[[Hospital of St John Baptist without the Barrs, Lichfield|Hospital of St John Baptist without the Barrs]] - A distinctive Tudor building with a row of eight brick chimneys. This was built outside the city walls (barrs) to provide accommodation for travellers arriving after the city gates were closed. It now provides homes for elderly people and has an adjacent Chapel. |

||

*[[The Church of St Chad, Lichfield|Church of St Chad]] - A 12th-century church, though extensively restored; |

*[[The Church of St Chad, Lichfield|Church of St Chad]] - A 12th-century church, though extensively restored; near the church is a reconstruction of 'St Chad's Well', where the 7th-century churchman St Chad, [[Ceadda|St Chad]] is said to have prayed and baptised people. |

||

*[[St Michael on Greenhill]] - Overlooking the city, the ancient churchyard is |

*[[St Michael on Greenhill]] - Overlooking the city, the ancient churchyard is one of the largest in the country at {{convert|9|acre|ha|0}}. |

||

*[[Christ Church, Lichfield|Christ Church]] - An outstanding example of Victorian ecclesiastical architecture and a [[grade II* listed building]]. |

*[[Christ Church, Lichfield|Christ Church]] - An outstanding example of Victorian ecclesiastical architecture and a [[grade II* listed building]]. |

||

*The Market Square - In the centre of the city, the square contains two statues, one of Samuel Johnson overlooking the house in which he was born, and one of his great friend and biographer, [[James Boswell]]. |

*The Market Square - In the centre of the city, the square contains two statues, one of Samuel Johnson overlooking the house in which he was born, and one of his great friend and biographer, [[James Boswell]]. |

||

*[[Beacon Park]] - An {{convert|81|acre|ha|0|adj=on}} public park in the centre of the city, used for many sporting and recreational activities. |

*[[Beacon Park]] - An {{convert|81|acre|ha|0|adj=on}} public park in the centre of the city, used for many sporting and recreational activities. |

||

*[[Minster Pool]] & [[Stowe Pool]] - The two lakes occupying 16 acres in the heart of Lichfield: Stowe Pool is designated a [[Site of Special Scientific Interest|SSSI]] site as it is home to native White-Clawed Crayfish. |

*[[Minster Pool]] & [[Stowe Pool]] - The two lakes occupying 16 acres in the heart of Lichfield: Stowe Pool is designated a [[Site of Special Scientific Interest|SSSI]] site as it is home to native White-Clawed Crayfish. By Stowe Pool stands Johnson's Willow, a descendant of the original enormous tree which was much admired and visited by Samuel Johnson. In 2021 the fifth incarnation of the tree was installed.<ref name="LDC2021">{{cite web |title=Johnson's Willow will live on |url=https://www.lichfielddc.gov.uk/news/article/469/johnson-s-willow-will-live-on |website=Lichfield District Council |access-date=10 February 2022}}</ref> |

||

*[[The Franciscan Friary,Lichfield|The Franciscan Friary]] - The ruins of the former Friary in Lichfield, now classed as a [[Scheduled monument|Scheduled Ancient Monument]]. |