Hiatal hernia: Difference between revisions

→Treatment: simplify - rm unnecessary |

Article referenced mentions "North America", not just the United States. Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| (246 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Entrance of abdominal organs into the middle chest through the diaphragm}} |

|||

{{lead too short|date=June 2013}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=April 2017}} |

|||

{{Infobox disease| |

|||

{{Infobox medical condition (new) |

|||

Name = Ventricular hernia | |

|||

| name = Hiatal hernia |

|||

| synonyms = Hiatus hernia |

|||

| image = Hiatalhernia.gif |

|||

DiseasesDB = 29116 | |

|||

| caption = A drawing of a hiatal hernia |

|||

ICD10 = {{ICD10|K|44||k|40}}, {{ICD10|Q|40|1|q|38}} | |

|||

| field = [[Gastroenterology]], [[general surgery]] |

|||

| symptoms = Taste of acid in the back of the mouth, [[heartburn]], trouble swallowing<ref name=BMJ2014/> |

|||

ICDO = | |

|||

| complications = [[Iron deficiency anemia]], [[volvulus]], [[bowel obstruction]]<ref name=BMJ2014/> |

|||

OMIM = 142400 | |

|||

| onset = |

|||

| duration = |

|||

eMedicineSubj = med | |

|||

| types = Sliding, paraesophageal<ref name=BMJ2014/> |

|||

eMedicineTopic = 1012 | |

|||

| causes = |

|||

eMedicine_mult = {{eMedicine2|radio|337}} | |

|||

| risks = [[Obesity]], older age, [[major trauma]]<ref name=BMJ2014/> |

|||

MeshID = D006551 | |

|||

| diagnosis = [[Endoscopy]], [[medical imaging]], [[Pressure measurement|manometry]]<ref name=BMJ2014/> |

|||

| differential = |

|||

| prevention = |

|||

| treatment = Raising the head of the bed, weight loss, medications, surgery<ref name=BMJ2014/> |

|||

| medication = [[H2 blockers]], [[proton pump inhibitor]]s<ref name=BMJ2014/> |

|||

| prognosis = |

|||

| frequency = 10–80% (US)<ref name=BMJ2014/> |

|||

| deaths = |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

A '''hiatus hernia''' or '''hiatal hernia''' is the protrusion (or [[herniation]]) of the upper part of the [[stomach]] into the [[chest|thorax]] through a tear or weakness in the [[diaphragm (anatomy)|diaphragm]]. |

|||

<!-- Definition and symptoms --> |

|||

== Classification == |

|||

A '''hiatal hernia''' or '''hiatus hernia'''<ref>{{Cite web |title=Hiatus hernia - Illnesses & conditions |author= |website=NHS inform |date= |access-date=10 May 2022 |url= https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/stomach-liver-and-gastrointestinal-tract/hiatus-hernia}}</ref> is a type of [[hernia]] in which [[abdominal]] [[Organ (anatomy)|organs]] (typically the [[stomach]]) slip through the [[Thoracic diaphragm|diaphragm]] into the [[mediastinum|middle compartment of the chest]].<ref name=BMJ2014/><ref name=Pub2017/> This may result in [[gastroesophageal reflux disease]] (GERD) or [[laryngopharyngeal reflux]] (LPR) with symptoms such as a taste of acid in the back of the mouth or [[heartburn]].<ref name=BMJ2014/><ref name=Pub2017>{{cite web|title=Hiatal Hernia|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMHT0028103/|website=PubMed Health|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170428062241/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMHT0028103/|archive-date=28 April 2017|df=dmy-all}}</ref> Other symptoms may include [[Dysphagia|trouble swallowing]] and [[chest pain]]s.<ref name=BMJ2014/> Complications may include [[iron deficiency anemia]], [[volvulus]], or [[bowel obstruction]].<ref name=BMJ2014/> |

|||

[[Image:Hiatus hernia.svg|thumb|Schematic diagram of different types of hiatus hernia. Green is the esophagus, red is the stomach, purple is the diaphragm, blue is the [[Angle_of_His|HIS-angle]]. A is the normal anatomy, B is a pre-stage, C is a sliding hiatal hernia, and D is a paraesophageal (rolling) type.]] |

|||

<!-- Causes and diagnosis --> |

|||

'''Three types of esophageal hiatal hernia are identified:'''<ref>F. Charles Brunicardi, Dane K. Andersen, Timothy R. Billiar..etl; Schwartz's Principles of Surgery; 9th edition; USA; The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2010; Chapter 25: Esophagus and Diaphragmatic Hernia; P 842-843; ISBN 978-0-07-1547703</ref> |

|||

The most common risk factors are [[obesity]] and [[ageing|older age]].<ref name=BMJ2014/> Other risk factors include [[major trauma]], [[scoliosis]], and certain types of surgery.<ref name=BMJ2014/> There are two main types: sliding hernia, in which the body of the stomach moves up; and paraesophageal hernia, in which an abdominal organ moves beside the [[esophagus]].<ref name=BMJ2014/> The diagnosis may be confirmed with [[endoscopy]] or [[medical imaging]].<ref name=BMJ2014/> Endoscopy is typically only required when concerning symptoms are present, symptoms are resistant to treatment, or the person is over 50 years of age.<ref name=BMJ2014/> |

|||

<!-- Treatment and epidemiology--> |

|||

'''type I (sliding) hernia:''' characterized by an upward herniation of the cardia and GE junction in the posterior mediastinum. The most common one. |

|||

Symptoms from a hiatal hernia may be improved by changes such as raising the head of the bed, weight loss, and adjusting eating habits.<ref name=BMJ2014/> Medications that reduce [[gastric acid]] such as [[H2 blockers]] or [[proton pump inhibitor]]s may also help with the symptoms.<ref name=BMJ2014/> If the condition does not improve with medications, a [[surgery]] to carry out a [[laparoscopic fundoplication]] may be an option.<ref name=BMJ2014/> Between 10% and 80% of adults in North America are affected.<ref name=BMJ2014>{{cite journal|last1=Roman|first1=S|last2=Kahrilas|first2=PJ|title=The diagnosis and management of hiatus hernia.|journal=BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.)|date=23 October 2014|volume=349|pages=g6154|pmid=25341679|doi=10.1136/bmj.g6154|s2cid=7141090|quote=However, the exact prevalence of hiatus hernia is difficult to determine because of the inherent subjectivity in diagnostic criteria. Consequently, estimates vary widely—for example, from 10% to 80% of the adult population in North America}}</ref> |

|||

==Signs and symptoms== |

|||

'''type II (rolling or paraesophageal) hernia (PEH):''' characterized by an upward herniation of the gastric fundus alongside a normally positioned cardia. GE jn is in normal place |

|||

[[File:Hiatal Hernia.png|thumb]] |

|||

[[File:Hernia de hiato.ogg|thumb|Hiatal hernia]] |

|||

Hiatal hernia has often been called the "great mimic" because its symptoms can resemble many disorders. Among them, a person with a hiatal hernia can experience dull pains in the chest, [[shortness of breath]] (caused by the hernia's effect on the [[Thoracic diaphragm|diaphragm]]), [[heart palpitations]] (due to irritation of the [[vagus nerve]]), and swallowed food "balling up" and causing discomfort in the lower esophagus until it passes on to the stomach. In addition, hiatal hernias often result in [[heartburn]] but may also cause chest pain or pain with eating.<ref name="BMJ2014"/> |

|||

In most cases, however, a hiatal hernia does not cause any symptoms. The pain and discomfort that a patient experiences is due to the reflux of gastric acid, air, or bile. While there are several causes of [[acid reflux]], it occurs more frequently in the presence of hiatal hernia. |

|||

'''type III (combined sliding-rolling or mixed) hernia:''' characterized by an upward herniation of both the cardia and the gastric fundus. |

|||

In newborns, the presence of [[Bochdalek hernia]] can be recognised<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Chang SW, Lee HC, Yeung CY, Chan WT, Hsu CH, Kao HA, Hung HY, Chang JH, Sheu JC, Wang NL |title=A twenty-year review of early and late-presenting congenital Bochdalek diaphragmatic hernia: are they different clinical spectra? |journal=Pediatr Neonatol |volume=51 |issue=1 |pages=26–30 |year=2010 |pmid=20225535 |doi=10.1016/S1875-9572(10)60006-X |doi-access=free }}</ref> from symptoms such as difficulty breathing,<ref>{{cite journal | pmid = 23810174 | doi=10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.04.076 | volume=96 | issue=4 | title=Diaphragmatic hernia after esophagectomy in 440 patients with long-term follow-up |vauthors=Ganeshan DM, Correa AM, Bhosale P, Vaporciyan AA, Rice D, Mehran RJ, Walsh GL, Iyer R, Roth JA, Swisher SG, Hofstetter WL| journal=Ann Thorac Surg | pages=1138–45| year=2013 | doi-access=free }}</ref> fast respiration, and increased heart rate.<ref>{{cite journal |first1=A |last1=Alam |first2=B.N. |last2=Chander |title=Adult bochdalek hernia |journal=MJAFI |volume=61 |issue=3 |pages=284–6 |date=July 2005 |doi=10.1016/S0377-1237(05)80177-7 |pmid=27407781 |pmc=4925637 }}</ref> |

|||

'''type IV hiatal hernia:''' is declared in some taxonomies, when an additional organ, usually the colon, herniates as well. |

|||

The end stage of type I and type II hernias occurs when the whole stomach migrates up into the chest by rotating 180° around its longitudinal axis, with the cardia and pylorus as fixed points. In this situation the abnormality is usually referred to as an intrathoracic stomach. |

|||

== Epidemiology == |

|||

Incidence of hiatal hernias increases with age; approximately 60% of individuals aged 50 or older have a hiatal hernia.<ref>Goyal Raj K, "Chapter 286. Diseases of the Esophagus". Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 17e.</ref> Of these, 9% are symptomatic, depending on the competence of the [[lower esophageal sphincter]] (LES). 95% of these are "sliding" hiatus hernias, in which the LES protrudes above the diaphragm along with the stomach, and only 5% are the "rolling" type (paraesophageal), in which the LES remains stationary but the stomach protrudes above the diaphragm. People of all ages can get this condition, but it is more common in older people. |

|||

According to Dr. [[Denis Burkitt]], "Hiatus hernia has its maximum prevalence in economically developed communities in North America and Western Europe ... In contrast the disease is rare in situations typified by rural African communities."<ref name="burkitt">{{cite journal |author=Burkitt DP |title=Hiatus hernia: is it preventable? |journal=Am. J. Clin. Nutr. |volume=34 |issue=3 |pages=428–31 |year=1981 |pmid=6259926 |doi= |url=http://www.ajcn.org/cgi/reprint/34/3/428.pdf }}</ref> Burkitt attributes the disease to insufficient dietary fiber and the use of the unnatural [[Defecation posture#Sitting defecation posture|sitting position for defecation]]. Both factors create the need for straining at stool, increasing intraabdominal pressure and pushing the stomach through the esophageal hiatus in the diaphragm.<ref name="PMC2579007">{{cite journal |author=Sontag S|title=Defining GERD |journal=Yale J Biol Med |volume=72 |issue=2-3 |pages=69–80|year=1999|pmc=2579007 |pmid=10780568}}</ref> |

|||

=== Risk factors === |

|||

The following are risk factors that can result in a hiatus hernia. |

|||

==Causes== |

|||

The following are potential causes of a hiatal hernia.<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hiatal-hernia/symptoms-causes/syc-20373379 |title = Hiatal hernia - Symptoms and causes|website = [[Mayo Clinic]]}}</ref> |

|||

* Increased pressure within the [[abdomen]] caused by: |

* Increased pressure within the [[abdomen]] caused by: |

||

** Heavy lifting or bending over |

** Heavy lifting or bending over |

||

| Line 46: | Line 49: | ||

** Hard sneezing |

** Hard sneezing |

||

** [[Vomiting|Violent vomiting]] |

** [[Vomiting|Violent vomiting]] |

||

** Straining during [[defecation]] (i.e., the [[Valsalva maneuver]]) |

|||

** Straining |

|||

** Stress |

|||

[[Obesity]] and age-related changes to the diaphragm are also general risk factors. |

|||

== Signs and symptoms == |

|||

== Diagnosis == |

|||

Hiatal hernia has often been called the "great mimic" because its symptoms can resemble many disorders. For example, a person with this problem can experience dull pains in the chest, [[shortness of breath]] (caused by the hernia's effect on the [[Thoracic diaphragm|diaphragm]]), [[heart palpitations]] (due to irritation of the [[vagus nerve]]), and swallowed food "balling up" and causing discomfort in lower esophagus until it passes on to stomach. |

|||

The diagnosis of a hiatal hernia is typically made through an [[upper GI series]], [[gastroscopy|endoscopy]], [[high resolution manometry]], [[esophageal pH monitoring]], and [[computed tomography]] (CT). Barium swallow as in upper GI series allows the size, location, stricture, stenosis of oesophagus to be seen. It can also evaluate the oesophageal movements. Endoscopy can analyse the esophageal internal surface for erosions, ulcers, and tumours. |

|||

Meanwhile, manometry can determine the integrity of esophageal movements, and the presence of [[esophageal achalasia]]. pH testings allows the quantitative analysis of acid reflux episodes. CT scan is useful in diagnosing complications of hiatal hernia such as gastric volvulus, perforation, [[pneumoperitoneum]], and pneumomediastinum.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Sfara |first1=Alice |last2=Dumitrașcu |first2=Dan L |date=2019-09-12 |title=The management of hiatal hernia: an update on diagnosis and treatment |url=https://medpharmareports.com/index.php/mpr/article/view/1323 |journal=Medicine and Pharmacy Reports |volume=92 |issue=4 |pages=321–325 |doi=10.15386/mpr-1323 |issn=2668-0572 |pmc=6853045 |pmid=31750430}}</ref> |

|||

In most cases however, a hiatal hernia does not cause any symptoms. The pain and discomfort that a patient experiences is due to the reflux of gastric acid, air, or bile. While there are several causes of [[acid reflux]], it does happen more frequently in the presence of hiatal hernia. |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" widths="360px" heights="220"> |

|||

== Diagnosis == |

|||

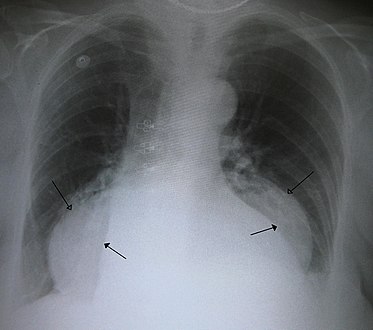

File:HiatusHernia10.JPG|A large hiatal hernia on [[chest radiography|chest X-ray]] marked by open arrows in contrast to the heart borders marked by closed arrows |

|||

File:Hiatus hernia with air-fluid level.jpg|This hiatal hernia is mainly identified by an air-fluid level (labeled with arrows). |

|||

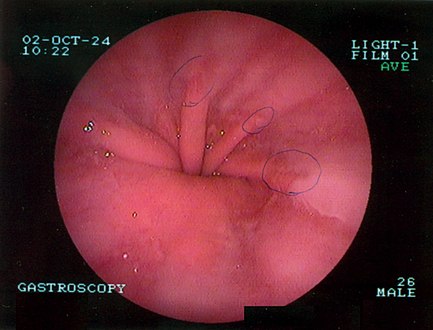

[[Image:Hiatus-hernia.jpg|thumb|right|[[gastroscopy|Upper GI endoscopy]] depicting hiatus hernia]] |

|||

File:Hiatus-hernia.jpg|[[gastroscopy|Upper GI endoscopy]] depicting hiatal hernia |

|||

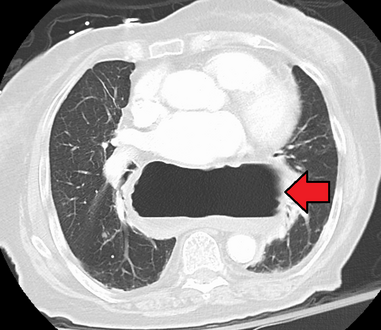

[[File:HiatusherniaCT.png|thumb|A hiatus hernia as seen on CT]] |

|||

File:Type_1_hiatus_hernia_on_retroflexion_with_fundic_gland_polyps.jpg|[[gastroscopy|Upper GI endoscopy]] in retroflexion showing Type I hiatal hernia |

|||

The diagnosis of a hiatus hernia is typically made through an [[upper GI series]], [[gastroscopy|endoscopy]] or [[high resolution manometry]]. |

|||

File:Hiatus hernia on CT scan.jpg|A hiatal hernia as seen on CT |

|||

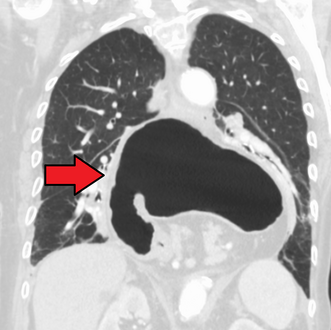

File:HiatusHerniaMark.png|A large hiatal hernia as seen on CT imaging |

|||

File:HiatusHerniaCorMark.png|A large hiatal hernia as seen on CT imaging |

|||

File:UOTW 39 - Ultrasound of the Week 1.webm|As seen on ultrasound<ref name=UOTW39>{{cite web|title=UOTW #39 - Ultrasound of the Week|url=https://www.ultrasoundoftheweek.com/uotw-39/|website=Ultrasound of the Week|access-date=27 May 2017|date=25 February 2015|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170509123328/https://www.ultrasoundoftheweek.com/uotw-39/|archive-date=9 May 2017|df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

|||

File:UOTW 39 - Ultrasound of the Week 2.webm|As seen on ultrasound<ref name=UOTW39/> |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

===Classification=== |

|||

== Treatment == |

|||

[[Image:Hiatus hernia.svg|thumb|Schematic diagram of different types of hiatus hernia. Green is the esophagus, red is the stomach, purple is the diaphragm, blue is the [[Angle of His|HIS-angle]]. A is the normal anatomy, B is a pre-stage, C is a sliding hiatal hernia, and D is a paraesophageal (rolling) type.]] |

|||

Four types of esophageal hiatal hernia are identified:<ref>{{Cite journal|title = Approaches to the diagnosis and grading of hiatal hernia|journal = Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology|pmc = 2548324|pmid = 18656819|pages = 601–616|volume = 22|issue = 4|doi = 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.12.007|first1 = Peter J.|last1 = Kahrilas|first2 = Hyon C.|last2 = Kim|first3 = John E.|last3 = Pandolfino|year = 2008}}</ref> |

|||

In most cases, sufferers experience no discomfort and no treatment is required. If there is pain or discomfort, 3 or 4 sips of room temperature water will usually relieve the pain. However, when the hiatal hernia is large, or is of the paraesophageal type, it is likely to cause [[esophageal stricture]] and discomfort. Symptomatic patients should elevate the head of their beds and avoid lying down directly after meals. If the condition has been brought on by stress, [[stress management|stress reduction techniques]] may be prescribed, or if overweight, [[weight loss]] may be indicated. Medications that reduce the [[lower esophageal sphincter]] (LES) pressure should be avoided. Antisecretory drugs like [[proton pump inhibitors]] and [[histamine H2 receptor|H<sub>2</sub> receptor]] blockers can be used to reduce acid secretion. |

|||

'''Type I:''' A type I hernia, also known as a sliding hiatal hernia, occurs when part of the stomach slides up through the hiatal opening in the diaphragm.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=Medical-surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinical problems |author=Lewis, Sharon Mantik |author2=Bucher, Linda |author3=Heitkemper, Margaret M. |author4=Harding, Mariann |author5=Kwong, Jeffery |author6=Roberts, Dottie |isbn=978-0-323-32852-4|edition=10th|location=St. Louis, Missouri |publisher=Elsevier |oclc=944472408|year = 2017}}</ref> There is a widening of the muscular hiatal tunnel and circumferential laxity of the [[phrenoesophageal ligament]], allowing a portion of the gastric cardia to herniate upward into the posterior mediastinum. The clinical significance of type I hernias is in their association with reflux disease. Sliding hernias are the most common type and account for 95% of all hiatal hernias.<ref name=Harrisons>{{cite book|author1=Dennis Kasper |author2=Anthony Fauci |author3=Stephen Hauser |author4=Dan Longo |author5=J. Larry Jameson |author6=Joseph Loscalzo |title=Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 19e|publisher=McGraw-Hill Global Education|isbn=978-0-07-180215-4|page=1902|edition=19|date=8 April 2015 }}</ref> '''(C)''' |

|||

Where hernia symptoms are severe and chronic acid reflux is involved, [[surgery]] is sometimes recommended, as chronic reflux can severely injure the [[esophagus]] and even lead to [[esophageal cancer]]. |

|||

'''Type II:''' A type II hernia, also known as a paraesophageal or rolling hernia, occurs when the fundus and greater curvature of the stomach roll up through the diaphragm, forming a pocket alongside the esophagus.<ref name=":0" /> It results from a localized defect in the phrenoesophageal ligament while the gastroesophageal junction remains fixed to the pre aortic fascia and the median arcuate ligament. The gastric fundus then serves as the leading point of herniation. Although type II hernias are associated with reflux disease, their primary clinical significance lies in the potential for mechanical complications. '''(D)''' |

|||

The surgical procedure used is called [[Nissen fundoplication]]. In fundoplication, the [[gastric fundus]] (upper part) of the stomach is wrapped, or plicated, around the inferior part of the esophagus, preventing herniation of the stomach through the hiatus in the diaphragm and the reflux of [[gastric acid]]. The procedure is now commonly performed [[Laparoscopic surgery|laparoscopically]]. With proper patient selection, laparoscopic [[fundoplication]] has low complication rates and a quick recovery.<ref name="Lange">Lange CMDT 2006</ref> |

|||

'''Type III:''' Type III hernias have elements of both types I and II hernias. With progressive enlargement of the hernia through the hiatus, the phrenoesophageal ligament stretches, displacing the gastroesophageal junction above the diaphragm, thereby adding a sliding element to the type II hernia. |

|||

Complications include [[gas bloat syndrome]], [[dysphagia]] (trouble swallowing), [[Gastric dumping syndrome|dumping syndrome]], excessive scarring, and rarely, [[achalasia]]. The procedure sometimes fails over time, requiring a second surgery to make repairs. |

|||

'''Type IV:''' Type IV hiatus hernia is associated with a large defect in the phrenoesophageal ligament, allowing other organs, such as colon, spleen, pancreas and small intestine to enter the hernia sac. |

|||

==References == |

|||

{{reflist|2}} |

|||

The end stage of type I and type II hernias occurs when the whole stomach migrates up into the chest by rotating 180° around its longitudinal axis, with the cardia and pylorus as fixed points. In this situation the abnormality is usually referred to as an intrathoracic stomach. |

|||

== External links == |

|||

==Treatment== |

|||

In the great majority of cases, people experience no significant discomfort, and no treatment is required. People with symptoms should elevate the head of their beds and avoid lying down directly after meals.<ref name=BMJ2014/> If the condition has been brought on by stress, [[stress management|stress reduction techniques]] may be prescribed, or if overweight, [[weight loss]] may be indicated. |

|||

===Medications=== |

|||

Antisecretory drugs such as [[proton pump inhibitors]] and [[histamine H2 receptor|H<sub>2</sub> receptor]] blockers can be used to reduce acid secretion. Medications that reduce the [[lower esophageal sphincter]] (LES) pressure should be avoided.{{citation needed|date=August 2020}} |

|||

===Procedures=== |

|||

There is tentative evidence from non-controlled trials that oral neuromuscular training may improve symptoms.<ref>{{Cite report |title=Clinical and technical evidence - IQoro for hiatus hernia |publisher=National Institute for Health and Care Excellence |date=6 March 2019 |url= https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/mib176/chapter/Clinical-and-technical-evidence |id=MIB176 }}</ref> This has been approved by the UK [[National Health Service]] for supply on prescription from 1 May 2022.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Innovative IQoro neuromuscular treatment device achieves NHS prescription status|author= |website=Advances in Clinical Neuroscience and Rehabilitation (ACNR)|date=25 March 2022|url= https://acnr.co.uk/iqoro/ }}</ref> |

|||

===Surgery=== |

|||

In some unusual instances, as when the hiatal hernia is unusually large, or is of the paraesophageal type, it may cause [[esophageal stricture]] or severe discomfort. About 5% of hiatal hernias are paraesophageal. If symptoms from such a hernia are severe for example if chronic acid reflux threatens to severely injure the [[esophagus]] or is causing [[Barrett's esophagus]], [[surgery]] is sometimes recommended. However surgery has its own risks including death and disability, so that even for large or paraesophageal hernias, watchful waiting may on balance be safer and cause fewer problems than surgery.<ref name=Sty2002>{{cite journal | pmc = 1422604 | pmid=12368678 | doi=10.1097/00000658-200210000-00012 | volume=236 | issue=4 | title=Paraesophageal hernias: operation or observation? |vauthors=Stylopoulos N, Gazelle GS, Rattner DW| journal=Ann Surg | pages=492–500 | year=2002 }}</ref> Complications from surgical procedures to correct a hiatal hernia may include [[gas bloat syndrome]], [[dysphagia]] (trouble swallowing), [[Gastric dumping syndrome|dumping syndrome]], excessive scarring, and rarely, [[achalasia]].<ref name=Sty2002/><ref>{{Cite report|url=https://www.ouh.nhs.uk/patient-guide/leaflets/files/68160Pnissen.pdf|title=Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication - Information for patients|publisher=Oxford University Hospitals NHS|date=December 2021|id=OMI68160}}</ref> Surgical procedures sometimes fail over time, requiring a second surgery to make repairs. |

|||

One surgical procedure used is called [[Nissen fundoplication]]. In fundoplication, the [[gastric fundus]] (upper part) of the stomach is wrapped, or plicated, around the inferior part of the esophagus, preventing herniation of the stomach through the hiatus in the diaphragm and the reflux of [[gastric acid]]. The procedure is now commonly performed [[Laparoscopic surgery|laparoscopically]]. With proper patient selection, laparoscopic [[fundoplication]] studies in the 21st century have indicated relatively low complication rates, quick recovery, and relatively good long term results.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Migaczewski M, Pędziwiatr M, Matłok M, Budzyński A |title=Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication in the treatment of Barrett's esophagus — 10 years of experience |journal=Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne |volume=8 |issue=2 |pages=139–45 |year=2013 |pmid=23837098 |pmc=3699774 |doi=10.5114/wiitm.2011.32941 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Witteman BP, Strijkers R, de Vries E, Toemen L, Conchillo JM, Hameeteman W, Dagnelie PC, Koek GH, Bouvy ND |title=Transoral incisionless fundoplication for treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease in clinical practice |journal=Surg Endosc |volume=26 |issue=11 |pages=3307–15 |year=2012 |pmid=22648098 |pmc=3472060 |doi=10.1007/s00464-012-2324-2 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Ozmen V, Oran ES, Gorgun E, Asoglu O, Igci A, Kecer M, Dizdaroglu F |title=Histologic and clinical outcome after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett's esophagus |journal=Surg Endosc |volume=20 |issue=2 |pages=226–9 |year=2006 |pmid=16362470 |doi=10.1007/s00464-005-0434-9 |s2cid=25195984 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Abbas AE, Deschamps C, Cassivi SD, Allen MS, Nichols FC, Miller DL, Pairolero PC |title=Barrett's esophagus: the role of laparoscopic fundoplication |journal=Ann. Thorac. Surg. |volume=77 |issue=2 |pages=393–6 |year=2004 |pmid=14759403 |doi=10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01352-3 |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

Regarding the discussion of partial versus complete fundoplication procedures, significant variations in the postoperative outcome emphasize the increased prevalence of dysphagia after Nissen. The statistics given support the superiority of laparoscopic over traditional surgery, owing to the greater aesthetic result, shorter admission time – with lower costs – and faster social reintegration.<ref>{{Cite journal|pmid = 22802887|year = 2012|last1 = Lucenco|first1 = L.|last2 = Marincas|first2 = M.|last3 = Cirimbei|first3 = C.|last4 = Bratucu|first4 = E.|last5 = Ionescu|first5 = S.|title = The 10 years' experience in the laparoscopic treatment of benign pathology of the eso gastric junction|journal = Journal of Medicine and Life|volume = 5|issue = 2|pages = 179–184|pmc = 3391883}}</ref> |

|||

==Epidemiology== |

|||

Incidence of hiatal hernias increases with age; approximately 60% of individuals aged 50 or older have a hiatal hernia.<ref>Goyal Raj K, "Chapter 286. Diseases of the Esophagus". Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 17e.</ref> Of these, 9% are symptomatic, depending on the competence of the [[lower esophageal sphincter]] (LES). 95% of these are "sliding" hiatal hernias, in which the LES protrudes above the diaphragm along with the stomach, and only 5% are the "rolling" type (paraesophageal), in which the LES remains stationary, but the stomach protrudes above the diaphragm.{{citation needed|date=August 2020}} <!-- Which condition does this text refer to, hernias generally or paraesophageal specifically? "People of all ages can get this condition, but it is more common in older people." --> |

|||

Hiatal hernias are most common in North America and Western Europe and rare in rural African communities.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Burkitt DP |title=Hiatus hernia: is it preventable? |journal=Am. J. Clin. Nutr. |volume=34 |issue=3 |pages=428–31 |year=1981 |pmid=6259926 |doi= 10.1093/ajcn/34.3.428|df=dmy-all |doi-access=free }}</ref> Some have proposed that insufficient dietary fiber and the use of a high [[Defecation posture#Sitting defecation posture|sitting position for defecation]] may increase the risk.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Sontag S|title=Defining GERD |journal=Yale J Biol Med |volume=72 |issue=2–3 |pages=69–80|year=1999|pmc=2579007 |pmid=10780568}}</ref> |

|||

==Veterinary== |

|||

Hiatal hernia has been described in [[wikt:small animal|small animal]]s since 1974, with the first case being in two dogs. It has since been reported in cats too. Type I is the most common and Type II is also common, but III and IV are rare with scarce reports in the literature.<ref name="vet">{{cite book |last1=Monnet | first1=Eric | first2=Ronald |last2=Bright| title=Small Animal Soft Tissue Surgery | publisher=John Wiley & Sons |location=Hoboken, NJ | date=2023-05-31 | isbn=978-1-119-69368-0 | pages=29–36 |chapter=Hiatal hernia}}</ref> |

|||

In dogs it is estimated 60% of cases are [[congenital]] with [[brachycephalic]] breeds being the most affected due to the [[oesophageal hiatus]]' cross-sectional area being larger than [[wikt:normocephalic|normocephalic]] and [[doliocephalic]] dogs. The diaphragm failing to fuse during development of the [[embryo]] is believed to be the cause of congenital hiatal hernia.<ref name="vet"/> |

|||

The [[Shar-pei]] and [[Bulldog]] are most commonly affected, however no mutation or heritability has been identified as of 2023. Other risk factors for the condition include: [[nasal mass]]es, [[laryngeal paralysis]], and a narrowed [[intrapharyngeal opening]].<ref name="vet"/> |

|||

[[Tetanus]] has been identified as a cause in dogs; these cases can be resolved via treating the tetanus.<ref name="vet"/> |

|||

Treatment of airway obstructions and feeding low-fat more digestible food can alleviate any need for invasive procedures.<ref name="vet"/> |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{Commons category|Hiatal hernia}} |

{{Commons category|Hiatal hernia}} |

||

{{Medical resources |

|||

* {{Chorus|01011}} |

|||

| DiseasesDB = 29116 |

|||

*[http://www.ctcases.net/ct-cases-database/4%20Abdomen%20And%20Pelvis/5%20Gastrointestinal%20Tract/4.5.13%20Hiatal%20hernia/ Hiatal hernia CT Scans] - CT Cases |

|||

| ICD10 = {{ICD10|K|44||k|40}}, {{ICD10|Q|40|1|q|38}} |

|||

*[http://www.teammead.co.uk/hiatushernia Hiatus Hernia - Help and Advice] - Hiatus Hernia - Help and Advice |

|||

| ICD9 = {{ICD9|553.3}}, {{ICD9|750.6}} |

|||

| ICDO = |

|||

| OMIM = 142400 |

|||

| MedlinePlus = 001137 |

|||

| eMedicineSubj = med |

|||

| eMedicineTopic = 1012 |

|||

| eMedicine_mult = {{eMedicine2|radio|337}} |

|||

| MeshID = D006551 |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Digestive system diseases}} |

{{Digestive system diseases}} |

||

{{Congenital malformations and deformations of digestive system}} |

{{Congenital malformations and deformations of digestive system}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hiatus Hernia}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hiatus Hernia}} |

||

[[Category:Diaphragmatic hernias]] |

|||

[[Category:Congenital disorders of digestive system]] |

[[Category:Congenital disorders of digestive system]] |

||

[[Category:Diaphragmatic hernias]] |

|||

[[Category:Wikipedia emergency medicine articles ready to translate]] |

|||

[[Category:Wikipedia medicine articles ready to translate]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 16:30, 8 September 2024

| Hiatal hernia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hiatus hernia |

| |

| A drawing of a hiatal hernia | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology, general surgery |

| Symptoms | Taste of acid in the back of the mouth, heartburn, trouble swallowing[1] |

| Complications | Iron deficiency anemia, volvulus, bowel obstruction[1] |

| Types | Sliding, paraesophageal[1] |

| Risk factors | Obesity, older age, major trauma[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Endoscopy, medical imaging, manometry[1] |

| Treatment | Raising the head of the bed, weight loss, medications, surgery[1] |

| Medication | H2 blockers, proton pump inhibitors[1] |

| Frequency | 10–80% (US)[1] |

A hiatal hernia or hiatus hernia[2] is a type of hernia in which abdominal organs (typically the stomach) slip through the diaphragm into the middle compartment of the chest.[1][3] This may result in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) with symptoms such as a taste of acid in the back of the mouth or heartburn.[1][3] Other symptoms may include trouble swallowing and chest pains.[1] Complications may include iron deficiency anemia, volvulus, or bowel obstruction.[1]

The most common risk factors are obesity and older age.[1] Other risk factors include major trauma, scoliosis, and certain types of surgery.[1] There are two main types: sliding hernia, in which the body of the stomach moves up; and paraesophageal hernia, in which an abdominal organ moves beside the esophagus.[1] The diagnosis may be confirmed with endoscopy or medical imaging.[1] Endoscopy is typically only required when concerning symptoms are present, symptoms are resistant to treatment, or the person is over 50 years of age.[1]

Symptoms from a hiatal hernia may be improved by changes such as raising the head of the bed, weight loss, and adjusting eating habits.[1] Medications that reduce gastric acid such as H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors may also help with the symptoms.[1] If the condition does not improve with medications, a surgery to carry out a laparoscopic fundoplication may be an option.[1] Between 10% and 80% of adults in North America are affected.[1]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

Hiatal hernia has often been called the "great mimic" because its symptoms can resemble many disorders. Among them, a person with a hiatal hernia can experience dull pains in the chest, shortness of breath (caused by the hernia's effect on the diaphragm), heart palpitations (due to irritation of the vagus nerve), and swallowed food "balling up" and causing discomfort in the lower esophagus until it passes on to the stomach. In addition, hiatal hernias often result in heartburn but may also cause chest pain or pain with eating.[1]

In most cases, however, a hiatal hernia does not cause any symptoms. The pain and discomfort that a patient experiences is due to the reflux of gastric acid, air, or bile. While there are several causes of acid reflux, it occurs more frequently in the presence of hiatal hernia.

In newborns, the presence of Bochdalek hernia can be recognised[4] from symptoms such as difficulty breathing,[5] fast respiration, and increased heart rate.[6]

Causes

[edit]The following are potential causes of a hiatal hernia.[7]

- Increased pressure within the abdomen caused by:

- Heavy lifting or bending over

- Frequent or hard coughing

- Hard sneezing

- Violent vomiting

- Straining during defecation (i.e., the Valsalva maneuver)

Obesity and age-related changes to the diaphragm are also general risk factors.

Diagnosis

[edit]The diagnosis of a hiatal hernia is typically made through an upper GI series, endoscopy, high resolution manometry, esophageal pH monitoring, and computed tomography (CT). Barium swallow as in upper GI series allows the size, location, stricture, stenosis of oesophagus to be seen. It can also evaluate the oesophageal movements. Endoscopy can analyse the esophageal internal surface for erosions, ulcers, and tumours.

Meanwhile, manometry can determine the integrity of esophageal movements, and the presence of esophageal achalasia. pH testings allows the quantitative analysis of acid reflux episodes. CT scan is useful in diagnosing complications of hiatal hernia such as gastric volvulus, perforation, pneumoperitoneum, and pneumomediastinum.[8]

-

A large hiatal hernia on chest X-ray marked by open arrows in contrast to the heart borders marked by closed arrows

-

This hiatal hernia is mainly identified by an air-fluid level (labeled with arrows).

-

Upper GI endoscopy depicting hiatal hernia

-

Upper GI endoscopy in retroflexion showing Type I hiatal hernia

-

A hiatal hernia as seen on CT

-

A large hiatal hernia as seen on CT imaging

-

A large hiatal hernia as seen on CT imaging

-

As seen on ultrasound[9]

-

As seen on ultrasound[9]

Classification

[edit]

Four types of esophageal hiatal hernia are identified:[10]

Type I: A type I hernia, also known as a sliding hiatal hernia, occurs when part of the stomach slides up through the hiatal opening in the diaphragm.[11] There is a widening of the muscular hiatal tunnel and circumferential laxity of the phrenoesophageal ligament, allowing a portion of the gastric cardia to herniate upward into the posterior mediastinum. The clinical significance of type I hernias is in their association with reflux disease. Sliding hernias are the most common type and account for 95% of all hiatal hernias.[12] (C)

Type II: A type II hernia, also known as a paraesophageal or rolling hernia, occurs when the fundus and greater curvature of the stomach roll up through the diaphragm, forming a pocket alongside the esophagus.[11] It results from a localized defect in the phrenoesophageal ligament while the gastroesophageal junction remains fixed to the pre aortic fascia and the median arcuate ligament. The gastric fundus then serves as the leading point of herniation. Although type II hernias are associated with reflux disease, their primary clinical significance lies in the potential for mechanical complications. (D)

Type III: Type III hernias have elements of both types I and II hernias. With progressive enlargement of the hernia through the hiatus, the phrenoesophageal ligament stretches, displacing the gastroesophageal junction above the diaphragm, thereby adding a sliding element to the type II hernia.

Type IV: Type IV hiatus hernia is associated with a large defect in the phrenoesophageal ligament, allowing other organs, such as colon, spleen, pancreas and small intestine to enter the hernia sac.

The end stage of type I and type II hernias occurs when the whole stomach migrates up into the chest by rotating 180° around its longitudinal axis, with the cardia and pylorus as fixed points. In this situation the abnormality is usually referred to as an intrathoracic stomach.

Treatment

[edit]In the great majority of cases, people experience no significant discomfort, and no treatment is required. People with symptoms should elevate the head of their beds and avoid lying down directly after meals.[1] If the condition has been brought on by stress, stress reduction techniques may be prescribed, or if overweight, weight loss may be indicated.

Medications

[edit]Antisecretory drugs such as proton pump inhibitors and H2 receptor blockers can be used to reduce acid secretion. Medications that reduce the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure should be avoided.[citation needed]

Procedures

[edit]There is tentative evidence from non-controlled trials that oral neuromuscular training may improve symptoms.[13] This has been approved by the UK National Health Service for supply on prescription from 1 May 2022.[14]

Surgery

[edit]In some unusual instances, as when the hiatal hernia is unusually large, or is of the paraesophageal type, it may cause esophageal stricture or severe discomfort. About 5% of hiatal hernias are paraesophageal. If symptoms from such a hernia are severe for example if chronic acid reflux threatens to severely injure the esophagus or is causing Barrett's esophagus, surgery is sometimes recommended. However surgery has its own risks including death and disability, so that even for large or paraesophageal hernias, watchful waiting may on balance be safer and cause fewer problems than surgery.[15] Complications from surgical procedures to correct a hiatal hernia may include gas bloat syndrome, dysphagia (trouble swallowing), dumping syndrome, excessive scarring, and rarely, achalasia.[15][16] Surgical procedures sometimes fail over time, requiring a second surgery to make repairs.

One surgical procedure used is called Nissen fundoplication. In fundoplication, the gastric fundus (upper part) of the stomach is wrapped, or plicated, around the inferior part of the esophagus, preventing herniation of the stomach through the hiatus in the diaphragm and the reflux of gastric acid. The procedure is now commonly performed laparoscopically. With proper patient selection, laparoscopic fundoplication studies in the 21st century have indicated relatively low complication rates, quick recovery, and relatively good long term results.[17][18][19][20] Regarding the discussion of partial versus complete fundoplication procedures, significant variations in the postoperative outcome emphasize the increased prevalence of dysphagia after Nissen. The statistics given support the superiority of laparoscopic over traditional surgery, owing to the greater aesthetic result, shorter admission time – with lower costs – and faster social reintegration.[21]

Epidemiology

[edit]Incidence of hiatal hernias increases with age; approximately 60% of individuals aged 50 or older have a hiatal hernia.[22] Of these, 9% are symptomatic, depending on the competence of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). 95% of these are "sliding" hiatal hernias, in which the LES protrudes above the diaphragm along with the stomach, and only 5% are the "rolling" type (paraesophageal), in which the LES remains stationary, but the stomach protrudes above the diaphragm.[citation needed]

Hiatal hernias are most common in North America and Western Europe and rare in rural African communities.[23] Some have proposed that insufficient dietary fiber and the use of a high sitting position for defecation may increase the risk.[24]

Veterinary

[edit]Hiatal hernia has been described in small animals since 1974, with the first case being in two dogs. It has since been reported in cats too. Type I is the most common and Type II is also common, but III and IV are rare with scarce reports in the literature.[25]

In dogs it is estimated 60% of cases are congenital with brachycephalic breeds being the most affected due to the oesophageal hiatus' cross-sectional area being larger than normocephalic and doliocephalic dogs. The diaphragm failing to fuse during development of the embryo is believed to be the cause of congenital hiatal hernia.[25]

The Shar-pei and Bulldog are most commonly affected, however no mutation or heritability has been identified as of 2023. Other risk factors for the condition include: nasal masses, laryngeal paralysis, and a narrowed intrapharyngeal opening.[25]

Tetanus has been identified as a cause in dogs; these cases can be resolved via treating the tetanus.[25]

Treatment of airway obstructions and feeding low-fat more digestible food can alleviate any need for invasive procedures.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Roman, S; Kahrilas, PJ (23 October 2014). "The diagnosis and management of hiatus hernia". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 349: g6154. doi:10.1136/bmj.g6154. PMID 25341679. S2CID 7141090.

However, the exact prevalence of hiatus hernia is difficult to determine because of the inherent subjectivity in diagnostic criteria. Consequently, estimates vary widely—for example, from 10% to 80% of the adult population in North America

- ^ "Hiatus hernia - Illnesses & conditions". NHS inform. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Hiatal Hernia". PubMed Health. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017.

- ^ Chang SW, Lee HC, Yeung CY, Chan WT, Hsu CH, Kao HA, Hung HY, Chang JH, Sheu JC, Wang NL (2010). "A twenty-year review of early and late-presenting congenital Bochdalek diaphragmatic hernia: are they different clinical spectra?". Pediatr Neonatol. 51 (1): 26–30. doi:10.1016/S1875-9572(10)60006-X. PMID 20225535.

- ^ Ganeshan DM, Correa AM, Bhosale P, Vaporciyan AA, Rice D, Mehran RJ, Walsh GL, Iyer R, Roth JA, Swisher SG, Hofstetter WL (2013). "Diaphragmatic hernia after esophagectomy in 440 patients with long-term follow-up". Ann Thorac Surg. 96 (4): 1138–45. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.04.076. PMID 23810174.

- ^ Alam, A; Chander, B.N. (July 2005). "Adult bochdalek hernia". MJAFI. 61 (3): 284–6. doi:10.1016/S0377-1237(05)80177-7. PMC 4925637. PMID 27407781.

- ^ "Hiatal hernia - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic.

- ^ Sfara, Alice; Dumitrașcu, Dan L (12 September 2019). "The management of hiatal hernia: an update on diagnosis and treatment". Medicine and Pharmacy Reports. 92 (4): 321–325. doi:10.15386/mpr-1323. ISSN 2668-0572. PMC 6853045. PMID 31750430.

- ^ a b "UOTW #39 - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. 25 February 2015. Archived from the original on 9 May 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Kahrilas, Peter J.; Kim, Hyon C.; Pandolfino, John E. (2008). "Approaches to the diagnosis and grading of hiatal hernia". Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology. 22 (4): 601–616. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2007.12.007. PMC 2548324. PMID 18656819.

- ^ a b Lewis, Sharon Mantik; Bucher, Linda; Heitkemper, Margaret M.; Harding, Mariann; Kwong, Jeffery; Roberts, Dottie (2017). Medical-surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinical problems (10th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-32852-4. OCLC 944472408.

- ^ Dennis Kasper; Anthony Fauci; Stephen Hauser; Dan Longo; J. Larry Jameson; Joseph Loscalzo (8 April 2015). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 19e (19 ed.). McGraw-Hill Global Education. p. 1902. ISBN 978-0-07-180215-4.

- ^ Clinical and technical evidence - IQoro for hiatus hernia (Report). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 6 March 2019. MIB176.

- ^ "Innovative IQoro neuromuscular treatment device achieves NHS prescription status". Advances in Clinical Neuroscience and Rehabilitation (ACNR). 25 March 2022.

- ^ a b Stylopoulos N, Gazelle GS, Rattner DW (2002). "Paraesophageal hernias: operation or observation?". Ann Surg. 236 (4): 492–500. doi:10.1097/00000658-200210000-00012. PMC 1422604. PMID 12368678.

- ^ Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication - Information for patients (PDF) (Report). Oxford University Hospitals NHS. December 2021. OMI68160.

- ^ Migaczewski M, Pędziwiatr M, Matłok M, Budzyński A (2013). "Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication in the treatment of Barrett's esophagus — 10 years of experience". Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 8 (2): 139–45. doi:10.5114/wiitm.2011.32941. PMC 3699774. PMID 23837098.

- ^ Witteman BP, Strijkers R, de Vries E, Toemen L, Conchillo JM, Hameeteman W, Dagnelie PC, Koek GH, Bouvy ND (2012). "Transoral incisionless fundoplication for treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease in clinical practice". Surg Endosc. 26 (11): 3307–15. doi:10.1007/s00464-012-2324-2. PMC 3472060. PMID 22648098.

- ^ Ozmen V, Oran ES, Gorgun E, Asoglu O, Igci A, Kecer M, Dizdaroglu F (2006). "Histologic and clinical outcome after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett's esophagus". Surg Endosc. 20 (2): 226–9. doi:10.1007/s00464-005-0434-9. PMID 16362470. S2CID 25195984.

- ^ Abbas AE, Deschamps C, Cassivi SD, Allen MS, Nichols FC, Miller DL, Pairolero PC (2004). "Barrett's esophagus: the role of laparoscopic fundoplication". Ann. Thorac. Surg. 77 (2): 393–6. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01352-3. PMID 14759403.

- ^ Lucenco, L.; Marincas, M.; Cirimbei, C.; Bratucu, E.; Ionescu, S. (2012). "The 10 years' experience in the laparoscopic treatment of benign pathology of the eso gastric junction". Journal of Medicine and Life. 5 (2): 179–184. PMC 3391883. PMID 22802887.

- ^ Goyal Raj K, "Chapter 286. Diseases of the Esophagus". Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 17e.

- ^ Burkitt DP (1981). "Hiatus hernia: is it preventable?". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 34 (3): 428–31. doi:10.1093/ajcn/34.3.428. PMID 6259926.

- ^ Sontag S (1999). "Defining GERD". Yale J Biol Med. 72 (2–3): 69–80. PMC 2579007. PMID 10780568.

- ^ a b c d e Monnet, Eric; Bright, Ronald (31 May 2023). "Hiatal hernia". Small Animal Soft Tissue Surgery. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 29–36. ISBN 978-1-119-69368-0.