William Lyon Mackenzie: Difference between revisions

Added an organization he was a part of |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Scottish-born Canadian-American journalist and politician (1795–1861)}} |

|||

{{about||the Toronto high school|William Lyon Mackenzie Collegiate Institute|the Canadian Prime Minister (Mackenzie's grandson)|William Lyon Mackenzie King|the fireboat|William Lyon Mackenzie (fireboat)}} |

|||

{{about||the fireboat|William Lyon Mackenzie (fireboat)|the high school|William Lyon Mackenzie Collegiate Institute|the prime minister (Mackenzie's grandson)|William Lyon Mackenzie King}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=March 2012}} |

|||

{{featured article}} |

|||

{{Infobox Mayor |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=December 2023}} |

|||

| name =William Lyon Mackenzie |

|||

{{Use Canadian English|date=February 2021}} |

|||

| image = WilliamLyonMackenzie.jpeg|300px |

|||

{{Infobox officeholder |

|||

| caption = |

|||

| image = WilliamLyonMackenzie.jpeg |

|||

| birth_date = 12 March 1795 |

|||

| caption = Mackenzie {{Circa|1851–61}} |

|||

| birth_place = [[Dundee]], [[Scotland]], [[United Kingdom|UK]] |

|||

| alt = A portrait of Mackenzie depicted sitting in a chair with papers in his hands. |

|||

| death_date = {{death date and age|df=y|1861|8|28|1795|3|12}} |

|||

| birth_date = March 12, 1795 |

|||

| death_place = [[Toronto]], [[Upper Canada]] |

|||

| birth_place = [[Dundee]], Scotland |

|||

| office1 = [[Mayor of Toronto|1st Mayor of Toronto]] |

|||

| death_date = {{Death date and age|1861|8|28|1795|3|12}} |

|||

| term_start1 = 27 March 1834 |

|||

| death_place = [[Toronto]], [[Canada West]]<br />(now [[Ontario]], Canada) |

|||

| term_end1 = 1834 |

|||

| restingplace = [[Toronto Necropolis]] |

|||

| predecessor1 = N/A <br><small>(Newly created office, replacing the chairman of the [[Home District Council]] for the town of York.) |

|||

| office = 1st [[Mayor of Toronto]] |

|||

| successor1 = [[Robert Baldwin Sullivan|Robert Sullivan]] |

|||

| term_start = 1834 |

|||

| office2 = [[Republic of Canada|1st President of the Republic of Canada]] |

|||

| term_end = 1835 |

|||

| term_start2 = 13 December 1837 |

|||

| office2 = Member of the<br />[[Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada|Upper Canada Legislative Assembly]]<br />for [[York County, Ontario|York]] |

|||

| term_end2 = 14 January 1838 |

|||

| term_start2 = 1829 |

|||

| predecessor2 = |

|||

| |

| term_end2 = 1834 |

||

| successor2 = [[Edward William Thomson]] |

|||

| party = [[The Reform Movement (Upper Canada)]] |

|||

| office3 = Member of the<br />[[Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada|Province of Canada Legislative Assembly]]<br /> for [[Haldimand County]] |

|||

| religion = |

|||

| |

| term_start3 = 1851 |

||

| |

| term_end3 = 1858 |

||

| predecessor3 = [[David Thompson (Canada West politician)|David Thompson]] |

|||

| majority = |

|||

| alma_mater = |

|||

| spouse = Isabel Baxter |

|||

| |

| constituency = |

||

| party = [[Reform movement (pre-Confederation Canada)|Reform]] |

|||

| occupation = Journalist, Politician |

|||

| otherparty = |

|||

| signature = William Lyon MacKenzie Signature.svg |

|||

| majority = |

|||

| spouse = {{marriage|Isabel Baxter|July 1, 1822}} |

|||

| children = 14 |

|||

| occupation = Journalist, politician |

|||

| signature = William Lyon MacKenzie Signature.svg |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''William Lyon Mackenzie |

'''William Lyon Mackenzie'''{{Efn|The last name is also spelled McKenzie, MacKenzie or M'Kenzie.{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=273}}}} (March{{nbsp}}12, 1795{{snd}} August{{nbsp}}28, 1861) was a Scottish Canadian-American journalist and politician. He founded newspapers critical of the [[Family Compact]], a term used to identify elite members of [[Upper Canada]]. He represented [[York County, Ontario|York County]] in the [[Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada]] and aligned with [[Reform movement (Upper Canada)|Reformers]]. He led the rebels in the [[Upper Canada Rebellion]]; after its defeat, he unsuccessfully rallied American support for an invasion of Upper Canada as part of the [[Patriot War]]. Although popular for criticising government officials, he failed to implement most of his policy objectives. He is one of the most recognizable Reformers of the early 19th century. |

||

Raised in [[Dundee]], Scotland, Mackenzie emigrated to [[York, Upper Canada]], in 1820. He published his first newspaper, the ''[[Colonial Advocate]]'' in 1824, and was elected a York County representative to the Legislative Assembly in 1827. York became the city of Toronto in 1834 and Mackenzie was elected its [[List of mayors of Toronto|first mayor]]; he declined the Reformers' nomination to run in the 1835 municipal election. He lost his re-election for the Legislative Assembly in 1836; this convinced him that reforms to the Upper Canadian political system could only happen if citizens initiated an armed conflict. In 1837, he rallied farmers in the area surrounding Toronto and convinced Reform leaders to support the Upper Canada Rebellion. Rebel leaders chose Mackenzie to be their military commander, but were defeated by government troops at the [[Battle of Montgomery's Tavern]]. |

|||

== Early life & emigration == |

|||

Mackenzie fled to the United States and rallied US support to invade Upper Canada and overthrow the province's government. This violated the [[Neutrality Act of 1794|Neutrality Act]], which prohibits invading a foreign country (with which the United States is not at war) from American territory. Mackenzie was arrested and sentenced to eighteen months' imprisonment. He was jailed for more than ten months before he was pardoned by the American president [[Martin Van Buren]]. After his release, Mackenzie lived in several cities in New York State and tried to publish newspapers, but these ventures failed. He discovered documents that outlined corrupt financial transactions and government appointments by New York State government officials. He published these documents in two books. The parliament of the newly created [[Province of Canada]], formed from the merger of Upper and [[Lower Canada]], granted Mackenzie amnesty in 1849 and he returned to Canada. He represented the constituency of [[Haldimand County]] in the province's legislature from 1851 to 1858. His health deteriorated in 1861 and he died on August{{nbsp}}28. |

|||

===Background and early years in Scotland, 1795–1820=== |

|||

{{TOC limit|2}} |

|||

William Lyon Mackenzie was born on 12 March 1795 in [[Scotland]] in the [[Dundee]] suburb Springfield.{{sfn|Gates|1996|p=12}} His mother Elizabeth ({{nee}} Chambers) of [[Kirkmichael]] was a widow seventeen years older than his father, weaver Daniel Mckenzie;{{citation needed|date=May 2013}} the couple married 8 May 1794. Daniel died 27 days after William's birth,{{efn|Historians have been unable to find a record of Daniel Mackenzie's burial.{{citation needed|date=May 2013}} }}{{sfn|Lindsey|1910|p=34}} and his 45-year-old mother raised him alone;{{sfn|Gates|1996|p=12}} with the support of relatives, as Daniel had left her no significant property. Elizabeth Mackenzie was a deeply religious woman, a proponent of the [[United Secession Church|Secession]], a branch of Scottish [[Presbyterianism]] deeply committed to the [[separation of church and state]].{{sfn|Lindsey|1910|p=34}} While Mackenzie was not a religious man himself, he remained a proponent of separation of church and state for his entire life. |

|||

== Early life and immigration (1795–1824) == |

|||

Mackenzie entered a parish grammar school at Dundee at age 5, thanks to a bursary, and then moved on to a Mr. Adie's school. He was a voracious reader, keeping a list of the 958 books he read between 1806 and 1820. By 1810, aged 15, he was writing for a local newspaper. During this time he also joined an early "[[Mechanics Institute]]". It was there that he met Edward Lesslie and his sons [[James Lesslie (publisher)|James]] and John, who played a large role in his life. They would all be key to establishing a Mechanics Institute in Toronto.{{sfn|Schrauwers|2009|p=135}} |

|||

===Background, early years in Scotland, and education=== |

|||

William Lyon Mackenzie was born on March 12, 1795, in [[Dundee]], Scotland.{{Efn|Some sources state that Mackenzie was born in Springfield, described as a suburb{{Sfn|Gates|1996|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA12 12]}} or a section of Dundee.{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/496/mode/2up 496]}}{{Sfn|Lindsey|1862|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=we1YAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA14 14]}} Other sources state he was born in Dundee{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=14}} or in an unstated location near Dundee.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/10/ 11]}}}} Both of his grandfathers were part of [[Clan Mackenzie]] and fought for [[Charles Edward Stuart]] at the [[Battle of Culloden]].{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/10/ 11]}}{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=17}} His mother, Elizabeth Chambers (née Mackenzie), a weaver and [[goatherd|goat herder]], was orphaned at a young age.{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/496/mode/2up 496]}}{{Sfn|Gray|1998|p=[https://archive.org/details/mrskinglifetimes0000gray/page/12/mode/2up 13]}}{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=32}} His father, Daniel Mackenzie, was also a weaver and seventeen years younger than Elizabeth.{{Sfn|Gray|1998|p=[https://archive.org/details/mrskinglifetimes0000gray/page/14/mode/2up 14]}} The couple married on May 8, 1794.{{Sfn|Lindsey|1862|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=we1YAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA14 14]}} After attending a public dance, Daniel became sick, blind and bedridden. He died a few weeks after William was born.{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=32}}{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=13}} |

|||

Although Elizabeth had relatives in Dundee, she insisted on raising William independently{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=32}} and instructed him on the teachings of the [[Presbyterianism|Presbyterian church]].{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|pp=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/13/ 13–14]}} Mackenzie reported he was raised in poverty, although the extent of his family's wealth is difficult to authenticate.{{Sfn|Raible|1992|pp=32–33}} At five years old, Mackenzie received a [[bursary]] for a parish grammar school in Dundee.{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/496/mode/2up 496]}} When he was eleven, he used the reading room of the [[The Courier (Dundee)|''Dundee Advertiser'']] newspaper and meticulously documented and summarized the 957 books he read.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|pp=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/15/ 15–16]}}{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|pp=18–19}} In 1811, he was a founding member of the Dundee Rational Institution, a club for scientific discussion.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=19}} |

|||

Mackenzie's mother arranged for him to apprentice with tradesmen in [[Dundee]], but in 1814, he secured financial backing from Edward Lesslie to open a general store and [[circulating library]] in [[Alyth]]. During this period Mackenzie had a relationship with Isabel Reid, of whom nothing is known except that she gave birth to Mackenzie's illegitimate son on July 17, 1814. The boy was raised by Mackenzie's mother. |

|||

In 1813, William moved to [[Alyth]], Scotland, to help his mother open a general store.{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=33}} He had a sexual relationship with Isabel Reid, and she gave birth to their son James on July 17, 1814.{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/496/mode/2up 497]}} His congregation agreed to baptize James after Mackenzie endured public criticism for fathering an illegitimate child and paid a fine of [[£sd|thirteen shillings and fourpence]] ({{Inflation|UK|{{£sd|s=13|d=4}}|1814|fmt=eq|cursign=£}}) to the church.{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=34}} A recession followed the end of the [[Napoleonic Wars]] in 1815, and Mackenzie's store went bankrupt.{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=13}} He moved to southern England and worked as a bookkeeper for the [[Kennet and Avon Canal|Kennet and Avon Canal Company]].{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=27}} He spent most of his money on wild behaviour and became a gambler.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/17/ 17]}} |

|||

During the recession which followed the 1815 end of the [[Napoleonic Wars]], Mackenzie's store in Dundee went bankrupt and he travelled to seek work in Dundee, then [[Wiltshire]] in 1818 to work for a canal company. He travelled briefly to France and then worked briefly for a newspaper in London. Lacking stable employment, at age 25, Mackenzie [[emigration|emigrated]] to [[British North America]] with John Lesslie. |

|||

===Early years in Canada |

===Early years in Canada=== |

||

[[Image:MrsMackenzie.jpg|thumb|alt= |

[[Image:MrsMackenzie.jpg|thumb|upright|alt=A portrait of Isabel, Mackenzie's wife. Isabel is seated in a chair facing part-way leftward.|A portrait of Isabel Mackenzie (née Baxter), Mackenzie's wife, painted in 1850]] |

||

Mackenzie's friend John Lesslie suggested they emigrate to Canada in 1820, and the two men travelled there aboard a [[schooner]] named ''Psyche''.{{Sfn|Gray|1998|p=[https://archive.org/details/mrskinglifetimes0000gray/page/14/mode/2up 15]}} When Mackenzie arrived in North America, he worked in [[Montreal]] for the owners of the [[Lachine Canal]] as a bookkeeper and ''[[Montreal Herald|The Montreal Herald]]'' as a journalist.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=40}} Later that year he moved to [[York, Upper Canada]], and the Lesslie family employed him at a [[bookselling]] and [[pharmacy|drugstore]] business.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/18/ 18]}} He wrote articles for the York ''Observer'' under the pseudonym Mercator.{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/496/mode/2up 497]}} The Lesslies opened a second shop in [[Dundas, Ontario|Dundas, Upper Canada]], and Mackenzie moved there to become its manager.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=41}} |

|||

Mackenzie initially found a job working on the [[Lachine Canal]] in [[Lower Canada]], then wrote for the ''[[Montreal Herald]]''. John Lesslie settled in [[York, Upper Canada]] (now Toronto). Mackenzie was soon employed at Lesslie's [[bookselling]]/[[pharmacy|drugstore]] business. Mackenzie began to write for the York ''Observer''. |

|||

In 1822, |

In 1822, his mother and his son joined Mackenzie in Upper Canada. Elizabeth invited Isabel Baxter to immigrate with them, as she had chosen Baxter to marry her son. Although they were schoolmates, Mackenzie and Baxter did not know each other well before meeting in Upper Canada.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/18/ 18]}} The couple wed in Montreal on July 1, 1822,{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=41}} and they had thirteen children.{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/496/mode/2up 497]}} Their daughter Isabel Grace Mackenzie was the mother of Canadian prime minister [[William Lyon Mackenzie King]]. |

||

==The ''Colonial Advocate'' and early years in York (1823–1827)== |

|||

Edward and John Lesslie opened a branch of their business in [[Dundas, Ontario|Dundas]], entering into a partnership with Mackenzie who moved to Dundas to be the store's manager. The store sold drugs, hardware, and general merchandise. Mackenzie also operated a circulating library. However, his relationship with the Lesslies soured and the partnership was dissolved in 1823. He moved to [[Queenston]] and established a business there. While there, he established a relationship with [[Robert Randal]], one of four members representing [[Lincoln County, Ontario|Lincoln County]] in the [[Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada]]. |

|||

===Creation of the ''Colonial Advocate''=== |

|||

The partnership between the Lesslies and Mackenzie ended in 1823. Mackenzie moved in 1824 to [[Queenston]], a town near [[Niagara Falls, Ontario|Niagara Falls]], to open a new general store. A few months later he sold his store and bought a printing press to create the ''[[Colonial Advocate]]'', a political newspaper. He refused government subsidies and relied on subscriptions, although he sent free copies to people he considered influential.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|pp=41–43}} The newspaper printed articles that supported the policies of the [[Reform movement (Upper Canada)|Upper Canadian Reform movement]]{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=15}} and criticized government officials.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/21/ 21]}} He organized a ceremony for the start of the construction of the [[Brock's Monument|memorial to Isaac Brock]], a British major-general who died in the [[War of 1812]]. Mackenzie sealed a capsule within the memorial's stonework containing an issue of the ''Colonial Advocate'', the ''Upper Canada Gazette'', some coins, and an inscription he had written.{{Sfn|Raible|2008|p=8}} Lieutenant governor [[Peregrine Maitland]] ordered the capsule's removal a few days after it was placed in the monument because of the ''Colonial Advocate''{{'}}s critical stance of the government.{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=18}} |

|||

In November 1824, Mackenzie relocated the paper and his family to York.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/22/ 22]}} Although the ''Colonial Advocate'' had the highest circulation among York newspapers, he still lost money on every issue because of low paid subscription numbers and late payments from readers.{{Sfn|Raible|1992|pp=22–25}} [[James Buchanan Macaulay]], a government official in York, accused Mackenzie of improper business transactions in 1826 and made jokes about Mackenzie's Scottish heritage and his mother.{{Sfn|Davis-Fisch|2014|p=32}} Mackenzie retaliated by pretending to retire from the paper on May 4, 1826,{{Sfn|Schrauwers|2009|p=73}} and published a fictitious meeting where contributors selected Patrick Swift as the new editor. Mackenzie used the Swift alias to continue publishing the ''Colonial Advocate''.{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=25}} |

|||

== The ''Colonial Advocate'' & the "Types Riot", 1824–26== |

|||

[[Image:WLMackenzie2.jpg|thumb|left|200px|Mackenzie]] |

|||

{{main|Colonial Advocate}} |

|||

===Types Riot=== |

|||

In 1824, Mackenzie established his most famous newspaper, the ''[[Colonial Advocate]]''. It was initially established to influence voters in the elections for the [[9th Parliament of Upper Canada]]. Mackenzie supported some characteristically British institutions, notably the [[British Empire]], [[primogeniture]] and the [[clergy reserves]], but he also praised American institutions in the paper. |

|||

{{Main|Types Riot}} |

|||

In the spring of 1826, Mackenzie published articles in the ''Colonial Advocate'' under the Swift pseudonym that questioned the governance of the colony and described the personal lives of government officials and their families.{{Sfn|Davis-Fisch|2014|p=36}} On June 8, 1826, rioters attacked the ''Colonial Advocate'' office. They harassed Mackenzie's family and employees, destroyed the printing press and threw its [[movable type]], the letters a printing press uses to print documents, into the [[Toronto Harbour|nearby bay]].{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/43/ 43]}}{{Sfn|Davis-Fisch|2014|p=33}} Mackenzie hired [[Marshall Spring Bidwell]]{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=94}} to represent him in a civil suit against eight rioters.{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=61}} |

|||

The ''Colonial Advocate'' had financial difficulties, and in November 1824, Mackenzie relocated the paper to York. There, he advocated in favour of the [[Reform Party (pre-Confederation)|Reform]] cause and became an outspoken critic of the [[Family Compact]], an upper-class clique which dominated the government of Upper Canada. However, the newspaper continued to face financial pressures: it had only 825 subscribers by the beginning of 1825, and faced stiff competition from another Reform newspaper, the ''[[Canadian Freeman]]''. As a result, Mackenzie had to suspend publishing the ''Colonial Advocate'' from July to December 1825. He purchased a new [[printing press]] in fall 1825 and resumed publication in 1826, now engaging in even more scurrilous attacks on leading Tory politicians such as [[William Allan (banker)|William Allan]], [[G. D'Arcy Boulton]], [[Henry John Boulton]], and [[George Gurnett]]. However, Mackenzie continued to amass debts, and in May 1826, he fled across the American border to [[Lewiston, New York]] to evade his creditors. |

|||

Bidwell argued that Mackenzie lost income from the damaged property and his inability to fulfill printing contracts.{{Sfn|Raible|1992|pp=103–104}} Upon cross-examination, Mackenzie's employees confirmed that Mackenzie authored Patrick Swift's editorials in the ''Colonial Advocate''.{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=106}} The court awarded Mackenzie £625 ({{Inflation|UK-GDP|start_year=1826|value=625|fmt=eq||r=-3|cursign=£}}) in damages which he used to pay off his creditors and restart production of his newspaper.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/45/ 45]}} One year after the riots, he documented the incident in a series of articles, which he later published as ''The History of the Destruction of the Colonial Advocate Press''.{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=149}} |

|||

A group of 15 young Tories, perhaps led by [[Samuel Jarvis]], took advantage of Mackenzie's absence to exact revenge for the attacks on the Tories printed in the ''Colonial Advocate''. Thinly disguising themselves as "[[Indigenous peoples of the Americas|Indians]]", they broke into the ''Colonial Advocate'''s office in broad daylight, smashed the printing press, and threw the type into [[Lake Ontario]]. The Tory magistrates did nothing to stop them and did not prosecute them afterwards. |

|||

==Reform member of the Legislative Assembly (1827–1834)== |

|||

Mackenzie took full advantage of the incident, returning to York and suing the perpetrators in a sensational trial, which propelled Mackenzie into the ranks of martyrs of Upper Canadian liberty, alongside [[Robert Thorpe (Canadian judge)|Robert Thorpe]] and [[Robert Fleming Gourlay]]. Mackenzie refused a settlement of £200 (approximately the value of the damage) and insisted on trial. His legal team, which included [[Marshall Spring Bidwell]], argued effectively and the jury returned a verdict of £625, far more than the amount of damage done to the press. |

|||

===Election to the Legislative Assembly=== |

|||

There are three implications of the Types riot according to historian Paul Romney. First, he argues the riot illustrates how the elite's self-justifications regularly skirted the rule of law they held out as their Loyalist mission. Second, he demonstrated that the significant damages Mackenzie received in his civil lawsuit against the vandals did not reflect the soundness of the criminal administration of justice in Upper Canada. And lastly, he sees in the Types riot “the seed of the Rebellion” in a deeper sense than those earlier writers who viewed it simply as the start of a highly personal feud between Mackenzie and the Family Compact. Romney emphasizes that Mackenzie’s personal harassment, the “outrage,” served as a lightning rod of discontent because so many Upper Canadians had faced similar endemic abuses and hence identified their political fortunes with his.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Romney|first=Paul|title=From the Types Riot to the Rebellion: Elite Ideology, Anti-legal Sentiment, Political Violence, and the Rule of Law in Upper Canada|journal=Ontario History|year=1987|volume=LXXIX|issue=2|pages=114}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Third Parliament Buildings 1834.jpg|thumb|right|alt=A painting of the Parliament Buildings of Upper Canada, depicted in brown in the background facing leftward while people mingle along a road and creek in the foreground.|[[John George Howard]]'s painting of the third Parliament Building in York, built between 1829 and 1832 at [[Front Street (Toronto)|Front Street]]]] |

|||

In December 1827, Mackenzie announced his candidacy to become one of the two representatives for the [[York County, Ontario|York County]] constituency in the [[10th Parliament of Upper Canada]].{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=75}} The Types Riot settlement was used to fund his campaign{{Sfn|Schrauwers|2009|p=85}} and he cited the incident as an example of corruption in Upper Canada.{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=151}} Mackenzie ran as an independent and refused to buy alcohol and treats for supporters or bribe citizens to vote for him, as was done by most politicians at this time.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/47/ 47]}} He published weekly articles in his newspaper called "The Parliament Black Book for Upper Canada, or Official Corruption and Hypocrisy Unmasked" where he listed accusations of wrongdoing by his opponents. He came in second in the election, becoming one of the representatives for York County.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=78}} |

|||

In parliament, Mackenzie chaired a committee that assessed the effectiveness of the post office and recommended that local officials should determine local postal rates. He also chaired a committee that evaluated the appointment process of [[returning officer|officials who administer elections]] in Upper Canada. He was a member of committees that looked at the banking and currency regulations of Upper Canada, the condition of roads, and the [[Church of England]]'s power.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=68}} Mackenzie opposed infrastructure projects until the province's debt was paid. He spoke against the [[Welland Canal]] Company, denouncing the financing methods of [[William Hamilton Merritt]], the company's financial agent, and its close links with the [[Executive Council of Upper Canada|Executive Council]], the advisory committee to the [[List of lieutenant governors of Ontario|lieutenant governor of Upper Canada]].{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/498/mode/2up 498]}} |

|||

Mackenzie took advantage of the money and fame which the trial had brought him to re-establish his business on sound financial footing. |

|||

In the election for the [[11th Parliament of Upper Canada]] in 1830, Mackenzie campaigned for legislative control of the budget, independent judges, an executive council that would report to the legislature, and equal rights for Christian denominations.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|pp=85–86}} He was re-elected to represent York County in the parliament. The Reform group lost their majority in the legislature, mostly because the [[Legislative Council of Upper Canada]] blocked the passage of their proposed legislation.{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|pp=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/498/mode/2up 498–499]}} In the new parliament, Mackenzie chaired a committee that recommended increased representation for Upper Canadian towns, a single day for voting in elections, and voting by ballot instead of voice.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=89}} |

|||

==Reform member of the Legislative Assembly, 1827–1834== |

|||

{{main|The Reform Movement (Upper Canada)}} |

|||

During a legislative break, Mackenzie travelled to [[Quebec City]] and met with Reform leaders in [[Lower Canada]]. He wanted to develop closer ties between the Reform leaders of each province and learn new techniques to oppose Upper Canada government policies.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/58/ 58]}} He gathered grievances from several communities in Upper Canada and planned to present these petitions to the [[Colonial Office]] in England.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/59/ 59]}} |

|||

Mackenzie now aligned himself with [[John Rolph (politician)|John Rolph]] in arguing that American-born settlers in Upper Canada should have the full rights of [[British subject]]s. Mackenzie played a role in organizing a committee to present grievances to the British government: the committee selected Robert Randal to travel to London to advocate on behalf of the American-born settlers. In London, Randal allied himself with British Reformer [[Joseph Hume]] in presenting the colonists' grievances to the [[Secretary of State for War and the Colonies]], [[F. J. Robinson, 1st Viscount Goderich|Lord Goderich]]. Goderich agreed that injustice was being done and instructed the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada to redress the grievances. This incident taught Mackenzie the efficacy of appealing directly to Britain. |

|||

=== Expulsions, re-elections, and appeal to the Colonial Office === |

|||

[[John Strachan]], who was then the [[Rector (ecclesiastical)|rector]] of York, a member of the [[Executive Council of Upper Canada]], and a prominent member of the Family Compact, also understood the efficacy of petitioning. He was in London the same year to seek a [[charter]] for his proposed King's College (now the [[University of Toronto]]) and to argue that the [[Church of England]] should receive the proceeds of sales of clergy reserves. Allying himself with [[Methodist]] minister [[Egerton Ryerson]], who felt that the Methodist Church should share in the proceeds of sale of the clergy reserves, Mackenzie declared himself opposed to Strachan's plans for Upper Canada. |

|||

Mackenzie criticized the Legislative Assembly in the ''Colonial Advocate'' and called the legislature a "sycophantic office".{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/62/ 62]}} For this, the assembly expelled him for [[libel]] of the character of the Assembly of Upper Canada.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/64/ 64]}} Mackenzie won the resulting by-election on January 2, 1832, by a vote of 119–1. Upon his victory, his supporters gifted him a gold medal worth £250 ({{Inflation|UK-GDP|start_year=1832|value=250|fmt=eq|r=-3|cursign=£}}) and organized a parade through the streets of York.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|pp=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/66/ 66–67]}} He was expelled again when he printed an article critical of the assemblymen who voted for his first expulsion.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/74/ 74]}} |

|||

Mackenzie won the second by-election on January 30 with 628 votes against two opponents—a [[Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario|Tory]] who received 23 votes and a moderate Reformer (who assumed his expulsion barred Mackenzie from becoming a legislator)—who received 96 votes.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=99}} Mackenzie toured Upper Canada to promote his policies and Tory supporters, unhappy with his agitation, tried to harm him. In [[Hamilton, Ontario|Hamilton]], [[William Johnson Kerr]] organized an assault of Mackenzie by three men. In York, twenty to thirty men stole a wagon he was using as a stage while another mob smashed the windows of the ''Colonial Advocate'' office.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/76/ 76]}} On March 23, 1832, Mackenzie's effigy was carried around York and burned outside the ''Colonial Advocate'' office while [[James FitzGibbon]], a [[magistrate]] in York, arrested Mackenzie in an attempt to placate the mob.{{Sfn|Wilton|1995|p=120}} Mackenzie feared for his life and stopped appearing in public until he left for England.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=99}} |

|||

=== Election to the Legislative Assembly === |

|||

[[File:Third Parliament Buildings 1834.jpg|thumb|right|350px|The third Parliament Building in York was built between 1829 and 1832 at [[Front Street (Toronto)|Front Street]].]] |

|||

Mackenzie declared his intentions to run in the elections for the [[10th Parliament of Upper Canada]] and entered into correspondence with Reformers such as Joseph Hume in England and [[John Neilson]] in Lower Canada. He ran in [[York County, Ontario|York County]], a riding dominated by colonists of American extraction. Mackenzie was one of four Reformers vying for York County's two seats – the others included two moderates (J. E. Small and [[Robert Baldwin]]) and one radical Reformer, [[Jesse Ketchum]]. During the campaign, Mackenzie published a "Black List" in the ''Colonial Advocate'', a series of attacks on his opponents, which led the ''Canadian Freeman'' and the Tories to dub him "William Liar Mackenzie". Nevertheless, Mackenzie's tactics were successful and he and Ketchum won the seat as part of a landslide that saw the Reformers win a majority of the seats. However, given the undemocratic nature of Upper Canada at this time, this win did not give the Reformers the right to form a cabinet, as the [[Executive Council of Upper Canada]] was still chosen by the [[List of Lieutenant Governors of Ontario|Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada]], [[Peregrine Maitland|Sir Peregrine Maitland]], who remained allied with the Family Compact. |

|||

In April 1832, Mackenzie travelled to London to petition the British government for reforms in Upper Canada.{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/500/mode/2up 500]}} He visited [[F. J. Robinson, 1st Viscount Goderich|Lord Goderich]], the [[Secretary of State for the Colonies]] of the United Kingdom, to submit the grievances he had collected in Upper Canada.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/81/ 81]}} In November 1832, Goderich sent instructions to the Upper Canada lieutenant governor [[John Colborne, 1st Baron Seaton|John Colborne]] to lessen the legislature's negative attitude against Mackenzie and reform the province's political and financial systems.{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/500/mode/2up 500]}} Tories in Upper Canada were upset that Mackenzie received a positive reception from Goderich and expelled him from the legislature; he was re-elected on November 26 by his constituents.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|pp=102–103}} Mackenzie published ''Sketches of Canada and the United States'' in 1833 to describe Upper Canada politics.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/38/ 38]}}{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/236/ 236]}} The book named thirty members of the Family Compact, the group that governed Upper Canada and controlled its policies.{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=187}} In November 1833, Mackenzie was expelled from the legislature again.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=104}} |

|||

The 10th Parliament opened in January 1829. Although there was speculation that Mackenzie would be elected [[Speaker of the Canadian House of Commons|speaker]], that honour went to Mackenzie's former lawyer, Marshall Spring Bidwell. Nevertheless, Mackenzie now had a prominent position from which to advocate for further reforms in the colony. He organized committees on agriculture, commerce, and the post office (he denounced the post office because it was run to make a profit for British businessmen and he wanted it to come under local control). He was also critical of the [[Bank of Upper Canada]], which was a monopoly and a [[limited liability company]] (Mackenzie distrusted limited liability companies and favoured [[Hard money (policy)|hard money]]). Later in the session, he also spoke out against the [[Welland Canal]] Company, denouncing its close links with the Executive Council and the financing methods of [[William Hamilton Merritt]]. |

|||

[[Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby|Edward Smith-Stanley]] replaced Goderich as the colonial secretary and reversed the Upper Canada reforms. Mackenzie was upset by this and, upon his return to Upper Canada in December 1833, renamed the ''Colonial Advocate'' to ''The Advocate'' to signal his displeasure with the province's colonial status.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=104}} During that time he was also re-elected to the legislature by the farmers in York County to fill the vacancy caused by his expulsion the previous month.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/96/ 96]}} He won the election by acclamation, but the other members of the legislature would not let him participate in their proceedings and expelled him again. The legislature barred him from sitting as an elected representative until after the 1836 legislative election.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|pp=104–105}} |

|||

In March 1829, Mackenzie traveled to the U.S. to study the new [[President of the United States|president]] [[Andrew Jackson]]. He admired the small size of the American government; the [[spoils system]] (whereby a party that wins an election can distribute government jobs to its supporters – unlike in Upper Canada, where those jobs remained controlled by the lieutenant governor no matter who won the election to the Assembly); and Jackson's opposition to the [[Second Bank of the United States]], which corresponded to Mackenzie's feelings towards the Bank of Upper Canada.{{Citation needed|date=June 2014}} Mackenzie was also impressed with Jackson personally when they met.{{Citation needed|date=June 2014}} Following Mackenzie's 1829 trip to the U.S., his political attitudes became increasingly pro-American and anti-British. |

|||

==Upper Canada politics (1834–1836)== |

|||

The 10th Parliament was dissolved in 1830 following the death of [[George IV of the United Kingdom|George IV]], and fresh elections were called. Unfortunately for Mackenzie and the Reformers, the mood of Upper Canada had changed somewhat from 1828 for a number of reasons: [[John Colborne, 1st Baron Seaton|John Colborne]], who replaced Peregrine Maitland as lieutenant governor in 1828, was less allied with John Strachan and the Family Compact; Colborne had encouraged immigration to Upper Canada from the British Isles, and these new settlers felt more loyalty to the home country than Upper Canadians born in the New World; and the Reform party had seemed to accomplish little during the two years they had controlled the Assembly. Consequently, the 1830 election saw the Reformers win only 20 of the 51 seats in the [[11th Parliament of Upper Canada|11th Parliament]], though both Mackenzie and Ketchum were returned as members for York. |

|||

===Municipal politics=== |

|||

In 1834, York changed its name to Toronto and held elections for its first city council. Mackenzie ran to be an [[alderman]] on the council to represent St. David's Ward. He won the election on March 27, 1834, with 148 votes, the highest among all candidates for alderman in the city. The other aldermen chose him to be [[List of mayors of Toronto|Toronto's first mayor]] by a vote of 10–8.{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/500/mode/2up 500]}}{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|pp=112–113}} The city council and Mackenzie approved a tax increase to build a boardwalk along King Street despite citizen backlash. He designed the first coat of arms for Toronto{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|pp=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/100/ 100–101]}} and presided as a judge for the city's Police Court, which heard cases of drunkenness and disorderly conduct, physical abuse of children and spouses and city bylaw violations.{{Sfn|Romney|1975|pp=422–423}} Mackenzie chose the newly built market buildings as Toronto's city hall and moved the offices of ''The Advocate'' into a southern wing of the complex.{{Sfn|Schrauwers|2007|p=212}} |

|||

In July 1834, Toronto declared a second [[cholera]] outbreak.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=116}} Mackenzie chaired the Toronto Board of Health in his role as mayor, which was tasked to implement the city's response to the outbreak. The board was divided between the Tories and the Reformers and they argued over Mackenzie's alleged interference with the work of health officers.{{Sfn|Romney|1975|p=424}}{{Sfn|Bilson|1980|p=[https://archive.org/details/darkenedhousecho0000bils/page/86 86]}} He remained on the board when it restructured two weeks after the start of the outbreak, although he was no longer its chairman.{{Sfn|Bilson|1980|p=[https://archive.org/details/darkenedhousecho0000bils/page/86 86]}} He brought people to the hospital until he was also infected with the disease{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=116}} and remained in his home until he recovered later that year.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/100/ 100]}} Mackenzie declined the nomination for alderman in the 1835 municipal election, printing in his paper that he wanted to focus on provincial politics. Reformers included him on their [[Ticket (election)|ticket]] for the election, and he received the fewest votes in his ward.{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/501/mode/2up 501]}}{{Sfn|Romney|1975|p=434}} |

|||

Disappointed at the setbacks to the Reform movement, Mackenzie became something of a troublemaker: he published vitriolic personal attacks on his political enemies in the ''Colonial Advocate''; he refused to join an agricultural society organized by the Tories, but attended their meetings and insisted on speaking; and he caused a ruckus in church when, as a member of the assembly, he had attended services at [[Cathedral Church of St. James (Toronto)|St. James's Cathedral]], the anchor congregation of the established [[Anglican]] church, as well as services in an independent Presbyterian church which opposed church-state connection. In summer, 1830, however, he joined [[St. Andrew's Church (Toronto)|St. Andrew's Presbyterian]], a congregation organized by Tories who supported the church-state connection. At St. Andrew's, he opposed the church-state connection, leading to a four-year battle within the congregation which ended with the departure of both Mackenzie and Reverend William Rintoul. |

|||

===Provincial politics=== |

|||

=== Expulsion and re-election === |

|||

[[File:The Seventh Report on Grievances.jpg|thumb|right|alt=A grey tablet is depicted with text and two portraits. The title states, "Mackenzie Presents the Seventh Report of Grievances to the Commons House of Assembly, Upper Canada 1835".|[[Emanuel Hahn]]'s "Mackenzie Panels" (1938) in the garden of [[Mackenzie House]] in Toronto. The panels are dedicated to Reformers who argued for responsible government in Upper Canada.]] |

|||

Meanwhile, the 11th Parliament met in January 1831 and Mackenzie continued to denounce abuses in the province. Influenced by the burgeoning [[Reform movement]] in England, he began calling for a review of representation in Upper Canada. He chaired a committee which recommended increased representation for Upper Canadian towns (as opposed to rural areas), a single day's vote, and voting by [[ballot]] instead of voice. |

|||

In the 1834 election for the [[12th Parliament of Upper Canada]], Mackenzie's York County constituency was split into four, each new section (known as a [[Riding (division)#Canada|riding]]) electing one member. Mackenzie was elected in the 2nd Riding of York by a vote of 334–178.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=117}}{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/500/mode/2up 501]}} After the election, he sold ''The Advocate'' to [[William John O'Grady]] because of its debt and to devote more time to his political career.{{Sfn|Schrauwers|2007|p=212}} |

|||

The legislature appointed Mackenzie as chairman of the Committee on Grievances.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/111/ 111]}} which questioned several members of the Family Compact on their work and government efficiency.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/114/ 114]}} The committee documented their findings in ''The Seventh Report from the Select Committee of the House of Assembly of Upper Canada on Grievances''. The report expressed Mackenzie's concern on the excessive power of the executive branch in Upper Canada and the campaigning of government officials for Tory politicians during elections. It also criticized companies that mismanaged funds given to them by the government and the salaries of officials who received [[patronage]] appointments.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|pp=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/122/ 122–123]}}{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|pp=123–124}} Mackenzie used the Committee on Grievances to investigate the Welland Canal Company. The Upper Canadian government partly owned the company and appointed directors to its board; in 1835 the legislature appointed Mackenzie.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/124/ 124]}} He discovered parcels of company land were given to Family Compact members or the Anglican Church for low prices, or swapped with land that was of lesser value. Mackenzie printed his investigation in a newspaper he created that summer in the Niagara peninsula called ''The Welland Canal''.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/124/ 124]}}{{Sfn|Lindsey|1862|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=we1YAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA137 137]}} |

|||

Unfortunately for Mackenzie, the Assembly was now in the control of his Tory enemies: [[Archibald McLean (judge)|Archibald McLean]] was speaker and [[Henry John Boulton]] was [[Solicitor General of Canada|solicitor general]] as well as an important member of the House. The Tories, however, also felt threatened: Lieutenant Governor Colborne was reforming the [[Legislative Council of Upper Canada|Legislative Council]] (traditionally dominated by the Family Compact) and paying less heed to John Strachan and the Executive Council. In the meantime, the [[United Kingdom general election, 1830|British election of 1830]] had brought Reformer [[Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey|Earl Grey]] to power in the United Kingdom, and Grey's government was suggesting giving power over certain revenues to the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada in exchange for a permanent [[civil list]]. Mackenzie supported giving control of revenues to the Legislative Assembly, but he opposed granting a permanent civil list, which he dubbed the "Everlasting Salary Bill". |

|||

When the new lieutenant governor [[Francis Bond Head]] arrived in Upper Canada, Mackenzie believed Bond Head would side with the Reform movement.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/131/ 131]}} After meeting Reformers, Bond Head concluded they were disloyal subjects of the British Empire. He wrote, "Mackenzie's mind seemed to nauseate its subjects" and "with the eccentricity, the volubility, and indeed the appearance of a madman, the tiny creature raved".{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|pp=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/133/ 133–134]}} Bond Head called an election in July 1836 and asked citizens to show loyalty to the British monarch by voting for Tory politicians.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|pp=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/139/ 139–140]}} Bond Head's campaigning was successful and Reformers across the province lost their elections, [[Edward William Thomson]] defeating Mackenzie to represent the 2nd Riding of York in the [[13th Parliament of Upper Canada|13th Parliament]].{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=133}} Mackenzie was upset over this loss, weeping in a neighbour's home while supporters consoled him. Feeling disenchanted with the Upper Canada political system, Mackenzie created a new newspaper called the ''Constitution'' on July 4, 1836. The paper accused the government and their supporters of corruption and encouraged citizens to prepare "for nobler actions than our tyrants can dream of".{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|pp=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/143/ 143–144]}} |

|||

Mackenzie spent 1831 traveling throughout Upper Canada collecting signatures for petitions to redress Upper Canadian grievances. He also met with Lower Canadian Reformers. New Irish immigrants and those of American descent were particularly supportive of Mackenzie. |

|||

==Upper Canada Rebellion (1837–1838)== |

|||

In the legislative session that opened in November 1831, Mackenzie demanded investigations of the Bank of Upper Canada, the Welland Canal, King's College, the revenues, and the chaplain's salary. Taking his language a step further, in the ''Colonial Advocate'' he denounced the Legislative Assembly as a sycophantic office. This was too much for the Assembly, and in December 1831, they voted to expel Mackenzie by a vote of 24 to 15. |

|||

{{Main|Rebellions of 1837–1838|Upper Canada Rebellion}} |

|||

===Planning=== |

|||

Mackenzie's expulsion helped him to recreate his reputation as a martyr for Upper Canadian liberty. On the day the Assembly voted to expel him, a mob of several hundred stormed the Assembly, demanding that Colborne dissolve the Assembly and call fresh elections. Colborne refused, but on January 2, 1832, Mackenzie won the byelection called to replace him by a vote of 119 to 1. A parade of 134 sleighs down [[Yonge Street]], accompanied with [[bagpipes]], celebrated the occasion. |

|||

In March 1837 the British government rejected reforms in Upper Canada and reconfirmed the authoritarian power of the lieutenant governor. This ended Mackenzie's hope that the British government would enact his desired reforms in the colony.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=134}} In July 1837, Mackenzie organized a meeting with Reformers dubbed the Committee of Vigilance and Mackenzie was selected as the committee's corresponding secretary.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/148/ 148]}} Mackenzie published a critique of Bond Head describing him as a tyrant upholding a corrupt government.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=141}} Mackenzie spent the summer of 1837 organizing vigilance committees throughout Upper Canada and proposed self-government for the Upper Canada colony instead of governance by a distant British Parliament.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/148/ 148]}}{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=142}} He liked attending these meetings because they confirmed that his politics were aligned with Upper Canadians who were not involved with governing the colony.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|pp=133–134}} He attracted large crowds but also faced physical attacks from Family Compact supporters.{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/501/mode/2up 501]}} During the fall of 1837, he visited Lower Canada and met with their rebel leaders, known as the [[Patriote movement|Patriotes]].{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=144}} |

|||

On October 9, 1837, Mackenzie received a message from the Patriotes asking him to organize an attack on the Upper Canada government.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/154/ 154]}} Mackenzie gathered Reformers the following month and proposed seizing control of the Upper Canada government by force, but the meeting did not reach a consensus.{{Sfn|Schrauwers|2009|p=197}} He tried to convince [[John Rolph (politician)|John Rolph]] and [[Thomas David Morrison]], two other Reform leaders, to lead a rebellion. He cited that Upper Canadian troops were sent to suppress the [[Lower Canada Rebellion]] and a quick attack on Toronto would allow rebels to seize control of the government before a militia could be organized against them. The two Reformers asked Mackenzie to determine the level of support in the countryside for the revolt. He travelled north and convinced rural Reform leaders that they could forcefully take control of the government. They decided that the rebellion would begin on December 7, 1837, and that [[Anthony Anderson (Upper Canada Rebellion leader)|Anthony Anderson]] and [[Samuel Lount]] would lead the assembled men. Mackenzie relayed this plan to Rolph and Morrison upon his return to Toronto.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|pp=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/157/ 157–159]}} |

|||

Nevertheless, on January 7, 1832, Henry John Boulton and [[Allan MacNab]] again succeeded in getting through a motion to expel Mackenzie from the Assembly on the basis of new attacks Mackenzie had published in the ''Colonial Advocate''. A second by-election was called, and Mackenzie won by a landslide for a second time. When he was again expelled from the Assembly, Mackenzie appealed to London for redress; in response, the Tories organized the British Constitutional Society. 1832 was a time of great political turmoil in Upper Canada. When the Roman Catholic bishop [[Alexander Macdonell (bishop)|Alexander Macdonell]] organized a rally in York to demonstrate Catholic support for the Tories, Mackenzie and his supporters disrupted the meeting. In [[Hamilton, Ontario|Hamilton]], Tory magistrate [[William Johnson Kerr]] arranged to have Mackenzie beaten by thugs. On March 23, Catholic Irish apprentices in York, furious at Mackenzie's attack on Bishop Macdonnell, pelted Mackenzie and Ketchum with garbage; riots broke out in York later that day and Mackenzie might have been killed by the crowd, but for the intervention of Tory magistrate [[James FitzGibbon]]. Following the riots, Mackenzie went into hiding. |

|||

Mackenzie wrote a [[declaration of independence]] and printed it at [[Hoggs Hollow]] on December 1. A Tory supporter reported the declaration to authorities, and a warrant was issued for Mackenzie's arrest. Upon his return to Toronto, Mackenzie discovered that Rolph had sent him a warning about the warrant. When the messenger could not find Mackenzie, he relayed the warning to Lount instead, who responded by marching a group of men towards Toronto to begin the rebellion. Mackenzie attempted to stop Lount but could not reach him in time.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|pp=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/162/ 162–165]}} |

|||

=== Appeal to the Colonial Office === |

|||

In April 1832, Mackenzie travelled to England to petition the British government for redress. In London, he met with reformers Joseph Hume and [[John Arthur Roebuck]] and wrote in the ''[[Morning Chronicle]]'' to influence British public opinion in his favour. Lord Goderich, serving as Secretary of State for War and the Colonies for a second time, received Mackenzie, along with Egerton Ryerson and [[Denis-Benjamin Viger]], a member of the [[Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada]], on July 2, 1832. Mackenzie felt that Goderich gave him a fair hearing (Goderich suggested that Mackenzie should send him a report on Upper Canada). Mackenzie remained in London for some time, and was present in the galleries for the debate on the [[Reform Act 1832]]. He also wrote a book during this period, ''Sketches of Canada and the United States'', designed to acquaint the British public with his grievances. |

|||

===Rebellion and retreat to the United States=== |

|||

In Mackenzie's absence, the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada voted to expel him a third time; on this occasion, he was re-elected by acclamation. |

|||

{{Main|Battle of Montgomery's Tavern}} |

|||

Lount's men arrived at Montgomery's Tavern on the night of December 4.{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/502/mode/2up 503]}} Later that night Anderson was killed by [[John Powell (Canadian politician)|John Powell]] during a scouting expedition.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/168/ 168]}}{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|pp=153–154}} Lount refused to lead the rebellion by himself so the group chose Mackenzie as their new leader.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/170/ 170]}} |

|||

On November 8, 1832, Lord Goderich sent a dispatch to Lieutenant Governor Colborne, which arrived in January 1833, instructing him to make certain financial and political improvements in Upper Canada, and instructing him to rein in the Assembly's vendetta against Mackenzie. The House of Assembly and the Legislative Council were furious at this interference in Upper Canadian politics, and in February again deprived Mackenzie of his vote in the House and refused to call fresh elections. When news of this insubordination reached Lord Goderich, he dismissed Attorney General Boulton and Solicitor General Hagerman. Lieutenant Governor Colborne protested and Boulton and Hagerman travelled to London to make their case. |

|||

Mackenzie gathered the rebels at noon on December 5 and marched them towards Toronto.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/171/ 171]}} At Gallows Hill, Rolph and [[Robert Baldwin]] announced the government's offer of full amnesty for the rebels if they dispersed immediately. Mackenzie and Lount asked that a convention be organized to discuss the province's policies and for the truce to be presented as a written document.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=155}} Rolph and Baldwin returned, stating the government had withdrawn their offer.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/174/ 174]}} Mackenzie grew increasingly erratic and spent the evening punishing Tory families by burning down their houses and trying to force the Upper Canada Postmaster's wife to cook meals for his rebellion.{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/502/mode/2up 503]}}{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/175/ 175]}} Mackenzie tried marching the troops towards the city, but along the way a group of men fired at the rebels, causing them to flee.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/178/ 178]}} |

|||

In April 1833, Lord Goderich was replaced as Secretary of State for War and the Colonies by the more conservative [[Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby|Lord Stanley]]. Lord Stanley reappointed Hagerman as solicitor general and named Boulton [[chief justice]] of [[Colony of Newfoundland|Newfoundland]]. |

|||

Mackenzie spent the next day robbing a [[mail coach]] and kidnapping passing travellers to question them about the revolt.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/181/ 181]}} He reassured the troops at Montgomery's Tavern that 200 men were going to arrive from [[Buffalo, New York]], to help with the rebellion. Mackenzie also sent a letter to a newspaper called ''The Buffalo Whig and Journal'' asking for troops from the United States.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA17 17]}} |

|||

This incident contributed to Mackenzie's decaying faith in Great Britain. Returning to Upper Canada, in December 1833 he renamed the ''Colonial Advocate'' simply ''The Advocate'', a sign that he no longer valued the tie to Great Britain. On December 17, 1833, he was again expelled from the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada, and later in the month was again re-elected: twice, he was refused admission to the House, and in the end it was only Lieutenant Governor Colborne's intervention which resulted in Mackenzie finally being able to take his seat. |

|||

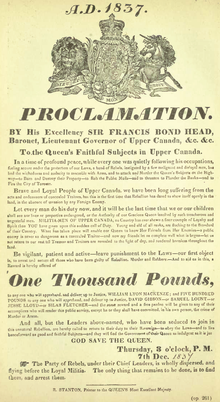

[[File:1837 Proclamation.png|thumb|right|alt=A poster with the coat of arms of the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada at the top and "Proclamation" in a large font. Further writing describes the warrant for William Lyon Mackenzie in 1837| A proclamation posted on December 7, 1837, offering a reward of £1,000 for the capture of William Lyon Mackenzie]] On December 7, government forces arrived at Montgomery's Tavern and fired towards the rebel position. Mackenzie was one of the last to flee north, leaving his papers and cloak behind. He met with rebel leaders who agreed the rebellion was over and that they needed to flee Upper Canada.{{Sfn|Raible|2016|pp=133–134}} Bond Head issued a warrant and a £1,000 ({{Inflation|UK-GDP|start_year=1837|value=1000|fmt=eq|r=-3|cursign=£}}) reward for Mackenzie's apprehension.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|pp=158–159}} Mackenzie travelled to the [[Niagara River]] and entered the United States by boat.{{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/192/ 192]}} |

|||

Mackenzie broke with his old ally Egerton Ryerson in late 1833. In 1832, Ryerson had negotiated an agreement between the British and Canadian Methodists, and the Methodists agreed to take state aid. Ryerson began attacking British Reformer Joseph Hume in the pages of the Methodist newspaper, ''[[The Christian Guardian]]''. Mackenzie disagreed with Ryerson's positions and broke with him at this point. |

|||

===Attempted invasion from the United States=== |

|||

==Mayor of Toronto, 1834== |

|||

{{main|Patriot War}} |

|||

[[File:Second market in York (Toronto).jpg|thumb|left|Second market in York (Toronto)]] |

|||

The township of York, which until 1793 had been known as "Toronto", [[Municipal corporation|incorporated]] as a city (meaning it received local self-government) on March 6, 1834, taking the name of "the City of Toronto" to distinguish it from New York City and the dozen other settlements named 'York' in Upper Canada. The Tories and the Reformers fielded candidates for Toronto's first municipal election, held on March 27, 1834, with the Reformers winning a majority on the [[Toronto City Council]]. Mackenzie was elected as an [[alderman]]. The City Council then met to decide who should become mayor. Mackenzie, after being nominated by [[Franklin Jackes]], defeated John Rolph in the vote and thereby became the first [[mayor of Toronto]]. |

|||

Mackenzie arrived in Buffalo on December 11, 1837,{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=163}} and gave a speech outlining his desire for Upper Canada to be independent of Britain.{{Sfn|Flint|1971|p=168}} He blamed the failed rebellion on a lack of weapons and supplies. [[Josiah Trowbridge]], Buffalo's mayor, and a newspaper called the ''Commercial Advertiser'' interpreted the speech as a rallying cry for help with the rebellion.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA17 17–18]}} |

|||

Mackenzie was largely ineffectual as a mayor. He got rid of Tory officials and replaced them with his supporters, but did not manage to deal with the city's excessive debt or institute much needed public works. Rather, Mackenzie's management style provoked frequent quarrels on the City Council, and by summer 1834, it was apparent that the Reformers would be able to accomplish nothing in the municipal government. It was therefore not surprising when the Tories won handily in the 1835 City Council elections and [[Robert Baldwin Sullivan]] replaced Mackenzie as mayor. |

|||

On December 12, Mackenzie asked [[Rensselaer Van Rensselaer]] to lead an invasion of Upper Canada. Van Rensselaer would lead Patriot forces, composed of volunteers who sympathized with the cause and were living in the United States. Rebel leaders chose Van Rensselaer because the [[Van Rensselaer family|Van Rensselaer family name]] would bring respectability to their campaign, [[Stephen Van Rensselaer|his father]] had been a successful military general in the War of 1812, and he claimed to have military experience.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA18 18–19]}} Van Rensselaer, Mackenzie and 24 supporters occupied [[Navy Island]] on December 14 and Mackenzie proclaimed the [[Republic of Canada|State of Upper Canada]] on the island, declared Upper Canada's separation from the [[British Empire]], proclaimed himself appointed chairman of its new government and wrote a draft for the constitution of the new state.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA17 17]}}{{Sfn|Gates|1996|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA21 21–22]}} Van Rensselaer planned to use the island as a staging point to invade the Upper Canadian mainland, but this was stopped when their ship, the ''Caroline'', was destroyed by British forces in the [[Caroline affair|''Caroline'' affair]].{{Sfn|Gates|1996|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA23 23]}} On January 4, Mackenzie travelled to Buffalo to seek medical help for his wife. On the way he was arrested for violating the [[Neutrality Act of 1794|Neutrality Act]], a law that prohibited participating in an invasion of a country against which the US government had not declared war.{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=167}}{{Sfn|Gates|1996|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA27 27]}} He was released on $5,000 ({{Inflation|US-GDP|start_year=1837|value=5000|fmt=eq|r=-3|cursign=$}}) bail, paid by three men in Buffalo,{{Sfn|Gates|1996|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA27 27]}} and returned to Navy Island in January.{{Sfn|Flint|1971|p=168}} British forces invaded the island on January 4, 1838, and the rebels dispersed to the American mainland.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA17 17]}} |

|||

==Upper Canadian politics 1835–1836== |

|||

{{main|The Reform Movement (Upper Canada)}} |

|||

Mackenzie wanted Canadians to lead the next invasion but still receive American assistance.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA28 28]}} When Van Rensselaer attempted an invasion of [[Kingston, Ontario|Kingston]] from [[Hickory Island]], Mackenzie refused to participate, citing a lack of confidence in the mission's success.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA31 31]}} Patriot forces near Detroit attempted to invade Upper Canada but were repelled by British forces. Mackenzie stopped recruiting for the Patriots to avoid ridicule.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA35 35]}} |

|||

[[File:The Seventh Report on Grievances.jpg|thumb|right|[[Emanuel Hahn]]'s "Mackenzie Panels" (1938) in the garden of [[Mackenzie House]] in Toronto. The panel shows William Lyon Mackenzie presenting his historic Seventh Report of Grievances to the House of Assembly of Upper Canada. Names of those executed during the repression that followed defeat of the rebellion appear on one of the panels, as do profiles of the two rebels who met their death on the scaffold in Toronto: [[Samuel Lount]] and [[Peter Matthews (rebel)|Peter Matthews]].]] |

|||

==Years in the United States (1838–1849)== |

|||

In May 1834, Mackenzie published a letter from British Reformer Joseph Hume in the pages of the ''Advocate'' in which Hume called for independence for the colonies, even by means of violent rebellion if necessary. Mackenzie was criticized for printing this letter (not only by Tories but also by some Reformers such as Egerton Ryerson) but it charted a course that Mackenzie would soon be travelling himself. |

|||

===Support for Patriots and ''Mackenzie's Gazette''=== |

|||

Mackenzie and his wife arrived in New York City and launched ''Mackenzie's Gazette'' on May 12, 1838, after soliciting subscriptions from friends.{{Sfn|Gates|1986|p=117}} Its early editions supported the Patriots and focused on Canadian topics, but pivoted to American politics in August 1838.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA35 35–36]}}{{Sfn|Gates|1996|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA44 44–45]}} He suspended publication of his paper in the fall of 1838 and moved to [[Rochester, New York|Rochester]] to rebuild the Patriot forces by creating the Canadian Association.{{Sfn|Gates|1986|pp=127–128}} The association struggled to attract Canadian members and unsuccessfully fundraised for Mackenzie to publish an account of the Upper Canada Rebellion. The money was reallocated to Mackenzie's defence fund for his upcoming trial.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA58 58–59]}} He restarted ''Mackenzie's Gazette'' in Rochester on February 23, 1839.{{Sfn|Gates|1986|p=128}} |

|||

===Neutrality law trial=== |

|||

In elections held in October 1834, the Reformers won a majority in the [[12th Parliament of Upper Canada]] and Mackenzie was again elected as member for York (though at this point he was still serving as mayor of Toronto). Determined to dedicate himself full-time to his duties in the Legislative Assembly, in November 1834, he turned over the ''Advocate'' to fellow Reformer [[William John O’Grady]]. |

|||

The trial for Mackenzie's violation of American neutrality laws began on June 19, 1839; he [[Pro se legal representation in the United States|represented himself]] in the proceedings. The district attorney argued that Mackenzie recruited members, established an army, and stole weapons for an invasion. Mackenzie contended that Britain and the United States were at war because the British destroyed an American ship in the ''Caroline'' affair and the Neutrality Act did not apply.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA61 61–62]}} Mackenzie wanted to submit evidence that the Upper Canadian Rebellion was a civil war, as a person cannot be convicted of violating the Neutrality Act if the country is engaged in a civil war. The judge refused to allow this evidence because, according to American law, only the United States Congress can declare if a country is in a civil war, which they did not do. Mackenzie was frustrated and did not call further witnesses.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA62 62–63]}} |

|||

The judge sentenced Mackenzie to eighteen months in jail and a $10 ({{Inflation|US-GDP|start_year=1839|value=10|fmt=eq|cursign=$}}) fine. Mackenzie did not appeal the ruling after consulting with lawyers.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA64 64]}} He said after the trial that he was depending upon key witnesses to give testimony, but they did not come to the courtroom. He also denounced the application of neutrality laws, wrongly stating the law had not been applied for nearly fifty years.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA61 61]}} |

|||

Upon meeting in January 1835, the 12th Parliament of Upper Canada voted to reverse all of Mackenzie's previous expulsions from the Legislative Assembly. Mackenzie chaired a special committee of the Legislative Assembly to detail the grievances of Upper Canada, which resulted in the production of the ''Seventh Report on Grievances'',<ref name=seventhreport>[https://archive.org/details/seventhreportfro00uppe "The seventh report from the Select Committee of the House of Assembly of Upper Canada on grievances..."]</ref> an extensive compilation of major and minor grievances with proposed solutions. The Assembly also appointed Mackenzie as a government director of the Welland Canal Company and Mackenzie produced an exhaustive report on the company's financial situation, though he stopped short of accusing the company's directors of full-blown dishonesty. |

|||

===Imprisonment=== |

|||

Mackenzie's reform proposals resulted in no action, however, since [[Francis Bond Head|Sir Francis Bond Head]], who was appointed Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada in 1836, received instructions from the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, [[Charles Grant, 1st Baron Glenelg|Lord Glenelg]], to disregard the ''Seventh Report on Grievances''. Although Lieutenant Governor Head was initially seen as reform-minded (he appointed Robert Baldwin and John Rolph to the Executive Council), he soon quarrelled with the Reformers in the Legislative Assembly and dissolved the Assembly in May 1836. |

|||

[[File:1841 sketch of Caroline Affair by Mackenzie-employed artist.png|thumb|left|alt=A black-and-white sketch of a boat on fire and a man floating in a river. A flag with the word "Liberty" is flying in the background.|The cover image for ''The Caroline Almanack'', drawn by Mackenzie, depicting the ''Caroline'' affair]]Mackenzie was imprisoned on June 21, 1839.{{Sfn|Gates|1986|p=131}} He chose to be jailed in Rochester to be closer to his family. He published ''The Caroline Almanack'' and drew an image of the ''Caroline'' affair for the cover. He also published issues of the ''Gazette'', in which he described the trial and appealed for his release.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA64 64–65]}} Later issues reported on the upcoming New York state elections, the [[1840 United States elections]] and the ''[[Durham Report]]''.{{Sfn|Gates|1986|p=131}} |

|||

While imprisoned, Mackenzie's mother became sick. He was denied permission to see her, so [[John Montgomery (tavern-keeper)|John Montgomery]], the tavern keeper of Montgomery's Inn during the Upper Canada Rebellion, arranged for him to be a witness at a trial. {{Sfn|Kilbourn|1967|p=[https://archive.org/details/firebrandwilliam00kilb/page/210/ 210]}} Montgomery convinced the state attorney to hold the trial in Mackenzie's house, and the magistrate stalled the proceedings so Mackenzie could visit his mother. She died a few days later, and Mackenzie witnessed the funeral procession from his prison window.{{Sfn|Raible|1992|p=37}} Mackenzie encouraged friends and readers of his newspaper to petition President [[Martin Van Buren]] for a [[pardon]], which would release him from imprisonment. Over 300,000 people signed petitions that were circulated in New York State, Michigan, and Ohio.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA70 70–71]}}{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=169}} Van Buren did not want others to believe he supported Mackenzie's actions and increase hostilities with Britain, so he was reluctant to grant this pardon.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA70 70–71]}} Democrats submitted petitions to the United States Congress calling for Mackenzie's release. Van Buren believed it was politically easier to release Mackenzie from prison than explain his imprisonment to fellow Democrats, so on May 10, 1840, Van Buren granted Mackenzie a pardon. {{Sfn|Gates|1986|p=134}} |

|||

In the run-up to the July 1836 election for the [[13th Parliament of Upper Canada]], Head actively campaigned on behalf of the Tories against the Reformers, rallying the people behind the cause of loyalty to the British Empire. As a result, a large Tory majority was returned to the Assembly and Mackenzie lost his seat to [[Edward William Thomson]]. |

|||

===After the pardon=== |

|||

==Upper Canada Rebellion, 1837–1838== |

|||

After a summer hiatus, the ''Gazette'' denounced all invasions into Canada and supported Van Buren's re-election. The paper's subscriptions continued to decline and the last issue was published on December 23, 1840.{{Sfn|Gates|1986|pp=134–135}} In April, he launched ''The Rochester Volunteer'' and printed articles criticising Canadian Tory legislators.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA88 88]}} The ''Volunteer'' stopped production in September 1841 because the newspaper was not profitable or politically influential. Mackenzie moved back to New York City in June 1842.{{Sfn|Armstrong|Stagg|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/trent_0116403538022_9/page/504/mode/2up 505]}} |

|||

{{campaignbox Upper Canada Rebellion}} |

|||

{{main|Rebellions of 1837|Upper Canada Rebellion}} |

|||

Mackenzie worked for several publishers but refused to accept a job as an editor. He became an [[American citizen]] in April 1843.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA100 100–102]}}{{Sfn|Sewell|2002|p=170}} He wrote a biography of 500 Irish patriots entitled, ''The Sons of the Emerald Isle''; the first volume was published on February 21, 1844. The goal of the series was to stop nativist attitudes towards immigrants to North America by reminding Americans that their ancestors were also immigrants. Mackenzie attended the founding meeting of the National Reform Association in February 1844. Its goal was to distribute public lands to people who would live on the property, limit the amount of land an individual could own, and outlaw the confiscation of free homesteads given to settlers. He spoke at many meetings and remained on the association's central committee until July 1844.{{Sfn|Gates|1996|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GNaXwTY03v8C&pg=PA111 111–112]}} |

|||

===Planning=== |

|||