Laos: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m wrote out 3 Tags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Country in Southeast Asia}} |

|||

{{about|the country}} |

|||

{{About|the country||Laos (disambiguation)|and|Lao (disambiguation)}} |

|||

{{EngvarB|date=September 2014}} |

|||

{{pp-move}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=September 2014}} |

|||

{{ |

{{Use British English|date=February 2022}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=September 2024}} |

|||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

|||

{{Infobox country |

{{Infobox country |

||

|conventional_long_name = Lao People's Democratic Republic |

| conventional_long_name = Lao People's Democratic Republic |

||

| common_name = Laos |

|||

|native_name = {{unbulleted list |{{nobold|{{lang|lo|ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ}}}} |''Sathalanalat Paxathipatai Paxaxon Lao''}} |

|||

| native_name = {{ubl|{{native name|lo|ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ<wbr />}}|{{transliteration|lo|Sathalanalat Paxathipatai Paxaxon Lao}}}} |

|||

|common_name = Laos |

|||

|image_flag = Flag of Laos.svg |

| image_flag = Flag of Laos.svg |

||

|image_coat |

| image_coat = Emblem of Laos.svg |

||

| coa_size = 90 |

|||

|symbol_type = Emblem |

|||

| symbol_type = Emblem |

|||

|religion = [[Buddhism]] |

|||

| national_motto = {{lang|lo|ສັນຕິພາບ ເອກະລາດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ເອກະພາບ ວັດທະນະຖາວອນ}}<br />{{transliteration|lo|Santiphap, Ekalat, Paxathipatai, Ekaphap, Vatthanathavon}}<br />"Peace, Independence, Democracy, Unity and Prosperity" |

|||

|image_map = Laos_ASEAN.PNG |

|||

| national_anthem = {{lang|lo|ເພງຊາດລາວ}}<br />{{transliteration|lo|[[Pheng Xat Lao]]}}<br />"Hymn of the Lao People"{{parabr}}{{center|[[File:National Anthem of Laos.ogg]]}} |

|||

|map_caption = Location of Laos (dark green) in [[ASEAN]] (light green) and Asia |

|||

| image_map = {{Switcher|[[File:Laos (orthographic projection).svg|frameless]]|Show globe|[[File:Location Laos ASEAN.svg|250px|upright=1.15|frameless]]|Show map of ASEAN|default=1}} |

|||

|national_motto = ສັນຕິພາບ ເອກະລາດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ເອກະພາບ ວັດທະນາຖາວອນ<br/>{{small|"Peace, independence, democracy, unity and prosperity"}} |

|||

| map_caption = {{map caption |location_color=green |region=[[ASEAN]] |region_color=dark grey |legend=Location Laos ASEAN.svg}} |

|||

|national_anthem = ''[[Pheng Xat Lao]]''<br/>{{small|''Lao National Anthem''}}<br/><center>[[File:National Anthem of Laos.ogg]]</center> |

|||

| capital = [[Vientiane]] |

|||

|official_languages = [[Lao language|Lao]] |

|||

| coordinates = {{Coord|17|58|N|102|36|E|type:city}} |

|||

|national_languages = [[French language|French]] |

|||

| largest_city = capital |

|||

|languages_type = Spoken languages |

|||

| official_languages = [[Lao language|Lao]] |

|||

|languages = {{hlist|[[Thai language|Thai]]|[[Hmong languages|Hmong]]|[[Khmu language|Khmu]]}} |

|||

| recognised_languages = |

|||

|demonym = [[Lao people|Laotian<br/>Lao]] |

|||

| languages_type = Spoken languages |

|||

|ethnic_groups = |

|||

| languages = {{hlist|[[Lao language|Lao]]|[[Khmu language|Khmu]]|[[Hmong language|Hmong]]|[[Phu Thai language|Phu Thai]]|[[Tai language|Tai]]|[[English language|English]]|[[French language|French]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.studycountry.com/guide/LA-language.htm|title=The Languages spoken in Laos|website=Studycountry|access-date=16 September 2018|archive-date=25 February 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210225003905/https://www.studycountry.com/guide/LA-language.htm|url-status=live}}</ref>}} |

|||

{{unbulleted list |

|||

| ethnic_groups = {{unbulleted list |

|||

| 55% [[Lao people|Lao]] |

|||

| 53.2% [[Lao people|Lao]] |

|||

| 11% [[Khmu people|Khmu]] |

|||

| 9.2% [[Hmong people|Hmong]] |

|||

| 26% others<sup>a</sup> |

|||

| 3.4% [[Phu Thai language#Speakers|Phu Thai]] |

|||

| 3.1% [[Tai people|Tai]] |

|||

| 2.5% Makong |

|||

| 2.2% [[Katang people|Katang]] |

|||

| 2.0% [[Lu people|Lue]] |

|||

| 1.8% [[Akha people|Akha]] |

|||

| 11.6% other{{efn|Including [[List of ethnic groups in Laos|over 100 smaller ethnic groups]]}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

| ethnic_groups_year = 2015<ref name="Census2015">{{cite web|url=https://lao.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/PHC-ENG-FNAL-WEB_0.pdf|title=Results of Population and Housing Census 2015|publisher=Lao Statistics Bureau|access-date=1 May 2020|archive-date=8 March 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210308153132/https://lao.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/PHC-ENG-FNAL-WEB_0.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

|ethnic_groups_year = 2005<ref name="cia.gov"/> |

|||

| demonym = {{hlist|[[Lao people|Lao]]|[[Demographics of Laos|Laotian]]}} |

|||

|capital = [[Vientiane]] |

|||

| government_type = Unitary [[Marxism–Leninism|Marxist–Leninist]] one-party [[socialist state|socialist republic]] |

|||

|latd=17 |latm=58 |latNS=N |longd=102 |longm=36 |longEW=E |

|||

| leader_title1 = [[General Secretary of the Lao People's Revolutionary Party|LPRP General Secretary]] and [[President of Laos|President]] |

|||

|largest_city = capital |

|||

| leader_name1 = [[Thongloun Sisoulith]] |

|||

|government_type = [[Marxism-Leninism|Marxist-Leninist]] [[single-party state]] |

|||

| |

| leader_title3 = [[Prime Minister of Laos|Prime Minister]] |

||

| leader_name3 = [[Sonexay Siphandone]] |

|||

|leader_name1 = [[Choummaly Sayasone]] |

|||

|leader_title2 = [[ |

| leader_title2 = [[Vice President of Laos|Vice President]] |

||

|leader_name2 = [[ |

| leader_name2 = [[Bounthong Chitmany]]<br />[[Pany Yathotou]] |

||

| |

| leader_title4 = [[President of the National Assembly of Laos|President of the National Assembly]] |

||

| leader_name4 = [[Saysomphone Phomvihane]] |

|||

|leader_name3 = [[Pany Yathotou]] |

|||

| legislature = [[National Assembly (Laos)|National Assembly]] |

|||

|leader_title4 = [[Lao Front for National Construction|President of<br/>Construction]] |

|||

| sovereignty_type = [[History of Laos|Formation]] |

|||

|leader_name4 = [[Sisavath Keobounphanh]] |

|||

| established_event1 = [[Lan Xang|Kingdom of Lan Xang]] |

|||

|legislature = [[National Assembly (Laos)|National Assembly]] |

|||

| established_date1 = 1353–1707 |

|||

|sovereignty_type = [[History of Laos|Formation]] |

|||

| established_event2 = Kingdoms of [[Kingdom of Luang Phrabang|Luang Prabang]], [[Kingdom of Vientiane|Vientiane]] and [[Kingdom of Champasak|Champasak]] |

|||

| established_event1 = [[Lan Xang|Kingdom of Lan Xang]] |

|||

| established_date2 = 1707–1778 |

|||

| established_date1 = 1354–1707 |

|||

| established_event3 = Vassals of [[Rattanakosin Kingdom (1782–1932)|Siam]] |

|||

| established_event2 = [[Kingdom of Luang Phrabang|Luang Phrabang]], [[Kingdom of Vientiane|Vientiane]] and [[Kingdom of Champasak|Champasak]] |

|||

| established_date3 = 1778–1893 |

|||

| established_date2 = 1707–1778 |

|||

| established_event4 = [[French protectorate of Laos|French protectorate]] |

|||

| established_event3 = Vassal of [[Thonburi Kingdom|Thonburi]] and [[Rattanakosin Kingdom|Siam]] |

|||

| established_date4 = 1893–1953 |

|||

| established_date3 = 1778–893 |

|||

| established_event5 = [[Lao Issara|Free Lao Movement]] |

|||

| established_event4 = [[Chao Anu Rebellion|War of Succession]] |

|||

| established_date5 = 1945–1949 |

|||

| established_date4 = 1826–8 |

|||

| established_event6 = [[French Protectorate of Laos#End of colonialism in Laos|Unified Kingdom]] |

|||

| established_event5 = [[French Indochina]] |

|||

| established_date6 = 11 May 1947 |

|||

| established_date5 = 1893–1949 |

|||

| |

| established_event7 = [[Kingdom of Laos|Independence]]<br>from [[French colonial empire|France]] |

||

| established_date7 = 22 October 1953 |

|||

| established_date6 = 19 July 1949 |

|||

| established_event8 = Monarchy abolished |

|||

| established_event7 = Declared Independence |

|||

| established_date8 = 2 December 1975 |

|||

| established_date7 = 22 Oct 1953 |

|||

| area_km2 = 236,800 |

|||

|area_rank = 84th |

|||

| area_rank = 82nd <!-- Area rank should match [[List of countries and dependencies by area]]--> |

|||

|area_magnitude = 1 E11 |

|||

| area_sq_mi = 91,428.991 <!--Do not remove per [[WP:MOSNUM]]--> |

|||

|area_km2 = 236,800 |

|||

| area_footnote = <ref name=CIA>{{Cite CIA World Factbook|country=Laos|access-date=24 September 2022}}</ref> |

|||

|area_sq_mi = 91,428.991 <!--Do not remove per [[WP:MOSNUM]]--> |

|||

|percent_water = 2 |

| percent_water = 2 |

||

| population_estimate = 7,953,556<ref name=CIA/> |

|||

|population_estimate = 6,803,699 <ref name="Background notes - Laos">{{cite web |url=http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/2770.htm |title=Background notes – Laos |publisher=US Department of State |accessdate=20 January 2012}}</ref> |

|||

|population_estimate_year = |

| population_estimate_year = 2024 |

||

|population_estimate_rank = |

| population_estimate_rank = 103rd |

||

| population_density_km2 = 26.7 |

|||

|population_census = 4,574,848 |

|||

| population_density_sq_mi = <!--Do not remove per [[WP:MOSNUM]]--> |

|||

|population_census_year = 1995 |

|||

| GDP_PPP = {{increase}} $74.760 billion<ref name="IMFWEO.LA">{{cite web |url=https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/October/weo-report?c=544,&s=NGDPD,PPPGDP,NGDPDPC,PPPPC,&sy=2023&ey=2025&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1 |title=World Economic Outlook Database, October 2024 Edition. (Laos) |publisher=[[International Monetary Fund]] |date=20 October 2024 |access-date=3 November 2024 }}</ref> |

|||

|population_density_km2 = 26.7 |

|||

| GDP_PPP_year = 2024 |

|||

|population_density_sq_mi = <!--Do not remove per [[WP:MOSNUM]]--> |

|||

| GDP_PPP_rank = 106th |

|||

|population_density_rank = 177th |

|||

| GDP_PPP_per_capita = {{increase}} $9,727<ref name="IMFWEO.LA" /> |

|||

|GDP_PPP_year = 2013 |

|||

| GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = 125th |

|||

|GDP_PPP = US$20.78 billion<ref name=imf2>{{cite web |url=http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2012/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?sy=2010&ey=2017&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=544&s=NGDPD%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPGDP%2CPPPPC&grp=0&a=&pr.x=40&pr.y=6 |title=Report for Selected Countries and Subjects |work= World Economic Outlook Database |publisher=[[International Monetary Fund]] |date= October 2012 |accessdate=22 January 2013}}</ref> <!--Do not edit!--> |

|||

| GDP_nominal = {{increase}} $14.949 billion<ref name="IMFWEO.LA" /> |

|||

|GDP_PPP_rank = |

|||

| GDP_nominal_year = 2024 |

|||

|GDP_PPP_per_capita = US$3,100<ref name=imf2/> <!--Do not edit!--> |

|||

| GDP_nominal_rank = 145th |

|||

|GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = |

|||

| GDP_nominal_per_capita = {{decrease}} $1,945<ref name="IMFWEO.LA" /> |

|||

|GDP_nominal_rank = |

|||

| GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = 152nd |

|||

|GDP_nominal = US$11.14 billion<ref name=imf2/> <!--Do not edit!--> |

|||

| Gini = 36.4 <!--number only--> |

|||

|GDP_nominal_year = 2013 |

|||

| Gini_year = 2012 |

|||

|GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = |

|||

| Gini_change = <!--increase/decrease/staedy--> |

|||

|GDP_nominal_per_capita = US$1,646<ref name=imf2/> <!--Do not edit!--> |

|||

| Gini_ref = <ref name="wb-gini">{{cite web|url=http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI/|title=Gini Index|publisher=World Bank|access-date=2 March 2011|archive-date=9 February 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150209003326/http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

|Gini_year = 2008 |

|||

| Gini_rank = |

|||

|Gini_change = <!--increase/decrease/staedy--> |

|||

| |

| HDI = 0.620<!--number only--> |

||

| HDI_year = 2022 <!--Please use the year in which the HDI data refers to and not the publication year--> |

|||

|Gini_ref = <ref name="wb-gini">{{cite web |url=http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI/ |title=Gini Index |publisher=World Bank |accessdate=2 March 2011}}</ref> |

|||

| HDI_change = increase <!--increase/decrease/steady--> |

|||

|Gini_rank = |

|||

| HDI_ref = <ref name="HDI">{{cite web|url=https://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2023-24_HDR/HDR23-24_Statistical_Annex_HDI_Table.xlsx|title=Human Development Report 2023/24|language=en|publisher=[[United Nations Development Programme]]|date=13 March 2024|access-date=22 March 2023|archive-date=19 March 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240319085123/https://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2023-24_HDR/HDR23-24_Statistical_Annex_HDI_Table.xlsx|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

|HDI_year = 2013 <!--Please use the year in which the HDI data refers to and not the publication year--> |

|||

| HDI_rank = 139th |

|||

|HDI_change = steady<!--increase/decrease/steady--> |

|||

| currency = [[Lao kip|Kip]] (₭) |

|||

|HDI = 0.569 <!--number only--> |

|||

| currency_code = LAK |

|||

|HDI_ref = <ref name="HDI">{{cite web |url=http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr14-summary-en.pdf |title=2014 Human Development Report Summary |date=2014 |accessdate=27 July 2014 |publisher=United Nations Development Programme | pages=21–25}}</ref> |

|||

| time_zone = [[Time in Laos|ICT]] |

|||

|HDI_rank = 139th |

|||

| utc_offset = +7 |

|||

|currency = [[Lao kip|Kip]] |

|||

| drives_on = right |

|||

|currency_code = LAK |

|||

| |

| calling_code = [[+856]] |

||

| cctld = [[.la]] |

|||

|utc_offset = |

|||

| religion = {{unbulleted list |

|||

|time_zone_DST = |utc_offset_DST = |

|||

| 66.0% [[Buddhism in Laos|Buddhism]]{{efn|"The State respects and protects all lawful activities of Buddhists and of followers of other religions, [and] mobilises and encourages Buddhist monks and novices as well as the priests of other religions to participate in activities that are beneficial to the country and people."<ref>{{cite web|title=Lao People's Democratic Republic's Constitution of 1991 with Amendments through 2003|url=https://constituteproject.org/constitution/Laos_2003.pdf?lang=en|website=constituteproject.org|access-date=29 October 2017|quote=Article 9: The State respects and protects all lawful activities of Buddhists and of followers of other religions, [and] mobilises and encourages Buddhist monks and novices as well as the priests of other religions to participate in activities that are beneficial to the country and people.|archive-date=10 December 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171210232122/https://constituteproject.org/constitution/Laos_2003.pdf?lang=en|url-status=live}}</ref>}} |

|||

|drives_on = right |

|||

| 30.7% [[Tai folk religion]] |

|||

|calling_code = [[+856]] |

|||

| 1.5% [[Christianity in Laos|Christianity]] |

|||

|iso3166code = LA |

|||

| 1.8% [[Religion in Laos|other]] / [[Irreligion|none]]<ref name="globalReligion" /> |

|||

|cctld = [[.la]] |

|||

}} |

|||

|footnote_a = Including [[List of ethnic groups in Laos|over 100 smaller ethnic groups]]. |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{contains Lao text|compact=yes}} |

|||

'''Laos''' (({{IPAc-en|audio=En-us-Laos.ogg|ˈ|l|aʊ|s}}, {{IPAc-en|ˈ|l|ɑː|.|ɒ|s}}, {{IPAc-en|ˈ|l|ɑː|.|oʊ|s}}, or {{IPAc-en|ˈ|l|eɪ|.|ɒ|s}})<ref>These same pronunciations using Wikipedia's pronunciation respelling key: {{respell|LOWSS|'}}, {{respell|LAH|oss}}, {{respell|LAH|ohss}}, {{respell|LAY|oss}}.</ref><ref name="oxford">{{cite web | url=http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/Laos#m_en_gb0457240 | title=Definition of Laos from Oxford Dictionaries Online | publisher=Oxford Dictionaries | accessdate=24 July 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/laos |title=Laos – Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary |publisher=Merriam-webster.com |accessdate=24 July 2011}}</ref> [[Lao Language]]: ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ, {{IPA-lo|sǎː.tʰáː.laʔ.naʔ.lat páʔ.sáː.tʰiʔ.páʔ.tàj páʔ.sáː.són.láːw|pron}} ''Sathalanalat Paxathipatai Paxaxon Lao''), officially the '''Lao People's Democratic Republic''' (LPDR) ({{lang-fr|République démocratique populaire lao}}), is a [[landlocked country]] in [[Southeast Asia]], bordered by [[Burma]] and the [[China|People's Republic of China]] to the northwest, [[Vietnam]] to the east, [[Cambodia]] to the south, and [[Thailand]] to the west. Since 1975, it is ruled by a [[Marxist]] and [[communist]] government. Its population was estimated to be around 6.5 million in 2012.<ref name="Background notes - Laos"/> |

|||

'''Laos''',{{efn|{{IPAc-en|audio=En-us-Laos.ogg|l|aʊ|s}}, {{IPAc-en|ˈ|l|ɑː|oʊ|s|,_|ˈ|l|ɑː|ɒ|s|,_|ˈ|l|eɪ|ɒ|s}} {{respell|LOWSS|,_|LAH|ohss|,_|LAH|oss|,_|LAY|oss}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Laos|title=Laos|via=The Free Dictionary|access-date=8 September 2016|archive-date=25 February 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210225194143/https://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Laos|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/english/Laos|title=Laos - definition of Laos in English from the Oxford dictionary|date=9 November 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151109212153/http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/english/Laos |archive-date=9 November 2015 }}</ref><ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20151130123751/http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/laos Oxford Dictionaries (American English)]</ref>}} officially the '''Lao People's Democratic Republic''' ('''LPDR'''),{{efn|{{langx|lo|ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ}} ({{lang|lo|ສປປ ລາວ}})}} is the only [[landlocked country]] in [[Southeast Asia]]. It is bordered by [[Myanmar]] and [[China]] to the northwest, [[Vietnam]] to the east, [[Cambodia]] to the southeast, and [[Thailand]] to the west and southwest.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.na.gov.la/appf17/geography.html|title=About Laos: Geography |website=Asia Pacific Parliamentary Forum|publisher=Government of Laos|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160416191557/http://www.na.gov.la/appf17/geography.html|archive-date=16 April 2016}}</ref> Its [[Capital city|capital]] and most populous city is [[Vientiane]]. |

|||

Significant corruption exists in the Lao government, military, and communist party in the LPDR, and the legacy of a [[command economy]], as well as excess spending on military and defense budgets during the [[Cold War]] and its aftermath, have continued to impoverish Laos. According to the anti-corruption non-governmental organization, Transparency International, the LPDR and Laos remain one of the most corrupt countries in the world which also deters foreign investment as well as creates major problems with the rule of law issues, including the ability to enforce contract and business law.<ref>Transparency International "Laos Corruption Perceptions Index" (2005-2014) http://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Laos/transparency_corruption/</ref> Consequently, a third of the population of Laos currently lives below the [[international poverty line]] (living on less than [[United States dollar|US$]]1.25 per day).<ref>{{cite web|title=Laos: Human Development Indicators|url=http://hdrstats.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/LAO.html|accessdate=19 July 2013|work=undp.org}}</ref> Laos has a low-income economy, with one of the lowest annual incomes in the world. In 2013, Laos ranked the [[List of countries by Human Development Index|138th]] place (tied with Cambodia) on the [[Human Development Index]] (HDI), indicating that Laos has lower medium to low development.<ref name="UNDP">{{cite web|url=http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2013/|title= The 2013 Human Development Report – "The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World"|publisher=[[Human Development Report|HDRO (Human Development Report Office)]] [[United Nations Development Programme]]|pages=144–147|accessdate=2 March 2013}}</ref> According to the [[Global Hunger Index]] (2013), Laos ranks as the 25th hungriest nation in the world out of the list of the 56 nations with the worst hunger situation(s).<ref>Welthungerhilfe, IFPRI, and Concern Worldwide: [http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/publications/ghi13.pdf 2013 Global Hunger Index - The challenge of hunger: Building Resilience to Achieve Food and Nutrition Security]. Bonn, Washington D. C., Dublin. October 2013.</ref> Laos has had a poor human rights record most particularly dealing with the nation's acts of genocide being committed towards its [[Hmong people|Hmong]] population. |

|||

Laos traces its |

Laos traces its historic and cultural identity to [[Lan Xang]], a kingdom which existed from the 13th century to the 18th century.<ref name="Stuart-Fox">{{Cite book|title=The Lao Kingdom of Lan Xang: Rise and Decline|last=Stuart-Fox|first=Martin|publisher=White Lotus Press|year=1998|isbn=974-8434-33-8|pages=49}}</ref> Because of its geographical location, the kingdom became a hub for overland trade.<ref name="Stuart-Fox"/> After a period of internal conflict, Lan Xang broke up into the [[Kingdom of Luang Phrabang]], the [[Kingdom of Vientiane]] and the [[Kingdom of Champasak]]. In 1893, the 3 kingdoms were united under a [[French colonial empire|French protectorate]]. Laos was [[History of Laos to 1945#Laos during World War II|occupied by Japan]] during [[World War II]] and regained independence in 1945 as a [[Kingdom of Luang Prabang (Japanese puppet state)|Japanese puppet state]] and was re-colonised by [[France]], until it won autonomy in 1949. |

||

Laos regained independence in 1953 as the [[Kingdom of Laos]], with a [[constitutional monarchy]] under [[Sisavang Vong]]. A [[Laotian Civil War|civil war]] began in 1959, which saw the communist [[Pathet Lao]], supported by [[North Vietnam]] and the [[Soviet Union]], fight against the [[Royal Lao Armed Forces]], supported by the [[United States]]. After the [[Vietnam War]] ended in 1975, the [[Lao People's Revolutionary Party]] established a one-party [[socialist republic]] espousing [[Marxism-Leninism]], ending the civil war and monarchy, and beginning a period of alignment with the Soviet Union until the [[dissolution of the Soviet Union]] in 1991. |

|||

Laos is a [[Single-party state|single-party]] [[socialist republic]]. It espouses [[Marxism]] and is governed by a single party communist [[politburo]] dominated by military generals. The [[Socialist Republic of Vietnam]] and the [[Vietnam People's Army]] continue to have significant influence in Laos. The capital city is [[Vientiane]]. Other large cities include [[Luang Prabang]], [[Savannakhet]], and [[Pakse]]. The official language is [[Lao language|Lao]]. Laos is a multi-ethnic country with the politically and culturally dominant [[Lao people]] making up approximately 60% of the population, mostly in the lowlands. [[Mon-Khmer languages|Mon-Khmer]] groups, the [[Hmong people|Hmong]], and other indigenous hill tribes, accounting for 40% of the population, live in the foothills and mountains. |

|||

Laos's strategies for development are based on [[Electricity generation|generating electricity]] from rivers and selling the power to its neighbours, namely Thailand, China and Vietnam, and its initiative to become a "land-linked" nation, as evidenced by the construction of 4 railways connecting Laos and neighbours.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://asiatimes.com/article/china-train-project-runs-roughshod-over-laos/|title=China train project runs roughshod over Laos|last=Janssen|first=Peter|work=Asia Times|access-date=19 January 2019|archive-date=13 October 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211013074841/https://asiatimes.com/2018/08/china-train-project-runs-roughshod-over-laos/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="bbcdam">{{cite news |title=Laos approves Xayaburi 'mega' dam on Mekong |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-20203072 |newspaper=BBC News |date=5 November 2012 |access-date=21 July 2018 |archive-date=1 July 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190701091431/https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-20203072 |url-status=live }}</ref> Laos has been referred to as one of Southeast Asia and Pacific's [[List of countries by real GDP growth rate|fastest growing economies]] by the [[World Bank]] with annual GDP growth averaging 7.4% since 2009,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/lao/overview|title=Lao PDR [Overview]|website=World Bank|date=March 2018|access-date=26 July 2018|archive-date=12 July 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180712034703/http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/lao/overview|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="autogenerated2">{{cite news |url = https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2011/01/10/454221/laos-securities-exchange-to-start-trading/?ft_site=falcon&desktop=true |title = Laos Securities Exchange to start trading |work = Financial Times |date = 10 January 2011 |access-date = 23 January 2011 |archive-date = 25 October 2020 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20201025201658/https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2011/01/10/454221/laos-securities-exchange-to-start-trading/?ft_site=falcon&desktop=true |url-status = live }}</ref> while being classified as a [[Least developed countries|least developed country]] by the [[United Nations]]. Laos is a member of the [[Asia-Pacific Trade Agreement]], the [[Association of Southeast Asian Nations|ASEAN]], [[East Asia Summit]], [[La Francophonie]], and the [[World Trade Organization]].<ref name="wto">{{cite web | url=http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/lao_e.htm | title=Lao People's Democratic Republic and the WTO | publisher=World Trade Organization | access-date=9 August 2014 | archive-date=12 August 2014 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140812135345/http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/lao_e.htm | url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

Laos' strategy for development is based on generating electricity from its rivers and selling the power to its neighbours, namely Thailand, China, and Vietnam.<ref name=bbc>{{cite news|title=Laos approves Xayaburi 'mega' dam on Mekong |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-20203072|newspaper=BBC News|date=5 November 2012}}</ref> Its economy is accelerating rapidly with the demands for its metals.<ref name="autogenerated2">{{cite web |url=http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/2d309312-1cb3-11e0-a106-00144feab49a.html#axzz1BP9Somjj |title=Laos Securities Exchange to start trading |publisher=Ft.com |date=10 January 2011 |accessdate=23 January 2011}}</ref> |

|||

==Etymology== |

|||

It is a member of the [[Asia-Pacific Trade Agreement]] (APTA), [[Association of Southeast Asian Nations]] (ASEAN), [[East Asia Summit]] and [[La Francophonie]]. Laos applied for membership of the [[World Trade Organization]] (WTO) in 1997; on 2 February 2013, it was granted full membership.<ref name="wto">{{cite web | url=http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/lao_e.htm | title=Lao People’s Democratic Republic and the WTO | publisher=World Trade Organization | accessdate=9 August 2014}}</ref> |

|||

The word ''Laos'' was coined by the [[French colonial empire|French]], who united the three Lao kingdoms in [[French Indochina]] in 1893. The name of the country is spelled the same as the plural of the most common ethnic group, the [[Lao people]].<ref name="tripsavvy" /> In English, the "s" in the name of the country is pronounced, and not silent.<ref name="tripsavvy">{{cite web |last1=Rodgers |first1=Greg |title=How to Say "Laos" |url=https://www.tripsavvy.com/how-to-say-laos-3976795 |website=TripSavvy |access-date=18 March 2020 |archive-date=3 March 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210303055220/https://www.tripsavvy.com/how-to-say-laos-3976795 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="fodors">{{cite web |last1=Ragusa |first1=Nina |title=10 Things You Need to Know Before Visiting Laos |url=https://www.fodors.com/world/asia/laos/experiences/news/10-things-you-need-to-know-before-visiting-laos |website=Fodors |access-date=18 March 2020 |date=4 April 2019 |archive-date=23 March 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210323062406/https://www.fodors.com/world/asia/laos/experiences/news/10-things-you-need-to-know-before-visiting-laos |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Meaning of Laos in English|url=https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/laos|website=Cambridge Dictionary|access-date=7 October 2019|archive-date=8 March 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210308104428/https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/laos|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Laos – definition and synonyms|url=https://www.macmillandictionary.com/dictionary/british/laos|website=Macmillan Dictionary|access-date=7 October 2019|archive-date=8 March 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210308155501/https://www.macmillandictionary.com/dictionary/british/laos|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Definition of Laos by Merriam-Webster |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Laos |website=Merriam-Webster |access-date=27 March 2020 |archive-date=8 March 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210308102619/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Laos |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

== History == |

|||

==Etymology==<!--linked--> |

|||

In the [[Lao language]], the country's name is "Muang Lao" (ເມືອງລາວ) or "Pathet Lao" (ປະເທດລາວ): both literally mean "Lao Country".<ref name="Kislenko2009">{{cite book|last=Kislenko|first=Arne|title=Culture and customs of Laos|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=D6CuONua48MC&pg=PR20|year=2009|publisher=ABC-CLIO|isbn=978-0-313-33977-6|page=20}}</ref> The French, who united the three Lao kingdoms in [[French Indochina]] in 1893, named the country as the plural of the dominant and most common ethnic group (in French, the final "s" at the end of a word is usually silent, thus it would be pronounced "Lao").<ref name="Hayashi2003">{{cite book|last=Hayashi|first=Yukio|title=Practical Buddhism among the Thai-Lao: religion in the making of a region|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=SZ73WQmu0iEC&pg=PA31|year=2003|publisher=Trans Pacific Press|isbn=978-4-87698-454-1|page=31}}</ref> |

|||

==History== |

|||

{{Main|History of Laos}} |

{{Main|History of Laos}} |

||

=== |

=== Prehistory === |

||

In 2009 an ancient human skull was recovered from the Tam Pa Ling cave in the Annamite Mountains in northern Laos; the skull is at least 46,000 years old, making it the oldest modern human fossil found to date in Southeast Asia.<ref>"[Demeter F. et al., Anatomically modern human in Southeast Asia (Laos) by 46 ka http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22908291/]", ''PNAS'', 4 September 2012.</ref> Archaeological evidence suggests agriculturist society developed during the 4th millennium BC. Burial jars and other kinds of sepulchers suggest a complex society in which bronze objects appeared around 1500 BC, and iron tools were known from 700 BC. The proto-historic period is characterised by contact with Chinese and Indian civilisations. From the fourth to the eighth century, communities along the [[Mekong River]] began to form into townships called ''muang''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tourismlaos.org/web/show_content.php?contID=6 |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20110304223831/http://www.tourismlaos.org/web/show_content.php?contID=6 |archivedate=4 March 2011|title=Facts on Laos |publisher=Laos National Tourism Association|accessdate=24 December 2011}}</ref> |

|||

===Lan Xang=== |

|||

{{Main|Lan Xang|}} |

|||

[[File:Pha That Luang, Vientiane, Laos.jpg|thumb|left|[[Pha That Luang]] in [[Vientiane]] is the national symbol of Laos.]] |

[[File:Pha That Luang, Vientiane, Laos.jpg|thumb|left|[[Pha That Luang]] in [[Vientiane]] is the national symbol of Laos.]] |

||

A human skull was recovered in 2009 from the [[Tam Pa Ling Cave]] in the [[Annamite Range|Annamite Mountains]] in northern Laos; the skull is at least 46,000 years old, making it the oldest modern human fossil found to date in Southeast Asia.<ref>{{Cite journal|pmid = 22908291|pmc = 3437904|year = 2012|last1 = Demeter|first1 = F|display-authors=et al.|title = Anatomically modern human in Southeast Asia (Laos) by 46 ka|journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume = 109|issue = 36|pages = 14375–14380|doi = 10.1073/pnas.1208104109|bibcode = 2012PNAS..10914375D|doi-access = free|issn = 0027-8424 }}</ref> Stone artifacts including [[Hoabinhian]] types have been found at sites dating to the [[Pleistocene]] in northern Laos.<ref>{{Cite journal|year = 2009|last1 = White|first1 = J.C.|title = Archaeological Investigations in northern Laos: New contributions to Southeast Asian prehistory|journal = Antiquity|volume = 83|issue = 319|last2 = Lewis|first2 = H.|last3 = Bouasisengpaseuth|first3 = B.|last4 = Marwick|first4 = B.|last5 = Arrell|first5 = K|url = http://antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/white/|access-date = 18 September 2016|archive-date = 10 October 2017|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20171010191403/http://antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/white/|url-status = live}}</ref> Archaeological evidence suggests an agriculturist society developed during the 4th millennium BC.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Marwick|first1=Ben|last2=Bouasisengpaseuth|first2=Bounheung|chapter=History and Practice of Archaeology in Laos|editor1-last=Habu|editor1-first=Junko|editor2-last=Lape|editor2-first=Peter|editor3-last=Olsen|editor3-first=John|title=Handbook of East and Southeast Asian Archaeology|publisher=Springer|date=2017|chapter-url=https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/75zhc/|access-date=20 January 2018|archive-date=6 July 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190706125232/https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/75zhc/|url-status=live}}</ref> Burial jars and other kinds of sepulchers suggest a society in which bronze objects appeared around 1500 BC, and iron tools were known from 700 BC. The proto-historic period is characterised by contact with Chinese and Indian civilisations. According to linguistic and other historical evidence, [[Tai languages|Tai-speaking]] tribes migrated southwestward to the territories of Laos and Thailand from [[Guangxi]] sometime between the 8th and 10th centuries.<ref name="PittayawatPittayaporn">[http://www.manusya.journals.chula.ac.th/files/essay/Pittayawat%2047-68.pdf Pittayaporn, Pittayawat (2014). Layers of Chinese Loanwords in Proto-Southwestern Tai as Evidence for the Dating of the Spread of Southwestern Tai] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150627063518/http://www.manusya.journals.chula.ac.th/files/essay/Pittayawat%2047-68.pdf |date=27 June 2015 }}. ''MANUSYA: Journal of Humanities'', Special Issue No 20: 47–64.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Fa Ngum-Vtne1.JPG|thumb|right|Statue of [[Fa Ngum]], founder of the [[Lan Xang]] kingdom]] |

|||

=== Lan Xang === |

|||

Laos traces its history to the kingdom of Lan Xang (Million Elephants), founded in the 14th century, by a Lao prince [[Fa Ngum]], who with 10,000 [[Khmer people|Khmer]] troops, took over [[Vientiane]]. Ngum was descended from a long line of Lao kings, tracing back to Khoun Boulom. He made [[Theravada Buddhism]] the state religion and Lan Xang prospered. Within 20 years of its formation, the kingdom expanded eastward to Champa and along the Annamite mountains in Vietnam. His ministers, unable to tolerate his ruthlessness, forced him into exile to the present-day Thai province of [[Nan Province|Nan]] in 1373,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.history.com/topics/fa-ngum |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20100308201136/http://www.history.com/topics/fa-ngum |archivedate=8 March 2010 |title=Fa Ngum|publisher=History.com |accessdate=23 January 2011}}</ref> where he died. Fa Ngum's eldest son, Oun Heuan, came to the throne under the name [[Samsenthai]] and reigned for 43 years. During his reign, Lan Xang became an important trade centre. After his death in 1421, Lan Xang collapsed into warring factions for the next 100 years. |

|||

{{Main|Lan Xang}} |

|||

Laos traces its history to the kingdom of Lan Xang ('million elephants'), which was founded in the 13th century by a Lao prince, [[Fa Ngum]],<ref name="Coedes">{{cite book|last= Coedès|first= George|author-link= George Coedès|editor= Walter F. Vella|others= trans. Susan Brown Cowing|title= The Indianized States of Southeast Asia|year= 1968 |publisher= University of Hawaii Press |isbn = 978-0-8248-0368-1}}</ref>{{rp|223}} whose father had his family exiled from the [[Khmer Empire]]. Fa Ngum, with 10,000 [[Khmer people|Khmer]] troops, conquered some Lao principalities in the [[Mekong]] river basin, culminating in the capture of [[Vientiane]]. Ngum was descended from a line of Lao kings that traced back to Khoun Boulom.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Fa-Ngum|title=Fa Ngum|website=Encyclopædia Britannica|access-date=23 December 2019|archive-date=8 March 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210308050252/https://www.britannica.com/biography/Fa-Ngum|url-status=live}}</ref> He made [[Theravada|Theravada Buddhism]] the state religion. His ministers, unable to tolerate his ruthlessness, forced him into exile to what is later the Thai province of [[Nan Province|Nan]] in 1373,<ref>{{cite web |url = http://www.history.com/topics/fa-ngum |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100308201136/http://www.history.com/topics/fa-ngum |archive-date = 8 March 2010 |title = Fa Ngum |publisher=History.com |access-date = 23 January 2011}}</ref> where he died. Fa Ngum's eldest son, Oun Heuan, ascended to the throne under the name [[Samsenethai]] and reigned for 43 years. Lan Xang became a trade centre during Samsenthai's reign, and after his death in 1421 it collapsed into warring factions for nearly a century.<ref>Sanda Simms, ch. 3, "Through Chaos to a New Order", in ''The Kingdoms of Laos'' (London: Taylor & Francis, 2013). {{ISBN|9781136863370}}</ref> |

|||

In 1520, [[Photisarath]] came to the throne and moved the capital from [[Luang Prabang]] to Vientiane to avoid a |

In 1520, [[Photisarath]] came to the throne and moved the capital from [[Luang Prabang]] to Vientiane to avoid a Burmese invasion. [[Setthathirath]] became king in 1548, after his father was killed, and ordered the construction of [[Pha That Luang|That Luang]]. Settathirath disappeared in the mountains on his way back from a military expedition into [[Cambodia]], and Lan Xang fell into more than 70 years of "instability", involving Burmese invasion and civil war.<ref>Sanda Simms, ch. 6, "Seventy Years of Anarchy", in ''The Kingdoms of Laos'' (London: Taylor & Francis, 2013). {{ISBN|9781136863370}}; see also P.C. Sinha, ed., ''Encyclopaedia of South East and Far East Asia'', vol. 3 (Anmol, 2006).</ref> |

||

In 1637, when [[Sourigna Vongsa]] ascended the throne, Lan Xang further expanded its frontiers. When he died without an heir, the kingdom split into three principalities. Between 1763 and 1769, Burmese armies overran northern Laos and annexed [[Luang Prabang]], while [[Kingdom of Champasak|Champasak]] eventually came under Siamese [[suzerainty]].<ref>{{Cite book|last=Askew, Marc.|title=Vientiane : transformations of a Lao landscape|year=2010|orig-year= 2007|publisher=Routledge|others=Logan, William Stewart, 1942–, Long, Colin, 1966–|isbn=978-0-415-59662-6|location=London|oclc=68416667}}</ref> |

|||

[[Anouvong|Chao Anouvong]] was installed as a vassal king of Vientiane by the Siamese. He encouraged a renaissance of Lao fine arts and literature and improved relations with Luang Phrabang. Under Vietnamese pressure, he rebelled against the Siamese. The rebellion failed and Vientiane was ransacked.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.asianewsnet.net/home/news.php?sec=3&id=15718 |title=Let's hope Laos hangs on to its identity |publisher=Asianewsnet.net |accessdate=23 January 2011}}</ref> Anouvong was taken to [[Bangkok]] as a prisoner, where he died. |

|||

[[Anouvong|Chao Anouvong]] was installed as a vassal king of Vientiane by the Siamese. He encouraged a renaissance of Lao fine arts and literature and improved relations with Luang Phrabang. Under Vietnamese pressure, [[Lao rebellion (1826–1828)|he rebelled against the Siamese in 1826]]. The rebellion failed, and Vientiane was ransacked.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.asianewsnet.net/home/news.php?sec=3&id=15718 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101126004328/http://www.asianewsnet.net/home/news.php?id=15718&sec=3 |url-status=usurped |archive-date=26 November 2010 |title=Let's hope Laos hangs on to its identity |publisher=Asianewsnet.net |access-date=23 January 2011 }}</ref> Anouvong was taken to [[Bangkok]] as a prisoner, where he died.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Imperial Wars 1815–1914 | series = Encyclopedia of Warfare Series |editor-last=Showalter | editor-first = Dennis | editor-link = Dennis Showalter |date= 2013|isbn=978-1-78274-125-1|publisher = Amber Books | location=London|oclc=1152285624}}</ref> |

|||

A Siamese military campaign in Laos in 1876 was described by a British observer as having been "transformed into [[History of slavery in Asia|slave-hunting raids]] on a large scale".<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20101012011239/http://kyotoreviewsea.org/slavery3.htm "Slavery in Nineteenth-Century Northern Thailand: Archival Anecdotes and Village Voices"]. ''The Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia''</ref> |

|||

In a time period where the acquisition of humans was a priority over the ownership of land, the warfare of pre-modern Southeast Asia revolved around the seizing of people and resources from its enemies. A Siamese military campaign in Laos in 1876 was described by a British observer as having been "transformed into [[Slavery in Asia|slave-hunting raids]] on a large scale".<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20101012011239/http://kyotoreviewsea.org/slavery3.htm "Slavery in Nineteenth-Century Northern Thailand: Archival Anecdotes and Village Voices"]. ''The Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia''</ref> |

|||

===French Laos=== |

|||

{{Infobox Former Country |

|||

|native_name = Protectorat français du Laos |

|||

|conventional_long_name = French Laos |

|||

|common_name = Laos |

|||

|continent = moved from Category:Asia to Southeast Asia |

|||

|region = Southeast Asia |

|||

|era = New Imperialism |

|||

|status = [[Monarchy]], [[Protectorate]] of [[France]], constituent of [[French Indochina]] |

|||

|empire = France |

|||

|government_type = |

|||

|event_start = Protectorate established |

|||

|date_start = |

|||

|year_start = 1893 |

|||

|event_end = Independence |

|||

|date_end = 9 November |

|||

|year_end = 1953 |

|||

|event1 = [[Kingdom of Laos]] proclaimed |

|||

|date_event1 = 11 May 1947 |

|||

|event_post = [[Geneva Conference (1954)|Geneva Conference]] |

|||

|date_post = 21 July 1954 |

|||

|year_post = |

|||

|p1 = Kingdom of Luang Phrabang |

|||

|p2 = Champasak Kingdom |

|||

|p3 = Rattanakosin Kingdom |

|||

|flag_p1 = Flag of Luang Phrabang Kingdom (1893 - 1949).png |

|||

|flag_p3 = Flag of Thailand 1855.svg |

|||

|s1 = Kingdom of Laos |

|||

|flag_s1 = Flag of Laos (1952-1975).svg |

|||

|image_flag = Flag of French Laos.svg |

|||

|image_coat = Royal Coat of Arms of Laos.svg |

|||

|symbol_type = Royal Arms |

|||

|image_map = LocationLaos.png |

|||

|capital = [[Vientiane]] (official), [[Luang Prabang]] (ceremonial) |

|||

|common_languages = [[French language|French]] (official), [[Lao language|Lao]] |

|||

|religion = [[Theravada Buddhism]], [[Roman Catholicism]] |

|||

|anthem = [[La Marsellaise]] |

|||

|leader1 = [[Oun Kham]] (first) |

|||

|title_leader = [[List of monarchs of Laos|King]] |

|||

|year_leader1 = 1868-1895 |

|||

|leader2 = [[Sisavang Vong]] (last) |

|||

|year_leader2 = 1904-1954 |

|||

|representative1 = |

|||

|title_representative = |

|||

|year_representative1 = |

|||

|deputy1 = |

|||

|title_deputy = |

|||

|year_deputy1 = }} |

|||

{{main|History of Laos to 1945}} |

|||

In the late 19th century, Luang Prabang was ransacked by the Chinese [[Black Flag Army]].<ref>{{cite web|author=Librios Semantic Environment |url=http://www.culturalprofiles.net/laos/Directories/Laos_Cultural_Profile/-1064.html |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20070718125054/http://www.culturalprofiles.net/laos/Directories/Laos_Cultural_Profile/-1064.html |archivedate=18 July 2007 |title=Laos: Laos under the French |publisher=Culturalprofiles.net |date=11 August 2006 |accessdate=23 January 2011}}</ref> France rescued King [[Oun Kham]] and added Luang Phrabang to the 'Protectorate' of [[French Indochina]]. Shortly after, the [[Kingdom of Champasak]] and the territory of [[Vientiane]] were added to the protectorate. King [[Sisavang Vong]] of Luang Phrabang became ruler of a unified Laos and Vientiane once again became the capital. Laos never had any importance for France<ref>{{cite book|author=Cummings, Joe and Burke|title=Laos|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=A61wRiwTbPgC&pg=PA23|year=2005|publisher=Lonely Planet, Andrew |isbn=978-1-74104-086-9|pages=23–}}</ref> other than as a buffer state between British-influenced Thailand and the more economically important [[Annam (French protectorate)|Annam]] and [[Tonkin]]. |

|||

During their rule, the French introduced the [[corvee]], a system that forced every male Lao to contribute 10 days of manual labour per year to the colonial government. Laos produced [[tin]], [[rubber]], and coffee, but never accounted for more than 1% of French Indochina's exports. By 1940, around 600 French citizens lived in Laos.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.lonelyplanet.com/laos/history |title=History of Laos|publisher=Lonelyplanet.com |date=9 August 1960 |accessdate=23 January 2011}}</ref> Most of the French who came to Laos as officials, settlers or missionaries developed a strong affection for the country and its people, and many devoted decades to what they saw as bettering the lives of the Lao. Some took Lao wives, learned the language, became Buddhists and "went native" - something more acceptable in the French Empire than in the British. With the racial attitudes typical of Europeans at this time, however, they tended to classify the Lao as gentle, amiable, childlike, naive and lazy, regarding them with what one writer called "a mixture of affection and exasperation." |

|||

=== French Laos (1893–1953) === |

|||

Prince [[Phetsarath]] declared Laos' independence on 12 October 1945, but the French under [[Charles de Gaulle]] re-asserted control. In 1950 Laos was granted semi-autonomy as an "associated state" within the [[French Union]]. France remained in de facto control until 22 October 1953, when Laos gained full independence as a [[constitutional monarchy]]. |

|||

{{Main|French protectorate of Laos|First Indochina War}} |

|||

[[File:Local Lao in the French Colonial guard.png|thumb|Local Lao soldiers in the French Colonial guard, {{circa| 1900}}]] |

|||

In the 19th century, Luang Prabang was ransacked by the Chinese [[Black Flag Army]].<ref>{{cite web |author=Librios Semantic Environment |url = http://www.culturalprofiles.net/laos/Directories/Laos_Cultural_Profile/-1064.html |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070718125054/http://www.culturalprofiles.net/laos/Directories/Laos_Cultural_Profile/-1064.html |archive-date = 18 July 2007 |title = Laos: Laos under the French |publisher = Culturalprofiles.net |date=11 August 2006 |access-date = 23 January 2011}}</ref> France rescued King [[Oun Kham]] and added Luang Phrabang to the protectorate of [[French Indochina]]. The [[Kingdom of Champasak]] and the territory of Vientiane were added to the protectorate. King [[Sisavangvong]] of Luang Phrabang became ruler of a unified Laos, and Vientiane once again became the capital.<ref>Carine Hahn, ''Le Laos'', Karthala, 1999, pp. 69–72</ref> |

|||

===Independence & Communist Rule=== |

|||

[[File:Sisavang Vong.jpg|thumb|King [[Sisavang Vong]] of Laos]] |

|||

{{Main|Kingdom of Laos|Laotian Civil War}} |

|||

[[File:Vientianne1973.jpg|thumb|left|[[Pathet Lao]] soldiers in [[Vientiane]], 1972]] |

|||

In 1955, the [[US Department of Defense]] created a special [[Programs Evaluation Office]] to replace French support of the [[Royal Lao Army]] against the [[communist]] [[Pathet Lao]] as part of the US [[containment]] policy. |

|||

Laos produced [[tin]], rubber, and coffee, and never accounted for more than 1% of French Indochina's exports. By 1940, around 600 French citizens lived in Laos.<ref>{{cite web |url = http://www.lonelyplanet.com/laos/history |title = History of Laos |website = Lonely Planet |date = 9 August 1960 |access-date = 23 January 2011 |archive-date = 25 February 2021 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210225100345/https://www.lonelyplanet.com/laos/history |url-status = dead }}</ref> Under French rule, the Vietnamese were encouraged to migrate to Laos, which was seen by the French colonists as a rational solution to a labour shortage within the confines of an Indochina-wide colonial space.<ref name="SørenIvarsson">Ivarsson, Søren (2008). ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=FsXjlJF_fokC&pg=PA102 Creating Laos: The Making of a Lao Space Between Indochina and Siam, 1860–1945] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230410140148/https://books.google.com/books?id=FsXjlJF_fokC&pg=PA102 |date=10 April 2023 }}''. NIAS Press, p. 102. {{ISBN|978-8-776-94023-2}}.</ref> By 1943, the Vietnamese population stood at nearly 40,000, forming the majority in some cities of Laos and having the right to elect its own leaders.<ref name="MartinStuart-FoxA">Stuart-Fox, Martin (1997). ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=8VvvevRkX-EC&dq=A+History+of+Laos&pg=PA51 A History of Laos] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230405045254/https://books.google.com/books?id=8VvvevRkX-EC&dq=A+History+of+Laos&pg=PA51 |date=5 April 2023 }}''. Cambridge University Press, p. 51. {{ISBN|978-0-521-59746-3}}.</ref> As a result, 53% of the population of Vientiane, 85% of [[Thakhek]], and 62% of [[Pakse]] were Vietnamese, with the exception of [[Luang Prabang]] where the population was predominantly Lao.<ref name="MartinStuart-FoxA"/> As late as 1945, the French drew up a plan to move a number of Vietnamese to three areas, i.e., the Vientiane Plain, [[Savannakhet Province|Savannakhet region]], and the [[Bolaven Plateau]], which was derailed by the Japanese invasion of Indochina.<ref name="MartinStuart-FoxA"/> Otherwise, according to [[Martin Stuart-Fox]], the Lao might well have lost control over their own country.<ref name="MartinStuart-FoxA"/> |

|||

In 1960, amidst a series of rebellions in the [[Kingdom of Laos]], fighting broke out between the Royal Lao Army and the communist [[North Vietnam]]-backed, and [[Soviet Union]]-backed Pathet Lao guerillas. A second Provisional Government of National Unity formed by Prince [[Souvanna Phouma]] in 1962 proved to be unsuccessful, and the situation steadily deteriorated into large scale [[Laotian Civil War|civil war]] between the Royal Laotian government and the Pathet Lao. The Pathet Lao were backed militarily by the [[North Vietnamese Army|NVA]] and [[Vietcong]]. |

|||

During [[French Protectorate of Laos#Laos during World War II|World War II in Laos]], [[Vichy France]], [[Thailand]], [[Empire of Japan|Imperial Japan]] and [[Free France]] occupied Laos.<ref>Paul Lévy, ''Histoire du Laos'', PUF, 1974.</ref> On 9 March 1945, a nationalist group declared Laos once more independent, with [[Luang Prabang]] as its capital; on 7 April 1945, two battalions of Japanese troops occupied the city.<ref name="A Country Study: Laos">Savada, Andrea Matles (editor) (1994). "Events in 1945". [http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/latoc.html ''A Country Study: Laos''] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150721090309/http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/latoc.html |date=21 July 2015 }}. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress.</ref> The Japanese attempted to force [[Sisavang Vong]] (the king of Luang Phrabang) to declare Laotian independence, and on 8 April he instead declared an end to Laos's status as a French protectorate. The king then secretly sent Prince [[Kindavong]] to represent Laos to the [[Allies of World War II|Allied forces]] and [[Sisavang Vatthana|Prince Sisavang]] as representative to the Japanese.<ref name="A Country Study: Laos"/> When Japan surrendered, some Lao nationalists (including Prince [[Phetsarath Ratanavongsa|Phetsarath]]) declared Laotian independence, and by 1946, French troops had reoccupied the country and conferred autonomy on Laos.<ref name="britannica" /> |

|||

The [[North Vietnamese invasion of Laos]], by the [[Moscow]]-backed [[Vietnam People's Army]], and post-Vietnam War occupation of Laos, continued in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. |

|||

During the [[First Indochina War]], the [[Indochinese Communist Party]] formed the [[Pathet Lao]] independence organisation. The Pathet Lao began a war against the French colonial forces with the aid of the Vietnamese independence organisation, the [[Viet Minh]]. In 1950, the French were forced to give Laos semi-autonomy as an "associated state" within the [[French Union]]. France remained in de facto control until 22 October 1953, when Laos gained full independence as a [[constitutional monarchy]].<ref name="bbc" /><ref name="britannica">{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/330219/Laos/52500/People?anchor=ref509292 |title=Laos – Overview |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |access-date=23 January 2011 |archive-date=11 May 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110511175031/http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/330219/Laos/52500/People?anchor=ref509292 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

Laos was a key part of the [[Vietnam War]] since parts of Laos were invaded and occupied by North Vietnam for use as a supply route for its war against the [[Republic of Vietnam|South]]. In response, the United States initiated a bombing campaign against the North Vietnamese positions, supported regular and irregular anticommunist forces in Laos and supported [[ARVN|South Vietnamese]] incursions into Laos. |

|||

=== Independence and communist rule (1953–) === |

|||

In 1968 the North Vietnamese Army launched a multi-division attack to help the Pathet Lao to fight the Royal Lao Army. The attack resulted in the army largely demobilising, leaving the conflict to irregular ethnic Lao Hmong [[Hmong people]] forces of the "U.S. Secret Army" backed by the United States and Thailand, and led by General [[Vang Pao]]. |

|||

{{Main|History of Laos since 1945|3 = Laotian Civil War}} |

|||

[[File:FrenchLaos1953.png|thumb|French general [[Raoul Salan]] and [[Sisavang Vatthana|Prince Sisavang Vatthana]] in Luang Prabang, 4 May 1953]] |

|||

The First Indochina War took place across French Indochina and eventually led to French defeat and the signing of a peace accord for Laos at the [[1954 Geneva Conference|Geneva Conference of 1954]]. In 1960, amidst a series of rebellions in the [[Kingdom of Laos]], fighting broke out between the [[Royal Lao Army]] (RLA) and the communist [[North Vietnam]]ese and [[Soviet Union]]-backed Pathet Lao guerillas. A second Provisional Government of National Unity formed by Prince [[Souvanna Phouma]] in 1962 was unsuccessful, and the situation turned into [[Laotian Civil War|civil war]] between the Royal Laotian government and the Pathet Lao. The Pathet Lao were backed militarily by the [[People's Army of Vietnam]] (PAVN) and the [[Viet Cong]].<ref name="bbc" /><ref name="britannica" /> |

|||

[[File:Muang Khoun - Laos - 01.JPG|thumb|right|Ruins of [[Khoune district|Muang Khoun]], former capital of [[Xiangkhouang Province|Xiangkhouang province]], destroyed by the [[CIA activities in Laos|American bombing of Laos]] in the 1960s]] |

|||

Massive aerial bombardment against Pathet Lao and invading NVA [[communist]] forces was carried out by the United States to prevent the collapse of Laos' central government, the Royal [[Kingdom of Laos]], and to prevent the use of the [[Ho Chi Minh Trail]] to attack US forces in South Vietnam and the [[Republic of Vietnam]]. "...Laos, the most heavily bombed country on earth...was hit by an average of one B-52 bomb-load every eight minutes, 24 hours a day, between 1964 and 1973. US bombers dropped more ordnance on Laos in this period than was dropped during the whole of the second world war."<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/dec/03/laos-cluster-bombs-uxo-deaths | work=The Guardian | location=London | title=Forty years on, Laos reaps bitter harvest of the secret war | first=Ian | last=MacKinnon | date=3 Dec 2008 | accessdate=7 May 2010}}</ref> Due to the particularly heavily impact of [[cluster bombs]] during this war, Laos was a strong advocate of the [[Convention on Cluster Munitions]] to ban the weapons and assist victims, and hosted the First Meeting of States Parties to the convention in November 2010.<ref>{{cite web|title=Disarmament|url=http://www.unog.ch/80256EE600585943/(httpPages)/B3F3E37A2838630FC125772E0050F4F7?OpenDocument|work=The United Nations Office at Geneva|publisher=United Nations|accessdate=20 September 2013|date=November 2011}}</ref> |

|||

Laos was a part of the [[Vietnam War]] since parts of Laos were [[North Vietnamese invasion of Laos|invaded and occupied]] by [[North Vietnam]] since 1958 for use as a supply route for its war against [[South Vietnam]]. In response, the United States initiated a bombing campaign against the PAVN positions, supported regular and irregular anti-communist forces in Laos, and supported [[CIA activities in Laos|incursions into Laos]] by the [[Army of the Republic of Vietnam]].<ref name=bbc /><ref name=britannica /> |

|||

Aerial bombardments against the PAVN/[[Pathet Lao]] forces were carried out by the [[United States]] to prevent the collapse of the [[Kingdom of Laos]] central government, and to deny the use of the [[Ho Chi Minh trail|Ho Chi Minh Trail]] to attack US forces in [[South Vietnam]].<ref name=bbc /> Between 1964 and 1973, the US dropped 2 million tons of bombs on Laos, nearly equal to the 2.1 million tons of bombs the US dropped on Europe and Asia during all of World War II, making Laos the most heavily bombed country in history relative to the size of its population; ''[[The New York Times]]'' notes this was "nearly a ton for every person in Laos".<ref>{{cite web|author-link1=Ben Kiernan|last1=Kiernan|first1=Ben|last2=Owen|first2=Taylor|url=http://apjjf.org/2015/13/16/Ben-Kiernan/4313.html|title=Making More Enemies than We Kill? Calculating U.S. Bomb Tonnages Dropped on Laos and Cambodia, and Weighing Their Implications|work=The Asia-Pacific Journal|date=26 April 2015|access-date=18 September 2016|archive-date=1 March 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170301041322/http://apjjf.org/2015/13/16/Ben-Kiernan/4313.html|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

In 1975 the [[Pathet Lao]], along with the [[Vietnam People's Army]] and backed by the [[Soviet Union]], overthrew the [[Kingdom of Laos|royalist Lao government]], forcing King [[Savang Vatthana]] to abdicate on 2 December 1975. He later died in captivity. Between 20,000 and 70,000 Laotians died during the Civil War.<ref>T. Lomperis, From People's War to People's Rule, (1996), estimates 35,000 total.</ref><ref>Eckhardt, William, in World Military and Social Expenditures 1987-88 (12th ed., 1987) by Ruth Leger Sivard.</ref><ref>Rummel, Rudolph J.: Death By Government (1994)</ref><ref>Obermeyer (2008), "Fifty years of violent war deaths from Vietnam to Bosnia", ''British Medical Journal''.</ref> |

|||

Some 80 million bombs failed to explode and remain scattered throughout the country. [[Unexploded ordnance]] (UXO), including [[cluster munitions]] and mines, kill or maim approximately 50 Laotians every year.<ref>{{cite web|last=Wright|first=Rebecca|url=http://www.cnn.com/2016/09/05/asia/united-states-laos-secret-war/|title='My friends were afraid of me': What 80 million unexploded US bombs did to Laos|work=[[CNN]]|date=6 September 2016|access-date=18 September 2016|archive-date=17 January 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190117203916/https://www.cnn.com/2016/09/05/asia/united-states-laos-secret-war/|url-status=live}}</ref> Due to the impact of cluster bombs during this war, Laos was an advocate of the [[Convention on Cluster Munitions]] to ban the weapons and was host to the First Meeting of States Parties to the convention in November 2010.<ref>{{cite web|title=Disarmament|url=http://www.unog.ch/80256EE600585943/(httpPages)/B3F3E37A2838630FC125772E0050F4F7?OpenDocument|work=The United Nations Office at Geneva|publisher=United Nations|access-date=20 September 2013|date=November 2011|archive-date=21 September 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130921060643/http://www.unog.ch/80256EE600585943/(httpPages)/B3F3E37A2838630FC125772E0050F4F7?OpenDocument|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

On 2 December 1975, after taking control of the country, the Pathet Lao government under [[Kaysone Phomvihane]] renamed the country as the ''Lao People's Democratic Republic'' and signed agreements giving Vietnam the right to station armed forces and to appoint advisers to assist in overseeing the country. Laos was requested in 1979 by the [[Socialist Republic of Vietnam]] to end relations with the [[People's Republic of China]], leading to isolation in trade by China, the United States, and other countries. |

|||

[[File:Vientianne1973.jpg|thumb|[[Pathet Lao]] soldiers in [[Vientiane]], 1973]] |

|||

In 1975, the [[Pathet Lao]] overthrew the royalist government, forcing King [[Sisavang Vatthana|Savang Vatthana]] to abdicate on 2 December 1975. He later died in a [[Re-education camp (Vietnam)|re-education camp]]. Between 20,000 and 62,000 Laotians died during the civil war.<ref name=bbc /><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Obermeyer|first1=Ziad|last2=Murray|first2=Christopher J. L.|last3=Gakidou|first3=Emmanuela|year=2008|title=Fifty years of violent war deaths from Vietnam to Bosnia: analysis of data from the world health survey programme|journal=[[BMJ]]|volume=336|issue=7659|pages=1482–1486|doi=10.1136/bmj.a137|pmid=18566045|pmc=2440905}} See Table 3.</ref> |

|||

On 2 December 1975, after taking control of the country, the Pathet Lao government under [[Kaysone Phomvihane]] renamed the country as the ''Lao People's Democratic Republic'' and signed agreements giving Vietnam the right to station armed forces and to appoint advisers to assist in overseeing the country. The ties between Laos and [[Vietnam]] were formalised via a treaty signed in 1977, which has since provided direction for Lao foreign policy, and provides the basis for Vietnamese involvement at levels of Lao political and economic life.<ref name=bbc /><ref name="Martin Stuart-Fox">Stuart-Fox, Martin (1980). ''[https://www.jstor.org/stable/27908403?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents LAOS: The Vietnamese Connection] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211013074847/https://www.jstor.org/stable/27908403?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents |date=13 October 2021 }}''. In Suryadinata, L (Ed.), ''Southeast Asian Affairs'' (1980). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Stuides, pg. 191.</ref> Laos was requested in 1979 by [[Vietnam]] to end relations with the [[China|People's Republic of China]], leading to isolation in trade by [[China]], the [[United States]], and other countries.<ref name="DamienKingsbury">Kingsbury, Damien (2016). ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=8CQlDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA50 Politics in Contemporary Southeast Asia: Authority, Democracy and Political Change] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230410140218/https://books.google.com/books?id=8CQlDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA50 |date=10 April 2023 }}''. Taylor & Francis;{{ISBN|978-1-317-49628-1}}, pg. 50.</ref> In 1979, there were 50,000 PAVN troops stationed in Laos and as many as 6,000 civilian Vietnamese officials including 1,000 directly attached to the ministries in [[Vientiane]].<ref name="Savada">Savada, Andrea M. (1995). ''[http://www.public-library.uk/dailyebook/Laos%20-%20a%20country%20study.pdf Laos: a country study] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180419183125/http://www.public-library.uk/dailyebook/Laos%20-%20a%20country%20study.pdf |date=19 April 2018 }}''. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, p. 271. {{ISBN|0-8444-0832-8}}</ref><ref name="Prayaga">Prayaga, M. (2005). ''[http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/103010/8/08_chapter-iv.pdf Renovation in Vietnam since 1988 a study in political, economic and social change] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180419122734/http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/103010/8/08_chapter-iv.pdf |date=19 April 2018 }} (PhD thesis)''. Sri Venkateswara University. Chapter IV: The Metamorphosed Foreign Relations, pg. 154.</ref> |

|||

The conflict between [[Hmong people|Hmong]] rebels and the [[Vietnam People's Army]] of the [[Socialist Republic of Vietnam]] (SRV), as well as the SRV-backed Pathet Lao [[Insurgency in Laos|continued]] in in key areas of Laos, including in Saysaboune Closed Military Zone, Xaisamboune Closed Military Zone near Vientiane Province and Xieng Khouang Province. The government of Laos has been accused of committing [[genocide]], [[human rights]] and [[religious freedom]] violations against the Hmong in collaboration with the [[Vietnam People's Army|Vietnamese army]],<ref name=BW/><ref name="Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization">{{cite web| url=http://www.unpo.org/article/5095| author=Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization| accessdate=20 April 2011|title=WGIP: Side event on the Hmong Lao, at the United Nations}}</ref><ref>Hamilton-Merritt, Jane (1999) ''Tragic Mountains: The Hmong, the Americans, and the Secret Wars for Laos, 1942–1992'', Indiana University Press, pp. 337–460, ISBN 0253207568.</ref> with up to 100,000 killed out of a population of 400,000.<ref>{{cite book|author=Al Santoli and Eisenstein, Laurence J.|title=Forced back and forgotten: the human rights of Laotian asylum seekers in Thailand|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=r6GPAAAAMAAJ|year=1989 |publisher=Lawyers Committee for Human Rights|isbn=978-0-934143-25-7|page=8}}</ref><ref>[http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/SOD.TAB15.1D.GIF Statistics of Democide] Rudolph Rummel</ref> From 1975 to 1996, the United States resettled some 250,000 Lao refugees from Thailand, including 130,000 Hmong.<ref>[http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/2770.htm Laos (04/09)]. U.S. Department of State.</ref> (See: [[Indochina refugee crisis]]) |

|||

The [[Insurgency in Laos|conflict]] between [[Hmong people|Hmong]] rebels and Laos [[Insurgency in Laos|continued in areas]] of Laos, including in Saysaboune Closed Military Zone, Xaisamboune Closed Military Zone near Vientiane Province and [[Xiangkhouang Province]]. From 1975 to 1996, the [[United States]] resettled some [[Indochina refugee crisis|250,000 Lao refugees]] from Thailand, including 130,000 Hmong.<ref>[https://2009-2017.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/2770.htm Laos (04/09)] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201024185208/https://2009-2017.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/2770.htm |date=24 October 2020 }}. U.S. Department of State.{{failed verification|date=January 2021}}</ref> |

|||

==Geography== |

|||

On 27 May 2016, the [[8th Government of Laos]] banned the exports of timber, with an express aim to help control the country's high deforestation rates and boost the country's domestic wood production industry. |

|||

On 3 December 2021, the 422-kilometre [[Boten-Vientiane railway]], a flagship of the [[Belt and Road Initiative]] (BRI), was opened.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Completed China-Laos Railway |url=https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/the-completed-china-laos-railway/ |website=ASEAN Business News |language=en |date=21 December 2021 |access-date=18 May 2022 |archive-date=12 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220512130726/https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/the-completed-china-laos-railway/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

== Geography == |

|||

{{Main|Geography of Laos}} |

{{Main|Geography of Laos}} |

||

[[File:Mekong River (Luang Prabang).jpg|thumb|[[Mekong River]] flowing through [[Luang Prabang]]]] |

[[File:Mekong River (Luang Prabang).jpg|thumb|[[Mekong River]] flowing through [[Luang Prabang]] ]] |

||

[[File:Laos ricefields.JPG|thumb|[[ |

[[File:Laos ricefields.JPG|thumb|[[Paddy fields]] in Laos]] |

||

Laos is the only landlocked country in Southeast Asia, and it lies mostly between latitudes [[14th parallel north|14°]] and [[23rd parallel north|23°N]] ( |

Laos is the only landlocked country in [[Southeast Asia]], and it lies mostly between latitudes [[14th parallel north|14°]] and [[23rd parallel north|23°N]] (an area is south of 14°), and longitudes [[100th meridian east|100°]] and [[108th meridian east|108°E]]. Its forested landscape consists mostly of mountains, the highest of which is [[Phou Bia]] at {{convert|2818|m|ft|0}}, with some plains and plateaus. The Mekong River forms a part of the western boundary with Thailand, where the mountains of the [[Annamite Range]] form most of the eastern border with Vietnam and the [[Luang Prabang Range]] the northwestern border with the [[Thai highlands]]. There are 2 plateaus, the [[Xiangkhoang Plateau|Xiangkhoang]] in the north and the [[Bolaven Plateau]] at the southern end. Laos can be considered to consist of 3 geographical areas: north, central, and south.<ref name="autogenerated3">{{cite web|title=Nsc Lao Pdr|url=http://www.nsc.gov.la/Products/Populationcensus2005/PopulationCensus2005_chapter2.htm|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120123082302/http://www.nsc.gov.la/Products/Populationcensus2005/PopulationCensus2005_chapter2.htm|archive-date=23 January 2012|publisher=Nsc.gov.la}}</ref> Laos had a 2019 [[Forest Landscape Integrity Index]] mean score of 5.59/10, ranking it 98th globally out of 172 countries.<ref name="FLII-Supplementary">{{cite journal|last1=Grantham|first1=H. S.|display-authors=et al.|title=Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity|journal=Nature Communications|volume=11|issue=1|year=2020|page=5978|issn=2041-1723|doi=10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3|pmid=33293507|pmc=7723057|bibcode=2020NatCo..11.5978G}}</ref> |

||

In 1993, the Laos government set aside 21% of the nation's land area for [[habitat conservation]] preservation.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://indochinatrek.com/laos/lao-guides.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101110175658/http://indochinatrek.com/laos/lao-guides.html|archive-date=10 November 2010 |title=Laos travel guides|publisher=Indochinatrek.com |access-date=23 January 2011}}</ref> The country is 1 of 4 in the opium poppy growing region known as the "[[Golden Triangle (Southeast Asia)|Golden Triangle]]".<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=123604085|title=Mekong Divides Different Worlds In 'Golden Triangle'|website=NPR.org|access-date=1 February 2019|archive-date=4 February 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210204231526/https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=123604085|url-status=live}}</ref> According to the October 2007 UNODC fact book ''Opium Poppy Cultivation in South East Asia'', the poppy cultivation area was {{convert|15|km2|sqmi}}, down from {{convert|18|km2|sqmi}} in 2006.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/2007-opium-SEAsia.pdf|title=Opium Poppy Cultivation in South East Asia|date=October 2007|website=UNODC|access-date=28 January 2020|archive-date=8 March 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210308175047/https://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/2007-opium-SEAsia.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

There is a distinct rainy season from May to November, followed by a dry season from December to April. Local tradition holds that there are three seasons (rainy, cold and hot) as the latter two months of the climatologically defined dry season are noticeably hotter than the earlier four months. The capital and largest city of Laos is Vientiane and other major cities include [[Luang Prabang]], [[Savannakhet (city)|Savannakhet]], and [[Pakse]].{{citation needed|date=June 2012}} |

|||

=== Climate === |

|||

In 1993 the Laos government set aside 21% of the nation's land area for habitat conservation preservation.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://indochinatrek.com/laos/lao-guides.html|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20101110175658/http://indochinatrek.com/laos/lao-guides.html|archivedate=10 November 2010 |title=Laos travel guides|publisher=Indochinatrek.com |accessdate=23 January 2011}}</ref> The country is one of four in the opium poppy growing region known as the "[[Golden Triangle (Southeast Asia)|Golden Triangle]]". According to the October 2007 UNODC fact book ''Opium Poppy Cultivation in South East Asia'', the poppy cultivation area was {{convert|15|km2|sqmi}}, down from {{convert|18|km2|sqmi}} in 2006. |

|||

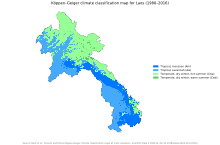

[[File:Koppen-Geiger Map LAO present.svg|thumb|Köppen climate classification map of Laos]] |

|||

The climate is mostly tropical savanna and influenced by the [[monsoon]] pattern.<ref name="climate">{{cite web|title=Laos – Climate|url=http://countrystudies.us/laos/45.htm|access-date=23 January 2011|publisher=Countrystudies.us|archive-date=20 May 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110520154327/http://countrystudies.us/laos/45.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> There is a rainy season from May to October, followed by a dry season from November to April. Local tradition holds that there are three seasons: rainy, cool and hot. Further, the latter two months of the climatologically defined dry season are hotter than the earlier four months.<ref name="climate"/> |

|||

===Wildlife=== |

|||

Laos can be considered to consist of three geographical areas: north, central, and south.<ref name="autogenerated3">{{cite web|url=http://www.nsc.gov.la/Products/Populationcensus2005/PopulationCensus2005_chapter2.htm |title=Nsc Lao Pdr |publisher=Nsc.gov.la |date= |accessdate=21 January 2012}}</ref> |

|||

{{Main|Wildlife of Laos}} |

|||

===Administrative divisions=== |

=== Administrative divisions === |

||

{{Main|Administrative divisions of Laos}} |

{{Main|Administrative divisions of Laos}} |

||

Laos is divided into 17 [[Provinces of Laos|provinces]] (''khoueng'') and one prefecture (''kampheng nakhon'') which includes the capital city Vientiane (''Nakhon Louang Viangchan''). |

|||

Provinces are further divided into [[Districts of Laos|district]]s (''muang'') and then villages (''ban''). An 'urban' village is essentially a town.<ref name="autogenerated3"/> |

|||

Laos is divided into 17 [[Provinces of Laos|provinces]] (''khoueng'') and one prefecture (''kampheng nakhon''), which includes the capital city Vientiane (''Nakhon Louang Viangchan'').<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/laos/|title=East Asia/Southeast Asia :: |website=The World Factbook |access-date=23 May 2019|archive-date=7 March 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210307193820/https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/laos/|url-status=live}}</ref> A province, [[Xaisomboun province]], was established on 13 December 2013.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.tourismlaos.org/show_province.php?Cont_ID=919|title=ABOUT XAYSOMBOUN|website=tourismlaos.org|access-date=23 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190507160148/http://tourismlaos.org/show_province.php?Cont_ID=919|archive-date=7 May 2019|url-status=dead}}</ref> Provinces are divided into [[Districts of Laos|districts]] (''muang'') and then villages (''ban''). An "urban" village is essentially a town.<ref name="autogenerated3"/> |

|||

{| style="float:left;" |

{| style="float:left;" |

||

| |

| |

||

{| class="sortable wikitable" style="text-align:left; font-size:90%;" |

{| class="sortable wikitable" style="text-align:left; font-size:90%;" |

||

|- style="font-size:100%; text-align:right;" |

|- style="font-size:100%; text-align:right;" |

||

! scope="col" | No. |

|||

! № !! [[Provinces of Laos|Subdivisions]] !! Capital !! Area (km²)!! Population |

|||

! scope="col" | [[Provinces of Laos|Subdivisions]] |

|||

! scope="col" | Capital |

|||

! scope="col" | Area (km<sup>2</sup>) |

|||

! scope="col" | Population |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! 1 |

|||