Welsh English: Difference between revisions

Link |

|||

| (269 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ |

{{short description|Dialect of the English language}} |

||

{{redirect|Saesneg|the language called "Welsh"|Welsh language}} |

|||

{{cleanup-bare URLs|date=May 2013}} |

|||

{{use Welsh English|date=August 2019}} |

|||

{{use dmy dates|date=August 2019}} |

|||

{{Infobox language |

{{Infobox language |

||

|name = Welsh English |

|name = Welsh English |

||

|nativename = |

|nativename = |

||

|states = |

|states = [[United Kingdom]] |

||

|region = |

|region = [[Wales]] |

||

| |

|ethnicity = [[Welsh people]] |

||

| |

|speakers = 2.5 million{{citation needed|date=July 2023}} |

||

|date = no date |

|||

|ref = |

|||

|script = [[Latin script|Latin]] ([[English alphabet]]) |

|script = [[Latin script|Latin]] ([[English alphabet]]) |

||

|familycolor |

|familycolor=Indo-European |

||

|fam2 |

|fam2=[[Germanic languages|Germanic]] |

||

|fam3 |

|fam3=[[West Germanic languages|West Germanic]] |

||

|fam4 |

|fam4=[[Ingvaeonic languages|Ingvaeonic]] |

||

|fam5 |

|fam5=[[Anglo-Frisian languages|Anglo-Frisian]] |

||

|fam6=[[Anglic languages|Anglic]] |

|||

|fam7=[[English language|English]] |

|||

|fam8=[[British English]] |

|||

|ancestor=[[Old English]] |

|||

|ancestor2=[[Middle English]] |

|||

|ancestor3=[[Early Modern English]] |

|||

| dia1 = [[Abercraf English|Abercraf]] |

|||

| dia2 = [[Gower dialect|Gower]] |

|||

| dia3 = [[Port Talbot English|Port Talbot]] |

|||

| dia4 = [[Cardiff English|Cardiff]] |

|||

|isoexception = dialect |

|isoexception = dialect |

||

|glotto=none |

|glotto=none |

||

|notice = IPA |

|notice = IPA |

||

}} |

}} |

||

{{listen|filename=Rob Brydon BBC Radio4 Front Row 18 Mar 2012 b01dhl11.flac|type=speech|title=Speech example|description=An example of a male with a South Wales accent ([[Rob Brydon]]).}} |

|||

'''Welsh English''', '''Anglo-Welsh''', or '''Wenglish''' (see below) refers to the [[dialect]]s of [[English language|English]] spoken in [[Wales]] by [[Welsh people]]. The dialects are significantly influenced by [[Welsh language|Welsh]] [[grammar]] and often include words derived from Welsh. In addition to the distinctive words and grammar, there is a variety of [[Accent (dialect)|accent]]s found across Wales from the [[Cardiff dialect]] to that of the [[South Wales Valleys]] and to [[West Wales]]. |

|||

{{English language}} |

|||

'''Welsh English''' ({{langx|cy|Saesneg Gymreig}}) comprises the [[dialect]]s of English spoken by [[Welsh people]]. The dialects are significantly influenced by [[Welsh language|Welsh]] [[grammar]] and often include words derived from Welsh. In addition to the distinctive words and grammar, a variety of [[Accent (dialect)|accent]]s are found across Wales, including those of [[North Wales]], the [[Cardiff dialect]], the [[South Wales Valleys]] and [[West Wales]]. |

|||

In the east and south east, it has been influenced by [[West Country dialects]] due to immigration,{{citation needed|date=March 2014}} while in North Wales, the influence of [[Scouse|Merseyside English]] is becoming increasingly prominent. |

|||

While other [[English language in England|accents and dialects from England]] have affected those of English in Wales, especially in the east of the country, influence has moved in both directions, those in the west have been more heavily influenced by the Welsh language, those in north-east Wales and parts of the North Wales coastline it have been influenced by [[English language in Northern England|Northwestern English]], and those in the mid-east and the south-east Wales (composing the South Wales Valleys) have been influenced by [[West Country English|West Country]] and [[West Midlands English]],<ref name="Revealed: the wide range of Welsh accents">{{cite web |author=Rhodri Clark |date=2007-03-27 |title=Revealed: the wide range of Welsh accents |url=https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/wales-news/revealed-wide-range-welsh-accents-2269968 |access-date=31 January 2019 |website=Wales Online}}</ref><ref name="Secret behind our Welsh accents discovered">{{cite web |date=2006-06-07 |title=Secret behind our Welsh accents discovered |url=https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/wales-news/secret-behind-welsh-accents-discovered-2332160 |access-date=31 January 2010 |website=Wales Online}}</ref> and the one from [[Cardiff]] have been influenced by [[Midlands]], West Country, and [[Hiberno-English]].<ref name="A Cardiff Story">{{cite news |last=Carney |first=Rachel |date=16 December 2010 |title=A Cardiff Story: A migrant city |url=https://www.theguardian.com/cardiff/2010/dec/15/a-cardiff-story-a-migrant-city-rachel-carney |access-date=16 December 2010 |work=The Guardian Cardiff |location=Cardiff}}</ref> |

|||

A colloquial [[portmanteau word]] for Welsh English is '''Wenglish'''. It has been in use since 1985.<ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1075/eww.00001.lam | title = A multitude of "lishes" | year = 2018 | last1 = Lambert | first1 = James | journal = English World-Wide. A Journal of Varieties of English | volume = 39 | pages = 1–33 }}</ref> |

|||

{{Culture of Wales}} |

{{Culture of Wales}} |

||

| Line 29: | Line 48: | ||

====Short monophthongs==== |

====Short monophthongs==== |

||

* The vowel of ''cat'' {{IPA|/æ/}} is pronounced as a more central [[near-open front unrounded vowel]] {{IPA|[æ̈]}}.<ref name="bare_url"> |

* The vowel of ''cat'' {{IPA|/æ/}} is pronounced either as an [[open front unrounded vowel]] {{IPA|[a]}}{{sfnp|Wells|1982|pp=380, 384–385}}{{sfnp|Connolly|1990|pp=122, 125}} or a more central [[near-open front unrounded vowel]] {{IPA|[æ̈]}}.<ref name="bare_url">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tPwYt3gVbu4C&q=welsh+vowels&pg=PA138 |title=English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books |access-date=2015-02-22|isbn=9781853590313 |last1=Coupland |first1=Nikolas |last2=Thomas |first2=Alan Richard |year=1990a|publisher=Multilingual Matters }}{{page needed|date=February 2021|reason=URL is a search}}</ref> In [[Cardiff]], ''bag'' is pronounced with a long vowel {{IPA|[aː]}}.<ref name="bare_url_c">{{harvp|Wells|1982|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=a3-ElL71fikC&q=North+Wales 384, 387, 390]}}</ref> In [[Mid-Wales]], a pronunciation resembling its [[New Zealand English|New Zealand]] and [[South African English|South African]] analogue is sometimes heard, i.e. ''trap'' is pronounced {{IPA|/trɛp/}}.<ref name="bare_url_b"/> |

||

* The vowel of ''end'' {{IPA|/ɛ/}} is |

* The vowel of ''end'' {{IPA|/ɛ/}} is pronounced close to [[cardinal vowel]] {{IPA|[ɛ]}}, similar to modern [[Received Pronunciation|RP]].<ref name="bare_url" /> |

||

* |

* In Cardiff, the vowel of "kit" {{IPA|/ɪ/}} sounds slightly closer to the [[schwa]] sound of ''above'', an advanced [[close-mid central unrounded vowel]] {{IPA|[ɘ̟]}}.<ref name="bare_url" /> |

||

* The vowel of "bus" {{IPA|/ʌ/}} is usually pronounced [{{IPA|ɜ}}~{{IPA|ə}}]<ref name="bare_url_a">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tPwYt3gVbu4C&q=%22welsh+English%22+transcription&pg=PA130 |title=English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books |access-date=2015-02-22|isbn=9781853590313 |last1=Coupland |first1=Nikolas |last2=Thomas |first2=Alan Richard |year=1990a|publisher=Multilingual Matters }}{{page needed|date=February 2021|reason=URL is a search}}</ref>{{sfnp|Wells|1982|pp=380–381}} and is encountered as a [[hypercorrection]] in northern areas for ''foot''.<ref name="bare_url_b">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Dptsvykgk3IC&q=uvular+in+welsh&pg=PA110 |title=A Handbook of Varieties of English: CD-ROM. - Google Books |access-date=2015-02-22|isbn=9783110175325 |last1=Schneider |first1=Edgar Werner |last2=Kortmann |first2=Bernd |year=2004 |publisher=Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Company KG }}</ref> It is sometimes manifested in border areas of north and mid Wales as an [[open front unrounded vowel]] {{IPA|/a/}}. It also manifests as a [[near-close near-back rounded vowel]] {{IPA|/ʊ/}} without the [[Phonological history of English close back vowels#FOOT–STRUT split|foot–strut split]] in parts of North Wales it influenced the [[Cheshire dialect|Cheshire]] and [[Scouse]] accents,<ref name="bare_url_b"/> and to a lesser extent in south Pembrokeshire.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/top-stories/pembrokeshire-wales-little-england-history-1-6016252|last=Trudgill|first=Peter|publisher=The New European|title=Wales's very own little England|date=27 April 2019|access-date=16 April 2020}}</ref> |

|||

* The vowel of ''hot'' {{IPA|/ɒ/}} is raised towards {{IPA|/ɔ/}} and can thus be transcribed as {{IPA|[ɒ̝]}} or {{IPA|[ɔ̞]}}<ref name="bare_url" /> |

|||

* The [[schwa]] tends to be supplanted by an {{IPA|/ɛ/}} in final closed syllables, e.g. ''brightest'' {{IPA|/ˈbrəitɛst/}}. The uncertainty over which vowel to use often leads to 'hypercorrections' involving the schwa, e.g. ''programme'' is often pronounced {{IPA|/ˈproːɡrəm/}}.<ref name="bare_url_c" /> |

|||

* The vowel of "bus" {{IPA|/ʌ/}} is pronounced {{IPA|[ɜ]}}<ref name="bare_url_a">http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=tPwYt3gVbu4C&oi=fnd&pg=PA130&dq=%22welsh+English%22+transcription&ots=G0PNdy_-Sp&sig=BwgabVXAbnBIqC8aPpSM9fuXYzo#v=onepage&q&f=false; page 135</ref> and is encountered as a [[hypercorrection]] in northern areas for ''foot''.<ref name="bare_url_d">http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=Dptsvykgk3IC&pg=PA110&lpg=PA110&dq=uvular+in+welsh&source=bl&ots=IPyJTk5G-G&sig=exbjLELRy0oSPwWlNMdLPH13-O0&hl=en&ei=04mkTOuoDcK4jAeRkvnADA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CB0Q6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=uvular%20in%20welsh&f=false; page 104</ref> It is sometimes manifested in border areas of north and mid Wales as an [[open front unrounded vowel]] {{IPA|/a/}} or as a [[near-close near-back vowel]] {{IPA|/ʊ/}} in northeast Wales, under influence of [[Cheshire]] and [[Scouse|Merseyside]] accents.<ref name="bare_url_b">http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=Dptsvykgk3IC&pg=PA110&lpg=PA110&dq=uvular+in+welsh&source=bl&ots=IPyJTk5G-G&sig=exbjLELRy0oSPwWlNMdLPH13-O0&hl=en&ei=04mkTOuoDcK4jAeRkvnADA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CB0Q6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=uvular%20in%20welsh&f=false; page 103</ref> |

|||

* In accents that distinguish between [[Phonological history of English high back vowels|''foot'' and ''strut'']], the vowel of ''foot'' is a more lowered vowel {{IPA|[ɤ̈]}},<ref name="bare_url_a" /> particularly in the north<ref name="bare_url_b" /> |

|||

* The [[schwa]] of ''better'' may be different from that of ''above'' in some accents; the former may be pronounced as {{IPA|[ɜ]}}, the same vowel as that of ''bus''<ref>{{cite book|url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=tPwYt3gVbu4C&pg=PA138&dq=welsh+vowels&hl=en&ei=tW9ATM2gFYGl4QaL_dG8Dg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CD4Q6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=welsh%20vowels&f=false; |title=page 145 |publisher=Books.google.co.uk |date= |accessdate=2012-11-21}}</ref> |

|||

* The [[schwi]] tends to be supplanted by an {{IPA|/ɛ/}} in final closed syllables, e.g. ''brightest'' {{IPA|/ˈbɾəi.tɛst/}}. The uncertainty over which vowel to use often leads to 'hypercorrections' involving the schwa, e.g. ''programme'' is often pronounced {{IPA|/ˈproː.ɡrəm/}}<ref name="bare_url_c" /> |

|||

====Long monophthongs==== |

====Long monophthongs==== |

||

[[File:Abercrave English monophthongs chart.svg|thumb|Monophthongs of Welsh English as they are pronounced in Abercrave, from {{ |

[[File:Abercrave English monophthongs chart.svg|thumb|Monophthongs of Welsh English as they are pronounced in Abercrave, from {{harvp|Coupland|Thomas|1990|pp=135–136}}.]] |

||

[[File:Cardiff English monophthongs chart.svg|thumb|Monophthongs of Welsh English as they are pronounced in Cardiff, from {{ |

[[File:Cardiff English monophthongs chart.svg|thumb|Monophthongs of Welsh English as they are pronounced in Cardiff, from {{harvp|Coupland|Thomas|1990|pp=93–95}}. Depending on the speaker, the long {{IPA|/ɛː/}} may be of the same height as the short {{IPA|/ɛ/|cat=no}}.{{sfnp|Coupland|Thomas|1990|p=95}}]] |

||

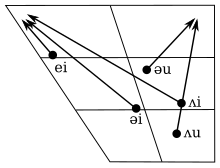

[[File:Abercrave English diphthongs chart.svg|thumb|Diphthongs of Welsh English as they are pronounced in Abercrave, from {{ |

[[File:Abercrave English diphthongs chart.svg|thumb|Diphthongs of Welsh English as they are pronounced in Abercrave, from {{harvp|Coupland|Thomas|1990|pp=135–136}}]] |

||

[[File:Cardiff English diphthongs chart.svg|thumb|Diphthongs of Welsh English as they are pronounced in Cardiff, from {{ |

[[File:Cardiff English diphthongs chart.svg|thumb|Diphthongs of Welsh English as they are pronounced in Cardiff, from {{harvp|Coupland|Thomas|1990|p=97}}]] |

||

* The [[trap-bath split]] is variable in Welsh English, especially among social status. In some varieties such as [[Cardiff English]], words like ask, bath, laugh, master and rather are usually pronounced with PALM while words like answer, castle, dance and nasty are normally pronounced with TRAP. On the other hand, the split may be completely absent in other varieties like [[Abercraf English]].{{sfnp|Wells|1982|p=387}} |

|||

* The vowel of ''car'' is often pronounced as a more central [[open back unrounded vowel]] {{IPA|[ɑ̈]}}<ref>{{cite book|url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=tPwYt3gVbu4C&pg=PA138&dq=welsh+vowels&hl=en&ei=tW9ATM2gFYGl4QaL_dG8Dg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CD4Q6AEwAw#v=snippet&q=stigmatised&f=false; |title=page 135 |publisher=Books.google.co.uk |date= |accessdate=2012-11-21}}</ref> and more often as a long [[open front unrounded vowel]] {{IPA|/aː/}}<ref name="bare_url_d" /> |

|||

* |

* The vowel of ''car'' is often pronounced as an [[open central unrounded vowel]] {{IPA|[ɑ̈]}}<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tPwYt3gVbu4C&q=stigmatised&pg=PA138 |title=English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books |access-date=2015-02-22|isbn=9781853590313 |last1=Coupland |first1=Nikolas |last2=Thomas |first2=Alan Richard |year=1990a|publisher=Multilingual Matters }}{{page needed|date=February 2021|reason=URL is a search}}</ref> and more often as a long [[open front unrounded vowel]] {{IPA|/aː/}}.<ref name="bare_url_b"/> |

||

* In broader varieties, particularly in Cardiff, the vowel of ''bird'' is similar to [[South African English|South African]] and [[New Zealand English|New Zealand]], i.e. a [[mid front rounded vowel]] {{IPA|[ø̞ː]}}.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tPwYt3gVbu4C&q=rounded&pg=PA130 |title=English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books |access-date=2015-02-22|isbn=9781853590313 |last1=Coupland |first1=Nikolas |last2=Thomas |first2=Alan Richard |year=1990a|publisher=Multilingual Matters }}{{page needed|date=February 2021|reason=URL is a search}}</ref> |

|||

* Most other long monophthongs are similar to that of [[Received Pronunciation]], but words with the RP {{IPA|/əʊ/}} are sometimes pronounced as {{IPA|[oː]}} and the RP {{IPA|/eɪ/}} as {{IPA|[eː]}}. An example that illustrates this tendency is the [[Abercrave]] pronunciation of ''play-place'' {{IPA|[ˈpleɪˌpleːs]}}<ref>{{cite book|url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=tPwYt3gVbu4C&pg=PA138&dq=welsh+vowels&hl=en&ei=JPRFTNugKovU4wblgrX7CQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CD4Q6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=playplace&f=false; |title=page 134 |publisher=Books.google.co.uk |date= |accessdate=2012-11-21}}</ref> |

|||

* Most other long monophthongs are similar to that of [[Received Pronunciation]], but words with the RP {{IPA|/əʊ/}} are sometimes pronounced as {{IPA|[oː]}} and the RP {{IPA|/eɪ/}} as {{IPA|[eː]}}. An example that illustrates this tendency is the [[Abercrave]] pronunciation of ''play-place'' {{IPA|[ˈpleɪˌpleːs]}}.<ref name="google1">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tPwYt3gVbu4C&q=playplace&pg=PA138 |title=English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books |access-date=2015-02-22|isbn=9781853590313 |last1=Coupland |first1=Nikolas |last2=Thomas |first2=Alan Richard |year=1990a|publisher=Multilingual Matters }}{{page needed|date=February 2021|reason=URL is a search}}</ref> |

|||

* In [[North Wales|northern]] varieties, {{IPA|/əʊ/}} as in ''coat'' and {{IPA|/ɔː/}} as in ''caught/court'' are often merged into {{IPA|/ɔː/}} (phonetically {{IPAblink|oː}}).<ref name="bare_url_c" /> |

|||

* In [[North Wales|northern]] varieties, {{IPA|/əʊ/}} as in ''coat'' and {{IPA|/ɔː/}} as in ''caught/court'' may be merged into {{IPA|/ɔː/}} (phonetically {{IPAblink|oː}}).<ref name="bare_url_c" /> |

|||

* In [[Rhymney]], the diphthong of ''there'' is monophthongised {{IPA|[ɛː]}}<ref>{{cite web|author=Paul Heggarty |url=http://www.soundcomparisons.com/Eng/Direct/Englishes/SglLgRhymneyTyp.htm |title=Sound Comparisons |publisher=Sound Comparisons |date= |accessdate=2012-11-21}}</ref> |

|||

====Diphthongs==== |

====Diphthongs==== |

||

* Fronting diphthongs tend to resemble Received Pronunciation, apart from the vowel of ''bite'' that has a more centralised onset {{IPA|[æ̈ɪ]}}<ref |

* Fronting diphthongs tend to resemble Received Pronunciation, apart from the vowel of ''bite'' that has a more centralised onset {{IPA|[æ̈ɪ]}}.<ref name="google1"/> |

||

* Backing diphthongs are more varied:<ref name="google1"/> |

|||

* Backing diphthongs are more varied:<ref>{{cite book|url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=tPwYt3gVbu4C&pg=PA138&dq=welsh+vowels&hl=en&ei=JPRFTNugKovU4wblgrX7CQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CD4Q6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=playplace&f=false; |title=page 136 |publisher=Books.google.co.uk |date= |accessdate=2012-11-21}}</ref> |

|||

**The vowel of ''low'' in RP, other than being rendered as a monophthong, like described above, is often pronounced as {{IPA|[oʊ̝]}} |

**The vowel of ''low'' in RP, other than being rendered as a monophthong, like described above, is often pronounced as {{IPA|[oʊ̝]}}. |

||

**The word ''town'' is pronounced |

**The word ''town'' is pronounced with a [[near-open central vowel|near-open central]] onset {{IPA|[ɐʊ̝]}}. |

||

*Welsh English is one of few dialects where the Late Middle English diphthong {{IPA|/iu̯/}} never [[ju:|became {{IPA|/juː/|cat=no}}]], remaining as a falling diphthong {{IPA|[ɪʊ̯]}}. Thus ''you'' {{IPA|/juː/}}, ''yew'' {{IPA|/jɪʊ̯/}}, and ''ewe'' {{IPA|/ɪʊ̯/}} are not homophones in Welsh English. As such [[yod-dropping]] never occurs: distinctions are made between ''choose'' {{IPA|/t͡ʃuːz/}} and ''chews'' {{IPA|/t͡ʃɪʊ̯s/}}, ''through'' {{IPA|/θruː/}} and ''threw'' {{IPA|/θrɪʊ̯/}}, which most other English varieties do not have. |

|||

**The {{IPA|/juː/}} of RP in the word ''due'' is usually pronounced as a true diphthong {{IPA|[ëʊ̝]}} |

|||

<!--See also previous "confusing" phonology table [] for more info--> |

|||

:::{| class="wikitable" style="margin: 1em 2em" |

|||

|+ Correspondence between the [[Help:IPA for English|IPA help key]] and Welsh English vowels (many individual words do not correspond) |

|||

! colspan="3"| Pure vowels |

|||

|- |

|||

! Help key !! Welsh !! Examples |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/ɪ/}} || {{IPA|/ɪ/ ~ /ɪ̈/ ~ /ɘ/}} ||b'''i'''d, p'''i'''t |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/iː/}} || {{IPA|/i/}} || b'''ea'''d, p'''ea'''t |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/ɛ/}} || {{IPA|/ɛ/}} || b'''e'''d, p'''e'''t |

|||

|- |

|||

| rowspan=2|{{IPA|/eɪ/}} || {{IPA|/e/~/eɪ/}} || f'''a'''te, g'''a'''te |

|||

|- |

|||

||{{IPA|/eɪ/}} || b'''ay''', h'''ey''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/æ/}} || {{IPA|/a/}} || b'''a'''d, p'''a'''t, b'''arr'''ow, m'''arr'''y |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/ɑː/}} || {{IPA|/aː/}} || b'''a'''lm, f'''a'''ther, p'''a''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/ɒ/}} || {{IPA|/ɒ/}} || b'''o'''d, p'''o'''t, c'''o'''t |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/ɔː/}} || {{IPA|/ɒː/}} ||b'''aw'''d, p'''aw''', c'''augh'''t |

|||

|- |

|||

| rowspan=2|{{IPA|/oʊ/}} || {{IPA|/o/~/oʊ/}} || b'''eau''', h'''oe''', p'''o'''ke |

|||

|- |

|||

|| {{IPA|/oʊ/}} || s'''ou'''l,l'''ow''',t'''ow''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/ʊ/}} || {{IPA|/ʊ/}} || g'''oo'''d, f'''oo'''t, p'''u'''t |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/uː/}} || {{IPA|/uː/}} ||b'''oo'''ed, f'''oo'''d |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/ʌ/}} || {{IPA|/ə/~/ʊ/}} || b'''u'''d, p'''u'''tt |

|||

|- |

|||

! colspan="3" | [[Diphthong]]s |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/aɪ/}} || {{IPA|/aɪ/ ~ /əɪ/}} || b'''uy''', r'''i'''de, wr'''i'''te |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/aʊ/}} || {{IPA|/aʊ̝/ ~ /əʊ̝/~ /ɐʊ̝/}} || h'''ow''', p'''ou'''t |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/ɔɪ/}} || {{IPA|/ɒɪ/}} || b'''oy''', h'''oy''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/juː/}} || {{IPA|/ɪu/~/ëʊ̝/}} || h'''ue''', p'''ew''', n'''ew''' |

|||

|- |

|||

! colspan="3" | [[R-colored vowel|R-coloured vowel]]s (these do not exist in Scots) |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/ɪər/}} || {{IPA|/ɪə̯(ɾ)/}} || b'''eer''', m'''ere''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/ɛər/}} || {{IPA|/ɛə̯(ɾ)/}} || b'''ear''', m'''are''', M'''ar'''y |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/ɑr/}} ||{{IPA|/aː(ɾ)/}} || b'''ar''', m'''ar''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/ɔr/}} || {{IPA|/ɒː(ɾ)/}} || m'''or'''al, f'''or'''age,b'''or'''n, f'''or''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/ɔər/}} || {{IPA|/oː(ɾ)/}} || b'''oar''', f'''our''', m'''ore''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/ʊər/}} || {{IPA|/ʊə̯(ɾ)/}} || b'''oor''', m'''oor''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/ɜr/}} || {{IPA|/ɜː/~/øː/}} || b'''ir'''d, h'''er'''d, f'''urr'''y |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IPA|/ər/ (ɚ)}} || {{IPA|/ə(ɾ)/}} || runn'''er''', merc'''er''' |

|||

|} |

|||

===Consonants=== |

===Consonants=== |

||

* Most Welsh accents pronounce /r/ as an [[alveolar flap]] {{IPA|[ɾ]}} (a 'flapped r'), similar to [[Scottish English]] and some [[English language in Northern England|Northern English]] and [[South African English|South African]] accents, in place of an [[Voiced alveolar and postalveolar approximants|approximant]] {{IPA|[ɹ]}} like in most accents in England<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tPwYt3gVbu4C&q=alveolar+tap&pg=PA130 |title=English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books |access-date=2015-02-22 |isbn=9781853590313 |last1=Coupland |first1=Nikolas |last2=Thomas |first2=Alan Richard |year=1990a|publisher=Multilingual Matters }}{{page needed|date=February 2021|reason=URL is a search}}</ref> while an [[alveolar trill]] {{IPA|[r]}} may also be used under the influence of [[Welsh language|Welsh]].<ref>{{cite book |title=Investigating Language Attitudes: Social Meanings of Dialect, Ethnicity and Performance |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Q2-uBwAAQBAJ&q=welsh+english+trilled+r&pg=PT88 |date=15 July 2003 |publisher=University of Wales Press |editor1=Peter Garrett |editor2=Nikolas Coupland |editor3=Angie Williams |isbn=9781783162086 |page=73 |access-date=2 September 2019}}</ref> |

|||

* A strong tendency (shared with [[Scottish English]] and some [[South African English|South African]] accents) towards using an [[alveolar tap]] {{IPA|[ɾ]}} (a 'tapped r') in place of an approximant {{IPA|[ɹ]}} (the r used in most accents in England).<ref>{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=tPwYt3gVbu4C&oi=fnd&pg=PA130&dq=%22welsh+English%22+transcription&ots=G0PNdy_-Sp&sig=BwgabVXAbnBIqC8aPpSM9fuXYzo#v=onepage&q=alveolar%20tap&f=false; |title=page 131 |publisher=Books.google.com |date= |accessdate=2012-11-21}}</ref> |

|||

* [[ |

* Welsh English is mostly [[Rhoticity in English|non-rhotic]], however variable rhoticity can be found in accents influenced by Welsh, especially [[North Wales|northern]] varieties. Additionally, while [[Port Talbot English]] is mostly non-rhotic like other varieties of Welsh English, some speakers may supplant the front vowel of ''bird'' with {{IPA|/ɚ/}}, like in many varieties of [[North American English]].<ref name="google2">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tPwYt3gVbu4C&q=rhotic&pg=PA138 |title=English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books |access-date=2015-02-22|isbn=9781853590313 |last1=Coupland |first1=Nikolas |last2=Thomas |first2=Alan Richard |year=1990a|publisher=Multilingual Matters }}{{page needed|date=February 2021|reason=URL is a search}}</ref> |

||

* [[H-dropping]] is common in many Welsh accents, especially [[South Wales|southern]] varieties like [[Cardiff English]],{{sfnp|Coupland|1988|p=29}} but is absent in northern and [[West Wales|western]] varieties influenced by Welsh.<ref>{{cite book |title=Approaches to the Study of Sound Structure and Speech: Interdisciplinary Work in Honour of Katarzyna Dziubalska-Kołaczyk |date=21 October 2019 |publisher=Magdalena Wrembel, Agnieszka Kiełkiewicz-Janowiak and Piotr Gąsiorowski |pages=1–398 |isbn=9780429321757 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hh24DwAAQBAJ&q=h+dropping+north+wales&pg=PT22}}</ref> |

|||

* Some [[gemination]] between vowels is often encountered, e.g. ''money'' is pronounced {{IPA|[ˈmɜ.nːiː]}}<ref name="CrystalDavid">Crystal, David (2003). ''The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language Second Edition'', Cambridge University Press, pp. 335</ref> |

|||

* Some [[gemination]] between vowels is often encountered, e.g. ''money'' is pronounced {{IPA|[ˈmɜn.niː]}}.{{sfnp|Crystal|2003|p=335}} |

|||

* In [[North Wales|northern]] varieties influenced by [[Welsh language|Welsh]], ''pens'' and ''pence'' merge into {{IPA|/pɛns/}} and ''chin'' and ''gin'' into {{IPA|/dʒɪn/}}<ref name="CrystalDavid" /> |

|||

* As Welsh lacks the letter Z and the [[voiced alveolar fricative]] /z/, some first-language Welsh speakers replace it with the [[voiceless alveolar fricative]] /s/ for words like ''cheese'' and ''thousand'', while ''pens'' ({{IPA|/pɛnz/}}) and ''pence'' merge into {{IPA|/pɛns/}}, especially in north-west, west and south-west Wales.{{sfnp|Crystal|2003|p=335}}<ref>{{cite book |title=The British Isles |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EeXI43AwwiEC&q=north+west+wales+accent++%2Fz%2F&pg=PA117 |publisher=Bernd Kortmann and Clive Upton |access-date=31 January 2019|isbn=9783110208399 |date=2008-12-10 }}</ref> |

|||

* In the north-east, under influence of such accents as [[Scouse]], [[ng-coalescence|''ng''-coalescence]] does not take place, so ''sing'' is pronounced {{IPA|/sɪŋɡ/}}<ref>{{cite book|url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=a3-ElL71fikC&printsec=frontcover&dq=accents+of+english&hl=en&ei=1AxWTLC2COaX4gaW4vGmBQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDAQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=residualism&f=false; |title=page 390 |publisher=Books.google.co.uk |date= |accessdate=2012-11-21}}</ref> |

|||

* In northern varieties influenced by Welsh, ''chin'' ({{IPA|/tʃɪn/}}) and ''gin'' may also merge into {{IPA|/dʒɪn/}}.{{sfnp|Crystal|2003|p=335}} |

|||

* Also in northern accents, {{IPA|/l/}} is frequently strongly velarised {{IPA|[ɫː]}}. In much of the south-east, [[velarisation|clear and dark L]] alternate much like they do in RP<ref>{{cite book|url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=tPwYt3gVbu4C&pg=PA138&dq=welsh+vowels&hl=en&ei=JPRFTNugKovU4wblgrX7CQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CD4Q6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=rhotic&f=false |title=English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Nikolas Coupland - Google Books |publisher=Books.google.co.uk |date= |accessdate=2012-11-21}}</ref> |

|||

* In the north-east, under influence of such accents as [[Scouse]], [[ng-coalescence|''ng''-coalescence]] does not take place, so ''sing'' is pronounced {{IPA|/sɪŋɡ/}}.{{sfnp|Wells|1982|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=a3-ElL71fikC&pg=PA390 390]}} |

|||

* The consonants are generally the same as RP but Welsh consonants like {{IPA|[ɬ]}} and {{IPA|[x]}} are encountered in loan words such as ''Llangefni'' and ''Harlech''<ref name="CrystalDavid" /> |

|||

* Also in northern accents, {{IPA|/l/}} is frequently strongly velarised {{IPA|[ɫː]}}. In much of the south-east, [[velarisation|clear and dark L]] alternate much like they do in RP.<ref name="google2"/> |

|||

* The consonants are generally the same as RP but Welsh consonants like {{IPAslink|ɬ}} and {{IPAslink|x}} (phonetically {{IPAblink|χ}}) are encountered in loan words such as ''Llangefni'' and ''Harlech''.{{sfnp|Crystal|2003|p=335}} |

|||

==Distinctive vocabulary and grammar== |

==Distinctive vocabulary and grammar== |

||

{{See also|List of English words of Welsh origin}} |

|||

Aside from lexical borrowings from [[Welsh language|Welsh]] like |

Aside from lexical borrowings from [[Welsh language|Welsh]] like {{lang|en-GB|italic=yes|bach}} (little, wee), {{lang|en-GB|italic=yes|[[eisteddfod]]}}, {{lang|en-GB|italic=yes|nain}} and {{lang|en-GB|italic=yes|taid}} (''grandmother'' and ''grandfather'' respectively), there exist distinctive grammatical conventions in vernacular Welsh English. Examples of this include the use by some speakers of the [[tag question]] {{lang|en-GB|italic=yes|isn't it?}} regardless of the form of the preceding statement and the placement of the subject and the verb after the [[Predicate (grammar)|predicate]] for emphasis, e.g. {{lang|en-GB|italic=yes|Fed up, I am}} or {{lang|en-GB|italic=yes|Running on Friday, he is.}}{{sfnp|Crystal|2003|p=335}} |

||

In South Wales the word |

In South Wales the word ''where'' may often be expanded to {{lang|en-GB|italic=yes|where to}}, as in the question, "{{lang|en-GB|italic=yes|Where to is your Mam?}}". The word {{lang|en-GB|italic=yes|butty}} ({{langx|cy|byti}}) is used to mean "friend" or "mate".<ref>{{cite web |title=Why butty rarely leaves Wales |url=https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/wales-news/why-butty-rarely-leaves-wales-2302834|work=Wales Online |date=2 October 2006 |orig-year=updated: 30 Mar 2013 |access-date=22 February 2015}}</ref> |

||

There is no standard variety of English that is specific to Wales, but such features are readily recognised by Anglophones from [[Countries of the United Kingdom|the rest of the UK]] as being from Wales, including the |

There is no standard variety of English that is specific to Wales, but such features are readily recognised by Anglophones from [[Countries of the United Kingdom|the rest of the UK]] as being from Wales, including the phrase {{lang|en-GB|italic=yes|look you}} which is a translation of a Welsh language tag.{{sfnp|Crystal|2003|p=335}} |

||

The word {{lang|en-GB|italic=yes|tidy}} is among "the most over-worked Wenglish words". It carries a number of meanings include - great or excellent, or a large quantity. A {{lang|en-GB|italic=yes|tidy swill}} is a wash that includes, at the least, the hands and the face.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Edwards|first=John|title=Talk Tidy|publisher=D Brown & Sons Ltd|year=1985|isbn=0905928458|location=Bridgend, Wales, UK|pages=39}}</ref> |

|||

==Orthography== |

|||

Spellings are almost identical to other dialects of British English. Minor differences occur with words descended from [[Welsh language|Welsh]] which aren't Anglicised as in many other dialects of English, e.g. in Wales the valley is always "cwm", not the Anglicised version "coombe". As with other dialects of British English, -ise endings are preferred, i.e. "realise" instead of "realize". However, both forms are acceptable. For words ending in 'yse' or 'yze', the 'yse' endings are compulsory, as with other dialects of British English, i.e. "analyse", not "analyze". |

|||

==Code-switching== |

|||

==History of the English language in Wales== |

|||

As Wales has become increasingly more anglicised, [[code-switching]] has become increasingly more common.<ref name=":0"/><ref name=":1" >{{Cite journal|last=Deuchar|first=Margaret|date=December 2005|title=Congruence and Welsh–English code-switching|journal=Bilingualism: Language and Cognition|language=en|volume=8|issue=3|pages=255–269|doi=10.1017/S1366728905002294|s2cid=144548890|issn=1469-1841}}</ref> |

|||

The presence of English in Wales intensified on the passing of the [[Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542|Laws in Wales Acts of 1535–1542]], the [[Statute law|statutes]] having promoted the dominance of English in Wales; this, coupled with the [[Dissolution of the Monasteries|closure of the monasteries]], which closed down many centres of Welsh education, led to decline in the use of the [[Welsh language]]. |

|||

===Examples=== |

|||

The decline of Welsh and the ascendancy of [[English language|English]] was intensified further during the [[Industrial Revolution]], when many Welsh speakers moved to England to find work and the recently developed [[Mining in the United Kingdom|mining]] and [[smelting]] industries came to be manned by Anglophones. [[David Crystal]], who grew up in [[Holyhead]], claims that the continuing dominance of English in Wales is little different from its spread elsewhere in the world.<ref>Crystal, David (2003). ''The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language Second Edition'', Cambridge University Press, p. 334</ref> |

|||

Welsh code-switchers fall typically into one of three categories: the first category is people whose first language is Welsh and are not the most comfortable with English, the second is the inverse, English as a first language and a lack of confidence with Welsh, and the third consists of people whose first language could be either and display competence in both languages.<ref>{{Cite journal |doi=10.1515/ijsl.2009.004|title=Code switching and the future of the Welsh language|journal=International Journal of the Sociology of Language|issue=195|year=2009|last1=Deuchar|first1=Margaret|last2=Davies|first2=Peredur|s2cid=145440479}}</ref> |

|||

Welsh and English share congruence, meaning that there is enough overlap in their structure to make them compatible for code-switching. In studies of Welsh English code-switching, Welsh frequently acts as the matrix language with English words or phrases mixed in. A typical example of this usage would look like ''dw i’n love-io soaps'', which translates to "I love soaps".<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

==Influence outside Wales== |

|||

While other British English accents have affected the accents of English in Wales, influence has moved in both directions. In particular, [[Scouse]] and [[Brummie]] (colloquial) accents have both had extensive Anglo-Welsh input through migration, although in the former case, the influence of [[Hiberno-English|Anglo-Irish]] is better known. |

|||

In a study conducted by Margaret Deuchar in 2005 on Welsh-English code-switching, 90 per cent of tested sentences were found to be congruent with the Matrix Language Format, or MLF, classifying Welsh English as a classic case of code-switching.<ref name=":1" /> This case is identifiable as the matrix language was identifiable, the majority of clauses in a sentence that uses code-switching must be identifiable and distinct, and the sentence takes the structure of the matrix language in respect to things such as subject verb order and modifiers.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|date=2006-11-01|title=Welsh-English code-switching and the Matrix Language Frame model|journal=Lingua|language=en|volume=116|issue=11|pages=1986–2011|doi=10.1016/j.lingua.2004.10.001|issn=0024-3841|last1=Deuchar|first1=Margaret}}</ref> |

|||

==History of the English language in Wales== |

|||

The presence of English in Wales intensified on the passing of the [[Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542|Laws in Wales Acts of 1535–1542]], the [[Statute law|statutes]] having promoted the dominance of English in Wales; this, coupled with the [[Dissolution of the Monasteries|closure of the monasteries]], which closed down many centres of Welsh education, led to decline in the use of the Welsh language. |

|||

The decline of Welsh and the ascendancy of English was intensified further during the [[Industrial Revolution]], when many Welsh speakers moved to England to find work and the recently developed [[Mining in the United Kingdom|mining]] and [[smelting]] industries came to be manned by Anglophones. [[David Crystal]], who grew up in [[Holyhead]], claims that the continuing dominance of English in Wales is little different from its spread elsewhere in the world.{{sfnp|Crystal|2003|p=334}} The decline in the use of the Welsh language is also associated with the preference in the communities for English to be used in schools and to discourage everyday use of the [[Welsh language]] in them, including by the use of the [[Welsh Not]] in some schools in the 18th and 19th centuries.<ref name="BBC not">{{cite web|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/wales/history/sites/themes/society/language_education.shtml|title=Welsh and 19th century education|publisher=BBC|access-date=30 October 2019}}</ref> |

|||

==Literature== |

==Literature== |

||

{{main|Welsh literature in English}} |

{{main|Welsh literature in English}} |

||

[[File:Dylan |

[[File:Dylan Thomas’ writing shed in Laugharne (17086083038).jpg|right|thumb|[[Dylan Thomas]]' writing shed at the [[Dylan Thomas Boathouse|Boathouse]], [[Laugharne]]]] |

||

"Anglo-Welsh literature" and "Welsh writing in English" are terms used to describe works written in the English language by Welsh writers. It has been recognised as a distinctive entity only since the 20th century. |

"Anglo-Welsh literature" and "Welsh writing in English" are terms used to describe works written in the English language by Welsh writers. It has been recognised as a distinctive entity only since the 20th century.{{sfnp|Garlick|1970}} The need for a separate identity for this kind of writing arose because of the parallel development of modern [[Welsh-language literature]]; as such it is perhaps the youngest branch of English-language literature in the British Isles. |

||

While [[Raymond Garlick]] discovered sixty-nine Welsh men and women who wrote in English prior to the twentieth century, |

While [[Raymond Garlick]] discovered sixty-nine Welsh men and women who wrote in English prior to the twentieth century,{{sfnp|Garlick|1970}} Dafydd Johnston believes it is "debatable whether such writers belong to a recognisable Anglo-Welsh literature, as opposed to English literature in general".{{sfnp|Johnston|1994|p=91}} Well into the 19th century English was spoken by relatively few in Wales, and prior to the early 20th century there are only three major Welsh-born writers who wrote in the English language: [[George Herbert]] (1593–1633) from [[Montgomeryshire]], [[Henry Vaughan]] (1622–1695) from [[Brecknockshire]], and [[John Dyer]] (1699–1757) from [[Carmarthenshire]]. |

||

Welsh writing in English might be said to begin with the |

Welsh writing in English might be said to begin with the 15th-century bard [[Ieuan ap Hywel Swrdwal]] (?1430 - ?1480), whose ''Hymn to the Virgin'' was written at [[Oxford, England|Oxford]] in England in about 1470 and uses a Welsh poetic form, the ''[[awdl]]'', and [[Welsh orthography]]; for example: |

||

:O mighti ladi, owr leding - tw haf |

:O mighti ladi, owr leding - tw haf |

||

| Line 165: | Line 124: | ||

::I set a braents ws tw bring. |

::I set a braents ws tw bring. |

||

A rival claim for the first Welsh writer to use English creatively is made for the |

A rival claim for the first Welsh writer to use English creatively is made for the diplomat, soldier and poet [[John Clanvowe]] (1341–1391).{{citation needed|date=February 2020}} |

||

The influence of Welsh English can be seen in ''[[My People (story collection)|My People]]'' by [[Caradoc Evans]], which uses it in dialogue (but not narrative); ''[[Under |

The influence of Welsh English can be seen in the 1915 short story collection ''[[My People (story collection)|My People]]'' by [[Caradoc Evans]], which uses it in dialogue (but not narrative); ''[[Under Milk Wood]]'' (1954) by [[Dylan Thomas]], originally a radio play; and [[Niall Griffiths]] whose gritty realist pieces are mostly written in Welsh English. |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

*[[Cardiff |

* [[Cardiff English]] |

||

* [[Abercraf English]] |

|||

* [[Gower dialect]] |

|||

* [[Port Talbot English]] |

|||

* [[Welsh literature in English]] |

* [[Welsh literature in English]] |

||

*[[Regional accents of English speakers]] |

* [[Regional accents of English speakers]] |

||

* [[Gallo language|Gallo]] (Brittany) |

* [[Gallo language|Gallo]] (Brittany) |

||

* [[Scots language]] |

* [[Scots language]] |

||

Other English dialects heavily influenced by Celtic languages |

Other English dialects heavily influenced by Celtic languages |

||

* [[ |

* [[Bungi dialect]] |

||

* [[ |

* [[Cornish dialect]] |

||

* [[Bungi creole]] |

|||

* [[Hiberno-English]] |

* [[Hiberno-English]] |

||

* [[Highland English]] (and [[Scottish English]]) |

* [[Highland English]] (and [[Scottish English]]) |

||

* [[Manx English]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 187: | Line 149: | ||

==Bibliography== |

==Bibliography== |

||

{{refbegin}} |

|||

*{{Citation |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

|last=Connolly |

|||

|first=John H. |

|||

|editor-last1=Coupland |

|||

|editor-first1=Nikolas |

|||

|editor-last2=Thomas |

|||

|editor-first2=Alan Richard |

|||

|year=1990 |

|||

|title=English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change |

|||

|chapter=Port Talbot English |

|||

|publisher=Multilingual Matters Ltd. |

|||

|pages=121–129 |

|||

|isbn=978-1-85359-032-0 |

|||

|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tPwYt3gVbu4C |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{Citation |

|||

|last=Coupland |

|last=Coupland |

||

|first=Nikolas |

|first=Nikolas |

||

|year=1988 |

|||

|title=Dialect in Use: Sociolinguistic Variation in Cardiff English |

|||

|publisher=University of Wales Press |

|||

|isbn=0-70830-958-5 |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=W8kmAAAAMAAJ |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

|editor-last1=Coupland |

|||

|editor-first1=Nikolas |

|||

|editor-last2=Thomas |

|||

|editor-first2=Alan R. |

|||

|year=1990 |

|year=1990 |

||

|title=English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change |

|title=English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change |

||

|publisher=Multilingual Matters Ltd. |

|||

|isbn=1-85359-032-0 |

|||

|isbn=978-1-85359-032-0 |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tPwYt3gVbu4C |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{citation |

|||

|last=Crystal |

|||

|first=David |

|||

|author-link=David Crystal |

|||

|date=4 August 2003 |

|||

|title=The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language Second Edition |

|||

|publisher=Cambridge University Press |

|||

|isbn=9780521530330 |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Kh_RZhvHk0YC |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

|last=Johnston |

|||

|first=Dafydd |

|||

|year=1994 |

|||

|title=A Pocket Guide to the Literature of Wales |

|||

|publisher=University of Wales Press |

|||

|location=Cardiff |

|||

|isbn=978-0708312650 |

|||

|url-access=registration |

|||

|url=https://archive.org/details/literatureofwale0000john |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

|last=Garlick |

|||

|first=Raymond |

|||

|author-link=Raymond Garlick |

|||

|year=1970 |

|||

|title=An introduction to Anglo-Welsh literature |

|||

|contribution=Welsh Arts Council |

|||

|publisher=University of Wales Press |

|||

|issn=0141-5050 |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Aa0wvgAACAAJ |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{Accents of English|377–393|hide1=y|hide3=y|mode=cs2}} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

{{refbegin}} |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

|last=Penhallurick |

|||

|first=Robert |

|||

|editor-last=Schneider |

|||

|editor-first=Edgar W. |

|||

|editor2-last=Burridge |

|||

|editor2-first=Kate |

|||

|editor3-last=Kortmann |

|||

|editor3-first=Bernd |

|||

|editor4-last=Mesthrie |

|||

|editor4-first=Rajend |

|||

|editor5-last=Upton |

|||

|editor5-first=Clive |

|||

|year=2004 |

|||

|title=A handbook of varieties of English, Vol. 1: Phonology |

|||

|chapter=Welsh English: phonology |

|||

|publisher=Mouton de Gruyter |

|||

|pages=98–112 |

|||

|isbn=978-3-11-017532-5 |

|||

|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Dptsvykgk3IC |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{citation |

|||

|last=Podhovnik |

|||

|first=Edith |

|||

|year=2010 |

|||

|title=Age and Accent - Changes in a Southern Welsh English Accent |

|||

|journal=Research in Language |

|||

|volume=8 |

|||

|issue=2010 |

|||

|pages=1–18 |

|||

|issn=2083-4616 |

|||

|doi=10.2478/v10015-010-0006-5 |

|||

|hdl=11089/9569 |

|||

|s2cid=145409227 |

|||

|url=http://www.degruyter.com/dg/viewarticle.fullcontentlink:pdfeventlink/$002fj$002frela.2010.8.issue-0$002fv10015-010-0006-5$002fv10015-010-0006-5.pdf?t:ac=j$002frela.2010.8.issue-0$002fv10015-010-0006-5$002fv10015-010-0006-5.xml |

|||

|hdl-access=free |

|||

|access-date=25 August 2015 |

|||

|archive-date=23 September 2015 |

|||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150923213616/http://www.degruyter.com/dg/viewarticle.fullcontentlink:pdfeventlink/$002fj$002frela.2010.8.issue-0$002fv10015-010-0006-5$002fv10015-010-0006-5.pdf?t:ac=j$002frela.2010.8.issue-0$002fv10015-010-0006-5$002fv10015-010-0006-5.xml |

|||

|url-status=dead |

|||

}} |

|||

*Parry, David, ''A Grammar and Glossary of the Conservative Anglo-Welsh Dialects of Rural Wales'', The National Centre for English Cultural Tradition: [https://archive.org/details/start-of-survey-of-anglo-welsh-dialects/ introduction] and [https://archive.org/details/ggcawdrw-phonology phonology] available at the Internet Archive. |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

*[http://www.bl.uk/soundsfamiliar Sounds Familiar?]{{spaced ndash}}Listen to examples of regional accents and dialects from across the UK on the British Library's 'Sounds Familiar' website |

*[http://www.bl.uk/soundsfamiliar Sounds Familiar?]{{spaced ndash}}Listen to examples of regional accents and dialects from across the UK on the British Library's 'Sounds Familiar' website |

||

* [http://www.talktidy.com Talk Tidy] : John Edwards, Author of books and CDs on the subject "Wenglish". |

* [http://www.talktidy.com Talk Tidy] : John Edwards, Author of books and CDs on the subject "Wenglish". |

||

* [http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/wal/Thoughts.html Some thoughts and notes on the English of south Wales] : D Parry-Jones, National Library of Wales journal 1974 Winter, volume XVIII/4 |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20050325093722/http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/wal/Thoughts.html Some thoughts and notes on the English of south Wales] : D Parry-Jones, National Library of Wales journal 1974 Winter, volume XVIII/4 |

||

* [http://www.ku.edu/~idea/europe/wales/wales.htm Samples of Welsh Dialect(s)/Accent(s)] |

* [http://www.ku.edu/~idea/europe/wales/wales.htm Samples of Welsh Dialect(s)/Accent(s)] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060626174623/http://www.ku.edu/~idea/europe/wales/wales.htm |date=26 June 2006 }} |

||

*[ |

*[https://books.google.com/books?id=tPwYt3gVbu4C&dq=%22welsh+English%22+transcription&pg=PA134 Welsh vowels] |

||

* [http://parallel.cymru/?p=4224 David Jandrell: Introducing The Welsh Valleys Phrasebook] |

|||

{{English dialects by continent}} |

{{Languages in Wales}}{{English dialects by continent}} |

||

[[Category:Welsh English| ]] |

|||

[[Category:British English|Welsh English]] |

[[Category:British English|Welsh English]] |

||

[[Category:Languages of Wales]] |

[[Category:Languages of Wales]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Dialects of English]] |

||

Latest revision as of 17:08, 23 December 2024

| Welsh English | |

|---|---|

| Native to | United Kingdom |

| Region | Wales |

| Ethnicity | Welsh people |

Native speakers | (undated figure of 2.5 million[citation needed]) |

Early forms | |

| Dialects | |

| Latin (English alphabet) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

| Part of a series on the |

| English language |

|---|

| Topics |

| Advanced topics |

| Phonology |

| Dialects |

|

| Teaching |

Welsh English (Welsh: Saesneg Gymreig) comprises the dialects of English spoken by Welsh people. The dialects are significantly influenced by Welsh grammar and often include words derived from Welsh. In addition to the distinctive words and grammar, a variety of accents are found across Wales, including those of North Wales, the Cardiff dialect, the South Wales Valleys and West Wales.

While other accents and dialects from England have affected those of English in Wales, especially in the east of the country, influence has moved in both directions, those in the west have been more heavily influenced by the Welsh language, those in north-east Wales and parts of the North Wales coastline it have been influenced by Northwestern English, and those in the mid-east and the south-east Wales (composing the South Wales Valleys) have been influenced by West Country and West Midlands English,[1][2] and the one from Cardiff have been influenced by Midlands, West Country, and Hiberno-English.[3]

A colloquial portmanteau word for Welsh English is Wenglish. It has been in use since 1985.[4]

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Wales |

|---|

|

| People |

| Art |

Pronunciation

[edit]Vowels

[edit]Short monophthongs

[edit]- The vowel of cat /æ/ is pronounced either as an open front unrounded vowel [a][5][6] or a more central near-open front unrounded vowel [æ̈].[7] In Cardiff, bag is pronounced with a long vowel [aː].[8] In Mid-Wales, a pronunciation resembling its New Zealand and South African analogue is sometimes heard, i.e. trap is pronounced /trɛp/.[9]

- The vowel of end /ɛ/ is pronounced close to cardinal vowel [ɛ], similar to modern RP.[7]

- In Cardiff, the vowel of "kit" /ɪ/ sounds slightly closer to the schwa sound of above, an advanced close-mid central unrounded vowel [ɘ̟].[7]

- The vowel of "bus" /ʌ/ is usually pronounced [ɜ~ə][10][11] and is encountered as a hypercorrection in northern areas for foot.[9] It is sometimes manifested in border areas of north and mid Wales as an open front unrounded vowel /a/. It also manifests as a near-close near-back rounded vowel /ʊ/ without the foot–strut split in parts of North Wales it influenced the Cheshire and Scouse accents,[9] and to a lesser extent in south Pembrokeshire.[12]

- The schwa tends to be supplanted by an /ɛ/ in final closed syllables, e.g. brightest /ˈbrəitɛst/. The uncertainty over which vowel to use often leads to 'hypercorrections' involving the schwa, e.g. programme is often pronounced /ˈproːɡrəm/.[8]

Long monophthongs

[edit]

- The trap-bath split is variable in Welsh English, especially among social status. In some varieties such as Cardiff English, words like ask, bath, laugh, master and rather are usually pronounced with PALM while words like answer, castle, dance and nasty are normally pronounced with TRAP. On the other hand, the split may be completely absent in other varieties like Abercraf English.[14]

- The vowel of car is often pronounced as an open central unrounded vowel [ɑ̈][15] and more often as a long open front unrounded vowel /aː/.[9]

- In broader varieties, particularly in Cardiff, the vowel of bird is similar to South African and New Zealand, i.e. a mid front rounded vowel [ø̞ː].[16]

- Most other long monophthongs are similar to that of Received Pronunciation, but words with the RP /əʊ/ are sometimes pronounced as [oː] and the RP /eɪ/ as [eː]. An example that illustrates this tendency is the Abercrave pronunciation of play-place [ˈpleɪˌpleːs].[17]

- In northern varieties, /əʊ/ as in coat and /ɔː/ as in caught/court may be merged into /ɔː/ (phonetically [oː]).[8]

Diphthongs

[edit]- Fronting diphthongs tend to resemble Received Pronunciation, apart from the vowel of bite that has a more centralised onset [æ̈ɪ].[17]

- Backing diphthongs are more varied:[17]

- The vowel of low in RP, other than being rendered as a monophthong, like described above, is often pronounced as [oʊ̝].

- The word town is pronounced with a near-open central onset [ɐʊ̝].

- Welsh English is one of few dialects where the Late Middle English diphthong /iu̯/ never became /juː/, remaining as a falling diphthong [ɪʊ̯]. Thus you /juː/, yew /jɪʊ̯/, and ewe /ɪʊ̯/ are not homophones in Welsh English. As such yod-dropping never occurs: distinctions are made between choose /t͡ʃuːz/ and chews /t͡ʃɪʊ̯s/, through /θruː/ and threw /θrɪʊ̯/, which most other English varieties do not have.

Consonants

[edit]- Most Welsh accents pronounce /r/ as an alveolar flap [ɾ] (a 'flapped r'), similar to Scottish English and some Northern English and South African accents, in place of an approximant [ɹ] like in most accents in England[18] while an alveolar trill [r] may also be used under the influence of Welsh.[19]

- Welsh English is mostly non-rhotic, however variable rhoticity can be found in accents influenced by Welsh, especially northern varieties. Additionally, while Port Talbot English is mostly non-rhotic like other varieties of Welsh English, some speakers may supplant the front vowel of bird with /ɚ/, like in many varieties of North American English.[20]

- H-dropping is common in many Welsh accents, especially southern varieties like Cardiff English,[21] but is absent in northern and western varieties influenced by Welsh.[22]

- Some gemination between vowels is often encountered, e.g. money is pronounced [ˈmɜn.niː].[23]

- As Welsh lacks the letter Z and the voiced alveolar fricative /z/, some first-language Welsh speakers replace it with the voiceless alveolar fricative /s/ for words like cheese and thousand, while pens (/pɛnz/) and pence merge into /pɛns/, especially in north-west, west and south-west Wales.[23][24]

- In northern varieties influenced by Welsh, chin (/tʃɪn/) and gin may also merge into /dʒɪn/.[23]

- In the north-east, under influence of such accents as Scouse, ng-coalescence does not take place, so sing is pronounced /sɪŋɡ/.[25]

- Also in northern accents, /l/ is frequently strongly velarised [ɫː]. In much of the south-east, clear and dark L alternate much like they do in RP.[20]

- The consonants are generally the same as RP but Welsh consonants like /ɬ/ and /x/ (phonetically [χ]) are encountered in loan words such as Llangefni and Harlech.[23]

Distinctive vocabulary and grammar

[edit]Aside from lexical borrowings from Welsh like bach (little, wee), eisteddfod, nain and taid (grandmother and grandfather respectively), there exist distinctive grammatical conventions in vernacular Welsh English. Examples of this include the use by some speakers of the tag question isn't it? regardless of the form of the preceding statement and the placement of the subject and the verb after the predicate for emphasis, e.g. Fed up, I am or Running on Friday, he is.[23]

In South Wales the word where may often be expanded to where to, as in the question, "Where to is your Mam?". The word butty (Welsh: byti) is used to mean "friend" or "mate".[26]

There is no standard variety of English that is specific to Wales, but such features are readily recognised by Anglophones from the rest of the UK as being from Wales, including the phrase look you which is a translation of a Welsh language tag.[23]

The word tidy is among "the most over-worked Wenglish words". It carries a number of meanings include - great or excellent, or a large quantity. A tidy swill is a wash that includes, at the least, the hands and the face.[27]

Code-switching

[edit]As Wales has become increasingly more anglicised, code-switching has become increasingly more common.[28][29]

Examples

[edit]Welsh code-switchers fall typically into one of three categories: the first category is people whose first language is Welsh and are not the most comfortable with English, the second is the inverse, English as a first language and a lack of confidence with Welsh, and the third consists of people whose first language could be either and display competence in both languages.[30]

Welsh and English share congruence, meaning that there is enough overlap in their structure to make them compatible for code-switching. In studies of Welsh English code-switching, Welsh frequently acts as the matrix language with English words or phrases mixed in. A typical example of this usage would look like dw i’n love-io soaps, which translates to "I love soaps".[29]

In a study conducted by Margaret Deuchar in 2005 on Welsh-English code-switching, 90 per cent of tested sentences were found to be congruent with the Matrix Language Format, or MLF, classifying Welsh English as a classic case of code-switching.[29] This case is identifiable as the matrix language was identifiable, the majority of clauses in a sentence that uses code-switching must be identifiable and distinct, and the sentence takes the structure of the matrix language in respect to things such as subject verb order and modifiers.[28]

History of the English language in Wales

[edit]The presence of English in Wales intensified on the passing of the Laws in Wales Acts of 1535–1542, the statutes having promoted the dominance of English in Wales; this, coupled with the closure of the monasteries, which closed down many centres of Welsh education, led to decline in the use of the Welsh language.

The decline of Welsh and the ascendancy of English was intensified further during the Industrial Revolution, when many Welsh speakers moved to England to find work and the recently developed mining and smelting industries came to be manned by Anglophones. David Crystal, who grew up in Holyhead, claims that the continuing dominance of English in Wales is little different from its spread elsewhere in the world.[31] The decline in the use of the Welsh language is also associated with the preference in the communities for English to be used in schools and to discourage everyday use of the Welsh language in them, including by the use of the Welsh Not in some schools in the 18th and 19th centuries.[32]

Literature

[edit]

"Anglo-Welsh literature" and "Welsh writing in English" are terms used to describe works written in the English language by Welsh writers. It has been recognised as a distinctive entity only since the 20th century.[33] The need for a separate identity for this kind of writing arose because of the parallel development of modern Welsh-language literature; as such it is perhaps the youngest branch of English-language literature in the British Isles.

While Raymond Garlick discovered sixty-nine Welsh men and women who wrote in English prior to the twentieth century,[33] Dafydd Johnston believes it is "debatable whether such writers belong to a recognisable Anglo-Welsh literature, as opposed to English literature in general".[34] Well into the 19th century English was spoken by relatively few in Wales, and prior to the early 20th century there are only three major Welsh-born writers who wrote in the English language: George Herbert (1593–1633) from Montgomeryshire, Henry Vaughan (1622–1695) from Brecknockshire, and John Dyer (1699–1757) from Carmarthenshire.

Welsh writing in English might be said to begin with the 15th-century bard Ieuan ap Hywel Swrdwal (?1430 - ?1480), whose Hymn to the Virgin was written at Oxford in England in about 1470 and uses a Welsh poetic form, the awdl, and Welsh orthography; for example:

- O mighti ladi, owr leding - tw haf

- At hefn owr abeiding:

- Yntw ddy ffast eferlasting

- I set a braents ws tw bring.

A rival claim for the first Welsh writer to use English creatively is made for the diplomat, soldier and poet John Clanvowe (1341–1391).[citation needed]

The influence of Welsh English can be seen in the 1915 short story collection My People by Caradoc Evans, which uses it in dialogue (but not narrative); Under Milk Wood (1954) by Dylan Thomas, originally a radio play; and Niall Griffiths whose gritty realist pieces are mostly written in Welsh English.

See also

[edit]- Cardiff English

- Abercraf English

- Gower dialect

- Port Talbot English

- Welsh literature in English

- Regional accents of English speakers

- Gallo (Brittany)

- Scots language

Other English dialects heavily influenced by Celtic languages

References

[edit]- ^ Rhodri Clark (27 March 2007). "Revealed: the wide range of Welsh accents". Wales Online. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ "Secret behind our Welsh accents discovered". Wales Online. 7 June 2006. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ Carney, Rachel (16 December 2010). "A Cardiff Story: A migrant city". The Guardian Cardiff. Cardiff. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Lambert, James (2018). "A multitude of "lishes"". English World-Wide. A Journal of Varieties of English. 39: 1–33. doi:10.1075/eww.00001.lam.

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 380, 384–385.

- ^ Connolly (1990), pp. 122, 125.

- ^ a b c Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan Richard (1990a). English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 9781853590313. Retrieved 22 February 2015.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Wells (1982), pp. 384, 387, 390

- ^ a b c d Schneider, Edgar Werner; Kortmann, Bernd (2004). A Handbook of Varieties of English: CD-ROM. - Google Books. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Company KG. ISBN 9783110175325. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan Richard (1990a). English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 9781853590313. Retrieved 22 February 2015.[page needed]

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 380–381.

- ^ Trudgill, Peter (27 April 2019). "Wales's very own little England". The New European. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Coupland & Thomas (1990), p. 95.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 387.

- ^ Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan Richard (1990a). English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 9781853590313. Retrieved 22 February 2015.[page needed]

- ^ Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan Richard (1990a). English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 9781853590313. Retrieved 22 February 2015.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan Richard (1990a). English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 9781853590313. Retrieved 22 February 2015.[page needed]

- ^ Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan Richard (1990a). English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 9781853590313. Retrieved 22 February 2015.[page needed]

- ^ Peter Garrett; Nikolas Coupland; Angie Williams, eds. (15 July 2003). Investigating Language Attitudes: Social Meanings of Dialect, Ethnicity and Performance. University of Wales Press. p. 73. ISBN 9781783162086. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ a b Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan Richard (1990a). English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change - Google Books. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 9781853590313. Retrieved 22 February 2015.[page needed]

- ^ Coupland (1988), p. 29.

- ^ Approaches to the Study of Sound Structure and Speech: Interdisciplinary Work in Honour of Katarzyna Dziubalska-Kołaczyk. Magdalena Wrembel, Agnieszka Kiełkiewicz-Janowiak and Piotr Gąsiorowski. 21 October 2019. pp. 1–398. ISBN 9780429321757.

- ^ a b c d e f Crystal (2003), p. 335.

- ^ The British Isles. Bernd Kortmann and Clive Upton. 10 December 2008. ISBN 9783110208399. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 390.

- ^ "Why butty rarely leaves Wales". Wales Online. 2 October 2006 [updated: 30 Mar 2013]. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ Edwards, John (1985). Talk Tidy. Bridgend, Wales, UK: D Brown & Sons Ltd. p. 39. ISBN 0905928458.

- ^ a b Deuchar, Margaret (1 November 2006). "Welsh-English code-switching and the Matrix Language Frame model". Lingua. 116 (11): 1986–2011. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2004.10.001. ISSN 0024-3841.

- ^ a b c Deuchar, Margaret (December 2005). "Congruence and Welsh–English code-switching". Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 8 (3): 255–269. doi:10.1017/S1366728905002294. ISSN 1469-1841. S2CID 144548890.

- ^ Deuchar, Margaret; Davies, Peredur (2009). "Code switching and the future of the Welsh language". International Journal of the Sociology of Language (195). doi:10.1515/ijsl.2009.004. S2CID 145440479.

- ^ Crystal (2003), p. 334.

- ^ "Welsh and 19th century education". BBC. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ a b Garlick (1970).

- ^ Johnston (1994), p. 91.

Bibliography

[edit]- Connolly, John H. (1990), "Port Talbot English", in Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan Richard (eds.), English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change, Multilingual Matters Ltd., pp. 121–129, ISBN 978-1-85359-032-0

- Coupland, Nikolas (1988), Dialect in Use: Sociolinguistic Variation in Cardiff English, University of Wales Press, ISBN 0-70830-958-5

- Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan R., eds. (1990), English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change, Multilingual Matters Ltd., ISBN 978-1-85359-032-0

- Crystal, David (4 August 2003), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language Second Edition, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521530330

- Johnston, Dafydd (1994), A Pocket Guide to the Literature of Wales, Cardiff: University of Wales Press, ISBN 978-0708312650

- Garlick, Raymond (1970), "Welsh Arts Council", An introduction to Anglo-Welsh literature, University of Wales Press, ISSN 0141-5050

- Wells, John C. (1982), Accents of English, Vol. 2: The British Isles (pp. i–xx, 279–466), Cambridge University Press, pp. 377–393, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511611759, ISBN 0-52128540-2

Further reading

[edit]- Penhallurick, Robert (2004), "Welsh English: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.), A handbook of varieties of English, Vol. 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 98–112, ISBN 978-3-11-017532-5

- Podhovnik, Edith (2010), "Age and Accent - Changes in a Southern Welsh English Accent" (PDF), Research in Language, 8 (2010): 1–18, doi:10.2478/v10015-010-0006-5, hdl:11089/9569, ISSN 2083-4616, S2CID 145409227, archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015, retrieved 25 August 2015

- Parry, David, A Grammar and Glossary of the Conservative Anglo-Welsh Dialects of Rural Wales, The National Centre for English Cultural Tradition: introduction and phonology available at the Internet Archive.

External links

[edit]- Sounds Familiar? – Listen to examples of regional accents and dialects from across the UK on the British Library's 'Sounds Familiar' website

- Talk Tidy : John Edwards, Author of books and CDs on the subject "Wenglish".

- Some thoughts and notes on the English of south Wales : D Parry-Jones, National Library of Wales journal 1974 Winter, volume XVIII/4

- Samples of Welsh Dialect(s)/Accent(s) Archived 26 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Welsh vowels

- David Jandrell: Introducing The Welsh Valleys Phrasebook