Melanoma: Difference between revisions

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Added pmid. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Anas1712 | #UCB_toolbar |

|||

| (864 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Skin cancer originating in melanocytes}} |

|||

{{Infobox disease |

|||

{{Distinguish|Multiple myeloma}} |

|||

| Name = Melanoma |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=August 2023}} |

|||

| Image = Melanoma.jpg |

|||

{{cs1 config |name-list-style=vanc |display-authors=6}} |

|||

| Caption = A melanoma |

|||

{{Infobox medical condition (new) |

|||

| Width = 250 |

|||

| name = Melanoma |

|||

| synonyms = Malignant melanoma |

|||

| image = Melanoma.jpg |

|||

| alt = A back irregular Tumor {{convert|2.5|cm|in|0|abbr=on}} by {{convert|1.5|cm|in|1|abbr=on}} |

|||

| pronounce = {{IPAc-en|audio=En-melanoma.oga|ˌ|m|ɛ|l|ə|ˈ|n|oʊ|m|ə}} |

|||

| field = [[Oncology]] and [[dermatology]] |

| field = [[Oncology]] and [[dermatology]] |

||

| symptoms = [[Nevus|Mole]] that is increasing in size, has irregular edges, change in color, itchiness, or [[ulcer (dermatology)|skin breakdown]].<ref name=NCI2015/> |

|||

| DiseasesDB = 7947 |

|||

| complications = |

|||

| ICD10 = {{ICD10|C|43||c|43}} |

|||

| onset = |

|||

| ICD9 = {{ICD9|172.9}} |

|||

| duration = |

|||

| ICDO = {{ICDO|8720|3}} |

|||

| causes = [[Ultraviolet light]] (Sun, [[tanning lamp|tanning devices]])<ref name=WCR2014/> |

|||

| OMIM = 155600 |

|||

| risks = Family history, many moles, [[immunosuppression|poor immune function]]<ref name=NCI2015/> |

|||

| MedlinePlus = 000850 |

|||

| diagnosis = [[Tissue biopsy]]<ref name=NCI2015/> |

|||

| eMedicineSubj = derm |

|||

| differential = [[Seborrheic keratosis]], [[lentigo]], [[blue nevus]], [[dermatofibroma]]<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Goldstein BG, Goldstein AO | title = Diagnosis and management of malignant melanoma | journal = American Family Physician | volume = 63 | issue = 7 | pages = 1359–68, 1374 | date = April 2001 | pmid = 11310650 }}</ref> |

|||

| eMedicineTopic = 257 |

|||

| prevention = [[Sunscreen]], avoiding UV light<ref name=WCR2014/> |

|||

| eMedicine_mult = {{eMedicine2|med|1386}} {{eMedicine2|ent|27}} {{eMedicine2|plastic|456}} |

|||

| treatment = Surgery<ref name=NCI2015/> |

|||

| MeshID = D008545 |

|||

| medication = |

|||

|BioVex |

|||

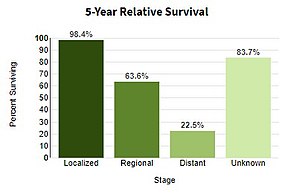

| prognosis = [[Five-year survival rates]] in US 99% (localized), 25% (disseminated)<ref name=SEER2019/> |

|||

| frequency = 3.1 million (2015)<!-- prevalence --><ref name=GBD2015Pre/> |

|||

| deaths = 59,800 (2015)<ref name=GBD2015De/> |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

<!-- Definition and symptoms --> |

|||

'''Melanoma''' ({{IPAc-en|audio=melanoma-pronunciation.ogg|ˌ|m|ɛ|l|ə|ˈ|n|oʊ|m|ə}}; from [[Greek language|Greek]] μέλας ''melas'', "dark")<ref>[http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3Dme%2Flas μέλας], Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, ''A Greek-English Lexicon'', on Perseus</ref> is a type of [[skin cancer]] which forms from [[melanocyte]]s (pigment-containing cells in the skin).<ref name="melanoma2012">{{cite journal|title=Drugs in Clinical Development for Melanoma|journal=Pharmaceutical Medicine|date=23 December 2012|volume=26|issue=3|pages=171–183|doi=10.1007/BF03262391|url=http://adisonline.com/pharmaceuticalmedicine/Abstract/2012/26030/Drugs_in_Clinical_Development_for_Melanoma__.4.aspx}}</ref> |

|||

'''Melanoma''' is the most dangerous type of [[skin cancer]]; it develops from the [[melanin]]-producing cells known as [[melanocyte]]s.<ref name="NCI2015">{{cite web|title=Melanoma Treatment – for health professionals |url=http://www.cancer.gov/types/skin/hp/melanoma-treatment-pdq|website=National Cancer Institute|access-date=30 June 2015|date=26 June 2015|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150704213842/http://www.cancer.gov/types/skin/hp/melanoma-treatment-pdq|archive-date=4 July 2015}}</ref> It typically occurs in the skin, but may rarely occur in the mouth, intestines, or eye ([[uveal melanoma]]).<ref name=NCI2015/><ref name=WCR2014/> |

|||

In women, melanomas most commonly occur on the legs; while in men, on the back.<ref name=WCR2014/> Melanoma is frequently referred to as '''malignant melanoma'''. However, the medical community stresses that there is no such thing as a 'benign melanoma' and recommends that the term 'malignant melanoma' should be avoided as redundant.<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Schwartzman RM, Orkin M |title=A Comparative Study of Diseases of Dog and Man |date=1962 |publisher=Thomas |location=Springfield, IL |page=85 |quote=The term 'melanoma' in human medicine indicates a malignant growth; the prefix 'malignant' is redundant.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Bobonich M, Nolen ME |title=Dermatology for Advanced Practice Clinicians |date=2015 |publisher=Wolters Kluwer |location=Philadelphia |page=106 |quote=The term malignant melanoma is becoming obsolete because the word 'malignant' is redundant as there are no benign melanomas.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Farlex Partner Medical Dictionary |date=2012 |url=https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Melanoma%2c+Malignant |access-date=4 March 2021 |quote=Avoid the redundant phrase malignant melanoma. |archive-date=10 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220610135029/https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Melanoma%2c+Malignant |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

<!-- Cause --> |

|||

In women, the most common site is the legs, and melanomas in men are most common on the back.<ref>[http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/skin/incidence/ Cancer Research UK statistical information team 2010].</ref> It is particularly common among [[White people|Caucasians]], especially [[northern Europe]]ans and [[northwestern Europe]]ans, living in sunny climates. There are higher rates in [[Oceania]], [[North America]], [[Europe]], Southern Africa, and [[Latin America]].<ref name="globalca2001">{{Cite journal| author = Parkin D, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P | title = Global cancer statistics, 2002 | journal = CA Cancer J Clin | volume = 55 | issue = 2 | pages = 74–108 | year = 2005| pmid = 15761078 | doi = 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74 |url=http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74/full}}</ref> This geographic pattern reflects the primary cause, [[ultraviolet light]] (UV) exposure<ref>{{cite journal |author=Kanavy HE, Gerstenblith MR |title=Ultraviolet radiation and melanoma |journal=Semin Cutan Med Surg |volume=30 |issue=4 |pages=222–8 |date=December 2011 |pmid=22123420 |doi=10.1016/j.sder.2011.08.003 |url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1085-5629(11)00130-1}}</ref> in conjunction with the amount of skin pigmentation in the population.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. |title=Cancer statistics, 2008 |journal=CA Cancer J Clin |volume=58 |issue=2 |pages=71–96 |year=2008 |pmid=18287387 |doi=10.3322/CA.2007.0010 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Jost |first=L.M. |title=ESMO Minimum Clinical Recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of cutaneous malignant melanoma |journal=Annals of Oncology |volume=14 |issue=7 |pages=1012–1013 |date=July 2003 |pmid=12853340 |doi=10.1093/annonc/mdg294 }}</ref> Melanocytes produce the dark pigment, [[melanin]], which is responsible for the color of skin. These cells predominantly occur in skin, but are also found in other parts of the body, including the [[bowel]] and the [[human eye|eye]] (see [[uveal melanoma]]). Melanoma can originate in any part of the body that contains melanocytes. |

|||

About 25% of melanomas develop from [[nevus|moles]].<ref name=WCR2014/> Changes in a mole that can indicate melanoma include increase{{mdash}}especially rapid increase{{mdash}}in size, irregular edges, change in color, itchiness, or [[nevus#Classification|skin breakdown]].<ref name=NCI2015/> |

|||

<!-- Treatment and Prognosis --> |

|||

The treatment includes surgical removal of the tumor. If melanoma is found early, while it is still small and thin, and if it is completely removed, then the chance of cure is high. The likelihood that the melanoma will come back or spread depends on how deeply it has gone into the layers of the skin. For melanomas that come back or spread, treatments include [[chemotherapy|chemo-]] and [[Cancer immunotherapy|immunotherapy]], or [[radiation therapy]]. [[Five year survival rates]] in the United States are on average 91%.<ref>{{cite web|title=SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Melanoma of the Skin|url=http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html|website=NCI|accessdate=18 June 2014}}</ref> |

|||

<!-- Cause and diagnosis --> |

|||

The primary cause of melanoma is [[ultraviolet light]] (UV) exposure in those with low levels of the [[human skin color|skin pigment]] [[melanin]].<ref name=WCR2014/><ref name="SunM"/> The UV light may be from the sun or other sources, such as [[tanning lamp|tanning devices]].<ref name=WCR2014/> Those with many moles, a history of affected family members, and [[immunosuppression|poor immune function]] are at greater risk.<ref name=NCI2015/> A number of rare [[genetic conditions]], such as [[xeroderma pigmentosum]], also increase the risk.<ref name=Az2014/> Diagnosis is by [[biopsy]] and analysis of any skin lesion that has signs of being potentially cancerous.<ref name=NCI2015/> |

|||

<!-- Prevention, treatment and prognosis --> |

|||

Avoiding UV light and using [[sunscreen]] in UV-bright sun conditions may prevent melanoma.<ref name=WCR2014/> Treatment typically is removal by surgery of the melanoma and the potentially affected adjacent tissue bordering the melanoma.<ref name=NCI2015/> In those with slightly larger cancers, nearby [[lymph nodes]] may be tested for spread ([[metastasis]]).<ref name=NCI2015/> Most people are cured if metastasis has not occurred.<ref name=NCI2015/> For those in whom melanoma has spread, [[Cancer immunotherapy|immunotherapy]], [[biologic therapy]], [[radiation therapy]], or [[chemotherapy]] may improve survival.<ref name=NCI2015/><ref name="Syn2017">{{cite journal | vauthors = Syn NL, Teng MW, Mok TS, Soo RA | title = De-novo and acquired resistance to immune checkpoint targeting | journal = The Lancet. Oncology | volume = 18 | issue = 12 | pages = e731–e741 | date = December 2017 | pmid = 29208439 | doi = 10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30607-1 }}</ref> With treatment, the [[five-year survival rates]] in the United States are 99% among those with localized disease, 65% when the disease has spread to lymph nodes, and 25% among those with distant spread.<ref name=SEER2019>{{cite web|title=SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Melanoma of the Skin|url=http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html|website=NCI|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140706134347/http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html|archive-date=6 July 2014}}</ref> The likelihood that melanoma will reoccur or spread depends on its [[Breslow's depth|thickness]], how fast the cells are dividing, and whether or not the overlying skin has broken down.<ref name=WCR2014/> |

|||

<!-- Epidemiology --> |

<!-- Epidemiology --> |

||

Melanoma is the most dangerous type of skin cancer.<ref name=WCR2014/> Globally, in 2012, it newly occurred in 232,000 people.<ref name=WCR2014/> In 2015, 3.1 million people had active disease, which resulted in 59,800 deaths.<ref name=GBD2015Pre>{{cite journal | title = Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 | journal = Lancet | volume = 388 | issue = 10053 | pages = 1545–1602 | date = October 2016 | pmid = 27733282 | pmc = 5055577 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6 | collaboration = GBD 2015 Disease Injury Incidence Prevalence Collaborators | vauthors = Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, Carter A, Casey DC, Charlson FJ, Chen AZ, Coggeshall M, Cornaby L, Dandona L, Dicker DJ, Dilegge T, Erskine HE, Ferrari AJ, Fitzmaurice C, Fleming T, Forouzanfar MH, Fullman N, Gething PW, Goldberg EM, Graetz N, Haagsma JA, Hay SI, Johnson CO, Kassebaum NJ, Kawashima T, Kemmer L }}</ref><ref name=GBD2015De>{{cite journal | title = Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 | journal = Lancet | volume = 388 | issue = 10053 | pages = 1459–1544 | date = October 2016 | pmid = 27733281 | pmc = 5388903 | doi = 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1 | collaboration = GBD 2015 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators | vauthors = Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, Casey DC, Charlson FJ, Chen AZ, Coates MM, Coggeshall M, Dandona L, Dicker DJ, Erskine HE, Ferrari AJ, Fitzmaurice C, Foreman K, Forouzanfar MH, Fraser MS, Fullman N, Gething PW, Goldberg EM, Graetz N, Haagsma JA, Hay SI, Huynh C, Johnson CO, Kassebaum NJ, Kinfu Y, Kulikoff XR }}</ref> Australia and New Zealand have the highest rates of melanoma in the world.<ref name=WCR2014/> High rates also occur in Northern Europe and North America, while it is less common in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.<ref name=WCR2014/> In the United States, melanoma occurs about 1.6 times more often in men than women.<ref>{{cite web |title=USCS Data Visualizations |url=https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/DataViz.html |website=gis.cdc.gov |quote=Need to select "melanoma" |access-date=7 March 2020 |archive-date=17 March 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200317210642/https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/DataViz.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Melanoma has become more common since the 1960s in areas mostly populated by [[people of European descent]].<ref name="WCR2014">{{cite book|title=World Cancer Report|date=2014|publisher=World Health Organization|isbn=978-92-832-0429-9|pages=Chapter 5.14|url=https://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/wcr/2003/WorldCancerReport.pdf|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140530232406/http://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/wcr/2003/WorldCancerReport.pdf|archive-date=30 May 2014}}</ref><ref name="Az2014">{{cite journal | vauthors = Azoury SC, Lange JR | title = Epidemiology, risk factors, prevention, and early detection of melanoma | journal = The Surgical Clinics of North America | volume = 94 | issue = 5 | pages = 945–62, vii | date = October 2014 | pmid = 25245960 | doi = 10.1016/j.suc.2014.07.013 }}</ref> |

|||

Melanoma is less common than other skin cancers. However, it is much more dangerous if it is not found in the early stages. It causes the majority (75%) of deaths related to skin cancer.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Jerant AF, Johnson JT, Sheridan CD, Caffrey TJ |title=Early detection and treatment of skin cancer |journal=Am Fam Physician |volume=62 |issue=2 |pages=357–68, 375–6, 381–2 |date=July 2000 |pmid=10929700 |url=http://www.aafp.org/afp/20000715/357.html }}</ref> Globally, in 2012, melanoma occurred in 232,000 people and resulted in 55,000 deaths.<ref name=WCR2014/> Australia and New Zealand have the highest rates of melanoma in the world.<ref name=WCR2014/> It has become more common in the last 20 years in areas that are mostly [[White people|Caucasian]].<ref name=WCR2014>{{cite book|title=World Cancer Report 2014.|date=2014|publisher=World Health Organization|isbn=9283204298|pages=Chapter 5.14}}</ref> |

|||

==Signs and symptoms== |

==Signs and symptoms== |

||

Early signs of melanoma are changes to the shape or color of existing [[ |

Early signs of melanoma are changes to the shape or color of existing [[mole (skin marking)|moles]] or, in the case of [[nodular melanoma]], the appearance of a new lump anywhere on the skin. At later stages, the mole may [[itch]], [[ulcer (dermatology)|ulcerate]], or bleed. Early signs of melanoma are summarized by the mnemonic "ABCDEEFG":<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/skin/basic_info/symptoms.htm|title=CDC - What Are the Symptoms of Skin Cancer?|date=26 June 2018|website=www.cdc.gov|language=en-us|access-date=1 February 2019|archive-date=7 December 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181207125444/https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/skin/basic_info/symptoms.htm|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Daniel Jensen J, Elewski BE | title = The ABCDEF Rule: Combining the "ABCDE Rule" and the "Ugly Duckling Sign" in an Effort to Improve Patient Self-Screening Examinations | journal = The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology | volume = 8 | issue = 2 | pages = 15 | date = February 2015 | pmid = 25741397 | pmc = 4345927 }}</ref> |

||

*'''A'''symmetry |

* '''A'''symmetry |

||

* '''B'''orders (irregular) |

* '''B'''orders (irregular with edges and corners) |

||

*'''C''' |

* '''C'''olour ([[Variegation (histology)|variegated]]) |

||

*'''D'''iameter (greater than {{convert|6|mm|2|abbr=on|lk=out}}, about the size of a pencil eraser) |

* '''D'''iameter (greater than {{convert|6|mm|2|abbr=on|lk=out}}, about the size of a pencil eraser) |

||

*'''E'''volving over time |

* '''E'''volving over time |

||

These classifications do not, however, apply to the most dangerous form of melanoma, nodular melanoma, which has its own classifications: |

|||

This classification does not apply to nodular melanoma, which has its own classifications:<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.molemap.co.nz/knowledge-centre/efg-nodular-melanomas|title=The EFG of Nodular Melanomas {{!}} MoleMap New Zealand|website=The EFG of Nodular Melanomas {{!}} MoleMap New Zealand|language=en-US|access-date=1 February 2019|archive-date=2 February 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190202041434/https://www.molemap.co.nz/knowledge-centre/efg-nodular-melanomas|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

*'''E'''levated above the skin surface |

|||

*''' |

* '''E'''levated above the skin surface |

||

*''' |

* '''F'''irm to the touch |

||

* '''G'''rowing |

|||

Metastatic melanoma may cause nonspecific [[paraneoplastic syndrome|paraneoplastic symptoms]], including loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting and fatigue. [[Metastasis]] of early melanoma is possible, but relatively rare: less than a fifth of melanomas diagnosed early become metastatic. [[brain metastasis|Brain metastases]] are particularly common in patients with metastatic melanoma.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Fiddler IJ |title=Melanoma metastasis |journal=Cancer Control |volume=2 |issue=5 |pages=398–404 |date=October 1995 |pmid=10862180 |url=http://www.moffitt.usf.edu/pubs/ccj/v2n5/article3.html}}</ref> It can also spread to the liver, bones, abdomen or distant lymph nodes. |

|||

Metastatic melanoma may cause nonspecific [[paraneoplastic syndrome|paraneoplastic symptoms]], including loss of appetite, [[nausea]], vomiting, and fatigue. Metastasis (spread) of early melanoma is possible, but relatively rare; less than a fifth of melanomas diagnosed early become metastatic. [[Brain metastasis|Brain metastases]] are particularly common in patients with metastatic melanoma.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fiddler IJ | title = Melanoma Metastasis | journal = Cancer Control | volume = 2 | issue = 5 | pages = 398–404 | date = October 1995 | pmid = 10862180 | doi = 10.1177/107327489500200503 | doi-access = free }}</ref> It can also spread to the liver, bones, abdomen, or distant lymph nodes.{{citation needed|date=June 2022}} |

|||

==Cause== |

==Cause== |

||

Melanomas are usually caused by DNA damage resulting from exposure to UV light from the sun. [[#Genetics|Genetics]] also play a role.<ref name="Mayo2016"/><ref name="Greene1999"/> Melanoma can also occur in skin areas with little sun exposure (i.e. mouth, soles of feet, palms of hands, genital areas).<ref name="Goydos 2016 321–329">{{cite book | vauthors = Goydos JS, Shoen SL | title = Melanoma | chapter = Acral Lentiginous Melanoma | series = Cancer Treatment and Research | volume = 167 | pages = 321–9 | date = 2016 | pmid = 26601870 | doi = 10.1007/978-3-319-22539-5_14 | isbn = 978-3-319-22538-8 }}</ref> People with [[dysplastic nevus syndrome]], also known as familial atypical multiple mole melanoma, are at increased risk for the development of melanoma.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Perkins A, Duffy RL | title = Atypical moles: diagnosis and management | journal = American Family Physician | volume = 91 | issue = 11 | pages = 762–767 | date = June 2015 | pmid = 26034853 }}</ref> |

|||

Melanomas are usually caused by DNA damage resulting from exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light from the sun. |

|||

Having more than 50 moles indicates an increased risk of melanoma. A weakened immune system makes cancer development easier due to the body's weakened ability to fight cancer cells.<ref name="Mayo2016">{{cite news|url=http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/melanoma/basics/risk-factors/con-20026009|title=Melanoma Risk factors |work=Mayo Clinic|access-date=10 April 2017 |url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170410133759/http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/melanoma/basics/risk-factors/con-20026009|archive-date=10 April 2017}}</ref> |

|||

===UV radiation=== |

===UV radiation=== |

||

UV radiation exposure from tanning beds increases the risk of melanoma.<ref name="pmid22833605">{{cite journal | vauthors = Boniol M, Autier P, Boyle P, Gandini S | title = Cutaneous melanoma attributable to sunbed use: systematic review and meta-analysis | journal = BMJ | volume = 345 | pages = e4757 | date = July 2012 | pmid = 22833605 | pmc = 3404185 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.e4757 }}</ref> The [[International Agency for Research on Cancer]] finds that tanning beds are "carcinogenic to humans" and that people who begin using tanning devices before the age of thirty years are 75% more likely to develop melanoma.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = El Ghissassi F, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, Bouvard V, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L, Cogliano V | title = A review of human carcinogens--part D: radiation | journal = The Lancet. Oncology | volume = 10 | issue = 8 | pages = 751–752 | date = August 2009 | pmid = 19655431 | doi = 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70213-X | collaboration = WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

Those who work in airplanes also appear to have an increased risk, believed to be due to greater exposure to UV.<ref>{{cite journal| |

Those who work in airplanes also appear to have an increased risk, believed to be due to greater exposure to UV.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sanlorenzo M, Wehner MR, Linos E, Kornak J, Kainz W, Posch C, Vujic I, Johnston K, Gho D, Monico G, McGrath JT, Osella-Abate S, Quaglino P, Cleaver JE, Ortiz-Urda S | title = The risk of melanoma in airline pilots and cabin crew: a meta-analysis | journal = JAMA Dermatology | volume = 151 | issue = 1 | pages = 51–58 | date = January 2015 | pmid = 25188246 | pmc = 4482339 | doi = 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.1077 }}</ref> |

||

[[ |

[[UVB]] light, emanating from the sun at wavelengths between 315 and 280 nm, is absorbed directly by DNA in skin cells, which results in a type of [[direct DNA damage]] called [[pyrimidine dimers|cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers]]. [[Thymine]], [[cytosine]], or cytosine-thymine [[pyrimidine dimer|dimers]] are formed by the joining of two adjacent [[pyrimidine]] bases within a strand of DNA. [[Ultraviolet A|UVA]] light presents at wavelengths longer than UVB (between 400 and 315 nm); and it can also be absorbed directly by DNA in skin cells, but at lower efficiencies{{mdash}}about 1/100 to 1/1000 of UVB.<ref name="pmid22005748">{{cite journal | vauthors = Rünger TM, Farahvash B, Hatvani Z, Rees A | title = Comparison of DNA damage responses following equimutagenic doses of UVA and UVB: a less effective cell cycle arrest with UVA may render UVA-induced pyrimidine dimers more mutagenic than UVB-induced ones | journal = Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences | volume = 11 | issue = 1 | pages = 207–215 | date = January 2012 | pmid = 22005748 | doi = 10.1039/c1pp05232b | s2cid = 25209863 | doi-access = free | bibcode = 2012PhPhS..11..207R }}</ref> |

||

Exposure to radiation (UVA and UVB) is a major contributor to developing melanoma.<ref name="uva">{{cite journal | vauthors = Wang SQ, Setlow R, Berwick M, Polsky D, Marghoob AA, Kopf AW, Bart RS | title = Ultraviolet A and melanoma: a review | journal = Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology | volume = 44 | issue = 5 | pages = 837–846 | date = May 2001 | pmid = 11312434 | doi = 10.1067/mjd.2001.114594 | s2cid = 7655216 }}</ref> Occasional extreme sun exposure that results in "[[sunburn]]" on areas of the human body is causally related to melanoma;<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Oliveria SA, Saraiya M, Geller AC, Heneghan MK, Jorgensen C | title = Sun exposure and risk of melanoma | journal = Archives of Disease in Childhood | volume = 91 | issue = 2 | pages = 131–138 | date = February 2006 | pmid = 16326797 | pmc = 2082713 | doi = 10.1136/adc.2005.086918 }}</ref> and such areas of only intermittent exposure apparently explains why melanoma is more common on the back in men and on the legs in women. The risk appears to be strongly influenced by socioeconomic conditions rather than indoor versus outdoor occupations; it is more common in professional and administrative workers than unskilled workers.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lee JA, Strickland D | title = Malignant melanoma: social status and outdoor work | journal = British Journal of Cancer | volume = 41 | issue = 5 | pages = 757–763 | date = May 1980 | pmid = 7426301 | pmc = 2010319 | doi = 10.1038/bjc.1980.138 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Pion IA, Rigel DS, Garfinkel L, Silverman MK, Kopf AW | title = Occupation and the risk of malignant melanoma | journal = Cancer | volume = 75 | issue = 2 Suppl | pages = 637–644 | date = January 1995 | pmid = 7804988 | doi = 10.1002/1097-0142(19950115)75:2+<637::aid-cncr2820751404>3.0.co;2-# | s2cid = 196354681 }}</ref> Other factors are [[mutation]]s in (or total loss of) [[tumor suppressor gene]]s. Using [[sunbed]]s with their deeply penetrating UVA rays has been linked to the development of skin cancers, including melanoma.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/notes/2005/np07/en/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090616124844/http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/notes/2005/np07/en/|url-status=dead|title=WHO | The World Health Organization recommends that no person under 18 should use a sunbed|archive-date=16 June 2009|website=WHO}}</ref> |

|||

Possible significant elements in determining risk include the intensity and duration of sun exposure, the age at which sun exposure occurs, and the degree of [[skin pigmentation]]. Melanoma rates tend to be highest in countries settled by migrants from Europe which have a large amount of direct, intense sunlight to which the skin of the settlers is not adapted, most notably Australia. Exposure during childhood is a more important risk factor than exposure in adulthood. This is seen in migration studies in Australia.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Khlat M, Vail A, Parkin M, Green A | title = Mortality from melanoma in migrants to Australia: variation by age at arrival and duration of stay | journal = American Journal of Epidemiology | volume = 135 | issue = 10 | pages = 1103–1113 | date = May 1992 | pmid = 1632422 | doi = 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116210 }}</ref> |

|||

Incurring multiple severe sunburns increases the likelihood that future sunburns develop into melanoma due to cumulative damage.<ref name=Mayo2016/> UV-high sunlight and tanning beds are the main sources of UV radiation that increase the risk for melanoma<ref>{{Cite web |date=1 September 2022 |title=Can we get skin cancer from tanning beds? |url=https://www.curadermbcc.eu/blog/skin-cancer-from-tanning-beds/ |access-date=3 September 2022 |website=CuradermBCC |language=en-US |archive-date=3 September 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220903131033/https://www.curadermbcc.eu/blog/skin-cancer-from-tanning-beds/ |url-status=live }}</ref> and living close to the equator increases exposure to UV radiation.<ref name=Mayo2016/> |

|||

===Genetics=== |

===Genetics=== |

||

A number of rare mutations, which often run in families, |

A number of rare mutations, which often run in families, greatly increase melanoma susceptibility.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Soura E, Eliades PJ, Shannon K, Stratigos AJ, Tsao H | title = Hereditary melanoma: Update on syndromes and management: Genetics of familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome | journal = Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology | volume = 74 | issue = 3 | pages = 395–407; quiz 408–410 | date = March 2016 | pmid = 26892650 | pmc = 4761105 | doi = 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.08.038 }}</ref> Several [[gene]]s increase risks. Some rare genes have a relatively high risk of causing melanoma; some more common genes, such as a gene called [[melanocortin 1 receptor|''MC1R'']] that causes red hair, have a relatively lower elevated risk. [[Genetic testing]] can be used to search for the mutations.{{citation needed|date=June 2022}} |

||

One class of mutations affects the gene [[P16 (gene)|CDKN2A]]. An alternative [[reading frame]] mutation in this gene leads to the destabilization of [[p53]], a [[transcription factor]] involved in [[apoptosis]] and in |

One class of mutations affects the gene [[P16 (gene)|''CDKN2A'']]. An alternative [[reading frame]] mutation in this gene leads to the destabilization of [[p53]], a [[transcription factor]] involved in [[apoptosis]] and in 50% of human cancers. Another mutation in the same gene results in a nonfunctional inhibitor of [[CDK4]], a [[cyclin]]-dependent [[kinase]] that promotes [[cell division]]. Mutations that cause the skin condition [[xeroderma pigmentosum]] (XP) also increase melanoma susceptibility. Scattered throughout the genome, these mutations reduce a cell's ability to repair DNA. Both CDKN2A and XP mutations are highly [[Genetic penetrance|penetrant]] (the chances of a carrier to express the phenotype is high).{{citation needed|date=June 2022}} |

||

Familial melanoma is genetically heterogeneous,<ref>{{ |

Familial melanoma is genetically heterogeneous,<ref name="Greene1999">{{cite journal | vauthors = Greene MH | title = The genetics of hereditary melanoma and nevi. 1998 update | journal = Cancer | volume = 86 | issue = 11 Suppl | pages = 2464–2477 | date = December 1999 | pmid = 10630172 | doi = 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19991201)86:11+<2464::AID-CNCR3>3.0.CO;2-F | s2cid = 32817426 | doi-access = free }}</ref> and loci for familial melanoma appear on the [[chromosome]] arms 1p, 9p and 12q. Multiple genetic events have been related to melanoma's [[pathogenesis]] (disease development).<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Halachmi S, Gilchrest BA | title = Update on genetic events in the pathogenesis of melanoma | journal = Current Opinion in Oncology | volume = 13 | issue = 2 | pages = 129–136 | date = March 2001 | pmid = 11224711 | doi = 10.1097/00001622-200103000-00008 | s2cid = 29876528 }}</ref> The multiple [[Tumor suppressor gene|tumor suppressor]] 1 (CDKN2A/MTS1) gene encodes p16INK4a – a low-[[molecular weight]] protein inhibitor of [[cyclin-dependent kinase|cyclin-dependent protein kinases]] (CDKs) – which has been localised to the p21 region of [[Chromosome 9 (human)|human chromosome 9]].<ref>{{cite web | url = https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=gene&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=full_report&list_uids=1029 | title = CDKN2A cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (melanoma, p16, inhibits CDK4) | publisher = U.S. National Library of Medicine | access-date = 4 September 2017 | archive-date = 17 November 2004 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20041117054925/http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=gene | url-status = live }}</ref> FAMMM is typically characterized by having 50 or more combined moles in addition to a family history of melanoma.<ref name="Goydos 2016 321–329"/> It is transmitted autosomal dominantly and mostly associated with the ''CDKN2A'' mutations.<ref name="Goydos 2016 321–329"/> People who have CDKN2A mutation associated FAMMM have a 38 fold increased risk of pancreatic cancer.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Soura E, Eliades PJ, Shannon K, Stratigos AJ, Tsao H | title = Hereditary melanoma: Update on syndromes and management: Genetics of familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome | journal = Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology | volume = 74 | issue = 3 | pages = 395–407; quiz 408–10 | date = March 2016 | pmid = 26892650 | pmc = 4761105 | doi = 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.08.038 }}</ref> |

||

Other mutations confer lower risk, but are more |

Other mutations confer lower risk, but are more common in the population. People with mutations in the ''[[MC1R]]'' gene are two to four times more likely to develop melanoma than those with two wild-type (typical unaffected type) copies. ''MC1R'' mutations are very common, and all red-haired people have a mutated copy.{{Citation needed|date=November 2018}} Mutation of the ''[[MDM2]]'' SNP309 gene is associated with increased risks for younger women.<ref name="pmid19318491">{{cite journal | vauthors = Firoz EF, Warycha M, Zakrzewski J, Pollens D, Wang G, Shapiro R, Berman R, Pavlick A, Manga P, Ostrer H, Celebi JT, Kamino H, Darvishian F, Rolnitzky L, Goldberg JD, Osman I, Polsky D | title = Association of MDM2 SNP309, age of onset, and gender in cutaneous melanoma | journal = Clinical Cancer Research | volume = 15 | issue = 7 | pages = 2573–2580 | date = April 2009 | pmid = 19318491 | pmc = 3881546 | doi = 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2678 }}</ref> |

||

Fair- and red-haired people, persons with multiple atypical [[nevi]] or [[dysplastic nevus|dysplastic nevi]] and persons born with giant [[congenital melanocytic nevi]] are at increased risk.<ref name="IMAGE">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bliss JM, Ford D, Swerdlow AJ, Armstrong BK, Cristofolini M, Elwood JM, Green A, Holly EA, Mack T, MacKie RM | title = Risk of cutaneous melanoma associated with pigmentation characteristics and freckling: systematic overview of 10 case-control studies. The International Melanoma Analysis Group (IMAGE) | journal = International Journal of Cancer | volume = 62 | issue = 4 | pages = 367–376 | date = August 1995 | pmid = 7635560 | doi = 10.1002/ijc.2910620402 | s2cid = 9539601 }}</ref> |

|||

A family history of melanoma greatly increases a person's risk, because mutations in several genes have been found in melanoma-prone families.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Miller AJ, Mihm MC | title = Melanoma | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 355 | issue = 1 | pages = 51–65 | date = July 2006 | pmid = 16822996 | doi = 10.1056/NEJMra052166 }}</ref><ref name="Mayo2016" /> People with a history of one melanoma are at increased risk of developing a second primary tumor.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Rhodes AR, Weinstock MA, Fitzpatrick TB, Mihm MC, Sober AJ | title = Risk factors for cutaneous melanoma. A practical method of recognizing predisposed individuals | journal = JAMA | volume = 258 | issue = 21 | pages = 3146–3154 | date = December 1987 | pmid = 3312689 | doi = 10.1001/jama.258.21.3146 }}</ref> |

|||

Fair skin is the result of having less melanin in the skin, which means less protection from UV radiation exists.<ref name=Mayo2016/> |

|||

==Pathophysiology== |

==Pathophysiology== |

||

[[File:Diagram showing where melanoma is most likely to develop CRUK 383.svg|thumb|right|Where melanoma is most likely to develop]] |

[[File:Diagram showing where melanoma is most likely to develop CRUK 383.svg|thumb|right|Where melanoma is most likely to develop]] |

||

[[File:Metastatic Melanoma Cells Nci-vol-9872-300.jpg|thumb|Molecular basis for melanoma cell motility: actin-rich [[podosome]]s (yellow), along with [[cell nucleus|cell nuclei]] (blue), actin (red), and an actin regulator (green)]] |

|||

The earliest stage of melanoma starts when the melanocytes begin to grow out of control. Melanocytes are found between the outer layer of the skin (the [[epidermis (skin)|epidermis]]) and the next layer (the [[dermis]]). This early stage of the disease is called the radial growth phase, and the tumor is less than 1 mm thick. Because the cancer cells have not yet reached the blood vessels lower down in the skin, it is very unlikely that this early-stage cancer will spread to other parts of the body. If the melanoma is detected at this stage, then it can usually be completely removed with surgery. |

|||

The earliest stage of melanoma starts when melanocytes begin out-of-control growth. Melanocytes are found between the outer layer of the skin (the [[epidermis (skin)|epidermis]]) and the next layer (the [[dermis]]). This early stage of the disease is called the radial growth phase, when the tumor is less than 1 mm thick, and spreads at the level of the basal epidermis.<ref name="CiarlettaForet2010">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ciarletta P, Foret L, Ben Amar M | title = The radial growth phase of malignant melanoma: multi-phase modelling, numerical simulations and linear stability analysis | journal = Journal of the Royal Society, Interface | volume = 8 | issue = 56 | pages = 345–368 | date = March 2011 | pmid = 20656740 | pmc = 3030817 | doi = 10.1098/rsif.2010.0285 }}</ref> Because the cancer cells have not yet reached the blood vessels deeper in the skin, it is very unlikely that this early-stage melanoma will spread to other parts of the body. If the melanoma is detected at this stage, then it can usually be completely removed with surgery.{{citation needed|date=June 2022}} |

|||

When the tumor cells start to move in a different direction |

When the tumor cells start to move in a different direction – vertically up into the epidermis and into the [[papillary dermis]] – cell behaviour changes dramatically.<ref name=Hershkovitz10/> |

||

The next step in the evolution is the invasive radial growth phase, |

The next step in the evolution is the invasive radial growth phase, in which individual cells start to acquire invasive potential. From this point on, melanoma is capable of spreading.{{Citation needed|date=July 2023}} The [[Breslow's depth]] of the lesion is usually less than {{convert|1|mm|2|abbr=on|lk=out}}, while the [[Clark level]] is usually 2. |

||

The |

The vertical growth phase (VGP) following is invasive melanoma. The tumor becomes able to grow into the surrounding tissue and can spread around the body through blood or [[lymph vessel]]s. The tumor thickness is usually more than {{convert|1|mm|2|abbr=on|lk=out}}, and the tumor involves the deeper parts of the dermis. |

||

The host elicits an immunological reaction against the tumor |

The host elicits an immunological reaction against the tumor during the VGP,<ref>{{cite journal |title=ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I. Abstract: Protective effect of a brisk tumor infiltrating lymphocyte infiltrate in melanoma: An EORTC melanoma group study |journal=Journal of Clinical Oncology |volume=25 |issue=18S |page=8519 |year=2007 |doi=10.1200/jco.2007.25.18_suppl.8519 |url=http://www.asco.org/ascov2/Meetings/Abstracts?vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=47&abstractID=34439 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110725021007/http://www.asco.org/ascov2/Meetings/Abstracts?vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=47&abstractID=34439 |archive-date=25 July 2011 | vauthors = Spatz A, Gimotty PA, Cook MG, van den Oord JJ, Desai N, Eggermont AM, Keilholz U, Ruiter DJ, Mihm MC |url-access=subscription }}</ref> which is judged by the presence and activity of the [[tumor infiltrating lymphocyte]]s (TILs). These cells sometimes completely destroy the primary tumor; this is called regression, which is the latest stage of development. In certain cases, the primary tumor is completely destroyed and only the metastatic tumor is discovered. About 40% of human melanomas contain activating mutations affecting the structure of the B-Raf [[protein]], resulting in [[Receptor (biochemistry)#Constitutive activity|constitutive]] signaling through the Raf to [[MAP kinase]] pathway.<ref name="pmid20697348">{{cite journal | vauthors = Davies MA, Samuels Y | title = Analysis of the genome to personalize therapy for melanoma | journal = Oncogene | volume = 29 | issue = 41 | pages = 5545–5555 | date = October 2010 | pmid = 20697348 | pmc = 3169242 | doi = 10.1038/onc.2010.323 }}</ref> |

||

A cause common to most cancers is damage to DNA.<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Barrett JC |chapter=Mutagenesis and Carcinogenesis|chapter-url= https://archive.org/details/originsofhumanca00brug/ |title=Origins of Human Cancer |publisher=Cold Spring Harbor Press |year=1991 |isbn=0-87969-404-1 | veditors = Brugge J, Curran T, Harlow E, McCormick F |editor-link1 =Joan Brugge |editor-link2=Tom Curran (medical researcher) |editor-link3=Ed Harlow |chapter-url-access=registration |via=Internet Archive |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/originsofhumanca00brug }}</ref> UVA light mainly causes [[thymine dimer]]s.<ref name="pmid21901217">{{cite journal | vauthors = Sage E, Girard PM, Francesconi S | title = Unravelling UVA-induced mutagenesis | journal = Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences | volume = 11 | issue = 1 | pages = 74–80 | date = January 2012 | pmid = 21901217 | doi = 10.1039/c1pp05219e | s2cid = 45189513 | doi-access = free | bibcode = 2012PhPhS..11...74S }}</ref> UVA also produces [[reactive oxygen species]] and these inflict other DNA damage, primarily single-strand breaks, oxidized [[pyrimidines]] and the oxidized [[purine]] [[8-oxoguanine]] (a mutagenic DNA change) at 1/10, 1/10, and 1/3rd the frequencies of UVA-induced thymine dimers, respectively. |

|||

If unrepaired, CPD photoproducts can lead to mutations by inaccurate [[ |

If unrepaired, cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer (CPD) photoproducts can lead to mutations by inaccurate [[translesion synthesis]] during DNA replication or repair. The most frequent mutations due to inaccurate synthesis past CPDs are cytosine to thymine (C>T) or CC>TT [[transition (genetics)|transition mutations]]. These are commonly referred to as UV fingerprint mutations, as they are the most specific mutation caused by UV, being frequently found in sun-exposed skin, but rarely found in internal organs.<ref name="pmid23303275">{{cite journal | vauthors = Budden T, Bowden NA | title = The role of altered nucleotide excision repair and UVB-induced DNA damage in melanomagenesis | journal = International Journal of Molecular Sciences | volume = 14 | issue = 1 | pages = 1132–1151 | date = January 2013 | pmid = 23303275 | pmc = 3565312 | doi = 10.3390/ijms14011132 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Errors in DNA repair of UV photoproducts, or inaccurate synthesis past these photoproducts, can also lead to deletions, insertions, and [[chromosomal translocation]]s. |

||

The entire genomes of 25 melanomas were sequenced |

The entire genomes of 25 melanomas were sequenced.<ref name="pmid22622578">{{cite journal | vauthors = Berger MF, Hodis E, Heffernan TP, Deribe YL, Lawrence MS, Protopopov A, Ivanova E, Watson IR, Nickerson E, Ghosh P, Zhang H, Zeid R, Ren X, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko AY, Wagle N, Sucker A, Sougnez C, Onofrio R, Ambrogio L, Auclair D, Fennell T, Carter SL, Drier Y, Stojanov P, Singer MA, Voet D, Jing R, Saksena G, Barretina J, Ramos AH, Pugh TJ, Stransky N, Parkin M, Winckler W, Mahan S, Ardlie K, Baldwin J, Wargo J, Schadendorf D, Meyerson M, Gabriel SB, Golub TR, Wagner SN, Lander ES, Getz G, Chin L, Garraway LA | title = Melanoma genome sequencing reveals frequent PREX2 mutations | journal = Nature | volume = 485 | issue = 7399 | pages = 502–506 | date = May 2012 | pmid = 22622578 | pmc = 3367798 | doi = 10.1038/nature11071 | bibcode = 2012Natur.485..502B }}</ref> On average, about 80,000 mutated bases (mostly C>T transitions) and about 100 structural rearrangements were found per melanoma genome. This is much higher than the roughly 70 mutations across generations (parent to child).<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Roach JC, Glusman G, Smit AF, Huff CD, Hubley R, Shannon PT, Rowen L, Pant KP, Goodman N, Bamshad M, Shendure J, Drmanac R, Jorde LB, Hood L, Galas DJ | title = Analysis of genetic inheritance in a family quartet by whole-genome sequencing | journal = Science | volume = 328 | issue = 5978 | pages = 636–639 | date = April 2010 | pmid = 20220176 | pmc = 3037280 | doi = 10.1126/science.1186802 | bibcode = 2010Sci...328..636R }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Campbell CD, Chong JX, Malig M, Ko A, Dumont BL, Han L, Vives L, O'Roak BJ, Sudmant PH, Shendure J, Abney M, Ober C, Eichler EE | title = Estimating the human mutation rate using autozygosity in a founder population | journal = Nature Genetics | volume = 44 | issue = 11 | pages = 1277–1281 | date = November 2012 | pmid = 23001126 | pmc = 3483378 | doi = 10.1038/ng.2418 }}</ref> Among the 25 melanomas, about 6,000 protein-coding genes had [[missense mutation|missense]], [[nonsense mutation|nonsense]], or [[splice site mutation]]s. The transcriptomes of over 100 melanomas has also been sequenced and analyzed. Almost 70% of all human protein-coding genes are expressed in melanoma. Most of these genes are also expressed in other normal and cancer tissues, with some 200 genes showing a more specific expression pattern in melanoma compared to other forms of cancer. Examples of melanoma specific genes are [[tyrosinase]], [[MLANA]], and [[PMEL (gene)|''PMEL'']].<ref name="proteinatlas.org">{{cite web|url=https://www.proteinatlas.org/humanpathology/melanoma|title=The human pathology proteome in melanoma – The Human Protein Atlas|website=www.proteinatlas.org|access-date=2 October 2017|archive-date=2 October 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171002215621/https://www.proteinatlas.org/humanpathology/melanoma|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Uhlen eaan2507">{{cite journal | vauthors = Uhlen M, Zhang C, Lee S, Sjöstedt E, Fagerberg L, Bidkhori G, Benfeitas R, Arif M, Liu Z, Edfors F, Sanli K, von Feilitzen K, Oksvold P, Lundberg E, Hober S, Nilsson P, Mattsson J, Schwenk JM, Brunnström H, Glimelius B, Sjöblom T, Edqvist PH, Djureinovic D, Micke P, Lindskog C, Mardinoglu A, Ponten F | title = A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome | journal = Science | volume = 357 | issue = 6352 | pages = eaan2507 | date = August 2017 | pmid = 28818916 | doi = 10.1126/science.aan2507 | s2cid = 206659235 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

||

UV radiation causes [[DNA damage|damage]] to the DNA of cells, typically thymine dimerization, which when unrepaired can create mutations in the cell's genes. This strong mutagenic factor makes cutaneous melanoma the tumor type with the highest number of mutations.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Ellrott K, Bailey MH, Saksena G, Covington KR, Kandoth C, Stewart C, Hess J, Ma S, Chiotti KE, McLellan M, Sofia HJ, Hutter C, Getz G, Wheeler D, Ding L | title = Scalable Open Science Approach for Mutation Calling of Tumor Exomes Using Multiple Genomic Pipelines | journal = Cell Systems | volume = 6 | issue = 3 | pages = 271–281.e7 | date = March 2018 | pmid = 29596782 | pmc = 6075717 | doi = 10.1016/j.cels.2018.03.002 }}</ref> When the cell [[cell division|divides]], these mutations are propagated to new generations of cells. If the mutations occur in [[protooncogene]]s or [[tumor suppressor gene]]s, the rate of [[mitosis]] in the mutation-bearing cells can become uncontrolled, leading to the formation of a [[tumor]]. Data from patients suggest that aberrant levels of activating transcription factor in the nucleus of melanoma cells are associated with increased metastatic activity of melanoma cells;<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Leslie MC, Bar-Eli M | title = Regulation of gene expression in melanoma: new approaches for treatment | journal = Journal of Cellular Biochemistry | volume = 94 | issue = 1 | pages = 25–38 | date = January 2005 | pmid = 15523674 | doi = 10.1002/jcb.20296 | s2cid = 23515325 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bhoumik A, Singha N, O'Connell MJ, Ronai ZA | title = Regulation of TIP60 by ATF2 modulates ATM activation | journal = The Journal of Biological Chemistry | volume = 283 | issue = 25 | pages = 17605–17614 | date = June 2008 | pmid = 18397884 | pmc = 2427333 | doi = 10.1074/jbc.M802030200 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bhoumik A, Jones N, Ronai Z | title = Transcriptional switch by activating transcription factor 2-derived peptide sensitizes melanoma cells to apoptosis and inhibits their tumorigenicity | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 101 | issue = 12 | pages = 4222–4227 | date = March 2004 | pmid = 15010535 | pmc = 384722 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.0400195101 | doi-access = free | bibcode = 2004PNAS..101.4222B }}</ref> studies from mice on skin cancer tend to confirm a role for activating transcription factor-2 in cancer progression.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Vlahopoulos SA, Logotheti S, Mikas D, Giarika A, Gorgoulis V, Zoumpourlis V | title = The role of ATF-2 in oncogenesis | journal = BioEssays | volume = 30 | issue = 4 | pages = 314–327 | date = April 2008 | pmid = 18348191 | doi = 10.1002/bies.20734 | s2cid = 678541 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Huang Y, Minigh J, Miles S, Niles RM | title = Retinoic acid decreases ATF-2 phosphorylation and sensitizes melanoma cells to taxol-mediated growth inhibition | journal = Journal of Molecular Signaling | volume = 3 | pages = 3 | date = February 2008 | pmid = 18269766 | pmc = 2265711 | doi = 10.1186/1750-2187-3-3 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

==Diagnosis== |

|||

[[File:Melanoma vs normal mole ABCD rule NCI Visuals Online.jpg|thumb|ABCD rule illustration: On the left side from top to bottom: melanomas showing (A) Asymmetry, (B) a border that is uneven, ragged, or notched, (C) coloring of different shades of brown, black, or tan and (D) diameter that had changed in size. The normal moles on the right side do not have abnormal characteristics (no asymmetry, even border, even color, no change in diameter).]] |

|||

[[File:Dermatoscope1.JPG|thumb|A [[dermatoscope]]]] |

|||

[[File:Malignant melanoma (1) at thigh Case 01.jpg|thumb|Melanoma in skin biopsy with [[H&E stain]] — this case may represent superficial spreading melanoma.]] |

|||

[[File:Lymph node with almost complete replacement by metastatic melanoma.jpg|thumb|Lymph node with almost complete replacement by metastatic melanoma. The brown pigment is focal deposition of melanin.]] |

|||

Visual diagnosis of melanomas is still the most common method employed by health professionals.<ref name="ap01">{{cite journal |author=Wurm EM, Soyer HP |title=Scanning for melanoma |date=October 2010 |journal=Australian Prescriber |issue=33 |pages=150–5 |url=http://www.australianprescriber.com/magazine/33/5/150/5}}</ref> Moles that are irregular in color or shape are often treated as candidates of melanoma. To detect melanomas (and increase survival rates), it is recommended to learn what they look like (see "ABCDE" mnemonic below), to be aware of [[Melanocytic nevus|moles]] and check for changes (shape, size, color, itching or bleeding) and to show any suspicious moles to a doctor with an interest and skills in skin malignancy.<ref>{{cite web |title=Prevention: ABCD's of Melanoma |publisher=American Melanoma Foundation |url=http://www.melanomafoundation.org/prevention/abcd.htm}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal| author = Friedman R, Rigel D, Kopf A | title = Early detection of malignant melanoma: the role of physician examination and self-examination of the skin | journal = CA Cancer J Clin | volume = 35 | issue = 3 | pages = 130–51 | year = 1985| pmid = 3921200 |url=http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/canjclin.35.3.130/abstract | doi = 10.3322/canjclin.35.3.130}}</ref> |

|||

[[Cancer stem cell]]s may also be involved.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Parmiani G | title = Melanoma Cancer Stem Cells: Markers and Functions | journal = Cancers | volume = 8 | issue = 3 | pages = 34 | date = March 2016 | pmid = 26978405 | pmc = 4810118 | doi = 10.3390/cancers8030034 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

A popular method for remembering the signs and symptoms of melanoma is the mnemonic "ABCDE": |

|||

* ''A''symmetrical skin lesion. |

|||

* ''B''order of the lesion is irregular. |

|||

* ''C''olor: melanomas usually have multiple colors. |

|||

* ''D''iameter: moles greater than 6 mm are more likely to be melanomas than smaller moles. |

|||

* ''E''nlarging: Enlarging or evolving |

|||

=== Gene mutations === |

|||

A weakness in this system is the diameter. Many melanomas present themselves as lesions smaller than 6 mm in diameter; and all melanomas were malignant on day 1 of growth, which is merely a dot. An astute physician will examine all abnormal moles, including ones less than 6 mm in diameter. [[Seborrheic keratosis]] may meet some or all of the ABCD criteria, and can lead to [[false alarm]]s among laypeople and sometimes even physicians. An experienced doctor can generally distinguish seborrheic keratosis from melanoma upon examination, or with [[dermatoscopy]]. |

|||

Large-scale studies, such as [[The Cancer Genome Atlas]], have characterized recurrent [[Somatic evolution in cancer|somatic alterations]] likely driving initiation and development of cutaneous melanoma. The Cancer Genome Atlas study has established four subtypes: ''BRAF'' mutant, ''RAS'' mutant, ''NF1'' mutant, and triple wild-type.<ref name="Akbani_2015">{{cite journal | title = Genomic Classification of Cutaneous Melanoma | journal = Cell | volume = 161 | issue = 7 | pages = 1681–1696 | date = June 2015 | pmid = 26091043 | pmc = 4580370 | doi = 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.044 | collaboration = Cancer Genome Atlas Network | vauthors = Akbani R, Akdemir KC, Aksoy BA, Albert M, Ally A, Amin SB, Arachchi H, Arora A, Auman JT, Ayala B, Baboud J, Balasundaram M, Balu S, Barnabas N, Bartlett J, Bartlett P, Bastian BC, Baylin SB, Behera M, Belyaev D, Benz C, Bernard B, Beroukhim R, Bir N, Black AD, Bodenheimer T, Boice L, Boland GM, Bono R, Bootwalla MS }}</ref> |

|||

The most frequent mutation occurs in the 600th codon of [[BRAF (gene)|''BRAF'']] (50% of cases). ''BRAF'' is normally involved in cell growth, and this specific mutation renders the protein constitutively active and independent of normal physiological regulation, thus fostering tumor growth.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Ascierto PA, Kirkwood JM, Grob JJ, Simeone E, Grimaldi AM, Maio M, Palmieri G, Testori A, Marincola FM, Mozzillo N | title = The role of BRAF V600 mutation in melanoma | journal = Journal of Translational Medicine | volume = 10 | issue = 1 | pages = 85 | date = July 2012 | pmid = 22554099 | pmc = 3391993 | doi = 10.1186/1479-5876-10-85 | doi-access = free }}</ref> RAS genes ([[Neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog|NRAS]], [[HRAS]] and [[KRAS]]) are also recurrently mutated (30% of TCGA cases) and mutations in the 61st or 12th codons trigger oncogenic activity. Loss-of-function mutations often affect [[Tumor suppressor|tumor suppressor genes]] such as [[Neurofibromin 1|NF1]], [[P53|TP53]] and [[CDKN2A]]. Other oncogenic alterations include fusions involving various kinases such as BRAF,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Botton T, Talevich E, Mishra VK, Zhang T, Shain AH, Berquet C, Gagnon A, Judson RL, Ballotti R, Ribas A, Herlyn M, Rocchi S, Brown KM, Hayward NK, Yeh I, Bastian BC | title = Genetic Heterogeneity of BRAF Fusion Kinases in Melanoma Affects Drug Responses | journal = Cell Reports | volume = 29 | issue = 3 | pages = 573–588.e7 | date = October 2019 | pmid = 31618628 | pmc = 6939448 | doi = 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.09.009 }}</ref> RAF1,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = McEvoy CR, Xu H, Smith K, Etemadmoghadam D, San Leong H, Choong DY, Byrne DJ, Iravani A, Beck S, Mileshkin L, Tothill RW, Bowtell DD, Bates BM, Nastevski V, Browning J, Bell AH, Khoo C, Desai J, Fellowes AP, Fox SB, Prall OW | title = Profound MEK inhibitor response in a cutaneous melanoma harboring a GOLGA4-RAF1 fusion | journal = The Journal of Clinical Investigation | volume = 129 | issue = 5 | pages = 1940–1945 | date = May 2019 | pmid = 30835257 | pmc = 6486352 | doi = 10.1172/JCI123089 }}</ref> ALK, RET, ROS1, NTRK1.,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Wiesner T, He J, Yelensky R, Esteve-Puig R, Botton T, Yeh I, Lipson D, Otto G, Brennan K, Murali R, Garrido M, Miller VA, Ross JS, Berger MF, Sparatta A, Palmedo G, Cerroni L, Busam KJ, Kutzner H, Cronin MT, Stephens PJ, Bastian BC | title = Kinase fusions are frequent in Spitz tumours and spitzoid melanomas | journal = Nature Communications | volume = 5 | issue = 1 | pages = 3116 | date = May 2014 | pmid = 24445538 | pmc = 4084638 | doi = 10.1038/ncomms4116 | bibcode = 2014NatCo...5.3116W }}</ref> NTRK3<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Yeh I, Tee MK, Botton T, Shain AH, Sparatta AJ, Gagnon A, Vemula SS, Garrido MC, Nakamaru K, Isoyama T, McCalmont TH, LeBoit PE, Bastian BC | title = NTRK3 kinase fusions in Spitz tumours | journal = The Journal of Pathology | volume = 240 | issue = 3 | pages = 282–290 | date = November 2016 | pmid = 27477320 | pmc = 5071153 | doi = 10.1002/path.4775 }}</ref> and MET<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Yeh I, Botton T, Talevich E, Shain AH, Sparatta AJ, de la Fouchardiere A, Mully TW, North JP, Garrido MC, Gagnon A, Vemula SS, McCalmont TH, LeBoit PE, Bastian BC | title = Activating MET kinase rearrangements in melanoma and Spitz tumours | journal = Nature Communications | volume = 6 | issue = 1 | pages = 7174 | date = May 2015 | pmid = 26013381 | pmc = 4446791 | doi = 10.1038/ncomms8174 | doi-access = free | bibcode = 2015NatCo...6.7174Y }}</ref>'' BRAF, RAS'', and ''NF1'' mutations and kinase fusions are remarkably mutually exclusive, as they occur in different subsets of patients. Assessment of mutation status can, therefore, improve patient stratification and inform targeted therapy with specific inhibitors.{{citation needed|date=September 2022}} |

|||

Some advocate the system "ABCDE",<ref>[http://www.aad.org/public/exams/abcde.html AAD.org]</ref> with E for evolution. Certainly moles that change and evolve will be a concern. Alternatively, some refer to E as elevation. Elevation can help identify a melanoma, but lack of elevation does not mean that the lesion is not a melanoma. Most melanomas are detected in the very early stage, or in-situ stage, before they become elevated. By the time elevation is visible, they may have progressed to the more dangerous invasive stage. |

|||

In some cases (3–7%) mutated versions of ''BRAF'' and ''NRAS'' undergo [[Copy-number variation|copy-number amplification]].<ref name="Akbani_2015" /> |

|||

[[Nodular melanoma]]s do not fulfill these criteria, having their own mnemonic, "EFG": |

|||

=== Metastasis === |

|||

* ''E''levated: the lesion is raised above the surrounding skin. |

|||

The research done by Sarna's team proved that heavily pigmented melanoma cells have [[Young's modulus]] about 4.93, when in non-pigmented ones it was only 0.98.<ref name="Sarna_2019">{{cite journal | vauthors = Sarna M, Krzykawska-Serda M, Jakubowska M, Zadlo A, Urbanska K | title = Melanin presence inhibits melanoma cell spread in mice in a unique mechanical fashion | journal = Scientific Reports | volume = 9 | issue = 1 | pages = 9280 | date = June 2019 | pmid = 31243305 | pmc = 6594928 | doi = 10.1038/s41598-019-45643-9 | bibcode = 2019NatSR...9.9280S }}</ref> In another experiment they found that [[Elasticity (physics)|elasticity]] of melanoma cells is important for its metastasis and growth: non-pigmented tumors were bigger than pigmented and it was much easier for them to spread. They showed that there are both pigmented and non-pigmented cells in melanoma [[Neoplasm|tumors]], so that they can both be [[Drug resistance|drug-resistant]] and metastatic.<ref name="Sarna_2019" /> |

|||

* ''F''irm: the nodule is solid to the touch. |

|||

* ''G''rowing: the nodule is increasing in size. |

|||

==Diagnosis== |

|||

A recent and novel method of melanoma detection is the "ugly duckling sign".<ref>[http://www.skincancer.org/the-ugly-duckling-sign.html SkinCancer.org]</ref><ref name="pmid9828892">{{cite journal |author=Mascaro JM, Mascaro JM |title=The dermatologist's position concerning nevi: a vision ranging from "the ugly duckling" to "little red riding hood" |journal=Arch Dermatol |volume=134 |issue=11 |pages=1484–5 |date=November 1998 |pmid=9828892 |url=http://archderm.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9828892 |doi=10.1001/archderm.134.11.1484}} |

|||

[[File:Melanoma vs normal mole ABCD rule NCI Visuals Online.jpg|thumb|upright=1.3|ABCD rule illustration: On the left side from top to bottom: melanomas showing (A) Asymmetry, (B) a border that is uneven, ragged, or notched, (C) coloring of different shades of brown, black, or tan and (D) diameter that had changed in size. The normal moles on the right side do not have abnormal characteristics (no asymmetry, even border, even color, no change in diameter).]] |

|||

</ref> It is simple, easy to teach, and highly effective in detecting melanoma. Simply, correlation of common characteristics of a person's skin lesion is made. Lesions which greatly deviate from the common characteristics are labeled as an "Ugly Duckling", and further professional exam is required. The "Little Red Riding Hood" sign<ref name="pmid9828892"/> suggests that individuals with fair skin and light-colored hair might have difficult-to-diagnose [[amelanotic melanomas]]. Extra care and caution should be rendered when examining such individuals, as they might have multiple melanomas and severely dysplastic nevi. A dermatoscope must be used to detect "ugly ducklings", as many melanomas in these individuals resemble non-melanomas or are considered to be "wolves in sheep clothing".<ref name="dermnetnz.org">[http://dermnetnz.org/doctors/dermoscopy-course/introduction.html Dermnetnz.org]</ref> These fair-skinned individuals often have lightly pigmented or amelanotic melanomas which will not present easy-to-observe color changes and variation in colors. The borders of these amelanotic melanomas are often indistinct, making visual identification without a dermatoscope very difficult. |

|||

[[File:Pie chart of incidence and malignancy of pigmented skin lesions.png|thumb|upright=1.3|Various [[differential diagnosis|differential diagnoses]] of pigmented skin lesions, by relative [[Incidence (epidemiology)|rates]] upon biopsy and malignancy potential, including "melanoma" at right]] |

|||

Looking at or visually inspecting the area in question is the most common method of suspecting a melanoma.<ref name="ap01">{{cite journal |vauthors=Wurm EM, Soyer HP |title=Scanning for melanoma |date=October 2010 |journal=Australian Prescriber |volume=33 |pages=150–55 |doi=10.18773/austprescr.2010.070 |doi-access=free }}</ref> Moles that are irregular in color or shape are typically treated as candidates. To detect melanomas (and increase survival rates), it is recommended to learn to recognize them (see [[#Signs and symptoms|"ABCDE" mnemonic]]), to regularly examine [[melanocytic nevus|moles]] for changes (shape, size, color, itching or bleeding) and to consult a qualified physician when a candidate appears.<ref>{{cite web |title=Prevention: ABCD's of Melanoma |publisher=American Melanoma Foundation |url=http://www.melanomafoundation.org/prevention/abcd.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20030423111111/http://melanomafoundation.org/prevention/abcd.htm |archive-date=23 April 2003 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Friedman RJ, Rigel DS, Kopf AW | title = Early detection of malignant melanoma: the role of physician examination and self-examination of the skin | journal = CA | volume = 35 | issue = 3 | pages = 130–151 | year = 1985 | pmid = 3921200 | doi = 10.3322/canjclin.35.3.130 | s2cid = 20787489 | doi-access = free }}</ref> In-person inspection of suspicious skin lesions is more accurate than visual inspection of images of suspicious skin lesions.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Grainge MJ, Chuchu N, Ferrante di Ruffano L, Matin RN, Thomson DR, Wong KY, Aldridge RB, Abbott R, Fawzy M, Bayliss SE, Takwoingi Y, Davenport C, Godfrey K, Walter FM, Williams HC | title = Visual inspection for diagnosing cutaneous melanoma in adults | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2018 | issue = 12 | pages = CD013194 | date = December 2018 | pmid = 30521684 | pmc = 6492463 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD013194 }}</ref> |

|||

Amelanotic melanomas and melanomas arising in fair-skinned individuals (see the "Little Red Riding Hood" sign) are very difficult to detect, as they fail to show many of the characteristics in the ABCD rule, break the "Ugly Duckling" sign, and are very hard to distinguish from acne scarring, insect bites, [[Benign fibrous histiocytoma|dermatofibromas]], or [[Lentigo|lentigines]]. |

|||

When used by trained specialists, dermoscopy is more helpful to identify malignant lesions than use of the naked eye alone.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Chuchu N, Ferrante di Ruffano L, Matin RN, Thomson DR, Wong KY, Aldridge RB, Abbott R, Fawzy M, Bayliss SE, Grainge MJ, Takwoingi Y, Davenport C, Godfrey K, Walter FM, Williams HC | title = Dermoscopy, with and without visual inspection, for diagnosing melanoma in adults | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2018 | issue = 12 | pages = CD011902 | date = December 2018 | pmid = 30521682 | pmc = 6517096 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD011902.pub2 }}</ref> Reflectance confocal microscopy may have better sensitivity and specificity than dermoscopy in diagnosing cutaneous melanoma but more studies are needed to confirm this result.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Saleh D, Chuchu N, Bayliss SE, Patel L, Davenport C, Takwoingi Y, Godfrey K, Matin RN, Patalay R, Williams HC | title = Reflectance confocal microscopy for diagnosing cutaneous melanoma in adults | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 12 | issue = 12 | pages = CD013190 | date = December 2018 | pmid = 30521681 | pmc = 6492459 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD013190 | collaboration = Cochrane Skin Group }}</ref> |

|||

Following a visual examination and a dermatoscopic exam,<ref name="dermnetnz.org"/> or ''in vivo'' diagnostic tools such as a confocal microscope, the doctor may [[biopsy]] the suspicious mole. A [[skin biopsy]] performed under [[local anesthesia]] is often required to assist in making or confirming the diagnosis and in defining the severity of the melanoma. If the mole is malignant, the mole and an area around it need excision. Elliptical excisional biopsies may remove the tumor, followed by histological analysis and Breslow scoring. [[Skin biopsy#Punch biopsy|Punch biopsies]] are contraindicated in suspected melanomas, for fear of seeding tumor cells and hastening the spread of the malignant cells. |

|||

However, many melanomas present as lesions smaller than 6 mm in diameter, and all melanomas are malignant when they first appear as a small dot. Physicians typically examine all moles, including those less than 6 mm in diameter. [[Seborrheic keratosis]] may meet some or all of the ABCD criteria, and can lead to [[false alarm]]s. Doctors can generally distinguish seborrheic keratosis from melanoma upon examination or with [[dermatoscopy]].{{Citation needed|date=November 2018}} |

|||

Total body photography, which involves photographic documentation of as much body surface as possible, is often used during follow-up of high-risk patients. The technique has been reported to enable early detection and provides a cost-effective approach (being possible with the use of any digital camera), but its efficacy has been questioned due to its inability to detect macroscopic changes.<ref name="ap01" /> The diagnosis method should be used in conjunction with (and not as a replacement for) dermoscopic imaging, with a combination of both methods appearing to give extremely high rates of detection. |

|||

Some advocate replacing "enlarging" with "evolving": moles that change and evolve are a concern. Alternatively, some practitioners prefer "elevation". Elevation can help identify a melanoma, but lack of elevation does not mean that the lesion is not a melanoma. Most melanomas in the US are detected before they become elevated. By the time elevation is visible, they may have progressed to the more dangerous invasive stage.{{Citation needed|date=September 2022}} |

|||

===Classification=== |

|||

[[File:Anal Melanoma.JPG|thumb|An anal melanoma]] |

|||

Melanoma is divided into the following types:<ref>{{Cite book|author=James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. |title=Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology|publisher=Saunders Elsevier |year=2006 |isbn=0-7216-2921-0 |pages=694–9}}</ref> |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

* [[Lentigo maligna]] |

|||

File:Malignant melanoma (1) at thigh Case 01.jpg|Melanoma in skin biopsy with [[H&E stain]] – this case may represent superficial spreading melanoma. |

|||

* [[Lentigo maligna melanoma]] |

|||

File:Lymph node with almost complete replacement by metastatic melanoma.jpg|Lymph node with almost complete replacement by metastatic melanoma. The brown pigment is a focal deposition of melanin. |

|||

* [[Superficial spreading melanoma]] |

|||

File:Dermatoscope1.JPG|A [[dermatoscope]] |

|||

* [[Acral lentiginous melanoma]] |

|||

File:Malignant Melanoma, right posterior thigh.png|Melanoma, right posterior thigh |

|||

* [[Mucosal melanoma]] |

|||

File:Melanoma in situ, vertex scalp.jpg|Melanoma in situ, vertex scalp marked for biopsy |

|||

* [[Nodular melanoma]] |

|||

File:Malignant Melanoma in situ evolving Right clavicle.jpg|Melanoma in situ, evolving, right clavicle marked for biopsy |

|||

* [[Polypoid melanoma]] |

|||

File:Malignant Melanoma, vertex scalp.jpg|Melanoma, vertex scalp marked for biopsy |

|||

* [[Desmoplastic melanoma]] |

|||

File:Malignant Melanoma right medial thigh.jpg|Melanoma, right medial thigh marked for biopsy |

|||

* [[Amelanotic melanoma]] |

|||

File:Malignant Melanoma Right Posterior Shoulder.jpg|Melanoma, right posterior shoulder circled for biopsy |

|||

* [[Soft-tissue melanoma]] |

|||

File:Malignant Melanoma Left Forearm.jpg|Melanoma, left forearm marked for biopsy |

|||

File:Malignant Melanoma Left Forearm post excision.jpg|Melanoma left forearm post excision with purse-string closure |

|||

File:Melanoma in situ Right Forehead.jpg|Melanoma in situ, right forehead marked for biopsy |

|||

File:Melanoma in situ Right Forehead dermatoscope.jpg|Melanoma in situ, dermatoscope image, right forehead marked for biopsy |

|||

File:Malignant Melanoma right temple medial adjacent sebaceous hyperplasia right temple lateral.jpg|Melanoma in situ, evolving, a medial right temple with adjacent sebaceous hyperplasia, lateral |

|||

File:Malignant Melanoma in situ Left Anterior Shoulder.jpg|Melanoma in situ, left anterior shoulder marked for biopsy |

|||

File:Malignant Melanoma in situ Right Anterior Shoulder.jpg|Melanoma in situ, right anterior shoulder marked for biopsy |

|||

File:Malignant Melanoma in situ Left Upper Inner Arm.jpg|Melanoma in situ, left upper inner arm |

|||

File:Malignant Melanoma in situ Left Forearm.jpg|Melanoma in situ marked for biopsy, left forearm |

|||

File:Malignant Melanoma right upper medial back.jpg|Melanoma in situ, right upper medial back, marked for biopsy |

|||

File:Malignant Melanoma Mid Frontal Scalp.jpg|Melanoma, mid frontal scalp |

|||

File:Malignant Melanoma Left Mid Back.jpg|Melanoma, left mid-back marked for biopsy |

|||

File:Malignant Melanoma Left Mid Back Dermatoscope.jpg|Melanoma, left mid-back marked for biopsy, through dermatoscope |

|||

File:Gross pathology of melanoma metastasis.jpg|Gross pathology of melanoma metastasis, which is pigment-forming in a vast majority of cases, giving it a dark appearance |

|||

File:Histopathology of a metastatic melanoma to a lymph node.jpg|Histopathology of a metastatic melanoma to a lymph node, H&E stain, showing poorly differentiated cells |

|||

File:Histopathology of a metastatic melanoma to a lymph node, Melan-A stain.jpg|Metastatic melanoma on [[immunohistochemistry]] for [[Melan-A]], which helps in diagnosing uncertain cases |

|||

File:Immunohistochemistry stain for SOX10 in a metastatic melanoma to a lymph node.jpg|Metastatic melanoma on immunohistochemistry for [[SOX10]], another helpful stain in uncertain cases |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

===Ugly duckling=== |

|||

See also:<ref name="Bolognia">{{Cite book|author=Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. |title=Dermatology: 2-Volume Set |publisher=Mosby |location=St. Louis|year=2007 |isbn=1-4160-2999-0 }}</ref> |

|||

One method is the "[[The Ugly Duckling|ugly duckling]] sign".<ref name="pmid9828892">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mascaro JM, Mascaro JM | title = The dermatologist's position concerning nevi: a vision ranging from "the ugly duckling" to "little red riding hood" | journal = Archives of Dermatology | volume = 134 | issue = 11 | pages = 1484–1485 | date = November 1998 | pmid = 9828892 | doi = 10.1001/archderm.134.11.1484 | doi-broken-date = 2 December 2024 }} |

|||

</ref> Correlation of common lesion characteristics is made. Lesions that deviate from the common characteristics are labeled an "ugly duckling", and a further professional exam is required. The "[[Little Red Riding Hood]]" sign<ref name="pmid9828892"/> suggests that individuals with fair skin and light-colored hair might have difficult-to-diagnose [[amelanotic melanomas]]. Extra care is required when examining such individuals, as they might have multiple melanomas and severely dysplastic nevi. A dermatoscope must be used to detect "ugly ducklings", as many melanomas in these individuals resemble nonmelanomas or are considered to be "[[Wolf in sheep's clothing|wolves in sheep's clothing]]".<ref name="dermnetnz.org">{{cite web|url=http://dermnetnz.org/doctors/dermoscopy-course/introduction.html|title=Introduction to Dermoscopy|publisher=DermNet New Zealand|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090507183545/http://dermnetnz.org/doctors/dermoscopy-course/introduction.html|archive-date=7 May 2009}}</ref> |

|||

These fair-skinned individuals often have lightly pigmented or amelanotic melanomas that do not present easy-to-observe color changes and variations. Their borders are often indistinct, complicating visual identification without a dermatoscope. |

|||

Amelanotic melanomas and melanomas arising in fair-skinned individuals are very difficult to detect, as they fail to show many of the characteristics in the ABCD rule, break the "ugly duckling" sign, and are hard to distinguish from [[acne]] scarring, insect bites, [[benign fibrous histiocytoma|dermatofibromas]], or [[lentigo|lentigines]]. |

|||

===Biopsy=== |

|||