Aimee Semple McPherson: Difference between revisions

Butlerblog (talk | contribs) m Rollback edit(s) by 142.117.224.143 (talk): (from contribs) (RW 16.1) |

|||

| (729 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Canadian-American evangelist and media celebrity (1890–1944)}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=July 2023}} |

|||

{{course assignment | course = Education Program:University of Texas, Austin/History of Pentecostalism in the Americas (Spring 2015) | term = Spring 2015 }} |

{{course assignment | course = Education Program:University of Texas, Austin/History of Pentecostalism in the Americas (Spring 2015) | term = Spring 2015 }} |

||

{{very long|date=October 2013}} |

|||

{{Infobox person |

{{Infobox person |

||

| name =Aimee Semple McPherson |

| name = Aimee Semple McPherson |

||

| image = |

| image = File:LAPL ASM 1911 00024641.jpg |

||

| caption = Sister Aimee (early 1920s) |

|||

| image_size = |

|||

| caption = |

|||

| birth_name = Aimee Elizabeth Kennedy |

| birth_name = Aimee Elizabeth Kennedy |

||

| birth_date = {{Birth date|1890|10|09}} |

| birth_date = {{Birth date|1890|10|09}} |

||

| birth_place = [[Salford, Ontario]] |

| birth_place = [[Salford, Ontario]], Canada |

||

| death_date = {{Death date and age|1944|09|27|1890|10|09}} |

| death_date = {{Death date and age|1944|09|27|1890|10|09}} |

||

| death_place =[[Oakland, California]] |

| death_place = [[Oakland, California]], US |

||

| death_cause = |

|||

| resting_place = [[Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Glendale)|Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery (Glendale)]] |

| resting_place = [[Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Glendale)|Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery (Glendale)]] |

||

| residence = |

|||

| nationality = |

|||

| other_names = |

| other_names = |

||

| known_for =Founding the [[International Church of the Foursquare Gospel]] |

| known_for = Founding the [[International Church of the Foursquare Gospel|Foursquare Church]] |

||

| spouse = Robert Semple (1908–10; his death)<br />Harold McPherson (1912–21; divorced)<br />David Hutton (1931–34; divorced) |

|||

| religion = |

|||

| |

| children = [[Roberta Semple Salter]] (1910–2007)<br />[[Rolf McPherson]] (1913–2009) |

||

| children = [[Roberta Semple Salter|Roberta Star Semple]]<br/>[[Rolf McPherson]] |

|||

| parents = James Morgan Kennedy<br/>Mildred Ona Pearce |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Pentecostalism}} |

|||

'''Aimee Elizabeth Semple McPherson''' (née '''Kennedy'''; October 9, 1890 – September 27, 1944), also known as '''Sister Aimee''' or '''Sister''', was a Canadian-born [[Pentecostalism|Pentecostal]] [[Evangelism|evangelist]] and media celebrity in the 1920s and 1930s,<ref name="WVobit">Obituary ''[[Variety Obituaries|Variety]]'', October 4, 1944.</ref> famous for founding the [[Foursquare Church]]. McPherson pioneered the use of [[Broadcasting|broadcast mass media]] for wider dissemination of both religious services and appeals for donations, using radio to draw in both audience and revenue with the growing appeal of popular entertainment and incorporating stage techniques into her weekly sermons at [[Angelus Temple]], an early [[megachurch]].<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-30148022 |title=The mysterious disappearance of a celebrity preacher |work=BBC News |date=November 25, 2014 |last1=Grimley |first1=Naomi}}</ref> |

|||

In her time, she was the most publicized [[Protestantism|Protestant]] evangelist, surpassing [[Billy Sunday]] and other predecessors.<ref name="autogenerated308">{{Citation | first1 = George Hunston | last1 = Williams | first2 = Rodney Lawrence | last2 = Petersen | first3 = Calvin Augustine | last3 = Pater | title = The Contentious Triangle: Church, State, and University | publisher = Truman State University Press | year = 1999 | page = 308}}</ref><ref name="newspapers1">{{cite web |url=https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/straitstimes19310302.2.46 |type= newspaper article | title = Aimée Mcpherson in Singapore |publisher= The Straits Times|date=March 2, 1931 |page =11|access-date= November 14, 2013}}{{dead link|date=June 2023}}{{cbignore}}</ref> She conducted public [[faith healing]] demonstrations involving tens of thousands of participants.<ref>Aimee Semple McPherson Audio Tapes, http://www2.wheaton.edu/bgc/archives/GUIDES/103.htm#602 {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130724005849/http://www2.wheaton.edu/bgc/archives/GUIDES/103.htm#602 |date=July 24, 2013 }}</ref><ref>Epstein, Daniel Mark, ''Sister Aimee: The Life of Aimee Semple McPherson'' (Orlando: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1993), p. 111.<br>"The healings present a monstrous obstacle to scientific historiography. If events transpired as newspapers, letters, and testimonials say they did, then Aimée Semple McPherson's healing ministry was miraculous...The documentation is overwhelming: very sick people came to Sister Aimee by the tens of thousands, blind, deaf, paralyzed. Many were healed some temporarily, some forever. She would point to heaven, to Christ the Great Healer and take no credit for the results."</ref> McPherson's view of the United States as a nation founded and sustained by [[divine inspiration]] influenced later pastors. |

|||

'''Aimee Semple McPherson''' (October 9, 1890 – September 27, 1944), also known as '''Sister Aimee''', was a Canadian-American [[Los Angeles]]–based [[Evangelism|evangelist]] and [[Mass media|media]] [[celebrity]] in the 1920s and 1930s.<ref name="WVobit">Obituary ''[[Variety Obituaries|Variety]]'', October 4, 1944.</ref> She founded the [[International Church of the Foursquare Gospel|Foursquare Church]]. McPherson has been noted as a pioneer in the use of modern media, as she used radio to draw on the growing appeal of popular entertainment in North America and incorporated other forms into her weekly sermons at [[Angelus Temple]].<ref>http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-30148022</ref> |

|||

National news coverage focused on events surrounding her family and church members, including accusations that she fabricated [[Disappearance of Aimee Semple McPherson|her reported kidnapping]].<ref>{{cite magazine|url=http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-incredible-disappearing-evangelist-572829/ |title=The Incredible Disappearing Evangelist |magazine= Smithsonian | access-date=May 3, 2014}}</ref> McPherson's preaching style, extensive charity work and ecumenical contributions were major influences on 20th-century [[Charismatic Christianity]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.religiondispatches.org/books/529/rd10q:_aimee_semple_mcpherson,_evangelical_maverick |title= RD10Q: Aimee Semple McPherson, Evangelical Maverick |publisher= Religion Dispatches |date=September 26, 2008 |access-date=November 14, 2013}}</ref><ref name="SuttonWildfire">{{cite web |url=http://www.thefreelibrary.com/%22Between+the+refrigerator+and+the+wildfire%22%3A+Aimee+Semple+McPherson,...-a098978379 |title='Between the refrigerator and the wildfire': Aimee Semple McPherson, pentecostalism, and the fundamentalist-modernist controversy |publisher= The Free Library |access-date= November 14, 2013}}</ref> |

|||

In her time she was the most publicized Christian evangelist, surpassing [[Billy Sunday]] and her other predecessors.<ref name="autogenerated308">George Hunston Williams, Rodney Lawrence Petersen, Calvin Augustine Pater, The Contentious Triangle: Church, State, and University, Truman State University Press, 1999 p. 308</ref><ref name="newspapers1">{{cite web|url=http://newspapers.nl.sg/Digitised/Article.aspx?articleid=straitstimes19310302.2.46 |title=Newspaper Article - AIMEE McPHERSON IN SINGAPORE |publisher=Newspapers.nl.sg |date= |accessdate=2013-11-14}}</ref> She conducted public faith-healing demonstrations before large crowds; testimonies conveyed tens of thousands of people healed.<ref>Aimee Semple McPherson Audio Tapes, http://www2.wheaton.edu/bgc/archives/GUIDES/103.htm#602</ref> |

|||

<ref>Epstein, Daniel Mark , Sister Aimee: The Life of Aimee Semple McPherson (Orlando: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1993), p. 111. Note: Epstein writes "The healings present a monstrous obstacle to scientific historiography. If events transpired as newspapers, letters, and testimonials say they did, then Aimee Semple McPherson's healing ministry was miraculous.... The documentation is overwhelming: very sick people came to Sister Aimee by the tens of thousands, blind, deaf, paralyzed. Many were healed some temporarily, some forever. She would point to heaven, to Christ the Great Healer and take no credit for the results."</ref> McPherson's articulation of the United States as a nation founded and sustained by divine inspiration continues to be echoed by many pastors in churches today. News coverage sensationalized her misfortunes with family and church members; particularly inflaming accusations she had fabricated her reported kidnapping, turning it into a national spectacle.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-incredible-disappearing-evangelist-572829/ |title=The Incredible Disappearing Evangelist |publisher=Smithsonian.com |date= |accessdate=2014-05-03}}</ref> McPherson's preaching style, extensive charity work and ecumenical contributions were a major influence in revitalization of American Evangelical Christianity in the 20th century.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.religiondispatches.org/books/529/rd10q:_aimee_semple_mcpherson,_evangelical_maverick |title=RD10Q: Aimee Semple McPherson, Evangelical Maverick |publisher=Religion Dispatches |date=2008-09-26 |accessdate=2013-11-14}}</ref><ref name="SuttonWildfire">{{cite web|url=http://www.thefreelibrary.com/%22Between+the+refrigerator+and+the+wildfire%22%3A+Aimee+Semple+McPherson,...-a098978379 |title="Between the refrigerator and the wildfire": Aimee Semple McPherson, pentecostalism, and the fundamentalist-modernist controversy (1). - Free Online Library |publisher=Thefreelibrary.com |date= |accessdate=2013-11-14}}</ref> |

|||

==Biography== |

==Biography== |

||

===Early life=== |

===Early life=== |

||

McPherson was born Aimee Elizabeth Kennedy |

McPherson was born '''Aimee Elizabeth Kennedy''' in [[Salford, Ontario]], Canada, to James Morgan and Mildred Ona (Pearce) Kennedy (1871–1947).<ref>Matthew Avery Sutton, ''[http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674032538 Aimee Semple McPherson and the Resurrection of Christian America]'' (Cambridge: [[Harvard University Press]], 2007), p. 9 {{ISBN|978-0674032538}}</ref><ref name="Noll">Mark A. Noll, ''A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada'', Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, US, 1992, pp. 513–514.</ref><ref>Edith Waldvogel Blumhofer, Aimee Semple McPherson: everybody's sister (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, Inc., 1993), pp. 24, 43–44</ref> She had early exposure to religion through her mother who worked with the poor in [[Salvation Army]] [[soup kitchens]]. As a child she would play "Salvation Army" with classmates and preach sermons to dolls.<ref name="Sutton, p. 9">Sutton, p. 9</ref> |

||

As a teenager, McPherson strayed from her mother's teachings by reading novels and attending movies and dances, activities disapproved by the Salvation Army and her father's [[Methodism|Methodist]] religion. In high school, she was taught the theory of [[evolution]].<ref>Sutton, pp. 9–10</ref><ref>Epstein, pp. 28–29</ref> She began to ask questions about faith and science but was unsatisfied with the answers.<ref name="Sutton, p. 10">Sutton, p. 10</ref> She wrote to a Canadian newspaper, questioning the taxpayer-funded teaching of evolution.<ref name="Sutton, p. 10"/> This was her first exposure to fame, as people nationwide responded to her letter,<ref name="Sutton, p. 10"/> and the beginning of a lifelong anti-evolution crusade. |

|||

=== Conversion === |

=== Conversion, marriage, and family === |

||

[[File:Semples.jpeg|right|frame|Robert and Aimee Semple (1910)]] |

[[File:Semples.jpeg|right|frame|Robert and Aimee Semple (1910)]] |

||

While attending a [[revival meeting]] in 1907, McPherson met Robert James Semple, a [[Pentecostalism|Pentecostal]] [[missionary]] from Ireland.<ref>Michael Wilkinson, Peter Althouse, ''Winds from the North: Canadian Contributions to the Pentecostal Movement'', BRILL, Leiden, 2010, p. 28.</ref> She dedicated her life to Jesus and converted to Pentecostalism.<ref name="Sutton, p. 10"/> At the meeting, she became enraptured by Semple and his message. After a short courtship, they were married in an August 1908 Salvation Army ceremony. Semple supported them as a foundry worker and preached at the local Pentecostal mission. They studied the Bible together, then moved to Chicago and joined [[William Howard Durham|William Durham]]'s Full Gospel Assembly. Durham instructed her in the practice of interpretation of [[Speaking in tongues|tongues]].<ref>Edith Waldvogel Blumhofer, Aimee Semple McPherson: everybody's sister (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, Inc., 1993), pp. 79–81</ref>[[File:Harold and Aimee Semple McPherson.jpg|thumb|right|Aimee Semple and her second husband Harold McPherson. For a time Harold traveled with his wife Aimee in the "Gospel Car" as an itinerant preacher.]] |

|||

While attending a revival meeting in December 1907, Aimee met Robert James Semple, a [[Pentecostalism|Pentecostal]] [[missionary]] from [[Ireland]]. There, her faith crisis ended as she decided to dedicate her life to God and made the conversion to Pentecostalism as she witnessed the Holy Spirit moving powerfully.<ref name="Sutton, p. 10"/> |

|||

After embarking on an evangelistic tour to China, both contracted malaria. Semple also contracted dysentery, of which he died in Hong Kong. McPherson recovered and gave birth to their daughter, [[Roberta Semple Salter|Roberta Star Semple]]. Although McPherson claimed to have considered staying in China to continue Robert's work, she returned to the United States after receiving the money for a return ticket from her mother.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Krist |first=Gary |title=The Mirage Factory |publisher=Broadway Books |year=2018 |isbn=9780451496393 |location=New York |pages=145}}</ref> |

|||

=== Marriage and family === |

|||

At that same revival meeting, Aimee became enraptured not only by the message that Robert Semple gave, but with Robert himself. She decided to dedicate her life to both God and Robert, and after a short courtship, they were married on August 12, 1908 in a Salvation Army ceremony, pledging never to allow their marriage to lessen their devotion to God, affection for comrades or faithfulness in the Army. The pair's notion of "Army" was very broad, encompassing much more than just the Salvation Army. Robert supported them as a foundry worker and preached at the local Pentecostal mission. Together, they studied the Bible and became very knowledgeable.<ref>Edith Waldvogel Blumhofer, Aimee Semple McPherson: everybody's sister (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, Inc., 1993), p. 81</ref> |

|||

After her recuperation in the United States, McPherson joined her mother Mildred working with the Salvation Army. While in New York City, she met accountant Harold Stewart McPherson. They were married in 1912, moved to [[Providence, Rhode Island]], and had a son, [[Rolf McPherson|Rolf Potter Kennedy McPherson]].<ref name=":1">Krist, p. 146</ref> During this time, McPherson felt as though she denied her "calling" to go preach. Struggling with emotional distress and [[obsessive–compulsive disorder]], she would weep and pray.<ref>Sutton, p. 58</ref><ref>Epstein, pp. 72–73</ref> In 1914, she fell seriously ill with appendicitis. McPherson later stated that after a failed operation, she heard a voice asking her to go preach. After accepting the voice's challenge, she said, she was able to turn over in bed without pain. In 1915, her husband returned home and discovered that McPherson had left him and taken the children. A few weeks later, he received a note inviting him to join her in evangelistic work.<ref>Epstein, pp. 74–76</ref>[[File:LAPL ASM honymoon breakfast 00036723.jpg|thumb|left|Aimee Semple McPherson and her third husband, David L. Hutton, enjoying their honeymoon breakfast in 1931. Hutton assisted in some of McPherson's charity work before their divorce in 1934.]] |

|||

After embarking on an evangelistic tour, both contracted [[malaria]] and Robert, [[dysentery]]. Robert Semple died, whereas Aimee Semple recovered from malaria and gave birth to their daughter, [[Roberta Semple Salter|Roberta Star Semple]] as a 19-year-old widow. On board a ship returning to the United States, Aimee Semple started a Sunday school class then held other services as well, oftentimes mentioning her late husband in her sermons, attended by almost all the passengers attended. |

|||

Harold McPherson followed her to bring her home but changed his mind after seeing her preaching. He joined her in evangelism, setting up tents for revival meetings and preaching.<ref>Epstein, pp. 91, 95, 128</ref> The couple sold their house and lived out of their "gospel car". Despite his initial enthusiasm, Harold began leaving the crusade for long periods of time in the late 1910s. Initially attempting to launch his own career as a traveling evangelist, he eventually returned to Rhode Island and his secular job. The couple were divorced in 1921.<ref>Krist, p. 151</ref> |

|||

Shortly after her recuperation in the United States, Semple joined her mother Minnie working with the [[Salvation Army]]. While in [[New York City]], she met Harold Stewart McPherson, an accountant. They were married on May 5, 1912, moved to [[Rhode Island]] and had a son, [[Rolf McPherson|Rolf Potter Kennedy McPherson]] in March 1913. |

|||

McPherson remarried in 1932 to actor and musician David Hutton. After she fell and fractured her skull,<ref>Sutton, p. 172</ref> she visited Europe to recover. While there, she was angered to learn Hutton was billing himself as "Aimee's man" in his [[cabaret]] singing act and was frequently photographed with scantily clad women. Hutton's personal scandals were damaging the reputation of the Foursquare Church and its leader.<ref>Epstein, pp. 374–375</ref> McPherson and Hutton separated in 1933 and divorced in 1934. McPherson later publicly repented of the marriage for both theological<ref>Blumhofer, p. 333. Note: in 1932, after having to continuously answer questions about McPherson's marriage to Hutton, 33 Foursquare ministers thought this was too much of a distraction and seceded from the Temple and formed their own Pentecostal denomination, the Open Bible Evangelistic Association.</ref> and personal reasons<ref>Epstein, p. 434</ref> and later rejected gospel singer [[Homer Rodeheaver]] when he proposed marriage in 1935.<ref>Blumhofer, p. 333. Note: Homer Rodeheaver, former singing master for evangelist [[Billy Sunday]], was refused; even when it was suggested she married the wrong man and to try again to have a loving marriage, she responded negatively and redoubled her evangelistic efforts, forsaking personal fulfillment in relationships. McPherson knew Rodeheaver from working with him at the Angeleus Temple and he introduced her to David Hutton. In the case of Rodeheaver, however, biographer Sutton, according to Roberta Star Semple, stated McPherson liked him but not the way he kissed.</ref><ref>''Aimee May Marry Homer Rodeheaver'' (North Tonawanda, NY Evening News June 21, 1935)</ref> |

|||

During this time, McPherson felt as though she denied her "calling" to go preach. After struggling with emotional distress and OCD, she would fall to weep and pray.<ref>Sutton, p. 58</ref><ref>Epstein, pp. 72–73</ref> She felt the call to preach tug at her even more strongly after the birth of her second child Rolf. Then in 1914, she fell seriously ill, and McPherson states she again heard the persistent voice, asking her to go preach while in the holding room after a failed operation. McPherson accepted the voice's challenge, and she suddenly opened her eyes and was able to turn over in bed without pain. One spring morning in 1915, her husband returned home from the night shift to discover McPherson had left him and taken the children. A few weeks later, a note was received inviting him to join her in evangelistic work.<ref>Epstein, pp. 74–76</ref> |

|||

===Ministry=== |

|||

Her husband later followed McPherson to take her back home. When he saw her, though, preaching to a crowd, he witnessed her transformation into a radiant, lovely woman. Before long he became her fellow worker in Christ. Their house in Providence was sold and he joined her in setting up tents for revival meetings and even did some preaching himself.<ref>Epstein, pp. 91, 95, 128</ref> Throughout their journey, food and accommodations were uncertain, as they lived out of the "Gospel Car". Her husband, in spite of initial enthusiasm, wanted a life that was more stable and predicable. Eventually, he returned to Rhode Island and around 1918 had filed for separation. He petitioned for divorce, citing abandonment; the divorce was granted in 1921. |

|||

As part of Durham's Full Gospel Assembly in Chicago, McPherson became known for interpreting tongues, translating the words of people speaking in tongues. Unable to find fulfillment as a housewife, in 1913 McPherson began evangelizing, holding tent revivals across the [[sawdust trail]]. McPherson quickly amassed a large following, often having to relocate to larger buildings to accommodate growing crowds. She emulated the enthusiasm of Pentecostal meetings but sought to avoid excesses, in which participants would shout, tremble on the floor, and speak in tongues. McPherson set up a separate tent area for such displays of religious fervor, which could be off-putting to larger audiences.<ref>Epstein, p. 172</ref> |

|||

Of great influence to McPherson was Evangelist and Faith Healer [[Maria Woodworth-Etter]]. Etter had broken the glass ceiling for popular female preachers, drawing crowds of thousands, and her style influenced the Pentecostal Movement.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Warner |first=Wayne |title=Maria Woodworth-Etter: For Such a Time as This |year=2004}}</ref> The two had met in person on several occasions prior to Etter's death in 1924. |

|||

Some years later after her fame and the [[Angelus Temple]] were established in [[Los Angeles, California]], she married again on September 13, 1931 to actor and musician David Hutton, followed by much drama, after which she fainted and fractured her skull.<ref>Sutton, p. 172</ref> |

|||

In 1916, McPherson embarked on a tour of the southern United States, and again in 1918 with Mildred Kennedy. Standing on the back seat of their convertible, McPherson preached sermons over a megaphone.{{citation needed|date=May 2021}} In 1917, she started a magazine, ''Bridal Call'', for which she wrote articles about women's roles in religion; she portrayed the link between Christians and Jesus as a marriage bond. Along with taking women's roles seriously, the magazine contributed to transforming Pentecostalism into an ongoing American religious presence.<ref>''Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America'', Keller, Rosemary Skinner; Ruether, Rosemary Radford (Indiana University Press, 2006) pp. 406–407</ref> |

|||

While McPherson was away in Europe to recover, she was angered to learn Hutton was billing himself as "Aimee's man" in his [[cabaret]] singing act and was frequently photographed with scantily clad women. Hutton's much publicized personal scandals were damaging the Foursquare Gospel Church and their leader's credibility with other churches.<ref>Epstein, pp. 374–375</ref> McPherson and Hutton separated in 1933 and divorced on March 1, 1934. McPherson later publicly repented of the marriage, as wrong from the beginning, for both theological<ref>Blumhofer, p. 333. Note: in 1932, after having to continuously answer questions about McPherson's marriage to David Hutton, 33 Foursquare ministers thought this was too much of a distraction and seceded from the Temple and formed their own Pentecostal denomination, the Open Bible Evangelistic Association.</ref> and personal reasons<ref>Epstein, p. 434</ref> and therefore rejected nationally known gospel singer, [[Homer Rodeheaver]], a more appropriate suitor, when he eventually asked for her hand in 1935.<ref>Blumhofer, p. 333. Note: Homer Rodeheaver, former singing master for evangelist [[Billy Sunday]], was refused; even when it was suggested she married the wrong man and to try again to have a loving marriage, she responded negatively and redoubled her evangelistic efforts, forsaking personal fulfillment in relationships. McPherson knew Rodeheaver from working with him at the Angeleus Temple and he introduced her to David Hutton. In the case of Rodeheaver, however, biographer Sutton, according to Roberta Star Semple, stated McPherson liked him but not the way he kissed.</ref><ref>''Aimee May Marry Homer Rodeheaver'' (North Tonawanda, NY Evening News June 21, 1935)</ref> |

|||

In Baltimore in 1919 she was first "discovered" by newspapers after conducting evangelistic services at the [[Lyric Performing Arts Center|Lyric Opera House]], where she performed faith-healing demonstrations. During these events the crowds in their religious ecstasy were barely kept under control.<ref name="Sun">{{cite magazine|title= P. B. Telephone, Model No. Kx-Ts580mx, Colour - White Make: Panasonic Or Similar|magazine=Mena Report|date=15 February 2015|publisher=[[Al Bawaba]]|id = {{ProQuest|1655208322}}}}</ref>{{failed verification|date=September 2023}} Baltimore became a pivotal point for her early career.<ref>Edith Waldvogel Blumhofer, ''Aimee Semple McPherson: everybody's sister'' (Grand Rapids: [[Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing]], Inc., 1993), p. 147</ref> |

|||

===Early career=== |

|||

While married to Robert Semple, the two moved to Chicago and became part of [[William Howard Durham|William Durham]]'s Full Gospel Assembly. There, Aimee was discovered to have a unique ability in the interpretation of [[glossolalia|speaking in tongues]], translating with stylistic eloquence the otherwise indecipherable utterances of [[glossolalia]]Unable to find find fulfillment as a housewife, in 1913 McPherson began evangelizing and holding tent revivals across the Sawdust Trail in the United States and Canada. |

|||

She was ordained as an evangelist by the [[Assemblies of God USA]] in 1919.<ref>Randall Herbert Balmer, ''Encyclopedia of Evangelicalism: Revised and expanded edition'', Baylor University Press, 2004, p. 441</ref> However, she ended her association with the Assemblies of God in 1922. |

|||

After her first successful visits, she had little difficulty with acceptance or attendance. Eager converts filled the pews of local churches which turned many recalcitrant ministers into her enthusiastic supporters. Frequently, she would start a revival meeting in a hall or church and then have to move to a larger building to accommodate the growing crowds. When there were no suitable buildings, she set up a tent, which was often filled past capacity. |

|||

=== Career in Los Angeles === |

|||

She wanted to create the enthusiasm a Pentecostal meeting could provide, with its "Amen Corner" and "Halleluiah Chorus" but also to avoid its unbridled chaos as participants started shouting, trembling on the floor and speaking in tongues; all at once. McPherson organized her meetings with the general public in mind and yet did not wish to quench any who suddenly came into "the Spirit." To this end she set up a "tarry tent or room" away from the general area for any who suddenly started speaking in tongues or display any other [[Holy Ghost]] behavior the larger audience might be put off by.<ref>Epstein, p. 172</ref> |

|||

In 1918, both McPherson and her daughter Roberta contracted [[Spanish flu|Spanish influenza]]. While McPherson's case was not serious, Roberta was near death. According to McPherson, while praying over her daughter she experienced a vision in which God told her he would give her a home in California. In October 1918 McPherson and her family drove from New York to Los Angeles over two months, with McPherson preaching revivals along the way.<ref>Krist, p. 151-152</ref> McPherson's first revival in Los Angeles was held at Victoria Hall, a 1,000-seat auditorium downtown. She soon reached capacity there and had to relocate to the 3,500 capacity [[Hazard's Pavilion|Temple Auditorium]] on [[Pershing Square (Los Angeles)|Pershing Square]], where people waited for hours to enter the crowded venue.<ref>Krist, p. 154</ref><ref>Epstein, p. 151</ref> Afterwards, attendees of her meetings built a home for her family.<ref>Epstein, p. 153</ref> At this time, Los Angeles was a popular vacation destination. Rather than touring the United States, McPherson chose to stay in Los Angeles, drawing audiences from both tourists and the city's burgeoning population.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aimeemcpherson.com/ |title=Aimee McPherson |publisher=Aimee McPherson |access-date=November 14, 2013}}</ref> |

|||

For several years, she traveled and raised money for the construction of a large, domed church in [[Echo Park]], named [[Angelus Temple]], in reference to the [[Angelus]] bells and to angels.<ref name="Blumhofer p. 246">Blumhofer, p. 246</ref> Not wanting to incur debt, McPherson found a construction firm willing to work with her as funds were raised "by faith",<ref>Blumhofer, p. 244</ref> beginning with $5,000 for the foundation.<ref>More than $65,000 in 2012 dollars.</ref> McPherson mobilized diverse groups to fund and build the church, by means such as selling chairs for Temple seating.<ref>over $320 in 2012</ref><ref>Blumhofer, p. 245</ref> In his book 'Growing up in Hollywood' [[Robert Parrish]] describes in detail attending one of her services.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Parrish|first=Robert|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/3681589|title=Growing up in Hollywood|date=1976|publisher=Bodley Head|isbn=0370113128|location=London|pages=15–24|oclc=3681589}}</ref> |

|||

<!-- Deleted image removed: [[File:GospelCar.jpeg|right|frame|McPherson with her "Gospel car" (1918)]] --> |

|||

In 1916, McPherson embarked on a tour of the Southern United States in her "Gospel Car." And again later, in 1918, with her mother, Mildred Kennedy. Mildred was an important addition to McPherson's ministry and managed everything, including the money, which gave them an unprecedented degree of financial security. Their vehicle was a 1912 [[Packard]] touring car emblazoned with religious slogans. Standing on the back seat of the convertible, McPherson preached sermons over a [[megaphone]]. On the road between sermons, she would sit in the back seat typing sermons and other religious materials. She first traveled up and down the eastern United States, then went to other parts of the country. |

|||

[[File:ASM-AngelusTemple Plaque 1923 02.jpg|thumbnail|left|upright|McPherson dedicating Angelus Temple in 1923.]] |

|||

By 1917 she had started her own magazine, ''The Bridal Call'', for which she wrote many articles about women’s roles in religion; she portrayed the link between Christians and Jesus as a marriage bond. Along with taking seriously the religious role of women, the magazine contributed to transforming Pentecostalism from a movement into an ongoing American religious presence. |

|||

<ref>''Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America'', Keller, Rosemary Skinner; Ruether, Rosemary Radford (Indiana University Press, 2006) p. 406-407</ref> |

|||

Raising more money than expected, McPherson altered the plans and built a "[[megachurch]]". The endeavor cost contributors around $250,000.<ref>More than $3.2 million in 2012 dollars.</ref> Costs were kept down by donations of building materials and labor.<ref name="Blumhofer p. 246"/> The dedication took place in January 1923.<ref>George Thomas Kurian, Mark A. Lamport, ''Encyclopedia of Christianity in the United States, Volume 5'', Rowman & Littlefield, 2016, p. 1199</ref> Enrollment grew to over 10,000, and Angelus Temple was advertised as the largest single Christian congregation in the world.<ref>Thomas, Lately ''Storming Heaven: The Lives and Turmoils of Minnie Kennedy and Aimee Semple McPherson'' (Morrow, New York, 1970) p. 32.</ref> According to church records, the Temple received 40 million visitors within the first seven years.<ref>Bridal Call (Foursquare Publications, 1100 Glendale Blvd, Los Angeles.) October 1929, p. 27</ref> |

|||

While McPherson was traveling for her evangelical work, she arrived in Baltimore where she was first "discovered" by the newspapers in 1919, after a day after conducting evangelistic services at the Lyric Opera House.<ref name="Sun">{{cite web|url=http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=1655208322&sid=4&Fmt=1&clientId=41152&RQT=309&VName=HNP |title=ProQuest Login - ProQuest |publisher=Proquest.umi.com |date= |accessdate=2013-11-14}}</ref> Baltimore became one of the pivotal points for her early career.<ref>Edith Waldvogel Blumhofer, ''Aimee Semple McPherson: everybody's sister'' (Grand Rapids: [[Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing]], Inc., 1993), p. 147</ref> The crowds, in their religious ecstasy, were barely kept under control as they gave way to manifestations of "the Spirit". Moreover, her alleged faith healings now became part of the public record, and attendees began to focus on that part of her ministry over all else. McPherson considered the Baltimore Revival an important turning point not only for her ministry "but in the history of the outpouring of the Pentecostal power."<ref>Epstein, pp. 170–172</ref> |

|||

Despite her earlier rooting in Pentecostalism, her church reflected [[interdenominationalism|interdenominational]] beliefs.<ref>Edith Waldvogel Blumhofer, ''Aimee Semple McPherson: everybody's sister'', Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1993, p. 250</ref><ref name="SuttonWildfire" /><ref>Sutton, p. 335</ref> McPherson had moved away from the more extreme elements of Pentecostalism that characterised her early tent revivals—speaking in tongues and other such manifestations of religious ecstasy—which resulted in some elements of the Pentecostal establishment turning against her.<ref name=":2">Krist, p. 203</ref> In 1922 the ''Pentecostal Evangel'', the official publication of the Assemblies of God, published an article titled "Is Mrs McPherson Pentecostal?," in which they claimed McPherson had compromised her teachings in order to secure mainstream respectability.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

===Career in Los Angeles === |

|||

===Charitable work=== |

|||

In late 1918, McPherson came to Los Angeles, a move many at the time were making for the beautiful weather and frontier opportunities. Minnie Kennedy, her mother, rented the largest hall they could find, the 3,500 seat [[Philharmonic Auditorium]] (known then as Temple Auditorium). People waited for hours to get in and McPherson could hardly reach the pulpit without stepping on someone.<ref>Epstein, p. 151</ref> Afterwards, grateful attendees of her Los Angeles meetings built her a home for her family which included everything from the cellar to a canary bird.<ref>Epstein, p. 153</ref> |

|||

[[File:ASMcPherson, 1935.jpg|thumb|McPherson (left) prepares Christmas food baskets (circa 1935)]] |

|||

McPherson developed a church organization to provide for physical as well as spiritual needs. McPherson mobilized people to get involved in charity and social work, saying that "true Christianity is not only to be good but to do good." The Temple collected donations for humanitarian relief including for a Japanese disaster and a German relief fund. Men released from prison were found jobs by a "brotherhood". A "sisterhood" sewed baby clothing for impoverished mothers.<ref>Epstein, p. 249</ref> |

|||

In June 1925, after an [[1925 Santa Barbara earthquake|earthquake in Santa Barbara]] McPherson interrupted a radio broadcast to request food, blankets, clothing, and emergency supplies.<ref>Blumhofer, p. 269</ref> In 1928, after [[St. Francis Dam|a dam failed]] and the ensuing flood left up to 600 dead, McPherson's church led the relief effort.<ref>Sutton, pp. 189, 315. Note: author states over 400 dead</ref> In 1933, an [[1933 Long Beach earthquake|earthquake struck and devastated Long Beach.]] McPherson quickly arranged for volunteers offering blankets, coffee, and doughnuts.<ref>Blumhofer, p. 348. <!-- Note: author indicates 1934 but probably a typo --></ref> McPherson persuaded fire and police departments to assist in distribution. Doctors, physicians, and dentists staffed her free clinic that trained nurses to treat children and the elderly. To prevent disruption of electricity service to homes of overdue accounts during the winter, a cash reserve was set up with the utility company.<ref>Epstein, p. 370</ref><ref>Sutton, p. 316</ref> |

|||

At this time, Los Angeles had become a popular vacation spot. Rather than touring the United States to preach her sermons, McPherson stayed in [[Los Angeles]], drawing audiences from a population which had soared from 100,000 in 1900 to 575,000 people in 1920, and often included many visitors.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aimeemcpherson.com/ |title=Aimee McPherson |publisher=Aimee McPherson |date= |accessdate=2013-11-14}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:LAPL ASM Commissary Exterior 00075061.jpg|thumb|left|Men wait in line at McPherson (Hutton)'s Angelus Temple Free Dining Hall & Commissary on Temple St.]] |

|||

Drawing from her childhood experience with the Salvation Army, in 1927 McPherson opened a commissary at Angelus Temple offering food, clothing, and blankets. She became active in creating soup kitchens, free clinics, and other charitable activities during the [[Great Depression]], feeding an estimated 1.5 million. Volunteer workers filled commissary baskets with food and other items, as well as Foursquare Gospel literature.<ref name="Sutton, p. 317">Sutton, p. 317</ref> When the government shut down the free school-lunch program, McPherson took it over. Her giving "alleviated suffering on an epic scale".<ref>Epstein, p. 369</ref> [[File:UCLA ASM charity Men in line.jpg|thumb|right|Line of unemployed men getting meals at dining hall run by McPherson, 1932.]] |

|||

Wearied by constant traveling and having nowhere to raise a family, McPherson had settled in Los Angeles, where she maintained both a home and a church. McPherson believed that by creating a church in Los Angeles, her audience would come to her from all over the country. This, she felt, would allow her to plant seeds of the Gospel and tourists would take it home to their communities, still reaching the masses. For several years she continued to travel and raise money for the construction of a large, domed church building at 1100 Glendale Blvd. in the [[Echo Park, Los Angeles, California|Echo Park]] area of Los Angeles. The church would be named [[Angelus Temple]], reflecting the Roman Catholic tradition of the [[Angelus bell]], calling the faithful to prayer and as well its reference to the angels.<ref name="Blumhofer p. 246">Blumhofer, p. 246</ref> Not wanting to take on debt, McPherson located a construction firm which would work with her as funds were raised "by faith."<ref>Blumhofer, p. 244</ref> She started with $5,000.<ref>More than $65,000 in 2012 dollars.</ref> The firm indicated it would be enough to carve out a hole for the foundation. |

|||

As McPherson refused to distinguish between the "deserving" and the "undeserving," her commissary became known as an effective and inclusive aid institution,<ref name="Sutton, p. 317" /> assisting more families than other public or private institutions. Because her programs aided nonresidents such as migrants from other states and Mexico, she ran afoul of California state regulations. Though temple guidelines were later officially adjusted to accommodate those policies, helping families in need was a priority, regardless of their place of residence.<ref>Sutton, p. 195</ref> |

|||

McPherson began a campaign in earnest and was able to mobilize diverse groups of people to help fund and build the new church. Various fundraising methods were used such as selling chairs for Temple seating at US $25<ref>over US $320 in 2012</ref> apiece. In exchange, "chairholders" got a miniature chair and encouragement to pray daily for the person who would eventually sit in that chair. Her approach worked to generate enthusiastic giving and to create a sense of ownership and family among the contributors.<ref>Blumhofer, p. 245</ref> |

|||

==Ministry== |

|||

Raising more money than she had hoped, McPherson altered the original plans, and built a "megachurch" that would draw many followers throughout the years. The endeavor cost contributors around $250,000<ref>More than $3.2 million in 2012 dollars.</ref> in actual money spent. However, this price was low for a structure of its size. Costs were kept down by donations of building materials and volunteer labor.<ref name="Blumhofer p. 246"/> McPherson sometimes quipped when she first got to California, all she had was a car, ten dollars<ref>over US $130 in 2012.</ref> and a tambourine.<ref name="Blumhofer p. 246"/> |

|||

=== Style of ministry === |

|||

McPherson intended the Angelus Temple as both a place of worship and an ecumenical center for persons of all Christian faiths to meet and build alliances. A wide range of clergy and laypeople to include Methodists, Baptists, the Salvation Army, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, Adventists, Quakers, Roman Catholics, Mormons and secular civic leaders came to the Angelus Temple. They were welcomed and many made their way to her podium as guest speakers.<ref name="SuttonWildfire"/> Eventually, even Rev. [[Robert P. Shuler]], a once robust McPherson critic, was featured as a guest preacher.<ref>Sutton, p. 335</ref> |

|||

In August 1925, McPherson [[Air charter|chartered a plane]] to Los Angeles to give her Sunday sermon. Aware of the opportunity for publicity, she arranged for followers and press at the airport. The plane failed after takeoff and the landing gear collapsed, sending the nose of the plane into the ground. McPherson used the experience as the narrative of an illustrated sermon called "The Heavenly Airplane",<ref name="Sutton, p.72">Sutton, p. 72</ref> featuring the devil as pilot, sin as the engine, and temptation as propeller. |

|||

[[File:WVBPC Angelus Temple d3e11459.jpg|thumb|left| [[Angelus Temple]], completed in 1923, is the center of the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel founded by McPherson. In 1992, Angelus Temple was designated a National Historic Landmark, and remains in use.]] |

|||

On another occasion, she described being pulled over by a police officer, calling the sermon "Arrested for [[Speed limit|Speeding]]". Dressed in a [[Traffic police|traffic cop's uniform]], she sat in a police motorcycle and blared the siren.<ref name="Sutton, p.72"/> One author in attendance wrote that she drove the motorcycle across the access ramp to the pulpit, slammed the brakes, and raised a hand to shout "Stop! You're speeding to Hell!"<ref>Bach, Marcus, ''They Have Found a Faith'', (The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Indianapolis / New York, 1946) p. 59</ref> |

|||

McPherson employed a small group of artists, electricians, decorators, and carpenters, who built sets for each service. Religious music was played by an orchestra. McPherson also worked on elaborate sacred operas. One production, ''The Iron Furnace'', based on the Exodus story, saw Hollywood actors assist with obtaining costumes.{{citation needed|date=May 2021}} |

|||

Because Pentecostalism was not popular in the U.S. during the 1920s, McPherson avoided the label. She did [[glossolalia|speaking-in-tongues]] and [[faith healing]], but kept to a minimum in sermons to appease mainstream audiences. She also kept a museum of discarded medical fittings from persons faith healed during her services which included crutches, wheelchairs, and other paraphernalia. As evidence of her early influence by the [[Salvation Army]], McPherson adopted a theme of "lighthouses" for the satellite churches, referring to the parent church as the "Salvation Navy." This was the beginning of McPherson working to plant Foursquare Gospel churches around the country. |

|||

[[File:LAPL AngelusTempleInterior00034787.jpg|thumb|right|McPherson surrounded by choirs at Angelus Temple for a musical requiem in 1929.]] |

|||

Though McPherson condemned theater and film as the devil's workshop, its techniques were co-opted. She became the first woman evangelist to adopt cinematic methods<ref>Sutton, p. 74</ref> to avoid dreary church services. Serious messages were delivered in a humorous tone. Animals were frequently incorporated. McPherson gave up to 22 sermons a week, including lavish Sunday night services so large that extra [[Tram|trolleys]] and police were needed to help route the traffic through Echo Park.<ref>Epstein, p. 252</ref> To finance the Temple and its projects, collections were taken at every meeting.<ref name="dollartimes1">{{cite web|url = http://www.dollartimes.com/calculators/inflation.htm|title = Inflation Calculator|publisher = DollarTimes.com|access-date = November 14, 2013}}</ref><ref>$1 of 1920s to 1930s dollars would be worth around US $11–13 in 2013. See subsequent cites for inflation calculator links.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl?cost1=1.00&year1=1930&year2=2012 |title=CPI Inflation Calculator |publisher=Data.bls.gov |access-date=November 14, 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.davemanuel.com/inflation-calculator.php|title=Inflation Calculator|website=DaveManuel.com|access-date=August 13, 2019}}</ref> |

|||

===Style of Ministry === |

|||

McPherson preached a conservative gospel but used progressive methods, taking advantage of radio, movies, and stage acts. She attracted some women associated with modernism, but others were put off by the contrast between her message and her presentation.{{Citation needed|date=May 2021}} |

|||

In August 1925 and away from Los Angeles, McPherson decided to charter a plane so she would not miss giving her Sunday sermon. Aware of the opportunity for publicity, she arranged for at least two thousand followers and members of the press to be present at the airport. The plane failed after takeoff and the landing gear collapsed, sending the nose of the plane into the ground. McPherson boarded another plane and used the experience as the narrative of an illustrated Sunday sermon called "The Heavenly Airplane".<ref name="Sutton, p.72">Sutton, p. 72</ref> The stage in Angelus Temple was set up with two miniature planes and a skyline that looked like Los Angeles. In this sermon, McPherson described how the first plane had the devil for the pilot, sin for the engine, and temptation as the propeller. The other plane, however, was piloted by Jesus and would lead one to the Holy City (the skyline shown on stage). The temple was filled beyond capacity. |

|||

[[File:LAPL ASM Performance00021729.jpg|thumb|left|McPherson and a group of tambourine players leading a service at Angelus Temple. She produced innovative weekly dramas illustrating religious themes.]] |

|||

The battle between fundamentalists and modernists escalated after World War I.<ref>Epstein, pp. 79–80</ref> Fundamentalists generally believed their faith should influence every aspect of their lives. Despite her modern style, McPherson aligned with the fundamentalists in seeking to eradicate modernism and secularism in homes, churches, schools, and communities.<ref name="Epstein, p. 156">Epstein, p. 156</ref> |

|||

On another occasion, she described being pulled over by a police officer, calling the sermon "Arrested for [[Speed limit|Speeding]]". Dressed in a traffic cop's uniform, she sat in the saddle of a police motorcycle, earlier placed on the stage, and revved the siren.<ref name="Sutton, p.72"/> One author in attendance, insisted she actually drove the motorcycle, with its deafening roar, across the access ramp to the pulpit, slammed on the brakes, then raised a white gloved hand to shout "Stop! You're speeding to Hell!"<ref>Bach, Marcus, They Have Found a Faith, (The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Indianapolis / New York, 1946) p. 59</ref> Since McPherson gave some of her sermons more than once, and with variations, the possibility existed both versions might be true. |

|||

The appeal of McPherson's revival events from 1919 to 1922 surpassed any touring event of theater or politics in American history.<ref name="Epstein, p. 156"/> She broke attendance records recently set by [[Billy Sunday]]<ref name="autogenerated308"/> and frequently used his temporary tabernacle structures to hold her roving revival meetings. One such event was held in a boxing ring, and throughout the boxing event, she carried a sign reading "knock out the Devil". In [[San Diego, California|San Diego]] the city called in a detachment of [[United States Marines|Marines]] to help police control a revival crowd of over 30,000 people.<ref>Epstein, pp. 209-210</ref> |

|||

McPherson employed a small group of artists, electricians, decorators, and carpenters who built the sets for each Sunday's service. Religious music was played by an orchestra. McPherson also worked on elaborate sacred operas. One production, ''The Iron Furnace'', based on the book of Exodus, told of God’s deliverance as the Israelites fled slavery in Egypt. Some Hollywood movie stars even assisted with obtaining costumes from local studios. The cast was large, perhaps as many as 450 people but so elaborate and expensive, it was presented only one time. Rehearsals for the various productions were time consuming and McPherson "did not tolerate any nonsense." Though described as "always kind and loving," McPherson demanded respect regarding the divine message the sacred operas and her other works were designed to convey.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.foursquare.org/news/article/lessons_i_learned_from_sister_aimee |title=Lessons I Learned From Sister Aimee | Foursquare Legacy | The Foursquare Church |publisher=Foursquare.org |date= |accessdate=2013-11-14}}</ref> |

|||

== Faith healing ministry == |

|||

Even though McPherson condemned theater and film as the devil's workshop, its secrets and effects were co-opted. She became the first woman evangelist to adopt the whole technique of the moving picture star.<ref>Sutton, p. 74</ref> McPherson desired to avoid the dreary church service where by obligation parishioners would go to fulfill some duty by being present in the pew. She wanted a sacred drama that would compete with the excitement of vaudeville and the movies. The message was serious, but the tone more along the lines of a humorous musical comedy. Animals were frequently incorporated and McPherson, the once farm girl, knew how to handle them. McPherson gave up to 22 sermons a week and the lavish Sunday night service attracted the largest crowds, extra [[Tram|trolleys]] and police were needed to help route the traffic through Echo Park to and from Angelus Temple.<ref>Epstein, p.252</ref> To finance the Angelus Temple and its projects, collections were taken at every meeting, often with the admonishment, "no coins, please".<ref name="dollartimes1">{{cite web|url = http://www.dollartimes.com/calculators/inflation.htm|title = Inflation Calculator|publisher = DollarTimes.com|date = |accessdate = 2013-11-14}}</ref><ref>$1 of 1920's to 1930's dollars would be worth around US $11–13 in 2013. See subsequent cites for inflation calculator links.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl?cost1=1.00&year1=1930&year2=2012 |title=CPI Inflation Calculator |publisher=Data.bls.gov |date= |accessdate=2013-11-14}}</ref><ref>http://www.davemanuel.com/inflation-calculator.php></ref> |

|||

McPherson's ability to draw crowds was greatly assisted by her faith healing presentations. According to Nancy Barr Mavity, an early McPherson biographer, the evangelist claimed that when she laid hands on sick or injured persons, they got well because of the power of God in her.<ref>Mavity, Nancy Barr "Sister Aimee;" (Doubleday, Doran, Inc., 1931) pp. 47–48</ref> During a 1916 revival in New York, a woman in advanced stages of rheumatoid arthritis was brought to the altar by friends. McPherson laid hands on her and prayed, and the woman apparently walked out of the church without crutches. McPherson's reputation as a faith healer grew as people came to her by the tens of thousands.<ref>Epstein 1993, pp. 107–111</ref> McPherson's faith-healing practices were extensively covered in the news and were a large part of her early-career success.<ref>Epstein, p. 57</ref> Over time, though, she largely withdrew from faith-healing, but still scheduled weekly and monthly healing sessions which remained popular until her death. |

|||

McPherson preached a conservative gospel but used progressive methods, taking advantage of radio, movies, and stage acts. Advocacy for women's rights was on the rise, including women's suffrage through the [[Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution|19th Amendment]]. She attracted some women associated with modernism, but others were put off by the contrast between her different theories. By accepting and using such new media outlets, McPherson helped integrate them into people’s daily lives. Sister McPherson used the media to her advantage as she became the "first modern celebrity preacher."<ref>Saunders, Nathan. “Spectacular Evangelist: Aimee Semple McPherson in the Fox Newsreel.” The Moving Image: The Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists 14, no. 1 (April 1, 2014): 71–90. doi:10.5749/movingimage.14.1.0071. </ref> |

|||

In 1919, Harold left her as he did not enjoy the travelling lifestyle. Her mother then joined her and the children on tour. She began her faith-healing work the same year. |

|||

The battle between fundamentalists and modernists escalated after [[World War I]], with many modernists seeking less conservative religious faiths.<ref>Epstein, pp. 79–80</ref> Fundamentalists generally believed their religious faith should influence every aspect of their lives. McPherson sought to eradicate modernism and secularism in homes, churches, schools, and communities. She developed a strong following in what McPherson termed "the Foursquare Gospel" by blending contemporary culture with religious teachings. McPherson was entirely capable of sustaining a protracted intellectual discourse as her Bible students and debate opponents will attest. But she believed in preaching the gospel with simplicity and power, so as to not confuse the message. Her distinct voice and visual descriptions created a crowd excitement "bordering on hysteria."<ref name="Epstein, p. 156">Epstein, p. 156</ref> |

|||

McPherson said she experienced several of her own personal faith healing incidents. One occurred in 1909, when her broken foot was mended, an event that served to introduce her to the possibilities of the healing power of faith.<ref>{{harvnb|Epstein|1993|p=58}}</ref> Another was an unexpected recovery from an operation in 1914, where hospital staff expected her to die.<ref>{{harvnb|Epstein|1993|p=74}}</ref> In 1916, before a gathered revival tent crowd, Aimee experienced swift rejuvenation of blistered skin from a serious flash burn caused by a lamp that had exploded in her face.<ref>{{harvnb|Epstein|1993|p=119}}</ref> |

|||

The appeal of McPherson's thirty or so revival events from 1919 to 1922 surpassed any touring event of theater or politics ever presented in American history. "Neither Houdini nor Teddy Roosevelt had such an audience nor PT Barnum."<ref name="Epstein, p. 156"/> Her one to four-week meetings typically overflowed any building she could find to hold them. She broke attendance records recently set by [[Billy Sunday]]<ref name="autogenerated308"/> and frequently used his temporary tabernacle structures to hold some of her meetings in. Her revivals were often standing-room only. One such revival was held in a boxing ring, with the meeting before and after the match. Throughout the boxing event, she walked about with a sign reading "knock out the Devil." In [[San Diego, California]], the city called in the [[National Guard of the United States|National Guard]] and other branches of the armed forces to control a revival crowd of over 30,000 people. She became one of the most photographed persons of her time. She enjoyed the publicity and quotes on almost every subject were sought from her by journalists. |

|||

McPherson's first reported successful public faith healing session of another person was in [[Corona, New York]], on [[Long Island]], in 1916. A young woman in the advanced stages of [[rheumatoid arthritis]] was brought to the altar by friends just as McPherson preached "Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today and forever". McPherson laid her hands upon the woman's head, and the woman was able to leave the church that night without crutches.<ref>{{harvnb|Epstein|1993|pp=107–111}}</ref> According to Mildred Kennedy the crowds at the revivals were easily twice as large as McPherson reported in her letters and the healings were not optimistic exaggerations. Kennedy said she witnessed visible cancers disappear, the deaf hear, the blind see, and the disabled walk.<ref>Robinson, Judith (2006) Working Miracles: The Drama and Passion of Aimee Semple McPherson. Altitude Publishing; epub, Chapter 4, para. end of section, {{ISBN|9781554390854}}</ref>[[File:SDHS ASM Spreckels 80 7195.jpg|250px|thumb|left|alt=Aimee Semple McPherson conducting a healing ceremony at the Spreckels Organ Pavilion in 1921. Police support, along with U.S. Marines and Army personnel, helped manage traffic and the estimated 30,000 people who attended.|Aimee Semple McPherson conducting a healing ceremony at the Spreckels Organ Pavilion in 1921. Police support along with U.S. Marines and Army personnel helped manage traffic and the estimated 30,000 people who attended.]] |

|||

Her faith-healing demonstrations gained her unexpected allies. When a [[Romani people|Romani]] tribe king and his mother stated they were faith-healed by McPherson, thousands of others came to her as well in caravans from all over the country and were converted. The infusion of crosses and other symbols of Christianity alongside Romani [[astrology]] charts and [[crystal ball]]s was the result of McPherson's influence.<ref>Epstein, p. 239</ref> Prizing gold and loyalty, the Romani repaid her in part, with heavy bags of gold coin and jewels, which helped fund the construction of the new Angelus Temple.<ref>Epstein, p. 241</ref> In [[Wichita, Kansas|Wichita]], Kansas, in May 29, 1922, where heavy perennial thunderstorms threatened to rain out the thousands who gathered there, McPherson interrupted the speaker, raised her hand to the sky and prayed, "let it fall (the rain) after the message has been delivered to these hungry souls". The rain immediately stopped, an event reported the following day by the ''[[Wichita Eagle]]'' on May 30: "Evangelist's Prayers Hold Big Rain Back,"<ref>Blumhofer, p. 184</ref> For the gathered Romani, it was a further acknowledgement "of the woman's power".<ref>Epstein, p. 240</ref> |

|||

=== Spreckels Organ Pavilion (1921) === |

|||

===International Church of the Foursquare Gospel=== |

|||

In late January 1921 McPherson conducted a healing ceremony at the [[Spreckels Organ Pavilion]] in [[Balboa Park (San Diego)|Balboa Park]] in [[San Diego|San Diego, California]]. Police, U.S. Marines, and Army personnel helped manage traffic and the estimated 30,000 people who attended.<ref name="Edith Waldvogel Blumhofer 1993 pp.160- 161">{{cite book |last=Waldvogel Blumhofer |first=Edith |title=Aimee Semple McPherson: everybody's sister |date=1993 |publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, Inc. |location=Grand Rapids |pages=160–161}}</ref> She had to move to the outdoor site after the audience grew too large for the 3,000-seat Dreamland Boxing Arena. |

|||

[[File:Postcard-los-angeles-angelus-temple.png|thumb|right|Angelus Temple in Echo Park, Los Angeles, with radio towers.]] |

|||

During the engagement, a woman [[Paralysis|paralyzed]] from the waist down from was presented for faith healing. McPherson feared she would be run out of town if this healing did not manifest, due to previous demonstrations that had occurred at smaller events of hers. McPherson prayed and laid hands on her, and the woman got up out of her wheelchair and walked.<ref>{{harvnb|Epstein|1993|pp=210–211}}</ref> Other unwell persons came to the platform McPherson occupied, though not all were cured.<ref name="Smith">{{cite news |last=Smith |first=Jeff |date=September 16, 2009 |title=Unforgettable: When Sister Aimee Came to Town – Part 2 |work=San Diego Reader |url=http://www.sandiegoreader.com/news/2009/sep/16/when-sister-aimee-came-town---part-2/ |access-date=November 14, 2013}}</ref> |

|||

Eventually, the McPherson's church evolved into its own denomination and became known as the [[International Church of the Foursquare Gospel]]. The new denomination focused on the nature of Christ's character: that he was Savior, baptizer with the Holy Spirit, healer, and coming King. There were four main beliefs: the first being Christ's ability to transform individuals' lives through the act of salvation; the second focused on a holy baptism which includes receiving power to glorify and exalt Christ in a practical way; the third was divine healing, newness of life for both body and spirit; and the fourth was gospel-oriented heed to the pre-millennial return of Jesus Christ. |

|||

Due to the demand for her services, her stay was extended. McPherson prayed for hours without food or stopping for a break. At the end of the day, she was taken away by her staff, dehydrated and unsteady with fatigue. McPherson wrote of the day, "As soon as one was healed, she ran and told nine others, and brought them too, even telegraphing and rushing the sick on trains".<ref name="Smith" /> Originally planned for two weeks in the evenings, McPherson's Balboa Park revival meetings lasted over five weeks and went from dawn until dusk.<ref>{{harvnb|Epstein|1993|pp=209–210}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Blumhofer |first=Edith L. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xgrxp-5mG44C&pg=PA156 |title=Aimee Semple McPherson: Everybody's Sister |date=2003 |publisher=William B. Eerdmans Publishing |isbn=0-8028-3752-2 |edition=reprint |location=Grand Rapids, Michigan |pages=156–164 |orig-year=1993}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:ASM-AngelusTemple Plaque 1923 02.jpg|thumbnail|left]] |

|||

=== 1921–1922 === |

|||

McPherson published the weekly ''Foursquare Crusader'', along with her monthly magazine, ''Bridal Call''. She began broadcasting on radio in the early 1920s. McPherson was one of the first women to preach a radio sermon. With the opening of Foursquare Gospel-owned [[KEIB|KFSG]] on February 6, 1924, she became the second woman granted a broadcast license by the [[Department of Commerce]], the federal agency that supervised [[broadcasting]] in the early 1920s.<ref>(The first woman to receive a broadcasting license was Mrs. Marie Zimmerman of [[Vinton, Iowa]], in August 1922. See Von Lackum, Karl C. “Vinton Boasts Only Broadcasting Station in U.S. Owned By Woman”, ''Waterloo Evening Courier'', Iowa, October 14, 1922, p. 7.</ref>) |

|||

At a revival meeting in August 1921, in San Francisco, journalists posing as scientific investigators diverted healing claimants as they descended from the platform and "cross-examined as to the genuineness of the cure." Concurrently, a group of doctors from the [[American Medical Association]] in San Francisco secretly investigated some of McPherson's local revival meetings. The subsequent AMA report stated McPherson's healing was "genuine, beneficial and wonderful". This also was the tone of press clippings, testimonials, and private correspondence in regards to the healings.<ref>Robinson, James Divine Healing: The Years of Expansion, 1906–1930: Theological Variation in the Transatlantic World (Eugene, Oregon: Pickwick Publications, 2014), p. 220</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Epstein|1993|p=233}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:ASM_Stretcher_Day_Revival_Denver.jpeg|350px|thumb|right|alt=Stretcher Day at Revival in Municipal Auditorium at Denver, Colorado, 1921. The event attracted a capacity crowd of 12,000 attendees. People were carried in on cots, stretchers, chairs and beds; and awaited McPherson to pray over them for healing.| Stretcher Day at Revival in Municipal Auditorium at Denver, Colorado, 1921. The event attracted a capacity crowd of 12,000 attendees. People were carried in on cots, stretchers, chairs and beds; and awaited McPherson to pray over them for healing.<ref>Edith Waldvogel Blumhofer, Aimee Semple McPherson: everybody's sister (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, Inc., 1993), pp. 168–172</ref>]]In 1921 during the Denver campaign, a Serbian [[Romani people|Romani]] tribe chief, Dewy Mark and his mother stated they were faith-healed by McPherson of a respiratory illness and a "fibroid tumor." For the next year the Romani king, by letter and telegram urged all other Romani to follow McPherson and "her wonderful Lord Jesus." Thousands of others from the Mark and Mitchell tribes came to her in caravans from all over the country and were converted with healings being reported from a number of them. Funds in gold, taken from necklaces, other jewelry, and elsewhere, were given by Romani in gratitude and helped fund the construction of the new Angelus Temple. Hundreds of people regularly attended services at the newly built Angeles Temple in Los Angeles. Many Romani followed her to a revival gathering in [[Wichita, Kansas]], and on May 29, 1922, heavy thunderstorms threatened to rain out the thousands who gathered there. McPherson interrupted the speaker, raised her hand to the sky, and prayed, "if the land hath need of it, let it fall (the rain) after the message has been delivered to these hungry souls". To the crowd's surprise, the rain immediately stopped and many believed they witnessed a miracle. The event was reported the following day by the ''[[Wichita Eagle]].'' For the gathered Romani, it was a further acknowledgement "of the woman's power". Up until that time, the Romani in the US were largely unreached by Christianity. The infusion of crosses and other symbols of Christianity alongside Romani [[astrology]] charts and [[crystal ball]]s was the result of McPherson's influence.<ref>Epstein, pp. 239–240</ref><ref>Blumhofer, pp. 179–180, 185</ref> |

|||

McPherson racially integrated her tent meetings and church services. On one occasion, as a response to McPherson's ministry and Angelus Temple being integrated, [[Ku Klux Klan]] members were in attendance, but after the service hoods and robes were found on the ground in nearby [[Echo Park, Los Angeles, California|Echo Park]].<ref>Blumhofer, pp. 275–277</ref> She is also credited with helping many Hispanic ministries in Los Angeles.<ref name=nyorker>{{cite news|last=Updike|first=John|title=Famous Aimee: The life of Aimee Semple McPherson|url=http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/books/2007/04/30/070430crbo_books_updike?currentPage=all|newspaper=[[The New Yorker]]|date=30 April 2007}}</ref> |

|||

In 1922, McPherson returned for a second tour in the Great Revival of Denver<ref>{{harvnb|Epstein|1993|p=237}}</ref> and asked about people who have stated healings from the previous visit. Seventeen people, some well-known members of the community, testified, giving credence to the audience of her belief that "healing still occurred among modern Christians".<ref>{{harvnb|Sutton|2009|pp=17–18}}</ref> |

|||

McPherson traveling about the country holding widely popular revival meetings and filling local churches with converts was one thing, settling permanently into their city caused concern among some local Los Angeles churches. Even though she shared many of their [[Fundamentalism|fundamentalist beliefs:]] divine inspiration of the Bible, the classical [[Trinity]], virgin birth of Jesus, historical reality of Christ's miracles, bodily resurrection of Christ and the atoning purpose of his crucifixion; the presentation of lavish sermons, and an effective faith healing ministry presented by a female divorcee who thousands adored and newspapers continuously wrote of, was unexpected. Moreover, the Temple, especially the women, had a look and style uniquely theirs. They would emulate McPherson's style and dress, and a distinct Angeleus Temple uniform came into existence, a white dress with a navy blue cape thrown over it.<ref>Epstein, p. 275</ref> Men were more discreet, wearing suits. Her voice, projected over the powerful state-of-the-art KFSG radio station and heard by hundreds of thousands, became the most recognized in the western United States.<ref>Epstein, p. 264</ref> |

|||

In 1928, when two clergymen were preaching against her and her "divine healing," McPherson's staff assembled thousands of documents and attached to each of them photos, medical certificates, X-rays and testimonies of healing. The information gathered was used to silence the clergymens' accusations and was also later accessed by some McPherson biographers.<ref>Dicken, Janice Take Up Thy Bed and Walk": Aimee Semple McPherson and Faith-Healing; Canadian Bulletin of Medical History CBMH/BCHM / Volume 17: Spring 2000 / p. 149 (https://www.utpjournals.press/doi/pdf/10.3138/cbmh.17.1.137)</ref><ref>Epstein 1993, p. ix</ref> |

|||

[[File:ASM-AngelusTemple Sermon 1923 01.jpg|thumbnail|left|McPherson preaching at the newly built Angelus Temple in 1923. Her messages showcased the love of God, redemption and the joys of service and heaven; contrasting sharply with the fire and brimstone style of sermon delivery popular with many of her peers.]] Her illustrated sermons attracted criticism from some clergy members because they thought it turned the gospel message into mundane theater and entertainment. Divine healing, as McPherson called it, was claimed by many pastors to be a unique dispensation granted only for [[Apostolic Age|Apostolic times]]. Reverend [[Robert P. Shuler]] published a pamphlet entitled ''McPhersonism'', which purported that her "most spectacular and advertised program was out of harmony with God's word."<ref>Schuler, Robert P. ''McPhersonism: a study of healing cults and modern day tongues movements'', January, 1924, p. 3</ref> Debates such as the [[Ben M. Bogard|Bogard]]-McPherson Debate in 1934<ref>[[Ben M. Bogard]], ''Bogard-McPherson debate : McPhersonism, Holy Rollerism, miracles, Pentecostalism, divine healing : a debate with both sides presented fully'', ([[Little Rock, Arkansas]]: Ben M. Bogard, 1934)</ref> drew further attention to the controversy, but none could really argue effectively against McPherson's results.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://healingandrevival.com/BioCSPrice.htm |title=Biography of Charles S. Price |publisher=Healingandrevival.com |date=1947-03-08 |accessdate=2013-11-14}}</ref><ref>http://www.earstohear.net/Price/testimony.html Note: Divine Healing was a contentious theological area of McPherson's ministry, but she was not alone. Other pastors already had a ministry with alleged successful healings such as James Moore Hickson (1868–1933), an Episcopalian of international renown. Another pastor, Dr. Charles S Price (1887–1947), went to a series of McPherson revival meetings in San Jose California, to expose the fraud. Instead he himself was converted and preached McPherson's version of Christianity to his congregation. Reports of purported faith healings began to take place. Price went on to preach as a traveling evangelist who converted tens of thousands along with many instances of miraculous divine healings allegedly occurring.</ref><ref>Epstein, pp. 185, 240</ref> |

|||

In later years, McPherson identified other individuals with a faith healing gift. During regular healing sessions she worked among them but over time she mostly withdrew from the faith healing aspect of her services, as she found that it was overwhelming<ref>{{harvnb|Epstein|1993|p=111}}</ref> other areas of her ministry. |

|||

The new developing [[Assemblies of God]] denomination, Pentecostal as McPherson was, for a time worked with her, but they encouraged separation from established Protestant faiths. McPherson resisted trends to isolate as a denomination and continued her task of coalition building among evangelicals. McPherson worked hard to attain ecumenical vision of the faith and while she participated in debates, avoided pitched rhetorical battles that divided so many in Christianity. She wanted to work with existing churches on projects and to share with them her visions and beliefs. Assisting in her passion was the speedy establishment of LIFE Bible College adjacent to the Angeles Temple. Ministers trained there were originally intended to go nationally and worldwide to all denominations and share her newly defined "Foursquare Gospel." A well known Methodist minister, Frank Thompson, who never had the Pentecostal experience,<ref>"Spiritual gifts" given by the Holy Spirit, of which the most well known is speaking in "tongues" the spontaneously speaking in a language unknown to the speaker;, also known as [[Glossolalia]]. Other gifts include translating the said "tongues."</ref> was persuaded to run the college; and he taught the students the doctrine of [[John Wesley]]. McPherson and others, meanwhile, infused them with Pentecostal ideals. Her efforts eventually led Pentecostals, which were previously unconventional and on the periphery of Christianity, into the mainstream of American evangelicalism.<ref name="SuttonWildfire"/> |

|||

Scheduled healing sessions nevertheless remained highly popular with the public until her death in 1944. One of these was Stretcher Day, which was held behind the Angeles Temple parsonage once every five or six weeks. This was for the most serious of the infirm who could only be moved by "stretcher." Ambulances would arrive at the parsonage and McPherson would enter, greet the patient and pray over them. On Stretcher Day, so many ambulances were in demand that Los Angeles area hospitals and medical centers had to make it a point of reserving a few for other needs and emergencies.<ref>DVD God's Generals, Vol. 7: Aimee Semple McPherson; Whitaker House, June 17, 2005, 36:10–37:34, {{ASIN|B0009ML1VQ}}</ref> |

|||

McPherson herself steadfastly declined to publicly criticize by name any individual with rare exceptions, but those who were converted in her services were not so careful. The testimonies of former prostitutes, drug addicts and others, from stage or broadcast over the radio, frequently revealed the names and locations concerning their past illegal activities. These revelations angered many and McPherson often received hostile letters and death threats. An alleged plot to kidnap her and detailed in the ''[[Los Angeles Times]]'' was foiled in September, 1925.<ref>Epstein, p. 300</ref> |

|||

=== McPherson's faith healing in the media === |

|||

===Faith Healing Ministry === |

|||

McPherson's [[faith healing|faith-healing]] demonstrations were extensively covered in the news media and were a large part of her early career legacy.<ref>{{harvnb|Epstein|1993|p=57}}</ref> James Robinson, an author on Pentecostalism, diverse healing and holiness traditions, writes: "In terms of results, the healings associated with her were among the most impressive in late modern history.".<ref>Robinson, James Divine Healing: The Years of Expansion, 1906–1930: Theological Variation in the Transatlantic World. (Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2014), p. 204.</ref> |

|||

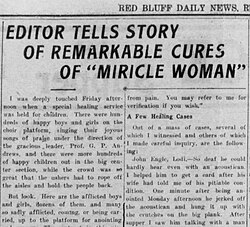

[[File:ASM MiracleWomanHeadline.jpg|250px|thumb|left|alt=Aimee Semple McPherson's apparently successful faith healings attracted large crowds and journalists to her revivals.| Aimee Semple McPherson's apparently successful faith healings attracted large crowds and journalists to her revivals.<ref>Epstein, Daniel Mark, Sister Aimee: The Life of Aimee Semple McPherson (Orlando: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1993), pp. 166, 178, 182</ref>]] |

|||

McPherson's [[faith healing]] demonstrations were extensively written about in the news media and were a large part of her early career legacy.<ref>Epstein, p. 57</ref> No one has ever been credited by secular witnesses with anywhere near the numbers of faith healings attributed to McPherson, especially during the years 1919 to 1922.<ref>Epstein, p. 185</ref> Over time though, she almost withdrew from the faith healing aspect of her services, since it was overwhelming<ref>Epstein, p. 111</ref> other areas of her ministry and McPherson wanted to appeal to a more mainstream audience. Scheduled healing sessions nevertheless remained highly popular with the public until her death in 1944. |

|||

In April 1920, a ''Washington Times'' reporter conveyed that for McPherson's work to be a hoax on such a grand scale was inconceivable, communicating that the healings were occurring more rapidly than he could record them. To help verify the testimonies, as per his editor, the reporter took names and addresses of those he saw and with whom he spoke. Documentation, including news articles, letters, and testimonials indicated sick people came to her by the tens of thousands. According to these sources, some healings were only temporary, while others lasted throughout people's lives.<ref>{{cite news |title=Unforgettable: When Sister Aimee Came to Town |work=San Diego Reader |url=http://www.sandiegoreader.com/news/2009/sep/09/when-sister-aimee-came-town---part-1/?page=2}}</ref><ref name="Edith Waldvogel Blumhofer 1993 pp.160- 161" /><ref>{{cite book |last=Epstein |first=Daniel Mark |title=Sister Aimee: The Life of Aimee Semple McPherson |date=1993 |publisher=Harcourt Brace & Company |location=Orlando |pages=111, 166, 178, 182, 448}}</ref> |

|||