St. Louis: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

Magnolia677 (talk | contribs) Undid revision 1264021066 by Rustydogz (talk) Removing unsourced content |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{About|the city in Missouri, United States}} |

|||

{{otheruses4|the independent city|the surrounding counties|St. Louis Metropolitan Statistical Area}} |

|||

{{Pp-move}} |

|||

{{Infobox City |official_name = St. Louis, Missouri |

|||

{{Pp-semi-indef}} |

|||

|nickname = Gateway City", "Gateway to the West", or "Mound City |

|||

{{More citations needed|date=July 2024}} |

|||

|website = http://stlouis.missouri.org/ |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=November 2023}} |

|||

|image_flag = Saint Louis, Missouri flag.svg |

|||

{{Use American English|date=November 2023}} |

|||

|image_seal = Stl cityseal.jpg |

|||

{{Infobox settlement |

|||

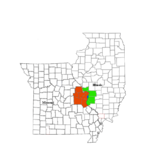

|image_map = MOMap-doton-Saint Louis.png |

|||

| name = St. Louis |

|||

|map_caption = Location in the state of [[Missouri]] |

|||

| settlement_type = [[Independent city (United States)|Independent city]] |

|||

|subdivision_type = [[Countries of the world|Country]]<br> [[Political divisions of the United States|State]]<br> [[List of counties in Missouri|County]] |

|||

| image_skyline = {{multiple image |

|||

|subdivision_name = [[United States]]<br>[[Missouri]]<br>[[Independent City]] |

|||

| total_width = 300 |

|||

|leader_title = [[Mayor]] |

|||

| border = infobox |

|||

|leader_name = [[Francis G. Slay]] ([[Democratic Party (United States)|D]]) |

|||

| perrow = 1,2,2,1 |

|||

|area_magnitude = 1 E8 |

|||

| caption_align = center |

|||

|area_total = 66.2 mi² - 171.3 |

|||

| image1 = Runner Fountain and Old Courthouse and Arch (5618845531).jpg |

|||

|area_land = 61.9 mi² - 160.4 |

|||

| caption1 = The [[Old Courthouse (St. Louis)|Old Courthouse]] and [[Gateway Arch]] in [[Downtown St. Louis]] |

|||

|area_water = 4.2 mi² - 11.0 |

|||

| image2 = St. Louis Art Museum.JPG |

|||

|population_as_of = 2005 |

|||

| caption2 = [[Saint Louis Art Museum]] |

|||

|population_total = 352,572 |

|||

| image3 = Busch Pano 2022.jpg |

|||

|population_metro = 2,764,054 |

|||

| caption3 = [[Busch Stadium]] |

|||

|population_density = 5,695.8/mi² - 2,224.9 |

|||

| image4 = Climatron - panoramio.jpg |

|||

|timezone = [[Central Standard Time Zone|CST]] |

|||

| caption4 = [[Missouri Botanical Garden]] |

|||

|utc_offset = -6 |

|||

| image5 = St. Louis Union Station (17577826564).jpg |

|||

|timezone_DST = [[Central Daylight Time|CDT]] |

|||

| caption5 = [[St. Louis Union Station|Union Station]] |

|||

|utc_offset_DST = -5 |

|||

}} |

|||

|latd = 38 |

|||

| image_flag = Flag of St. Louis, Missouri.svg |

|||

|latm = 38 |

|||

| image_seal = Seal of St. Louis, Missouri.svg |

|||

|lats = 53 |

|||

| image_blank_emblem = Logo of St. Louis, Missouri.svg |

|||

|latNS = N |

|||

| blank_emblem_type = Logo |

|||

|longd = 90 |

|||

| nickname = "Gateway to the West",<ref name="Globosapiens.net">{{cite web|url=http://www.globosapiens.net/travel-information/St.+Louis-698.html|title=St. Louis United States – Visiting the Gateway to the West|publisher=Globosapiens.net|access-date=March 14, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110515090544/http://www.globosapiens.net/travel-information/St.+Louis-698.html |archive-date=May 15, 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref> The Gateway City,<ref name="Globosapiens.net"/> Mound City,<ref>[http://www.slpl.org/slpl/interests/article240099632.asp St. Louis Public Library on "Mound City"] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081001231020/http://www.slpl.org/slpl/interests/article240099632.asp|date=October 1, 2008}}.</ref> The Lou,<ref> |

|||

|longm = 12 |

|||

[https://archive.today/20080522094145/http://www.stltoday.com/blogzone/the-editors-desk/the-editors-desk/2008/05/offended-by-the-lou/ STLtoday.com on "The Lou"].</ref> Rome of the West,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.romeofthewest.com/ |title=Rome of the West |publisher=Stltoday.com |access-date=August 10, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170810033358/http://www.romeofthewest.com/|archive-date=August 10, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> River City, The STL, St. Lou |

|||

|longs = 44 |

|||

| image_map = {{maplink |

|||

|longEW = W |

|||

| frame = yes |

|||

|elevation = 141.7 |

|||

| plain = yes |

|||

|footnotes = |

|||

| frame-align = center |

|||

| frame-width = 290 |

|||

| frame-height = 290 |

|||

| frame-coord = {{coord|38.6386|-90.2463}} |

|||

| zoom = 10 |

|||

| type = shape |

|||

| marker = city |

|||

| stroke-width = 2 |

|||

| stroke-color = #0096FF |

|||

| fill = #0096FF |

|||

| id2 = Q38022 |

|||

| type2 = shape-inverse |

|||

| stroke-width2 = 2 |

|||

| stroke-color2 = #5F5F5F |

|||

| stroke-opacity2 = 0 |

|||

| fill2 = #000000 |

|||

| fill-opacity2 = 0 |

|||

}} |

|||

| map_caption = Interactive map of St. Louis |

|||

| pushpin_map = Missouri#USA |

|||

| pushpin_relief = yes |

|||

| coordinates = {{coord|38|37|38|N|90|11|52|W|region:US-MO_type:city(302,000)|display=inline,title}} |

|||

| subdivision_type = [[List of sovereign states|Country]] |

|||

| subdivision_name = United States |

|||

| subdivision_type1 = [[U.S. state|State]] |

|||

| subdivision_name1 = [[Missouri]] |

|||

| subdivision_type2 = [[Combined statistical area|CSA]] |

|||

| subdivision_name2 = [[Greater St. Louis|St. Louis–St. Charles–Farmington, MO–IL]] |

|||

| subdivision_type3 = [[Metropolitan statistical area|Metro]] |

|||

| subdivision_name3 = [[St. Louis, MO-IL MSA|St. Louis, MO-IL]] |

|||

| established_title = Founded |

|||

| established_date = February 14, 1764 |

|||

| established_title2 = [[Municipal corporation|Incorporated]] |

|||

| established_date2 = 1822 |

|||

| named_for = [[Louis IX of France]] |

|||

| government_type = [[Mayor–council government|Mayor–council]] |

|||

| governing_body = [[St. Louis Board of Aldermen|Board of Aldermen]] |

|||

| leader_title = [[Mayor of St. Louis|Mayor]] |

|||

| leader_name = [[Tishaura Jones]] ([[Democratic Party (United States)|D]]) |

|||

| leader_title1 = [[St. Louis Board of Aldermen|President, Board of Aldermen]] |

|||

| leader_name1 = [[Megan Green]] ([[Democratic Party (United States)|D]]) |

|||

| leader_title2 = [[Treasurer]] |

|||

| leader_name2 = Adam Layne |

|||

| leader_title3 = [[Comptroller]] |

|||

| leader_name3 = Darlene Green ([[Democratic Party (United States)|D]]) |

|||

| leader_title4 = [[United States House of Representatives|Congressional representative]] |

|||

| leader_name4 = [[Cori Bush]] ([[Democratic Party (United States)|D]]) |

|||

| unit_pref = Imperial |

|||

| area_total_km2 = 171.39 |

|||

| area_total_sq_mi = 66.17 |

|||

| area_land_km2 = 159.85 |

|||

| area_land_sq_mi = 61.72 |

|||

| area_water_km2 = 11.53 |

|||

| area_water_sq_mi = 4.45 |

|||

| area_urban_sq_mi = 910.4 |

|||

| area_urban_km2 = 2,357.8 |

|||

| area_metro_sq_mi = 8,458 |

|||

| area_footnotes = <ref name="TigerWebMapServer">{{cite web|title=ArcGIS REST Services Directory|url=https://tigerweb.geo.census.gov/arcgis/rest/services/TIGERweb/Places_CouSub_ConCity_SubMCD/MapServer|publisher=United States Census Bureau|accessdate=August 28, 2022|archive-date=January 19, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220119173812/https://tigerweb.geo.census.gov/arcgis/rest/services/TIGERweb/Places_CouSub_ConCity_SubMCD/MapServer|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| elevation_footnotes = <ref name="St. Louis Elevation">{{cite web|title=St. Louis City, Missouri – Population Finder – American FactFinder|publisher=[[United States Geological Survey]]|url=http://geonames.usgs.gov/pls/gnispublic/f?p=106:3:3712217792123411::NO::P3_FID:765765|date=October 24, 1980|access-date=December 23, 2008|archive-date=January 22, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200122161856/https://geonames.usgs.gov/login/index.php|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| elevation_ft = 466 |

|||

| elevation_max_footnotes = <ref name="St. Louis elevation 2">{{cite web|title=Elevations and Distances in the United States|url=http://egsc.usgs.gov/isb//pubs/booklets/elvadist/elvadist.html|website=U.S. Geological Survey|publisher=U.S. Department of the Interior — U.S. Geological Survey|access-date=October 17, 2016|date=April 29, 2005|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131109183109/http://egsc.usgs.gov/isb//pubs/booklets/elvadist/elvadist.html|archive-date=November 9, 2013|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| population_total = 301578 |

|||

| population_as_of = [[2020 United States census|2020]] |

|||

| population_est = 293310 |

|||

| pop_est_as_of = 2021 |

|||

| pop_est_footnotes = <ref name="USCensusEst2021"/> |

|||

| population_footnotes = <ref name="2020 Census (City)"/> |

|||

| population_density_sq_mi = 4886.23 |

|||

| population_density_km2 = 1886.59 |

|||

| population_urban = 2156323 (US: [[List of United States urban areas|22nd]]) |

|||

| population_density_urban_km2 = 914.5 |

|||

| population_density_urban_sq_mi = 2,368.6 |

|||

| population_metro = 2809299 (US: [[Metropolitan statistical area|21st]]) |

|||

| population_rank = US: [[List of United States cities by population|76th]]<br>Midwest: 13th<br>Missouri: 2nd |

|||

| population_blank2_title = [[Combined Statistical Area|CSA]] |

|||

| population_blank2 = 2914230 (US: [[Combined statistical area|20th]]) |

|||

| population_demonym = St. Louisan; Saint Louisan |

|||

| demographics_type2 = GDP |

|||

| demographics2_footnotes = <ref>{{Cite web |title= Total Gross Domestic Product for St. Louis, MO-IL (MSA) |url= https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/NGMP41180 |website= fred.stlouisfed.org |access-date= December 7, 2023 |archive-date= October 9, 2023 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20231009234549/https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/NGMP41180 |url-status= live }}</ref> |

|||

| demographics2_title1 = Greater St. Louis |

|||

| demographics2_info1 = $209.9 billion (2022) |

|||

| postal_code_type = [[ZIP Code]]s |

|||

| postal_code = {{collapsible list |

|||

| title = List |

|||

| frame_style = border:none; padding: 0; |

|||

| list_style = display:none |

|||

|63101–63141<br />63143–63147<br />63150–63151<br />63155–63158<br />63160<br />63163–63164<br />63166–63167<br />63169<br />63171<br />63177–63180<br />63182<br />63188<br />63190<br />63195<br />63197–63199}} |

|||

| area_code = [[Area code 314|314/557]] |

|||

| area_code_type = [[North American Numbering Plan|Area code]] |

|||

| timezone = [[Central Time Zone|CST]] |

|||

| utc_offset = −6 |

|||

| timezone_DST = [[Central Time Zone|CDT]] |

|||

| utc_offset_DST = −5 |

|||

| elevation_max_ft = 614 |

|||

| blank_name = [[Federal Information Processing Standards|FIPS code]] |

|||

| blank_info = 29-65000 |

|||

| website = {{URL|https://stlouis-mo.gov}} |

|||

| footnotes = |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''St. Louis''' ({{IPAc-en|s|eɪ|n|t|_|ˈ|l|uː|ᵻ|s|,_|s|ən|t|-}} {{respell|saynt|_|LOO|iss|,_|sənt|-}})<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/saint%20louis|title=Dictionary and Thesaurus - Merriam-Webster|access-date=July 23, 2020|archive-date=October 22, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201022075756/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/saint%20louis|url-status=live}}</ref> is an [[Independent city (United States)|independent city]] in the [[U.S. state]] of [[Missouri]]. It is located near the [[confluence]] of the [[Mississippi River|Mississippi]] and the [[Missouri River|Missouri]] rivers. In 2020, the [[city proper]] had a population of 301,578,<ref name="2020 Census (City)">{{cite web |title=Explore Census Data |url=https://data.census.gov/cedsci/profile/St._Louis_city,_Missouri?g=1600000US2965000 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230602183509/https://data.census.gov/cedsci/profile/St._Louis_city,_Missouri?g=1600000US2965000 |url-status=dead |archive-date=June 2, 2023 |publisher=[[United States Census Bureau]] |access-date=October 7, 2022 }}</ref> while [[Greater St. Louis|its metropolitan area]], which extends into [[Illinois]], had an estimated population of over 2.8 million. It is the [[List of metropolitan areas of Missouri|largest metropolitan area in Missouri]] and the second-largest in Illinois. The city's [[combined statistical area]] is the 20th-largest in the United States.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals: 2020-2022 |url=https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-total-metro-and-micro-statistical-areas.html |access-date=2023-10-27 |website=Census.gov |archive-date=June 29, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220629175327/https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-total-metro-and-micro-statistical-areas.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

'''St. Louis''' (pronounced {{IPA|/seɪntˈluːɪs/}} in [[English language|English]], [[Image:ltspkr.png]][[Media:Saint-Louis.ogg|{{IPA|/sɛ̃ lwi/}}]] in [[French language|French]]), sometimes written '''Saint Louis''', encompasses an [[independent city]] in the [[U.S. state]] of [[Missouri]] (the "City of St. Louis") and its [[metropolitan area]] ([[St. Louis Metropolitan Statistical Area|Greater St. Louis]]). This area includes counties in the states of [[Missouri]] and [[Illinois]]; it is the 18th largest in the [[United States]] with a population of 2,698,672 as of the [[United States 2000 census|2000 census]]. According to the St. Louis Regional Chamber and Growth Association (RCGA), the 2004 population is approximately 2,764,054. |

|||

The land that became St. Louis had been occupied by [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]] cultures for thousands of years before [[European colonization of the Americas|European settlement]]. The city was founded on February 14, 1764, by French fur traders [[Gilbert Antoine de St. Maxent]], [[Pierre Laclède]], and [[Auguste Chouteau]].<ref name="Cazorla et al">Cazorla, Frank; Baena, Rose; Polo, David; and Reder Gadow, Marion. (2019) ''The governor Louis de Unzaga (1717–1793) Pioneer in the Birth of the United States of America''. Foundation, Malaga, pages 49, 57–65, 70–75, 150, 207</ref> They named it for King [[Louis IX of France]], and it quickly became the regional center of the French [[Illinois Country]]. In 1804, the United States acquired St. Louis as part of the [[Louisiana Purchase]]. In the 19th century, St. Louis developed as a major port on the Mississippi River; from 1870 until the 1920 census, it was the fourth-largest city in the country. It separated from [[St. Louis County, Missouri|St. Louis County]] in 1877, becoming an [[independent city]] and limiting its political boundaries. In 1904, it hosted the [[Louisiana Purchase Exposition]], also known as the St. Louis World's Fair, and the [[1904 Summer Olympics|Summer Olympics]].<ref>{{Cite book |title=History: Physical Growth of the City of St. Louis |publisher=St. Louis City Planning Commission |year=1969}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=A Brief History of St. Louis |url=https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/visit-play/stlouis-history.cfm |access-date=2023-12-10 |website=stlouis-mo.gov |language=en |archive-date=July 26, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230726081313/https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/visit-play/stlouis-history.cfm |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

The city, which is named after [[Louis IX of France|Louis IX]] of [[France]], is adjacent to, but not part of, [[St. Louis County, Missouri]] and has a population of 352,572. St. Louis has the state's largest metropolitan area population. In relation to the [[Midwestern United States|Midwest]] region, the City of St. Louis is the 10th largest city in population (between Minneapolis, Minnesota and Wichita, Kansas). |

|||

St. Louis is designated as one of 173 [[global city|global cities]] by the [[Globalization and World Cities Research Network]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=GaWC - The World According to GaWC 2020 |url=https://www.lboro.ac.uk/microsites/geography/gawc/world2020t.html |access-date=2023-12-07 |website=www.lboro.ac.uk |archive-date=March 16, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230316190541/https://www.lboro.ac.uk/microsites/geography/gawc/world2020t.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The GDP of Greater St. Louis was $209.9 billion in 2022.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web |last=U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis |date=2001-01-01 |title=Total Gross Domestic Product for St. Louis, MO-IL (MSA) |url=https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/NGMP41180 |access-date=2023-12-07 |website=FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis |archive-date=October 9, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231009234549/https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/NGMP41180 |url-status=live }}</ref> St. Louis has a diverse economy with strengths in the service, manufacturing, trade, transportation, and aviation industries.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Commerce and Industry {{!}} UMSL |url=https://www.umsl.edu/searches/stl/commerce.html |access-date=2023-12-08 |website=www.umsl.edu |archive-date=December 8, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231208035741/https://www.umsl.edu/searches/stl/commerce.html |url-status=live }}</ref> It is home to sixteen [[Fortune 1000|''Fortune'' 1000]] companies, six of which are also [[Fortune 500|''Fortune'' 500]] companies.<ref name=":2">{{Cite web |title=6 St. Louis-area companies make Fortune 500 ranking, down from 7 |url=https://www.bizjournals.com/stlouis/news/2024/06/05/6-st-louis-area-companies-make-2024-fortune-500.html |access-date=2024-11-28 |website=www.bizjournals.com}}</ref> Federal agencies headquartered in the city or with significant operations there include the [[Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis]], the [[United States Department of Agriculture|U.S. Department of Agriculture]], and the [[National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency]]. |

|||

The city has several common [[nickname]]s, including the "Gateway City", "Gateway to the West", "Baseball City USA", and "Mound City". St. Louis is also sometimes called "St. Louie", "River City" or "Baseball Heaven". Alternatively, many young people who live in St. Louis have begun to call it "The 'Lou". Another popular synonym for St. Louis is "The STL" in reference to the airport code for the city (STL) and a long-standing use of an interlocked S, T and L by the [[St. Louis Cardinals]] baseball team. |

|||

Major [[Research university|research universities]] in Greater St. Louis include [[Washington University in St. Louis]], [[Saint Louis University]],<!-- "Saint Louis University" is never abbreviated. --> and the [[University of Missouri–St. Louis]]. The [[Washington University Medical Center]] in the [[Central West End, St. Louis|Central West End]] neighborhood hosts an agglomeration of [[List of hospitals in St. Louis|medical and pharmaceutical institutions]], including [[Barnes-Jewish Hospital]]. |

|||

St. Louis has [[Sports in St. Louis|four professional sports teams]]: the [[St. Louis Cardinals]] of [[Major League Baseball]], the [[St. Louis Blues]] of the [[National Hockey League]], [[St. Louis City SC]] of [[Major League Soccer]], and the [[St. Louis BattleHawks]] of the [[United Football League (2024)|United Football League]]. The city's attractions include the {{convert|630|ft|m|adj=mid|0}} [[Gateway Arch]] in [[Downtown St. Louis]], the [[St. Louis Zoo]], the [[Missouri Botanical Garden]], the [[St. Louis Art Museum]], and [[Bellefontaine Cemetery]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://fox2now.com/2018/05/04/st-louis-zoo-named-best-zoo-and-wins-best-zoo-exhibit-in-readers-choice-awards/|title=St. Louis Zoo named 'Best Zoo' and wins 'Best Zoo Exhibit' in Readers' Choice Awards|date=May 4, 2018|website=FOX2now.com|language=en|access-date=August 2, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190802221146/https://fox2now.com/2018/05/04/st-louis-zoo-named-best-zoo-and-wins-best-zoo-exhibit-in-readers-choice-awards/|archive-date=August 2, 2019|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://arbnet.org/morton-register/bellefontaine-cemetery-and-arboretum|title=Bellefontaine Cemetery and Arboretum Level II Accreditation Listing|website=arbnet.org/morton-register/bellefontaine-cemetery-and-arboretum|access-date=December 8, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201125022302/http://www.arbnet.org/morton-register/bellefontaine-cemetery-and-arboretum|archive-date=November 25, 2020|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

{{ |

{{Main|History of St. Louis}} |

||

{{For timeline}} |

|||

===Mississippian culture and European exploration=== |

|||

{{Quote box |width=20em |align=right|bgcolor=#B0C4DE |

|||

|title=Historical affiliations |

|||

|fontsize=90% |quote={{flag|Kingdom of France}} 1690s–1763<br />{{flag|Kingdom of Spain|1785}} 1763–1800<br />{{flag|French First Republic}} 1800–1803<br />{{flag|United States|1804}} 1803–present |

|||

}} |

|||

[[File:Old_Chouteau_Mansion,_St._Louis._Mo_(cropped).jpg|thumb|The home of [[Auguste Chouteau]] is in St. Louis. [[Gilbert Antoine de St. Maxent]],<ref name="Cazorla et al"/> Chouteau, and [[Pierre Laclède]] founded St. Louis in 1764.]] |

|||

{{Main|History of St. Louis before 1762}} |

|||

The area that became St. Louis was a center of the [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]] [[Mississippian culture]], which built numerous temple and residential [[Earthwork (archaeology)|earthwork]] [[Mound builder (people)|mounds]] on both sides of the Mississippi River. Their major regional center was at [[Cahokia Mounds]], active from 900 to 1500. Due to numerous major [[earthworks (engineering)|earthworks]] within St. Louis boundaries, the city was nicknamed as the "Mound City". These mounds were mostly demolished during the city's development. Historic Native American tribes in the area encountered by early Europeans included the [[Siouan]]-speaking [[Osage people]], whose territory extended west, and the [[Illiniwek]].{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

|||

European exploration of the area was first recorded in 1673, when French explorers [[Louis Jolliet]] and [[Jacques Marquette]] traveled through the Mississippi River valley. Five years later, [[René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle|La Salle]] claimed the region for France as part of [[Louisiana (New France)|La Louisiane]], also known as [[Louisiana]]. The earliest European settlements in the [[Illinois Country]] (also known as Upper Louisiana) were built by the French during the 1690s and early 1700s at [[Cahokia, Illinois|Cahokia]], [[Kaskaskia, Illinois|Kaskaskia]], and [[Fort de Chartres]]. Migrants from the French villages on the east side of the [[Mississippi River]], such as Kaskaskia, also founded [[Ste. Genevieve, Missouri|Ste. Genevieve]] in the 1730s.{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

|||

Prior to the arrival of [[France|French]] explorers in [[1673]] the area that would become St. Louis was a major center of the [[Mississippian culture|Mississippian]] [[Mound Builders|mound builders]]. The presence of numerous mounds, now almost all destroyed, earned the later city the nickname of "Mound City." |

|||

In 1764, after France lost the [[Seven Years' War]], [[Pierre Laclède]] and his stepson [[Auguste Chouteau]] founded what was to become the city of St. Louis.<ref>Hoffhaus. (1984). ''Chez Les Canses: Three Centuries at Kawsmouth'', Kansas City: Lowell Press. {{ISBN|0-913504-91-2}}.</ref> (French lands east of the Mississippi had been ceded to [[Kingdom of Great Britain|Great Britain]] and the lands west of the Mississippi to Spain; Catholic France and Spain were 18th-century allies. [[Louis XV of France]] and [[Charles III of Spain]] were cousins, both from the House of Bourbon.<ref>[[Pacte de Famille#The third Pacte de Famille]]</ref>{{Circular reference|date=August 2019}}) The French families built the city's economy on the [[fur trade]] with the Osage, and with more distant tribes along the [[Missouri River]]. The Chouteau brothers gained a monopoly from Spain on the fur trade with [[Santa Fe, New Mexico|Santa Fe]]. French colonists used [[History of slavery in Missouri|African slaves]] as domestic servants and workers in the city.{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

|||

===City founding and early history=== |

|||

European exploration of the area had begun nearly a century before the city was founded. [[Louis Joliet]] and [[Jacques Marquette]], both French, traveled through the [[Mississippi River]] valley in [[1673]], and five years later, [[René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle|La Salle]] claimed the entire valley for [[France]]. He called it "Louisiana" after King [[Louis XIV of France|Louis XIV]]; the French also called their region "[[Illinois Country]]." In 1699, a settlement was established across the river from what is now St. Louis, at [[Cahokia, Illinois|Cahokia]]. Other early settlements were downriver at [[Kaskaskia, Illinois|Kaskaskia]], Prairie du Pont, [[Fort de Chartres]], and [[Sainte Genevieve, Missouri|Sainte Genevieve]]. In 1703, Catholic priests established a small mission at what is now St. Louis. The mission was later moved across the Mississippi, but the small river at the site (now a drainage channel near the southern boundary of the City of St. Louis) still bears the name "River Des Peres" (River of the Fathers). |

|||

During the negotiations for the 1763 [[Treaty of Paris (1763)|Treaty of Paris]], French negotiators agreed to transfer France's colonial territories west of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers to [[New Spain]] to compensate for Spanish territorial losses during the war. These areas remained under Spanish control until 1803, when they were transferred to the [[French First Republic]]. During the [[American Revolutionary War]], St. Louis was unsuccessfully attacked by British-allied Native Americans in the 1780 [[Battle of St. Louis]].<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20010223093542/http://www.usgennet.org/usa/mo/county/stlouis/attack.htm ''www.usgennet.org''.] Attack On St. Louis: May 26, 1780.</ref> |

|||

In 1763, [[Pierre Laclède]], his 13-year-old "stepson" [[René Auguste Chouteau|Auguste Chouteau]], and a small band of men traveled up the Mississippi from [[New Orleans]]. In November, they landed a few miles downstream of the river's confluence with the [[Missouri River]] at a site where wooded limestone bluffs rose 40 feet above the river. The men returned to Fort de Chartres for the winter, but in February, Laclede sent Chouteau and 30 men to begin construction. The settlement was established on [[February 15]], 1764. |

|||

===Founding=== |

|||

The settlement began to grow quickly after word arrived that the 1763 [[Treaty of Paris (1763)|Treaty of Paris]] had given England all the land east of the Mississippi. Frenchmen who had settled to the river's east moved across the water to "Laclede's Village." Other early settlements were established nearby at [[Saint Charles, Missouri|Saint Charles]], Carondelet (now a part of the city of St. Louis), Fleurissant (renamed Saint Ferdinand under the Spaniards and now [[Florissant]]), and [[Portage Des Sioux, Missouri|Portage des Sioux]]. In 1765, St. Louis was made the capital of Upper Louisiana. |

|||

{{Main|History of St. Louis (1763–1803)}} |

|||

The founding of St. Louis was preceded by a trading business between [[Gilbert Antoine de St. Maxent]] and [[Pierre Laclède|Pierre Laclède (Liguest)]] in late 1763. St. Maxent invested in a Mississippi River expedition led by Laclède, who searched for a location to base the company's fur trading operations. Though [[Ste. Genevieve, Missouri|Ste. Genevieve]] was already established as a trading center, he sought a place less prone to flooding. He found an elevated area overlooking the flood plain of the Mississippi River, not far south from its confluence with the Missouri and Illinois rivers. In addition to having an advantageous natural drainage system, there were nearby forested areas to supply timber and grasslands which could easily be converted for agricultural purposes. Laclède declared that this place "might become, hereafter, one of the finest cities in America". He dispatched his 14-year-old stepson, [[Auguste Chouteau]], to the site, with the support of 30 settlers in February 1764.<ref name="wade3">{{cite book |last1=Wade |first1=Richard C.|title=The Urban Frontier: The Rise of Western Cities, 1790–1830 |date=1959 |location=Cambridge |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=0-252-06422-4 |pages=3–4|edition=1996 Illini Books}}</ref> |

|||

Laclède arrived at the future town site two months later and produced a plan for St. Louis based on the New Orleans street plan. The default block size was 240 by 300 feet, with just three long avenues running parallel to the west bank of the Mississippi. He established a public corridor of 300 feet fronting the river, but later this area was released for private development.<ref name=wade3/> |

|||

[[Image:Apotheosis-of-saint-louis.jpg|thumb|right|margin:0 0 1em 1em|228px|''[[Apotheosis]] of Saint Louis'', a [[bronze]] statue of the city's namesake on horseback, was widely used as a symbol of the city before construction of the Arch.]] |

|||

[[Image:stl15.jpg|thumb|right|margin:0 0 1em 1em|228px|An aerial view of downtown looking south.]] |

|||

From 1766 to 1768, St. Louis was governed by the French lieutenant governor, Louis Saint Ange de Bellerive. After 1768, St. Louis was governed by a [[List of commandants of the Illinois Country|series of Spanish governors]], whose administration continued even after Louisiana was secretly returned to France in 1800 by the [[Third Treaty of San Ildefonso|Treaty of San Ildefonso]]. The town's population was then about a thousand. |

|||

[[File:St-louis-attack.jpg|thumb|alt=This photograph of a mural titled ''Indian Attack on the Village of St. Louis'', 1780, depicts the Battle of St. Louis.|The mural ''Indian Attack on the Village of St. Louis'', 1780, depicts that during the American Revolutionary War, St. Louis was unsuccessfully attacked by British-allied Native Americans in the [[Battle of St. Louis]] in 1780.]] |

|||

St. Louis was acquired from France by the [[United States]] under [[President of the United States|President]] [[Thomas Jefferson]] in [[1803]], as part of the [[Louisiana Purchase]]. The transfer of power from Spain was made official in a ceremony called "Three Flags Day." On [[March 8]] [[1804]], the Spanish flag was lowered and the French one raised. On [[March 10]], the French flag was replaced by the United States flag. |

|||

For the city's first few years, it was not recognized by any governments. Although the settlement was thought to be under the control of the Spanish government, no one asserted any authority over it, and thus St. Louis had no local government. This vacuum led Laclède to assume civil control, and all problems were disposed in public settings, such as communal meetings. In addition, Laclède granted new settlers lots in town and the surrounding countryside. In hindsight, many of these original settlers thought of these first few years as "the golden age of St. Louis".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Van Ravenswaay |first1=Charles |title=St. Louis: An Informal History of the City and Its People, 1764-1865 |date=1991 |publisher=Missouri History Museum |isbn=9780252019159 |pages=26}}</ref> In 1763, the Native Americans in the region around St. Louis began expressing dissatisfaction with the victorious British, objecting to their refusal to continue to the French tradition of supplying gifts to Natives. Odawa chieftain [[Pontiac (Odawa leader)|Pontiac]] began forming a pan-tribal alliance to counter British control over the region but received little support from the indigenous residents of St. Louis. By 1765, the city began receiving visits from representatives of the British, French, and Spanish governments.{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

|||

St. Louis was transferred to the [[French First Republic]] in 1800 (although all of the colonial lands continued to be administered by Spanish officials), then sold by the French to the U.S. in 1803 as part of the [[Louisiana Purchase]]. St. Louis became the capital of, and gateway to, the new territory. Shortly after [[Three Flags Day|the official transfer of authority]] was made, the [[Lewis and Clark Expedition]] was commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson. The expedition departed from St. Louis in May 1804 along the Missouri River to explore the vast territory. There were hopes of finding a water route to the Pacific Ocean, but the party had to go overland in the Upper West. They reached the Pacific Ocean via the Columbia River in summer 1805. They returned, reaching St. Louis on September 23, 1806. Both Lewis and Clark lived in St. Louis after the expedition. Many other explorers, settlers, and trappers (such as [[Ashley's Hundred]]) would later take a similar route to the West.{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

|||

===19th Century expansion and growth=== |

|||

The [[Lewis and Clark Expedition]] left the St. Louis area in May 1804, reached the [[Pacific Ocean]] in the summer of 1805, and returned on [[23 September]] [[1806]]. Many other explorers, settlers, and trappers (such as [[Ashley's Hundred]]) would later take a similar route to the West. Missouri became a state in 1820. St. Louis was incorporated as a city on [[December 9]] [[1822]]. A U.S. arsenal was constructed at St. Louis in 1827. |

|||

===19th century=== |

|||

The steamboat era began in St. Louis on [[July 27]] [[1817]], with the arrival of the "[[Zebulon M. Pike]]." Rapids north of the city made St. Louis the northernmost navigable port for many large boats, and "Pike" and her sisters soon transformed St. Louis into a bustling boomtown, commercial center, and inland port. By the 1850s, St. Louis had become the largest U.S. city west of Pittsburgh, and the second-largest port in the country, with a commercial tonnage exceeded only by New York. |

|||

{{Main|History of St. Louis (1804–1865)|History of St. Louis (1866–1904)}} |

|||

{{see also|St. Louis in the American Civil War}} |

|||

[[File:White men pose, 104 Locust Street, St. Louis, Missouri in 1852 at Lynch's Slave Market - (cropped).jpg|thumb|White men pose in 1852 at Lynch's [[slave market]] at 104 Locust Street.]] |

|||

The city elected its first municipal legislators (called trustees) in 1808. [[Steamboat]]s first arrived in St. Louis in 1817, improving connections with [[New Orleans]] and eastern markets. Missouri was admitted as a state in 1821. St. Louis was incorporated as a city in 1822, and continued to develop largely due to its busy [[port]] and trade connections.{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

|||

[[File:City of Saint Louis and Riverfront, 1874.jpg|thumb|City of St. Louis and Riverfront, 1874]] |

|||

Immigrants flooded into St. Louis after 1840, particularly from [[Germany]], [[Bohemia]], [[Italy]] and [[Ireland]], the latter driven by an Old World [[Irish Potato Famine (1845-1849)|potato famine]]. The population of St. Louis grew from fewer than 20,000 in 1840, to 77,860 in 1850, to just over 160,000 by 1860. |

|||

[[File:St. Louis, Mo. tornado May 27, 1896 south broadway.JPG|thumb|South Broadway had a tornado on May 27, 1896.]] |

|||

Immigrants from Ireland and Germany arrived in St. Louis in significant numbers starting in the 1840s, and the population of St. Louis grew from less than 20,000 inhabitants in 1840, to 77,860 in 1850, to more than 160,000 by 1860. By the mid-1800s, St. Louis had a greater population than New Orleans.{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

|||

Settled by many Southerners in a [[Free and slave states|slave state]], the city was split in political sympathies and became polarized during the [[American Civil War]]. In 1861, 28 civilians were killed in a [[Camp Jackson Affair|clash with Union troops]]. The war hurt St. Louis economically, due to the [[Union blockade]] of river traffic to the south on the Mississippi River. The [[St. Louis Arsenal]] constructed [[ironclad]]s for the [[Union Navy]].{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

|||

Two disasters occurred in 1849: a cholera epidemic killed nearly one-tenth of the population, and a [[St. Louis Fire (1849)|fire]] destroyed numerous steamboats and a large portion of the city. These disasters led to political action: old cemeteries were removed to the outskirts of the town; sinkholes were filled and swamps drained; water and sewer public utilities started; and a new building code required structures to be built of stone or brick. |

|||

[[History of slavery in Missouri|Slaves]] worked in many jobs on the waterfront and on the riverboats. Given the city's location close to the [[Free and slave states|free state]] of Illinois and others, some slaves escaped to freedom. Others, especially women with children, sued in court in [[freedom suits]], and several prominent local attorneys aided slaves in these suits. About half the slaves achieved freedom in hundreds of suits before the American Civil War. |

|||

In the first half of the 19th century, a second channel developed in the Mississippi River at St. Louis. An island ("Bloody Island") formed between the two channels, and a smaller island ("Duncan's Island") developed below St. Louis. It was feared that the levee at St. Louis might be left high and dry, and federal assistance was sought and obtained. Under the supervision of [[Robert E. Lee]], levees were constructed on the Illinois side to direct water toward the Missouri side and eliminate the second channel. Bloody Island was joined to the land on the Illinois side, and Duncan's Island was washed away. |

|||

The printing press of abolitionist [[Elijah Parish Lovejoy]] was destroyed for the third time by townsfolk. He was murdered the next year in nearby [[Alton, Illinois]].{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

|||

After the war, St. Louis profited via trade with the West, aided by the 1874 completion of the [[Eads Bridge]], named for its design engineer. Industrial developments on both banks of the river were linked by the bridge, the second in the Midwest over the Mississippi River after the Hennepin Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis. The bridge connects St. Louis, Missouri to [[East St. Louis, Illinois]]. The Eads Bridge became a symbolic image of the city of St. Louis, from the time of its erection until 1965 when the [[Gateway Arch]] Bridge was constructed. The bridge crosses the St. Louis riverfront between Laclede's Landing, to the north, and the grounds of the Gateway Arch, to the south. Today the road deck has been restored, allowing vehicular and pedestrian traffic to cross the river. The St. Louis MetroLink light rail system has used the rail deck since 1993. An estimated 8,500 vehicles pass through it daily.{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

|||

Militarily, the [[American Civil War|Civil War]] (1861-1865) barely touched St. Louis; the area saw only a few skirmishes in which [[Union (American Civil War)|Union]] forces prevailed. But the war shut down trade with the South, devastating the city's economy. Missouri was nominally a slave state, but its economy did not depend on slavery, and it never [[secession|seceded]] from the Union. The arsenal at St. Louis was used during the war to construct ironclad ships for the Union. |

|||

On August 22, 1876, the city of St. Louis voted to [[urban secession|secede]] from [[St. Louis County, Missouri|St. Louis County]] and become an independent city, and, following a recount of the votes in November, officially did so in March 1877.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.stlmag.com/news/politics/st-louis-great-divorce-history-city-county-split-attempt-to-get-back-together/ |title=St. Louis' Great Divorce: A complete history of the city and county separation and attempts to get back together |date=March 8, 2019 |last=Cooperman |first=Jeannette |website=[[St. Louis Magazine]] |access-date=April 8, 2021 |archive-date=April 20, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210420161447/https://www.stlmag.com/news/politics/st-louis-great-divorce-history-city-county-split-attempt-to-get-back-together/ |url-status=live}}</ref> The [[1877 St. Louis general strike]] caused significant upheaval, in a fight for the eight-hour day and the banning of child labor.<ref>{{cite book |last1=McCabe |first1=James Dabney |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=auNCAAAAIAAJ |title=The History of the Great Riots: The Strikes and Riots on the Various Railroads of the United States and in the Mining Regions Together with a Full History of the Molly Maguires |last2=Winslow |first2=Edward Martin |year=1877 |location=[[Philadelphia]] |publisher=National Publishing Company|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161124212529/https://books.google.com/books?id=auNCAAAAIAAJ |archive-date=November 24, 2016 |url-status=live}}</ref>{{pn|date=April 2024}} |

|||

===St. Louis during the [[Gilded Age]]=== |

|||

On [[July 4]], [[1876]] the City of St. Louis voted to [[urban secession|secede]] from [[St. Louis County, Missouri|St. Louis County]] and become an independent city. At that time the County was primarily rural and sparsely populated, and the fast-growing City did not want to spend their tax dollars on infrastructure and services for the inefficient county. The move also allowed some in St. Louis government to increase their political power. |

|||

Industrial production continued to increase during the late 19th century. Major corporations such as the [[Anheuser-Busch]] brewery, [[Ralston Purina]] company and [[Desloge Consolidated Lead Company]] were established at St. Louis which was also home to several [[brass era]] automobile companies, including the [[Success Automobile Manufacturing Company]];<ref>Clymer, Floyd. ''Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877–1925'' (New York: Bonanza Books, 1950), p. 32.</ref> St. Louis is the site of the [[Wainwright Building]], a skyscraper designed in 1892 by architect [[Louis Sullivan]]. |

|||

{{Quote_box| |

|||

width=250px |

|||

|align=left |

|||

|quote="The City of St. Louis has affected me more deeply than any other environment has ever done, I consider myself fortunate to have been born here, rather than in Boston, or New York, or London." |

|||

|source=[[T.S. Eliot]] on St. Louis |

|||

|}} |

|||

===20th century=== |

|||

As St. Louis grew and prospered during the late 19th and early 20th Century, the city produced a number of notable people in the fields of business and literature. The [[Ralston-Purina]] company (headed by the [[John Danforth|Danforth Family]]) was headquartered in the city, and [[Anheuser-Busch]], the world's largest brewery, remains a fixture of the city's economy. The City was home to both [[International Shoe]] and the [[Brown Shoe Company]]. Notable residents in the field of literature included poets [[Sara Teasdale]], and [[T.S. Eliot]] as well as playwright [[Tennessee Williams]]. Eliot always spoke fondly of his hometown, while Williams despised the city. |

|||

{{Main|History of St. Louis (1905–1980)}} |

|||

[[File:Louisiana_Purchase_Exposition_St._Louis_1904.jpg|thumb|The Government Building is at the [[Louisiana Purchase Exposition|1904 World's Fair]].]] |

|||

In 1900, the entire streetcar system was shut down by a [[St. Louis streetcar strike of 1900|several months-long strike]], with significant unrest occurring in the city & violence against the striking workers.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Arenson |first=Adam |title=The great heart of the republic: St. Louis and the cultural Civil War |date=2015 |publisher=University of Missouri Press |isbn=978-0-8262-2064-6 |edition=1st |location=Columbia (Mo.)}}</ref> |

|||

In 1904, the city hosted the [[1904 World's Fair|World's Fair]] and the [[1904 Summer Olympics|Olympics]], becoming the first non-European city to host the games.<ref name="1904 Olympics">{{cite web |title=1904 Summer Olympics |publisher=International Olympic Committee |url=http://www.olympic.org/uk/games/past/index_uk.asp?OLGT=1&OLGY=1904 |access-date=April 20, 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080815120301/http://www.olympic.org/uk/games/past/index_uk.asp?OLGT=1&OLGY=1904 |archive-date=August 15, 2008 |url-status=live}}</ref> The formal name for the 1904 World's Fair was the [[Louisiana Purchase Exposition]]. Permanent facilities and structures remaining from the fair are located in [[Forest Park (St. Louis)|Forest Park]], and other notable structures within the park's boundaries include the [[Saint Louis Art Museum|St. Louis Art Museum]], the [[Saint Louis Zoo|St. Louis Zoo]] and the [[Missouri History Museum]], and Tower Grove Park and the Botanical Gardens. |

|||

St. Louis is one of several cities that claims to have the world's first [[skyscraper]]. The [[Wainwright Building]], a 10-story structure designed by [[Louis Sullivan]] and built in [[1892]], still stands at Chestnut and Seventh Streets and is today used by the State of [[Missouri]] as a government office building. |

|||

After the Civil War, social and racial discrimination in housing and employment were common in St. Louis. In 1916, during the [[Jim Crow laws|Jim Crow Era]], St. Louis passed a residential segregation ordinance<ref>Primm, James. ''Lion of the Valley: St. Louis, Missouri, 1764-1980''. St. Louis, Missouri: Missouri History Museum Press. 1998. Print</ref> saying that if 75% of the residents of a neighborhood were of a certain race, no one from a different race was allowed to move in.<ref>Smith, Jeffrey. "A Preservation Plan for St. Louis Part I: Historic Contexts" St. Louis, Missouri Cultural Resources Office. Web. Retrieved November 13, 2014.</ref> That ordinance was struck down in a court challenge, by the NAACP,<ref>NAACP. Papers of the NAACP Part 5. The Campaign against Residential Segregation. Frederick, MD: University Publications of America. 1986. Web</ref> after which racial covenants were used to prevent the sale of houses in certain neighborhoods to "persons not of Caucasian race".{{Clarify|date=December 2021|reason=Who are these racists and in what way did racial covenants restrict house sales?}} Again, St. Louisans offered a lawsuit in challenge, and such covenants were ruled unconstitutional by the [[United States Supreme Court|U.S. Supreme Court]] in 1948 in ''[[Shelley v. Kraemer]]''.<ref>"Shelley House". We Shall Overcome: Historic Places of the Civil Rights Movement. National Park Service. Retrieved November 10, 2014.</ref> |

|||

[[Nikola Tesla]] made the first public demonstration of radio communication here in [[1893]]. Addressing the [[Franklin Institute]] in [[Philadelphia, Pennsylvania]] and the [[National Electric Light Association]], he described and demonstrated in detail the principles of [[radio]] [[communication]]. The apparatus that he used contained all the elements that were incorporated into radio systems before the development of the [[vacuum tube]]. |

|||

In 1926, [[Douglass University]], a [[historically black university]] was founded by [[Benjamin F. Bowles|B. F. Bowles]] in St. Louis, and at the time no other college in St. Louis County admitted black students.<ref name=":1">{{Cite book |last=Early |first=Gerald Lyn |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IRLhcVs_pJUC |title=Ain't But a Place: An Anthology of African American Writings about St. Louis |date=1998 |publisher=Missouri History Museum |isbn=978-1-883982-28-7 |pages=307–314 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

In [[1896]], one of the deadliest and most destructive [[St. Louis-East St. Louis Tornado|tornadoes]] in U.S. history struck St. Louis and East St. Louis. The confirmed death toll is 255, with some estimates above 400, and injuries over 1,000. It left a mile wide continuous swath of destroyed homes, factories, mills, saloons, hospitals, schools, parks, churches, and railroad yards. Damages adjusted for inflation (1997 USD) make it the costliest tornado in U.S. history at an estimated $2.9 billion. Several other tornadoes have hit the city making it the worst tornado afflicted large city in the U.S.; with the most deadly and destructive occurring in 1871 (9 killed), 1890 (4 killed), 1904 (3 killed, 100 injured), 1927 (79 killed, 550 injured), and 1959 (21 killed, 345 injured). |

|||

In the first half of the 20th century, St. Louis was a destination in the [[Great Migration (African American)|Great Migration]] of African Americans from the rural South seeking better opportunities.{{cn|date=June 2024}} During [[World War II]], the [[NAACP]] campaigned to integrate war factories. In 1964, [[Civil and political rights|civil rights activists]] protested at the construction of the Gateway Arch to publicize their effort to gain entry for African Americans into the skilled trade unions, where they were underrepresented. The Department of Justice filed the first suit against the unions under the [[Civil Rights Act of 1964]].{{cn|date=June 2024}} |

|||

By the time of the [[1900]] census, St. Louis was the fourth largest city in the country [http://www.census.gov/population/documentation/twps0027/tab13.txt]. In [[1904]], the city hosted a [[Louisiana Purchase Exposition|World's Fair]] and the [[1904 Summer Olympics|Olympic Games]], making the [[United States]] the first [[English language|English]]-speaking country to host the [[Olympic Games|Olympics]]. Citizens of St. Louis still look back fondly on the events of 1904; there were several events held in 2004 to commemorate the centennial. |

|||

Between 1900 and 1929, St. Louis, had about 220 automakers, close to 10 percent of all American carmakers, about half of which built cars exclusively in St. Louis. Notable names include Dorris, Gardner and Moon.<ref>Hemmings, American City Business Journals, accessed January 22, 2022 [https://www.hemmings.com/stories/article/the-best-of-the-little-three-1903-st-louis-runabout] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220124144740/https://www.hemmings.com/stories/article/the-best-of-the-little-three-1903-st-louis-runabout|date=January 24, 2022}}</ref> |

|||

===Early 20th century=== |

|||

St. Louis was developed primarily as an industrial city. The [[uranium]] used in the [[Manhattan Project]] to build the first [[atomic bomb]] was refined in St. Louis by [[Mallinckrodt Chemical]] Co., starting in 1942. The industrial development that had fueled the city's growth in the 19th Century became a liability in the 20th Century. Through the 1950's, St. Louis struggled with a severe [[air pollution]] problem that was caused in part by the many coal-fired furnaces used to heat older homes. Many of the city's older neighborhoods were densely developed around the factories that formed the base of the city's economy. |

|||

In the first part of the century, St. Louis had some of the worst [[air pollution in the United States]]. In April 1940, the city banned the use of soft coal mined in nearby states. The city hired inspectors to ensure that only [[anthracite]] was burned. By 1946, the city had reduced air pollution by about 75%.<ref>{{cite news|last1=O'Neil|first1=Tim|title=Nov. 28 1939: The day 'Black Tuesday' rolled into St. Louis|url=https://www.stltoday.com/news/archives/nov-the-day-black-tuesday-rolled-into-st-louis/article_00c3b6cd-ba69-5a19-b498-fbc29f9630c4.html|access-date=December 8, 2016|work=St. Louis Post-Dispatch|date=November 28, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161202041856/http://www.stltoday.com/news/archives/nov-the-day-black-tuesday-rolled-into-st-louis/article_00c3b6cd-ba69-5a19-b498-fbc29f9630c4.html|archive-date=December 2, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

The city first lost population between the 1930 and 1940 census, and efforts to expand the city's boundaries to include some of the newly developing suburbs failed. The city reached its peak population at the 1950 census, reflecting a national housing shortage after World War II. The continued trend of suburban development and highway construction would lead to a decline in the city's population over the next several decades. As noted below, St. Louis' population is growing once again. |

|||

[[File:FromLacledesLanding.JPG|thumb|upright|The [[Gateway Arch|Arch]] (completed 1965) is visible from [[Laclede's Landing]], the remaining section of St. Louis's commercial riverfront.]] |

|||

===Recent developments=== |

|||

''[[De jure]]'' educational segregation continued into the 1950s, and ''[[de facto]]'' segregation continued into the 1970s, leading to a court challenge and interdistrict desegregation agreement. Students have been bused mostly from the city to county school districts to have opportunities for integrated classes, although the city has created magnet schools to attract students.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tcf.org/Publications/Education/freigovel.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040621102044/http://www.tcf.org/Publications/Education/freigovel.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-date=June 21, 2004|title=St. Louis: Desegregation and School Choice in the Land of Dred Scott|access-date=October 1, 2010}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Dsc087296zp.jpg|thumbnail|left|Washington Avenue Loft District]] |

|||

St. Louis, like many [[Midwestern]] cities, expanded in the early 20th century due to industrialization, which provided jobs to new generations of immigrants and migrants from the South. It reached its peak population of 856,796 at the 1950 census.<ref name="heritage">{{cite web|url=http://stlouis.missouri.org/heritage/History69/|title=Physical Growth of the City of St. Louis|access-date=July 27, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100726220826/http://stlouis.missouri.org/heritage/History69/|archive-date=July 26, 2010|url-status=live}}</ref> [[Suburbanization]] from the 1950s through the 1990s dramatically reduced the city's population, as did restructuring of industry and loss of jobs.{{cn|date=June 2024}} The effects of suburbanization were exacerbated by the small geographical size of St. Louis due to its earlier decision to become an independent city, and it lost much of its tax base. During the 19th and 20th century, most major cities aggressively annexed surrounding areas as residential development occurred away from the central city; however, St. Louis was unable to do so.{{cn|date=June 2024}} |

|||

Recently, there has been a significant upturn in construction in downtown St. Louis. [[The Bottle District]], an entertainment district named after a large Vess soda bottle that stands near [[Interstate 70]], will open in spring [[2007]] and will be located in an area just north of the Edward Jones Dome. The St. Louis Cardinals' new [[Busch Stadium]] opened in 2006. [[Ballpark Village]] will be built where the former [[Busch Memorial Stadium|Busch Stadium]] stood. For several years, the [[Washington Avenue Loft District]] has been [[gentrification|gentrifying]] with an expanding corridor along Washington Avenue from the Edwards Jones Dome westward almost two dozen blocks. Rehabilitation of other downtown areas is planned, such as around the Old Post Office and Cupples warehouses. The Forest Park Southeast neighborhood near the Missouri Botanical Garden and the old Gaslight Square district are also going through extensive renovations. |

|||

Several [[urban renewal]] projects were built in the 1950s, as the city worked to replace old and substandard housing. Some of these were poorly designed and resulted in problems. One prominent example, [[Pruitt–Igoe]], became a symbol of failure in public housing, and was torn down less than two decades after it was built.{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} The degradation and razing of [[Mill Creek Valley]] in this time was featured as an example of disenfranchisement in the 2024 Reparations Commission Report.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Hays |first=Gabrielle |date=2024-12-04 |title=In St. Louis, a new reparations report details how the city can act on racial injustice |url=https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/in-st-louis-a-new-reparations-report-details-how-the-city-can-act-on-racial-injustice |access-date=2024-12-05 |website=PBS News |language=en-us}}</ref> |

|||

St. Louis' population is growing again following a half-century of decline. As of 2005, St. Louis' population has grown over what it was at the time of the 2000 Census. |

|||

Since the 1980s, several revitalization efforts have focused on [[Downtown St. Louis]].{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

|||

===21st century=== |

|||

{{Main|History of St. Louis (1981–present)}} |

|||

The urban revitalization projects that started in the 1980s continued into the new century. The city's [[Washington Avenue Historic District (St. Louis, Missouri)|old garment district]], centered on Washington Avenue in the [[Downtown St. Louis|Downtown]] and [[Downtown West, St. Louis|Downtown West]] neighborhoods, experienced major development starting in the late 1990s as many of the old factory and warehouse buildings were converted into lofts. The [[American Planning Association]] designated Washington Avenue as one of 10 Great Streets for 2011.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2011-10-04 |title=Washington Avenue is Named "Great Street" by American Planning Association |url=https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/government/departments/mayor/news/Washington-Avenue-is-Named-Great-Street.cfm |access-date=2023-11-29 |website=stlouis-mo.gov |language=en |archive-date=January 14, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240114205234/https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/government/departments/mayor/news/Washington-Avenue-is-Named-Great-Street.cfm |url-status=live }}</ref> The [[Cortex Innovation Community]], located within the city's [[Central West End, St. Louis|Central West End]] neighborhood, was founded in 2002 and has become a multi-billion dollar economic engine for the region, with companies such as Microsoft and Boeing currently leasing office space.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Kukuljan |first=Steph |date=2022-03-21 |title=Cortex, facing unprecedented challenges, plots new course. 'This is an evolution,' says chief. |url=https://www.stltoday.com/news/local/metro/cortex-facing-unprecedented-challenges-plots-new-course-this-is-an-evolution-says-chief/article_db2258b1-9860-58d1-94cf-bbff7160bca3.html |access-date=2023-11-15 |website=STLtoday.com |language=en |archive-date=November 15, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231115030941/https://www.stltoday.com/news/local/metro/cortex-facing-unprecedented-challenges-plots-new-course-this-is-an-evolution-says-chief/article_db2258b1-9860-58d1-94cf-bbff7160bca3.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Bean |first=Randy |title=Meet Me In St. Louis – The Reemergence Of An Innovation Hub |url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/ciocentral/2020/03/26/meet-me-in-st-louis--the-reemergence-of-an-innovation-hub/ |access-date=2023-11-15 |website=Forbes |language=en |archive-date=November 15, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231115030952/https://www.forbes.com/sites/ciocentral/2020/03/26/meet-me-in-st-louis--the-reemergence-of-an-innovation-hub/ |url-status=live }}</ref> The [[Forest Park Southeast, St. Louis|Forest Park Southeast]] neighborhood in the central corridor has seen major investment starting in the early 2010s. Between 2013 and 2018, over $50 million worth of residential construction has been built in the neighborhood.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Moore |first=Doug |date=2018-04-29 |title=These longtime St. Louis residents are digging in as their neighborhood takes off |url=https://www.stltoday.com/news/local/metro/these-longtime-st-louis-residents-are-digging-in-as-their-neighborhood-takes-off/article_5e8244f1-742d-5a7a-b173-fff8f930f088.html |access-date=2023-11-29 |website=STLtoday.com |language=en |archive-date=January 20, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240120002744/https://www.stltoday.com/news/local/metro/these-longtime-st-louis-residents-are-digging-in-as-their-neighborhood-takes-off/article_5e8244f1-742d-5a7a-b173-fff8f930f088.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The population of the neighborhood has increased by 19% from the 2010 to 2020 Census.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Forest Park South East Census Data {{!}} City of St. Louis |url=https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/government/departments/planning/research/census/data/neighborhoods/neighborhood.cfm |access-date=2023-11-29 |website=stlouis-mo.gov |language=en |archive-date=May 18, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220518142148/https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/government/departments/planning/research/census/data/neighborhoods/neighborhood.cfm |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

The [[St. Louis Rams]] of the [[National Football League]] controversially returned to [[Los Angeles]] in 2016. The city of St. Louis sued the NFL in 2017, alleging the league breached its own relocation guidelines to profit at the expense of the city. In 2021, the NFL and Rams owner [[Stan Kroenke]] agreed to settle out of court with the city for $790 million.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2016-01-06 |title=Rams owner Kroenke rips St. Louis market as he seeks LA move |url=https://apnews.com/article/f8703bf3a7d7495ebea1884c8a71f04e |access-date=2023-11-29 |website=AP News |language=en |archive-date=May 24, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230524060119/https://apnews.com/article/f8703bf3a7d7495ebea1884c8a71f04e |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2021-11-24 |title=$790M settlement in lawsuit over Rams' St. Louis departure |url=https://apnews.com/article/nfl-sports-business-los-angeles-st-louis-1cff28235e3d10777a86103d983cd2f1 |access-date=2023-11-29 |website=AP News |language=en |archive-date=November 24, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231124092827/https://apnews.com/article/nfl-sports-business-los-angeles-st-louis-1cff28235e3d10777a86103d983cd2f1 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

==Geography== |

==Geography== |

||

{{ |

{{Main|Geography of St. Louis}} |

||

[[Image:St_Louis_Rivers.png|right|thumb|200px|<small>The Rivers around St. Louis</small>]] |

|||

St. Louis is located at {{coor dms|38|38|53|N|90|12|44|W|region:GR}} (38.648056, -90.212222).{{GR|1}} |

|||

===Landmarks=== |

|||

The city is built primarily on [[bluff]]s and terraces that rise 100-200 feet above the western banks of the [[Mississippi River]], just south of the [[Missouri River|Missouri]]-Mississippi confluence. Much of the area is a fertile and gently rolling prairie that features low hills and broad, shallow valleys. Both the Mississippi River and the Missouri River have cut large valleys with wide flood plains. |

|||

{{Further|Landmarks of St. Louis}} |

|||

{{see also|List of public art in St. Louis}} |

|||

{| class="wikitable sortable" |

|||

|- |

|||

!Name |

|||

!Description |

|||

!Photo |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Gateway Arch]] |

|||

|At {{convert|630|ft|m}}, the Gateway Arch is the world's tallest [[arch]] and tallest human-made [[monument]] in the [[Western Hemisphere]].<ref>{{cite book |last=Lohraff |first=Kevin |year=2009 |title=Hiking Missouri |edition=2nd |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yO83BlN64sIC&pg=PA73 |location=Champaign, IL |publisher=Human Kinetics |isbn=978-0-7360-7588-6 |page=73 |access-date=November 1, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170102210822/https://books.google.com/books?id=yO83BlN64sIC&pg=PA73 |archive-date=January 2, 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref> Built as a monument to the [[westward expansion of the United States]], it is the centerpiece of [[Gateway Arch National Park]] which was known as Jefferson National Expansion Memorial until 2018. |

|||

|[[File:Gateway_Arch_at_Sunset_(cropped).jpg|150x150px]] |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Saint Louis Art Museum|St. Louis Art Museum]] |

|||

|Built for the [[Louisiana Purchase Exposition|1904 World's Fair]], with a building designed by [[Cass Gilbert]], the museum houses paintings, sculptures, and cultural objects. The museum is located in [[Forest Park (St. Louis)|Forest Park]], and admission is free. |

|||

|[[File:St._Louis_Art_Museum.JPG|150x150px]] |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Missouri Botanical Garden]] |

|||

|Founded in 1859, the Missouri Botanical Garden is one of the oldest botanical institutions in the United States and a [[National Historic Landmark]]. It spans 79 acres in the [[Shaw, St. Louis|Shaw]] neighborhood, including a {{convert|14|acre|ha|abbr=off|adj=on}} [[Japanese garden]] and the Climatron [[geodesic dome]] conservatory. |

|||

|[[File:Missouri_Botanical_Garden.jpg|150x150px]] |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Cathedral Basilica of Saint Louis (St. Louis)|Cathedral Basilica of St. Louis]] |

|||

|Dedicated in 1914, it is the mother church of the [[Roman Catholic Archdiocese of St. Louis|Archdiocese of St. Louis]] and the seat of its [[archbishop]]. The church is known for its large [[mosaic]] installation (which is one of the largest in the Western Hemisphere with 41.5 million pieces), burial crypts, and its outdoor sculpture. |

|||

|[[File:Cathedral_Basilica_of_St._Louis.JPG|150x150px]] |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[City Hall (St. Louis, Missouri)|City Hall]] |

|||

|Located in [[Downtown West, St. Louis|Downtown West]], City Hall was designed by [[Harvey Ellis]] in 1892 in the [[Renaissance Revival Architecture|Renaissance Revival]] style. It is reminiscent of the [[Hôtel de Ville, Paris]]. |

|||

|[[File:St_Louis_MO_City_Hall_20150905-100.jpg|150x150px]] |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[St. Louis Public Library|Central Library]] |

|||

|Completed in 1912, the Central Library building was designed by [[Cass Gilbert]]. It serves as the main location for the [[St. Louis Public Library]]. |

|||

|[[File:STLCentrallibrary.jpg|150x150px]] |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[City Museum]] |

|||

|City Museum is a play house museum, consisting largely of repurposed architectural and industrial objects, housed in the former International Shoe building in the [[Washington Avenue Loft District]]. |

|||

|[[File:City_Museum_outdoor_structures.jpg|150x150px]] |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Old Courthouse (St. Louis)|Old Courthouse]] |

|||

|Built in the 19th century, it served as a federal and state courthouse. The [[Scott v. Sandford]] case (resulting in the Dred Scott decision) was tried at the courthouse in 1846. |

|||

|[[File:Old_St_Louis_County_Courthouse_20150905_046-047.jpg|150x150px]] |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[St. Louis Science Center]] |

|||

|Founded in 1963, it includes a [[science museum]] and a [[planetarium]], and is situated in [[Forest Park (St. Louis)|Forest Park]]. Admission is free. It is one of two science centers in the United States which offers free general admission. |

|||

|[[File:McDonnellPlanetarium.jpg|frameless|upright=0.65]] |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[St. Louis Symphony]] |

|||

|Founded in 1880, the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra is the second oldest symphony orchestra in the United States, preceded by the [[New York Philharmonic]]. Its principal concert venue is [[Powell Symphony Hall]]. |

|||

|[[File:782px-Powell_Symphony_Hall.jpg|frameless|upright=0.65]] |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Union Station (St. Louis)|Union Station]] |

|||

|Built in 1888, it was the city's main passenger intercity train terminal. Once the world's largest and busiest train station, it was converted in the 1980s into a hotel, [[shopping mall|shopping center]], and entertainment complex. Today, it also continues to serve local rail ([[MetroLink (St. Louis)|MetroLink]]) transit passengers, with [[Amtrak]] service nearby. On December 25, 2019, the St. Louis Aquarium opened inside Union Station. The St. Louis Wheel, a 200 ft 42 gondola ferris wheel, is also located at Union Station. |

|||

|[[File:Grand_Hall_at_Union_Station.jpg|150x150px]] |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Saint Louis Zoo|St. Louis Zoo]] |

|||

|Built for the [[Louisiana Purchase Exposition|1904 World's Fair]], it is recognized as a leading zoo in animal management, research, conservation, and education. It is located in [[Forest Park (St. Louis)|Forest Park]], and admission is free. |

|||

|[[File:St. Louis Zoo sign.jpg|150x150px]] |

|||

|} |

|||

===Architecture=== |

|||

[[Limestone]] and [[dolomite]] of the [[Mississippian]] [[geologic time scale|epoch]] underlies the area and much of the city is a [[karst]] area, with numerous sinkholes and caves, although most of the caves have been sealed shut; many springs are visble along the riverfront. Significant deposits of [[coal]], [[brick]] [[clay]], and [[millerite]] ore were once mined in the city, and the predominant surface rock, the ''St. Louis Limestone'', is used as dimension stone and rubble for construction. |

|||

{{main|Architecture of St. Louis}} |

|||

{{see also|List of tallest buildings in St. Louis}} |

|||

[[File:Wainwright building st louis USA.jpg|thumb|upright|The [[Wainwright Building]] (1891), is an important [[Early skyscrapers|early skyscraper]] designed by [[Louis Sullivan]].]] |

|||

[[File:Lafayette Square St-Louis.jpg|thumb|Many houses in [[Lafayette Square, St. Louis|Lafayette Square]] are built with a blending of Greek Revival, Federal and Italianate styles.]] |

|||

The architecture of St. Louis exhibits a variety of commercial, residential, and monumental [[architecture]]. St. Louis is known for the [[Gateway Arch]], the tallest [[monument]] constructed in the United States at {{convert|630|ft|m}}.<ref name="huffingtonpost.com">{{cite news |url=https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/03/21/st-louis-reasons-to-love_n_4993763.html |work=Huffington Post |first=Marcos |last=Saldivar |title=26 Reasons St. Louis Is America's Hidden Gem |access-date=March 24, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140324041004/http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/03/21/st-louis-reasons-to-love_n_4993763.html |archive-date=March 24, 2014 |url-status=live}}</ref> The Arch pays homage to [[Thomas Jefferson]] and St. Louis's position as the gateway to the West. Architectural influences reflected in the area include [[French Colonial]], [[Architecture of Germany|German]], [[Architecture of the United States|early American]], and [[Modern architecture|modern architectural]] styles. |

|||

Several examples of religious structures are extant from the pre-Civil War period, and most reflect the common residential styles of the time. Among the earliest is the [[Basilica of St. Louis, King of France]] (referred to as the ''Old Cathedral''). The Basilica was built between 1831 and 1834 in the Federal style. Other religious buildings from the period include SS. Cyril and Methodius Church (1857) in the Romanesque Revival style and [[Christ Church Cathedral (St. Louis, Missouri)|Christ Church Cathedral]] (completed in 1867, designed in 1859) in the Gothic Revival style.{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

|||

The ''St. Louis [[Geologic fault]]'' is exposed along the bluffs and was the source of several historic minor earthquakes; it is part of the ''St. Louis [[Anticline]]'' which has some [[petroleum]] and [[natural gas]] deposits outside of the city. St. Louis is also just north of the [[New Madrid Seismic Zone]] which in 1811-12 produced a [[New Madrid Earthquake|series of earthquakes]] that are the largest known in the contiguous United States. Seismologists estimate 90% probability of a magnitude [[Richter scale|6.0]] earthquake by 2040 and 7-10% probability of a magnitude 8.0 [http://www.livescience.com/forcesofnature/050622_new_madrid.html], such tremors could create significant damage across a large region of the central U.S. including St. Louis. |

|||

A few civic buildings were constructed during the early 19th century. The original St. Louis courthouse was built in 1826 and featured a Federal style stone facade with a rounded portico. However, this courthouse was replaced during renovation and expansion of the building in the 1850s. The [[Old Courthouse (St. Louis, Missouri)|Old St. Louis County Courthouse]] (known as the ''Old Courthouse'') was completed in 1864 and was notable for having a [[cast iron]] dome and for being the tallest structure in Missouri until 1894. Finally, a customs house was constructed in the Greek Revival style in 1852, but was demolished and replaced in 1873 by the [[United States Customhouse and Post Office (St. Louis, Missouri)|U.S. Customhouse and Post Office]].{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

|||

Near the southern boundary of the City of St. Louis (separating it from [[St. Louis County, Missouri|St. Louis County]]) is the [[River des Peres]], virtually the only river or stream within the city limits that is not entirely underground. Most of River des Peres was either channelized or put underground in the 1920s and early 1930s. The lower section of the river was the site of some of the worst flooding of the [[Great Flood of 1993]]. |

|||

Because much of the city's commercial and industrial development was centered along the riverfront, many pre-Civil War buildings were demolished during construction of the Gateway Arch. The city's remaining architectural heritage of the era includes a multi-block district of cobblestone streets and brick and cast-iron warehouses called [[Laclede's Landing]]. Now popular for its restaurants and nightclubs, the district is located north of Gateway Arch along the riverfront. Other industrial buildings from the era include some portions of the [[Anheuser–Busch#St. Louis headquarters and brewery|Anheuser-Busch Brewery]], which date to the 1860s.{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

|||

Near the central, western boundary of the city is [[Forest Park (St. Louis)|Forest Park]], site of the 1904 [[World's fair]], the [[Louisiana Purchase Exposition]] of [[1904]], and the [[1904 Summer Olympics]], the first [[Olympic Games]] held in North America. At the time, St. Louis was the fourth most populous city in the United States. |

|||

St. Louis saw a vast expansion in variety and number of religious buildings during the late 19th century and early 20th century. The largest and most ornate of these is the [[Cathedral Basilica of St. Louis]], designed by [[Thomas P. Barnett]] and constructed between 1907 and 1914 in the [[Neo-Byzantine]] style. The St. Louis Cathedral, as it is known, has one of the largest mosaic collections in the world. Another landmark in religious architecture of St. Louis is the [[St. Stanislaus Kostka Church (St. Louis, Missouri)|St. Stanislaus Kostka]], which is an example of the [[Polish Cathedral style]]. Among the other major designs of the period were [[St. Alphonsus Catholic Church, St. Louis|St. Alphonsus Liguori]] (known as ''The Rock Church'') (1867) in the Gothic Revival and [[Second Presbyterian Church (St. Louis, Missouri)|Second Presbyterian Church of St. Louis]] (1900) in [[Richardsonian Romanesque]].{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

|||

The [[Missouri River]] forms the northern border of [[St. Louis County, Missouri|St. Louis County]], exclusive of a few areas where the river has changed its course. The [[Meramec River]] forms most of its southern border. To the east is the City and the [[Mississippi River]]. |

|||

By the [[United States Census, 1900|1900 census]], St. Louis was the fourth largest city in the country. In 1904, the city hosted a [[world's fair]] at [[Forest Park (St. Louis, Missouri)|Forest Park]] called the [[Louisiana Purchase Exposition]]. Its architectural legacy is somewhat scattered. Among the fair-related cultural institutions in the park are the [[Saint Louis Art Museum|St. Louis Art Museum]] designed by [[Cass Gilbert]], part of the remaining lagoon at the foot of Art Hill, and the Flight Cage at the [[St. Louis Zoo]]. The [[Missouri History Museum]] was built afterward, with the profit from the fair. But 1904 left other assets to the city, like [[Theodore Link]]'s 1894 [[St. Louis Union Station]], and an improved Forest Park.{{Citation needed|date=November 2024}} |

|||

According to the [[United States Census Bureau]], the city has a total area of 171.3 [[square kilometre|km²]] (66.2 [[square mile|mi²]]). 160.4 km² (61.9 mi²) of it is land and 11.0 km² (4.2 mi² or 6.39%) of it is water. |

|||