Homo erectus: Difference between revisions

m Homo erectus |

Dudley Miles (talk | contribs) Deleted cladograms not supported by sources |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Extinct species of archaic human}} |

|||

{{redirect|H. erectus|the seahorse species|Hippocampus erectus|the 2007 comedy film|Homo Erectus (film)|1997 album|Homo erectus (album)}} |

|||

{{redirect| |

{{redirect|H. erectus|other uses|H. erectus (disambiguation)|and|Homo erectus (disambiguation)}} |

||

{{redirect|Pithecanthropus erectus|the song and album by Charles Mingus|Pithecanthropus Erectus (album)}} |

|||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

|||

{{pp-move}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2013}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=September 2020}} |

|||

{{italic title}} |

|||

{{Speciesbox |

|||

{{Taxobox |

|||

| fossil_range = {{Fossil range|2|0.1}}<small>[[Early Pleistocene]] – [[Late Pleistocene]]<ref name=Rizal/></small> |

|||

| name = ''Homo erectus'' |

|||

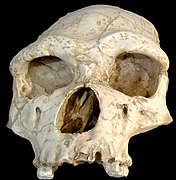

| image = Peking Man Skull (replica) presented at Paleozoological Museum of China.jpg |

|||

| fossil_range = {{Fossil range|1.9|0.07}}<small>Early [[Pleistocene]] – Middle [[Pleistocene]]</small> |

|||

| image_caption = Replica of the skull of [[Peking Man]] at the [[Paleozoological Museum of China]] |

|||

| image = Homme de Tautavel 01-08.jpg |

|||

| |

| extinct = yes |

||

| taxon = Homo erectus |

|||

| image_caption = Reconstruction of a specimen from Tautavel, France |

|||

| authority = ([[Eugène Dubois|Dubois]], 1893) |

|||

| regnum = [[Animal]]ia |

|||

| synonyms = * ''[[Java Man|Anthropopithecus erectus]]'' <small>[[Eugène Dubois|Dubois]], 1893</small> |

|||

| phylum = [[Chordate|Chordata]] |

|||

* ''[[Java Man|Pithecanthropus erectus]]'' <small>([[Eugène Dubois|Dubois]], 1893)</small> |

|||

| classis = [[Mammal]]ia |

|||

* ''[[Peking Man|Sinanthropus pekinensis]]'' |

|||

| ordo = [[Primates]] |

|||

* ''[[Solo Man|Javanthropus soloensis]]'' |

|||

| familia = [[Hominid]]ae |

|||

* ''[[Tighennif|Atlanthropus mauritanicus]]'' |

|||

| genus = ''[[Homo (genus)|Homo]]'' |

|||

* (?) ''[[Homo ergaster|Telanthropus capensis]]'' |

|||

| species = '''''H. erectus''''' |

|||

* (?) ''[[Homo georgicus]]'' |

|||

* (?) ''[[Tautavel Man|Homo tautavelensis]]'' |

|||

| binomial_authority = ([[Eugène Dubois|Dubois]], 1892) |

|||

}} |

|||

| synonyms = |

|||

*† ''[[Java Man|Anthropopithecus erectus]]'' |

|||

*† ''[[Java Man|Pithecanthropus erectus]]'' |

|||

*† ''[[Sinanthropus pekinensis]]'' |

|||

*† ''Javanthropus soloensis'' |

|||

*† ''Meganthropus paleojavanicus'' |

|||

*† ''Telanthropus capensis'' |

|||

*† ''Homo georgicus'' |

|||

*† ''[[Homo ergaster]]''? |

|||

}} |

|||

'''''Homo erectus ''''' (meaning "upright man", from the Latin ''ērigere'', "to put up, set upright") is an extinct [[species]] of [[hominid]] that lived throughout most of the [[Pleistocene]] geological epoch. Its earliest fossil evidence dates to 1.9 million years ago and the most recent to 70,000 years ago. Its extinction is linked by some scientists to the [[Toba catastrophe theory|Toba super-eruption catastrophe]], but no sufficient case has been made to date for the idea. It is generally thought that ''H. erectus'' originated in [[Africa]] and spread from there, migrating throughout Eurasia as far as [[Georgia (country)|Georgia]], [[India]], [[Sri Lanka]], [[China]] and [[Java]].<ref name="Hazarika">{{cite news|last=Hazarika|first=Manji|title=''Homo erectus/ergaster'' and Out of Africa: Recent Developments in Paleoanthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology|date=16–30 June 2007|url=http://www.himalayanlanguages.org/files/hazarika/Manjil%20Hazarika%20EAA.pdf}}</ref><ref name="Chauhan">Chauhan, Parth R. (2003) [http://www.assemblage.group.shef.ac.uk/issue7/chauhan.html#distribution "Distribution of Acheulian sites in the Siwalik region"] in ''An Overview of the Siwalik Acheulian & Reconsidering Its Chronological Relationship with the Soanian – A Theoretical Perspective''. assemblage.group.shef.ac.uk</ref> But other scientists posit that the species rose first, or separately, in Asia. |

|||

'''''Homo erectus''''' ({{IPAc-en|ˌ|h|oʊ|m|oʊ|_|ə|'|r|ɛ|k|t|ə|s}} {{lit|[[:wikt:erectus|upright]] man}}) is an [[Extinction|extinct]] [[species]] of [[archaic human]] from the [[Pleistocene]], with its earliest occurrence about 2 million years ago.<ref name=Herries>{{cite journal | vauthors = Herries AI, Martin JM, Leece AB, Adams JW, Boschian G, Joannes-Boyau R, Edwards TR, Mallett T, Massey J, Murszewski A, Neubauer S, Pickering R, Strait DS, Armstrong BJ, Baker S, Caruana MV, Denham T, Hellstrom J, Moggi-Cecchi J, Mokobane S, Penzo-Kajewski P, Rovinsky DS, Schwartz GT, Stammers RC, Wilson C, Woodhead J, Menter C | display-authors = 6 | title = Contemporaneity of ''Australopithecus'', ''Paranthropus'', and early ''Homo erectus'' in South Africa | journal = Science | volume = 368 | issue = 6486 | pages = eaaw7293 | date = April 2020 | pmid = 32241925 | doi = 10.1126/science.aaw7293 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Its specimens are among the first recognizable members of the genus ''[[Homo]]''. |

|||

Debate also continues about the classification, ancestry, and progeny of ''Homo erectus'', especially vis-à-vis ''[[Homo ergaster]]'', with two major positions: 1) ''H. erectus'' is the same species as ''[[H. ergaster]]'', and thereby ''H. erectus'' is a direct ancestor of the later hominins including ''[[Homo heidelbergensis]]'', ''[[Homo neanderthalensis]]'', and ''[[Homo sapiens]]''; or, 2) it is in fact an [[Asia]]n species distinct from African ''H. ergaster''.<ref name="Hazarika"/><ref>See overview of theories on [[human evolution]].</ref><ref>Klein, R. (1999). ''The Human Career: Human Biological and Cultural Origins''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0226439631.</ref> |

|||

Several human species, such as ''[[H. heidelbergensis]]'' and ''[[H. antecessor]]'', appear to have evolved from ''H. erectus'', and [[Neanderthal]]s, [[Denisovan]]s, and [[modern humans]] are in turn generally considered to have evolved from ''H. heidelbergensis''.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dembo M, Radovčić D, Garvin HM, Laird MF, Schroeder L, Scott JE, Brophy J, Ackermann RR, Musiba CM, de Ruiter DJ, Mooers AØ, Collard M | display-authors = 6 | title = The evolutionary relationships and age of Homo naledi: An assessment using dated Bayesian phylogenetic methods | journal = Journal of Human Evolution | volume = 97 | pages = 17–26 | date = August 2016 | pmid = 27457542 | doi = 10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.04.008 | bibcode = 2016JHumE..97...17D | hdl = 2164/8796 | hdl-access = free }}</ref> ''H. erectus'' was the first human ancestor to spread throughout [[Eurasia]], with a continental range extending from the [[Iberian Peninsula]] to [[Java]]. Asian populations of ''H. erectus'' may be ancestral to ''[[H. floresiensis]]''<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = van den Bergh GD, Kaifu Y, Kurniawan I, Kono RT, Brumm A, Setiyabudi E, Aziz F, Morwood MJ | display-authors = 6 | title = Homo floresiensis-like fossils from the early Middle Pleistocene of Flores | journal = Nature | volume = 534 | issue = 7606 | pages = 245–248 | date = June 2016 | pmid = 27279221 | doi = 10.1038/nature17999 | bibcode = 2016Natur.534..245V | s2cid = 205249218 | author5-link = Adam Brumm }}</ref> and possibly to ''[[Homo luzonensis|H. luzonensis]]''.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Détroit F, Mijares AS, Corny J, Daver G, Zanolli C, Dizon E, Robles E, Grün R, Piper PJ | display-authors = 6 | title = A new species of Homo from the Late Pleistocene of the Philippines | journal = Nature | volume = 568 | issue = 7751 | pages = 181–186 | date = April 2019 | pmid = 30971845 | doi = 10.1038/s41586-019-1067-9 | s2cid = 106411053 | bibcode = 2019Natur.568..181D | url = https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02296712/file/Detroit_%26_al_2019_Nature_postprint.pdf }}</ref> The last known population of ''H. erectus'' is ''[[Solo Man|H. e. soloensis]]'' from Java, around 117,000–108,000 years ago.<ref name=Rizal>{{cite journal | vauthors = Rizal Y, Westaway KE, Zaim Y, van den Bergh GD, Bettis EA, Morwood MJ, Huffman OF, Grün R, Joannes-Boyau R, Bailey RM, Westaway MC, Kurniawan I, Moore MW, Storey M, Aziz F, Zhao JX, Sipola ME, Larick R, Zonneveld JP, Scott R, Putt S, Ciochon RL | display-authors = 6 | title = Last appearance of Homo erectus at Ngandong, Java, 117,000-108,000 years ago | journal = Nature | volume = 577 | issue = 7790 | pages = 381–385 | date = January 2020 | pmid = 31853068 | doi = 10.1038/s41586-019-1863-2 | s2cid = 209410644 }}</ref> |

|||

And there is another view—an alternative to 1): some [[palaeoanthropologist]]s consider ''H. ergaster'' to be a variety, that is, the "''African''" variety, of ''H. erectus'', and they offer the labels "''Homo erectus [[sensu stricto]]''" (strict sense) for the Asian species and "''Homo erectus [[sensu lato]]''" (broad sense) for the greater species comprising both Asian and African populations.<!------------><ref>{{cite journal|author=Antón, S. C. |year=2003|title=Natural history of Homo erectus|journal= Am. J. Phys. Anthropol.|volume=122|pages=126–170|doi=10.1002/ajpa.10399|quote=By the 1980s, the growing numbers of ''H. erectus'' specimens, particularly in Africa, led to the realization that Asian ''H. erectus'' (''H. erectus sensu stricto''), once thought so primitive, was in fact more derived than its African counterparts. These morphological differences were interpreted by some as evidence that more than one species might be included in ''H. erectus sensu lato'' (e.g., Stringer, 1984; Andrews, 1984; Tattersall, 1986; Wood, 1984, 1991a, b; Schwartz and Tattersall, 2000) ... Unlike the European lineage, in my opinion, the taxonomic issues surrounding Asian vs. African H. erectus are more intractable. The issue was most pointedly addressed with the naming of H. ergaster on the basis of the type mandible KNM-ER 992, but also including the partial skeleton and isolated teeth of KNM-ER 803 among other Koobi Fora remains (Groves and Mazak, 1975). Recently, this specific name was applied to most early African and Georgian H. erectus in recognition of the less-derived nature of these remains vis à vis conditions in Asian H. erectus (see Wood, 1991a, p. 268; Gabunia et al., 2000a). It should be noted, however, that at least portions of the paratype of H. ergaster (e.g., KNM-ER 1805) are not included in most current conceptions of that taxon. The ''H. ergaster'' question remains famously unresolved (e.g., Stringer, 1984; Tattersall, 1986; Wood, 1991a, 1994; Rightmire, 1998b; Gabunia et al., 2000a; Schwartz and Tattersall, 2000), in no small part because the original diagnosis provided no comparison with the Asian fossil record}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal | author=Suwa G; Asfaw B; Haile-Selassie Y; White T; Katoh S; WoldeGabriel G; Hart W; Nakaya H; Beyene Y| doi = 10.1537/ase.061203 | title = Early Pleistocene Homo erectus fossils from Konso, southern Ethiopia | journal = Anthropological Science | volume = 115 | issue = 2 | pages = 133 | year = 2007 | pmid = | pmc = }}</ref> |

|||

''H. erectus'' had a more modern gait and body proportions, and was the first human species to have exhibited a flat face, prominent nose, and possibly sparse body hair coverage. Though the species' brain size certainly exceeds that of ancestor species, capacity varied widely depending on the population. In earlier populations, brain development seemed to cease early in childhood, suggesting that offspring matured faster, thus limiting cognitive development. ''H. erectus'' was an [[apex predator]];<ref name="Ben-Dor2021">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ben-Dor M, Sirtoli R, Barkai R | title = The evolution of the human trophic level during the Pleistocene | journal = American Journal of Physical Anthropology | volume = 175 | issue = Suppl 72 | pages = 27–56 | date = August 2021 | pmid = 33675083 | doi = 10.1002/ajpa.24247 | doi-access = free }}</ref> sites generally show consumption of medium to large animals, such as [[bovine]]s or [[elephant]]s, and suggest the development of predatory behavior and coordinated hunting. ''H. erectus'' is associated with the [[Acheulean]] stone tool [[industry (archaeology)|industry]], and is postulated to have been the earliest human ancestor capable of using fire,<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Zohar |first1=Irit |last2=Alperson-Afil |first2=Nira |last3=Goren-Inbar |first3=Naama |last4=Prévost |first4=Marion |last5=Tütken |first5=Thomas |last6=Sisma-Ventura |first6=Guy |last7=Hershkovitz |first7=Israel |last8=Najorka |first8=Jens |date=2022-11-14 |title=Evidence for the cooking of fish 780,000 years ago at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-022-01910-z |journal=Nature Ecology & Evolution |volume=6 |issue=12 |pages=2016–2028 |language=en |doi=10.1038/s41559-022-01910-z |pmid=36376603 |bibcode=2022NatEE...6.2016Z |s2cid=253522354 |issn=2397-334X}}</ref> hunting and gathering in coordinated groups, caring for injured or sick group members, and possibly seafaring and art (though examples of art are controversial, and are otherwise rudimentary and few and far between). Intentional seafaring has also been a controversial claim.<ref name=":6">{{Cite journal |last=Botha |first=Rudolf |date=2024-04-16 |title=Did Homo erectus Have Language? The Seafaring Inference |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/cambridge-archaeological-journal/article/did-homo-erectus-have-language-the-seafaring-inference/DDCBA3076C04C50AFE23C2BF00DC461C#sec6 |journal=Cambridge Archaeological Journal |language=en |pages=1–17 |doi=10.1017/S0959774324000118 |issn=0959-7743|doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

A new debate appeared in 2013, with the documentation of the [[Dmanisi#Archaeological site|Dmanisi]] [[skulls]].<ref>[http://www.nature.com/news/skull-suggests-three-early-human-species-were-one-1.13972 Skull suggests three early human species were one : Nature News & Comment]</ref> Considering the large morphological variation among all Dmanisi skulls, researchers now suggest that several early human ancestors variously classified, for example, as ''[[Homo ergaster]]'', or ''[[Homo rudolfensis]]'', and perhaps even ''[[Homo habilis]]'', should instead be designated as ''Homo erectus''.<ref name=dmanisiskull5>{{cite journal |title=A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Evolutionary Biology of Early Homo |author=David Lordkipanidze, Marcia S. Ponce de Leòn, Ann Margvelashvili, Yoel Rak, G. Philip Rightmire, Abesalom Vekua, Christoph P. E. Zollikofer |journal=Science |date=18 October 2013 |volume= 342 |issue= 6156 |pages= 326–331 |doi= 10.1126/science.1238484 }}</ref><ref name=National_Geographic>{{cite news |last=Switek |first=Brian |date=17 October 2013 |title= Beautiful Skull Spurs Debate on Human History |url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/10/131017-skull-human-origins-dmanisi-georgia-erectus/ |newspaper= National Geographic |accessdate=22 September 2014 }}</ref> |

|||

''H. erectus'' males and females may have been roughly the same size as each other (i.e. exhibited reduced [[sexual dimorphism]]), which could indicate [[monogamy in animals|monogamy]] in line with general trends exhibited in primates. Size, nonetheless, ranged widely from {{cvt|146–185|cm|ftin|sigfig=1}} in height and {{cvt|40–68|kg}} in weight. It is unclear if ''H. erectus'' was anatomically capable of speech, though it is postulated they communicated using some [[Origin of language|proto-language]]. |

|||

==Origin== |

|||

[[File:Homo erectus.jpg|thumb|left|''Homo erectus'', [[University of Michigan Museum of Natural History]], Ann Arbor, Michigan]] |

|||

The first hypothesis of origin is that ''Homo erectus'' rose from the [[Australopithecina]] in [[East Africa]] sometime during—or perhaps even before—the [[Early Pleistocene]] geological epoch, which itself dates to 2.58 million years ago (''see'' below, "In a new finding, in 2013..."). From there it migrated, in part, by 2.0 mya, probably as a result of broad desertifying conditions developing then in eastern and northern Africa; it joined the migrations through the [[Sahara Pump Theory|"Saharan pump"]] and dispersed around much of the [[Old World]]. The fossil record shows that its development from about 1.8 mya to one mya was widely distributed: in Africa ([[Lake Turkana]] <!------> <ref>{{cite journal|authorlink=Kendrick Frazier|author=Frazier, Kendrick |url=http://www.csicop.org/si/2006-06/leakey.html|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20090110223159/http://www.csicop.org/si/2006-06/leakey.html|archivedate=2009-01-10|title= Leakey Fights Church Campaign to Downgrade Kenya Museum’s Human Fossils|journal=Skeptical Inquirer magazine |volume =30 |issue=6|date= Nov–Dec 2006}}</ref> <!-----> and [[Olduvai Gorge]]), the [[Caucasus#Prehistory|Transcaucasus]] ([[Dmanisi#Archaeological site|Dmanisi]] in [[Georgia (country)|Georgia]]), Indonesia ([[Sangiran]], [[Central Java]] and [[Trinil]], [[East Java]]), and in Vietnam, China ([[Zhoukoudian]] and [[Lantian Man|Shaanxi]]), and India.<ref>{{Cite book | author=Prins, Harald E. L.; Walrath, Dana and McBride, Bunny | title = Evolution and prehistory: the human challenge| publisher = Wadsworth Publishing| year = 2007| page = 162| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=LfYirloa_rUC&pg=PA16| isbn = 978-0-495-38190-7}}</ref> |

|||

==Taxonomy== |

|||

The second hypothesis is that ''H. erectus'' evolved in [[Eurasia]] and then migrated to Africa. They occupied the [[Dmanisi]] site from 1.85 million to 1.77 million years ago, which was about the same time or slightly before their earliest evidence in Africa.<ref name="doi10.1073/pnas.1106638108">{{Cite journal | last1 = Ferring | first1 = R. | last2 = Oms | first2 = O. | last3 = Agusti | first3 = J. | last4 = Berna | first4 = F. | last5 = Nioradze | first5 = M. | last6 = Shelia | first6 = T. | last7 = Tappen | first7 = M. | last8 = Vekua | first8 = A. | last9 = Zhvania | first9 = D. | last10 = Lordkipanidze | first10 = D. | doi = 10.1073/pnas.1106638108 | title = Earliest human occupations at Dmanisi (Georgian Caucasus) dated to 1.85-1.78 Ma | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences | volume = 108 | issue = 26 | pages = 10432 | year = 2011 | pmid = | pmc = }}</ref><ref>[http://www.dnaindia.com/scitech/report_new-discovery-suggests-homo-erectus-originated-from-asia_1552611 New discovery suggests Homo erectus originated from Asia]. Dnaindia.com. 8 June 2011.</ref> There are several proposed explanations of the dispersal of ''H. erectus georgicus''—including whether or not Africa is the source).<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.04.012|date=June 2011 |last1=Augusti |first1=Jordi |last2=Lordkipanidze |first2=David |title=How "African" was the early human dispersal out of Africa?|volume=30|issue=11–12 |pages=1338–1342 |journal=Quaternary Science Reviews}}</ref> |

|||

===Naming=== |

|||

{{further|Java Man}} |

|||

[[File:Pithecanthropus erectus-PeterMaas Naturalis.jpg|thumb|left|[[Java Man]] at [[Naturalis Biodiversity Center|Naturalis]]]] |

|||

Contrary to the view [[Charles Darwin]] expressed in his 1871 book ''[[Descent of Man]]'', many late-19th century evolutionary naturalists postulated that Asia, not Africa, was the birthplace of humankind as it is midway between Europe and America, providing optimal dispersal routes throughout the world (the [[Out of Asia theory]]). Among these was German naturalist [[Ernst Haeckel]], who argued that the first human species evolved on the now-disproven hypothetical continent "[[Lemuria (continent)|Lemuria]]" in what is now Southeast Asia, from a species he termed "''[[Pithecanthropus]] alalus''" ("speechless apeman").{{sfn|Theunissen|2012|loc=p. 6}} "Lemuria" had supposedly sunk below the [[Indian Ocean]], so no fossils could be found to prove this. Nevertheless, Haeckel's model inspired Dutch scientist [[Eugène Dubois]] to journey to the [[Dutch East Indies]]. Because no directed expedition had ever discovered human fossils (the few known had all been discovered by accident), and the economy was strained by the [[Long Depression]], the Dutch government refused to fund Dubois. In 1887, he enlisted in the [[Royal Netherlands Indies Army|Dutch East India Army]] as a medical officer, and was able to secure a post in 1887 in the Indies to search for his "[[missing link (human evolution)|missing link]]" in his spare time.{{sfn|Theunissen|2012|loc=p. 33}} On [[Java]], he found a skullcap in 1891 and a [[femur]] in 1892 ([[Java Man]]) dating to the [[late Pliocene]] or [[early Pleistocene]] at the [[Trinil]] site along the [[Solo River]], which he named ''Pithecanthropus erectus'' ("upright apeman") in 1893. He attempted unsuccessfully to convince the European scientific community that he had found an upright-walking ape-man. Given few fossils of ancient humans had even been discovered at the time, they largely dismissed his findings as a malformed non-human ape.<ref name=HsiaoPei2014>{{cite journal | vauthors = Yen HP | title = Evolutionary Asiacentrism, Peking man, and the origins of sinocentric ethno-nationalism | journal = Journal of the History of Biology | volume = 47 | issue = 4 | pages = 585–625 | year = 2014 | pmid = 24771020 | doi = 10.1007/s10739-014-9381-4 | s2cid = 23308894 }}</ref> |

|||

The significance of these fossils would not be realized until the 1927 discovery of what Canadian paleoanthropologist [[Davidson Black]] called "''Sinanthropus pekinensis''" (Peking Man) at the [[Zhoukoudian]] cave near [[Beijing]], China. Black lobbied across North America and Europe for funding to continue excavating the site,{{sfn|Sigmon|1981|loc=p. 64}} which has since become the most productive ''H. erectus'' site in the world.<ref name=Yang2014>{{cite book| vauthors = Yang L |year=2014|chapter=Zhoukoudian: Geography and Culture|title=Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology|pages=7961–7965|publisher=Springer Science+Business Media|isbn=978-1-4419-0466-9|doi=10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_1899}}</ref> Continued interest in Java led to further ''H. erectus'' fossil discoveries at Ngandong ([[Solo Man]]) in 1931, [[Mojokerto child|Mojokerto]] (Java Man) in 1936, and [[Sangiran]] (Java Man) in 1937. The Sangiran site yielded the best preserved Java Man skull.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Ciochon RL, Huffman OF |year=2014|chapter=Java Man|title=Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology|pages=4182–4188| veditors = Smith C |doi=10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_712|isbn=978-1-4419-0426-3|s2cid=241324984 }}</ref> German paleoanthropologist [[Franz Weidenreich]] provided much of the detailed description of the Chinese specimens in several monographs. The original specimens were lost during the [[Second Sino-Japanese War]] after an attempt to smuggle them out of China for safekeeping. Only [[plaster cast|casts]] remain. |

|||

==Discovery and representative fossils== |

|||

[[File:Skull of Homo erectus, Indian Museum, Kolkata.jpg|thumb|330px|Skull of Homo erectus, [[Indian Museum]]]] |

|||

The Dutch anatomist [[Eugène Dubois]] was fascinated by [[Charles Darwin|Darwin]]'s theory of evolution especially as it applied to humankind. In 1886, he set out for [[Asia]]—which then was the region accepted as the cradle of human evolution despite Darwin's theory of African origin; see {{section link|Haeckel|Research}}—to find a human ancestor. In 1891, his team discovered a human fossil on the island of [[Java]], [[Dutch East Indies]] (now [[Indonesia]]). Excavated from the bank of the [[Solo River]] at [[Trinil]], in [[East Java]], he named the species ''Pithecanthropus erectus''—from the Greek ''πίθηκος'',<ref>''pithecos''</ref> "ape", and ''ἄνθρωπος'',<ref>''anthropos''</ref> "man"—based on a skullcap (calotte) and a femur like that of ''Homo sapiens''. |

|||

Similarities between Java Man and Peking Man led [[Ernst Mayr]] to rename both as ''Homo erectus'' in 1950. Throughout much of the 20th century, anthropologists debated the role of ''H. erectus'' in [[human evolution]]. Early in the century, due in part to the discoveries at Java and Zhoukoudian, the belief that modern humans first evolved in Asia was widely accepted. A few naturalists—[[Charles Darwin]] the most prominent among them—theorized that humans' earliest ancestors were African. Darwin had pointed out that [[chimpanzee]]s and [[gorilla]]s, [[human]]s' closest relatives, evolved and exist only in Africa.<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Darwin CR |title=The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex|url= https://archive.org/details/descentmanandse03darwgoog |publisher=John Murray |year=1871 |isbn=978-0-8014-2085-6}}</ref> Darwin did not include [[orangutan]]s among the great [[ape]]s of the Old World, likely because he thought of orangutans as primitive humans rather than apes.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=van Wyhe |first1=John |last2=Kjærgaard |first2=Peter C. |date=2015-06-01 |title=Going the whole orang: Darwin, Wallace and the natural history of orangutans |journal=Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences |language=en |volume=51 |pages=53–63 |doi=10.1016/j.shpsc.2015.02.006 |pmid=25861859 |s2cid=20089470 |issn=1369-8486|doi-access=free }}</ref> While Darwin considered Africa as the most probable birthplace of human ancestors, he also made the following statement about the geographic location of human origins in his book ''The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex'': "... it is useless to speculate on this subject; for two or three anthropomorphous apes, one the Dryopithecus …, existed in Europe during the Miocene age; and since so remote a period the earth has certainly undergone many great revolutions, and there has been ample time for migration on the largest scale." (1889, pp. 155–156). |

|||

Dubois' 1891 find was the first fossil of a ''Homo''-species (or any hominin species) found as result of a directed expedition and search—and which was inspired by Darwin's radical theory that humans, like all other species, evolved from ancestral species, see [[human evolution]]. (The first found and recognized human fossil was the accidental discovery of ''[[Homo sapiens neanderthalensis]]'' in 1856, see [[List of human evolution fossils]].) The Java fossil aroused much public interest. It was dubbed by the popular press as ''[[Java Man]]''; but few scientists accepted Dubois' argument that his fossil was the [[Transitional fossil|transitional form]]—the so-called [[Transitional fossil#Missing links|"missing link"]]—between apes and humans.{{Sfn|Swisher|Curtis|Lewin|2000|p=70}} ''Java Man'' is now classified as ''Homo erectus''. |

|||

In 1949, the species was reported in [[Swartkrans]] Cave, South Africa, by South African paleoanthropologists [[Robert Broom]] and [[John Talbot Robinson]], who described it as "''Telanthropus capensis''".<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Curnoe D | title = A review of early Homo in southern Africa focusing on cranial, mandibular and dental remains, with the description of a new species (Homo gautengensis sp. nov.) | journal = Homo | volume = 61 | issue = 3 | pages = 151–177 | date = June 2010 | pmid = 20466364 | doi = 10.1016/j.jchb.2010.04.002 }}</ref> ''Homo'' fossils have also been reported from nearby caves, but their species designation has been a tumultuous discussion. A few North African sites have additionally yielded ''H. erectus'' remains, which at first were classified as "''Atlantanthropus mauritanicus''" in 1951.{{sfn|Sigmon|1981|loc=p. 231}} Beginning in the 1970s, propelled most notably by [[Richard Leakey]], more were being unearthed in East Africa predominantly at the [[Koobi Fora]] site, Kenya, and [[Olduvai Gorge]], Tanzania.{{sfn|Sigmon|1981|loc=p. 193}} |

|||

Most of the spectacular discoveries of ''H. erectus'' next took place at the [[Zhoukoudian|Zhoukoudian Project]], now known as the [[Peking Man]] Site, in Zhoukoudian, [[China]]. This site was first discovered by [[Johan Gunnar Andersson]] in 1921<!----------><ref name="doorKnock1">{{cite news | authorlink = | title = The First Knock at the Door| url = | format = | work = | publisher = Peking Man Site Museum | pages = | page = | date = | accessdate = | quote = In the summer of 1921, Dr. J.G. Andersson and his companions discovered this richly fossiliferous deposit through the local quarry men's guide. During examination he was surprised to notice some fragments of white quartz in tabus, a mineral normally foreign in that locality. The significance of this occurrence immediately suggested itself to him and turning to his companions, he exclaimed dramatically "Here is primitive man, now all we have to do is find him!"}}</ref> <!--------->and was first excavated in 1921, which produced two human teeth.<!----------><ref name="doorKnock2">{{cite news | authorlink = | title = The First Knock at the Door| url = | format = | work = | publisher = Peking Man Site Museum | pages = | page = | date = | accessdate = | quote = For some weeks in this summer and a longer period in 1923 Dr. Otto Zdansky carried on excavations of this cave site. He accumulated an extensive collection of fossil material, including two Homo erectus teeth that were recognized in 1926. So, the cave home of Peking Man was opened to the world.}}</ref> Canadian anatomist [[Davidson Black]]'s initial description (1921) of a lower molar as belonging to a previously unknown species (which he named ''[[Sinanthropus pekinensis]]'')<!--------><ref>from ''sino-'', a combining form of the Greek ''Σίνα'', "China", and the Latinate ''pekinensis'', "of Peking"</ref> <!---->prompted widely-publicized interest. Extensive excavations followed, which altogether uncovered 200 human fossils from more than 40 individuals including five nearly complete [[Calvaria (skull)|skullcaps]].<!-----------><ref name="historyMus5">{{cite news | authorlink = | title = Review of the History | url = | format = | work = | publisher = Peking Man Site Museum | pages = | page = | date = | accessdate = | quote = During 1927-1937, abundant human and animal fossils as well as artefact were found at Peking Man Site, it made the site to be the most productive one of the Homo erectus sites of the same age all over the world. Other localities in the vicinity were also excavated almost at the same time.}}</ref> German anatomist [[Franz Weidenreich]] provided much of the detailed description of this material in several monographs published in the journal ''Palaeontologica Sinica'' (Series D). |

|||

Archaic human fossils unearthed across Europe used to be assigned to ''H. erectus'', but have since been separated as ''[[Homo heidelbergensis|H. heidelbergensis]]'' as a result of British physical anthropologist [[Chris Stringer]]'s work.<ref name=Lumley2015>{{cite journal| vauthors = de Lumley MA |year=2015|title=L'homme de Tautavel. Un ''Homo erectus'' européen évolué. ''Homo erectus tautavelensis''|trans-title=Tautavel Man. An evolved European ''Homo erectus''. ''Homo erectus tautavelensis''|language=fr|journal=L'Anthropologie|volume=119|issue=3|pages=342–344|doi=10.1016/j.anthro.2015.06.001}}</ref> |

|||

Nearly all of the original specimens were lost during [[World War II]]; however, authentic casts were made by Weidenreich which exist at the [[American Museum of Natural History]] in [[New York]] and at the [[Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology]] in [[Beijing]], and are considered to be reliable evidence. |

|||

===Evolution=== |

|||

Throughout much of the 20th century, anthropologists debated the role of ''H. erectus'' in [[human evolution]]. Early in the century, due in part to the discoveries at Java and Zhoukoudian, it was widely accepted that modern humans first evolved in [[Asia]]. A few naturalists—Charles Darwin most prominent among them—theorized that humans' earliest ancestors were African: Darwin pointed out that chimpanzees and gorillas, humans' closest relatives, evolved and exist only in Africa.<ref>{{cite book|last=Darwin|first = Charles R.|title=The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex|publisher=John Murray|year=1871|isbn=0-8014-2085-7}}</ref> |

|||

{{further|Early human expansions out of Africa}} |

|||

{{Human timeline}} |

|||

[[File:Carte hachereaux.jpg|thumb|upright=1.5|Map of the distribution of Middle Pleistocene ([[Acheulean]]) [[Cleaver (tool)|cleaver]] finds]] |

|||

It has been proposed that ''H. erectus'' evolved from ''[[Homo habilis|H. habilis]]'' about 2 Mya, though this has been called into question because they coexisted for at least a half a million years. Alternatively, a group of ''H. habilis'' may have been [[reproductively isolated]], and only this group developed into ''H. erectus'' ([[cladogenesis]]).<ref name=Spoor2007/> |

|||

Because the earliest remains of ''H. erectus'' are found in both Africa and East Asia (in China as early as 2.1 Mya,<ref name = "Zhu_2018">{{cite journal | vauthors = Zhu Z, Dennell R, Huang W, Wu Y, Qiu S, Yang S, Rao Z, Hou Y, Xie J, Han J, Ouyang T | display-authors = 6 | title = Hominin occupation of the Chinese Loess Plateau since about 2.1 million years ago | journal = Nature | volume = 559 | issue = 7715 | pages = 608–612 | date = July 2018 | pmid = 29995848 | doi = 10.1038/s41586-018-0299-4 | s2cid = 49670311 | author10 = Han Jiangwei ({{lang|zh-Hans|韩江伟}}) | author11 = Ouyang Tingping ({{lang|zh-Hans|欧阳婷萍}}) | author4 = Wu Yi ({{lang|zh-Hans|吴翼}}) | author5 = Qiu Shifan ({{lang|zh-Hans|邱世藩}}) | author6 = Yang Shixia ({{lang|zh-Hans|杨石霞}}) | author7 = Rao Zhiguo ({{lang|zh-Hans|饶志国}}) | author3 = Huang Weiwen ({{lang|zh-Hans|黄慰文}}) | bibcode = 2018Natur.559..608Z | author8 = Hou Yamei ({{lang|zh-Hans|侯亚梅}}) | author9 = Xie Jiubing ({{lang|zh-Hans|谢久兵}}) | name-list-style = vanc }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal| vauthors = Barras C |year=2018|title=Tools from China are oldest hint of human lineage outside Africa|url=https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05696-8 |journal=Nature|doi=10.1038/d41586-018-05696-8|s2cid=188286436|issn=0028-0836}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hao L, Chao Rong L, Kuman K | year = 2017 | title = Longgudong, an Early Pleistocene site in Jianshi, South China, with stratigraphic association of human teeth and lithics | journal = Science China Earth | volume = 60 | issue = 3| pages = 452–462 | doi = 10.1007/s11430-016-0181-1 | bibcode = 2017ScChD..60..452L | s2cid = 132479732 }}</ref> in South Africa 2.04 Mya<ref name=Herries/><ref>{{cite web |title=Our direct human ancestor Homo erectus is older than we thought |url=https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2020-04/uoj-odh040120.php |website=EurekAlert |publisher=[[American Association for the Advancement of Science|AAAS]]}}</ref>), it is debated where ''H. erectus'' evolved. A 2011 study suggested that it was ''H. habilis'' who reached West Asia from Africa, that early ''H. erectus'' developed there, and that early ''H. erectus'' would then have dispersed from West Asia to East Asia ([[Peking Man]]), Southeast Asia ([[Java Man]]), back to Africa (''[[Homo ergaster]]''), and to Europe ([[Tautavel Man]]), eventually evolving into modern humans in Africa.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Ferring R, Oms O, Agustí J, Berna F, Nioradze M, Shelia T, Tappen M, Vekua A, Zhvania D, Lordkipanidze D | display-authors = 6 | title = Earliest human occupations at Dmanisi (Georgian Caucasus) dated to 1.85-1.78 Ma | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 108 | issue = 26 | pages = 10432–10436 | date = June 2011 | pmid = 21646521 | pmc = 3127884 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.1106638108 | doi-access = free | bibcode = 2011PNAS..10810432F }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.04.012|date=June 2011 | vauthors = Augusti J, Lordkipanidze D |title=How "African" was the early human dispersal out of Africa?|volume=30|issue=11–12 |pages=1338–1342 |journal=Quaternary Science Reviews|bibcode=2011QSRv...30.1338A }}</ref> Others have suggested that ''H. erectus''/''H. ergaster'' developed in Africa, where it eventually evolved into modern humans.<ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Rightmire GP |title= Human Evolution in the Middle Pleistocene: The Role of ''Homo heidelbergensis'' |year=1998 |journal=Evolutionary Anthropology|doi=10.1002/(sici)1520-6505(1998)6:6<218::aid-evan4>3.0.co;2-6 |volume=6 |issue=6 |pages=218–227|s2cid= 26701026 }}</ref><ref name="Asfawpmid11907576">{{cite journal | vauthors = Asfaw B, Gilbert WH, Beyene Y, Hart WK, Renne PR, WoldeGabriel G, Vrba ES, White TD | display-authors = 6 | title = Remains of Homo erectus from Bouri, Middle Awash, Ethiopia | journal = Nature | volume = 416 | issue = 6878 | pages = 317–320 | date = March 2002 | pmid = 11907576 | doi = 10.1038/416317a | s2cid = 4432263 | bibcode = 2002Natur.416..317A }}</ref> |

|||

===African genesis=== |

|||

[[File:Homo Georgicus IMG 2921.JPG|thumb|Dmanisi skull 3, Fossils skull [[D2700]] and [[D2735]] jaw, two of several found in [[Dmanisi]] in the [[Republic of Georgia|Georgian]] [[Caucasus]].]] |

|||

From the 1950s forward, numerous finds in East Africa confirmed the hypothesis of an African genesis, providing fossil evidence that the earliest [[Hominini|hominins]] originated there. It is now generally accepted that ''H. erectus'' descended from either: 1) the earliest hominin genera (such as ''[[Australopithecus]]'', and possibly ''[[Ardipithecus]]''—of which is still debated whether it is hominin or hominid); or 2) the earliest ''Homo''-species (such as ''[[Homo habilis]]'' or ''[[Homo ergaster]]''). East Africa provided [[sympatric]] coexistence for ''H. erectus'' and ''H. habilis'' for several hundred-thousand years, which tends to confirm the hypothesis that they represent separate lineages from a common ancestor; that is, the ancestral relationship between them was not [[anagenetic]], but was [[Cladogenesis|cladogenetic]], which here suggests that a subgroup population of ''habilis''—or of a common ancestor of ''habilis'' and ''erectus''—became [[reproductively isolated]] from the main-group population, eventually evolving into the new species ''Homo erectus''.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Implications of new early ''Homo'' fossils from Ileret, east of Lake Turkana, Kenya|author=F. Spoor, M. G. Leakey, P. N. Gathogo, F. H. Brown, S. C. Antón, I. McDougall, C. Kiarie, F. K. Manthi & L. N. Leakey|journal=Nature|issue= 7154|pages= 688–691|date=2007-08-09|doi=10.1038/nature05986|volume=448|pmid=17687323}} "A partial maxilla assigned to H. habilis reliably demonstrates that this species survived until later than previously recognized, making an ''anagenetic'' relationship with H. erectus unlikely" (Emphasis added).</ref> |

|||

''H. erectus'' had reached [[Sangiran]], Java, by 1.5 Mya,<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Husson |first1=Laurent |last2=Salles |first2=Tristan |last3=Lebatard |first3=Anne-Elisabeth |last4=Zerathe |first4=Swann |last5=Braucher |first5=Régis |last6=Noerwidi |first6=Sofwan |last7=Aribowo |first7=Sonny |last8=Mallard |first8=Claire |last9=Carcaillet |first9=Julien |last10=Natawidjaja |first10=Danny H. |last11=Bourlès |first11=Didier |last12=ASTER team |last13=Aumaitre |first13=Georges |last14=Bourlès |first14=Didier |last15=Keddadouche |first15=Karim |date=2022-11-08 |title=Javanese Homo erectus on the move in SE Asia circa 1.8 Ma |journal=Scientific Reports |language=en |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=19012 |doi=10.1038/s41598-022-23206-9 |issn=2045-2322 |pmc=9643487 |pmid=36347897|bibcode=2022NatSR..1219012H }}</ref> and a second and distinct wave of ''H. erectus'' had colonized [[Zhoukoudian]], China, about 780 [[Year#Abbreviations yr and ya|kya (thousand years ago)]]. Early teeth from Sangiran are bigger and more similar to those of basal (ancestral) Western ''H. erectus'' and ''H. habilis'' than to those of the derived Zhoukoudian ''H. erectus''. However, later Sangiran teeth seem to reduce in size, which could indicate a secondary colonization event of Java by the Zhoukoudian or some closely related population.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Zaim Y, Ciochon RL, Polanski JM, Grine FE, Bettis EA, Rizal Y, Franciscus RG, Larick RR, Heizler M, Eaves KL, Marsh HE | display-authors = 6 | title = New 1.5 million-year-old Homo erectus maxilla from Sangiran (Central Java, Indonesia) | journal = Journal of Human Evolution | volume = 61 | issue = 4 | pages = 363–376 | date = October 2011 | pmid = 21783226 | doi = 10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.04.009 | bibcode = 2011JHumE..61..363Z }}</ref> |

|||

In the 1950s, archaeologists [[John T. Robinson]] and [[Robert Broom]] named ''Telanthropus capensis'';<ref name="Robinson1953">{{cite journal |author=ROBINSON JT |title=The nature of Telanthropus capensis |journal=Nature |volume=171 |issue=4340 |pages=33 |date=January 1953 |pmid=13025468 |doi=10.1038/171033a0}}</ref> Robinson had discovered a jaw fragment in 1949 in [[Swartkrans]], [[South Africa]]. Later, Simonetta proposed to re-designate it to ''Homo erectus'', and Robinson agreed.<ref name="Grine2009">{{cite book | title = The First Humans: Origin and Early Evolution of the Genus Homo | author = Frederick E. Grine; John G. Fleagle; Richard E. Leakey | date = 1 Jun 2009 | publisher = Springer | page = 7 | chapter = Chapter 2: ''Homo habilis''—A Premature Discovery: Remember by One of Its Founding Fathers, 42 Years Later}}</ref> |

|||

===Subspecies=== |

|||

In 1961, [[Yves Coppens]] discovered a skull of ''Tchadanthropus uxoris'', then the earliest fossil human discovered in north Africa.<ref name=Kalb76>{{cite book | last = Kalb| first = Jon E| title =Adventures in the Bone Trade: The Race to Discover Human Ancestors in Ethiopia's Afar Depression| publisher =[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer]] | year = 2001 | page = 76| isbn =0-387-98742-8 |url=http://books.google.com/?id=SiWispLhG1UC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Adventures+Bone+Trade#v=onepage&q&f=false |accessdate=2010-12-02}}</ref> It was reported that the fossil "had been so eroded by wind-blown sand that it mimicked the appearance of an australopith, a primitive type of ''hominid''".<ref name=Wood2002>{{Cite journal |date=11 July 2002 |author=Wood, Bernard |title=Palaeoanthropology: Hominid revelations from Chad | journal=[[Nature (journal)|Nature]] |volume= 418 |issue= 6894 |pages= 133–135 |doi= 10.1038/418133a | url=http://www.fhuce.edu.uy/antrop/cursos/abiol/links/Artics/wood%202002.pdf | archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20110717090936/http://www.fhuce.edu.uy/antrop/cursos/abiol/links/Artics/wood%202002.pdf | archivedate=2011-07-17 |accessdate=2 December 2010}}</ref><!----------> Although at first considered to be a specimen of ''H. habilis'',<ref name=Cornevin>{{cite book | last = Cornevin| first = Robert| title =Histoire de l'Afrique | publisher =Payotte | year = 1967| page = 440 | isbn = 2-228-11470-7}}</ref> ''T. uxoris'' is no longer considered a valid taxon, and has been subsumed into ''H. erectus''.<ref name=Kalb76/><ref>{{cite web | title = Mikko's Phylogeny Archive | url = http://www.fmnh.helsinki.fi/users/haaramo/Metazoa/Deuterostoma/Chordata/Synapsida/Eutheria/Primates/Hominoidea/Homo_erectus.htm | archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20070106024346/http://www.fmnh.helsinki.fi/users/haaramo/Metazoa/Deuterostoma/Chordata/Synapsida/Eutheria/Primates/Hominoidea/Homo_erectus.htm | archivedate = 2007-01-06 | work=Finnish Museum of Natural History, University of Helsinki}}</ref> |

|||

"[[Wushan Man]]" was proposed as ''Homo erectus wushanensis'', but is now thought to be based upon fossilized fragments of an extinct non-hominin ape.<ref name="Ciochon">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ciochon RL | title = The mystery ape of Pleistocene Asia | journal = Nature | volume = 459 | issue = 7249 | pages = 910–911 | date = June 2009 | pmid = 19536242 | doi = 10.1038/459910a | s2cid = 205047272 | doi-access = free | bibcode = 2009Natur.459..910C }}</ref> |

|||

Since the discovery of [[Java Man]] in 1893, there has been a trend in paleoanthropology of reducing the number of proposed species of ''Homo'', to the point where ''H. erectus'' includes all early ([[Lower Paleolithic]]) forms of ''Homo'' sufficiently derived from ''[[Homo habilis|H. habilis]]'' and |

|||

In 2013, a fragment of fossilized jawbone, dated to around 2.8 million years ago, was discovered in the [[Ledi-Geraru]] research area in [[Afar Region|the Afar depression]], Ethiopia.<ref name=newscientist>{{cite web|url=http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn27079-oldest-known-member-of-human-family-found-in-ethiopia.html#.VPrw7vmsXId |title=Oldest known member of human family found in Ethiopia |publisher=''[[New Scientist]]'' |date=4 March 2015 |accessdate=2015-03-07}} |

|||

distinct from early ''[[Homo heidelbergensis|H. heidelbergensis]]'' (in Africa also known as ''[[Homo rhodesiensis|H. rhodesiensis]]'').<ref name=Kaifu2005/> It is sometimes considered as a wide-ranging, polymorphous species.<ref>{{Cite journal | doi=10.1038/nature.2013.13972| title=Skull suggests three early human species were one| year=2013| vauthors = Perkins S | journal=Nature| s2cid=88314849}}</ref> |

|||

{{cite web|last=Ghosh |first=Pallab |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-31718336 |title= 'First human' discovered in Ethiopia |publisher=bbc.co.uk |date=4 March 2015 |accessdate=7 March 2015}}</ref> The fossil is considered the earliest evidence of the ''Homo'' genus known to date, and seems to be intermediate between ''Australopithecus'' and ''H. habilis''. The individual lived just after a major [[Abrupt climate change|climate shift]] in the region, when forests and waterways were rapidly replaced by arid [[savannah]], which was a domain favored by the early hominins.<ref>"Vertebrate fossils record a faunal turnover indicative of more open and probable arid habitats than those reconstructed earlier in this region, in broad agreement with hypotheses addressing the role of environmental forcing in hominin evolution at this time." {{cite journal|url=http://www.sciencemag.org/content/early/2015/03/03/science.aaa1415 |title=Late Pliocene fossiliferous sedimentary record and the environmental context of early ''Homo'' from Afar, Ethiopia |author=Erin N. DiMaggio EN, Campisano CJ, Rowan J, Dupont-Nivet G, Deino AL|journal=[[Science (journal)|Science]] |doi=10.1126/science.aaa1415 |display-authors=etal}}</ref> |

|||

Due to such a wide range of variation, it has been suggested that the ancient ''[[Homo rudolfensis|H. rudolfensis]]'' and ''[[Homo habilis|H. habilis]]'' should be considered early varieties of ''H. erectus''.<ref name=dmanisiskull5>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lordkipanidze D, Ponce de León MS, Margvelashvili A, Rak Y, Rightmire GP, Vekua A, Zollikofer CP | title = A complete skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the evolutionary biology of early Homo | journal = Science | volume = 342 | issue = 6156 | pages = 326–331 | date = October 2013 | pmid = 24136960 | doi = 10.1126/science.1238484 | s2cid = 20435482 | bibcode = 2013Sci...342..326L }}</ref><ref name=National_Geographic>{{cite news | vauthors = Black R |date=17 October 2013 |title= Beautiful Skull Spurs Debate on Human History |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/131017-skull-human-origins-dmanisi-georgia-erectus/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210606185745/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/131017-skull-human-origins-dmanisi-georgia-erectus |url-status=dead |archive-date=6 June 2021 |work=[[National Geographic (magazine)|National Geographic]] |access-date=6 June 2021}}</ref> The primitive ''H. e. georgicus'' from [[Dmanisi skulls|Dmanisi]], Georgia has the smallest brain capacity of any known Pleistocene hominin (about 600 cc), and its inclusion in the species would greatly expand the range of variation of ''H. erectus'' to perhaps include species as ''H. rudolfensis'', ''[[Homo gautengensis|H. gautengensis]]'', ''[[Homo ergaster|H. ergaster]]'', and perhaps ''H. habilis''.<ref>{{cite news |title= Skull of Homo erectus throws story of human evolution into disarray |url= https://www.theguardian.com/science/2013/oct/17/skull-homo-erectus-human-evolution | vauthors = Sample I |work= The Guardian |date= 17 October 2013 }}</ref> However, a 2015 study suggested that ''H. georgicus'' represents an earlier, more primitive species of ''Homo'' derived from an older dispersal of hominins from Africa, with ''H. ergaster/erectus'' possibly deriving from a later dispersal.<ref name="Guimares">{{cite journal |vauthors=Giumares SW, Merino CL |title=Dmanisi hominin fossils and the problem of multiple species in the early Homo genus |journal=Nexus: The Canadian Student Journal of Anthropology |volume=23 |date=September 2015 |s2cid=73528018 |url=https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0f43/cf9c1c394c7af01cf10160f164cdec6dd77b.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200114162011/https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0f43/cf9c1c394c7af01cf10160f164cdec6dd77b.pdf |archive-date=2020-01-14 }}</ref> ''H. georgicus'' is sometimes not even regarded as ''H. erectus''.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Argue D, Groves CP, Lee MS, Jungers WL | title = The affinities of Homo floresiensis based on phylogenetic analyses of cranial, dental, and postcranial characters | journal = Journal of Human Evolution | volume = 107 | pages = 107–133 | date = June 2017 | pmid = 28438318 | doi = 10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.02.006 | bibcode = 2017JHumE.107..107A }}</ref><ref>{{Cite encyclopedia| vauthors = Lordkipanidze D |title=<SCP>D</SCP> manisi |chapter=Dmanisi|date=2018-10-04|encyclopedia=The International Encyclopedia of Biological Anthropology|pages=1–4| veditors = Trevathan W, Cartmill M, Dufour D, Larsen C |publisher=John Wiley & Sons, Inc.|language=en|doi=10.1002/9781118584538.ieba0139|isbn=9781118584422|s2cid=240090147}}</ref> |

|||

===''Homo erectus georgicus''=== |

|||

[[File:Dmanissi, Georgia ; Homo georgicus 1999 discovery map.png|thumb|Location of [[Dmanisi]] discovery, Georgia]] |

|||

It is debated whether the African ''H. e. ergaster'' is a separate species (and that ''H. erectus'' evolved in Asia, then migrated to Africa),<ref name="Baab">{{cite book |vauthors=Baab K |chapter=Defining Homo erectus |title=Handbook of Paleoanthropology |edition=2 |pages=2189–2219 |chapter-url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283477977 |date=December 2015 |doi=10.1007/978-3-642-39979-4_73 |isbn=978-3-642-39978-7 }}</ref> or is the African form (''[[sensu lato]]'') of ''H. erectus ([[sensu stricto]])''. In the latter, ''H. ergaster'' has also been suggested to represent the immediate ancestor of ''H. erectus''.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Tattersall I, Schwartz J |title=Extinct Humans|year=2001|isbn=978-0-8133-3482-0|place=Boulder, Colorado |publisher=Westview/Perseus |url=https://archive.org/details/extincthumans00tatt}}{{page needed|date=December 2019}}</ref> It has also been suggested that ''H. ergaster'' instead of ''H. erectus'', or some hybrid between the two, was the immediate ancestor of other archaic humans and modern humans.{{citation needed|date=April 2020}} It has been proposed that Asian ''H. erectus'' have several unique characteristics from non-Asian populations ([[autapomorphies]]), but there is no clear consensus on what these characteristics are or if they are indeed limited to only Asia. Based on supposed derived characteristics, the 120 kya Javan ''H. e. soloensis'' has been proposed to have speciated from ''H. erectus'', as ''H. soloensis'', but this has been challenged because most of the basic cranial features are maintained.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Kaifu Y, Aziz F, Indriati E, Jacob T, Kurniawan I, Baba H | title = Cranial morphology of Javanese Homo erectus: new evidence for continuous evolution, specialization, and terminal extinction | journal = Journal of Human Evolution | volume = 55 | issue = 4 | pages = 551–580 | date = October 2008 | pmid = 18635247 | doi = 10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.05.002 | bibcode = 2008JHumE..55..551K }}</ref> In a wider sense, ''H. erectus'' had mostly been replaced by ''H. heidelbergensis'' by about 300 kya, with possible late survival of ''[[Homo erectus soloensis|H. erectus soloensis]]'' in Java an estimated 117-108 kya.<ref name="Rizal" /> |

|||

'''''Homo erectus georgicus''''' is the subspecies name assigned to fossil skulls and jaws found in [[Dmanisi]], [[Georgia (country)|Georgia]]. First proposed as a separate species, it is now classified within ''H. erectus''.<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1126/science.1072953 |pmid=12098694 |year=2002 |author=Vekua A, Lordkipanidze D, Rightmire GP, Agusti J, Ferring R, Maisuradze G, Mouskhelishvili A, Nioradze M, De Leon MP, Tappen M, Tvalchrelidze M, Zollikofer C|title=A new skull of early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia |volume=297 |issue=5578 |pages=85–9 |journal=Science}}</ref><ref name=nature06134>{{Cite journal | author=Lordkipanidze D, Jashashvili T, Vekua A, Ponce de León MS, Zollikofer CP, Rightmire GP, Pontzer H, Ferring R, Oms O, Tappen M, Bukhsianidze M, Agusti J, Kahlke R, Kiladze G, Martinez-Navarro B, Mouskhelishvili A, Nioradze M, Rook L| title = Postcranial evidence from early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia | doi = 10.1038/nature06134 | journal = Nature |url=http://www.mediadesk.uzh.ch/assets/downloads/Dmanisi_press_release.pdf| volume = 449 | issue = 7160 | pages = 305–310 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17882214| pmc = }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |

|||

| last1 = Lordkipanidze | first1 = D. |

|||

| last2 = Vekua | first2 = A. |

|||

| last3 = Ferring | first3 = R. |

|||

| last4 = Rightmire | first4 = G. P. |

|||

| last5 = Agusti | first5 = J. |

|||

| last6 = Kiladze | first6 = G. |

|||

| last7 = Mouskhelishvili | first7 = A. |

|||

| last8 = Nioradze | first8 = M. |

|||

| last9 = Ponce De León | first9 = M. S. P. |

|||

| last10 = Tappen | first10 = M. |

|||

| last11 = Zollikofer | first11 = C. P. E. |

|||

| doi = 10.1038/434717b |

|||

| title = Anthropology: The earliest toothless hominin skull |

|||

| journal = Nature |

|||

| volume = 434 |

|||

| issue = 7034 |

|||

| pages = 717–718 |

|||

| year = 2005 |

|||

| pmid = 15815618 |

|||

| pmc = |

|||

}}</ref><!---------------> The site was discovered in 1991 by Georgian scientist [[David Lordkipanidze]]. Five skulls were excavated from 1991 forward, including a "very complete" skull in 2005. Excavations at Dmanisi have yielded 73 stone tools for cutting and chopping and 34 bone fragments from unidentified [[fauna]].<ref name="doi10.1073/pnas.1106638108"/> The fossils are about 1.8 million years old. |

|||

* ''[[Bilzingsleben (Paleolithic site)|H. e. bilzingslebenensis]]'' (Vlček 1978): Originally described from a series of skulls from Bilzingsleben, with the individual of [[Samu (fossil)|Vertesszöllös]] being referred.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Vlček |first=Emanuel |date=1978-03-01 |title=A new discovery of Homo erectus in central Europe |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047248478801158 |journal=Journal of Human Evolution |language=en |volume=7 |issue=3 |pages=239–251 |doi=10.1016/S0047-2484(78)80115-8 |bibcode=1978JHumE...7..239V |issn=0047-2484}}</ref> The material historically referred to this taxon are now affiliated with [[Neanderthal]]s and the hominins at [[Sima de los huesos|Sima de los Huesos]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Arsuaga |first1=Juan-Luis |last2=Martínez |first2=Ignacio |last3=Gracia |first3=Ana |last4=Carretero |first4=José-Miguel |last5=Carbonell |first5=Eudald |date=1993 |title=Three new human skulls from the Sima de los Huesos Middle Pleistocene site in Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/362534a0 |journal=Nature |language=en |volume=362 |issue=6420 |pages=534–537 |doi=10.1038/362534a0 |pmid=8464493 |bibcode=1993Natur.362..534A |s2cid=4321154 |issn=1476-4687}}</ref> |

|||

After their initial assessment, some scientists were persuaded to name the Dmanisi find as a new species, ''Homo georgicus'', which they posited as a descendant of African ''[[Homo habilis]]'' and an ancestor to Asian ''Homo erectus''. This classification, however, was not supported, and the fossil was instead designated a divergent subgroup of ''Homo erectus''.<!--------------><ref>{{cite journal|url=ftp://ftp.soest.hawaii.edu/engels/Stanley/Textbook_update/Science_300/Gibbons-03b.pdf |title=A Shrunken Head for African ''Homo erectus'' |doi=10.1126/science.300.5621.893a|year=2003|last1=Gibbons|first1=A.|journal=Science|volume=300|issue=5621|pages=893a }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Tattersall | first1 = I. | last2 = Schwartz | first2 = J. H. | doi = 10.1146/annurev.earth.031208.100202 | title = Evolution of the GenusHomo | journal = Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences | volume = 37 | pages = 67 | year = 2009 | pmid = | pmc = }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |

|||

* ''[[Boskop Man|H. e. capensis]]'' (Broom 1917): A variant of "''[[Boskop Man|Homo capensis]]''",<ref name=":12"/> a taxon erected from a skull from South Africa formally classified as a type of "[[Race (human categorization)|race]]" but is now considered a representative of the [[Khoisan]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Singer |first=Ronald |date=1958 |title=232. The Boskop 'Race' Problem |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2795854 |journal=Man |volume=58 |pages=173–178 |doi=10.2307/2795854 |jstor=2795854 |issn=0025-1496}}</ref> |

|||

| last1 = Rightmire | first1 = G. P. |

|||

* ''[[Lantian Man|H. e. chenchiawoensis]]'': A name utilized in a 2007 review of Chinese archeology; the text suggests that it and ''gongwanglingensis'' are contenders in taxonomy<ref name=":03">{{Cite book |last=李学勤 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KtB7iumTYcsC |title=20世纪中国学术大典: 考古学, 博物馆学 |date=2007 |publisher=福建教育出版社 |isbn=978-7-5334-3641-4 |language=zh}}</ref> (despite this name not appearing in the literature). |

|||

| last2 = Lordkipanidze | first2 = D. |

|||

* ''[[Java Man|H. e. erectus]]'' (Dubois 1891):<ref>{{Cite journal |last=E |first=Dubois |date=1891 |title=Palaeontologische onderzoekingen op Java |url=https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1573387448916597760 |journal=Verslag van het Mijnwezen, 3e/4e Kwartaal |pages=12–15}}</ref> The Javanese specimens of ''H. erectus'' were once classified as a distinct subspecies in the 1970s. The [[Java Man|cranium]] from [[Trinil]] is the holotype.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Tuttle |first=Russell H. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ejsyIZMsC9oC&pg=PA327 |title=Paleoanthropology: Morphology and Paleoecology |date=2011-05-12 |publisher=Walter de Gruyter |isbn=978-3-11-081069-1 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

| last3 = Vekua | first3 = A. |

|||

* ''[[Homo ergaster|H. e. ergaster]]'' (Groves and Mazák 1975): Antón and Middleton (2023) suggested that ''ergaster'' should be disused based on poor diagnoses.<ref name=":22">{{Cite journal |last1=Antón |first1=Susan C. |last2=Middleton |first2=Emily R. |date=2023-06-01 |title=Making meaning from fragmentary fossils: Early Homo in the Early to early Middle Pleistocene |journal=Journal of Human Evolution |language=en |volume=179 |pages=103307 |doi=10.1016/j.jhevol.2022.103307 |issn=0047-2484|doi-access=free |pmid=37030994 |bibcode=2023JHumE.17903307A }}</ref> The name ''Homo erectus ergaster georgicus'' was created to classify the [[Dmanisi]] population as a subspecies of ''H. e. ergaster'', but [[Binomial nomenclature|quadrinomials]] are not supported by the [[ICZN]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Schwartz |first1=Jeffrey H. |last2=Tattersall |first2=Ian |last3=Chi |first3=Zhang |date=2014-04-25 |title=Comment on "A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Evolutionary Biology of Early Homo " |url=https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1250056 |journal=Science |language=en |volume=344 |issue=6182 |pages=360 |doi=10.1126/science.1250056 |pmid=24763572 |bibcode=2014Sci...344..360S |s2cid=36578190 |issn=0036-8075}}</ref> |

|||

| doi = 10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.07.009 |

|||

* ''[[Dmanisi hominins|H. e. georgicus]]'' (Gabounia 1991):<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Gabounia |first1=Léo |last2=de Lumley |first2=Marie-Antoinette |last3=Vekua |first3=Abesalom |last4=Lordkipanidze |first4=David |last5=de Lumley |first5=Henry |date=2002-09-01 |title=Découverte d'un nouvel hominidé à Dmanissi (Transcaucasie, Géorgie) |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1631068302000325 |journal=Comptes Rendus Palevol |language=fr |volume=1 |issue=4 |pages=243–253 |doi=10.1016/S1631-0683(02)00032-5 |bibcode=2002CRPal...1..243G |issn=1631-0683}}</ref> This hypothetical subspecific designation unites the D2600 cranium with the remainder of the Dmanisi sample, a connection that was, at the time, controversial and was only suggested if the single-species hypothesis could be proven true.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Rightmire |first1=G. Philip |last2=Lordkipanidze |first2=David |last3=Vekua |first3=Abesalom |date=2006-02-01 |title=Anatomical descriptions, comparative studies and evolutionary significance of the hominin skulls from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047248405001624 |journal=Journal of Human Evolution |language=en |volume=50 |issue=2 |pages=115–141 |doi=10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.07.009 |pmid=16271745 |bibcode=2006JHumE..50..115R |issn=0047-2484}}</ref> |

|||

| title = Anatomical descriptions, comparative studies and evolutionary significance of the hominin skulls from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia |

|||

* ''[[Lantian Man|H. e. gongwanglingensis]]'': A name utilized in a 2007 review of Chinese archeology; the text suggests that it and ''chenchiawoensis'' are contenders in taxonomy.<ref name=":03" /> Rukang (1992) notes that this taxon was born in a "subspecies fever".<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Rukang |first=Wu |date=1992-06-15 |title=On the classification of subspecies of Homo |url=http://www.anthropol.ac.cn/EN/ |journal=Acta Anthropologica Sinica |language=en |volume=11 |issue=2 |pages=109 |issn=1000-3193}}</ref> |

|||

| journal = Journal of Human Evolution |

|||

* ''[[Homo habilis|H. e. habilis]]'' (Leakey, Tobias, and Napier 1964): D.R. Hughes believed that the [[Olduvai Gorge|Olduvai]] specimens were not distinct enough to be assigned to ''[[Australopithecus]]'', so he created this taxon, as an early variation of ''H. erectus''.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Tobias |first=Phillip V. |date=1991 |title=The species Homo habilis: example of a premature discovery |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/23735461 |journal=Annales Zoologici Fennici |volume=28 |issue=3/4 |pages=371–380 |jstor=23735461 |issn=0003-455X}}</ref> |

|||

| volume = 50 |

|||

* ''[[Homo heidelbergensis|H. e. heidelbergensis]]'' (Schoetensack 1908): This taxon was used as an alternative to standard ''H. heidelbergensis'' during the middle 20th century, interpreted as a European chronospecies of the wider Middle Pleistocene hominin morph.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Mounier |first1=A. |last2=Caparros |first2=M. |date=2015-10-01 |title=Le statut phylogénétique d'Homo heidelbergensis – étude cladistique des homininés du Pléistocène moyen |url=https://doi.org/10.1007/s13219-015-0127-4 |journal=BMSAP |language=fr |volume=27 |issue=3 |pages=110–134 |doi=10.1007/s13219-015-0127-4 |s2cid=17449909 |issn=1777-5469}}</ref> |

|||

| issue = 2 |

|||

* ''[[Hexian Man|H. e. hexianensis]]'' (Huang 1982): Established based on the Hexian cranium.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=W |first=Huang |date=1982 |title=Preliminary study on the fossil hominid skull and fauna of Hexian, Anhui |url=https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1572543025128829184 |journal=Vertebrata PalAsiatica |volume=20 |pages=plate 1}}</ref> |

|||

| pages = 115–141 |

|||

* ''[[Samu (fossil)|H. e. hungaricus]]'' (Naddeo 2023): A Hungarian paper submitted to a [[Academic conference|conference]] lists this subspecies as an alternate name for the Vertesszöllös remains.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Naddeo |first=Michelangelo |date=2023 |title=Az ősi magyar jelképrendszer keresése |url=https://epa.oszk.hu/01400/01445/00066/pdf/EPA01445_acta_hungarica_2023_1_0460-0492.pdf |journal=Acta Historica Hungaricus |volume=38}}</ref> |

|||

| year = 2006 |

|||

* ''[[Lantian Man|H. e. lantianensis]]'' (Ju-Kang 1964): Based on hominin fossils discovered in [[Lantian County|Lantian]], originally named as a species of ''[[Sinanthropus]]'' and then reclassified as a subspecies.<ref name="Woo1964b">{{cite journal |last=Woo |first=J.-K. |year=1964 |title=The Hominid Skull of Lantian, Shenshi |url=http://www.ivpp.cas.cn/cbw/gjzdwxb/xbwzxz/200912/P020091214552793457098.pdf |journal=Vertebrata PalAsiatica |volume=10 |issue=1}}</ref> |

|||

| pmid = 16271745 |

|||

* ''[[Olduvai Hominid 9|H. e. leakeyi]]'' (Heberer 1963): A conditional name and thus unavailable for [[Taxonomy|taxonomic]] use, once used to describe [[Olduvai Hominid 9|OH 9]]. The replacement name is ''louisleakeyi''.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Groves |first=Colin P. |date=1999-12-01 |title=Nomenclature of African Plio-Pleistocene hominins |url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047248499903664 |journal=Journal of Human Evolution |language=en |volume=37 |issue=6 |pages=869–872 |doi=10.1006/jhev.1999.0366 |issn=0047-2484 |pmid=10600324|bibcode=1999JHumE..37..869G }}</ref> It received limited use as a subspecies.<ref name=":12">{{Cite journal |last=Coon |first=Carleton S. |date=1966 |title=Review of The Nomenclature of the Hominidae, including a Definitive List of Hominid Taxa |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/41449277 |journal=Human Biology |volume=38 |issue=3 |pages=344–347 |jstor=41449277 |issn=0018-7143}}</ref> |

|||

| pmc = |

|||

* ''[[Maba Man|H. e. mapaensis]]'' (Kurth 1965): A name that was proposed for the [[Maba Man|Maba cranium]], although the use of the word 'perhaps' was interpreted by the [[Paleo Core]] database to be a conditional proposal and thus not available for valid reuse under the ICZN. Groves (1989) classified it as a subspecies of ''[[Homo sapiens]]'', and Howell (1999) did not assign the species to a genus.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2023 |title=Homo erectus mapaensis Kurth, 1965 |url=https://paleocore.org/origins/nomina/detail/218/ |access-date=2023-08-07 |website=Paleo Core |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |

|||

* ''[[Tighennif|H. e. mauritanicus]]'' (Arambourg 1954): A subspecies that received limited use as a descriptor for the cranial and mandibular material discovered at [[Tighennif|Tighenif]].<ref name=":12" /> |

|||

| doi = 10.1126/science.288.5468.1019 |

|||

* ''[[Narmada Human|H. e. narmadensis]]'' (Sonakia 1984): The name given to the [[Narmada cranium]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Sonakia |first1=Arun |last2=Kennedy |first2=Kenneth A. R. |date=1985 |title=Skull Cap of an Early Man from the Narmada Valley Alluvium (Pleistocene) of Central India |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/678879 |journal=American Anthropologist |volume=87 |issue=3 |pages=612–616 |doi=10.1525/aa.1985.87.3.02a00060 |jstor=678879 |issn=0002-7294}}</ref> |

|||

| last1 = Gabunia | first1 = L. |

|||

* ''[[Sambungmacan crania|H. e. newyorkensis]]'' (Laitman and Tattersall 2001): A name based on the Sambungmacan 3 cranium.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Laitman |first1=Jeffrey T. |last2=Tattersall |first2=Ian |date=2001-04-01 |title=Homo erectus newyorkensis: An Indonesian fossil rediscovered in Manhattan sheds light on the middle phase of human evolution |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ar.1042 |journal=The Anatomical Record |language=en |volume=262 |issue=4 |pages=341–343 |doi=10.1002/ar.1042 |pmid=11275967 |s2cid=35310160 |issn=0003-276X}}</ref> |

|||

| last2 = Vekua | first2 = A. |

|||

* [[Solo Man|''H. e. ngandongensis'']] (Sartono 1976): A name that was used in the process of splitting Pithecanthropus into many subspecies.<ref>{{Cite book |last=SARTONO R |url=https://pascal-francis.inist.fr/vibad/index.php?action=getRecordDetail&idt=12954719 |title=The Javanese Pleistocene Hominids: A Re-Appraisal |date=1976}}</ref> |

|||

| last3 = Lordkipanidze | first3 = D. |

|||

* ''[[Olduvai Hominid 9|H. e. olduvaiensis]]'': A subspecies that described the OH 9 cranium, compared to the Bilzingsleben cranial fragments.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Vlček |first1=Emanuel |last2=Mania |first2=Dietrich |date=1977 |title=Ein Neuer Fund Von Homo Erectus in Europa: Bilzingsleben (ddr) |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/26294532 |journal=Anthropologie (1962-) |volume=15 |issue=2/3 |pages=159–169 |jstor=26294532 |issn=0323-1119}}</ref> |

|||

| last4 = Swisher Cc | first4 = 3. |

|||

* ''[[Peking Man|H. e. pekinensis]]'' (Black and Zdansky 1927): Originally assigned the type of ''Sinanthropus'' based on a single molar.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=D |first=Black |date=1927 |title=On a lower molar hominid tooth from the Chou Kou Tien deposit |url=https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1571698599180803456 |journal=Palaeont. Sinica, Ser. D |volume=7 |pages=1–29}}</ref> Antón and Middleton (2023) suggested that [[Zhoukoudian Peking Man Site|Zhoukoudian]] and Nanjing may be referrable under this name if they exhibit enough discontinuity from ''H. erectus'' proper.<ref name=":22" /> |

|||

| last5 = Ferring | first5 = R. |

|||

* ''[[Reilingen cranium|H. e. reilingensis]]'' (Czarnetzki 1989): Referring to a single cranial fragment, this subspecies is now considered a member of the Neanderthal lineage.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Dean |first1=David |last2=Hublin |first2=Jean-Jacques |last3=Holloway |first3=Ralph |last4=Ziegler |first4=Reinhard |date=1998 |title=On the phylogenetic position of the pre-Neandertal specimen from Reilingen, Germany |journal=Journal of Human Evolution |language=en |volume=34 |issue=5 |pages=485–508 |doi=10.1006/jhev.1998.0214|doi-access=free |pmid=9614635 |bibcode=1998JHumE..34..485D }}</ref> |

|||

| last6 = Justus | first6 = A. |

|||

* ''[[Solo Man|H. e. soloensis]]'' (Oppenoorth 1932): The original name devised by Oppenoorth for the Ngandong crania.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Oppenoorth |first=W.F.F. |date=1932 |title=Homo (Javanthropus) soloensis. Ein plistocene mensch van Java |journal=Wetenschappelijke Mededeelingen |volume=20 |pages=49–75}}</ref> |

|||

| last7 = Nioradze | first7 = M. |

|||

* ''[[Tautavel Man|H. e. tautavelensis]]'' (de Lumley and de Lumley 1971): Referring to the remains discovered at [[Caune de l'Arago|Arago]], with many preferring allocation to ''Homo heidelbergensis''.<ref>{{Cite thesis |title=Reconstitution et position phylétique des restes crâniens de l'Homme de Tautavel (Arago 21-47) et de Biache-Saint-Vaast 2. Apports de l'imagerie et de l'analyse tridimensionnelle. |url=https://theses.hal.science/tel-00653112 |publisher=Université Paul Cézanne - Aix-Marseille III |date=2005-11-30 |degree=phdthesis |language=fr |first=Gaspard |last=Guipert}}</ref> The remains were determined not to be ''H. erectus'' by Antón and Middleton (2023).<ref name=":22" /> |

|||

| last8 = Tvalchrelidze | first8 = M. |

|||

* ''[[Java Man|H. e. trinilensis]]'' (Sartono 1976): A tentative classification scheme, thus making the name conditional and unable for use.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Sartono |first=S. |date=1980 |title=On the Javanese Pleistocene hominids: A reappraisal |journal=Abstracts of the IUSPP Nice}}</ref> |

|||

| last9 = Antón | first9 = S. C. |

|||

* ''[[Wajak crania|H. e. wadjakensis]]'' (Dubois 1921): A species established by Eugene Dubois based on the Wajak skulls.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Dubois |first=E. |date=1921-01-01 |title=The proto-Australian fossil man of Wadjak, Java |url=https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1921KNAB...23.1013D |journal=Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen Proceedings Series B Physical Sciences |volume=23 |pages=1013–1051|bibcode=1921KNAB...23.1013D }}</ref> Pramujiono classified these materials as a subspecies, and incorrectly self-published the name as ''wajakensis''.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Pramujiono |first=Agung |title=BERBAGAI PANDANGAN ASAL BANGSA DAN BAHASA INDONESIA: DARI KAJIAN LINGUSITIK HISTORIS KOMPARATIF SAMPAI ARKEOLINGUISTIK DAN PALEOLINGUISTIK |url=https://www.academia.edu/9091394 |website=Academia.edu}}</ref> |

|||

| last10 = Bosinski | first10 = G. |

|||

* ''[[Wushan Man|H. e. wushanensis]]'' (Huang and Fang 1991): Originally conceived as a hominin, the remains this taxon is founded on are more likely referred to [[Ponginae]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Wei |first1=Guangbiao |last2=Huang |first2=Wanbo |last3=Chen |first3=Shaokun |last4=He |first4=Cunding |last5=Pang |first5=Libo |last6=Wu |first6=Yan |date=2014-12-15 |title=Paleolithic culture of Longgupo and its creators |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1040618214002110 |journal=Quaternary International |series=Multidisciplinary Perspectives on the Gigantopithecus Fauna and Quaternary Biostratigraphy in East Asia |language=en |volume=354 |pages=154–161 |doi=10.1016/j.quaint.2014.04.003 |bibcode=2014QuInt.354..154W |issn=1040-6182}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Zanolli |first1=Clément |last2=Kullmer |first2=Ottmar |last3=Kelley |first3=Jay |last4=Bacon |first4=Anne-Marie |last5=Demeter |first5=Fabrice |last6=Dumoncel |first6=Jean |last7=Fiorenza |first7=Luca |last8=Grine |first8=Frederick E. |last9=Hublin |first9=Jean-Jacques |last10=Nguyen |first10=Anh Tuan |last11=Nguyen |first11=Thi Mai Huong |last12=Pan |first12=Lei |last13=Schillinger |first13=Burkhard |last14=Schrenk |first14=Friedemann |last15=Skinner |first15=Matthew M. |date=May 2019 |title=Evidence for increased hominid diversity in the Early to Middle Pleistocene of Indonesia |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-019-0860-z |journal=Nature Ecology & Evolution |language=en |volume=3 |issue=5 |pages=755–764 |doi=10.1038/s41559-019-0860-z |pmid=30962558 |bibcode=2019NatEE...3..755Z |s2cid=102353734 |issn=2397-334X}}</ref> |

|||

| last11 = Jöris | first11 = O. |

|||

* ''[[Yuanmou Man|H. e. yuanmouensis]]'' (Li ''et al.'' 1977): Based on hominin remains<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Chengzhi |first=Hu |date=1973 |title=Yunnan Yuanmou faxian de yuanren yachi huashi |journal=Dizhi Xuebao |volume=1 |pages=65–71}}</ref> that Antón and Middleton (2023) suggest do not belong to the taxon H. erectus, although they do not provide an alternate classification.<ref name=":22" /> |

|||

| last12 = Lumley | first12 = M. A. |

|||

| last13 = Majsuradze | first13 = G. |

|||

| last14 = Mouskhelishvili | first14 = A. |

|||

| title = Earliest Pleistocene hominid cranial remains from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia: Taxonomy, geological setting, and age |

|||

| journal = Science |

|||

| volume = 288 |

|||

| issue = 5468 |

|||

| pages = 1019–1025 |

|||

| year = 2000 |

|||

| pmid = 10807567 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Homo Georgicus IMG 2921.JPG|thumb|upright|Modern reproduction of the [[Dmanisi skull 3]] (fossils skull D2700 and jaw D2735, two of several found in [[Dmanisi]] in the [[Georgia (country)|Georgian]] [[Transcaucasus]])]] |

|||

The fossil skeletons present a species primitive in its skull and upper body but with relatively advanced spine and lower limbs, inferring greater mobility than the previous morphology.<ref name="Bower, Bruce 275–276">{{cite journal|doi=10.2307/4019325|title=Evolutionary back story: Thoroughly modern spine supported human ancestor|author=Bower, Bruce|journal=Science News|volume =169|issue =18| pages =275–276|date= 3 May 2006 }}</ref> <!----->It is now thought ''not'' to be a separate species, but to represent a stage soon after the transition between ''H. habilis'' to ''H. erectus''; it has been dated at 1.8 mya.<ref name=nature06134/><ref>{{cite news |first=John Noble |last=Wilford |authorlink=John Noble Wilford |date=19 September 2007 |title=New Fossils Offer Glimpse of Human Ancestors |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/19/science/19cnd-fossil.html |work=[[The New York Times]] |accessdate=9 September 2009}}</ref> The assemblage includes one of the largest [[Pleistocene]] ''Homo'' mandibles (D2600), one of the smallest [[Lower Pleistocene]] mandibles (D211), a nearly complete sub-adult (D2735), and a toothless specimen [[Dmanisi skull 4|D3444/D3900]].<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.02.003 |pmid=18394678 |year=2008 |last1=Rightmire |first1=G. Philip |last2=Van Arsdale |first2=Adam P. |last3=Lordkipanidze |first3=David |authorlink3=David Lordkipanidze |title=Variation in the mandibles from Dmanisi, Georgia |volume=54 |issue=6 |pages=904–8 |journal=Journal of Human Evolution}}</ref> |

|||

===Descendants and synonyms=== |

|||

Two of the skulls—[[skull D2700|D2700]], with a brain volume of {{Convert|600|cc}}, and [[Dmanisi skull|D4500 or Dmanisi Skull 5]], with a brain volume of about 546 centimetres—present the two smallest and most primitive [[Hominina]] skulls from the Pleistocene period.<ref name=dmanisiskull5>{{cite journal |title=A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Evolutionary Biology of Early Homo |author=David Lordkipanidze1, Marcia S. Ponce de Lean, Ann Margvelashvili, Yoel Rak, G. Philip Rightmire, Abesalom Vekua, Christoph P. E. Zollikofer |journal=Science |date=18 October 2013 |volume= 342 |issue= 6156 |pages= 326–331 |doi= 10.1126/science.1238484 }}</ref> <!------------>The variation in these skulls were compared to variations in modern humans and within a sample group of chimpanzees. The researchers found that, despite appearances, the variations in the Dmanisi skulls were no greater than those seen among modern people and among chimpanzees. These findings suggest that previous fossil finds that were classified as different species on the basis of the large morphological variation among them—including ''[[Homo rudolfensis]]'', ''[[Homo gautengensis]]'', ''[[H. ergaster]]'', and potentially even ''[[H. habilis]]''—should perhaps be re-classified to the same lineage as ''Homo erectus''.<ref>{{cite news |title= Skull of Homo erectus throws story of human evolution into disarray |url= http://www.theguardian.com/science/2013/oct/17/skull-homo-erectus-human-evolution |author=Ian Sample |work= The Guardian |date= 17 October 2013 }}</ref> |

|||