Skara Brae: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Fixing reference errors |

||

| (501 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Neolithic archaeological site in Scotland}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=October 2015}} |

|||

{{about| |

{{about|Neolithic settlement in Orkney, Scotland}} |

||

{{Use British English|date=March 2019}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=May 2021}} |

|||

{{Infobox ancient site |

{{Infobox ancient site |

||

| name = Skara Brae |

|||

| native bvgfjp_name = |

|||

|native_name = |

|||

| alternate_name = |

|||

| alt = |

|||

|image = Skara Brae 12.jpg |

|||

| caption = Skara Brae from the entrance gate |

|||

|alt = |

|||

| map = {{Infobox mapframe|id=Q816437|zoom=13|frame-width=250}} |

|||

|caption = Skara Brae, looking north |

|||

| map_type = Scotland Orkney |

|||

| map_alt = |

|||

| map_size = |

|||

|latitude= 59.048611 |

|||

| location = [[Mainland, Orkney]], [[Scotland]] |

|||

|longitude= -3.343056 |

|||

| coordinates = {{coord|59.0487138|-3.3417499|format=dms|region:GB_type:landmark|display=inline,title}} |

|||

|map_size = |

|||

| type = Neolithic settlement |

|||

|location = [[Mainland, Orkney]] |

|||

| part_of = |

|||

|region = Scotland |

|||

| length = |

|||

|coordinates = |

|||

| width = |

|||

|type = Neolithic settlement |

|||

| area = |

|||

| height = |

|||

| builder = |

|||

| material = |

|||

| built = 3180 BC; {{time interval|-3180}} ago |

|||

|height = |

|||

| abandoned = |

|||

|builder = |

|||

| epochs = [[Neolithic]] |

|||

|material = |

|||

| cultures = |

|||

| dependency_of = |

|||

|abandoned = |

|||

| occupants = |

|||

|epochs = [[Neolithic]] |

|||

| event = |

|||

|cultures = |

|||

| excavations = |

|||

|dependency_of = |

|||

| archaeologists = |

|||

|occupants = |

|||

| condition = |

|||

|event = |

|||

| ownership = [[Historic Environment Scotland]] |

|||

|excavations = |

|||

| public_access = Yes |

|||

|archaeologists = |

|||

| website = |

|||

|condition = |

|||

| notes = |

|||

|ownership = [[Historic Scotland]] |

|||

|public_access = Yes |

|||

|website = |

|||

|notes = |

|||

| designation1 = WHS |

| designation1 = WHS |

||

| designation1_partof = [[Heart of Neolithic Orkney]] |

| designation1_partof = [[Heart of Neolithic Orkney]] |

||

| Line 43: | Line 42: | ||

| designation1_type = Cultural |

| designation1_type = Cultural |

||

| designation1_criteria = i, ii, iii, iv |

| designation1_criteria = i, ii, iii, iv |

||

| designation1_number = [ |

| designation1_number = [https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/514 514] |

||

| designation1_free1name = |

| designation1_free1name = Region |

||

| designation1_free1value = |

| designation1_free1value = [[List of World Heritage Sites in Europe|Europe]] |

||

| hes = SM90276 |

|||

| designation1_free2name = Region |

|||

|image=File:2018 07 12 Schottland (94).jpg}} |

|||

| designation1_free2value = [[List of World Heritage Sites in Europe|Europe and North America]] |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Skara Brae''' {{IPAc-en|ˈ|s|k| |

'''Skara Brae''' {{IPAc-en|ˈ|s|k|ær|ə|_|ˈ|b|r|eɪ}} is a stone-built [[Neolithic]] settlement, located on the [[Bay of Skaill]] in the parish of [[Sandwick, Orkney|Sandwick]], on the west coast of [[Mainland, Orkney|Mainland]], the largest island in the [[Orkney]] archipelago of [[Scotland]]. It consisted of ten clustered houses, made of [[flagstone]]s, in earthen dams that provided support for the walls; the houses included stone [[hearth]]s, beds, and cupboards.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/neolithic-orkney |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210904152252/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/neolithic-orkney |archive-date=4 September 2021 |title=Before Stonehenge |date=1 August 2014 |work=National Geographic |access-date=30 March 2022 |quote=ten stone structures, The village had a drainage system and even indoor toilets.|url-access=subscription}}</ref> A primitive sewer system, with "toilets" and drains in each house,<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/skara-brae |title=Skara Brae Sandwick, Scotland |date=20 January 2018 |work=Atlas Obscura |access-date=13 February 2021 |quote=Amazing and mysterious Neolithic settlement on Scotland's Orkney Islands}}</ref><ref name=":0" /> included water used to flush waste into a drain and out to the ocean.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-22214728 |title=Scotland and the indoor toilet |date=19 October 2013 |work=BBC News |access-date=13 February 2021 |quote=According to Allan Burnett, historian and author of Invented In Scotland, the Neolithic settlement of Skara Brae in Orkney in fact boasted the world's first indoor toilet.}}</ref> |

||

The site was occupied from roughly 3180 BC to about 2500 BC and is Europe's most complete Neolithic village. Skara Brae gained [[UNESCO]] [[World Heritage Site]] status as one of four sites making up "The [[Heart of Neolithic Orkney]]".{{efn|It is one of four [[UNESCO]] [[World Heritage Site]]s in Scotland, the others being the [[Old Town, Edinburgh|Old Town]] and [[New Town, Edinburgh|New Town]] of [[Edinburgh]]; [[New Lanark]] in [[South Lanarkshire]]; and [[St Kilda, Scotland|St Kilda]] in the [[Outer Hebrides|Western Isles]]}} Older than [[Stonehenge]] and the [[Great Pyramids of Giza]], it has been called the "Scottish [[Pompeii]]" because of its excellent preservation.<ref>{{harvnb|Hawkes|1986|p=262}}</ref> |

|||

Care of the site is the responsibility of [[Historic Environment Scotland]] which works with partners in managing the site: [[Orkney Islands Council]], [[NatureScot]] (Scottish Natural Heritage), and the [[Royal Society for the Protection of Birds]].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/514/ |title=Heart of Neolithic Orkney |date=20 January 2018 |work=UNESCO |access-date=13 February 2021 |quote=A Management Plan has been prepared by Historic Scotland in consultation with the Partners who share responsibility}}</ref> Visitors to the site are welcome during much of the year. |

|||

Uncovered by a storm in 1850, the coastal site may now be at risk from climate change. |

|||

==Discovery and early exploration== |

==Discovery and early exploration== |

||

In the winter of 1850, a severe storm hit Scotland, causing widespread damage and over 200 deaths.<ref name=bryson2010>{{harvnb|Bryson|2010}}</ref> In the Bay of Skaill, the storm stripped |

In the winter of 1850, a severe storm hit Scotland, causing widespread damage and over 200 deaths.<ref name=bryson2010>{{harvnb|Bryson|2010}}</ref> In the [[Bay of Skaill]], the storm stripped earth from a large irregular [[Hillock|knoll]]. (The name Skara Brae is a corruption of Skerrabra or Styerrabrae, which originally referred to the knoll.<ref name=":0" />) When the storm cleared, local villagers found the outline of a village consisting of several small houses without roofs.<ref name=bryson2010/><ref name=OSB>{{cite web |url= http://www.orkneyjar.com/history/skarabrae/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121006160509/http://www.orkneyjar.com/history/skarabrae/ |archive-date=2012-10-06 |title=Skara Brae: The Discovery of the Village |website=Orkneyjar.com |access-date=29 September 2012}}</ref> William Graham Watt of [[Skaill House]],<ref>{{cite web |title=The House |url=https://skaillhouse.co.uk/the-house/ |website=skaillhouse.co.uk |access-date=1 September 2024}}</ref> a son of the local [[laird]] who was a self-taught [[geologist]], began an amateur excavation of the site, but after four houses were uncovered, work was abandoned in 1868.<ref name="aosb">{{cite web |last1=Long |first1=Patricia |title=A Skara Brae Whodunnit |url= https://www.aboutorkney.com/2020/06/17/a-skara-brae-whodunnit/ |website=About Orkney |date=17 June 2020 |access-date=25 June 2023}}</ref> |

||

The site remained undisturbed until 1913, when during a single weekend, the site was plundered by a party with shovels who took away an unknown quantity of artefacts.<ref name=bryson2010/> In 1924, another storm swept away part of one of the houses, and it was determined the site should be secured and properly investigated.<ref name=bryson2010/> The job was given to the [[University of Edinburgh]]'s Professor [[V. Gordon Childe]], who travelled to Skara Brae for the first time in mid-1927.<ref name=bryson2010/> |

|||

In 2019 a series of photographs showing Childe and four women at the site of the excavation were re-examined. It had been widely believed that the women were tourists or local women visiting the excavation site, but a note on the back of of the photographs identified the women as "4 of [Childe's] lady students", and it seems that they were active participants in the excavation.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Magazine |first=Smithsonian |last2=Katz |first2=Brigit |title=Internet Sleuths Were on the Case to Name the Women Archaeologists in These Excavation Photos |url= https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/internet-sleuths-help-uncover-names-female-archaeologists-20th-century-photographs-180971828/ |access-date=2024-08-21 |website=Smithsonian Magazine |language=en}}</ref> The women have been tentatively identified as [[Margaret E. B. Simpson]] (who was acknowledged in Childe's monographs about Skara Brae), Margaret Mitchell, Mary Kennedy and [[Margaret Cole]].<ref>{{Cite news |date=2019-03-21 |title= Skara Brae women archaeologists who were written out of history |url= https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-north-east-orkney-shetland-47639736 |access-date=2024-08-21 |language=en-GB}}</ref> |

|||

==Neolithic lifestyle== |

==Neolithic lifestyle== |

||

Skara Brae |

The inhabitants of Skara Brae were makers and users of [[grooved ware]], a distinctive style of [[pottery]] that had recently appeared in northern Scotland.<ref>{{harvnb|Darvill|1987|p=85}}</ref> The houses used [[earth sheltering]]: built sunk in the ground, into mounds of prehistoric domestic waste known as [[midden]]s. This provided the houses with stability and also acted as insulation against Orkney's harsh winter climate. On average, each house measures {{convert|40|m2|ft2}} with a large square room containing a stone [[hearth]] used for heating and cooking. Given the number of homes, it seems likely that no more than fifty people lived in Skara Brae at any given time.<ref>{{harvnb|Hedges|1984|p=107}}</ref> |

||

[[Image:Orkney Skara Brae.jpg|thumb|220px|right|Excavated dwellings at Skara Brae]] |

|||

It is |

It is not clear what material the inhabitants burned in their [[hearth]]s. Childe was sure that the fuel was [[peat]],<ref name="Childe 1931">{{harvnb|Childe|1931}}</ref> but a detailed analysis of vegetation patterns and trends suggests climatic conditions conducive to the development of thick beds of peat did not develop in this part of Orkney until after Skara Brae was abandoned.<ref>{{harvnb|Keatinge|Dickson|1979}}</ref> Other possible fuels include [[driftwood]] and [[Dry dung fuel|animal dung]]. There is evidence that dried [[seaweed]] may have been used significantly. At some sites in Orkney, investigators have found a glassy, slag-like material called "[[kelp]]" or "cramp" which may be residual burnt seaweed.<ref>{{harvnb|Fenton|1978|pp=206–209}}</ref> |

||

The dwellings contain several stone-built pieces of furniture, including [[cupboard]]s, [[Welsh dresser|dresser]]s, seats, and storage boxes. Each dwelling was entered through a low doorway with a stone slab door which could be shut "by a bar made of bone that slid in bar-holes cut in the stone door jambs."<ref>{{harvnb|Childe|Simpson|1952|p=21}}</ref> Several dwellings offered a small connected antechamber, offering access to a partially covered stone drain leading away from the village. It is suggested that these chambers served as indoor toilets.<ref name="Pre">{{cite journal |last1=Childe |first1=V. |last2=Paterson |first2=J. |last3=Thomas |first3=Bryce |title=Provisional Report on the Excavations at Skara Brae, and Finds from the 1927 and 1928 Campaigns. With a Report on Bones |journal=Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland |date=30 Nov 1929 |volume=63 |pages=225–280 |doi=10.9750/PSAS.063.225.280 |s2cid=182466398 |url=http://journals.socantscot.org/index.php/psas/article/view/7758/7726 |access-date=6 May 2020|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last1=Suddath |first1=Claire |title=A Brief History of Toilets |url=http://content.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1940525,00.html |access-date=6 May 2020 |agency=Time |publisher=Time |date=19 Nov 2009}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{cite encyclopedia |last1=Mark |first1=Joshua J. |title=Skara Brae |url=https://www.worldhistory.org/Skara_Brae/ |encyclopedia=[[World History Encyclopedia]] |access-date=6 May 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Grant, F.S.A.ScoT. |first1=Walter G. |last2=Childe, F.S.A.ScoT. |first2=V. G. |title=A STONE-AGE SETTLEMENT AT THE BRAES OF RINYO, ROUSAY, ORKNEY. (FIRST REPORT.)|journal=Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland |date=1938 |volume=72 |url=http://soas.is.ed.ac.uk/index.php/psas/article/download/8098/8066 |access-date=6 May 2020}}</ref> |

|||

The dwellings contain a number of stone-built pieces of furniture, including cupboards, dressers, seats, and storage boxes. Each dwelling was entered through a low doorway that had a stone slab door that could be closed "by a bar that slid in bar-holes cut in the stone door jambs".<ref>{{harvnb|Childe|Simpson|1952|p=21}}</ref> A sophisticated drainage system was incorporated into the village's design. It included a primitive form of toilet in each dwelling. |

|||

Seven of the houses have similar furniture, with the beds and |

Seven of the houses have similar furniture, with the beds and dressers in the same places in each house. The dresser stands against the wall opposite the door and is the first thing seen by anyone entering the dwelling. Each of these houses had a larger bed on the right side of the doorway and a smaller one on the left. [[Lloyd Laing (archaeologist)|Lloyd Laing]] noted that this pattern accorded with [[Hebridean]] custom up to the early 20th century suggesting that the husband's bed was the larger and the wife's was the smaller.<ref>{{harvnb|Laing|1974|p=61}}</ref> The discovery of beads and paint pots in some of the smaller beds may support this interpretation. Additional support may come from the recognition that stone boxes lie to the left of most doorways, forcing the person entering the house to turn to the right-hand, "male", side of the dwelling.<ref>{{harvnb|Ritchie|1995|p=32}}</ref> At the front of each bed lie the stumps of stone pillars that may have supported a canopy of fur; another link with recent Hebridean style.<ref>{{harvnb|Childe|Clarke|1983|p=9}}</ref> |

||

[[ |

[[File:Skara Brae house 1 5.jpg|thumb|right|Evidence of home furnishings]] |

||

House 8 has no storage boxes or dresser and has been divided into something resembling small cubicles. Fragments of stone, bone, and antler were excavated suggesting House 8 may have been used to make tools such as bone needles or [[flint axe]]s.<ref>{{harvnb|Beck|Black|Krieger|Naylor|1999}}</ref> The presence of heat-damaged volcanic rocks and what appears to be a [[flue]], supports this interpretation. House 8 is distinctive in other ways as well: it is a stand-alone structure not surrounded by midden;<ref>{{harvnb|Clarke|Sharples|1985|p=66}}</ref> instead it is above ground with walls over {{convert|2|m|ft}} thick and has a "porch" protecting the entrance. |

|||

The site provided the earliest known record of the |

The site provided the earliest known record of the [[human flea|human flea (''Pulex irritans'')]] in Europe.<ref>{{harvnb|Buckland|Sadler|2003}}</ref> |

||

The [[Grooved Ware People]] who built Skara Brae were primarily [[pastoralism|pastoralists]] who raised cattle and sheep.<ref name="Childe 1931"/> Childe originally believed that the inhabitants did not |

The [[Grooved ware|Grooved Ware People]] who built Skara Brae were primarily [[pastoralism|pastoralists]] who raised cattle, pig and sheep.<ref name="Childe 1931"/> Childe originally believed that the inhabitants did not farm, but excavations in 1972 unearthed seed grains from a midden suggesting that [[barley]] was cultivated.<ref>{{harvnb|Laing|1974|p=54}}</ref> Fish bones and shells are common in the midden indicating that dwellers ate seafood. Limpet shells are standard and may have been fish bait that was kept in stone boxes in the homes.<ref>{{harvnb|Childe|Clarke|1983|p=10}}</ref> The boxes were formed from thin slabs with joints carefully sealed with clay to render them waterproof. |

||

This pastoral lifestyle is in sharp contrast to some of the more exotic interpretations of the culture of the Skara Brae people. Euan MacKie suggested that Skara Brae might be the home of a privileged theocratic class of wise men who engaged in astronomical and magical ceremonies at nearby [[Ring of Brodgar]] and the [[Standing Stones of Stenness]].<ref>{{harvnb|MacKie|1977}}</ref> Graham and Anna Ritchie cast doubt on this interpretation noting |

This pastoral lifestyle is in sharp contrast to some of the more exotic interpretations of the culture of the Skara Brae people. Euan MacKie suggested that Skara Brae might be the home of a privileged theocratic class of wise men who engaged in astronomical and magical ceremonies at nearby [[Ring of Brodgar]] and the [[Standing Stones of Stenness]].<ref>{{harvnb|MacKie|1977}}</ref> Graham and Anna Ritchie cast doubt on this interpretation noting there is no archaeological evidence for this claim,<ref>{{harvnb|Ritchie|1981|pp=51–52}}</ref> although a Neolithic "low road" that goes from Skara Brae passes near both these sites and ends at the chambered tomb of [[Maeshowe]].<ref>{{harvnb|Castleden|1987|p=117}}</ref> Low roads connect Neolithic ceremonial sites throughout Britain. |

||

[[ |

[[File:Skara Brae house 7.jpg|thumb|right|View over the settlement, showing covering to house No. 7 and proximity to modern shore line. The glass roof has now been replaced by a turf one, as the humidity and heat caused by the glass roof were hindering preservation.]] |

||

==Dating and abandonment== |

==Dating and abandonment== |

||

Originally, Childe believed that the settlement dated from around 500 |

Originally, Childe believed that the settlement dated from around 500 BC.<ref name="Childe 1931"/> This interpretation was coming under increasing challenge by the time new excavations in 1972–73 settled the question. [[Carbon-14|Radiocarbon]] results obtained from samples collected during these excavations indicate that occupation of Skara Brae began about 3180 BC<ref name="Childe 1983 6">{{harvnb|Childe|Clarke|1983|p=6}}</ref> with occupation continuing for about six hundred years.<ref>{{harvnb|Castleden|1987|p=47}}</ref> Around 2500 BC, after the climate changed, becoming much colder and wetter, the settlement may have been abandoned by its inhabitants. There are many theories as to why the people of Skara Brae left; particularly popular interpretations involving a major storm. Evan Hadingham combined evidence from found objects with the storm scenario to imagine a dramatic end to the settlement: |

||

{{Quote|As was the case at Pompeii, the inhabitants seem to have been taken by surprise and fled in haste, for many of their prized possessions, such as necklaces made from animal teeth and bone, or pins of walrus ivory, were left behind. The remains of choice meat joints were discovered in some of the beds, presumably forming part of the villagers' last supper. One woman was in such haste that her necklace broke as she squeezed through the narrow doorway of her home, scattering a stream of beads along the passageway outside as she fled the encroaching sand.<ref>{{harvnb|Hadingham|1975|p=66}}</ref>}} |

{{Quote|As was the case at [[Pompeii]], the inhabitants seem to have been taken by surprise and fled in haste, for many of their prized possessions, such as necklaces made from animal teeth and bone, or pins of [[walrus ivory]], were left behind. The remains of choice meat joints were discovered in some of the beds, presumably forming part of the villagers' last supper. One woman was in such haste that her necklace broke as she squeezed through the narrow doorway of her home, scattering a stream of beads along the passageway outside as she fled the encroaching sand.<ref>{{harvnb|Hadingham|1975|p=66}}</ref>}} |

||

Anna Ritchie strongly disagrees with catastrophic interpretations of the village's abandonment: |

Anna Ritchie strongly disagrees with catastrophic interpretations of the village's abandonment: |

||

{{Quote|A popular myth would have the village abandoned during a massive storm that threatened to bury it in sand instantly, but the truth is that its burial was gradual and that it had already been abandoned – for what reason, no one can tell.<ref>{{harvnb|Ritchie|1995|p=29}}</ref>}} |

{{Quote|A popular myth would have the village abandoned during a massive storm that threatened to bury it in sand instantly, but the truth is that its burial was gradual and that it had already been abandoned – for what reason, no one can tell.<ref>{{harvnb|Ritchie|1995|p=29}}</ref>}} |

||

The site was farther from the sea than it is today, and it is possible that Skara Brae was built adjacent to a [[ |

The site was farther from the sea than it is today, and it is possible that Skara Brae was built adjacent to a [[fresh water]] lagoon protected by [[dune]]s.<ref name="Childe 1983 6"/> Although the visible buildings give an impression of an organic whole, certainly, an unknown quantity of additional structures had already been lost to sea erosion before the site's rediscovery and subsequent protection by a [[seawall]].<ref>{{harvnb|Clarke|Sharples|1985|p=58}}</ref> Uncovered remains are known to exist immediately adjacent to the ancient monument in areas presently covered by fields, and others, of uncertain date, can be seen eroding out of the cliff edge a little to the south of the enclosed area. |

||

== |

==Artefacts== |

||

[[ |

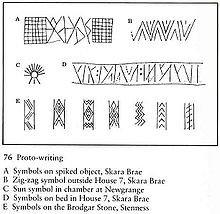

[[File:Skara Brae symbols1.jpg|thumb|right|Symbols found at Skara Brae and other Neolithic sites]] |

||

A number of enigmatic [[carved stone balls]] have been found at the site and some are on display in the museum.<ref name="Carved Balls">{{Cite web | url=http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=147 | title=Carved-Stone Balls at Skara Brae | access-date=2011-11-03}}</ref> Similar objects have been found throughout northern Scotland. The spiral ornamentation on some of these "balls" has been stylistically linked to objects found in the [[River Boyne|Boyne Valley]] in Ireland.<ref>{{harvnb|Laing|1982|p=137}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Piggott|1954|p=329}}</ref> Similar symbols have been found carved into stone lintels and bed posts.<ref name="Childe 1931"/> These symbols, sometimes referred to as "runic writings", have been subjected to controversial translations. For example, author Rodney Castleden suggested that "colons" found punctuating vertical and diagonal symbols may represent separations between words.<ref>{{harvnb|Castleden|1987|p=253}}</ref> |

|||

A number of enigmatic [[Carved Stone Balls]] have been found at the site and some are on display in the museum.<ref name="Carved Balls"> |

|||

{{Cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=147 |

|||

|title=Carved-Stone Balls at Skara Brae |

|||

|accessdate=2011-11-03 |

|||

}}</ref> Similar objects have been found throughout northern Scotland. The spiral ornamentation on some of these "balls" has been stylistically linked to objects found in the [[Boyne Valley]] in Ireland.<ref>{{harvnb|Laing|1982|p=137}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Piggott|1954|p=329}}</ref> Similar symbols have been found carved into stone lintels and bed posts.<ref name="Childe 1931"/> These symbols, sometimes referred to as "runic writings", have been subjected to controversial translations. For example, Castleden suggested that "colons" found punctuating vertical and diagonal symbols may represent separations between words.<ref>{{harvnb|Castleden|1987|p=253}}</ref> |

|||

Lumps of red [[ochre]] found here and at other [[Neolithic]] sites have been interpreted as evidence that [[body painting]] may have been |

Lumps of red [[ochre]] found here and at other [[Neolithic]] sites have been interpreted as evidence that [[body painting]] may have been practised.<ref>{{harvnb|Burl|1976|p=87}}</ref> |

||

Nodules of [[Hematite|haematite]] with polished surfaces have been found as well; the shiny surfaces suggest that the nodules were used to finish leather.<ref>{{harvnb|Ritchie|1995|p=18}}</ref> |

|||

Other artifacts excavated on site made of animal, fish, bird, and [[whalebone]], whale and [[walrus]] [[ivory]], and [[killer whale]] teeth included [[bradawl|awl]]s, needles, knives, [[bead]]s, [[adze]]s, [[shovel]]s, small bowls and, most remarkably, ivory pins up to {{convert|10|in|cm}} long.<ref>{{harvnb|Clarke|Sharples|1985|pp=78–81}}</ref> These pins are very similar to examples found in [[passage grave]]s in the [[Boyne Valley]], another piece of evidence suggesting a linkage between the two cultures.<ref>{{harvnb|Ritchie|1981|p=41}}</ref> So-called Skaill knives were commonly used tools in Skara Brae; these consist of large flakes knocked off sandstone cobbles.<ref>{{harvnb|Ritchie|1995|p=16}}</ref> Skaill knives have been found throughout Orkney and [[Shetland]]. |

|||

Other artefacts excavated on site made of animal, fish, bird, and [[whalebone]], whale and [[walrus ivory]], and [[orca]] teeth included [[bradawl|awl]]s, needles, knives, [[bead]]s, [[adze]]s, [[shovel]]s, small bowls and, remarkably, ivory pins up to {{convert|25|cm|in}} long.<ref>{{harvnb|Clarke|Sharples|1985|pp=78–81}}</ref> These pins are similar to examples found in [[passage grave]]s in the Boyne Valley, another piece of evidence suggesting a linkage between the two cultures.<ref>{{harvnb|Ritchie|1981|p=41 }}</ref> The eponymous ''Skaill knife'' was a commonly used tool in Skara Brae; it consists of a large stone flake, with a sharp edge used for cutting, knocked off a sandstone cobble.<ref>{{harvnb|Ritchie|1995|p=16}}</ref> This neolithic tool is named after Skara Brae's location in the [[Bay of Skaill]] on [[Orkney]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Skaill knife |website=[[Historic Scotland]] |url=http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/skaraobjects.pdf |access-date=21 March 2007}}</ref> Skaill knives have been found throughout Orkney and [[Shetland]]. |

|||

The 1972 excavations reached layers that had remained waterlogged and had preserved items that otherwise would have been destroyed. These include a twisted skein of heather, one of a very few known examples of Neolithic rope.<ref>{{harvnb|Burl|1979|p=144}}</ref> and a wooden handle.<ref>{{harvnb|Hedges|1984|p=215}}</ref> |

|||

The 1972 excavations reached layers that had remained waterlogged and had preserved items that otherwise would have been destroyed. These include a twisted skein of heather, one of a very few known examples of Neolithic rope,<ref>{{harvnb|Burl|1979|p=144}}</ref> and a wooden handle.<ref>{{harvnb|Hedges|1984|p=215}}</ref> |

|||

==Related sites in Orkney== |

==Related sites in Orkney== |

||

[[File:Skarabrae5.jpg|alt=Skara Brae in the sunshine|thumb|Skara Brae in the sunshine]] |

|||

A comparable, though smaller, site exists at [[Rinyo]] on [[Rousay]]. Unusually, no [[Maeshowe]]-type tombs have been found on Rousay and although there are a large number of Orkney–Cromarty chambered [[cairn]]s, these were built by [[Unstan ware]] people. |

|||

[[Knap of Howar]], on the Orkney island of [[Papa Westray]], is a well-preserved Neolithic farmstead. Dating from 3500 BC to 3100 BC, it is similar in design to Skara Brae, but from an earlier period, and it is thought to be the oldest preserved standing building in northern Europe.<ref name = "Knap of Howar">{{Cite web | url=http://www.orkneyjar.com/history/knaphowar.htm | title=The Knap o' Howar, Papay | publisher=Orkneyjar | access-date=5 September 2007}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Barnhouse Settlement]] is by [[Loch of Harray]] on the Orkney Mainland, not far from the [[Standing Stones of Stenness]].<ref>{{Cite web|date=2020-12-21|title=The Barnhouse Settlement|url=https://www.nessofbrodgar.co.uk/around-the-ness-the-barnhouse-settlement/|access-date=2022-02-21|website=The Ness of Brodgar Excavation|language=en-GB}}</ref> Excavations were conducted between 1986 and 1991, over time revealing the base courses of at least 15 houses. The houses have similarities to those of the early phase of Skara Brae in that they have central hearths, beds built against the walls and stone dressers, and internal drains,<ref>{{Cite web|title=Barnhouse {{!}} Canmore|url=https://canmore.org.uk/site/2152/barnhouse|access-date=2020-06-27|website=canmore.org.uk|language=en}}</ref> but differ in that the houses seem to have been free-standing. The settlement dates back to circa 3000 BC.<ref name="Agenda">{{Cite book | title = The Heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site Research Agenda| publisher = Historic Scotland| volume =Part 2 | year =2005 | url =http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/orkney-agenda-part2.pdf| isbn =1-904-966-04-7 }}</ref>{{rp|52}} |

|||

[[Knap of Howar]] on the Orkney island of [[Papa Westray]], is a well preserved Neolithic farmstead. Dating from 3500 BCE to 3100 BCE, it is similar in design to Skara Brae, but from an earlier period, and it is thought to be the oldest preserved standing building in northern Europe.<ref name = "Knap of Howar"> |

|||

{{Cite web |

|||

A comparable, though smaller, site exists at [[Rinyo]] on [[Rousay]], Orkney. Unusually, no [[Maeshowe]]-type tombs have been found on Rousay and although there are a large number of [[Chambered cairn#Orkney-Cromarty|Orkney–Cromarty chambered cairn]]s, these were built by [[Unstan ware]] people. |

|||

|url=http://www.orkneyjar.com/history/knaphowar.htm |

|||

|title=The Knap o' Howar, Papay |

|||

|publisher=Orkneyjar |

|||

|accessdate=5 September 2007 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

There is also a site currently under excavation at [[Links of Noltland]] on [[Westray]] that appears to have similarities to Skara Brae.<ref>{{harvnb|Darvill|1987|p=105}}</ref> |

There is also a site currently under excavation at [[Links of Noltland]] on [[Westray]] that appears to have similarities to Skara Brae.<ref>{{harvnb|Darvill|1987|p=105}}</ref> |

||

==World Heritage status== |

==World Heritage status== |

||

[[File:Skara Brae ground plan 1950.jpg|thumb|right|Site Plan]] |

|||

"The [[Heart of Neolithic Orkney]]" was inscribed as a World Heritage site in December 1999. In addition to Skara Brae the site includes [[Maeshowe]], the [[Ring of Brodgar]], the [[Standing Stones of Stenness]] and other nearby sites. It is managed by [[Historic Scotland]], whose 'Statement of Significance' for the site begins: |

|||

"The [[Heart of Neolithic Orkney]]" was inscribed as a World Heritage site in December 1999. In addition to Skara Brae the site includes [[Maeshowe]], the [[Ring of Brodgar]], the [[Standing Stones of Stenness]] and other nearby sites. It is managed by [[Historic Environment Scotland]], whose "Statement of Significance" for the site begins: |

|||

{{Quote|The monuments at the heart of Neolithic Orkney and Skara Brae proclaim the triumphs of the human spirit in early ages and isolated places. They were approximately contemporary with the |

{{Quote|The monuments at the heart of Neolithic Orkney and Skara Brae proclaim the triumphs of the human spirit in early ages and isolated places. They were approximately contemporary with the [[mastaba]]s of the archaic period of Egypt (first and second dynasties), the brick temples of Sumeria, and the first cities of the Harappa culture in India, and a century or two earlier than the Golden Age of China. Unusually fine for their early date, and with a remarkably rich survival of evidence, these sites stand as a visible symbol of the achievements of early peoples away from the traditional centres of civilisation.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/index/policyandguidance/world_heritage_scotland/world_heritage_sites/world-heritage-neolithic-orkney.htm |title=The Heart of Neolithic Orkney |publisher=Historic Scotland |access-date=5 September 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070911121359/http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/index/policyandguidance/world_heritage_scotland/world_heritage_sites/world-heritage-neolithic-orkney.htm |archive-date=11 September 2007 }}</ref> |

||

{{Cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/index/policyandguidance/world_heritage_scotland/world_heritage_sites/world-heritage-neolithic-orkney.htm |

|||

|title=The Heart of Neolithic Orkney |

|||

|publisher=Historic Scotland |

|||

|accessdate=5 September 2007 |

|||

}}{{Dead link|date=November 2011}}</ref> |

|||

}}<!-- end of quote template --> |

}}<!-- end of quote template --> |

||

Some areas and facilities were closed due to the worldwide [[COVID-19 pandemic]] during parts of 2020 and into 2021.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.historicenvironment.scot/visit-a-place/places/skara-brae/prices-and-opening-times/ |title=Prices and opening times |date=1 February 2021 |work=Historic Environment Scotland |access-date=13 February 2021 |quote=Some areas/facilities will remain closed for now, we have a phased approach to re-opening while we work to make them safe}}</ref> |

|||

==Contemporary culture== |

|||

==Risk from climate change== |

|||

In 2019, a risk assessment was performed to assess the site's [[Climate change vulnerability|vulnerability to climate change]]. The report by [[Historic Environment Scotland]], the [[Orkney Islands Council]] and others concludes that the entire Heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site, and in particular Skara Brae, is "extremely vulnerable" to climate change due to rising sea levels, increased rainfall and other factors; it also highlights the risk that Skara Brae could be partially destroyed by one unusually severe storm.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-48840948 |title=Orkney world heritage sites threatened by climate change |author=James Cook |publisher=BBC |date=2 July 2019 |access-date=8 July 2019 }}</ref> |

|||

==In popular culture== |

|||

<!--PLEASE DO NOT ADD IRRELEVANT TRIVIA ABOUT COMPUTER GAMES - see below --> |

<!--PLEASE DO NOT ADD IRRELEVANT TRIVIA ABOUT COMPUTER GAMES - see below --> |

||

*The 1968 children's novel ''The Boy with the Bronze Axe'' by [[Kathleen Fidler]] is set during the last days of Skara Brae.{{sfn|Bramwell|2009|pp=182–185}}<ref>{{harvnb|Fidler|2005}}</ref> This theme is also adopted by [[Rosemary Sutcliff]] in her 1977 novel ''Shifting Sands'', in which the evacuation of the site is portrayed as unhurried, with most of the inhabitants surviving.{{sfn|Bramwell|2009|pp=185–186}} |

|||

*The children's novel ''Il tesoro di Skara Brae'' by Diletta Nicastro is the second episode of the series ''The World of Mauro & Lisi'', a saga set in Skara Brae and other Neolithic sites in the area.<ref>{{harvnb|Nicastro|2007}}</ref> |

|||

*The [[Music of Ireland|Irish traditional music]] group [[Skara Brae (band)|Skara Brae]] took their name from the settlement. Their only album ''[[Skara Brae (album)|Skara Brae]]'' was released in 1971 and reissued on CD in 1998. |

|||

*The children's novel ''The Boy with the Bronze Axe'' by [[Kathleen Fidler]] is set during the last days of Skara Brae.<ref>{{harvnb|Fidler|2005}}</ref> |

|||

*A stone was unveiled in Skara Brae on 12 April 2008 marking the anniversary of |

*A stone was unveiled in Skara Brae on 12 April 2008 marking the anniversary of Soviet cosmonaut [[Yuri Gagarin]] becoming the first man to orbit the Earth in 1961.<ref name="Gagarin1"> |

||

{{ |

{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/scotland/north_east/7341133.stm | title=Orkney site marks space race date | work=[[BBC News]] |date=12 April 2008 |access-date=21 April 2008}}</ref><ref name="Gagarin2"> |

||

{{cite news|url=http://thescotsman.scotsman.com/world/Prehistoric-honour-for-first-man.3975474.jp|title=Prehistoric honour for first man in space|last=Ross|first=John|newspaper=[[The Scotsman]]|place=[[Edinburgh]]|date=12 April 2008|access-date=21 April 2008}}</ref> |

|||

|publisher=[[BBC News]] |date=12 April 2008 |accessdate=21 April 2008}}</ref><ref name="Gagarin2"> |

|||

* The video game ''[[The Bard's Tale]]'' takes place in a fictionalised version of Skara Brae. |

|||

{{Cite news|url=http://thescotsman.scotsman.com/world/Prehistoric-honour-for-first-man.3975474.jp|title=Prehistoric honour for first man in space|last=Ross|first=John|publisher=[[The Scotsman]]|place=[[Edinburgh]]|date=12 April 2008|accessdate=21 April 2008}}</ref> |

|||

* The video game ''[[Starsiege: Tribes]]'' features an iconic map named "Scarabrae". |

|||

*Skara Brae is a location in the computer game ''[[Bard's Tale (1985)|The Bard's Tale]]'', which is set in a fictionalised Orkney.<ref>[http://www.thebardstale.com/about.html "About The Bard's Tale"]. thebardstale.com. Retrieved 3 November 2012.</ref> |

|||

* |

* The video game series ''[[Ultima (series)|Ultima]]'' includes the city of Skara Brae, which is on an island to the west of the main continent. It is devoted to the virtue of Spirituality, located next to a moongate and is the home of Shamino the Ranger.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://wiki.ultimacodex.com/wiki/Skara_Brae|title=Skara Brae - The Codex of Ultima Wisdom, a wiki for Ultima and Ultima Online|website=wiki.ultimacodex.com|access-date=18 September 2018}}</ref> |

||

*In [[Kim Stanley Robinson]]'s 1991 |

* In [[Kim Stanley Robinson]]'s 1991 novelette ''A History of the Twentieth Century, with Illustrations'', the main character visits Skara Brae and other Orkney Island neolithic sites as part of a journey he takes to gain perspective on the violent history of the 20th century.<ref>[http://www.infinityplus.co.uk/stories/history.htm "A History of the Twentieth Century, with Illustrations"]. Retrieved 5 March 2013.</ref> |

||

* In the |

* In the film ''[[Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull]]'', Jones is shown lecturing to his students about the site,<ref name="SB"> |

||

{{cite book|last=Clarke|first=David|title=Skara Brae|publisher=Historic Scotland|year=2012|isbn=978-1-84917-074-1}}</ref>{{rp|6}} where he gives the date as "3100 BC". |

|||

* Skara Brae is used as the name for a New York Scottish pub in the [[IDW Publishing|IDW]] [[Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (IDW Publishing)|''Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles'' comic series]].<ref>''Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles'' Annual (2012). IDW, October 31, 2011.</ref> |

|||

<!--PLEASE DO NOT ADD IRRELEVANT TRIVIA ABOUT COMPUTER GAMES e.g. that Skara Brae is the name of a city in the Ultima game, unless there is some relevance to this article beyond the mere co-incidence of the name. See Skara Brae (disambiguation) and [[Talk:Skara Brae]] for more information . --> |

|||

* Skara Brae's ancient sewer system and its use of running water is referenced by Medical Examiner [[List of NCIS characters#Dr. Donald "Ducky" Mallard|Dr. Donald "Ducky" Mallard]] in [[NCIS (TV series)|''NCIS'']] episode [[NCIS season 6|"Murder 2.0" (season 6, episode 6)]].<ref>{{Cite episode |title=Murder 2.0 |series=NCIS |network=CBS |date=28 October 2008 |season=6 |number=6}}</ref> |

|||

<!--PLEASE DO NOT ADD IRRELEVANT TRIVIA ABOUT COMPUTER GAMES e.g. that Skara Brae is the name of a city in the Ultima game, unless there is some relevance to this article beyond the mere coincidence of the name. See Skara Brae (disambiguation) and [[Talk:Skara Brae]] for more information . --> |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

{{div col}} |

|||

* [[Ring of Brodgar]] |

|||

* [[Standing Stones of Stenness]] |

|||

* [[Maeshowe]] |

* [[Maeshowe]] |

||

* [[ |

* [[Ness of Brodgar]] |

||

* [[Skaill House]] |

|||

* [[World Heritage Sites in Scotland]] |

|||

* [[Standing Stones of Stenness]] |

|||

* [[Zenith of Iron Age Shetland]] |

|||

* [[Timeline of prehistoric Scotland]] |

* [[Timeline of prehistoric Scotland]] |

||

* [[List of oldest buildings]] |

|||

* [[Oldest buildings in the United Kingdom]] |

|||

* [[List of |

* [[List of oldest buildings in the United Kingdom]] |

||

* [[List of World Heritage Sites in Scotland]] |

|||

{{div col end}} |

|||

==Notes== |

==Notes== |

||

{{Notelist}} |

|||

{{Note|1|a|It is one of four [[UNESCO]] [[World Heritage Site]]s in Scotland, the others being the [[Old Town, Edinburgh|Old Town]] and [[New Town, Edinburgh|New Town]] of [[Edinburgh]]; [[New Lanark]] in [[South Lanarkshire]]; and [[St Kilda, Scotland|St Kilda]] in the [[Western Isles]]}} |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist |

{{Reflist}} |

||

==Bibliography== |

==Bibliography== |

||

*{{cite book | last1 = Beck | first1 = Roger B. | last2 = Black | first2 = Linda | first3 = Larry S. | last3 = Krieger | first4 = Phillip C. | last4 = Naylor | first5 = Dahia Ibo | last5 = Shabaka | title = World History: Patterns of Interaction | publisher = McDougal Littell | year = 1999 | location = Evanston, IL | url =https://archive.org/details/mcdougallittellw00beck| url-access = registration | isbn = 0-395-87274-X }} |

|||

*{{cite book |last=Bramwell |first=Peter |year=2009 |title=Pagan Themes in Modern Children's Fiction: Green Man, Shamanism, Earth Mysteries |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |location=New York |isbn=978-0-230-21839-0 }} |

|||

*{{cite book | last = Beck | first = Roger B. | authorlink = | last2 = Black | first2 = Linda | first3 = Larry S. | last3 = Krieger | first4 = Phillip C. | last4 = Naylor | first5 = Dahia Ibo | last5 = Shabaka | title = World History: Patterns of Interaction | publisher = McDougal Littell | year = 1999 | location = Evanston, IL | pages = | url = | doi = | id = | isbn = 0-395-87274-X | ref = harv}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last = Bryson | first = Bill | |

*{{cite book | last = Bryson | first = Bill | author-link = Bill Bryson | title = At home: a short history of private life | publisher = Doubleday | year = 2010 | location = London; New York | url =https://archive.org/details/athomeshorthisto00brys| url-access = registration | isbn = 978-0-385-60827-5 }} |

||

*{{cite book | |

*{{cite book | last1 = Buckland | first1 = Paul C. | first2 = Jon P. |last2 = Sadler | chapter = Insects | editor1-last = Edwards | editor1-first = Kevin J. | editor2-last = Ralston | editor2-first = Ian B.M. | title = Scotland After the Ice Age: Environment, Archaeology and History, 8000 BC – AD 1000 | publisher = Edinburgh University Press |year = 2003 |location = Edinburgh | isbn = 0-7486-1736-1 }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = Burl | first = Aubrey | |

*{{cite book | last = Burl | first = Aubrey | author-link =Aubrey Burl| title = The Stone Circles of the British Isles | publisher = Yale University Press | year = 1976 | location = London | isbn = 0-300-01972-6 | url = https://archive.org/details/stonecirclesof00burl }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = Burl | first = Aubrey |

*{{cite book | last = Burl | first = Aubrey | title = Prehistoric Avebury | publisher = Yale University Press | year = 1979 | location = London | isbn = 0-300-02368-5 | url = https://archive.org/details/prehistoricavebu00burl }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = Castleden | first = Rodney |

*{{cite book | last = Castleden | first = Rodney | title = The Stonehenge People | publisher = Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. | year = 1987 | location = London | isbn = 0-7102-0968-1 | url-access = registration | url = https://archive.org/details/stonehengepeople0000cast }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = Childe | first = V. Gordon | |

*{{cite book | last = Childe | first = V. Gordon | author-link = V. Gordon Childe | title = Skara Brae, a Pictish Village in Orkney | publisher = monograph of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland | year = 1931 | location = meeting held in London }} |

||

*{{cite book | |

*{{cite book | last1 = Childe | first1 = V. Gordon | last2 = Simpson | first2 = W. Douglas | title = Illustrated History of Ancient Monuments: Vol. VI Scotland | publisher = Her Majesty's Stationery Office | year = 1952 | location = Edinburgh }} |

||

*{{cite book | |

*{{cite book | last1 = Childe | first1 = V. Gordon | first2 = D. V. | last2 = Clarke | title = Skara Brae | publisher = Her Majesty's Stationery Office | year = 1983 | location = Edinburgh | isbn = 0-11-491755-8 }} |

||

*{{cite book | |

*{{cite book | last1 = Clarke | first1 = D.V.| last2 = Sharples | first2 = Niall| title = Settlements and Subsistence in the Third Millennium BC, in: Renfrew, Colin (Ed.) The Prehistory of Orkney BC 4000–1000 AD | publisher = Edinburgh University Press | year = 1985 | location = Edinburgh| isbn = 0-85224-456-8 }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = Darvill | first = Timothy |

*{{cite book | last = Darvill | first = Timothy | title = Prehistoric Britain | publisher = Yale University Press | year = 1987 | location = London | isbn = 0-300-03951-4 | url = https://archive.org/details/prehistoricbrita00darv_0 }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = Fenton | first = Alexander |

*{{cite book | last = Fenton | first = Alexander | title = Northern Isles: Orkney and Shetland | publisher = John Donald Publishers Ltd | year = 1978 | isbn = 0-85976-019-7 | url = https://archive.org/details/northernislesork00fent }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = Fidler | first = Kathleen | title = The Boy with the Bronze Axe | publisher = Floris Books | year = 2005 | location = Edinburgh | isbn = 978-0-86315-488-1 |

*{{cite book | last = Fidler | first = Kathleen | title = The Boy with the Bronze Axe | publisher = Floris Books | year = 2005 | location = Edinburgh | isbn = 978-0-86315-488-1 }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = Hadingham | first = Evan | title = Circles and Standing Stones: An Illustrated Exploration of the Megalith Mysteries of Early Britain | publisher = Walker and Company | year = 1975 | location = New York | isbn = 0-8027-0463-8 | |

*{{cite book | last = Hadingham | first = Evan | title = Circles and Standing Stones: An Illustrated Exploration of the Megalith Mysteries of Early Britain | publisher = Walker and Company | year = 1975 | location = New York | isbn = 0-8027-0463-8 | url = https://archive.org/details/circlesstandings00evan_0 }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = Hawkes | first = Jacquetta | |

*{{cite book | last = Hawkes | first = Jacquetta | author-link = Jacquetta Hawkes| title = The Shell Guide to British Archaeology | url = https://archive.org/details/shellguidetobrit0000hawk | url-access = registration | publisher = Michael Joseph | year = 1986 | location = London | isbn = 0-7181-2448-0 }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = Hedges | first = John W. |

*{{cite book | last = Hedges | first = John W. | title = Tomb of the Eagles: Death and Life in a Stone Age Tribe | publisher = New Amsterdam | year = 1984 | location = New York | isbn = 0-941533-05-0 }} |

||

*{{cite journal | doi = 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1979.tb02684.x | |

*{{cite journal | doi = 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1979.tb02684.x | last1 = Keatinge | first1 = T.H. | last2 = Dickson | first2 = J.H. | title = Mid Flandrian Changes in Vegetation in Mainland Orkney | journal = New Phytol | volume = 82 | issue = 2 | pages = 585–612 | year = 1979 | doi-access = free }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = Laing | first = Lloyd |

*{{cite book | last = Laing | first = Lloyd | title = Orkney and Shetland: An Archaeological Guide | publisher = David and Charles Ltd. | year = 1974 | location = Newton Abbott | isbn = 0-7153-6305-0 }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = Laing | first = Lloyd & Jennifer |

*{{cite book | last = Laing | first = Lloyd & Jennifer | title = The Origins of Britain | publisher = Paladin | year = 1982 | location = London | isbn = 0-586-08370-7 }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = MacKie | first = Euan | title = Science and Society in Prehistoric Britain | publisher = Palgrave Macmillan | year = 1977 | location = London | isbn = 0-312-70245-0 |

*{{cite book | last = MacKie | first = Euan | title = Science and Society in Prehistoric Britain | publisher = Palgrave Macmillan | year = 1977 | location = London | isbn = 0-312-70245-0 }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = |

*{{cite book | last = Piggott | first = Stuart | title = Neolithic Cultures of the British Isles | publisher = Cambridge University Press | year = 1954 | isbn = 0-521-07781-8 }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = |

*{{cite book | last = Ritchie | first = Anna | title = Prehistoric Orkney | publisher = B.T. Batsford Ltd.| year = 1995 | location = London | isbn = 0-7134-7593-5 }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = Ritchie | first = Graham & Anna |

*{{cite book | last = Ritchie | first = Graham & Anna | title = Scotland: Archaeology and Early History | publisher = Thames and Hudson | year = 1981 | location = New York | isbn = 0-500-27365-0 }} |

||

*{{cite book | last = Ritchie | first = Anna | authorlink = | author2 = | title = Prehistoric Orkney | publisher = B.T. Batsford Ltd.| year = 1995 | location = London | pages = | isbn = 0-7134-7593-5 | ref = harv}} |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

| Line 186: | Line 192: | ||

|url=http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/index/places/propertyresults/propertyoverview.htm?PropID=PL_244 |

|url=http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/index/places/propertyresults/propertyoverview.htm?PropID=PL_244 |

||

|title=Historic Scotland: Skara Brae Prehistoric Village |

|title=Historic Scotland: Skara Brae Prehistoric Village |

||

| |

|access-date= 3 November 2011 |

||

}} |

|||

*{{Cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.orkneyjar.com/history/skarabrae/index.html |

|||

|title=Orkneyjar : Skara Brae : The discovery of the village |

|||

|accessdate= 3 November 2011 |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

*{{Cite web |

*{{Cite web |

||

|url=http://canmore.rcahms.gov.uk/en/site/1663/details/skara+brae/ |

|url=http://canmore.rcahms.gov.uk/en/site/1663/details/skara+brae/ |

||

|title=Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland |

|title=Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland: Site Record for Skara Brae |

||

| |

|access-date= 3 November 2011 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

* [ |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20140714161324/http://skaillhouse.co.uk/skarabrae.asp Skaill House, Bay of Skaill, home of excavator William Watt] |

||

<!-- Categorization --> |

<!-- Categorization --> |

||

<!-- Localization --> |

<!-- Localization --> |

||

{{Prehistoric Orkney}} |

{{Prehistoric Orkney}} |

||

{{European |

{{European megaliths}} |

||

{{Prehistoric technology}} |

{{Prehistoric technology}} |

||

{{World Heritage Site 'Tentative List' applicants in Scotland}} |

{{World Heritage Site 'Tentative List' applicants in Scotland}} |

||

{{World Heritage Sites in the United Kingdom}} |

{{World Heritage Sites in the United Kingdom}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

{{coord|59|02|55|N|3|20|35|W|region:GB_type:landmark|display=title}} |

|||

[[Category:4th-millennium BC architecture in Scotland]] |

[[Category:4th-millennium BC architecture in Scotland]] |

||

| Line 215: | Line 216: | ||

[[Category:Prehistoric Orkney]] |

[[Category:Prehistoric Orkney]] |

||

[[Category:Buildings and structures in Orkney]] |

[[Category:Buildings and structures in Orkney]] |

||

[[Category:Scheduled |

[[Category:Scheduled monuments in Scotland]] |

||

[[Category:Stone Age sites in Scotland]] |

[[Category:Stone Age sites in Scotland]] |

||

[[Category:World Heritage Sites in Scotland]] |

[[Category:World Heritage Sites in Scotland]] |

||

| Line 227: | Line 228: | ||

[[Category:Neolithic Scotland]] |

[[Category:Neolithic Scotland]] |

||

[[Category:Semi-subterranean structures]] |

[[Category:Semi-subterranean structures]] |

||

[[Category:4th-millennium BC establishments |

[[Category:4th-millennium BC establishments]] |

||

[[Category:Mainland, Orkney]] |

|||

[[Category:Heart of Neolithic Orkney]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 21:02, 22 December 2024

Skara Brae from the entrance gate | |

| |

| Location | Mainland, Orkney, Scotland |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 59°02′55″N 3°20′30″W / 59.0487138°N 3.3417499°W |

| Type | Neolithic settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | 3180 BC; 5204 years ago |

| Periods | Neolithic |

| Site notes | |

| Ownership | Historic Environment Scotland |

| Public access | Yes |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv |

| Designated | 1999 (23rd session) |

| Part of | Heart of Neolithic Orkney |

| Reference no. | 514 |

| Region | Europe |

| Identifiers | |

| Historic Environment Scotland | SM90276 |

Skara Brae /ˈskærə ˈbreɪ/ is a stone-built Neolithic settlement, located on the Bay of Skaill in the parish of Sandwick, on the west coast of Mainland, the largest island in the Orkney archipelago of Scotland. It consisted of ten clustered houses, made of flagstones, in earthen dams that provided support for the walls; the houses included stone hearths, beds, and cupboards.[1] A primitive sewer system, with "toilets" and drains in each house,[2][3] included water used to flush waste into a drain and out to the ocean.[4]

The site was occupied from roughly 3180 BC to about 2500 BC and is Europe's most complete Neolithic village. Skara Brae gained UNESCO World Heritage Site status as one of four sites making up "The Heart of Neolithic Orkney".[a] Older than Stonehenge and the Great Pyramids of Giza, it has been called the "Scottish Pompeii" because of its excellent preservation.[5]

Care of the site is the responsibility of Historic Environment Scotland which works with partners in managing the site: Orkney Islands Council, NatureScot (Scottish Natural Heritage), and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.[6] Visitors to the site are welcome during much of the year.

Uncovered by a storm in 1850, the coastal site may now be at risk from climate change.

Discovery and early exploration

[edit]In the winter of 1850, a severe storm hit Scotland, causing widespread damage and over 200 deaths.[7] In the Bay of Skaill, the storm stripped earth from a large irregular knoll. (The name Skara Brae is a corruption of Skerrabra or Styerrabrae, which originally referred to the knoll.[3]) When the storm cleared, local villagers found the outline of a village consisting of several small houses without roofs.[7][8] William Graham Watt of Skaill House,[9] a son of the local laird who was a self-taught geologist, began an amateur excavation of the site, but after four houses were uncovered, work was abandoned in 1868.[10]

The site remained undisturbed until 1913, when during a single weekend, the site was plundered by a party with shovels who took away an unknown quantity of artefacts.[7] In 1924, another storm swept away part of one of the houses, and it was determined the site should be secured and properly investigated.[7] The job was given to the University of Edinburgh's Professor V. Gordon Childe, who travelled to Skara Brae for the first time in mid-1927.[7]

In 2019 a series of photographs showing Childe and four women at the site of the excavation were re-examined. It had been widely believed that the women were tourists or local women visiting the excavation site, but a note on the back of of the photographs identified the women as "4 of [Childe's] lady students", and it seems that they were active participants in the excavation.[11] The women have been tentatively identified as Margaret E. B. Simpson (who was acknowledged in Childe's monographs about Skara Brae), Margaret Mitchell, Mary Kennedy and Margaret Cole.[12]

Neolithic lifestyle

[edit]The inhabitants of Skara Brae were makers and users of grooved ware, a distinctive style of pottery that had recently appeared in northern Scotland.[13] The houses used earth sheltering: built sunk in the ground, into mounds of prehistoric domestic waste known as middens. This provided the houses with stability and also acted as insulation against Orkney's harsh winter climate. On average, each house measures 40 square metres (430 sq ft) with a large square room containing a stone hearth used for heating and cooking. Given the number of homes, it seems likely that no more than fifty people lived in Skara Brae at any given time.[14]

It is not clear what material the inhabitants burned in their hearths. Childe was sure that the fuel was peat,[15] but a detailed analysis of vegetation patterns and trends suggests climatic conditions conducive to the development of thick beds of peat did not develop in this part of Orkney until after Skara Brae was abandoned.[16] Other possible fuels include driftwood and animal dung. There is evidence that dried seaweed may have been used significantly. At some sites in Orkney, investigators have found a glassy, slag-like material called "kelp" or "cramp" which may be residual burnt seaweed.[17]

The dwellings contain several stone-built pieces of furniture, including cupboards, dressers, seats, and storage boxes. Each dwelling was entered through a low doorway with a stone slab door which could be shut "by a bar made of bone that slid in bar-holes cut in the stone door jambs."[18] Several dwellings offered a small connected antechamber, offering access to a partially covered stone drain leading away from the village. It is suggested that these chambers served as indoor toilets.[19][20][3][21]

Seven of the houses have similar furniture, with the beds and dressers in the same places in each house. The dresser stands against the wall opposite the door and is the first thing seen by anyone entering the dwelling. Each of these houses had a larger bed on the right side of the doorway and a smaller one on the left. Lloyd Laing noted that this pattern accorded with Hebridean custom up to the early 20th century suggesting that the husband's bed was the larger and the wife's was the smaller.[22] The discovery of beads and paint pots in some of the smaller beds may support this interpretation. Additional support may come from the recognition that stone boxes lie to the left of most doorways, forcing the person entering the house to turn to the right-hand, "male", side of the dwelling.[23] At the front of each bed lie the stumps of stone pillars that may have supported a canopy of fur; another link with recent Hebridean style.[24]

House 8 has no storage boxes or dresser and has been divided into something resembling small cubicles. Fragments of stone, bone, and antler were excavated suggesting House 8 may have been used to make tools such as bone needles or flint axes.[25] The presence of heat-damaged volcanic rocks and what appears to be a flue, supports this interpretation. House 8 is distinctive in other ways as well: it is a stand-alone structure not surrounded by midden;[26] instead it is above ground with walls over 2 metres (6.6 ft) thick and has a "porch" protecting the entrance.

The site provided the earliest known record of the human flea (Pulex irritans) in Europe.[27]

The Grooved Ware People who built Skara Brae were primarily pastoralists who raised cattle, pig and sheep.[15] Childe originally believed that the inhabitants did not farm, but excavations in 1972 unearthed seed grains from a midden suggesting that barley was cultivated.[28] Fish bones and shells are common in the midden indicating that dwellers ate seafood. Limpet shells are standard and may have been fish bait that was kept in stone boxes in the homes.[29] The boxes were formed from thin slabs with joints carefully sealed with clay to render them waterproof.

This pastoral lifestyle is in sharp contrast to some of the more exotic interpretations of the culture of the Skara Brae people. Euan MacKie suggested that Skara Brae might be the home of a privileged theocratic class of wise men who engaged in astronomical and magical ceremonies at nearby Ring of Brodgar and the Standing Stones of Stenness.[30] Graham and Anna Ritchie cast doubt on this interpretation noting there is no archaeological evidence for this claim,[31] although a Neolithic "low road" that goes from Skara Brae passes near both these sites and ends at the chambered tomb of Maeshowe.[32] Low roads connect Neolithic ceremonial sites throughout Britain.

Dating and abandonment

[edit]Originally, Childe believed that the settlement dated from around 500 BC.[15] This interpretation was coming under increasing challenge by the time new excavations in 1972–73 settled the question. Radiocarbon results obtained from samples collected during these excavations indicate that occupation of Skara Brae began about 3180 BC[33] with occupation continuing for about six hundred years.[34] Around 2500 BC, after the climate changed, becoming much colder and wetter, the settlement may have been abandoned by its inhabitants. There are many theories as to why the people of Skara Brae left; particularly popular interpretations involving a major storm. Evan Hadingham combined evidence from found objects with the storm scenario to imagine a dramatic end to the settlement:

As was the case at Pompeii, the inhabitants seem to have been taken by surprise and fled in haste, for many of their prized possessions, such as necklaces made from animal teeth and bone, or pins of walrus ivory, were left behind. The remains of choice meat joints were discovered in some of the beds, presumably forming part of the villagers' last supper. One woman was in such haste that her necklace broke as she squeezed through the narrow doorway of her home, scattering a stream of beads along the passageway outside as she fled the encroaching sand.[35]

Anna Ritchie strongly disagrees with catastrophic interpretations of the village's abandonment:

A popular myth would have the village abandoned during a massive storm that threatened to bury it in sand instantly, but the truth is that its burial was gradual and that it had already been abandoned – for what reason, no one can tell.[36]

The site was farther from the sea than it is today, and it is possible that Skara Brae was built adjacent to a fresh water lagoon protected by dunes.[33] Although the visible buildings give an impression of an organic whole, certainly, an unknown quantity of additional structures had already been lost to sea erosion before the site's rediscovery and subsequent protection by a seawall.[37] Uncovered remains are known to exist immediately adjacent to the ancient monument in areas presently covered by fields, and others, of uncertain date, can be seen eroding out of the cliff edge a little to the south of the enclosed area.

Artefacts

[edit]

A number of enigmatic carved stone balls have been found at the site and some are on display in the museum.[38] Similar objects have been found throughout northern Scotland. The spiral ornamentation on some of these "balls" has been stylistically linked to objects found in the Boyne Valley in Ireland.[39][40] Similar symbols have been found carved into stone lintels and bed posts.[15] These symbols, sometimes referred to as "runic writings", have been subjected to controversial translations. For example, author Rodney Castleden suggested that "colons" found punctuating vertical and diagonal symbols may represent separations between words.[41]

Lumps of red ochre found here and at other Neolithic sites have been interpreted as evidence that body painting may have been practised.[42]

Nodules of haematite with polished surfaces have been found as well; the shiny surfaces suggest that the nodules were used to finish leather.[43]

Other artefacts excavated on site made of animal, fish, bird, and whalebone, whale and walrus ivory, and orca teeth included awls, needles, knives, beads, adzes, shovels, small bowls and, remarkably, ivory pins up to 25 centimetres (9.8 in) long.[44] These pins are similar to examples found in passage graves in the Boyne Valley, another piece of evidence suggesting a linkage between the two cultures.[45] The eponymous Skaill knife was a commonly used tool in Skara Brae; it consists of a large stone flake, with a sharp edge used for cutting, knocked off a sandstone cobble.[46] This neolithic tool is named after Skara Brae's location in the Bay of Skaill on Orkney.[47] Skaill knives have been found throughout Orkney and Shetland.

The 1972 excavations reached layers that had remained waterlogged and had preserved items that otherwise would have been destroyed. These include a twisted skein of heather, one of a very few known examples of Neolithic rope,[48] and a wooden handle.[49]

Related sites in Orkney

[edit]

Knap of Howar, on the Orkney island of Papa Westray, is a well-preserved Neolithic farmstead. Dating from 3500 BC to 3100 BC, it is similar in design to Skara Brae, but from an earlier period, and it is thought to be the oldest preserved standing building in northern Europe.[50]

The Barnhouse Settlement is by Loch of Harray on the Orkney Mainland, not far from the Standing Stones of Stenness.[51] Excavations were conducted between 1986 and 1991, over time revealing the base courses of at least 15 houses. The houses have similarities to those of the early phase of Skara Brae in that they have central hearths, beds built against the walls and stone dressers, and internal drains,[52] but differ in that the houses seem to have been free-standing. The settlement dates back to circa 3000 BC.[53]: 52

A comparable, though smaller, site exists at Rinyo on Rousay, Orkney. Unusually, no Maeshowe-type tombs have been found on Rousay and although there are a large number of Orkney–Cromarty chambered cairns, these were built by Unstan ware people.

There is also a site currently under excavation at Links of Noltland on Westray that appears to have similarities to Skara Brae.[54]

World Heritage status

[edit]

"The Heart of Neolithic Orkney" was inscribed as a World Heritage site in December 1999. In addition to Skara Brae the site includes Maeshowe, the Ring of Brodgar, the Standing Stones of Stenness and other nearby sites. It is managed by Historic Environment Scotland, whose "Statement of Significance" for the site begins:

The monuments at the heart of Neolithic Orkney and Skara Brae proclaim the triumphs of the human spirit in early ages and isolated places. They were approximately contemporary with the mastabas of the archaic period of Egypt (first and second dynasties), the brick temples of Sumeria, and the first cities of the Harappa culture in India, and a century or two earlier than the Golden Age of China. Unusually fine for their early date, and with a remarkably rich survival of evidence, these sites stand as a visible symbol of the achievements of early peoples away from the traditional centres of civilisation.[55]

Some areas and facilities were closed due to the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic during parts of 2020 and into 2021.[56]

Risk from climate change

[edit]In 2019, a risk assessment was performed to assess the site's vulnerability to climate change. The report by Historic Environment Scotland, the Orkney Islands Council and others concludes that the entire Heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site, and in particular Skara Brae, is "extremely vulnerable" to climate change due to rising sea levels, increased rainfall and other factors; it also highlights the risk that Skara Brae could be partially destroyed by one unusually severe storm.[57]

In popular culture

[edit]- The 1968 children's novel The Boy with the Bronze Axe by Kathleen Fidler is set during the last days of Skara Brae.[58][59] This theme is also adopted by Rosemary Sutcliff in her 1977 novel Shifting Sands, in which the evacuation of the site is portrayed as unhurried, with most of the inhabitants surviving.[60]

- The Irish traditional music group Skara Brae took their name from the settlement. Their only album Skara Brae was released in 1971 and reissued on CD in 1998.

- A stone was unveiled in Skara Brae on 12 April 2008 marking the anniversary of Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin becoming the first man to orbit the Earth in 1961.[61][62]

- The video game The Bard's Tale takes place in a fictionalised version of Skara Brae.

- The video game Starsiege: Tribes features an iconic map named "Scarabrae".

- The video game series Ultima includes the city of Skara Brae, which is on an island to the west of the main continent. It is devoted to the virtue of Spirituality, located next to a moongate and is the home of Shamino the Ranger.[63]

- In Kim Stanley Robinson's 1991 novelette A History of the Twentieth Century, with Illustrations, the main character visits Skara Brae and other Orkney Island neolithic sites as part of a journey he takes to gain perspective on the violent history of the 20th century.[64]

- In the film Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, Jones is shown lecturing to his students about the site,[65]: 6 where he gives the date as "3100 BC".

- Skara Brae is used as the name for a New York Scottish pub in the IDW Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles comic series.[66]

- Skara Brae's ancient sewer system and its use of running water is referenced by Medical Examiner Dr. Donald "Ducky" Mallard in NCIS episode "Murder 2.0" (season 6, episode 6).[67]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ It is one of four UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Scotland, the others being the Old Town and New Town of Edinburgh; New Lanark in South Lanarkshire; and St Kilda in the Western Isles

References

[edit]- ^ "Before Stonehenge". National Geographic. 1 August 2014. Archived from the original on 4 September 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

ten stone structures, The village had a drainage system and even indoor toilets.

- ^ "Skara Brae Sandwick, Scotland". Atlas Obscura. 20 January 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

Amazing and mysterious Neolithic settlement on Scotland's Orkney Islands

- ^ a b c Mark, Joshua J. "Skara Brae". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ "Scotland and the indoor toilet". BBC News. 19 October 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

According to Allan Burnett, historian and author of Invented In Scotland, the Neolithic settlement of Skara Brae in Orkney in fact boasted the world's first indoor toilet.

- ^ Hawkes 1986, p. 262

- ^ "Heart of Neolithic Orkney". UNESCO. 20 January 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

A Management Plan has been prepared by Historic Scotland in consultation with the Partners who share responsibility

- ^ a b c d e Bryson 2010

- ^ "Skara Brae: The Discovery of the Village". Orkneyjar.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ "The House". skaillhouse.co.uk. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ Long, Patricia (17 June 2020). "A Skara Brae Whodunnit". About Orkney. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Katz, Brigit. "Internet Sleuths Were on the Case to Name the Women Archaeologists in These Excavation Photos". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ "Skara Brae women archaeologists who were written out of history". 21 March 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ Darvill 1987, p. 85

- ^ Hedges 1984, p. 107

- ^ a b c d Childe 1931

- ^ Keatinge & Dickson 1979

- ^ Fenton 1978, pp. 206–209

- ^ Childe & Simpson 1952, p. 21

- ^ Childe, V.; Paterson, J.; Thomas, Bryce (30 November 1929). "Provisional Report on the Excavations at Skara Brae, and Finds from the 1927 and 1928 Campaigns. With a Report on Bones". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 63: 225–280. doi:10.9750/PSAS.063.225.280. S2CID 182466398. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ Suddath, Claire (19 November 2009). "A Brief History of Toilets". Time. Time. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ Grant, F.S.A.ScoT., Walter G.; Childe, F.S.A.ScoT., V. G. (1938). "A STONE-AGE SETTLEMENT AT THE BRAES OF RINYO, ROUSAY, ORKNEY. (FIRST REPORT.)". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 72. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ Laing 1974, p. 61

- ^ Ritchie 1995, p. 32

- ^ Childe & Clarke 1983, p. 9

- ^ Beck et al. 1999

- ^ Clarke & Sharples 1985, p. 66

- ^ Buckland & Sadler 2003

- ^ Laing 1974, p. 54

- ^ Childe & Clarke 1983, p. 10

- ^ MacKie 1977

- ^ Ritchie 1981, pp. 51–52

- ^ Castleden 1987, p. 117

- ^ a b Childe & Clarke 1983, p. 6

- ^ Castleden 1987, p. 47

- ^ Hadingham 1975, p. 66

- ^ Ritchie 1995, p. 29

- ^ Clarke & Sharples 1985, p. 58

- ^ "Carved-Stone Balls at Skara Brae". Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ Laing 1982, p. 137

- ^ Piggott 1954, p. 329

- ^ Castleden 1987, p. 253

- ^ Burl 1976, p. 87

- ^ Ritchie 1995, p. 18

- ^ Clarke & Sharples 1985, pp. 78–81

- ^ Ritchie 1981, p. 41

- ^ Ritchie 1995, p. 16

- ^ "Skaill knife" (PDF). Historic Scotland. Retrieved 21 March 2007.

- ^ Burl 1979, p. 144

- ^ Hedges 1984, p. 215

- ^ "The Knap o' Howar, Papay". Orkneyjar. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- ^ "The Barnhouse Settlement". The Ness of Brodgar Excavation. 21 December 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "Barnhouse | Canmore". canmore.org.uk. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ The Heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site Research Agenda (PDF). Vol. Part 2. Historic Scotland. 2005. ISBN 1-904-966-04-7.

- ^ Darvill 1987, p. 105

- ^ "The Heart of Neolithic Orkney". Historic Scotland. Archived from the original on 11 September 2007. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- ^ "Prices and opening times". Historic Environment Scotland. 1 February 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

Some areas/facilities will remain closed for now, we have a phased approach to re-opening while we work to make them safe

- ^ James Cook (2 July 2019). "Orkney world heritage sites threatened by climate change". BBC. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Bramwell 2009, pp. 182–185.

- ^ Fidler 2005

- ^ Bramwell 2009, pp. 185–186.

- ^ "Orkney site marks space race date". BBC News. 12 April 2008. Retrieved 21 April 2008.

- ^ Ross, John (12 April 2008). "Prehistoric honour for first man in space". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Retrieved 21 April 2008.

- ^ "Skara Brae - The Codex of Ultima Wisdom, a wiki for Ultima and Ultima Online". wiki.ultimacodex.com. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ "A History of the Twentieth Century, with Illustrations". Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ Clarke, David (2012). Skara Brae. Historic Scotland. ISBN 978-1-84917-074-1.

- ^ Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Annual (2012). IDW, October 31, 2011.

- ^ "Murder 2.0". NCIS. Season 6. Episode 6. 28 October 2008. CBS.

Bibliography

[edit]- Beck, Roger B.; Black, Linda; Krieger, Larry S.; Naylor, Phillip C.; Shabaka, Dahia Ibo (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- Bramwell, Peter (2009). Pagan Themes in Modern Children's Fiction: Green Man, Shamanism, Earth Mysteries. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-21839-0.

- Bryson, Bill (2010). At home: a short history of private life. London; New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-60827-5.

- Buckland, Paul C.; Sadler, Jon P. (2003). "Insects". In Edwards, Kevin J.; Ralston, Ian B.M. (eds.). Scotland After the Ice Age: Environment, Archaeology and History, 8000 BC – AD 1000. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1736-1.

- Burl, Aubrey (1976). The Stone Circles of the British Isles. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-01972-6.

- Burl, Aubrey (1979). Prehistoric Avebury. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02368-5.

- Castleden, Rodney (1987). The Stonehenge People. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. ISBN 0-7102-0968-1.

- Childe, V. Gordon (1931). Skara Brae, a Pictish Village in Orkney. meeting held in London: monograph of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland.

- Childe, V. Gordon; Simpson, W. Douglas (1952). Illustrated History of Ancient Monuments: Vol. VI Scotland. Edinburgh: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.