King Kong (1933 film): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m Remove template per TFD outcome |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|1933 film directed by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack}} |

|||

{{Infobox Film | |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=February 2021}} |

|||

name = King Kong | |

|||

{{Infobox film |

|||

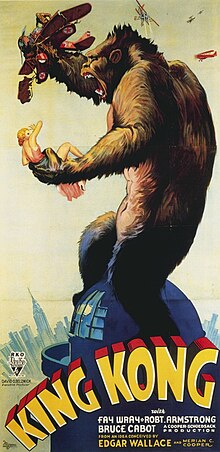

image = kingkongposter.jpg| |

|||

| name = King Kong |

|||

| image = Kingkongposter.jpg |

|||

director = [[Merian C. Cooper]]<br />[[Ernest B. Schoedsack]] | |

|||

| caption = Theatrical release poster |

|||

writer = [[Merian C. Cooper]] (story)<br />[[Edgar Wallace]] (story)<br>[[James Ashmore Creelman]] (screenplay)<br>Ruth Rose (screenplay)| |

|||

| director = {{Plain list| |

|||

starring = [[Fay Wray]],<br />[[Robert Armstrong (actor)|Robert Armstrong]],<br />[[Bruce Cabot]] | |

|||

* [[Merian C. Cooper]] |

|||

producer = [[Merian C. Cooper]]<br />[[Ernest B. Schoedsack]]<br />[[David O. Selznick]] (executive producer)| |

|||

* [[Ernest B. Schoedsack]] |

|||

music = [[Max Steiner]] | |

|||

cinematography = [[Eddie Linden]]<br />[[J.O. Taylor]]<br />[[Vernon Walker]] | |

|||

distributor = [[RKO Radio Pictures, Inc.]] | |

|||

released = [[March 2]], [[1933 in film|1933]] (U.S. release)| |

|||

runtime = 104 minutes | |

|||

language = [[English language|English]] | |

|||

amg_id = 1:27391| |

|||

followed_by = ''[[The Son of Kong]]'' |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

| producer = {{Plain list| |

|||

:''This is about the original movie and novel. For other uses and adaptations see [[King Kong]]'' |

|||

* Merian C. Cooper |

|||

* Ernest B. Schoedsack |

|||

}} |

|||

| screenplay = {{Plain list| |

|||

* [[James Ashmore Creelman|James Creelman]] |

|||

* [[Ruth Rose]] |

|||

}} |

|||

| story = {{Plain list| |

|||

* [[Edgar Wallace]] |

|||

* Merian C. Cooper<ref name=afi>{{AFI film|4005|King Kong}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

| starring = {{Plain list| |

|||

* [[Fay Wray]] |

|||

* [[Robert Armstrong (actor)|Robert Armstrong]] |

|||

* [[Bruce Cabot]]<!--billing per poster--> |

|||

}} |

|||

| music = [[Max Steiner]] |

|||

| cinematography = {{Plain list| |

|||

* Eddie Linden |

|||

* [[Vernon Walker]] |

|||

* [[J.O. Taylor]] |

|||

}} |

|||

| editing = Ted Cheesman |

|||

| distributor = [[RKO Pictures|RKO Radio Pictures]] |

|||

| released = {{Film date|1933|3|2|[[New York City]]|1933|4|7|United States}} |

|||

| runtime = 100 minutes |

|||

| country = United States |

|||

| language = English |

|||

| budget = $672,254.75<ref name="rko">* {{cite journal |first=Richard |last=Jewel |title=RKO Film Grosses: 1931–1951 |journal=Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television |volume=14 |issue=1 |year=1994 |page=39 |quote=1933 release: $1,856,000; 1938 release: $306,000; 1944 release: $685,000}} |

|||

* {{cite web |title=King Kong (1933) – Notes |publisher=[[Turner Classic Movies]] |url=http://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/2690/King-Kong/notes.html |access-date=January 7, 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191216073610/http://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/2690/King-Kong/notes.html |archive-date=December 16, 2019 |quote=1952 release: $2,500,000; budget: $672,254.75}}</ref> |

|||

| gross = $5.3 million<ref name="rko"/><br>(equivalent to ${{Inflation|US|5.3|1933|r=2}} million in {{Inflation/year|US}}){{inflation-fn|US}} |

|||

}} |

|||

'''''King Kong''''' is a 1933 American [[Pre-Code Hollywood|pre-Code]] [[adventure film|adventure]] [[romantic film|romance]] [[monster film]]<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.dreadcentral.com/news/387864/horror-history-king-kong-1933-is-now-88-years-old/|title=Horror History: KING KONG (1933) Is Now 88 Years Old|last=Sprague|first=Mike|work=[[Dread Central]]|date=April 7, 2021|access-date=September 9, 2021|archive-date=September 9, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210909061650/https://www.dreadcentral.com/news/387864/horror-history-king-kong-1933-is-now-88-years-old/|url-status=live}}</ref> directed and produced by [[Merian C. Cooper]] and [[Ernest B. Schoedsack]], with special effects by [[Willis H. O'Brien]] and music by [[Max Steiner]]. Produced and distributed by [[RKO Pictures|RKO Radio Pictures]], it is the first film in the [[King Kong (franchise)|''King Kong'' franchise]]. The film stars [[Fay Wray]], [[Robert Armstrong (actor)|Robert Armstrong]], and [[Bruce Cabot]]. The film follows a giant ape dubbed [[King Kong|Kong]] who is offered a beautiful young woman as a sacrifice. |

|||

''King Kong'' opened in New York City on March 2, 1933, to rave reviews, with praise for its stop-motion animation and score. In 1991, it was deemed "culturally, historically and aesthetically significant" by the [[Library of Congress]] and selected for preservation in the [[National Film Registry]].<ref>Daniel Eagan, (2010). ''America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry.'' The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc, New York, NY p.22</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Kehr |first=Dave |title=U.S. FILM REGISTRY ADDS 25 SIGNIFICANT MOVIES |language=en-US |website=Chicago Tribune |date=September 26, 1991 |url=https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1991-09-26-9103130465-story.html |access-date=July 20, 2020 |archive-date=June 17, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200617031520/https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1991-09-26-9103130465-story.html |url-status=live}}</ref> It is ranked by [[Rotten Tomatoes]] as the greatest [[horror film]] of all time<ref>{{cite web |title=Best Horror Movies – King Kong (1933) |website=[[Rotten Tomatoes]] |url=https://www.rottentomatoes.com/guides/best_horror_movies/1011615-king_kong/ |access-date=July 3, 2018 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100401203419/http://www.rottentomatoes.com/guides/best_horror_movies/1011615-king_kong/ |archive-date=April 1, 2010}}</ref> and the fifty-sixth [[List of films considered the best|greatest film of all time]].<ref>{{cite web |website=[[Rotten Tomatoes]] |url=https://www.rottentomatoes.com/top/bestofrt/ |title=Top 100 Movies of All Time – Rotten Tomatoes |access-date=October 14, 2016 |archive-date=February 1, 2018 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20180201110157/https://www.rottentomatoes.com/top/bestofrt/ |url-status=live}}</ref> A sequel, ''[[Son of Kong]],'' was made the same year as the original film, and [[King Kong (franchise)|several more films]] have been made, including two remakes in [[King Kong (1976 film)|1976]] and [[King Kong (2005 film)|2005]]. |

|||

'''''King Kong''''' is a landmark [[1933 in film|1933]] [[Hollywood]] [[Horror film|horror]]-[[adventure film]] in [[black-and-white]] about a gigantic prehistoric [[gorilla]] named [[King Kong|Kong]]. |

|||

==Plot== |

|||

The film was made by [[RKO]] and was written originally for the screen by [[Edgar Wallace]], [[Ruth Rose]] and [[James Ashmore Creelman]] from a concept by [[Merian C. Cooper]]. A novelization of the screenplay actually appeared before the film, in 1932 adapted by [[Delos Lovelace]], and contains descriptions of scenes not in the movie. |

|||

<!-- Please read this! Plot summaries for films on Wikipedia are recommended to be between 400-700 words. All edits es/genera names of the creatures are given in the authoritative book "King Kong: The History of a Movie Icon from Fay Wray to Peter Jackson" by Ray Morton. Please do not change the names. Thank you --> |

|||

In [[New York Harbor]], filmmaker [[Carl Denham]], known for wildlife films in remote exotic locations, is chartering Captain Englehorn's ship, the ''Venture,'' for his new project. However, he is unable to secure an actress for a female role he has been reluctant to disclose. In the streets of [[New York City]], he finds Ann Darrow and promises her "the thrill of a lifetime". The ''Venture'' sets off, during which Denham reveals that their destination is in fact [[Skull Island (King Kong)|an uncharted island with a mountain the shape of a skull]]. He alludes to a mysterious entity named ''Kong,'' rumored to dwell on the island. The crew arrive and anchor offshore. They encounter a native village, separated from the rest of the island by an enormous stone wall with a large wooden gate. They witness a group of natives preparing to sacrifice a young woman termed the "bride of Kong". The intruders are spotted and the native chief stops the ceremony. When he sees the blonde-haired Ann, he offers to trade six of his tribal women for the "golden woman". They refuse him and return to the ship. |

|||

That night, after the ship's first mate, [[Jack Driscoll (character)|Jack Driscoll]], admits his love for Ann, the natives kidnap Ann from the ship and take her through the gate and onto an altar, where she is offered to [[King Kong|Kong]], who is revealed to be a giant [[gorilla]]. Kong carries a terrified Ann away as Denham, Jack and some volunteers give chase. The men encounter living [[dinosaur]]s; they manage to kill a charging ''[[Stegosaurus]]'', but are attacked by an aggressive ''[[Brontosaurus]]'' and eventually Kong himself, leaving Jack and Denham as the only survivors. After Kong slays a ''[[Tyrannosaurus]]'' to save Ann, Jack continues to follow them while Denham returns to the village. Upon arriving in Kong's mountain lair, Ann is menaced by a serpent-like ''[[Elasmosaurus]]'', which Kong also kills. When a ''[[Pteranodon]]'' tries to fly away with Ann, and is killed by Kong, Jack saves her and they climb down a vine dangling from a cliff ledge. When Kong starts pulling them back up, the two drop into the water below; they flee through the jungle back to the village, where Denham, Englehorn, and the surviving crewmen await. Kong, following, breaks open the gate and relentlessly rampages through the village. Onshore, Denham, determined to bring Kong back alive, renders him unconscious with a gas bomb. |

|||

The film was directed by [[Merian C. Cooper]] and [[Ernest B. Schoedsack]] and starred [[Bruce Cabot]] and [[Robert Armstrong (actor)|Robert Armstrong]]. It is notable for [[Willis OBrien|Willis O'Brien]]'s ground breaking [[stop-motion]] animation work, [[Max Steiner]]'s musical score, and actress [[Fay Wray]]'s performance as the ape's improbable love interest. ''King Kong'' premiered in New York City on [[March 2]], [[1933]]. |

|||

Shackled in chains, Kong is taken to New York City and presented to a [[Broadway theatre]] audience as "Kong, the [[Eighth Wonder of the World]]!" Ann and Jack join him on stage, surrounded by press photographers. The ensuing flash photography causes Kong to break loose as the audience flees in terror. Ann is whisked away to a hotel room on a high floor, but Kong, scaling the building, reclaims her. He makes his way through the city with Ann in his grasp, wrecking a crowded elevated train and begins climbing the [[Empire State Building]]. Jack suggests to police for airplanes to shoot Kong off the building, without hitting Ann. Four [[biplanes]] take off; seeing the planes arrive, Jack becomes agitated for Ann's safety and rushes inside with Denham. At the top, Kong is shot at by the planes, as he begins swatting at them. Kong destroys one, but is wounded by the gunfire. After he gazes at Ann, he is shot more, loses his strength and plummets to the streets below; Jack reunites with Ann. Denham heads back down and is allowed through a crowd surrounding Kong's corpse in the street. When a policeman remarks that the planes got him, Denham states, "Oh, no, it wasn't the airplanes. It was Beauty killed the Beast." |

|||

==Influences== |

|||

''King Kong'' was influenced by the "[[Lost World (genre)|Lost World]]" literary genre, in particular [[Edgar Rice Burroughs]]' ''[[The Land That Time Forgot (novel)|The Land That Time Forgot]]'' (1918) and [[Arthur Conan Doyle]]'s ''[[The Lost World (Arthur Conan Doyle)|The Lost World]]'' (1912), which depicted remote and isolated jungles teeming with dinosaur life. |

|||

==Cast== |

|||

In the early 20th century few zoos had monkey exhibits so there was popular demand to see them on film. [[William S. Campbell]] specialized in monkey-themed films with ''Monkey Stuff'' and ''Jazz Monkey'' in 1919, and ''Prohibition Monkey'' in 1920. Kong producer Schoedsack had earlier monkey experience directing ''Chang'' in 1927 (with Cooper) and ''Rango'' in 1931, both of which prominently featured monkeys in real jungle settings. |

|||

* [[Fay Wray]] as Ann Darrow |

|||

* [[Robert Armstrong (actor)|Robert Armstrong]] as [[Carl Denham]] |

|||

* [[Bruce Cabot]] as [[Jack Driscoll (character)|John "Jack" Driscoll]] |

|||

* [[Frank Reicher]] as Captain Englehorn |

|||

* [[Sam Hardy (actor)|Sam Hardy]] as Charles Weston |

|||

* [[Victor Wong (actor born 1906)|Victor Wong]] as Charlie |

|||

* [[James Flavin]] as Second Mate Briggs |

|||

* [[Etta McDaniel]] as The Native Mother |

|||

* [[Everett Brown]] as The Native In An [[Ape]] Costume |

|||

* [[Noble Johnson]] as The Native Chief |

|||

* [[Steve Clemente]] as The Witch Doctor |

|||

==Production== |

|||

Capitalizing on this trend "Congo Pictures" released the hoax documentary ''[[Ingagi]]'' in 1930, advertising the film as "an authentic incontestable celluloid document showing the sacrifice of a living woman to mammoth gorillas!". ''Ingagi'' was an unabashed black [[exploitation film]], immediately running afoul of the Hollywood code of ethics, as it implicitly depicted black women having sex with gorillas, and baby offspring that looked more ape than human.<ref>Gerald Peary, [http://www.geraldpeary.com/essays/jkl/kingkong-1.html 'Missing Links: The Jungle Origins of King Kong' (1976)], repr. ''Gerald Peary: Film Reviews, Interviews, Essays and Sundry Miscellany'', 2004</ref> The film was an immediate hit, and by some estimates it was one of the highest grossing movies of the 1930s at over $4 million. Although producer Merian C. Cooper never listed ''Ingagi'' among his influences for ''King Kong,'' it's long been held that RKO green-lighted ''Kong'' because of the bottom-line example of ''Ingagi'' and the formula that "gorillas plus sexy women in peril equals enormous profits". <ref>{{cite news | first=Andrew | last=Erish | title=Illegitimate Dad of King Kong | date=January 8, 2006| publisher=Los Angeles Times | url=http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/latimes/access/959395991.html?dids=959395991:959395991&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&type=current&date=Jan+8%2C+2006&author=Andrew+Erish&pub=Los+Angeles+Times&edition=&startpage=E.6&desc=Movies }}</ref> |

|||

{{Expand section|date=February 2023}} |

|||

===Crew=== |

|||

The special effects were influenced by the [[shelved|unfinished]] 1931 film ''[[Creation (1931 film)|Creation]]''. |

|||

{{cast listing| |

|||

* [[Merian C. Cooper]] – co-director, producer |

|||

* [[Ernest B. Schoedsack]] – co-director, producer |

|||

* [[David O. Selznick]] – executive producer |

|||

* [[Willis H. O'Brien]] – chief technician |

|||

* [[Archie Marshek]] – production assistant |

|||

* [[Harry Redmond Jr.]] – special effects |

|||

* [[Murray Spivack]] – sound effects |

|||

* [[Van Nest Polglase]] – supervising art director |

|||

* [[Clem Portman]] – sound recording mixer |

|||

* [[Mel Berns]] – chief makeup supervisor |

|||

}} |

|||

Personnel taken from ''King Kong: The History of a Movie Icon From Fay Wray to Peter Jackson.''{{sfn|Morton|2005|p=13}} |

|||

== |

===Development=== |

||

{{Further|King Kong#Conception and creation}} |

|||

{{spoiler}} |

|||

[[File:T. rex old posture.jpg|left|thumb|[[Charles R. Knight]]'s ''[[Tyrannosaurus]]'' in the [[American Museum of Natural History]], on which the large [[Theropoda|theropod]] of the film was based<ref name=Goldner>Orville Goldner, George E Turner (1975). ''Making of King Kong: The Story Behind a Film Classic.'' {{ISBN|0498015106}}. See also ''Spawn of Skull Island'' (2002). {{ISBN|1887664459}}</ref>]] |

|||

The film starts off in New York City during the depths of the [[Great Depression]] (early 1930s). [[Carl Denham]], a film director famous for shooting 'animal pictures' in remote and exotic locations is unable to find an actress to star in his newest project and so is forced to wander the streets searching for a suitable woman. He chances upon a poor girl, [[Ann Darrow]], who has been caught trying to steal an apple by a greengrocer. Saying "Here's a buck, now [[Scram (disambiguation)|scram]]" to the proprietor, Denham makes Ann's acquaintance and when she, through extreme hunger, faints into his arms (at which moment her great beauty strikes him) he buys her a sandwich and cup of coffee and offers her a job starring in his new film. Although Ann is apprehensive and seems to question Denham's exact intentions, she has nothing to lose and, after assurances that Denham is "on the level", agrees. They set sail the following morning on the freighter ''Venture'', getting out of New York harbor just ahead of the authorities. |

|||

''King Kong'' producer [[Ernest B. Schoedsack]] had earlier [[monkey]] experience directing ''[[Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness]]'' (1927), also with [[Merian C. Cooper]], and ''[[Rango (1931 film)|Rango]]'' (1931), both of which prominently featured monkeys in authentic jungle settings. Capitalizing on this trend, Congo Pictures released the [[Mockumentary|hoax documentary]] ''[[Ingagi]]'' (1930), advertising the film as "an authentic incontestable celluloid document showing the sacrifice of a living woman to mammoth gorillas." ''Ingagi'' is now often recognized as a racial [[exploitation film]] as it implicitly depicted black women having sex with gorillas, and baby offspring that looked more ape than human.<ref>Gerald Peary, [http://www.geraldpeary.com/essays/jkl/kingkong-1.html 'Missing Links: The Jungle Origins of King Kong' (1976)] {{Webarchive|url=https://archive.today/20130103102653/http://www.geraldpeary.com/essays/jkl/kingkong-1.html |date=January 3, 2013}} ''Gerald Peary: Film Reviews, Interviews, Essays, and Sundry Miscellany,'' 2004.</ref> The film was an immediate hit, and by some estimates, it was one of the highest-grossing films of the 1930s at over $4 million. Although Cooper never listed ''Ingagi'' among his influences for ''King Kong,'' it has long been held that RKO greenlighted ''Kong'' because of the bottom-line example of ''Ingagi'' and the formula that "gorillas plus sexy women in peril equals enormous profits."<ref>{{cite news | first=Andrew | last=Erish | title=Illegitimate Dad of King Kong | date=January 8, 2006 | newspaper=Los Angeles Times | url=https://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/latimes/access/959395991.html?dids=959395991:959395991&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&type=current&date=Jan+8%2C+2006&author=Andrew+Erish&pub=Los+Angeles+Times&edition=&startpage=E.6&desc=Movies | access-date=July 6, 2017 | archive-date=March 14, 2013 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130314080024/http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/latimes/access/959395991.html?dids=959395991:959395991&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&type=current&date=Jan+8%2C+2006&author=Andrew+Erish&pub=Los+Angeles+Times&edition=&startpage=E.6&desc=Movies | url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

Whilst on the ship with its all-male crew, first mate [[Jack Driscoll]] complains Ann is constantly getting in the way. Denham, after maintaining secrecy for much of the trip, tells the ''Venture'''s captain, [[Captain Englehorn|Englehorn]], they're searching for an island uncharted on any normal map. He says that two years earlier a skipper gave him the one map on which it ''is'' charted, having received it from a native of Kong's island who had been swept out to sea. Denham then asks Englehorn and Driscoll, "Have you ever heard of... Kong?", describing it as something monstrous, a legend of vague fear. The two exchange looks making it clear they are wondering if Denham is of completely sound mind. |

|||

===Special effects=== |

|||

Despite his declarations that women have no place on board ships, Jack is obviously becoming attracted to Ann. Denham takes note and informs Driscoll he has enough troubles without the complications of a seagoing love affair. "Love affair! You think I'm gonna fall for any dame?", asks Driscoll, who then reminds Denham of his toughness in past adventures. Denham replies "...you're a pretty tough guy, but if Beauty gets you...". Pressed for elaboration, Denham hints at the movie's major theme by saying, "It's the idea of my picture. The Beast was a tough guy too. He could lick the world. But when he saw Beauty, she got him. He went soft. He forgot his wisdom and the little fellas licked him. Think it over, Jack." |

|||

{{more citations needed section|date=November 2016}} |

|||

[[File:King Kong vs Tyrannosaurus.jpg|thumb|Promotional image featuring Kong battling the ''Tyrannosaurus'', though Cooper emphasized in an interview with film historian Rudy Behlmer that it was an Allosaurus]] |

|||

''King Kong'' is well known for its groundbreaking use of special effects, such as [[Stop motion|stop-motion animation]], [[matte painting]], [[rear projection]] and [[miniature effect|miniatures]], all of which were conceived decades before the digital age.<ref>Wasko, Janet. (2003). ''How Hollywood Works.'' California: SAGE Publications Ltd. p.53.</ref> |

|||

The numerous prehistoric creatures inhabiting [[Skull Island (King Kong)|the Island]] were brought to life through the use of stop-motion animation by [[Willis H. O'Brien]] and his assistant animator, Buzz Gibson.<ref>Bordwell, David, Thompson, Kristin, Smith, Jeff. (2017). ''Film Art: An Introduction.'' New York: McGraw-Hill. p.388.</ref> The stop-motion animation scenes were painstaking and difficult to achieve and complete. The special effects crew realized that they could not stop because it would make the movements of the creatures seem inconsistent and the lighting would not have the same intensity over the many days it took to fully animate a finished sequence. A device called the surface gauge was used in order to keep track of the stop-motion animation performance. The iconic fight between Kong and the ''Tyrannosaurus'' took seven weeks to be completed. |

|||

As the ''Venture'' moves through the fog surrounding Kong's island the crew hear drums in the distance. They finally arrive at the island's shore and see the native village, which is located on a peninsula, cut off from the bulk of the island by an enormous and ancient wall. Going ashore, the crew encounters the natives, who are about to hand over a girl to Kong as a ritual sacrifice. Although Denham, Englehorn, Jack, Ann and a number of crewmen are hiding behind foliage, the native chief spots them and approaches threateningly. Captain Englehorn has already noticed that the natives speak a language similar to the [[Nias]] islanders, a tongue he has some familiarity with. At Denham's urging, the Captain makes friendly overtures to the chief and to the leading "medicine man". When these two get a clear look at Ann the chief begins speaking and gesticulating with great energy. According to Englehorn they are saying "Look at the golden woman!". In keeping with the coarseness of the time, Denham quips "Yeah, blondes are kind of scarce around here." (Oddly, the islanders are plainly of sub-Saharan African stock despite the island's location in [[Indonesia]]). The chief proposes to swap six native women for Ann, an offer Denham delicately declines as he and his party edge away from the scene, assuring the chief through Englehorn that they will "be back tomorrow to make friends". |

|||

The backdrop of the island seen when the Venture crew first arrives was painted on glass by matte painters Henry Hillinck, Mario Larrinaga, and Byron L. Crabbe. The scene was then composited with separate bird elements and rear-projected behind the ship and the actors. The background of the scenes in the jungle (a miniature set) was also painted on several layers of glass to convey the illusion of deep and dense jungle foliage.<ref>Harryhausen, Ray. (1983). Animating the Ape. In: Lloyd, Ann. (ed.) ''Movies of the Thirties.'' UK: Orbis Publishing Ltd. p.173.</ref> |

|||

Back on the ''Venture'', Jack and Ann openly express their love for one another. When Jack is called to the captain's quarters, Ann is captured by a stealthy contingent of natives in an outrigger canoe, held captive, and handed over to Kong in a ceremony; when Kong emerges from the jungle, he is revealed to be a giant gorilla. The Venture crew returns to the village and takes control of the wall from the natives; a portion of the crew then goes after Kong, encountering an aggressive ''[[stegosaurus]]'' and a carnivorous ''[[Apatosaurus|brontosaurus]]'' (in real life, both species were relatively inoffensive [[herbivores]]). |

|||

The most difficult task for the special effects crew to achieve was to make live-action footage interact with separately filmed stop-motion animation, making the interaction between the humans and the creatures of the island seem believable. The most simple of these effects were accomplished by exposing part of the frame, then running the same piece of the film through the camera again by exposing the other part of the frame with a different image. The most complex shots, where the live-action actors interacted with the stop-motion animation, were achieved via two different techniques, the [[Bipack|Dunning process]] and the [[Williams process]], in order to produce the effect of a traveling matte.<ref>Corrigan, Timothy, White, Patricia. (2015). ''The Film Experience.'' New York: Bedford/St. Martin's. pp.120–121.</ref> The Dunning process, invented by cinematographer Carroll H. Dunning, employed the use of blue and yellow lights that were filtered and photographed into the black-and-white film. [[Bipack|Bi-packing]] of the camera was used for these types of effects. With it, the special effects crew could combine two strips of different films at the same time, creating the final composite shot in the camera.<ref>Harryhausen 172–173</ref> It was used in the climactic scene where one of the planes attacking Kong crashes from the top of the Empire State Building, and in the scene where natives are running through the foreground, while Kong is fighting other natives at the wall.{{Citation needed|date=February 2023}} |

|||

[[Image:Kong vs T-Rex.jpg|lright|240px|thumb|Kong wrestles a ''[[Tyrannosaurus rex]]'' to protect Ann Darrow in a famous scene from the original [[King Kong]] film. Of all the scenes in the movie, this was the most difficult and time consuming to animate.]] |

|||

Up ahead in the jungle, Kong places Ann in the cleft of a dead tree. He then doubles back and confronts the pursuing crewmembers while they are crossing a ravine by way of an enormous moss covered log and shakes them off, killing all except for Driscoll and Denham. Meanwhile, a ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' is about to attack Ann; Kong rushes back and a long struggle between the two titans ends when Kong snaps the ''[[T. rex]]'s'' jaw, including the muscles attaching it to the skull. He takes Ann up to his mountaintop cave. During this time, Kong inspects his blonde prize and begins to caress her, and slowly tears off pieces of her dress. Just as he strips Ann down to her [[slip]], Jack interrupts the proceedings by knocking over a boulder. The gorilla leaves her alone and investigates the cause of the noise. Then, a [[pterodactyl]] comes swooping from the sky and clutches Ann in its talons. Another fight ensues. While Kong is thus distracted, Jack rescues Ann and takes her back to the wall. Denham declares that they can make a fortune if they can get Kong back to New York; since they've got something the gorilla wants, the men can lure him. But Jack insists Ann is something Kong won't get again. Kong then breaks through the large door in the wall and rampages through the native village, killing many of the inhabitants. Denham hurls a gas bomb, knocking Kong unconscious, whereupon he exults in the opportunity to take the giant back to New York as an exhibit: "He's always been King of his world. But we'll teach him fear! We're millionaires, boys! I'll share it with all of you. Why, in a few months, it'll be up in lights on Broadway: 'Kong — the Eighth Wonder of the World!'" |

|||

On the other hand, the Williams process, invented by cinematographer [[Frank D. Williams (cinematographer)|Frank D. Williams]], did not require a system of colored lights and could be used for wider shots. It was used in the scene where Kong is shaking the sailors off the log, as well as the scene where Kong pushes the gates open. The Williams process did not use [[bipack]]ing, but rather an [[optical printer]], the first such device that synchronized a projector with a camera, so that several strips of film could be combined into a single composited image. Through the use of the optical printer, the special effects crew could film the foreground, the stop-motion animation, the live-action footage, and the background, and combine all of those elements into one single shot, eliminating the need to create the effects in the camera.<ref>Dyson, Jeremy. (1997). ''Bright Darkness: The Lost Art of the Supernatural Horror Film.'' London: Cassell. p.38.</ref> |

|||

The next scene begins with those very words in lights on a theater marquee. Along with hundreds of curious New Yorkers, Denham, Driscoll and Ann are in evening wear for the gala event. As the curtain lifts we see a manacled, much subdued Kong displayed on the stage. Yet his sheer size and power sets many in the audience on edge, including an elderly gentleman who must be restrained back into his seat. Denham assures them they are safe, "Don't be alarmed ladies and gentlemen. Those chains are made of chrome steel". All goes well until photographers, using the blinding flashbulbs of the era, begin snapping shots of Ann and Jack, who are by now engaged to marry. Under the impression that the flashbulbs are attacking Ann, Kong breaks his chains and escapes from the theater. He rampages through the city streets, destroying an [[elevated train]] and killing a number of citizens. |

|||

[[File:KingKong001C.png|thumb|Colored publicity shot combining live actors with [[stop motion animation]]]] Another technique that was used in combining live actors and stop-motion animation was rear-screen projection. The actor would have a translucent screen behind him where a projector would project footage onto the back of the translucent screen.<ref name="Harryhausen 173">Harryhausen 173</ref> The translucent screen was developed by Sidney Saunders and [[Fred Jackman]], who received a Special Achievement Oscar. It was used in the scene where Kong and the ''Tyrannosaurus'' fight while Ann watches from the branches of a nearby tree. The stop-motion animation was filmed first. Fay Wray then spent a twenty-two-hour period sitting in a fake tree acting out her observation of the battle, which was projected onto the translucent screen while the camera filmed her witnessing the projected stop-motion battle. She was sore for days after the shoot. The same process was also used for the scene where sailors from the ''Venture'' kill a [[Stegosaurus]].{{Citation needed|date=February 2023}} |

|||

He then manages to find and abduct Ann from a hotel room and carries her up the [[Empire State Building]]. By this time, the authorities have summoned four Navy [[biplanes]] to shoot Kong down. The ape gently sets Ann down on the observation deck and climbs atop the [[dirigible]] mooring mast (which was later replaced with an antenna), trying to fight off the planes. Despite being able to destroy one of them, Kong is no match for modern technology; gunned down, he crashes to his death in the street below. Denham rushes up, and a New York City cop remarks, "Well Mr. Denham, the airplanes got him," whereupon Denham muses, "Oh, no, it wasn't the airplanes; it was beauty killed the beast." |

|||

{{endspoiler}} |

|||

O'Brien and his special effects crew also devised a way to use rear projection in miniature sets. A tiny screen was built into the miniature onto which live-action footage would then be projected.<ref name=" Harryhausen 173"/> A fan was used to prevent the footage that was projected from melting or catching fire. This miniature rear projection was used in the scene where Kong is trying to grab Driscoll, who is hiding in a cave. The scene where Kong puts Ann at the top of a tree switched from a puppet in Kong's hand to projected footage of Ann sitting.{{Citation needed|date=February 2023}} |

|||

== Significance == |

|||

''King Kong'' was the first important Hollywood film to have a thematic music score, rather than background music, courtesy of a promising young composer, [[Max Steiner]]. |

|||

The scene where Kong fights the [[Tanystropheus]] in his lair was likely the most significant special effects achievement of the film, due to the way in which all of the elements in the sequence work together at the same time. The scene was accomplished through the combination of a miniature set, stop-motion animation, background matte paintings, real water, foreground rocks with bubbling mud, smoke, and two miniature rear screen projections of Driscoll and Ann.{{Citation needed|date=February 2023}} |

|||

It was also the first hit film to offer a life-like animated central character in any form. Much of what is done today with CGI animation has its conceptual roots in the [[stop motion]] model animation that was pioneered in ''Kong''. Willis O'Brien, credited as "Chief Technician" on the film, has been lauded by later generations of film special effects artists as an outstanding original genius of founder status. |

|||

Over the years, some media reports have alleged that in certain scenes Kong was played by an actor wearing a [[gorilla suit]].<ref>{{cite news|title=Charlie Gemora, 58, had King Kong role|url=https://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9C07E2D71239EE32A25753C2A96E9C946091D6CF|work=[[The New York Times]]|date=August 20, 1961|access-date=February 10, 2017|archive-date=March 18, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220318035303/https://www.nytimes.com/1961/08/20/archives/charlie-gemora-58-had-king-kong-role.html|url-status=live}}{{subscription required}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last1=Greene|first1=Bob|author-link1=Bob Greene|title=Saying so long to Mr. Kong|url=http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1990/11/27/page/113/article/saying-so-long-to-mr-kong|work=[[Chicago Tribune]]|date=November 27, 1990|access-date=December 24, 2016|archive-date=December 21, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161221232727/http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1990/11/27/page/113/article/saying-so-long-to-mr-kong/|url-status=live}}</ref> However, film historians have generally agreed that all scenes involving Kong were achieved with animated models,<ref>{{cite book |last1=Glut |first1=Donald F. |url=https://archive.org/details/jurassicclassics00dona |title=Jurassic Classics: A Collection of Saurian Essays and Mesozoic Musings |publisher=McFarland |year=2001 |isbn=9780786462469 |location=Jefferson, NC |page=[https://archive.org/details/jurassicclassics00dona/page/192 192] |quote=Over the years, various actors have claimed to have played Kong in this [Empire State Building] scene, including a virtually unknown performer named [[Carmen Nigro]] (AKA Ken Roady), and also noted gorilla impersonator [[Charles Gemora]]... In Nigro's case, the claim seems to have been simply fraudulent, in Gemora's, the inaccurate claim was apparently based on the actor's memory of playing a giant ape in a never-completed ''King Kong'' spoof entitled ''The Lost Island.'' |author-link1=Donald F. Glut |url-access=registration}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Glut |first1=Donald F. |title=King Kong Cometh! |date=2005 |publisher=Plexus |isbn=9780859653626 |editor1-last=Woods |editor1-first=Paul A. |location=London |page=64 |chapter=His Majesty, King Kong - IV |quote=Cooper denied any performance by an actor in a gorilla costume in King Kong... Perhaps a human actor was used in a bit of forgotten test footage before the film went into production, but thus far the matter remains a mystery. |author-link1=Donald F. Glut}}</ref> except for the "closeups" of Kong's face and upper body which are dispersed throughout the film. These shots were accomplished by filming a "full size" mechanical model of Kong's head and shoulders. Operators could manipulate the eyes and mouth to simulate a living monster. These shots can be identified immediately in two ways: the action is very smooth (not stop-motion jittery) and the footage is extremely sharp and clear because of the size of the subject being photographed. |

|||

==Censorship== |

|||

The first version of the film was apparently screened to a sample audience in [[San Bernardino, California]], in late January, 1933, before the official release. The film at that time contained a scene in which Kong shakes four men off a log in to a crevasse where they are eaten alive by a giant spider, a giant crab, a giant lizard, and an octopoid. The spider pit scene caused members of the audiences to scream and some left the theater. After the preview, the film's producer, [[Merian C. Cooper]], cut the scene. However, a memo written by Merian C. Cooper, recently revealed on a ''King Kong'' documentary, indicates that the scene was cut because it slowed the film down, not because it was too horrific. According to King Kong cometh, the scene did not get past the Motion Picture Board of Censors and that audiences only claim to have seen the sequence. On the 2005 DVD, it is not mentioned about the sequence being in the preview screening. Stills from the scene exist, but the scenes themselves remain unfound to this day. It is mentioned on the 2005 DVD by Doug Turner, that Merian C. Cooper, the director, liked to burn his deleted scenes so many have presumed that the Lost Spider Pit Sequence unfortunately met this fate[http://www.retrocrush.com/archive2005/kong/]. Director [[Peter Jackson]] and a crew of special effects technicians, mainly from [[Weta Workshop]], created an imaginative reconstruction for the 2005 DVD release of the film (the scene was not spliced into the film but is intercut with original footage to show where it would have occurred, and is part of the DVD extras). The scene is recreated in the 2005 film, with most men surviving the initial fall, but all except Jack, Carl and Jimmy are killed after a long battle. |

|||

===Post-production=== |

|||

''King Kong'' was released four times between 1933 and 1952. All of the releases saw the film cut for censorship purposes. Scenes of Kong eating people or stepping on them were cut, as was his peeling off of Ann's dress. Many of these cuts were restored for the 1976 theatrical release after an uncensored print was discovered in the [[United Kingdom]] (which was not covered by the American [[Production Code]]). |

|||

[[Murray Spivack]] provided the sound effects for the film. Kong's roar was created by mixing the recorded vocals of captive [[lion]]s and [[tiger]]s, subsequently played backward slowly. Spivak himself provided Kong's "love grunts" by grunting into a megaphone and playing it at a slow speed. For the huge ape's footsteps, Spivak stomped across a gravel-filled box with plungers wrapped in foam attached to his own feet, while the sounds of his chest beats were recorded by Spivak hitting his assistant (who had a microphone held to his back) on the chest with a drumstick. Spivak created the hisses and croaks of the dinosaurs with an [[air compressor]] for the former and his own vocals for the latter. The vocalizations of the Tyrannosaurus were additionally mixed in with [[cougar|puma]] growls while bird squawks were used for the Pteranodon. Spivak also provided the numerous screams of the various sailors. Fay Wray herself provided all of her character's screams in a single recording session.{{sfn|Morton|2005|pp=75–76}}<ref>{{cite book|author=Von Gunden, Kenneth|year=2001|title=Flights of Fancy: The Great Fantasy Films|publisher=McFarland|page=117|isbn=9780786412143}}</ref> |

|||

The score was unlike any that came before and marked a significant change in the history of film music. King Kong's score was the first feature-length musical score written for an American "talkie" film, the first major Hollywood film to have a thematic score rather than background music, the first to mark the use of a 46-piece orchestra and the first to be recorded on three separate tracks (sound effects, dialogue, and music). Steiner used a number of new film scoring techniques, such as drawing upon opera conventions for his use of [[leitmotif]]s.<ref name="HelveringIowa2007">{{cite book|last1=Helvering|first1=David Allen|author2=The University of Iowa|title=Functions of dialogue underscoring in American feature film|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=X6ngAr1WLFkC&pg=PA21|access-date=March 28, 2011|year=2007|isbn=978-0-549-23504-0|pages=21–22|archive-date=January 5, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140105070019/http://books.google.com/books?id=X6ngAr1WLFkC&pg=PA21|url-status=live}}</ref> Over the years, Steiner's score was recorded by multiple record labels and the original motion picture soundtrack has been issued on a compact disc.<ref>{{cite web| url = http://www.americanmusicpreservation.com/KingKong1933.htm| title = KING KONG - 75th anniversary of the film and Max Steiner's great film score| access-date = March 2, 2019| archive-date = March 6, 2019| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20190306044804/http://www.americanmusicpreservation.com/KingKong1933.htm| url-status = live}}</ref> |

|||

==Critical reaction== |

|||

The film received mostly positive but some negative reviews on its first release. [[Variety (magazine)|''Variety'']] concluded "after the audience becomes used to the machine-like movements and other mechanical flaws in the gigantic animals on view, and become accustomed to the phony atmosphere, they may commence to feel the power." The ''New York Times'' found it a fascinating adventure film: "Imagine a fifty-foot beast with a girl in one paw climbing up the outside of the Empire State Building, and after putting the girl on a ledge, clutching at airplanes, the pilots of which are pouring bullets from machine guns into the monster's body". <ref> {{cite news | first=Mordaunt | last=Hall | title=King Kong | date=March 3, 1933 | publisher=New York Times | url=http://movies2.nytimes.com/mem/movies/review.html?title1=&title2=KING%20KONG%20%28MOVIE%29&reviewer=Mordaunt%20Hall&pdate=&v_id=27391}} </ref> |

|||

==Release== |

|||

More recently, [[Roger Ebert]] wrote in his Great Films review that the effects are not up to modern standards, but "there is something ageless and primeval about "King Kong" that still somehow works." <ref> {{cite news | first=Roger | last=Ebert | title=King Kong (1933) | date=February 3, 2002 | publisher=Chicago Sun Times | url=http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=%2F20020203%2FREVIEWS08%2F202030301%2F1023}} </ref> |

|||

[[File:RKO Keith's Theater ad - 24 March 1933, NW, Washington, DC.png|thumb|left|upright|Theatrical advertisement from 1933]] |

|||

[[File:King Kong Re-release Trailer.webm|thumb|Trailer for the 1938 re-release of ''King Kong'' (1:32).]] |

|||

[[File: Grauman's Chinese Theatre, by Carol Highsmith fixed & straightened.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Grauman's Chinese Theatre]], where ''King Kong'' held its world premiere.]] |

|||

===Censorship and restorations=== |

|||

== Trivia == |

|||

The [[Motion Picture Production Code|Production Code]]'s stricter decency rules were put into effect in Hollywood after the film's 1933 premiere and it was progressively censored further, with several scenes being either trimmed or excised altogether for the 1938-1956 rereleases. These scenes were as follows: |

|||

*In the original script, the gorilla is named "Kong". "King" was added to the title by studio publicists. Apart from the opening titles, the only time the name "King Kong" appears in the picture is on the marquee above the theater where Kong is being exhibited — and the marquee was in fact added to the scene as an optical composite after the live footage of the theater entrance had been shot. However, Denham does refer to Kong in his speech to the theater audience as having been "a king in his native land". |

|||

* The Brontosaurus mauling crewmen in the water, chasing one up a tree and killing him. |

|||

*The giant gate used in the 1933 movie was burned along with other old studio sets for the burning of [[Atlanta, Georgia|Atlanta]] scene in ''[[Gone with the Wind (film)|Gone with the Wind]]''. The gate was originally constructed for the Babylonian segment in [[D. W. Griffith]]'s 1916 film ''[[Intolerance (movie)|Intolerance]]''. |

|||

* Kong undressing Ann Darrow and sniffing his fingers. |

|||

*The gate can also be spotted in the [[Bela Lugosi]] serial ''The Return of Chandu'' (1934). |

|||

* Kong biting and stepping on natives when he attacks the village. |

|||

*''King Kong'' is often credited as being [[Adolf Hitler]]'s favorite film (unconfirmed but mentioned in many news and magazine articles on the film, including a [http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/13.10/kingkong.html?pg=3 2005 Wired Magazine story]) |

|||

* Kong biting a man in New York. |

|||

*Jungle scenes were filmed on the same set as the jungle scenes in ''[[The Most Dangerous Game]]'' (1932). |

|||

* Kong mistaking a sleeping woman for Ann and dropping her to her death, after realizing his mistake. |

|||

*The original metal armature used to bring Kong to life, as well as other original props from the 1933 film, can be seen in the book ''It Came From Bob's Basement''. It was on display in [[London]] until a few years ago in the now-closed Museum of the Moving Image. |

|||

* An additional scene portraying giant insects, spiders, a [[reptile]]-like predator and a tentacled creature devouring the crew members shaken off the log by Kong onto the floor of the canyon below was deemed too gruesome by RKO even by pre-Code standards (though Cooper also thought it "stopped the story"), and thus the scene was studio self-censored prior to the original release. The footage is considered lost, with the exception of only a few stills and pre-production drawings.{{sfn|Morton|2005|pp=75–76}}<ref>{{cite web |last1=Wednesday |first1=WTM • |title=The Lost Scene from 1933's King Kong - the Spider Pit |url=https://www.neatorama.com/2018/12/12/The-Lost-Scene-from-1933-s-King-Kong-the-Spider-Pit/ |website=Neatorama |date=December 12, 2018 |access-date=January 28, 2020 |language=en |archive-date=January 28, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200128131026/https://www.neatorama.com/2018/12/12/The-Lost-Scene-from-1933-s-King-Kong-the-Spider-Pit/ |url-status=live}}</ref> There are also claims that it was never filmed and was only in the script and novelization.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2024-04-02 |title=King Kong (non-existent cut content of Pre-code monster adventure film; 1933) - The Lost Media Wiki |url=https://lostmediawiki.com/King_Kong_(non-existent_cut_content_of_Pre-code_monster_adventure_film;_1933) |access-date=2024-04-28 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240402171457/https://lostmediawiki.com/King_Kong_(non-existent_cut_content_of_Pre-code_monster_adventure_film;_1933) |archive-date=April 2, 2024 }}</ref> |

|||

*King Kong's height is different in different parts of the movie. He appears to be 18 feet tall on the island, 24 feet on stage in New York and 50 feet on the Empire State Building. |

|||

*The film's budget was approximately $600,000 USD |

|||

*[[Paul du Chaillu]]'s travel narrative ''Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa'' (1861) was a favorite of [[Merian C. Cooper]] when he was a child. The gorilla chase scene in the book was likely an inspiration for King Kong. |

|||

*In the original script Kong was going to climb the [[Chrysler Building]]. The [[Empire State Building]] and the Chrysler Building were both being built at the very same time and the Chrysler Building was supposed to be the taller of the two. There was a competition who could build the tallest building in the world, so the Empire State Building creators added an observation deck and mooring mast at the last minute, making it the world's tallest building. The script was changed and Kong climbed the Empire State Building, looking down on the spire of the Chrysler building.[http://www.t-shirtking.com/blog/archives/000123.html] |

|||

* In the 1933 film, King Kong is displayed at the [[Palace Theatre, New York|Palace Theatre]] in New York City. Along with the film itself, the marquee makes references to the folktale of "[[Beauty and the Beast]]". Interestingly enough, the Palace is the same theatre that Disney's ''[[Beauty and the Beast (theatrical production)|Beauty and the Beast]]'' opened at in 1994 (and ran here until 1999). On a side note, by 1933, the Palace had become a full-fledged movie house no longer running stage acts. |

|||

RKO did not preserve copies of the film's negative or release prints with the excised footage, and the cut scenes were considered lost for many years. In 1969, a 16mm print, including the censored footage, was found in Philadelphia. The cut scenes were added to the film, restoring it to its original theatrical running time of 100 minutes. This version was re-released to [[art house]]s by [[Janus Films]] in 1970.{{sfn|Morton|2005|pp=75–76}} Over the next two decades, [[Universal Pictures|Universal Studios]] undertook further photochemical restoration of ''King Kong.'' This was based on a 1942 release print with missing censor cuts taken from a 1937 print, which "contained heavy vertical scratches from projection."<ref>[http://www.creativeplanetnetwork.com/dcp/news/king-kong/43148 Millimeter Magazine article, 1 January 2006] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130521015000/http://www.creativeplanetnetwork.com/dcp/news/king-kong/43148 |date=May 21, 2013}} Retrieved: March 15, 2012</ref> An original release print located in the UK in the 1980s was found to contain the cut scenes in better quality. After a 6-year worldwide search for the best surviving materials, a further, fully digital restoration utilizing [[4K resolution]] [[Image scanner|scanning]] was completed by [[Warner Bros.]] in 2005.<ref name=autogenerated1>[http://www.thedigitalbits.com/site_archive/articles/robertharris/harris102505.html "Robert A. Harris On King Kong"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140813142801/http://thedigitalbits.com/site_archive/articles/robertharris/harris102505.html |date=August 13, 2014}} Retrieved: March 15, 2012,</ref> This restoration also had a 4-minute [[overture]] added, bringing the overall running time to 104 minutes. |

|||

===Dinosaurs and reptiles=== |

|||

[[Image:KingKong1933.jpg|250px|thumb|Kong battles a pterosaur on Skull Island]] |

|||

The [[dinosaur]]s and other prehistoric animals depicted on Skull Island are never precisely identified in the film. O'Brien based his models on well-informed reconstructions, particularly on those of [[Charles Knight]], which were exhibited in major museums at the time (in particular, the [[American Museum of Natural History]] in New York City, and the [[Chicago Natural History Museum]]). The reconstructions are surprisingly accurate for their time: paleontologist [[Robert T. Bakker]] has commented that despite their anatomical inaccuracies, the depiction of the Brontosaurus coming out of the swamp and moving on land, and the Tyrannosaurus being a swift, active predator are actually more accurate then what scientists at the time were teaching. Even so, there are many inaccuracies when compared with 21st century knowledge. However, it is important to realize that King Kong is not a [[documentary film|documentary]] on prehistoric life; it is a movie made for public entertainment, and is not meant to be perfectly accurate. With that understood, the animals seen on Skull Island include (in order of first appearance): |

|||

Somewhat controversially, ''King Kong'' was [[film colorization|colorized]] for a 1989 [[Turner Home Entertainment]] video release.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1989-02-17-8903060204-story.html |title=COLORIZED ''KING KONG'' MAY BUG FANS |work=[[Chicago Tribune]] |first=Andy |last=Wickstrom |date=Feb 17, 1989 |access-date=Jul 26, 2022}}</ref> The following year, this colorized version was shown on Turner's [[TNT (American TV network)|TNT]] channel.<ref>[http://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/2690/King-Kong/misc-notes.html "King Kong: Miscellaneous Notes" at TCM] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120504153046/http://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/2690/King-Kong/misc-notes.html |date=May 4, 2012}} Retrieved: March 15, 2012</ref> |

|||

*A ''[[Stegosaurus]]''-like creature (25–30 feet long) appears in a sequence in which it is disturbed by [[Carl Denham]]'s crew. Like an angry rhinoceros, it charges the men and they fall it with a gas-bomb. As they walk by it, it starts to get up again and is shot. |

|||

*A long-necked ''[[Apatosaurus]]''-like or ''[[Brontosaurus]]''-like creature (70 feet long) is depicted as a swamp-dwelling carnivore (they were in fact land-dwelling herbivores). The dinosaur is disturbed by the rescue party's raft as it crosses a swamp and capsizes it, attacking the men in the water. (The gas bombs that they brought are lost here.) Several of them are chased onto land and one fellow, climbing a tree, is cornered and apparently eaten by the animal. |

|||

*A large 2-legged lizard-like creature: This creature climbs up a vine from the [[crevasse]] to attack [[Jack Driscoll]]. It falls back into the pit when Jack cuts the vine it is climbing. Other than the two limbs, the other distinct feature of this unique creature is the [[iguana]]-like ridge of spikes down its back. |

|||

*A large [[theropod]], commonly identified as a [[Tyrannosaurus]] (certainly, it appears to be modeled after [[Charles R. Knight]]'s depiction of a Tyrannosaurus).{{fact}}. However, it possesses three finger per hand, unlike the Tyrannosaur's two, and in an interview included on the DVD release, Cooper refers to this beast as an [[Allosaurus]], not a Tyrannosaurus, which would justify the number of fingers. The animals is inaccurately depicted as dragging its tail on the ground. It appears in a lengthy sequence in which it attacks Ann and Kong leaps to her defence to fight the dinosaur. (This scene was said to be the most difficult and time-consuming sequence of the movie to shoot.){{fact}} |

|||

*A [[Plesiosaur]]-like creature: a highly stylized, serpentine aquatic reptile with a long neck and tail as well as two pairs of flippers. It inhabits the bubbling swamp area near Kong's cave. |

|||

*A [[Pteranodon]]-like creature: A winged reptile, distantly related to the dinosaurs. It, like the "Tyrannosaurus" and the "plesiosaur", is killed by Kong as the result of attacking Ann. |

|||

*The screenplay also describes a scene not present in the finished scene in which a [[Styracosaurus]] prevents the men from crossing back over the log to escape from Kong. Willis O'Brien made a model of it, but whether it was actually used is unknown. Peter Jackson and the WETA crew, on recreating the spider pit sequence, also recreated the Styracosaur chasing the men and cutting off their escape. O'Brien eventually used his Styracosaur model in ''[[Son of Kong]]''. |

|||

=== |

===Television=== |

||

After the 1956 re-release, the film was sold to television and was first broadcast on March 5, 1956.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Rainho|first1=Manny|title=This Month in Movie History|journal=Classic Images|date=March 2015|issue=477|page=26}}</ref> |

|||

The film includes a number of scenes that have become iconic, including: |

|||

*The native ceremony for the "bride" of Kong. |

|||

*The crew being hunted by a carnivorous [[Brontosaurus]]-like creature. |

|||

*Kong shaking the crew off a fallen tree over a chasm. |

|||

*Kong battling an [[Tyrannosaurus]]-like creature. |

|||

*Kong battling a [[Plesiosaur]]-like creature. |

|||

*Kong's fight with a giant [[Pteranodon]]-like creature. |

|||

*Kong attacking the native village. |

|||

*Screaming [[Ann Darrow]] (Wray) being held in Kong's giant hand. Later in life, Wray named her autobiography ''On the Other Hand'' (ISBN 0312022654) in memory of her screaming in Kong's grip. |

|||

*Kong's escape and rampage in New York. |

|||

*In the finale Kong carries a screaming Ann to the top of the [[Empire State Building]] but is gunned down by a swarm of [[helldiver]] [[biplane]]s. |

|||

=== |

===Home media=== |

||

In 1984, ''King Kong'' was one of the first films to be released on [[LaserDisc]] by the [[Criterion Collection]], and was [[Audio commentary#History of audio commentaries|the first movie]] to have an [[audio commentary]] track included.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.denverpost.com/2005/08/24/if-dvd-killed-the-film-star-criterion-honors-the-ghost/|title=If DVD killed the film star, Criterion honors the ghost|date=August 24, 2005|website=The Denver Post|language=en-US|access-date=November 11, 2019|archive-date=November 11, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191111123300/https://www.denverpost.com/2005/08/24/if-dvd-killed-the-film-star-criterion-honors-the-ghost/|url-status=live}}</ref> Criterion's audio commentary was by film historian [[Ronald Haver|Ron Haver]] in 1985. [[Image Entertainment]] released another LaserDisc, this time with a commentary by film historian and soundtrack producer Paul Mandell. The Haver commentary was preserved in full on the [[FilmStruck]] streaming service. ''King Kong'' had numerous [[VHS]] and [[LaserDisc]] releases of varying quality prior to receiving an official studio release on DVD. Those included a [[Turner Home Entertainment|Turner]] 60th-anniversary edition in 1993 featuring a front cover that had the sound effect of Kong roaring when his chest was pressed. It also included a 25-minute documentary, ''It Was Beauty Killed the Beast'' (1992). The documentary is also available on two different UK ''King Kong'' DVDs, while the colorized version is available on DVD in the UK and Italy.<ref>[http://dvdcompare.net/comparisons/film.php?fid=2930 DVDCompare.com: ''King Kong'' (1933)] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111127021539/http://dvdcompare.net/comparisons/film.php?fid=2930 |date=November 27, 2011 }} Retrieved: April 8, 2012</ref> [[Warner Home Video]] re-released the black and white version on VHS in 1998 and again in 1999 under the ''Warner Bros. Classics'' label, with this release including the 25-minute 1992 documentary.{{Citation needed|date=February 2023}} |

|||

Known deleted, censored, or never-filmed scenes (some restored or reconstructed today). |

|||

In 2005, [[Warner Bros.]] released its digital restoration of ''King Kong'' in a US 2-disc Special Edition DVD, coinciding with the theatrical release of [[Peter Jackson]]'s [[King Kong (2005 film)|remake]]. It had numerous extra features, including a new, third audio commentary by [[visual effects]] artists [[Ray Harryhausen]] and [[Ken Ralston]], with archival excerpts from actress [[Fay Wray]] and producer/director [[Merian C. Cooper]]. Warners issued identical DVDs in 2006 in Australia and New Zealand, followed by a US digibook-packaged Blu-ray in 2010.<ref>[http://www.dvdbeaver.com/film/dvdcompare/kingkong.htm DVDBeaver.com ''King Kong'' comparison] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120417112537/http://www.dvdbeaver.com/film/DVDCompare/kingkong.htm |date=April 17, 2012}} Retrieved: June 14, 2015</ref> In 2014, the Blu-ray was repackaged with three unrelated films in a ''4 Film Favorites: Colossal Monster Collection.'' At present, [[Universal Pictures|Universal]] holds worldwide rights to Kong's home video releases outside of North America, Latin America, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand. All of Universal's releases only contain the earlier, 100-minute, pre-2005 restoration.<ref name=autogenerated1 /> |

|||

*Kong battles three [[triceratops]]. Unfilmed but planned. |

|||

*The [[sauropod]] more violently kills three sailors in the water. |

|||

*A [[styracosaur]] chases the sailors onto the log. Unknown if this was filmed or cut later. |

|||

*When Kong drops the log down the chasm, four surviving sailors are eaten alive by a giant spider, an octopus-like insect, a giant scorpion/crab, and a giant crocodile/lizard. When Merian C. Cooper showed the film to a preview audience with the scene intact, viewers were either frightened, scared out of the theater, or wouldn't stop talking about the scene. Ultimately, Cooper cut the scene. When asked later, he claimed that he cut the scene due to pacing. |

|||

*Kong pulls off Ann's clothes and smells them. Censored for the 1930s rerelease, now in every official print since 1972. |

|||

*A longer scene of Jack and Anne running away from Kong`s lair. This was cut by Cooper for pacing even though the painstaking stop-motion animation had been completed. |

|||

*Kong steps on two natives. Censorship cut. |

|||

*Kong kills two natives and a New Yorker with his teeth. Censorship cut. |

|||

*Kong picks a sleeping woman out of the hotel, then realizing she's not Ann, drops her to the streets below to her death. Censorship cut. |

|||

*Kong breaks up a poker party in the hotel. It's unknown if this was filmed or not, but the reason why it was dropped was because it was too similar to an almost identical scene in ''[[The Lost World]]''. |

|||

*A shot showing Kong's body as he falls off the Empire State Building. This was cut because the special effects didn't look realistic enough; Kong seemed 'transparent' as he fell to the streets below. |

|||

== |

==Reception== |

||

===Box office=== |

|||

A sequel, ''[[The Son of Kong]]'', was also released in 1933. The story concerned a return expedition to Skull Island that discovers that Kong has left behind an [[albino]] son. |

|||

The film was a box-office success, earning about $5 million in worldwide rentals on its initial release, and an opening weekend estimated at $90,000. Receipts fell by up to 50% during the second week of the film's release because of the national [[Emergency Banking Act|"bank holiday"]] declared by President [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]]'s during his first days in office.<ref name="lords">{{cite book |title=[[Lords of Finance]] |last=Ahamed |first=Liaquat |author-link=Liaquat Ahamed |date=2009 |publisher=[[Penguin Books]] |isbn=9780143116806 |page=[https://archive.org/details/lordsoffinanceba00aham/page/452 452] }}</ref> During the film's first run it made a profit of $650,000.<ref name="rko"/> Prior to the 1952 re-release, the film is reported to have worldwide rentals of $2,847,000 including $1,070,000 from the United States and Canada and profits of $1,310,000.<ref name="rko"/> After the 1952 re-release, ''[[Variety (magazine)|Variety]]'' estimated the film had earned an additional $1.6 million in the United States and Canada, bringing its total to $3.9 million in cumulative domestic rentals.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://archive.org/stream/variety189-1953-01#page/n361/mode/1up|title='Gone,' With $26,000,000, Still Tops All-Timers, Greatest Show Heads 1952|work=[[Variety (magazine)|Variety]]|date=January 21, 1953|page=4}}</ref> Profits from the 1952 re-release were estimated by the studio at $2.5 million.<ref name="rko"/> |

|||

===Critical response=== |

|||

''See [[King Kong]] for more information on other Kong films.'' |

|||

{{Expand section|date=February 2023}} |

|||

On [[Rotten Tomatoes]], the film holds an approval rating of 97% based on {{nowrap|116 reviews}}, with an average rating of 9/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "''King Kong'' explores the soul of a monster – making audiences scream and cry throughout the film – in large part due to Kong's breakthrough special effects."<ref>{{cite web |title=King Kong |url=https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/1011615_king_kong |website=Rotten Tomatoes |access-date=November 19, 2022 |language=en |archive-date=December 30, 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091230104912/http://uk.rottentomatoes.com/m/1011615-king_kong/ |url-status=live }}</ref> On [[Metacritic]] the film has a weighted average score of 92 out of 100, based on 12 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".<ref name="metacriticfilm">{{cite web |title=King Kong (1933) Reviews – Metacritic |url=http://www.metacritic.com/movie/king-kong-1933?ftag=MCD-06-10aaa1c |website=Metacritic.com |publisher=Metacritic |access-date=June 21, 2018 |archive-date=July 29, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180729172556/http://www.metacritic.com/movie/king-kong-1933?ftag=MCD-06-10aaa1c |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

[[Variety (magazine)|''Variety'']] thought the film was a powerful adventure.<ref>{{cite magazine |last=Bigelow|first=Joe|date=1933-03-06 |title=King Kong |magazine=Variety |url=https://www.variety.com/review/VE1117792322 |access-date=February 20, 2010}}</ref> ''[[The New York Times]]'' gave readers an enthusiastic account of the plot and thought the film a fascinating adventure.<ref>Hall</ref> [[John Mosher (writer)|John Mosher]] of ''[[The New Yorker]]'' called it "ridiculous," but wrote that there were "many scenes in this picture that are certainly diverting."<ref>{{cite magazine |last=Mosher |first=John |author-link=John Mosher (writer) |date=March 11, 1933 |title=The Current Cinema |magazine=[[The New Yorker]] |location=New York |publisher=F-R Publishing Corporation |page= 56 }}</ref> The ''[[New York World-Telegram]]'' said it was "one of the very best of all the screen thrillers, done with all the cinema's slickest camera tricks."<ref>{{cite magazine|date=March 7, 1933 |title=New York Reviews |magazine=[[The Hollywood Reporter]] |location=Los Angeles |page= 2 }}</ref> The ''[[Chicago Tribune]]'' called it "one of the most original, thrilling and mammoth novelties to emerge from a movie studio."<ref>{{cite news |date=April 23, 1933 |title=Monster Ape Packs Thrills in New Talkie |work=[[Chicago Tribune]] |location=Chicago |page=Part 7, p.8}}</ref> |

|||

==Awards== |

|||

The now classic film was not nominated for any [[Academy Awards]], although it's reasonable to speculate that it could have been nominated for Special Effects for its many groundbreaking techniques, if the award had existed at the time. As it was, however, the Special Effects category would not be introduced until 1939, with ''[[The Rains Came]]'' receiving the honor. |

|||

On February 3, 2002, [[Roger Ebert]] included ''King Kong'' in his "[[The Great Movies|Great Movies]]" list, writing that "In modern times the movie has aged, as critic [[James Berardinelli]] observes, and 'advances in technology and acting have dated aspects of the production.' Yes, but in the very artificiality of some of the special effects, there is a creepiness that isn't there in today's slick, flawless, computer-aided images... Even allowing for its slow start, wooden acting, and wall-to-wall screaming, there is something ageless and primeval about ''King Kong'' that still somehow works."<ref>{{Cite web|last=Ebert|first=Roger|date=February 3, 2002|title=King Kong movie review & film summary (1933)|url=https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-king-kong-1933|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130417055656/http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-king-kong-1933|archive-date=April 17, 2013|access-date=December 13, 2020|website=[[RogerEbert.com]]|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

The film has been selected for preservation in the United States [[National Film Registry]] in 1991. |

|||

===Criticism of racism and sexism=== |

|||

==Video releases== |

|||

In the 19th and early 20th century, people of African descent were commonly represented visually as ape-like, a metaphor that fit racist stereotypes further bolstered by the emergence of [[scientific racism]].<ref>Grant, Elizabeth. (1996). 'Here Comes the Bride.' In: Grant, Barry Keith (ed.). The Dread of Difference: Gender and the Horror Film. Austin: University of Texas Press. P.373</ref> Early films frequently mirrored racial tensions. While ''King Kong'' is often compared to the story of ''[[Beauty and the Beast]],'' many film scholars have argued that the film was a [[cautionary tale]] about [[interracial relationships|interracial romance]], in which the film's "carrier of blackness is not a human being, but an ape."<ref name="GoffEberhardt2008">{{cite journal|last1=Goff|first1=Phillip Atiba|last2=Eberhardt|first2=Jennifer L.|last3=Williams|first3=Melissa J.|last4=Jackson|first4=Matthew Christian|title=Not yet human: Implicit knowledge, historical dehumanization, and contemporary consequences.|journal=Journal of Personality and Social Psychology|volume=94|issue=2|year=2008|page=293|issn=1939-1315|doi=10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.292|pmid=18211178}}</ref><ref>Kuhn, Annette. (2007). King Kong. In: Cook, Pam. (ed.) The Cinema Book. London: British Film Institute. P,41. and Robinson, D. (1983). King Kong. In: Lloyd, A. (ed.) Movies of the Thirties. Orbis Publishing Ltd. p.58.</ref> |

|||

[[Image:King Kong early colorized version.jpg|thumb|300px|right|The colorized version.]] |

|||

The film was released officially for the first time on [[DVD]] in the U.S. in November of 2005, after long being only available on [[home video]] releases, and bootleg [[VHS]] and DVD releases. |

|||

Cooper and Schoedsack rejected any allegorical interpretations, insisting in interviews that the film's story contained no hidden meanings.<ref name="Erb2009">{{cite book|author=Cynthia Marie Erb|title=Tracking King Kong: A Hollywood Icon in World Culture|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pU7mnHBaqvQC|year=2009|publisher=Wayne State University Press|isbn=978-0-8143-3430-0|page=xvii|access-date=December 15, 2016|archive-date=August 4, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200804014727/https://books.google.com/books?id=pU7mnHBaqvQC|url-status=live}}</ref> In an interview, which was published posthumously, Cooper explained the deeper meaning of the film. The inspiration for the climactic scene came when, "as he was leaving his office in Manhattan, he heard the sound of an airplane motor. He reflexively looked up as the sun glinted off the wings of a plane flying extremely close to the tallest building in the city... he realized if he placed the giant gorilla on top of the tallest building in the world and had him shot down by the most modern of weapons, the armed airplane, he would have a story of the primitive doomed by modern civilization."<ref name="Haver1976">{{cite magazine |last=Haver |first=Ron |date=December 1976 |title=Merian C. Cooper: The First King of Kong |url=https://www.scribd.com/document/153812357/American-Film-Magazine-December-1976 |url-status=dead |magazine=American Film Magazine |location=New York |publisher=[[American Film Institute]] |page=18 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200802224054/https://www.scribd.com/document/153812357/American-Film-Magazine-December-1976 |archive-date=August 2, 2020 |access-date=June 7, 2019}}</ref> |

|||

[[Warner Brothers|Warner Home Video]] and [[Turner Entertainment]] (the current copyright owners of ''King Kong'') have released the film in a two-disc special edition that has been released both with regular DVD packaging and in a '''Collector's Edition''' featuring both discs in a collectible tin can which also includes a variety of other printed extras exclusive to the Collector's Edition. [[As of 2006]] the US Special Edition has not been released in the United Kingdom. |

|||

The film was initially banned in [[Nazi Germany]], with the censors describing it as an "attack against the nerves of the German people" and a "violation of German race feeling". However, according to confidant [[Ernst Hanfstaengl]], [[Adolf Hitler]] was "fascinated" by the film and saw it several times.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.spiegel.de/fotostrecke/hitlers-kino-fuehrer-faible-fuer-garbo-oder-dick-und-doof-fotostrecke-132203.html|title=Hitlers Kino: "Führer"-Faible für Garbo oder Dick und Doof|first=SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg|last=Germany|newspaper=Der Spiegel|date=December 2, 2015|access-date=August 27, 2019|archive-date=April 4, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190404161903/http://www.spiegel.de/fotostrecke/hitlers-kino-fuehrer-faible-fuer-garbo-oder-dick-und-doof-fotostrecke-132203.html|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

At the same time that these two solo editions of ''King Kong'' were released, Warner Brothers also released a DVD box set featuring the original 1933 ''King Kong,'' as well as the films ''[[The Son of Kong]],'' and ''[[Mighty Joe Young]],'' which were also released separately. |

|||

The film was later criticized for racist stereotyping of the natives and Charlie the Cook, played by [[Victor Wong (actor born 1906)|Victor Wong]], who upon discovering the kidnapping of Ann Darrow, exclaims "Crazy black man been here!".<ref>{{cite web |title=KING KONG: SPECIAL EDITION |url=https://www.starburstmagazine.com/reviews/dvd-review-king-kong-special-edition/ |website=www.starburstmagazine.com/ |date=29 June 2021 |access-date=4 June 2024}}</ref> The film has been noted for its depiction of Ann as a [[damsel in distress]]. In her autobiography, Wray wrote that Ann's screaming was too much.<ref>{{cite news | url=https://hollywoodprogressive.com/film/king-kong-and-fay-wray | title=King Kong and Fay Wray | newspaper=Hollywood Progressive | date=March 2, 2023 }}</ref> However, Nick Hilton in ''[[The Independent]]'' stated that the film "may look a little foolish to us (not to mention racist, sexist and, shall we say, symbolically naive) but it still packs a visceral wallop",<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/the-first-and-original-king-kong-518889.html | title=The first (And original) King Kong | website=[[Independent.co.uk]] | date=December 10, 2005 }}</ref> while Ryan Britt felt that critics were willing to overlook the film's problematic aspects as "just unattractive byproducts of the era in which the film was made...that the meta-fictional aspects almost excuse some of the cultural insensitivity".<ref>{{cite web | url=https://reactormag.com/think-hes-crazy-nah-just-enthusiastic-rewatching-king-kong-1933/ | title=Think He's Crazy? Nah, Just Enthusiastic. Rewatching King Kong (1933) | date=October 24, 2011 }}</ref> In 2013 an article entitled "11 of The Most Racist Movies Ever Made" described the film's natives "as subhuman, or primate... (not) even have a distinct way of communicating..." The article also brought up the racial allegory between Kong and black men, particularly how Kong "meets his demise due to his insatiable desire for a white woman".<ref>{{Cite web|date=2013-11-22|title=11 of The Most Racist Movies Ever Made|url=https://atlantablackstar.com/2013/11/22/11-of-the-most-racist-movies-ever-made/3/|access-date=2024-06-10|website=Atlanta Black Star|language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

''King Kong'' when it was released on a [[Criterion Collection|Criterion]] [[laserdisc]] in 1985 featured the first ever audio commentary track, by Ron Haver, on a [[home video]] release. |

|||

===Legacy=== |

|||

The film was also part of the [[film colorization]] controversy in the 1980's when it and other classic black and white films were colorized for television. In recent years, the colorized version has become highly prized among ''Kong'' collectors, and there have even been bootleg DVD releases that have appeared on [[eBay]], some of which even going as far as to contain both versions of the film. Although the colorized version was released officially on the 2004 PAL-format Region 2 DVD from [[Universal Studios|Universal]], it has never been made available on DVD officially in the Region 1 NTSC format. |

|||

{{see also|Wasei Kingu Kongu|The King Kong That Appeared in Edo}} |

|||

[[File:King Kong japanese poster 1.jpg|thumb|The 1952 re-release of ''King Kong'' by [[Daiei Film]] was the first [[post-war]] distribution of [[monster movie]]s in Japan.<ref name=Ui />]] |

|||