March of the Volunteers: Difference between revisions

→Lyrics: en version too, this is the en Wikipedia and not all readers read Mandarin |

|||

| (652 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|National anthem of the People's Republic of China}} |

|||

{{stack begin}} |

|||

{{Redirect|Chinese National Anthem|the national anthem of the Republic of China|National Anthem of the Republic of China}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=December 2021}} |

|||

{{Infobox anthem |

{{Infobox anthem |

||

| title = {{normal|{{unbulleted list|{{lang|zh-Hans-CN|义勇军进行曲}}|{{transliteration|zh|Yìyǒngjūn jìnxíngqǔ}}}}}} |

|||

|title = March of the Volunteers |

|||

|transcription = |

| transcription = |

||

|english_title = |

| english_title = March of the Volunteers |

||

|image = |

| image = March of the Volunteers (Pathe Records – 1935).png |

||

|image_size =Original single released in 1935 |

| image_size = Original single released in 1935 |

||

|caption = |

| caption = |

||

|prefix = National |

| prefix = National |

||

| country = [[China|People's Republic of China]]{{efn|Including its two [[Special administrative regions of China|special administrative regions]], [[Hong Kong]] and [[Macau]].}} |

|||

|country =<br />{{CHN}}<br />{{HKG}}<br />{{MAC}} |

|||

---- |

|||

|author = [[Tian Han]] |

|||

{{unbulleted list|Military anthem of the [[200th Division (National Revolutionary Army)|200th Division]] of the [[National Revolutionary Army]]|{{nobold|(1938–1949)}}}} |

|||

|lyrics_date = 1934 |

|||

| |

| author = [[Tian Han]] |

||

| |

| lyrics_date = 1934 |

||

| |

| composer = [[Nie Er]] |

||

| music_date = 16 May 1935 |

|||

* {{nowrap|27 September 1949 (Provisional)<ref name="provo" />}} |

|||

| adopted = * {{unbulleted list|January 1938|(200th Division)}} |

|||

* 4 December 1982 ([[Laws of the People's Republic of China|Official]]) |

|||

* |

* {{unbulleted list|{{nowrap|27 September 1949|(provisional)<ref name="provo" />}}}} |

||

* {{unbulleted list|4 December 1982|([[Laws of the People's Republic of China|official]])}} |

|||

* 20 December 1999 ([[Macau]])<ref name="macao" /> |

|||

* |

* {{unbulleted list|1 July 1997|([[Hong Kong]])<ref name="hk" />}} |

||

* {{unbulleted list|20 December 1999|([[Macau]])<ref name="macao" />}} |

|||

|sound = March of the Volunteers instrumental.ogg |

|||

* {{unbulleted list|14 March 2004|([[Chinese Constitution|constitutional]])<ref name="constitution" />}} |

|||

|sound_title = March of the Volunteers |

|||

* {{unbulleted list|1 October 2017|(legalised)}} |

|||

| sound = March of the Volunteers instrumental.ogg |

|||

| sound_title = U.S. Navy Band instrumental version |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Infobox Chinese |

{{Infobox Chinese |

||

|title = March of the Volunteers |

| title = March of the Volunteers |

||

| |

| pic = |

||

| picsize = 180px |

|||

|pic= |

|||

| piccap = |

|||

|picsize=180px| |

|||

| showflag = p |

|||

|piccap= |

|||

| |

| s = {{linktext|义勇军|进行曲}} |

||

| t = {{linktext|義勇軍|進行曲}} |

|||

|p2 = Yìyǒngjūn Jìnxíngqǔ |

|||

| p = Yìyǒngjūn Jìnxíngqǔ |

|||

|w2 = I-yung-chün {{nowrap|Chin-hsing-ch'ü}} |

|||

| tp = Yì-yǒng-jyun Jìn-síng-cyǔ |

|||

|l2 = {{nowrap|[[Anti-Japanese volunteer armies|Righteous-brave army]] marching melody}} |

|||

| w = {{unbulleted list|{{tone superscript|I4-yung3-chün1}}|{{tone superscript|Chin4-hsing2-ch}}{{wg-apos}}{{tone superscript|ü3}}}} |

|||

|j2 = Ji⁶-jung⁵-gwan¹ {{nowrap|Zeon³-hang⁴-kuk¹}} |

|||

| bpmf = {{unbulleted list|ㄧˋ ㄩㄥˇ ㄐㄩㄣ|ㄐㄧㄣˋ ㄒㄧㄥˊ ㄑㄩˇ}} |

|||

|y2 = Yi⁶-yung⁵-jyun¹ {{nowrap|Jin⁴-syin²-chyu³}} |

|||

| gr = Yihyeongjiun Jinnshyngcheu |

|||

|altname3 = National Anthem of the {{nowrap|People's Republic of China}} |

|||

| myr = Yìyǔngjyūn Jìnsyíngchyǔ |

|||

|s3 = {{linktext|中华人民共和国|国歌}} |

|||

| mi = {{IPAc-cmn|yi|4|.|yong|3|.|jun|1|-|j|in|4|.|x|ing|2|.|qu|3}} |

|||

|p3 = Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó Guógē |

|||

| l = March of the [[Anti-Japanese volunteer armies|Righteous and Brave Armies]] |

|||

|order = st |

|||

| j = ji6 jung5 gwan1 zeon3 hang4 kuk1 |

|||

| y = Yihyúhnggwān Jeunhàhngkūk |

|||

| ci = {{IPAc-yue|j|i|6|-|j|ung|5|-|gw|an|1|-|z|eon|3|-|h|ang|4|-|k|uk|1}} |

|||

| altname = March of the Anti-Manchukuo Counter-Japan Volunteers |

|||

| s2 = {{linktext|反满|抗日|义勇军|进行曲}} |

|||

| t2 = {{linktext|反滿|抗日|義勇軍|進行曲}} |

|||

| p2 = Fǎnmǎn Kàngrì Yìyǒngjūn Jìnxíngqǔ |

|||

| tp2 = Fǎn-mǎn Kàng-rìh Yì-yǒng-jyun Jìn-síng-cyǔ |

|||

| w2 = {{tone superscript|Fan3-man3 K}}{{wg-apos}}{{tone superscript|ang4-jih4 I4-yung3-chün1 Chin4-hsing2-ch}}{{wg-apos}}{{tone superscript|ü3}} |

|||

| bpmf2 = ㄈㄢˇ ㄇㄢˇ ㄎㄤˋ ㄖˋ ㄧˋ ㄩㄥˇ ㄐㄩㄣ ㄐㄧㄣˋ ㄒㄧㄥˊ ㄑㄩˇ |

|||

| gr2 = |

|||

| myr2 = |

|||

| mi2 = {{IPAc-cmn|f|an|3|.|m|an|3|-|k|ang|4|.|ri|4|-|yi|4|.|yong|3|.|jun|1|-|j|in|4|.|x|ing|2|.|qu|3}} |

|||

| l2 = |

|||

| j2 = |

|||

| y2 = |

|||

| altname3 = National Anthem of the People's Republic of China |

|||

| s3 = {{linktext|中华人民共和国|国歌}} |

|||

| t3 = {{linktext|中華人民共和國|國歌}} |

|||

| p3 = {{unbulleted list|Zhōnghuá Rénmín|Gònghéguó Guógē}} |

|||

| tp3 = {{unbulleted list|Jhong-huá Rén-mín|Gòng-hé-guó Guó-gē}} |

|||

| gr3 = {{unbulleted list|Jonghwa Renmin|Gonqhergwo Gwoge}} |

|||

| bpmf3 = {{unbulleted list|ㄓㄨㄥ ㄏㄨㄚˊ|ㄖㄣˊ ㄇㄧㄣˊ|ㄍㄨㄥˋ ㄏㄜˊ ㄍㄨㄛˊ|ㄍㄨㄛˊ ㄍㄜ}} |

|||

| myr3 = {{unbulleted list|Jūnghwá Rénmín|Gùnghégwó Gwógē}} |

|||

| w3 = {{unbulleted list|{{tone superscript|Chung1-hua2 Jen2-min2|Kung4-ho2-kuo2 Kuo2-ko1}}}} |

|||

| mi3 = {{unbulleted list|{{IPA|cmn|ʈʂʊ́ŋ.xwǎ ɻə̌n.mǐn|kʊ̂ŋ.xɤ̌.kwǒ kwǒ.kɤ́|}}}} |

|||

| y3 = Jūng'wàh Yàhnmàhn Guhng'wòhgwok Gwokgō |

|||

| j3 = zung1 waa4 jan4 man4 gung6 wo4 gwok3 gwok3 go1 |

|||

| ci3 = {{IPAc-yue|z|ung|1|-|w|aa|4|-|j|an|4|-|m|an|4|-|g|ung|6|-|w|o|4|-|gw|ok|3|-|gw|ok|3|-|g|o|1}} |

|||

| order = st |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{contains Chinese text}} |

|||

{{stack end}} |

|||

The "'''March of the Volunteers'''",{{efn|{{zh|s=义勇军进行曲|t=義勇軍進行曲|p=yìyǒngjūnjìnxíngqǔ|zhu=ㄧˋ ㄩㄥˇ ㄐㄩㄣ ㄐㄧㄣˋ ㄒㄧㄥˊ ㄑㄩˇ}}}} originally titled the "'''March of the Anti-Manchukuo Counter-Japan Volunteers'''",{{efn|{{zh|s=反满抗日义勇军进行曲|t=反滿抗日義勇軍進行曲|p=fǎnmǎnkàngrìyìyǒngjūnjìnxíngqǔ|zhu=ㄈㄢˇ ㄇㄢˇ ㄎㄤˋ ㄖˋㄧˋ ㄩㄥˇ ㄐㄩㄣ ㄐㄧㄣˋ ㄒㄧㄥˊ ㄑㄩˇ}}<ref name="Yunnan 2012">{{cite journal|title=淺談聶耳名歌「義勇軍進行曲」|journal=雲南文獻|issue=42|publisher=Yunnan Association of Taipei|date=25 December 2012|last=曾永介|url=https://taipei.yunnan.tw/index.php/literature/list-5/yunnanliterature42/809-article4212.html|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20210414083253/https://taipei.yunnan.tw/index.php/literature/list-5/yunnanliterature42/809-article4212.html|archivedate=14 April 2021}}</ref><ref name="宽城">{{cite news|title=中华人民共和国国歌的诞生源于长城抗战|newspaper=Kuancheng History Museum, Hebei, China|date=29 August 2013 |last=曹建民|url=http://www.kcbwg.com/Article/ShowInfo.asp?InfoID=102|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160818072908/http://www.kcbwg.com/Article/ShowInfo.asp?InfoID=102|archivedate=18 August 2016}}</ref><ref name="Liaoning Daily">{{cite news|title=红色桓仁是国歌原创素材地|newspaper=Liaoning Daily|via=People.com|date=8 February 2021|last=丛焕宇|url=http://ln.people.com.cn/n2/2021/0208/c378317-34570258.html|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20211106130632/http://ln.people.com.cn/n2/2021/0208/c378317-34570258.html|archivedate=6 November 2021}}</ref>}} has been the official [[national anthem]] of the [[People's Republic of China]] since 1978. Unlike [[historical Chinese anthems|previous Chinese state anthems]], it was written entirely in [[Written vernacular Chinese|vernacular Chinese]], rather than in [[Classical Chinese]]. |

|||

The '''"March of the Volunteers"''',<ref name="zhstate">{{lang|zh|[http://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2005-05/24/content_2615210.htm 《中华人民共和国国歌》]}} [''Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó Guógē'', "National Anthem of the People's Republic of China"]. [[State Council of the People's Republic of China]] (Beijing), 2015. Accessed 21 January 2015. {{zh icon}}</ref><ref name="state">[http://english.gov.cn/archive/china_abc/2014/08/27/content_281474983873455.htm "National Anthem"]. [[State Council of the People's Republic of China]] (Beijing), 26 August 2014. Accessed 21 January 2015.</ref> is the [[national anthem]] of the [[People's Republic of China]], including its [[special administrative region]]s of [[Hong Kong]] and [[Macau]]. Unlike most [[historical Chinese anthems|previous Chinese anthems]], it is written entirely in the [[Vernacular Chinese|vernacular]], rather than in [[Classical Chinese]]. |

|||

The [[Japanese invasion of Manchuria]] saw a boom of nationalistic arts and literature in China. This song had its lyrics written first by the communist playwright [[Tian Han]] in 1934, then [[Musical composition|set to melody]] by [[Nie Er]] and [[arrangement|arranged]] by [[Aaron Avshalomov]] for the communist-aligned [[Chinese film|film]] ''[[Children of Troubled Times]]'' (1935).<ref>The politics of songs: Myths and symbols in the Chinese communist war music, 1937–1949. CT Hung. ''Modern Asian Studies,'' 1996.</ref> It became a famous [[military anthem of China|military song]] during the [[Second Sino-Japanese War]] beyond the communist faction, most notably the Nationalist general [[Dai Anlan]] designated it to be the anthem of the [[200th Division (National Revolutionary Army)|200th Division]], who [[Chinese Expeditionary Force|fought in Burma]]. It was adopted as the PRC's provisional anthem in 1949 in place of the "[[National Anthem of the Republic of China|Three Principles of the People]]" of the [[Republic of China (1912–1949)|Republic of China]] and the [[The Internationale in Chinese|Communist "Internationale"]]. During the [[Cultural Revolution]], Tian Han was criticized and placed in prison, where he died in 1968. The song was briefly and unofficially replaced by "[[The East Is Red (song)|The East Is Red]]", then reinstated but played without lyrics, restored to official status in 1978 with altered lyrics, before the original version was fully restored in 1982. |

|||

== History == |

== History == |

||

{{National anthems of China}} |

|||

[[File:Tian Han and Nie Er.jpg|thumb|left|[[Nie Er]] ''(left)'' and [[Tian Han]] ''(right)'', photographed in [[Shanghai]] in 1933]] |

|||

[[File:Tian Han and Nie Er.jpg|thumb|[[Nie Er]] ''(left)'' and [[Tian Han]] ''(right)'', photographed in [[Shanghai]] in 1933]] |

|||

The [[lyrics]] of the "March of the Volunteers", also formally known as the '''National Anthem of the People's Republic of China''', were composed by [[Tian Han]] in 1934<ref>Huang, Natasha N. [https://books.google. |

The [[lyrics]] of the "March of the Volunteers", also formally known as the '''National Anthem of the People's Republic of China''', were composed by [[Tian Han]] in 1934<ref>Huang, Natasha N. [https://books.google.com/books?id=M7ySb1Vp-ZgC&pg=PA25 ''{{'}}East Is Red': A Musical Barometer for Cultural Revolution Politics and Culture'', pp. 25 ff.]{{Dead link|date=November 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> as two [[stanza]]s in his poem "The [[Great Wall]]" ({{lang|zh|{{linktext|萬里長城}}}}), ({{lang|zh|{{linktext|义勇军进行曲}}}}) intended either for a play he was working on at the time<ref name="rowhass">Rojas, Carlos. [https://books.google.com/books?id=IaIwmEh-OpsC&pg=PA132 ''The Great Wall: A Cultural History'', p. 132.] Harvard University Press (Cambridge), 2010. {{ISBN|0674047877}}.</ref> or as part of the [[movie script|script]] for [[Diantong Film Company|Diantong]]'s upcoming film ''[[Children of Troubled Times]]''.<ref name="chichi" /> The film is a story about a Chinese intellectual who flees during the [[Shanghai Incident]] to a life of luxury in [[Qingdao]], only to be driven to [[Pacification of Manchukuo|fight the Japanese occupation]] of [[Manchuria]] after learning of the death of his friend. [[Urban legend]]s later circulated that Tian wrote it in jail on [[rolling paper]]<ref name="rowhass" /> or the liner paper from cigarette boxes<ref name="roo" /> after being arrested in Shanghai by the [[Kuomintang|Nationalists]]; in fact, he was arrested in Shanghai and held in [[Nanjing]] just after completing his draft for the film.<ref name="chichi" /> During March<ref name="chih2">Liu (2010), [https://books.google.com/books?id=AjE3HNO7j3kC&pg=PA154 p. 154] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171107032719/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=AjE3HNO7j3kC&pg=PA154 |date=7 November 2017 }}.</ref> and April 1935,<ref name="chichi" /> in Japan, [[Nie Er]] set the words (with minor adjustments)<ref name="chichi" /> to music; in May, Diantong's sound director He Luting had the Russian composer [[Aaron Avshalomov]] arrange their orchestral accompaniment.<ref name="avant" /> The song was performed by [[Gu Menghe]] and [[Yuan Muzhi]], along with a small and "hastily-assembled" chorus; He Luting consciously chose to use their first take, which preserved the [[Cantonese]] accent of several of the men.<ref name="chichi" /> On 9 May, Gu and Yuan recorded it in more standard Mandarin for [[Pathé Orient]]'s Shanghai branch{{efn|Pathé's local music director at the time was the French-educated [[Ren Guang]], who in 1933 was a founding member of [[Soong Ching-ling]]'s "[[Soviet Friends Society]]"'s Music Group. Prior to his arrest, Tian Han served as the group's head and Nie Er was another charter member. [[Liu Liangmo]], who subsequently did much to popularize the use of the song, had also joined by 1935.<ref name="avant" />}} ahead of the movie's {{Clarify|date=March 2023}} release, so that it served as a form of advertising for the film.<ref name="avant" /> |

||

Originally translated as |

Originally translated as "Volunteers Marching On",<ref name="dianxin" /><ref>Yang, Jeff & al. [https://books.google.com/books?id=amqzDMOzaCUC&pg=PA136 ''Once Upon a Time in China: A Guide to Hong Kong, Taiwanese, and Mainland Chinese Cinema'', p. 136.] Atria Books (New York), 2003.</ref> the [[English language|English]] name references the several [[anti-Japanese volunteer armies|volunteer armies]] that opposed [[Empire of Japan|Japan]]'s [[Japanese invasion of Manchuria|invasion of Manchuria]] in the 1930s; the Chinese name is a poetic variation—literally, the "Righteous and Brave Armies"—that also appears in other songs of the time, such as the 1937 "[[Sword March]]". |

||

[[File:Sonsanddaughtersintimeofstormmovieposter.jpg|thumb|left|The |

[[File:Sonsanddaughtersintimeofstormmovieposter.jpg|thumb|left|The poster for ''[[Children of Troubled Times]]'' (1935), which used the march as its [[theme song]]]] |

||

In May 1935, the same month as the movie's release, [[Lü Ji (composer)|Lü Ji]] and other leftists in [[Shanghai]] had begun an amateur choir and started promoting a National Salvation singing campaign,<ref name="chih">Liu Ching-chih.<!--sic--> Translated by Caroline Mason. [https://books.google. |

In May 1935, the same month as the movie's {{Clarify|date=March 2023}} release, [[Lü Ji (composer)|Lü Ji]] and other leftists in [[Shanghai]] had begun an amateur choir and started promoting a National Salvation singing campaign,<ref name="chih">Liu Ching-chih.<!--sic--> Translated by Caroline Mason. [https://books.google.com/books?id=AjE3HNO7j3kC&pg=PA172 ''A Critical History of New Music in China'', p. 172]. Chinese University Press (Hong Kong), 2010.</ref> supporting mass singing associations along the lines established the year before by [[Liu Liangmo]], a Shanghai [[YMCA]] leader.<ref name="chichi" /><ref>Gallicchio, Marc. [https://books.google.com/books?id=oh3Cn3YQ0UQC&pg=PA164 ''The African American Encounter with Japan & China'', p. 164.] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180925215914/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=oh3Cn3YQ0UQC&pg=PA164 |date=25 September 2018 }} University of North Carolina Press (Chapel Hill), 2000.</ref> Although the movie {{Clarify|date=March 2023}} did not perform well enough to keep Diantong from closing, its theme song became wildly popular: [[musicologist]] [[Feng Zikai]] reported hearing it being sung by crowds in rural villages from [[Zhejiang]] to [[Hunan]] within months of its release<ref name="roo">Melvin, Sheila & al. [https://books.google.com/books?id=hwvECudSl_EC&pg=PA129 ''Rhapsody in Red: How Western Classical Music Became Chinese'', p. 129] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180925180652/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=hwvECudSl_EC&pg=PA129 |date=25 September 2018 }}. Algora Publishing (New York), 2004.</ref> and, at a performance at a Shanghai sports stadium in June 1936, Liu's chorus of hundreds was joined by its audience of thousands.<ref name="chichi" /> Although Tian Han was imprisoned for two years,<ref name="avant" /> Nie Er fled to the [[Soviet Union]], only to die en route in [[Empire of Japan|Japan]];<ref name="chih2" />{{efn|Nie actually finalized the movie's {{Clarify|date=March 2023}} music in Japan and sent it back to Diantong in Shanghai.<ref name="chichi" />}} and Liu Liangmo eventually fled to the U.S. to escape harassment from the [[Kuomintang|Nationalists]].<ref name="llm" /> The singing campaign continued to expand, particularly after the December 1936 [[Xi'an Incident]] reduced [[Nationalist government|Nationalist]] pressure against leftist movements.<ref name="chih" /> Visiting St Paul's Hospital at the [[Anglican Church of Canada|Anglican]] [[mission (Christianity)|mission]] at Guide (now [[Shangqiu]], [[Henan]]), [[W.H. Auden]] and [[Christopher Isherwood]] reported hearing a "Chee Lai!" treated as a [[hymn]] at the mission service and the same tune "set to different words" treated as a favorite song of the [[Eighth Route Army]].<ref>''[[Journey to a War]]'', cited in Chi (2007), p. 225.</ref> |

||

[[File:Earliest form of the 1935 Volunteers Marching On anthem.jpg|thumb|right|200px|The song's first appearance in print, the May or June 1935 ''[[Diantong Film Company|Diantong]] Pictorial''<ref name="dianxin">{{lang|zh|《電通半月畫報》}} [ |

[[File:Earliest form of the 1935 Volunteers Marching On anthem.jpg|thumb|right|200px|The song's first appearance in print, the May or June 1935 ''[[Diantong Film Company|Diantong]] Pictorial''<ref name="dianxin">{{lang|zh-Hant|《電通半月畫報》}} [''Diantong Pictorial''], No. 1 (16 May) or No. 2 (1 June). Diantong Film Co. (Shanghai), 1935.</ref>]] |

||

{{Listen |

|||

The Pathé recording of the march appeared prominently in [[Joris Ivens]]'s 1939 ''[[The 400 Million]]'', an English-language documentary on the war in China.<ref name="avant" /> The same year, Lee Pao-chen included it with a parallel English translation in a songbook published in the new Chinese capital [[history of Chongqing|Chongqing]];<ref name="chungking" /> this version would later be disseminated throughout the United States for children's musical education during [[World War II]] before being curtailed at the onset of the [[Cold War]].{{efn|The lyrics, which appeared in the ''Music Educators' Journal'',<ref>''Music Educators Journal''. National Association for Music Education, 1942.</ref> are sung verbatim in [[Philip Roth]]'s 1969 ''[[Portnoy's Complaint]]'', where Portnoy claims "the rhythm alone can cause my flesh to ripple" and that his elementary school teachers were already calling it the "Chinese national anthem".<ref>Roth, Philip. ''Portnoy's Complaint''. 1969.</ref>}} The ''[[New York Times]]'' published the song's [[sheet music]] on 24 December, along with an analysis by a Chinese correspondent in [[Chongqing]].<ref name="chichi" /> In exile in [[New York City]] in 1940, Liu Liangmo taught it to [[Paul Robeson]], the college-educated [[polyglot]] [[folksinger|folk-singing]] son of a [[runaway slaves|runaway slave]].<ref name=llm>Liu Liangmo. Translated by Ellen Yeung. "The America I Know". ''China Daily News'', 13–17 July 1950. Reprinted as [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=eMvaMuZkwvcC&lpg=PA207 "Paul Robeson: The People's Singer (1950)" in ''Chinese American Voices: From the Gold Rush to the Present'', pp. 207 ff.] University of California Press (Berkeley), 2006.</ref> Robeson began performing the song in [[Standard Mandarin|Chinese]] at a large concert in [[New York City]]'s [[Lewisohn Stadium]].<ref name=llm/> Reportedly in communication with the original lyricist [[Tian Han]], the pair translated it into English<ref name=avant>Liang Luo.<!--sic--> [http://www.academia.edu/1493511/International_Avant-Garde_and_the_Chinese_National_Anthem "International Avant-garde<!--sic--> and the Chinese National Anthem: Tian Han, Joris Ivens, and Paul Robeson" in ''The Ivens Magazine'', No. 16]. European Foundation Joris Ivens<!--sic--> (Nijmegen), October 2010. Accessed 22 January 2015.</ref> and recorded it in both languages as {{nowrap|'''"Chee Lai!"'''}} '''("Arise!")''' for [[Keynote Records]] in early 1941.<ref name=chichi>Chi, Robert. [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=-daxO76KmV8C&pg=PA217 "'The March of the Volunteers': From Movie Theme Song to National Anthem" in ''Re-envisioning the Chinese Revolution: The Politics and Poetics of Collective Memories in Reform China'', pp. 217 ff.] Woodrow Wilson Center Press ([[Washington, DC|Washington]]), 2007.</ref>{{efn|This song was also sometimes spelled as {{nowrap|'''Chi Lai'''}} or {{nowrap|'''Ch'i-Lai'''.}}}} Its 3-[[gramophone record|disc]] album included a booklet whose preface was written by [[Soong Ching-ling]], widow of [[Sun Yat-sen]],<ref>Deane, Hugh. ''Good Deeds & Gunboats: Two Centuries of American-Chinese Encounters'', p. 169. China Books & Periodicals (Chicago), 1990.</ref> and its initial proceeds were donated to the Chinese resistance.<ref name="roo" /> Robeson gave further live performances at benefits for the [[China Aid Council]] and [[United China Relief]], although he gave the stage to Liu and the Chinese themselves for the song's performance at their sold-out concert at [[Washington, DC|Washington]]'s [[Uline Arena]] on 24 April 1941.<ref name=blow>Gellman, Erik S. [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=vYZPIE7UKggC&pg=PA136 ''Death Blow to Jim Crow: The National Negro Congress and the Rise of Militant Civil Rights'', pp. 136]. University of North Carolina Press (Chapel Hill), 2012. ISBN 9780807835319.</ref>{{efn|The [[China Aid Council|Washington Committee for Aid to China]] had previously booked [[Constitution Hall]] but been blocked by the [[Daughters of the American Revolution]] owing to Robeson's race. The indignation was great enough that [[Franklin Delano Roosevelt|President Roosevelt]]'s [[First Lady of the United States|wife]] [[Eleanor Roosevelt|Eleanor]] and [[Hu Shih|the Chinese ambassador]] joined as sponsors, ensuring that the Uline Arena would accept and [[desegregation|desegregate]] for the single concert. When the organizers offered generous terms to the [[National Negro Congress]] to help fill the larger venue, however, these sponsors withdrew and attempted to cancel the event, owing to the NNC's [[American Communism|Communist]] ties<ref>Robeson, Paul Jr. [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=MzFhJ5v0TL0C&pg=PA25 ''The Undiscovered Paul Robeson: Quest for Freedom, 1939–1976'', pp. 25 f]. John Wiley & Sons (Hoboken), 2010.</ref> and Mrs. Roosevelt's personal history with the [[John P. Davis|NNC's founder]].<ref name=blow/>}} Following the [[attack on Pearl Harbor]] and beginning of the [[Pacific War]], the march was played locally in [[British India|India]], [[British Singapore|Singapore]], and other locales in [[South-East Asian theatre of World War II|Southeast Asia]];<ref name="avant" /> the Robeson recording was played frequently on [[UK|British]], American, and [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] radio;<ref name="avant" /> and a [[cover version]] performed by the [[Army Air Force Orchestra]]<ref>Eagan, Daniel. [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=deq3xI8OmCkC&pg=PA390 ''America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry'', pp. 390 f.] Continuum International (New York), 2010.</ref> appears as the introductory music to [[Frank Capra]]'s 1944 [[propaganda film]] ''[[The Battle of China]]'' and again during its coverage of the Chinese response to the [[Nanking Massacre|Rape of Nanking]]. |

|||

|filename = March of the Volunteers (Pathe Records - 1935).ogg |

|||

|title = March of the Volunteers (Pathé Records) |

|||

|description = |

|||

|pos = |

|||

}} |

|||

The [[Pathé News|Pathé]] recording of the march appeared prominently in [[Joris Ivens]]'s 1939 ''[[The 400 Million]]'', an English-language documentary on the war in China.<ref name="avant" /> The same year, Lee Pao-chen included it with a parallel English translation in a [[Song book|songbook]] published in the new [[Historical capitals of China|Chinese capital]] [[history of Chongqing|Chongqing]];<ref name="chungking" /> this version would later be disseminated throughout the [[United States]] for children's musical education during [[World War II]] before being curtailed at the onset of the [[Cold War]].{{efn|The lyrics, which appeared in the ''Music Educators' Journal'',<ref>''Music Educators Journal''. National Association for Music Education, 1942.</ref> are sung verbatim in [[Philip Roth]]'s 1969 ''[[Portnoy's Complaint]]'', where Portnoy claims "the rhythm alone can cause my flesh to ripple" and that his elementary school teachers were already calling it the "Chinese national anthem".<ref>Roth, Philip. ''Portnoy's Complaint''. 1969.</ref>}} The ''[[New York Times]]'' published the song's [[sheet music]] on 24 December, along with an analysis by a Chinese [[correspondent]] in [[Chongqing]].<ref name="chichi" /> In exile in [[New York City]] in 1940, Liu Liangmo taught it to [[Paul Robeson]], the college-educated [[polyglot]] [[Folk music|folk-singing]] son of a [[runaway slaves|runaway slave]].<ref name=llm>Liu Liangmo. Translated by Ellen Yeung. "The America I Know". ''China Daily News'', 13–17 July 1950. Reprinted as [https://books.google.com/books?id=eMvaMuZkwvcC&pg=PA207 "Paul Robeson: The People's Singer (1950)" in ''Chinese American Voices: From the Gold Rush to the Present'', pp. 207 ff.] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170830013336/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=eMvaMuZkwvcC&lpg=PA207 |date=30 August 2017 }} University of California Press (Berkeley), 2006.</ref> Robeson began performing the song in [[Standard Mandarin|Chinese]] at a large concert in [[New York City]]'s [[Lewisohn Stadium]].<ref name=llm/> Reportedly in communication with the original lyricist [[Tian Han]], the pair translated it into English<ref name=avant>Liang Luo.<!--sic--> [https://www.academia.edu/1493511/International_Avant-Garde_and_the_Chinese_National_Anthem "International Avant-garde<!--sic--> and the Chinese National Anthem: Tian Han, Joris Ivens, and Paul Robeson" in ''The Ivens Magazine'', No. 16] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190306150508/https://www.academia.edu/1493511/International_Avant-Garde_and_the_Chinese_National_Anthem |date=6 March 2019 }}. European Foundation Joris Ivens<!--sic--> (Nijmegen), October 2010. Accessed 22 January 2015.</ref> and recorded it in both languages as {{nowrap|"Chee Lai!"}} ("Arise!") for [[Keynote Records]] in early 1941.<ref name=chichi>Chi, Robert. [https://books.google.com/books?id=-daxO76KmV8C&pg=PA217 "'The March of the Volunteers': From Movie Theme Song to National Anthem" in ''Re-envisioning the Chinese Revolution: The Politics and Poetics of Collective Memories in Reform China'', pp. 217 ff.] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170830013614/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=-daxO76KmV8C&pg=PA217 |date=30 August 2017 }} Woodrow Wilson Center Press (Washington, DC), 2007.</ref>{{efn|This song was also sometimes spelled as {{nowrap|''Chi Lai''}} or {{nowrap|''Ch'i-Lai''.}}}} Its 3-[[gramophone record|disc]] album included a booklet whose preface was written by [[Soong Ching-ling]], widow of [[Sun Yat-sen]],<ref>Deane, Hugh. ''Good Deeds & Gunboats: Two Centuries of American-Chinese Encounters'', p. 169. China Books & Periodicals (Chicago), 1990.</ref> and its initial proceeds were donated to the Chinese resistance.<ref name="roo" /> Robeson gave further live performances at benefits for the [[China Aid Council]] and [[United China Relief]], although he gave the stage to Liu and the Chinese themselves for the song's performance at their sold-out concert at [[Washington, DC|Washington]]'s [[Uline Arena]] on 24 April 1941.<ref name=blow>Gellman, Erik S. [https://books.google.com/books?id=vYZPIE7UKggC&pg=PA136 ''Death Blow to Jim Crow: The National Negro Congress and the Rise of Militant Civil Rights'', pp. 136] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170830005424/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=vYZPIE7UKggC&pg=PA136 |date=30 August 2017 }}. University of North Carolina Press (Chapel Hill), 2012. {{ISBN|9780807835319}}.</ref>{{efn|The [[China Aid Council|Washington Committee for Aid to China]] had previously booked [[Constitution Hall]] but been blocked by the [[Daughters of the American Revolution]] owing to Robeson's race. The indignation was great enough that [[Franklin Delano Roosevelt|President Roosevelt]]'s [[First Lady of the United States|wife]] [[Eleanor Roosevelt|Eleanor]] and [[Hu Shih|the Chinese ambassador]] joined as sponsors, ensuring that the Uline Arena would accept and [[Desegregation in the United States|desegregate]] for the single concert. When the organizers offered generous terms to the [[National Negro Congress]] to help fill the larger venue, however, these sponsors withdrew and attempted to cancel the event, owing to the NNC's [[American Communism|Communist]] ties<ref>Robeson, Paul Jr. [https://books.google.com/books?id=MzFhJ5v0TL0C&pg=PA25 ''The Undiscovered Paul Robeson: Quest for Freedom, 1939–1976'', pp. 25 f] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170830004858/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=MzFhJ5v0TL0C&pg=PA25 |date=30 August 2017 }}. John Wiley & Sons (Hoboken), 2010.</ref> and Mrs. Roosevelt's personal history with the [[John P. Davis|NNC's founder]].<ref name=blow/>}} Following the [[attack on Pearl Harbor]] and beginning of the [[Pacific War]], the march was played locally in [[British India|India]], [[British Singapore|Singapore]], and other locales in [[South-East Asian theatre of World War II|Southeast Asia]];<ref name="avant" /> the Robeson recording was played frequently on [[UK|British]], American, and [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] radio;<ref name="avant" /> and a [[cover version]] performed by the [[Army Air Force Orchestra]]<ref>Eagan, Daniel. [https://books.google.com/books?id=deq3xI8OmCkC&pg=PA390 ''America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry'', pp. 390 f.] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181201135057/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=deq3xI8OmCkC&pg=PA390 |date=1 December 2018 }} Continuum International (New York), 2010.</ref> appears as the introductory music to [[Frank Capra]]'s 1944 [[propaganda film]] ''[[The Battle of China]]'' and again during its coverage of the Chinese response to the [[Nanking Massacre|Rape of Nanking]]. |

|||

The "March of the Volunteers" was used as the Chinese national anthem for the first time at the [[World Peace Council#Paris and Prague 1949|World Peace Conference]] in April 1949. Originally intended for [[Paris]], French authorities refused so many visas for its delegates that a parallel conference was held in [[Prague]], [[Czechoslovak Socialist Republic|Czechoslovakia]].<ref name="santi">Santi, Rainer. [http://santibox.ch/Peace/Peacemaking.html#5.%20A%20New%20Start "100 Years of Peace Making: A History of the International Peace Bureau and Other International Peace Movement Organisations<!--sic--> and Networks" in ''Pax Förlag''] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190321044904/http://www.santibox.ch/Peace/Peacemaking.html#5.%20A%20New%20Start |date=21 March 2019 }}. International Peace Bureau, January 1991.</ref> At the time, [[Beijing]] had recently come under the control of the [[Chinese Communist Party|Chinese Communists]] in the [[Chinese Civil War]] and its delegates attended the Prague conference in China's name. There was controversy over the third line, "The Chinese nation faces its greatest peril", so the writer [[Guo Moruo]] changed it for the event to "The Chinese nation has arrived at its moment of emancipation". The song was personally performed by Paul Robeson.<ref name=avant/> |

|||

In June, a committee was set up by the [[Chinese Communist Party]] to decide on an official national anthem for the soon-to-be declared People's Republic of China. By the end of August, the committee had received 632 entries totaling 694 different sets of scores and lyrics.<ref name=chichi/> The ''March of the Volunteers'' was suggested by the [[Chinese painting#Modern painting|painter]] [[Xu Beihong]]<ref>[[Liao Jingwen]]. Translated by Zhang Peiji. ''Xu Beihong: Life of a Master Painter'', pp. 323 f. Foreign Language Press (Beijing), 1987.</ref> and supported by [[Zhou Enlai]].<ref name=chichi/> Opposition to its use centered on the third line, as "The Chinese people face their greatest peril" suggested that China continued to face difficulties. Zhou replied, "We still have [[imperialism|imperialist]] enemies in front of us. The more we progress in development, the more the imperialists will hate us, seek to undermine us, attack us. Can you say that we won't be in peril?" His view was supported by [[Mao Zedong]] and, on 27 September 1949, the song became the provisional national anthem, just days before the founding of the [[People's Republic of China|People's Republic]].<ref name=provo>[[s:Resolution on the Capital, Calendar, National Anthem and National Flag of the People's Republic of China|Resolution on the Capital, Calendar, National Anthem, and National Flag of the People's Republic of China]]. 1st [[Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference]] (Beijing), 27 September 1949. Hosted at [[s:Main Page|Wikisource]].</ref> The highly fictionalized [[biopic]] ''[[Nie Er (film)|Nie Er]]'' was produced in 1959 for its 10th anniversary; for its 50th in 1999, ''[[The National Anthem (film)|The National Anthem]]'' retold the story of the anthem's composition from [[Tian Han]]'s point of view.<ref name=chichi/> |

|||

The "March of the Volunteers" was used as the Chinese national anthem for the first time at the [[World Peace Council#Paris and Prague 1949|World Peace Conference]] in April 1949. Originally intended for [[Paris]], French authorities refused so many visas for its delegates that a parallel conference was held in [[Prague]], [[Czechoslovakia]].<ref name="santi">Santi, Rainer. [http://santibox.ch/Peace/Peacemaking.html#5.%20A%20New%20Start "100 Years of Peace Making: A History of the International Peace Bureau and Other International Peace Movement Organisations<!--sic--> and Networks" in ''Pax Förlag'']. International Peace Bureau, January 1991.</ref> At the time, [[Beijing]] had recently come under the control of the [[Chinese Communist Party|Chinese Communists]] in the [[Chinese Civil War]] and its delegates attended the Prague conference in China's name. There was controversy over the line "The Chinese people faces their greatest peril", so the writer [[Guo Moruo]] changed it for the event to "The Chinese people have come to their moment of emancipation". The song was personally performed by Paul Robeson.<ref name=avant/> |

|||

In June, a committee was set up by the [[Communist Party of China]] to decide on an official national anthem for the soon-to-be declared People's Republic of China. By the end of August, the committee had received 632 entries totaling 694 different sets of scores and lyrics.<ref name=chichi/> The ''March of the Volunteers'' was suggested by the [[Chinese painting#Modern painting|painter]] [[Xu Beihong]]<ref>Liao Jingwen. Translated by Zhang Peiji. ''Xu Beihong: Life of a Master Painter'', pp. 323 f. Foreign Language Press (Beijing), 1987.</ref> and supported by [[Zhou Enlai]].<ref name=chichi/> Opposition to its use centered on the third line, suggesting that China continued to face difficulties. Zhou replied: "We still have [[imperialism|imperialist]] enemies in front of us. The more we progress in development, the more the imperialists will hate us, seek to undermine us, attack us. Can you say that we won't be in peril?" His view was supported by [[Mao Zedong]] and, on 27 September 1949, the song became the provisional national anthem, just days before the founding of the [[People's Republic of China|People's Republic]].<ref name=provo>[[s:Resolution on the Capital, Calendar, National Anthem and National Flag of the People's Republic of China|Resolution on the Capital, Calendar, National Anthem, and National Flag of the People's Republic of China]]. 1st [[Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference]] (Beijing), 27 September 1949. Hosted at [[s:Main Page|Wikisource]].</ref> The highly fictionalized [[biopic]] ''[[Nie Er (film)|Nie Er]]'' was produced in 1959 for its 10th anniversary; for its 50th in 1999, ''[[The National Anthem (film)|The National Anthem]]'' retold the story of the anthem's composition from [[Tian Han]]'s point of view.<ref name=chichi/> |

|||

Although the song had been popular among [[Kuomintang|Nationalists]] during the [[Second Sino-Japanese War|war against Japan]], its performance was then banned in the territories of the [[Republic of China]] until the 1990s.{{citation needed |date = April 2014}} |

Although the song had been popular among [[Kuomintang|Nationalists]] during the [[Second Sino-Japanese War|war against Japan]], its performance was then banned in the territories of the [[Republic of China]] until the 1990s.{{citation needed |date = April 2014}} |

||

[[File:Sons and Daughters in a Time of Storm.ogv|thumb|280px|right| |

[[File:Sons and Daughters in a Time of Storm.ogv|thumb|280px|right|A clip from the film ''[[Children of Troubled Times]]'' (1935), featuring "March of the Volunteers".]] |

||

The 1966 ''[[People's Daily]]'' article condemning [[Tian Han]]'s 1961 [[allegory|allegorical]] [[Peking opera]] ''[[Xie Yaohuan]]'' was one of the opening salvos of the [[Cultural Revolution]],<ref name="wagner">Wagner, Rudolf G. [https://books.google. |

The 1 February 1966 ''[[People's Daily]]'' article condemning [[Tian Han]]'s 1961 [[allegory|allegorical]] [[Peking opera]] ''[[Xie Yaohuan]]'' as a "big poisonous weed"<ref>{{cite journal|journal=Current Background|publisher=American Consulate General|place=Hong Kong|date=30 March 1966|issue=784|title=T'ien Han and his Play Hsieh Yao-huan|page=1}}</ref> was one of the opening salvos of the [[Cultural Revolution]],<ref name="wagner">Wagner, Rudolf G. [https://books.google.com/books?id=7zFiHwkpo88C&dq=Xie+Yaohuan&pg=PA80 "Tian Han's Peking Opera ''Xie Yaohuan'' (1961)" in ''The Contemporary Chinese Historical Drama: Four Studies'', pp. 80 ff.] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181119132620/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=7zFiHwkpo88C&lpg=PA137&ots=NuM7CzzEhM&dq=Xie%20Yaohuan&pg=PA80#v=onepage&q=Xie%20Yaohuan&f=false |date=19 November 2018 }} University of California Press (Berkeley), 1990. {{ISBN|9780520059542}}</ref> during which he was imprisoned and his words forbidden to be sung. As a result, there was a time when "[[The East Is Red (song)|The East Is Red]]" served as the PRC's unofficial anthem.{{efn|Such use continued some time after the "March of the Volunteers"'s nominal rehabilitation in 1969.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=f5UbE-D5N_cC&pg=PA361 |title="Broadcasting and Politics Spread Across the World" in ''Television: Critical Concepts in Media and Cultural Studies'', Vol. I, p. 361. |isbn=9780415255035 |access-date=23 May 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304092026/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=f5UbE-D5N_cC&pg=PA361 |archive-date=4 March 2016 |url-status=live|last1=Miller |first1=Toby |year=2003 |publisher=Taylor & Francis }}</ref>}} Following the [[9th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party|9th National Congress]], "The March of the Volunteers" began to be played once again from the 20th [[National Day (PRC)|National Day]] Parade in 1969, although performances were solely instrumental. Tian Han died in prison in 1968, but Paul Robeson continued to send the royalties from his American recordings of the song to Tian's family.<ref name=avant/> |

||

The |

The anthem was restored by the [[5th National People's Congress]] on 5 March 1978,<ref name=zhstate/> but with rewritten lyrics including references to the Chinese Communist Party, communism, and [[Mao Zedong|Chairman Mao]]. Following Tian Han's posthumous [[rehabilitation (Soviet)|rehabilitation]] in 1979<ref name=chichi/> and [[Deng Xiaoping]]'s consolidation of power over [[Hua Guofeng]], the [[National People's Congress]] resolved to restore Tian Han's original verses to the march and to elevate its status, making it the country's official national anthem on 4 December 1982.<ref name="zhstate">{{lang|zh|[http://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2005-05/24/content_2615210.htm 《中华人民共和国国歌》]}} [''Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó Guógē'', "National Anthem of the People's Republic of China"]. [[State Council of the People's Republic of China]] (Beijing), 2015. Accessed 21 January 2015. {{in lang|zh}}</ref><ref name="state">[http://english.gov.cn/archive/china_abc/2014/08/27/content_281474983873455.htm "National Anthem"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171204222856/http://english.gov.cn/archive/china_abc/2014/08/27/content_281474983873455.htm |date=4 December 2017 }}. [[State Council of the People's Republic of China]] (Beijing), 26 August 2014. Accessed 21 January 2015.</ref> |

||

[[File:March of the Volunteers.png|thumb |

[[File:March of the Volunteers.png|thumb|200px|Sheet music from Appendix 4 of [[Macau]]'s Law No.5/1999]] |

||

The use of the anthem in the [[Macau Special Administrative Region]] is particularly governed by Law №5/1999, which was enacted on 20 December 1999. Article 7 of the law requires that the anthem be accurately performed pursuant to the sheet music in its Appendix 4 and prohibits the lyrics from being altered. Under Article 9, willful alteration of the music or lyrics is [[criminal law|criminally]] punishable by imprisonment of up to 3 years or up to 360 [[day-fine]]s<ref>{{lang|zh|[[s:zh:第5/1999號法律|第5/1999號法律 國旗、國徽及國歌的使用及保護]]}} [''Dì 5/1999 Háo Fǎlǜ: Guóqí, Guóhuī jí Guógē de Shǐyòng jí Bǎohù'', "Law №5/1999: The Use and Protection of the [[National Flag of the People's Republic of China|National Flag]], [[National Emblem of the People's Republic of China|National Emblem]], and National Anthem"]. [[Legislative Assembly of Macau|Legislative Assembly]] (Macao), 20 December 1999. Hosted at the [[s:zh:Main Page|Chinese Wikisource]]. {{zh icon}}</ref><ref>{{lang|pt|[[s:pt:Lei de Macau 5 de 1999|Lei n.º 5/1999: Utilização e protecção da bandeira, emblema e hino nacionais]]}} ["Law №5/1999: The Use and Protection of the [[National Flag of the People's Republic of China|National Flag]], [[National Emblem of the People's Republic of China|Emblem]], and Anthem"]. [[Legislative Assembly of Macau|Legislative Assembly]] (Macao), 20 December 1999. Hosted at the [[s:pt:Main Page|Portuguese Wikisource]]. {{pt icon}}</ref> and, although both [[Chinese language|Chinese]] and [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]] are official languages of the region, the provided sheet music has its lyrics only in [[Chinese characters|Chinese]]. There are no analogous laws in [[mainland China]] or in [[Hong Kong]], where an English translation of the anthem is used for important events at the [[University of Hong Kong]].{{citation needed |date = January 2015}} |

|||

The anthem's status was enshrined as an amendment to the [[Constitution of the People's Republic of China]] on 14 March 2004.<ref name="constitution">[[s:Constitution of the People's Republic of China|Constitution of the People's Republic of China]], [[s:Constitution of the People's Republic of China#AMENDMENT FOUR|Amendment IV, §31]]. [[10th National People's Congress]] (Beijing), 14 March 2004. Hosted at [[s:Main Page|Wikisource]].</ref><ref name="zhstate" /> |

|||

Nonetheless, the Chinese National Anthem in [[Standard Mandarin|Mandarin]] now forms a mandatory part of public secondary education in Hong Kong as well.<ref name=hohoho>Ho (2011), [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=7VieYfjWRV0C&lpg=PA36 p. 36.]</ref> The local government issued a circular in May 1998 requiring government-funded schools to perform [[Flag of the People's Republic of China|flag]]-raising ceremonies involving the singing of the "March of the Volunteers" on particular days: the first day of school, the "[[Open day (school)|open day]]", [[National Day (PRC)|National Day]] (1 October), New Year's (1 January), the "sport day", [[Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Establishment Day|Establishment Day]] (1 July), the graduation ceremony, and for some other school-organized events; the circular was also send to the SAR's private schools.<ref>Ho (2011), [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=7VieYfjWRV0C&pg=PA89 pp. 89 ff.]</ref><ref>Lee, Wing On.<!-- sic --> [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=btkuYUgXLRIC&pg=PA36 "The Development of Citizenship Education Curriculum in Hong Kong after 1997: Tensions between National Identity and Global Citizenship" in ''Citizenship Curriculum in Asia and the Pacific'', p. 36.] Comparative Education Research Centre (Hong Kong), 2008.</ref> The official policy was long ignored, but—following massive and unexpected public demonstrations in 2003 against proposed anti-subversion laws—the ruling was reïterated in 2004<ref>[https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=pjc3zF0hI6wC&pg=PA57 "Positioning at the Margins" in ''Diasporic Histories: Cultural Archives of Chinese Transnationalism'', pp. 57 f.]</ref><ref name="vicky" /> and most schools now hold such ceremonies at least once or twice a year.<ref>Mathews, Gordon & al. [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=UqmFL5d-bAAC&pg=PA89 ''Hong Kong, China: Learning to Belong to a Nation'', p. 89.] Routledge (Abingdon), 2008. ISBN 0415426545.</ref> From [[National Day (PRC)|National Day]] in 2004, as well, Hong Kong's local television networks—[[Asia Television|aTV]], [[TVB]], and [[Cable TV Hong Kong|CTVHK]]—have also been required to preface their evening news with government-prepared<ref>''Hong Kong 2004: Education'': [http://www.yearbook.gov.hk/2004/en/07_11.htm "Committee on the Promotion of Civic Education"]. Government Yearbook (Hong Kong), 2015. Accessed 25 January 2015.</ref> promotional videos including the national anthem in Mandarin.<ref name=vicky>Vickers, Edward. [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=QwXgYeQRVHsC&pg=PA94 "Learning to Love the Motherland: 'National Education' in Post-Retrocession Hong Kong" in ''Designing History in East Asian Textbooks: Identity Politics and Transnational Aspirations'', p. 94]. Routledge (Abingdon), 2011. ISBN 9780415602525.</ref> Initially a pilot program planned for a few months,<ref name="mrwong" /> it has continued ever since. Despite discomforting some locals who view it as "propaganda",<ref name="mrwong">Wong, Martin. [http://www.scmp.com/article/472472/national-anthem-be-broadcast-news "National Anthem To Be Broadcast before News".] ''South China Morning Post'' (Hong Kong), 1 October 2004.</ref><ref>Luk, Helen. [http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1238125/posts "Chinese National Anthem Video Draws Fire from Hong Kong People"]. Associated Press, 7 October 2004.</ref><ref>Jones, Carol. [http://www.lse.ac.uk/asiaResearchCentre/countries/taiwan/TaiwanProgramme/Journal/JournalContents/TCP5Jones.pdf "Lost in China? Mainlandisation<!--sic--> and Resistance in Post-1997 Hong Kong" in ''Taiwan in Comparative Perspective'', Vol. 5, pp. 28–ff.] London School of Economics (London), July 2014.</ref> general polling has shown it has markedly improved Hong Kongers' pride and affection towards the national anthem.<ref>Mathews & al. (2008), [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=UqmFL5d-bAAC&pg=PA104 p. 104.]</ref> |

|||

On 1 September 2017, ''The Law of the National Anthem of the People's Republic of China'', which protects the anthem by law, was passed by the [[Standing Committee of the National People's Congress]] and took effect one month later. The anthem is considered to be a [[national symbol]] of China. The anthem should be performed or reproduced especially at celebrations of [[Public holidays in China|national holidays and anniversaries]], as well as sporting events. Civilians and organizations should pay respect to the anthem by standing and singing in a dignified manner.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/fujian/site1/20170901/1078d2c86a3d1b138cce01.pdf|script-title=zh:中华人民共和国国歌法|trans-title=The Law of the National Anthem of the People's Republic of China|language=zh|date=1 September 2017|publisher=The National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China|access-date=6 December 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170901164600/http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/fujian/site1/20170901/1078d2c86a3d1b138cce01.pdf|archive-date=1 September 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref> Personnel of the [[People's Liberation Army]], the [[People's Armed Police]] and the [[People's Police of the People's Republic of China|People's Police]] of the [[Ministry of Public Security (China)|Ministry of Public Security]] salute when not in formation when the anthem is played, the same case for members of the [[Young Pioneers of China]] and PLA veterans. |

|||

==Special administrative regions== |

|||

The anthem was played during the [[Hong Kong handover ceremony|handover of Hong Kong]] from the [[United Kingdom]] in 1997<ref>Ho Wai-chung. [https://books.google.com/books?id=7VieYfjWRV0C&pg=PA69 ''School Music Education and Social Change in Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan'', p. 69.] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190103211849/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=7VieYfjWRV0C&pg=PA69 |date=3 January 2019 }} Koninklijke Brill NV (Leiden), 2011. {{ISBN|9789004189171}}.</ref> and during the [[handover of Macau]] from [[Portugal]] in 1999. It was adopted as part of Annex III of the [[Basic Law of Hong Kong]], taking effect on 1 July 1997,<ref name=hk>[[s:Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region|Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region]], [[s:Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region/Annex III|Annex III]]. [[7th National People's Congress]] (Beijing), 4 April 1990. Hosted at [[s:Main Page|Wikisource]].</ref> and as part of Annex III of the [[Basic Law of Macau]], taking effect on 20 December 1999.<ref name="macao">[[s:Basic Law of the Macao Special Administrative Region|Basic Law of the Macao Special Administrative Region]], [[s:Basic Law of the Macao Special Administrative Region/Annex III|Annex III]]. [[8th National People's Congress]] (Beijing), 31 March 1993. Hosted at [[s:Main Page|Wikisource]].</ref> |

|||

=== Macau === |

|||

The use of the anthem in the [[Macau Special Administrative Region]] is particularly governed by Law No.5/1999, which was enacted on 20 December 1999. Article 7 of the law requires that the anthem be accurately performed pursuant to the sheet music in its Appendix 4 and prohibits the lyrics from being altered. Under Article 9, willful alteration of the music or lyrics is [[criminal law|criminally]] punishable by imprisonment of up to two years or up to 360 [[day-fine]]s<ref>{{lang|zh|[[s:zh:第5/1999號法律|第5/1999號法律 國旗、國徽及國歌的使用及保護]]}} [''Dì 5/1999 Háo Fǎlǜ: Guóqí, Guóhuī jí Guógē de Shǐyòng jí Bǎohù'', "Law №5/1999: The Use and Protection of the [[National Flag of the People's Republic of China|National Flag]], [[National Emblem of the People's Republic of China|National Emblem]], and National Anthem"]. [[Legislative Assembly of Macau|Legislative Assembly]] (Macao), 20 December 1999. Hosted at the [[s:zh:Main Page|Chinese Wikisource]]. {{in lang|zh}}</ref><ref>{{lang|pt|[[s:pt:Lei de Macau 5 de 1999|Lei n.º 5/1999: Utilização e protecção da bandeira, emblema e hino nacionais]]}} ["Law №5/1999: The Use and Protection of the [[National Flag of the People's Republic of China|National Flag]], [[National Emblem of the People's Republic of China|Emblem]], and Anthem"]. [[Legislative Assembly of Macau|Legislative Assembly]] (Macao), 20 December 1999. Hosted at the [[s:pt:Main Page|Portuguese Wikisource]]. {{in lang|pt}}</ref> and, although both [[Chinese language|Chinese]] and [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]] are official languages of the region, the provided sheet music has its lyrics only in [[Chinese characters|Chinese]]. Mainland China has also passed a similar law in 2017.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://english.www.gov.cn/news/top_news/2017/10/01/content_281475895755376.htm|title=China's national anthem law takes effect|website=english.www.gov.cn|access-date=14 January 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200114073754/http://english.www.gov.cn/news/top_news/2017/10/01/content_281475895755376.htm|archive-date=14 January 2020|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

=== Hong Kong === |

|||

Nonetheless, the Chinese National Anthem in [[Standard Mandarin|Mandarin]] now forms a mandatory part of [[Secondary education in Hong Kong|public secondary education in Hong Kong]] as well.<ref name="hohoho">Ho (2011), [https://books.google.com/books?id=7VieYfjWRV0C&pg=PA36 p. 36.] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171107020435/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=7VieYfjWRV0C&lpg=PA36 |date=7 November 2017 }}</ref> The local government issued a circular in May 1998 requiring government-funded schools to perform [[Flag of the People's Republic of China|flag]]-raising ceremonies involving the singing of the "March of the Volunteers" on particular days: the first day of school, the "[[Open day (school)|open day]]", [[National Day (PRC)|National Day]] (1 October), New Year's (1 January), the "sport day", [[Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Establishment Day|Establishment Day]] (1 July), the [[Graduation|graduation ceremony]], and for some other school-organized events; the circular was also sent to the SAR's [[private school]]s.<ref>Ho (2011), [https://books.google.com/books?id=7VieYfjWRV0C&pg=PA89 pp. 89 ff.] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171107011421/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=7VieYfjWRV0C&pg=PA89 |date=7 November 2017 }}</ref><ref>Lee, Wing On.<!-- sic --> [https://books.google.com/books?id=btkuYUgXLRIC&pg=PA36 "The Development of Citizenship Education Curriculum in Hong Kong after 1997: Tensions between National Identity and Global Citizenship" in ''Citizenship Curriculum in Asia and the Pacific'', p. 36.] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171107005406/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=btkuYUgXLRIC&pg=PA36 |date=7 November 2017 }} Comparative Education Research Centre (Hong Kong), 2008.</ref> The official policy was long ignored, but—following massive and unexpected public demonstrations in 2003 against proposed anti-subversion laws—the ruling was reiterated in 2004<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pjc3zF0hI6wC&pg=PA57 |title="Positioning at the Margins" in ''Diasporic Histories: Cultural Archives of Chinese Transnationalism'', pp. 57 f. |isbn=9789622090804 |access-date=23 May 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171107033020/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=pjc3zF0hI6wC&pg=PA57 |archive-date=7 November 2017 |url-status=live|last1=Riemenschnitter |first1=Andrea |last2=Madsen |first2=Deborah L. |date=August 2009 |publisher=Hong Kong University Press }}</ref><ref name="vicky" /> and, by 2008, most schools were holding such ceremonies at least once or twice a year.<ref>Mathews, Gordon & al. [https://books.google.com/books?id=UqmFL5d-bAAC&pg=PA89 ''Hong Kong, China: Learning to Belong to a Nation'', p. 89.] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171107033251/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=UqmFL5d-bAAC&pg=PA89 |date=7 November 2017 }} Routledge (Abingdon), 2008. {{ISBN|0415426545}}.</ref> From [[National Day (PRC)|National Day]] in 2004, as well, Hong Kong's [[Local programming|local television networks]] have also been required to preface their evening news with government-prepared<ref>''Hong Kong 2004: Education'': [http://www.yearbook.gov.hk/2004/en/07_11.htm "Committee on the Promotion of Civic Education"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190704092855/https://www.yearbook.gov.hk/2004/en/07_11.htm |date=4 July 2019 }}. Government Yearbook (Hong Kong), 2015. Accessed 25 January 2015.</ref> promotional videos including the national anthem in Mandarin.<ref name="vicky">Vickers, Edward. [https://books.google.com/books?id=QwXgYeQRVHsC&pg=PA94 "Learning to Love the Motherland: 'National Education' in Post-Retrocession Hong Kong" in ''Designing History in East Asian Textbooks: Identity Politics and Transnational Aspirations'', p. 94] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171107023017/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=QwXgYeQRVHsC&pg=PA94 |date=7 November 2017 }}. Routledge (Abingdon), 2011. {{ISBN|9780415602525}}.</ref> Initially a pilot program planned for a few months,<ref name="mrwong" /> it has continued ever since. Viewed by many as propaganda,<ref name="mrwong">Wong, Martin. [http://www.scmp.com/article/472472/national-anthem-be-broadcast-news "National Anthem To Be Broadcast before News".] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190816101148/https://www.scmp.com/article/472472/national-anthem-be-broadcast-news |date=16 August 2019 }} ''South China Morning Post'' (Hong Kong), 1 October 2004.</ref><ref>Luk, Helen. [http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1238125/posts "Chinese National Anthem Video Draws Fire from Hong Kong People"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160125225011/http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1238125/posts |date=25 January 2016 }}. Associated Press, 7 October 2004.</ref><ref>Jones, Carol. [http://www.lse.ac.uk/asiaResearchCentre/countries/taiwan/TaiwanProgramme/Journal/JournalContents/TCP5Jones.pdf "Lost in China? Mainlandisation<!--sic--> and Resistance in Post-1997 Hong Kong" in ''Taiwan in Comparative Perspective'', Vol. 5, pp. 28–ff.] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304062021/http://www.lse.ac.uk/asiaResearchCentre/countries/taiwan/TaiwanProgramme/Journal/JournalContents/TCP5Jones.pdf |date=4 March 2016 }} London School of Economics (London), July 2014.</ref> even after a sharp increase in support in the preceding four years, by 2006, the majority of [[Hongkongers]] remained neither proud nor fond of the anthem.<ref>Mathews & al. (2008), [https://books.google.com/books?id=UqmFL5d-bAAC&pg=PA104 p. 104.] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171107013015/https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=UqmFL5d-bAAC&pg=PA104 |date=7 November 2017 }}</ref> On 4 November 2017, the [[Standing Committee of the National People's Congress]] decided to insert a Chinese National Anthem Law into the Annex III of the [[Basic Law of Hong Kong]], which would make it illegal to insult or not show sufficient respect to the Chinese national anthem. On 4 June 2020, the [[National Anthem Bill]] was passed in Hong Kong after being approved by the [[Legislative Council]].<ref>{{cite news |title=Chaos at Hong Kong's legislature as lawmakers battle for control of committee |url=https://hongkongfp.com/2020/05/08/chaos-at-hong-kongs-legislature-as-lawmakers-battle-for-control-of-committee-as-democrats-ejected/ |access-date=4 June 2020 |work=HKFP|date=5 May 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Hong Kong passes bill criminalising disrespect of Chinese national anthem |url=https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-04/hong-kong-legislature-passes-national-anthem-bill-amid-protests/12323024 |access-date=4 June 2020 |work=ABC News |date=4 June 2020}}</ref> |

|||

==Tune== |

==Tune== |

||

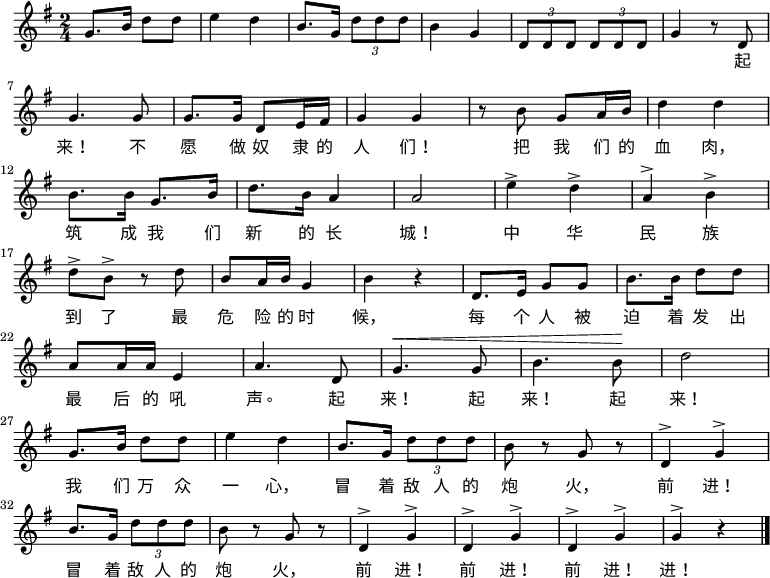

<score vorbis="1"> |

|||

{{multi-listen start}} |

|||

\relative g' { |

|||

{{multi-listen item|filename=March of the Volunteers instrumental.ogg|title="March of the Volunteers"|description=A recording of the [[United States Navy Band]] performing the "March of the Volunteers". |

|||

\key g \major \time 2/4 |

|||

|format=[[Ogg]]}} |

|||

g8. b16 d8 d8 \bar "|" e4 d4 \bar "|" b8. g16 \times 2/3 {d'8 d d} \bar "|" b4 g4 \bar "|" \times 2/3 {d8 d d} \times 2/3 {d8 d d} \bar "|" g4 r8 d8 \bar "|" \break |

|||

{{multi-listen end}} |

|||

g4. g8 \bar "|" g8. g16 d8 e16 fis16 \bar "|" g4 g4 \bar "|" r8 b8 g8 a16 b16 \bar "|" d4 d4 \bar "|" \break |

|||

A 1939 bilingual songbook which included the song called it "a good example of... copy[ing] the good points from Western music without impairing or losing [[Chinese music|our own national color]]".<ref name=chungking>Lee Pao-chen. ''China's Patriots Sing''. The China Information Publishing Co. ([[Chongqing|Chungking]]), 1939.</ref> Nie's piece is a [[March (music)|march]], a Western form, opening with a [[bugle call]] and a motif (with which it also closes) based on an ascending fourth interval from D to G inspired by [[The Internationale in Chinese|"The ''Internationale''"]].<ref name=hojo/> Its rhythmic patterns of triplets, accented downbeats, and syncopation and use (with the exception of one note{{which|date=January 2015}}) of the [[pentatonic scale]],<ref name=hojo>{{cite journal |last =Howard |first =Joshua |authorlink = |title ="Music for a National Defense": Making Martial Music During the Anti-Japanese War |journal =Cross-currents |volume =13 |issue = |pages = |publisher = |location = |date =2014 |language = |url = https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-13/howard |jstor = |issn = |doi = |accessdate = |ref= none}} pp. 11-12</ref> however, create an effect of becoming "progressively more Chinese in character" over the course of the tune.<ref name=hohoho/> For reasons both musical and political, Nie came to be regarded as a model composer by Chinese musicians in the Maoist era.<ref name=chih2/> Howard Taubman, the ''New York Times'' music editor, initially panned the tune as telling us China's "fight is more momentous than her art" although, after US entrance into the war, he called its performance "delightful".<ref name=avant/> |

|||

b8. b16 g8. b16 \bar "|" d8. b16 a4 \bar "|" a2 \bar "|" e'4^> d4^> \bar "|" a4^> b4^> \bar "|" \break |

|||

d8^> b8^> r8 d8 \bar "|" b8 a16 b16 g4 \bar "|" b4 r4 \bar "|" d,8. e16 g8 g8 \bar "|" b8. b16 d8 d8 \bar "|" \break |

|||

a8 a16 a16 e4 \bar "|" a4. d,8 \bar "|" ^\< g4. g8 \bar "|" b4. b8 \! \bar "|" d2 \bar "|" \break |

|||

g,8. b16 d8 d8 \bar "|" e4 d4 \bar "|" b8. g16 \times 2/3 {d'8 d d} \bar "|" b8 r8 g8 r8 \bar "|" d4^> g4^> \bar "|" \break |

|||

b8. g16 \times 2/3 {d'8 d d} \bar "|" b8 r8 g8 r8 \bar "|" d4^> g4^> \bar "|" d4^> g4^> \bar "|" d4^> g4^> \bar "|" g4^> r4 \bar "|." |

|||

} |

|||

\addlyrics { |

|||

起 |

|||

来! 不 愿 做 奴 隶 的 人 们! 把 我 们 的 血 肉, |

|||

筑 成 我 们 新 的 长 城! 中 华 民 族 |

|||

到 了 最 危 险 的 时 候, 每 个 人 被 迫 着 发 出 |

|||

最 后 的 吼 声。 起 来! 起 来! 起 来! |

|||

我 们 万 众 一 心, 冒 着 敌 人 的 炮 火, 前 进! |

|||

冒 着 敌 人 的 炮 火, 前 进! 前 进! 前 进! 进! |

|||

} |

|||

</score> |

|||

A 1939 bilingual songbook which included the song called it "a good example of...copy[ing] the good points from Western music without impairing or losing [[Chinese music|our own national color]]".<ref name=chungking>{{cite book |last=Lee |first=Pao-chen |title=China's Patriots Sing |publisher=The China Information Publishing Co. |location=[[Chongqing|Chungking]] |year=1939}}</ref> Nie's piece is a [[March (music)|march]], a Western form, opening with a [[bugle call]] and a motif (with which it also closes) based on an ascending fourth interval from D to G inspired by [[The Internationale in Chinese|"The ''Internationale''"]].<ref name=hojo/> Its rhythmic patterns of triplets, accented downbeats, and syncopation and use (with the exception of one note, F{{music|#}} in the first verse) of the [[G major]] [[pentatonic scale]],<ref name=hojo>{{cite journal |last=Howard |first=Joshua |title="Music for a National Defense": Making Martial Music During the Anti-Japanese War |journal=Cross-Currents |volume=13 |date=2014 |url=https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-13/howard |ref=none |access-date=23 May 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181002215050/https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-13/howard |archive-date=2 October 2018 |url-status=live |pages=11–12}}</ref> however, create an effect of becoming "progressively more Chinese in character" over the course of the tune.<ref name=hohoho/> For reasons both musical and political, Nie came to be regarded as a model composer by Chinese musicians in the Maoist era.<ref name=chih2/> [[Howard Taubman]], the ''[[New York Times]]'' music editor, initially panned the tune as telling us China's "fight is more momentous than her art" although, after US entrance into the war, he called its performance "delightful".<ref name=avant/> |

|||

== Lyrics == |

|||

{| class="wikitable" cellpadding="6'' |

|||

==Lyrics== |

|||

|- |

|||

![[Simplified Chinese]] lyrics!![[Traditional Chinese]] lyrics!!Hanyu [[Pinyin]]!![[Jyutping]]!![[Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary|Hán-Việt]] lyrics!![[Xiao'erjing]]!![[Dungan language|Dunganese]] lyrics!![[English language|English]] lyrics!![[Portuguese language|Portuguese]] lyrics (official in [[Macau]]) |

|||

===Original version for Simplified Chinese, Traditional Chinese, and English === |

|||

|- |

|||

<div style="overflow-x:auto;"> |

|||

| |

|||

{| cellpadding="10" |

|||

<poem> |

|||

! [[Simplified Chinese]]<br>{{small|[[Pinyin]]}} |

|||

{{lang|zh|起来!不愿做奴隶的人们! |

|||

! [[Traditional Chinese]]<br>{{small|[[Bopomofo]]}} |

|||

把我们的血肉,筑成我们新的长城! |

|||

! [[English language|English]] lyrics |

|||

中华民族到了最危险的时候, |

|||

|- style="vertical-align:top; white-space:nowrap;" |

|||

每个人被迫着发出最后的吼声。 |

|||

|<poem lang="zh-hans" style="font-size:100%"> |

|||

起来!起来!起来! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|起来|Qǐlái!}}! {{ruby-zh-p|不愿|Búyuàn}}{{ruby-zh-p|做|zuò}}{{ruby-zh-p|奴隶|núlì}}{{ruby-zh-p|的|de}}{{ruby-zh-p|人们|rénmen!}}! |

|||

我们万众一心, |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|把|Bǎ}}{{ruby-zh-p|我们|wǒmen}}{{ruby-zh-p|的|de}}{{ruby-zh-p|血肉|xuèròu,}}, {{ruby-zh-p|筑成|zhùchéng}}{{ruby-zh-p|我们|wǒmen}}{{ruby-zh-p|新的|xīnde}}{{ruby-zh-p|长城|chángchéng!}}! |

|||

冒着敌人的炮火, |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|[[Zhonghua minzu|中华]]|[[Zhonghua minzu|Zhōnghuá]]}}{{ruby-zh-p|[[Zhonghua minzu|民族]]|[[Zhonghua minzu|Mínzú]]}}{{ruby-zh-p|到|dào}}{{ruby-zh-p|了|liao}}{{ruby-zh-p|最|zuì}}{{ruby-zh-p|危险的|wēixiǎnde}}{{ruby-zh-p|时候|shíhòu,}}, |

|||

前进! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|每个|Měige}}{{ruby-zh-p|人|rén}}{{ruby-zh-p|被迫着|bèipòzhe}}{{ruby-zh-p|发出|fāchū}}{{ruby-zh-p|最后的|zuìhòude}}{{ruby-zh-p|吼声|hǒushēng.}}。 |

|||

冒着敌人的炮火, |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|起来|Qǐlái!}}! {{ruby-zh-p|起来|Qǐlái!}}! {{ruby-zh-p|起来|Qǐlái!}}! |

|||

前进!前进!前进!进! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|我们|Wǒmen}}{{ruby-zh-p|万众一心|wànzhòngyīxīn,}}, |

|||

}}</poem> |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|冒着|Màozhe}}{{ruby-zh-p|敌人|dírén}}{{ruby-zh-p|的|de}}{{ruby-zh-p|炮火|pàohuǒ,}}, {{ruby-zh-p|前进|qiánjìn!}}! |

|||

| |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|冒着|Màozhe}}{{ruby-zh-p|敌人|dírén}}{{ruby-zh-p|的|de}}{{ruby-zh-p|炮火|pàohuǒ,}}, {{ruby-zh-p|前进|qiánjìn!}}! |

|||

<poem> |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|前进|Qiánjìn!}}! {{ruby-zh-p|前进|Qiánjìn!}}! {{ruby-zh-p|进|Jìn!}}!</poem> |

|||

{{lang|zh|起來!不願做奴隸的人們! |

|||

|<poem lang="zh-hant" style="font-size:100%"> |

|||

把我們的血肉,築成我們新的長城! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-b|起來|ㄑㄧˇ ㄌㄞˊ}}! {{ruby-zh-b|不願|ㄅㄨ' ㄩㄢ'}}{{ruby-zh-b|做|ㄗㄨㄛ'}}{{ruby-zh-b|奴隸|ㄋㄨ' ㄌㄧ'}}{{ruby-zh-b|的|˙ㄉㄜ}}{{ruby-zh-b|人們|ㄖㄣ' ˙ㄇㄣ}}! |

|||

中華民族到了最危險的時候, |

|||

{{ruby-zh-b|把|ㄅㄚˇ}}{{ruby-zh-b|我們|ㄨㄛˇ ˙ㄇㄣ}}{{ruby-zh-b|的|˙ㄉㄜ}}{{ruby-zh-b|血肉|ㄒㄩㄝ' ㄖㄡ'}}, {{ruby-zh-b|築成|ㄓㄨˋ ㄔㄥ'}}{{ruby-zh-b|我們|ㄨㄛˇ ˙ㄇㄣ}}{{ruby-zh-b|新的|ㄒㄧㄣ ˙ㄉㄜ}}{{ruby-zh-b|長城|ㄔㄤ' ㄔㄥ'}}! |

|||

每個人被迫著發出最後的吼聲。 |

|||

{{ruby-zh-b|[[Zhonghua minzu|中華]]|[[Zhonghua minzu|ㄓㄨㄥ ㄏㄨㄚ']]}}{{ruby-zh-b|[[Zhonghua minzu|民族]]|[[Zhonghua minzu|ㄇㄧㄣ' ㄗㄨ']]}}{{ruby-zh-b|到|ㄉㄠ'}}{{ruby-zh-b|了|ㄌㄧㄠˇ}}{{ruby-zh-b|最|ㄗㄨㄟ'}}{{ruby-zh-b|危險的|ㄨㄟ ㄒㄧㄢˇ ˙ㄉㄜ}}{{ruby-zh-b|時候|ㄕ' ㄏㄡˋ}}, |

|||

起來!起來!起來! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-b|每個|ㄇㄟˇ ˙ㄍㄜ}}{{ruby-zh-b|人|ㄖㄣ'}}{{ruby-zh-b|被迫著|ㄅㄟ' ㄆㄛ' ˙ㄓㄜ}}{{ruby-zh-b|發出|ㄈㄚ ㄔㄨ}}{{ruby-zh-b|最後的|ㄗㄨㄟ' ㄏㄡ' ˙ㄉㄜ}}{{ruby-zh-b|吼聲|ㄏㄡˇ ㄕㄥ}}。 |

|||

我們萬眾一心, |

|||

{{ruby-zh-b|起來|ㄑㄧˇ ㄌㄞˊ}}! {{ruby-zh-b|起來|ㄑㄧˇ ㄌㄞˊ}}! {{ruby-zh-b|起來|ㄑㄧˇ ㄌㄞˊ}}! |

|||

冒著敵人的砲火,前進! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-b|我們|ㄨㄛˇ ˙ㄇㄣ}}{{ruby-zh-b|萬眾一心|ㄨㄢ' ㄓㄨㄥ' ㄧˋ ㄒㄧㄣ}}, |

|||

冒著敵人的砲火,前進! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-b|冒著|ㄇㄠ' ˙ㄓㄜ}}{{ruby-zh-b|敵人|ㄉㄧ' ㄖㄣ'}}{{ruby-zh-b|的|˙ㄉㄜ}}{{ruby-zh-b|炮火|ㄆㄠ' ㄏㄨㄛˇ}}, {{ruby-zh-b|前進|ㄑㄧㄢ' ㄐㄧㄣ'}}! |

|||

前進!前進!進! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-b|冒著|ㄇㄠ' ˙ㄓㄜ}}{{ruby-zh-b|敵人|ㄉㄧ' ㄖㄣ'}}{{ruby-zh-b|的|˙ㄉㄜ}}{{ruby-zh-b|炮火|ㄆㄠ' ㄏㄨㄛˇ}}, {{ruby-zh-b|前進|ㄑㄧㄢ' ㄐㄧㄣ'}}! |

|||

}}</poem> |

|||

{{ruby-zh-b|前進|ㄑㄧㄢ' ㄐㄧㄣ'}}! {{ruby-zh-b|前進|ㄑㄧㄢ' ㄐㄧㄣ'}}! {{ruby-zh-b|進|ㄐㄧㄣ'}}!</poem> |

|||

| |

|||

|<poem lang="en" style="font-size:100%"> |

|||

<poem> |

|||

Arise! Those who refuse to be slaves! |

|||

Qǐlái! Búyuàn zuò núlì de rénmen! |

|||

With our flesh and blood, let us build our new Great Wall! |

|||

Bǎ wǒmen de xuèròu zhùchéng wǒmen xīnde chángchéng! |

|||

The [[Zhonghua minzu|Chinese nation]] face their greatest peril. |

|||

Zhōnghuá Mínzú dào le zùi wēixiǎnde shíhòu, |

|||

From each one the urgent call for action comes forth. |

|||

Měige rén bèipòzhe fāchū zùihòude hǒushēng. |

|||

Arise! Arise! Arise! |

|||

Qǐlái! Qǐlái! Qǐlái! |

|||

Us millions with but one heart, |

|||

Wǒmen wànzhòngyīxīn, |

|||

Braving the enemy's fire, march on! |

|||

Màozhe dírén de pàohuǒ, Qiánjìn! |

|||

Braving the enemy's fire, march on! |

|||

Màozhe dírén de pàohuǒ, Qiánjìn! |

|||

March on! March on, on! |

|||

Qiánjìn! Qiánjìn! Jìn! |

|||

</poem> |

</poem> |

||

|}</div> |

|||

| |

|||

<poem> |

|||

<div style="overflow-x:auto;"> |

|||

Heilai! Batjyun zou noudai di janmun! |

|||

{| cellpadding="10" |

|||

Baa ngomun di hyutjuk, zukcing ngomun san di coengseng! |

|||

! [[Help:IPA/Mandarin|IPA transcription]] |

|||

Zungfaa manzuk dou liu zeoi ngaihim di sihau. |

|||

! English translation in ''Songs of Fighting China''<ref>Lee, Pao-Ch'en. Songs of Fighting China [C]. New York: Chinese News Service, Printed in U. S. A. by Alliance-Pacific Press. Inc. 1943.</ref> |

|||

Mui go jan beibaak zoek faatceot zeoihau di haauseng. |

|||

|- style="vertical-align:top; white-space:nowrap;" |

|||

Heilai! Heilai! Heilai! |

|||

|<poem style="font-size:100%">{{IPA|wrap=none|[t͡ɕʰi²¹⁴ laɪ̯³⁵ pu⁵¹ ɥɛn⁵¹ t͡swɔ⁵¹ nu³⁵ li⁵¹ ti⁵¹ ʐən³⁵ mən³⁵] |

|||

Ngomun maanzung jatsam, |

|||

[pä²¹⁴ wɔ²¹⁴ mən³⁵ ti⁵¹ ɕɥɛ⁵¹ ʐoʊ̯⁵¹ ʈ͡ʂu⁵¹ ʈ͡ʂʰɤŋ³⁵ wɔ²¹⁴ mən³⁵ ɕin⁵⁵ ti⁵¹ ʈ͡ʂʰɑŋ³⁵ ʈ͡ʂʰɤŋ³⁵] |

|||

Makzoek dikjan di baaufo, cinzeon! |

|||

[ʈ͡ʂʊŋ⁵⁵ xwä³⁵ min³⁵ t͡su³⁵ tɑʊ̯⁵¹ ljɑʊ̯²¹⁴ t͡sweɪ̯⁵¹ weɪ̯⁵⁵ ɕjɛn²¹⁴ ti⁵¹ ʂʐ̩³⁵ xoʊ̯⁵¹] |

|||

Makzoek dikjan di baaufo, cinzeon! |

|||

[meɪ̯²¹⁴ kɤ⁵¹ ʐən³⁵ peɪ̯⁵¹ pʰwɔ⁵¹ ɖ͡ʐ̥ə fä⁵⁵ ʈ͡ʂʰu⁵⁵ t͡sweɪ̯⁵¹ xoʊ̯⁵¹ ti⁵¹ xoʊ̯²¹⁴ ʂɤŋ⁵⁵] |

|||

Cinzeon! Cinzeon! Zeon! |

|||

[t͡ɕʰi²¹⁴ laɪ̯³⁵ t͡ɕʰi²¹⁴ laɪ̯³⁵ t͡ɕʰi²¹⁴ laɪ̯³⁵] |

|||

</poem> |

|||

[wɔ²¹⁴ mən³⁵ wän⁵¹ ʈ͡ʂʊŋ⁵¹ i⁵⁵ ɕin⁵⁵] |

|||

| |

|||

[mɑʊ̯⁵¹ ɖ͡ʐ̥ə ti³⁵ ʐən³⁵ ti⁵¹ pʰɑʊ̯⁵¹ xwɔ²¹⁴ t͡ɕʰjɛn³⁵ t͡ɕin⁵¹] |

|||

<poem> |

|||

[mɑʊ̯⁵¹ ɖ͡ʐ̥ə ti³⁵ ʐən³⁵ ti⁵¹ pʰɑʊ̯⁵¹ xwɔ²¹⁴ t͡ɕʰjɛn³⁵ t͡ɕin⁵¹] |

|||

Khởi lai! Bất nguyện tố nô đãi đích nhân môn! |

|||

[t͡ɕʰjɛn³⁵ t͡ɕin⁵¹ t͡ɕʰjɛn³⁵ t͡ɕin⁵¹ t͡ɕin⁵¹] |

|||

Bả ngã môn đích huyết nhục, trúc thành ngã môn tân đích trường thành! |

|||

Trung hoa dân tộc đáo liễu tối nguy hiểm đích thời hậu, |

|||

Mỗi cá nhân bí bách khán phát xuất tối hậu đích hống thanh. |

|||

Khởi lai! Khởi lai! Khởi lai! |

|||

Ngã môn vạn chúng nhất tâm, |

|||

Mạo khán địch nhân đích pháo hỏa, tiền tiến! |

|||

Mạo khán địch nhân đích pháo hỏa, tiền tiến! |

|||

Tiền tiến! Tiền tiến! Tiến! |

|||

</poem> |

|||

| |

|||

<poem> |

|||

{{lang|ar|!ٿِلَىْ! بُيُوًا ظْ نُلِ دْ ژٍمٌ<br /> |

|||

!بَا وَعمٌ دْ سُؤژِوْ، جُچعْ وَعمٌ سٍ دْ چْاچعْ<br /> |

|||

.جوْخُوَ مٍظُ دَوْ لْ ظِوُ وِسِيًا دْ شِخِوْ<br /> |

|||

.مِؤقْ ژٍ بُوٍپْجْ فَاچُ ظِوُخِوْ دْ خِوْشٍْ<br /> |

|||

!ٿِلَىْ! ٿِلَىْ! ٿِلَىْ<br /> |

|||

،وَعمٌ وًاجوْ ءِسٍ<br /> |

|||

!مَوْجْ دِژٍ دْ پَوْخُوَع، ٿِيًادٍ<br /> |

|||

!مَوْجْ دِژٍ دْ پَوْخُوَع، ٿِيًادٍ<br /> |

|||

!ٿِيًادٍ! ٿِيًادٍ! دٍ |

|||

}}</poem> |

}}</poem> |

||

|<poem style="font-size:100%"> |

|||

| |

|||

Arise! ye who refuse to be bond slaves! |

|||

<poem> |

|||

With our very flesh and blood, Let us build our new Great Wall. |

|||

Чилэ! Бўйүан зуә нўлиди жынмын! |

|||

China's masses have met the day of danger, |

|||

Ба вәмынди щүэжу, җўчын вәмын щинди чончын! |

|||

Indignation fills the hearts of all our countrymen. |

|||

Җунхуа минзў долё зуэй выйщянди шыху. |

|||

Мыйгә жын быйпәҗә фачў зуэйхуди хушын. |

|||

Чилэ! Чилэ! Чилэ! |

|||

Вәмын ванҗун йищин, |

|||

Моҗә дыжынди похуә, Чянҗин! |

|||

Моҗә дыжынди похуә, Чянҗин! |

|||

Чянҗин! Чянҗин! Җин! |

|||

</poem> |

|||

| |

|||

<poem> |

|||

Arise, ye who refuse to be slaves! |

|||

With our flesh and blood, let us build a new Great Wall! |

|||

As China faces its greatest peril |

|||

From each one the urgent call to action comes forth. |

|||

Arise! Arise! Arise! |

Arise! Arise! Arise! |

||

Many hearts with one mind, |

|||

Brave the enemy's gunfire, March on! |

|||

Braving the enemies' fire! |

|||

March on! |

Brave the enemy's gunfire, March on! |

||

March on!, March on!, On! |

|||

Braving the enemies' fire! |

|||

March on! March on! March, march on! |

|||

</poem> |

</poem> |

||

|}</div> |

|||

| |

|||

<poem> |

|||

===1978–1982 version=== |

|||

De pé, vós que quereis ser livres! |

|||

{{Wikisource|zh:中华人民共和国第五届全国人民代表大会第一次会议关于中华人民共和国国歌的决定}} |

|||

Nossos corpos e sangue serão Nova Muralha! |

|||

{{Wikisource|en:March of the Volunteers}} |

|||

Um perigo fatal ameaça a China |

|||

A cada um compete o dever de lutar, |

|||

<div style="overflow-x:auto;"> |

|||

De pé! De pé! De pé! |

|||

{| cellpadding="10" |

|||

Todos em um coração |

|||

! [[Simplified Chinese]]<br>{{small|[[Pinyin]]}}!! [[Traditional Chinese]]<br>{{small|[[Bopomofo]]}}!![[English language|English]] lyrics |

|||

Contra o fogo inimigo! |

|||

|- style="vertical-align:top; white-space:nowrap;" |

|||

Marchai! |

|||

|<poem lang="zh-hans" style="font-size:100%"> |

|||

Contra o fogo inimigo! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|前进|Qiánjìn!}}! {{ruby-zh-p|各|Gè}}{{ruby-zh-p|民族|mínzú}}{{ruby-zh-p|英雄|yīngxióng}}{{ruby-zh-p|的|de}}{{ruby-zh-p|人民|rénmín!}}! |

|||

Marchai! Marchai! Marchai, já! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|伟大|Wěidà}}{{ruby-zh-p|的|de}}{{ruby-zh-p|共产党|gòngchǎndǎng,}},{{ruby-zh-p|领导|lǐngdǎo}}{{ruby-zh-p|我们|wǒmen}}{{ruby-zh-p|继续|jìxù}}{{ruby-zh-p|长征|chángzhēng!}}! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|万众一心|Wànzhòngyīxīn}}{{ruby-zh-p|奔|bēn}}{{ruby-zh-p|向|xiàng}}{{ruby-zh-p|共产主义|gòngchǎnzhǔyì}}{{ruby-zh-p|明天|míngtiān!}}! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|建设|Jiànshè}}{{ruby-zh-p|祖囯|zǔguó,}},{{ruby-zh-p|保卫|bǎowèi}}{{ruby-zh-p|祖囯|zǔguó,}},{{ruby-zh-p|英勇地|yīngyǒngde}}{{ruby-zh-p|斗争|dòuzhēng.}}。 |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|前进|Qiánjìn!}}!{{ruby-zh-p|前进|Qiánjìn!}}!{{ruby-zh-p|前进|Qiánjìn!}}! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|我们|Wǒmen}}{{ruby-zh-p|千秋万代|qiānqiūwàndài,}}, |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|高举|Gāojǔ}}{{ruby-zh-p|[[毛泽东]]|[[Máo Zédōng]]}}{{ruby-zh-p|旗帜|qízhì,}}, {{ruby-zh-p|前进|qiánjìn!}}! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|高举|Gāojǔ}}{{ruby-zh-p|毛泽东|Máo Zédōng}}{{ruby-zh-p|旗帜|qízhì,}}, {{ruby-zh-p|前进|qiánjìn!}}! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-p|前进|Qiánjìn!}}! {{ruby-zh-p|前进|Qiánjìn!}}! {{ruby-zh-p|进|Jìn!}}!</poem> |

|||

|<poem lang="zh-hant" style="font-size:100%"> |

|||

{{ruby-zh-b|前進|ㄑㄧㄢˊ ㄐㄧㄣˋ}},{{ruby-zh-b|各|ㄍㄜˋ}}{{ruby-zh-b|民族|ㄇㄧㄣˊ ㄗㄨˊ}}{{ruby-zh-b|英雄|ㄧㄥ ㄒㄩㄥˊ}}{{ruby-zh-b|的|ㄉㄧˊ }}{{ruby-zh-b|人民|ㄖㄣˊ ㄇㄧㄣˊ}}! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-b|偉大的|ㄨㄟˇ ㄉㄚˋ ㄉㄧˊ}}{{ruby-zh-b|共產黨|ㄍㄨㄥˋ ㄏㄢˇ ㄉㄤˇ}},{{ruby-zh-b|領導|ㄌㄧㄥˇ ㄉㄠˇ}}{{ruby-zh-b|我們|ㄨㄛˇ ㄇㄣˊ }}{{ruby-zh-b|繼續|ㄐㄧˋ ㄒㄩˋ}}{{ruby-zh-b|長征|ㄏㄤˊ ㄓㄥ}}! |

|||

{{ruby-zh-b|萬眾一心|ㄨㄢˋ ㄓㄨㄥˋ ㄧ ㄒㄧㄣ}}{{ruby-zh-b|奔|ㄅㄣ}}{{ruby-zh-b|向|ㄒㄧㄤˋ}}{{ruby-zh-b|共產主義|ㄍㄨㄥˋ ㄏㄢˇ ㄓㄨˇ ㄧˋ}}{{ruby-zh-b|明天|ㄇㄧㄥˊ ㄊㄧㄢ}}! |

|||