Sea urchin: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

m rv sock |

||

| (709 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Class of marine invertebrates}} |

|||

{{other uses}} |

|||

{{Other uses|Sea Urchin (disambiguation)}} |

|||

{{Taxobox |

|||

{{Good article}} |

|||

{{Automatic taxobox |

|||

| name = Sea urchin |

| name = Sea urchin |

||

| fossil_range = {{Fossil range|Ordovician| |

| fossil_range = {{Fossil range|Ordovician|Present}} |

||

| image = Tripneustes ventricosus (West Indian Sea Egg-top) and Echinometra viridis (Reef Urchin - bottom).jpg |

| image = Tripneustes ventricosus (West Indian Sea Egg-top) and Echinometra viridis (Reef Urchin - bottom).jpg |

||

| |

| image_upright = 1.15 |

||

| image_caption |

| image_caption = ''[[Tripneustes ventricosus]]'' and ''[[Echinometra viridis]]'' |

||

| |

| taxon = Echinoidea |

||

| authority = [[Nathaniel Gottfried Leske|Leske]], 1778 |

|||

| phylum = [[Echinodermata]] |

|||

| subphylum = [[Echinozoa]] |

|||

| classis = '''Echinoidea''' |

|||

| classis_authority=[[Nathaniel Gottfried Leske|Leske]], 1778 |

|||

| subdivision_ranks = Subclasses |

| subdivision_ranks = Subclasses |

||

| subdivision = |

| subdivision = |

||

* |

*Subclass [[Perischoechinoidea]] |

||

**Order [[Cidaroida]] (pencil urchins) |

|||

** Superorder [[Diadematacea]] |

|||

* |

*Subclass [[Euechinoidea]] |

||

** |

**Superorder [[Atelostomata]] |

||

*** |

***Order [[Cassiduloida]] |

||

***Order [[Spatangoida]] (heart urchins) |

|||

** Superorder [[Echinacea (animal)|Echinacea]] |

|||

** |

**Superorder [[Diadematacea]] |

||

*** |

***Order [[Diadematoida]] |

||

*** |

***Order [[Echinothurioida]] |

||

*** |

***Order [[Pedinoida]] |

||

**Superorder [[Echinacea (animal)|Echinacea]] |

|||

*** Order [[Temnopleuroida]] |

|||

***Order [[Arbacioida]] |

|||

** Superorder [[Gnathostomata (echinoid)|Gnathostomata]] |

|||

*** |

***Order [[Echinoida]] |

||

*** |

***Order [[Phymosomatoida]] |

||

***Order [[Salenioida]] |

|||

***Order [[Temnopleuroida]] |

|||

**Superorder [[Gnathostomata (echinoid)|Gnathostomata]] |

|||

***Order [[Clypeasteroida]] (sand dollars) |

|||

***Order [[Holectypoida]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

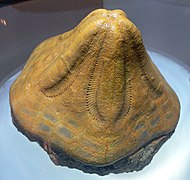

'''Sea urchins''' or '''urchins''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|ɜr|tʃ|ɪ|n|z}}), archaically called '''sea hedgehogs''',<ref>Wright, Anne. 1851. ''The Observing Eye, Or, Letters to Children on the Three Lowest Divisions of Animal Life.'' London: Jarrold and Sons, p. 107.</ref><ref>Soyer, Alexis. 1853. ''The Pantropheon Or History Of Food, And Its Preparation: From The Earliest Ages Of The World.'' Boston: Ticknor, Reed, and Fields,, p. 245.</ref> are small, [[spine (zoology)|spiny]], globular animals that, with their close kin, such as [[sand dollar]]s, constitute the class '''Echinoidea''' of the [[echinoderm]] phylum. About 950 species of echinoids inhabit all oceans from the intertidal to {{convert|5000|m|ft fathom}} deep.<ref name=adw>{{cite web|url=http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Echinoidea.html|title=Animal Diversity Web – Echinoidea|publisher=University of Michigan Museum of Zoology|accessdate=2012-08-26}}</ref> The shell, or "test", of sea urchins is round and spiny, typically from {{convert|3|to|10|cm|abbr=on}} across. Common colors include black and dull shades of green, olive, brown, purple, blue, and red. Sea urchins move slowly, feeding primarily on [[algae]]. [[Sea otter]]s, [[starfish]], [[wolf eel]]s, [[triggerfish]], and other [[predation|predators]] hunt and feed on sea urchins. Their [[roe]] is a delicacy in many cuisines. The name "urchin" is an old word for [[hedgehog]], which sea urchins resemble. |

|||

'''Sea urchins''' or '''urchins''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|ɜr|tʃ|ɪ|n|z}}) are typically [[spine (zoology)|spiny]], globular [[Animalia|animals]], [[echinoderm]]s in the class Echinoidea. About 950 species live on the seabed, inhabiting all oceans and depth zones from the intertidal to {{convert|5000|m|ft fathom}}.<ref name=adw>{{cite web|url=http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Echinoidea.html|title=Animal Diversity Web – Echinoidea|publisher=University of Michigan Museum of Zoology|accessdate=26 August 2012|archive-date=16 May 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110516154925/http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Echinoidea.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Their [[Test (biology)|tests]] (hard shells) are round and spiny, typically from {{convert|3|to|10|cm|0|abbr=on}} across. Sea urchins move slowly, crawling with their [[tube feet]], and sometimes pushing themselves with their spines. They feed primarily on [[algae]] but also eat slow-moving or [[Sessility (motility)|sessile]] animals. Their [[predation|predators]] include [[shark]]s, [[sea otter]]s, [[starfish]], [[wolf eel]]s, and [[triggerfish]]. |

|||

== Taxonomy == |

|||

Like all echinoderms, adult sea urchins have fivefold symmetry with their [[Echinoderm#Larval development|pluteus larvae]] featuring [[Bilateral symmetry|bilateral (mirror) symmetry]]; The latter indicates that they belong to the [[Bilateria]], along with [[chordate]]s, [[arthropod]]s, [[annelid]]s and [[mollusc]]s. Sea urchins are found in every ocean and in every climate, from the [[tropics]] to the [[polar regions]], and inhabit marine benthic (sea bed) habitats, from rocky shores to [[hadal zone]] depths. The fossil record of the ''Echinoids'' dates from the [[Ordovician]] period, some 450 million years ago. The closest echinoderm relatives of the sea urchin are the [[sea cucumber]]s (Holothuroidea), which like them are [[deuterostome]]s, a clade that includes the [[chordate]]s. ([[Sand dollar]]s are a separate order in the sea urchin class Echinoidea.) |

|||

The animals have been studied since the 19th century as [[model organism]]s in [[developmental biology]], as their embryos were easy to observe. That has continued with studies of their [[genome]]s because of their unusual fivefold symmetry and relationship to chordates. Species such as the [[Eucidaris tribuloides|slate pencil urchin]] are popular in aquaria, where they are useful for controlling algae. Fossil urchins have been used as protective [[amulet]]s. |

|||

== Diversity == |

|||

{{See also|List of echinodermata orders}} |

{{See also|List of echinodermata orders}} |

||

[[File:Heterocentrotus mammilitatus.jpg|thumb|There is a wide diversity of shapes in sea urchins. This "slate-pencil sea urchin" (''[[Heterocentrotus mamillatus]]''), despite its big, wide spines, is a regular sea urchin and not a cidaroid: its spines are not covered with algae. ]] |

|||

Sea urchins are members of the [[phylum]] [[Echinoderm]]ata, which also includes sea stars, [[Holothuroidea|sea cucumbers]], [[brittle star]]s, and [[crinoid]]s. Like other echinoderms, they have five-fold symmetry (called [[symmetry (biology)#Pentamerism|pentamerism]]) and move by means of hundreds of tiny, transparent, adhesive "[[tube feet]]". The symmetry is not obvious in the living animal, but is easily visible in the dried [[test (biology)|test]]. |

|||

Sea urchins are members of the [[phylum]] [[Echinoderm]]ata, which also includes [[starfish]], [[sea cucumbers]], [[sand dollar]]s, [[brittle star]]s, and [[crinoid]]s. Like other echinoderms, they have five-fold symmetry (called [[symmetry (biology)#Pentamerism|pentamerism]]) and move by means of hundreds of tiny, transparent, adhesive "[[tube feet]]". The symmetry is not obvious in the living animal, but is easily visible in the dried [[test (biology)|test]].<ref name=Ruppert/> |

|||

Specifically, the term "sea urchin" refers to the "regular echinoids", which are symmetrical and globular, and includes several different taxonomic groups, including two subclasses : [[Euechinoidea]] ("modern" sea urchins, including irregular ones) and [[Cidaroidea]] or "slate-pencil urchins", which have very thick, blunt spines, with algae and sponges growing on it. The irregular sea urchins are an infra-class inside the Euechinoidea, called [[Irregularia]], and include [[Atelostomata]] and [[Neognathostomata]]. "Irregular" echinoids include: flattened [[sand dollar]]s, [[Clypeasteroida|sea biscuits]], and [[Echinocardium|heart urchins]]. |

|||

Specifically, the term "sea urchin" refers to the "regular echinoids", which are symmetrical and globular, and includes several different taxonomic groups, with two subclasses: [[Euechinoidea]] ("modern" sea urchins, including irregular ones) and [[Cidaroidea]], or "slate-pencil urchins", which have very thick, blunt spines, with algae and sponges growing on them. The "irregular" sea urchins are an infra-class inside the Euechinoidea, called [[Irregularia]], and include [[Atelostomata]] and [[Neognathostomata]]. Irregular echinoids include flattened [[sand dollar]]s, [[Clypeasteroida|sea biscuits]], and [[Echinocardium|heart urchins]].<ref name=WoRMS>{{cite WoRMS |author=Kroh, A. |author2=Hansson, H. |year=2013 |title=''Echinoidea'' (Leske, 1778) |id=123082 |access-date=2014-01-04}}</ref> |

|||

Together with sea cucumbers ([[Holothuroidea]]), they make up the subphylum [[Echinozoa]], which is characterized by a globoid shape without arms or projecting rays. Sea cucumbers and the irregular echinoids have secondarily evolved diverse shapes. Although many sea cucumbers have branched [[tentacle]]s surrounding their oral openings, these have originated from modified tube feet and are not homologous to the arms of the crinoids, sea stars, and brittle stars. |

Together with sea cucumbers ([[Holothuroidea]]), they make up the subphylum [[Echinozoa]], which is characterized by a globoid shape without arms or projecting rays. Sea cucumbers and the irregular echinoids have secondarily evolved diverse shapes. Although many sea cucumbers have branched [[tentacle]]s surrounding their oral openings, these have originated from modified tube feet and are not homologous to the arms of the crinoids, sea stars, and brittle stars.<ref name=Ruppert/> |

||

<gallery style="text-align:center;" mode="packed"> |

<gallery style="text-align:center;" mode="packed"> |

||

File:Paracentrotus lividus profil.JPG|''[[Paracentrotus lividus]]'', a regular sea urchin ([[Euechinoidea]], infraclass [[Carinacea]]) |

File:Paracentrotus lividus profil.JPG|''[[Paracentrotus lividus]]'', a regular sea urchin ([[Euechinoidea]], infraclass [[Carinacea]]) |

||

File:Live Sand Dollar trying to bury itself in beach sand.jpg|A [[sand dollar]], an irregular sea urchin ([[Irregularia]]) |

File:Live Sand Dollar trying to bury itself in beach sand.jpg|A [[sand dollar]], an irregular sea urchin ([[Irregularia]]) |

||

File:Phyllacanthus.jpg|''[[Phyllacanthus imperialis]]'', a cidaroid sea urchin ([[Cidaroidea]]) |

File:Phyllacanthus.jpg|''[[Phyllacanthus imperialis]]'', a cidaroid sea urchin ([[Cidaroidea]]) |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

== |

== Description == |

||

[[File:Urchin9b.jpg|thumb|Sea urchin anatomy based on ''[[Arbacia]]'' sp.]] |

[[File:Urchin9b.jpg|thumb|upright=1.5|Sea urchin anatomy based on ''[[Arbacia]]'' sp.]] |

||

Urchins typically range in size from {{convert|3|to|10|cm|in|0|abbr=on}}, but the largest species can reach up to {{convert|36|cm|in|abbr=on}}.<ref name=IZ>{{cite book |last=Barnes |first=Robert D. |year=1982 |title= Invertebrate Zoology |publisher=Holt-Saunders International |location= Philadelphia, PA|pages= 961–981|isbn= 0-03-056747-5}}</ref> They have a rigid, usually spherical body bearing moveable spines, which give the [[Class (biology)|class]] the name ''Echinoidea'' (from the Greek {{wikt-lang|grc|ἐχῖνος}} {{lang|grc-la|ekhinos}} 'spine').<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.tulane.edu/~bwee/eeb111/GreekLatin%20Roots.html |title=Taxonomic Etymologies EEOB 111 |author=Guill, Michael |access-date=13 March 2018 |archive-date=17 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240517161239/https://www2.tulane.edu/~bwee/eeb111/GreekLatin%20Roots.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The name ''urchin'' is an old word for [[hedgehog]], which sea urchins resemble; they have archaically been called '''sea hedgehogs'''.<ref>Wright, Anne. 1851. ''The Observing Eye, Or, Letters to Children on the Three Lowest Divisions of Animal Life.'' London: Jarrold and Sons, p. 107.</ref><ref>[[Alexis Soyer|Soyer, Alexis]]. 1853. ''The Pantropheon Or History of Food, And Its Preparation: From The Earliest Ages Of The World.'' Boston: Ticknor, Reed, and Fields, p. 245.</ref> The name is derived from the Old French {{wikt-lang|fro|herichun}}, from Latin {{wikt-lang|la|ericius}} ('hedgehog').<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=urchin (n.) |url=https://www.etymonline.com/word/urchin |dictionary=Online Etymology Dictionary |access-date=13 March 2018 |archive-date=15 March 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180315070539/https://www.etymonline.com/word/urchin |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

Urchins typically range in size from {{convert|6|to|12|cm|in|abbr=on}}, although the largest species can reach up to {{convert|36|cm|in|abbr=on}}.<ref name=IZ>{{cite book |last=Barnes |first=Robert D. |year=1982 |title= Invertebrate Zoology |publisher= Holt-Saunders International |location= Philadelphia, PA|pages= 961–981|isbn= 0-03-056747-5}}</ref> |

|||

Like other echinoderms, sea urchin early larvae have bilateral symmetry,<ref>Stachan and Read, ''Human Molecular Genetics'', [https://books.google.com/books?id=8U0VAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA381 "What Makes Us Human", p. 381].</ref> but they develop five-fold symmetry as they mature. This is most apparent in the "regular" sea urchins, which have roughly spherical bodies with five equally sized parts radiating out from their central axes. The mouth is at the base of the animal and the anus at the top; the lower surface is described as "oral" and the upper surface as "aboral".{{efn|The tube feet are present in all parts of the animal except around the anus, so technically, the whole surface of the body should be considered to be the oral surface, with the aboral (non-mouth) surface limited to the immediate vicinity of the anus.<ref name=Ruppert/>}}<ref name=Ruppert>{{Cite book |last1=Ruppert |first1=Edward E. |last2=Fox |first2=Richard S. |last3=Barnes |first3=Robert D. |year=2004 |title=Invertebrate Zoology: A Functional Evolutionary Approach |url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780030259821 |url-access=registration |edition=7th |location=Belmont, CA |publisher=Thomson-Brooks/Cole |pages=[https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780030259821/page/896/mode/2up 896–906] |isbn=0030259827 |oclc=53021401}}</ref> |

|||

=== Fivefold symmetry === |

|||

Like other echinoderms, sea urchin early larvae have bilateral symmetry,<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=8U0VAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA381 Stachan and Read, ''Human Molecular Genetics,'' p. 381]: "What Makes Us Human"</ref> but they develop five-fold symmetry as they mature. This is most apparent in the "regular" sea urchins, which have roughly spherical bodies with five equally sized parts radiating out from their central axes. Several sea urchins, however, including the sand dollars, are oval in shape, with distinct front and rear ends, giving them a degree of bilateral symmetry. In these urchins, the upper surface of the body is slightly domed, but the underside is flat, while the sides are devoid of tube feet. This "irregular" body form has evolved to allow the animals to burrow through sand or other soft materials.<ref name=IZ /> |

|||

Several sea urchins, however, including the sand dollars, are oval in shape, with distinct front and rear ends, giving them a degree of bilateral symmetry. In these urchins, the upper surface of the body is slightly domed, but the underside is flat, while the sides are devoid of tube feet. This "irregular" body form has evolved to allow the animals to burrow through sand or other soft materials.<ref name=IZ /> |

|||

=== Organs and test === |

|||

The lower half of a sea urchin's body is referred to as the oral surface, because it contains the mouth, while the upper half is the aboral surface. The internal organs are enclosed in a hard shell or "[[Test (biology)|test]]" composed of fused plates of [[calcium carbonate]] covered by a thin [[dermis]] and [[Epidermis (skin)|epidermis]]. The test is rigid, and divides into five ambulacral grooves separated by five interambulacral areas. Each of these areas consists of two rows of plates, so the sea urchin test includes 20 rows of plates in total. The plates are covered in rounded tubercles, to which the spines are attached. The inner surface of the test is lined by [[peritoneum]].<ref name=IZ /> Sea urchins convert aqueous [[carbon dioxide]] using a [[catalyst|catalytic]] process involving [[nickel]] into the calcium carbonate portion of the test.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gizmag.com/carbon-capture-calcium-carbonate/26101/|title=Sea urchins reveal promising carbon capture alternative|publisher=Gizmag|date=4 February 2013|accessdate=2013-02-05}}</ref> |

|||

== Systems == |

|||

=== Musculoskeletal === |

|||

Sea urchins' [[tube feet]] arise from the five ambulacral grooves. Tube feet are moved by a [[water vascular system]], which works through hydraulic pressure, allowing the sea urchin to pump water into and out of the tube feet, enabling it to move. |

|||

{{Further|Test (biology)|Tube feet}} |

|||

[[File:Seeigel-Saugfuesse(Galicien2005).jpg|thumb|upright=0.7|[[Tube feet]] of a [[strongylocentrotus purpuratus|purple sea urchin]]]] |

|||

The internal organs are enclosed in a hard shell or test composed of fused plates of [[calcium carbonate]] covered by a thin [[dermis]] and [[epidermis]]. The test is referred to as an [[endoskeleton]] rather than exoskeleton even though it encloses almost all of the urchin. This is because it is covered with a thin layer of muscle and skin; sea urchins also do not need to molt the way invertebrates with true exoskeletons do, instead the plates forming the test grow as the animal does. |

|||

[[File:Seeigel-Saugfuesse(Galicien2005).jpg|thumb|center|upright=0.7|[[Podia]] of a [[strongylocentrotus purpuratus|purple sea urchin]].]] |

|||

The test is rigid, and divides into five ambulacral grooves separated by five wider interambulacral areas. Each of these ten longitudinal columns consists of two sets of plates (thus comprising 20 columns in total). The ambulacral plates have pairs of tiny holes through which the tube feet extend.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Echinoid Directory - Natural History Museum |url=https://www.nhm.ac.uk/our-science/data/echinoid-directory/morphology/regulars/intro.html |website=www.nhm.ac.uk |publisher=Natural History Museum, UK |access-date=28 December 2022 |archive-date=8 December 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231208134929/https://www.nhm.ac.uk/our-science/data/echinoid-directory/morphology/regulars/intro.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

=== Mouth/anus === |

|||

[[File:Strongylocentrotus purpuratus 020313.JPG|thumb|Oral surface of ''[[Strongylocentrotus purpuratus]]'' showing teeth of Aristotle's lantern, spines and tube feet]] |

|||

The mouth lies in the centre of the oral surface in regular urchins, or towards one end in irregular urchins. It is surrounded by lips of softer tissue, with numerous small, bony pieces embedded in it. This area, called the peristome, also includes five pairs of modified tube feet and, in many species, five pairs of gills. On the upper surface, opposite the mouth, is the [[periproct]], which surrounds the [[anus]]. The periproct contains a variable number of hard plates, depending on species, one of which contains the [[madreporite]].<ref name=IZ /> The structure of the mouth and teeth have been found to be so efficient at grasping and grinding that their structure has been tested for use in real-world applications.<ref>[http://www.engadget.com/2016/05/04/sea-urchin-inspired-rover-claw/ Claw inspired by sea urchins' mouth can scoop up Martian soil<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

All of the plates are covered in rounded tubercles to which the spines are attached. The spines are used for defence and for locomotion and come in a variety of forms.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Echinoid Directory - Natural History Museum |url=https://www.nhm.ac.uk/our-science/data/echinoid-directory/morphology/regulars/intro.html |website=www.nhm.ac.uk |publisher=Natural History Museum, UK. |access-date=28 December 2022 |archive-date=8 December 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231208134929/https://www.nhm.ac.uk/our-science/data/echinoid-directory/morphology/regulars/intro.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The inner surface of the test is lined by [[peritoneum]].<ref name=IZ /> Sea urchins convert aqueous [[carbon dioxide]] using a [[Catalysis|catalytic]] process involving [[nickel]] into the calcium carbonate portion of the test.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gizmag.com/carbon-capture-calcium-carbonate/26101/|title=Sea urchins reveal promising carbon capture alternative|publisher=Gizmag|date=4 February 2013|access-date=2013-02-05|archive-date=2016-07-14|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160714210351/http://www.gizmag.com/carbon-capture-calcium-carbonate/26101/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

=== Endoskeleton === |

|||

The sea urchin builds its [[wikt:spicule|spicules]], the sharp, crystalline "bones" that constitute the animal’s [[endoskeleton]], in the [[larvae|larval]] stage. The fully formed spicule is composed of a single crystal with an unusual morphology. It has no facets, and within 48 hours of fertilization, assumes a shape that looks much like the [[Mercedes-Benz]] logo.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Balakirev |first1=E. S. |last2=Pavlyuchkov |first2=V. A. |last3=Ayala |first3=F. J. |title=DNA variation and symbiotic associations in phenotypically diverse sea urchin Strongylocentrotus intermedius |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |volume=105 |pages=16218–16223 |year=2008 |doi=10.1073/pnas.0807860105 |laysummary=http://newswise.com/articles/view/545739/ |laysource=[[University of Wisconsin-Madison]] |laydate=October 27, 2008 |issue=42|bibcode = 2008PNAS..10516218B }}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Ricci di mare luminosi.jpg|thumb|Mediterranean sea urchins illuminated to reveal the mesodermal calcite structure.]] |

|||

In other echinoderms, the endoskeleton is associated with a layer of muscle that allows the animal to move its arms or other body parts. This is entirely absent in sea urchins, which are unable to move in this way. |

|||

Most species have two series of spines, primary (long) and secondary (short), distributed over the surface of the body, with the shortest at the poles and the longest at the equator. The spines are usually hollow and cylindrical. Contraction of the muscular sheath that covers the test causes the spines to lean in one direction or another, while an inner sheath of collagen fibres can reversibly change from soft to rigid which can lock the spine in one position. Located among the spines are several types of [[pedicellaria]], moveable stalked structures with jaws.<ref name=Ruppert/> |

|||

Sea urchins move by walking, using their many flexible tube feet in a way similar to that of starfish; regular sea urchins do not have any favourite walking direction.<ref>Kazuya Yoshimura, Tomoaki Iketani et Tatsuo Motokawa, "Do regular sea urchins show preference in which part of the body they orient forward in their walk ?", ''Marine Biology'', vol. 159, no 5, 2012, p. 959–965.</ref> The tube feet protrude through pairs of pores in the test, and are operated by a [[water vascular system]]; this works through [[hydraulic pressure]], allowing the sea urchin to pump water into and out of the tube feet. During locomotion, the tube feet are assisted by the spines which can be used for pushing the body along or to lift the test off the substrate. Movement is generally related to feeding, with the [[red sea urchin]] (''Mesocentrotus franciscanus'') managing about {{convert|7.5|cm|in|0|abbr=on}} a day when there is ample food, and up to {{convert|50|cm|in|0|abbr=on}} a day where there is not. An inverted sea urchin can right itself by progressively attaching and detaching its tube feet and manipulating its spines to roll its body upright.<ref name=Ruppert/> Some species bury themselves in soft sediment using their spines, and ''[[Paracentrotus lividus]]'' uses its jaws to burrow into soft rocks.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Boudouresque |first1=Charles F. |last2=Verlaque |first2=Marc |editor-last=Lawrence |editor-first=John M. |title=Edible Sea Urchins: Biology and Ecology |publisher=Elsevier |year=2006 |page=243 |chapter=13: Ecology of ''Paracentrotus lividus'' |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6T2JomruARoC&pg=PA243 |isbn=978-0-08-046558-6 }}</ref> |

|||

<gallery style="text-align:center;" mode="packed"> |

<gallery style="text-align:center;" mode="packed"> |

||

File:Sea Urchin test 5629 03 22.jpg|Test of an ''[[Echinus esculentus]]'', a regular sea urchin |

File:Sea Urchin test 5629 03 22.jpg|Test of an ''[[Echinus esculentus]]'', a regular sea urchin |

||

File:BlackSeaUrchinTest.jpg|Test of black sea urchin, showing tubercles and ambulacral plates (on right) |

|||

File:Echinodiscus2.jpg|Test of an ''[[Echinodiscus tenuissimus]]'', an [[Irregularia|irregular sea urchin]] ("[[Clypeasteroida|sand dollar]]"). |

|||

File:Inner surface of black sea urchin test.jpg|Inner surface of test, showing pentagonal interambulacral plates on right, and holes for tube feet on left. |

|||

File:Phyllacanthus imperialis test.JPG|Test of a ''[[Phyllacanthus imperialis]]'', a [[Cidaroida|cidaroid]] sea urchin. These are characterised by their big tubercles, bearing large radiola. |

|||

File:Echinodiscus2.jpg|Test of an ''[[Echinodiscus tenuissimus]]'', an [[Irregularia|irregular sea urchin]] ("[[Clypeasteroida|sand dollar]]") |

|||

File:Sea urchin shell - pattern (6658690371).jpg|Close-up on the test of a regular sea urchin. One can see an ambulacrum (yellow) with its two rows of pore-pairs, between two interambulacra (green). The tubercles are non perforated. |

|||

File:Phyllacanthus imperialis test.JPG|Test of a ''[[Phyllacanthus imperialis]]'', a [[Cidaroida|cidaroid]] sea urchin. These are characterised by their big tubercles, bearing large radiola. |

|||

File:Sea Urchin Shell detail.jpg|Close-up on a cidaroid sea urchin apical disc : the 5 holes are the gonopores, and the central one is the anus ("periproct"). The biggest genital plate is the [[madreporite]]. |

|||

File:Sea urchin shell - pattern (6658690371).jpg|Close-up of the test showing an ambulacral groove with its two rows of pore-pairs, between two interambulacra areas (green). The tubercles are non-perforated. |

|||

File:Sea Urchin Shell detail.jpg|Close-up of a cidaroid sea urchin apical disc: the 5 holes are the gonopores, and the central one is the anus ("periproct"). The biggest genital plate is the [[madreporite]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Apical disc and periproct |url=https://www.nhm.ac.uk/our-science/data/echinoid-directory/morphology/regulars/discmorph.html |publisher=[[Natural History Museum, London]] |access-date=2 November 2019 |archive-date=2 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240302122236/https://www.nhm.ac.uk/our-science/data/echinoid-directory/morphology/regulars/discmorph.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

=== |

=== Feeding and digestion === |

||

[[File:Seeigel Gebiss.jpg|thumb|Dentition of a sea urchin]] |

|||

[[File:Flower urchin by Vincent C Chen.jpg|thumb|The [[flower urchin]] is a dangerous, potentially lethally venomous species.]] |

|||

Typical sea urchins have spines about {{convert|1|to|3|cm|abbr=on}} in length, {{convert|1|to|2|mm|abbr=on}} thick, and more or less sharp. The genus ''[[Diadema (genus)|Diadema]]'', familiar in the tropics, has the longest spines; they are thin and can reach {{convert|10|to|30|cm|abbr=on}} long. |

|||

The [[spine (zoology)|spines]], long and sharp in some species, protect the urchin from [[predator]]s. They inflict a painful wound when they penetrate human skin, but are not themselves dangerous if fully removed promptly; if left in the skin, further problems may occur.<ref>{{cite journal|author1=Matthew D. Gargus |author2=David K. Morohashi |title=A sea-urchin spine chilling remedy|format=letter to the Editor|journal=[[New England Journal of Medicine]]|year=2012|volume=30|issue=19|pages=1867–1868|doi=10.1056/NEJMc1209382|url=http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc1209382}}</ref> |

|||

The mouth lies in the centre of the oral surface in regular urchins, or towards one end in irregular urchins. It is surrounded by lips of softer tissue, with numerous small, embedded bony pieces. This area, called the peristome, also includes five pairs of modified tube feet and, in many species, five pairs of gills.<ref name=IZ /> The jaw apparatus consists of five strong arrow-shaped plates known as pyramids, the ventral surface of each of which has a toothband with a hard tooth pointing towards the centre of the mouth. Specialised muscles control the protrusion of the apparatus and the action of the teeth, and the animal can grasp, scrape, pull and tear.<ref name=Ruppert/> The structure of the mouth and teeth have been found to be so efficient at grasping and grinding that similar structures have been tested for use in real-world applications.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.engadget.com/2016/05/04/sea-urchin-inspired-rover-claw/ |title=Claw inspired by sea urchins' mouth can scoop up Martian soil |access-date=2017-09-11 |archive-date=2019-10-12 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191012025318/https://www.engadget.com/2016/05/04/sea-urchin-inspired-rover-claw/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

Some families of tropical sea urchins are known to have venomous spines, like [[Diadematidae]] and [[Echinothuriidae]]. The first family contains the "[[Diadema (genus)|Diadem]]" sea urchins, and the latter the "[[Asthenosoma|fire urchins]]". |

|||

On the upper surface of the test at the aboral pole is a membrane, the [[periproct]], which surrounds the [[anus]]. The periproct contains a variable number of hard plates, five of which, the genital plates, contain the gonopores, and one is modified to contain the [[madreporite]], which is used to balance the water vascular system.<ref name=Ruppert/> |

|||

Many urchins in the [[Toxopneustidae]] are venomous as well, but the danger does not come from their spines (short and blunt) but from their [[pedicellaria]]e, like the [[Tripneustes gratilla|collector urchin]] and especially the [[Toxopneustes pileolus|flower urchin]], the only potentially lethal echinoderm known to date.<ref name="Mah Toxopneustes">{{cite web |url=http://www.echinoblog.blogspot.fr/2014/02/what-we-know-about-worlds-most-venomous.html |title=What we know about the world's most venomous sea urchin Toxopneustes fits in this blog post! |last1=Mah |first1=Christopher |last2= |first2= |date=February 5, 2014 |website=The Echinoblog |publisher= |accessdate=}}.</ref>{{sps|date=July 2016}} |

|||

[[File:Lanterne d'Aristote.jpg|thumb|Aristotle's lantern in a sea urchin, viewed in lateral section]] |

|||

=== Reproductive organs === |

|||

[[File:Male Flower Sea Urchin (toxopneustes roseus).theora.ogv|thumb|Male flower sea urchin (''Toxopneustes roseus'') releasing milt, November 1, 2011, Lalo Cove, Sea of Cortez]] |

|||

Sea urchins are [[Dioecy|dioecious]], having separate male and female sexes, although distinguishing the two is not easy, except for their locations on the sea bottom. Males generally choose elevated and exposed locations, so their [[milt]] can be broadcast by sea currents. Females generally choose low-lying locations in sea bottom crevices, presumably so the tiny larvae can have better protection from predators. Indeed, very small sea urchins are found hiding beneath rocks. Regular sea urchins have five [[gonad]]s, lying underneath the interambulacral regions of the test, while the irregular forms have only four, with the hindmost gonad being absent. Each gonad has a single duct rising from the upper pole to open at a [[gonopore]] lying in one of the genital plates surrounding the anus. The gonads are lined with muscles underneath the peritoneum, and these allow the animal to squeeze its [[gamete]]s through the duct and into the surrounding sea water where fertilization takes place.<ref name=IZ /> |

|||

The mouth of most sea urchins is made up of five calcium carbonate teeth or plates, with a fleshy, tongue-like structure within. The entire chewing organ is known as Aristotle's lantern from [[Aristotle]]'s description in his ''[[History of Animals]]'' (translated by [[D'Arcy Thompson]]): |

|||

== Physiology == |

|||

{{Blockquote|... the urchin has what we mainly call its head and mouth down below, and a place for the issue of the residuum up above. The urchin has, also, five hollow teeth inside, and in the middle of these teeth a fleshy substance serving the office of a [[tongue]]. Next to this comes the [[esophagus]], and then the [[stomach]], divided into five parts, and filled with excretion, all the five parts uniting at the [[anus|anal]] vent, where the shell is perforated for an outlet ... In reality the mouth-apparatus of the urchin is continuous from one end to the other, but to outward appearance it is not so, but looks like a horn [[lantern]] with the panes of horn left out.}} |

|||

=== Digestion === |

|||

The mouth of most sea urchins is made up of five calcium carbonate teeth or jaws, with a fleshy, tongue-like structure within. The entire chewing organ is known as Aristotle's lantern ([http://www.chalk.discoveringfossils.co.uk/images/LanternBooth.jpg image]), from [[Aristotle]]'s description in his ''History of Animals'': |

|||

However, this has recently been proven to be a mistranslation. Aristotle's lantern is actually referring to the whole shape of sea urchins, which look like the ancient lamps of Aristotle's time.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Voultsiadou|first1=Eleni|last2=Chintiroglou|first2=Chariton|title=Aristotle's lantern in echinoderms: an ancient riddle|url=http://users.auth.gr/~elvoults/pdf/Aristotle%27s%20lantern%2008.pdf|year=2008|volume=49|pages=299–302|journal=Cahiers de Biologie Marine|publisher=Station Biologique de Roscoff|issue=3|access-date=2020-12-23|archive-date=2020-12-23|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201223165338/http://users.auth.gr/~elvoults/pdf/Aristotle%27s%20lantern%2008.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last1=Choi|first1=Charles Q.|title=Rock-Chewing Sea Urchins Have Self-Sharpening Teeth|url=https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/12/101228-sea-urchin-teeth-self-sharpening-tools-science-animals/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101231160917/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/12/101228-sea-urchin-teeth-self-sharpening-tools-science-animals/|url-status=dead|archive-date=December 31, 2010|website=National Geographic News|access-date=2017-11-12|date=29 December 2010}}</ref> |

|||

:...the urchin has what we mainly call its head and mouth down below, and a place for the issue of the residuum up above. The urchin has, also, five hollow teeth inside, and in the middle of these teeth a fleshy substance serving the office of a [[tongue]]. Next to this comes the [[esophagus]], and then the [[stomach]], divided into five parts, and filled with excretion, all the five parts uniting at the [[anus|anal]] vent, where the shell is perforated for an outlet... In reality the mouth-apparatus of the urchin is continuous from one end to the other, but to outward appearance it is not so, but looks like a horn [[lantern]] with the panes of horn left out. (Tr. [[D'Arcy Thompson]]) |

|||

[[Heart urchin]]s are unusual in not having a lantern. Instead, the mouth is surrounded by [[Cilium|cilia]] that pull strings of mucus containing food particles towards a series of grooves around the mouth.<ref name=IZ /> |

|||

However, this has recently been proven to be a mistranslation. Aristotle's lantern is actually referring to the whole shape of sea urchins, which look like the ancient lamps of Aristotle's time.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Voultsiadou|first1=Eleni|last2=Chintiroglou|first2=Chariton|title=Aristotle's lantern in echinoderms: an ancient riddle|url=http://www.sb-roscoff.fr/cbm/?execution=e3s3&_eventId=viewarticledetails&articleId=3394|year=2008|volume=49|pages=299–302|journal=Cahiers de Biologie Marine|publisher=Station Biologique de Roscoff|issue=3}}</ref><ref>http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/12/101228-sea-urchin-teeth-self-sharpening-tools-science-animals/, National Geographic: "Rock-Chewing Sea Urchins Have Self-Sharpening Teeth."</ref> |

|||

[[File:Echinoidea anatomie.svg|thumb|upright=1.1|Digestive and circulatory systems of a regular sea urchin:<br/>a = [[anus]]; m = [[madreporite]]; s = aquifer canal; r = radial canal; p = podial ampulla; k = test wall; i = [[intestine]]; b = mouth]] |

|||

[[Heart urchin]]s are unusual in not having a lantern. Instead, the mouth is surrounded by [[cilia]] that pull strings of mucus containing food particles towards a series of grooves around the mouth.<ref name=IZ /> |

|||

The lantern, where present, surrounds both the mouth cavity and the [[pharynx]]. At the top of the lantern, the pharynx opens into the esophagus, which runs back down the outside of the lantern, to join the small [[intestine]] and a single [[caecum]]. The small intestine runs in a full circle around the inside of the test, before joining the large intestine, which completes another circuit in the opposite direction. From the large intestine, a [[rectum]] ascends towards the anus. Despite the names, the small and large intestines of sea urchins are in no way [[homology (biology)|homologous]] to the similarly named structures in vertebrates.<ref name=IZ /> |

The lantern, where present, surrounds both the mouth cavity and the [[pharynx]]. At the top of the lantern, the pharynx opens into the esophagus, which runs back down the outside of the lantern, to join the small [[intestine]] and a single [[caecum]]. The small intestine runs in a full circle around the inside of the test, before joining the large intestine, which completes another circuit in the opposite direction. From the large intestine, a [[rectum]] ascends towards the anus. Despite the names, the small and large intestines of sea urchins are in no way [[homology (biology)|homologous]] to the similarly named structures in vertebrates.<ref name=IZ /> |

||

| Line 107: | Line 113: | ||

Digestion occurs in the intestine, with the caecum producing further digestive [[enzyme]]s. An additional tube, called the siphon, runs beside much of the intestine, opening into it at both ends. It may be involved in resorption of water from food.<ref name=IZ /> |

Digestion occurs in the intestine, with the caecum producing further digestive [[enzyme]]s. An additional tube, called the siphon, runs beside much of the intestine, opening into it at both ends. It may be involved in resorption of water from food.<ref name=IZ /> |

||

=== Circulation === |

=== Circulation and respiration === |

||

[[File:Diadema setosum (Kenya).JPG|thumb|''[[Diadema setosum]]'']] |

|||

[[File:Echinoidea anatomie.svg|thumb|upright=1.1|Anatomy of the circulatory system of a regular sea urchin.<br /> |

|||

a = [[anus]] ; |

|||

m = [[madreporite]] ; |

|||

s = aquifer canal ; |

|||

r = radial canal ; |

|||

p = podial ampulla ; |

|||

k = test wall ; |

|||

i = [[intestine]] ; |

|||

b = mouth.]] |

|||

Sea urchins possess both a [[water vascular system]] and a hemal system, the latter containing blood. However, the main circulatory fluid fills the general body cavity, or [[coelom]]. This fluid contains [[phagocyte|phagocytic]] coelomocytes, which move through the vascular and hemal systems. The coelomocytes are an essential part of [[blood clotting]], but also collect waste products and actively remove them from the body through the gills and tube feet.<ref name=IZ /> |

|||

The water vascular system leads downwards from the madreporite through the slender stone canal to the ring canal, which encircles the oesophagus. Radial canals lead from here through each ambulacral area to terminate in a small tentacle that passes through the ambulacral plate near the aboral pole. Lateral canals lead from these radial canals, ending in ampullae. From here, two tubes pass through a pair of pores on the plate to terminate in the tube feet.<ref name=Ruppert/> |

|||

=== Respiration === |

|||

Most sea urchins possess five pairs of external gills, located around their mouths. These thin-walled projections of the body cavity are the main organs of respiration in those urchins that possess them. Fluid can be pumped through the gills' interiors by muscles associated with the lantern, but this is not continuous, and occurs only when the animal is low on oxygen. Tube feet can also act as respiratory organs, and are the primary sites of gas exchange in heart urchins and sand dollars, both of which lack gills.<ref name=IZ /> |

|||

Sea urchins possess a hemal system with a complex network of vessels in the mesenteries around the gut, but little is known of the functioning of this system.<ref name=Ruppert/> However, the main circulatory fluid fills the general body cavity, or [[coelom]]. This coelomic fluid contains [[phagocyte|phagocytic]] coelomocytes, which move through the vascular and hemal systems and are involved in internal transport and gas exchange. The coelomocytes are an essential part of [[blood clotting]], but also collect waste products and actively remove them from the body through the gills and tube feet.<ref name=IZ /> |

|||

=== Nervous system === |

|||

[[File:Diadema setosum (Kenya).JPG|thumb|upright|The five white dots on this ''[[Diadema setosum]]'' are believed to be visual captors.]] |

|||

Most sea urchins possess five pairs of external gills attached to the peristomial membrane around their mouths. These thin-walled projections of the body cavity are the main organs of respiration in those urchins that possess them. Fluid can be pumped through the gills' interiors by muscles associated with the lantern, but this does not provide a continuous flow, and occurs only when the animal is low in oxygen. Tube feet can also act as respiratory organs, and are the primary sites of gas exchange in heart urchins and sand dollars, both of which lack gills. The inside of each tube foot is divided by a septum which reduces diffusion between the incoming and outgoing streams of fluid.<ref name=Ruppert/> |

|||

=== Nervous system and senses === |

|||

The nervous system of sea urchins has a relatively simple layout. With no true brain, the neural center is a large nerve ring encircling the mouth just inside the lantern. From the nerve ring, five nerves radiate underneath the radial canals of the water vascular system, and branch into numerous finer nerves to innervate the tube feet, spines, and [[pedicellariae]].<ref name=IZ /> |

The nervous system of sea urchins has a relatively simple layout. With no true brain, the neural center is a large nerve ring encircling the mouth just inside the lantern. From the nerve ring, five nerves radiate underneath the radial canals of the water vascular system, and branch into numerous finer nerves to innervate the tube feet, spines, and [[pedicellariae]].<ref name=IZ /> |

||

Sea urchins are sensitive to touch, light, and chemicals. There are numerous sensitive cells in the epithelium, especially in the spines, pedicellaria and tube feet, and around the mouth.<ref name=Ruppert/> Although they do not have eyes or eye spots (except for [[Diadematidae|diadematids]], which can follow a threat with their spines), the entire body of most regular sea urchins might function as a compound eye.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Knight |first1=K. |title=Sea Urchins Use Whole Body As Eye |journal=Journal of Experimental Biology |volume=213 |pages=i–ii |year=2009 |doi=10.1242/jeb.041715 |issue=2|doi-access=free }} |

|||

=== Senses === |

|||

*{{cite press release |author=Charles Q. Choi |date=December 28, 2009 |title=Body of Sea Urchin is One Big Eye |website=[[LiveScience]] |url=http://www.livescience.com/animals/091228-sea-urchin-eye.html}}</ref> In general, sea urchins are negatively attracted to light, and seek to hide themselves in crevices or under objects. Most species, apart from [[Cidaris|pencil urchins]], have [[statocyst]]s in globular organs called spheridia. These are stalked structures and are located within the ambulacral areas; their function is to help in gravitational orientation.<ref name=IZ /> |

|||

== |

== Life history == |

||

=== Reproduction === |

|||

=== Ingression of primary mesenchyme cells === |

|||

[[File:Sea Urchin |

[[File:Male Flower Sea Urchin (toxopneustes roseus).theora.ogv|thumb|Male flower urchin (''[[Toxopneustes roseus]]'') releasing milt, November 1, 2011, Lalo Cove, Sea of Cortez]] |

||

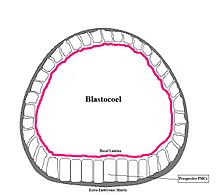

During early development, the sea urchin [[embryo]] undergoes 10 cycles of [[Cell Division|cell division]],<ref>{{cite journal|title =Arsenic Exposure Affects Embryo Development of Sea Urchin, Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck, 1816) | journal = Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology| pages = 1–5|date =2013 | last= A. Gaion|first = A. Scuderi|author2= D. Pellegrini|author3= D. Sartori | doi = 10.3109/01480545.2015.1041602}}</ref> resulting in a single [[epithelium|epithelial]] layer enveloping a [[Blastocoele|blastocoel]].<ref name=pmid15367199>{{cite journal |last1=Kominami |first1=Tetsuya |last2=Takata |first2=Hiromi |title=Gastrulation in the sea urchin embryo: a model system for analyzing the morphogenesis of a monolayered epithelium |journal=Development, growth & differentiation |volume=46 |issue=4 |pages=309–26 |year=2004 |doi=10.1111/j.1440-169x.2004.00755.x}}</ref> The embryo must then begin [[gastrulation]], a multipart process which involves the dramatic rearrangement and [[invagination]] of cells to produce the three [[germ layer]]s. |

|||

Sea urchins are [[Dioecy|dioecious]], having separate male and female sexes, although no distinguishing features are visible externally. In addition to their role in reproduction, the [[gonad]]s are also nutrient storing organs, and are made up of two main type of cells: [[germ cell]]s, and [[somatic cell]]s called nutritive phagocytes.<ref>{{Cite journal |pmc = 5090362|year = 2016|last1 = Gaitán-Espitia|first1 = J. D.|title = Functional insights into the testis transcriptome of the edible sea urchin Loxechinus albus|journal = Scientific Reports|volume = 6|pages = 36516|last2 = Sánchez|first2 = R.|last3 = Bruning|first3 = P.|last4 = Cárdenas|first4 = L.|pmid = 27805042|doi = 10.1038/srep36516|bibcode = 2016NatSR...636516G}}</ref> Regular sea urchins have five gonads, lying underneath the interambulacral regions of the test, while the irregular forms mostly have four, with the hindmost gonad being absent; heart urchins have three or two. Each gonad has a single duct rising from the upper pole to open at a [[gonopore]] lying in one of the genital plates surrounding the anus. Some burrowing sand dollars have an elongated papilla that enables the liberation of gametes above the surface of the sediment.<ref name=Ruppert/> The gonads are lined with muscles underneath the peritoneum, and these allow the animal to squeeze its [[gamete]]s through the duct and into the surrounding sea water, where [[fertilization]] takes place.<ref name=IZ /> |

|||

The first step of gastrulation is the [[Epithelial-mesenchymal transition|epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition]] and ingression of primary mesenchyme cells into the blastocoel.<ref name=pmid15367199 /> Primary [[mesenchyme]] cells, or PMCs, are located in the vegetal plate specified to become [[mesoderm]].<ref name=pmid14623443>{{cite journal |doi=10.1016/j.mod.2003.06.005 |last1=Shook |first1=D |last2=Keller |first2=R |title=Mechanisms, mechanics and function of epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in early development |journal=Mechanisms of development |volume=120 |issue=11 |pages=1351–83 |year=2003 |pmid=14623443}}</ref> Prior to ingression, PMCs exhibit all the features of other epithelial cells that comprise the embryo. Cells of the epithelium are bound basally to a laminal matrix and apically to an extraembryonic matrix.<ref name=pmid14623443 /> The apical [[Microvillus|microvilli]] of these cells reach into the hyaline layer, a component of the extraembryonic matrix.<ref name="Katow H 1980">{{cite journal |last1=Katow |first1=Hideki |last2=Solursh |first2=Michael |title=Ultrastructure of primary mesenchyme cell ingression in the sea urchinLytechinus pictus |journal=Journal of Experimental Zoology |volume=213 |pages=231–246 |year=1980 |doi=10.1002/jez.1402130211 |issue=2}}</ref> Neighboring epithelial cells are also connected to each other through [[Cell junction|apical junctions]],<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1016/0014-4827(59)90275-7 |last1=Balinsky |first1=BI |title=An electro microscopic investigation of the mechanisms of adhesion of the cells in a sea urchin blastula and gastrula |journal=Experimental Cell Research |pmid=13653007 |volume=16 |issue=2 |pages=429–33 |year=1959}}</ref> protein complexes containing adhesion molecules, such as [[cadherin]]s, linked to [[catenin]]s. |

|||

[[File:Sea Urchin Vegetal Plate.jpg|thumb|right|Vegetal plate|Prospective PMCs at vegetal plate]] |

|||

[[File:Ingression of PMC.jpg|thumb|Ingression of PMCs|Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and ingression of PMCs]] |

|||

=== Development === |

|||

As PMCs begin to undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, the lamina which binds them dissolves to begin the mechanical release of the cells.<ref name="Katow H 1980" /> Expression of the membrane protein that binds laminin, [[integrin]], also becomes irregular at the beginning of ingression.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Hertzler |first1=PL |last2=McClay |first2=DR |title=alphaSU2, an epithelial integrin that binds laminin in the sea urchin embryo |journal=Developmental Biology |volume=207 |issue=1 |pages=1–13 |year=1999 |pmid=10049560 |doi=10.1006/dbio.1998.9165}}</ref> The microvilli which secure PMCs to the hyaline layer shorten,<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1016/0012-1606(85)90376-8 |last1=Fink |first1=RD |last2=McClay |first2=DR |title=Three cell recognition changes accompany the ingression of sea urchin primary mesenchyme cells |pmid=2578117 |journal=Developmental Biology |volume=107 |issue=1 |pages=66–74 |year=1985}}</ref> as the cells reduce their affinity for the extraembryonic matrix.<ref name="Burdsal 1991">{{cite journal |doi=10.1016/0012-1606(91)90425-3 |last1=Burdsal |first1=CA |last2=Alliegro |first2=MC |last3=McClay |first3=DR |title=Tissue-specific, temporal changes in cell adhesion to echinonectin in the sea urchin embryo |pmid=1707016 |journal=Developmental Biology |volume=144 |issue=2 |pages=327–34 |year=1991}}</ref> These cells concurrently increase their affinity for other components of the basal matrix, such as [[fibronectin]], in part driving the movement of cells inward.<ref name="Burdsal 1991" /> The apical junctions which bind PMCs to their neighboring epithelial cells become disrupted during this transition, and are absent in cells that have fully ingressed into the blastocoel.<ref name="Katow H 1980" /> Because staining for cadherins and catenins in ingressing cells decreases and develops as intracellular accumulations, apical junctions are thought to be cleared by [[endocytosis]] during ingression.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Miller |first1=JR |last2=McClay |first2=DR |title=Characterization of the Role of Cadherin in Regulating Cell Adhesion during Sea Urchin Development |journal=Developmental Biology |volume=192 |issue=2 |pages=323–39 |year=1997 |pmid=9441671 |doi=10.1006/dbio.1997.8740}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Miller |first1=JR |last2=McClay |first2=DR |title=Changes in the pattern of adherens junction-associated beta-catenin accompany morphogenesis in the sea urchin embryo |journal=Developmental Biology |volume=192 |issue=2 |pages=310–22 |year=1997 |pmid=9441670 |doi=10.1006/dbio.1997.8739}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Sea Urchin Blastula.jpg|thumb|Sea urchin blastula]] |

|||

During early development, the sea urchin [[embryo]] undergoes 10 cycles of [[cell division]],<ref>{{cite journal|title =Arsenic Exposure Affects Embryo Development of Sea Urchin, Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck, 1816) | journal = Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology| volume = 39| issue = 2| pages = 124–8|date =2013 | last= A. Gaion|first = A. Scuderi|author2= D. Pellegrini|author3= D. Sartori | doi = 10.3109/01480545.2015.1041602| pmid = 25945412| s2cid = 207437380}}</ref> resulting in a single [[epithelium|epithelial]] layer enveloping the [[blastocoel]]. The embryo then begins [[gastrulation]], a multipart process which dramatically rearranges its structure by [[invagination]] to produce the three [[germ layer]]s, involving an [[epithelial-mesenchymal transition]]; primary [[mesenchyme]] cells move into the blastocoel<ref name=pmid15367199>{{cite journal |last1=Kominami |first1=Tetsuya |last2=Takata |first2=Hiromi |title=Gastrulation in the sea urchin embryo: a model system for analyzing the morphogenesis of a monolayered epithelium |journal=Development, Growth & Differentiation |volume=46 |issue=4 |pages=309–26 |year=2004 |doi=10.1111/j.1440-169x.2004.00755.x|pmid=15367199 |s2cid=23988213 }}</ref> and become [[mesoderm]].<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1016/j.mod.2003.06.005 |last1=Shook |first1=D |last2=Keller |first2=R |title=Mechanisms, mechanics and function of epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in early development |journal=Mechanisms of Development |volume=120 |issue=11 |pages=1351–83 |year=2003 |pmid=14623443|s2cid=15509972 |doi-access=free }}; {{cite journal |last1=Katow |first1=Hideki |last2=Solursh |first2=Michael |title=Ultrastructure of primary mesenchyme cell ingression in the sea urchinLytechinus pictus |journal=Journal of Experimental Zoology |volume=213 |pages=231–246 |year=1980 |doi=10.1002/jez.1402130211 |issue=2|bibcode=1980JEZ...213..231K }}; {{cite journal |doi=10.1016/0014-4827(59)90275-7 |last1=Balinsky |first1=BI |title=An electro microscopic investigation of the mechanisms of adhesion of the cells in a sea urchin blastula and gastrula |journal=Experimental Cell Research |pmid=13653007 |volume=16 |issue=2 |pages=429–33 |year=1959}}; {{cite journal |last1=Hertzler |first1=PL |last2=McClay |first2=DR |title=alphaSU2, an epithelial integrin that binds laminin in the sea urchin embryo |journal=Developmental Biology |volume=207 |issue=1 |pages=1–13 |year=1999 |pmid=10049560 |doi=10.1006/dbio.1998.9165|doi-access=free }}; {{cite journal |doi=10.1016/0012-1606(85)90376-8 |last1=Fink |first1=RD |last2=McClay |first2=DR |title=Three cell recognition changes accompany the ingression of sea urchin primary mesenchyme cells |pmid=2578117 |journal=Developmental Biology |volume=107 |issue=1 |pages=66–74 |year=1985}}; {{cite journal |doi=10.1016/0012-1606(91)90425-3 |last1=Burdsal |first1=CA |last2=Alliegro |first2=MC |last3=McClay |first3=DR |title=Tissue-specific, temporal changes in cell adhesion to echinonectin in the sea urchin embryo |pmid=1707016 |journal=Developmental Biology |volume=144 |issue=2 |pages=327–34 |year=1991}}; {{cite journal |last1=Miller |first1=JR |last2=McClay |first2=DR |title=Characterization of the Role of Cadherin in Regulating Cell Adhesion during Sea Urchin Development |journal=Developmental Biology |volume=192 |issue=2 |pages=323–39 |year=1997 |pmid=9441671 |doi=10.1006/dbio.1997.8740|doi-access=free }}; {{cite journal |last1=Miller |first1=JR |last2=McClay |first2=DR |title=Changes in the pattern of adherens junction-associated beta-catenin accompany morphogenesis in the sea urchin embryo |journal=Developmental Biology |volume=192 |issue=2 |pages=310–22 |year=1997 |pmid=9441670 |doi=10.1006/dbio.1997.8739|doi-access=free }}; {{cite journal |doi=10.1016/S0012-1606(89)80058-2 |last1=Anstrom |first1=JA |title=Sea urchin primary mesenchyme cells: ingression occurs independent of microtubules |journal=Developmental Biology |pmid=2562830 |volume=131 |issue=1 |pages=269–75 |year=1989}}; {{cite journal |last1=Anstrom |first1=JA |title=Microfilaments, cell shape changes, and the formation of primary mesenchyme in sea urchin embryos |journal=The Journal of Experimental Zoology |volume=264 |issue=3 |pages=312–22 |year=1992 |pmid=1358997 |doi=10.1002/jez.1402640310}}</ref> It has been suggested that [[epithelial polarity]] together with planar cell polarity might be sufficient to drive gastrulation in sea urchins.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Nissen | first1 = Silas Boye | last2 = Rønhild | first2 = Steven | last3 = Trusina | first3 = Ala | last4 = Sneppen | first4 = Kim | title=Theoretical tool bridging cell polarities with development of robust morphologies | journal=eLife | date=November 27, 2018 | volume=7 |pages=e38407 |doi=10.7554/eLife.38407 | pmid = 30477635 | pmc = 6286147 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

Once the PMCs disrupt all attachment to their former location, the cells themselves change their morphology by contracting their apical surfaces, [[apical constriction]], and enlarging their basal surfaces, thus acquiring a "bottle cell" phenotype.<ref name=pmid14623443 /> [[Cytoskeleton|Cytoskeletal]] rearrangements mediate the shape changes of PMCs; though the cytoskeleton assists in the mechanics of ingression, other mechanisms drive the process. Experimentally disrupting [[microtubule]] dynamics in the species ''Strongylocentrotus pupuratus'' by applying [[colchicine]] stalls the ingression of PMCs, but does not inhibit it.<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1016/S0012-1606(89)80058-2 |last1=Anstrom |first1=JA |title=Sea urchin primary mesenchyme cells: ingression occurs independent of microtubules |journal=Developmental Biology |pmid=2562830 |volume=131 |issue=1 |pages=269–75 |year=1989}}</ref> Similarly, experimentally disrupting actin-myosin contraction using inhibitors slows down ingression, but does not arrest the process.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Anstrom |first1=JA |title=Microfilaments, cell shape changes, and the formation of primary mesenchyme in sea urchin embryos |journal=The Journal of experimental zoology |volume=264 |issue=3 |pages=312–22 |year=1992 |pmid=1358997 |doi=10.1002/jez.1402640310}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Left-right asymmetry in the sea urchin - journal.pbio.1001404.g001.png|thumb|center|upright=2.7|The development of a regular sea urchin]] |

|||

The morphogenetic movements of the PMCs are an autonomous cellular behavior. Experimentally grafting PMCs into heterotopic tissue does not prevent the cells from ingressing.<ref name="Burdsal 1991" /> In studies where PMCs are cultured in insolation, the cells were observed to gain affinity for fibronectin and simultaneously lose affinity for extraembryonic matrix, independent of the embryonic environment.<ref name="Burdsal 1991" /> |

|||

An unusual feature of sea urchin development is the replacement of the larva's [[bilateral symmetry]] by the adult's broadly fivefold symmetry. During cleavage, mesoderm and small micromeres are specified. At the end of gastrulation, cells of these two types form [[coelom]]ic pouches. In the larval stages, the adult rudiment grows from the left coelomic pouch; after metamorphosis, that rudiment grows to become the adult. The [[Polarity in embryogenesis|animal-vegetal axis]] is established before the egg is fertilized. The oral-aboral axis is specified early in cleavage, and the left-right axis appears at the late gastrula stage.<ref name="WarnerLyons2012">{{cite journal |last1=Warner |first1=Jacob F. |last2=Lyons |first2=Deirdre C. |last3=McClay |first3=David R. |title=Left-Right Asymmetry in the Sea Urchin Embryo: BMP and the Asymmetrical Origins of the Adult |journal=PLOS Biology |volume=10 |issue=10 |year=2012 |pages=e1001404 |doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.1001404|pmid=23055829 |pmc=3467244 |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Left-right asymmetry in the sea urchin - journal.pbio.1001404.g001.png|thumb|center|upright=2.1|The development of a regular sea urchin.]] |

|||

== Life |

=== Life cycle and development === |

||

[[File:Echinocardium cordatum (Pennant, 1777) early pluteus width ca.JPEG|thumb|upright=0.6|''Pluteus'' larva has [[bilateral symmetry]].]] |

|||

At first glance, sea urchins often appear [[Sessility (zoology)|incapable of moving]]. Sometimes, the most visible life sign is the spines, which attach to ball-and-socket joints and can point in any direction. In most urchins, touch elicits a prompt reaction from the spines, which converge toward the touch point. Sea urchins have no visible eyes, legs, or means of propulsion, but can move freely over hard surfaces using adhesive tube feet, working in conjunction with the spines. Regular sea urchins don't have any favourite walking direction.<ref>Kazuya Yoshimura, Tomoaki Iketani et Tatsuo Motokawa, "Do regular sea urchins show preference in which part of the body they orient forward in their walk ?", ''Marine Biology'', vol. 159, no 5, 2012, p. 959-965.</ref> |

|||

In most cases, the female's eggs float freely in the sea, but some species hold onto them with their spines, affording them a greater degree of protection. The unfertilized egg meets with the free-floating sperm released by males, and develops into a free-swimming [[blastula]] embryo in as few as 12 hours. Initially a simple ball of cells, the blastula soon [[gastrulation|transforms]] into a cone-shaped '''echinopluteus''' larva. In most species, this larva has 12 elongated arms lined with bands of cilia that capture food particles and transport them to the mouth. In a few species, the blastula contains supplies of nutrient [[yolk]] and lacks arms, since it has no need to feed.<ref name=IZ /> |

|||

=== Reproduction === |

|||

[[File:Echinocardium cordatum (Pennant, 1777) early pluteus width ca.JPEG|thumb|upright=0.5|Sea urchin larva, called "''Pluteus''".]] |

|||

In most cases, the female's eggs float freely in the sea, but some species hold onto them with their spines, affording them a greater degree of protection. The fertilized egg, once met with the free-floating sperm released by males, develops into a free-swimming [[blastula]] embryo in as few as 12 hours. Initially a simple ball of cells, the blastula soon [[gastrulation|transforms]] into a cone-shaped '''echinopluteus''' larva. In most species, this larva has 12 elongated arms lined with bands of cilia that capture food particles and transport them to the mouth. In a few species, the blastula contains supplies of nutrient [[yolk]] and lacks arms, since it has no need to feed.<ref name=IZ /> |

|||

Several months are needed for the larva to complete its development, |

Several months are needed for the larva to complete its development, the change into the adult form beginning with the formation of test plates in a juvenile rudiment which develops on the left side of the larva, its axis being perpendicular to that of the larva. Soon, the larva sinks to the bottom and [[metamorphosis|metamorphoses]] into a juvenile urchin in as little as one hour.<ref name=Ruppert/> In some species, adults reach their maximum size in about five years.<ref name=IZ /> The [[Strongylocentrotus purpuratus|purple urchin]] becomes sexually mature in two years and may live for twenty.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Strongylocentrotus_purpuratus/|title=''Strongylocentrotus purpuratus''|website=Animal Diversity Web|year=2001|author=Worley, Alisa|access-date=2016-12-05|archive-date=2024-04-23|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240423125155/https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/strongylocentrotus_purpuratus/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

=== |

=== Longevity === |

||

[[Red sea urchin]]s were originally thought to live 7 to 10 years but recent studies have shown that they can live for more than 100 years. Canadian red urchins have been found to be around 200 years old.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.aquariumofpacific.org/onlinelearningcenter/species/red_sea_urchin#:~:text=Southern%20California%20red%20sea%20urchins,probably%20about%20200%20years%20old! | title=Red Sea Urchin | access-date=2023-05-18 | archive-date=2023-05-18 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230518000337/https://www.aquariumofpacific.org/onlinelearningcenter/species/red_sea_urchin#:~:text=Southern%20California%20red%20sea%20urchins,probably%20about%20200%20years%20old! | url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Ebert 2003">{{cite journal |author1=Thomas A. Ebert |author2=John R. Southon |name-list-style=amp |year=2003 |title=Red sea urchins (''Strongylocentrotus franciscanus'') can live over 100 years: confirmation with A-bomb <sup>14</sup>carbon |journal=[[Fishery Bulletin]] |volume=101 |issue=4 |pages=915–922 |url=http://fishbull.noaa.gov/1014/19ebertf.pdf |access-date=2023-05-18 |archive-date=2013-05-03 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130503065837/http://fishbull.noaa.gov/1014/19ebertf.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Wolf eel eating a sea urchin.jpg|thumb|upright=0.7|[[Anarrhichthys ocellatus|Wolf eel]] is a highly specialized predator of sea urchins.]] |

|||

Adult sea urchins are usually well protected against most predators by their strong and sharp spines, which can be poisonous in some species,<ref name="Defence – spines">{{cite web |url=http://www.nhm.ac.uk/research-curation/research/projects/echinoid-directory/intro/defence1.html |title=Defence – spines |date= |website=Echinoid Directory |publisher=[[Natural History Museum]] |accessdate=}}</ref> but when they are damaged they quickly attract lots of fish and other omnivorous animals. |

|||

== Ecology == |

|||

Sea urchins are one of the favourite food of many [[lobster]]s, [[crab]]s, [[balistidae|triggerfish]], [[California sheephead]], [[sea otter]] and [[Anarhichadidae|wolf eels]] : all these animals carry particular adaptations (teeth, pincers, claws) and a strength that allow them to overcome the excellent protective features of sea urchins. |

|||

=== Trophic level === |

|||

Sea urchins can also be infected by many [[parasite]]s, be they internal or external. [[Pedicellaria]]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nhm.ac.uk/research-curation/research/projects/echinoid-directory/intro/defence3.html |title=Defence – pedicellariae |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |date= |website=Echinoid Directory |publisher=[[Natural History Museum]] |accessdate=}}</ref> are a good means of defense against ectoparasites, but not a panacea as some of them actually feed on it.<ref>Hiroko Sakashita, " Sexual dimorphism and food habits of the clingfish, Diademichthys lineatus, and its dependence on host sea urchin ", Environmental Biology of Fishes, vol. 34, no 1, 1994, p. 95-101</ref> The hemal system ensures against endoparasites. |

|||

[[File:Sea Urchin.theora.ogv|thumb|Sea urchin in natural habitat]] |

|||

Sea urchins feed mainly on [[algae]], so they are primarily [[herbivore]]s, but can feed on sea cucumbers and a wide range of invertebrates, such as [[mussel]]s, [[polychaete]]s, [[sponge]]s, brittle stars, and crinoids, making them omnivores, consumers at a range of [[trophic level]]s.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Baumiller |first1=Tomasz K. |title=Crinoid Ecological Morphology |journal=Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences |volume=36 |pages=221–49 |year=2008 |doi=10.1146/annurev.earth.36.031207.124116 |bibcode=2008AREPS..36..221B}}</ref> |

|||

=== Predators, parasites, and diseases === |

|||

Mass mortality of sea urchins was first reported in the 1970s, but diseases in sea urchins had been little studied before the advent of aquaculture. In 1981, bacterial "spotting disease" caused almost complete mortality in juvenile ''[[Pseudocentrotus depressus]]'' and ''[[Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus]]'', both cultivated in Japan; the disease recurred in succeeding years. It was divided into a cool-water "spring" disease and a hot-water "summer" form.<ref name=Lawrence>{{cite book |author=Lawrence, John M. |title=Edible Sea Urchins: Biology and Ecology |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6T2JomruARoC |year=2006 |publisher=Elsevier |isbn=978-0-08-046558-6 |pages=167–168}}</ref> Another condition, [[bald sea urchin disease]], causes loss of spines and skin lesions and is believed to be bacterial in origin.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Diseases of Echinodermata. I. Agents microorganisms and protistans |journal=Diseases of Aquatic Organisms |volume=2 |year=1987 |author=Jangoux, Michel |pages=147–162 |doi=10.3354/dao002147|doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

Adult sea urchins are usually well protected against most predators by their strong and sharp spines, which can be venomous in some species.<ref name="Defence – spines">{{cite web |url=http://www.nhm.ac.uk/research-curation/research/projects/echinoid-directory/intro/defence1.html |title=Defence – spines |website=Echinoid Directory |publisher=[[Natural History Museum, London|Natural History Museum]] }}</ref> The small [[Diademichthys lineatus|urchin clingfish]] lives among the spines of urchins such as ''[[Diadema (sea urchin)|Diadema]]''; juveniles feed on the pedicellariae and sphaeridia, adult males choose the tube feet and adult females move away to feed on shrimp eggs and molluscs.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Sakashita, Hiroko |year=1992 |title=Sexual dimorphism and food habits of the clingfish, ''Diademichthys lineatus'', and its dependence on host sea urchin |journal=Environmental Biology of Fishes |volume=34 |issue=1 |pages=95–101 |doi=10.1007/BF00004787 |bibcode=1992EnvBF..34...95S |s2cid=32656986 }}</ref> |

|||

Sea urchins are one of the favourite foods of many [[lobster]]s, [[crab]]s, [[balistidae|triggerfish]], [[California sheephead]], [[sea otter]] and [[Anarhichadidae|wolf eels]] (which specialise in sea urchins). All these animals carry particular adaptations (teeth, pincers, claws) and a strength that allow them to overcome the excellent protective features of sea urchins. Left unchecked by predators, urchins devastate their environments, creating what biologists call an [[urchin barren]], devoid of macroalgae and associated [[fauna]].<ref>{{cite book|author1=Terborgh, John|author2=Estes, James A |title=Trophic Cascades: Predators, Prey, and the Changing Dynamics of Nature|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tjOT8KJ6mF8C&pg=PA38 |year=2013|publisher=Island Press |isbn=978-1-59726-819-6 |pages=38}}</ref> Sea urchins graze on the lower stems of kelp, causing the kelp to drift away and die. Loss of the habitat and nutrients provided by [[kelp forest]]s leads to profound [[Cascade effect (ecology)|cascade effects]] on the marine ecosystem. Sea otters have re-entered [[British Columbia]], dramatically improving coastal ecosystem health.<ref name=dfo>{{cite web |url=http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/species/species_seaOtter_e.asp |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080123224702/http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/species/species_seaOtter_e.asp |archive-date=2008-01-23|title=Aquatic Species at Risk – Species Profile – Sea Otter |publisher=[[Fisheries and Oceans Canada]] |access-date=2007-11-29}}</ref> |

|||

<gallery style="text-align:center;" mode="packed"> |

<gallery style="text-align:center;" mode="packed"> |

||

File:Wolf eel eating a sea urchin.jpg|[[Anarrhichthys ocellatus|Wolf eel]], a highly specialized predator of sea urchins |

|||

File:Sea otter with sea urchin.jpg|A [[sea otter]] feeding on a [[Strongylocentrotus purpuratus|purple sea urchin]]. |

File:Sea otter with sea urchin.jpg|A [[sea otter]] feeding on a [[Strongylocentrotus purpuratus|purple sea urchin]]. |

||

File:Carpilius convexus is consuming Heterocentrotus trigonarius in Hawaii.jpg|A crab (''[[Carpilius convexus]]'') attacking a slate pencil sea urchin (''[[Heterocentrotus mamillatus]]'') |

File:Carpilius convexus is consuming Heterocentrotus trigonarius in Hawaii.jpg|A marbled stone crab (''[[Carpilius convexus]]'') attacking a slate pencil sea urchin (''[[Heterocentrotus mamillatus]]'') |

||

File:Saddle Wrasse are feeding on sea urchin in Kona.jpg|A [[Thalassoma duperrey|wrasse]] finishing the remains of a damaged ''[[Tripneustes gratilla]]'' |

File:Saddle Wrasse are feeding on sea urchin in Kona.jpg|A [[Thalassoma duperrey|wrasse]] finishing the remains of a damaged ''[[Tripneustes gratilla]]'' |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

=== Anti-predator defences === |

|||

== Ecology == |

|||

[[File: |

[[File:Flower urchin by Vincent C Chen.jpg|thumb|The [[flower urchin]] is a dangerous, potentially lethally venomous species.]] |

||

Sea urchins feed mainly on [[algae]] but can feed on sea cucumbers and a wide range of [[invertebrates]], such as [[mussels]], [[polychaete]]s, [[sponges]], [[brittle stars]], and [[crinoids]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Baumiller |first1=Tomasz K. |title=Crinoid Ecological Morphology |journal=Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences |volume=36 |pages=221–49 |year=2008 |doi=10.1146/annurev.earth.36.031207.124116 |bibcode=2008AREPS..36..221B}}</ref> Population densities vary by habitat, with more dense populations in barren areas as compared to [[kelp]] stands.<ref name=Mattison1977>{{cite journal |author1=Mattison, JE |author2=Trent, JD |author3=Shanks, AL |author4=Akin, TB |author5=Pearse, JS |title=Movement and feeding activity of red sea urchins (''Strongylocentrotus franciscanus'') adjacent to a kelp forest |journal=Marine Biology |volume=39 |pages=25–30 |year=1977 |doi=10.1007/BF00395589 |issue=1}}</ref><ref name=Konar2000>{{cite journal |author=Konar, Brenda |title=Habitat influences on sea urchin populations |journal=In: Hallock and French (eds). Diving for Science...2000. Proceedings of the 20th Annual Scientific Diving Symposium |publisher=[[American Academy of Underwater Sciences]] |year=2000 |url=http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/8990 |accessdate=2011-01-07}}</ref> Even in these barren areas, greatest densities are found in shallow water. Populations are generally found in deeper water if wave action is present.<ref name=Konar2000 /> Densities decrease in winter when storms cause them to seek protection in cracks and around larger underwater structures.<ref name=Konar2000 /> |

|||

The [[spine (zoology)|spines]], long and sharp in some species, protect the urchin from [[predator]]s. Some tropical sea urchins like [[Diadematidae]], [[Echinothuriidae]] and [[Toxopneustidae]] have venomous spines. Other creatures also make use of these defences; crabs, shrimps and other organisms shelter among the spines, and often adopt the colouring of their host. Some crabs in the [[Dorippidae]] family carry sea urchins, starfish, sharp shells or other protective objects in their claws.<ref name=Thiel>{{cite book|author1=Thiel, Martin|author2=Watling, Les|title=Lifestyles and Feeding Biology |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RZ-eBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA200 |year=2015 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-979702-8 |pages=200–202}}</ref> |

|||

Sea urchins are some of the favorite foods of [[sea otter]]s and [[California sheephead]], and are the main source of nutrition for [[wolf eel]]s. Left unchecked, urchins devastate their environments, creating what biologists call an [[urchin barren]], devoid of macroalgae and associated [[fauna]]. Sea otters have re-entered [[British Columbia]], dramatically improving coastal ecosystem health.<ref name=dfo>{{cite web|url=http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/species/species_seaOtter_e.asp|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080123224702/http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/species/species_seaOtter_e.asp|archivedate=2008-01-23|title=Aquatic Species at Risk – Species Profile – Sea Otter|publisher=[[Fisheries and Oceans Canada]]|accessdate=2007-11-29}}</ref> |

|||

[[Pedicellaria]]e<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nhm.ac.uk/research-curation/research/projects/echinoid-directory/intro/defence3.html |title=Defence – pedicellariae |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |website=Echinoid Directory |publisher=[[Natural History Museum, London|Natural History Museum]] |access-date=2014-08-04 |archive-date=2014-10-06 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141006072057/http://www.nhm.ac.uk/research-curation/research/projects/echinoid-directory/intro/defence3.html |url-status=live }}</ref> are a good means of defense against ectoparasites, but not a panacea as some of them actually feed on it.<ref>Hiroko Sakashita, " Sexual dimorphism and food habits of the clingfish, Diademichthys lineatus, and its dependence on host sea urchin ", Environmental Biology of Fishes, vol. 34, no 1, 1994, p. 95–101</ref> The hemal system defends against endoparasites.<ref>{{cite journal |url=https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%252FBF01989305.pdf |title=Diseases of echinoderms |journal=Helgoländer Meeresuntersuchungen |volume=37 |issue=1–4 |pages=207–216 |author=Jangoux, M. |year=1984 |access-date=23 March 2018 |bibcode=1984HM.....37..207J |doi=10.1007/BF01989305 |s2cid=21863649 |doi-access=free |archive-date=29 October 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201029002716/https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%252FBF01989305.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

=== Range and habitat === |

|||