Shiva: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Rv to last version by "Errerless" because I don't know how to add multiple citations in infobox. Tags: Manual revert Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ |

{{Short description|Major deity in Hinduism}} |

||

{{about|the Hindu god|other uses|Shiva (Judaism)|and|Shiva (disambiguation)}} |

|||

{{redirect-multi|2|Nilkanth|Manjunatha}} |

|||

{{good article}} |

|||

{{pp|small=yes}} |

|||

{{EngvarB|date=March 2015}} |

{{EngvarB|date=March 2015}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date= |

{{Use dmy dates|date=June 2023}} |

||

{{Infobox deity |

|||

{{good article}} |

|||

| type = Hindu |

|||

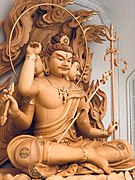

| image = Bangalore Shiva.jpg |

|||

{{Infobox deity <!--Wikipedia:WikiProject Hindu mythology--> |

|||

| caption = Statue of Shiva at [[Shivoham Shiva Temple]], Bangalore, Karnataka |

|||

| type = Hindu |

|||

| day = {{hlist|[[Monday]]|[[Thrayodashi]]}} |

|||

| image = Lord Shiva Images - An artistic representation of Lord Shiva and the 12 Jyotirlingas associated with him.jpg |

|||

| mantra = *[[Om Namah Shivaya]] |

|||

| image_size = 250px |

|||

*[[Mahamrityunjaya Mantra]] |

|||

| caption = An artistic representation of Shiva, surrounded by 12 ''Jyotirlingas'' |

|||

| affiliation = {{hlist|[[Trimurti]]|[[Ishvara]]|[[Parabrahman]]|[[Paramatman]] (Shaivism)}} |

|||

| Devanagari = शिव |

|||

| deity_of = God of Destruction |

|||

| Sanskrit_Transliteration = {{IAST|Śiva}} |

|||

{{hlist|God of [[Kāla|Time]]|[[Yogeshvara|Lord of Yogis]]<ref>{{Cite encyclopaedia|title=Yogeshvara|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KItocaxbibUC&q=%28Yogesha%29&pg=PA112|year=1998|encyclopaedia=Indian Civilization and Culture|publisher=M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd|isbn=978-81-7533-083-2|pages=115}}</ref>|[[Nataraja|The Cosmic Dancer]]|Patron of [[Yoga]], [[Meditation]] and [[Arts]]{{sfn|Varenne|1976|pp=82}}|Master of Poison and Medicine<ref>{{cite book| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KItocaxbibUC |title=Indian Civilization and Culture| year=1998| publisher=M.D. Publications Pvt. |isbn=9788175330832 |page=116}}</ref>{{sfn|Dalal|2010|pp=436}}}} |

|||

| Kannada_Transliteration = ಶಿವ |

|||

[[Para Brahman|The Supreme Being]] ([[Shaivism]])<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia|title=Hinduism |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dbibAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA445|year=2008 |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of World Religions|publisher=Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.|isbn=978-1593394912 |pages=445–448}}</ref> |

|||

| Telugu_Transliteration =శివుడు |

|||

| weapon = *[[Trishula]] |

|||

| Tamil_Transliteration = சிவன் |

|||

*[[Pashupatastra]] |

|||

| mantra = [[Om Namah Shivaya]] |

|||

*[[Parashu]] |

|||

| deity_of = God of Creation, Destruction, Regeneration, [[Meditation]], [[Arts]], [[Yoga]] and [[Moksha]] |

|||

*[[Pinaka (Hinduism)|Pinaka bow]]{{sfn|Fuller|2004|p=58}} |

|||

| affiliation = [[Brahman|Supreme Being]] ([[Shaivism]]), [[Trimurti]], [[Deva (Hinduism)|Deva]] |

|||

| symbols = {{hlist|[[Lingam]]{{sfn|Fuller|2004|p=58}}|[[Crescent|Crescent Moon]]|[[Tripundra]]|[[Damaru]]|[[Vasuki]]|[[Third eye]]}} |

|||

| weapon = [[Trishula]] |

|||

| children = {{unbulleted list| |

|||

| symbols = [[Lingam]] |

|||

*[[Kartikeya]] (son){{sfn|Cush|Robinson|York|2008|p=78}} |

|||

| consort = [[Parvati]] |

|||

*[[Ganesha]] (son){{sfn|Williams|1981|p=62}} |

|||

| children = [[Ganesha]], [[Kartikeya]] |

|||

*''[[:Category:Children of Shiva|See list of others]]''}} |

|||

| abode = [[Mount Kailash]] |

|||

| abode = * [[Kailasa]]{{sfn|Zimmer|1972|pp=124–126}} |

|||

| mount = [[Nandi (bull)|Nandi]] |

|||

*[[Shmashana]] |

|||

| festivals = [[Maha Shivaratri]], [[Bhairava Ashtami]]. |

|||

| mount = [[Nandi (Hinduism)|Nandi]]{{sfn|Javid|2008|pp=20–21}} |

|||

| festivals = {{hlist|[[Maha Shivaratri]]|[[Shravana (month)|Shravana]]|[[Kartik Purnima]]|[[Pradosha]]|[[Teej]]|[[Bhairava Ashtami]]{{sfn|Dalal|2010|pp=137, 186}}}} |

|||

| other_names = {{hlist|[[Bhairava]]|Mahadeva|[[Mahakala]]|Maheśvara|[[Pashupati]]|[[Rudra]]|Shambhu|Shankara}} |

|||

| member_of = [[Trimurti]]{{sfn|Zimmer|1972|pp=124}} |

|||

| consort = [[Sati (Hindu goddess)|Sati]], [[Parvati]] and other [[:Category:Forms of Parvati|forms]] of [[Shakti]]{{refn|group=note|In scriptures, Shiva is paired with [[Shakti]], the embodiment of power; who is known under various manifestations as Uma, Sati, Parvati, [[Durga]], and [[Kali]].<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Shiva | title=Shiva | Definition, Forms, God, Symbols, Meaning, & Facts | Britannica | date=10 August 2024 }}</ref> Sati is generally regarded as the first wife of Shiva, who reincarnated as Parvati after her death. Out of these forms of Shakti, Parvati is considered the main consort of Shiva.{{sfn|Kinsley|1998|p=35}}}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Contains Indic text}} |

|||

'''Shiva''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|ʃ|ɪ|v|ə}}; {{langx|sa|शिव|lit=The Auspicious One}}, {{IAST3|Śiva}} {{IPA|sa|ɕɪʋɐ|}}<!-- Do not remove, WP:INDICSCRIPT doesn't apply to WikiProject Hinduism -->), also known as '''Mahadeva''' ({{IPAc-en|m|ə|'|h|ɑː|_|'|d|ei|v|ə}}; {{Langx|sa|महादेव:|lit=The Great God}}, {{IAST3|Mahādevaḥ}}, [[Help:IPA/Sanskrit|[mɐɦaːd̪eːʋɐh]]){{Sfn|Sharma|2000|p=65}}{{Sfn|Issitt|Main|2014|pp=147, 168}}{{Sfn|Flood|1996|p=151}} or '''Hara''',{{sfn|Sharma|1996|p=314}} is one of the [[Hindu deities|principal deities]] of [[Hinduism]].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.outlookindia.com/national/shiva-in-mythology-let-s-reimagine-the-lord-magazine-231225|title=Shiva In Mythology: Let's Reimagine The Lord|date=28 October 2022 |access-date=30 October 2022|archive-date=30 October 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221030120611/https://www.outlookindia.com/national/shiva-in-mythology-let-s-reimagine-the-lord-magazine-231225|url-status=live}}</ref> He is the [[God in Hinduism|Supreme Being]] in [[Shaivism]], one of the major traditions within Hinduism.{{sfnm|Flood|1996|1pp=17, 153|Sivaraman|1973|2p=131}} |

|||

'''''Shiva''''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|ʃ|i|v|ə}}; [[IAST]]: {{IAST|Śiva}}, lit. ''the auspicious one'') is one of the [[Hindu deities|principal deities]] of [[Hinduism]]. He is the supreme God within [[Shaivism]], one of the three most influential denominations in contemporary Hinduism.<ref name="Flood 1996, p. 17">{{harvnb|Flood|1996|pp=17, 153}}</ref><ref>Tattwananda, p. 45.</ref> |

|||

Shiva is |

Shiva is known as ''The Destroyer'' within the [[Trimurti]], the [[Hinduism|Hindu]] trinity which also includes [[Brahma]] and [[Vishnu]].{{sfn|Zimmer|1972|pp=124–126}}{{sfn|Gonda|1969}} In the Shaivite tradition, Shiva is the Supreme Lord who creates, protects and transforms the universe.{{Sfn|Sharma|2000|p=65}}{{Sfn|Issitt|Main|2014|pp=147, 168}}{{Sfn|Flood|1996|p=151}} In the goddess-oriented [[Shaktism|Shakta]] tradition, the Supreme Goddess ([[Devi]]) is regarded as the energy and creative power ([[Shakti]]) and the equal complementary partner of Shiva.{{sfn|Kinsley|1988|pp=50, 103–104}}{{sfn|Pintchman|2015|pp=113, 119, 144, 171}} Shiva is one of the five equivalent deities in [[Panchayatana puja]] of the [[Smarta Tradition|Smarta]] tradition of Hinduism.{{sfn|Flood|1996|pp=17, 153}} |

||

Shiva has many aspects, benevolent as well as fearsome. In benevolent aspects, he is depicted as an [[Omniscience|omniscient]] [[Yogi]] who lives an [[Asceticism#Hinduism|ascetic life]] on [[Kailasa]]{{sfn|Zimmer|1972|pp=124–126}} as well as a householder with his wife [[Parvati]] and his two children, [[Ganesha]] and [[Kartikeya]]. In his fierce aspects, he is often depicted slaying demons. Shiva is also known as Adiyogi (the first [[Yogi]]), regarded as the patron god of [[yoga]], [[Meditation#Hinduism|meditation]] and the arts.<ref>''Shiva Samhita'', e.g. {{harvnb|Mallinson|2007}}; {{harvnb|Varenne|1976|p=82}}; {{harvnb|Marchand|2007}} for Jnana Yoga.</ref> The iconographical attributes of Shiva are the serpent king [[Vasuki]] around his neck, the adorning [[crescent]] moon, the [[holy river]] [[Ganga]] flowing from his matted hair, the [[third eye]] on his forehead (the eye that turns everything in front of it into ashes when opened), the [[trishula]] or trident as his weapon, and the [[damaru]]. He is usually worshiped in the [[aniconic]] form of [[lingam]].{{sfn|Fuller|2004|p=58}} |

|||

Shiva has pre-Vedic roots,{{sfnm|Sadasivan|2000|1p=148|Sircar|1998|2pp=3 with footnote 2, 102–105}} and the figure of Shiva evolved as an amalgamation of various older non-Vedic and Vedic deities, including the [[Rigvedic deity|Rigvedic]] [[wind god|storm god]] [[Rudra]] who may also have non-Vedic origins,{{Sfn|Flood|1996|p=152}} into a single major deity.{{sfnm|Flood|1996|1pp=148–149|Keay|2000|2p=xxvii|Granoff|2003|3pp=95–114|Nath|2001|4p=31}} Shiva is a pan-Hindu deity, revered widely by Hindus in [[Hinduism in India|India]], [[Hinduism in Nepal|Nepal]], [[Hinduism in Bangladesh|Bangladesh]], [[Hinduism in Sri Lanka|Sri Lanka]] and [[Hinduism in Indonesia|Indonesia]] (especially in [[Java]] and [[Bali]]).{{sfnm|Keay|2000|1p=xxvii|Flood|1996|2p=17}} |

|||

The main iconographical attributes of Shiva are the [[third eye]] on his forehead, the serpent around his neck, the adorning [[crescent]] moon, the holy river [[Ganga]] flowing from his matted hair, the [[trishula]] as his weapon and the [[damaru]]. Shiva is usually worshipped in the [[aniconic]] form of [[Lingam]].<ref name=Fuller>Fuller, p. 58.</ref> Shiva is a pan-Hindu deity, revered widely by Hindus, in [[India]], [[Nepal]] and [[Sri Lanka]].{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=17}}<ref name="Keayxxvii">Keay, p.xxvii.</ref> |

|||

{{Saivism}} |

|||

== Etymology and other names == |

== Etymology and other names == |

||

{{Main |

{{Main|Shiva Sahasranama}} |

||

According to the [[Monier Monier-Williams|Monier-Williams]] Sanskrit dictionary, the word "{{transliteration|sa|ISO|śiva}}" ({{langx|sa|शिव|label=[[Devanagari]]}}, also transliterated as ''shiva'') means "auspicious, propitious, gracious, benign, kind, benevolent, friendly".<ref name="mmwshiva">Monier Monier-Williams (1899), [http://www.ibiblio.org/sripedia/ebooks/mw/1100/mw__1107.html Sanskrit to English Dictionary with Etymology] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170227192855/http://www.ibiblio.org/sripedia/ebooks/mw/1100/mw__1107.html |date=27 February 2017 }}, Oxford University Press, pp. 1074–1076</ref> The root words of {{transliteration|sa|ISO|śiva}} in folk etymology are ''śī'' which means "in whom all things lie, pervasiveness" and ''va'' which means "embodiment of grace".<ref name="mmwshiva" />{{sfn|Prentiss|2000|p=199}} |

|||

[[File:Siva With Moustache From Archaeological Museum GOA IMG 20141222 122455775.jpg|thumb|200px|A [[mukhalinga]] sculpture of Shiva depicting him with a moustache]] |

|||

The Sanskrit word "Śiva" ([[Devanagari]]: {{lang|sa|शिव}}, transliterated as Shiva or Siva) means, states Monier Williams, "auspicious, propitious, gracious, benign, kind, benevolent, friendly".<ref name=mmwshiva>Monier Monier-Williams (1899), [http://www.ibiblio.org/sripedia/ebooks/mw/1100/mw__1107.html Sanskrit to English Dictionary with Etymology], Oxford University Press, pages 1074–1076</ref> The roots of Śiva in folk etymology is "śī" which means "in whom all things lie, pervasiveness" and ''va'' which means "embodiment of grace".<ref name=mmwshiva/><ref>{{cite book|author=Karen Pechilis Prentiss|title=The Embodiment of Bhakti|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Vu95WgeUBfEC&pg=PA199|year=2000|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-535190-3|page=199}}</ref> |

|||

The word Shiva is used as an adjective in the Rig Veda, as an epithet for several [[Rigvedic deities]], including [[Rudra]].<ref>For use of the term ''{{ |

The word Shiva is used as an adjective in the [[Rig Veda]] ({{Circa|1700–1100 BCE}}), as an epithet for several [[Rigvedic deities]], including [[Rudra]].<ref>For use of the term ''{{transliteration|sa|ISO|śiva}}'' as an epithet for other Vedic deities, see: {{harvnb|Chakravarti|1986|p=28}}.</ref> The term Shiva also connotes "liberation, final emancipation" and "the auspicious one"; this adjectival usage is addressed to many deities in Vedic literature.<ref name="mmwshiva" />{{Sfn|Chakravarti|1986|pp=21–22}} The term evolved from the Vedic ''Rudra-Shiva'' to the noun ''Shiva'' in the Epics and the Puranas, as an auspicious deity who is the "creator, reproducer and dissolver".<ref name="mmwshiva" />{{Sfn|Chakravarti|1986|pp=1, 7, 21–23}} |

||

Sharma presents another etymology with the Sanskrit root ''{{ |

Sharma presents another etymology with the [[Sanskrit]] root ''{{transliteration|sa|ISO|śarv}}-'', which means "to injure" or "to kill",<ref>For root ''{{transliteration|sa|ISO|śarv}}-'' see: {{harvnb|Apte|1965|p=910}}.</ref> interpreting the name to connote "one who can kill the forces of darkness".{{Sfn|Sharma|1996|p=306}} |

||

The Sanskrit word ''{{ |

The [[Sanskrit literature|Sanskrit]] word ''{{transliteration|sa|ISO|śaiva}}'' means "relating to the god Shiva", and this term is the Sanskrit name both for one of the principal sects of Hinduism and for a member of that sect.{{sfn|Apte|1965|p=927}} It is used as an adjective to characterize certain beliefs and practices, such as Shaivism.<ref>For the definition "Śaivism refers to the traditions which follow the teachings of {{transliteration|sa|ISO|Śiva}} (''{{transliteration|sa|ISO|śivaśāna}}'') and which focus on the deity {{transliteration|sa|ISO|Śiva}}... " see: {{harvnb|Flood|1996|p=149}}</ref> |

||

Some authors associate the name with the [[Tamil language|Tamil word]] ''{{IAST|śivappu}}'' meaning "red", noting that Shiva is linked to the Sun (''{{IAST|śivan}}'', "the Red one", in Tamil) and that Rudra is also called ''Babhru'' (brown, or red) in the Rigveda.<ref>{{cite book|last1=van Lysebeth|first1=Andre|title=Tantra: Cult of the Feminine|date=2002|publisher=Weiser Books|isbn= |

Some authors associate the name with the [[Tamil language|Tamil word]] ''{{IAST|śivappu}}'' meaning "red", noting that Shiva is linked to the Sun (''{{IAST|śivan}}'', "the Red one", in Tamil) and that Rudra is also called ''Babhru'' (brown, or red) in the Rigveda.<ref>{{cite book|last1=van Lysebeth|first1=Andre|title=Tantra: Cult of the Feminine|date=2002|publisher=Weiser Books|isbn=978-0877288459|page=213|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=R4W-DivEweIC&pg=FA213|access-date=2 July 2015|archive-date=31 March 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240331131657/https://books.google.com/books?id=R4W-DivEweIC&pg=FA213|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Tyagi|first1=Ishvar Chandra|title=Shaivism in Ancient India: From the Earliest Times to C.A.D. 300|publisher=Meenakshi Prakashan|year=1982|page=81|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WH3XAAAAMAAJ|access-date=2 July 2015|archive-date=31 March 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240331131704/https://books.google.com/books?id=WH3XAAAAMAAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> The ''[[Vishnu sahasranama]]'' interprets ''Shiva'' to have multiple meanings: "The Pure One", and "the One who is not affected by three Guṇas of Prakṛti (Sattva, Rajas, and Tamas)".{{sfnm|Sri Vishnu Sahasranama|1986|1pp=47, 122|Chinmayananda|2002|2p=24}} |

||

Shiva is known by many names such |

Shiva is known by many names such as Viswanatha (lord of the universe), Mahadeva, Mahandeo,{{sfn|Powell|2016|p=27}} Mahasu,{{sfn|Berreman|1963|p=[https://archive.org/details/hindusofhimalaya00inberr/page/385 385]}} Mahesha, Maheshvara, Shankara, Shambhu, Rudra, Hara, Trilochana, Devendra (chief of the gods), Neelakanta, Subhankara, Trilokinatha (lord of the three realms),<ref name="Manmatha">For translation see: {{harvnb|Dutt|1905|loc=Chapter 17 of Volume 13}}.</ref><ref name="Kisari">For translation see: {{harvnb|Ganguli|2004|loc=Chapter 17 of Volume 13}}.</ref><ref name="Chidbhav">{{harvnb|Chidbhavananda|1997}}, ''Siva Sahasranama Stotram''.</ref> and Ghrneshwar (lord of compassion).{{sfn|Lochtefeld|2002|p=247}} The highest reverence for Shiva in Shaivism is reflected in his epithets ''{{transliteration|sa|ISO|Mahādeva}}'' ("Great god"; ''{{transliteration|sa|ISO|mahā}}'' "Great" and ''deva'' "god"),{{sfn|Kramrisch|1994a|p=476}}<ref>For appearance of the name {{lang|sa|महादेव}} in the ''Shiva Sahasranama'' see: {{Harvnb|Sharma|1996|p=297}}</ref> ''{{transliteration|sa|ISO|Maheśvara}}'' ("Great Lord"; ''{{transliteration|sa|ISO|mahā}}'' "great" and ''{{transliteration|sa|ISO|īśvara}}'' "lord"),{{sfn|Kramrisch|1994a|p=477}}<ref>For appearance of the name in the Shiva Sahasranama see: {{Harvnb|Sharma|1996|p=299}}</ref> and ''[[Parameshwara (god)|{{transliteration|sa|ISO|Parameśvara}}]]'' ("Supreme Lord").<ref>For {{transliteration|sa|ISO|Parameśhvara}} as "Supreme Lord" see: {{harvnb|Kramrisch|1981|p=479}}.</ref> |

||

Sahasranama are medieval Indian texts that list a thousand names derived from aspects and epithets of a deity.<ref name=mmwsahasran>Sir Monier Monier-Williams, ''sahasranAman'', A Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages, Oxford University Press (Reprinted: Motilal Banarsidass), ISBN |

[[Sahasranama]] are medieval Indian texts that list a thousand names derived from aspects and epithets of a deity.<ref name="mmwsahasran">Sir Monier Monier-Williams, ''sahasranAman'', A Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages, Oxford University Press (Reprinted: Motilal Banarsidass), {{ISBN|978-8120831056}}</ref> There are at least eight different versions of the ''Shiva Sahasranama'', devotional hymns (''[[stotras]]'') listing many names of Shiva.<ref>{{Harvnb|Sharma|1996|pp=viii–ix}}</ref> The version appearing in Book 13 ({{transliteration|sa|ISO|''Anuśāsanaparvan''}}) of the ''[[Mahabharata]]'' provides one such list.{{efn|This is the source for the version presented in Chidbhavananda, who refers to it being from the Mahabharata but does not explicitly clarify which of the two Mahabharata versions he is using. See {{harvnb|Chidbhavananda|1997|p=5}}.}} Shiva also has ''Dasha-Sahasranamas'' (10,000 names) that are found in the ''Mahanyasa''. The ''Shri Rudram Chamakam'', also known as the ''Śatarudriya'', is a devotional hymn to Shiva hailing him by many names.<ref>For an overview of the ''Śatarudriya'' see: {{harvnb|Kramrisch|1981|pp=71–74}}.</ref><ref>For complete Sanskrit text, translations, and commentary see: {{harvnb|Sivaramamurti|1976}}.</ref> |

||

== Historical development and literature == |

== Historical development and literature == |

||

[[File:Elephanta Caves Trimurti.jpg|thumb|200px|An ancient sculpture of Shiva at the [[Elephanta Caves]], Maharashtra. 6th century CE]]{{See also|History of Shaivism|l1=}} |

|||

{{See also|Shaivism#History|l1=History of Shaivism}} |

|||

The Shiva-related tradition is a major part of Hinduism, found all over India, [[Nepal]], [[Sri Lanka]],{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=17}}<ref name="Keayxxvii">Keay, p.xxvii.</ref> and Bali (Indonesia).<ref>{{cite book|author=James A. Boon|title=The Anthropological Romance of Bali 1597–1972|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=AzI7AAAAIAAJ |year=1977|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-21398-1|pages=143, 205}}</ref> Its historical roots are unclear and contested. Some scholars such Yashodhar Mathpal and Ali Javid have interpreted early prehistoric paintings at the [[Bhimbetka rock shelters]], carbon dated to be from pre-10,000 BCE period,<ref>{{Citation | title=A Survey of Hinduism, 3rd Edition | author=Klaus K. Klostermaier | authorlink = Klaus Klostermaier | year=2007 | isbn=978-0-7914-7082-4 | publisher=State University of University Press | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=E_6-JbUiHB4C | pages=24–25| quote=''... prehistoric cave paintings at Bhimbetka (from ca. 100,000 to ca. 10,000 BCE) which were discovered only in 1967...''}}</ref> as Shiva dancing, Shiva's trident, and his mount Nandi.<ref name="Javidd2008">{{cite book|last=Javid| first= Ali|title=World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=54XBlIF9LFgC&pg=PA21&|date=January 2008|publisher=Algora Publishing|isbn=978-0-87586-484-6|pages=20–21}}</ref><ref name="Mathpal1984">{{cite book|last=Mathpal|first=Yashodhar|authorlink=Yashodhar Mathpal|title=Prehistoric Rock Paintings of Bhimbetka, Central India|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GG7-CpvlU30C&pg=FA220|year=1984|publisher=Abhinav Publications|isbn=978-81-7017-193-5|page=220}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Rajarajan|first=R.K.K.|year=1996|title=Vṛṣabhavāhanamūrti in Literature and Art|url=https://www.academia.edu/12964639/V%E1%B9%9B%E1%B9%A3abhav%C4%81hanam%C5%ABrti_in_Literature_and_Art|journal=Annali del Istituto Orientale, Naples|volume=56.3|pages=56.3: 305-10|via=}}</ref> However, Howard Morphy states that these prehistoric rock paintings of India, when seen in their context, are likely those of hunting party with animals, and that the figures in a group dance can be interpreted in many different ways.<ref>{{cite book|author=Howard Morphy|title=Animals Into Art|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XhchBQAAQBAJ |year=2014|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-317-59808-4|pages=364–366}}</ref> Rock paintings from Bhimbetka, depicting a figure with a [[trishul]], have been described as Nataraja by Erwin Neumayer, who dates them to the [[mesolithic]].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Neumayer|first1=Erwin|title=Prehistoric Rock Art of India|date=2013|publisher=OUP India|isbn=9780198060987|page=104 |url=https://www.harappa.com/content/prehistoric-rock-art-india |accessdate=1 March 2017}}</ref> |

|||

=== Assimilation of traditions === |

|||

===Indus Valley origins=== |

|||

{{See also|Hinduism#Roots of Hinduism|l1=Roots of Hinduism}}The Shiva-related tradition is a major part of Hinduism, found all over the [[Indian subcontinent]], such as India, [[Nepal]], [[Sri Lanka]],{{sfnm|Flood|1996|1p=17|Keay|2000|2p=xxvii}} and [[Southeast Asia]], such as [[Bali, Indonesia]].{{sfn|Boon|1977|pp=143, 205}} Shiva has pre-Vedic tribal roots,{{sfnm|Sadasivan|2000|1p=148|Sircar|1998|2pp=3 with footnote 2, 102–105}} having "his origins in primitive tribes, signs and symbols."{{sfn|Sadasivan|2000|p=148}} The figure of Shiva as he is known today is an amalgamation of various older deities into a single figure, due to the process of [[Sanskritization]] and the emergence of the [[Hindu synthesis]] in post-Vedic times.{{sfnm|Flood|1996|1pp=148–149|Keay|2000|2p=xxvii|Granoff|2003|3pp=95–114}} How the persona of Shiva converged as a composite deity is not well documented, a challenge to trace and has attracted much speculation.<ref>For Shiva as a composite deity whose history is not well documented, see {{harvnb|Keay|2000|p=147}}</ref> According to Vijay Nath: |

|||

{{Main article|Pashupati seal}} |

|||

{{blockquote|Vishnu and Siva [...] began to absorb countless local cults and deities within their folds. The latter were either taken to represent the multiple facets of the same god or else were supposed to denote different forms and appellations by which the god came to be known and worshipped. [...] Siva became identified with countless local cults by the sheer suffixing of ''Isa'' or ''Isvara'' to the name of the local deity, e.g., Bhutesvara, Hatakesvara, Chandesvara."{{sfn|Nath|2001|p=31}}}} |

|||

[[File:Shiva Pashupati.jpg|upright|thumb|200px|Seal discovered during excavation of the [[Indus Valley Civilization|Indus Valley]] archaeological site in the Indus Valley has drawn attention as a possible representation of a "yogi" or "proto-Shiva" figure.]] |

|||

An example of assimilation took place in [[Maharashtra]], where a regional deity named [[Khandoba]] is a patron deity of farming and herding [[caste]]s.{{sfn|Courtright|1985|p=205}} The foremost center of worship of Khandoba in Maharashtra is in [[Jejuri]].<ref>For Jejuri as the foremost center of worship see: {{harvnb|Mate|1988|p=162}}.</ref> Khandoba has been assimilated as a form of Shiva himself,{{sfn|Sontheimer|1976|pp=180–198|ps=: "Khandoba is a local deity in Maharashtra and been Sanskritised as an incarnation of Shiva."}} in which case he is worshipped in the form of a lingam.{{sfn|Courtright|1985|p=205}}<ref>For worship of Khandoba in the form of a lingam and possible identification with Shiva based on that, see: {{harvnb|Mate|1988|p=176}}.</ref> Khandoba's varied associations also include an identification with [[Surya]]{{sfn|Courtright|1985|p=205}} and [[Karttikeya]].<ref>For use of the name Khandoba as a name for Karttikeya in Maharashtra, see: {{harvnb|Gupta|1988|loc=''Preface'', and p. 40}}.</ref> |

|||

Many Indus valley seals show animals but one seal that has attracted attention shows a figure, either horned or wearing a horned headdress and possibly [[ithyphallic]]<ref name="Figure 1 1996 p. 29">For a drawing of the seal see Figure 1 ''in'': Flood (1996), p. 29.</ref><ref>Singh, S.P., ''Rgvedic Base of the Pasupati Seal of Mohenjo-Daro''(Approx 2500–3000 BC), Puratattva 19: 19–26. 1989</ref><ref>Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark. ''Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization''. Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1998.</ref> figure seated in a posture reminiscent of the [[Lotus position]] and surrounded by animals was named by early excavators of [[Mohenjo-daro]] ''[[Pashupati]]'' (lord of cattle), an epithet of the later [[Hindu deities|Hindu gods]] Shiva and Rudra.<ref name="Figure 1 1996 p. 29"/><ref>{{cite book| title = The Making of India: A Historical Survey| author = Ranbir Vohra| publisher = M.E. Sharpe| year = 2000| page = 15}}</ref><ref>{{cite book| title = Ancient Indian Civilization| author = Grigoriĭ Maksimovich Bongard-Levin| publisher = Arnold-Heinemann| year = 1985| page = 45}}</ref><ref>{{cite book| title = Essential Hinduism|author1=Steven Rosen |author2=Graham M. Schweig | publisher = Greenwood Publishing Group| year = 2006| page = 45}}</ref> <!-- [[Sir John Marshall]] and others have claimed that this figure is a prototype of Shiva and have described the figure as having three faces seated in a "yoga posture" with the knees out and feet joined.{{citation needed|date=June 2016}} --> |

|||

Myths about Shiva that were "roughly contemporary with early [[Christianity]]" existed that portrayed Shiva with many differences than how he is thought of now,{{sfn|Hopkins|2001|p=243}} and these mythical portrayals of Shiva were incorporated into later versions of him. For instance, he and the other [[Hindu deities|gods]], from the highest gods to the least powerful gods, were thought of as somewhat human in nature, creating [[emotion]]s they had limited control over and having the ability to get in touch with their inner natures through [[asceticism]] like humans.{{sfn|Hopkins|2001|pp=243-244, 261}} In that era, Shiva was widely viewed as both the god of [[lust]] and of asceticism.{{sfn|Hopkins|2001|p=244}} In one story, he was seduced by a [[Prostitution|prostitute]] sent by the other gods, who were jealous of Shiva's ascetic lifestyle he had lived for 1000 years.{{sfn|Hopkins|2001|p=243}} |

|||

Some academics like [[Gavin Flood]]{{sfn|Flood|1996|pp=28–29}}{{sfn|Flood|2003|pp=204–205}} and [[John Keay]] have expressed doubts about this claim. John Keay writes that "He may indeed be an early manifestation of Lord Shiva as Pashu-pati", but a couple of his specialties of this figure does not match with Rudra.<ref>{{cite book|title=India: A History|publisher=Grove Press|author=John Keay|page=14}}</ref> Writing in 1997 [[Doris Meth Srinivasan]] rejected Marshall's package of proto-Shiva features, including that of three heads. She interprets what [[John Marshall (archaeologist)|John Marshall]] interpreted as facial as not human but more bovine, possibly a divine buffalo-man.<ref>{{cite book|last=Srinivasan|first=Doris Meth|title=Many Heads, Arms and Eyes: Origin, Meaning and Form in Multiplicity in Indian Art|year=1997|publisher=Brill|isbn=978-9004107588}}</ref> |

|||

=== Pre-Vedic elements === |

|||

Writing in 2002, Gregory L. Possehl concluded that while it would be appropriate to recognize the figure as a deity, its association with the water buffalo, and its posture as one of ritual discipline, regarding it as a proto-Shiva would "go too far."<ref>{{cite book|last=Possehl|first=Gregory L. |authorlink=Gregory Possehl|title=The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XVgeAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA154|date=11 November 2002|publisher=Rowman Altamira|isbn=978-0-7591-1642-9|ref=harv|pages=140–144}}</ref> |

|||

==== Prehistoric art ==== |

|||

A seal discovered during excavation of the [[Mohenjodaro|Mohenjo-daro]] archaeological site in the [[Indus Valley Civilization|Indus Valley]] has drawn attention as a possible representation of a "proto-Shiva" figure.<ref name="Flood 1996, pp. 28-29">Flood (1996), pp. 28–29.</ref> This "Pashupati" (Lord of Animals, [[Sanskrit]] ''{{IAST|paśupati}}'')<ref>For translation of ''{{IAST|paśupati}}'' as "Lord of Animals" see: Michaels, p. 312.</ref> seal shows a large central figure that is surrounded by animals. The central figure is often described as a seated figure, possibly [[phallic|ithyphallic]], surrounded by animals.<ref name="Figure 1 1996 p. 29"/> [[John Marshall (archaeologist)|Sir John Marshall]] and others have claimed that this figure is a prototype of Shiva, and have described the figure as having three faces, seated in a "[[yoga]] posture" with the knees out and feet joined. Semi-circular shapes on the head are often interpreted as two horns. [[Gavin Flood]] characterizes these views as "speculative", saying that while it is not clear from the seal that the figure has three faces, is seated in a yoga posture, or even that the shape is intended to represent a human figure, it is nevertheless possible that there are echoes of Shaiva [[iconographic]] themes, such as half-moon shapes resembling the horns of a [[bull]].<ref name="Flood 1996, pp. 28-29"/><ref>Flood (2003), pp. 204–205.</ref> |

|||

Prehistoric rock paintings dating to the [[Mesolithic]] from [[Bhimbetka rock shelters]] have been interpreted by some authors as depictions of Shiva.{{sfn|Neumayer|2013|p=104}}{{efn|reference=Temporal range for Mesolithic in South Asia is from 12000 to 4000 years [[before present]]. The term "Mesolithic" is not a useful term for the periodization of the South Asian Stone Age, as certain [[Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes|tribes]] in the interior of the Indian subcontinent retained a mesolithic culture into the modern period, and there is no consistent usage of the term. The range 12,000–4,000 Before Present is based on the combination of the ranges given by Agrawal et al. (1978) and by Sen (1999), and overlaps with the early Neolithic at [[Mehrgarh]]. D.P. Agrawal et al., "Chronology of Indian prehistory from the Mesolithic period to the Iron Age", ''Journal of Human Evolution'', Volume 7, Issue 1, January 1978, 37–44: "A total time bracket of c. 6,000–2,000 B.C. will cover the dated Mesolithic sites, e.g. Langhnaj, Bagor, '''Bhimbetka''', Adamgarh, Lekhahia, etc." (p. 38). S.N. Sen, [https://books.google.com/books?id=Wk4_ICH_g1EC&pg=PA23 ''Ancient Indian History and Civilization''], 1999: "The Mesolithic period roughly ranges between 10,000 and 6,000 B.C." (p. 23).}} However, Howard Morphy states that these prehistoric rock paintings of India, when seen in their context, are likely those of hunting party with animals, and that the figures in a group dance can be interpreted in many different ways.<ref>{{cite book |author=Howard Morphy |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XhchBQAAQBAJ |title=Animals Into Art |publisher=Routledge |year=2014 |isbn=978-1-317-59808-4 |pages=364–366 |access-date=30 January 2024 |archive-date=31 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240331131700/https://books.google.com/books?id=XhchBQAAQBAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

==== Indus Valley and the Pashupati seal ==== |

|||

===Indo-Aryan origins=== |

|||

{{Main |

{{Main|Pashupati seal}} |

||

[[File:Shiva Pashupati.jpg|upright|thumb|200px|The [[Pashupati seal]] discovered during excavation of the [[Indus Valley civilisation|Indus Valley]] archaeological site of [[Mohenjo-Daro]] and showing a possible representation of a "yogi" or "proto-Shiva" figure as [[Pashupati|Paśupati]] (Lord of the Animals" {{Circa|2350}}–2000 BCE]] |

|||

The similarities between the iconography and theologies of Shiva with Greek and European deities have led to proposals for an Indo-European link for Shiva,<ref name=woodward60/><ref>{{cite book|author=Alain Daniélou|title=Gods of Love and Ecstasy: The Traditions of Shiva and Dionysus|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QDQK7l13WIIC |year=1992|publisher=Inner Traditions / Bear & Co|isbn=978-0-89281-374-2|pages=49–50}}, Quote: "The parallels between the names and legends of Shiva, Osiris and Dionysus are so numerous that there can be little doubt as to their original sameness".</ref> or lateral exchanges with ancient central Asian cultures.<ref>{{cite book|author=Namita Gokhale|title=The Book of Shiva|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pFN15nX9_zsC|year=2009|publisher=Penguin Books|isbn=978-0-14-306761-0|pages=10–11}}</ref><ref>Pierfrancesco Callieri (2005), [http://www.jstor.org/stable/29757637 A Dionysian Scheme on a Seal from Gupta India], East and West, Vol. 55, No. 1/4 (December 2005), pages 71–80</ref> His contrasting aspects such as being terrifying or blissful depending on the situation, are similar to those of the Greek god [[Dionysus]],<ref>{{cite journal | last=Long | first=J. Bruce | title=Siva and Dionysos: Visions of Terror and Bliss | journal=Numen | volume=18 | issue=3 | year=1971 | page=180 | doi=10.2307/3269768 }}</ref> as are their iconic associations with bull, snakes, anger, bravery, dancing and carefree life.<ref name=flahertyds81/><ref>{{cite book|author=Patrick Laude|title=Divine Play, Sacred Laughter, and Spiritual Understanding|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cTDIAAAAQBAJ |year=2005|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|isbn=978-1-4039-8058-8|pages=41–60}}</ref> The ancient Greek texts of the time of Alexander the Great call Shiva as "Indian Dionysius", or alternatively call Dionysius as "god of the Orient".<ref name=flahertyds81>Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty (1980), [http://www.jstor.org/stable/1062337 Dionysus and Siva: Parallel Patterns in Two Pairs of Myths], History of Religions, Vol. 20, No. 1/2 (Aug. – Nov., 1980), pages 81–111</ref> Similarly, the use of phallic symbol as an icon for Shiva is also found for Irish, Nordic, Greek (Dionysus<ref>{{cite book|author1=Walter Friedrich Otto|author2=Robert B. Palmer|title=Dionysus: Myth and Cult|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XCDvuoZ8IzsC&pg=PA164 |year=1965|publisher=Indiana University Press|isbn=0-253-20891-2|page=164}}</ref>) and Roman deities, as was the idea of this aniconic column linking heaven and earth among early Indo-Aryans, states Roger Woodward.<ref name=woodward60>{{cite book|author=Roger D. Woodard|title=Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EB4fB0inNYEC |year=2010|publisher=University of Illinois Press|isbn=978-0-252-09295-4|pages=60–67, 79–80}}</ref> Others contest such proposals, and suggest Shiva to have emerged from indigenous pre-Aryan tribal origins.<ref>{{cite book|author=Dineschandra Sircar|title=The Śākta Pīṭhas|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=I969qn5fpvcC&pg=PA3 |year=1998|publisher=Motilal Banarsidass|isbn=978-81-208-0879-9|pages=3 with footnote 2, 102–105}}</ref> |

|||

Of several Indus valley seals that show animals, one seal that has attracted attention shows a large central figure, either [[horned deity|horned]] or wearing a horned headdress and possibly [[ithyphallic]],{{refn|group=note|name="ilph_rep_l"}}<ref>{{harvnb|Singh|1989}}; {{harvnb|Kenoyer|1998}}. For a drawing of the seal see Figure 1 in {{harvnb|Flood|1996|p=29}}</ref> seated in a posture reminiscent of the [[Lotus position]], surrounded by animals. This figure was named by early excavators of [[Mohenjo-daro]] as ''[[Pashupati]]'' (Lord of Animals, [[Sanskrit]] ''{{transliteration|sa|ISO|paśupati}}''),<ref>For translation of ''{{transliteration|sa|ISO|paśupati}}'' as "Lord of Animals" see: {{harvnb|Michaels|2004|p=312}}.</ref> an epithet of the later [[Hindu deities]] Shiva and Rudra.{{sfnm|Vohra|2000|p=[https://archive.org/details/makingindiahisto00vohr/page/n10 15]|Bongard-Levin|1985|2p=45|3a1=Rosen|3a2=Schweig|3y=2006|3p=45}} [[John Marshall (archaeologist)|Sir John Marshall]] and others suggested that this figure is a prototype of Shiva, with three faces, seated in a "[[yoga]] posture" with the knees out and feet joined.{{sfn|Flood|1996|pp=28–29}} Semi-circular shapes on the head were interpreted as two horns. Scholars such as [[Gavin Flood]], [[John Keay]] and [[Doris Meth Srinivasan]] have expressed doubts about this suggestion.{{sfnm|Flood|1996|1pp=28–29|Flood|2003|2pp=204–205|Srinivasan|1997|3p=181}} |

|||

===Vedic origins=== |

|||

The Vedic literature refers to a minor atmospheric deity, with fearsome powers called Rudra. The Rigveda, for example, has 3 out of 1,028 hymns dedicated to Rudra, and he finds occasional mention in other hymns of the same text.{{Sfn|Chakravarti|1986|pp=1–2}} The term Shiva also appears in the Rigveda, but simply as an epithet that means "kind, auspicious", one of the adjectives used to describe many different Vedic deities. While fierce ruthless natural phenomenon and storm-related Rudra is feared in the hymns of the Rigveda, the beneficial rains he brings are welcomed as Shiva aspect of him.{{Sfn|Chakravarti|1986|pp=2–3}} This healing, nurturing, life-enabling aspect emerges in the Vedas as Rudra-Shiva, and in post-Vedic literature ultimately as Shiva who combines the destructive and constructive powers, the terrific and the pacific, as the ultimate recycler and rejuvenator of all existence.{{Sfn|Chakravarti|1986|pp=1–9}} |

|||

[[Gavin Flood]] states that it is not clear from the seal that the figure has three faces, is seated in a yoga posture, or even that the shape is intended to represent a human figure. He characterizes these views as "speculative", but adds that it is nevertheless possible that there are echoes of Shaiva [[iconographic]] themes, such as half-moon shapes resembling the horns of a [[bull]].{{sfnm|Flood|1996|1pp=28–29|Flood|2003|2pp=204–205}} John Keay writes that "he may indeed be an early manifestation of Lord Shiva as Pashu-pati", but a couple of his specialties of this figure does not match with Rudra.{{sfn|Keay|2000|p=14}} Writing in 1997, Srinivasan interprets what [[John Marshall (archaeologist)|John Marshall]] interpreted as facial as not human but more bovine, possibly a divine buffalo-man.{{sfn|Srinivasan|1997|p=181}} |

|||

====Rudra==== |

|||

The interpretation of the seal continues to be disputed. [[McEvilley]], for example, states that it is not possible to "account for this posture outside the yogic account".<ref>{{Cite journal|last=McEvilley|first=Thomas|date=1981-03-01|title=An Archaeology of Yoga| journal=Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics| volume=1| page =51| doi= 10.1086/RESv1n1ms20166655|s2cid=192221643|issn=0277-1322 }}</ref> Asko Parpola states that other archaeological finds such as the early Elamite seals dated to 3000–2750 BCE show similar figures and these have been interpreted as "seated bull" and not a yogi, and the bovine interpretation is likely more accurate.<ref>Asko Parpola(2009), Deciphering the Indus Script, Cambridge University Press, {{ISBN|978-0521795661}}, pp. 240–250</ref> Gregory L. Possehl in 2002, associated it with the water buffalo, and concluded that while it would be appropriate to recognize the figure as a deity, and its posture as one of ritual discipline, regarding it as a proto-Shiva would "go too far".<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XVgeAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA154|title=The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective|last=Possehl|first=Gregory L.|date=2002|publisher=Rowman Altamira|isbn=978-0759116429|pages=140–144|author-link=Gregory Possehl|access-date=2 July 2015|archive-date=20 January 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230120224137/https://books.google.com/books?id=XVgeAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA154|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

==== Proto-Indo-European elements ==== |

|||

The Vedic beliefs and practices of the pre-classical era were closely related to the hypothesised [[Proto-Indo-European religion]],<ref name="Woodard2006">{{cite book|author=Roger D. Woodard|title=Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EB4fB0inNYEC&pg=FA242|date=2006|publisher=University of Illinois Press|isbn=978-0252092954|pages=242–}}</ref> and the pre-Islamic Indo-Iranian religion.{{sfn|Beckwith|2009|p=32}} The similarities between the iconography and theologies of Shiva with Greek and European deities have led to proposals for an [[Proto-Indo-European religion|Indo-European]] link for Shiva,<ref name=woodward60 /><ref>{{cite book|author=Alain Daniélou|title=Gods of Love and Ecstasy: The Traditions of Shiva and Dionysus|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QDQK7l13WIIC |year=1992|publisher=Inner Traditions / Bear & Co|isbn=978-0892813742|pages=49–50}}, Quote: "The parallels between the names and legends of Shiva, Osiris and Dionysus are so numerous that there can be little doubt as to their original sameness".</ref> or lateral exchanges with ancient central Asian cultures.<ref>{{cite book|author=Namita Gokhale|title=The Book of Shiva|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pFN15nX9_zsC|year=2009|publisher=Penguin Books|isbn=978-0143067610|pages=10–11}}</ref><ref>Pierfrancesco Callieri (2005), [https://www.jstor.org/stable/29757637 A Dionysian Scheme on a Seal from Gupta India] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161220104032/http://www.jstor.org/stable/29757637 |date=20 December 2016 }}, East and West, Vol. 55, No. 1/4 (December 2005), pp. 71–80</ref> His contrasting aspects such as being terrifying or blissful depending on the situation, are similar to those of the Greek god [[Dionysus]],<ref>{{cite journal | last=Long | first=J. Bruce | title=Siva and Dionysos: Visions of Terror and Bliss | journal=Numen | volume=18 | issue=3 | pages=180–209 | year=1971 | doi=10.2307/3269768 | jstor=3269768 | issn = 0029-5973}}</ref> as are their iconic associations with bull, snakes, anger, bravery, dancing and carefree life.<ref name=flahertyds81 /><ref>{{cite book|author=Patrick Laude|title=Divine Play, Sacred Laughter, and Spiritual Understanding|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cTDIAAAAQBAJ|year=2005|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|isbn=978-1403980588|pages=41–60|access-date=6 October 2016|archive-date=31 March 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240331131700/https://books.google.com/books?id=cTDIAAAAQBAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> The ancient Greek texts of the time of Alexander the Great call Shiva "Indian Dionysus", or alternatively call Dionysus ''"god of the Orient"''.<ref name=flahertyds81>Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty (1980), [https://www.jstor.org/stable/1062337 Dionysus and Siva: Parallel Patterns in Two Pairs of Myths] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161220102525/http://www.jstor.org/stable/1062337 |date=20 December 2016 }}, History of Religions, Vol. 20, No. 1/2 (Aug. – Nov., 1980), pp. 81–111</ref> Similarly, the use of phallic symbol{{refn|group=note|name="ilph_rep_l"}} as an icon for Shiva is also found for Irish, Nordic, Greek (Dionysus<ref>{{cite book|author1=Walter Friedrich Otto|author2=Robert B. Palmer|title=Dionysus: Myth and Cult|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XCDvuoZ8IzsC&pg=PA164 |year=1965|publisher=Indiana University Press|isbn=0253208912|page=164}}</ref>) and Roman deities, as was the idea of this aniconic column linking heaven and earth among early Indo-Aryans, states Roger Woodward.<ref name=woodward60>{{cite book|author=Roger D. Woodard|title=Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EB4fB0inNYEC |year=2010|publisher=University of Illinois Press|isbn=978-0252-092954|pages=60–67, 79–80}}</ref> Others contest such proposals, and suggest Shiva to have emerged from indigenous pre-Aryan tribal origins.{{sfn|Sircar|1998|pp=3 with footnote 2, 102–105}} |

|||

==== Rudra ==== |

|||

[[File:ThreeHeadedShivaGandhara2ndCentury.jpg|upright|thumb|200px|Three-headed Shiva, Gandhara, 2nd century AD]] |

[[File:ThreeHeadedShivaGandhara2ndCentury.jpg|upright|thumb|200px|Three-headed Shiva, Gandhara, 2nd century AD]] |

||

Shiva as we know him today shares many features with the Vedic god [[Rudra]],<ref name="Michaels, p. 316">Michaels, p. 316.</ref> and both Shiva and Rudra are viewed as the same personality in [[Hindu texts|Hindu scriptures]]. The two names are used synonymously. Rudra, the god of the roaring [[storm]], is usually portrayed in accordance with the element he represents as a fierce, destructive deity.<ref>Flood (2003), p. 73.</ref> |

|||

Shiva as we know him today shares many features with the Vedic god [[Rudra]],{{sfn|Michaels|2004|p=316}} and both Shiva and Rudra are viewed as the same personality in [[Hindu texts|Hindu scriptures]]. The two names are used synonymously. Rudra, a [[Rigvedic deity]] with fearsome powers, was the god of the roaring [[storm]]. He is usually portrayed in accordance with the element he represents as a fierce, destructive deity.{{sfn|Flood|2003|p=73}} In RV 2.33, he is described as the "Father of the [[Rudras]]", a group of storm gods.<ref>Doniger, pp. 221–223.</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Rudra {{!}} Hinduism, Shiva, Vedas {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Rudra |access-date=2024-06-08 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

Flood notes that Rudra is an ambiguous god, peripheral in the Vedic pantheon, possibly indicating non-Vedic origins.{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=152}} Nevertheless, both Rudra and Shiva are akin to [[Odin|Wodan]], the Germanic God of rage ("wütte") and the [[wild hunt]].{{sfnm|Zimmer|2000|p=186}}{{sfn|Storl|2004}}{{page needed|date=April 2022}}{{sfn|Winstedt|2020}}{{page needed|date=April 2022}} |

|||

According to Sadasivan, during the development of the [[Hindu synthesis]] attributes of the Buddha were transferred by Brahmins to Shiva, who was also linked with [[Rudra]].{{Sfn|Sadasivan|2000|p=148}} The Rigveda has 3 out of 1,028 hymns dedicated to Rudra, and he finds occasional mention in other hymns of the same text.{{Sfn|Chakravarti|1986|pp=1–2}} Hymn 10.92 of the Rigveda states that deity Rudra has two natures, one wild and cruel (Rudra), another that is kind and tranquil (Shiva).{{sfn|Kramrisch|1994a|p=7}} |

|||

The term Shiva also appears simply as an epithet, that means "kind, auspicious", one of the adjectives used to describe many different Vedic deities. While fierce ruthless natural phenomenon and storm-related Rudra is feared in the hymns of the Rigveda, the beneficial rains he brings are welcomed as Shiva aspect of him.{{Sfn|Chakravarti|1986|pp=2–3}} This healing, nurturing, life-enabling aspect emerges in the Vedas as Rudra-Shiva, and in post-Vedic literature ultimately as Shiva who combines the destructive and constructive powers, the terrific and the gentle, as the ultimate recycler and rejuvenator of all existence.{{Sfn|Chakravarti|1986|pp=1–9}} |

|||

The Vedic texts do not mention bull or any animal as the transport vehicle (''vahana'') of Rudra or other deities. However, post-Vedic texts such as the Mahabharata and the Puranas state the Nandi bull, the Indian [[zebu]], in particular, as the vehicle of Rudra and of Shiva, thereby unmistakably linking them as same.{{sfn|Kramrisch|1994a|pp=14–15}} |

|||

==== Agni ==== |

==== Agni ==== |

||

Rudra and Agni have a close relationship. |

[[Rudra]] and [[Agni]] have a close relationship.{{refn|group=note|For a general statement of the close relationship, and example shared epithets, see: {{harvnb|Sivaramamurti|1976|p=11}}. For an overview of the Rudra-Fire complex of ideas, see: {{harvnb|Kramrisch|1981|pp=15–19}}.}} The identification between Agni and Rudra in the Vedic literature was an important factor in the process of Rudra's gradual transformation into Rudra-Shiva.{{refn|group=note|For quotation "An important factor in the process of Rudra's growth is his identification with Agni in the Vedic literature and this identification contributed much to the transformation of his character as {{transliteration|sa|ISO|Rudra-Śiva}}." see: {{harvnb|Chakravarti|1986|p=17}}.}} The identification of [[Agni]] with Rudra is explicitly noted in the ''[[Nirukta]]'', an important early text on etymology, which says, "Agni is also called Rudra."<ref>For translation from ''Nirukta'' 10.7, see: {{harvnb|Sarup|1998|p=155}}.</ref> The interconnections between the two deities are complex, and according to Stella Kramrisch: |

||

{{ |

{{blockquote|The fire myth of {{transliteration|sa|ISO|Rudra-Śiva}} plays on the whole gamut of fire, valuing all its potentialities and phases, from conflagration to illumination.{{sfn|Kramrisch|1994a|p=18}}}} |

||

In the [[Shri Rudram Chamakam|''Śatarudrīya'']], some epithets of Rudra, such as {{ |

In the [[Shri Rudram Chamakam|''Śatarudrīya'']], some epithets of Rudra, such as {{transliteration|sa|ISO|Sasipañjara}} ("Of golden red hue as of flame") and {{transliteration|sa|ISO|Tivaṣīmati}} ("Flaming bright"), suggest a fusing of the two deities.{{refn|group=note|For "Note Agni-Rudra concept fused" in epithets {{transliteration|sa|ISO|Sasipañjara}} and {{transliteration|sa|ISO|Tivaṣīmati}} see: {{harvnb|Sivaramamurti|1976|p=45}}.}} Agni is said to be a bull,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/rigveda/rv06048.htm |title=Rig Veda: Rig-Veda, Book 6: HYMN XLVIII. Agni and Others |publisher=Sacred-texts.com |access-date=2010-06-06 |archive-date=25 March 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100325222509/http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/rigveda/rv06048.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> and Shiva possesses a bull as his vehicle, [[Nandi (bull)|Nandi]]. The horns of [[Agni]], who is sometimes characterized as a bull, are mentioned.<ref>For the parallel between the horns of Agni as bull, and Rudra, see: {{harvnb|Chakravarti|1986|p=89}}.</ref><ref>RV 8.49; 10.155.</ref> In medieval sculpture, both [[Agni]] and the form of Shiva known as [[Bhairava]] have flaming hair as a special feature.<ref>For flaming hair of Agni and Bhairava see: Sivaramamurti, p. 11.</ref> |

||

==== Indra ==== |

==== Indra ==== |

||

[[File: |

[[File:Pashupatinath Temple-2020.jpg|thumb|[[Pashupatinath Temple]], [[Nepal]], dedicated to Shiva as the lord of all beings]] |

||

According to [[Wendy Doniger]], the Saivite fertility myths and some of the phallic characteristics of Shiva are inherited from [[Indra]].<ref>{{cite book|last =Doniger|first=Wendy|author-link=Wendy Doniger|title=Śiva, the erotic ascetic|year=1973|publisher=Oxford University Press US|pages=84–89|chapter = The Vedic Antecedents }}</ref> Doniger gives several reasons for her hypothesis. Both are associated with mountains, rivers, male fertility, fierceness, fearlessness, warfare, the transgression of established mores, the [[Om|Aum]] sound, the Supreme Self. In the Rig Veda the term ''{{transliteration|sa|ISO|śiva}}'' is used to refer to Indra. (2.20.3,{{refn|group=note|For text of RV 2.20.3a as {{lang|sa|स नो युवेन्द्रो जोहूत्रः सखा शिवो नरामस्तु पाता ।}} and translation as "May that young adorable ''Indra'', ever be the friend, the benefactor, and protector of us, his worshipper".{{Sfn|Arya|Joshi |2001|p=48, volume 2}}}} 6.45.17,<ref>For text of RV 6.45.17 as {{lang|sa|यो गृणतामिदासिथापिरूती शिवः सखा । स त्वं न इन्द्र मृलय ॥ }} and translation as "''Indra'', who has ever been the friend of those who praise you, and the insurer of their happiness by your protection, grant us felicity" see: {{harvnb|Arya|Joshi|2001|p=91}}, volume 3.</ref><ref>For translation of RV 6.45.17 as "Thou who hast been the singers' Friend, a Friend auspicious with thine aid, As such, O Indra, favour us" see: {{Harvnb|Griffith|1973|p=310}}.</ref> and 8.93.3.<ref>For text of RV 8.93.3 as {{lang|sa|स न इन्द्रः सिवः सखाश्चावद् गोमद्यवमत् । उरूधारेव दोहते ॥}} and translation as "May ''Indra'', our auspicious friend, milk for us, like a richly-streaming (cow), wealth of horses, kine, and barley" see: {{harvnb|Arya|Joshi|2001|p=48}}, volume 2.</ref>) Indra, like Shiva, is likened to a bull.<ref>For the bull parallel between Indra and Rudra see: {{harvnb|Chakravarti|1986|p=89}}.</ref><ref>RV 7.19.</ref> In the Rig Veda, Rudra is the father of the [[Maruts]], but he is never associated with their warlike exploits as is Indra.<ref>For the lack of warlike connections and difference between Indra and Rudra, see: {{harvnb|Chakravarti|1986|p=8}}.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Statère d'electrum du royaume de Kouchan à l'effigie de Vasou Deva I.jpg|upright|thumb|220px|Coin of the [[Kushan Empire]] (1st-century BCE to 2nd-century CE). The right image has been interpreted as Shiva with trident and bull.<ref>Hans Loeschner (2012), Victor Mair (Editor), [http://www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp227_kanishka_stupa_casket.pdf The Stūpa of the Kushan Emperor Kanishka the Great Sino-Platonic Papers], No. 227, pages 11, 19</ref>]] |

|||

According to [[Wendy Doniger]], the Puranic Shiva is a continuation of the Vedic Indra.<ref>{{cite book|last= Doniger|first=Wendy|authorlink=Wendy Doniger|title=Śiva, the erotic ascetic|year=1973|publisher=Oxford University Press US|pages=84–9|chapter = The Vedic Antecedents }}</ref> Doniger gives several reasons for her hypothesis. Both are associated with mountains, rivers, male fertility, fierceness, fearlessness, warfare, transgression of established mores, the [[Om|Aum]] sound, the Supreme Self. In the Rig Veda the term ''{{IAST|śiva}}'' is used to refer to Indra. (2.20.3,<ref>For text of RV 2.20.3a as {{lang|sa|स नो युवेन्द्रो जोहूत्रः सखा शिवो नरामस्तु पाता ।}} and translation as "May that young adorable ''Indra'', ever be the friend, the benefactor, and protector of us, his worshipper" see: Arya & Joshi (2001), p. 48, volume 2.</ref> 6.45.17,<ref>For text of RV 6.45.17 as {{lang|sa|यो गृणतामिदासिथापिरूती शिवः सखा । स त्वं न इन्द्र मृलय ॥ }} and translation as "''Indra'', who has ever been the friend of those who praise you, and the insurer of their happiness by your protection, grant us felicity" see: Arya & Joshi (2001), p. 91, volume 3.</ref><ref>For translation of RV 6.45.17 as "Thou who hast been the singers' Friend, a Friend auspicious with thine aid, As such, O Indra, favour us" see: {{Harvnb|Griffith|1973|p=310}}.</ref> and 8.93.3.<ref>For text of RV 8.93.3 as {{lang|sa|स न इन्द्रः सिवः सखाश्चावद् गोमद्यवमत् । उरूधारेव दोहते ॥}} and translation as "May ''Indra'', our auspicious friend, milk for us, like a richly-streaming (cow), wealth of horses, kine, and barley" see: Arya & Joshi (2001), p. 48, volume 2.</ref>) Indra, like Shiva, is likened to a bull.<ref>For the bull parallel between Indra and Rudra see: Chakravarti, p. 89.</ref><ref>RV 7.19.</ref> In the Rig Veda, Rudra is the father of the [[Maruts]], but he is never associated with their warlike exploits as is Indra.<ref>For the lack of warlike connections and difference between Indra and Rudra, see: Chakravarti, p. 8.</ref> |

|||

Indra himself may have been adopted by the Vedic Aryans from the [[Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex|Bactria–Margiana Culture]].{{sfn|Beckwith|2009|p=32}}{{sfn|Anthony|2007|pp=454–455}} According to Anthony, |

|||

The Vedic beliefs and practices of the pre-classical era were closely related to the hypothesised [[Proto-Indo-European religion]],<ref name="Woodard2006">{{cite book|author=Roger D. Woodard|title=Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EB4fB0inNYEC&pg=FA242|date=18 August 2006|publisher=University of Illinois Press|isbn=978-0-252-09295-4|pages=242–}}</ref> and the pre-Islamic Indo-Iranian religion.{{sfn|Beckwith|2009|p=32}} The earliest iconic artworks of Shiva may be from Gandhara and northwest parts of ancient India. There is some uncertainty as the artwork that has survived is damaged and they show some overlap with meditative Buddha-related artwork, but the presence of Shiva's trident and phallic symbolism in this art suggests it was likely Shiva.<ref>{{cite book|author=T. Richard Blurton|title=Hindu Art|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xJ-lzU_nj_MC&pg=PA84|year=1993|publisher=Harvard University Press|isbn=978-0-674-39189-5|pages=84, 103}}</ref> [[Numismatics]] research suggests that numerous coins of the ancient Kushan Empire that have survived, were images of a god who is probably Shiva.<ref>{{cite book|author=T. Richard Blurton|title=Hindu Art|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xJ-lzU_nj_MC&pg=PA84|year=1993|publisher=Harvard University Press|isbn=978-0-674-39189-5|page=84}}</ref> The Shiva in Kushan coins is referred to as Oesho of unclear etymology and origins, but the simultaneous presence of Indra and Shiva in the Kushan era artwork suggest that they were revered deities by the start of the Kushan Empire.<ref>{{cite book|author=Pratapaditya Pal|title=Indian Sculpture: Circa 500 B.C.-A.D. 700|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=clUmKaWRFTkC |year=1986|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=978-0-520-05991-7|pages=75–80}}</ref><ref name= Sivaramamurti41>{{cite book|author=C. Sivaramamurti|title=Satarudriya: Vibhuti Or Shiva's Iconography|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rOrilkdu-_MC |year=2004|publisher=Abhinav Publications|isbn=978-81-7017-038-9|pages=41, 59}}</ref> |

|||

{{blockquote|Many of the qualities of Indo-Iranian god of might/victory, [[Verethraghna]], were transferred to the adopted god Indra, who became the central deity of the developing Old Indic culture. Indra was the subject of 250 hymns, a quarter of the ''Rig Veda''. He was associated more than any other deity with ''Soma'', a stimulant drug (perhaps derived from ''Ephedra'') probably borrowed from the BMAC religion. His rise to prominence was a peculiar trait of the Old Indic speakers.{{sfn|Anthony|2007|p=454}}}} |

|||

The texts and artwork of [[Jainism]] show Indra as a dancer, although not identical |

The texts and artwork of [[Jainism]] show Indra as a dancer, although not identical generally resembling the dancing Shiva artwork found in Hinduism, particularly in their respective mudras.{{sfn|Owen|2012|pp=25–29}} For example, in the Jain caves at [[Ellora Caves|Ellora]], extensive carvings show dancing Indra next to the images of [[Tirthankara]]s in a manner similar to Shiva Nataraja. The similarities in the dance iconography suggests that there may be a link between ancient Indra and Shiva.{{sfnm|Sivaramamurti|2004|1pp=41, 59|Owen|2012|2pp=25–29}} |

||

=== |

=== Development === |

||

A few texts such as ''[[Atharvashiras Upanishad]]'' mention [[Rudra]], and assert all gods are Rudra, everyone and everything is Rudra, and Rudra is the principle found in all things, their highest goal, the innermost essence of all reality that is visible or invisible.{{Sfn|Deussen|1997|p=769}} The ''[[Kaivalya Upanishad]]'' similarly, states [[Paul Deussen]] – a German Indologist and professor of philosophy, describes the self-realized man as who "feels himself only as the one divine essence that lives in all", who feels identity of his and everyone's consciousness with Shiva (highest Atman), who has found this highest Atman within, in the depths of his heart.{{sfnm|Deussen|1997|1pp=792–793|Radhakrishnan|1953|2p=929}} |

|||

Rudra's evolution from a minor Vedic deity to a supreme being is first evidenced in the ''[[Shvetashvatara Upanishad]]'' (400–200 BC), according to Gavin Flood.{{sfn|Flood|2003|pp=204–205}}{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=86}} Prior to it, the Upanishadic literature is [[Advaita|monistic]], and the ''Shvetashvatara'' text presents the earliest seeds of theistic devotion to Rudra-Shiva.{{sfn|Flood|2003|pp=204–205}} Here Rudra-Shiva is identified as the creator of the cosmos and [[Saṃsāra|liberator of souls]] from the birth-rebirth cycle. The period of 200 BC to 100 AD also marks the beginning of the Shaiva tradition focused on the worship of Shiva as evidenced in other literature of this period.{{sfn|Flood|2003|pp=204–205}} Shaiva devotees and ascetics are mentioned in [[Patanjali]]'s ''[[Mahābhāṣya]]'' (2nd-century BC) and in the ''[[Mahabharata]]''.{{sfn|Flood|2003|p=205, for date of Mahabhasya see: Peter M. Scharf (1996), The Denotation of Generic Terms in Ancient Indian Philosophy: Grammar, Nyāya, and Mīmāṃsā, American Philosophical Society, ISBN 978-0-87169-863-6, page 1 with footnote 2}} Other scholars such as Robert Hume and Doris Srinivasan state that the ''Shvetashvatara Upanishad'' presents pluralism, [[pantheism]], or [[henotheism]], rather than being a text just on Shiva theism.<ref>Robert Hume, [https://archive.org/stream/thirteenprincipa028442mbp#page/n419/mode/2up Shvetashvatara Upanishad], The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 399, 403</ref><ref>M. Hiriyanna (2000), The Essentials of Indian Philosophy, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120813304, pages 32–36</ref><ref>[a] A Kunst, Some notes on the interpretation of the Ṥvetāṥvatara Upaniṣad, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol. 31, Issue 02, June 1968, pages 309–314; {{doi|10.1017/S0041977X00146531}};<br>[b] Doris Srinivasan (1997), Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes, Brill, ISBN 978-9004107588, pages 96–97 and Chapter 9</ref> |

|||

Rudra's evolution from a minor Vedic deity to a supreme being is first evidenced in the ''[[Shvetashvatara Upanishad]]'' (400–200 BCE), according to Gavin Flood, presenting the earliest seeds of theistic devotion to Rudra-Shiva.{{sfn|Flood|2003|pp=204–205}} Here Rudra-Shiva is identified as the creator of the cosmos and [[Saṃsāra|liberator of Selfs]] from the birth-rebirth cycle. The Svetasvatara Upanishad set the tone for early Shaivite thought, especially in chapter 3 verse 2 where Shiva is equated with Brahman: "Rudra is truly one; for the knowers of Brahman do not admit the existence of a second".<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.esamskriti.com/e/Spirituality/Upanishads-Commentary/Svetasvatara-Upanishad-~-Chap-3-The-Highest-Reality-1.aspx | title=Svetasvatara Upanishad - Chap 3 the Highest Reality | access-date=2 September 2022 | archive-date=1 October 2022 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221001023958/https://www.esamskriti.com/e/Spirituality/Upanishads-Commentary/Svetasvatara-Upanishad-~-Chap-3-The-Highest-Reality-1.aspx | url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news | url=https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/edit-page/speaking-tree-the-trika-tradition-of-kashmir-shaivism/articleshow/4822600.cms | title=Speaking Tree: The Trika Tradition of Kashmir Shaivism | website=[[The Times of India]] | date=27 July 2009 | access-date=2 September 2022 | archive-date=2 September 2022 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220902090554/https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/edit-page/speaking-tree-the-trika-tradition-of-kashmir-shaivism/articleshow/4822600.cms | url-status=live }}</ref> The period of 200 BC to 100 AD also marks the beginning of the Shaiva tradition focused on the worship of Shiva as evidenced in other literature of this period.{{sfn|Flood|2003|pp=204–205}} Other scholars such as Robert Hume and Doris Srinivasan state that the ''Shvetashvatara Upanishad'' presents pluralism, [[pantheism]], or [[henotheism]], rather than being a text just on Shiva theism.{{sfnm|Hume|1921|1pp=399, 403|Hiriyanna|2000|2pp=32–36|3a1=Kunst|3y=1968|Srinivasan|1997|4loc=pp. 96–97 and Chapter 9}} |

|||

{{Quote box |

{{Quote box |

||

| Line 114: | Line 135: | ||

|align = right |

|align = right |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The [[Shaiva Upanishads]] are a group of 14 minor Upanishads of Hinduism variously dated from the last centuries of the 1st millennium BCE through the 17th century.{{Sfn|Deussen| 1997|p=556, 769 footnote 1}} These extol Shiva as the metaphysical unchanging reality [[Brahman]] and the [[Atman (Hinduism)|Atman]] (soul, self),{{Sfn|Deussen|1997|p=769}} and include sections about rites and symbolisms related to Shiva.{{Sfn|Klostermaier|1984|pp=134, 371}} |

|||

Shaiva devotees and ascetics are mentioned in [[Patanjali]]'s ''[[Mahābhāṣya]]'' (2nd-century BCE) and in the ''[[Mahabharata]]''.<ref>{{harvnb|Flood|2003|p=205}} For date of Mahabhasya see: {{harvnb|Scharf|1996|loc=page 1 with footnote}}.</ref> |

|||

A few texts such as ''[[Atharvashiras Upanishad]]'' mention [[Rudra]], and assert all gods are Rudra, everyone and everything is Rudra, and Rudra is the principle found in all things, their highest goal, the innermost essence of all reality that is visible or invisible.{{Sfn|Deussen|1997|p=769}} The ''Kaivalya Upanishad'' similarly, states [[Paul Deussen]] – a German Indologist and professor of Philosophy, describes the self-realized man as who "feels himself only as the one divine essence that lives in all", who feels identity of his and everyone's consciousness with Shiva (highest Atman), who has found this highest Atman within, in the depths of his heart.{{Sfn|Deussen|1997|pp=792–793}}{{Sfn|Radhakrishnan|1953|p=929}} |

|||

The earliest iconic artworks of Shiva may be from Gandhara and northwest parts of ancient India. There is some uncertainty as the artwork that has survived is damaged and they show some overlap with meditative Buddha-related artwork, but the presence of Shiva's trident and phallic symbolism{{refn|group=note|name="ilph_rep_l"}} in this art suggests it was likely Shiva.{{sfn|Blurton|1993|pp=84, 103}} [[Numismatics]] research suggests that numerous coins of the ancient [[Kushan Empire]] (30–375 CE) that have survived, were images of a god who is probably Shiva.{{sfn|Blurton|1993|p=84}} The Shiva in Kushan coins is referred to as Oesho of unclear etymology and origins, but the simultaneous presence of Indra and Shiva in the Kushan era artwork suggest that they were revered deities by the start of the Kushan Empire.<ref>{{cite book|author=Pratapaditya Pal|title=Indian Sculpture: Circa 500 B.C.–A.D. 700|url=https://archive.org/details/indiansculpturec00losa |url-access=registration|year=1986|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=978-0520-059917|pages=[https://archive.org/details/indiansculpturec00losa/page/75 75]–80}}</ref>{{sfn|Sivaramamurti|2004|pp=41, 59}} |

|||

The [[Puranas#Classification|Shaiva Purana]]s, particularly the [[Shiva Purana]] and the [[Linga Purana]], present the various aspects of Shiva, mythologies, cosmology and pilgrimage (''[[Tirtha (Hinduism)|Tirtha]]'') associated with him.{{sfn|Flood|2003|pp=205–206}}{{Sfn|Rocher|1986|pp=187–188, 222–228}} The Shiva-related [[Tantra]] literature, composed between the 8th and 11th centuries, are regarded in devotional dualistic Shaivism as [[Sruti]]. Dualistic [[Āgama (Hinduism)#Philosophy|Shaiva Agamas]] which consider soul within each living being and Shiva as two separate realities (dualism, ''dvaita''), are the foundational texts for [[Shaiva Siddhanta]].{{sfn|Flood|2003|pp=208–212}} Other Shaiva Agamas teach that these are one reality (monism, ''advaita''), and that Shiva is the soul, the perfection and truth within each living being.<ref>DS Sharma (1990), The Philosophy of Sadhana, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791403471, pages 9–14</ref><ref name=richdavis167>Richard Davis (2014), Ritual in an Oscillating Universe: Worshipping Siva in Medieval India, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691603087, page 167 note 21, '''Quote (page 13):''' "Some agamas argue a monist metaphysics, while others are decidedly dualist. Some claim ritual is the most efficacious means of religious attainment, while others assert that knowledge is more important".</ref> In Shiva related sub-traditions, there are ten dualistic Agama texts, eighteen qualified monism-cum-dualism Agama texts and sixty four monism Agama texts.<ref>Mark Dyczkowski (1989), The Canon of the Śaivāgama, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120805958, pages 43–44</ref><ref>JS Vasugupta (2012), Śiva Sūtras, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120804074, pages 252, 259</ref>{{Sfn|Flood|1996|pp=162–169}} |

|||

The [[Shaiva Upanishads]] are a group of 14 minor Upanishads of Hinduism variously dated from the last centuries of the 1st millennium BCE through the 17th century.{{Sfn|Deussen| 1997|p=556, 769 footnote 1}} These extol Shiva as the metaphysical unchanging reality [[Brahman]] and the [[Atman (Hinduism)|Atman]] (Self),{{Sfn|Deussen|1997|p=769}} and include sections about rites and symbolisms related to Shiva.{{Sfn|Klostermaier|1984|pp=134, 371}} |

|||

Shiva-related literature developed extensively across India in the 1st millennium CE and through the 13th century, particularly in Kashmir and Tamil Shaiva traditions.{{Sfn|Flood|1996|pp=162–169}} The monist Shiva literature posit absolute oneness, that is Shiva is within every man and woman, Shiva is within every living being, Shiva is present everywhere in the world including all non-living being, and there is no spiritual difference between life, matter, man and Shiva.<ref>Ganesh Tagare (2002), The Pratyabhijñā Philosophy, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120818927, pages 16–19</ref> The various dualistic and monist Shiva-related ideas were welcomed in medieval southeast Asia, inspiring numerous Shiva-related temples, artwork and texts in Indonesia, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Thailand and Malaysia, with syncretic integration of local pre-existing theologies.{{sfn|Flood|2003|pp=208–212}}<ref>{{cite book|author=Jan Gonda|title=Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 3 Southeast Asia, Religions |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=X7YfAAAAIAAJ |year=1975 |authorlink=Jan Gonda |publisher=BRILL Academic|isbn=90-04-04330-6|pages=3–20, 35–36, 49–51}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Upendra Thakur|title=Some Aspects of Asian History and Culture|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=m42TldA_OvAC |year=1986|publisher=Abhinav Publications|isbn=978-81-7017-207-9|pages=83–94}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Puranas#Classification|Shaiva Puranas]], particularly the [[Shiva Purana]] and the [[Linga Purana]], present the various aspects of Shiva, mythologies, cosmology and pilgrimage (''[[Tirtha (Hinduism)|Tirtha]]'') associated with him.{{sfnm|Flood|2003|1pp=205–206|Rocher|1986|2pp=187–188, 222–228}} The Shiva-related [[Tantra]] literature, composed between the 8th and 11th centuries, are regarded in devotional dualistic Shaivism as [[Sruti]]. Dualistic [[Āgama (Hinduism)#Philosophy|Shaiva Agamas]] which consider Self within each living being and Shiva as two separate realities (dualism, ''dvaita''), are the foundational texts for [[Shaiva Siddhanta]].{{sfn|Flood|2003|pp=208–212}} Other Shaiva Agamas teach that these are one reality (monism, ''advaita''), and that Shiva is the Self, the perfection and truth within each living being.<ref>{{harvnb|Sharma|1990|pp=9–14}}; {{harvnb|Davis|1992|loc=p. 167 note 21}}, ''Quote (page 13):'' "Some agamas argue a monist metaphysics, while others are decidedly dualist. Some claim ritual is the most efficacious means of religious attainment, while others assert that knowledge is more important".</ref> In Shiva related sub-traditions, there are ten dualistic Agama texts, eighteen qualified monism-cum-dualism Agama texts and sixty-four monism Agama texts.<ref>Mark Dyczkowski (1989), The Canon of the Śaivāgama, Motilal Banarsidass, {{ISBN|978-8120805958}}, pl. 43–44</ref><ref>JS Vasugupta (2012), Śiva Sūtras, Motilal Banarsidass, {{ISBN|978-8120804074}}, pp. 252, 259</ref>{{Sfn|Flood|1996|pp=162–169}} |

|||

===Assimilation of traditions=== |

|||

{{See also|Hinduism#Roots of Hinduism|l1=Roots of Hinduism}} |

|||

Shiva-related literature developed extensively across India in the 1st millennium CE and through the 13th century, particularly in Kashmir and Tamil Shaiva traditions.{{Sfn|Flood|1996|pp=162–169}} Shaivism gained immense popularity in [[Tamilakam]] as early as the 7th century CE, with poets such as [[Appar]] and [[Sambandar]] composing rich poetry that is replete with present features associated with the deity, such as his [[tandava]] dance, the mulavam (dumru), the aspect of holding fire, and restraining the proud flow of the Ganga upon his braid.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Somasundaram |first1=Ottilingam |last2=Murthy |first2=Tejus |date=2017 |title=Siva - The Mad Lord: A Puranic perspective |journal=Indian Journal of Psychiatry |volume=59 |issue=1 |pages=119–122 |doi=10.4103/0019-5545.204441 |issn=0019-5545 |pmc=5418997 |pmid=28529371 |doi-access=free }}</ref> The monist Shiva literature posit absolute oneness, that is Shiva is within every man and woman, Shiva is within every living being, Shiva is present everywhere in the world including all non-living being, and there is no spiritual difference between life, matter, man and Shiva.{{sfn|Tagare|2002|pp=16–19}} The various dualistic and monist Shiva-related ideas were welcomed in medieval southeast Asia, inspiring numerous Shiva-related temples, artwork and texts in Indonesia, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Thailand and Malaysia, with syncretic integration of local pre-existing theologies.{{sfnm|Flood|2003|1pp=208–212|Gonda|1975|2pp=3–20, 35–36, 49–51|Thakur|1986|3pp=83–94}} |

|||

The figure of Shiva as we know him today may be an amalgamation of various older deities into a single figure.<ref name="Keayxxvii"/><ref>Phyllis Granoff (2003), [http://www.jstor.org/stable/41913237 Mahakala's Journey: from Gana to God], Rivista degli studi orientali, Vol. 77, Fasc. 1/4 (2003), pages 95–114</ref> How the persona of Shiva converged as a composite deity is not understood, a challenge to trace and has attracted much speculation.<ref>For Shiva as a composite deity whose history is not well documented, see: Keay, p. 147.</ref> According to Vijay Nath, for example: |

|||

{{quote|Vishnu and Siva [...] began to absorb countless local cults and deities within their folds. The latter were either taken to represent the multiple facets of the same god or else were supposed to denote different forms and appellations by which the god came to be known and worshipped. [...] Siva became identified with countless local cults by the sheer suffixing of ''Isa'' or ''Isvara'' to the name of the local deity, e.g., Bhutesvara, Hatakesvara, Chandesvara."{{sfn|Nath|2001|p=31}}}} |

|||

== Position within Hinduism == |

|||

An example of assimilation took place in [[Maharashtra]], where a regional deity named [[Khandoba]] is a patron deity of farming and herding [[caste]]s.<ref name="Courtright, p. 205">Courtright, p. 205.</ref> The foremost center of worship of Khandoba in Maharashtra is in [[Jejuri]].<ref>For Jejuri as the foremost center of worship see: Mate, p. 162.</ref> Khandoba has been assimilated as a form of Shiva himself,<ref>''Biroba, Mhaskoba und Khandoba: Ursprung, Geschichte und Umwelt von pastoralen Gottheiten in Maharastra'', Wiesbaden 1976 (German with English Synopsis) pp. 180–98, "Khandoba is a local deity in Maharashtra and been Sanskritised as an incarnation of Shiva."</ref> in which case he is worshipped in the form of a lingam.<ref name="Courtright, p. 205"/><ref>For worship of Khandoba in the form of a lingam and possible identification with Shiva based on that, see: Mate, p. 176.</ref> Khandoba's varied associations also include an identification with [[Surya]]<ref name="Courtright, p. 205"/> and [[Karttikeya]].<ref>For use of the name Khandoba as a name for Karttikeya in Maharashtra, see: Gupta, ''Preface'', and p. 40.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Lingothbhavar.jpg|thumb|[[Lingodbhava]] is a Shaiva sectarian icon where Shiva is depicted rising from the [[Lingam]] (an infinite fiery pillar) that narrates how Shiva is the foremost of the [[Trimurt]]i; [[Brahma]] on the left and [[Vishnu]] on the right are depicted bowing to Shiva in the centre.]] |

|||

==Position within Hinduism== |

|||

[[File:Lingothbhavar.jpg|thumb|[[Lingodbhava]] is a Shaiva sectarian icon where Shiva is depicted rising from the [[Lingam]] (an infinite fiery pillar) that narrates how Shiva is the foremost of the Trimurti; Brahma and Vishnu are depicted bowing to Lingodbhava Shiva in the centre.]] |

|||

=== Shaivism === |

=== Shaivism === |

||

{{Main |

{{Main|Shaivism}} |

||

Shaivism is one of the four major sects of [[Hinduism]], the others being [[Vaishnavism]], [[Shaktism]] and the [[Smarta Tradition]]. Followers of Shaivism, called "Shaivas", revere Shiva as the Supreme Being. Shaivas believe that Shiva is All and in all, the creator, preserver, destroyer, revealer and concealer of all that is.{{Sfn|Sharma|2000|p=65}}{{Sfn|Issitt|Main|2014|pp=147, 168}} He is not only the creator in Shaivism, but he is also the creation that results from him, he is everything and everywhere. Shiva is the primal Self, the pure consciousness and [[Brahman|Absolute Reality]] in the Shaiva traditions.{{Sfn|Sharma|2000|p=65}} Shiva is also part of 'Om' (ॐ) as a 'U' (उ).<ref>{{Cite web |title=Devi bhagwat Purana Skandh 5 Chapter 1 Verse 22-23 |url=https://archive.org/details/devi-bhagavata-with-hindi-translation/Devi%20Bhagavata%20with%20Hindi%20Translation%20Vol%201%20%28Gitapress%29%202010/page/n540/mode/1up?view=theater |url-status=live |archive-url=https://archive.org/details/devi-bhagavata-with-hindi-translation/Devi%20Bhagavata%20with%20Hindi%20Translation%20Vol%201%20%28Gitapress%29%202010/page/n540/mode/1up?view=theater}}</ref> |

|||

{{Saivism}} |

|||