Noam Chomsky: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 764905667 by JFG (talk) Aviva Chomsky |

GiantSnowman (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|American linguist and activist (born 1928)}} |

|||

{{Redirect|Chomsky}} |

{{Redirect|Chomsky}} |

||

{{ |

{{Good article}} |

||

{{pp-move}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=October 2012}} |

|||

{{pp |

{{pp|small=yes}} |

||

{{Use mdy dates|date=December 2024}} |

|||

{{Infobox scientist |

|||

{{Use American English|date=July 2019}} |

|||

|name = Noam Chomsky |

|||

{{Infobox academic |

|||

|image = Noam Chomsky portrait 2015.jpg |

|||

| name = Noam Chomsky |

|||

|image_size = |

|||

| |

| image = Noam Chomsky portrait 2017 retouched.jpg |

||

| |

| alt = A photograph of Noam Chomsky |

||

| caption = Chomsky in 2017 |

|||

|birth_date = {{Birth date and age|mf=yes|1928|12|7}} |

|||

| birth_name = Avram Noam Chomsky |

|||

|birth_place = [[Philadelphia]], [[Pennsylvania]], U.S. |

|||

| birth_date = {{Birth date and age|1928|12|7}} |

|||

|field = [[Linguistics]], [[analytic philosophy]], [[cognitive science]], [[political criticism]] |

|||

| birth_place = [[Philadelphia]], Pennsylvania, U.S. |

|||

|work_institutions = {{Plainlist| |

|||

| father = [[William Chomsky]] |

|||

*[[MIT]] <small>(1955–present)</small> |

|||

| thesis_title = Transformational Analysis |

|||

*[[Institute for Advanced Study]] <small>(1958–1959)</small> |

|||

| thesis_url = https://www.proquest.com/docview/89172813 |

|||

| thesis_year = 1955 |

|||

| doctoral_advisor = [[Zellig Harris]]{{sfn|Partee|2015|p=328}} |

|||

| doctoral_students = {{collapsible list| title = {{nbsp}} | [[Gulsat Aygen|Gülşat Aygen]], [[Mark Baker (linguist)|Mark Baker]], [[Jonathan Bobaljik]], [[Joan Bresnan]], [[Peter Culicover]], [[Ray C. Dougherty]], [[Janet Dean Fodor]], [[John Goldsmith (linguist)|John Goldsmith]], [[C.-T. James Huang]], [[Sabine Iatridou]], [[Ray Jackendoff]], [[Edward Klima]], [[Jan Koster]], [[Jaklin Kornfilt]], [[S.-Y. Kuroda]], [[Howard Lasnik]], [[Robert Lees (linguist)|Robert Lees]], [[Alec Marantz]], [[Diane Massam]], [[James D. McCawley]], [[Jacques Mehler]], [[Andrea Moro]], [[Barbara Partee]], [[David M. Perlmutter|David Perlmutter]], [[David Pesetsky]], [[Tanya Reinhart]], [[John R. Ross]], [[Ivan Sag]], [[Edwin S. Williams]]}} |

|||

| known_for = |

|||

| influences = {{collapsible list| title = {{nbsp}} |

|||

| <!-- LINGUISTIC & PHILOSOPHICAL INFLUENCES --> |

|||

<!-- per the infobox documentation, each name must be explained in the article's prose and cite a third-party source; those that are not mentioned in the main text will be removed --> |

|||

{{collapsible list| title = Academic | [[J. L. Austin]], [[William Chomsky]], [[C. West Churchman]], [[René Descartes]], [[Galileo]],{{sfn|Chomsky|1991|p=50}} [[Nelson Goodman]], [[Morris Halle]], [[Zellig Harris]], [[Wilhelm von Humboldt]], [[David Hume]],{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|pp=44–45}} [[Roman Jakobson]], [[Immanuel Kant]],{{sfn|Slife|1993|p=115}} [[George Armitage Miller]], [[Pāṇini]], [[Hilary Putnam]],{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=58}} [[W. V. O. Quine]], [[Bertrand Russell]], [[Ferdinand de Saussure]], [[Marcel-Paul Schützenberger]], [[Alan Turing]],{{sfn|Chomsky|1991|p=50}} [[Ludwig Wittgenstein]]{{sfn|Antony|Hornstein|2003|p=295}} |

|||

}} |

|||

<!-- SOCIAL & POLITICAL INFLUENCES --> |

|||

<!-- per the infobox documentation, each name must be explained in the article's prose and cite a third-party source; those that are not mentioned in the main text will be removed --> |

|||

{{collapsible list| title = Political | [[Mikhail Bakunin]], [[Alex Carey (writer)|Alex Carey]], [[William Chomsky]], [[John Dewey]],{{sfn|Chomsky|2016}} [[Zellig Harris]], [[Wilhelm von Humboldt]],{{sfn|Harbord|1994|p=487}} [[David Hume]],{{sfn|Barsky|2007|p=107}} [[Thomas Jefferson]], [[Karl Korsch]], [[Peter Kropotkin]],{{sfn|Barsky|2007|p=107}} [[Karl Liebknecht]], [[Rosa Luxemburg]], [[John Locke]], [[Dwight Macdonald]], [[Paul Mattick]],{{sfn|Barsky|2007|p=107}} [[John Stuart Mill]], [[George Orwell]], [[Anton Pannekoek]], [[Pierre-Joseph Proudhon]],{{sfn|Smith|2004|p=185}} [[Rudolf Rocker]], [[Jean-Jacques Rousseau]],{{sfn|Barsky|2007|p=107}} [[Bertrand Russell]], [[Diego Abad de Santillán]], [[Adam Smith]]{{sfn|Barsky|2007|p=107}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

| influenced = {{collapsible list| title = {{nbsp}} |

|||

|alma_mater = {{Plainlist| |

|||

| <!-- ACADEMIC INFLUENCEES --> |

|||

*[[University of Pennsylvania]] |

|||

<!-- per the infobox documentation, each name must be explained in the article's prose and cite a third-party source; those that are not mentioned in the main text will be removed --> |

|||

*[[Harvard Society of Fellows]]}} |

|||

{{collapsible list| title = In academia | [[John Backus]], [[Derek Bickerton]], [[Julian C. Boyd]], [[Daniel Dennett]],{{sfn|Amid the Philosophers}} [[Daniel Everett]], [[Jerry Fodor]], [[Gilbert Harman]], [[Marc Hauser]], [[Norbert Hornstein]], [[Niels Kaj Jerne]], [[Donald Knuth]], [[Georges J. F. Köhler]], [[Peter Ludlow]], [[Colin McGinn]],{{sfn|Persson|LaFollette|2013}} [[César Milstein]], [[Steven Pinker]],{{sfn|Prickett|2002|p=234}} [[John Searle]],{{sfn|Searle|1972}} [[Neil Smith (linguist)|Neil Smith]], [[Crispin Wright]]{{sfn|Amid the Philosophers}} |

|||

|thesis_title = Transformational Analysis |

|||

}} |

|||

|thesis_url = http://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI0013380/ |

|||

|thesis_year = 1955 |

|||

<!-- SOCIAL AND POLITICAL INFLUENCEES --> |

|||

|doctoral_advisor = |

|||

<!-- per the infobox documentation, each name must be explained in the article's prose and cite a third-party source; those that are not mentioned in the main text will be removed --> |

|||

|doctoral_students = {{collapsible list| title = {{nbsp}} | [[Mark Baker (linguist)|Mark Baker]], [[Ray C. Dougherty]], [[C.-T. James Huang]], [[Ray Jackendoff]], [[George Lakoff]], [[Howard Lasnik]], [[Robert Lees]], [[James McCawley]], [[Barbara Partee]], [[John R. Ross]], and many others }} |

|||

{{collapsible list| title = In politics | [[Michael Albert]], [[Julian Assange]], [[Bono]],{{sfn|Adams|2003}} [[Jean Bricmont]], [[Hugo Chávez]], [[Zack de la Rocha]], [[Clinton Fernandes]], [[Norman Finkelstein]], [[Robert Fisk]], [[Amy Goodman]], [[Stephen Jay Gould]],{{sfn|Gould|1981}} [[Glenn Greenwald]], [[Christopher Hitchens]],{{sfn|Adams|2003}} [[Naomi Klein]],{{sfn|Adams|2003}} [[Kyle Kulinski]],<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://jacobinmag.com/2020/03/kyle-kulinski-bernie-bros-secular-talk-joe-rogan-youtube|title=Kyle Kulinski Speaks, the Bernie Bros Listen|access-date=February 9, 2022|archive-date=March 5, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200305204651/https://jacobinmag.com/2020/03/kyle-kulinski-bernie-bros-secular-talk-joe-rogan-youtube|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

|known_for = {{collapsible list| title = {{nbsp}} | {{Plainlist| |

|||

[[Michael Moore]],{{sfn|Adams|2003}} [[John Nichols (journalist)|John Nichols]], [[Ann Nocenti]],{{sfn|Keller|2007}} [[John Pilger]], [[Harold Pinter]],{{sfn|Adams|2003}} [[Arundhati Roy]], [[Edward Said]], [[Aaron Swartz]]{{sfn|Swartz|2006}} |

|||

* "[[Colorless green ideas sleep furiously]]" |

|||

}} |

|||

* [[Axiom of categoricity]] |

|||

* [[Bought priesthood]] |

|||

* [[Cartesian linguistics]] |

|||

* [[Chomsky Normal Form]] |

|||

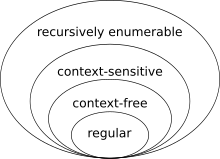

* [[Chomsky hierarchy]] |

|||

* [[Chomsky–Schützenberger theorem (disambiguation)|Chomsky–Schützenberger theorem]] |

|||

* [[Cognitive closure (philosophy)]] |

|||

* [[Context-free grammar]] |

|||

* [[Context-sensitive grammar]] |

|||

* [[Corporate media]] |

|||

* [[Deep structure and surface structure]] |

|||

* [[Deterministic context-free grammar]] |

|||

* [[Digital infinity]] |

|||

* [[E-Language]] |

|||

* [[Elite media]] |

|||

* [[Empty category principle]] |

|||

* [[Extended Projection Principle]] |

|||

* [[Formal democracy]] |

|||

* [[Formal grammar]] |

|||

* [[Generative grammar]] |

|||

* [[Government and binding]] |

|||

* [[I-Language]] |

|||

* [[Immediate constituent analysis]] |

|||

* [[Innateness hypothesis]] |

|||

* [[Intellectual responsibility]] |

|||

* [[Language acquisition device]] |

|||

* [[Levels of adequacy]] |

|||

* [[Linguistic competence]] |

|||

* [[Linguistic performance]] |

|||

* [[Logical Form (linguistics)]] |

|||

* [[M-command]] |

|||

* [[Markedness]] |

|||

* [[Media manipulation]] |

|||

* [[Mentalism (philosophy)]] |

|||

* [[Merge (linguistics)]] |

|||

* [[Minimalist program]] |

|||

* [[Non-configurational language]] |

|||

* [[Parasitic gap]] |

|||

* [[Phonology]] |

|||

* [[Phrase structure grammar]] |

|||

* [[Phrase structure rules]] |

|||

* [[Plato's Problem]] |

|||

* [[Poverty of the stimulus]] |

|||

* [[Principles and parameters]] |

|||

* [[Projection Principle]] |

|||

* [[Propaganda model]] |

|||

* [[Psychological nativism]] |

|||

* [[Recursion|Recursion in language]] |

|||

* [[Scansion]] |

|||

* [[Second-language acquisition]] |

|||

* [[Self-censorship]] |

|||

* [[Specified subject condition]] |

|||

* [[Speech community]] |

|||

* [[Statistical language acquisition]] |

|||

* [[Structure preservation principle]] |

|||

* [[Subjacency]] |

|||

* [[Symbol (formal)]] |

|||

* [[Tensed-S condition]] |

|||

* [[Terminal and nonterminal symbols]] |

|||

* [[Trace erasure principle]] |

|||

* [[Transformational grammar]] |

|||

* [[Transformational syntax]] |

|||

* [[Universal grammar]] |

|||

* [[X-bar theory]] |

|||

}} }} |

|||

|influences = {{collapsible list| title = {{nbsp}} | [[J. L. Austin]], [[Mikhail Bakunin]],<ref name="Taylor & Francis">{{cite book|title=Noam Chomsky: Critical Assessments, Volumes 2–3|year=1994|publisher=Taylor & Francis|isbn=978-0-415-10694-8|page=487|editor=Carlos Peregrín Otero}}</ref> [[Alex Carey]],<ref>{{cite book|last=Chomsky|first=Noam|title=Class Warfare: Interviews with David Barsamian|year=1996|publisher=Pluto Press|location=London|pages=28–29|quote=The real importance of Carey's work is that it's the first effort and until now the major effort to bring some of this to public attention. It's had a tremendous influence on the work I've done.}}</ref> [[C. West Churchman]], [[William Chomsky]], [[René Descartes]],<ref>{{cite book|title=Noam Chomsky: A Life of Dissent|year=1998|publisher=MIT Press|isbn=978-0-262-52255-7|page=106|author=Robert F. Barsky}}</ref> [[John Dewey]], [[Nelson Goodman]], [[Morris Halle]], [[Zellig Harris]], [[Hebrew literature]],<ref name="Noam Chomsky">{{cite web|author=Noam Chomsky |url=https://chomsky.info/reader01/ |title=Personal influences, by Noam Chomsky (Excerpted from The Chomsky Reader) |publisher=Chomsky.info |date= |accessdate=2013-05-29}}</ref> [[Wilhelm von Humboldt]],<ref name="Taylor & Francis" /> [[David Hume]],<ref>{{cite book|title=Noam Chomsky|year=2006|publisher=Reaktion Books|isbn=978-1-86189-269-0|pages=44–45|author=Wolfgang B. Sperlich}}</ref> [[Roman Jakobson]], [[Immanuel Kant]],<ref>{{cite book|title=Time and Psychological Explanation: The Spectacle of Spain's Tourist Boom and the Reinvention of Difference|year=1993|publisher=SUNY Press|isbn=978-0-7914-1469-9|page=115|author=Brent D. Slife}}</ref> [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/7865508/Noam-Chomsky-interview.html|title=Noam Chomsky interview|last=Farndale|first=Nigel|website=Telegraph.co.uk|access-date=2016-05-15}}</ref> [[Karl Korsch]], [[Peter Kropotkin]],<ref>{{cite web|title=Noam Chomsky Reading List|url=http://leftreferenceguide.wordpress.com/noam-chomsky-reading-list/|publisher=Left Reference Guide|accessdate=8 January 2014}}</ref> [[Karl Liebknecht]], [[John Locke]], [[Rosa Luxemburg]], [[Dwight Macdonald]],<ref>{{cite video |people=Noam Chomsky |date=September 22, 2011 |title=Noam Chomsky on the Responsibility of Intellectuals: Redux |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PK9W5DE7ZtQ |medium= |language= |trans_title= |publisher=Ideas Matter |location= |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130826012857/http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PK9W5DE7ZtQ|archivedate=2013-08-26|accessdate=October 16, 2011 |time=09:23 |id= |isbn= |oclc= |quote= |dead-url=yes |ref= }}</ref> [[Karl Marx]], [[John Stuart Mill]], [[George Armitage Miller]], [[George Orwell]], [[W. V. O. Quine]], [[Pāṇini]], [[Anton Pannekoek]], [[Jean Piaget]], [[Pierre-Joseph Proudhon]], [[Hilary Putnam]],{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=58}} [[David Ricardo]], [[Rudolf Rocker]], [[Bertrand Russell]], [[Russian literature]],<ref name="Noam Chomsky">{{cite web|author=Noam Chomsky |url=https://chomsky.info/reader01/ |title=Personal influences, by Noam Chomsky (Excerpted from The Chomsky Reader) |publisher=Chomsky.info |date= |accessdate=2013-05-29}}</ref> [[Diego Abad de Santillán]], [[Ferdinand de Saussure]], [[Marcel-Paul Schützenberger]], [[Adam Smith]], [[Leon Trotsky]], [[Alan Turing]], [[Ludwig Wittgenstein]] }} |

|||

|influenced = {{collapsible list| title = {{nbsp}} | [[Michael Albert]], [[Julian Assange]], [[John Backus]],<ref>{{cite web|title=John W. Backus (1924–2007)|url=http://betanews.com/2007/03/20/john-w-backus-1924-2007/|publisher=BetaNews, Inc.|author=Scott M. Fulton, III}}</ref> [[Derek Bickerton]], [[Bono]],<ref name="Adams">{{Cite web|url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2003/nov/30/highereducation.internationaleducationnews|title=Noam Chomsky: Thorn in America's side|last=Adams|first=Tim|date=2003-11-30|website=the Guardian|access-date=2016-05-08}}</ref> [[Julian C. Boyd]], [[Jean Bricmont]], [[Hugo Chávez]], [[Daniel Dennett]],<ref name="Chomsky Amid the Philosophers">{{cite web|title=Chomsky Amid the Philosophers|url=http://www.uea.ac.uk/~j108/chomsky.htm|publisher=University of East Anglia|accessdate=8 January 2014}}</ref> [[Daniel Everett]], [[Clinton Fernandes]], [[Norman Finkelstein]], [[Robert Fisk]], [[Jerry Fodor]], [[Amy Goodman]], [[Stephen Jay Gould]],<ref name="Gould_dep">Gould, S. J. (1981). [http://www.antievolution.org/projects/mclean/new_site/depos/pf_gould_dep.htm "Official Transcript for Gould's deposition in McLean v. Arkansas".] (Nov. 27).</ref> [[Glenn Greenwald]], [[Gilbert Harman]], [[Marc Hauser]], [[Christopher Hitchens]],<ref name= "Adams" /> [[Norbert Hornstein]], [[Niels Kaj Jerne]], [[Naomi Klein]],<ref name= "Adams" /> [[Donald Knuth]],<ref>{{cite book|last1=Knuth|first1=Donald E.|date=2003|title=Selected Papers on Computer Languages|url=|location=|publisher=|page=1|chapter=Preface: a mathematical theory of language in which I could use a computer programmer's intuition|isbn=1-57586-382-0| accessdate = }}</ref> [[Peter Ludlow]], [[Colin McGinn]],<ref>{{cite book|title=The Blackwell Guide to Ethical Theory|year=2013|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=978-1-118-51426-9|edition=2|editor=Hugh LaFollette, Ingmar Persson}}</ref> [[Michael Moore]],<ref name= "Adams" /> [[John Nichols (journalist)|John Nichols]], [[Ann Nocenti]],<ref name=SequentialTart>Keller, Katherine (November 2, 2007). [http://www.sequentialtart.com/article.php?id=737 "Writer, Creator, Journalist, and Uppity Woman: Ann Nocenti"]. ''Sequential Tart''.</ref> [[John Pilger]],<ref name= "Adams" /> [[Steven Pinker]],<ref>{{cite book|title=Narrative, Religion and Science: Fundamentalism Versus Irony, 1700–1999|year=2002|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-00983-6|page=234|author=Stephen Prickett}}</ref> [[Harold Pinter]],<ref name= "Adams" /> [[Tanya Reinhart]], [[Arundhati Roy]], [[Edward Said]],<ref>{{cite book|title=Edward Said and the Religious Effects of Culture|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-77810-7|page=116|author=William D. Hart}}</ref> [[John Searle]],<ref>{{cite web|title=A Special Supplement: Chomsky's Revolution in Linguistics|url=http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/1972/jun/29/a-special-supplement-chomskys-revolution-in-lingui/|publisher=NYREV, Inc.|author=John R. Searle|date=June 29, 1972}}</ref> [[Neil Smith (linguist)|Neil Smith]], [[Aaron Swartz]],<ref>{{cite web|title=The Book That Changed My Life|url=http://www.aaronsw.com/weblog/epiphany|publisher=Raw Thought|accessdate=8 January 2014|author=Aaron Swartz|date=May 15, 2006}}</ref> [[Crispin Wright]],<ref name="Chomsky Amid the Philosophers" /> and many others}} |

|||

|prizes = {{collapsible list| title = {{nbsp}} | {{Plainlist| |

|||

*[[Guggenheim Fellowship]] <small>(1971)</small> |

|||

*[[APA Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions to Psychology]] <small>(1984)</small> |

|||

*[[Orwell Award]] <small>(1987, 1989)</small> |

|||

*[[Kyoto Prize in Basic Sciences]] <small>(1988)</small> |

|||

*[[Helmholtz Medal]] <small>(1996)</small> |

|||

*[[Benjamin Franklin Medal (Franklin Institute)|Benjamin Franklin Medal in Computer and Cognitive Science]] <small>(1999)</small> |

|||

*[[Sydney Peace Prize]] <small>(2011)</small> }} }} |

|||

|spouse = {{Plainlist| |

|||

* [[Carol Chomsky|Carol Doris Schatz]] <small>(1949–2008; her death)</small> |

|||

* Valeria Wasserman <small>(2014–present)</small> |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

| signature = Noam Chomsky signature.svg |

|||

|children = {{Plainlist| |

|||

| website = {{URL|https://chomsky.info}} |

|||

* [[Aviva Chomsky|Aviva]] <small>(b. 1957)</small> |

|||

| spouse = {{Plainlist| |

|||

* Diane <small>(b. 1960)</small> |

|||

* {{marriage|[[Carol Chomsky|Carol Schatz]]|1949| December 19, 2008|end=died}} |

|||

* Harry <small>(b. 1967)</small> |

|||

* {{marriage|Valeria Wasserman|2014}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

| children = 3, including [[Aviva Chomsky|Aviva]] |

|||

|website = {{URL|https://chomsky.info/}} |

|||

| discipline = [[Linguistics]], [[analytic philosophy]], [[cognitive science]], [[political criticism]] |

|||

|signature = Noam Chomsky signature.svg |

|||

| work_institutions = {{Plainlist| |

|||

* [[Massachusetts Institute of Technology]] (1955–present) |

|||

* [[Institute for Advanced Study]] (1958–1959) |

|||

* [[University of Arizona]] (2017–present) |

|||

}} |

|||

| education = [[University of Pennsylvania]] {{awrap|([[Bachelor of Arts|BA]], [[Master of Arts|MA]], [[PhD]])}} |

|||

| awards = {{collapsible list| title = {{nbsp}} | {{indented plainlist| |

|||

* [[Guggenheim Fellowship]] (1971) |

|||

* [[Member of the National Academy of Sciences]] (1972) |

|||

* [[APA Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions to Psychology]] (1984) |

|||

* [[Orwell Award]] (1987, 1989) |

|||

* [[Kyoto Prize in Basic Sciences]] (1988) |

|||

* [[Helmholtz Medal]] (1996) |

|||

* [[Benjamin Franklin Medal (Franklin Institute)|Benjamin Franklin Medal in Computer and Cognitive Science]] (1999) |

|||

* [[Sydney Peace Prize]] (2011) |

|||

* [[Nuclear Age Peace Foundation]] (2014) |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

| school_tradition = [[Anarcho-syndicalism]], [[libertarian socialism]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Anarchism US}} |

|||

<!--Basic introduction; who he is--> |

<!--Basic introduction; who he is--> |

||

'''Avram Noam Chomsky''' ({{IPAc-en |

'''Avram Noam Chomsky''' ({{IPAc-en|n|oʊ|m|_|ˈ|tʃ|ɒ|m|s|k|i|audio=Noam Chomsky.ogg}} {{respell|nohm|_|CHOM|skee}}; born December 7, 1928) is an American professor and [[public intellectual]] known for his work in [[linguistics]], [[political activism]], and [[social criticism]]. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics",{{efn|name=father}} Chomsky is also a major figure in [[analytic philosophy]] and one of the founders of the field of [[cognitive science]]. He is a laureate professor of linguistics at the [[University of Arizona]] and an [[institute professor]] emeritus at the [[Massachusetts Institute of Technology]] (MIT). Among the most cited living authors, Chomsky has written more than 150 books on topics such as linguistics, war, and politics. In addition to his work in linguistics, since the 1960s Chomsky has been an influential voice on the [[American Left|American left]] as a consistent critic of [[U.S. foreign policy]], [[Criticism of capitalism|contemporary capitalism]], and [[Corporate influence on politics in the United States|corporate influence]] on political institutions and the media. |

||

<!--Early life up until 1966--> |

<!--Early life up until 1966--> |

||

Born to |

Born to [[Ashkenazi Jews|Ashkenazi Jewish]] immigrants in [[Philadelphia]], Chomsky developed an early interest in [[anarchism]] from alternative bookstores in [[New York City]]. He studied at the [[University of Pennsylvania]]. During his postgraduate work in the [[Harvard Society of Fellows]], Chomsky developed the theory of [[transformational grammar]] for which he earned his doctorate in 1955. That year he began teaching at MIT, and in 1957 emerged as a significant figure in linguistics with his landmark work ''[[Syntactic Structures]]'', which played a major role in remodeling the study of language. From 1958 to 1959 Chomsky was a [[National Science Foundation]] fellow at the [[Institute for Advanced Study]]. He created or co-created the [[universal grammar]] theory, the [[generative grammar]] theory, the [[Chomsky hierarchy]], and the [[minimalist program]]. Chomsky also played a pivotal role in the decline of linguistic [[behaviorism]], and was particularly critical of the work of [[B. F. Skinner]]. |

||

<!--Later life post-1967--> |

<!--Later life post-1967--> |

||

An outspoken [[ |

An outspoken [[opponent of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War]], which he saw as an act of [[American imperialism]], in 1967 Chomsky rose to national attention for his [[Anti-war movement|anti-war]] essay "[[The Responsibility of Intellectuals]]". Becoming associated with the [[New Left]], he was arrested multiple times for his activism and placed on President [[Richard Nixon]]'s [[Master list of Nixon's political opponents|list of political opponents]]. While expanding his work in linguistics over subsequent decades, he also became involved in the [[linguistics wars]]. In collaboration with [[Edward S. Herman]], Chomsky later articulated the [[propaganda model]] of [[media criticism]] in ''[[Manufacturing Consent]]'', and worked to expose the [[Indonesian occupation of East Timor]]. His defense of unconditional [[freedom of speech]], including that of [[Holocaust denial]], generated significant controversy in the [[Faurisson affair]] of the 1980s. Chomsky's commentary on the [[Cambodian genocide]] and the [[Bosnian genocide]] also generated controversy. Since retiring from active teaching at MIT, he has continued his vocal political activism, including opposing the [[2003 invasion of Iraq]] and supporting the [[Occupy movement]]. An [[Anti-Zionism|anti-Zionist]], Chomsky considers [[Israel and apartheid|Israel's treatment of Palestinians]] to be worse than [[Apartheid in South Africa|South African–style apartheid]],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.democracynow.org/blog/2014/8/8/noam_chomsky_what_israel_is_doing|title=Noam Chomsky: Israel's Actions in Palestine are "Much Worse Than Apartheid" in South Africa|website=Democracy Now!}}</ref> and criticizes U.S. support for Israel. |

||

<!--Brief assessment of Chomsky's reception and legacy:--> |

<!--Brief assessment of Chomsky's reception and legacy:--> |

||

Chomsky is widely recognized as having helped to spark the [[cognitive revolution]] in the [[human sciences]], contributing to the development of a new [[Cognitivism (psychology)|cognitivistic]] framework for the study of language and the mind. Chomsky remains a leading critic of [[U.S. foreign policy]], contemporary [[capitalism]], U.S. involvement and Israel's role in the [[Israeli–Palestinian conflict]], and [[Mass media in the United States|mass media]]. Chomsky and his ideas remain highly influential in the [[anti-capitalist]] and [[anti-imperialist]] movements. Since 2017, he has been Agnese Nelms Haury Chair in the Agnese Nelms Haury Program in Environment and Social Justice at the [[University of Arizona]]. |

|||

{{TOC limit|4}} |

|||

== |

==Life== |

||

===Childhood: 1928–1945=== |

|||

Chomsky was born on December 7, 1928, in the [[East Oak Lane, Philadelphia|East Oak Lane]] neighborhood of [[Philadelphia]], Pennsylvania.{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xv|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2p=9|3a1=McGilvray|3y=2014|3p=3}} His parents, [[William Chomsky]] and Elsie Simonofsky, were [[Jew]]ish immigrants.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=9–10|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=11}} William had fled the [[Russian Empire]] in 1913 to escape conscription and worked in Baltimore [[sweatshop]]s and Hebrew elementary schools before attending university.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=9}} After moving to Philadelphia, William became principal of the [[Congregation Mikveh Israel]] religious school and joined the [[Gratz College]] faculty. He placed great emphasis on educating people so that they would be "well integrated, free and independent in their thinking, concerned about improving and enhancing the world, and eager to participate in making life more meaningful and worthwhile for all", a mission that shaped and was subsequently adopted by his son.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=11}} Elsie, who also taught at Mikveh Israel, shared her leftist politics and care for social issues with her sons.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=11}} |

|||

Noam's only sibling, David Eli Chomsky (1934–2021), was born five years later, and worked as a cardiologist in Philadelphia.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=11}}<ref>{{cite news|title=Dr. David Chomsky, a cardiologist who made house calls, dies at 86|url=https://www.inquirer.com/obituaries/david-chomsky-obituary-philadelphia-doctor-noam-judith-20210712.html|date=July 12, 2021|first=Valerie|last=Russ|newspaper=[[The Philadelphia Inquirer]]|access-date=September 10, 2021|archive-date=July 12, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210712200201/https://www.inquirer.com/obituaries/david-chomsky-obituary-philadelphia-doctor-noam-judith-20210712.html|url-status=live}}</ref> The brothers were close, though David was more easygoing while Noam could be very competitive. They were raised Jewish, being taught [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] and regularly involved with discussing the political theories of [[Zionism]]; the family was particularly influenced by the [[Left Zionist]] writings of [[Ahad Ha'am]].{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=11–13}} He faced [[antisemitism]] as a child, particularly from Philadelphia's Irish and German communities.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=15}} |

|||

===Childhood: 1928–45=== |

|||

Avram Noam Chomsky was born on December 7, 1928, in the [[East Oak Lane, Philadelphia|East Oak Lane]] neighborhood of [[Philadelphia]], [[Pennsylvania]].{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xv|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2p=9|3a1=McGilvray|3y=2014|3p=3}} His father was [[William Chomsky|William "Zev" Chomsky]], an Ashkenazi Jew originally from [[Ukraine]] who had fled to the United States in 1913. Having studied at [[Johns Hopkins University]], William went on to become school principal of the [[Congregation Mikveh Israel]] religious school, and in 1924 was appointed to the faculty at [[Gratz College]] in Philadelphia. Chomsky's mother was the Belarusian-born Elsie Simonofsky (1903–1972), a teacher and activist whom William had met while working at Mikveh Israel.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=9–10|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=11}} |

|||

Chomsky attended the independent, [[Deweyite]] [[Oak Lane Country Day School]]{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xv|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2pp=15–17|3a1=Sperlich|3y=2006|3p=12|4a1=McGilvray|4y=2014|4p=3}} and Philadelphia's [[Central High School (Philadelphia)|Central High School]], where he excelled academically and joined various clubs and societies, but was troubled by the school's hierarchical and domineering teaching methods.{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xv|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2pp=21–22|3a1=Sperlich|3y=2006|3p=14|4a1=McGilvray|4y=2014|4p=4}} He also attended Hebrew High School at Gratz College, where his father taught.{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xv|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2pp=15–17}} |

|||

{{Quote box|width=246px|align=left|quote=What motivated his [political] interests? A powerful curiosity, exposure to divergent opinions, and an unorthodox education have all been given as answers to this question. He was clearly struck by the obvious contradictions between his own readings and mainstream press reports. The measurement of the distance between the realities presented by these two sources, and the evaluation of why such a gap exists, remained a passion for Chomsky.|source=Biographer [[Robert F. Barsky]], 1997{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=30–31}}}} |

|||

Chomsky has described his parents as "normal [[Roosevelt Democrats]]" with [[center-left politics]], but relatives involved in the [[International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union]] exposed him to [[socialism]] and [[far-left politics]].{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=14|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2pp=11, 14–15}} He was substantially influenced by his uncle and the Jewish leftists who frequented his New York City newspaper stand to debate current affairs.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=23|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2pp=12, 14–15, 67|3a1=McGilvray|3y=2014|3p=4}} Chomsky himself often visited left-wing and anarchist bookstores when visiting his uncle in the city, voraciously reading political literature.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=23}} He became absorbed in the story of the 1939 [[fall of Barcelona]] and suppression of the [[anarchism in Spain|Spanish anarchosyndicalist]] movement, writing his first article on the topic at the age of 10.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=16–19|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=13}} That he came to identify with anarchism first rather than another leftist movement, he described as a "lucky accident".{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=18}} Chomsky was firmly [[Anti-Stalinist left|anti-Bolshevik]] by his early teens.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=18}} |

|||

Noam was the Chomsky family's first child. His younger brother, David Eli Chomsky, was born five years later.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=11–13|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=11}} The brothers were close, although David was more easygoing while Noam could be very competitive.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=11–13}} Chomsky and his brother were raised Jewish, being taught Hebrew and regularly discussing the political theories of [[Zionism]]; the family was particularly influenced by the [[Left Zionism|Left Zionist]] writings of [[Ahad Ha'am]].{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=11–13|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=11}} As a Jew, Chomsky faced [[anti-semitism]] as a child, particularly from the Irish and German communities living in Philadelphia.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=15}} |

|||

Chomsky described his parents as "normal [[Franklin D. Roosevelt|Roosevelt]] [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democrats]]" who had a [[centre-left politics|center-left]] position on the political spectrum; however, he was exposed to [[far-left politics]] through other members of the family, a number of whom were [[socialism|socialists]] involved in the [[International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union]].{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=14|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2pp=11, 14–15}} He was substantially influenced by his uncle who owned a newspaper stand in [[New York City]], where Jewish leftists came to debate the issues of the day.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=23|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2pp=12, 14–15, 67|3a1=McGilvray|3y=2014|3p=4}} Whenever visiting his uncle, Chomsky frequented left-wing and anarchist bookstores in the city, voraciously reading political literature.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=23}} He later described his discovery of [[anarchism]] as "a lucky accident",{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=17–19}} because it allowed him to become critical of other far-left ideologies, namely [[Stalinism]] and other forms of [[Marxism–Leninism]].{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=17–19|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2pp=16, 18}} |

|||

Chomsky's primary education was at [[Oak Lane Day School|Oak Lane Country Day School]], an independent [[Deweyism|Deweyite]] institution that focused on allowing its pupils to pursue their own interests in a non-competitive atmosphere.{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xv|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2pp=15–17|3a1=Sperlich|3y=2006|3p=12|4a1=McGilvray|4y=2014|4p=3}} It was here, at age 10, that he wrote his first article, on the spread of [[fascism]], following the [[Catalonia Offensive|fall of Barcelona]] to [[Francisco Franco]]'s fascist army in the [[Spanish Civil War]].{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xv|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2pp=15–17|3a1=Sperlich|3y=2006|3p=13|4a1=McGilvray|4y=2014|4p=3}} At age 12, Chomsky moved on to secondary education at [[Central High School (Philadelphia)|Central High School]], where he joined various clubs and societies and excelled academically, but was troubled by the hierarchical and regimented method of teaching used there.{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xv|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2pp=21–22|3a1=Sperlich|3y=2006|3p=14|4a1=McGilvray|4y=2014|4p=4}} From the age of 12 or 13, he identified more fully with anarchist politics.{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xv|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2pp=15–17}} |

|||

===University: 1945–55=== |

|||

{{multiple image |

|||

| direction = vertical |

|||

| footer = Chomsky's ''[[almae matres]]'', the [[University of Pennsylvania]] and the [[Harvard Society of Fellows]] |

|||

| image1 = UPenn shield with banner.svg |

|||

| image2 = Harvard University logo.PNG |

|||

}} |

|||

===University: 1945–1955=== |

|||

In 1945, Chomsky, aged 16, embarked on a general program of study at the [[University of Pennsylvania]], where he explored philosophy, logic, and languages and developed a primary interest in learning [[Arabic]].{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=47|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=16}} Living at home, he funded his undergraduate degree by teaching Hebrew.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=47}} However, he was frustrated with his experiences at the university, and considered dropping out and moving to a [[kibbutz]] in [[Mandatory Palestine]].{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=17}} His intellectual curiosity was reawakened through conversations with the Russian-born linguist [[Zellig Harris]], whom he first met in a political circle in 1947. Harris introduced Chomsky to the field of theoretical linguistics and convinced him to major in the subject.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=48–51|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2pp=18–19, 31}} Chomsky's [[Bachelor of Arts|B.A.]] honors thesis was titled "Morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew", and involved him applying Harris's methods to the language.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=51–52|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=32}} Chomsky revised this thesis for his [[Master of Arts|M.A.]], which he received at Penn in 1951; it would subsequently be published as a book.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=51–52|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=33}} He also developed his interest in philosophy while at university, in particular under the tutelage of his teacher [[Nelson Goodman]].{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=33}} |

|||

[[File:Carol Chomsky.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Carol Schatz]] married Chomsky in 1949.]] |

|||

In 1945, at the age of 16, Chomsky began a general program of study at the [[University of Pennsylvania]], where he explored philosophy, logic, and languages and developed a primary interest in learning [[Arabic]].{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=47|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=16}} Living at home, he funded his undergraduate degree by teaching Hebrew.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=47}} Frustrated with his experiences at the university, he considered dropping out and moving to a [[kibbutz]] in [[Mandatory Palestine]],{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=17}} but his intellectual curiosity was reawakened through conversations with the linguist [[Zellig Harris]], whom he first met in a political circle in 1947. Harris introduced Chomsky to the field of theoretical linguistics and convinced him to major in the subject.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=48–51|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2pp=18–19, 31}} Chomsky's [[Bachelor of Arts|BA]] honors thesis, "Morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew", applied Harris's methods to the language.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=51–52|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=32}} Chomsky revised this thesis for his [[Master of Arts|MA]], which he received from the University of Pennsylvania in 1951; it was subsequently published as a book.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=51–52|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=33}} He also developed his interest in philosophy while at university, in particular under the tutelage of [[Nelson Goodman]].{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=33}} |

|||

From 1951 to 1955, Chomsky was |

From 1951 to 1955, Chomsky was a member of the [[Society of Fellows]] at [[Harvard University]], where he undertook research on what became his doctoral dissertation.{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xv|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2p=79|3a1=Sperlich|3y=2006|3p=20}} Having been encouraged by Goodman to apply,{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=34}} Chomsky was attracted to Harvard in part because the philosopher [[Willard Van Orman Quine]] was based there. Both Quine and a visiting philosopher, [[J. L. Austin]] of the [[University of Oxford]], strongly influenced Chomsky.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|pp=33–34}} In 1952, Chomsky published his first academic article in ''[[The Journal of Symbolic Logic]]''.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=34}} Highly critical of the established [[behaviorist]] currents in linguistics, in 1954, he presented his ideas at lectures at the [[University of Chicago]] and [[Yale University]].{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=81}} He had not been registered as a student at Pennsylvania for four years, but in 1955 he submitted a thesis setting out his ideas on [[transformational grammar]]; he was awarded a Doctor of Philosophy degree for it, and it was privately distributed among specialists on microfilm before being published in 1975 as part of ''[[The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory]]''.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=83–85|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=36|3a1=McGilvray|3y=2014|3pp=4–5}} Harvard professor [[George Armitage Miller]] was impressed by Chomsky's thesis and collaborated with him on several technical papers in [[mathematical linguistics]].{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=38}} Chomsky's doctorate exempted him from [[conscription in the United States|compulsory military service]], which was otherwise due to begin in 1955.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=36}} |

||

In 1947, Chomsky began a romantic relationship with [[Carol Doris Schatz]], whom he had known since early childhood. They married in 1949.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=13, 48, 51–52|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2pp=18–19}} After Chomsky was made a Fellow at Harvard, the couple moved to the [[Allston]] area of Boston and remained there until 1965, when they relocated to the suburb of [[Lexington, Massachusetts|Lexington]].{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=20}} The couple took a Harvard travel grant to Europe in 1953.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|pp=20–21}} He enjoyed living in [[Hashomer Hatzair]]'s [[HaZore'a]] [[kibbutz]] while in Israel, but was appalled by his interactions with Jewish nationalism, [[anti-Arab racism]] and, within the kibbutz's leftist community, [[Stalinism]].{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=82|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2pp=20–21}} On visits to New York City, Chomsky continued to frequent the office of the Yiddish anarchist journal ''[[Fraye Arbeter Shtime]]'' and became enamored with the ideas of [[Rudolf Rocker]], a contributor whose work introduced Chomsky to the link between [[anarchism]] and [[classical liberalism]].{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=24|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=13}} Chomsky also read other political thinkers: the anarchists [[Mikhail Bakunin]] and [[Diego Abad de Santillán]], democratic socialists [[George Orwell]], [[Bertrand Russell]], and [[Dwight Macdonald]], and works by Marxists [[Karl Liebknecht]], [[Karl Korsch]], and [[Rosa Luxemburg]].{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=24–25}} His politics were reaffirmed by Orwell's depiction of [[Barcelona]]'s functioning anarchist society in ''[[Homage to Catalonia]]'' (1938).{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=26}} Chomsky read the leftist journal ''[[Politics (1940s magazine)|Politics]]'', which furthered his interest in anarchism,{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=34–35}} and the [[council communist]] periodical ''[[International Council Correspondence|Living Marxism]]'', though he rejected the Marxist orthodoxy of its editor, [[Paul Mattick]].{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=36}} |

|||

{{double image|left|Rudolf Rocker.jpg|155|George Orwell press photo.jpg|152|The work of anarcho-syndicalist [[Rudolf Rocker]] (left) and democratic socialist [[George Orwell]] (right) significantly influenced the young Chomsky.}} |

|||

In 1947, Chomsky entered into a romantic relationship with [[Carol Chomsky|Carol Doris Schatz]], whom he had known since they were toddlers, and they married in 1949.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=13, 48, 51–52|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2pp=18–19}} After Chomsky was made a Fellow at Harvard, the couple moved to an apartment in the [[Allston]] area of [[Boston]], remaining there until 1965, when they relocated to the city's [[Lexington, Massachusetts|Lexington]] area.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=20}} In 1953 the couple took up a Harvard travel grant in order to visit Europe, traveling from England through France and Switzerland and into Italy.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|pp=20–21}} On that same trip they also spent six weeks at [[Hashomer Hatzair]]'s [[HaZore'a]] kibbutz in the newly established Israel; although enjoying himself, Chomsky was appalled by the Jewish nationalism and [[Anti-Arabism|anti-Arab racism]] that he encountered in the country, as well as the pro-Stalinist trend that he thought pervaded the kibbutz's leftist community.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=82|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2pp=20–21}} |

|||

On visits to New York City, Chomsky continued to frequent the office of Yiddish anarchist journal ''[[Freie Arbeiter Stimme]]'', becoming enamored with the ideas of contributor [[Rudolf Rocker]], whose work introduced him to the link between anarchism and [[classical liberalism]].{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=24|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=13}} Other political thinkers whose work Chomsky read included the anarchist [[Diego Abad de Santillán]], democratic socialists [[George Orwell]], [[Bertrand Russell]], and [[Dwight Macdonald]], and works by Marxists [[Karl Liebknecht]], [[Karl Korsch]], and [[Rosa Luxemburg]].{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=24–25}} His readings convinced him of the desirability of an anarcho-syndicalist society, and he became fascinated by the anarcho-syndicalist communes set up during the [[Spanish Civil War]], which were documented in Orwell's ''[[Homage to Catalonia]]'' (1938).{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=26}} He avidly read leftist journal ''[[politics (magazine 1944-1949)|politics]]'', remarking that it "answered to and developed" his interest in anarchism,{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=34–35}} as well as the periodical ''[[International Council Correspondence|Living Marxism]]'', published by [[council communism|council communist]] [[Paul Mattick]]. Although rejecting its Marxist basis, Chomsky was heavily influenced by council communism, voraciously reading articles in ''Living Marxism'' written by [[Antonie Pannekoek]].{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=36–40}} He was also greatly interested in the Marlenite ideas of the [[Leninist League (US)|Leninist League]], an anti-Stalinist Marxist–Leninist group, sharing their views that the [[Second World War]] was orchestrated by Western capitalists and the Soviet Union's '[[state capitalism|state capitalists]]' to crush Europe's proletariat.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=43–44}} |

|||

===Early career: 1955–1966=== |

===Early career: 1955–1966=== |

||

Chomsky befriended two linguists at the [[Massachusetts Institute of Technology]] (MIT)—[[Morris Halle]] and [[Roman Jakobson]]—the latter of whom secured him an assistant professor position there in 1955. At MIT, Chomsky spent half his time on a [[mechanical translation]] project and half teaching a course on linguistics and philosophy.{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xv|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2pp=86–87|3a1=Sperlich|3y=2006|3pp=38–40}} He described MIT as open to experimentation where he was free to pursue his idiosyncratic interests.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=87}} MIT promoted him to the position of [[associate professor]] in 1957, and over the next year he was also a visiting professor at [[Columbia University]].{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xvi|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2p=91}} The Chomskys had their first child, [[Aviva Chomsky|Aviva]], that same year.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=91|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=22}} He also published his first book on linguistics, ''[[Syntactic Structures]]'', a work that radically opposed the dominant Harris–[[Leonard Bloomfield|Bloomfield]] trend in the field.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=88–91|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=40|3a1=McGilvray|3y=2014|3p=5|4a1=Chomsky|4y=2022}} Responses to Chomsky's ideas ranged from indifference to hostility, and his work proved divisive and caused "significant upheaval" in the discipline.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=88–91}} The linguist [[John Lyons (linguist)|John Lyons]] later asserted that ''Syntactic Structures'' "revolutionized the scientific study of language".{{sfn|Lyons|1978|p=1}} From 1958 to 1959 Chomsky was a [[National Science Foundation]] fellow at the [[Institute for Advanced Study]] in [[Princeton, New Jersey]].{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xvi|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2p=84}} |

|||

[[File:MIT Building 10 and the Great Dome, Cambridge MA.jpg|thumb|The [[Great Dome (MIT)|Great Dome]] at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT); Chomsky began working at MIT in 1955.]] |

|||

Chomsky had befriended two linguists at the [[Massachusetts Institute of Technology]] (MIT), [[Morris Halle]] and [[Roman Jakobson]], the latter of whom secured him an assistant professor position at MIT in 1955. There Chomsky spent half his time on a [[mechanical translation]] project, and the other half teaching a course on linguistics and philosophy.{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xv|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2pp=86–87|3a1=Sperlich|3y=2006|3pp=38–40}} He later described MIT as "a pretty free and open place, open to experimentation and without rigid requirements. It was just perfect for someone of my idiosyncratic interests and work."{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=87}} In 1957 MIT promoted him to the position of associate professor, and from 1957 to 1958 he was also employed by [[Columbia University]] as a visiting professor.{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xvi|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2p=91}} That same year, Chomsky's first child, a daughter named [[Aviva Chomsky|Aviva]], was born,{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=91|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=22}} and he published his first book on linguistics, ''[[Syntactic Structures]]'', a work that radically opposed the dominant [[Zellig Harris|Harris]]–[[Leonard Bloomfield|Bloomfield]] trend in the field.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=88–91|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=40|3a1=McGilvray|3y=2014|3p=5}} The response to Chomsky's ideas ranged from indifference to hostility, and his work proved divisive and caused "significant upheaval" in the discipline.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=88–91}} Linguist [[John Lyons (linguist)|John Lyons]] later asserted that it "revolutionized the scientific study of language".{{sfn|Lyons|1978|p=1}} From 1958 to 1959 Chomsky was a [[National Science Foundation]] fellow at the [[Institute for Advanced Study]] in [[Princeton, New Jersey]].{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xvi|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2p=84}} |

|||

Chomsky's provocative critique of [[B. F. Skinner]], who viewed language as learned behavior, and its challenge to the dominant behaviorist paradigm thrust Chomsky into the limelight. Chomsky argued that behaviorism underplayed the role of human creativity in learning language and overplayed the role of external conditions in influencing verbal behavior.{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=6|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2pp=96–99|3a1=Sperlich|3y=2006|3p=41|4a1=McGilvray|4y=2014|4p=5|5a1=MacCorquodale|5y=1970|5pp=83–99}}<!-- are all of these necessary? Barsky alone seems sufficient --> He proceeded to found MIT's graduate program in linguistics with Halle. In 1961, Chomsky [[received tenure]] and became a [[full professor]] in the Department of Modern Languages and Linguistics.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=101–102, 119|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=23}} He was appointed plenary speaker at the Ninth [[International Congress of Linguists]], held in 1962 in [[Cambridge, Massachusetts]], which established him as the ''de facto'' spokesperson of American linguistics.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=102}} Between 1963 and 1965 he consulted on a military-sponsored project to teach computers to understand natural English commands from military generals.{{sfn|Knight|2018a}} |

|||

Chomsky continued to publish his linguistic ideas throughout the decade, including in ''[[Aspects of the Theory of Syntax]]'' (1965), ''Topics in the Theory of Generative Grammar'' (1966), and ''[[Cartesian Linguistics: A Chapter in the History of Rationalist Thought]]'' (1966).{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=103}} Along with Halle, he also edited the ''[[Studies in Language]]'' series of books for [[Harper and Row]].{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=104}} As he began to accrue significant academic recognition and honors for his work, Chomsky lectured at the [[University of California, Berkeley]], in 1966.{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xvi|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2p=120}} These lectures were published as ''[[Language and Mind]]'' in 1968.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=122}} In the late 1960s, a high-profile intellectual rift later known as the [[linguistic wars]] developed between Chomsky and some of his colleagues and doctoral students—including [[Paul Postal]], [[John R. Ross|John Ross]], [[George Lakoff]], and [[James D. McCawley]]—who contended that Chomsky's syntax-based, interpretivist linguistics did not properly account for semantic context ([[general semantics]]). A post hoc assessment of this period concluded that the opposing programs ultimately were complementary, each informing the other.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=149–152}} |

|||

==Later life== |

|||

===Anti- |

===Anti-war activism and dissent: 1967–1975=== |

||

{{Quote box |

|||

{{Quote box|width=246px|align=left|quote=[I]t does not require very far-reaching, specialized knowledge to perceive that the United States was invading South Vietnam. And, in fact, to take apart the system of illusions and deception which functions to prevent understanding of contemporary reality [is] not a task that requires extraordinary skill or understanding. It requires the kind of normal skepticism and willingness to apply one's analytical skills that almost all people have and that they can exercise.|source=Chomsky on the Vietnam War{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=114}}}} |

|||

| width = 25em |

|||

| quote = [I]t does not require very far-reaching, specialized knowledge to perceive that the United States was invading South Vietnam. And, in fact, to take apart the system of illusions and deception which functions to prevent understanding of contemporary reality [is] not a task that requires extraordinary skill or understanding. It requires the kind of normal skepticism and willingness to apply one's analytical skills that almost all people have and that they can exercise. |

|||

| source = —Chomsky on the Vietnam War{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=114}}<!--Does the secondary source cite the primary source? It would be better to cite the primary source if a direct quotation--> |

|||

}} |

|||

Chomsky joined [[protests against U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War]] in 1962, speaking on the subject at small gatherings in churches and homes.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=78}} His 1967 critique of U.S. involvement, "[[The Responsibility of Intellectuals]]", among other contributions to ''[[The New York Review of Books]]'', debuted Chomsky as a public dissident.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=120, 122|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=83}} This essay and other political articles were collected and published in 1969 as part of Chomsky's first political book, ''[[American Power and the New Mandarins]]''.{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xvii|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2p=123|3a1=Sperlich|3y=2006|3p=83}} He followed this with further political books, including ''At War with Asia'' (1970), ''The Backroom Boys'' (1973), ''[[For Reasons of State]]'' (1973), and ''Peace in the Middle East?'' (1974), published by [[Pantheon Books]].{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1pp=xvi–xvii|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2p=163|3a1=Sperlich|3y=2006|3p=87}} These publications led to Chomsky's association with the American [[New Left]] movement,{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=5|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2p=123}} though he thought little of prominent New Left intellectuals [[Herbert Marcuse]] and [[Erich Fromm]] and preferred the company of activists to that of intellectuals.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=134–135}} Chomsky remained largely ignored by the mainstream press throughout this period.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=162–163}} |

|||

Chomsky also became involved in left-wing activism. Chomsky refused to pay half his taxes, publicly supported students who [[Vietnam War draft evaders|refused the draft]], and was arrested while participating in an [[Anti-war movement|anti-war]] [[teach-in]] outside the Pentagon.{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=5|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2pp=127–129}} During this time, Chomsky co-founded the anti-war collective [[RESIST (non-profit)|RESIST]] with [[Mitchell Goodman]], [[Denise Levertov]], [[William Sloane Coffin]], and [[Dwight Macdonald]].{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=5|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2pp=127–129|3a1=Sperlich|3y=2006|3pp=80–81}} Although he questioned the objectives of the [[1968 student protests]],{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=121–122, 131}} Chomsky regularly gave lectures to student activist groups and, with his colleague Louis Kampf, ran undergraduate courses on politics at MIT independently of the conservative-dominated [[political science]] department.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=121|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=78}} When student activists campaigned to stop weapons and counterinsurgency research at MIT, Chomsky was sympathetic but felt that the research should remain under MIT's oversight and limited to systems of deterrence and defense.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=121–122, 140–141|2a1=Albert|2y=2006|2p=98|3a1=Knight|3y=2016|3p=34}} Chomsky has acknowledged that his MIT lab's funding at this time came from the military.{{sfn|Chomsky|1996|p=102}} He later said he considered resigning from MIT during the Vietnam War.{{sfn|Allott|Knight|Smith|2019|p=62}} There has since been a wide-ranging debate about what effects Chomsky's employment at MIT had on his political and linguistic ideas.{{sfnm|1a1=Hutton|1y=2020|1p=32|2a1=Harris|2y=2021|2pp=399–400, 426, 454}} |

|||

Chomsky first involved himself in active political protest against U.S. involvement in the [[Vietnam War]] in 1962, speaking on the subject at small gatherings in churches and homes.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=78}} However, it was not until 1967 that he publicly entered the debate on United States foreign policy.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=120}} In February he published a widely read essay in ''[[The New York Review of Books]]'' entitled "[[The Responsibility of Intellectuals]]", in which he criticized the country's involvement in the conflict; the essay was based on an earlier talk that he had given to Harvard's Foundation for Jewish Campus Life.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=122|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=83}} He expanded on his argument to produce his first political book, ''[[American Power and the New Mandarins]],'' which was published in 1969 and soon established him at the forefront of American dissent.{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xvii|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2pp=122–123|3a1=Sperlich|3y=2006|3p=83}} His other political books of the time included ''At War with Asia'' (1971), ''The Backroom Boys'' (1973), ''For Reasons of State'' (1973), and ''Peace in the Middle East?'' (1975), published by [[Pantheon Books]].{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xvi–xvii|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2p=163|3a1=Sperlich|3y=2006|3p=87}} Coming to be associated with the American [[New Left]] movement,{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=5|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2p=123}} he nevertheless thought little of prominent New Left intellectuals [[Herbert Marcuse]] and [[Erich Fromm]], and preferred the company of activists to intellectuals.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=134–135}} Although ''The New York Review of Books'' did publish contributions from Chomsky and other leftists from 1967 to 1973, when an editorial change put a stop to it,{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=162–163|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=87}} he was virtually ignored by the rest of the mainstream press throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=162–163}} |

|||

{{external media |

|||

Along with his writings, Chomsky also became actively involved in left-wing activism. Refusing to pay half his taxes, he publicly supported students who refused [[Conscription in the United States|the draft]], and was arrested for being part of an anti-war teach-in outside [[the Pentagon]].{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=5|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2pp=127–129}} During this time, Chomsky, along with [[Mitchell Goodman]], [[Denise Levertov]], [[William Sloane Coffin]], and [[Dwight Macdonald]], also founded the anti-war collective [[RESIST (non-profit)|RESIST]].{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=5|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2pp=127–129|3a1=Sperlich|3y=2006|3pp=80–81}} Although he questioned the objectives of the [[1968 student protests]],{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=121–122, 131}} he gave many lectures to student activist groups; furthermore, he and his colleague Louis Kampf began running undergraduate courses on politics at MIT, independently of the conservative-dominated [[political science]] department.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=121|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=78}} During this period, MIT's various departments were researching helicopters, smart bombs and counterinsurgency techniques for the war in Vietnam and, as Chomsky says, "a good deal of [nuclear] missile guidance technology was developed right on the MIT campus."<ref>Michael Albert (2006). ''Remembering Tomorrow: From the politics of opposition to what we are for''. Seven Stories Press. pp. 97–99; C.P. Otero (1988). ''Noam Chomsky: Language and politics''. Black Rose. p. 247.</ref> As Chomsky elaborates, "[MIT was] about 90% Pentagon funded at that time. And I personally was right in the middle of it. I was in a military lab ... the Research Laboratory for Electronics."<ref>G.D. White (2000). ''Campus Inc.: Corporate power in the ivory tower''. Prometheus Books. pp. 445–6.</ref> By 1969, student activists were actively campaigning "to stop the war research" at MIT.<ref>Stephen Shalom, [http://nova.wpunj.edu/newpolitics/issue23/shalom23.htm 'Review of Noam Chomsky: A Life of Dissent, by Robert F. Barsky'], ''New Politics'', NS6(3), Issue 23. Retrieved 2016-10-7.</ref> Chomsky was sympathetic to the students but he also thought it best to keep such research on campus and he proposed that it should be restricted to what he called "systems of a purely defensive and deterrent character".<ref>Barsky 1997, pp. 121–2, 140-1; Albert 2006, p. 98; Knight 2016, p. 34.</ref> During this period, MIT had six of its anti-war student activists sentenced to prison terms. Chomsky says MIT's students suffered things that "should not have happened", though he has also described MIT as "the freest and the most honest and has the best relations between faculty and students than at any other ... [with] quite a good record on civil liberties."<ref>Albert 2006, pp. 107–8; Knight 2016, pp. 36–8, 249.</ref> In 1970 he visited the Vietnamese city of [[Hanoi]] to give a lecture at the [[Hanoi University of Science and Technology]]; on this trip he also toured Laos to visit the refugee camps created by the war, and in 1973 he was among those leading a committee to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the [[War Resisters League]].{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=153|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2pp=24–25, 84–85}} |

|||

| topic = Chomsky participating in the anti-Vietnam War [[March on the Pentagon]], October 21, 1967 |

|||

| image1 = [https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/view-of-demonstrators-during-the-march-on-the-pentagon-news-photo/108986037 Chomsky with other public figures] |

|||

| image2 = [https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/view-of-demonstrators-as-they-pass-the-lincoln-memorial-news-photo/152911351 The protesters passing the Lincoln Memorial en route to the Pentagon] |

|||

}}<!--Is this media of the same march at which he was arrested? If so, making that connection clearer would improve the value to readers.--> |

|||

Chomsky's anti-war activism led to his arrest on multiple occasions and he was on President [[Richard Nixon's master list of political opponents]].{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=124|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=80}} Chomsky was aware of the potential repercussions of his civil disobedience, and his wife began studying for her own doctorate in linguistics to support the family in the event of Chomsky's imprisonment or joblessness.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=123–124|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=22}} Chomsky's scientific reputation insulated him from administrative action based on his beliefs.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=143}} In 1970 he visited southeast Asia to lecture at Vietnam's [[Hanoi University of Science and Technology]] and toured war refugee camps in [[Laos]]. In 1973 he helped lead a committee commemorating the 50th anniversary of the [[War Resisters League]].{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=153|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2pp=24–25, 84–85}} |

|||

[[Image:Nixon 30-0316a.jpg|thumb|right|200px|President [[Richard Nixon]] placed Chomsky on his 'Enemies List'.]] |

|||

Chomsky's work in linguistics continued to gain international recognition as he [[List of honorary degrees awarded to Noam Chomsky|received multiple honorary doctorates]].{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1pp=xv–xvi|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2pp=120, 143}} He delivered [[public lectures]] at the [[University of Cambridge]], [[Columbia University]] ([[Woodbridge Lectures]]), and [[Stanford University]].{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=156}} His appearance in a [[Chomsky–Foucault debate|1971 debate]] with French [[continental philosopher]] [[Michel Foucault]] positioned Chomsky as a symbolic figurehead of [[analytic philosophy]].{{sfn|Greif|2015|pp=312–313}} He continued to publish extensively on linguistics, producing ''Studies on Semantics in Generative Grammar'' (1972),{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=143}} an enlarged edition of ''[[Language and Mind]]'' (1972),{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=51}} and ''[[Reflections on Language]]'' (1975).{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=51}} In 1974 Chomsky became a [[corresponding fellow of the British Academy]].{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=156}} |

|||

As a result of his anti-war activism, Chomsky was ultimately arrested on multiple occasions, and U.S. President [[Richard Nixon]] included him on the [[Master list of Nixon's political opponents|master version]] of his [[Nixon's Enemies List|Enemies List]].{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=124|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=80}} He was aware of the potential repercussions of his civil disobedience, and his wife began studying for her own Ph.D. in linguistics in order to support the family in the event of Chomsky's imprisonment or loss of employment.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=123–124|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=22}} However, MIT — despite being under some pressure to do so — refused to fire him due to his influential standing in the field of linguistics.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=143}} His work in this area continued to gain international recognition; in 1967 he received honorary doctorates from both the [[University of London]] and the [[University of Chicago]][[Doctor of Humane Letters|.]]{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xv–xvi|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2p=120}} In 1970, [[Loyola University Chicago|Loyola University]] and [[Swarthmore College]] also awarded him honorary D.H.L.'s, as did [[Bard College]] in 1971, [[Delhi University]] in 1972, and the [[University of Massachusetts]] in 1973.{{sfnm|1a1=Lyons|1y=1978|1p=xv–xvi|2a1=Barsky|2y=1997|2p=143}} |

|||

===Edward S. Herman and the Faurisson affair: 1976–1980=== |

|||

In 1971 Chomsky gave the Bertrand Russell Memorial Lectures at the [[University of Cambridge]], which were published as ''Problems of Knowledge and Freedom'' later that year. He also delivered the [[Whidden Lectures]] at [[McMaster University]], the [[Huizinga Lecture]] at [[Leiden University]] in the Netherlands, the Woodbridge Lectures at [[Columbia University]], and the Kant Lectures at [[Stanford University]].{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=156}} In 1971 he partook in a televised debate with French philosopher [[Michel Foucault]] on Dutch television, entitled ''Human Nature: Justice versus Power''.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=192–195|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=52|3a1=McGilvray|3y=2014|3p=222}} Although largely agreeing with Foucault's ideas, he was critical of [[post-modernism]] and French philosophy generally, believing that post-modern leftist philosophers used obfuscating language which did little to aid the cause of the working-classes{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=192–195|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=53}} and lambasting France as having "a highly parochial and remarkably illiterate culture."{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=192–195}} Chomsky also continued to publish prolifically in linguistics, publishing ''Studies on Semantics in Generative Grammar'' (1972),{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=143}} an enlarged edition of ''Language and Mind'' (1972),{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=51}} and ''Reflections on Language'' (1975).{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=51}} In 1974 he became a corresponding fellow of the [[British Academy]].{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=156}} |

|||

{{See also|Cambodian genocide denial#Chomsky and Herman|Faurisson affair}} |

|||

[[File:Prof dr Noam Chomsky, Bestanddeelnr 929-4752 (cropped).jpg|thumb|upright|Chomsky in 1977]] |

|||

In the late 1970s and 1980s, Chomsky's linguistic publications expanded and clarified his earlier work, addressing his critics and updating his grammatical theory.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=175}} His political talks often generated considerable controversy, particularly when he criticized the Israeli government and military.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=167, 170}} In the early 1970s Chomsky began collaborating with [[Edward S. Herman]], who had also published critiques of the U.S. war in Vietnam.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=157}} Together they wrote ''[[Counter-Revolutionary Violence: Bloodbaths in Fact & Propaganda]]'', a book that criticized U.S. military involvement in Southeast Asia and the mainstream media's failure to cover it. Warner Modular published it in 1973, but [[Warner Communications|its parent company]] disapproved of the book's contents and ordered all copies destroyed.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=160–162|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=86}} |

|||

While mainstream publishing options proved elusive, Chomsky found support from [[Michael Albert]]'s [[South End Press]], an activist-oriented publishing company.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=85}} In 1979, South End published Chomsky and Herman's revised ''Counter-Revolutionary Violence'' as the two-volume ''[[The Political Economy of Human Rights]]'',{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=187|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=86}} which compares U.S. media reactions to the [[Khmer Rouge rule of Cambodia|Cambodian genocide]] and the [[Indonesian occupation of East Timor]]. It argues that because Indonesia was a U.S. ally, U.S. media ignored the East Timorese situation while focusing on events in Cambodia, a U.S. enemy.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=187}} Chomsky's response included two testimonials before the United Nations' [[Special Committee on Decolonization]], successful encouragement for American media to cover the occupation, and meetings with refugees in [[Lisbon]].{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=103}} Marxist academic [[Steven Lukes]] most prominently publicly accused Chomsky of betraying his anarchist ideals and acting as an apologist for Cambodian leader [[Pol Pot]].{{sfn|Barsky|2007|p=98}} Herman said that the controversy "imposed a serious personal cost" on Chomsky,{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=187–189}} who considered the personal criticism less important than the evidence that "mainstream intelligentsia suppressed or justified the crimes of their own states".{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=190}} |

|||

===Edward Herman and the Faurisson affair: 1976–1980=== |

|||

[[File:Noam Chomsky (1977).jpg|thumb|left|Noam Chomsky (1977)]] |

|||

Throughout the late 1970s and 1980s, Chomsky's publications expanded and clarified his earlier work, addressing his critics and updating his grammatical theory.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=175}} His public talks often generated considerable controversy, particularly when he criticized actions of the Israeli government and military,{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=167, 170}} and his political views came under attack from right-wing and centrist figures, the most prominent of whom was [[Alan Dershowitz]]. Chomsky considered Dershowitz "a complete liar" and accused him of actively misrepresenting his position on issues.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=170–171}} Furthermore, during the early 1970s he had begun collaborating with [[Edward S. Herman]], who had also published critiques of the U.S. war in Vietnam.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=157}} Together they authored ''[[Counter-Revolutionary Violence: Bloodbaths in Fact & Propaganda]]'', a book which criticized U.S. military involvement in Southeast Asia and highlighted how mainstream media neglected to cover stories about these activities; the publisher [[Warner Modular]] initially accepted it, and it was published in 1973. However, Warner Modular's parent company, [[Warner Communications]], disapproved of the book's contents and ordered all copies to be destroyed.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=160–162|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=86}} |

|||

Chomsky had long publicly criticized [[Nazism]], and [[totalitarianism]] more generally, but his commitment to freedom of speech led him to defend the right of French historian [[Robert Faurisson]] to advocate a position widely characterized as [[Holocaust denial]]. Without Chomsky's knowledge, his plea for Faurisson's freedom of speech was published as the preface to the latter's 1980 book {{lang|fr|Mémoire en défense contre ceux qui m'accusent de falsifier l'histoire}}.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=179–180|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=61}} Chomsky was widely condemned for defending Faurisson,{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=185|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=61}} and France's mainstream press accused Chomsky of being a Holocaust denier himself, refusing to publish his rebuttals to their accusations.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=184}} Critiquing Chomsky's position, sociologist [[Werner Cohn]] later published an analysis of the affair titled ''Partners in Hate: Noam Chomsky and the Holocaust Deniers''.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=78}} The Faurisson affair had a lasting, damaging effect on Chomsky's career,{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=185}} especially in France.{{sfnm|Birnbaum|2010|Aeschimann|2010}} |

|||

While mainstream publishing options proved elusive, Chomsky found support from [[Michael Albert]]'s [[South End Press]], an activist-oriented publishing company.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=85}} |

|||

In 1979, Chomsky and Herman revised ''Counter-Revolutionary Violence'' and published it with South End Press as the two-volume ''[[The Political Economy of Human Rights]]''.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1p=187|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=86}} In this they compared U.S. media reactions to the [[Khmer Rouge rule of Cambodia|Cambodian genocide]] and the [[Indonesian occupation of East Timor]]. They argued that because Indonesia was a U.S. ally, U.S. media ignored the East Timorese situation while focusing on that in Cambodia, a U.S. enemy.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=187}} Taking a particular interest in the situation in East Timor, Chomsky testified on the subject in front of the [[United Nations]]' [[Special Committee on Decolonization]] in both 1978 and 1979, and attended a conference on the occupation held in [[Lisbon]] in 1979.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=103}} The following year, Steven Lukas authored an article for the ''[[Times Higher Education Supplement]]'' accusing Chomsky of betraying his anarchist ideals and acting as an apologist for Cambodian leader [[Pol Pot]]. Although Laura J. Summers and Robin Woodsworth Carlsen replied to the article, arguing that Lukas completely misunderstood Chomsky and Herman's work, Chomsky himself did not. The controversy damaged his reputation,{{sfn|Barsky|1997|pp=187–189}} and Chomsky maintains that his critics deliberately printed lies about him in order to defame him.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=190}} |

|||

=== Critique of propaganda and international affairs === |

|||

Although Chomsky had long publicly criticized [[Nazism]] and [[totalitarianism]] more generally, his commitment to [[freedom of speech]] led him to defend the right of French historian [[Robert Faurisson]] to advocate a position widely characterized as [[Holocaust denial]]. Without Chomsky's knowledge, his plea for the historian's freedom of speech was published as the preface to Faurisson's 1980 book ''Mémoire en défense contre ceux qui m'accusent de falsifier l'histoire''.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=179–180|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=61}} Chomsky was widely condemned for defending Faurisson,{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=185|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2p=61}} and France's mainstream press accused Chomsky of being a Holocaust denier himself, refusing to publish his rebuttals to their accusations.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=184}} Critiquing Chomsky's position, sociologist [[Werner Cohn]] later published an analysis of the affair titled ''Partners in Hate: Noam Chomsky and the Holocaust Deniers''.{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=78}} The Faurisson affair had a lasting, damaging effect on Chomsky's career,{{sfn|Barsky|1997|p=185}} and Chomsky did not visit France, where the translation of his political writings was delayed until the 2000s,<ref>{{cite news |last=Birnbaum|first=Jean | title=Chomsky à Paris : chronique d'un malentendu |

|||

{{external media |

|||

| url=http://www.lemonde.fr/livres/article/2010/06/03/chomsky-a-paris-chronique-d-un-malentendu_1367002_3260.html| work=Le Monde des Livres | date=3 June 2010 | accessdate=8 June 2010}}</ref> for almost thirty years following the affair.<ref>{{cite news |last=Aeschimann|first=Eric| title=Chomsky s'est exposé, il est donc une cible désignée | url=http://www.liberation.fr/monde/0101638536-chomsky-s-est-expose-il-est-donc-une-cible-designee | work=Liberátion | date=31 May 2010 | accessdate=8 June 2010}}</ref> |

|||

| video1 = [https://www.filmsforaction.org/watch/manufacturing-consent-noam-chomsky-and-the-media/ Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media], a 1992 documentary exploring Chomsky's work of the same name and its impact |

|||

}} |

|||

In 1985, during the [[Nicaraguan Contra War]]—in which the U.S. supported the [[Contras|contra militia]] against the [[Sandinista]] government—Chomsky traveled to [[Managua]] to meet with workers' organizations and refugees of the conflict, giving public lectures on politics and linguistics.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|pp=91, 92}} Many of these lectures were published in 1987 as ''On Power and Ideology: The Managua Lectures''.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=91}} In 1983 he published ''[[The Fateful Triangle]]'', which argued that the U.S. had continually used the [[Israeli–Palestinian conflict]] for its own ends.{{sfnm|1a1=Sperlich|1y=2006|1p=99|2a1=McGilvray|2y=2014|2p=13}} In 1988, Chomsky visited the [[Palestinian territories]] to witness the impact of Israeli occupation.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=98}} |

|||

Chomsky and Herman's ''[[Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media]]'' (1988) outlines their [[propaganda model]] for understanding mainstream media. Even in countries without official censorship, they argued, the news is censored through five filters that greatly influence both what and how news is presented.{{sfnm|1a1=Barsky|1y=1997|1pp=160, 202|2a1=Sperlich|2y=2006|2pp=127–134}} The book received [[Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media|a 1992 film adaptation]].{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=136}} In 1989, Chomsky published ''Necessary Illusions: Thought Control in Democratic Societies,'' in which he suggests that a worthwhile democracy requires that its citizens undertake intellectual self-defense against the media and elite intellectual culture that seeks to control them.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|pp=138–139}} By the 1980s, Chomsky's students had become prominent linguists who, in turn, expanded and revised his linguistic theories.{{sfn|Sperlich|2006|p=53}} |

|||

===Reaganite era and work on the media: 1980–89=== |

|||

[[File:Noam Chomsky Toronto 2011.jpg|thumb|left|Chomsky speaking in support of the [[Occupy movement]] in 2011]] |

|||