Philippines: Difference between revisions

Nonoyborbun (talk | contribs) |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Country in Southeast Asia}} |

|||

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

|||

{{redirect|Philippine|the town in the Netherlands|Philippine, Netherlands}} |

|||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

|||

{{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} |

|||

{{Coord|13|N|122|E|display=title}} |

|||

{{Good article}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=May 2017}} |

|||

{{Use Philippine English|date= |

{{Use Philippine English|date=February 2022}} |

||

{{Use mdy dates|date=October 2024}} |

|||

{{Infobox country |

{{Infobox country |

||

|conventional_long_name = Republic of the Philippines |

| conventional_long_name = Republic of the Philippines |

||

|common_name = the Philippines |

| common_name = the Philippines |

||

|native_name = |

| native_name = {{native name|fil|Republika ng Pilipinas}} |

||

| image_flag = Flag of the Philippines.svg |

|||

:*[[Aklanon language|Aklanon]]: ''Republika it Pilipinas'' |

|||

| flag_size = 130 |

|||

:*[[Bikol languages|Bikol]]: ''Republika kan Filipinas'' |

|||

| flag_type = [[Flag of the Philippines|Flag]] |

|||

:*{{lang-ceb|Republika sa Pilipinas}} |

|||

| image_coat = Coat of arms of the Philippines.svg |

|||

:*[[Chavacano]]: ''República de Filipinas'' |

|||

| symbol_type = [[Coat of arms of the Philippines|Coat of arms]]{{efn|Although the Flag and Heraldic Code of the Philippines (Republic Act 8491) passed in 1998 defined modifications to the coat of arms that removed the colonial charges, a referendum legally required to ratify the changes has not yet been called.}} |

|||

:*[[Hiligaynon language|Hiligaynon]]: ''Republika sang Filipinas'' |

|||

| national_motto = <br />{{lang|fil|[[Maka-Diyos, Maka-tao, Makakalikasan at Makabansa]]}}<ref>{{cite PH act |chamber=RA |number=8491 |title=Flag and Heraldic Code of the Philippines |date=February 12, 1998 |url=https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1998/02/12/republic-act-no-8491/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170525084350/https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1998/02/12/republic-act-no-8491/ |archive-date=May 25, 2017 |access-date=March 8, 2014 |publisher=[[Official Gazette (Philippines)|Official Gazette of the Philippines]] |location=Metro Manila, Philippines}}</ref><br />"For God, People, Nature, and Country" |

|||

:*[[Ibanag language|Ibanag]]: ''Republika nat Filipinas'' |

|||

| national_anthem = "{{lang|fil|[[Lupang Hinirang]]}}"<br />"Chosen Land"{{parabr}}{{center|[[File:Philippine National Anthem, the Lupang Hinirang Tenor Solo.ogg]]}} |

|||

:*[[Ilocano language|Ilocano]]: ''Republika ti Filipinas'' |

|||

| image_map = {{Switcher|[[File:PHL orthographic.svg|frameless]]|Show globe|[[File:Location Philippines ASEAN.svg|upright=1.15|frameless]]|Show map of ASEAN|default=1}} |

|||

:*[[Ivatan language|Ivatan]]: ''Republika nu Filipinas'' |

|||

| map_caption = {{map caption |location_color=green |region=[[ASEAN]] |region_color=dark grey |legend=Location Philippines ASEAN.svg}} |

|||

:*[[Kapampangan language|Kapampangan]]: ''Republika ning Filipinas'' |

|||

| capital = [[Manila]] (''de jure'')<br />[[Metro Manila]]{{efn|name=a|While [[Manila]] is designated as [[Capital of the Philippines|the nation's capital]], the [[seat of government]] is the ''National Capital Region'', commonly known as "[[Metro Manila]]", of which the city of Manila is a part.<ref>{{Cite PH act |title=Establishing Manila as the Capital of the Philippines and as the Permanent Seat of the National Government |chamber=PD |number=940, s. 1976 |date=May 29, 1976 |url=https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1976/05/29/presidential-decree-no-940-s-1976/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170525084430/https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1976/05/29/presidential-decree-no-940-s-1976/ |archive-date=May 25, 2017 |access-date=April 4, 2015 |publisher=[[Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines]] |location=Manila, Philippines}}</ref><ref>{{#invoke:cite web||title=Quezon City Local Government – Background |url=https://quezoncity.gov.ph/index.php/about-the-city-government/background |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200820074250/https://quezoncity.gov.ph/index.php/about-the-city-government/background |archive-date=August 20, 2020 |access-date=August 25, 2020 |publisher=Quezon City Local Government}}</ref> Many national government institutions are located on various parts of Metro Manila, aside from [[Malacañang Palace]] and other institutions/agencies that are located within the Manila capital city.}} (''de facto'') |

|||

:*[[Kinaray-a language|Kinaray-a]]: ''Republika kang Pilipinas'' |

|||

| largest_city = [[Quezon City]]<!--Although [[Davao City]] has the largest land area, the article on [[largest city]] says we should refer to the most populous city, which, {{As of|2006|lc=y}}, is [[Quezon City]]. See the discussion page for more information. Changing this information without citation would be reverted.--> |

|||

:*[[Maranao language|Maranao]]: ''Republika san Pilipinas'' |

|||

| official_languages = {{hlist|[[Filipino language|Filipino]]|[[Philippine English|English]]}} |

|||

:*[[Pangasinan language|Pangansinan]]: ''Republika na Filipinas'' |

|||

| recognized_regional_languages = [[Languages of the Philippines|19 languages]]<ref name="GMA-DepEd-7-Languages" /> |

|||

:*[[Sambal language|Sambal]]: ''Republika nin Pilipinas'' |

|||

| languages_type = National [[sign language]] |

|||

:*[[Surigaonon language|Surigaonon]]: ''Republika nan Pilipinas'' |

|||

| languages = [[Filipino Sign Language]] |

|||

:*[[Waray language|Waray]]: ''Republika han Pilipinas'' |

|||

| languages_sub = yes |

|||

| languages2_type = Other recognized languages{{efn|name=b|As per the 1987 Constitution: "Spanish and Arabic shall be promoted on a voluntary and optional basis."<ref name="GovPH-OfficialLanguage" />}} |

|||

In the recognized optional languages of the Philippines: |

|||

| languages2 = [[Philippine Spanish|Spanish]] and [[Arabic]] |

|||

:*{{lang-es|República de Filipinas}} |

|||

<!--Do not remove Spanish and Arabic from the languages list as it is recognized as an optional language in the 1987 Constitution of the Philippines-->| languages2_sub = yes |

|||

:*{{lang-ar|جمهورية الفلبين|Jumhuriat Alfalabin}} |

|||

| ethnic_groups = {{#invoke:list|unbulleted |

|||

| 26.0% [[Tagalog people|Tagalog]] |

|||

| 14.3% [[Visayans|Bisaya]] |

|||

| 8.0% [[Ilocano people|Ilocano]] |

|||

| 8.0% [[Cebuano people|Cebuano]] |

|||

| 7.9% [[Hiligaynon people|Ilonggo]] |

|||

| 6.5% [[Bicolano people|Bicolano]] |

|||

| 20.3% [[Ethnic groups in the Philippines|other]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

| ethnic_groups_year = 2020<ref name="PSAGovPH-Ethnicity-2020Census">{{Cite press release |title=Ethnicity in the Philippines (2020 Census of Population and Housing) |url=https://www.psa.gov.ph/statistics/population-and-housing/node/1684059978 |access-date=May 11, 2024 |website=[[Philippine Statistics Authority]] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230906202953/https://www.psa.gov.ph/statistics/population-and-housing/node/1684059978 |archive-date=September 6, 2023}}</ref><!-- using figures for 2010 given in the cited source--><!--parameter ethnic_groups_ref not supported by the infobox--> |

|||

|image_flag = Flag of the Philippines.svg |

|||

| demonym = [[Filipinos|Filipino]]<br />(''neutral'')<br />Filipina<br />(''feminine'')<br /> |

|||

|image_coat = Coat of Arms of the Philippines.svg |

|||

[[Pinoy]]<br />(''colloquial neutral'')<br />Pinay<br />(''colloquial feminine'')<br /> |

|||

|other_symbol = <div style="padding:0.3em;">[[File:Seal of the Philippines.svg|80px|link=Great Seal of the Philippines]]</div>{{native phrase|fil|[[Coat of arms of the Philippines#Great Seal|Dakilang Sagisag ng Pilipinas]]|nolink=on}}<br/>{{small|Great Seal of the Philippines}} |

|||

Philippine<br />(''adjective for certain common nouns'') <!-- "Philippine" is a demonym as it is used to identify natives or residents of a certain or specific place that are derived from the place name Philippines, i.e. Philippine-American War -- refer to Oxford definition of demonym(s). --> |

|||

|other_symbol_type = [[Coat of arms of the Philippines#Great Seal|Great Seal]] |

|||

| government_type = Unitary [[presidential republic]] |

|||

|national_motto = <br/>"[[Maka-Diyos, Maka-Tao, Makakalikasan at Makabansa]]"<ref name=ra8491>{{cite web|title=Republic act no. 8491 |url=http://www.gov.ph/1998/02/12/republic-act-no-8491/ |publisher=Republic of the Philippines |accessdate=March 8, 2014 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20140308050740/http://www.gov.ph/1998/02/12/republic-act-no-8491/ |archivedate=March 8, 2014 |df= }}</ref><br/>{{small|"For God, People, Nature, and Country"}} |

|||

| leader_title1 = [[President of the Philippines|President]] |

|||

|national_anthem = ''[[Lupang Hinirang]]''{{brk}}{{small|''Chosen Land''}}<br/><center>[[File:Lupang Hinirang instrumental.ogg]]</center> |

|||

| leader_name1 = [[Bongbong Marcos]]<!-- Article is at Bongbong Marcos, do NOT use Ferdinand Marcos Jr. unless the article itself is renamed. --> |

|||

|image_map = PHL orthographic.svg |

|||

| leader_title2 = [[Vice President of the Philippines|Vice President]] |

|||

|image_map2 = |

|||

| leader_name2 = [[Sara Duterte]]<!-- Article is at Sara Duterte, do NOT use Sara Duterte-Carpio unless the article itself is renamed. --> |

|||

|capital = [[Manila]]{{ref|a|a}} |

|||

| leader_title3 = [[President of the Senate of the Philippines|Senate President]] |

|||

|coordinates = {{Coord|14|35|N|120|58|E|type:city}} |

|||

| leader_name3 = [[Francis Escudero]]<!-- Article is at Francis Escudero, do NOT use Chiz Escudero unless the article itself is renamed. --> |

|||

|largest_city = [[Quezon City]]<br/>{{small|{{coord|14|38|N|121|02|E|display=inline}}}} <!--Although [[Davao City]] has the largest land area, the article on [[largest city]] says we should refer to the most populous city, which, {{As of|2006|lc=y}}, is [[Quezon City]]. See the discussion page for more information. Changing this information without citation would be reverted.--> |

|||

| leader_title4 = [[Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines|House Speaker]] |

|||

|official_languages = {{hlist |[[Filipino language|Filipino]] |[[Philippine English|English]]}} |

|||

| leader_name4 = [[Martin Romualdez]]<!-- Article is at Martin Romualdez, do NOT use Ferdinand Martin Romualdez unless the article itself is renamed. --> |

|||

|recognized_regional_languages = {{collapsible list |

|||

| leader_title5 = [[Chief Justice of the Philippines|Chief Justice]] |

|||

| leader_name5 = [[Alexander Gesmundo]] |

|||

|[[Aklanon language|Aklanon]] |

|||

| legislature = [[Congress of the Philippines|Congress]] |

|||

|[[Bikol languages|Bikol]] |

|||

| upper_house = [[Senate of the Philippines|Senate]] |

|||

|[[Cebuano language|Cebuano]] |

|||

| lower_house = [[House of Representatives of the Philippines|House of Representatives]] |

|||

|[[Chavacano]] |

|||

| sovereignty_type = [[Sovereignty of the Philippines|Independence]] |

|||

|[[Hiligaynon language|Hiligaynon]] |

|||

| sovereignty_note = from [[Spain]] and the [[United States]] |

|||

|[[Ibanag language|Ibanag]] |

|||

| established_event1 = [[Philippine Declaration of Independence|Declaration]] |

|||

|[[Ilocano language|Ilocano]] |

|||

| established_date1 = June 12, 1898 |

|||

|[[Ivatan language|Ivatan]] |

|||

| established_event2 = [[Treaty of Paris (1898)|Cession]] |

|||

|[[Kapampangan language|Kapampangan]] |

|||

| established_date2 = April 11, 1899 |

|||

|[[Kinaray-a language|Kinaray-a]] |

|||

| established_event3 = [[Commonwealth of the Philippines|Self-government]] |

|||

|[[Maguindanao language|Maguindanao]] |

|||

| established_date3 = November 15, 1935 |

|||

|[[Maranao language|Maranao]] |

|||

| established_event4 = [[Treaty of Manila (1946)|Recognized]] |

|||

|[[Pangasinan language|Pangasinan]] |

|||

| established_date4 = July 4, 1946 |

|||

|[[Sambal language|Sambal]] |

|||

| established_event5 = [[Constitution of the Philippines|Constitution]] |

|||

|[[Surigaonon language|Surigaonon]] |

|||

| established_date5 = February 2, 1987 |

|||

|[[Tagalog language|Tagalog]] |

|||

| area_km2 = 300000<ref name="Philippines country profile">{{cite news|title=Philippines country profile|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-67765684|website=[[BBC News]]|date=December 19, 2023 |access-date=January 10, 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231219164940/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-67765684|archive-date=December 19, 2023}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/philippines/#geography|title=Philippines|date=February 27, 2023|publisher=Central Intelligence Agency|via=CIA.gov|access-date=February 24, 2023|archive-date=January 10, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210110072816/https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/philippines#geography|url-status=live}}</ref>{{efn|name=land-area}} |

|||

|[[Taūsug language|Taūsug]] |

|||

| area_footnote = |

|||

|[[Waray language|Waray]] |

|||

| area_link = Geography of the Philippines |

|||

|[[Yakan language|Yakan]] |

|||

| area_label = Total |

|||

}} |

|||

| area_rank = 72nd |

|||

|languages_type = Optional languages{{ref|b|b}} |

|||

| percent_water = 0.61<ref name="CIAWorldFactBook">{{#invoke:cite web||date=June 7, 2023 |title=Philippines |url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/philippines/ |access-date=June 19, 2023 |website=[[The World Factbook]] |publisher=[[Central Intelligence Agency]]}}</ref> (inland waters) |

|||

|languages = {{hlist |[[Philippine Spanish|Spanish]] |[[Arabic language|Arabic]]}} |

|||

<!-- |

|||

|ethnic_groups = {{unbulleted list |

|||

| area_label2 = [[List of countries and dependencies by area|Total land area]] |

|||

<!-- per page 27 of the supporting source cited (Cebuanos, Ilongos, and Waray are covered by the Visayan grouping -- page 34 of the PDF) --> |

|||

| area_data2 = {{convert|319954|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}} |

|||

|{{#expr:100 * (10539816+9125637+7773655+3660645) / 92097978 round 1}}% [[Visayans|Visayan]] |

|||

--> <!-- hidden since no reliable source is provided -->| population_estimate = {{IncreaseNeutral}} 114,163,719<ref>{{cite web |url = https://psa.gov.ph/statistics/census/projected-population |title = Population Projection Statistics |date = March 28, 2021 |website = psa.gov.ph |access-date = November 15, 2023 |archive-date = December 26, 2023 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20231226235925/https://psa.gov.ph/statistics/census/projected-population |url-status = live }}</ref> |

|||

|{{#expr:100 * 25512089 / 92097978 round 1}}% [[Tagalog people|Tagalog]] |

|||

| population_estimate_year = 2024 |

|||

|{{#expr:100 * 8987941 / 92097978 round 1}}% [[Ilocano people|Ilocano]] |

|||

| population_estimate_rank = 12th |

|||

|{{#expr:100 * 6299283 / 92097978 round 1}}% [[Bicolano people|Bicolano]] |

|||

| population_census_year = 2020 |

|||

|{{#expr:100 * 4737123 / 92097978 round 1}}% [[Moro people|Moro]] |

|||

| population_census = {{IncreaseNeutral}} 109,035,343<ref name="PSAGovPH-2020Census">{{Cite press release|last=Mapa|first=Dennis S.|author-link1=Dennis Mapa|date=July 7, 2021|title=2020 Census of Population and Housing (2020 CPH) Population Counts Declared Official by the President|url=https://psa.gov.ph/content/2020-census-population-and-housing-2020-cph-population-counts-declared-official-president|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210707104119/https://psa.gov.ph/content/2020-census-population-and-housing-2020-cph-population-counts-declared-official-president|archive-date=July 7, 2021 |publisher=[[Philippine Statistics Authority]]}}</ref> |

|||

|{{#expr:100 * 2897239 / 92097978 round 1}}% [[Kapampangan people|Kapampangan]] |

|||

| population_density_km2 = 363.45 |

|||

|{{#expr:100 * 1586349 / 92097978 round 1}}% [[Igorot people|Igorot]] |

|||

| population_density_sq_mi = {{Data/popdens|Philippines|comma|areaunit=sqmi}}<!--Do not remove per [[WP:MOSNUM]]--> |

|||

|{{#expr:100 * 1274895 / 92097978 round 1}}% [[Pangasinense people|Pangasinense]] |

|||

| population_density_rank = 36th |

|||

|{{#expr:100 * 1146250 / 92097978 round 1}}% [[Chinese Filipino|Chinese]] |

|||

| GDP_PPP = {{increase}} $1.392 trillion<ref name="IMFWEO.PH">{{cite web |url=https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/April/weo-report?c=566,&s=NGDPD,PPPGDP,NGDPDPC,PPPPC,&sy=2022&ey=2029&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1 |title=World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024 Edition. (Philippines) |publisher=[[International Monetary Fund]] |date=April 16, 2024 |access-date=April 17, 2024 |archive-date=April 16, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240416221054/https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/April/weo-report?c=566,&s=NGDPD,PPPGDP,NGDPDPC,PPPPC,&sy=2022&ey=2029&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

|{{#expr:100 * 1054859 / 92097978 round 1}}% [[Zamboangueño people|Zamboangueño]] |

|||

| GDP_PPP_year = 2024 |

|||

|{{#expr:100 * (92097978-(10539816+9125637+7773655+3660645+213150)−25512089-8987941-6299283-4737123−2897239-1274895-1146250−1586349−1054859−1000000)/ 92097978 round 1}}% [[Ethnic groups in the Philippines|others]] |

|||

| GDP_PPP_rank = 28th |

|||

}} |

|||

| GDP_PPP_per_capita = {{increase}} $12,192<ref name="IMFWEO.PH" /> |

|||

|ethnic_groups_year = 2010{{Sfn|Philippine Statistics Authority|2014|pp=29–34}} |

|||

| GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = 116th |

|||

|demonym = [[Filipinos|Filipino (''masculine'')<br/>Filipina (''feminine'')]]<br/> |

|||

| GDP_nominal = {{increase}} $471.516 billion<ref name="IMFWEO.PH" /> |

|||

[[Pinoy|Pinoy (''colloquial masculine'')<br/>Pinay (''colloquial feminine'')]]<br/> |

|||

| GDP_nominal_year = 2024 |

|||

[[Filipinos|Philippine (''English'')]] <!-- "Philippine" is a demonym as it is used to identify natives or residents of a certain or specific place that are derived from the place name Philippines, i.e. Philippine-American War -- refer to Oxford definition of demonym(s). --> |

|||

| GDP_nominal_rank = 32nd |

|||

|government_type = [[Unitary state|Unitary]] [[Presidential system|presidential]] [[constitutional republic]] |

|||

| GDP_nominal_per_capita = {{increase}} $4,130<ref name="IMFWEO.PH" /> |

|||

|leader_title1 = [[President of the Philippines|President]] |

|||

| GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = 124th |

|||

|leader_name1 = [[Rodrigo Duterte]] |

|||

| |

| Gini = 41.2 <!--number only--> |

||

| |

| Gini_year = 2021 |

||

| Gini_change = decrease <!--increase/decrease/steady--> |

|||

|leader_title3 = [[President of the Senate of the Philippines|Senate President]] |

|||

| Gini_ref = <ref>{{Cite press release |title=Highlights of the Preliminary Results of the 2021 Annual Family Income and Expenditure Survey |publisher=[[Philippine Statistics Authority|PSA]] |url=https://psa.gov.ph/content/highlights-preliminary-results-2021-annual-family-income-and-expenditure-survey |access-date=August 15, 2022 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230516030556/https://psa.gov.ph/content/highlights-preliminary-results-2021-annual-family-income-and-expenditure-survey |archive-date=May 16, 2023}}</ref> |

|||

|leader_name3 = [[Aquilino Pimentel III]] |

|||

| |

| HDI = 0.710 <!--number only--> |

||

| HDI_year = 2022 <!-- Please use the year to which the data refers, not the publication year--> |

|||

|leader_name4 = [[Pantaleon Alvarez]] |

|||

| HDI_change = increase <!--increase/decrease/steady--> |

|||

|leader_title5 = [[Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines|Chief Justice]] |

|||

| HDI_ref = <ref name="UNHDR">{{cite web|url=https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2023-24reporten.pdf|title=Human Development Report 2023/24|language=en|publisher=[[United Nations Development Programme]]|date=March 13, 2024|page=289|access-date=March 13, 2024|archive-date=March 13, 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240313164319/https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2023-24reporten.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

|leader_name5 = [[Maria Lourdes Sereno]] |

|||

| |

| HDI_rank = 113th |

||

| |

| currency = [[Philippine peso]] ([[Philippine peso sign|₱]]) |

||

| currency_code = PHP |

|||

|lower_house = [[House of Representatives of the Philippines|House of Representatives]] |

|||

| |

| time_zone = [[Philippine Standard Time|PhST]] |

||

| |

| utc_offset = +8 |

||

| date_format = MM/DD/YYYY<br />DD/MM/YYYY{{efn|See [[Date and time notation in the Philippines]].}} |

|||

|established_event1 = [[Philippine Declaration of Independence|Independence from Spain declared]] |

|||

| drives_on = right<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gX6aAAAAIAAJ |title=Philippine Yearbook |date=1978 |publisher=[[National Economic and Development Authority]], [[Philippine Statistics Authority|National Census and Statistics Office]] |edition=1978 |location=Manila, Philippines |page=[https://books.google.com/books?id=gX6aAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA716 716] |language=en |access-date=February 18, 2023 |archive-date=March 6, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230306102626/https://books.google.com/books?id=gX6aAAAAIAAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

|established_date1 = June 12, 1898 |

|||

| calling_code = [[Telephone numbers in the Philippines|+63]] |

|||

|established_event2 = [[Treaty of Paris (1898)|Treaty of Paris (1898) / Spanish Cession]]{{ref|c|c}} |

|||

| |

| cctld = [[.ph]] |

||

| religion = {{#invoke:list|unbulleted|item_style=white-space:nowrap; |

|||

|established_event3 = [[Malolos Constitution]] / [[First Philippine Republic]] {{ref|e|e}} |

|||

| |

|||

|established_date3 = January 21, 1899 |

|||

{{Tree list}} |

|||

|established_event4 = [[Tydings–McDuffie Act]] |

|||

* 85.3% [[Christianity in the Philippines|Christianity]] <!--note that the release by the PSA sums up all statistics to 99.9%--> |

|||

|established_date4 = March 24, 1934 |

|||

** 78.8% [[Catholic Church in the Philippines|Catholicism]]{{efn|name=Catholic-2020Census|Excludes [[Catholic Charismatic Renewal|Catholic Charismatic]]s numbering 74,096 persons (0.07% of the Philippine household population in 2020)<ref name="PSAGovPH-Religion-2020Census" />}} |

|||

|established_event5 = [[Commonwealth of the Philippines]] |

|||

** 6.5% other [[Religion in the Philippines#Christianity|Christian]] |

|||

|established_date5 = May 14, 1935 |

|||

{{Tree list/end}} |

|||

|established_event6 = [[Treaty of Manila (1946)|Treaty of Manila / Independence from |

|||

|6.4% [[Islam in the Philippines|Islam]] |

|||

United States]] {{ref|d|d}} |

|||

|8.2% [[Religion in the Philippines#Other religions|other]] / [[Irreligion in the Philippines|none]] |

|||

|established_date6 = July 4, 1946 |

|||

}} |

|||

|established_event7 = [[Constitution of the Philippines|Current constitution]] |

|||

| |

| religion_year = 2020 |

||

| religion_ref = <ref name="PSAGovPH-Religion-2020Census">{{Cite press release |last=Mapa |first=Dennis |author-link1=Dennis Mapa |date=February 21, 2023 |title=Religious Affiliation in the Philippines (2020 Census of Population and Housing) |url=https://www.psa.gov.ph/system/files/phcd/1_Press%20Release%20on%20Religious%20Affiliation_RML_01272023_FJRA_PMMJ_CRD-signed_0.pdf |url-status=live |access-date=May 11, 2024 |work=[[Philippine Statistics Authority]] |page=2 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230812114943/https://www.psa.gov.ph/system/files/phcd/1_Press%20Release%20on%20Religious%20Affiliation_RML_01272023_FJRA_PMMJ_CRD-signed_0.pdf |archive-date=August 12, 2023}}</ref> |

|||

|area_km2 = {{formatnum:{{data Philippines|pst2|total area}}}} |

|||

|area_label = Total |

|||

|area_rank = 72nd |

|||

<!--|area_magnitude = 1 E11--> |

|||

|area_sq_mi = {{convert|{{data Philippines|pst2|total area}}|km2|sqmi|0|disp=output number only}} <!--Do not remove per [[WP:MOSNUM]]--> |

|||

|percent_water = 0.61<ref name=CIAfactbook>{{cite web|url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rp.html |publisher=Central Intelligence Agency |title=East & Southeast Asia :: Philippines |work=The World Factbook |location=Washington, D.C.: Author |date=October 28, 2009 |accessdate=November 7, 2009 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150719222229/https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rp.html |archivedate=July 19, 2015 |df= }}</ref> {{small|(inland waters)}} |

|||

|area_label2 = [[Land area|Land]] |

|||

|area_data2 = {{formatnum:{{data Philippines|pst2|land area}}}} km{{sup|2}}<br/>{{convert|{{data Philippines|pst2|land area}}|km2|sqmi|disp=output number only}} sq mi |

|||

|population_estimate = |

|||

|population_census = 100,981,437<ref>{{cite web|url=http://psa.gov.ph/content/highlights-philippine-population-2015-census-population|title=Highlights of the Philippine Population 2015 Census of Population – Philippine Statistics Authority|publisher=|accessdate=October 5, 2016}}</ref> |

|||

|population_estimate_year = |

|||

|population_census_year = {{Data Philippines|pst2|popbaseyear}} |

|||

|population_census_rank = 13th |

|||

|population_density_km2 = 336.60 |

|||

|population_density_sq_mi = {{Data/popdens|Philippines|comma|areaunit=sqmi}}<!--Do not remove per [[WP:MOSNUM]]--> |

|||

|population_density_rank = 37th |

|||

|GDP_PPP = $878.980 billion<ref name = "imf2">{{cite web | url =http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=59&pr.y=10&sy=2014&ey=2021&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=566&s=NGDPD%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPGDP%2CPPPPC&grp=0&a= | title = Philippines | work = World Economic Outlook | publisher = International Monetary Fund | date = October 2016}}</ref> |

|||

|GDP_PPP_year = 2017 |

|||

|GDP_PPP_rank = 29th |

|||

|GDP_PPP_per_capita = $8,223<ref name=imf2/> |

|||

|GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = 118th |

|||

|GDP_nominal = $348.593 billion<ref name=imf2/> |

|||

|GDP_nominal_year = 2017 |

|||

|GDP_nominal_rank = 36th |

|||

|GDP_nominal_per_capita = $3,280<ref name=imf2/> |

|||

|GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = 124th |

|||

|Gini = 43.0 <!--number only--> |

|||

|Gini_year = 2012 |

|||

|Gini_change = 42decrease <!--increase/decrease/steady--> |

|||

|Gini_ref = <ref name="wb-gini">{{cite web |url=http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI/ |title=Gini Index |publisher=World Bank |accessdate=March 2, 2011}}</ref> |

|||

|Gini_rank = 44th |

|||

|HDI = 0.682 <!--number only--> |

|||

|HDI_year = 2015 <!-- Please use the year to which the data refers, not the publication year--> |

|||

|HDI_change = increase <!--increase/decrease/steady--> |

|||

|HDI_ref = <ref name="HDI">{{cite web |url=http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2016_human_development_report.pdf |title=2016 Human Development Report |year=2016 |accessdate=March 21, 2017 |publisher=United Nations Development Programme}}</ref> |

|||

|HDI_rank = 116th |

|||

|currency = {{nowrap|[[Philippine peso|Peso]] (Filipino: {{lang|fil|''piso''}}) (₱)}} |

|||

|currency_code = PHP |

|||

|time_zone = [[Philippine Standard Time|PST]] |

|||

|utc_offset = +8 |

|||

|utc_offset_DST = +8 |

|||

|time_zone_DST = not observed |

|||

|date_format = {{unbulleted list |mm-dd-yyyy|dd-mm-yyyy ([[Anno Domini|AD]])}} |

|||

|drives_on = right<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.brianlucas.ca/roadside/ |title=Which side of the road do they drive on? |author=Lucas, Brian |date=August 2005 |accessdate=February 22, 2009 |publisher=}}</ref> |

|||

|calling_code = [[+63]] |

|||

|cctld = [[.ph]] |

|||

|footnote_a = {{note|a}} While Manila proper is designated as the nation's capital, the whole of [[Metro Manila|National Capital Region]] is designated as [[seat of government]], hence the name of a region. This is because it has many government agencies, corporations or companies, and institutions aside from Malacanang Palace in the said capital city.<ref>{{cite web|title=Presidential Decree No. 940, s. 1976 |url=http://www.gov.ph/1976/05/29/presidential-decree-no-940-s-1976/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/19760529010101/http://www.gov.ph/1976/05/29/presidential-decree-no-940-s-1976/ |publisher=Malacanang |accessdate=April 4, 2015 |archivedate=May 29, 1976 |dead-url=yes |location=Manila |df= }}</ref> |

|||

|footnote_b = {{note|b}} The 1987 Philippine constitution specifies "Spanish and Arabic shall be promoted on a voluntary and optional basis."<ref name=OfficialLang/> |

|||

|footnote_c = {{note|c}} Philippine revolutionaries [[Philippine Declaration of Independence|declared independence]] from Spain on June 12, 1898, but Spain ceded the islands to the United States for $20 million in the [[Treaty of Paris (1898)|Treaty of Paris]] on December 10, 1898 which eventually led to the [[Philippine–American War]]. |

|||

|footnote_d = {{note|d}} The United States of America recognized the independence of the Philippines on July 4, 1946, through the [[Treaty of Manila (1946)|Treaty of Manila]].<ref>{{Citation|url=http://untreaty.un.org/unts/1_60000/1/6/00000254.pdf|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110723021900/http://untreaty.un.org/unts/1_60000/1/6/00000254.pdf|archivedate=July 23, 2011|format=PDF|title=Treaty of General Relations Between the United States of America and the Republic of the Philippines. Signed at Manila, on 4 July 1946|publisher=United Nations|accessdate=December 10, 2007}}</ref> This date was chosen because it corresponds to the U.S. [[Independence Day (United States)|Independence Day]], which was observed in the Philippines as '''''[[Independence Day (Philippines)|Independence Day]]''''' until May 12, 1962, when [[President of the Philippines|President]] [[Diosdado Macapagal]] issued Presidential Proclamation No. 28, shifting it to June 12, the date of [[Emilio Aguinaldo]]'s proclamation.<ref>{{cite web|title=Republic of the Philippines Independence Day|url=http://m.state.gov/md243684.htm|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150612010101/http://m.state.gov/md243684.htm|publisher=[[United States State Department]]|accessdate=July 30, 2015|archivedate=June 12, 2015|dead-url=yes|location=Washington, D.C.}}</ref> |

|||

|footnote_e = {{note|e}} In accordance with article 11 of the Revolutionary Government Decree of June 23, 1898, the [[Malolos Congress]] selected a commission to draw up a draft [[constitution]] on September 17, 1898. The commission was composed of Hipólito Magsalin, Basilio Teodoro, José Albert, [[Joaquin Gonzalez (politician)|Joaquín González]], [[Gregorio S. Araneta|Gregorio Araneta]], Pablo Ocampo, Aguedo Velarde, Higinio Benitez, [[Tomas del Rosario|Tomás del Rosario]], [[Jose Alejandrino|José Alejandrino]], Alberto Barretto, José Ma. de la Viña, José Luna, [[Antonio Luna]], Mariano Abella, Juan Manday, [[Felipe Calderón y Roca|Felipe Calderón]], [[Arsenio Cruz-Herrera|Arsenio Cruz]] and Felipe Buencamino.<ref>{{cite book|last=Calderón|first=Felipe|title=Mis memorias sobre la revolución filipina: Segunda etapa, (1898 á 1901). |year=1907|publisher=Imp. de El Renacimiento|location=Manila|pages=234, 235; appendix, pp. 5–10.}}</ref> They were all wealthy and well educated.<ref name=LOCPhil>{{cite book|author=Dolan, Federal Research Division, Library of Congress|editor=Ronald E.|title=Philippines, a country study|date=1983|publisher=Federal Research Division, Library of Congress|location=Washington, D.C.|isbn=0844407488|edition=4th}}</ref> |

|||

|religion = {{ublist |item_style=white-space:nowrap; |92% [[Christianity in the Philippines|Christianity]] |5.57% [[Islam in the Philippines|Islam]] |2.43% others<ref name="PSA-2015PSY" /> }} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

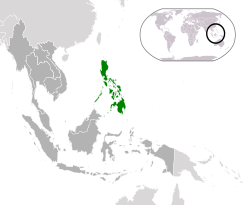

The '''Philippines''',{{efn|{{IPAc-en|audio=En-us-Philippines.ogg|ˈ|f|i|l|ᵻ|p|iː|n|z}}; {{langx|fil|Pilipinas}}, {{IPA|tl|pɪ.lɪˈpiː.nɐs}}}} officially the '''Republic of the Philippines''',{{efn|{{langx|fil|Republika ng Pilipinas|links=no}}.<br />In the recognized regional [[languages of the Philippines]]: |

|||

The '''Philippines''' ({{IPAc-en|audio=En-us-Philippines.ogg|ˈ|f|ɪ|l|ᵻ|p|iː|n|z}}; {{lang-fil|Pilipinas}} {{IPA-tl|ˌpɪlɪˈpinɐs|}} or ''Filipinas'' {{IPA-tl|ˌfɪlɪˈpinɐs|}}), officially the '''Republic of the Philippines''' (Filipino: ''Republika ng Pilipinas''), is a [[sovereign state|sovereign]] [[island country]] in [[Southeast Asia]] situated in the western Pacific Ocean. It consists of about 7,641 islands<ref>{{cite news|url=http://cnnphilippines.com/videos/2016/02/20/More-islands-more-fun-in-PH.html|title=More islands, more fun in PH|publisher=''[[CNN Philippines]]''|date=February 20, 2016|accessdate=February 20, 2016}}</ref> that are categorized broadly under three main geographical divisions from north to south: [[Luzon]], [[Visayas]], and [[Mindanao]]. The capital city of the Philippines is [[Manila]] and the most populous city is [[Quezon City]], both part of [[Metro Manila]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mmda.gov.ph/|title=Metro Manila Official Website|work=Metro Manila Development Authority|accessdate=December 17, 2015}}</ref> Bounded by the [[South China Sea]] on the west, the [[Philippine Sea]] on the east and the [[Celebes Sea]] on the southwest, the Philippines shares maritime borders with [[Taiwan]] to the north, [[Vietnam]] to the west, [[Palau]] to the east and [[Malaysia]] and [[Indonesia]] to the south. |

|||

{{div col|colwidth=30em}} |

|||

* {{langx|akl|Republika it Pilipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|bik|Republika kan Filipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|ceb|Republika sa Pilipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|cbk|República de Filipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|hil|Republika sang Filipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|ibg|Republika nat Filipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|ilo|Republika ti Filipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|ivv|Republika nu Filipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|pam|Republika ning Filipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|krj|Republika kang Pilipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|mdh|Republika nu Pilipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|mrw|Republika a Pilipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|pag|Republika na Filipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|xsb|Republika nin Pilipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|sgd|Republika nan Pilipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|tl|Republika ng Pilipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|tsg|Republika sin Pilipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|war|Republika han Pilipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|yka|Republika si Pilipinas}} |

|||

{{div col end}} |

|||

In the recognized optional languages of the Philippines: |

|||

{{div col|colwidth=30em}} |

|||

* {{langx|es|República de las Filipinas}} |

|||

* {{langx|ar|جمهورية الفلبين|Jumhūriyyat al-Filibbīn}} |

|||

{{div col end}}}} is an [[Archipelagic state|archipelagic country]] in [[Southeast Asia]]. In the western [[Pacific Ocean]], it consists of [[List of islands of the Philippines|7,641 islands]], with a total area of roughly 300,000 square kilometers, which are broadly categorized in [[Island groups of the Philippines|three main geographical divisions]] from north to south: [[Luzon]], [[Visayas]], and [[Mindanao]]. The Philippines is bounded by the [[South China Sea]] to the west, the [[Philippine Sea]] to the east, and the [[Celebes Sea]] to the south. It shares [[maritime border]]s with [[Taiwan]] to the north, [[Japan]] to the northeast, [[Palau]] to the east and southeast, [[Indonesia]] to the south, [[Malaysia]] to the southwest, [[Vietnam]] to the west, and [[China]] to the northwest. It is the world's [[List of countries and dependencies by population|twelfth-most-populous country]], with diverse [[Ethnic groups in the Philippines|ethnicities]] and [[Culture of the Philippines|cultures]]. [[Manila]] is [[Capital of the Philippines|the country's capital]], and [[Cities of the Philippines#Largest cities|its most populated city]] is [[Quezon City]]. Both are within [[Metro Manila]]. |

|||

[[Negrito]]s, the archipelago's earliest inhabitants, were followed by [[Models of migration to the Philippines|waves]] of [[Austronesian peoples]]. The adoption of [[animism]], [[Hinduism]] with [[Buddhist]] influence, and [[Islam]] established [[History of the Philippines (900–1565)|island-kingdoms]] ruled by [[datu]]s, [[raja]]s, and [[List of Muslim states and dynasties|sultans]]. Extensive overseas trade with neighbors such as the late [[Tang dynasty|Tang]] or [[Southern Song|Song]] empire brought [[Sangley|Chinese]] people to the archipelago as well, which would also gradually settle in and [[Interethnic marriage|intermix]] over the centuries. |

|||

The Philippines' location on the Pacific [[Ring of Fire]] and close to the equator makes the Philippines prone to earthquakes and typhoons, but also endows it with abundant natural resources and some of the world's greatest [[megadiverse countries|biodiversity]]. The Philippines has an area of {{convert|300000|km2|sp=us|0}},<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.geoba.se/population.php?aw=world|title=Geoba.se: Gazetteer – The World – Top 100+ Countries by Area – Top 100+ By Country ()|work=geoba.se|accessdate=December 17, 2015}}</ref> and a population of approximately 100 million.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jul/27/philippines-chonalyn-baby-100m-population|title=Philippines joyous as baby Chonalyn's arrival means population hits 100m|work=the Guardian}}</ref><ref name="rappler.com">{{cite web|url=http://www.rappler.com/nation/64465-100-millionth-filipino-born|title=Philippine population officially hits 100 million|work=Rappler}}</ref> It is the [[List of Asian countries by population|eighth-most populated country in Asia]] and the [[List of countries and dependencies by population|12th most populated country]] in the world. {{as of|2013}}, approximately 10 million additional Filipinos [[Overseas Filipino|lived overseas]],<ref name="CFO2013">{{cite web|url=http://www.cfo.gov.ph/images/stories/pdf/StockEstimate2013.pdf|title=Stock Estimate of Filipinos Overseas As of December 2013|publisher=Philippine Overseas Employment Administration|accessdate=September 19, 2015}}</ref> comprising one of the world's largest [[diaspora]]s. Multiple [[Ethnic groups in the Philippines|ethnicities]] and cultures are found throughout the islands. In prehistoric times, [[Negrito]]s were some of the archipelago's earliest inhabitants. They were followed by [[Models of migration to the Philippines|successive waves]] of [[Austronesian peoples]].<ref name="Dyen1965">{{cite journal |author=Isidore Dyen|authorlink=Isidore Dyen|title=A Lexicostatistical Classification of the Austronesian Languages|journal=Internationald Journal of American Linguistics, Memoir|year=1965|volume=19|pages=38–46}}</ref> Exchanges with Chinese, [[Ethnic Malay|Malay]], [[Outline of ancient India|Indian]], and [[Islam]]ic nations occurred. Then, various competing maritime [[History of the Philippines (900–1521)|states]] were established under the rule of [[Datu]]s, [[Raja]]hs, [[Sultan]]s or [[Lakan]]s. |

|||

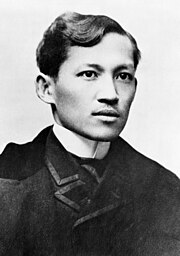

The arrival of [[Ferdinand Magellan]] |

The arrival of [[Ferdinand Magellan]], a [[Portuguese people|Portuguese]] explorer leading a fleet for [[Crown of Castile|Castile]], marked the beginning of [[Spanish Colonization in the Philippines|Spanish colonization]]. In 1543, Spanish explorer {{Lang|es|[[Ruy López de Villalobos]]|italic=no}} named the archipelago {{lang|es|Las Islas Filipinas}} in honor of [[King Philip II of Castile]]. Spanish colonization via [[New Spain]], beginning in 1565, led to the Philippines becoming ruled by the Crown of Castile, as part of the [[Spanish Empire]], for more than 300 years. [[Catholic Church|Catholic]] [[Christianity]] became the dominant religion, and Manila became the western hub of [[Spanish treasure fleet|trans-Pacific trade]]. [[Spaniard|Hispanic]] immigrants from [[Latin American Asian|Latin America]] and [[Iberia]] would also selectively colonize. The [[Philippine Revolution]] began in 1896, and became entwined with the 1898 [[Spanish–American War]]. Spain ceded the territory to the United States, and [[Hong Kong Junta|Filipino revolutionaries]] declared the [[First Philippine Republic]]. The ensuing [[Philippine–American War]] ended with the United States controlling the territory until the [[Philippines campaign (1941–1942)|Japanese invasion]] of the islands during [[World War II]]. After [[Philippines campaign (1944–1945)|the United States retook the Philippines from the Japanese]], the Philippines became independent in 1946. The country has had a tumultuous experience with democracy, which included the overthrow of [[Martial law under Ferdinand Marcos|a decades-long dictatorship]] in [[People Power Revolution|a nonviolent revolution]]. |

||

The Philippines is an [[emerging market]] and a [[developing country|developing]] and [[newly industrialized country]], whose economy is transitioning from being agricultural to service- and manufacturing-centered. It is a founding member of the [[United Nations]], the [[World Trade Organization]], [[ASEAN]], the [[Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation]] forum, and the [[East Asia Summit]]; it is a member of the [[Non-Aligned Movement]] and a [[major non-NATO ally]] of the United States. Its location as an island country on the Pacific [[Ring of Fire]] and close to the equator makes it prone to [[List of earthquakes in the Philippines|earthquakes]] and [[Typhoons in the Philippines|typhoons]]. The Philippines has a variety of natural resources and a globally-significant [[Megadiverse countries|level of biodiversity]]. |

|||

As the 19th century gave way to the 20th, there followed in quick succession the [[Philippine Revolution]], which spawned the short-lived [[First Philippine Republic]], followed by the bloody [[Philippine–American War]] of conquest by US military force.<ref name=Constantino1975/> Aside from the period of [[Japanese occupation of the Philippines|Japanese occupation]], the [[United States]] retained sovereignty over the islands until after [[World War II]], when the Philippines was recognized as an independent nation. Since then, the Philippines has often had a tumultuous experience with democracy, which included the overthrow of a dictatorship by [[People Power Revolution|a non-violent revolution]].<ref>{{cite web|url = http://www.stuartxchange.org/DayFour.html|title = The Original People Power Revolution|accessdate = February 28, 2008|publisher = QUARTET p. 77}}</ref> |

|||

== Etymology == |

|||

It is a founding member of the [[United Nations]], [[World Trade Organization]], [[Association of Southeast Asian Nations]], the [[Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation]] forum, and the [[East Asia Summit]]. It also hosts the headquarters of the [[Asian Development Bank]].<ref>{{cite web|title = Departments and Offices|url = http://www.adb.org/about/departments-offices#tabs-0-1|website = Asian Development Bank|publisher = Asian Development Bank|accessdate = November 26, 2015|last = admin}}</ref> The Philippines is considered to be an [[emerging market]] and a [[newly industrialized country]],<ref name=goldmann11>{{cite web|url=http://www.chicagobooth.edu/alumni/clubs/pakistan/docs/next11dream-march%20'07-goldmansachs.pdf|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110810095039/http://www.chicagobooth.edu/alumni/clubs/pakistan/docs/next11dream-march%20%2707-goldmansachs.pdf|title=The N-11: More Than an Acronym – Goldman Sachs|publisher=[[The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc.]]|archivedate=August 10, 2011|date=March 28, 2007}}</ref> which has an economy transitioning from being one based on agriculture to one based more on services and manufacturing.<ref name=CIAfactbookPhilEcon>[https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rp.html#Econ CIA World Factbook, Philippines] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150719222229/https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rp.html |date=July 19, 2015 }}, Retrieved May 15, 2009.</ref> It is one of the only two predominantly [[Christianity in Asia|Christian]] nations in [[Southeast Asia]], the other being [[East Timor]]. |

|||

{{main|Names of the Philippines}} |

|||

During his 1542 expedition, Spanish explorer [[Ruy López de Villalobos]] named the islands of [[Leyte]] and [[Samar]] "{{lang|es|Felipinas}}" after the [[Prince of Asturias]], later [[Philip II of Castile]]. Eventually, the name "{{lang|es|Las Islas Filipinas}}" would be used for the archipelago's Spanish possessions.<ref name="Scott-1994" />{{rp|page={{plain link|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=15KZU-yMuisC&pg=PA6|name=6}}}} Other names, such as "{{lang|es|Islas del Poniente}}" (Western Islands), "{{lang|pt|Islas del Oriente}}" (Eastern Islands), Ferdinand Magellan's name, and "{{lang|es|San Lázaro}}" (Islands of St. Lazarus), were used by the Spanish to refer to islands in the region before Spanish rule was established.<ref>{{cite book |last=Malcolm |first=George A. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tpEz7_tzzJoC |title=The Government of the Philippine Islands: Its Development and Fundamentals |series=Philippine Law Collection |date=1916 |publisher=[[Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company]] |isbn=<!-- ISBN unspecified --> |location=Rochester, N.Y. |page=[https://archive.org/details/cu31924051298937/page/2/mode/2up 3] |language=en |author-link=George A. Malcolm |oclc=578245510 |access-date=February 12, 2023 |archive-date=February 17, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230217144209/https://books.google.com/books?id=tpEz7_tzzJoC |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Spate |first=Oskar H.K. |title=The Spanish Lake |date=November 2004 |publisher=[[Taylor & Francis]] |isbn=978-0-7099-0049-8 |series=The Pacific since Magellan |volume=I |location=London, England |page=97 |chapter=Chapter 4. Magellan's Successors: Loaysa to Urdaneta. Two failures: Grijalva and Villalobos |doi=10.22459/SL.11.2004 |author-link=Oskar Spate |access-date=July 6, 2020 |orig-date=1979 |chapter-url=http://epress.anu.edu.au/spanish_lake/mobile_devices/ch04s05.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080805022835/http://epress.anu.edu.au/spanish_lake/mobile_devices/ch04s05.html |archive-date=August 5, 2008 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GIz4CDTCOwcC |title=The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia |date=1999 |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |isbn=978-0-521-66370-0 |editor-last=Tarling |editor-first=Nicholas |volume=2: From c. 1500 to c. 1800 |location=Cambridge, England |page=[https://books.google.com/books?id=GIz4CDTCOwcC&pg=PA12 12] |language=en |author-link=Nicholas Tarling |access-date=April 2, 2023 |archive-date=April 2, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230402114137/https://books.google.com/books?id=GIz4CDTCOwcC |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

During the [[Philippine Revolution]], the [[Malolos Congress]] proclaimed it the {{lang|es|República Filipina}} (the [[First Philippine Republic|Philippine Republic]]).<ref>{{#invoke:cite web||title=The 1899 Malolos Constitution |url=https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/constitutions/the-1899-malolos-constitution/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170605215334/https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/constitutions/the-1899-malolos-constitution/ |archive-date=June 5, 2017 |access-date=February 11, 2023 |website=[[Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines]] |at=Título I – De la República; Articulo 1 |language=es, en}}</ref> American colonial authorities referred to the country as the Philippine Islands (a translation of the Spanish name).<ref>{{Cite book |last=Constantino |first=Renato |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Q1ZxAAAAMAAJ |title=The Philippines: A Past Revisited |date=1975 |publisher=Tala Pub. Services |isbn=978-971-8958-00-1 |location=Quezon City, Philippines |author-link=Renato Constantino |access-date=February 3, 2024 |archive-date=February 3, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240203072918/https://books.google.com/books?id=Q1ZxAAAAMAAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> The [[United States]] began changing its nomenclature from "the Philippine Islands" to "the Philippines" in the Philippine Autonomy Act and the [[Jones Law (Philippines)|Jones Law]].<ref>{{#invoke:cite web||date=August 29, 1916 |title=The Jones Law of 1916 |url=https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/constitutions/the-jones-law-of-1916/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170808093938/https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/constitutions/the-jones-law-of-1916/ |archive-date=August 8, 2017 |access-date=March 12, 2021 |website=[[Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines]] |at=Section 1.―The Philippines}}</ref> The official title "Republic of the Philippines" was included in the 1935 constitution as the name of the future independent state,<ref>{{#invoke:cite web||title=The 1935 Constitution |url=https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/constitutions/the-1935-constitution/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170625234400/https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/constitutions/the-1935-constitution/ |archive-date=June 25, 2017 |access-date=February 11, 2023 |website=[[Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines]] |at=Article XVII, Section 1}}</ref> and in all succeeding constitutional revisions.<ref>{{#invoke:cite web||date=January 17, 1973 |title=1973 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines |url=https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/constitutions/1973-constitution-of-the-republic-of-the-philippines-2/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170625191553/https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/constitutions/1973-constitution-of-the-republic-of-the-philippines-2/ |archive-date=June 25, 2017 |access-date=March 14, 2021 |website=[[Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines]]}}</ref><ref>{{#invoke:cite web||date=February 11, 1987 |title=The Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines |url=https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/constitutions/1987-constitution/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170607182503/https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/constitutions/1987-constitution/ |archive-date=June 7, 2017 |access-date=March 14, 2021 |website=[[Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines]]}}</ref> |

|||

==Etymology== |

|||

{{Main article|Name of the Philippines}} |

|||

[[File:Pantoja de la Cruz Copia de Antonio Moro.jpg|thumb|upright|left|[[Philip II of Spain]].]] |

|||

== History == |

|||

The Philippines was named in honor of [[Philip II of Spain|King Philip II of Spain]]. Spanish explorer [[Ruy López de Villalobos]], during his expedition in 1542, named the islands of [[Leyte]] and [[Samar]] ''Felipinas'' after the then-[[Prince of Asturias]]. Eventually the name ''Las Islas Filipinas'' would be used to cover all the islands of the archipelago. Before that became commonplace, other names such as ''Islas del Poniente'' (Islands of the West) and Magellan's name for the islands ''San Lázaro'' were also used by the Spanish to refer to the islands.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=15KZU-yMuisC|title=Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society|author=Scott, William Henry|authorlink=William Henry Scott (historian)|publisher=Ateneo de Manila University Press|year=1994|page=[https://books.google.com/books?id=15KZU-yMuisC&pg=PA6 6]|isbn=971-550-135-4}}</ref><ref name=Spate>{{Cite book|url=http://epress.anu.edu.au/spanish_lake/mobile_devices/|chapterurl=http://epress.anu.edu.au/spanish_lake/mobile_devices/ch04s05.html|title=The Spanish Lake – The Pacific since Magellan, Volume I|chapter=Chapter 4. Magellan's Successors: Loaysa to Urdaneta. Two failures: Grijalva and Villalobos|author=Spate, Oskar H. K.|authorlink=Oskar Spate|publisher=Taylor & Francis|year=1979|page=97|isbn=0-7099-0049-X|accessdate=January 7, 2010}}</ref><ref name=Friis>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=veuwAAAAIAAJ&cd=5&dq=islas+del+poniente+san+lazaro&q=islas+del+poniente#search_anchor|title=The Pacific Basin: A History of Its Geographical Exploration|editor=Friis, Herman Ralph|publisher=American Geographical Society|year=1967|page=369}}</ref><ref name=Galang>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=lt5uAAAAMAAJ&cd=2&dq=islas+del+poniente+san+lazaro&q=islas+del+poniente+#search_anchor|title=Encyclopedia of the Philippines, Volume 15|author=[[Zoilo Galang|Galang, Zoilo M.]] (Ed.).|publisher=E. Floro|edition=3rd|year=1957|page=46}}</ref><ref name=Cambridge1>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=jtsMLNmMzbkC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q|title=The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia – Volume One, Part Two – From c. 1500 to c. 1800|author=Tarling, Nicholas|publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=Cambridge, UK|year=1999|page=[https://books.google.com/books?id=jtsMLNmMzbkC&pg=PA12&dq=#v=onepage&q&f=false 12]|isbn=0-521-66370-9}}</ref> |

|||

{{Main|History of the Philippines}} |

|||

{{For timeline|Timeline of Philippine history}} |

|||

=== Prehistory (pre–900) === |

|||

The official name of the Philippines has changed several times in the course of its history. During the [[Philippine Revolution]], the [[Malolos Congress]] proclaimed the establishment of the ''República Filipina'' or the ''[[First Philippine Republic|Philippine Republic]]''. From the period of the [[Spanish–American War]] (1898) and the [[Philippine–American War]] (1899–1902) until the [[Commonwealth of the Philippines|Commonwealth]] period (1935–46), American colonial authorities referred to the country as the ''Philippine Islands'', a translation of the Spanish name.<ref name=Constantino1975>{{cite book|last1=Constantino|first1=R|title=The Philippines: a Past Revisited|date=1975|publisher=Tala Pub. Services|location=Quezon City|accessdate=July 12, 2010}}</ref> From the [[Treaty of Paris (1898)|1898 Treaty of Paris]], the name ''Philippines'' began to appear and it has since become the country's common name. Since the end of [[World War II]], the official name of the country has been the ''Republic of the Philippines''.<ref name =PhilIs>[[Manuel Quezon III|Quezon, Manuel, III]]. (March 28, 2005). [http://www.quezon.ph/2005/03/28/323/ "The Philippines ''are'' or ''is''?"]. ''Manuel L. Quezon III: The Daily Dose''. Retrieved December 20, 2009.</ref> |

|||

{{Main|Prehistory of the Philippines}} |

|||

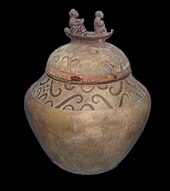

[[File:Manunggul Jar.jpg|thumb|upright|The [[Manunggul Jar|Manunggul burial jar]], one of the numerous [[burial jar]]s found on the cave system|alt=A burial jar with its lid decorated with two people on a boat]] |

|||

There is [[Archaeology of the Philippines|evidence]] of early [[hominins]] living in what is now the Philippines as early as 709,000 years ago.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Ingicco |first1=T. |last2=van den Bergh |first2=G. D. |last3=Jago-on |first3=C. |last4=Bahain |first4=J. |last5=Chacón |first5=M. G. |last6=Amano |first6=N. |last7=Forestier |first7=H. |last8=King |first8=C. |last9=Manalo |first9=K. |last10=Nomade |first10=S. |last11=Pereira |first11=A. |last12=Reyes |first12=M. C. |last13=Sémah |first13=A. |last14=Shao |first14=Q. |last15=Voinchet |first15=P. |date=May 1, 2018 |title=Earliest known hominin activity in the Philippines by 709 thousand years ago |url=https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6441&context=smhpapers |journal=Nature |publisher=[[University of Wollongong]] |volume=557 |issue=7704 |pages=233–237 |bibcode=2018Natur.557..233I |doi=10.1038/s41586-018-0072-8 |pmid=29720661 |s2cid=256771231 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190429133325/https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6441&context=smhpapers |archive-date=April 29, 2019 |first16=C. |last16=Falguères |first17=P.C.H. |last17=Albers |first18=M. |last18=Lising |first19=G. |last19=Lyras |first20=D. |last20=Yurnaldi |first21=P. |last21=Rochette |first22=A. |last22=Bautista |first23=J. |last23=de Vos| issn = 0028-0836 }}</ref> A small number of bones from [[Callao Cave]] potentially represent an otherwise unknown species, ''[[Homo luzonensis]]'', who lived 50,000 to 67,000 years ago.<ref>{{#invoke:cite news||last1=Greshko |first1=Michael |last2=Wei-Haas |first2=Maya |date=April 10, 2019 |title=New species of ancient human discovered in the Philippines |work=[[National Geographic]] |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2019/04/new-species-ancient-human-discovered-luzon-philippines-homo-luzonensis/ |access-date=October 24, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190410173110/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2019/04/new-species-ancient-human-discovered-luzon-philippines-homo-luzonensis/ |archive-date=April 10, 2019}}</ref><ref>{{#invoke:cite news||last1=Rincon |first1=Paul |date=April 10, 2019 |title=New human species found in Philippines |work=[[BBC News]] |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-47873072 |access-date=October 24, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190410192730/https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-47873072 |archive-date=April 10, 2019 |author-link1=Paul Rincon}}</ref> The oldest [[modern human]] remains on the islands are from the [[Tabon Caves]] of [[Palawan]], [[U/Th-dated]] to 47,000 ± 11–10,000 years ago.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Détroit |first1=Florent |last2=Dizon |first2=Eusebio |last3=Falguères |first3=Christophe |last4=Hameau |first4=Sébastien |last5=Ronquillo |first5=Wilfredo |last6=Sémah |first6=François |date=2004 |title=Upper Pleistocene ''Homo sapiens'' from the Tabon cave (Palawan, The Philippines): description and dating of new discoveries |url=http://fdetroit.free.fr/IMG/pdf/Detroit_etal_04_Tabon2.pdf |journal=Human Palaeontology and Prehistory |publisher=[[Elsevier]] |volume=3 |issue=2004 |pages=705–712 |bibcode=2004CRPal...3..705D |doi=10.1016/j.crpv.2004.06.004 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150218164554/http://fdetroit.free.fr/IMG/pdf/Detroit_etal_04_Tabon2.pdf |archive-date=February 18, 2015 |doi-access=free}}</ref> [[Tabon Man]] is presumably a [[Negrito]], among the archipelago's earliest inhabitants descended from the first human migrations out of Africa via the coastal route along [[South Asia|southern Asia]] to the now-sunken landmasses of [[Sundaland]] and [[Sahul]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Jett |first=Stephen C. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EgOUDgAAQBAJ |title=Ancient Ocean Crossings: Reconsidering the Case for Contacts with the Pre-Columbian Americas |date=2017 |publisher=[[University of Alabama Press]] |isbn=978-0-8173-1939-7 |location=Tuscaloosa, Ala. |pages=[https://books.google.com/books?id=EgOUDgAAQBAJ&pg=168 168–171] |access-date=May 23, 2020 |archive-date=February 3, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240203072920/https://books.google.com/books?id=EgOUDgAAQBAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

The first Austronesians reached the Philippines from Taiwan around 2200 BC, settling the [[Batanes]] Islands (where they built stone fortresses known as ''[[ijang]]s'')<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2005-006.pdf |title=The Protected Landscape Approach: Linking Nature, Culture and Community |date=2005 |publisher=[[International Union for Conservation of Nature|IUCN]] |isbn=978-2-8317-0797-6 |editor-last=Brown |editor-first=Jessica |location=Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, England |pages=101–102 |language=en |access-date=March 19, 2023 |editor-last2=Mitchell |editor-first2=Nora J. |editor-last3=Beresford |editor-first3=Michael |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180408232535/https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2005-006.pdf |archive-date=April 8, 2018}}</ref> and northern [[Luzon]]. [[Philippine jade culture|Jade artifacts]] have been dated to 2000 BC,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Scott |first=William Henry |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FSlwAAAAMAAJ |title=Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History |publisher=New Day Publishers |year=1984 |isbn=978-971-10-0227-5 |location=Quezon City, Philippines |page=17 |author-link=William Henry Scott (historian) |access-date=April 20, 2023 |archive-date=February 3, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240203072920/https://books.google.com/books?id=FSlwAAAAMAAJ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Ness |first=Immanuel |editor-last1=Bellwood |editor-first1=Peter |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2HMTBwAAQBAJ |title=The Global Prehistory of Human Migration |date=2014 |publisher=[[Wiley-Blackwell]] |isbn=978-1-118-97059-1 |location=Chichester, West Sussex, England |page=[https://books.google.com/books?id=2HMTBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA289 289] |author-link1=Immanuel Ness |editor-link1=Peter Bellwood |access-date=September 2, 2020 |archive-date=February 3, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240203072922/https://books.google.com/books?id=2HMTBwAAQBAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> with [[lingling-o]] jade items made in Luzon with raw materials from Taiwan.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Hung |first1=Hsiao-Chun |last2=Iizuka |first2=Yoshiyuki |last3=Bellwood |first3=Peter |last4=Nguyen |first4=Kim Dung |last5=Bellina |first5=Bérénice |last6=Silapanth |first6=Praon |last7=Dizon |first7=Eusebio |last8=Santiago |first8=Rey |last9=Datan |first9=Ipoi |last10=Manton |first10=Jonathan H. |date=December 11, 2007 |title=Ancient jades map 3,000 years of prehistoric exchange in Southeast Asia |journal=[[Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America]] |publisher=[[National Academy of Sciences]] |volume=104 |issue=50 |pages=19745–19750 |doi=10.1073/pnas.0707304104 |pmc=2148369 |pmid=18048347 |doi-access=free}}</ref> By 1000 BC, the inhabitants of the archipelago had developed into four societies: [[hunter-gatherer]] tribes, warrior societies, highland [[plutocracies]], and port principalities.<ref name="Legarda-2001">{{Cite journal |last=Legarda |first=Benito Jr. |author-link=Benito J. Legarda |year=2001 |title=Cultural Landmarks and their Interactions with Economic Factors in the Second Millennium in the Philippines |journal=Kinaadman (Wisdom): A Journal of the Southern Philippines |publisher=[[Xavier University – Ateneo de Cagayan]] |volume=23 |page=40}}</ref> |

|||

==History== |

|||

{{Main article|History of the Philippines}} |

|||

=== Early states (900–1565) === |

|||

===Prehistory=== |

|||

{{ |

{{main|History of the Philippines (900–1565)}} |

||

[[File: |

[[File:Naturales 4.png|thumb|A couple portrayed in 1590's Early Spanish colonial period of the Philippines draped in gold]] |

||

The earliest known surviving written record in the Philippines is the 900 AD [[Laguna Copperplate Inscription]], which was written in [[Old Malay]] using the early [[Kawi alphabet|Kawi]] script with a number of technical [[Sanskrit]] words and [[Old Javanese]] or [[Old Tagalog]] [[Filipino styles and honorifics|honorifics]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Postma |first=Antoon |author-link=Antoon Postma |date=1992 |title=The Laguna Copper-Plate Inscription: Text and Commentary |url=http://www.philippinestudies.net/ojs/index.php/ps/article/download/1033/1018 |journal=[[Philippine Studies (journal)|Philippine Studies]] |location=Quezon City, Philippines |publisher=[[Ateneo de Manila University]] |volume=40 |issue=2 |pages=182–203 |issn=0031-7837 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151208053836/http://www.philippinestudies.net/ojs/index.php/ps/article/download/1033/1018 |archive-date=December 8, 2015}}</ref> By the 14th century, several large coastal settlements emerged as trading centers and became the focus of [[Cultural achievements of pre-colonial Philippines|societal changes]].<ref name="deGraaf-1977">{{Cite book |last1=de Graaf |first1=Hermanus Johannes |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RYQeAAAAIAAJ |title=Geschichte: Lieferung 2 |last2=Kennedy |first2=Joseph |last3=Scott |first3=William Henry |date=1977 |publisher=[[Brill Publishers|Brill]] |isbn=978-90-04-04859-1 |location=Leiden, Switzerland |page=[https://books.google.com/books?id=RYQeAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA198 198] |language=en |author-link3=William Henry Scott (historian) |access-date=February 18, 2023 |archive-date=March 6, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230306102637/https://books.google.com/books?id=RYQeAAAAIAAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> Some [[polities]] had exchanges with other states throughout Asia.<ref name="Junker-1999">{{Cite book |last=Junker |first=Laura Lee |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yO2yG0nxTtsC |title=Raiding, Trading, and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms |date=1999 |publisher=[[University of Hawaiʻi Press]] |isbn=978-0-8248-2035-0 |location=Honolulu, Hawaii |access-date=August 22, 2020 |archive-date=February 3, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240203072919/https://books.google.com/books?id=yO2yG0nxTtsC |url-status=live }}</ref>{{rp|page=3}}<ref>{{Cite book |last=Nadeau |first=Kathleen M. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kAINJWo4IJ4C |title=Liberation Theology in the Philippines: Faith in a Revolution |date=2002 |publisher=[[Greenwood Publishing Group]] |isbn=978-0-275-97198-4 |location=Westport, Conn. |page=[https://books.google.com/books?id=kAINJWo4IJ4C&pg=PA8 8] |language=en |access-date=February 18, 2023 |archive-date=March 17, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230317084801/https://books.google.com/books?id=kAINJWo4IJ4C |url-status=live }}</ref> Trade with China began during the late [[Tang dynasty]],<ref>{{#invoke:cite web||url=https://www.nationalmuseum.gov.ph/2022/09/20/the-9th-to-10th-century-archaeological-evidence-of-maritime-relations-between-the-philippines-and-the-islands-of-southeast-asia/|title=The 9th to 10th century archaeological evidence of maritime relations between the Philippines and the islands of Southeast Asia|publisher=[[National Museum of the Philippines]]|access-date=December 4, 2023|date=n.d.}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Fox |first=Robert B. |author-link=Robert Bradford Fox |title=More Tsinoy Than We Admit: Chinese-Filipino Interactions Over the Centuries |publisher=Vibal Foundation, Inc. |year=2015 |isbn=9789719706823 |editor-last=Chu |editor-first=Richard T. |location=Quezon City |pages=10–13 |chapter=The Archaeological Record of Chinese Influences in the Philippines}}</ref> and expanded during the [[Song dynasty]].<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6kDm5d3cMIYC |title=Southeast Asia: From Prehistory to History |date=2004 |publisher=[[RoutledgeCurzon]] |isbn=978-0-415-29777-6 |editor-last=Glover |editor-first=Ian |location=London, England |page=[https://books.google.com/books?id=6kDm5d3cMIYC&pg=PA267 267] |author-link2=Peter Bellwood |editor-last2=Bellwood |editor-first2=Peter}}</ref><ref>{{#invoke:cite web||title=Pre-colonial Manila|url=http://malacanang.gov.ph/75832-pre-colonial-manila/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150724010336/http://malacanang.gov.ph/75832-pre-colonial-manila/|archive-date=July 24, 2015|access-date=December 26, 2020|website=Malacañan Palace: Presidential Museum And Library}}</ref><ref name=":0" /> Throughout the second millennium AD, some polities were also part of the [[tributary system of China]].<ref name="Scott-1994">{{Cite book |last=Scott |first=William Henry |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=15KZU-yMuisC |title=Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society |publisher=[[Ateneo de Manila University Press]] |year=1994 |isbn=978-971-550-135-4 |location=Quezon City, Philippines |author-link=William Henry Scott (historian) |access-date=October 18, 2015 |archive-date=February 3, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240203072920/https://books.google.com/books?id=15KZU-yMuisC |url-status=live }}</ref>{{rp|pages=177–178}}<ref name="Junker-1999" />{{rp|page=3}} With extensive trade and diplomacy, this brought [[Northern and southern China|Southern]] [[Han Chinese|Chinese]] merchants and migrants from [[Southern Fujian]], known as ''"Langlang"''<ref>{{Cite book |last=San Buena Ventura |first=Fr. Pedro de |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=A8QxAQAAMAAJ |title=Vocabulario de lengua tagala: El romance castellano puesto primero |publisher=La Noble Villa de Pila |year=1613 |editor-last=de Silva |editor-first=Juan (Don.) |page=545 |language=[[Tagalog language|Tagalog]] & [[Early Modern Spanish]] |quote=Sangley) Langlang (pc) anſi llamauan los viejos deſtos [a los] ſangleyes cuando venian [a tratar] con ellos |trans-quote=Sangley) Langlang (pc) this is what the elderlies called [the] Sangleyes when they came [to deal] with them}}</ref> and ''"Sangley"'' in later years,<ref>{{Cite book |last=San Buena Ventura |first=Fr. Pedro de |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=A8QxAQAAMAAJ |title=Vocabulario de lengua tagala: El romance castellano puesto primero |publisher=La Noble Villa de Pila |year=1613 |editor-last=de Silva |editor-first=Juan (Don.) |page=170 |language=[[Tagalog language|Tagalog]] & [[Early Modern Spanish]]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |url=https://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/metsnav/common/navigate.do?pn=1&size=large&oid=VAB8326 |title=Boxer Codex (Manila Manuscript) |others=[[Boxer Codex]], once kept by Sir [[C. R. Boxer]] |year=1590s |location=Manila |pages=415 [PDF] / 204 [As Written] |language=[[Early Modern Spanish]] & [[Philippine Hokkien|Early Manila Hokkien]] |via=[[Indiana University]] Digital Library, as digitized from the [[Lilly Library]] |access-date=March 24, 2024 |archive-date=March 24, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240324113344/https://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/metsnav/common/navigate.do?pn=1&size=large&oid=VAB8326 |url-status=live }}</ref> who would gradually settle and intermix in the Philippines. Indian cultural traits such as linguistic terms and religious practices [[Indian influences in early Philippine polities|began to spread]] in the Philippines during the 14th century, via the Indianized Hindu [[Majapahit|Majapahit Empire]].<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |title=Philippines |encyclopedia=Concise Encyclopedia of World History |publisher=[[Atlantic Books|Atlantic Publishers & Distributors]] |location=New Delhi, India |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gGKsS-9h4BYC |last=Ramirez-Faria |first=Carlos |date=2007 |page=[https://books.google.com/books?id=gGKsS-9h4BYC&pg=PA560 560] |isbn=978-81-269-0775-5 |access-date=February 18, 2023 |archive-date=January 17, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230117131629/https://books.google.com/books?id=gGKsS-9h4BYC |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Evangelista |first=Alfredo E. |date=1965 |title=Identifying Some Intrusive Archaeological Materials Found in Philippine Proto-historic Sites |url=https://asj.upd.edu.ph/mediabox/archive/ASJ-03-01-1965/Evangelista.pdf |journal=Asian Studies: Journal of Critical Perspectives on Asia |publisher=[[University of the Philippines Asian Center|Asian Center]], [[University of the Philippines]] |volume=3 |issue=1 |pages=87–88 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230429072742/https://asj.upd.edu.ph/mediabox/archive/ASJ-03-01-1965/Evangelista.pdf |archive-date=April 29, 2023 |access-date=April 29, 2023}}</ref> By the 15th century, Islam was established in the [[Sulu Archipelago]] and spread from there.<ref name="deGraaf-1977" /> |

|||

The [[metatarsal]] of the [[Callao Man]], reliably dated by [[Uranium-thorium dating|uranium-series dating]] to 67,000 years ago is the oldest human remnant found in the archipelago to date.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/philippines/7924538/Archaeologists-unearth-67000-year-old-human-bone-in-Philippines.html |title=Archaeologists unearth 67000-year-old human bone in Philippines |date=August 4, 2010 |accessdate=August 4, 2010 |location=London |work=The Daily Telegraph |first=Barney |last=Henderson}}</ref> This distinction previously belonged to the [[Tabon Man]] of [[Palawan]], carbon-dated to around 26,500 years ago.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/?id=pd6AAAAAMAAJ&q=tabon+man |title=The Tabon Caves: Archaeological Explorations and Excavations on Palawan |author=Fox, Robert B. |authorlink= Robert Bradford Fox |year=1970 |page=44 |accessdate=December 16, 2009 |publisher=National Museum |asin=B001O7GGNI}}</ref><ref name=Scott1984>{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/?id=FSlwAAAAMAAJ&q=pre-mongoloid |title = Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History |author = Scott, William Henry |authorlink = William Henry Scott (historian) |publisher = New Day Publishers |year = 1984 |location = Quezon City |isbn = 971-10-0227-2 |page = 15}}</ref> [[Negrito]]s were also among the archipelago's earliest inhabitants, but their first settlement in the Philippines has not been reliably dated.<ref name=Scott1A>{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/?id=FSlwAAAAMAAJ&q=pygmy+Negrito |title = Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History |author = Scott, William Henry |authorlink = William Henry Scott (historian) |publisher = New Day Publishers |year = 1984 |location = Quezon City |isbn = 971-10-0227-2 |quote = Not one roof beam, not one grain of rice, not one pygmy Negrito bone has been recovered. Any theory which describes such details is therefore pure hypothesis and should be honestly presented as such. |page = 138}}</ref> |

|||