KH-7 Gambit: Difference between revisions

m fix image options |

|||

| (38 intermediate revisions by 24 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Series of United States reconnaissance satellites}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Use American English|date=November 2021}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=November 2021}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | [[BYEMAN]] codenamed '''GAMBIT''', the '''KH-7''' ('''Air Force Program 206''') was a [[reconnaissance satellite]] used by the [[United States]] from July 1963 to June 1967. Like the older [[Corona (satellite)|CORONA]] system, it acquired [[imagery intelligence]] by taking photographs and returning the undeveloped film to earth. It achieved a typical ground-resolution of {{convert|2|ft|abbr=on}} to {{convert|3|ft|abbr=on}}.<ref name="NRO_AnalysisP206">{{cite web|url=http://www.nro.gov/foia/declass/GAMHEX/GAMBIT/2.PDF|title=Summary Analysis of Program 206 (GAMBIT)|publisher=National Reconnaissance Office|date=1967-08-29|access-date=2011-10-07|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111017023922/http://nro.gov/foia/declass/GAMHEX/GAMBIT/2.PDF|archive-date=2011-10-17|url-status=dead}} {{PD-notice}}</ref> Though most of the imagery from the KH-7 satellites was declassified in 2002, details of the satellite program (and the satellite's construction) remained classified until 2011.<ref>[http://www.thespacereview.com/article/1927/1 Flashlights in the dark], The Space Review</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | In its summary report following the conclusion of the program, the [[National Reconnaissance Office]] concluded that the |

||

| ⚫ | In its summary report following the conclusion of the program, the [[National Reconnaissance Office]] concluded that the GAMBIT program was considered highly successful in that it produced the first high-resolution satellite photography, 69.4% of the images having a resolution under {{convert|3|ft|abbr=on}}; its record of successful launches, orbits, and recoveries far surpassed the records of earlier systems; and it advanced the state of the art to the point where follow-on larger systems could be developed and flown successfully. The report also stated that Gambit had provided the intelligence community with the first high-resolution satellite photography of denied areas, the intelligence value of which was considered "extremely high".<ref name="NRO_AnalysisP206"/> In particular, its overall success stood in sharp contrast to the two first-generation photoreconnaissance programs, [[Corona (satellite)|Corona]], which suffered far too many malfunctions to achieve any consistent success, and [[Samos (satellite)|SAMOS]], which was essentially a complete failure with all satellites either being lost in launch mishaps or returning no usable imagery. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | GAMBIT emerged in 1962 as an alternative to the less-than-successful CORONA and the completely failed SAMOS, although CORONA was not cancelled and in fact continued operating alongside the newer program into the early 1970s. While CORONA used the [[Thor-Agena]] launch vehicle family, GAMBIT would be launched on [[Atlas-Agena]], the booster used for SAMOS. After the improved [[KH-8 Gambit 3|KH-8 GAMBIT-3]] satellite was developed during 1965, operations shifted to the larger [[Titan IIIB]] launch vehicle. |

||

== System configuration == |

== System configuration == |

||

[[File:KH-7 GAMBIT 1 02.jpg|thumb|KH-7 GAMBIT |

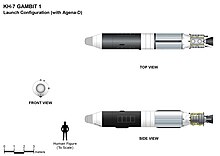

[[File:KH-7 GAMBIT 1 02.jpg|thumb|A KH-7 GAMBIT-1 launch configuration (with Agena D service module).]] |

||

[[File:KH-7 GAMBIT 1 01.jpg|thumb|KH-7 GAMBIT |

[[File:KH-7 GAMBIT 1 01.jpg|thumb|A KH-7 GAMBIT-1 on-orbit configuration (w/o Agena D service module).]] |

||

[[File:GAMBIT ReconnaissanceSystem.tiff|thumb|GAMBIT |

[[File:GAMBIT ReconnaissanceSystem.tiff|thumb|A GAMBIT Reconnaissance System.]] |

||

[[File:KH7GambitDisplayNationalMuseumUSAF.jpg|thumb|KH-7 |

[[File:KH7GambitDisplayNationalMuseumUSAF.jpg|thumb|A KH-7 GAMBIT in launch configuration on display at the [[National Museum of the United States Air Force]] in [[Dayton, Ohio]].]] |

||

Each |

Each GAMBIT-1 satellite was about {{convert|15|ft|abbr=on}} long, {{convert|5|ft|abbr=on}} wide, weighed about {{convert|1154|lb|abbr=on}}, and carried about {{convert|3000|ft|abbr=on}} of film.<ref name="Space.com">{{cite web|url=http://www.space.com/14394-declassified-spy-satellites-air-force.html|title=Declassified U.S. Spy Satellites from Cold War Land in Ohio|date=28 January 2012 |publisher=Space.com|access-date=2015-10-11}}</ref> |

||

A feasibility study for the [[Geodetic Orbital Photographic Satellite System]] reveals three subsystems for |

A feasibility study for the [[Geodetic Orbital Photographic Satellite System]] reveals three subsystems for U.S. optical reconnaissance satellites in the 1960s: the [[Orbiting Control Vehicle|Orbital (or Orbiting) Control Vehicle]] (OCV), the Data Collection Module (DCM), and the Recovery Section (RS).<ref name="NRO4E0007">{{cite web|url=http://www.nro.gov/foia/CAL-Records/Cabinet4/DrawerE/4%20E%200008.pdf |title=Feasibility Study Final Report: Geodetic Optical Photographic Satellite System, Volume 2 Data Collection System|publisher=National Reconnaissance Office|access-date=2010-12-19|date=June 1966|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131212173314/http://www.nro.gov/foia/CAL-Records/Cabinet4/DrawerE/4%20E%200008.pdf|archive-date=2013-12-12|url-status=dead}}</ref> For the KH-7, the DCM is also called the Camera Optics Module (COM), and is integrated in the OCV, which has a length of {{cvt|5.5|m}} and a diameter of {{cvt|1.52|m}}.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thespacereview.com/article/1734/1|title=Black Apollo |website=thespacereview.com|first=Dwayne A.|last=Day|access-date=2010-12-17|date=2010-11-29}}</ref> |

||

===Camera Optics Module=== |

=== Camera Optics Module === |

||

The Camera Optics Module of KH-7 consists of three cameras: a single strip camera, a stellar camera, and an index camera. |

The Camera Optics Module of KH-7 consists of three cameras: a single strip camera, a stellar camera, and an index camera. |

||

In the strip camera the ground image is reflected by a steerable flat mirror to a {{ |

In the strip camera the ground image is reflected by a steerable flat mirror to a {{cvt|1.21|m}} diameter stationary [[concave mirror|concave]] primary mirror. The primary mirror reflects the light through an opening in the flat mirror and through a [[Ross (optics)|Ross corrector]]. It took images of a 6.3° wide ground swath by exposing a {{cvt|22|cm}} wide moving portion of film through a small slit aperture.<ref name="NRO_KH7Camera">{{cite web|url=http://www.nro.gov/history/csnr/gambhex/index.html|title=KH-7 Camera System- Part I|publisher=National Photographic Interpretation Center|date=July 1963|access-date=2011-09-26|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120915093330/http://www.nro.gov/history/csnr/gambhex/index.html|archive-date=2012-09-15|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="IkesGambit">{{cite web |url=http://www.thespacereview.com/article/1279/1|title=Ike's gambit: The development and operations of the KH-7 and KH-8 spy satellites|website=thespacereview.com|first=Dwayne A.|last=Day|access-date=2009-01-25|date=2010-11-29}}</ref> The initial [[NIIRS|ground resolution]] of the satellite was {{cvt|1.2|m}}, but improved to {{cvt|0.6|m}} by 1966. Each satellite weighed about {{cvt|2000|kg}}, and returned a single film bucket per mission. The camera and film transport system were manufactured by [[Eastman Kodak Company]].<ref name="IkesGambit"/> |

||

The index camera is a copy of cameras systems previously used in the KH-4 and KH-6 satellites, and takes exposures of Earth in direction of the vehicle roll position for attitude determination. The stellar camera takes images of star fields with a reseau grid being superimposed on the image plane.<ref name="NRO_KH7Camera"/> The S/I camera was provided by [[Itek]], and horizon sensors were provided by [[Barnes Engineering Co]].<ref name="NRO_AnalysisP206"/> |

The index camera is a copy of cameras systems previously used in the KH-4 and KH-6 satellites, and takes exposures of [[Earth]] in direction of the vehicle roll position for attitude determination. The stellar camera takes images of star fields with a reseau grid being superimposed on the image plane.<ref name="NRO_KH7Camera"/> The S/I camera was provided by [[Itek]], and horizon sensors were provided by [[Barnes Engineering Co]].<ref name="NRO_AnalysisP206"/> |

||

===Orbital Control Vehicle and Recovery Vehicle=== |

=== Orbital Control Vehicle and Recovery Vehicle === |

||

[[File:KH film recovery.jpg|thumb|right|A film capsule being retrieved]] |

[[File:KH film recovery.jpg|thumb|upright=1.0|right|A film capsule being retrieved.]] |

||

The primary contractor for the Orbital Control Vehicle and the Recovery Vehicle was [[General Electric]].<ref name="NRO_AnalysisP206"/> |

|||

Films were to be [[Mid- |

The primary contractor for the Orbital Control Vehicle and the Recovery Vehicle was [[General Electric]].<ref name="NRO_AnalysisP206"/> Films were to be [[Mid-air retrieval|retrieved mid-air]] by a [[C-130 Hercules]] specially outfitted for that purpose.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/K/Key_Hole.html|title=Key Hole (KH)|access-date=4 November 2015}}</ref> |

||

== Mission == |

== Mission == |

||

All KH-7 satellites were launched from [[Point Arguello]], which became part of |

All KH-7 satellites were launched from [[Point Arguello]], which became part of Vandenberg Air Force Base in July 1964. KH-7 satellites flew 38 missions, numbered 4001-4038, of which 34 returned film, and of these, 30 returned usable imagery. Mission duration was 1 to 8 days.<ref>{{cite web|title=NRO review and redaction guide (2006 ed.)|url=http://www.fas.org/irp/nro/declass.pdf|publisher=National Reconnaissance Office}}</ref> KH-7 satellites logged a total of almost 170 operational days in orbit.<ref name="NRO_AnalysisP206"/> |

||

== Functionality == |

== Functionality == |

||

[[File:KH7 ShuanchengtzuMissileCenterA19670529.png|thumb|KH-7 image of the Chinese Shuanchengtzu Missile Center A |

[[File:KH7 ShuanchengtzuMissileCenterA19670529.png|thumb|upright=1.0|right|A KH-7 image of the Chinese Shuanchengtzu Missile Center A, May 1967.]] |

||

| ⚫ | A high-resolution instrument, the KH-7 took detailed pictures of "hot spots" and most of its photographs are of Chinese and Soviet nuclear and missile installations, with smaller amounts of coverage of cities and harbors.<ref>NARA [https://research.archives.gov/search ARC] database description of "Keyhole-7 (KH-7) Satellite Imagery, 07/01/1963 - 06/30/1967", accession number NN3-263-02-011</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | A high-resolution instrument, the KH-7 took detailed pictures of "hot spots" and most of its photographs are of Chinese and Soviet nuclear and missile installations, with smaller amounts of coverage of cities and harbors.<ref>NARA [https://research.archives.gov/search ARC] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170501232731/https://research.archives.gov/search/ |date=1 May 2017 }} database description of "Keyhole-7 (KH-7) Satellite Imagery, 07/01/1963 - 06/30/1967", accession number NN3-263-02-011</ref> Most of the imagery from this camera, amounting to 19,000 images, was declassified in 2002 as a result of Executive order 12951,<ref>{{cite web|title=National Archives Releases Recently Declassified Satellite Imagery|date=2002-10-09|publisher=National Archives and Records Administration press release|url=https://www.archives.gov/press/press-releases/2003/nr03-02.html}} {{PD-notice}}</ref> the same order which declassified [[CORONA (satellite)|CORONA]], and copies of the films were transferred to the [[U.S. Geological Survey]]'s Earth Resources Observation Systems office.<ref>[http://edc.usgs.gov/ edc.usgs.gov] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070630040722/http://edc.usgs.gov/|date=2007-06-30}}</ref> Approximately 100 frames covering the state of [[Israel]] remain classified.<ref>{{cite web|title=Historical imagery declassification|publisher=National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency|url=http://www.nga.mil/portal/site/nga01/index.jsp?epi-content=GENERIC&itemID=5b08f8d62404af00VgnVCMServer23727a95RCRD&beanID=1629630080&viewID=FAQ|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071007062938/http://www.nga.mil/portal/site/nga01/index.jsp?epi-content=GENERIC&itemID=5b08f8d62404af00VgnVCMServer23727a95RCRD&beanID=1629630080&viewID=FAQ|archive-date=2007-10-07}} {{PD-notice}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | In early 1964, the CIA toyed with the idea of using |

||

| ⚫ | In early 1964, the CIA toyed with the idea of using GAMBIT to photograph military installations in [[Cuba]], but this was dismissed as unworkable as the satellites were primarily designed with higher-latitude Soviet territory in mind and because it would mean wasting an entire satellite on the Latin America-Caribbean area which had little else of interest to U.S. intelligence services. It was decided that U-2 spyplane flights were adequate to provide coverage of Cuban activity. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Mission 4009 included an [[ELINT]] P-11 subsatellite for radar monitoring, which was launched into a higher orbit.<ref name="1964-036B">{{cite web|url= |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Mission 4009 included an [[ELINT]] P-11 subsatellite for radar monitoring, which was launched into a higher orbit.<ref name="1964-036B">{{cite web|url=https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1964-036B|title=1964-036B|publisher=NASA|date=2010-10-08}} {{PD-notice}}</ref><ref name="Spacereview20090427">{{cite web|url=http://www.thespacereview.com/article/1360/1|title=Robotic ravens: American ferret satellite operations during the Cold War|publisher=The Space Review|date=2009-04-27|first=Dwayne|last=Day}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

{| class="wikitable" |

{| class="wikitable" |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Line 51: | Line 57: | ||

! [[NSSDC]] ID No. |

! [[NSSDC]] ID No. |

||

! Launch Vehicle |

! Launch Vehicle |

||

! [[Perigee]] (km) |

! [[Apsis|Perigee]] (km) |

||

! [[Apogee]] (km) |

! [[Apsis|Apogee]] (km) |

||

! Inclination (deg) |

! [[Orbital inclination|Inclination]] (deg) |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| '''KH7-1''' |

| '''KH7-1''' |

||

| Line 59: | Line 65: | ||

| 1963-07-12 |

| 1963-07-12 |

||

| OPS-1467 |

| OPS-1467 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1963-028A 1963-028A] |

||

| Atlas |

| [[Atlas-Agena]] D |

||

| 164 |

| 164 |

||

| 164 |

| 164 |

||

| Line 69: | Line 75: | ||

| 1963-09-06 |

| 1963-09-06 |

||

| OPS-1947 |

| OPS-1947 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1963-036A 1963-036A] |

||

| Atlas Agena D |

| Atlas Agena D |

||

| 168 |

| 168 |

||

| Line 79: | Line 85: | ||

| 1963-10-25 |

| 1963-10-25 |

||

| OPS-2196 |

| OPS-2196 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1963-041A 1963-041A] |

||

| Atlas Agena D |

| Atlas Agena D |

||

| 144 |

| 144 |

||

| Line 89: | Line 95: | ||

| 1963-12-18 |

| 1963-12-18 |

||

| OPS-2372 |

| OPS-2372 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1963-051A 1963-051A] |

||

| Atlas Agena D |

| Atlas Agena D |

||

| 122 |

| 122 |

||

| Line 99: | Line 105: | ||

| 1964-02-25 |

| 1964-02-25 |

||

| OPS-2423 |

| OPS-2423 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1964-009A 1964-009A] |

||

| Atlas Agena D |

| Atlas Agena D |

||

| 173 |

| 173 |

||

| Line 109: | Line 115: | ||

| 1964-03-11 |

| 1964-03-11 |

||

| OPS-3435 |

| OPS-3435 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1964-012A 1964-012A] |

||

| Atlas Agena D |

| Atlas Agena D |

||

| 163 |

| 163 |

||

| Line 119: | Line 125: | ||

| 1964-04-23 |

| 1964-04-23 |

||

| OPS-3743 |

| OPS-3743 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1964-020A 1964-020A] |

||

| Atlas Agena D |

| Atlas Agena D |

||

| 150 |

| 150 |

||

| Line 129: | Line 135: | ||

| 1964-05-19 |

| 1964-05-19 |

||

| OPS-3592 |

| OPS-3592 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1964-024A 1964-024A] |

||

| Atlas Agena D |

| Atlas Agena D |

||

| 141 |

| 141 |

||

| Line 139: | Line 145: | ||

| 1964-07-06 |

| 1964-07-06 |

||

| OPS-3684 |

| OPS-3684 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1964-036A 1964-036A] |

||

| Atlas Agena D |

| Atlas Agena D |

||

| 121 |

| 121 |

||

| Line 149: | Line 155: | ||

| 1964-08-14 |

| 1964-08-14 |

||

| OPS-3802 |

| OPS-3802 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1964-045A 1964-045A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 149 |

| 149 |

||

| Line 159: | Line 165: | ||

| 1964-09-23 |

| 1964-09-23 |

||

| OPS-4262 |

| OPS-4262 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1964-058A 1964-058A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 145 |

| 145 |

||

| Line 169: | Line 175: | ||

| 1964-10-08 |

| 1964-10-08 |

||

| OPS-4036 |

| OPS-4036 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=NNN6402 1964-F11] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| --- |

| --- |

||

| Line 179: | Line 185: | ||

| 1964-10-23 |

| 1964-10-23 |

||

| OPS-4384 |

| OPS-4384 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1964-068A 1964-068A] |

||

| Atlas Agena D |

| Atlas Agena D |

||

| 139 |

| 139 |

||

| Line 189: | Line 195: | ||

| 1964-12-04 |

| 1964-12-04 |

||

| OPS-4439 |

| OPS-4439 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1964-079A 1964-079A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 158 |

| 158 |

||

| Line 199: | Line 205: | ||

| 1965-01-23 |

| 1965-01-23 |

||

| OPS-4703 |

| OPS-4703 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1965-005A 1965-005A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 146 |

| 146 |

||

| Line 209: | Line 215: | ||

| 1965-03-12 |

| 1965-03-12 |

||

| OPS-4920 |

| OPS-4920 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1965-019A 1965-019A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 93 |

| 93 |

||

| Line 219: | Line 225: | ||

| 1965-04-28 |

| 1965-04-28 |

||

| OPS-4983 |

| OPS-4983 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1965-031A 1965-031A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 180 |

| 180 |

||

| Line 229: | Line 235: | ||

| 1965-05-27 |

| 1965-05-27 |

||

| OPS-5236 |

| OPS-5236 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1965-041A 1965-041A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 149 |

| 149 |

||

| Line 239: | Line 245: | ||

| 1965-06-25 |

| 1965-06-25 |

||

| OPS-5501 |

| OPS-5501 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1965-050B 1965-050B] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 151 |

| 151 |

||

| Line 249: | Line 255: | ||

| 1965-07-12 |

| 1965-07-12 |

||

| OPS-5810 |

| OPS-5810 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=NNN6502 1965-F07] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| --- |

| --- |

||

| Line 259: | Line 265: | ||

| 1965-08-03 |

| 1965-08-03 |

||

| OPS-5698 |

| OPS-5698 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1965-062A 1965-062A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 149 |

| 149 |

||

| Line 269: | Line 275: | ||

| 1965-09-30 |

| 1965-09-30 |

||

| OPS-7208 |

| OPS-7208 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1965-076A 1965-076A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 98 |

| 98 |

||

| Line 279: | Line 285: | ||

| 1965-11-08 |

| 1965-11-08 |

||

| OPS-6232 |

| OPS-6232 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1965-090B 1965-090B] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 145 |

| 145 |

||

| Line 289: | Line 295: | ||

| 1966-01-19 |

| 1966-01-19 |

||

| OPS-7253 |

| OPS-7253 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1966-002A 1966-002A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 150 |

| 150 |

||

| Line 299: | Line 305: | ||

| 1966-02-15 |

| 1966-02-15 |

||

| OPS-1184 |

| OPS-1184 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1966-012A 1966-012A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 148 |

| 148 |

||

| Line 309: | Line 315: | ||

| 1966-03-18 |

| 1966-03-18 |

||

| OPS-0879 |

| OPS-0879 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1966-022A 1966-022A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 162 |

| 162 |

||

| Line 319: | Line 325: | ||

| 1966-04-19 |

| 1966-04-19 |

||

| OPS-0910 |

| OPS-0910 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1966-032A 1966-032A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 139 |

| 139 |

||

| Line 329: | Line 335: | ||

| 1966-05-14 |

| 1966-05-14 |

||

| OPS-1950 |

| OPS-1950 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1966-039A 1966-039A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 133 |

| 133 |

||

| 358 |

| 358 |

||

| |

| 110.5 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| '''KH7-29''' |

| '''KH7-29''' |

||

| Line 339: | Line 345: | ||

| 1966-06-03 |

| 1966-06-03 |

||

| OPS-1577 |

| OPS-1577 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1966-048A 1966-048A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 143 |

| 143 |

||

| Line 349: | Line 355: | ||

| 1966-07-12 |

| 1966-07-12 |

||

| OPS-1850 |

| OPS-1850 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1966-062A 1966-062A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 137 |

| 137 |

||

| Line 359: | Line 365: | ||

| 1966-08-16 |

| 1966-08-16 |

||

| OPS-1832 |

| OPS-1832 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1966-074A 1966-074A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 146 |

| 146 |

||

| Line 369: | Line 375: | ||

| 1966-09-16 |

| 1966-09-16 |

||

| OPS-1686 |

| OPS-1686 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1966-083A 1966-083A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 148 |

| 148 |

||

| Line 379: | Line 385: | ||

| 1966-10-12 |

| 1966-10-12 |

||

| OPS-2055 |

| OPS-2055 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1966-090A 1966-090A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 155 |

| 155 |

||

| Line 389: | Line 395: | ||

| 1966-11-02 |

| 1966-11-02 |

||

| OPS-2070 |

| OPS-2070 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1966-098A 1966-098A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 159 |

| 159 |

||

| Line 399: | Line 405: | ||

| 1966-12-05 |

| 1966-12-05 |

||

| OPS-1890 |

| OPS-1890 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1966-109A 1966-109A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 137 |

| 137 |

||

| Line 409: | Line 415: | ||

| 1967-02-02 |

| 1967-02-02 |

||

| OPS-4399 |

| OPS-4399 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1967-007A 1967-007A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 136 |

| 136 |

||

| Line 419: | Line 425: | ||

| 1967-05-22 |

| 1967-05-22 |

||

| OPS-4321 |

| OPS-4321 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1967-050A 1967-050A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 135 |

| 135 |

||

| Line 429: | Line 435: | ||

| 1967-06-04 |

| 1967-06-04 |

||

| OPS-4360 |

| OPS-4360 |

||

| [ |

| [https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1967-055A 1967-055A] |

||

| SLV-3 Agena D |

| SLV-3 Agena D |

||

| 149 |

| 149 |

||

| Line 439: | Line 445: | ||

== History == |

== History == |

||

[[File:United States Capitol KeyHole-7 25.jpg |

[[File:United States Capitol KeyHole-7 25.jpg|thumb|upright=1.0|right|An enlargement of a photograph of the [[U.S. Capitol]] taken by KH-7 mission 4025 on 19 February 1966.]] |

||

[[File:1960s Atlas-Agena-KH-7 SLC-4 09892K.jpg|thumb|KH-7 GAMBIT optical reconnaissance satellite]] |

[[File:1960s Atlas-Agena-KH-7 SLC-4 09892K.jpg|thumb|upright=1.0|right|A KH-7 GAMBIT optical reconnaissance satellite.]] |

||

:''Section source: Space Review''<ref name="IkesGambit"/> |

:''Section source: Space Review''<ref name="IkesGambit"/> |

||

GAMBIT marked the first use of next-generation launch vehicle systems as Convair and Lockheed, the builders of the Atlas-Agena booster, began introducing improved, standardized launchers to replace the multitude of customized variants used up to 1963, which caused endless mix ups, poor reliability, and mission failures. This followed a recommendation by the Lewis Spaceflight Center in [[Cleveland, Ohio]] that Atlas and Agena switch to one standard configuration for both [[NASA]] and Air Force launches, with uniform testing and checkout procedures, as well as improved materials and fabrication processes for the various hardware components in the boosters. The Agena D, a standardized Agena B, arrived first, with the uprated [[Atlas SLV-3]] taking another year to fly. The first eight GAMBIT flown still used custom-modified Atlas D ICBM cores, with GAMBIT 4010 in August 1964 being the first use of the SLV-3. Afterwards, all GAMBIT used SLV-3s aside from 4013, which used the last old-style Atlas remaining in the inventory. |

|||

In early 1963, the |

In early 1963, the GAMBIT program began with failures. On 11 May 1963, the first GAMBIT satellite sat atop Atlas-Agena 190D on SLC-4W at Vandenberg Air Force Base awaiting launch. An air bubble formed while loading LOX into the booster and as soon as propellant filling was stopped, the bubble damaged the fill/drain valve. This quickly caused both the [[Liquid oxygen|LOX]] and helium pressure gas to escape from the tank, depressurizing the Atlas's [[Balloon tank|balloon skin]] and causing the entire launch vehicle to crumple to the ground. The [[RP-1]] tank ruptured and spilled its contents onto the pad. There was no fire or explosion, but the Agena sustained minor damage and the satellite a considerable amount as the cameras were crushed in by impact with the ground and had their lenses destroyed. The pad itself was undamaged except for a steel beam cracked by exposure to the super-chilled LOX, which was repaired in two days. Fortunately, the satellite on the booster was not the same one planned for the actual launch and the payload shroud had also remained in one piece, preventing any unauthorized parties from seeing the GAMBIT. Secrecy surrounding the program was strict and knowledge of GAMBIT limited only to those directly involved in the program. While the early [[CORONA (satellite)|CORONA]] and [[Samos (satellite)|SAMOS]] flights had been merely billed to the public as scientific missions, it became increasingly difficult to explain why they failed to return any scientific data. In late 1961, President [[John F. Kennedy]] ordered a veil of secrecy placed around the photoreconnaissance program and by GAMBIT's debut in 1963, DoD announcements described no details other than the launching of a "classified payload". |

||

The Agena was sent back to Lockheed for repairs and a different Atlas (vehicle 201D) was used, and the first successful |

The Agena was sent back to Lockheed for repairs and a different Atlas (vehicle 201D) was used, and the first successful GAMBIT mission was launched on 12 July 1963. The launch vehicle performed perfectly and inserted GAMBIT into polar orbit with a {{cvt|189|km}} altitude. The Air Force designated this mission number 4001. |

||

[[Aerospace Corporation]] recommended that, during |

[[Aerospace Corporation]] recommended that, during GAMBIT's first flights, the [[Orbital Control Vehicle]] (OCV) should remain attached to the Agena. This was a proven successful process for other Agena tests; and whereas the OCV was not. This decision limited GAMBIT's functionality, meaning that photographs could only be taken of targets directly below the vehicle. Once the successful photographic phase of the mission 4002 was completed, the OCV and the Agena were separated and the reentry vehicle would come down into the ocean northwest of [[Hawaii]]. The re-entry vehicle was caught in mid-air with a [[C-130 Hercules]] aircraft using a modified version of the [[Fulton surface-to-air recovery system]]. The film canister was then immediately transported to [[Eastman Kodak]]'s ''Hawkeye'' facility in [[Rochester, New York]] for processing.<ref>{{cite tech report |title=National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide |chapter=Appendix C - Glossary of Code Words and Terms|url=https://irp.fas.org/nro/review-2008.pd |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231109042332/https://irp.fas.org/nro/review-2008.pdf |archive-date=9 November 2023 |url-status=live |publisher=[[National Reconnaissance Office]] |year=2008}} {{PD-notice}}</ref> The developed results was sent to [[United States Air Force|US Air Force]] imagery research analysts in [[Washington, DC]]. |

||

GAMBIT mission 4003, was launched on |

GAMBIT mission 4003, was launched on 25 October 1963. The film canister was again ejected successfully after the photographic phase and the capsule recovered by an aircraft. Other tests were carried out with the OCV. |

||

GAMBIT mission 4004 was launched and its film canister recovered on |

GAMBIT mission 4004 was launched and its film canister recovered on 18 December 1963. Missions 4005 through 4007 were also successful. |

||

In May 1964, mission 4008 suffered major problems when the Agena did an unexplained roll during the boost phase. Even with OCV system problems, the film canister was able to return some imagery. |

In May 1964, mission 4008 suffered major problems when the Agena did an unexplained roll during the boost phase. Even with OCV system problems, the film canister was able to return some imagery. |

||

A variety of problems occurred with many of the remaining missions including poor or no imagery. Many of these difficulties were caused by the unreliable wire recording system carried by the |

A variety of problems occurred with many of the remaining missions including poor or no imagery. Many of these difficulties were caused by the unreliable wire recording system carried by the GAMBITs (tape recorders were not yet in widespread use in the mid-1960s). Two satellites ended up in the Pacific Ocean. The first of them was 4012, launched on October 8, 1964. The Agena engine shut down after 1.5 seconds of operation and the GAMBIT did not attain orbit. An investigation of the failure found that an electrical short occurred in an engine relay box, resulting in a cutoff signal being issued 0.4 seconds after ignition. As soon as the engine arming command was stopped at 1.5 seconds, the Agena propulsion system shut down. Examination of factory records for the Agena found that a pair of metal screws from a little-used terminal connector had broken off and disappeared to parts unknown; it was speculated that they landed somewhere as to cause a short. Telemetry data indicated otherwise entirely normal performance of all Agena systems. The other failure was 4020, launched on 12 July 1965 when the Atlas programmer accidentally issued simultaneous SECO and BECO commands, the resultant propulsion system shutdown sending the launch vehicle into the Pacific Ocean some {{cvt|1090|km}} downrange. The latter was the first flight witnessed by newly arrived Brig. Gen John L. Martin who replaced Maj. Gen Robert Greer as head of the KH-7 program. Martin cracked down and began demanding higher workmanship and quality standards. He is credited with having significantly improved the success rate of the program. |

||

| ⚫ | It was noted that the GAMBIT flights through the first half of 1964 had been mostly successful, but a string of malfunctions occurred starting in the second half of the year and continuing through the first half of 1965. These included the two above-mentioned launch failures plus GAMBIT 4013 which did not return any imagery and GAMBIT 4014 which suffered a battery explosion. GAMBIT 4019 did not return any imagery either. Eventually, it was determined that the culprit was an extra structure added to the [[Vandenberg Space Launch Complex 4|SLC-4W]] umbilical tower that sent resonant vibration through the Atlas-Agena stack at liftoff, jarring random components in the booster and/or spacecraft loose. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

== Cost == |

|||

| ⚫ | It was noted that the GAMBIT flights through the first half of 1964 had been mostly successful, but a string of malfunctions occurred starting in the second half of the year and continuing through the first half of 1965. These included the two above-mentioned launch failures plus GAMBIT 4013 which did not return any imagery and 4014 which suffered a battery explosion. 4019 did not return any imagery either. Eventually, it was determined that the culprit was an extra structure added to the SLC-4W umbilical tower that sent resonant vibration through the Atlas-Agena stack at liftoff, jarring random components in the booster and/or spacecraft loose. |

||

| ⚫ | The total cost of the 38 flight KH-7 program from FY1963 to FY1967, without non-recurring costs, and excluding five GAMBIT cameras sold to NASA, was US$651.4 million in 1963 dollars (inflation adjusted US$ {{Inflation|US|0.6514|1963|r=2}} billion present day).<ref name="NROGAMBITStory">{{cite web|url=http://www.nro.gov/foia/declass/GAMBHEX.html|title=The GAMBIT story|publisher=National Reconnaissance Office |date=June 1991|access-date=2011-09-25|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171007074824/http://www.nro.gov/foia/declass/GAMBHEX.html|archive-date=2017-10-07|url-status=dead}} {{PD-notice}}</ref> Non-recurring costs for industrial facilities, development, and one-time support amounted to 24.3% of the total program cost, or US$209.1 million. The resulting total program costs were US$860.5 million in 1963 dollars (inflation adjusted US$ {{Inflation|US|0.8605|1963|r=2}} billion present day).<ref name="NRO_AnalysisP206"/> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[KH-5 Argon|KH-5 ARGON]] |

|||

* [[KH-8 Gambit 3|KH-8 GAMBIT-3]] (concurrent operations) |

|||

* [[KH-9 Hexagon|KH-9 HEXAGON]] or "[[Big Bird (satellite)|Big Bird]]" |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[KH-11 KENNEN]], [[KH-11 KENNEN|KH-12]], [[KH-11 KENNEN|KH-13]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

== |

== See also == |

||

{{Portal|Spaceflight}}{{Commons category|KH-7 GAMBIT}} |

|||

| ⚫ | The total cost of the 38 flight KH-7 program from FY1963 to FY1967, without non-recurring costs, and excluding five |

||

* [[Satellite imagery]] |

|||

* [[Cold War]] |

|||

* [[First images of Earth from space]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Reflist|30em}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

*[[KH-5]] ARGON, [[KH-6]] Lanyard |

|||

*KH-7 and [[KH-8]] Gambit |

|||

*[[KH-9]] Hexagon "Big Bird" |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*[[KH-11]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

<references /> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

*[http://www.globalsecurity.org/ |

* [http://www.globalsecurity.org/intell/library/news/2002/nima-faq.htm NIMA 2002 Declassification FAQ] (mirror at GlobalSecurity.org) |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

==External links== |

== External links == |

||

* [http://eros.usgs.gov/#/Find_Data/Products_and_Data_Available/Declassified_Satellite_Imagery_-_2 US Geological Survey Satellite Images]: Photographic imagery from KH-7 Surveillance and KH-9 Mapping system (1963 to 1980) |

* [http://eros.usgs.gov/#/Find_Data/Products_and_Data_Available/Declassified_Satellite_Imagery_-_2 US Geological Survey Satellite Images]: Photographic imagery from KH-7 Surveillance and KH-9 Mapping system (1963 to 1980) |

||

{{NRO satellites}} |

{{NRO satellites}} |

||

{{US Reconnaissance Satellites}} |

{{US Reconnaissance Satellites}} |

||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kh-7 Gambit}} |

|||

[[Category:Surveillance]] |

[[Category:Surveillance]] |

||

[[Category:Reconnaissance satellites of the United States]] |

[[Category:Reconnaissance satellites of the United States]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Military equipment introduced in the 1960s]] |

||

Latest revision as of 01:03, 25 February 2024

BYEMAN codenamed GAMBIT, the KH-7 (Air Force Program 206) was a reconnaissance satellite used by the United States from July 1963 to June 1967. Like the older CORONA system, it acquired imagery intelligence by taking photographs and returning the undeveloped film to earth. It achieved a typical ground-resolution of 2 ft (0.61 m) to 3 ft (0.91 m).[1] Though most of the imagery from the KH-7 satellites was declassified in 2002, details of the satellite program (and the satellite's construction) remained classified until 2011.[2]

In its summary report following the conclusion of the program, the National Reconnaissance Office concluded that the GAMBIT program was considered highly successful in that it produced the first high-resolution satellite photography, 69.4% of the images having a resolution under 3 ft (0.91 m); its record of successful launches, orbits, and recoveries far surpassed the records of earlier systems; and it advanced the state of the art to the point where follow-on larger systems could be developed and flown successfully. The report also stated that Gambit had provided the intelligence community with the first high-resolution satellite photography of denied areas, the intelligence value of which was considered "extremely high".[1] In particular, its overall success stood in sharp contrast to the two first-generation photoreconnaissance programs, Corona, which suffered far too many malfunctions to achieve any consistent success, and SAMOS, which was essentially a complete failure with all satellites either being lost in launch mishaps or returning no usable imagery.

GAMBIT emerged in 1962 as an alternative to the less-than-successful CORONA and the completely failed SAMOS, although CORONA was not cancelled and in fact continued operating alongside the newer program into the early 1970s. While CORONA used the Thor-Agena launch vehicle family, GAMBIT would be launched on Atlas-Agena, the booster used for SAMOS. After the improved KH-8 GAMBIT-3 satellite was developed during 1965, operations shifted to the larger Titan IIIB launch vehicle.

System configuration

[edit]

Each GAMBIT-1 satellite was about 15 ft (4.6 m) long, 5 ft (1.5 m) wide, weighed about 1,154 lb (523 kg), and carried about 3,000 ft (910 m) of film.[3]

A feasibility study for the Geodetic Orbital Photographic Satellite System reveals three subsystems for U.S. optical reconnaissance satellites in the 1960s: the Orbital (or Orbiting) Control Vehicle (OCV), the Data Collection Module (DCM), and the Recovery Section (RS).[4] For the KH-7, the DCM is also called the Camera Optics Module (COM), and is integrated in the OCV, which has a length of 5.5 m (18 ft) and a diameter of 1.52 m (5 ft 0 in).[5]

Camera Optics Module

[edit]The Camera Optics Module of KH-7 consists of three cameras: a single strip camera, a stellar camera, and an index camera.

In the strip camera the ground image is reflected by a steerable flat mirror to a 1.21 m (4 ft 0 in) diameter stationary concave primary mirror. The primary mirror reflects the light through an opening in the flat mirror and through a Ross corrector. It took images of a 6.3° wide ground swath by exposing a 22 cm (8.7 in) wide moving portion of film through a small slit aperture.[6][7] The initial ground resolution of the satellite was 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in), but improved to 0.6 m (2 ft 0 in) by 1966. Each satellite weighed about 2,000 kg (4,400 lb), and returned a single film bucket per mission. The camera and film transport system were manufactured by Eastman Kodak Company.[7]

The index camera is a copy of cameras systems previously used in the KH-4 and KH-6 satellites, and takes exposures of Earth in direction of the vehicle roll position for attitude determination. The stellar camera takes images of star fields with a reseau grid being superimposed on the image plane.[6] The S/I camera was provided by Itek, and horizon sensors were provided by Barnes Engineering Co.[1]

Orbital Control Vehicle and Recovery Vehicle

[edit]

The primary contractor for the Orbital Control Vehicle and the Recovery Vehicle was General Electric.[1] Films were to be retrieved mid-air by a C-130 Hercules specially outfitted for that purpose.[8]

Mission

[edit]All KH-7 satellites were launched from Point Arguello, which became part of Vandenberg Air Force Base in July 1964. KH-7 satellites flew 38 missions, numbered 4001-4038, of which 34 returned film, and of these, 30 returned usable imagery. Mission duration was 1 to 8 days.[9] KH-7 satellites logged a total of almost 170 operational days in orbit.[1]

Functionality

[edit]

A high-resolution instrument, the KH-7 took detailed pictures of "hot spots" and most of its photographs are of Chinese and Soviet nuclear and missile installations, with smaller amounts of coverage of cities and harbors.[10] Most of the imagery from this camera, amounting to 19,000 images, was declassified in 2002 as a result of Executive order 12951,[11] the same order which declassified CORONA, and copies of the films were transferred to the U.S. Geological Survey's Earth Resources Observation Systems office.[12] Approximately 100 frames covering the state of Israel remain classified.[13]

In early 1964, the CIA toyed with the idea of using GAMBIT to photograph military installations in Cuba, but this was dismissed as unworkable as the satellites were primarily designed with higher-latitude Soviet territory in mind and because it would mean wasting an entire satellite on the Latin America-Caribbean area which had little else of interest to U.S. intelligence services. It was decided that U-2 spyplane flights were adequate to provide coverage of Cuban activity.

ELINT subsatellite

[edit]Mission 4009 included an ELINT P-11 subsatellite for radar monitoring, which was launched into a higher orbit.[14][15]

List of launches

[edit]

| Name | Mission No. | Launch Date | Alt. Name | NSSDC ID No. | Launch Vehicle | Perigee (km) | Apogee (km) | Inclination (deg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KH7-1 | 4001 | 1963-07-12 | OPS-1467 | 1963-028A | Atlas-Agena D | 164 | 164 | 95.4 |

| KH7-2 | 4002 | 1963-09-06 | OPS-1947 | 1963-036A | Atlas Agena D | 168 | 263 | 94.4 |

| KH7-3 | 4003 | 1963-10-25 | OPS-2196 | 1963-041A | Atlas Agena D | 144 | 332 | 99.1 |

| KH7-4 | 4004 | 1963-12-18 | OPS-2372 | 1963-051A | Atlas Agena D | 122 | 266 | 97.9 |

| KH7-5 | 4005 | 1964-02-25 | OPS-2423 | 1964-009A | Atlas Agena D | 173 | 190 | 95.7 |

| KH7-6 | 4006 | 1964-03-11 | OPS-3435 | 1964-012A | Atlas Agena D | 163 | 203 | 95.8 |

| KH7-7 | 4007 | 1964-04-23 | OPS-3743 | 1964-020A | Atlas Agena D | 150 | 366 | 103.6 |

| KH7-8 | 4008 | 1964-05-19 | OPS-3592 | 1964-024A | Atlas Agena D | 141 | 380 | 101.1 |

| KH7-9 | 4009 | 1964-07-06 | OPS-3684 | 1964-036A | Atlas Agena D | 121 | 346 | 92.9 |

| KH7-10 | 4010 | 1964-08-14 | OPS-3802 | 1964-045A | SLV-3 Agena D | 149 | 307 | 95.5 |

| KH7-11 | 4011 | 1964-09-23 | OPS-4262 | 1964-058A | SLV-3 Agena D | 145 | 303 | 92.9 |

| KH7-12 | 4012 | 1964-10-08 | OPS-4036 | 1964-F11 | SLV-3 Agena D | --- | --- | --- |

| KH7-13 | 4013 | 1964-10-23 | OPS-4384 | 1964-068A | Atlas Agena D | 139 | 271 | 88.6 |

| KH7-14 | 4014 | 1964-12-04 | OPS-4439 | 1964-079A | SLV-3 Agena D | 158 | 357 | 97 |

| KH7-15 | 4015 | 1965-01-23 | OPS-4703 | 1965-005A | SLV-3 Agena D | 146 | 291 | 102.5 |

| KH7-16 | 4016 | 1965-03-12 | OPS-4920 | 1965-019A | SLV-3 Agena D | 93 | 155 | 0.0 |

| KH7-17 | 4017 | 1965-04-28 | OPS-4983 | 1965-031A | SLV-3 Agena D | 180 | 259 | 95.7 |

| KH7-18 | 4018 | 1965-05-27 | OPS-5236 | 1965-041A | SLV-3 Agena D | 149 | 267 | 95.8 |

| KH7-19 | 4019 | 1965-06-25 | OPS-5501 | 1965-050B | SLV-3 Agena D | 151 | 283 | 107.6 |

| KH7-20 | 4020 | 1965-07-12 | OPS-5810 | 1965-F07 | SLV-3 Agena D | --- | --- | --- |

| KH7-21 | 4021 | 1965-08-03 | OPS-5698 | 1965-062A | SLV-3 Agena D | 149 | 307 | 107.5 |

| KH7-22 | 4022 | 1965-09-30 | OPS-7208 | 1965-076A | SLV-3 Agena D | 98 | 164 | 95.6 |

| KH7-23 | 4023 | 1965-11-08 | OPS-6232 | 1965-090B | SLV-3 Agena D | 145 | 277 | 93.9 |

| KH7-24 | 4024 | 1966-01-19 | OPS-7253 | 1966-002A | SLV-3 Agena D | 150 | 269 | 93.9 |

| KH7-25 | 4025 | 1966-02-15 | OPS-1184 | 1966-012A | SLV-3 Agena D | 148 | 293 | 96.5 |

| KH7-26 | 4026 | 1966-03-18 | OPS-0879 | 1966-022A | SLV-3 Agena D | 162 | 208 | 101 |

| KH7-27 | 4027 | 1966-04-19 | OPS-0910 | 1966-032A | SLV-3 Agena D | 139 | 312 | 116.9 |

| KH7-28 | 4028 | 1966-05-14 | OPS-1950 | 1966-039A | SLV-3 Agena D | 133 | 358 | 110.5 |

| KH7-29 | 4029 | 1966-06-03 | OPS-1577 | 1966-048A | SLV-3 Agena D | 143 | 288 | 86.9 |

| KH7-30 | 4030 | 1966-07-12 | OPS-1850 | 1966-062A | SLV-3 Agena D | 137 | 236 | 95.5 |

| KH7-31 | 4031 | 1966-08-16 | OPS-1832 | 1966-074A | SLV-3 Agena D | 146 | 358 | 93.3 |

| KH7-32 | 4032 | 1966-09-16 | OPS-1686 | 1966-083A | SLV-3 Agena D | 148 | 333 | 93.9 |

| KH7-33 | 4033 | 1966-10-12 | OPS-2055 | 1966-090A | SLV-3 Agena D | 155 | 287 | 91 |

| KH7-34 | 4034 | 1966-11-02 | OPS-2070 | 1966-098A | SLV-3 Agena D | 159 | 305 | 91 |

| KH7-35 | 4035 | 1966-12-05 | OPS-1890 | 1966-109A | SLV-3 Agena D | 137 | 388 | 104.6 |

| KH7-36 | 4036 | 1967-02-02 | OPS-4399 | 1967-007A | SLV-3 Agena D | 136 | 357 | 102.4 |

| KH7-37 | 4037 | 1967-05-22 | OPS-4321 | 1967-050A | SLV-3 Agena D | 135 | 293 | 91.5 |

| KH7-38 | 4038 | 1967-06-04 | OPS-4360 | 1967-055A | SLV-3 Agena D | 149 | 456 | 104.8 |

(NSSDC ID Numbers: See COSPAR)

History

[edit]

- Section source: Space Review[7]

GAMBIT marked the first use of next-generation launch vehicle systems as Convair and Lockheed, the builders of the Atlas-Agena booster, began introducing improved, standardized launchers to replace the multitude of customized variants used up to 1963, which caused endless mix ups, poor reliability, and mission failures. This followed a recommendation by the Lewis Spaceflight Center in Cleveland, Ohio that Atlas and Agena switch to one standard configuration for both NASA and Air Force launches, with uniform testing and checkout procedures, as well as improved materials and fabrication processes for the various hardware components in the boosters. The Agena D, a standardized Agena B, arrived first, with the uprated Atlas SLV-3 taking another year to fly. The first eight GAMBIT flown still used custom-modified Atlas D ICBM cores, with GAMBIT 4010 in August 1964 being the first use of the SLV-3. Afterwards, all GAMBIT used SLV-3s aside from 4013, which used the last old-style Atlas remaining in the inventory.

In early 1963, the GAMBIT program began with failures. On 11 May 1963, the first GAMBIT satellite sat atop Atlas-Agena 190D on SLC-4W at Vandenberg Air Force Base awaiting launch. An air bubble formed while loading LOX into the booster and as soon as propellant filling was stopped, the bubble damaged the fill/drain valve. This quickly caused both the LOX and helium pressure gas to escape from the tank, depressurizing the Atlas's balloon skin and causing the entire launch vehicle to crumple to the ground. The RP-1 tank ruptured and spilled its contents onto the pad. There was no fire or explosion, but the Agena sustained minor damage and the satellite a considerable amount as the cameras were crushed in by impact with the ground and had their lenses destroyed. The pad itself was undamaged except for a steel beam cracked by exposure to the super-chilled LOX, which was repaired in two days. Fortunately, the satellite on the booster was not the same one planned for the actual launch and the payload shroud had also remained in one piece, preventing any unauthorized parties from seeing the GAMBIT. Secrecy surrounding the program was strict and knowledge of GAMBIT limited only to those directly involved in the program. While the early CORONA and SAMOS flights had been merely billed to the public as scientific missions, it became increasingly difficult to explain why they failed to return any scientific data. In late 1961, President John F. Kennedy ordered a veil of secrecy placed around the photoreconnaissance program and by GAMBIT's debut in 1963, DoD announcements described no details other than the launching of a "classified payload".

The Agena was sent back to Lockheed for repairs and a different Atlas (vehicle 201D) was used, and the first successful GAMBIT mission was launched on 12 July 1963. The launch vehicle performed perfectly and inserted GAMBIT into polar orbit with a 189 km (117 mi) altitude. The Air Force designated this mission number 4001.

Aerospace Corporation recommended that, during GAMBIT's first flights, the Orbital Control Vehicle (OCV) should remain attached to the Agena. This was a proven successful process for other Agena tests; and whereas the OCV was not. This decision limited GAMBIT's functionality, meaning that photographs could only be taken of targets directly below the vehicle. Once the successful photographic phase of the mission 4002 was completed, the OCV and the Agena were separated and the reentry vehicle would come down into the ocean northwest of Hawaii. The re-entry vehicle was caught in mid-air with a C-130 Hercules aircraft using a modified version of the Fulton surface-to-air recovery system. The film canister was then immediately transported to Eastman Kodak's Hawkeye facility in Rochester, New York for processing.[16] The developed results was sent to US Air Force imagery research analysts in Washington, DC.

GAMBIT mission 4003, was launched on 25 October 1963. The film canister was again ejected successfully after the photographic phase and the capsule recovered by an aircraft. Other tests were carried out with the OCV.

GAMBIT mission 4004 was launched and its film canister recovered on 18 December 1963. Missions 4005 through 4007 were also successful.

In May 1964, mission 4008 suffered major problems when the Agena did an unexplained roll during the boost phase. Even with OCV system problems, the film canister was able to return some imagery.

A variety of problems occurred with many of the remaining missions including poor or no imagery. Many of these difficulties were caused by the unreliable wire recording system carried by the GAMBITs (tape recorders were not yet in widespread use in the mid-1960s). Two satellites ended up in the Pacific Ocean. The first of them was 4012, launched on October 8, 1964. The Agena engine shut down after 1.5 seconds of operation and the GAMBIT did not attain orbit. An investigation of the failure found that an electrical short occurred in an engine relay box, resulting in a cutoff signal being issued 0.4 seconds after ignition. As soon as the engine arming command was stopped at 1.5 seconds, the Agena propulsion system shut down. Examination of factory records for the Agena found that a pair of metal screws from a little-used terminal connector had broken off and disappeared to parts unknown; it was speculated that they landed somewhere as to cause a short. Telemetry data indicated otherwise entirely normal performance of all Agena systems. The other failure was 4020, launched on 12 July 1965 when the Atlas programmer accidentally issued simultaneous SECO and BECO commands, the resultant propulsion system shutdown sending the launch vehicle into the Pacific Ocean some 1,090 km (680 mi) downrange. The latter was the first flight witnessed by newly arrived Brig. Gen John L. Martin who replaced Maj. Gen Robert Greer as head of the KH-7 program. Martin cracked down and began demanding higher workmanship and quality standards. He is credited with having significantly improved the success rate of the program.

It was noted that the GAMBIT flights through the first half of 1964 had been mostly successful, but a string of malfunctions occurred starting in the second half of the year and continuing through the first half of 1965. These included the two above-mentioned launch failures plus GAMBIT 4013 which did not return any imagery and GAMBIT 4014 which suffered a battery explosion. GAMBIT 4019 did not return any imagery either. Eventually, it was determined that the culprit was an extra structure added to the SLC-4W umbilical tower that sent resonant vibration through the Atlas-Agena stack at liftoff, jarring random components in the booster and/or spacecraft loose.

The KH-7 GAMBIT was an overall success, even with some failures; thus providing National Reconnaissance Office and the President with quality intelligence collection. Following KH-7 projects had greatly improved major upgrades in the spacecraft and its camera systems.

Cost

[edit]The total cost of the 38 flight KH-7 program from FY1963 to FY1967, without non-recurring costs, and excluding five GAMBIT cameras sold to NASA, was US$651.4 million in 1963 dollars (inflation adjusted US$ 6.48 billion present day).[17] Non-recurring costs for industrial facilities, development, and one-time support amounted to 24.3% of the total program cost, or US$209.1 million. The resulting total program costs were US$860.5 million in 1963 dollars (inflation adjusted US$ 8.56 billion present day).[1]

Other U.S. imaging spy satellites

[edit]- CORONA series: KH-1, KH-2, KH-3, KH-4

- KH-5 ARGON

- KH-8 GAMBIT-3 (concurrent operations)

- KH-9 HEXAGON or "Big Bird"

- KH-10 DORIAN or Manned Orbital Laboratory

- KH-11 KENNEN, KH-12, KH-13

- SAMOS

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Summary Analysis of Program 206 (GAMBIT)" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. 29 August 1967. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Flashlights in the dark, The Space Review

- ^ "Declassified U.S. Spy Satellites from Cold War Land in Ohio". Space.com. 28 January 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ "Feasibility Study Final Report: Geodetic Optical Photographic Satellite System, Volume 2 Data Collection System" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. June 1966. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ Day, Dwayne A. (29 November 2010). "Black Apollo". thespacereview.com. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ^ a b "KH-7 Camera System- Part I". National Photographic Interpretation Center. July 1963. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ a b c Day, Dwayne A. (29 November 2010). "Ike's gambit: The development and operations of the KH-7 and KH-8 spy satellites". thespacereview.com. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- ^ "Key Hole (KH)". Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ "NRO review and redaction guide (2006 ed.)" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office.

- ^ NARA ARC Archived 1 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine database description of "Keyhole-7 (KH-7) Satellite Imagery, 07/01/1963 - 06/30/1967", accession number NN3-263-02-011

- ^ "National Archives Releases Recently Declassified Satellite Imagery". National Archives and Records Administration press release. 9 October 2002.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ edc.usgs.gov Archived 2007-06-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Historical imagery declassification". National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "1964-036B". NASA. 8 October 2010.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Day, Dwayne (27 April 2009). "Robotic ravens: American ferret satellite operations during the Cold War". The Space Review.

- ^ "Appendix C - Glossary of Code Words and Terms". National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide (Technical report). National Reconnaissance Office. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 November 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "The GAMBIT story". National Reconnaissance Office. June 1991. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Mark Wade (9 August 2003) KH-7 Encyclopedia Astronautica Accessed April 23, 2004

- KH-7 GAMBIT GlobalSecurity.org

- Gallery of KH-7 pictures at USGS

- NIMA 2002 Declassification FAQ (mirror at GlobalSecurity.org)

External links

[edit]- US Geological Survey Satellite Images: Photographic imagery from KH-7 Surveillance and KH-9 Mapping system (1963 to 1980)