Venus in fiction: Difference between revisions

Made the part about Venus in Destiny more detailed. |

TompaDompa (talk | contribs) m Stray line break. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Depictions of the planet}} |

|||

[[File:Planetstories.jpg|Planet Stories Winter 1939|thumb]]'''Fictional representations of [[Venus]]''' have existed since the 19th century. Its impenetrable cloud cover gave [[science fiction]] writers free rein to speculate on conditions at its surface; all the more so when early observations showed that not only was it very similar in size to Earth, it possessed a substantial atmosphere. Closer to the Sun than Earth, the planet was frequently depicted as warmer, but still [[Planetary habitability|habitable]] by humans.<ref name="miller"> |

|||

{{About|the planet|the goddess Venus in fiction|Venus (mythology)#Mythology and literature}} |

|||

{{Citation |

|||

{{Featured article}} |

|||

| first=Ron | last=Miller | title=Venus |

|||

[[File:Planetstories.jpg|Venus appears in many [[pulp science fiction]] stories. Seen here is the winter 1939 cover of ''[[Planet Stories]]'', featuring "The Golden Amazons of Venus".|thumb|alt=Refer to caption]] |

|||

| publisher=Twenty-First Century Books | date=2003 |

|||

The planet [[Venus]] has been used as a [[Setting (narrative)|setting]] in fiction since before the 19th century. Its [[Atmosphere of Venus|opaque cloud cover]] gave [[science fiction]] writers free rein to speculate on conditions at its surface—a "cosmic [[Rorschach test]]", in the words of science fiction author Stephen L. Gillett. The planet was often depicted as warmer than [[Earth]] but still [[Planetary habitability|habitable]] by humans. Depictions of Venus as a lush, verdant paradise, an oceanic planet, or fetid swampland, often inhabited by [[dinosaur]]-like beasts or other monsters, became common in early [[Pulp magazine|pulp]] science fiction, particularly between the 1930s and 1950s. Some other stories portrayed it as a desert, or invented more exotic settings. The absence of a common vision resulted in Venus not developing a coherent fictional mythology, in contrast to the image of [[Mars in fiction]]. |

|||

| isbn=0-7613-2359-7 | page=12 }}</ref> The [[genre]] reached its peak between the 1930s and 1950s, at a time when science had revealed some aspects of Venus, but not yet the harsh reality of its surface conditions. |

|||

When included, the native sentient inhabitants, Venusians, were often portrayed as gentle, ethereal and beautiful. The planet's associations with the [[Venus (mythology)|Roman goddess Venus]] and femininity in general is reflected in many works' portrayals of Venusians. Depictions of Venusian societies have varied both in level of development and type of governance. In addition to humans visiting Venus, several stories feature Venusians coming to Earth—most often to enlighten humanity, but occasionally for warlike purposes. |

|||

==Swamp== |

|||

In 1918, chemist and [[List of Nobel laureates in Chemistry|Nobel Prize winner]] [[Svante Arrhenius]], deciding that Venus' cloud cover was necessarily water, decreed in ''The Destinies of the Stars'' that "A very great part of the surface of Venus is no doubt covered with swamps" and compared Venus' humidity to the tropical [[rain forest]]s of the [[Congo Basin|Congo]]. Because of what he assumed was constantly uniform climatic conditions all over the planet, the life of Venus lived under very stable conditions and didn't have to adapt to changing environments like life on Earth. As a result of this lack of selection pressure, it would be covered in prehistoric swamps. Venus thus became, until the early 1960s, a place for science fiction writers to place all manner of unusual life forms, from quasi-dinosaurs to intelligent [[carnivorous]] plants. Comparisons often referred to Earth in the [[Carboniferous]] period. |

|||

From the mid-20th century on, as the reality of Venus's harsh [[Surface of Venus|surface conditions]] became known, the early [[wikt:trope|tropes]] of adventures in Venusian tropics mostly gave way to more realistic stories. The planet became portrayed instead as a hostile, toxic inferno, with stories changing focus to topics of the planet's [[Colonization of Venus|colonization]] and [[terraforming of Venus|terraforming]], although the vision of tropical Venus is occasionally revisited in intentionally [[Retro style|retro]] stories. |

|||

In the 1930s, [[Edgar Rice Burroughs]] wrote the "[[sword and planet|sword-and-planet]]" style "Venus series," set on a fictionalized version of Venus known as [[Amtor]]. In [[Olaf Stapledon]]’s 1930 science fiction novel ''[[Last and First Men]]'', humanity is forced to migrate to Venus hundreds of millions of years in the future when astronomical calculations show that the [[Moon]] will soon spiral down to crash into Earth. Stapledon describes Venus as being mostly ocean and having fierce [[tropical storm]]s. The Venus of [[Robert A. Heinlein|Robert Heinlein]]'s [[Future History (novel)|Future History]] series and [[Henry Kuttner]]'s ''Fury'' resembled Arrhenius' vision of Venus. [[Ray Bradbury]]'s short stories "[[The Long Rain]]" and "[[All Summer in a Day]]" also depicted Venus as a habitable planet with incessant rain. In Germany, the ''[[Perry Rhodan]]'' novels used the vision of Venus as a jungle world. Works such as [[C. S. Lewis]]'s 1943 ''[[Perelandra]]'' and [[Isaac Asimov]]'s 1954 ''[[Lucky Starr and the Oceans of Venus]]'' drew from a vision of a [[Cambrian]]-like Venus covered by a near-planet-wide ocean filled with exotic aquatic life.<ref name=miller/> |

|||

== Early depictions == |

|||

==Desert== |

|||

<imagemap> |

|||

Descriptions of a hot, humid planet were already considered scientifically doubtful as early as 1922, when [[Charles Edward St. John]] and [[Seth B. Nicholson]], failing to detect the [[spectroscopic]] signs of oxygen or water in the atmosphere, proposed a dusty, windy desert Venus. The model of a planet covered in clouds of polymeric [[formaldehyde]] dust was never as popular as a swamp or jungle, but featured in several notable stories, like [[Poul Anderson]]'s ''The Big Rain'' (1954), and [[Frederik Pohl]] and [[Cyril M. Kornbluth]]'s novel ''[[The Space Merchants]]'' (1953). |

|||

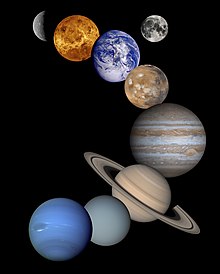

File:Solar system.jpg|alt=A photomontage of the eight planets and the Moon|thumb|Some early depictions of Venus in fiction were part of tours of the Solar System. Clicking on a planet leads to the article about its depiction in fiction. |

|||

===[[Venera]] program=== |

|||

circle 1250 4700 650 [[Neptune in fiction]] |

|||

{{main|Venera}} |

|||

circle 2150 4505 525 [[Uranus in fiction]] |

|||

However, the more optimistic notions of Venus were not definitively disproved until the first space probes were sent to Venus. Data from the fly-by of ''[[Mariner 2]]'' (December 1962) as well as radio astronomy from the same time pointed to a hot, dry Venus, but as late as 1964, Soviet scientists were still designing Venus probes for the possibility of landing in liquid water.<ref>[http://www.mentallandscape.com/V_OKB1.htm Inventing The Interplanetary Probe]</ref> It was not until ''[[Venera 4]]'' and ''[[Mariner 5]]'' reached Venus (October 18–19, 1967) that it was confirmed beyond doubt that Venus was actually an extremely hot, dry desert with a lot of [[sulfuric acid]] in its atmosphere. Stories about wet tropical Venus vanished at that point,<ref>{{Citation |

|||

circle 2890 3960 610 [[Saturn in fiction]] |

|||

| first=Steven | last=Dick | date=2001 |

|||

circle 3450 2880 790 [[Jupiter in fiction]] |

|||

| title=Life on Other Worlds: The 20th-Century Extraterrestrial Life Debate | page=43 |

|||

circle 3015 1770 460 [[Mars in fiction]] |

|||

| publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |

|||

circle 2370 1150 520 [[Earth in science fiction]] |

|||

| isbn=0-521-79912-0 }}</ref> except for intentionally nostalgic "[[retro-futurism|retro-sf]]", a passing which [[Brian Aldiss]] and [[Harry Harrison (writer)|Harry Harrison]] marked with their 1968 anthology ''[[Farewell Fantastic Venus]]''. |

|||

circle 3165 590 280 [[Moon in science fiction]] |

|||

circle 1570 785 475 [[Venus in fiction]] |

|||

circle 990 530 320 [[Mercury in fiction]] |

|||

</imagemap> |

|||

The earliest use of the planet [[Venus]] as the primary [[Setting (narrative)|setting]] in a work of fiction was ''[[Voyage à Venus]]'' (''Voyage to Venus'', 1865) by {{Ill|Achille Eyraud|fr}},<ref name="SFEVenus" /><ref name="CloudedJudgments" />{{Rp|page=6}} though it had appeared centuries earlier in works depicting multiple locations in the [[Solar System]] such as [[Athanasius Kircher]]'s ''[[Itinerarium exstaticum|Itinerarium Exstaticum]]'' (1656) and [[Emanuel Swedenborg]]'s ''[[The Earths in Our Solar System]]'' (1758).<ref name="SFEVenus">{{Cite encyclopedia |year=2022 |title=Venus |encyclopedia=[[The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction]] |url=https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/venus |access-date=2023-06-26 |edition=4th |author1-last=Stableford |author1-first=Brian |author1-link=Brian Stableford |author2-last=Langford |author2-first=David |author2-link=David Langford |editor1-last=Clute |editor1-first=John |editor1-link=John Clute |editor2-last=Langford |editor2-first=David |editor2-link=David Langford |editor3-last=Sleight |editor3-first=Graham |editor3-link=Graham Sleight}}</ref> [[Science fiction scholar]] [[Gary Westfahl]] considers the mention of the "[[Morning Star (disambiguation)|Morning Star]]" in the second-century work ''[[True History]]'' by [[Lucian of Samosata]] to be the first appearance of Venus—or any other planet—in the genre.<ref name="Westfahl2022Venus">{{Cite book |last=Westfahl |first=Gary |title=The Stuff of Science Fiction: Hardware, Settings, Characters |date=2022 |publisher=McFarland |isbn=978-1-4766-8659-2 |language=en |chapter=Venus—Venus of Dreams ... and Nightmares: Changing Images of Earth's Sister Planet |author-link=Gary Westfahl |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=q7WREAAAQBAJ&pg=PA164}}</ref>{{Rp|page=164}} |

|||

Venus has [[Atmosphere of Venus|a thick layer of clouds]] that prevents [[Telescope|telescopic]] observation of the surface, which gave writers free rein to imagine any kind of world below until [[Venus exploration]] probes revealed the true conditions in the 1960s—[[Stephen L. Gillett]] describes the situation as a "cosmic [[Rorschach test]]".<ref name="SFEVenus" /><ref name="Liptak" /><ref name="GreenwoodVenus">{{Cite book |author-last=Gillett |author-first=Stephen L. |title=[[The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders]] |date=2005 |publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group |isbn=978-0-313-32951-7 |editor-last=Westfahl |editor-first=Gary |editor-link=Gary Westfahl |pages= |language=en |chapter=Venus |author-link= |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/greenwoodencyclo0002unse_f3t4/page/860/mode/2up}}</ref>{{rp|861}} Venus thus became a popular setting in [[History of science fiction|early science fiction]], but that same versatility meant that it did not develop a counterpart to the image of [[Mars in fiction]] made popular by [[Percival Lowell]] around the turn of the century—with supposed [[Martian canals]] and a civilization that built them—and it never reached the same level of popularity.<ref name="SFEVenus" /><ref name="Westfahl2022Venus" />{{Rp|page=164–165}}<ref name="MillerVenus">{{Cite book |last=Miller |first=Ron |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7w-ovrb7yk0C&pg=PA12 |title=Venus |date=2002 |publisher=Twenty-First Century Books |isbn=978-0-7613-2359-4 |language=en |author-link=Ron Miller (artist and author)}}</ref>{{Rp|page=12}} On the subject, Westfahl writes that while [[Mars]] has a distinctive body of major works such as [[H. G. Wells]]'s ''[[The War of the Worlds]]'' (1897) and [[Ray Bradbury]]'s [[fix-up]] novel ''[[The Martian Chronicles]]'' (1950), Venus largely lacks a corresponding canon.<ref name="Westfahl2022Venus" />{{Rp|page=165–166}} |

|||

As scientific knowledge of Venus advanced, so science fiction authors endeavored to keep pace, particularly by conjecturing human attempts to [[Terraforming of Venus|terraform Venus]].<ref> |

|||

{{Citation |

|||

| first=David | last=Seed | date=2005 |

|||

| title=A Companion to Science Fiction | pages=134–135 | publisher=Blackwell Publishing | isbn = 1-4051-1218-2 }}</ref> For instance [[James E. Gunn (writer)|James E. Gunn]]'s 1955 novella "The Naked Sky”<ref>Startling Stories Fll 1955</ref> (retitled "The Joy Ride") starts on a partial terraformed Venus where the colonists live underground to get away from the still-deadly atmosphere. [[Arthur C. Clarke]]'s 1997 novel ''[[3001: The Final Odyssey]]'', for example, postulates humans lowering Venus's temperature by steering [[comet]]ary fragments to impact its surface. A [[terraform]]ed Venus is the setting for a number of diverse works of fiction that have included ''[[Star Trek]]'', ''[[Exosquad]]'', the German language ''[[Mark Brandis]]'' series and the manga ''[[Venus Wars]]''. In [[L. Neil Smith|L. Neil Smith's]] [[The Probability Broach|Gallatin Universe]] novel ''[[The Venus Belt]]'', Venus was broken apart by a massive man-made projectile to form a second asteroid belt suitable for commercial exploitation. |

|||

{{Quote box| quote = A [[Mercury in fiction#Tidal locking|clement twilight zone on a synchronously rotating Mercury]], a swamp-and-jungle Venus, and a [[Mars in fiction#Canals|canal-infested Mars]], while all classic science-fiction devices, are all, in fact, based upon earlier misapprehensions by planetary scientists.| author = [[Carl Sagan]], 1978<ref name="sagan19780528" />| width = 400px}} |

|||

==Stories set on Venus== |

|||

One of the many visions was of a [[Tidal locking|tidally locked]] Venus with half of the planet always exposed to the Sun and the other half in perpetual darkness—as was widely believed to be the case with [[Mercury (planet)|Mercury]] at the time. This concept was introduced by Italian astronomer [[Giovanni Schiaparelli]] in 1880 and appeared in [[Garrett P. Serviss]]'s ''[[A Columbus of Space]]'' (1909) and [[Garret Smith]]'s ''[[Between Worlds (novel)|Between Worlds]]'' (1919), among others.<ref name="CloudedJudgments">{{Cite book |last=Aldiss |first=Brian |title=[[Farewell, Fantastic Venus]]! A History of the Planet Venus in Fact and Fiction |date=1968 |publisher=Macdonald & Co |isbn=0-356-02466-0 |editor-last=Aldiss |editor-first=Brian |editor-link=Brian Aldiss |location=London |chapter=Clouded Judgments |oclc=34972 |author-link=Brian Aldiss |editor-last2=Harrison |editor-first2=Harry |editor-link2=Harry Harrison (writer)}}</ref>{{Rp|page=8}}<ref name="Westfahl2022Venus" />{{Rp|page=169}}<ref name="Westfahl2021VenusAndVenusians" />{{Rp|page=671}}<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Cattermole |first1=Peter John |title=Atlas of Venus |last2=Moore |first2=Patrick |date=1997 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-49652-0 |language=en |chapter=Appendix 4: Estimated Rotation Period of Venus |author-link2=Patrick Moore |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=R3hsaELH9bUC&pg=PA111}}</ref>{{Rp|page=111}} A common assumption was that the Venusian clouds were made of water, as clouds on Earth are, and consequently the planet was most often portrayed as having a wet climate.<ref name="Westfahl2022Venus" />{{Rp|page=166}}<ref name="Westfahl2021VenusAndVenusians" />{{Rp|page=671}}<ref name="ScienceFactAndScienceFiction">{{Cite book |last=Stableford |first=Brian |title=[[Science Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopedia]] |date=2006 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-0-415-97460-8 |language=en |chapter=Venus |author-link=Brian Stableford |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uefwmdROKTAC&pg=PA547}}</ref>{{Rp|page=547}} This sometimes meant vast oceans, but more commonly swamps and/or jungles.<ref name="Westfahl2022Venus" />{{Rp|page=167}} Another influential idea was the [[History of Solar System formation and evolution hypotheses|early version]] of the [[nebular hypothesis]] of [[Solar system formation|Solar System formation]] which held that the planets are older the further from the Sun they are, meaning that Venus should be younger than Earth and might resemble earlier periods in Earth's history such as the [[Carboniferous]].<ref name="Westfahl2022Venus" />{{Rp|page=166}}<ref name="GreenwoodVenus" />{{rp|860}} Scientist [[Svante Arrhenius]] popularized the idea of Venus being swamp-covered with flora and fauna similar to that of prehistoric Earth in his non-fiction book ''[[The Destinies of the Stars]]'' (1918). Whereas Arrhenius assumed that Venus had unchanging climatic conditions that were similar all over the planet and concluded that a lack of [[adaptation]] to environmental variability would result only in primitive lifeforms, later writers often included various [[megafauna]].<ref name="Westfahl2022Venus" />{{Rp|page=166}}<ref name="Westfahl2021VenusAndVenusians" />{{Rp|page=671}}<ref name="Dozois">{{Cite book |last=Dozois |first=Gardner |title=[[Old Venus]]: A Collection of Stories |date=2015 |publisher=Random House Publishing Group |isbn=978-0-8041-7985-0 |editor-last=Martin |editor-first=George R. R. |editor-link=George R. R. Martin |language=en |chapter=Return to Venusport |author-link=Gardner Dozois |editor-last2=Dozois |editor-first2=Gardner |editor-link2=Gardner Dozois |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/oldvenus0000unse_j7e9/page/n13/mode/2up <!-- Also available at https://books.google.com/books?id=oJBoBAAAQBAJ&pg=PT8, though without proper pagination -->}}</ref>{{rp|xii–xiii}} |

|||

The following list divides stories about Venus into those which reflect the older view of Venus, and the more accurate ones reflecting Venus science since the mid-1960s. |

|||

=== |

=== Jungle and swamp === |

||

Early treatments of a Venus covered in swamps and jungles are found in [[Gustavus W. Pope]]'s ''[[Journey to Venus]]'' (1895), [[Fred T. Jane]]'s ''[[To Venus in Five Seconds]]'' (1897), and [[Maurice Baring]]'s "[[Venus (Baring short story)|Venus]]" (1909).<ref name="ScienceFactAndScienceFiction" />{{Rp|page=547}} Following its popularization by Arrhenius, the portrayal of the Venusian landscape as dominated by jungles and swamps recurred frequently in other works of fiction; in particular, [[Brian Stableford]] says in ''[[Science Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopedia]]'' that it became "a staple of [[Pulp magazine|pulp]] science fiction imagery".<ref name="ScienceFactAndScienceFiction" />{{Rp|page=547}} [[Clark Ashton Smith]]'s "[[The Immeasurable Horror]]" (1931) and [[Lester del Rey]]'s "[[The Luck of Ignatz]]" (1939) depict threatening Venusian creatures in a swamp-and-jungle climate.<ref name="Westfahl2022Venus" />{{Rp|page=167–168}} "[[In the Walls of Eryx]]" (1936) by [[H. P. Lovecraft]] and [[Kenneth Sterling]] features an invisible maze on a jungle Venus.<ref name="VaasZivilisationenAufDerNachbarplanet" /><ref>{{Cite book |last=Bleiler |first=E. F. |title=Science Fiction Writers: Critical Studies of the Major Authors from the Early Nineteenth Century to the Present Day |date=1999 |publisher=[[Charles Scribner's Sons]] |isbn=0-684-80593-6 |editor-last=Bleiler |editor-first=Richard |editor-link=Richard Bleiler |edition=2nd |location=New York |chapter=H. P. Lovecraft |oclc=40460120 |author-link=E. F. Bleiler |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/sciencefictionwr0000unse/page/483/mode/2up}}</ref>{{Rp|page=483}} |

|||

[[File:An Earth Man on Venus 78545.JPG|thumb|right|Cover of 1950 Avon comic adaptation of The Radio Man]] |

|||

*Achille Eyraud's ''Voyage to Venus'' (1865), where humans travels to Venus in a spaceship propelled by a reaction motor.<ref>[http://www.koapp.narod.ru/english/encicl/book2v.htm SF&F encyclopedia (V-V)]</ref><ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=2nyDsGkPqocC&pg=PA3&lpg=PA3&dq=%22Eyraud's+Voyage+a+Venus%22&source=bl&ots=fWzD4B45R7&sig=K1QMzSft23m43vNXUJrykz-g9-M&hl=en&sa=X&ei=h0ImUpfLG4SRswaG7oHwCQ&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=%22Eyraud's%20Voyage%20a%20Venus%22&f=false Rockets Into Space]</ref> |

|||

*The anonymous ''[[The Great Romance]]'' (1881) is another early SF account of a trip to Venus. |

|||

*Gustavus W. Pope's ''[[Journey to Venus]]'' (1895) provides a flight, by Earthmen and Martians, to a Venus of dinosaurian monsters. |

|||

*In [[John Munro (author)|John Munro]]'s ''A Trip to Venus'' (1897), the narrator, an engineer, an astronomer and his daughter travel by a newly invented flying machine to Venus and Mercury. On Venus they find a Utopian civilization, and the narrator falls in love. |

|||

*[[Fred T. Jane]]'s ''[[To Venus in Five Seconds]]'' (1897) is a [[satire]] and [[parody]] of the popular fiction of its era; it features Venusian natives that blend the characteristics of elephants and horse-flies. |

|||

*[[Garrett P. Serviss]]' '' A Columbus of Space'' (1909) is the story of Edmund Stonewall, an inventor, who travels to Venus in an atomic powered spaceship. He discovers that the planet is inhabited by two species, both of which are telepathic. The first is a cave dwelling ape-like tribe with black heads and white bodies. The second are humanoids that look like tall, blonde Englishmen who live in a floating city suspended by balloons. |

|||

*[[Roger Sherman Hoar|Ralph Milne Farley's]] ''Radio Man'' series (1924-1955). In Farley's stories, where a man from earth is teleported to Venus, the planet has boiling oceans but has habitable landmasses populated by a humanoid race with blonde hair and blue eyes, and a pair of [[Vestigiality|vestigial]] wings on their back. Being both deaf and earless, they communicate through antenna on their heads.<ref>[http://www.erbzine.com/mag15/1514.html Radio Free Venus - Ralph Milne Farley's Radio Series]</ref> |

|||

**''[[The Radio Man]]'' (1924) |

|||

**''The Radio Beasts'' (1925) |

|||

**''The Radio Planet'' (1926) |

|||

**''The Radio Menace'' (1930) |

|||

**''The Radio Minds of Mars'' (1955) |

|||

* In [[Otis Adelbert Kline]]'s ''Planet of Peril'' (written 1922, published 1929), hero Robert Grandon is telepathically transported into the mind of a Venusian. This was one of the first science fiction stories to send a character particularly to Venus. It was followed by two sequels set on Venus (''The Prince of Peril'', 1930 and ''[[The Port of Peril]]'', 1932). These were weak imitations of [[Edgar Rice Burroughs]]' [[Barsoom|Mars novels]]. |

|||

* In [[Olaf Stapledon]]'s ''[[Last and First Men]]'' (1930), humans fleeing a dying Earth perpetrate [[genocide]] on Venus and completely exterminate its aquatic intelligent species. Their descendants many millennia later live in the planet's oceanic idyll and biologically evolve into bird-men having the power of flight. |

|||

* In [[John W. Campbell]]'s ''The Black Star Passes'' (1930, republished 1953), Venus is the home of an advanced civilization that creates enormous aircraft, among other things. There are two large continents on Venus called Lanor and Kaxor, one centered on each pole. |

|||

* In [[Edgar Rice Burroughs]]' [[Amtor|Venus series]] (1934–1946) Venus is a tropical world shielded from the heat of the sun by a perpetual cloud cover, home to a humanoid race whose technology is advanced in some respects and retarded in others. The native name is Amtor, and the portion depicted, largely confined to the southern hemisphere's temperate zone, is primarily oceanic, but includes two forested continents and a number of large islands. The series features hero Carson Napier, who engages in derring-do and the rescue of princesses amid vicious political struggles.<ref>[http://www.tarzan.com/worlds/amtor.html]</ref> |

|||

* In [[Stanley G. Weinbaum]]'s "[[Parasite Planet]]" and "[[The Lotus Eaters (Weinbaum)|The Lotus Eaters]]" (1935), Venus is tidally locked, with a barren sunside, a tropical twilight zone inhabited by parasitic life-forms, and a frozen nightside. |

|||

* [[H. P. Lovecraft]] and Kenneth Sterling's "[[In the Walls of Eryx]]" (1939) takes place on a muddy jungle Venus inhabited by lizard-men. (Unlike many other Lovecraft stories, it is not part of the [[Cthulhu Mythos]].) |

|||

* In [[Leigh Brackett]]'s short stories (1940–1949), including "Lorelei of the Red Mist", "The Moon That Vanished", and "Enchantress of Venus", [[Venus in the fiction of Leigh Brackett|Venus]] is warm, wet, and cloudy; most of its surface is ocean or low-lying swamp, both of which are filled with exotic forms of life, including a large number of alien species. |

|||

* In [[Robert A. Heinlein]]'s ''[[Future History (novel)|Future History]]'' series, Venus is portrayed as a world covered entirely in hot, steamy swamps, which are used to explain the constant, unyielding cloud cover. Humans can live on Venus, but they find it very uncomfortable, and the few who settle there mainly are there for growing and harvesting local crops for export. The native Venusians are a primitive, yet peaceful people who tolerate humanity's presence and colonization. |

|||

** ''[[Logic of Empire]]'' (1941). An Earthman is enslaved on Venus. |

|||

** ''[[Space Cadet]]'' (1948). Depicts a confrontation with ordinarily peaceful Venusians who inhabit a steamy, jungle-covered Venus. |

|||

** ''[[Between Planets]]'' (1951). A war for independence erupts between Earth and colonists and natives of Venus. The protagonist joins the Venus side. |

|||

** ''[[Podkayne of Mars]]'' (1962), a spaceliner en route from Mars to Earth makes a stop at Venus, which is depicted as a latter-day [[Las Vegas Strip|Las Vegas]] gone ultra-capitalistic, controlled by a single corporation. Almost the last half of the novel takes place on Venus. |

|||

* In [[C. S. Lewis]]'s ''[[Perelandra]]'' (1943), the second book in science fiction [[Space Trilogy]], the scene is the planet Venus, described as a sort of paradise, where fabulous animals live, along with the King and Queen, Green humanoids. In Lewis' description the whole surface of Venus is covered by ocean upon which are free-floating rafts of vegetation large enough to support animal life; with the exception of a single mountainous land-mass. Much like [[Maxwell Montes]]. The main character, [[Elwin Ransom]] acts as Maleldil's emissary in a second "[[Garden of Eden]]" situation. The Oyarsa of Venus is feminine, like the Classical goddess Venus. |

|||

* In [[Henry Kuttner]] and [[Catherine Lucille Moore|C. L. Moore]]'s classic of military sci-fi, ''Clash by Night'' (1943), humanity in the Fourth Millennium, after the destruction of Earth due to atomic energy, found refuge on Venus within submarine city-states, which hired mercenary companies and their battle fleets to fight their wars on the waters of the planet, away from civilians. The mainland is - apart from the mercenary strongholds - uninhabitable, covered by a dense and lethal jungle dominated by poisonous flora and fauna, including huge and fierce reptiles. In the novel ''[[Fury (Kuttner)|Fury]]'' (1947), set several centuries later, the mercenary companies have disappeared, and the now united underwater Reserves are dominated by an elite minority of rich Immortals. Human civilization is in full stagnation, and would face extinction within a few centuries, when the protagonist of the novel promotes a "crusade" to colonize the surface. In [[David Drake]]'s ''Seas of Venus'' the author revisits the Venus of ''Fury'' for two more adventures of the mercenary companies. |

|||

* In C.L. Moore's ''[[Northwest Smith]]'' stories, Smith occasionally visits a dark, swampy, decadent Venus (whose pale women are described as the most beautiful in the system). His best friend is the equally-amoral Venusian ''Yarol''. |

|||

* "[[Venus and the Seven Sexes]]" (1947) by [[William Tenn]]. |

|||

* In [[A. E. van Vogt]]'s ''[[The World of Null-A]]'' (1948) and ''[[The Pawns of Null-A]]'' (1956), Venus in the far future is [[terraformed]] into a paradise where immigration from Earth is strictly controlled. The trees are all giants, with massive leaves to hold back the torrential rains. |

|||

* In [[Jack Williamson]]'s ''[[Seetee Ship]]'' (1949) and ''[[Seetee Shock]]'' (1950), Venus is colonized by China, in cooperation with some colonists from Japan and other [[East Asian]] countries, who all find the climate of Venus (as conceived here) congenial for the growing of rice. The Chinese transfer the seat of their government to Venus after the United States builds a nuclear base on the [[Moon]], which enables the Americans to dominate the whole of Earth. The Asian-colonized Venus is one of the main powers contending for control of the mineral wealth of the [[Asteroid Belt]]. |

|||

* In [[Stanisław Lem]]'s book ''[[Astronauci]]'' (''The Astronauts'') (1951) it is a post-apocalyptic dead world (see film section for details). |

|||

* One of the [[Tom Corbett, Space Cadet]] books, "[[The Revolt on Venus]]" (1954) depicts a jungle-covered world with huge trees and large plantations. |

|||

* In [[Ray Bradbury]]'s "Death-by-Rain" (1950), a short story later published as "[[The Long Rain]]" in the 1951 short story collection ''[[The Illustrated Man]]'', four astronauts search for a man-made shelter, called a "sun dome", on the surface of Venus, to escape the constant rain. In a film adaptation, the planet is not identified as Venus. |

|||

* In [[Frederik Pohl]] and [[C.M. Kornbluth]]'s ''[[The Space Merchants]]'' (1953), Venus is portrayed as a steamy jungle world, on which a former executive is enslaved on a ''[[Chlorella]]'' plantation. |

|||

* In ''[[The Duplicated Man]]'' (1953) by [[James Blish]] and [[Robert Lowndes]], Earth is at war with Venus, and a pacifist scientist discovers a human duplication machine. But it only makes five copies at a time. If he can duplicate the right world leaders, he might be able to bring about peace. |

|||

* In [[Isaac Asimov]]'s ''[[Lucky Starr and the Oceans of Venus]]'' (1954), a juvenile novel, Venus is covered by a worldwide ocean with human colonies located on the seafloor. |

|||

* In Ray Bradbury's "[[All Summer in a Day]]" (1954), a short story later published in the 1959 collection ''[[A Medicine for Melancholy]]'', the sun is seen for only an hour every seven years in a colony on Venus where it is constantly raining. |

|||

* In [[Poul Anderson]]'s 1954 novella ''The Big Rain'' published in the 1981 collection ''[[The Psychotechnic League]]'', Venus is a harsh, waterless world under a brutal dictatorship. |

|||

* In [[Boris and Arkady Strugatsky]]'s ''[[Noon Universe]]'' stories, Venus is depicted as an extremely harsh planet covered by strange [[flora (plants)|flora]] and [[fauna (animals)|fauna]] but also very rich in [[mineral]]s and [[heavy metals]]. ''[[The Land of Crimson Clouds]]'' (Russian: ''Strana Bagrovykh Tuch'', 1959) describes the first successful manned mission to Venus, although a full-scaled colonization of the planet was not initiated until much later (in 2119; see ''[[Noon: 22nd Century]]''). |

|||

* In [[Philippe Curval]]'s 1960 novel ''Les Fleurs de Vénus'', Venus is a luxuriant (but deadly toxic at night) paradise inhabited by peaceful ''noble savages''. The Humans tried to colonize it but with little success. |

|||

* In some of the early [[Perry Rhodan]] stories (1961–1962), Venus is a jungle world inhabited by dinosaurs and other monstrous creatures and is the site of a huge, ancient alien fortress. |

|||

* [[Roger Zelazny]]'s ''[[The Doors of His Face, The Lamps of His Mouth]]'' (1965) describes an oceanic Venus complete with monstrous fish-like creatures is invoked, despite then-recent evidence contradicting this image of Venus. |

|||

* ''[[Farewell Fantastic Venus]]'' (1968; abridged paperback as ''All About Venus'') is an anthology of short stories, excerpts and essays from both old and new versions of the planet. |

|||

* [[S. M. Stirling]]'s ''[[The Sky People]]'' (2006) restores the traditional oceanic and Mesozoic Venus by postulating an alternate universe in which Venus was [[Terraforming|terraformed]] and given a shorter solar day 200 million years ago by an unknown alien intelligence; Venus was then populated with wave after wave of terrestrial species ranging from dinosaurs to [[Neanderthal]]s and several different populations of humans. Discovery of the Earthlike conditions prevailing on Venus led to a sped-up Space-Race and Terran settlements by the second half of the 20th century. |

|||

* [[Stephen King]]'s short story "[[People, Places and Things|The Cursed Expedition]]" detailed a Venus that was alive and ate starships. |

|||

* The 2015 anthology ''[[Old Venus]]'' contains modern stories set on retro versions of Venus. |

|||

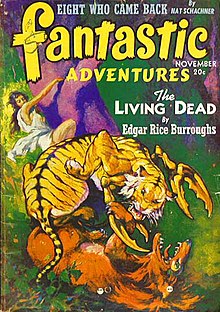

[[File:Fantastic_adventures_194111.jpg|thumb|Cover of ''[[Fantastic Adventures]]'', November 1941, featuring the ''[[Amtor]]'' story "The Living Dead" from Burroughs's ''[[Escape on Venus]]''|alt=Refer to caption]] |

|||

==="New Venus"=== |

|||

In the [[planetary romance]] subgenre that flourished in this era, [[Ralph Milne Farley]] and [[Otis Adelbert Kline]] wrote series in this setting starting with ''[[The Radio Man]]'' (1924) and ''[[The Planet of Peril]]'' (1929), respectively.<ref name="Westfahl2021VenusAndVenusians" />{{Rp|page=671}}<ref name="Dozois" />{{rp|xiii}}<ref name="PringlePlanetaryRomances">{{Cite book |title=The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: The Definitive Illustrated Guide |date=1996 |publisher=Carlton |isbn=1-85868-188-X |editor-last=Pringle |editor-first=David |editor-link=David Pringle |location= |language=en |chapter=Planetary Romances |oclc=38373691 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/ultimateencyclop0000unse_a8c7/page/23/mode/2up}}</ref>{{Rp|page=23}}<ref name="BleilerTheEarlyYears">{{Cite book |last=Bleiler |first=Everett Franklin |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KEZxhkG5eikC&pg=PA921 |title=Science-fiction, the Early Years: A Full Description of More Than 3,000 Science-fiction Stories from Earliest Times to the Appearance of the Genre Magazines in 1930 : with Author, Title, and Motif Indexes |date=1990 |publisher=Kent State University Press |others=With the assistance of [[Richard Bleiler|Richard J. Bleiler]] |isbn=978-0-87338-416-2 |language=en |author-link=E. F. Bleiler}}</ref>{{Rp|page=232–234}} These stories were inspired by [[Edgar Rice Burroughs]]'s Martian ''[[Barsoom]]'' series that began with ''[[A Princess of Mars]]'' (1912);<ref name="ScienceFactAndScienceFiction" />{{Rp|page=547}}<ref name="PringlePlanetaryRomances" />{{Rp|page=23}} Burroughs later wrote planetary romances set on a swampy Venus in the ''[[Amtor]]'' series, beginning with ''[[Pirates of Venus]]'' (1932).<ref name="Westfahl2022Venus" />{{Rp|page=167}}<ref name="Liptak" /> Other authors who wrote planetary romances in this setting include [[C. L. Moore]] with the [[Northwest Smith]] adventure "[[Black Thirst]]" (1934) and [[Leigh Brackett]] with stories like "[[The Moon that Vanished]]" (1948) and the [[Eric John Stark]] story "[[Enchantress of Venus]]" (1949).<ref name="Dozois" />{{rp|xiv}}<ref name="VaasZivilisationenAufDerNachbarplanet" /> |

|||

*[[James E. Gunn (writer)|James E. Gunn]]'s 1955 novella "The Naked Sky” (published in ''Startling Stories'' Fall 1955 and retitled "The Joy Ride") starts on a partially terraformed Venus that had been "embalmed at birth, shrouded in stifling clouds of carbon dioxide, hydrochloric and hydrofluoric acids. Beneath those miles of poisonous clouds, Man found a desert where nothing lived, where nothing could live. The vital ingredients were missing: free water, free oxygen. What it offered were unbearable pressures and burning temperatures." |

|||

* In [[Larry Niven]]'s "Becalmed in Hell" (1965), a spaceship exploring the atmosphere of Venus lands to fix a problem. One of the earliest stories to reflect the newer understanding of Venus' high surface temperatures. |

|||

* In [[Frederik Pohl]]'s ''[[The Merchants of Venus]]'' (1972), Pohl made a meticulous effort to present a plausible way for human colonization of Venus, under the conditions revealed by probes. In this story, Venus had been settled in the distant past by mysterious aliens which humans called [[Heechee]]. They left behind various artifacts as well as tunnels and underground chambers which could be adapted to human use, which both considerably reduced the price of colonization and provided a strong economic incentive as Heecheee artifacts fetched high prices. This became the basis for Pohl's celebrated Heechee Series, where the search for Heechee artifacts and the Heechee themselves goes deeper and deeper into space, and meanwhile human-settled Venus has become a sovereign state and a major power. |

|||

* In [[Felix Thijssen]]'s Dutch novel "Pion" (1979), early human attempts at terraforming Venus by seeding its clouds with oxygen producing simple lifeforms threatens to destroy the sentient jellyfish-like Venusians who live in the clouds (due to oxygen being lethal to them). Their only hope is to venusform Earth by removing the oxygen from our atmosphere. |

|||

* In [[John Varley (author)|John Varley]]'s "In the Bowl", humans use advanced technology to live on Venus. |

|||

* In [[Pamela Sargent]]'s Venus series, ''Venus of Dreams'' (1986), ''Venus of Shadows'' (1988), and ''Child of Venus'' (2001), the setting is provided by the [[terraforming of Venus]]. |

|||

* In [[Frank Herbert]]'s ''[[Man of Two Worlds]]'' (1986), part of the story takes place on Venus, with a war occurring on the planet between the French (and their [[French Foreign Legion|Foreign Legion]]) and the Chinese. Foot soldiers on both sides wear armored suits made of ''inceram'', an incredibly heat-resistant material, to protect them from the planet's surface temperatures. Any damage to a soldier's armor which allows the Venusian atmosphere inside results in his body literally boiling into vapor. |

|||

* [[Paul Preuss (author)|Paul Preuss]]' ''[[Venus Prime]]'' second book ''Maëlström'' (1988), is set on Venus. |

|||

* In [[Ben Bova]]'s novel ''[[Venus (novel)|Venus]]'' (2000), part of his [[Grand Tour (novel series)|''Grand Tour'' series]], a scientifically accurate depiction of the planet is offered. Two competing manned expeditions are sent there to recover the body of an astronaut whose previous mission failed for unknown reasons. |

|||

* In [[Sarah Zettel]]'s ''The Quiet Invasion'' (2000), exploration on Venus leads to the discovery of an alien species. |

|||

* In [[Geoffrey A. Landis]]'s "The Sultan of the Clouds" (2010), human settlements float inside balloons at a level of the atmosphere high enough above the surface for the atmospheric temperature to be roughly earthlike. |

|||

* In the [[Mark Brandis]] ''Space Partisans'' universe, mankind in the late 21st century has managed to terraform Venus to host a colony of cities, each covered by massive transparent domes containing a breathable atmosphere and protecting from the heat. The colony had been a former [[Gulag]]-type penitentiary and the domes had been built by the prisoners. |

|||

*In [[Kim Stanley Robinson]]'s ''[[2312 (novel)|2312]]'' (2012), the [[terraforming]] of Venus is being led by the [[China|Chinese]]. A giant parasol is used to block the sun's heat, cooling the atmosphere enough to freeze the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and have it fall onto the surface. Artificial rock is being layered over the CO2 ice before it can sublimate again when the sunlight is returned. |

|||

*In [[James S. A. Corey]]'s ''[[Caliban's War]]'' (2012), Venus is colonised by a sapient alien protomolecule. |

|||

[[Robert A. Heinlein]] portrayed Venusian swamps in several unrelated stories including "[[Logic of Empire]]" (1941), ''[[Space Cadet]]'' (1948), and ''[[Podkayne of Mars]]'' (1963).<ref name="GreenwoodVenus" />{{rp|860}} On [[television]], a 1955 episode of ''[[Tom Corbett, Space Cadet (TV-series)|Tom Corbett, Space Cadet]]'' depicts a crash landing in a Venusian swamp.<ref name="Westfahl2022Venus" />{{Rp|page=168}} Bradbury's short story "[[The Long Rain]]" (1950) depicts Venus as a planet with incessant rain, and was later adapted to screen twice: to film in [[The Illustrated Man (film)|''The Illustrated Man'']] (1969) and to television in ''[[The Ray Bradbury Theater]]'' (1992)—though the latter removed all references to Venus in light of the changed scientific views on the planet's conditions.<ref name="SFEVenus" /><ref name="Westfahl2022Venus" />{{Rp|page=168}}<ref name="Liptak">{{Cite magazine |last=Liptak |first=Andrew |date=May 2016 |title=Destination: Venus |url=https://clarkesworldmagazine.com/liptak_05_16/ |magazine=[[Clarkesworld Magazine]] |issue=116 |issn=1937-7843}}</ref><ref name="SpaceScienceReviewsVenus">{{Cite journal |last1=O'Rourke |first1=Joseph G. |last2=Wilson |first2=Colin F. |last3=Borrelli |first3=Madison E. |last4=Byrne |first4=Paul K. |last5=Dumoulin |first5=Caroline |last6=Ghail |first6=Richard |last7=Gülcher |first7=Anna J. P. |last8=Jacobson |first8=Seth A. |last9=Korablev |first9=Oleg |last10=Spohn |first10=Tilman |last11=Way |first11=M. J. |last12=Weller |first12=Matt |last13=Westall |first13=Frances |date=2023 |title=Venus, the Planet: Introduction to the Evolution of Earth's Sister Planet |url=http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1744153/FULLTEXT01.pdf |url-status=live |journal=[[Space Science Reviews]] |language=en |volume=219 |issue=1 |page= 10|doi=10.1007/s11214-023-00956-0 |bibcode=2023SSRv..219...10O |s2cid=256599851 |issn=0038-6308 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230711065750/http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1744153/FULLTEXT01.pdf |archive-date=2023-07-11}}</ref>{{Rp|page=13}} Bradbury revisited the rainy vision of Venus in "[[All Summer in a Day]]" (1954), where the Sun is only visible through the cloud cover once every seven years.<ref name="VaasZivilisationenAufDerNachbarplanet" /><ref>{{Cite book |last=D'Ammassa |first=Don |title=Encyclopedia of Science Fiction |date=2005 |publisher=Facts On File |isbn=978-0-8160-5924-9 |language=en |chapter=Bradbury, Ray |author-link=Don D'Ammassa |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofsc0000damm/page/53/mode/2up}}</ref>{{Rp|page=53}}<ref>{{Cite web |last=Nicoll |first=James Davis |author-link=James Nicoll |date=2022-07-26 |title=Five Stone-Cold SFF Bummers That Might Make You Feel Better About Your Own Life |url=https://www.tor.com/2022/07/26/five-stone-cold-sff-bummers-that-might-make-you-feel-better-about-your-own-life/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220809023708/https://www.tor.com/2022/07/26/five-stone-cold-sff-bummers-that-might-make-you-feel-better-about-your-own-life/ |archive-date=2022-08-09 |access-date=2023-01-08 |website=[[Tor.com]] |language=en-US}}</ref> In [[German science fiction]], the ''[[Perry Rhodan]]'' novels (launched in 1961) used the vision of Venus as a jungle world, while the protagonist in [[K. H. Scheer]]'s sixteenth ''{{Ill|ZBV (novel series)|lt=ZBV|de|ZBV (Romanserie)}}'' novel ''[[Raumpatrouille Nebelwelt]]'' (1963) is surprised to find that Venus does not have jungles—reflecting then-recent discoveries about the environmental conditions on Venus.<ref name="VaasZivilisationenAufDerNachbarplanet" /><ref name="WandererAmHimmelVenus" />{{rp|78}} |

|||

===Other fictional references to Venus=== |

|||

*In [[Lucian]]'s [[True History]] the war between the King of the Moon and King of the Sun was started when the King of the Sun tried to stop colonisation of the Morning Star. |

|||

* In [[H. G. Wells]]' ''[[The War of the Worlds]]'' (1898), the narrator states in the epilogue that he believes that the [[Martian (War of the Worlds)|Martian]]s may have landed on Venus after the failed invasion of Earth. Ironically, the first film adaptation of the novel, ''[[The War of the Worlds (1953 film)|The War of the Worlds]]'', opens with an exposition on the Martian studies of all the planets in the solar system, with the exception of Venus, before selecting Earth. |

|||

* ''The War of the Wenuses'' (1898) by [[E. V. Lucas]] with C. L. Graves(Charles Larcom Graves) is in fact a parody of [[H G Wells]]'s ''[[The War of the Worlds]]''. |

|||

* In [[J. R. R. Tolkien]]'s [[Middle-earth]] stories, Venus is the Star of [[Eärendil]]. The star was created when Eärendil the Mariner was set in the sky on his ship, with a [[Silmaril]] bound to his brow. Elements of this story go back as far as 1914, though they did not appear in print until 1954. Tolkien chose the name directly from the [[Old English language|Old English]] word ''Earendel'', used as the name of a star (perhaps the morning star, Venus). |

|||

* In [[Hugh Walters (author)|Hugh Walters']] young reader's novel ''[[Expedition Venus]]'' (1962), an unmanned probe returning from Venus crashes in Africa, accidentally releasing a dangerous spore that flourishes in terrestrial conditions. |

|||

*In Stephen King's short story "[[I Am the Doorway]]" (March 1971; reprinted in ''[[Night Shift (book)|Night Shift]]'' 1978), the astronaut protagonist's difficulties occur subsequent to a mission to Venus. |

|||

* In [[Arthur C. Clarke]]'s ''[[Rendezvous With Rama]]'' (1972), the UP (United Planets) organization conspicuously excludes Venus. Later, the book's protagonist William Norton is described as having "distinguished himself during the fifteenth attempt to establish a base on Venus." |

|||

* In [[L. Neil Smith]]'s ''[[The Venus Belt]]'' (1980), part of an [[Alternate history|alternative history]] series, an unrestrained [[capitalism|capitalist]] [[free enterprise]] culture makes a huge success of colonizing the [[asteroid belt]] and decides to blow up and smash to pieces the "utterly useless planet" Venus so as to create a new Asteroid Belt (hence the book's name). |

|||

* In ''[[Mars trilogy|Blue Mars]]'' by [[Kim Stanley Robinson]], it is briefly noted that humans are planning to use a parasol to diffuse or block the sunlight from Venus, causing the atmosphere to condense to the surface as [[dry ice]], where nano-machines will encase it under the oceans under a blanket of nano-engineered [[diamond]]. Metallic drivers are being used to increase the spin of Venus to something like a Terran week per rotation. These ideas are expanded on in Robinson's ''2312'' (see above). |

|||

* In [[Stephen Baxter (author)|Stephen Baxter]]'s ''[[Manifold: Space]]'', Venus is found to have been purposely slowed down through the use of planet-covering superconducting cable. In the novel ''[[Exultant (book)|Exultant]]'' of the ''[[Destiny's Children]]'' series, the Venus of an entirely different universe has been turned into a vast carbon mine, its atmosphere depleted. |

|||

*In ''[[Larklight]]'' (2006) Venus is home to many varieties of plant life, some are even sentient. An experiment by the British Government led to all but one of the 20,000 colonists turning into changeling trees in 1837. In Mothstorm they are finally turned back in 1852 Easter. |

|||

== |

=== Ocean === |

||

Others envisioned Venus as a [[panthalassic planet]], covered by a planet-wide ocean with perhaps a few islands. Large land masses were thought impossible due to the assumption that they would have generated atmospheric updrafts disrupting the planet's solid cloud layer.<ref name="ScienceFactAndScienceFiction" />{{Rp|page=547}}<ref name="ley196604" />{{rp|131}}<ref name="Zalasiewicz">{{Cite journal |last=Zalasiewicz |first=Jan |date=November 2021 |editor-last=Jarochowska |editor-first=Emilia |title=Scanning the heavens |url=https://www.palass.org/publications/newsletter/archive/108/newsletter-no-108 |journal=Palaeontology Newsletter |volume=108 |issn=0954-9900}}</ref>{{Rp|page=41}} Early treatments of an oceanic Venus include [[Harl Vincent]]'s "[[Venus Liberated]]" (1929) and [[Leslie F. Stone]]'s "[[Women with Wings]]" (1930) and ''[[Across the Void]]'' (1931).<ref name="Westfahl2022Venus" />{{Rp|page=167}}<ref name="ScienceFactAndScienceFiction" />{{Rp|page=548}} In [[Olaf Stapledon]]'s ''[[Last and First Men]]'' (1930), future descendants of humanity [[Pantropy|are modified to be adapted to life]] on an ocean-covered Venus.<ref name="SFEVenus" /><ref name="Westfahl2021VenusAndVenusians" />{{Rp|page=672}}<ref name="ScienceFactAndScienceFiction" />{{Rp|page=548}} [[Clifford D. Simak]]'s "[[Rim of the Deep]]" (1940) likewise features an oceanic Venus, with the story set at the bottom of Venusian seas, featuring pirates and hostile Venusian aliens.<ref name="ScienceFactAndScienceFiction" />{{Rp|page=548}}<ref name="Ewald">{{Cite book |last=Ewald |first=Robert J. |title=When the Fires Burn High and The Wind is From the North: The Pastoral Science Fiction of Clifford D. Simak |date=2006 |publisher=Wildside Press LLC |isbn=978-1-55742-218-7 |language=en |chapter=The Early Simak |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hKFObLxy1f8C&pg=PA23}}</ref>{{Rp|page=26–27}} [[C. S. Lewis]]'s ''[[Perelandra]]'' (1943) retells the [[Bible|Biblical]] story of [[Adam and Eve]] in the [[Garden of Eden]] on [[floating island]]s in a vast Venusian ocean.<ref name="SFEVenus" /><ref name="Westfahl2021VenusAndVenusians" />{{Rp|page=672}}<ref name="ScienceFactAndScienceFiction" />{{Rp|page=548}} [[Isaac Asimov]]'s ''[[Lucky Starr and the Oceans of Venus]]'' (1954) depicts human colonists living in underwater cities on Venus.<ref name="Westfahl2022Venus" />{{Rp|page=167}}<ref name="Zalasiewicz" />{{Rp|page=42}} In [[Poul Anderson]]'s "[[Sister Planet]]" (1959), migration to an oceanic Venus is contemplated as a potential solution to Earth's [[overpopulation]].<ref name="GreenwoodVenus" />{{rp|860}} "[[Clash by Night (short story)|Clash by Night]]" (1943) by [[Lawrence O'Donnell (science fiction)|Lawrence O'Donnell]] (joint [[pseudonym]] of C. L. Moore and [[Henry Kuttner]]) and its sequel ''[[Fury (1947 novel)|Fury]]'' (1947) describe survivors from a devastated Earth living beneath Venusian oceans. Those two works have been called in ''[[The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction]]'' "the most enduring pulp image" of an oceanic Venus, and the former received another sequel decades later, ''[[The Jungle (Drake novel)|The Jungle]]'' (1991) by [[David A. Drake]].<ref name="SFEVenus" /><ref name="ScienceFactAndScienceFiction" />{{Rp|page=548}} [[Roger Zelazny]]'s "[[The Doors of His Face, the Lamps of His Mouth]]" (1965) was the last major depiction of an ocean-covered Venus, published shortly after that vision had been rendered obsolete by advances in [[planetary science]].<ref name="Westfahl2021VenusAndVenusians" />{{Rp|page=672}}<ref name="GreenwoodVenus" />{{rp|860}} |

|||

[[File:Planet stories Spring 1942 cover.jpg|thumb|Planet Stories 1942]] |

|||

* The ''[[Buck Rogers]]'' comic strip included several story lines related to Venus, starting with the Sunday sequence "Marooned on Venus" (12/7/30 to 7/12/31), featuring teenage protagonists Buddy and Alura. |

|||

* The Hydrads of Venus, who resemble huge animated sponges, appear in ''[[Planet Comics]]'', in the Lost World section. If hurt, water can restore them to health. Though opposed to the [[Voltamen]] who have invaded Earth, they are also enemies to [[Hunt Bowman]]. |

|||

* Venus features prominently in the British comic ''[[Dan Dare]]'' (original run 1950–1967). ''Dan Dare'''s Venus was divided into two hemispheres, north and south, separated by a "flamebelt" of burning gases. North Venus was the home planet of the hyperintelligent, dictatorial [[The Mekon|Mekon]], Dare's arch-enemy, as well as his people, the [[Treens]]. South Venus is inhabited by a different people, the [[Therons]]. The Treens are green, and mostly emotionless. Descendants of humans abducted from Earth millennia ago are slaves to them. Venus may have been a comment on the divisions of North and South Korea. |

|||

*''Action Comics'' #152 portrays Venusian’s civilization as a futuristic version of Earth’s, and Venusians as humanoids who have adopted English as their planetary language (Act No. 152, January 1951: “The Sleep That Lasted 1000 Years”). |

|||

*''Superman'' #151 on the other hand, portrays Venusian life humorously, depicting Venus as a world inhabited by cute “tomato girls,” “pumpkin men,” “cucumber men,” and other comical “plant-beings” (February 1962: “The Three Tough Teenagers!”). |

|||

*Venus is Cosmic King’s native planet (''Superman'' #147/3), August 1961: “The Legion of Super-Villains!”, and the place where Van-Zee and Sylvia lived prior to taking up residence in Kandor (''Superman's Girl-Friend Lois Lane'' #15, February 1960: “The Super-Family of Steel!” pts. I-III—”Super Husband and Wife!”; “The Bride Gets Super Powers!”; “Secret of the Super-Family!”). |

|||

*In November–December 1948, Superman journeys to Venus to obtain an exotic Venusian flower as a gift for Lois Lane (''Superman'' #55/2: “The Richest Man in the World!”). |

|||

*In January 1951, Dr. Dorrow attempts to exile Superman and Lois Lane to Venus by shutting them inside transparent cylinders filled with “suspended animation gas” and launching them into outer space, but Superman and Lois are released from their cylinders by friendly Venusians and soon succeed in returning to Earth (''Action Comics'' #152, January 1951: “The Sleep That Lasted 1000 Years”). |

|||

*In December 1953, when a meteor is about to destroy Venus, Superboy smashes it and visits Venus to quench his thirst. Upon returning to Smallville, he unknowingly brings back a Venusian spore that grows rapidly into a tree. The tree's strange odor begins to affect the population, making them behave strangely or act out dreams. Superboy uproots the tree, hurls it into space and solves the problem of the alien tree's aroma (''Superboy'' #29, December 1953: "The Tree that Drove Smallville Wild!"). |

|||

*In February 1962, Superman flies a juvenile delinquent to Venus and threatens to abandon him there as part of his plan for teaching the young troublemaker a richly deserved lesson in good manners and respect for others (''Superman'' #151/1, February 1962: "The Three Tough Teenagers!”). |

|||

* In the [[DC Comics]] universe, Venus is home to millions of mind-controlling worms which might have once ruled Earth, such as [[Mister Mind]] (1943), an enemy of [[Captain Marvel (DC Comics)|Captain Marvel]]. It is also the homeworld to the villain [[Cosmic King]] (1961), who was banished for performing transmutation experiments. As shown in the one-shot issue ''[[Wonder Woman]]'' #1,000,000, it is also the potential future home to the [[Amazons]] in that universe in the 853rd century. In Golden Age [[Captain Marvel (DC Comics)|Captain Marvel]] stories Venus was the base of [[Sivana]], the mad scientist. It is inhabited by giant frog-like amphibions and somehow the Sivana family hold royal status there. All of Sivana's four children spent most of their life growing up on Venus, and in early stories it appeared like a safe haven for Sivana. It contained many prehistoric beasts, which Sivana once tried importing to Earth to make a circuis. |

|||

*In the Golden Age ''Showcase'' #23 (the one with Green Lantern) the planet was populated by blue-skinned humanoid cave dwellers and yellow pterodacyl-like predators called Bird-Raiders, which are sealed in a cave by Green Lantern, after he is sent by the Guardians operating through his power battery, to prevent the humans being wiped out.. |

|||

* In the English adaptation of ''[[Black Magic (manga)|Black Magic]]'', one of [[Masamune Shirow]]'s earlier works, a habitable Venus several millions of years before the present is used as the principal setting. It is home to a technologically advanced civilisation of humans and human-like beings. It is implied that the planet later somehow deteriorated into its current (real-life), uninhabitable state. |

|||

* In the [[manga]] ''[[Venus Wars]]'', an ice asteroid designated Apollon collides with Venus in 2003. This has the effect of dispersing much of the planet's atmosphere, adding enough moisture to form (acidic) seas, and speeding up its rotation to give it a day that matches its year. Simply put, due to an unlikely yet scientifically sound accident, it takes amazingly little effort for humans to make the planet marginally habitable - the first manned ship lands in 2007, colonization begins in 2012. |

|||

* In ''[[Sailor Moon]]'', [[Sailor Venus]], also known as [[Minako Aino]], was once the princess of Venus. Magellan Castle, named after the [[Magellan probe]], is where the princess and royal family lived on Venus and ruled over a race of [[Venusians]] prior to the events in the manga. While the inhabitants of Venus are not explored, the character of Adonis in [[Codename: Sailor V]] is also from Venus. All of Sailor Venus' attacks are energy based on gold and love. |

|||

*In DC Comics' ''All-Star Comics'' #13 the JSA are gassed by [[Nazi]]s and rocketed to different planets. The goddess Aphrodite directs the rocket bearing the unconscious Wonder Woman to the planet Venus, and the Amazon is brought before [[Queen Desira]] of the race of Fairies who live there, who immediately recognizes her as the oracle of Aphrodite. Wonder Woman is asked to help battle giant men-warriors, who are killing and capturing the men of the planet. In a series of desperate adventures, Wonder Woman defeats the warriors and is given the gift of magnetic hearing by the Queen. |

|||

* In one [[Super Goof]] comic, the [[Beagle Boys]] trick Super Goof into believing there is a river of gold on Venus, and then steal his return-trip supply of super-peanuts (replacing it with a sack of shell-fragments) which they then use to temporarily get similar superpowers. When Super Goof and Gilbert reach Venus, Gilbert finds the substitution—and puts one super-peanut which he has in his hat in the clouds (producing a bush of huge peanuts within minutes). The two do find what appears to be a river of gold (which the Beagle Boys find out about through a spy-eye which has tracked Super Goof for some time) and then rush there to stop him and Gilbert from returning—but are stopped when Super Goof takes a pipeline (made from the bush that sprouted) and aims some of the stream's liquid at them (which Gilbert has found is actually liquid cheese), who then takes them back to earth and turns them over to the police. |

|||

* In one [[Flash Gordon]] comic, Flash visits a friend on Venus—and has much difficulty from this friend's rowdy son Reynaldo (Venusians in this comic breathe water—an ability the half-Venusian Reynaldo has inherited) after the latter kills one of his father's dolphins. |

|||

== |

=== Desert === |

||

A third group of early theories about conditions on Venus explained the cloud cover with a hot, dry planet where the atmosphere holds water vapor and the surface has dust storms.<ref name="GreenwoodVenus" />{{rp|860}}<ref name="ley196604" />{{rp|131}} The idea that water is abundant on Venus was controversial, and by 1940 [[Rupert Wildt]] had already discussed how a greenhouse effect might result in a hot Venus.<ref name="GreenwoodVenus" />{{rp|860}} The vision of a desert Venus was never as popular as that of a swampy or jungle one, but by the 1950s it started appearing in a number of works.<ref name="MillerVenus" />{{Rp|page=12}}<ref name="GreenwoodVenus" />{{rp|860}} [[Frederik Pohl]] and [[Cyril M. Kornbluth]]'s ''[[The Space Merchants]]'' (1952) is a satire that depicts Venus being successfully marketed as an appealing destination for migrants from Earth in spite of its hostile environment.<ref name="Westfahl2022Venus" />{{Rp|page=168}}<ref name="Liptak" /><ref name="Westfahl2021VenusAndVenusians" />{{Rp|page=672}} In [[Robert Sheckley]]'s "[[Prospector's Special]]" (1959), the desert surface of Venus is [[Space mining|mined for resources]].<ref name="Westfahl2022Venus" />{{Rp|page=168}}<ref name="GreenwoodVenus" />{{rp|860}} [[Arthur C. Clarke]]'s "[[Before Eden]]" (1961) portrays Venus as mostly hot and dry, but with a somewhat cooler climate habitable to [[extremophile]]s at the poles.<ref name="Westfahl2022Venus" />{{Rp|page=171}}<ref name="GreenwoodVenus" />{{rp|860}}<ref name="StanwayCythereanDreamsAndVenusianFutures">{{multiref2|{{Cite web |last=Stanway |first=Elizabeth |author-link=<!-- No article at present (July 2024); Stanway is an astrophysicist at the University of Warwick who has been published in [[Foundation (journal)]], among others (see https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/physics/research/astro/people/stanway/sciencefiction); Wikidata Q127710708 --> |date=2023-12-31 |title=Cytherean Dreams and Venusian Futures—Part One: Cytherean Dreams |url=https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/physics/research/astro/people/stanway/sciencefiction/cosmicstories/cytherean_dreams |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240325220313/https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/physics/research/astro/people/stanway/sciencefiction/cosmicstories/cytherean_dreams |archive-date=2024-03-25 |access-date=2024-03-25 |website=[[Warwick University]] |series=Cosmic Stories Blog}}|{{Cite web |last=Stanway |first=Elizabeth |author-link=<!-- No article at present (July 2024); Stanway is an astrophysicist at the University of Warwick who has been published in [[Foundation (journal)]], among others (see https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/physics/research/astro/people/stanway/sciencefiction); Wikidata Q127710708 --> |date=2024-01-14 |title=Cytherean Dreams and Venusian Futures—Part Two: Venusian Futures |url=https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/physics/research/astro/people/stanway/sciencefiction/cosmicstories/venusian_futures |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240325220955/https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/physics/research/astro/people/stanway/sciencefiction/cosmicstories/venusian_futures |archive-date=2024-03-25 |access-date=2024-03-25 |website=[[Warwick University]] |series=Cosmic Stories Blog}}}}</ref> [[Dean McLaughlin (writer)|Dean McLaughlin]]'s ''[[The Fury from Earth]]'' (1963) likewise features a dry, hostile Venus, this time rebelling against Earth.<ref name="GreenwoodVenus" />{{rp|860}}<ref>{{Cite book |last=D'Ammassa |first=Don |title=Encyclopedia of Science Fiction |date=2005 |publisher=Facts On File |isbn=978-0-8160-5924-9 |language=en |chapter=McLaughlin, Dean |author-link=Don D'Ammassa |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofsc0000damm/page/254/mode/2up}}</ref>{{rp|254}} While these inhospitable portrayals more accurately reflected the emerging scientific data, they nevertheless generally underestimated the harshness of the planet's conditions.<ref name="Liptak" /><ref name="GreenwoodVenus" />{{rp|860}} |

|||

[[File:Derschweigendestern.jpg|thumb|[[First Spaceship on Venus]] (1960)]] |

|||

* Many science-fiction movies and serials of the 1950s and 1960s, such as ''[[Abbott and Costello|Abbott and Costello Go to Mars]]'', ''Space Ship Sappy'', ''[[Queen of Outer Space]]'' (with [[Zsa Zsa Gabor]]), and ''[[Space Patrol (1950 TV series)|Space Patrol]]'', have used the concept of the namesake [[Venus (mythology)|goddess Venus]] and her domain to contrive planetary populations of nubile [[Amazons|Amazonian]] women welcoming (or attacking) all-male astronaut crews (even though the goddess Venus - or [[Aphrodite]] for that matter - had absolutely nothing to do with the Amazons; that role belonged to [[Ares]], or to [[Artemis]]). |

|||

* The original ''[[Space Patrol (1950 TV series)|Space Patrol]]'' displayed Venus (with the exception of cities and bases built by the United Planets) as the cloud-covered, swampy, dinosaur- and amazon-ridden version discussed above. (The few episodes of the ''Space Patrol'' radio shows set on Venus all took place in the highly civilized sections of it.) |

|||

* The later British ''[[Space Patrol (1962)|''Space Patrol'']]'' (1962) puppet television series featured episodes along these lines: |

|||

** "Time Stands Still" episode. Stolen art treasures are being transported into space. Raeburn suspects that Venusian millionaire Tara is behind the thefts, but his palace is too well-guarded. Professor Heggarty develops a watch that speeds up the wearer's reaction sixty times, which enables Dart to sneak into the palace unnoticed. |

|||

** "The Human Fish" episode. The Tula Fish in the Venusian Magda Ocean are evolving at an extraordinary rate and attack fishermen. The Galasphere crew are sent to help and discover that building materials, routinely dumped in the ocean, may be the cause of the Tula's accelerated evolution. |

|||

* ''[[First Spaceship on Venus|Der Schweigende Stern]]'' (1960) (''The Silent Star'', vaguely translated into English as ''First Spaceship on Venus''). In this co-production East Germany-Poland, based on [[Stanisław Lem]]'s book ''[[Astronauci]]'' (''The Astronauts''), it is discovered that the [[Tunguska Event]] in 1908 was the crash of a spaceship from Venus, and a multi-national crew is sent to the planet. They find the Venusians to have destroyed themselves (probably in a nuclear war) and the environment to be hostile. We never see the actual Venusians, but in an eerie scene, humanoid flash shadows are shown on a wall. |

|||

* The ''[[The Twilight Zone (1959 TV series)|Twilight Zone]]'' episode "[[Will the Real Martian Please Stand Up?]]" shows a three-eyed Venusian disguised as a human chef. He tells a Martian sent before a colonisation force that Venus is forming a colony on Earth and has intercepted the Martian colonisation force. |

|||

* The Russian film ''Планета Бур (Planeta Bur)'' (''Storm Planet'', 1962) is about an expedition to Venus that discovers dinosaurs. The film exists in many badly-recut versions, including ''[[Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet]]'' and ''[[Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women]]'', which were re-directed by [[Curtis Harrington]] and [[Peter Bogdanovich]], respectively, under pseudonyms. |

|||

* "[[Cold Hands, Warm Heart]]" (1964), episode of ''[[The Outer Limits (1963 TV series)|The Outer Limits]]'' television series starring William Shatner as an astronaut who returns from a voyage to Venus suffering from unexplained mutations. |

|||

*"[[Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster]]" (1964), a film in the [[Godzilla]] franchise, has a character stating that 5,000 years ago, an ancient civilazation lived on Venus before being wiped out by [[King Ghidorah]]. |

|||

* Venus is the location of several [[Starfleet Academy]] training facilities and terraforming stations in the fictional ''[[Star Trek]]'' universe (1966– ). |

|||

* ''[[Doomsday Machine (1972 film)|Doomsday Machine]]'', a film originally produced in 1967, but not released until 1972, depicts an ill-fated attempt, in (a fictional version of) the year 1975, by an [[United States|American]]-launched and led, mixed-gender space-faring crew of humans (survivors of a [[World War III|war]] in which their home planet Earth had been obliterated by the armed forces of [[China]], using an [[doomsday device|apocalyptic super-weapon]], hence the film's title) to colonize Venus, before the planet's [[telepathic]] inhabitants, fearing mankind's "self-destructive powers", presumably destroy the humans' spaceship and, at film's end, send the last surviving human couple (the "Last of Man", as they were so-called by the Venusians), aboard a re-discovered, derelict [[Soviet]] sister craft, to a place somewhere "beyond the rim of the Universe". |

|||

* The British science fiction series ''[[Space: 1999]]'' also refers to a mission to a space station orbiting Venus where the crew contracts a deadly virus and must be left to die rather than bring the infection back to Earth. |

|||

* A failed Russian probe that returns to Earth and wreaks havoc was a recurring "character" on the 1970s series ''[[The Bionic Woman]]''. |

|||

* In ''[[Doctor Who]]'', the Third Doctor purports to be an expert in Venusian [[aikido]] and sings Venusian lullabies. The [[Virgin Missing Adventures|Missing Adventures]] novel ''[[Venusian Lullaby]]'' elaborates on this, depicting the First Doctor visiting a dying Venus three billion years in the past. The Fourth Doctor holds a pilot's license for the [[Robot (Doctor Who)|Mars—Venus run]]. |

|||

* The British spy/fantasy TV series ''[[The Avengers (TV series)|The Avengers]]'' with characters ''[[John Steed]]'' and ''[[Emma Peel]]'' has a 1967 episode entitled ''[[From Venus With Love]]'' (a whimsical reference to the ''[[James Bond]]'' title ''[[From Russia, with Love (novel)|From Russia With Love]]'') about a group of amateur astronomers, all members of the BVS (British Venusian Society). One by one they succumb to death due to sudden advanced age, each after having observed Venus, allegedly as a result of an Earth invasion by Venusians. One of the BVS members (Brigadier Whitehead) is played by [[Jon Pertwee]], 3 years prior to his eponymous role in ''[[Doctor Who]]''. |

|||

* In the BBC miniseries ''[[Space Odyssey: Voyage to the Planets]]'' (2004), Venus is the first destination of the interplanetary science vessel ''Pegasus''. Cosmonaut Yvan Grigorev becomes the first human to set foot on the planet during a short manned landing, which due to the hostile environment, only has a planned duration of one hour. |

|||

* Venus was the first planet when a team of eight astronauts were doing a grand tour of the solar system in ''[[Defying Gravity (TV series)|Defying Gravity]]''. Two of the astronauts land on the planet in search of an object. |

|||

*In the second episode of ''[[Challenge of the Superfriends]]'' Venus is shown to be inhabited by an advanced civilisation called the Fearians. They form an alliance with the [[Legion of Doom (Super Friends)|Legion of Doom]], who trick the Superfriends into changing the world so it can support Fearian life. This will allow the Fearians to form a colony and the Legion will rule the world. The Superfriends are trapped by the Fearian Leader in a force field. However Green Lantern makes them invisible, causing the Leader to think they have escaped and turn of the field. He is defeated by Black Lightning and Green Lantern sends him back to Venus. The Superfriends then restore the world. The Fearian Leader has three-heads, with green skin and red eyes. |

|||

== |

==Paradigm shift== |

||

[[File:PIA00103 Venus - 3-D Perspective View of Lavinia Planitia.jpg|thumb|The barren, cratered surface of Venus. ([[Magellan (spacecraft)|Magellan]] radar imagery)]] |

|||

* ''[[Venus Wars]]'' (1989) is an animated film that takes place on a terraformed Venus. |

|||

In scientific circles, life on Venus was increasingly viewed as unlikely from the 1930s on, as more advanced methods for observing Venus suggested that its atmosphere lacked oxygen.<ref>{{cite book |last=Dick |first=Steven |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sk51eo3fKEgC&pg=PA43 |title=Life on Other Worlds: The 20th-Century Extraterrestrial Life Debate |date=2001 |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |isbn=0-521-79912-0 |page= |author-link=Steven J. Dick}}</ref>{{rp|43}} In the [[Space Age]], space probes starting with the 1962 ''[[Mariner 2]]'' found that Venus's surface temperature was in the range of {{convert|800–900|F|4=-2}}, and atmospheric pressure at ground-level was many times that of Earth's.<ref name="ScienceFactAndScienceFiction" />{{Rp|page=548}}<ref name="Dozois" />{{rp|xv}}<ref name="ley196604" />{{rp|131}} This rendered obsolete fiction that had depicted a planet with exotic but habitable settings, and writers' interest in the planet diminished when its inhospitability became better understood.<ref name="ScienceFactAndScienceFiction" />{{Rp|page=548}}<ref name="Dozois" />{{rp|xv}}<ref name="ley196604">{{Cite magazine |last=Ley |first=Willy |author-link=Willy Ley |date=April 1966 |editor-last=Pohl |editor-first=Frederik |editor-link=Frederik Pohl |title=The Re-Designed Solar System |url=https://archive.org/stream/Galaxy_v24n04_1966-04#page/n63/mode/1up |department=For Your Information |magazine=[[Galaxy Science Fiction]] |type= |volume=24 |issue=4 |pages= |oclc=1184799209}}</ref>{{rp|131}}Some works go so far as to portray Venus as a mostly ignored part of an otherwise thoroughly explored Solar System; examples include Clarke's ''[[Rendezvous with Rama]]'' (1973) and the novel series ''[[The Expanse (novel series)|The Expanse]]'' (2011–2021) by [[James S. A. Corey]] (joint pseudonym of [[Daniel Abraham (author)|Daniel Abraham]] and [[Ty Franck]]).<ref name="SpaceScienceReviewsVenus" />{{Rp|page=14}} |

|||

* In the television series ''[[Exosquad]]'', a [[terraforming of Venus|terraformed Venus]] was one of the three Homeworlds. |

|||

* Venus is the setting of [[Cowboy bebop episodes|episode ("session")8]] "Watz for Venus" of the anime ''[[Cowboy Bebop]]'' (1998). In the show, Venus is an arid but habitable world, [[terraforming of Venus|terraformed]] by floating plants in the atmosphere.These plants are depicted to be the size of [[Clouds#Towering vertical .28Family D2.29|cumulous clouds]]. These plants occasionally precipitate snow like [[Plant spore|spores]] which cause a disease called Venus Sickness .In episode 8, [[Spike Spiegel|Spike]] meets a woman named Stella who has become [[Legally blind#Classification|legally blind]] as a result of Venus Sickness .In the same episode Stella's brother [[List of Cowboy Bebop characters#Rocco Bonnaro|Rocco]] goes to great lengths to obtain a plant called Gray Ash, which can cure Stella from Venus Sickness and restore her sight. Much of the population lives in floating cities in the sky. Local society and architecture appear to be loosely based on real-life India, [[Istanbul]] and other parts of Middle and Southwest Asia. In episode ("session") 8 Spike meets Rocco at a [[cathedral]] which resembles [[Hagia Sophia]]. |

|||

* In the Disney animated feature film ''[[The Princess and the Frog]]'', Venus (the "Evening Star") is dubbed Evangeline by Ray the firefly and is from that point on in the movie referred to by all the characters as such. Ray becomes a second one at the end after he died. |

|||

* A Superfriends episode shows Venus as a world inhabited by giant termites who have destroyed the world. A volcanic eruption sends termites to Earth, however Samurai is able to send them into space. |

|||

=== |

=== Nostalgic depictions === |

||

{{See also|Mars in fiction#Nostalgic depictions}} |

|||

* In the role-playing game ''[[Transhuman Space]]'', a scientific colony of a few thousand people has been established on Venus. The [[European Union]] has also begun construction of a [[Space sunshade|sunshade]] as a first step toward terraforming Venus. |

|||

A romantic, habitable, pre-Mariner Venus continued to appear for a while in deliberately nostalgic and [[Retro style|retro]] works such as Zelazny's "The Doors of His Face, the Lamps of His Mouth" (1965) and [[Thomas M. Disch]]'s "[[Come to Venus Melancholy]]" (1965), and [[Brian Aldiss]] and [[Harry Harrison (writer)|Harry Harrison]] collected works written before the scientific advancements in the anthology ''[[Farewell, Fantastic Venus]]'' (1968).<ref name="ScienceFactAndScienceFiction" />{{Rp|page=548}}<ref name="Dozois" />{{rp|xv-xvii}}<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Tomlinson |first1=Paul |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M_f4g9NHkPcC&pg=PA201 |title=Harry Harrison: An Annotated Bibliography |last2=Harrison |first2=Harry |date=2002 |publisher=Wildside Press LLC |isbn=978-1-58715-401-0 |language=en |author-link2=Harry Harrison (writer)}}</ref>{{Rp|page=201}} The nostalgic image of Venus has also occasionally resurfaced several decades later: [[S. M. Stirling]]'s ''[[The Sky People]]'' (2006) takes place in an [[Parallel universes in fiction|alternate universe]] where the pulp version of Venus is real, and the anthology ''[[Old Venus]]'' (2015) edited by [[George R. R. Martin]] and [[Gardner Dozois]] collects newly-written works in the style of older stories about the now-outdated vision of Venus.<ref name="Liptak" /><ref name="Dozois" />{{rp|xv-xvii}} The [[role-playing game]]s ''[[Space: 1889]]'' (1989) and ''[[Mutant Chronicles]]'' (1993) likewise use a deliberately retro depiction of Venus.<ref name="WandererAmHimmelVenus" />{{rp|79}} |

|||

* In the computer game ''[[Descent (video game)|Descent]]'', levels 4 and 5 take place in a Venus atmospheric lab, and a nickel-iron mine. In the game's third installment, ''[[Descent³]]'', the final level of the game takes place in an underground facility on Venus where the game's main antagonist fled to and hidden himself in. |

|||

* In the PC game ''[[Battlezone (1998 video game)|Battlezone]]'', Venus is featured in several missions and multiplayer maps with a brown atmosphere, constant lightning and thunder, and fog. The heat does not affect the gameplay, but lakes of molten yellow-colored material can damage the player's tank. |

|||

* In the ''[[Mutant Chronicles]]'' game universe, Venus is an important setting, following the pulp era jungle description. |

|||

* In the [[PlayStation]] game ''[[Colony Wars (video game)|Colony Wars]]'', the wider universe believed that Venus had been destroyed, but it was in fact an experiment by the Empire to cloak a planet. |

|||

* In [[Destiny (video game)|Destiny]], Venus is a planet terraformed by the Traveler, a mysterious alien artifact comprised of advanced technology. It lifted the clouds of poisonous carbon dioxide and created oceans on it's surface, prompting human colonization. The Ishtar Collective, a famous university and research station, was built on Venus. When alien races invaded the solar system, Venus was abandoned and is now reaching a pre-terraformation stage, rendering it uninhabitable. The player must fight the alien races off before the planet consumes itself. |

|||