Technetium: Difference between revisions

→Pertechnetate and derivatives: Fixed typo Tags: canned edit summary Mobile edit Mobile app edit |

→Physical properties: Added measurement conversion. |

||

| (409 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

{{pp-move-indef}}{{use dmy dates|date=September 2024}} |

||

{{Infobox technetium}} |

{{Infobox technetium}} |

||

'''Technetium''' is a [[chemical element]] |

'''Technetium''' is a [[chemical element]]; it has [[Symbol (chemistry)|symbol]] '''Tc''' and [[atomic number]] 43. It is the lightest element whose [[isotopes]] are all [[radioactive]]. Technetium and [[promethium]] are the only radioactive elements whose neighbours in the sense of atomic number are both stable. All available technetium is produced as a [[synthetic element]]. Naturally occurring technetium is a spontaneous [[fission product]] in [[uranium ore]] and [[thorium]] ore (the most common source), or the product of [[neutron capture]] in [[molybdenum]] ores. This silvery gray, crystalline [[transition metal]] lies between [[manganese]] and [[rhenium]] in [[group 7 element|group 7]] of the [[periodic table]], and its chemical properties are intermediate between those of both adjacent elements. The most common naturally occurring isotope is <sup>99</sup>Tc, in traces only. |

||

Many of technetium's properties |

Many of technetium's properties had been predicted by [[Dmitri Mendeleev]] before it was discovered; Mendeleev noted a gap in his periodic table and gave the undiscovered element the provisional name ''[[Mendeleev's predicted elements|ekamanganese]]'' (''Em''). In 1937, technetium became the first predominantly artificial element to be produced, hence its name (from the Greek ''{{transl|el|technetos}}'', 'artificial', + {{nowrap|''[[wikt:-ium#Suffix|-ium]]'').}} |

||

One short-lived [[gamma ray]] |

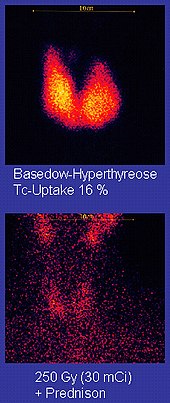

One short-lived [[gamma ray]]–emitting [[nuclear isomer]], [[technetium-99m]], is used in [[nuclear medicine]] for a wide variety of tests, such as bone cancer diagnoses. The ground state of the [[nuclide]] [[technetium-99]] is used as a gamma ray–free source of [[beta particle]]s. Long-lived [[isotopes of technetium|technetium isotopes]] produced commercially are byproducts of the [[nuclear fission|fission]] of [[uranium-235]] in [[nuclear reactors]] and are extracted from [[nuclear fuel cycle|nuclear fuel rods]]. Because even the longest-lived isotope of technetium has a relatively short [[half-life]] (4.21 million years), the 1952 detection of technetium in [[red giant]]s helped to prove that stars can [[nuclear fusion|produce heavier elements]]. |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

=== |

===Early assumptions=== |

||

From the 1860s through 1871, early forms of the periodic table proposed by Dmitri Mendeleev contained a gap between [[molybdenum]] (element 42) and [[ruthenium]] (element 44). In 1871, Mendeleev predicted this missing element would occupy the empty place below [[manganese]] and have similar chemical properties. Mendeleev gave it the provisional name '' |

From the 1860s through 1871, early forms of the periodic table proposed by [[Dmitri Mendeleev]] contained a gap between [[molybdenum]] (element 42) and [[ruthenium]] (element 44). In 1871, Mendeleev predicted this missing element would occupy the empty place below [[manganese]] and have similar chemical properties. Mendeleev gave it the provisional name ''eka-manganese'' (from ''eka'', the [[Sanskrit]] word for ''one'') because it was one place down from the known element manganese.<ref>{{cite journal|doi = 10.1007/BF00837634|title = Technetium, the missing element|date = 1996|last1 = Jonge|journal = European Journal of Nuclear Medicine|volume = 23|pages = 336–44|pmid = 8599967|last2 = Pauwels|first2 = E. K.|issue = 3|s2cid = 24026249}}</ref> |

||

===Early misidentifications=== |

=== Early misidentifications === |

||

Many early researchers, both before and after the periodic table was published, were eager to be the first to discover and name the missing element. Its location in the table suggested that it should be easier to find than other undiscovered elements. |

Many early researchers, both before and after the periodic table was published, were eager to be the first to discover and name the missing element. Its location in the table suggested that it should be easier to find than other undiscovered elements. This turned out not to be the case, due to technetium's radioactivity. |

||

{| class |

{| class="wikitable" |

||

! Year |

! Year |

||

! Claimant |

! Claimant |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

|[[Iridium]] |

|[[Iridium]] |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1845 |

|||

|1846 |

|||

|[[Heinrich Rose]] |

|||

|R. Hermann |

|||

|[[Pelopium]]<ref name="history-origin">{{cite news| title = History of the Origin of the Chemical Elements and Their Discoverers|url = http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/content/elements.html|access-date = 2009-05-05| first = N. E.|last = Holden| publisher = Brookhaven National Laboratory}}</ref> |

|||

|[[Ilmenium]] |

|||

|Niobium–tantalum alloy |

|||

|[[Niobium]]-[[tantalum]] [[alloy]] |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|1847 |

|1847 |

||

|R. Hermann |

|||

|[[Heinrich Rose]] |

|||

|[[Ilmenium]]<ref>{{cite journal|doi = 10.1002/prac.184704001110|title = Untersuchungen über das Ilmenium|year = 1847|last = Hermann |first=R.|journal = Journal für Praktische Chemie|volume = 40|pages = 457–480|url = https://zenodo.org/record/1427800}}</ref> |

|||

|[[Pelopium]]<ref name="history-origin">{{cite news| title = History of the Origin of the Chemical Elements and Their Discoverers|url = http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/content/elements.html|accessdate = 2009-05-05| first = N. E.|last = Holden| publisher = Brookhaven National Laboratory}}</ref> |

|||

|Niobium |

|[[Niobium]]–[[tantalum]] [[alloy]] |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1877 |

|1877 |

||

|Serge Kern |

|Serge Kern |

||

|[[Davyum]] |

|[[Davyum]] |

||

|[[Iridium]] |

|[[Iridium]]–[[rhodium]]–[[iron]] alloy |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1896 |

|1896 |

||

| Line 49: | Line 50: | ||

|[[Masataka Ogawa]] |

|[[Masataka Ogawa]] |

||

|[[Nipponium]] |

|[[Nipponium]] |

||

|[[Rhenium]], which was the |

|[[Rhenium]], which was the unknown [[Mendeleev's predicted elements|dvi]]-manganese<ref>{{cite journal|title=Discovery of a new element 'nipponium': re-evaluation of pioneering works of Masataka Ogawa and his son Eijiro Ogawa|journal=Spectrochimica Acta Part B|date=2004|first=H. K.| last=Yoshihara |volume=59 |issue=8 |pages=1305–1310 |doi=10.1016/j.sab.2003.12.027 |bibcode=2004AcSpB..59.1305Y}}</ref><ref name=nipponium2022>{{cite journal |last1=Hisamatsu |first1=Yoji |last2=Egashira |first2=Kazuhiro |first3=Yoshiteru |last3=Maeno |date=2022 |title=Ogawa's nipponium and its re-assignment to rhenium |journal=Foundations of Chemistry |volume=24 |issue= |pages=15–57 |doi=10.1007/s10698-021-09410-x |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

||

|} |

|} |

||

===Irreproducible results=== |

===Irreproducible results=== |

||

[[File:Periodisches System der Elemente (1904-1945, now Gdansk University of Technology).jpg|thumb| |

[[File:Periodisches System der Elemente (1904-1945, now Gdansk University of Technology).jpg|thumb|right|{{lang|de|Periodisches System der Elemente}} (Periodic system of the elements) (1904–1945, now at the [[Gdańsk University of Technology]]): lack of elements: [[polonium]] {{sup|84}}Po (though discovered as early as in 1898 by [[Marie Curie|Maria Sklodowska-Curie]]), [[astatine]] {{sup|85}}At (1940, in Berkeley), [[francium]] {{sup|87}}Fr (1939, in France), neptunium {{sup|93}}Np (1940, in Berkeley) and other [[actinide]]s and [[lanthanide]]s. Uses old symbols for: [[argon]] {{sup|18}}Ar (here: A), '''technetium {{sup|43}}Tc''' (Ma, masurium), [[xenon]] {{sup|54}}Xe (X), [[radon]] {{sup|86}}Rn (Em, emanation).]] |

||

German chemists [[Walter Noddack]], [[Otto Berg (scientist)|Otto Berg]], and [[Ida Tacke]] reported the discovery of element 75 and element 43 in 1925, and named element 43 '' |

German chemists [[Walter Noddack]], [[Otto Berg (scientist)|Otto Berg]], and [[Ida Tacke]] reported the discovery of element 75 and element 43 in 1925, and named element 43 ''masurium'' (after [[Masuria]] in eastern [[Prussia]], now in [[Poland]], the region where Walter Noddack's family originated).<ref name=multidict/> This name caused significant resentment in the scientific community, because it was interpreted as referring to a [[First Battle of the Masurian Lakes|series]] of [[Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes|victories]] of the German army over the Russian army in the Masuria region during World War I; as the Noddacks remained in their academic positions while the Nazis were in power, suspicions and hostility against their claim for discovering element 43 continued.<ref name=Scerri/> The group bombarded [[columbite]] with a beam of [[electron]]s and deduced element 43 was present by examining [[X-ray]] emission [[spectrogram]]s.{{sfn|Emsley|2001|p=423}} The [[wavelength]] of the X-rays produced is related to the atomic number by a [[Moseley's law|formula]] derived by [[Henry Moseley]] in 1913. The team claimed to detect a faint X-ray signal at a wavelength produced by element 43. Later experimenters could not replicate the discovery, and it was dismissed as an error.<ref name="armstrong">{{cite journal |last=Armstrong |first=J.T. |date=2003 |title=Technetium |journal=Chemical & Engineering News |volume=81 |issue=36 |pages=110 |doi=10.1021/cen-v081n036.p110 |url=http://pubs.acs.org/cen/80th/technetium.html |access-date=2009-11-11}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|first=K. A.|last=Nies |date=2001 |title=Ida Tacke and the warfare behind the discovery of fission |url=http://www.hypatiamaze.org/ida/tacke.html |access-date=2009-05-05 |url-status=dead |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20090809125217/http://www.hypatiamaze.org/ida/tacke.html |archive-date = 2009-08-09}}</ref> Still, in 1933, a series of articles on the discovery of elements quoted the name ''masurium'' for element 43.<ref>{{cite journal |last = Weeks |first = M.E. |date = 1933 |title = The discovery of the elements. XX. Recently discovered elements |journal = Journal of Chemical Education |volume = 10 |issue = 3 |pages = 161–170|doi = 10.1021/ed010p161 |bibcode = 1933JChEd..10..161W }}</ref> Some more recent attempts have been made to rehabilitate the Noddacks' claims, but they are disproved by [[Paul Kuroda]]'s study on the amount of technetium that could have been present in the ores they studied: it could not have exceeded {{nobr|3 × {{10^|−11}} μg/kg}} of ore, and thus would have been undetectable by the Noddacks' methods.<ref name=Scerri>{{cite book |first=Eric |last=Scerri |author-link=Eric Scerri |title=A tale of seven elements |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2013 |isbn=978-0-19-539131-2 |pages=109–114, 125–131}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Habashi |first1=Fathi |date=2006 |title=The History of Element 43—Technetium |url=https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/ed083p213.1 |journal=Journal of Chemical Education |volume=83 |issue=2 |pages=213 |doi=10.1021/ed083p213.1 |bibcode=2006JChEd..83..213H |access-date=2 January 2023}}</ref> |

||

===Official discovery and later history=== |

===Official discovery and later history=== |

||

The [[Discovery of the chemical elements|discovery]] of element 43 was finally confirmed in a |

The [[Discovery of the chemical elements|discovery]] of element 43 was finally confirmed in a 1937 experiment at the [[University of Palermo]] in Sicily by [[Carlo Perrier]] and [[Emilio Segrè]].<ref>{{cite book |last=Heiserman |first=D. L. |year=1992 |chapter=Element 43: Technetium |title=Exploring Chemical Elements and their Compounds |location=New York, NY |publisher=TAB Books |isbn=978-0-8306-3018-9 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/exploringchemica01heis |page=164}}</ref> In mid-1936, Segrè visited the United States, first [[Columbia University]] in New York and then the [[Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory]] in California. He persuaded [[cyclotron]] inventor [[Ernest Lawrence]] to let him take back some discarded cyclotron parts that had become [[radioactive]]. Lawrence mailed him a [[molybdenum]] foil that had been part of the deflector in the cyclotron.<ref>{{cite book |first=Emilio |last=Segrè |date=1993 |title=A Mind Always in Motion: The autobiography of Emilio Segrè |publisher=University of California Press |location=Berkeley, CA |isbn=978-0520076273 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/mindalwaysinmoti00segr/page/115 115–118] |url=https://archive.org/details/mindalwaysinmoti00segr/page/115 }}</ref> |

||

Segrè enlisted his colleague Perrier to attempt to prove, through comparative chemistry, that the molybdenum activity was indeed from an element with the atomic number 43. In 1937 they succeeded in isolating the [[isotope]]s [[technetium-95]]m and [[technetium-97]].<ref name=segre/><ref name=blocks>{{ |

Segrè enlisted his colleague Perrier to attempt to prove, through comparative chemistry, that the molybdenum activity was indeed from an element with the atomic number 43. In 1937, they succeeded in isolating the [[isotope]]s [[technetium-95]]m and [[technetium-97]].<ref name=segre/><ref name=blocks>{{harvnb|Emsley|2001|pp=[https://archive.org/details/naturesbuildingb0000emsl/page/422 422]–425}}</ref>{{Disputed inline|First isotopes known|date=April 2024}} [[University of Palermo]] officials wanted them to name their discovery {{lang|la|panormium}}, after the Latin name for [[Palermo]], ''{{lang|la|Panormus}}''. In 1947,<ref name=segre>{{cite journal |last1= Perrier |first1= C. |last2= Segrè |first2= E. |date= 1947 |title=Technetium: The element of atomic number 43 |journal= Nature |volume= 159 |issue= 4027 |page= 24 |doi= 10.1038/159024a0 |pmid= 20279068 |bibcode= 1947Natur.159...24P |s2cid= 4136886}}</ref> element 43 was named after the [[Greek language|Greek]] word {{transl|el|technetos}} ({{lang|el|τεχνητός}}), meaning 'artificial', since it was the first element to be artificially produced.<ref name=history-origin/><ref name=multidict> |

||

{{cite web |

|||

|last=van der Krogt |first=P. |

|||

|series=Elentymolgy and Elements Multidict |

|||

|title=Technetium |

|||

|url=http://elements.vanderkrogt.net/element.php?sym=Tc |

|||

|access-date=2009-05-05 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Segrè returned to Berkeley and met [[Glenn T. Seaborg]]. They isolated the [[metastable isotope]] [[technetium-99m]], which is now used in some ten million medical diagnostic procedures annually.<ref> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|last1=Hoffman |first1=Darleane C. |

|||

|last2=Ghiorso |first2=Albert |

|||

|last3=Seaborg |first3=Glenn T. |

|||

|date =2000 |

|||

|chapter=Chapter 1.2: Early days at the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory |

|||

|title=The Transuranium People: The inside story |

|||

|series = [[Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory]] |

|||

|publisher = University of California Press |

|||

|place = Berkeley, CA |

|||

|isbn=978-1-86094-087-3 |

|||

|page =15 |

|||

|chapter-url =http://www.worldscibooks.com/physics/p074.html |

|||

|access-date = 2007-03-31 |url-status=dead |

|||

|archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20070124220556/http://www.worldscibooks.com/physics/p074.html |

|||

|archive-date=2007-01-24 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

In 1952, astronomer [[Paul W. Merrill]] in California detected the [[ |

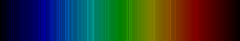

In 1952, the astronomer [[Paul W. Merrill]] in California detected the [[emission spectrum|spectral signature]] of technetium (specifically [[wavelength]]s of 403.1 [[Nanometre|nm]], 423.8 nm, 426.2 nm, and 429.7 nm) in light from [[Stellar classification#Class S|S-type]] [[red giant]]s.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Merrill |first=P.W. |date=1952 |title=Technetium in the stars |journal=Science |volume=115 |issue=2992|pages=479–489, esp. 484 |doi=10.1126/science.115.2992.479|pmid=17792758 |bibcode=1952Sci...115..479. }}</ref> The stars were near the end of their lives but were rich in the short-lived element, which indicated that it was being produced in the stars by [[nuclear reaction]]s. That evidence bolstered the hypothesis that heavier elements are the product of [[nucleosynthesis]] in stars.<ref name=blocks/> More recently, such observations provided evidence that elements are formed by [[neutron capture]] in the [[s-process]].<ref name=s8>{{harvnb|Schwochau|2000|pp=7–9}}</ref> |

||

Since that discovery, there have been many searches in terrestrial materials for natural sources of technetium. In 1962, technetium-99 was isolated and identified in [[uraninite|pitchblende]] from the [[Belgian Congo]] in |

Since that discovery, there have been many searches in terrestrial materials for natural sources of technetium. In 1962, technetium-99 was isolated and identified in [[uraninite|pitchblende]] from the [[Belgian Congo]] in very small quantities (about 0.2 ng/kg),<ref name=s8/> where it originates as a [[spontaneous fission]] product of [[uranium-238]]. The [[natural nuclear fission reactor]] in [[Oklo]] contains evidence that significant amounts of technetium-99 were produced and have since decayed into [[ruthenium-99]].<ref name=s8/> |

||

==Characteristics== |

==Characteristics== |

||

===Physical properties=== |

===Physical properties=== |

||

Technetium is a silvery-gray radioactive [[metal]] with an appearance similar to [[platinum]], commonly obtained as a gray powder.{{sfn|Hammond|2004|p={{page needed|date=June 2021}}}} The [[crystal structure]] of the bulk pure metal is [[Hexagonal crystal system|hexagonal]] [[close-packed]], and crystal structures of the nanodisperse pure metal are [[Cubic crystal system|cubic]]. Nanodisperse technetium does not have a split NMR spectrum,<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Kuznetsov |first1=Vitaly V. |last2=Poineau |first2=Frederic |last3=German |first3=Konstantin E. |last4=Filatova |first4=Elena A. |date=2024-11-11 |title=Pivotal role of 99Tc NMR spectroscopy in solid-state and molecular chemistry |journal=Communications Chemistry |language=en |volume=7 |issue=1 |page=259 |doi=10.1038/s42004-024-01349-2 |pmid=39528801 |issn=2399-3669 |pmc=11555319}}</ref> while hexagonal bulk technetium has the Tc-99-NMR spectrum split in 9 satellites.{{sfn|Hammond|2004|p={{page needed|date=June 2021}}}}<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Tarasov |first1=V.P. |last2=Muravlev |first2=Yu. B. |last3=German |first3=K. E. |last4=Popova |first4=N.N. |date=2001 |title=<sup>99</sup>Tc NMR of Supported Technetium Nanoparticles |journal=Doklady Physical Chemistry |volume=377 |number=1–3 |pages=71–76 |doi=10.1023/A:1018872000032 |s2cid=91522281 |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/251379398}}</ref> Atomic technetium has characteristic [[Emission spectrum|emission lines]] at [[wavelength]]s of 363.3 [[Nanometre|nm]], 403.1 nm, 426.2 nm, 429.7 nm, and 485.3 nm.<ref>{{cite book | first=David R. | last=Lide |date = 2004–2005 |chapter = Line spectra of the elements |title = The CRC Handbook |publisher =CRC press |pages=10–70 (1672) | isbn=978-0-8493-0595-5 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=q2qJId5TKOkC&pg=PT1672 }}</ref> The unit cell parameters of the orthorhombic Tc metal were reported when Tc is contaminated with carbon ({{mvar|a}} = 0.2805(4), {{mvar|b}} = 0.4958(8), {{mvar|c}} = 0.4474(5)·nm for Tc-C with 1.38 wt% C and {{mvar|a}} = 0.2815(4), {{mvar|b}} = 0.4963(8), {{mvar|c}} = 0.4482(5)·nm for Tc-C with 1.96 wt% C ).<ref name="carbide"/> The metal form is slightly [[paramagnetism|paramagnetic]], meaning its [[dipole|magnetic dipoles]] align with external [[magnetic field]]s, but will assume random orientations once the field is removed.<ref name=enc>{{cite book |last=Rimshaw |first=S.J. |date=1968 |editor-last=Hampel |editor-first=C.A. |title=The Encyclopedia of the Chemical Elements |location=New York, NY |publisher=Reinhold Book Corporation |url=https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofch00hamp |url-access=registration |pages=[https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofch00hamp/page/689 689–693] }}</ref> Pure, metallic, single-crystal technetium becomes a [[type-II superconductor]] at temperatures below {{convert|7.46|K|abbr=on|lk=in}}.{{sfn|Schwochau|2000|p=96}}{{efn| |

|||

Technetium is a silvery-gray radioactive [[metal]] with an appearance similar to [[platinum]], commonly obtained as a gray powder.<ref name=CRC/> The [[crystal structure]] of the pure metal is [[Hexagonal crystal system|hexagonal]] [[close-packed]]. Atomic technetium has characteristic [[Emission spectrum|emission lines]] at these [[wavelength]]s of light: 363.3 [[Nanometre|nm]], 403.1 nm, 426.2 nm, 429.7 nm, and 485.3 nm.<ref>{{cite book| title = The CRC Handbook| publisher =CRC press|chapter = Line Spectra of the Elements| date = 2004–2005|url=https://books.google.com/?id=q2qJId5TKOkC&pg=PT1672|pages=10–70 (1672) | first=David R. | last=Lide | isbn=978-0-8493-0595-5}}</ref> |

|||

Irregular crystals and trace impurities raise this transition temperature to 11.2 K for 99.9% pure technetium powder.{{sfn|Schwochau|2000|p=96}} |

|||

}} |

|||

The metal form is slightly [[paramagnetism|paramagnetic]], meaning its [[dipole|magnetic dipoles]] align with external [[magnetic field]]s, but will assume random orientations once the field is removed.<ref name=enc>{{cite book| title = The Encyclopedia of the Chemical Elements| editor = Hampel, C. A.| last = Rimshaw |first=S. J.| location = New York| publisher = Reinhold Book Corporation| date = 1968| pages = 689–693}}</ref> Pure, metallic, single-crystal technetium becomes a [[type-II superconductor]] at temperatures below 7.46 [[Kelvin|K]].<ref group=note>Irregular crystals and trace impurities raise this transition temperature to 11.2 K for 99.9% pure technetium powder.{{harv|Schwochau|2000|p=96}}</ref><ref name=":0">Schwochau, K. ''Technetium: Chemistry and Radiopharmaceutical Applications''; Wiley-VCH:Weinheim, Germany, 2000. |

|||

Below this temperature, technetium has a very high [[London penetration depth|magnetic penetration depth]], greater than any other element except [[niobium]].<ref>{{cite conference |last = Autler |first=S.H. |date=Summer 1968 |title = Technetium as a material for AC superconductivity applications |conference = 1968 Summer Study on Superconducting Devices and Accelerators |url = http://www.bnl.gov/magnets/Staff/Gupta/Summer1968/0049.pdf |access-date = 2009-05-05}}</ref> |

|||

</ref> Below this temperature, technetium has a very high [[London penetration depth|magnetic penetration depth]], greater than any other element except [[niobium]].<ref>{{cite news| title = Technetium as a Material for AC Superconductivity Applications| last = Autler |first=S. H.| publisher = Proceedings of the 1968 Summer Study on Superconducting Devices and Accelerators|accessdate = 2009-05-05|date=1968| url = http://www.bnl.gov/magnets/Staff/Gupta/Summer1968/0049.pdf}}</ref> |

|||

===Chemical properties=== |

===Chemical properties=== |

||

Technetium is located in the [[Group 7 element| |

Technetium is located in the [[Group 7 element|group 7]] of the periodic table, between [[rhenium]] and [[manganese]]. As predicted by the [[History of the periodic table|periodic law]], its chemical properties are between those two elements. Of the two, technetium more closely resembles rhenium, particularly in its chemical inertness and tendency to form [[covalent bond]]s.{{sfn|Greenwood|Earnshaw|1997|p=1044}} This is consistent with the tendency of [[period 5 element|period 5 elements]] to resemble their counterparts in period 6 more than period 4 due to the [[lanthanide contraction]]. Unlike manganese, technetium does not readily form [[cation]]s ([[ion]]s with net positive charge). Technetium exhibits nine [[oxidation state]]s from −1 to +7, with +4, +5, and +7 being the most common.<ref name=LANL/> Technetium dissolves in [[aqua regia]], [[nitric acid]], and concentrated [[sulfuric acid]], but ''not'' in [[hydrochloric acid]] of any concentration.{{sfn|Hammond|2004|p={{page needed|date=June 2021}}}} |

||

Metallic technetium slowly [[tarnish]]es in moist air<ref name=LANL>{{cite web |last=Husted |first=R. |date=2003-12-15 |title=Technetium |series=Periodic Table of the Elements |publisher=[[Los Alamos National Laboratory]] |place=Los Alamos, NM |url=http://periodic.lanl.gov/43.shtml |access-date=2009-10-11}}</ref> and, in powder form, burns in [[oxygen]]. When reacting with [[hydrogen]] at high pressure, it forms the hydride TcH{{sub|1.3}}<ref name="Zhou 2023">{{cite journal |last1=Zhou |first1=Di |last2=Semenok |first2=Dmitrii V. |last3=Volkov |first3=Mikhail A. |last4=Troyan |first4=Ivan A. |last5=Seregin |first5=Alexey Yu. |last6=Chepkasov |first6=Ilya V. |last7=Sannikov |first7=Denis A. |last8=Lagoudakis |first8=Pavlos G. |last9=Oganov |first9=Artem R. |last10=German |first10=Konstantin E. |display-authors=6 |date=2023-02-06 |title=Synthesis of technetium hydride TcH<sub>1.3</sub> at 27 GPa |url=https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevB.107.064102 |journal=Physical Review B |volume=107 |issue=6 |page=064102 |doi=10.1103/PhysRevB.107.064102 |arxiv=2210.01518 |bibcode=2023PhRvB.107f4102Z }}</ref> and while reacting with [[carbon]] it forms Tc{{sub|6}}C,<ref name=carbide>{{cite journal |last1=German |first1=K.E. |last2=Peretrukhin |first2=V.F. |last3=Gedgovd |first3=K.N. |last4=Grigoriev |first4=M.S. |last5=Tarasov |first5=A.V. |last6=Plekhanov |first6=Yu V. |last7=Maslennikov |first7=A.G. |last8=Bulatov |first8=G.S. |last9=Tarasov |first9=V.P. |last10=Lecomte |first10=M. |display-authors=6 |date=2005 |title=Tc carbide and new orthorhombic Tc metal phase |journal=Journal of Nuclear and Radiochemical Sciences |volume=6 |issue=3 |pages=211–214 |doi=10.14494/jnrs2000.6.3_211 |doi-access=free |url=https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jnrs2000/6/3/6_3_211/_article }}</ref> with cell parameter 0.398 nm, as well as the nanodisperce low-carbon-content carbide with parameter 0.402nm.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kuznetsov |first1=Vitaly V. |last2=German |first2=Konstantin E. |last3=Nagovitsyna |first3=Olga A. |last4=Filatova |first4=Elena A. |last5=Volkov |first5=Mikhail A. |last6=Sitanskaia |first6=Anastasiia V. |last7=Pshenichkina |first7=Tatiana V. |date=2023-10-31 |title=Route to stabilization of nano-technetium in an amorphous carbon matrix: Preparative methods, XAFS evidence, and electrochemical studies |url=https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.3c03001 |journal=Inorganic Chemistry |volume=62 |issue=45 |pages=18660–18669 |language=en |doi=10.1021/acs.inorgchem.3c03001 |pmid=37908073 |issn=0020-1669}}</ref> |

|||

Metallic technetium slowly [[tarnish]]es in moist air<ref name="LANL">{{cite web|title=Technetium|url=http://periodic.lanl.gov/43.shtml|publisher=Los Alamos National Laboratory|date=2003-12-15|work=Periodic Table of the Elements|last=Husted|first=R.|accessdate=2009-10-11}}</ref> and, in powder form, burns in [[oxygen]]. |

|||

Technetium can catalyse the destruction of [[hydrazine]] by [[nitric acid]], and this property is due to its multiplicity of valencies.<ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1016/0022-5088(84)90023-7 | title=The technetium-catalysed oxidation of hydrazine by nitric acid | journal=Journal of the Less Common Metals | date=1984 | volume=97 | pages=191–203 | first=John | last=Garraway}}</ref> This caused a problem in the separation of plutonium from uranium in [[Nuclear reprocessing|nuclear fuel processing]], where hydrazine is used as a protective reductant to keep plutonium in the trivalent rather than the more stable tetravalent state. The problem was exacerbated by the mutually |

Technetium can catalyse the destruction of [[hydrazine]] by [[nitric acid]], and this property is due to its multiplicity of valencies.<ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1016/0022-5088(84)90023-7 | title=The technetium-catalysed oxidation of hydrazine by nitric acid | journal=Journal of the Less Common Metals | date=1984 | volume=97 | pages=191–203 | first=John | last=Garraway}}</ref> This caused a problem in the separation of plutonium from uranium in [[Nuclear reprocessing|nuclear fuel processing]], where hydrazine is used as a protective reductant to keep plutonium in the trivalent rather than the more stable tetravalent state. The problem was exacerbated by the mutually enhanced solvent extraction of technetium and zirconium at the previous stage,<ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1016/0022-5088(85)90379-0 | title=Coextraction of pertechnetate and zirconium by tri-n-butyl phosphate | journal=Journal of the Less Common Metals | date=1985 | volume=106 | issue=1 | pages=183–192 | first=J. | last=Garraway}}</ref> and required a process modification. |

||

==Compounds== |

==Compounds== |

||

===Pertechnetate and derivatives=== |

===Pertechnetate and other derivatives=== |

||

{{main|Pertechnetate}} |

|||

[[File:Pertechnetate1.svg|thumb|left|200 px|Pertechnetate is one of the most available forms of technetium. It is structurally related to [[permanganate]].]] |

|||

[[File:Pertechnetate1.svg|thumb|left|upright|Pertechnetate is one of the most available forms of technetium. It is structurally related to [[permanganate]].]] |

|||

The most prevalent form of technetium that is easily accessible is sodium pertechnetate, Na[TcO<sub>4</sub>]. The majority of this material is produced by radioactive decay from [<sup>99</sup>MoO<sub>4</sub>]<sup>2−</sup>:<ref>{{harvnb|Schwochau|2000|pp=127–136}}</ref><ref name=nuclmed/> |

|||

The most prevalent form of technetium that is easily accessible is [[sodium pertechnetate]], Na[TcO<sub>4</sub>]. The majority of this material is produced by radioactive decay from [<sup>99</sup>MoO<sub>4</sub>]<sup>2−</sup>:{{sfn|Schwochau|2000|pp=127–136}}<ref name="nuclmed" /> |

|||

:[<sup>99</sup>MoO<sub>4</sub>]<sup>2−</sup> → [<sup>99</sup>TcO<sub>4</sub>]<sup>−</sup> + γ |

|||

[[Pertechnetate]] (tetroxidotechnetate) {{chem|TcO|4|-}} behaves analogously to perchlorate, with which it is isostructural. It is [[tetrahedral molecular geometry|tetrahedral]]. Unlike [[permanganate]] ({{chem|MnO|4|-}}), it is only a weak oxidizing agent. |

|||

{{block indent|[<sup>99</sup>MoO<sub>4</sub>]<sup>2−</sup> → [<sup>99m</sup>TcO<sub>4</sub>]<sup>−</sup> + e<sup>−</sup>}} |

|||

Related to pertechnetate is [[Technetium(VII) oxide|heptoxide]]. This pale-yellow, volatile solid is produced by oxidation of Tc metal and related precursors: |

|||

:4 Tc + 7 O<sub>2</sub> → 2 Tc<sub>2</sub>O<sub>7</sub> |

|||

It is a very rare example of a molecular metal oxide, other examples being [[OsO4|OsO<sub>4</sub>]] and [[RuO4|RuO<sub>4</sub>]]. It adopts a [[Centrosymmetry|centrosymmetric]] structure with two types of Tc−O bonds with 167 and 184 pm bond lengths.<ref>{{cite journal|last = Krebs|first = B.|title = Technetium(VII)-oxid: Ein Übergangsmetalloxid mit Molekülstruktur im festen Zustand (Technetium(VII) Oxide, a Transition Metal Oxide with a Molecular Structure in the Solid State)|journal = Angewandte Chemie|date = 1969|volume = 81|pages = 328–329|doi = 10.1002/ange.19690810905|issue = 9}}</ref> |

|||

[[Pertechnetate]] ({{chem|TcO|4|-}}) is only weakly hydrated in aqueous solutions,<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ustynyuk |first1=Yuri A. |last2=Gloriozov |first2=Igor P. |last3=Zhokhova |first3=Nelly I. |last4=German |first4=Konstantin E. |last5=Kalmykov |first5=Stepan N. |date=2021-11-15 |title=Hydration of the pertechnetate anion. DFT study |journal=Journal of Molecular Liquids |volume=342 |page=117404 |doi=10.1016/j.molliq.2021.117404 |issn=0167-7322 |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167732221021280 }}</ref> and it behaves analogously to perchlorate anion, both of which are [[tetrahedral molecular geometry|tetrahedral]]. Unlike [[permanganate]] ({{chem|MnO|4|-}}), it is only a weak [[oxidizing agent]]. |

|||

Technetium heptoxide hydrolyzes to [[pertechnetate]] and [[pertechnetic acid]], depending on the pH:<ref>{{harvnb|Schwochau|2000|p=127}}</ref> |

|||

:<ref>{{cite book| last1= Herrell|first1 = A. Y.|last2 = Busey|first2 = R. H.|last3 = Gayer|first3 = K. H.|title = Technetium(VII) Oxide, in Inorganic Syntheses| date = 1977|volume = XVII| pages = 155–158|isbn= 0-07-044327-0}}</ref> |

|||

:Tc<sub>2</sub>O<sub>7</sub> + 2 OH<sup>−</sup> → 2 TcO<sub>4</sub><sup>−</sup> + H<sub>2</sub>O |

|||

:Tc<sub>2</sub>O<sub>7</sub> + H<sub>2</sub>O → 2 HTcO<sub>4</sub> |

|||

Related to pertechnetate is [[Technetium(VII) oxide|technetium heptoxide]]. This pale-yellow, volatile solid is produced by oxidation of Tc metal and related precursors: |

|||

Dark red, [[Hygroscopy|hygroscopic]] HTcO<sub>4</sub> is a strong acid. In concentrated [[sulfuric acid]], [TcO<sub>4</sub>]<sup>−</sup> converts to the octahedral form TcO<sub>3</sub>(OH)(H<sub>2</sub>O)<sub>2</sub>, the conjugate base of the hypothetical tri[[aquo complex]] [TcO<sub>3</sub>(H<sub>2</sub>O)<sub>3</sub>]<sup>+</sup>.<ref>{{cite journal|display-authors=7|author=Poineau F|author2=Weck PF|author3=German K|author4=Maruk A|author5=Kirakosyan G|author6= Lukens W|author7=Rego DB|author8=Sattelberger AP|author9=Czerwinski KR|title= Speciation of heptavalent technetium in sulfuric acid: structural and spectroscopic studies|journal= Dalton Transactions|date= 2010|volume= 39 |issue=37|pages=8616–8619|doi=10.1039/C0DT00695E |url=http://radchem.nevada.edu/docs/pub/tc%20in%20h2so4%20%28dalton%29%202010-08-23.pdf|pmid=20730190}}</ref> |

|||

{{block indent|4 Tc + 7 O<sub>2</sub> → 2 Tc<sub>2</sub>O<sub>7</sub>}} |

|||

It is a molecular metal oxide, analogous to [[manganese heptoxide]]. It adopts a [[Centrosymmetry|centrosymmetric]] structure with two types of Tc−O bonds with 167 and 184 pm bond lengths.<ref>{{cite journal |last = Krebs |first = B. |date = 1969 |title = Technetium(VII)-oxid: Ein Übergangsmetalloxid mit Molekülstruktur im festen Zustand |language=de |trans-title=Technetium(VII) oxide, a transition metal oxide with a molecular structure in the solid tate |journal = Angewandte Chemie |volume = 81 |issue = 9 |pages = 328–329 |doi = 10.1002/ange.19690810905 | bibcode=1969AngCh..81..328K }}</ref> |

|||

Technetium heptoxide hydrolyzes to pertechnetate and [[pertechnetic acid]], depending on the pH:{{sfn|Schwochau|2000|p=127}}<ref>{{cite book |last1=Herrell |first1=A.Y. |last2=Busey |first2=R.H. |last3=Gayer |first3=K.H. |date=1977 |title=Technetium(VII) Oxide, in Inorganic Syntheses |volume=XVII |pages=155–158|isbn=978-0-07-044327-3 }}</ref> |

|||

{{block indent|Tc<sub>2</sub>O<sub>7</sub> + 2 OH<sup>−</sup> → 2 TcO<sub>4</sub><sup>−</sup> + H<sub>2</sub>O}} |

|||

{{block indent|Tc<sub>2</sub>O<sub>7</sub> + H<sub>2</sub>O → 2 HTcO<sub>4</sub>}} |

|||

HTcO<sub>4</sub> is a strong acid. In concentrated [[sulfuric acid]], [TcO<sub>4</sub>]<sup>−</sup> converts to the octahedral form TcO<sub>3</sub>(OH)(H<sub>2</sub>O)<sub>2</sub>, the conjugate base of the hypothetical tri[[aquo complex]] [TcO<sub>3</sub>(H<sub>2</sub>O)<sub>3</sub>]<sup>+</sup>.<ref>{{cite journal |display-authors=6 |vauthors=Poineau F, Weck PF, German K, Maruk A, Kirakosyan G, Lukens W, Rego DB, Sattelberger AP, KR |name-list-style=vanc |date=2010 |title=Speciation of heptavalent technetium in sulfuric acid: Structural and spectroscopic studies |journal=Dalton Transactions |volume=39 |issue=37 |pmid=20730190 |s2cid=9419843 |pages=8616–8619|doi=10.1039/C0DT00695E |url=http://radchem.nevada.edu/docs/pub/tc%20in%20h2so4%20%28dalton%29%202010-08-23.pdf |access-date=2011-11-14 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170305152213/http://radchem.nevada.edu/docs/pub/tc%20in%20h2so4%20%28dalton%29%202010-08-23.pdf |archive-date=2017-03-05 }}</ref> |

|||

===Other chalcogenide derivatives=== |

===Other chalcogenide derivatives=== |

||

Technetium forms a dioxide, |

Technetium forms a [[technetium(IV) oxide|dioxide]],{{sfn|Schwochau|2000|p=108}} [[metal dichalcogenide|disulfide]], di[[selenide]], and di[[telluride (chemistry)|telluride]]. An ill-defined Tc<sub>2</sub>S<sub>7</sub> forms upon treating [[pertechnate]] with hydrogen sulfide. It thermally decomposes into disulfide and elemental sulfur.{{sfn|Schwochau|2000|pp=112–113}} Similarly the dioxide can be produced by reduction of the Tc<sub>2</sub>O<sub>7</sub>. |

||

Unlike the case for rhenium, a trioxide has not been isolated for |

Unlike the case for rhenium, a trioxide has not been isolated for technetium. However, TcO<sub>3</sub> has been identified in the gas phase using [[mass spectrometry]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Gibson |first1=John K. |year=1993 |title=High-temperature oxide and hydroxide vapor species of technetium |journal=Radiochimica Acta |volume=60 |issue=2–3 |pages=121–126 |doi=10.1524/ract.1993.60.23.121 |s2cid=99795348 }}</ref> |

||

===Simple hydride and halide complexes=== |

===Simple hydride and halide complexes=== |

||

Technetium forms the |

Technetium forms the complex {{chem|TcH|9|2-}}. The potassium salt is [[isostructural]] with [[Potassium nonahydridorhenate|{{chem|ReH|9|2-}}]].{{sfn|Schwochau|2000|p=146}} At high pressure formation of TcH<sub>1.3</sub> from elements was also reported.<ref name="Zhou 2023"/> |

||

[[File:Zirconium-tetrachloride-3D-balls-A.png|thumb|TcCl<sub>4</sub> forms chain-like structures, similar to the behavior of several other metal tetrachlorides.]] |

|||

The following binary (containing only two elements) technetium halides are known: [[TcF6|TcF<sub>6</sub>]], TcF<sub>5</sub>, [[TcCl4|TcCl<sub>4</sub>]], TcBr<sub>4</sub>, TcBr<sub>3</sub>, α-TcCl<sub>3</sub>, β-TcCl<sub>3</sub>, TcI<sub>3</sub>, α-TcCl<sub>2</sub>, and β-TcCl<sub>2</sub>. The [[Oxidation state|oxidation states]] range from Tc(VI) to Tc(II). Technetium halides exhibit different structure types, such as molecular octahedral complexes, extended chains, layered sheets, and metal clusters arranged in a three-dimensional network.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3100&context=thesesdissertations|title=Binary Technetium Halides|last=Johnstone|first=E. V.|date=2014|website=|publisher=|access-date=}}</ref><ref name=AS>{{cite journal|doi=10.1021/ar400225b|pmid=24393028|title=Recent Advances in Technetium Halide Chemistry|journal=Accounts of Chemical Research|volume=47|issue=2|pages=624|year=2014|last1=Poineau|first1=Frederic|last2=Johnstone|first2=Erik V.|last3=Czerwinski|first3=Kenneth R.|last4=Sattelberger|first4=Alfred P.}}</ref> These compounds are produced by combining the metal and halogen or by less direct reactions. |

|||

The following binary (containing only two elements) technetium halides are known: [[TcF6|TcF<sub>6</sub>]], TcF<sub>5</sub>, [[TcCl4|TcCl<sub>4</sub>]], TcBr<sub>4</sub>, TcBr<sub>3</sub>, α-TcCl<sub>3</sub>, β-TcCl<sub>3</sub>, TcI<sub>3</sub>, α-TcCl<sub>2</sub>, and β-TcCl<sub>2</sub>. The [[oxidation state]]s range from Tc(VI) to Tc(II). Technetium halides exhibit different structure types, such as molecular octahedral complexes, extended chains, layered sheets, and metal clusters arranged in a three-dimensional network.<ref>{{cite thesis |last=Johnstone |first=E.V. |date=May 2014 |title=Binary Technetium Halides |publisher=[[University of Nevada]] |place=Las Vegas, NV |doi=10.34917/5836118 |via=UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones |url=http://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3100&context=thesesdissertations }}</ref><ref name=AS>{{cite journal |last1=Poineau |first1=Frederic |last2=Johnstone |first2=Erik V. |last3=Czerwinski |first3=Kenneth R. |last4=Sattelberger |first4=Alfred P. |year=2014 |title=Recent advances in technetium halide chemistry |journal=Accounts of Chemical Research |volume=47 |issue=2 |pages=624–632 |doi=10.1021/ar400225b |pmid=24393028 }}</ref> These compounds are produced by combining the metal and halogen or by less direct reactions. |

|||

TcCl<sub>4</sub> is obtained by chlorination of Tc metal or Tc<sub>2</sub>O<sub>7</sub> Upon heating, TcCl<sub>4</sub> gives the corresponding Tc(III) and Tc(II) chlorides.<ref name=AS/> |

TcCl<sub>4</sub> is obtained by chlorination of Tc metal or Tc<sub>2</sub>O<sub>7</sub>. Upon heating, TcCl<sub>4</sub> gives the corresponding Tc(III) and Tc(II) chlorides.<ref name=AS/> |

||

:TcCl<sub>4</sub> → α-TcCl<sub>3</sub> + 1/2 Cl<sub>2</sub> |

|||

:TcCl<sub>3</sub> → β-TcCl<sub>2</sub> + 1/2 Cl<sub>2</sub> |

|||

[[File: Zirconium-tetrachloride-3D-balls-A.png|thumb|180 px|left|TcCl<sub>4</sub> forms chain-like structures, similar to the behavior of several other metal tetrachlorides.]] |

|||

The structure of TcCl<sub>4</sub> is composed of infinite zigzag chains of edge-sharing TcCl<sub>6</sub> octahedra. It is isomorphous to transition metal tetrachlorides of [[zirconium]], [[hafnium]], and [[platinum]].<ref name=AS/> |

|||

{{block indent|TcCl<sub>4</sub> → α-TcCl<sub>3</sub> + 1/2 Cl<sub>2</sub>}} |

|||

Two polymorphs of technetium trichloride exist, α- and β-TcCl<sub>3</sub>. The α polymorph is also denoted as Tc<sub>3</sub>Cl<sub>9</sub>. It adopts a confacial [[Octahedral molecular geometry#Bioctahedral molecular geometry|bioctahedral structure]].<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1021/ja105730e|pmid=20977207|title=Synthesis and Structure of Technetium Trichloride|journal=Journal of the American Chemical Society|volume=132|issue=45|pages=15864|year=2010|last1=Poineau|first1=Frederic|last2=Johnstone|first2=Erik V.|last3=Weck|first3=Philippe F.|last4=Kim|first4=Eunja|last5=Forster|first5=Paul M.|last6=Scott|first6=Brian L.|last7=Sattelberger|first7=Alfred P.|last8=Czerwinski|first8=Kenneth R.}}</ref> It is prepared by treating the chloro-acetate Tc<sub>2</sub>(O<sub>2</sub>CCH<sub>3</sub>)<sub>4</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub> with HCl. Like [[Trirhenium nonachloride|Re<sub>3</sub>Cl<sub>9</sub>]], the structure of the α-polymorph consists of triangles with short M-M distances. β-TcCl<sub>3</sub> features octahedral Tc centers, which are organized in pairs, as seen also for [[molybdenum trichloride]]. TcBr<sub>3</sub> does not adopt the structure of either trichloride phase. Instead it has the structure of [[molybdenum tribromide]], consisting of chains of confacial octahedra with alternating short and long Tc—Tc contacts. TcI<sub>3</sub> has the same structure as the high temperature phase of [[titanium(III) iodide|TiI<sub>3</sub>]], featuring chains of confacial octahedra with equal Tc—Tc contacts.<ref name=AS/> |

|||

{{block indent|TcCl<sub>3</sub> → β-TcCl<sub>2</sub> + 1/2 Cl<sub>2</sub>}} |

|||

The structure of TcCl<sub>4</sub> is composed of infinite zigzag chains of edge-sharing TcCl<sub>6</sub> octahedra. It is isomorphous to transition metal tetrachlorides of [[zirconium]], [[hafnium]], and [[platinum]].<ref name="AS" /> |

|||

Several anionic technetium halides are known. The binary tetrahalides can be converted to the hexahalides [TcX<sub>6</sub>]<sup>2−</sup> (X = F, Cl, Br, I), which adopt [[octahedral molecular geometry]].<ref name=s8/> More reduced halides form anionic clusters with Tc-Tc bonds. The situation is similar for the related elements of Mo, W, Re. These clusters have the nuclearity Tc<sub>4</sub>, Tc<sub>6</sub>, Tc<sub>8</sub>, and Tc<sub>13</sub>. The more stable Tc<sub>6</sub> and Tc<sub>8</sub> clusters have prism shapes where vertical pairs of Tc atoms are connected by triple bonds and the planar atoms by single bonds. Every technetium atom makes six bonds, and the remaining valence electrons can be saturated by one axial and two [[bridging ligand]] halogen atoms such as [[chlorine]] or [[bromine]].<ref>{{cite journal|first1 = K. E.|last1 = German|last2= Kryutchkov|first2 = S. V.|title = Polynuclear Technetium Halide Clusters|journal = Russian Journal of Inorganic Chemistry|volume =47|issue = 4|date = 2002|pages = 578–583|url=http://www.maik.rssi.ru/cgi-perl/search.pl?type=abstract&name=inrgchem&number=4&year=2&page=578}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Chloro-containing coordination complexes of technetium (Tc-99).jpg|thumb|Chloro-containing coordination complexes of technetium (<sup>99</sup>Tc) in various oxidation states: Tc(III), Tc(IV), Tc(V), and Tc(VI) represented.]] |

|||

Two polymorphs of [[technetium trichloride]] exist, α- and β-TcCl<sub>3</sub>. The α polymorph is also denoted as Tc<sub>3</sub>Cl<sub>9</sub>. It adopts a confacial [[Octahedral molecular geometry#Bioctahedral molecular geometry|bioctahedral structure]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Poineau |first1=Frederic |last2=Johnstone |first2=Erik V.|last3=Weck |first3=Philippe F. |last4=Kim |first4=Eunja |last5=Forster |first5=Paul M. |last6=Scott |first6=Brian L. |last7=Sattelberger |first7=Alfred P. |last8=Czerwinski |first8=Kenneth R. |display-authors=6 |year=2010 |title=Synthesis and structure of technetium trichloride |journal=Journal of the American Chemical Society |volume=132 |issue=45 |pages=15864–15865 |doi=10.1021/ja105730e |pmid=20977207 }}</ref> It is prepared by treating the chloro-acetate Tc<sub>2</sub>(O<sub>2</sub>CCH<sub>3</sub>)<sub>4</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub> with HCl. Like [[Trirhenium nonachloride|Re<sub>3</sub>Cl<sub>9</sub>]], the structure of the α-polymorph consists of triangles with short M-M distances. β-TcCl<sub>3</sub> features octahedral Tc centers, which are organized in pairs, as seen also for [[molybdenum trichloride]]. TcBr<sub>3</sub> does not adopt the structure of either trichloride phase. Instead it has the structure of [[molybdenum tribromide]], consisting of chains of confacial octahedra with alternating short and long Tc—Tc contacts. TcI<sub>3</sub> has the same structure as the high temperature phase of [[titanium(III) iodide|TiI<sub>3</sub>]], featuring chains of confacial octahedra with equal Tc—Tc contacts.<ref name=AS/> |

|||

Several anionic technetium halides are known. The binary tetrahalides can be converted to the hexahalides [TcX<sub>6</sub>]<sup>2−</sup> (X = F, Cl, Br, I), which adopt [[octahedral molecular geometry]].<ref name=s8/> More reduced halides form anionic clusters with Tc–Tc bonds. The situation is similar for the related elements of Mo, W, Re. These clusters have the nuclearity Tc<sub>4</sub>, Tc<sub>6</sub>, Tc<sub>8</sub>, and Tc<sub>13</sub>. The more stable Tc<sub>6</sub> and Tc<sub>8</sub> clusters have prism shapes where vertical pairs of Tc atoms are connected by triple bonds and the planar atoms by single bonds. Every technetium atom makes six bonds, and the remaining valence electrons can be saturated by one axial and two [[bridging ligand]] halogen atoms such as [[chlorine]] or [[bromine]].<ref>{{cite journal |first1 = K.E. |last1 = German |last2 = Kryutchkov|first2 = S.V. |date = 2002 |title = Polynuclear technetium halide clusters |journal = Russian Journal of Inorganic Chemistry |volume = 47 |issue = 4 |pages = 578–583 |url = http://www.maik.rssi.ru/cgi-perl/search.pl?type=abstract&name=inrgchem&number=4&year=2&page=578 |url-status = dead |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20151222111809/http://www.maik.rssi.ru/cgi-perl/search.pl?type=abstract&name=inrgchem&number=4&year=2&page=578 |archive-date = 2015-12-22 }}</ref> |

|||

===Coordination and organometallic complexes=== |

===Coordination and organometallic complexes=== |

||

[[File:Tc CNCH2CMe2(OMe) 6Cation.png|thumb|right|[[Technetium (99mTc) sestamibi]] |

[[File:Tc CNCH2CMe2(OMe) 6Cation.png|thumb|right|[[Technetium (99mTc) sestamibi|Technetium (<sup>99m</sup>Tc) sestamibi]] ("Cardiolite") is widely used for imaging of the heart.]] |

||

Technetium forms a variety of [[coordination complex]]es with organic ligands. |

Technetium forms a variety of [[coordination complex]]es with organic ligands. Many have been well-investigated because of their relevance to [[nuclear medicine]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Bartholomä |first1=Mark D. |last2=Louie |first2=Anika S. |last3=Valliant |first3=John F. |last4=Zubieta |first4=Jon |year=2010 |title=Technetium and gallium derived radiopharmaceuticals: Comparing and contrasting the chemistry of two important radiometals for the molecular imaging era |journal=Chemical Reviews |volume=110 |issue=5 |pages=2903–20 |doi=10.1021/cr1000755 |pmid=20415476 }}</ref> |

||

Technetium forms a variety of compounds with Tc–C bonds, i.e. organotechnetium complexes. |

Technetium forms a variety of compounds with Tc–C bonds, i.e. organotechnetium complexes. Prominent members of this class are complexes with CO, arene, and cyclopentadienyl ligands.<ref name=Alberto/> The binary carbonyl Tc<sub>2</sub>(CO)<sub>10</sub> is a white volatile solid.<ref>{{cite journal |last1 = Hileman |first1 = J.C. |last2 = Huggins |first2 = D.K. |last3 = Kaesz |first3 = H.D. |date = 1961 |title = Technetium carbonyl |journal = Journal of the American Chemical Society |volume = 83 |issue = 13 |pages = 2953–2954 |doi = 10.1021/ja01474a038}}</ref> In this molecule, two technetium atoms are bound to each other; each atom is surrounded by [[octahedron|octahedra]] of five carbonyl ligands. The bond length between technetium atoms, 303 pm,<ref>{{cite journal |last1 =Bailey |first1 = M.F. |last2 = Dahl |first2 = Lawrence F. |date =1965 |title = The crystal structure of ditechnetium decacarbonyl |journal =Inorganic Chemistry |volume =4 |issue = 8 |pages =1140–1145 |doi =10.1021/ic50030a011 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1 = Wallach |first1 = D. |date = 1962 |title = Unit cell and space group of technetium carbonyl, Tc2(CO)10 |journal = Acta Crystallographica |volume = 15 |issue = 10 |page = 1058 | bibcode=1962AcCry..15.1058W |doi = 10.1107/S0365110X62002789 }}</ref> is significantly larger than the distance between two atoms in metallic technetium (272 pm). Similar [[carbonyl]]s are formed by technetium's [[Congener (chemistry)|congeners]], manganese and rhenium.{{sfn|Schwochau|2000|pp=286, 328}} Interest in organotechnetium compounds has also been motivated by applications in [[nuclear medicine]].<ref name=Alberto>{{cite book |last1=Alberto |first1=Roger |year=2010 |chapter=Organometallic radiopharmaceuticals |title=Medicinal Organometallic Chemistry |volume=32 |pages=219–246 |series=Topics in Organometallic Chemistry |isbn=978-3-642-13184-4 |doi=10.1007/978-3-642-13185-1_9 }}</ref> Technetium also forms aquo-carbonyl complexes, one prominent complex being [Tc(CO)<sub>3</sub>(H<sub>2</sub>O)<sub>3</sub>]<sup>+</sup>, which are unusual compared to other metal carbonyls.<ref name="Alberto" /> |

||

==Isotopes== |

|||

{{main |

{{main|Isotopes of technetium}} |

||

Technetium, with [[atomic number]] |

Technetium, with [[atomic number]] ''Z'' = 43, is the lowest-numbered element in the periodic table for which all isotopes are [[radioactive]]. The second-lightest exclusively radioactive element, [[promethium]], has atomic number 61.<ref name=LANL/> [[Atomic nucleus|Atomic nuclei]] with an odd number of [[proton]]s are less stable than those with even numbers, even when the total number of [[nucleon]]s (protons + [[neutron]]s) is even,<ref>{{cite book |last=Clayton |first=D.D. |date=1983 |title=Principles of stellar evolution and nucleosynthesis: with a new preface |publisher=University of Chicago Press |isbn=978-0-226-10953-4 |url=https://archive.org/details/principlesofstel0000clay |url-access=registration |page=[https://archive.org/details/principlesofstel0000clay/page/547 547] }}</ref> and odd numbered elements have fewer stable [[isotope]]s. |

||

The most stable [[Radionuclide|radioactive isotopes]] are technetium- |

The most stable [[Radionuclide|radioactive isotopes]] are technetium-97 with a [[half-life]] of {{val|4.21|0.16}} million years and technetium-98 with {{val|4.2|0.3}} million years; current measurements of their half-lives give overlapping [[confidence interval]]s corresponding to one [[standard deviation]] and therefore do not allow a definite assignment of technetium's most stable isotope. The next most stable isotope is technetium-99, which has a half-life of 211,100 years.{{NUBASE2020|ref}} Thirty-four other radioisotopes have been characterized with [[mass number]]s ranging from 86 to 122.{{NUBASE2020|ref}} Most of these have half-lives that are less than an hour, the exceptions being technetium-93 (2.73 hours), technetium-94 (4.88 hours), technetium-95 (20 hours), and technetium-96 (4.3 days).<ref name=CRCisotopes/> |

||

|url = http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/chart/ |

|||

|author = NNDC contributors |

|||

|editor = Sonzogni, A. A. |title = Chart of Nuclides |

|||

|publisher = National Nuclear Data Center, Brookhaven National Laboratory |

|||

|accessdate = 2009-11-11 |

|||

|date = 2008 |

|||

|location = New York}}</ref> Most of these have half-lives that are less than an hour, the exceptions being technetium-93 (half-life: 2.73 hours), technetium-94 (half-life: 4.88 hours), technetium-95 (half-life: 20 hours), and technetium-96 (half-life: 4.3 days).<ref name="CRCisotopes"/> |

|||

The primary [[decay mode]] for isotopes lighter than technetium-98 (<sup>98</sup>Tc) is [[electron capture]], producing [[molybdenum]] (''Z'' = 42).<ref name= |

The primary [[decay mode]] for isotopes lighter than technetium-98 (<sup>98</sup>Tc) is [[electron capture]], producing [[molybdenum]] (''Z'' = 42).<ref name=NNDC/> For technetium-98 and heavier isotopes, the primary mode is [[Beta decay|beta emission]] (the emission of an [[electron]] or [[positron]]), producing [[ruthenium]] (''Z'' = 44), with the exception that technetium-100 can decay both by beta emission and electron capture.<ref name=NNDC> |

||

{{cite web |

|||

|editor-last = Sonzogni |editor-first=A.A. |

|||

|title = Chart of nuclides |

|||

|series = National Nuclear Data Center |

|||

|publisher = [[Brookhaven National Laboratory]] |

|||

|place = Brookhaven, NY |

|||

|url = http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/chart/ |

|||

|access-date = 2009-11-11 |url-status = dead |

|||

|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090825001001/http://www.nndc.bnl.gov/chart/ |

|||

|archive-date = 2009-08-25 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref><ref> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|editor-last = Lide |editor-first=David R. |

|||

|date = 2004–2005 |

|||

|section = Table of the isotopes |

|||

|title = The CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics |

|||

|place = Boca Raton, FL |

|||

|publisher =CRC press |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Technetium also has numerous [[nuclear isomer]]s, which are isotopes with one or more [[Excited state|excited]] nucleons. Technetium-97m (<sup>97m</sup>Tc; |

Technetium also has numerous [[nuclear isomer]]s, which are isotopes with one or more [[Excited state|excited]] nucleons. Technetium-97m (<sup>97m</sup>Tc; "m" stands for [[metastability]]) is the most stable, with a half-life of 91 days and [[excited state|excitation energy]] 0.0965 MeV.<ref name=CRCisotopes> |

||

{{cite book |

|||

|last = Holden |

|last = Holden |first = N.E. |

||

|date = 2006 |

|||

|first=N. E. |

|||

|title = Handbook of Chemistry and Physics |

|title = Handbook of Chemistry and Physics |edition = 87th |

||

|editor = Lide |

|editor-last = Lide |editor-first = D.R. |

||

|publisher = CRC Press |

|||

|edition = 87th |

|||

|location = Boca Raton, FL |

|||

|date = 2006 |

|||

|pages = 11‑88 – 11‑89 |

|||

|publisher = CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group |

|||

|isbn = 978-0-8493-0487-3 |

|||

|location = Boca Raton, Florida |

|||

}} |

|||

|pages = 11–88–11–89 |

|||

</ref> |

|||

|isbn = 0-8493-0487-3}}</ref> This is followed by technetium-95m (half-life: 61 days, 0.03 MeV), and technetium-99m (half-life: 6.01 hours, 0.142 MeV).<ref name="CRCisotopes"/> Technetium-99m emits only [[gamma ray]]s and decays to technetium-99.<ref name="CRCisotopes"/> |

|||

This is followed by technetium-95m (61 days, 0.03 MeV), and technetium-99m (6.01 hours, 0.142 MeV).<ref name="CRCisotopes" /> |

|||

Technetium-99 (<sup>99</sup>Tc) is a major product of the fission of uranium-235 (<sup>235</sup>U), making it the most common and most readily available isotope of technetium. One gram of technetium-99 produces 6. |

Technetium-99 (<sup>99</sup>Tc) is a major product of the fission of uranium-235 (<sup>235</sup>U), making it the most common and most readily available isotope of technetium. One gram of technetium-99 produces {{nobr|6.2 × {{10^|8}} disintegrations}} per second (in other words, the [[specific activity]] of <sup>99</sup>Tc is 0.62 G[[Becquerel|Bq]]/g).<ref name=enc/> |

||

==Occurrence and production== |

==Occurrence and production== |

||

Technetium occurs naturally in the Earth's [[Crust (geology)|crust]] in minute concentrations of about 0.003 parts per trillion. Technetium is so rare because the [[half-life|half-lives]] of <sup>97</sup>Tc and <sup>98</sup>Tc are only {{nobr|4.2 million years.}} More than a thousand of such periods have passed since the formation of the [[Earth]], so the probability of survival of even one atom of [[primordial nuclide|primordial]] technetium is effectively zero. However, small amounts exist as spontaneous [[fission product]]s in [[uranium ore]]s. A kilogram of uranium contains an estimated 1 [[Orders of magnitude (mass)|nanogram]] {{nobr|({{10^|−9}} g)}} equivalent to ten trillion atoms of technetium.<ref name=blocks/><ref> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|last1=Dixon |first1=P. |last2=Curtis |first2=David B. |

|||

|last3=Musgrave |first3=John |last4=Roensch |first4=Fred |

|||

|last5=Roach |first5=Jeff |last6=Rokop |first6=Don |

|||

|date=1997 |

|||

|title=Analysis of naturally produced technetium and plutonium in geologic materials |

|||

|journal=Analytical Chemistry |

|||

|volume=69 |issue=9 |pages=1692–1699 |

|||

|doi=10.1021/ac961159q |pmid=21639292 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref><ref> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|last1=Curtis |first1=D. |last2=Fabryka-Martin |first2=June |

|||

|last3=Dixon |first3=Paul |last4=Cramer |first4=Jan |

|||

|date=1999 |

|||

|title=Nature's uncommon elements: Plutonium and technetium |

|||

|journal=Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta |

|||

|volume=63 |issue=2 |page=275 |

|||

|bibcode=1999GeCoA..63..275C |

|||

|doi=10.1016/S0016-7037(98)00282-8 |

|||

|url=https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc704244/ |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Some [[red giant]] stars with the spectral types S-, M-, and N display a spectral absorption line indicating the presence of technetium.{{sfn|Hammond|2004|p={{page needed|date=June 2021}}}}<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1126/science.114.2951.59|date=1951 |last1=Moore|first1=C. E.|title=Technetium in the Sun|journal=Science |volume=114 |issue=2951 |pages=59–61 |pmid=17782983|bibcode=1951Sci...114...59M}}</ref><!--Technetium in Red Giant Stars P Merrill — Science, 1952--> These red giants are known informally as [[technetium star]]s. |

|||

===Fission waste product=== |

===Fission waste product=== |

||

In contrast to the rare natural occurrence, bulk quantities of technetium-99 are produced each year from [[spent nuclear fuel|spent nuclear fuel rods]], which contain various fission products. The fission of a gram of [[uranium-235]] in [[nuclear reactor]]s yields 27 mg of technetium-99, giving technetium a [[fission product yield]] of 6.1%.<ref name=enc/> Other [[fissile]] isotopes produce similar yields of technetium, such as 4.9% from [[uranium-233]] and 6.21% from [[plutonium-239]]. |

In contrast to the rare natural occurrence, bulk quantities of technetium-99 are produced each year from [[spent nuclear fuel|spent nuclear fuel rods]], which contain various fission products. The fission of a gram of [[uranium-235]] in [[nuclear reactor]]s yields 27 mg of technetium-99, giving technetium a [[fission product yield]] of 6.1%.<ref name="enc" /> Other [[fissile]] isotopes produce similar yields of technetium, such as 4.9% from [[uranium-233]] and 6.21% from [[plutonium-239]].{{sfn|Schwochau|2000|pp=374–404}} An estimated 49,000 T[[Becquerel|Bq]] (78 [[tonne|metric tons]]) of technetium was produced in nuclear reactors between 1983 and 1994, by far the dominant source of terrestrial technetium.<ref name=yoshihara> |

||

{{cite book |

|||

|last=Yoshihara |first=K. |

|||

|date=1996 |

|||

|chapter=Technetium in the environment |

|||

|editor1-last=Yoshihara |editor1-first=K. |

|||

|editor2-last=Omori |editor2-first=T. |

|||

|title=Technetium and Rhenium: Their chemistry and its applications |

|||

|series=Topics in Current Chemistry |volume=176 |

|||

|publisher=Springer-Verlag |

|||

|location=Berlin / Heidelberg, DE |

|||

|isbn=978-3-540-59469-7 |

|||

|doi=10.1007/3-540-59469-8_2 |

|||

|pages=17–35 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref><ref name=leon/> |

|||

Only a fraction of the production is used commercially.{{efn| |

|||

{{As of|2005}}, technetium-99 in the form of [[ammonium pertechnetate]] is available to holders of an [[Oak Ridge National Laboratory]] permit.{{sfn|Hammond|2004|p={{page needed|date=June 2021}}}} |

|||

}} |

|||

Technetium-99 is produced by the [[nuclear fission]] of both uranium-235 and plutonium-239. It is therefore present in [[radioactive waste]] and in the [[nuclear fallout]] of [[nuclear weapon|fission bomb]] explosions. Its decay, measured in [[becquerel]]s per amount of spent fuel, is the dominant contributor to nuclear waste radioactivity after about {{nobr|{{10^|4}}~{{10^|6}} years}} after the creation of the nuclear waste.<ref name=yoshihara/> From 1945–1994, an estimated 160 T[[Becquerel|Bq]] (about 250 kg) of technetium-99 was released into the environment during atmospheric [[nuclear test]]s.<ref name=yoshihara/><ref> |

|||

Technetium-99 is produced by the [[nuclear fission]] of both uranium-235 and plutonium-239. It is therefore present in [[radioactive waste]] and in the [[nuclear fallout]] of [[nuclear weapon|fission bomb]] explosions. Its decay, measured in [[becquerel]]s per amount of spent fuel, is the dominant contributor to nuclear waste radioactivity after about 10<sup>4</sup> to 10<sup>6</sup> years after the creation of the nuclear waste.<ref name="yoshihara"/> From 1945 to 1994, an estimated 160 T[[Becquerel|Bq]] (about 250 kg) of technetium-99 was released into the environment during atmospheric [[nuclear test]]s.<ref name="yoshihara"/><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=QLHr-UYWoo8C&pg=PA69|page=69|title=Technetium in the environment|last1=Desmet |first1=G. |last2=Myttenaere |first2=C.|publisher=Springer|date=1986|isbn=0-85334-421-3}}</ref> The amount of technetium-99 from nuclear reactors released into the environment up to 1986 is on the order of 1000 TBq (about 1600 kg), primarily by [[nuclear fuel reprocessing]]; most of this was discharged into the sea. Reprocessing methods have reduced emissions since then, but as of 2005 the primary release of technetium-99 into the environment is by the [[Sellafield]] plant, which released an estimated 550 TBq (about 900 kg) from 1995–1999 into the [[Irish Sea]].<ref name=leon>{{cite journal|url=http://www.radiochem.org/paper/JN63/jn6326.pdf|journal=Journal of Nuclear and Radiochemical Sciences|volume=6|issue=3|pages=253–259|date=2005|title=99Tc in the Environment: Sources, Distribution and Methods|last=Garcia-Leon |first=M.}}</ref> From 2000 onwards the amount has been limited by regulation to 90 TBq (about 140 kg) per year.<ref>{{cite journal|title = Technetium-99 Behaviour in the Terrestrial Environment — Field Observations and Radiotracer Experiments|first = K.|last = Tagami|journal=Journal of Nuclear and Radiochemical Sciences|volume = 4|pages= A1–A8|date = 2003|doi=10.14494/jnrs2000.4.a1}}</ref> Discharge of technetium into the sea resulted in contamination of some seafood with minuscule quantities of this element. For example, [[European lobster]] and fish from west [[Cumbria]] contain about 1 Bq/kg of technetium.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=zVmdln2pJxUC&pg=PA403|page=403|title=Mineral components in foods|last1=Szefer |first1=P. |last2=Nriagu |first2=J. O.|publisher=CRC Press|date=2006|isbn=0-8493-2234-0}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal| title = Gut transfer and doses from environmental technetium|first1=J. D.|last1 = Harrison|first2 = A.|last2 = Phipps|date = 2001|journal = J. Radiol. Prot.|pages= 9–11| volume = 21 |doi = 10.1088/0952-4746/21/1/004| pmid = 11281541| issue = 1|bibcode = 2001JRP....21....9H }}</ref><ref group=note>The [[anaerobic organism|anaerobic]], [[endospore|spore]]-forming [[bacteria]] in the ''[[Clostridium]]'' [[genus]] are able to reduce Tc(VII) to Tc(IV). ''Clostridia'' bacteria play a role in reducing iron, [[manganese]], and uranium, thereby affecting these elements' solubility in soil and sediments. Their ability to reduce technetium may determine a large part of mobility of technetium in industrial wastes and other subsurface environments. {{cite journal| last1=Francis |first1=A. J. |last2=Dodge |first2=C. J. |last3=Meinken |first3=G. E.|title = Biotransformation of pertechnetate by ''Clostridia'' |journal = Radiochimica Acta|volume = 90| date= 2002|pages = 791–797|doi= 10.1524/ract.2002.90.9-11_2002.791| issue=9–11}}</ref> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|last1=Desmet |first1=G. |

|||

|last2=Myttenaere |first2=C. |

|||

|date=1986 |

|||

|title=Technetium in the Environment |

|||

|publisher=Springer |

|||

|isbn=978-0-85334-421-6 |

|||

|page=69 |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QLHr-UYWoo8C&pg=PA69 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

The amount of technetium-99 from nuclear reactors released into the environment up to 1986 is on the order of 1000 TBq (about 1600 kg), primarily by [[nuclear fuel reprocessing]]; most of this was discharged into the sea. Reprocessing methods have reduced emissions since then, but as of 2005 the primary release of technetium-99 into the environment is by the [[Sellafield]] plant, which released an estimated 550 TBq (about 900 kg) from 1995 to 1999 into the [[Irish Sea]].<ref name=leon> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|last=Garcia-Leon |first=M. |

|||

|date=2005 |

|||

|title={{sup|99}}Tc in the environment: Sources, distribution, and methods |

|||

|journal=Journal of Nuclear and Radiochemical Sciences |

|||

|volume=6 |issue=3 |pages=253–259 |

|||

|doi=10.14494/jnrs2000.6.3_253 |doi-access=free |

|||

|url=http://www.radiochem.org/paper/JN63/jn6326.pdf |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

From 2000 onwards the amount has been limited by regulation to 90 TBq (about 140 kg) per year.<ref> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|first=K. |last=Tagami |

|||

|date=2000 |

|||

|title=Technetium-99 behaviour in the terrestrial environment — field observations and radiotracer experiments |

|||

|journal=Journal of Nuclear and Radiochemical Sciences |

|||

|volume=4 |pages=A1–A8 |

|||

|doi=10.14494/jnrs2000.4.a1 |doi-access=free |

|||

|url=https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jnrs2000/4/1/4_1_A1/_pdf |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Discharge of technetium into the sea resulted in contamination of some seafood with minuscule quantities of this element. For example, [[European lobster]] and fish from west [[Cumbria]] contain about 1 Bq/kg of technetium.<ref> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zVmdln2pJxUC&pg=PA403 |

|||

|page=403 |

|||

|title=Mineral Components in Foods |

|||

|last1=Szefer |first1=P. |

|||

|last2=Nriagu |first2=J.O. |

|||

|publisher=CRC Press |

|||

|date=2006 |

|||

|isbn=978-0-8493-2234-1 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref><ref> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|first1=J.D. |last1=Harrison |

|||

|first2=A. |last2=Phipps |

|||

|date=2001 |

|||

|title=Gut transfer and doses from environmental technetium |

|||

|journal=Journal of Radiological Protection |

|||

|volume=21 |issue=1 |pages=9–11 |

|||

|doi=10.1088/0952-4746/21/1/004 |

|||

|bibcode=2001JRP....21....9H |

|||

|pmid=11281541 |s2cid=250752077 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref>{{efn| |

|||

The [[anaerobic organism|anaerobic]], [[endospore|spore]]-forming [[bacteria]] in the ''[[Clostridium]]'' [[genus]] are able to reduce Tc(VII) to Tc(IV). ''Clostridia'' bacteria play a role in reducing iron, [[manganese]], and uranium, thereby affecting these elements' solubility in soil and sediments. Their ability to reduce technetium may determine a large part of mobility of technetium in industrial wastes and other subsurface environments.<ref> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|last1=Francis |first1=A.J. |

|||

|last2=Dodge |first2=C.J. |

|||

|last3=Meinken |first3=G.E. |

|||

|date=2002 |

|||

|title=Biotransformation of pertechnetate by ''Clostridia'' |

|||

|journal=Radiochimica Acta |

|||

|volume=90 |issue=9–11 |pages=791–797 |

|||

|doi= 10.1524/ract.2002.90.9-11_2002.791 |

|||

|s2cid=83759112 |

|||

|url=https://zenodo.org/record/1236279 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

===Fission product for commercial use=== |

===Fission product for commercial use=== |

||

The [[Metastability|metastable]] isotope technetium-99m is continuously produced as a [[fission product]] from the fission of uranium or [[plutonium]] in [[nuclear reactor]]s: |

The [[Metastability|metastable]] isotope technetium-99m is continuously produced as a [[fission product]] from the fission of uranium or [[plutonium]] in [[nuclear reactor]]s: |

||

:<math>\mathrm{ ^{238}_{\ 92}U\ \xrightarrow {sf}\ ^{137}_{\ 53} I + ^{99}_{39} Y + 2\, ^{1}_{0} n } </math> |

|||

<chem display="block"> ^{238}_{92}U ->[\ce{sf}] ^{137}_{53}I + ^{99}_{39}Y + 2^{1}_{0}n</chem> |

|||

:<math>\mathrm{ ^{99}_{39}Y\ \xrightarrow [1{,}47\,s]{\beta^{-}} \ ^{99}_{40}Zr\ \xrightarrow [2{,}1\,s]{\beta^{-}} \ ^{99}_{41}Nb\ \xrightarrow [15{,}0\,s]{\beta^{-}} \ ^{99}_{42}Mo\ \xrightarrow [65{,}94\, h]{\beta^-} \ ^{99}_{43}Tc\ \xrightarrow [211100\,a] {\beta^{-}} \ ^{99}_{44}Ru } </math> |

|||

<chem display="block"> ^{99}_{39}Y ->[\beta^-][1.47\,\ce{s}] ^{99}_{40}Zr ->[\beta^-][2.1\,\ce{s}] ^{99}_{41}Nb ->[\beta^-][15.0\,\ce{s}] ^{99}_{42}Mo ->[\beta^-][65.94\,\ce{h}] ^{99}_{43}Tc ->[\beta^-][211,100\,\ce{y}] ^{99}_{44}Ru</chem> |

|||

Because used fuel is allowed to stand for several years before reprocessing, all molybdenum-99 and technetium-99m is decayed by the time that the fission products are separated from the major [[actinide]]s in conventional [[nuclear reprocessing]]. The liquid left after plutonium–uranium extraction ([[PUREX]]) contains a high concentration of technetium as {{chem|TcO|4|-}} but almost all of this is technetium-99, not technetium-99m. |

Because used fuel is allowed to stand for several years before reprocessing, all molybdenum-99 and technetium-99m is decayed by the time that the fission products are separated from the major [[actinide]]s in conventional [[nuclear reprocessing]]. The liquid left after plutonium–uranium extraction ([[PUREX]]) contains a high concentration of technetium as {{chem|TcO|4|-}} but almost all of this is technetium-99, not technetium-99m.{{sfn|Schwochau|2000|p=39}} |

||

The vast majority of the technetium-99m used in medical work is produced by irradiating dedicated [[enriched uranium#Highly enriched uranium (HEU)|highly enriched uranium]] targets in a reactor, extracting molybdenum-99 from the targets in reprocessing facilities,<ref name=nuclmed>{{cite journal|last=Moore|first=P. W.|title=Technetium-99 in generator systems|journal=Journal of Nuclear Medicine |date=April 1984|volume=25 |issue=4|pages=499–502 |pmid=6100549|url=http://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/25/4/499.full.pdf| |

The vast majority of the technetium-99m used in medical work is produced by irradiating dedicated [[enriched uranium#Highly enriched uranium (HEU)|highly enriched uranium]] targets in a reactor, extracting molybdenum-99 from the targets in reprocessing facilities,<ref name="nuclmed">{{cite journal|last=Moore |first=P. W.|title=Technetium-99 in generator systems|journal=Journal of Nuclear Medicine |date=April 1984 |volume=25 |issue=4|pages=499–502 |pmid=6100549|url=http://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/25/4/499.full.pdf |access-date=2012-05-11}}</ref> and recovering at the diagnostic center the technetium-99m produced upon decay of molybdenum-99.<ref>{{cite patent|country=US |number=3799883|title=Silver coated charcoal step |invent1=Hirofumi Arino|assign1= Union Carbide Corporation|gdate=March 26, 1974}}</ref><ref>{{cite book| title = Medical Isotope Production Without Highly Enriched Uranium| author=Committee on Medical Isotope Production Without Highly Enriched Uranium| publisher=National Academies Press|page=vii |isbn=978-0-309-13040-0|date=2009}}</ref> Molybdenum-99 in the form of molybdate {{chem|MoO|4|2-}} is [[adsorption|adsorbed]] onto acid alumina ({{chem|Al|2|O|3}}) in a [[radiation shielding|shielded]] [[column chromatography|column chromatograph]] inside a [[technetium-99m generator]] ("technetium cow", also occasionally called a "molybdenum cow"). Molybdenum-99 has a half-life of 67 hours, so short-lived technetium-99m (half-life: 6 hours), which results from its decay, is being constantly produced.<ref name="blocks" /> The soluble [[pertechnetate]] {{chem|TcO|4|-}} can then be chemically extracted by [[elution]] using a [[saline solution]]. A drawback of this process is that it requires targets containing uranium-235, which are subject to the security precautions of fissile materials.<ref>{{cite news |last=Lützenkirchen |first=K.-R. |title=Nuclear forensics sleuths trace the origin of trafficked material |url=http://arq.lanl.gov/source/orgs/nmt/nmtdo/AQarchive/4thQuarter07/page1.shtml |publisher=Los Alamos National Laboratory |access-date=2009-11-11 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130216114404/http://arq.lanl.gov/source/orgs/nmt/nmtdo/AQarchive/4thQuarter07/page1.shtml |archive-date=2013-02-16}}</ref><ref>{{cite conference|last1=Snelgrove|first1=J. L.|first2=G. L. |last2=Hofman |url=http://www.rertr.anl.gov/MO99/JLS.pdf|title=Development and Processing of LEU Targets for Mo-99 Production| date=1995| access-date=2009-05-05 |work=ANL.gov |conference=1995 International Meeting on Reduced Enrichment for Research and Test Reactors, September 18–21, 1994, Paris, France}}</ref> |

||

[[File:First technetium-99m generator - 1958.jpg|thumb| |

[[File:First technetium-99m generator - 1958.jpg|thumb|upright|The first [[technetium-99m generator]], unshielded, 1958. A Tc-99m [[pertechnetate]] solution is being eluted from Mo-99 [[molybdate]] bound to a chromatographic substrate]] |

||

Almost two-thirds of the world's supply comes from two reactors; the [[National Research Universal Reactor]] at [[Chalk River Laboratories]] |

Almost two-thirds of the world's supply comes from two reactors; the [[National Research Universal Reactor]] at [[Chalk River Laboratories]] in Ontario, Canada, and the [[Petten nuclear reactor|High Flux Reactor]] at [[Nuclear Research and Consultancy Group]] in Petten, Netherlands. All major reactors that produce technetium-99m were built in the 1960s and are close to the [[End-of-life (product)|end of life]]. The two new Canadian [[Multipurpose Applied Physics Lattice Experiment]] reactors planned and built to produce 200% of the demand of technetium-99m relieved all other producers from building their own reactors. With the cancellation of the already tested reactors in 2008, the future supply of technetium-99m became problematic.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Thomas | first1 = Gregory S. | last2 = Maddahi | first2 = Jamshid | title = The technetium shortage | journal = [[Journal of Nuclear Cardiology]] | volume = 17 | pages = 993–8 | date = 2010 | doi = 10.1007/s12350-010-9281-8 | issue = 6 | pmid=20717761| s2cid = 2397919 }}</ref> |

||