Bagan: Difference between revisions

Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.6.1) (Balon Greyjoy) |

m Open access bot: hdl updated in citation with #oabot. |

||

| (153 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|UNESCO historical city in Mandalay Region, Myanmar}} |

|||

{{About|a city in Myanmar|}} |

{{About|a city in Myanmar|}} |

||

{{Infobox settlement |

{{Infobox settlement |

||

|native_name= |

| native_name = ပုဂံ |

||

|official_name=Bagan |

| official_name = Bagan |

||

|other_name=Pagan |

| other_name = Pagan |

||

|pushpin_label_position=right |

| pushpin_label_position = right |

||

|pushpin_map= |

| pushpin_map = Burma |

||

|pushpin_map_caption=Location of Bagan, Myanmar |

| pushpin_map_caption = Location of Bagan, Myanmar |

||

|image_skyline=Bagan, Burma.jpg |

| image_skyline = Bagan, Burma.jpg |

||

|imagesize= |

| imagesize = |

||

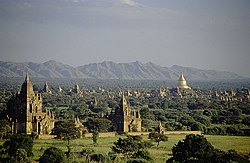

|image_caption=Temples in Bagan |

| image_caption = Temples and pagodas in Bagan |

||

|image_map= |

| image_map = |

||

|map_caption= |

| map_caption = |

||

|established_date=mid-to-late 9th century |

| established_date = mid-to-late 9th century |

||

|established_title=Founded |

| established_title = Founded |

||

|subdivision_type=Country |

| subdivision_type = Country |

||

|subdivision_name=[[Myanmar]] |

| subdivision_name = [[Myanmar]] |

||

|subdivision_type1=[[Administrative divisions of Myanmar|Region]] |

| subdivision_type1 = [[Administrative divisions of Myanmar|Region]] |

||

|subdivision_name1=[[Mandalay Region]] |

| subdivision_name1 = [[Mandalay Region]] |

||

|unit_pref= |

| unit_pref = |

||

|area_total_km2=104 |

| area_total_km2 = 104 |

||

|population= |

| population = |

||

|population_as_of= |

| population_as_of = |

||

|population_blank1=[[Bamar]] |

| population_blank1 = [[Bamar people]] |

||

|population_blank1_title=Ethnicities |

| population_blank1_title = Ethnicities |

||

|population_blank2=[[Theravada Buddhism]] |

| population_blank2 = [[Theravada Buddhism]] |

||

|population_blank2_title=Religions |

| population_blank2_title = Religions |

||

|population_density_km2=auto |

| population_density_km2 = auto |

||

|coordinates = {{coord|21|10|N|94| |

| coordinates = {{coord|21|10|21|N|94|51|36|E|region:MM|display=inline,title}} |

||

|elevation_ft= |

| elevation_ft = |

||

|elevation_m= |

| elevation_m = |

||

|timezone=[[Time in Myanmar|MST]] |

| timezone = [[Time in Myanmar|MST]] |

||

|utc_offset=+6.30 |

| utc_offset = +6.30 |

||

|website= |

| website = |

||

{{Infobox UNESCO World Heritage Site |

|||

|child = yes |

|||

|Official_name = Bagan |

|||

|Location = [[Mandalay Region]], [[Myanmar]] |

|||

|ID = 1588 |

|||

|Year = 2019 |

|||

|Criteria = Cultural: iii, iv, vi |

|||

|Area= {{cvt|5005.49|ha}} |

|||

|Buffer_zone = {{cvt|18146.83|ha}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Bagan''' ({{MYname|MY=ပုဂံ|MLCTS=pu.gam}}, {{IPA-my|bəɡàɴ|IPA}}; formerly '''Pagan''') is an ancient city located in the [[Mandalay Region]] of [[Myanmar]]. From the 9th to 13th centuries, the city was the capital of the [[Pagan Kingdom]], the first kingdom that unified the regions that would later constitute modern Myanmar. During the kingdom's height between the 11th and 13th centuries, over 10,000 [[Buddhism|Buddhist]] temples, [[pagoda]]s and monasteries were constructed in the Bagan plains alone, of which the remains of over 2,200 temples and pagodas still survive to the present day. |

|||

'''Bagan''' ({{MYname|MY=ပုဂံ|MLCTS=pu.gam}}, {{IPA-my|bəɡàɰ̃|IPA}}; formerly '''Pagan''') is an ancient city and a UNESCO [[World Heritage Site]] in the [[Mandalay Region]] of [[Myanmar]].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/2004/ |title=Seven more cultural sites added to UNESCO's World Heritage List |website=UNESCO |date=6 July 2019 |access-date=6 July 2019 |archive-date=14 July 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190714072717/http://whc.unesco.org/en/news/2004/ |url-status=live }}</ref> From the 9th to 13th centuries, the city was the capital of the [[Pagan Kingdom]], the first kingdom that unified the regions that would later constitute Myanmar. During the kingdom's height between the 11th and 13th centuries, more than 10,000 [[Buddhist temples]], [[Burmese pagoda|pagodas]] and [[Kyaung|monasteries]] were constructed in the Bagan plains alone,<ref name="dms-216" /> of which the remains of over 2200 temples and pagodas survive. |

|||

The '''Bagan Archaeological Zone''' is a main attraction for [[Tourism in Burma|the country's nascent tourism industry]]. It is seen by many as equal in attraction to [[Angkor Wat]] in Cambodia.<ref>https://www.economist.com/news/special-report/21578171-why-investors-still-need-proceed-caution-promiseand-pitfalls Business: The promise—and the pitfalls</ref> |

|||

The '''Bagan Archaeological Zone''' is a main attraction for [[Tourism in Myanmar|the country's nascent tourism industry]].<ref name=te>{{cite news |url=https://www.economist.com/news/special-report/21578171-why-investors-still-need-proceed-caution-promiseand-pitfalls |title=Business: The promise—and the pitfalls |newspaper=The Economist |date=25 May 2013 |access-date=2018-11-26 |archive-date=2017-11-07 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171107004718/https://www.economist.com/news/special-report/21578171-why-investors-still-need-proceed-caution-promiseand-pitfalls |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

==Etymology== |

==Etymology== |

||

Bagan is the present-day [[Burmese dialects# |

Bagan is the present-day [[Burmese dialects#Dialects|standard Burmese pronunciation]] of the Burmese word ''Pugan'' ({{lang-my-Mymr|ပုဂံ}}), derived from [[Old Burmese]] ''Pukam'' ({{lang-my-Mymr|ပုကမ်}}). Its classical [[Pali]] name is ''[[Arimaddana]]pura'' ({{lang-my-Mymr|အရိမဒ္ဒနာပူရ}}, lit. "the City that Tramples on Enemies"). Its other names in Pali are in reference to its extreme dry zone climate: ''Tattadesa'' ({{lang-my-Mymr|တတ္တဒေသ}}, "parched land"), and ''Tampadīpa'' ({{lang-my-Mymr|တမ္ပဒီပ}}, "bronzed country").<ref name="tt-117-118">Than Tun 1964: 117–118</ref> The [[Burmese chronicles]] also report other classical names of ''[[Thiri Pyissaya]]'' ({{lang-my-Mymr|သီရိပစ္စယာ}}; {{langx|pi|Siripaccaya}}) and ''[[Tampawaddy]]'' ({{lang-my-Mymr|တမ္ပဝတီ}}; {{langx|pi|Tampavatī}}).<ref name="my-1-139-141">Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 139–141</ref> |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

===9th to 13th centuries=== |

===9th to 13th centuries=== |

||

{{Main |

{{Main|Early Pagan Kingdom|Pagan Kingdom}} |

||

[[File:Bagan Sunset.jpg|thumb|300px|left|Bagan's prosperous economy built over 10,000 temples between the 11th and 13th centuries.]] |

[[File:Bagan Sunset.jpg|thumb|300px|left|Bagan's prosperous economy built over 10,000 temples between the 11th and 13th centuries.]] |

||

[[File:Pagan Empire -- Sithu II.PNG|thumb|150px|Pagan Empire c. 1210]] |

[[File:Pagan Empire -- Sithu II.PNG|thumb|150px|Pagan Empire c. 1210]] |

||

According to the [[Burmese chronicles]], Bagan was founded in the second century |

According to the [[Burmese chronicles|royal chronicles]], Bagan was founded in the second century CE, and fortified in 849 by King [[Pyinbya]], 34th successor of the founder of early Bagan.<ref name="geh-18">Harvey 1925: 18</ref> Western scholarship however holds that Bagan was founded in the mid-to-late 9th century by the [[Bamar|Mranma]] (Burmans), who had recently entered the Irrawaddy valley from the [[Nanzhao Kingdom]]. It was among several competing [[Pyu city-states]] until the late 10th century when the Burman settlement grew in authority and grandeur.<ref name="vbl-90-91">Lieberman 2003: 90–91</ref> |

||

From 1044 to 1287, Bagan was the capital as well as the political, economic and cultural nerve center of the [[Pagan Empire]]. Over the course of 250 years, Bagan's rulers and their wealthy subjects constructed over 10,000 religious monuments (approximately 1000 stupas, 10,000 small temples and 3000 monasteries)<ref name="dms-216">Stadtner 2011: 216</ref> in an area of {{ |

From 1044 to 1287, Bagan was the capital as well as the political, economic and cultural nerve center of the [[Pagan Empire|Bagan Empire]]. Over the course of 250 years, Bagan's rulers and their wealthy subjects constructed over 10,000 religious monuments (approximately 1000 stupas, 10,000 small temples and 3000 monasteries)<ref name="dms-216">Stadtner 2011: 216</ref> in an area of {{cvt|104|km2|sqmi}} in the Bagan plains. The prosperous city grew in size and grandeur, and became a cosmopolitan center for religious and secular studies, specializing in Pali scholarship in grammar and philosophical-psychological (''[[abhidhamma]]'') studies as well as works in a variety of languages on [[Prosody (linguistics)|prosody]], [[phonology]], grammar, [[astrology]], [[alchemy]], medicine, and legal studies.<ref name="vbl-115-116">Lieberman 2003: 115–116</ref> The city attracted monks and students from as far as [[India]], [[Sri Lanka]] and the [[Khmer Empire]]. |

||

The culture of Bagan was dominated by religion. The religion of Bagan was fluid, syncretic and by later standards, unorthodox. It was largely a continuation of religious trends in the [[Pyu city-states|Pyu era]] where [[Theravada Buddhism]] co-existed with [[Mahayana Buddhism]], [[Tantric Buddhism]], various Hindu ([[Shaivism|Saivite]], and [[Vaishnavism|Vaishana]]) schools as well as native animist (''[[nat (spirit)|nat]]'') traditions. While the royal patronage of Theravada Buddhism since the mid-11th century had enabled the Buddhist school to gradually gain primacy, other traditions continued to thrive throughout the Pagan period to degrees later unseen.<ref name="vbl-115-116"/> |

The culture of Bagan was dominated by religion. The religion of Bagan was fluid, syncretic and by later standards, unorthodox. It was largely a continuation of religious trends in the [[Pyu city-states|Pyu era]] where [[Theravada Buddhism]] co-existed with [[Mahayana Buddhism]], [[Tantric Buddhism]], various Hindu ([[Shaivism|Saivite]], and [[Vaishnavism|Vaishana]]) schools as well as native animist (''[[nat (spirit)|nat]]'') traditions. While the royal patronage of Theravada Buddhism since the mid-11th century had enabled the Buddhist school to gradually gain primacy, other traditions continued to thrive throughout the Pagan period to degrees later unseen.<ref name="vbl-115-116"/> |

||

Bagan's basic physical layout had already taken shape by the late 11th century, which was the first major period of monument building.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 51-2 --> A main strip extending for about 9 km along the east bank of the Irrawaddy emerged during this period, with the walled core (known as "Old Bagan") in the middle.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 51 --> 11th-century construction took place throughout this whole area and appears to have been relatively decentralized.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 51 --> The spread of monuments north and south of Old Bagan, according to Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung, may reflect construction at the village level,<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 62 --> which may have been encouraged by the main elite at Old Bagan.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 51 --><ref name="Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001"/>{{rp|51}} |

|||

The Pagan Empire collapsed in 1287 due to repeated [[First Mongol invasion of Burma|Mongol invasions]] (1277–1301). Recent research shows that Mongol armies may not have reached Bagan itself, and that even if they did, the damage they inflicted was probably minimal.<ref name="vbl-119-120">[[Victor Lieberman|Lieberman]] 2003: 119–120</ref> However, the damage had already been done. The city, once home to some 50,000 to 200,000 people, had been reduced to a small town, never to regain its preeminence. The city formally ceased to be the capital of Burma in December 1297 when the [[Myinsaing Kingdom]] became the new power in Upper Burma.<ref name="mha-74">Htin Aung 1967: 74</ref><ref name="tt-1959-119-120">Than Tun 1959: 119–120</ref> |

|||

The peak of monument building took place between about 1150 and 1200.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 50-1 --> Most of Bagan's largest buildings were built during this period.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 51 --> The overall amount of building material used also peaked during this phase.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 50-1 --> Construction clustered around Old Bagan, but also took place up and down the main strip, and there was also some expansion to the east, away from the Irrawaddy.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 51 --><ref name="Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001"/>{{rp|50–1}} |

|||

By the 13th century, the area around Old Bagan was already densely packed with monuments, and new major clusters began to emerge to the east.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 51 --> These new clusters, like the monastic area of Minnanthu, were roughly equally distant – and equally accessible – from any part of the original strip that had been defined in the 11th century.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 51 --> Construction during the 13th century featured a significant increase in the building of monasteries and associated smaller monuments.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 52 --> Michael Aung-Thwin has suggested that the smaller sizes may indicate "dwindling economic resources" and that the clustering around monasteries may reflect growing monastic influence.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 52 --> Bob Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung also suggest that there was a broadening of donor activity during this period: "the religious merit that accrued from endowing an individual merit was more widely accessible", and more private individuals were endowing small monuments.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 52, 61 --> As with before, this may have taken place at the village level.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 62 --><ref name="Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001"/>{{rp|51–2, 61}} |

|||

Both Bagan itself and the surrounding countryside offered plenty of opportunities for employment in various sectors.<!-- Aung-Thwin 2005, p. 305 --> The prolific temple building alone would have been a huge stimulus for professions involved in their construction, such as brickmaking and masonry; gold, silver, and bronze working; carpentry and woodcarving; and ceramics.<!-- Aung-Thwin 2005, p. 305 --> Finished temples would still need maintenance work done, so they continued to boost demand for both artisans' services and unskilled labor well after their construction.<!-- Aung-Thwin 2005, p. 305 --> Accountants, bankers, and scribes were also necessary to manage the temple properties.<!-- Aung-Thwin 2005, p. 306 --> These workers, especially the artisans, were paid well, which attracted many people to move to Bagan.<!-- Aung-Thwin 2005, p. 305-7 --> Contemporary inscriptions indicate that "people of many linguistic and cultural backgrounds lived and worked" in Bagan during this time period.<!-- Aung-Thwin 2005, p. 306 --> |

|||

<ref name="Aung-Thwin 2005">{{cite book |last1=Aung-Thwin |first1=Michael |author1-link=Michael Aung-Thwin |title=The mists of Rāmañña: The Legend that was Lower Burma |date=2005 |publisher=University of Hawai'i Press |location=Honolulu |isbn=0-8248-2886-0 |url=https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/45339/1/625896.pdf |access-date=14 January 2024}}</ref>{{rp|305-7}} |

|||

Bagan's ascendancy also coincided with a period of political and economic decline in several other nearby regions, like Dvaravati, Srivijaya, and the Chola Empire.<!-- Aung-Thwin 2005, p. 306 --> As a result, immigrants from those places likely also ended up moving to Bagan, in addition to people moving there from within Myanmar.<!-- Aung-Thwin 2005, p. 306 --><ref name="Aung-Thwin 2005"/>{{rp|306}} |

|||

The Pagan Empire collapsed in 1287 due to repeated [[First Mongol invasion of Burma|Mongol invasions]] (1277–1301). Recent research shows that Mongol armies may not have reached Bagan itself, and that even if they did, the damage they inflicted was probably minimal.<ref name="vbl-119-120">[[Victor Lieberman|Lieberman]] 2003: 119–120</ref> According to [[Michael Aung-Thwin]], a more likely explanation is that the provincial governors tasked with defending against Mongol incursions were so successful that they became "the new power elite", and their capitals became the new political centers while Bagan itself became a backwater.<ref name="Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001"/>{{rp|53}} In any case, something during this period caused Bagan to decline. The city, once home to some 50,000 to 200,000 people, had been reduced to a small town, never to regain its preeminence. The city formally ceased to be the capital of Burma in December 1297 when the [[Myinsaing Kingdom]] became the new power in Upper Burma.<ref name="mha-74">Htin Aung 1967: 74</ref><ref name="tt-1959-119-120">Than Tun 1959: 119–120</ref> |

|||

===14th to 19th centuries=== |

===14th to 19th centuries=== |

||

| Line 63: | Line 86: | ||

===20th century to present=== |

===20th century to present=== |

||

[[File:Pumpkin Pagoda -Bupaya Pagoda-, Pagan, Upper Burma.jpg|thumb|The original Bupaya seen here in 1868 was completely destroyed by the 1975 earthquake. A new pagoda in the original shape |

[[File:Pumpkin Pagoda -Bupaya Pagoda-, Pagan, Upper Burma.jpg|thumb|The original Bupaya seen here in 1868 was completely destroyed by the 1975 earthquake. A new gilded pagoda in the original shape has been rebuilt.]] |

||

Bagan, located in an active earthquake zone, had suffered from many earthquakes over the ages, with over 400 recorded earthquakes between 1904 and 1975.<ref name="uc-28-ix">Unesco 1976: ix</ref> A [[1975 Bagan earthquake|major earthquake]] occurred on 8 July 1975, reaching 8 [[Mercalli intensity scale|MM]] in Bagan and [[Myinkaba]], and 7 MM in [[Nyaung-U]].<ref name="iy-ky">Ishizawa and Kono 1989: 114</ref> The quake damaged many temples, in many cases, such as the [[Bupaya Pagoda|Bupaya]], severely and irreparably. Today, 2229 temples and pagodas remain.<ref name="hk-ab-117">Köllner, Bruns 1998: 117</ref> |

Bagan, located in an active earthquake zone, had suffered from many earthquakes over the ages, with over 400 recorded earthquakes between 1904 and 1975.<ref name="uc-28-ix">Unesco 1976: ix</ref> A [[1975 Bagan earthquake|major earthquake]] occurred on 8 July 1975, reaching 8 [[Mercalli intensity scale|MM]] in Bagan and [[Myinkaba]], and 7 MM in [[Nyaung-U]].<ref name="iy-ky">Ishizawa and Kono 1989: 114</ref> The quake damaged many temples, in many cases, such as the [[Bupaya Pagoda|Bupaya]], severely and irreparably. Today, 2229 temples and pagodas remain.<ref name="hk-ab-117">Köllner, Bruns 1998: 117</ref> |

||

Many of these damaged pagodas underwent restorations in the 1990s by the [[State Peace and Development Council|military government]], which sought to make Bagan an international tourist destination. However, the restoration efforts instead drew widespread condemnation from art historians and preservationists worldwide. Critics |

Many of these damaged pagodas underwent restorations in the 1990s by the [[State Peace and Development Council|military government]], which sought to make Bagan an international tourist destination. However, the restoration efforts instead drew widespread condemnation from art historians and preservationists worldwide. Critics were aghast that the restorations paid little attention to original architectural styles, and used modern materials, and that the government has also established a [[golf course]], a paved highway, and built a {{cvt|61|m}} watchtower. Although the government believed that the ancient capital's hundreds of (unrestored) temples and large corpus of stone inscriptions were more than sufficient to win the designation of UNESCO World Heritage Site,<ref name="unesco-whs">Unesco 1996</ref> the city was not so designated until 2019, allegedly mainly on account of the restorations.<ref name=jbt>Tourtellot 2004</ref> |

||

On 24 August 2016, a [[August 2016 Myanmar earthquake|major earthquake]] hit Bagan, and caused major damages in nearly 400 temples. The [[Sulamani Temple|Sulamani]] and Myauk Guni temples were severely damaged. The Bagan Archaeological Department began a survey and reconstruction effort with the help of the UNESCO. Visitors were prohibited from entering 33 much-damaged temples. |

|||

Bagan today is a main tourist destination in the country's nascent tourism industry, which has long been the target of various boycott campaigns. The majority of over 300,000 international tourists to the country in 2011 are believed to have also visited Bagan.{{citation needed|date=February 2016}} Several Burmese publications note that the city's small tourism infrastructure will have to expand rapidly even to meet a modest pickup in tourism in the following years. |

|||

On 6 July 2019, Bagan was officially inscribed as a World Heritage Site by the UNESCO, 24 years after its first nomination, during the 43rd session of the World Heritage Committee.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/myanmar-bagan-unesco-world-heritage-status-11697654 |title=Myanmar's temple city Bagan awarded UNESCO World Heritage status |website=CNA |language=en |access-date=2019-07-07 |archive-date=2019-07-07 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190707062501/https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/myanmar-bagan-unesco-world-heritage-status-11697654 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Bagan became the second World Heritage Site in Myanmar, after the [[Pyu city-states|Ancient Cities of Pyu]]. As part of the criteria for the inscription of Bagan, the government had pledged to relocate existing hotels in the archaeological zone to a dedicated hotel zone by 2020.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.mmtimes.com/news/bagan-named-unesco-world-heritage-site.html |title=Bagan named UNESCO World Heritage Site |website=The Myanmar Times |date=7 July 2019 |language=en |access-date=2019-07-07 |archive-date=2021-07-29 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210729233417/https://www.mmtimes.com/news/bagan-named-unesco-world-heritage-site.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

On 24 August 2016, a [[August 2016 Myanmar earthquake|major earthquake]] hit central Burma and again did major damage in Bagan; this time almost 400 temples were destroyed. The Sulamani and Myauk Guni (North Guni) were severely damaged. The Bagan Archaeological Department has started a survey and reconstruction effort with the help of UNESCO experts. Visitors are prohibited from entering 33 damaged temples. |

|||

Bagan today is a main tourist destination in the country's nascent tourism industry.<ref name=te/> |

|||

==Geography== |

==Geography== |

||

The '''Bagan Archaeological Zone''', defined as the {{cvt|13|x|8|km}} area centred around Old Bagan, consisting of [[Nyaung U]] in the north and New Bagan in the south,<ref name="unesco-whs"/> lies in the vast expanse of plains in Upper Burma on the bend of the [[Irrawaddy river]]. It is located {{cvt|290|km|mi}} south-west of [[Mandalay]] and {{cvt|700|km|mi}} north of [[Yangon]]. |

|||

[[File:Bagan temples map.png|thumb|Map of the Bagan area showing the locations of the temples, hotels and transportation hubs]] |

|||

The '''Bagan Archaeological Zone''', defined as the 13 x 8 km area centred around Old Bagan, consisting of [[Nyaung U]] in the north and New Bagan in the south,<ref name="unesco-whs"/> lies in the vast expanse of plains in Upper Burma on the bend of the [[Irrawaddy river]]. It is located {{convert|290|km|mi}} south-west of [[Mandalay]] and {{convert|700|km|mi}} north of [[Yangon]]. Its coordinates are 21°10' North and 94°52' East. |

|||

===Climate=== |

===Climate=== |

||

Bagan lies in the middle of the |

Bagan lies in the middle of the [[Dry Zone (Myanmar)|Dry Zone]], the region roughly between [[Shwebo]] in the north and [[Pyay]] in the south. Unlike the coastal regions of the country, which receive annual monsoon rainfalls exceeding {{cvt|2500|mm}}, the dry zone gets little precipitation as it is sheltered from the rain by the [[Rakhine Yoma]] mountain range in the west. |

||

Available online climate sources report Bagan climate quite differently. |

Available online climate sources report Bagan climate quite differently. |

||

{{Weather box |

{{Weather box |

||

|location = Bagan |

|location = Bagan |

||

| Line 138: | Line 161: | ||

|Dec rain days = |

|Dec rain days = |

||

|source 1 = www.holidaycheck.com<ref name=weather> |

|source 1 = www.holidaycheck.com<ref name=weather> |

||

{{cite web |url=http://www.holidaycheck.com/climate-wetter_Bagan-ebene_oid-id_5822.html |title=Weather for Bagan |publisher=www.holidaycheck.com |access-date=2012-02-19 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://archive.today/20130125121407/http://www.holidaycheck.com/climate-wetter_Bagan-ebene_oid-id_5822.html |archive-date=2013-01-25}}</ref> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.holidaycheck.com/climate-wetter_Bagan-ebene_oid-id_5822.html |

|||

|title=Weather for Bagan |

|||

|publisher=www.holidaycheck.com |

|||

|accessdate=2012-02-19 |

|||

|deadurl=yes |

|||

|archiveurl=https://archive.is/20130125121407/http://www.holidaycheck.com/climate-wetter_Bagan-ebene_oid-id_5822.html |

|||

|archivedate=2013-01-25 |

|||

|df= |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

|date=February 2012}} |

|date=February 2012}} |

||

{{Weather box |

{{Weather box |

||

|location = Bagan |

|location = Bagan |

||

|single line = Y |

|single line = Y |

||

|metric first = Y |

|metric first = Y |

||

|Jan high C = |

|Jan high C = 28 |

||

|Feb high C = |

|Feb high C = 32 |

||

|Mar high C = |

|Mar high C = 36 |

||

|Apr high C = |

|Apr high C = 39 |

||

|May high C = |

|May high C = 38 |

||

|Jun high C = |

|Jun high C = 35 |

||

|Jul high C = |

|Jul high C = 33 |

||

|Aug high C = |

|Aug high C = 32 |

||

|Sep high C = |

|Sep high C = 32 |

||

|Oct high C = |

|Oct high C = 31 |

||

|Nov high C = |

|Nov high C = 29 |

||

|Dec high C = |

|Dec high C = 27 |

||

|year high C = |

|year high C = |

||

|Jan low C = |

|Jan low C = 16 |

||

|Feb low C = |

|Feb low C = 19 |

||

|Mar low C = |

|Mar low C = 24 |

||

|Apr low C = |

|Apr low C = 28 |

||

|May low C = |

|May low C = 29 |

||

|Jun low C = |

|Jun low C = 27 |

||

|Jul low C = |

|Jul low C = 26 |

||

|Aug low C = |

|Aug low C = 25 |

||

|Sep low C = |

|Sep low C = 25 |

||

|Oct low C = |

|Oct low C = 24 |

||

|Nov low C = |

|Nov low C = 20 |

||

|Dec low C = |

|Dec low C = 17 |

||

|year low C = |

|year low C = |

||

|rain colour = green |

|rain colour = green |

||

|Jan rain mm = |

|Jan rain mm = 5 |

||

|Feb rain mm = 0 |

|Feb rain mm = 0.6 |

||

|Mar rain mm = |

|Mar rain mm = 2.6 |

||

|Apr rain mm = |

|Apr rain mm = 16.4 |

||

|May rain mm = |

|May rain mm = 49.6 |

||

|Jun rain mm = |

|Jun rain mm = 69.8 |

||

|Jul rain mm = |

|Jul rain mm = 126.7 |

||

|Aug rain mm = |

|Aug rain mm = 182 |

||

|Sep rain mm = |

|Sep rain mm = 152.4 |

||

|Oct rain mm = |

|Oct rain mm = 103.6 |

||

|Nov rain mm = |

|Nov rain mm = 25.5 |

||

|Dec rain mm = |

|Dec rain mm = 5.7 |

||

|Jan rain days = |

|Jan rain days = 2 |

||

|Feb rain days = |

|Feb rain days = 1 |

||

|Mar rain days = |

|Mar rain days = 2 |

||

|Apr rain days = |

|Apr rain days = 9 |

||

|May rain days = |

|May rain days = 14 |

||

|Jun rain days = |

|Jun rain days = 21 |

||

|Jul rain days = |

|Jul rain days = 26 |

||

|Aug rain days = |

|Aug rain days = 28 |

||

|Sep rain days = |

|Sep rain days = 24 |

||

|Oct rain days = |

|Oct rain days = 20 |

||

|Nov rain days = |

|Nov rain days = 6 |

||

|Dec rain days = 2 |

|Dec rain days = 2 |

||

|source 1 = www.weatheronline.com<ref name=weather2>{{cite web |url=http://www.worldweatheronline.com/Bagan-weather-averages/Mandalay/MM.aspx |title=Weather for Bagan |publisher=www.worldweatheronline.com |access-date=2021-03-03 |archive-date=2021-07-29 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210729233422/https://www.worldweatheronline.com/bagan-weather-averages/mandalay/mm.aspx |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

|source 1 = www.weatheronline.com<ref name=weather2> |

|||

|date=March 2021}} |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.worldweatheronline.com/Bagan-weather-averages/Mandalay/MM.aspx |

|||

| title = Weather for Bagan |

|||

| publisher = http://www.worldweatheronline.com |

|||

| accessdate = 2014-04-13 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

|date=April 2014}} |

|||

==Cityscape== |

==Cityscape== |

||

{{Panorama |

{{Panorama |

||

|image |

|image = File:Mi Nyein Gone-Bagan-Myanmar-15-Panorama view-gje.jpg |

||

|fullwidth |

|fullwidth = 20 |

||

|fullheight = 1 |

|fullheight = 1 |

||

|caption |

|caption = {{center|Panorama of Bagan as seen from the Minyeingon Temple: The Thatbyinnyu on the left and the Dhammayangyi in the distance on the right}} |

||

|height |

|height = 250 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Panorama |

{{Panorama |

||

|image |

|image = File:P1130180 filtered Panorama s.jpg |

||

|fullwidth |

|fullwidth = 20 |

||

|fullheight = 1 |

|fullheight = 1 |

||

|caption |

|caption = {{center|Bagan Plains with the Dhammayangyi on the left}} |

||

|height |

|height = 250 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Panorama |

{{Panorama |

||

|image |

|image = File:Bagan panorama2.jpg |

||

|fullwidth |

|fullwidth = 20 |

||

|fullheight = 1 |

|fullheight = 1 |

||

|caption |

|caption = {{center|Bagan Plains with the Irrawaddy in the background}} |

||

|height |

|height = 250 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Panorama |

{{Panorama |

||

|image |

|image = File:The plains of Bagan (02).jpg |

||

|fullwidth |

|fullwidth = 20 |

||

|fullheight = 1 |

|fullheight = 1 |

||

|caption |

|caption = {{center|Bagan Plains, as seen from across the Irrawaddy river.}} |

||

|height |

|height = 250 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

{{POV|date=November 2021}} |

|||

===Architecture=== |

===Architecture=== |

||

Bagan stands out for not only the sheer number of religious edifices of Myanmar but also the magnificent architecture of the buildings, and their contribution to Burmese temple design. The artistry of the architecture of pagodas in Bagan proves the achievement of Myanmar craftsmen in handicrafts. The Bagan temple falls into one of two broad categories: the ''[[stupa]]''-style solid temple and the ''gu''-style ( |

Bagan stands out for not only the sheer number of religious edifices of Myanmar but also the magnificent architecture of the buildings, and their contribution to Burmese temple design. The artistry of the architecture of pagodas in Bagan proves the achievement of Myanmar craftsmen in handicrafts. The Bagan temple falls into one of two broad categories: the ''[[stupa]]''-style solid temple and the ''gu''-style (ဂူ) hollow temple. |

||

====Stupas==== |

====Stupas==== |

||

A ''stupa'', also called a pagoda or chedi, is a massive structure, typically with a relic chamber inside. The Bagan ''stupas'' or pagodas evolved from earlier Pyu designs, which in turn were based on the ''stupa'' designs of the [[Andhra region]], particularly [[Amaravathi village, Guntur district|Amaravati]] and [[Nagarjunakonda]] in present-day south-eastern India, and to a smaller extent to [[Ceylon]].<ref name="mat-2005-26-31">Aung-Thwin 2005: 26–31</ref> The Bagan-era stupas in turn were the prototypes for later Burmese stupas in terms of symbolism, form and design, building techniques and even materials.<ref name="mat-2005-233-235">Aung-Thwin 2005: 233–235</ref> |

|||

{{multiple image|right |

|||

{{multiple image |

|||

| header = Evolution of the Burmese stupa |

|||

| header = Evolution of the Burmese stupa |

|||

| image1 = 20160810 Bawbawgyi Pogoda Sri Ksetra Pyay Myanmar 9252.jpg |

|||

| image1 = 20160810 Bawbawgyi Pogoda Sri Ksetra Pyay Myanmar 9252.jpg |

|||

| width1 = 94 |

|||

| |

| width1 = 94 |

||

| alt1 = |

|||

| caption1 =[[Bawbawgyi Pagoda]] (7th century [[Sri Ksetra]]) |

|||

| caption1 = [[Bawbawgyi Pagoda]] (7th century [[Sri Ksetra]]) |

|||

| image2 = Bagan-Bu-Paya.JPG |

|||

| image2 = Bagan-Bu-Paya.JPG |

|||

| width2 = 82 |

|||

| |

| width2 = 82 |

||

| alt2 = |

|||

| caption2 = [[Bupaya Pagoda|Bupaya]] (pre-11th century) |

| caption2 = [[Bupaya Pagoda|Bupaya]] (pre-11th century) |

||

| image3 |

| image3 = Lawkananda-Dec-2000-01.JPG |

||

| width3 |

| width3 = 145 |

||

| alt3 |

| alt3 = |

||

| caption3 = The [[Lawkananda Pagoda|Lawkananda]] (pre-11th century) |

| caption3 = The [[Lawkananda Pagoda|Lawkananda]] (pre-11th century) |

||

| image4 |

| image4 = Shwezigon.JPG |

||

| width4 |

| width4 = 82 |

||

| alt4 |

| alt4 = |

||

| caption4 = The [[Shwezigon Pagoda|Shwezigon]] (11th century) |

| caption4 = The [[Shwezigon Pagoda|Shwezigon]] (11th century) |

||

| image5 |

| image5 = Dhamma-Yazaka.JPG |

||

| width5 |

| width5 = 145 |

||

| alt5 |

| alt5 = |

||

| caption5 = The [[Dhammayazika Pagoda|Dhammayazika]] (12th century) |

| caption5 = The [[Dhammayazika Pagoda|Dhammayazika]] (12th century) |

||

| image6 |

| image6 = Mingalazedi-Bagan-Myanmar-02-gje.jpg |

||

| width6 |

| width6 = 160 |

||

| alt6 |

| alt6 = |

||

| caption6 = The [[Mingalazedi Pagoda|Mingalazedi]] (13th century) |

| caption6 = The [[Mingalazedi Pagoda|Mingalazedi]] (13th century) |

||

| image7 |

| image7 = Unnamed Buddhist temple (113753).jpg |

||

| width7 |

| width7 = 107 |

||

| alt7 |

| alt7 = |

||

| caption7 = Ceremonial umbrellas at a Bagan temple |

| caption7 = Ceremonial umbrellas at a Bagan temple |

||

}} |

}} |

||

{{clear}} |

|||

A ''stupa'', also called a pagoda, is a massive structure, typically with a relic chamber inside. The Bagan ''stupas'' or pagodas evolved from earlier Pyu designs, which in turn were based on the ''stupa'' designs of the Andhra region, particularly [[Amaravathi village, Guntur district|Amaravati]] and [[Nagarjunakonda]] in present-day south-eastern India, and to a smaller extent to [[Ceylon]].<ref name="mat-2005-26-31">Aung-Thwin 2005: 26–31</ref> The Bagan-era stupas in turn were the prototypes for later Burmese stupas in terms of symbolism, form and design, building techniques and even materials.<ref name="mat-2005-233-235">Aung-Thwin 2005: 233–235</ref> |

|||

Originally, |

Originally, a Ceylonese ''stupa'' had a hemispheric body ({{langx|pi|anda}} "the egg"), on which a rectangular box surrounded by a stone [[balustrade]] (''harmika'') was set. Extending up from the top of the ''stupa'' was a shaft supporting several ceremonial umbrellas. The ''stupa'' [[Buddhist cosmology|Buddhist cosmos]]: its shape symbolizes [[Mount Meru]] while the umbrella mounted on the brickwork represents the world's axis.<ref name="hk-ab-118-120">Köllner, Bruns 1998: 118–120</ref> The brickwork pediment was often covered in stucco and decorated in relief. Pairs or series of ogres as guardian figures ('bilu') were a favourite theme in the Bagan period.<ref>{{cite book |author1=Falconer, J. |author2=Moore, E. |author3=Tettoni, L. I. |title=Burmese design and architecture |year=2000 |publisher=Periplus |location=Hong Kong |isbn=9625938826}}</ref> |

||

The original Indic design was gradually modified first by the [[Pyu people|Pyu]], and then by Burmans at Bagan where the ''stupa'' gradually developed a longer, cylindrical form. The earliest Bagan ''stupas'' such as the Bupaya (c. 9th century) were the direct descendants of the Pyu style at [[Sri Ksetra]]. By the 11th century, the ''stupa'' had developed into a more bell-shaped form in which the parasols morphed into a series of increasingly smaller rings placed on one top of the other, rising to a point. On top the rings, the new design replaced the ''harmika'' with a lotus bud. The lotus bud design then evolved into the "banana bud", which forms the extended apex of most Burmese pagodas. Three or four rectangular terraces served as the base for a pagoda, often with a gallery of terra-cotta tiles depicting Buddhist ''[[jataka]]'' stories. The [[Shwezigon Pagoda]] and the [[Shwesandaw Pagoda (Bagan)|Shwesandaw Pagoda]] are the earliest examples of this type.<ref name="hk-ab-118-120"/> Examples of the trend toward a more bell-shaped design gradually gained primacy as seen in the [[Dhammayazika Pagoda]] (late 12th century) and the [[Mingalazedi Pagoda]] (late 13th century).<ref name="mat-2005-210-213">Aung-Thwin 2005: 210–213</ref> |

The original Indic design was gradually modified first by the [[Pyu people|Pyu]], and then by Burmans at Bagan where the ''stupa'' gradually developed a longer, cylindrical form. The earliest Bagan ''stupas'' such as the Bupaya (c. 9th century) were the direct descendants of the Pyu style at [[Sri Ksetra]]. By the 11th century, the ''stupa'' had developed into a more bell-shaped form in which the parasols morphed into a series of increasingly smaller rings placed on one top of the other, rising to a point. On top the rings, the new design replaced the ''harmika'' with a lotus bud. The lotus bud design then evolved into the "banana bud", which forms the extended apex of most Burmese pagodas. Three or four rectangular terraces served as the base for a pagoda, often with a gallery of terra-cotta tiles depicting Buddhist ''[[jataka]]'' stories. The [[Shwezigon Pagoda]] and the [[Shwesandaw Pagoda (Bagan)|Shwesandaw Pagoda]] are the earliest examples of this type.<ref name="hk-ab-118-120"/> Examples of the trend toward a more bell-shaped design gradually gained primacy as seen in the [[Dhammayazika Pagoda]] (late 12th century) and the [[Mingalazedi Pagoda]] (late 13th century).<ref name="mat-2005-210-213">Aung-Thwin 2005: 210–213</ref> |

||

====Hollow temples==== |

====Hollow temples==== |

||

{{multiple image |

|||

{{double image|right|Gawdawpalin Temple Bagan Myanmar.jpg|131|Dhammayangyi Paya, Bagan, Myanmar.jpg|120|"One-face"-style [[Gawdawpalin Temple]] (left) and "four-face" [[Dhammayangyi Temple]]}} |

|||

| align = right |

|||

| image1 = Gawdawpalin Temple Bagan Myanmar.jpg |

|||

| width1 = 145 |

|||

| alt1 = |

|||

| caption1 = |

|||

| image2 = Bagan, Myanmar, Dhammayangyi Temple.jpg |

|||

| width2 = 120 |

|||

| alt2 = |

|||

| caption2 = |

|||

| footer = "One-face"-style [[Gawdawpalin Temple]] (left) and "four-face" [[Dhammayangyi Temple]] |

|||

}} |

|||

In contrast to the ''stupas'', the hollow ''gu''-style temple is a structure used for meditation, devotional worship of the Buddha and other Buddhist rituals. The ''gu'' temples come in two basic styles: "one-face" design and "four-face" design—essentially one main entrance and four main entrances. Other styles such as five-face and hybrids also exist. The one-face style grew out of 2nd century [[Beikthano]], and the four-face out of 7th century Sri Ksetra. The temples, whose main features were the pointed arches and the vaulted chamber, became larger and grander in the Bagan period.<ref name="mat-2005-224-225">Aung-Thwin 2005: 224–225</ref> |

In contrast to the ''stupas'', the hollow ''gu''-style temple is a structure used for meditation, devotional worship of the Buddha and other Buddhist rituals. The ''gu'' temples come in two basic styles: "one-face" design and "four-face" design—essentially one main entrance and four main entrances. Other styles such as five-face and hybrids also exist. The one-face style grew out of 2nd century [[Beikthano]], and the four-face out of 7th century Sri Ksetra. The temples, whose main features were the pointed arches and the vaulted chamber, became larger and grander in the Bagan period.<ref name="mat-2005-224-225">Aung-Thwin 2005: 224–225</ref> |

||

| Line 301: | Line 319: | ||

===Notable cultural sites=== |

===Notable cultural sites=== |

||

[[File:Ruins of Bagan, 1999.jpg|thumb|Bagan at dawn]] |

[[File:Ruins of Bagan, 1999.jpg|thumb|Bagan at dawn]] |

||

[[File: |

[[File:Old Bagan, Myanmar, Sunset over ancient 12th century pagodas in Bagan plains.jpg|thumb|Old Bagan at sunset]] |

||

{| class="wikitable sortable" border="1" |

{| class="wikitable sortable" border="1" |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Line 312: | Line 329: | ||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Ananda Temple]] |

| [[Ananda Temple]] |

||

| [[File:Ananda |

| [[File:Bagan, Myanmar, Ananda Temple.jpg|120px]] |

||

| 1105 |

| 1105 |

||

| King [[Kyansittha]] |

| King [[Kyansittha]] |

||

| One of the most famous temples in Bagan |

| One of the most famous temples in Bagan; {{cvt|51|m|0}} tall |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Bupaya Pagoda]] |

| [[Bupaya Pagoda]] |

||

| [[File:Pagan-Buphaya-pagoda-Nov-2004-00.JPG|120px]] |

| [[File:Pagan-Buphaya-pagoda-Nov-2004-00.JPG|120px]] |

||

| |

| {{circa}} 850 |

||

| King [[Pyusawhti]] |

| King [[Pyusawhti|Pyu Saw Hti]] |

||

| In [[Pyu people|Pyu]] style; original 9th century pagoda destroyed by the 1975 earthquake; completely rebuilt, now gilded |

| In [[Pyu people|Pyu]] style; original 9th century pagoda destroyed by the 1975 earthquake; completely rebuilt, now gilded |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Dhammayangyi Temple]] |

| [[Dhammayangyi Temple]] |

||

| [[File: |

| [[File:Bagan, Myanmar, Dhammayangyi Temple.jpg|120px]] |

||

| 1167–1170 |

| 1167–1170 |

||

| King [[Narathu]] |

| King [[Narathu]] |

||

| Line 337: | Line 354: | ||

| [[Gawdawpalin Temple]] |

| [[Gawdawpalin Temple]] |

||

| [[File:Gawdawpalin Temple Bagan Myanmar.jpg|120px]] |

| [[File:Gawdawpalin Temple Bagan Myanmar.jpg|120px]] |

||

| |

| {{circa}} 1211–1235 |

||

| King Sithu II and King [[Htilominlo]] |

| King Sithu II and King [[Htilominlo]] |

||

| |

| |

||

| Line 354: | Line 371: | ||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Htilominlo Temple]] |

| [[Htilominlo Temple]] |

||

| [[File:Htilominlo Temple Bagan Myanmar.jpg|120px]] |

| [[File:20160801 - Htilominlo Temple, Bagan, Myanmar - 6718.jpg|120px]] |

||

| 1218 |

| 1218 |

||

| King Htilominlo |

| King Htilominlo |

||

| {{cvt|46|m|0}}, 3-story temple |

|||

| Three stories and 46 meters tall |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Lawkananda Pagoda]] |

| [[Lawkananda Pagoda]] |

||

| [[File:Lawkananda-Bagan-Myanmar-01-gje.jpg|120px]] |

| [[File:Lawkananda-Bagan-Myanmar-01-gje.jpg|120px]] |

||

| |

| {{circa}} 1044–1077 |

||

| King [[Anawrahta]] |

| King [[Anawrahta]] |

||

| |

| |

||

| Line 367: | Line 384: | ||

| [[Mahabodhi Temple, Bagan|Mahabodhi Temple]] |

| [[Mahabodhi Temple, Bagan|Mahabodhi Temple]] |

||

| [[File:Mahabodhi Temple, Bagan.jpg|120px]] |

| [[File:Mahabodhi Temple, Bagan.jpg|120px]] |

||

| |

| {{circa}} 1218 |

||

| King Htilominlo |

| King Htilominlo |

||

| Smaller replica of the [[Mahabodhi Temple]] in [[Bodh Gaya]] |

| Smaller replica of the [[Mahabodhi Temple]] in [[Bodh Gaya]] |

||

| Line 397: | Line 414: | ||

| [[Nanpaya Temple]] |

| [[Nanpaya Temple]] |

||

| [[File:Nanpaya-Bagan-Myanmar-01-gje.jpg|120px]] |

| [[File:Nanpaya-Bagan-Myanmar-01-gje.jpg|120px]] |

||

| |

| {{circa}} 1160–1170 |

||

| |

| |

||

| Hindu temple in Mon style; believed to be either Manuha's old residence or built on the site |

| Hindu temple in Mon style; believed to be either Manuha's old residence or built on the site |

||

| Line 403: | Line 420: | ||

| [[Nathlaung Kyaung Temple]] |

| [[Nathlaung Kyaung Temple]] |

||

| [[File:Nat-Hlaung Kyaung Vishnu Statute.JPG|120px]] |

| [[File:Nat-Hlaung Kyaung Vishnu Statute.JPG|120px]] |

||

| |

| {{circa}} 1044–1077 |

||

| |

| |

||

| Hindu temple |

| Hindu temple |

||

| Line 409: | Line 426: | ||

| [[Payathonzu Temple]] |

| [[Payathonzu Temple]] |

||

| [[File:Bagan, Hpaya-thon-zu-Group.JPG|120px]] |

| [[File:Bagan, Hpaya-thon-zu-Group.JPG|120px]] |

||

| |

| {{circa}} 1200 |

||

| |

| |

||

| in [[Mahayana Buddhism|Mahayana]] and [[Tantric Buddhism|Tantric]]-styles |

| in [[Mahayana Buddhism|Mahayana]] and [[Tantric Buddhism|Tantric]]-styles |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Seinnyet Nyima |

| [[Seinnyet Nyima Pagoda]] and [[Seinnyet Ama Pagoda]] |

||

|[[File:Seinnyet temple.jpg|120px]] |

| [[File:Seinnyet temple.jpg|120px]] |

||

| |

| 11th century |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

| Line 427: | Line 444: | ||

| [[Shwesandaw Pagoda (Bagan)|Shwesandaw Pagoda]] |

| [[Shwesandaw Pagoda (Bagan)|Shwesandaw Pagoda]] |

||

| [[File:Shwesandaw Pagoda Bagan Myanmar.jpg|120px]] |

| [[File:Shwesandaw Pagoda Bagan Myanmar.jpg|120px]] |

||

| {{circa}} 1057 |

|||

| c. 1070 |

|||

| King Anawrahta |

| King Anawrahta |

||

| {{cvt|100|m|0}} tall without counting the ''[[hti]]'' spire; Tallest Pagoda in Bagan |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Shwezigon Pagoda]] |

| [[Shwezigon Pagoda]] |

||

| Line 445: | Line 462: | ||

| [[Tharabha Gate]] |

| [[Tharabha Gate]] |

||

| [[File:Tharaba Gate.JPG|120px]] |

| [[File:Tharaba Gate.JPG|120px]] |

||

| |

| {{circa}} 1020 |

||

| King [[Kunhsaw Kyaunghpyu]] and King [[Kyiso]] |

| King [[Kunhsaw Kyaunghpyu]] and King [[Kyiso]] |

||

| The only remaining part of the old walls; radiocarbon dated to |

| The only remaining part of the old walls; radiocarbon dated to {{circa}} 1020<ref name="mat-2005-38">Aung-Thwin 2005: 38</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Thatbyinnyu Temple]] |

| [[Thatbyinnyu Temple]] |

||

| [[File: |

| [[File:Bagan, Myanmar, Thatbyinnyu Temple.jpg|120px]] |

||

| |

| 1150/51 |

||

| Sithu I |

| Sithu I |

||

| |

| {{cvt|66|m|0}}; Tallest temple in Bagan |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Tuywindaung Pagoda]] |

| [[Tuywindaung Pagoda]] |

||

| Line 462: | Line 479: | ||

|- |

|- |

||

|} |

|} |

||

== The walled core of "Old Bagan" == |

|||

The 140-[[hectare]] core on the riverbank is surrounded by three walls.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 66 --> A fourth wall, on the western side, may have once existed before being washed away by the river at some point.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 66 --> The Irrawaddy has certainly eroded at least some parts of the city, since there are "buildings collapsing into the river both upstream and downstream from the walled core".<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 66 --><ref name="Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001">{{cite journal |author1=Hudson, Bob |author2=Nyein Lwin |author3=Win Maung |title=The Origins of Bagan: New Dates and Old Inhabitants |journal=[[Asian Perspectives]] |date=2001 |volume=40 |issue=1 |pages=48–74 |doi=10.1353/asi.2001.0009 |jstor=42928487 |hdl=10125/17144 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/42928487 |access-date=2 January 2024|hdl-access=free }}</ref>{{rp|66}} |

|||

The walled core called "Old Bagan" takes up only a tiny fraction of the 8,000-hectare area where monuments are found.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 66 --> It is also much smaller than the walled areas of major Pyu cities (the largest, Śrī Kṣetra or Thayekittaya, has a walled area of 1,400 hectares).<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 66 --> Altogether, this suggests that "'Old Bagan' represents an elite core, not an urban boundary".<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 66 --><ref name="Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001"/>{{rp|66}} |

|||

== Outlying sites == |

|||

=== Otein Taung === |

|||

An important outlying site is at Otein Taung, 2 km south of the Ananda temple in the walled city of Old Bagan.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 53 --> The name "Otein Taung" is a descriptive name meaning "pottery hill"; there is another Otein Taung on the north side of Beikthano.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 53 --> The site of Otein Taung at Bagan actually consists of two different mounds separated by 500 meters.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 53 --> Both are "covered with dense layers of fragmented pottery, and with scatters of potsherds visible around and between them".<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 53 --> Local farm fields for crops like maize come right up to the edges of the mounds, and goats and cattle commonly graze on them.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 53 --><ref name="Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001"/>{{rp|53}} |

|||

Besides the mounds, there are also about 40 small monuments at Otein Taung, mostly dated to the 13th century.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 53, 61 --> Several of these are clustered around a monastery on the south side of the western mound. There is also a group of monuments arranged in a straight line, which may represent a property boundary or road.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 61 --> Another cluster exists south of the eastern mound, and then there are also randomly scattered monuments in the area between the mounds.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 61 --> Finally, there is a large temple between the two mounds, which was probably built in the 12th century.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 61 --> This temple was restored in 1999.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 61 --><ref name="Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001"/>{{rp|53, 61}} |

|||

Otein Taung was excavated by a team led by Bob Hudson and Nyein Lwin in 1999 and 2000.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 53 --> Excavation revealed layers of [[potash]] with a fine texture, suggesting that most of the fuel was provided by bamboo and other grasses.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 54 --> Also found were small charcoal fragments, preserved burnt bamboo filaments, and some animal bones and pigs' teeth.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 54 --> Based on radiocarbon dating, Otein Taung dates from at least the 9th century, which is well before recorded history at Bagan.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 61, 70--><ref name="Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001"/>{{rp|53–4, 61, 70}} |

|||

The sprinkler pot, or ''[[kendi (pottery)|kendi]]'', is a very characteristic type of pottery from medieval Myanmar, and over 50 spouts and necks belonging to them were found by archaeologists at Otein Taung.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 58 --> These were all straight, in contrast to the bent spouts found at Beikthano.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 58 --> Also found at Otein Taung are earthenware tubes, about 60 cm long and 40 cm in diameter.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 59 --> Similar pipes have been found at Old Bagan, and they are thought to have been part of toilets.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 59 --><ref name="Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001"/>{{rp|58–9}} |

|||

It is not clear whether Otein Taung represents a large-scale pottery production site or "a huge, and for Bagan unique, residential midden".<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 55 --> Archaeologists did not find any "slumps characteristic of [https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/overfire#English overfiring] in a stoneware kiln, [or] any large brick or earth structures suggesting a pottery kiln",<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 55 --> but several "earthenware anvils" were found at the site, as well as a 10-cm-long clay tube that may have been used as a stamp for decorating pots.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 56 --> The anvils are common potters' tools in South and Southeast Asia: they are held inside a pot while the outside is beaten with a paddle.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 56 --><ref name="Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001"/>{{rp|55–6}} |

|||

If Otein Taung was used as a pottery production site, then it would have had good access to natural clay resources: the Bagan area has clayey subsoil that is "still mined today for brickmaking".<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 55-6 --> There are four tanks within 500 m of Otein Taung that may have originated as clay pits.<!-- Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001, p. 56 --><ref name="Hudson, Nyein Lwin, and Win Maung 2001"/>{{rp|55–6}} |

|||

===Museums=== |

===Museums=== |

||

[[File:Bagan Palace.JPG|thumb|Old palace site in Old Bagan. A new completely conjectural palace has been reconstructed since 2003.]] |

[[File:Bagan Palace.JPG|thumb|Old palace site in Old Bagan. A new completely conjectural palace has been reconstructed since 2003.]] |

||

* |

*The Bagan Archaeological Museum: The only museum in the Bagan Archaeological Zone. The three-story museum houses a number of rare Bagan period objects including the original [[Myazedi inscription]]s, the [[Rosetta stone]] of Burma. |

||

* |

*Anawrahta's Palace: It was rebuilt in 2003 based on the extant foundations at the old palace site.<ref name=moc>Ministry of Culture</ref> But the palace above the foundation is completely conjectural. |

||

== 3D Documentation with LiDAR == |

|||

==Transport== |

|||

The [[Zamani Project]] from the [[University of Cape Town]], South Africa, offered its services towards the spatial documentation of monuments in Bagan in response to the destruction of monuments by an [[August 2016 Myanmar earthquake|earthquake in August 2016]]. After reconnaissance visit to Bagan and a subsequent meeting at the UNESCO offices in Bangkok in February 2017, the Zamani Project documented 12 monuments in Bagan using [[LiDAR]], during three field campaigns between 2017 and 2018,<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://zamaniproject.org/site-myanmar-bagan-temples-pagodas.html |title=Site - Bagan |website=zamaniproject.org |access-date=2019-09-27 |archive-date=2019-09-25 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190925115516/https://zamaniproject.org/site-myanmar-bagan-temples-pagodas.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=https://lidarnews.com/articles/laserscanning-for-heritage-conservation-the-example-of-bagan/ |title=Laser Scanning for Heritage Conservation - Bagan, Myanmar - |date=2017-07-01 |website=lidarnews.com |language=en-US |access-date=2019-09-26 |archive-date=2019-09-26 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190926142321/https://lidarnews.com/articles/laserscanning-for-heritage-conservation-the-example-of-bagan/ |url-status=live }}</ref> including Kubyauk-gyi ([[Gubyaukgyi Temple (Myinkaba)|Gubyaukgyi]]) (298); Kyauk-ku-umin (154); Tha-peik-hmauk-gu-hpaya (744); Sula-mani-gu-hpaya ([[Sulamani Temple|Sulamani]]) (748) Monument 1053; Sein-nyet-ama (1085); Sein-nyet-nyima (1086); Naga-yon-hpaya (1192); Loka-ok-shaung (1467); Than-daw-kya (1592); Ananda Monastery; and the City Gate of old Bagan ([[Tharabha Gate]]). |

|||

[[File:Nyaung U Airport.JPG|thumb|left|[[Nyaung U Airport]] is the gateway to the Bagan region]] |

|||

==Transport== |

|||

Bagan is accessible by air, rail, bus, car and river boat. |

Bagan is accessible by air, rail, bus, car and river boat. |

||

===Air=== |

===Air=== |

||

Most international tourists fly to the city. The [[Nyaung U Airport]] is the gateway to the Bagan region. Several domestic airlines have regular flights to [[Yangon]], which take about 80 minutes to cover the 600 kilometres. Flights to [[Mandalay]] take approximately 30 minutes and to [[Heho]] about 40 minutes.<ref name="bagantravel"> |

Most international tourists fly to the city. The [[Nyaung U Airport]] is the gateway to the Bagan region. Several domestic airlines have regular flights to [[Yangon]], which take about 80 minutes to cover the 600 kilometres. Flights to [[Mandalay]] take approximately 30 minutes and to [[Heho]] about 40 minutes.<ref name="bagantravel">{{cite web |url=http://www.visit-bagan.com/getting-there.html |title=Getting to Bagan Myanmar |website=Visit Bagan |date=16 March 2019 |access-date=31 March 2015 |archive-date=10 November 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171110021301/http://www.visit-bagan.com/getting-there.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> The airport is located on the outskirts of [[Nyaung U]] and it takes about 20 minutes by taxi to reach Bagan. |

||

===Rail=== |

===Rail=== |

||

The city is on a spur from the |

The city is on a spur from the [[Yangon–Mandalay Railway]]. [[Myanmar Railways]] operates a daily overnight train service each way between [[Yangon]] and Bagan (Train Nos 61 & 62), which takes at least 18 hours. The trains have a sleeper car and also 1st Class and Ordinary Class seating.<ref name="trainmyanmar">{{cite web |url=http://www.seat61.com/Burma.htm#Yangon-Bagan |title=Train Travel in Myanmar |website=The man in seat 61... |access-date=2015-03-31 |archive-date=2009-01-30 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090130045616/http://seat61.com/Burma.htm#Yangon-Bagan |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

Between [[Mandalay]] and Bagan there are two daily services each way (Train Nos 117,118,119 & 120) that take at least 8 hours. The trains have 1st Class and Ordinary Class seating.<ref name=" |

Between [[Mandalay]] and Bagan there are two daily services each way (Train Nos 117,118,119 & 120) that take at least 8 hours. The trains have 1st Class and Ordinary Class seating.<ref name="trainmyanmar" /> |

||

===Buses and cars=== |

===Buses and cars=== |

||

Overnight buses and cars also operate to and from [[Yangon]] and [[Mandalay]] taking approximately 9 and 6 hours respectively.<ref name=" |

Overnight buses and cars also operate to and from [[Yangon]] and [[Mandalay]] taking approximately 9 and 6 hours respectively.<ref name="bagantravel" /> |

||

===Boat=== |

===Boat=== |

||

| Line 492: | Line 529: | ||

==Demographics== |

==Demographics== |

||

The population of Bagan in its heyday is estimated anywhere between 50,000<ref name="geh-78">Harvey 1925: 78</ref> |

The population of Bagan in its heyday is estimated to be anywhere between 50,000<ref name="geh-78">Harvey 1925: 78</ref> and 200,000 people.<ref name="hk-ab-115">Köllner, Bruns 1998: 115</ref> Until the advent of tourism industry in the 1990s, only a few villagers lived in Old Bagan. The rise of tourism has attracted a sizable population to the area. Because Old Bagan is now off limits to permanent dwellings, much of the population reside in either New Bagan, south of Old Bagan, or Nyaung-U, north of Old Bagan. The majority of native residents are [[Bamar people|Bamar]]. |

||

==Administration== |

==Administration== |

||

| Line 498: | Line 535: | ||

==Sister cities== |

==Sister cities== |

||

* |

*{{Flag icon|Laos}} [[Luang Prabang]], [[Laos]]<ref name=sis>Pan Eiswe Star and Soe Than Linn 2010</ref> |

||

* |

*{{Flag icon|Cambodia}} [[Siem Reap]], [[Cambodia]]<ref name=sis/> |

||

==Gallery== |

==Gallery== |

||

<gallery mode=packed> |

<gallery mode="packed"> |

||

File: |

File:Bagan, Myanmar, Bagan landscape at sunset, mystery and magic.jpg|Bagan Plains |

||

File: |

File:Old Bagan, Myanmar, Bagan plains at sunset, Ancient city.jpg|Bagan Plains |

||

File:Bagan as Seen from the Viewing Tower.jpg|As seen from the Nanmyint Viewing Tower |

File:Bagan as Seen from the Viewing Tower.jpg|As seen from the Nanmyint Viewing Tower |

||

File:Balloon over Bagan.jpg|Aerial views from a hot air balloon |

File:Balloon over Bagan.jpg|Aerial views from a hot air balloon |

||

File:Bagan, Myanmar, Ancient temples at sunset.jpg|Bagan temples at sunset |

|||

File:Dreams of Myanmar (8280448574).jpg|Bagan Plains at sunset |

File:Dreams of Myanmar (8280448574).jpg|Bagan Plains at sunset |

||

File:Bagan, Myanmar, Htilominlo Temple and other Buddhist stupas in Bagan plain.jpg|Htilominlo Temple and other temples |

|||

File:Ananda Temple.jpg|The [[Ananda Temple|Ananda]] |

|||

File:Bagan, Myanmar, Thatbyinnyu Temple.jpg|The [[Thatbyinnyu Temple]] |

|||

File:GawdawpalinD.jpg|The [[Gawdawpalin Temple|Gawdawpalin]] |

File:GawdawpalinD.jpg|The [[Gawdawpalin Temple|Gawdawpalin]] |

||

File: |

File:Bagan, Myanmar, Dhammayangyi Temple.jpg|The [[Dhammayangyi Temple|Dhammayangyi]] |

||

File:Shwezigon-Bagan-Myanmar-06-gje.jpg|The [[Shwezigon Pagoda|Shwezigon]] |

File:Shwezigon-Bagan-Myanmar-06-gje.jpg|The [[Shwezigon Pagoda|Shwezigon]] |

||

File:Bagan |

File:Bagan, Myanmar, Entrance door of Htilominlo Temple.jpg|Doorway to a temple |

||

File:Ananda Buddha, Bagan, Myanmar.jpg|One of the main four Buddha statutes inside the Ananda |

File:Ananda Buddha, Bagan, Myanmar.jpg|One of the main four Buddha statutes inside the Ananda |

||

File:Ananda-Bagan-Myanmar-25-gje.jpg|A hallway inside the Ananda |

File:Ananda-Bagan-Myanmar-25-gje.jpg|A hallway inside the Ananda |

||

File:Htilominlo-Bagan-Myanmar-23-Buddha-gje.jpg|Inside the [[Htilominlo Temple|Htilominlo]] |

File:Htilominlo-Bagan-Myanmar-23-Buddha-gje.jpg|Inside the [[Htilominlo Temple|Htilominlo]] |

||

File:Sulamani-Bagan-Myanmar-23-gje.jpg|Frescoes inside the [[Sulamani Temple|Sulamani]] |

|||

File:BAGAN INTERIOR DE LA PAGODA DE LOS FRESCOS.jpg|Frescoes inside a temple |

File:BAGAN INTERIOR DE LA PAGODA DE LOS FRESCOS.jpg|Frescoes inside a temple |

||

File:Dhammayangyi-Bagan-Myanmar-12-gje.jpg|Buddha statutes inside the Dhammayangyi |

File:Dhammayangyi-Bagan-Myanmar-12-gje.jpg|Buddha statutes inside the Dhammayangyi |

||

File:Manuha-Bagan-Myanmar-17-gje.jpg|Inside the [[Manuha Temple]] |

File:Manuha-Bagan-Myanmar-17-gje.jpg|Inside the [[Manuha Temple]] |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

== See also == |

|||

{{portal|Myanmar}} |

|||

*[[Buddhism in Myanmar]] |

|||

*[[Burmese pagoda]] |

|||

*[[Pagoda festival]] |

|||

*[[Index of Buddhism-related articles]] |

|||

*[[List of Pagodas in Bagan]] |

|||

==Notes== |

==Notes== |

||

{{ |

{{Reflist}} |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

*{{cite book |last=Aung-Thwin |first=Michael |title=Pagan: The Origins of Modern Burma |publisher=University of Hawai'i Press |year=1985 |location=Honolulu |isbn=0-8248-0960-2}} |

|||

* |

*{{cite book |last=Aung-Thwin |first=Michael |title=The mists of Rāmañña: The Legend that was Lower Burma |edition=illustrated |publisher=University of Hawai'i Press |year=2005 |location=Honolulu |isbn=978-0-8248-2886-8}} |

||

*{{cite web |author=Ministry of Culture, Union of Myanmar |title=Royal Palaces in Myanmar |url=http://culturemyanmar.org/pages/doa_royal_palace.html |publisher=Ministry of Culture |year=2009 |access-date=2012-02-19 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120803074057/http://culturemyanmar.org/pages/doa_royal_palace.html |archive-date=2012-08-03}} |

|||

* {{cite book | last=Aung-Thwin | first=Michael | title=The mists of Rāmañña: The Legend that was Lower Burma | edition=illustrated | publisher=University of Hawai'i Press | year=2005 | location=Honolulu | isbn=978-0-8248-2886-8}} |

|||

*{{cite book |last=Harvey |first=G. E. |title=History of Burma: From the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824 |publisher=Frank Cass & Co. Ltd |year=1925 |location=London}} |

|||

* {{cite web|author=Ministry of Culture, Union of Myanmar |title=Royal Palaces in Myanmar |url=http://culturemyanmar.org/pages/doa_royal_palace.html |publisher=Ministry of Culture |year=2009 |accessdate=2012-02-19 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120803074057/http://culturemyanmar.org/pages/doa_royal_palace.html |archivedate=2012-08-03 }} |

|||

* |

*{{cite book |last=Htin Aung |first=Maung |title=A History of Burma |url=https://archive.org/details/historyofburma00htin |url-access=registration |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=New York and London |year=1967}} |

||

* |

*{{cite book |last=Ishizawa |first=Yoshiaki |author2=Yasushi Kono |title=Study on Pagan: research report |year=1989 |publisher=Institute of Asian Cultures, Sophia University |pages=239}} |

||

* |

*{{cite book |last=Kala |first=U |title=Maha Yazawin |publisher=Ya-Pyei Publishing |location=Yangon |year=1724 |edition=2006, 4th printing |language=my |volume=1–3 |title-link=Maha Yazawin}} |

||

* |

*{{cite book |last=Köllner |first=Helmut |author2=Axel Bruns |title=Myanmar (Burma) |publisher=Hunter Publishing |edition=illustrated |year=1998 |pages=255 |isbn=978-3-88618-415-6}} |

||

* |

*{{cite book |last=Lieberman |author-link=Victor Lieberman |first=Victor B. |title=Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830, volume 1, Integration on the Mainland |year=2003 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-80496-7}} |

||

*{{cite journal |author=Pan Eiswe Star |author2=Soe Than Linn |title=Archaeologists to assist with Cambodia excavations |journal=The Myanmar Times |volume=26 |issue=509 |date=2010-02-10}} |

|||

* {{cite book | last= [[Victor Lieberman|Lieberman]] | first= Victor B. | title= Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830, volume 1, Integration on the Mainland | year=2003 | publisher=Cambridge University Press | isbn=978-0-521-80496-7}} |

|||

*{{cite book |author=Royal Historical Commission of Burma |title=Hmannan Yazawin |volume=1–3 |year=1832 |location=Yangon |language=my |edition=2003 |publisher=[[Ministry of Information, Myanmar]] |author-link=Royal Historical Commission of Burma |title-link=Hmannan Yazawin}} |

|||

* {{cite journal | author=Pan Eiswe Star |author2=Soe Than Linn | title=Archaeologists to assist with Cambodia excavations | work=The Myanmar Times | volume=26 | issue=509 | date=2010-02-10}} |

|||

*{{cite journal |last1=Rao |first1=V.K. |year=2013 |title=The Terracotta Plaques of Pagan: Indian Influence and Burmese Innovations |journal=Ancient Asia |volume=4 |page=7 |doi=10.5334/aa.12310 |doi-access=free}} |

|||

* {{cite book | author=[[Royal Historical Commission of Burma]] | title=[[Hmannan Yazawin]] | volume=1–3 | year=1832 | location=Yangon | language=Burmese | edition=2003 | publisher=[[Ministry of Information, Myanmar]]}} |

|||

*Rao, Vinay Kumar. "Buddhist Art of Pagan, 2 Vols". Published by Agam Kala Publications, New Delhi, 2011. {{ISBN|978-81-7320-116-5}}. |

|||

* {{cite journal | last1 = Rao | first1 = V.K. | year = 2013 | title = The Terracotta Plaques of Pagan: Indian Influence and Burmese Innovations | url = | journal = Ancient Asia | volume = 4 | issue = | page = 7 | doi = 10.5334/aa.12310 }} |

|||

*{{cite journal |last1=Rao |first1=Vinay Kumar |year=2013 |title=The Terracotta Plaques of Pagan: Indian Influence and Burmese Innovations |journal=Ancient Asia |volume=4 |page=7 |doi=10.5334/aa.12310 |doi-access=free}} |

|||

* Rao, Vinay Kumar. “Buddhist Art of Pagan, 2 Vols.” Published by Agam Kala Publications, New Delhi, 2011. {{ISBN|978-81-7320-116-5}}. |

|||

*{{cite book |last=Stadtner |first=Donald M. |title=Sacred Sites of Burma: Myth and Folklore in an Evolving Spiritual Realm |publisher=2011 |location=Bangkok |year=2011 |isbn=978-974-9863-60-2}} |

|||

* {{cite journal | last1 = Rao | first1 = Vinay Kumar | year = 2013 | title = The Terracotta Plaques of Pagan: Indian Influence and Burmese Innovations | url = | journal = Ancient Asia | volume = 4 | issue = | page = 7 | doi = 10.5334/aa.12310 }} |

|||

* |

*{{cite journal |author=Than Tun |title=History of Burma: A.D. 1300–1400 |journal=Journal of Burma Research Society |date=December 1959 |volume=XLII |number=II}} |

||

* |

*{{cite book |author=Than Tun |title=Studies in Burmese History |volume=1 |language=my |location=Yangon |publisher=Maha Dagon |year=1964}} |

||

*{{cite journal |last=Tourtellot |first=Jonathan B. |title=Dictators "Defacing" Famed Burma Temples |date=2004-09-03 |journal=The National Geographic Traveler |url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/09/0903_040903_travelwatch.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040904013757/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/09/0903_040903_travelwatch.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=September 4, 2004 |publisher=National Geographic}} |

|||

* {{cite book | author=Than Tun | title=Studies in Burmese History | volume=1 | language=Burmese | location=Yangon | publisher=Maha Dagon | year=1964}} |

|||

*{{cite book |author=UNESCO |title=Unesco Courier |volume=28 |year=1976 |publisher=[[UNESCO]] |location=Paris}} |

|||

* {{cite journal | last=Tourtellot | first=Jonathan B. | title=Dictators "Defacing" Famed Burma Temples | date=2004-09-03 | work=The National Geographic Traveler | url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/09/0903_040903_travelwatch.html | publisher=National Geographic}} |

|||

* |

*{{cite web |author=UNESCO |title=Bagan Archaeological Area and Monuments |url=https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/819/ |access-date=2012-02-18 |publisher=UNESCO}} |

||

* {{cite web | author=UNESCO | title=Bagan Archaeological Area and Monuments | url=http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/819/ | accessdate=2012-02-18 | publisher=UNESCO}} |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Wikivoyage|Bagan}} |

{{Wikivoyage|Bagan}} |

||

{{Commons category|Bagan}} |

{{Commons category|Bagan}} |

||

* |

*[http://www.dpsmap.com/bagan/index.shtml Bagan Map]. DPS Online Maps. |

||

* |

*[http://www.visit-bagan.com/ Bagan Travel Guide] |

||

* |

*[http://www.bagan.ws/ All about Bagan (english version)] |

||

* |

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20120308214102/http://www.jeyjoo.com/gallery/img-bagan-burma-608.htm Free travel images of Bagan] |

||

* |

*[http://www.seasite.niu.edu/burmese/cooler/80Scenes/80_scenes_of_buddhas_life.htm The Life of the Buddha in 80 Scenes, Ananda Temple] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131219013130/http://www.seasite.niu.edu/burmese/cooler/80Scenes/80_scenes_of_buddhas_life.htm |date=2013-12-19 }} Charles Duroiselle, ''Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report'', Delhi, 1913–14 |

||

* |

*[http://www.seasite.niu.edu/burmese/cooler/Chapter_3/Part1/pagan_period_1.htm The Art and Culture of Burma - the Pagan Period] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131202233841/http://www.seasite.niu.edu/burmese/cooler/Chapter_3/Part1/pagan_period_1.htm |date=2013-12-02 }} Dr. Richard M. Cooler, [[Northern Illinois University]] |

||

* |

*[http://www.orientalarchitecture.com/myanmar/bagan/index.php Asian Historical Architecture: Bagan] Prof. Robert D. Fiala, [[Concordia University, Nebraska]] |

||

* |

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20070311215404/http://www.timemap.net/~hudson/pagan.htm Buddhist Architecture at Bagan] Bob Hudson, [[University of Sydney]], Australia |

||

* |

*Photographs of temples and paintings of Bagan [http://www.indiamonuments.org/Myanmar/Myanmar%2001/Myanmar%2001.htm Part 1] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130701135310/http://www.indiamonuments.org/Myanmar/Myanmar%2001/Myanmar%2001.htm |date=2013-07-01 }} and [http://www.indiamonuments.org/Myanmar/Myanmar%2002/Myanmar%2002.htm Part 2] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130701140929/http://www.indiamonuments.org/Myanmar/Myanmar%2002/Myanmar%2002.htm |date=2013-07-01 }} |

||

* |

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20140714201516/http://www.movingpostcards.tv/bagan/ Bagan moving postcards] |

||

{{s-start}} |

{{s-start}} |

||

| Line 569: | Line 614: | ||

{{s-end}} |

{{s-end}} |

||

{{Coord|21|10|N|94|52|E|type:city|display=title}} |

|||

{{Mandalay Region}} |

{{Mandalay Region}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Bagan| ]] |

|||

[[Category:Township capitals of Myanmar]] |

[[Category:Township capitals of Myanmar]] |

||

[[Category:9th-century establishments in Asia]] |

[[Category:9th-century establishments in Asia]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Populated places established in the 9th century]] |

||

[[Category:Pagan kingdom]] |

|||

[[Category:Buddhist temples in Myanmar]] |

[[Category:Buddhist temples in Myanmar]] |

||

[[Category:Populated places in Mandalay Region]] |

[[Category:Populated places in Mandalay Region]] |

||

[[Category:Buddhist |

[[Category:Buddhist pilgrimage sites in Myanmar]] |

||

[[Category:Bagan]] |

|||

[[Category:Buddhist art]] |

[[Category:Buddhist art]] |

||

[[Category:Tourist attractions in Myanmar]] |

[[Category:Tourist attractions in Myanmar]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:World Heritage Sites in Myanmar]] |

||

Latest revision as of 07:35, 30 December 2024

Bagan

ပုဂံ Pagan | |

|---|---|

Temples and pagodas in Bagan | |

| Coordinates: 21°10′21″N 94°51′36″E / 21.17250°N 94.86000°E | |

| Country | Myanmar |

| Region | Mandalay Region |

| Founded | mid-to-late 9th century |

| Area | |

• Total | 104 km2 (40 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Ethnicities | Bamar people |

| • Religions | Theravada Buddhism |

| Time zone | UTC+6.30 (MST) |

| Website | |

| Official name | Bagan |

| Location | Mandalay Region, Myanmar |

| Criteria | Cultural: iii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 1588 |

| Inscription | 2019 (43rd Session) |

| Area | 5,005.49 ha (12,368.8 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 18,146.83 ha (44,841.8 acres) |