Copybook (calligraphy): Difference between revisions

m Edited initial sentence to remove 'chinese' calligraphy specific. Either the article title should be changed to 'Eastern Calligraphy', or the article should be rewritten to include examples from both Eastern and Western calligraphy. Very little in the way of sources for the other information on this page. Needs critical review. |

No edit summary |

||

| (6 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

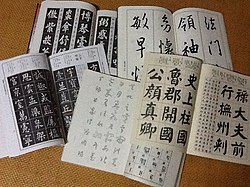

[[File:Zitie.jpg|thumb|250px|Copybooks of various styles of calligraphy]] |

[[File:Zitie.jpg|thumb|250px|Copybooks of various styles of calligraphy]] |

||

A '''copybook''' is a book containing examples of calligraphic script, meant to be copied while practicing [[calligraphy]]. |

A '''copybook''' ({{zh|t=|s=|p=zìtiè|c=字帖}}) is a book containing examples of calligraphic script, meant to be copied while practicing [[calligraphy]]. |

||

== |

== Origin of the copybook == |

||

In ancient times, famous [[calligraphy]] was carved in stone. Later, people made [[stone rubbing|rubbings of the stone]] on paper so that they could copy and learn the famous [[calligraphy]]. |

In ancient times, famous [[calligraphy]] was carved in stone. Later, people made [[stone rubbing|rubbings of the stone]] on paper so that they could copy and learn the famous [[calligraphy]]. |

||

Emperor of the [[Liang dynasty]] [[Xiao Yan]] made a rubbing of one thousand characters from the famous calligrapher [[Wang Xizhi]], and made sentences and paragraphs for the one thousand characters, which became known as the ''[[Thousand Character Classic]]''. Later the ''Thousand Character Classic'' became a systematic copybook.<ref>{{cite book|author=全唐文|title=徐氏法書記|pages=卷二百六十八|url=http://gj.zdic.net/archive.php?aid=16613}}</ref> |

|||

== Classification == |

== Classification == |

||

Copybooks can be divided according to the style of calligraphy and the kind of pen used. |

Copybooks can be divided according to the style of calligraphy and the kind of pen used. |

||

The styles of calligraphy that are used in copybooks include the [[regular script]] (楷書 |

The styles of calligraphy that are used in copybooks include the [[regular script]] ({{zh|t=楷書|s=楷书|p=|c=|labels=no}}), the [[cursive script (East Asia)|cursive script]] ({{zh|t=草書|s=草书|p=|c=|labels=no}}), the [[running script]] ({{zh|t=行書|s=行书|p=|c=|labels=no}}), the [[clerical script]] ({{zh|t=隸書|s=隶书|p=|c=|labels=no}}), and the [[seal script]] ({{zh|t=篆書|s=篆书|p=|c=|labels=no}}). |

||

Most calligraphy is for brushes, but there is also hard calligraphy, using [[ballpoint pen]]s, [[pencil]]s, or [[fountain pen]]s. |

Most calligraphy is for brushes, but there is also hard calligraphy, using [[ballpoint pen]]s, [[pencil]]s, or [[fountain pen]]s. |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

== Other == |

== Other == |

||

Since [[Yin |

Since the [[Yin dynasty]], it became popular to engrave words on stone to make them spread further and longer, but not calligraphy. Since the Tang dynasty, people began to save the beauty of calligraphy on the stone. So rubbing calligraphy was popular in that time. |

||

Before the development of new technology, [[calligraphy]] can only be learned by using stone rubbings. However, there had to be some mistakes. The new technology, Jingying Technology, actually helps learners a lot because the rubbing is much more like the original [[calligraphy]].<ref>{{cite book|author=王壯為|title=書法研究|year=1967|publisher=臺灣商務印書館|location=臺北市|isbn=9570506180|pages=30}}</ref> |

Before the development of new technology, [[calligraphy]] can only be learned by using stone rubbings. However, there had to be some mistakes. The new technology, Jingying Technology, actually helps learners a lot because the rubbing is much more like the original [[calligraphy]].<ref>{{cite book|author=王壯為|title=書法研究|year=1967|publisher=臺灣商務印書館|location=臺北市|isbn=9570506180|pages=30}}</ref> |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Linguistics textbooks]] |

||

[[Category:Chinese calligraphy]] |

[[Category:Chinese calligraphy]] |

||

Latest revision as of 19:33, 5 July 2024

A copybook (Chinese: 字帖; pinyin: zìtiè) is a book containing examples of calligraphic script, meant to be copied while practicing calligraphy.

Origin of the copybook

[edit]In ancient times, famous calligraphy was carved in stone. Later, people made rubbings of the stone on paper so that they could copy and learn the famous calligraphy.

Emperor of the Liang dynasty Xiao Yan made a rubbing of one thousand characters from the famous calligrapher Wang Xizhi, and made sentences and paragraphs for the one thousand characters, which became known as the Thousand Character Classic. Later the Thousand Character Classic became a systematic copybook.[1]

Classification

[edit]Copybooks can be divided according to the style of calligraphy and the kind of pen used.

The styles of calligraphy that are used in copybooks include the regular script (楷书; 楷書), the cursive script (草书; 草書), the running script (行书; 行書), the clerical script (隶书; 隸書), and the seal script (篆书; 篆書).

Most calligraphy is for brushes, but there is also hard calligraphy, using ballpoint pens, pencils, or fountain pens.

Modern role

[edit]Today children in China who enter school would have a copybook for learning characters. Because they just learn writing for a short time, it is hard for children to write characters in their own style. Copybooks can help children practice different font of handwriting and build their own style. If people want to learn calligraphy, besides the Four Treasures of the Study, they also need to prepare copybooks which the type of font is what they want to learn. Because the choice of copybooks would decide the style people write in. There are also copybooks that are online with the option to enter your own characters and create your own copybook.[2]

Steps

[edit]- Read: When first see a character, read the fond, the structure, the order of strokes, analyze the relationship between the strokes and figure out the feature of the character.

- Trace: Learners can just write on the book or use transparent paper cover the characters and copy it, which is also known as shadow copy writing.

- Copy: Put the copybook aside, and try best to write the characters exactly what they looks on another paper.

- Remember: Remember the character in the mind and write on the paper without looking at the copybook.

- Create: After grasping the writing on the copybook, learners can create their own style.

Other

[edit]Since the Yin dynasty, it became popular to engrave words on stone to make them spread further and longer, but not calligraphy. Since the Tang dynasty, people began to save the beauty of calligraphy on the stone. So rubbing calligraphy was popular in that time.

Before the development of new technology, calligraphy can only be learned by using stone rubbings. However, there had to be some mistakes. The new technology, Jingying Technology, actually helps learners a lot because the rubbing is much more like the original calligraphy.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ 全唐文. 徐氏法書記. pp. 卷二百六十八.

- ^ "Create Your Own Chinese Character Practise Writing Sheets". ChineseConverter.com. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ 王壯為 (1967). 書法研究. 臺北市: 臺灣商務印書館. p. 30. ISBN 9570506180.