Andrew Jackson: Difference between revisions

Historian7 (talk | contribs) the changes look fine. if you don't like something in them, change that. don't revert the entire thing. |

→top: trim |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|President of the United States from 1829 to 1837}} |

|||

{{Other people}} |

|||

{{about|the seventh president of the United States}} |

|||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

|||

{{redirect|President Jackson|the attack transport|USS President Jackson{{!}}USS ''President Jackson''|the class of attack transports|President Jackson-class attack transport{{!}}''President Jackson''-class attack transport}} |

|||

{{pp-move}} |

|||

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

||

{{featured article}} |

{{featured article}} |

||

{{Use |

{{Use American English|date=January 2022}} |

||

{{Use mdy dates|date=September 2024}} |

|||

{{short description|7th President of the United States}} |

|||

{{Infobox officeholder |

{{Infobox officeholder |

||

|name = Andrew Jackson |

| name = Andrew Jackson |

||

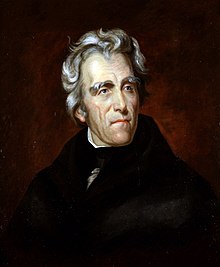

|image = Andrew jackson head.jpg |

| image = Andrew jackson head (cropped).jpg |

||

|caption |

| caption = Portrait {{circa|1835}} |

||

| alt = A portrait of Andrew Jackson, serious in posture and expression, with a grey-and-white haired widow's peak, wearing a red-collared black cape. |

|||

|alt = White-haired man with black coat |

|||

|order = 7th |

| order = 7th |

||

|office = President of the United States |

| office = President of the United States |

||

| vicepresident = {{plainlist| |

|||

|vicepresident = [[John C. Calhoun]] (1829–1832) <br> ''None'' (1832–1833)<br> Martin Van Buren (1833–1837) |

|||

* {{longitem|[[John C. Calhoun]]<br />(1829–1832)}} |

|||

|term_start = March 4, 1829 |

|||

* None (1832–1833){{efn|Vice President Calhoun resigned from office. As this was prior to the adoption of the [[Twenty-fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution|Twenty-fifth Amendment]] in 1967, a vacancy in the office of vice president was not filled until the next ensuing election and inauguration.}} |

|||

|term_end = March 4, 1837 |

|||

* {{longitem|Martin Van Buren<br />(1833–1837)}} |

|||

|predecessor = [[John Quincy Adams]] |

|||

}} |

|||

|successor = [[Martin Van Buren]] |

|||

| |

| term_start = March 4, 1829 |

||

| |

| term_end = March 4, 1837 |

||

| predecessor = [[John Quincy Adams]] |

|||

|term_start1 = March 4, 1823 |

|||

| |

| successor = [[Martin Van Buren]] |

||

| jr/sr1 = United States Senator |

|||

|predecessor1 = [[John Williams (Tennessee)|John Williams]] |

|||

| |

| state1 = [[Tennessee]] |

||

| |

| term_start1 = March 4, 1823 |

||

| |

| term_end1 = October 14, 1825 |

||

| predecessor1 = [[John Williams (Tennessee politician)|John Williams]] |

|||

|predecessor2 = [[William Cocke]] |

|||

| |

| successor1 = [[Hugh Lawson White]] |

||

| term_start2 = September 26, 1797 |

|||

|office3 = [[List of Governors of Florida|Military Governor of Florida]] |

|||

| term_end2 = April 1, 1798 |

|||

|appointer3 = [[James Monroe]] |

|||

| predecessor2 = [[William Cocke]] |

|||

|term_start3 = March 10, 1821 |

|||

| successor2 = [[Daniel Smith (surveyor)|Daniel Smith]] |

|||

|term_end3 = December 31, 1821 |

|||

| office3 = [[List of governors of Florida|Federal Military Commissioner of Florida]] |

|||

|predecessor3 = [[José María Coppinger]] (Spanish East Florida) |

|||

| |

| appointer3 = [[James Monroe]] |

||

| |

| term_start3 = March 10, 1821 |

||

| term_end3 = December 31, 1821 |

|||

|district4 = {{ushr|TN|AL|at-large}} |

|||

| predecessor3 = {{plainlist| |

|||

|term_start4 = December 4, 1796 |

|||

* [[José María Coppinger]] {{awrap|(Spanish East Florida)}} |

|||

|term_end4 = September 26, 1797 |

|||

* [[José María Callava]] {{awrap|(Spanish West Florida)}} |

|||

|predecessor4 = ''Constituency established'' |

|||

}} |

|||

|successor4 = [[William C. C. Claiborne]] |

|||

| successor3 = [[William Pope Duval]] {{awrap|(as Territorial Governor)}} |

|||

|birth_date = {{birth date|1767|3|15}} |

|||

| office4 = [[List of justices of the Tennessee Supreme Court|Justice of the Tennessee Superior Court]] |

|||

|birth_place = [[Waxhaws|Waxhaw Settlement]] between the Provinces of [[Province of North Carolina|North Carolina]] and [[Province of South Carolina|South Carolina]], [[British America]] |

|||

| appointer4 = [[John Sevier]] |

|||

|death_date = {{death date and age|1845|6|8|1767|3|15}} |

|||

| term_start4 = June 1798 |

|||

|death_place = [[Nashville, Tennessee]], U.S. |

|||

| term_end4 = June 1804 |

|||

|resting_place = [[The Hermitage (Nashville, Tennessee)|The Hermitage]] |

|||

| predecessor4 = [[Howell Tatum]] |

|||

|nationality = American |

|||

| |

| successor4 = [[John Overton (judge)|John Overton]] |

||

| state5 = Tennessee |

|||

* [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic]] (after 1828) |

|||

| district5 = {{ushr|TN|AL|at-large}} |

|||

| term_start5 = December 4, 1796 |

|||

| term_end5 = September 26, 1797 |

|||

| predecessor5 = [[James White (North Carolina politician)|James White]] (Delegate from the [[Southwest Territory]]) |

|||

| successor5 = [[William C. C. Claiborne]] |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth date|1767|3|15}} |

|||

| birth_place = [[Waxhaws|Waxhaw Settlement]] between [[Province of North Carolina|North Carolina]] and [[Province of South Carolina|South Carolina]], British America |

|||

| death_date = {{death date and age|1845|6|8|1767|3|15}} |

|||

| death_place = [[Nashville, Tennessee]], U.S. |

|||

| resting_place = [[The Hermitage (Nashville, Tennessee)|The Hermitage]] |

|||

| party = [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic]] (1828–1845) |

|||

| otherparty = {{plainlist| |

|||

* [[Democratic-Republican Party|Democratic-Republican]] (before 1825) |

|||

* [[Jacksonian democracy|Jacksonian]] (1825–1828) |

* [[Jacksonian democracy|Jacksonian]] (1825–1828) |

||

}} |

|||

* [[Democratic-Republican Party|Democratic-Republican]] (Before 1825)}} |

|||

| spouse = {{marriage|[[Rachel Jackson|Rachel Donelson]]|January 18, 1794|December 22, 1828|end=died}} |

|||

|parents = {{plainlist| |

|||

| children = 2, including [[Lyncoya Jackson|Lyncoya]] |

|||

* Andrew Jackson |

|||

| occupation = {{hlist|Politician|lawyer|general}} |

|||

* Elizabeth Hutchinson}} |

|||

| awards = {{plainlist| |

|||

|spouse = {{marriage|[[Rachel Jackson|Rachel Donelson]]|January 18, 1794|December 22, 1828|reason=d}} |

|||

* [[Congressional Gold Medal]] |

|||

|children = 3 adopted sons |

|||

* [[Thanks of Congress]] |

|||

|signature = Andrew Jackson Signature-.svg |

|||

}} |

|||

|signature_alt = Cursive signature in ink |

|||

| signature = Andrew Jackson Signature-.svg |

|||

|allegiance = {{flagu|United States|1818}} |

|||

| signature_alt = Cursive signature in ink |

|||

|branch = {{army|United States}} |

|||

| |

| allegiance = United States |

||

| branch = [[United States Army]] |

|||

| rank = {{plainlist| |

|||

* [[File:Army-USA-OF-07.svg|35px]] [[Major General (United States)|Major General]] ([[United States Volunteers]]) 1812 |

|||

* |

* [[Major general (United States)|Major general]] (U.S. Army) |

||

* Major general ([[United States Volunteers|U.S. Volunteers]]) |

|||

|unit = |

|||

* Major general ([[Tennessee State Guard|Tennessee militia]]) |

|||

|battles = {{plainlist| |

|||

}} |

|||

| unit = [[List of South Carolina militia units in the American Revolution|South Carolina Militia]] (1780–81)<br>[[Tennessee State Guard|Tennessee Militia]] (1792–1821)<br>[[United States Army]] (1814-1821) |

|||

| military_blank1 = Wars |

|||

| battles = {{collapsible list|title = {{nobold|See list}}| |

|||

{{tree list}} |

|||

* [[American Revolutionary War]] |

* [[American Revolutionary War]] |

||

** [[Battle of Hanging Rock]] |

** [[Battle of Hanging Rock]] |

||

| Line 69: | Line 89: | ||

** [[Battle of Talladega]] |

** [[Battle of Talladega]] |

||

** [[Battles of Emuckfaw and Enotachopo Creek]] |

** [[Battles of Emuckfaw and Enotachopo Creek]] |

||

** [[ |

** [[Battle of Horseshoe Bend]] |

||

* [[War of 1812]] |

* [[War of 1812]] |

||

** [[Battle of Pensacola (1814)|Battle of Pensacola]] |

** [[Battle of Pensacola (1814)|Battle of Pensacola]] |

||

** [[Battle of New Orleans]] |

** [[Battle of New Orleans]] |

||

* [[First Seminole War]] |

* [[Seminole Wars#First Seminole War|First Seminole War]] |

||

** [[San Marcos de Apalache Historic State Park|Capture of St. Marks]] |

|||

* Conquest of Florida |

|||

** [[Fort Barrancas#First battles under U.S. control|Siege of Fort Barrancas]] |

|||

** [[Battle of Negro Fort]] |

|||

{{tree list/end}} |

|||

** [[Fort Barrancas#First battles under U.S. control|Siege of Fort Barrancas]]}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|mawards = {{plainlist| |

|||

* [[Congressional Gold Medal]] |

|||

* [[Thanks of Congress]]}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Andrew Jackson''' (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh [[president of the United States]], serving from 1829 to 1837. Before [[Presidency of Andrew Jackson|his presidency]], he gained fame as a general in the [[United States Army|U.S. Army]] and served in both houses of the [[United States Congress|U.S. Congress]]. Sometimes praised as an advocate for working Americans and for [[Nullification crisis|preserving the union of states]], Jackson is also criticized for his racist policies, particularly regarding [[Native Americans in the United States|Native Americans]]. |

|||

Jackson was born in the colonial [[Carolinas]] before the [[American Revolutionary War]]. He became a [[American frontier|frontier]] lawyer and married [[Rachel Jackson|Rachel Donelson Robards]]. He briefly served in the [[United States House of Representatives|U.S. House of Representatives]] and the [[United States Senate|U.S. Senate]], representing [[Tennessee]]. After resigning, he served as a justice on the [[Tennessee Supreme Court#History|Tennessee Superior Court]] from 1798 until 1804. Jackson purchased a property later known as [[The Hermitage (Nashville, Tennessee)|the Hermitage]], becoming a wealthy [[Planter class|planter]] who owned hundreds of [[African Americans|African American]] [[Slavery in the United States|slaves]] during his lifetime. In 1801, he was appointed colonel of the Tennessee militia and was elected its commander. He led troops during the [[Creek War]] of 1813–1814, winning the [[Battle of Horseshoe Bend]] and negotiating the [[Treaty of Fort Jackson]] that required the indigenous [[Muscogee|Creek]] population to surrender vast tracts of present-day Alabama and Georgia. In the concurrent [[War of 1812|war against the British]], Jackson's victory at the [[Battle of New Orleans]] in 1815 made him a national hero. He later commanded U.S. forces in the [[Seminole Wars#First Seminole War|First Seminole War]], which led to the [[Adams–Onís Treaty|annexation]] of Florida from Spain. Jackson briefly served as Florida's first territorial governor before returning to the Senate. He ran for president in [[1824 United States presidential election|1824]]. He won a [[Plurality (voting)|plurality]] of the popular and electoral vote, but no candidate won the electoral majority. With the help of [[Henry Clay]], the House of Representatives elected [[John Quincy Adams]] as president. Jackson's supporters alleged that there was a "[[corrupt bargain]]" between Adams and Clay and began creating a new political coalition that became the [[History of the United States Democratic Party|Democratic Party]] in the 1830s. |

|||

'''Andrew Jackson''' (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American soldier and statesman who served as the [[List of Presidents of the United States|seventh President of the United States]] from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, Jackson gained fame as a general in the [[United States Army]] and served in both houses of [[United States Congress|Congress]]. As president, Jackson sought to advance the rights of the "common man"{{sfn|Brands|2005|p=473}} against a "corrupt aristocracy"{{sfn|Meacham|2008|p=219}} and to preserve the Union. |

|||

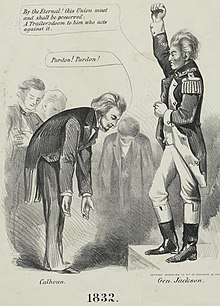

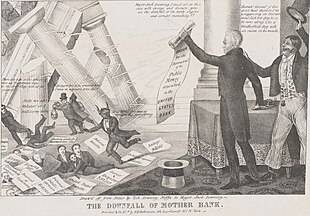

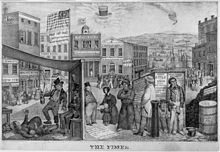

Jackson ran again [[1828 United States presidential election|in 1828]], defeating Adams in a landslide despite issues such as his slave trading and his 'irregular' marriage. In 1830, he signed the [[Indian Removal Act]]. This act, which has been described as [[ethnic cleansing]], [[Indian removal|displaced]] tens of thousands of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands east of the Mississippi and resulted in thousands of deaths. Jackson faced a challenge to the integrity of the federal union when South Carolina threatened to nullify a high [[Tariff of Abominations|protective tariff]] set by the federal government. He [[Force Bill|threatened]] the use of military force to enforce the tariff, but the crisis was defused when it was [[Tariff of 1833|amended]]. In 1832, he vetoed a bill by Congress to reauthorize the [[Second Bank of the United States]], arguing that it was a corrupt institution. After a lengthy [[Bank War|struggle]], the Bank was dismantled. In 1835, Jackson became the only president to pay off the [[National debt of the United States|national debt]]. |

|||

Born in the colonial [[Waxhaws|Carolinas]] to a [[Scotch-Irish Americans|Scotch-Irish]] family in the decade before the [[American Revolutionary War]], Jackson became a [[American frontier|frontier]] lawyer and married [[Rachel Jackson|Rachel Donelson Robards]]. He served briefly in the [[United States House of Representatives|U.S. House of Representatives]] and the [[United States Senate|U.S. Senate]] representing [[Tennessee]]. After resigning, he served as a [[List of Justices of the Tennessee Supreme Court|justice]] on the [[Tennessee Supreme Court]] from 1798 until 1804. Jackson purchased a property later known as the [[The Hermitage (Nashville, Tennessee)|Hermitage]], and became a wealthy, slaveowning planter. In 1801, he was appointed colonel of the Tennessee militia and was elected its commander the following year. He led troops during the [[Creek War]] of 1813–1814, winning the [[Battle of Horseshoe Bend (1814)|Battle of Horseshoe Bend]]. The subsequent [[Treaty of Fort Jackson]] required the [[Muscogee|Creek]] surrender of vast lands in present-day [[Alabama]] and [[Georgia (U.S. state)|Georgia]]. In the concurrent [[War of 1812|war against the British]], Jackson's victory in 1815 at the [[Battle of New Orleans]] made him a national hero. Jackson then led U.S. forces in the [[First Seminole War]], which led to the [[Adams–Onís Treaty|annexation]] of [[Florida]] from Spain. Jackson briefly served as Florida's first territorial governor before returning to the Senate. He ran for president in [[United States presidential election, 1824|1824]], winning a plurality of the popular and electoral vote. As no candidate won an electoral majority, the House of Representatives elected [[John Quincy Adams]] in a [[contingent election]]. In reaction to the alleged "[[corrupt bargain]]" between Adams and [[Henry Clay]] and the ambitious agenda of President Adams, Jackson's supporters founded the [[History of the United States Democratic Party|Democratic Party]]. |

|||

After leaving office, Jackson supported the presidencies of [[Martin Van Buren]] and [[James K. Polk]], as well as the [[Texas annexation|annexation of Texas]]. Jackson's legacy remains controversial, and opinions on his legacy are frequently polarized. Supporters characterize him as a defender of democracy and the [[Constitution of the United States|Constitution]], while critics point to his reputation as a [[demagogue]] who ignored the law when it suited him. [[Historical rankings of presidents of the United States|Scholarly rankings of presidents]] historically rated Jackson's presidency as above average. Since the late 20th century, his reputation declined, and in the 21st century his placement in rankings of presidents fell. |

|||

Jackson ran again in [[United States presidential election, 1828|1828]], defeating Adams in a landslide. Jackson faced the threat of secession by [[South Carolina]] over what opponents called the "[[Tariff of Abominations]]." The [[Nullification Crisis|crisis]] was defused when the tariff was [[Tariff of 1833|amended]], and Jackson [[Force Bill|threatened]] the use of military force if South Carolina attempted to secede. In Congress, Henry Clay led the effort to reauthorize the [[Second Bank of the United States]]. Jackson, regarding the Bank as a corrupt institution, vetoed the renewal of its charter. After a lengthy [[Bank War|struggle]], Jackson and his allies thoroughly dismantled the Bank. In 1835, Jackson became the only president to completely pay off the national debt, fulfilling a longtime goal. His presidency marked the beginning of the ascendancy of the party "[[spoils system]]" in American politics. In 1830, Jackson signed the [[Indian Removal Act]], which forcibly [[Trail of Tears|relocated]] most members of the [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]] tribes in the South to [[Indian Territory]]. The relocation process dispossessed the Indians and resulted in widespread death and disease. Jackson opposed the [[abolitionism|abolitionist]] movement, which grew stronger in his second term. In foreign affairs, Jackson's administration concluded a "most favored nation" treaty with Great Britain, settled claims of damages against France from the [[Napoleonic Wars]], and recognized the [[Republic of Texas]]. In January 1835, he survived the first assassination attempt on a sitting president. |

|||

In his retirement, Jackson remained active in Democratic Party politics, supporting the presidencies of [[Martin Van Buren]] and [[James K. Polk]]. Though fearful of its effects on the [[Slavery in the United States|slavery]] debate, Jackson advocated the [[Texas annexation|annexation of Texas]], which was accomplished shortly before his death. Jackson was widely revered in the United States as an advocate for democracy and the common man, but his reputation has declined since the [[civil rights movement]], largely due to his role in Indian removal and support for slavery. Surveys of historians and scholars have [[Historical rankings of presidents of the United States|ranked]] Jackson favorably among United States presidents. |

|||

==Early life and education== |

==Early life and education== |

||

Andrew Jackson was born on March 15, 1767, in the [[Waxhaws]] region of the Carolinas. His parents were [[Scotch-Irish Americans|Scots-Irish]] colonists Andrew and Elizabeth Hutchinson |

Andrew Jackson was born on March 15, 1767, in the [[Waxhaws]] region of the [[Carolinas]]. His parents were [[Scotch-Irish Americans|Scots-Irish]] colonists Andrew Jackson and Elizabeth Hutchinson, [[Presbyterianism|Presbyterians]] who had emigrated from [[Ulster]], Ireland, in 1765.{{sfn|Brands|2005|pp=11–15}} Jackson's father was born in [[Carrickfergus]], [[County Antrim]], around 1738,{{sfn|Gullan|2004|pp=xii; 308}} and his ancestors had crossed into Northern Ireland from Scotland after the [[Battle of the Boyne]] in 1690.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=2}} Jackson had two older brothers who came with his parents from Ireland, Hugh (born 1763) and Robert (born 1764).{{sfn|Nowlan|2012|p=257}}{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=2}} Elizabeth had a strong hatred of the British that she passed on to her sons.{{sfn|Meacham|2008|p=11}} |

||

Jackson's exact birthplace is unclear. Jackson's father died at the age of 29 in February 1767, three weeks before his son Andrew was born.{{sfn|Nowlan|2012|p=257}} Afterwards, Elizabeth and her three sons moved in with her sister and brother-in-law, Jane and James Crawford.{{sfn|Brands|2005|p=16}} Jackson later stated that he was born on the Crawford plantation,{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=4–5}} which is in [[Lancaster County, South Carolina]], but second-hand evidence suggests that he might have been born at another uncle's home in North Carolina.{{sfn|Brands|2005|p=16}} |

|||

When they immigrated to North America in 1765, Jackson's parents probably landed in [[Philadelphia]]. Most likely they traveled overland through the [[Appalachian Mountains]] to the Scots-Irish community in the Waxhaws, straddling the border between [[North Carolina|North]] and [[South Carolina]].{{sfn|Booraem|2001|p=9}} They brought two children from Ireland, Hugh (born 1763) and Robert (born 1764). Jackson's father died in a logging accident while clearing land{{sfn|Nowlan|2012|p=257}} in February 1767 at the age of 29, three weeks before his son Andrew was born. Jackson, his mother, and his brothers lived with Jackson's aunt and uncle in the Waxhaws region, and Jackson received schooling from two nearby priests.{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|pp=14–16}} |

|||

When Jackson was young, Elizabeth thought he might become a minister and paid to have him schooled by a local clergyman.{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|p=16}} He learned to read, write, and work with numbers, and was exposed to Greek and Latin,{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=6}} but he was too strong-willed and hot-tempered for the ministry.{{sfn|Brands|2005|p=16}} |

|||

Jackson's exact birthplace is unclear because of a lack of knowledge of his mother's actions immediately following her husband's funeral.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=5}} The area was so remote that the border between North and South Carolina had not been officially surveyed.<ref name="Old">{{cite web |last=Collings |first=Jeffrey |date=March 7, 2011 |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2011/03/06/AR2011030603406.html?wprss=rss_print/asection |title=Old fight lingers over Old Hickory's roots |publisher=''The Washington Post'' |access-date=June 29, 2017 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170127030733/http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2011/03/06/AR2011030603406.html?wprss=rss_print%2Fasection |archivedate=January 27, 2017 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> In 1824 Jackson wrote a letter saying that he was born on the plantation of his uncle James Crawford in [[Lancaster County, South Carolina]].{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=5}} Jackson may have claimed to be a South Carolinian because the state was considering nullification of the [[Tariff of 1824]], which he opposed. In the mid-1850s, second-hand evidence indicated that he might have been born at a different uncle's home in North Carolina.<ref name="Old"/>{{sfn|Parton|1860a|pp=54–57}} As a young boy, Jackson was easily offended and was considered something of a bully. He was, however, said to have taken a group of younger and weaker boys under his wing and been very kind to them.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=9}} |

|||

==Revolutionary War |

==Revolutionary War== |

||

[[File: |

[[File:The Brave Boy of the Waxhalls2.jpg|thumb|''The Brave Boy of the Waxhaws'', an 1876 [[Currier and Ives]] lithograph depicting a young Andrew Jackson defending himself from a [[British Army during the American Revolutionary War|British]] officer during the American Revolutionary War|alt=Sketch of an officer preparing to strike a boy with a sword. The boy holds out his arm in self-defense.]] |

||

During the [[American Revolutionary War|Revolutionary War]], Jackson's eldest brother, Hugh, died from heat exhaustion after the [[Battle of Stono Ferry]] on June 20, 1779.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=15}} Anti-British sentiment intensified following the brutal [[Battle of Waxhaws|Waxhaws Massacre]] on May 29, 1780. Jackson's mother encouraged him and his elder brother Robert to attend the local militia drills.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=15–17}} Soon, they began to help the militia as couriers.<ref name="Andrew Jackson">{{cite web |url = http://www.biography.com/people/andrew-jackson-9350991 |title = Andrew Jackson |website = Biography.com |access-date = April 23, 2017 |deadurl = no |archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20170627054356/https://www.biography.com/people/andrew-jackson-9350991 |archivedate = June 27, 2017 |df = mdy-all }}</ref> They served under Colonel [[William Richardson Davie]] at the [[Battle of Hanging Rock]] on August 6.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=15–17}} Andrew and Robert were captured by the British in 1781<ref name="Andrew Jackson"/> while staying at the home of the Crawford family. When Andrew refused to clean the boots of a British officer, the officer slashed at the youth with a sword, leaving him with scars on his left hand and head, as well as an intense hatred for the British. Robert also refused to do as commanded and was struck with the sword.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=21}} The two brothers were held as prisoners, contracted [[smallpox]], and nearly starved to death in captivity.{{sfn|Kendall|1843|pp=52–53}} |

|||

Jackson and his older brothers, Hugh and Robert, served on the [[Patriot (American Revolution)|Patriot]] side against British forces during the [[American Revolutionary War]]. Hugh served under Colonel [[William Richardson Davie]], dying from [[heat exhaustion]] after the [[Battle of Stono Ferry]] in June 1779.{{sfn|Booraem|2001|p=47}} After anti-British sentiment intensified in the Southern Colonies following the [[Battle of Waxhaws]] in May 1780, Elizabeth encouraged Andrew and Robert to participate in militia drills.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=15}} They served as couriers,{{sfn|Brands|2005|p=24}} and were present at the [[Battle of Hanging Rock]] in August 1780.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=17}} |

|||

Later that year, their mother Elizabeth secured the brothers' release. She then began to walk both boys back to their home in the Waxhaws, a distance of some 40 miles (64 km). Both were in very poor health. Robert, who was far worse, rode on the only horse that they had, while Andrew walked behind them. In the final two hours of the journey, a torrential downpour began which worsened the effects of the smallpox. Within two days of arriving back home, Robert was dead and Andrew in mortal danger.{{sfn|Kendall|1843|pp=58–59}}{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=23}} After nursing Andrew back to health, Elizabeth volunteered to nurse American [[prisoner of war|prisoners of war]] on board two British ships in the [[Charleston, South Carolina|Charleston]] harbor, where there had been an outbreak of [[cholera]]. In November, she died from the disease and was buried in an unmarked grave. Andrew became an orphan at age 14. He blamed the British personally for the loss of his brothers and mother.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=24–25}} |

|||

Andrew and Robert were captured in April 1781 when the British occupied the home of a Crawford relative. A British officer demanded to have his boots polished. Andrew refused, and the officer slashed him with a sword, leaving him with scars on his left hand and head. Robert also refused and was struck a blow on the head.{{sfnm|Meacham|2008|1p=12|Remini|1977|2p=21}} The brothers were taken to a [[prisoner-of-war camp]] in [[Camden, South Carolina]], where they became malnourished and contracted smallpox.{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|p=15}} In late spring, the brothers were released to their mother in a [[prisoner exchange]].{{sfn|Booraem|2001|p= 104}} Robert died two days after arriving home, but Elizabeth was able to nurse Andrew back to health.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=23–24}} Once he recovered, Elizabeth volunteered to nurse American [[Prisoner of war|prisoners of war]] housed in British [[prison ship]]s in the harbor of [[Charleston, South Carolina]].{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|p=17}} She contracted [[cholera]] and died soon afterwards.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=24}} The war made Jackson an orphan at age 14{{sfn|Brands|2005|pp=30–31}} and increased his hatred for the values he associated with Britain, in particular [[aristocracy]] and political privilege.{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|p=9}} |

|||

==Early career== |

==Early career== |

||

===Legal career and marriage=== |

===Legal career and marriage=== |

||

[[File:Rachel Donelson Jackson by Ralph E. W. Earl1823.jpg|thumb|Portrait of Jackson's wife Rachel, 1823 by [[Ralph Eleaser Whiteside Earl]] now housed at [[The Hermitage (Nashville, Tennessee)|The Hermitage]] in [[Nashville]]|alt=Woman in black with white bonnet and lace collar looking forward]] |

|||

After the Revolutionary War, Jackson received a sporadic education in a local Waxhaw school.{{sfn|Paletta|Worth|1988}} On bad terms with much of his extended family, he boarded with several different people.<ref name="NC State Library"/> In 1781, he worked for a time as a saddle-maker, and eventually taught school. He apparently prospered in neither profession.{{sfn|Meacham|2008|p=15}} In 1784, he left the Waxhaws region for [[Salisbury, North Carolina]], where he [[reading law|studied law]] under attorney Spruce Macay.{{sfn|Snelling|1831|p=8}} With the help of various lawyers, he was able to learn enough to [[Admission to practice law|qualify for the bar]]. In September 1787, Jackson was admitted to the North Carolina bar.<ref name="NC State Library">{{cite web |url=http://www.ncpedia.org/biography/jackson-andrew |title=Andrew Jackson |last=Case |first=Steven |date=2009 |publisher=State Library of North Carolina |access-date=July 20, 2017 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170618060525/http://www.ncpedia.org/biography/jackson-andrew |archivedate=June 18, 2017 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> Shortly thereafter, a friend helped Jackson get appointed to a vacant prosecutor position in the [[Washington District, North Carolina|Western District]] of North Carolina, which would later become the state of Tennessee. During his travel west, Jackson bought his first slave and in 1788, having been offended by fellow lawyer [[Waightstill Avery]], fought his first duel. The duel ended with both men firing into the air, having made a secret agreement to do so before the engagement.{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|pp=18–19}} |

|||

After the American Revolutionary War, Jackson worked as a saddler,{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=27}} briefly returned to school, and taught reading and writing to children.{{sfn|Booraem|2001|pp= 133, 136}} In 1784, he left the Waxhaws region for [[Salisbury, North Carolina]], where he [[reading law|studied law]] under attorney Spruce Macay.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=29}} He completed his training under [[John Stokes (North Carolina judge)|John Stokes]],{{sfn|Brands|2005|p=37}} and was admitted to the [[Bar examination in the United States|North Carolina bar]] in September 1787.<ref name="NC State Library">{{cite web |url=http://www.ncpedia.org/biography/jackson-andrew |title=Andrew Jackson |last=Case |first=Steven |date=2009 |publisher=State Library of North Carolina |access-date=July 20, 2017 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170618060525/http://www.ncpedia.org/biography/jackson-andrew |archive-date=June 18, 2017}}</ref> Shortly thereafter, his friend [[John McNairy]] helped him get appointed as a [[prosecuting attorney]] in the [[Washington District, North Carolina|Western District]] of North Carolina,{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=34}} which would later become the state of [[Tennessee]]. While traveling to assume his new position, Jackson stopped in [[Jonesborough, Tennessee|Jonesborough]]. While there, he bought his first slave, a woman who was around his age.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=37}} He also fought his first [[duel]], accusing another lawyer, [[Waightstill Avery]], of impugning his character. The duel ended with both men firing in the air.{{sfn|Booraem|2001|pp=190–191}} |

|||

Jackson moved to the small frontier town of [[Nashville, Tennessee|Nashville]] in 1788, where he lived as a boarder with Rachel Stockly Donelson, the widow of [[John Donelson]]. Here Jackson became acquainted with their daughter, [[Rachel Jackson|Rachel Donelson Robards]]. At the time, the younger Rachel was in an unhappy marriage with Captain Lewis Robards; he was subject to fits of jealous rage.{{sfn|Kennedy|Ullman|2003|pp=99–101}} The two were separated in 1790. According to Jackson, he married Rachel after hearing that Robards had obtained a divorce. Her divorce had not been made final, making Rachel's marriage to Jackson bigamous and therefore invalid. After the divorce was officially completed, Rachel and Jackson remarried in 1794.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=17–25}} To complicate matters further, evidence shows that Rachel had been living with Jackson and referred to herself as Mrs. Jackson before the petition for divorce was ever made.{{sfn|Meacham|2008|pp=22–23}} It was not uncommon on the frontier for relationships to be formed and dissolved unofficially, as long as they were recognized by the community.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=62}} |

|||

Jackson began his new career in the frontier town of Nashville in 1788 and quickly moved up in [[social status]].{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|p=18}} He became a protégé of [[William Blount]], one of the most powerful men in the territory.{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|p=19}} Jackson was appointed attorney general of the Mero District in 1791 and [[judge-advocate]] for the militia the following year.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=53}} He also got involved in land speculation,{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=87}} eventually forming a partnership with fellow lawyer [[John Overton (judge)|John Overton]].{{sfn|Clifton|1952|p=24}} Their partnership mainly dealt with claims made under a [[Confederation period#Western settlement|"land grab" act of 1783]] that opened [[Cherokee]] and [[Chickasaw]] territory to North Carolina's white residents.{{sfn|Durham|1990|pp=218–219}} Jackson also became a [[Andrew Jackson and the slave trade in the United States|slave trader]],{{sfn|Cheathem|2011|p=327}} transporting enslaved people for the [[Slave trade in the United States| interregional slave market]] between Nashville and the [[Natchez District]] of [[Spanish West Florida]] via the [[Mississippi River]] and the [[Natchez Trace]].{{sfn|Remini|1991|p=[https://www.proquest.com/openview/1a72861ea0a0473316e0d956124c4e31/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2029886 35]}} |

|||

===Land speculation and early public career=== |

|||

In 1794, Jackson formed a partnership with fellow lawyer [[John Overton (judge)|John Overton]], dealing in claims for land reserved by treaty for the [[Cherokee]] and [[Chickasaw]].{{sfn|Durham|1990|pp=218–219}} Like many of their contemporaries, they dealt in such claims although the land was in Indian country. Most of the transactions involved grants made under the 'land grab' act of 1783 that briefly opened Indian lands west of the Appalachians within North Carolina to claim by that state's residents. He was one of the three original investors who founded [[Memphis, Tennessee]], in 1819.<ref name="Jackson Purchase">{{cite web |last=Semmer |first=Blythe |url=http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entry.php?rec=698 |title=Jackson Purchase, Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture |publisher=Tennessee Historical Society |access-date=April 12, 2017 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160807120650/http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entry.php?rec=698 |archivedate=August 7, 2016 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> |

|||

While boarding at the home of Rachel Stockly Donelson, the widow of [[John Donelson]], Jackson became acquainted with their daughter, Rachel Donelson Robards. The younger Rachel was in an unhappy marriage with Captain [[Lewis Robards]], and the two were separated by 1789.{{sfn|Owsley|1977|pp=481–482}} After the separation, Jackson and Rachel became romantically involved,{{sfn|Brands|2005|p=63}} living together as husband and wife.{{sfn|Meacham|2008|pp=22–23}} Robards petitioned for divorce, which was granted in 1793 on the basis of Rachel's infidelity.{{sfnm|Howe|2007|1p=277|Remini|1977|2p=62}} The couple legally married in January 1794.{{sfn|Brands|2005|p=65}} In 1796, they acquired their first plantation, [[Hunter's Hill (Tennessee)|Hunter's Hill]],{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=68}} on {{convert|640|acres|ha|sigfig=2|abbr=on}} of land near Nashville.{{sfn|Brands|2005|p=73}} |

|||

After moving to Nashville, Jackson became a protege of [[William Blount]], a friend of the Donelsons and one of the most powerful men in the territory. Jackson became attorney general in 1791, and he won election as a delegate to the Tennessee [[constitutional convention (political meeting)|constitutional convention]] in 1796.{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|pp=18–19}} When Tennessee achieved statehood that year, he was elected its only [[United States House of Representatives|U.S. Representative]]. He was a member of the [[Democratic-Republican Party]], the dominant party in Tennessee.{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|p=19}} Jackson soon became associated with the more radical, pro-French and anti-British wing. He strongly opposed the [[Jay Treaty]] and criticized [[George Washington]] for allegedly removing Republicans from public office. Jackson joined several other Republican congressmen in voting against a resolution of thanks for Washington, a vote that would later haunt him when he sought the presidency.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=92–94}} In 1797, the state legislature elected him as [[United States Senate|U.S. Senator]]. Jackson seldom participated in debate and found the job dissatisfying. He pronounced himself "disgusted with the administration" of President [[John Adams]] and resigned the following year without explanation.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=110–112}} Upon returning home, with strong support from western Tennessee, he was elected to serve as a judge of the [[Tennessee Supreme Court]]<ref name="US Congress Bio">{{cite web|url=http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=j000005|title=Andrew Jackson|publisher=Biographical Directory of the U.S. Congress|accessdate=April 13, 2017|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20131218110615/http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=J000005|archivedate=December 18, 2013|df=mdy-all}}</ref> at an annual salary of $600.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=113}} Jackson's service as a judge is generally viewed as a success and earned him a reputation for honesty and good decision making.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=114}} Jackson resigned the judgeship in 1804. His official reason for resigning was ill health. He had been suffering financially from poor land ventures, and so it is also possible that he wanted to return full-time to his business interests.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=131}} |

|||

===Early public career=== |

|||

After arriving in Tennessee, Jackson won the appointment of judge advocate of the Tennessee militia.{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|pp=21–22}} In 1802, while serving on the Tennessee Supreme Court, he declared his candidacy for major general, or commander, of the Tennessee [[Militia (United States)|militia]], a position voted on by the officers. At that time, most free men were members of the militia. The organizations, intended to be called up in case of conflict with Europeans or Indians, resembled large social clubs. Jackson saw it as a way to advance his stature.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=15–16; 119}} With strong support from western Tennessee, he tied with [[John Sevier]] with seventeen votes. Sevier was a popular Revolutionary War veteran and former governor, the recognized leader of politics in eastern Tennessee. On February 5, Governor [[Archibald Roane]] broke the tie in Jackson's favor.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=119}} Jackson had also presented Roane with evidence of land fraud against Sevier. Subsequently, in 1803, when Sevier announced his intention to regain the governorship, Roane released the evidence. Sevier insulted Jackson in public, and the two nearly fought a duel over the matter. Despite the charges leveled against Sevier, he defeated Roane, and continued to serve as governor until 1809.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=119–124}} |

|||

[[File:Tennesee circa 1810.jpg|thumb|Tennessee {{circa}} 1810. The eastern counties shaded in blue, the [[Mero District]] in green, and Native American lands in red. The [[Natchez Trace]] from its northern terminus to Chickasaw Crossing where it leaves the state is shaded in gray.]] |

|||

Jackson became a member of the [[Democratic-Republican Party]], the dominant party in Tennessee.{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|p=19}} He was elected as a delegate to the Tennessee [[Constituent assembly|constitutional convention]] in 1796.{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|pp=18–19}} When Tennessee achieved statehood that year, he was elected to be its [[United States House of Representatives|U.S. representative]]. In Congress, Jackson argued against the [[Jay Treaty]], criticized [[George Washington]] for allegedly removing Democratic-Republicans from public office, and joined several other Democratic-Republican congressmen in voting against a resolution of thanks for Washington.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=92–94}} He advocated for the right of Tennesseans to militarily oppose Native American interests.{{sfn|Brands|2005|pp=79–81}} The state legislature elected him to be a [[United States Senate|U.S. senator]] in 1797, but he resigned after serving only six months.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=112}} |

|||

==Planting career and controversy== |

|||

[[File:AndrewJackson-RewardNotice-EscapedSlave-1804.png|thumb|alt=refer to caption|Notice of reward offered by Jackson for return of an enslaved man{{sfn|Cumfer|2007|p=140}}]] |

|||

In addition to his legal and political career, Jackson prospered as [[Planter (American South)|planter]], [[slavery in the United States|slave owner]], and merchant. He built a home and the first general store in [[Gallatin, Tennessee]], in 1803. The next year, he acquired the [[The Hermitage (Nashville, Tennessee)|Hermitage]], a {{convert|640|acre|0|abbr=on|adj=on}} plantation in [[Davidson County, Tennessee|Davidson County]], near [[Nashville, Tennessee|Nashville]]. He later added {{convert|360|acre|0|abbr=on}} to the plantation, which eventually totaled {{convert|1050|acres|0|abbr=on}}. The primary crop was [[cotton]], grown by slaves—Jackson began with nine, owned as many as 44 by 1820, and later up to 150, placing him among the planter elite. Jackson also co-owned with his son Andrew Jackson Jr. the Halcyon plantation in [[Coahoma County, Mississippi]], which housed 51 slaves at the time of his death.{{sfn|Cheathem|2011|pp=326–338}} Throughout his lifetime Jackson may have owned as many as 300 slaves.<ref>Remini (2000), p. 51, cites 1820 census; mentions later figures up to 150 without noting a source.</ref><ref name="Hermitage_Slavery_2011">{{cite web |title=Andrew Jackson's Enslaved Laborers |url=http://www.thehermitage.com/mansion-grounds/farm/slavery |publisher=The Hermitage |accessdate=April 13, 2017 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20140912055314/http://www.thehermitage.com/mansion-grounds/farm/slavery |archivedate=September 12, 2014 |df=mdy-all}}</ref> |

|||

In the spring of 1798, Governor [[John Sevier]] appointed Jackson to be a judge of the [[Tennessee Supreme Court|Tennessee Superior Court]].{{sfn|Ely|1981|pp=144–145}} |

|||

Men, women, and child slaves were owned by Jackson on three sections of the Hermitage plantation. Slaves lived in extended family units of between five and ten persons and were quartered in {{convert|400|sqft|m2}} cabins made either of brick or logs. The size and quality of the Hermitage slave quarters exceeded the standards of his times. To help slaves acquire food, Jackson supplied them with guns, knives, and fishing equipment. At times he paid his slaves with monies and coins to trade in local markets. The Hermitage plantation was a profit-making enterprise. Jackson permitted slaves to be whipped to increase productivity or if he believed his slaves' offenses were severe enough.<ref name=Hermitage_Slavery_2011/> At various times he posted advertisements for fugitive slaves who had escaped from his plantation. In one advertisement placed in the Tennessee Gazette in October 1804, Jackson offered “ten dollars extra, for every hundred lashes any person will give him, to the amount of three hundred.”<ref>Brown, DeNeen L. [https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2017/04/11/hunting-down-runaway-slaves-the-cruel-ads-of-andrew-jackson-and-the-master-class/ "Hunting down runaway slaves: The cruel ads of Andrew Jackson and ‘the master class’"], ''[[The Washington Post]]'', 1 May 2017. Retrieved on 22 March 2018.</ref> |

|||

In 1802, he also became major general, or commander, of the [[Tennessee State Guard|Tennessee militia]], a position that was determined by a vote of the militia's officers. The vote was tied between Jackson and Sevier, a popular Revolutionary War veteran and former governor, but the governor, [[Archibald Roane]], broke the tie in Jackson's favor. Jackson later accused Sevier of fraud and bribery.{{sfn|Brands|2005|pp=104–105}} Sevier responded by impugning Rachel's honor, resulting in a shootout on a public street.{{sfn|Meacham|2008|p=25}} Soon afterwards, they met to duel, but parted without having fired at each other.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=123}} |

|||

===Planting career and slavery=== |

|||

The controversy surrounding his marriage to Rachel remained a sore point for Jackson, who deeply resented attacks on his wife's honor. By May 1806, [[Charles Dickinson (historical figure)|Charles Dickinson]], who, like Jackson, raced horses, had published an attack on Jackson in the local newspaper, and it resulted in a written challenge from Jackson to a [[duel]]. Since Dickinson was considered an expert shot, Jackson determined it would be best to let Dickinson turn and fire first, hoping that his aim might be spoiled in his quickness; Jackson would wait and take careful aim at Dickinson. Dickinson did fire first, hitting Jackson in the chest. The bullet that struck Jackson was so close to his heart that it could not be removed. Under the rules of dueling, Dickinson had to remain still as Jackson took aim and shot and killed him. Jackson's behavior in the duel outraged men in Tennessee, who called it a brutal, cold-blooded killing and saddled Jackson with a reputation as a violent, vengeful man. He became a social outcast.{{sfn|Brands|2005|pp=139–143}} |

|||

{{main|Andrew Jackson and slavery}} |

|||

{{further|Andrew Jackson and the slave trade in the United States}} |

|||

[[File:Aaron and Hannah Jackson (1865).jpg|thumb|Aaron and [[Hannah Jackson]], two slaves owned by Jackson, photographed by [[T. M. Schleier|Theodore Schleier]] in 1865, now housed at the Hermitage in Nashville]] |

|||

Jackson resigned his judgeship in 1804.{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|p=21}} He had almost gone bankrupt when the land and mercantile speculations he had made on the basis of [[promissory notes]] fell apart in the wake of an [[Panic of 1796–1797|earlier financial panic]].{{sfnm|Howe|2007|1p=375|Sellers|1954|2pp=76–77}} He had to sell Hunter's Hill, as well as {{convert|25,000|acres|ha|sigfig=2|abbr=on}} of land he bought for speculation and bought a smaller {{convert|420|acre|0|sigfig=2|abbr=on|adj=on}} plantation near Nashville that he would call the Hermitage.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=131–132}} He focused on recovering from his losses by becoming a successful [[Planter class|planter]] and [[merchant]].{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=131–132}} The Hermitage grew to {{convert|1000|acres|ha|sigfig=2|abbr=on}},{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=379}} making it one of the largest cotton-growing plantations in the state.{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|p=21}} |

|||

After the Sevier affair and the duel, Jackson was looking for a way to salvage his reputation. He chose to align himself with former Vice President [[Aaron Burr]], who after leaving office in 1805 went on a tour of the western United States.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=146}} Burr was extremely well received by the people of Tennessee, and stayed for five days at the Hermitage.{{sfn|Parton|1860a|pp=309–310}} Burr's true intentions are not known with certainty. He seems to have been [[Burr conspiracy|planning]] a military operation to conquer [[Spanish Florida]] and drive the Spanish from [[Texas]].{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=145–147}} To many westerners like Jackson, the promise seemed enticing.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=147–148}} Western American settlers had long held bitter feelings towards the Spanish due to territorial disputes and the persistent failure of the Spanish to keep Indians living on their lands from raiding American settlements.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=47–48}} On October 4, 1806, Jackson addressed the Tennessee militia, declaring that the men should be "at a moment's warning ready to march."{{sfn|Brands|2005|p=120}} On the same day, he wrote to [[James Winchester]], proclaiming that the United States "can conquer not only the Floridas [at that time there was an East Florida and a West Florida.], but all Spanish North America." He continued: |

|||

{{quote|I have a hope (Should their be a call) that at least, two thousand Volunteers can be lead into the field at a short notice—That number commanded by firm officers and men of enterprise—I think could look into Santafee and Maxico—give freedom and commerce to those provinces and establish peace, and a permanent barier against the inroads and attacks of forreign powers on our interior—which will be the case so long as Spain holds that large country on our borders.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss27532a.12001_0001_0005/?st=gallery |title=Andrew Jackson to James Winchester, October 4, 1806 |publisher=Jackson Papers, LOC |access-date=June 25, 2017}}</ref>}} |

|||

Like most planters in the [[Southern United States]], Jackson used [[Slavery in the United States|slave labor]]. In 1804, Jackson had nine [[African Americans|African American]] slaves; by 1820, he had over 100; and by his death in 1845, he had over 150.<ref name="Hermitage_Slavery_2011">{{cite web|title=Andrew Jackson's Enslaved Laborers|url=http://www.thehermitage.com/mansion-grounds/farm/slavery |url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140912055314/http://www.thehermitage.com/mansion-grounds/farm/slavery|archive-date=September 12, 2014|access-date=April 13, 2017|publisher=The Hermitage}}</ref> Over his lifetime, he owned a total of 300 slaves.<ref>{{cite web|title=Enslaved Families: Understanding the Enslaved Families at the Hermitage|url=https://thehermitage.com/learn/slavery/enslaved-families/|website=thehermitage.com|ref=Enslaved Families Understanding the Enslaved Families at The Hermitage|access-date=August 23, 2022|archive-date=June 18, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220618122940/https://thehermitage.com/learn/slavery/enslaved-families/|url-status=dead}}</ref> Jackson subscribed to the [[Paternalism|paternalistic]] idea of slavery, which claimed that slave ownership was morally acceptable as long as slaves were treated with humanity and their basic needs were cared for.{{sfn|Warshauer|2006|p=224}} In practice, slaves were treated as a form of wealth whose productivity needed to be protected.{{sfn|Cheathem|2011|p=328–329}} Jackson directed harsh punishment for slaves who disobeyed or ran away.<ref name=":0">{{cite web|last1=Feller|first1=Daniel|author-link=Daniel Feller|last2=Mullin|first2=Marsha|date=August 1, 2019|title=The Enslaved Household of President Andrew Jackson|url=https://www.whitehousehistory.org/slavery-in-the-andrew-jackson-white-house|website=[[White House Historical Association]]}}</ref> For example, in an 1804 advertisement to recover a runaway slave, he offered "ten dollars extra, for every hundred lashes any person will give him" up to three hundred lashes—a number that would likely have been deadly.<ref name=":0" /><ref>{{cite news|last=Brown|first=DeNeen L.|date=May 1, 2017|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2017/04/11/hunting-down-runaway-slaves-the-cruel-ads-of-andrew-jackson-and-the-master-class|title=Hunting down runaway slaves: The cruel ads of Andrew Jackson and 'the master class'|newspaper=The Washington Post|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170411204030/https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2017/04/11/hunting-down-runaway-slaves-the-cruel-ads-of-andrew-jackson-and-the-master-class/|archive-date=April 11, 2017}}</ref> Over time, his accumulation of wealth in both slaves and land placed him among the elite families of Tennessee.{{sfn|Meacham|2008|p=35}} |

|||

Jackson agreed to provide boats and other provisions for the expedition.{{sfn|Snelling|1831|pp=29–31}} However, on November 10, he learned from a military captain that Burr's plans apparently included seizure of New Orleans, then part of the [[Louisiana Territory]] of the United States, and incorporating it, along with lands won from the Spanish, into a new empire. He was further outraged when he learned from the same man of the involvement of Brigadier General [[James Wilkinson]], whom he deeply disliked, in the plan.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=150–151}} Jackson acted cautiously at first, but wrote letters to public officials, including President [[Thomas Jefferson]], vaguely warning them about the scheme. In December, Jefferson, a political opponent of Burr, issued a proclamation declaring that a treasonous plot was underway in the West and calling for the arrest of the perpetrators. Jackson, safe from arrest because of his extensive paper trail, organized the militia. Burr was soon captured, and the men were sent home.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=151–158}} Jackson traveled to [[Richmond, Virginia]], to testify on Burr's behalf in trial. The defense team decided against placing him on the witness stand, fearing his remarks were too provocative. Burr was acquitted of treason, despite Jefferson's efforts to have him convicted. Jackson endorsed [[James Monroe]] for president in [[United States presidential election, 1808|1808]] against [[James Madison]]. The latter was part of the Jeffersonian wing of the Democratic-Republican Party.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=158}} |

|||

===Duel with Dickinson and adventure with Burr=== |

|||

In May 1806, Jackson fought a duel with [[Charles Dickinson (historical figure)|Charles Dickinson]]. Their dispute started over payments for a forfeited horse race, escalating for six months until they agreed to the duel.{{sfn|Moser|Macpherson|1984|pp=78–79}} Dickinson fired first. The bullet hit Jackson in the chest, but shattered against his breastbone.{{sfn|Brands|2005|p=138}} He returned fire and killed Dickinson. The killing tarnished Jackson's reputation.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=143}} |

|||

Later that year, Jackson became involved in former vice president [[Aaron Burr]]'s [[Burr conspiracy|plan]] to conquer [[Spanish Florida]] and drive the Spanish from Texas. Burr, who was touring what was then the Western United States after [[Burr–Hamilton duel|mortally wounding Alexander Hamilton in a duel]], stayed with the Jacksons at the Hermitage in 1805.{{sfn|Meacham|2008|p=27}} He eventually persuaded Jackson to join his adventure. In October 1806, Jackson wrote [[James Winchester (general)|James Winchester]] that the United States "can conquer not only [Florida], but all Spanish North America".{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=149}} He informed the Tennessee militia that it should be ready to march at a moment's notice "when the government and constituted authority of our country require it",{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=148}} and agreed to provide boats and provisions for the expedition.{{sfn|Meacham|2008|p=27}} Jackson sent a letter to President [[Thomas Jefferson]] telling him that Tennessee was ready to defend the nation's honor.{{sfn|Brands|2005|p=120}} |

|||

Jackson also expressed uncertainty about the enterprise. He warned the Governor of Louisiana [[William C. C. Claiborne|William Claiborne]] and Tennessee Senator [[Daniel Smith (surveyor)|Daniel Smith]] that some of the people involved in the adventure might be intending to break away from the United States.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=151}} In December, Jefferson ordered Burr to be arrested for treason.{{sfn|Meacham|2008|p=27}} Jackson, safe from arrest because of his extensive paper trail, organized the militia to capture the conspirators.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=153}} He testified before a grand jury in 1807, implying that it was Burr's associate [[James Wilkinson]] who was guilty of treason, not Burr. Burr was acquitted of the charges.{{sfn|Brands|2005|p=127–128}} |

|||

==Military career== |

==Military career== |

||

{{Infobox military person |

|||

===War of 1812=== |

|||

| width_style = person |

|||

| name = Military campaigns<br> of Andrew Jackson |

|||

| image = General Andrew Jackson MET DT2851 (cropped).jpg |

|||

| image_upright = 1 |

|||

| alt = Gray-haired man in army uniform with epaulettes |

|||

| caption = ''General Andrew Jackson'', an 1819 portrait by [[John Wesley Jarvis]] now housed at [[Metropolitan Museum of Art]] in New York City |

|||

| module = {{OSM Location map |

|||

| coord = {{coord|32.75|-87}} |

|||

| zoom = 5 |

|||

| float = center |

|||

| nolabels = 1 |

|||

| width = 210 |

|||

| height = 200 |

|||

| scalemark = 0 |

|||

| title = |

|||

| caption = {{legend|#117733|[[Creek War]]}}{{legend|#882255|[[War of 1812]]}}{{legend|#999933|[[Seminole Wars#First Seminole War|First Seminole War]]}} |

|||

| shapeD = circle |

|||

====Creek campaign and treaty==== |

|||

| shape-colorD = #332288 |

|||

{{Main|Creek War}} |

|||

| shape-outlineD = white |

|||

[[File:Andrew Jackson by Ralph E. W. Earl 1837.jpg|thumb|right|Portrait by [[Ralph Eleaser Whiteside Earl|Ralph E. W. Earl]], c. 1837|alt=White-haired man in blue army uniform with epaulettes]] |

|||

| label-colorD = #332288 |

|||

| label-sizeD = 12 |

|||

| label-posD = left |

|||

| label-offset-xD = 0 |

|||

| label-offset-yD = 0 |

|||

| mark-sizeD = 7 |

|||

| label1 = |

|||

Leading up to 1812, the United States found itself increasingly drawn into international conflict. Formal hostilities with Spain or France never materialized, but tensions with Britain increased for a number of [[Origins of the War of 1812|reasons]]. Among these was the [[Manifest destiny|desire]] of [[war hawk|many]] Americans for more land, particularly [[Canada under British rule|British Canada]] and Florida, the latter still controlled by Spain, Britain's European ally.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=165–169}} On June 18, 1812, Congress officially declared war on the [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland]], beginning the [[War of 1812]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/1812-01.asp |title=An Act Declaring War Between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Dependencies Thereof and the United States of America and Their Territories |date=June 18, 1812 |publisher=Yale Law School: Lillian Goldman Law Library |access-date=July 11, 2017 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20161206004103/http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/1812-01.asp |archivedate=December 6, 2016 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> Jackson responded enthusiastically, sending a letter to Washington offering 2,500 volunteers.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=169}} However, the men were not called up for many months. Biographer [[Robert V. Remini]] claims that Jackson saw the apparent slight as payback by the Madison administration for his support of Burr and Monroe. Meanwhile, the United States military repeatedly suffered devastating defeats on the battlefield.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=170}} |

|||

| mark-coord1 = {{coord|34.5657|-80.6617}} |

|||

| mark-title1 = [[Battle of Hanging Rock]] ([[American Revolutionary War|Revolutionary War]]): August 6, 1780; [[Thomas Sumter|General Thomas Sumter]], commander |

|||

| mark-description1 = [[Battle of Hanging Rock]] |

|||

| shape-color1 = #332288 |

|||

| label-color1 = #332288 |

|||

| label2 = |

|||

On January 10, 1813, Jackson led an army of 2,071 volunteers{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=173}} to [[New Orleans]] to defend the region against British and Native American attacks.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbpe.17400200/?sp=1 |title=General orders .... Andrew Jackson. Major-General 2d Division, Tennessee. November 24, 1812. |publisher=Jackson Papers, LOC |access-date=June 27, 2017}}</ref>{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|pp=23–25}}<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.loc.gov/resource/maj.03120/?sp=1&st=text |title=Journal of trip down the Mississippi River, January 1813 to March 1813 |last=Jackson |first=Andrew |publisher=Jackson Papers, LOC |access-date=July 3, 2017}}</ref> He had been instructed to serve under General Wilkinson, who commanded Federal forces in New Orleans. Lacking adequate provisions, Wilkinson ordered Jackson to halt in Natchez, then part of the [[Mississippi Territory]], and await further orders. Jackson reluctantly obeyed.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=174–175}} The newly appointed [[United States Secretary of War|Secretary of War]], [[John Armstrong Jr.]], sent a letter to Jackson dated February 6 ordering him to dismiss his forces and to turn over his supplies to Wilkinson.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.loc.gov/resource/maj.01011_0103_0105/?sp=1 |title=John Armstrong to Andrew Jackson, February 6, 1813 |publisher=Jackson Papers, LOC |access-date=July 1, 2017}}</ref> In reply to Armstrong on March 15, Jackson defended the character and readiness of his men, and promised to turn over his supplies. He also promised, instead of dismissing the troops without provisions in Natchez, to march them back to Nashville.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.loc.gov/resource/maj.01011_0233_0236/?sp=1&st=text |title=Andrew Jackson to John Armstrong, March 15, 1813 |publisher=Jackson Papers, LOC |access-date=July 1, 2017}}</ref> The march was filled with agony. Many of the men had fallen ill. Jackson and his officers turned over their horses to the sick.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=179}} He paid for provisions for the men out of his own pocket.{{sfn|Brands|2005|p=186}} The soldiers began referring to their commander as "Hickory" because of his toughness, and Jackson became known as "Old Hickory."{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=180}} The army arrived in Nashville within about a month. Jackson's actions earned him the widespread respect and praise of the people of Tennessee.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=179–180}} Jackson faced financial ruin, until his former aide-de-camp [[Thomas Hart Benton (politician)|Thomas Benton]] persuaded Secretary Armstrong to order the army to pay the expenses Jackson had incurred.<ref>''Addresses on the Presentation of the Sword of Gen. Andrew Jackson to the Congress of the United States'', Washington: Beverley Tucker, 1855, pp. 35–39</ref> On June 14, Jackson served as a second in a duel on behalf of his junior officer [[William Carroll (Tennessee politician)|William Carroll]] against Jesse Benton, the brother of Thomas. In September, Jackson and his top cavalry officer, Brigadier General [[John Coffee]], were involved in a street brawl with the Benton brothers. Jackson was severely wounded by Jesse with a gunshot to the shoulder.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=180–186}}{{sfn|Meacham|2008|pp=29–30}} |

|||

| mark-coord2 = {{coord|33.8123|-85.9069}} |

|||

| mark-title2 = [[Battle of Tallushatchee]] ([[Red Stick War]]): November 3, 1813; Brigadier General [[John Coffee]], commander |

|||

| mark-description2 = [[Battle of Tallushatchee]] |

|||

| shape-color2 = #117733 |

|||

| label-color2 = #117733 |

|||

| mark-size2 = 0 |

|||

| label3 =Talladega |

|||

On August 30, 1813, a group of [[Muscogee]] (also known as Creek Indians) called the [[Red Sticks]], so named for the color of their war paint, perpetrated the [[Fort Mims massacre]]. During the massacre, hundreds of white American settlers and non-Red Stick Creeks were slaughtered. The Red Sticks, led by chiefs [[William Weatherford|Red Eagle]] and [[Peter McQueen]], had broken away from the rest of the Creek Confederacy, which wanted peace with the United States. They were allied with [[Tecumseh]], a [[Shawnee]] chief who had launched [[Tecumseh's War]] against the United States, and who was fighting alongside the British. The resulting conflict became known as the [[Creek War]].{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|pp=23–25}} |

|||

| label-pos3 = left|jdx3=6|ldy3=-3 |

|||

| label-size3 = 9 |

|||

| mark-coord3 = {{coord|33.4509|-86.1688}} |

|||

| mark-title3 = [[Battle of Talladega]] ([[Red Stick War]]): November 9, 1813 |

|||

| mark-description3 = [[Battle of Talladega]] |

|||

| shape-color3 = #117733 |

|||

| label-color3 = black |

|||

| label4 = |

|||

[[File:Map of Land Ceded by Treaty of Fort Jackson.png|thumb|left|In the [[Treaty of Fort Jackson]], the [[Muscogee]] surrendered large parts of present-day Alabama and Georgia.|alt=Map showing in dark orange land areas ceded by Indians]] |

|||

| mark-coord4 = {{coord|33.01889|-85.70472}} |

|||

Jackson, with 2,500 men, was ordered to crush the hostile Indians. On October 10, he set out on the expedition, his arm still in a sling from fighting the Bentons. Jackson established [[Fort Strother]] as a supply base. On November 3, Coffee defeated a band of Red Sticks at the [[Battle of Tallushatchee]].{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=192–193}} Coming to the relief of friendly Creeks besieged by Red Sticks, Jackson won another decisive victory at the [[Battle of Talladega]].{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|pp=25–28}} In the winter, Jackson, encamped at Fort Strother, faced a severe shortage of troops due to the expiration of enlistments and chronic desertions. He sent Coffee with the cavalry (which abandoned him) back to Tennessee to secure more enlistments. Jackson decided to combine his force with that of the Georgia militia, and marched to meet the Georgia troops. From January 22–24, 1814, while on their way, the Tennessee militia and allied Muscogee were attacked by the Red Sticks at the [[Battles of Emuckfaw and Enotachopo Creek]]. Jackson's troops repelled the attackers, but outnumbered, were forced to withdraw to Fort Strother.{{sfn|Adams|1986|pp=791–793}} Jackson, now with over 2,000 troops, marched most of his army south to confront the Red Sticks at a fortress they had constructed at a bend in the [[Tallapoosa River]]. On March 27, enjoying an advantage of more than 2 to 1, he engaged them at the [[Battle of Horseshoe Bend (1814)|Battle of Horseshoe Bend]]. An initial artillery barrage did little damage to the well-constructed fort. A subsequent Infantry charge, in addition to an assault by Coffee's cavalry and diversions caused by the friendly Creeks, overwhelmed the Red Sticks.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=213–216}} |

|||

| mark-title4 = [[Battles of Emuckfaw and Enotachopo Creek|Battle of Emuckfaw]] ([[Red Stick War]]): on January 22, 1814 |

|||

| mark-description4 = [[Battles of Emuckfaw and Enotachopo Creek|Emuckfaw]] |

|||

| shape-color4 = #117733 |

|||

| label-color4 = #117733 |

|||

| shape-size4=7 |

|||

| label5 = Emuckfaw and |

|||

The campaign ended three weeks later with Red Eagle's surrender, although some Red Sticks such as McQueen fled to [[East Florida]].{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|pp=27–28}} On June 8, Jackson accepted a commission as [[brigadier general (United States)|brigadier general]] in the [[United States Army]], and 10 days later became a [[major general (United States)|major general]], in command of the Seventh Military Division.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=222}} Subsequently, Jackson, with Madison's approval, imposed the [[Treaty of Fort Jackson]]. The treaty required the Muscogee, including those who had not joined the Red Sticks, to surrender 23 million acres (8,093,713 ha) of land to the United States.{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|pp=27–28}} Most of the Creeks bitterly acquiesced.{{sfn|Brands|2005|p=236}} Though in ill-health from [[dysentery]], Jackson turned his attention to defeating Spanish and British forces. Jackson accused the Spanish of arming the Red Sticks and of violating the terms of their neutrality by allowing British soldiers into the Floridas.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=240}} The first charge was true,{{sfn|Adams|1986|pp=228–229}} while the second ignored the fact that it was Jackson's threats to invade Florida which had caused them to seek British protection.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=241}} In the November 7 [[Battle of Pensacola (1814)|Battle of Pensacola]], Jackson defeated British and Spanish forces in a short skirmish. The Spanish surrendered and the British fled. Weeks later, he learned that the British were planning an attack on [[New Orleans]], which sat on the mouth of the [[Mississippi River]] and held immense strategic and commercial value. Jackson abandoned Pensacola to the Spanish, placed a force in [[Mobile, Alabama]] to guard against a possible invasion there, and rushed the rest of his force west to defend the city.{{sfn|Remini|1977|pp=241–245}} |

|||

| labela5 = Enotachopo Creek |

|||

| labelb5 = |

|||

| label-pos5 = right |

|||

| label-offset-y5 = -4 |

|||

| label-offset-x5 = 5 |

|||

| label-size5= 9 |

|||

| mark-coord5 = {{coord|33.07822|-85.8817}} |

|||

| mark-title5 = [[Battles of Emuckfaw and Enotachopo Creek|Battle of Enatachopo Creek]] ([[Red Stick War]]): January 24, 1814 |

|||

| mark-description5 = [[Battles of Emuckfaw and Enotachopo Creek|Enotachopa]] |

|||

| shape-color5 = #117733 |

|||

| label-color5 = black |

|||

| mark-size5=0 |

|||

| label6 = Horseshoe Bend |

|||

The Creeks coined their own name for Jackson, ''Jacksa Chula Harjo'' or "Jackson, old and fierce."{{sfn|Jahoda|1975|p=6}} |

|||

| label-pos6= left|jdx6=-2 |

|||

|label-offset-y6=5 |

|||

| label-size6= 9 |

|||

| mark-coord6 = {{coord|32.98222|-85.735278}} |

|||

| mark-title6 = [[Battle of Horseshoe Bend]] ([[Red Stick War]]): March 27, 1814 |

|||

| mark-description6 = [[Battle of Horseshoe Bend]] |

|||

| shape-color6 = #117733 |

|||

| label-color6 = black |

|||

|mark-size6= 7 |

|||

| label7 = Pensacola |

|||

====Battle of New Orleans==== |

|||

| label-size7=9 |

|||

{{main|Battle of New Orleans}} |

|||

|label-pos7 = right |

|||

[[File:Battle of New Orleans.jpg|thumb|The ''Battle of New Orleans''. General Andrew Jackson stands on the parapet of his defenses as his troops repulse attacking [[93rd (Sutherland Highlanders) Regiment of Foot|Highlanders]], by painter [[Edward Percy Moran]] in 1910.|alt=Blue U.S. soldiers stand behind an earthen wall as red-coated British soldiers charge. Jackson stands atop the parapet with his right hand outstretched and holding a sword.]] |

|||

| mark-coord7 = {{coord|30.433333| -87.2}} |

|||

| mark-title7 = [[Battle of Pensacola (1814)|Battle of Pensacola]] ([[Red Stick War]]): November 7–9, 1814 |

|||

| mark-description7 = [[Battle of Pensacola (1814)|Battle of Pensacola]] |

|||

| shape-color7 = #117733 |

|||

| label-color7 = black |

|||

| mark-size7 = 7 |

|||

|label-offset-y7=-8 |

|||

|label-offset-x7=-2 |

|||

| label8 = |

|||

After arriving in New Orleans on December 1, 1814,{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=247}} Jackson instituted [[martial law]] in the city, as he worried about the loyalty of the city's [[Louisiana Creole people|Creole]] and Spanish inhabitants. At the same time, he formed an alliance with [[Jean Lafitte]]'s smugglers, and formed military units consisting of African-Americans and Muscogees,{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|pp=29–30}} in addition to recruiting volunteers in the city. Jackson received some criticism for paying white and non-white volunteers the same salary.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=254}} These forces, along with U.S. Army regulars and volunteers from surrounding states, joined with Jackson's force in defending New Orleans. The approaching British force, led by Admiral [[Alexander Cochrane]] and later General [[Edward Pakenham]], consisted of over 10,000 soldiers, many of whom had served in the Napoleonic Wars.{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|pp=29–30}} Jackson only had about 5,000 men, most of whom were inexperienced and poorly trained.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=274}} |

|||

| mark-coord8 = {{coord|30.228056|-88.023056}} |

|||

[[File:Andrew Jackson (1845).jpg|thumb|left|Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans, painted by [[Thomas Sully]] in 1845 from an earlier portrait he had completed from life in 1824 |alt=Gray-haired man in blue army coat and black overcoat has his left glove on and right glove on the ground. He is writing on papers and stands beside a cannon.]] |

|||

| mark-title8 = [[Fort Bowyer]] (War of 1812): October–November 1429; September 15, 1814; Major William Lawrence, commander |

|||

| mark-description8 = [[Fort Bowyer]] |

|||

| shape-color8 = #882255 |

|||

| label-color8 = black |

|||

| mark-size8 = 0 |

|||

| label9 = New |

|||

The British arrived on the east bank of the Mississippi River on the morning of December 23. That evening, Jackson attacked the British and temporarily drove them back.{{sfn|Snelling|1831|pp=73–76}} On January 8, 1815, the British launched a major frontal assault against Jackson's defenses. An initial artillery barrage by the British did little damage to the well-constructed American defenses. Once the morning fog had cleared, the British launched a frontal assault, and their troops made easy targets for the Americans protected by their parapets. Despite managing to temporarily drive back the American right flank, the overall attack ended in disaster.{{sfn|Snelling|1831|pp=81–85}} For the battle on January 8, Jackson admitted to only 71 total casualties. Of these, 13 men were killed, 39 wounded, and 19 missing or captured. The British admitted 2,037 casualties. Of these, 291 men were killed (including Pakenham), 1,262 wounded, and 484 missing or captured.{{sfn|Remini|1977|p=285}} After the battle, the British retreated from the area, and open hostilities ended shortly thereafter when word spread that the [[Treaty of Ghent]] had been signed in Europe that December. Coming in the waning days of the war, Jackson's victory made him a national hero, as the country celebrated the end of what many called the "Second American Revolution" against the British.{{sfn|Wilentz|2005|pp=29–33}} By a Congressional resolution on February 27, 1815, Jackson was given the [[Thanks of Congress]] and awarded a [[Congressional Gold Medal]].<ref name="US Congress Bio"/> |

|||

| labela9= Orleans |

|||

| label-pos9=top |

|||

| label-offset-x9= 0 |

|||

| mark-coord9 = {{coord|29.9425|-89.990833}} |

|||

| mark-title9 = [[Battle of New Orleans]] (War of 1812): October–November 1429 |

|||

| mark-description9 = [[Battle of New Orleans]] |

|||

| shape-color9 = #882255 |

|||

| label-color9 = black |

|||

| mark-size9 = 10 |

|||

| label10 = |

|||

[[Alexis de Tocqueville]] ("underwhelmed" by Jackson according to a 2001 commentator) later wrote in ''[[Democracy in America]]'' that Jackson "was raised to the Presidency, and has been maintained there, solely by the recollection of a victory which he gained, twenty years ago, under the walls of New Orleans."{{sfn|Leeden|2001|pp=32–33}} |

|||

| mark-coord10 = {{coord|29.933333|-85.016667}} |

|||

| mark-title10 = [[Negro Fort]] ([[Seminole Wars#First Seminole War|First Seminole War]]): July 1816; Brevet Major General [[Edmund P. Gaines| Edmund Gaines]], commander |

|||

| mark-description10 = [[Negro Fort]] |

|||

| shape-color10 = #999933 |

|||

| mark-size10 = 0 |

|||

| label11 = St. Marks |

|||

====Enforced martial law in New Orleans==== |

|||

| label-size11 = 9 |

|||