Economy of Australia: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

→Employment: update to October 2024 |

||

| (778 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<!-- Disclaimer is as per Wikipedia:Manual of Style (dates and numbers) #Currency --> |

{{Short description|none}} <!-- This short description is INTENTIONALLY "none" - please see WP:SDNONE before you consider changing it! --> <!-- Disclaimer is as per Wikipedia:Manual of Style (dates and numbers) #Currency --> |

||

{{Use Australian English|date= |

{{Use Australian English|date=January 2024}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date= |

{{Use dmy dates|date=January 2024}} |

||

{{Infobox economy |

{{Infobox economy |

||

|country |

| country = Australia |

||

| image = File:Sydney CBD, northeast view 20230224 1.jpg |

|||

|image = Sydney City from Waverton.jpg |

|||

|image_size |

| image_size = 310px |

||

|caption |

| caption = [[Sydney central business district|Sydney's central business district]] is Australia's largest financial and business services hub. |

||

|currency |

| currency = [[Australian Dollar]] (AUD) |

||

|year |

| year = 1 July – 30 June |

||

|organs |

| organs = [[Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation|APEC]], [[Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership|CPTPP]], [[G-20 major economies|G20]], [[Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development|OECD]], [[World Trade Organization|WTO]], [[Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership|RCEP]] |

||

| |

| group = {{plainlist| |

||

*[[Developed country|Advanced economy]]<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/April/groups-and-aggregates |title=World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024 |publisher=[[International Monetary Fund]] |website=IMF.org |access-date=16 May 2024}}</ref> |

|||

* $1.530 trillion ([[nominal GDP|nominal]]) |

|||

*[[World Bank high-income economy|High-income economy]]<ref>{{cite web |url=https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups |title=World Bank Country and Lending Groups |publisher=[[World Bank]] |website=datahelpdesk.worldbank.org |access-date=29 September 2019}}</ref> |

|||

* $1.315 trillion ([[Purchasing power parity|PPP]]) |

|||

* [[Welfare state]]<ref name="Australia_welfare"/><ref name="Kenworthy"/> |

|||

}} ([[IMF]]; 2018)<ref name=IMF>{{cite web |url=http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2018/01/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=61&pr.y=18&sy=2017&ey=2018&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=193&s=NGDPD%2CPPPGDP%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPPC&grp=0&a= |title=Report for Selected Countries and Subjects (Australia) |website=World Economic Outlook Database |publisher=[[International Monetary Fund]] |date=April 2018 |accessdate=2 November 2018}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

|gdp rank = {{hlist| |

|||

| population = {{increase}} 27,466,749 (November 2024) |

|||

|[[List of countries by GDP (nominal)|13th (nominal)]] |

|||

| gdp = {{plainlist| |

|||

|[[List of countries by GDP (PPP)|19th (PPP)]] |

|||

*{{increase}} $1.802 trillion ([[GDP (nominal)|nominal]]; 2024)<ref name="IMFWEOAU">{{cite web |url=https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/October/weo-report?c=193,&s=NGDP_RPCH,NGDPD,PPPGDP,NGDPDPC,PPPPC,PCPIPCH,&sy=2022&ey=2029&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1 |title=World Economic Outlook Database, October 2024 |publisher=[[International Monetary Fund]] |website=IMF.org}}</ref> |

|||

}} (IMF; 2018)<ref name="gdp-rank" /><ref name="gdpPPP-rank" /> |

|||

*{{increase}} $1.898 trillion ([[Purchasing power parity|PPP]]; 2024)<ref name="IMFWEOAU"/> |

|||

|per capita = {{plainlist| |

|||

}} |

|||

* $58,941 (nominal) |

|||

| gdp rank = {{plainlist| |

|||

* $52,191 (PPP) |

|||

*[[List of countries by GDP (nominal)|14th (nominal, 2024)]] |

|||

}} (IMF; 2018)<ref name=IMF/> |

|||

*[[List of countries by GDP (PPP)|19th (PPP, 2024)]] |

|||

|per capita rank = {{hlist| |

|||

}} |

|||

|[[List of countries by GDP per capita (nominal)|10th (nominal)]] |

|||

| |

| per capita = {{plainlist| |

||

*{{increase}} $65,966 (nominal; 2024)<ref name="IMFWEOAU"/> |

|||

}} (IMF; 2018)<ref name="gdp-perCapRank">{{cite web|title=GDP per capita (current US$)|url=https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD|website=World Bank Open Data|publisher=[[World Bank]]|accessdate=6 September 2018}}</ref><ref name="gdpPPP-perCapRank">{{cite web|title=GDP per capita, PPP (current international $)|url=https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD|website=World Bank Open Data|publisher=[[World Bank]]|accessdate=6 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

*{{increase}} $69,475 (PPP; 2024)<ref name="IMFWEOAU"/> |

|||

|growth = 0.6% (Q3 2017)<ref name="abs-NatlAccs-Jun2017">{{cite web|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/5206.0 |title=5206.0 – Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product, Jun 2017 |website=[[Australian Bureau of Statistics]] |date=6 September 2017 |access-date=6 September 2017}}</ref><ref name="ecoIndicatorsSnap">{{cite web|url=http://www.rba.gov.au/snapshots/economy-indicators-snapshot/ |title=Key Economic Indicators Snapshot |website=[[Reserve Bank of Australia]] |date=26 July 2017 |accessdate=14 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

|sectors = {{plainlist| |

|||

| per capita rank = {{plainlist| |

|||

* [[Tertiary sector of the economy|Services]]: 61.1% |

|||

*[[List of countries by GDP per capita (nominal)|12th (nominal, 2024)]] |

|||

* Construction: 8.1% |

|||

*[[List of countries by GDP per capita (PPP)|23rd (PPP, 2024)]] |

|||

* Mining: 6.9% |

|||

}} |

|||

* Manufacturing: 6.0% |

|||

| growth = {{plainlist| |

|||

* Agriculture: 2.2% (2016)<ref name="industrySectors-2016" />}} |

|||

*3.8% (2022) |

|||

|inflation = {{hlist| |

|||

*2.1% (2023) |

|||

| 1.8% annual |

|||

*1.5% (2024)<ref name="IMFWEOAU"/> |

|||

| 0.6% quarterly |

|||

}} |

|||

}} (Sep Qtr 2017)<ref name="inflation-abs">{{cite web|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6401.0 |title=6401.0 – Consumer Price Index, Australia, Sep 2017 |website=[[Australian Bureau of Statistics]] |date=25 October 2017 |accessdate=25 October 2017}}</ref> |

|||

| sectors = {{plainlist| |

|||

|population living below poverty line |

|||

* [[Tertiary sector of the economy|Services]]: 62.7% |

|||

|13.3% (2016)<ref name="poverty">{{cite web|url=https://www.acoss.org.au/poverty/}}</ref> |

|||

* Construction: 7.4% |

|||

|gini = 0.333 (2014)<ref name="abs-wealthDistribution-2014">{{cite web|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/6523.0~2013-14~Main%20Features~Income%20and%20Wealth%20Distribution~6 |title=6523.0 – Household Income and Wealth, Australia, 2013–14 |website=[[Australian Bureau of Statistics]] |date=28 July 2016 |accessdate=5 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

* Mining: 5.8% |

|||

|labor = 12.7 million (2017)<ref>{{cite web|title=Labor force, total|url=http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.TOTL.IN|website=World Bank Open Data|publisher=[[World Bank]]|accessdate=5 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

* Manufacturing: 5.8% |

|||

|occupations = {{plainlist| |

|||

* Agriculture: 2.8% (2017)<ref name="indins2018" />}} |

|||

* Services: 79.2% |

|||

| inflation = {{plainlist| |

|||

* Construction: 8.8% |

|||

* 7% (March 2023)<ref>{{cite web|url = https://www.forbes.com/advisor/au/personal-finance/inflation-rate-australia/|title = Australian Inflation Rate: Annual CPI Falls To 7%|work = Forbes|access-date = 26 April 2023}}</ref>}} |

|||

* Manufacturing: 7.4% |

|||

| poverty = 13.4% (2020)<ref name="poverty">{{cite web |last1=Dorsch |first1=Penny |title=One in eight people in Australia are living in poverty |url=https://povertyandinequality.acoss.org.au/poverty/one-in-eight-people-in-australia-are-living-in-poverty/ |publisher=ACOSS}}</ref> |

|||

* Agriculture: 2.7% |

|||

| gini = {{decreasePositive}} 33.0 {{color|darkorange|medium}} (2021)<ref>{{cite web|url = https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/aus/228/welfare-in-australia/international-comparisons-of-welfare-data|title = International comparisons of welfare data|publisher = Australian Institute of Health and Welfare|access-date = 19 January 2023|archive-date = 21 November 2022|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20221121144429/https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/aus/228/welfare-in-australia/international-comparisons-of-welfare-data|url-status = dead}}</ref> |

|||

* Mining: 1.9% (2016)<ref name="industrySectors-2016" /> |

|||

| hdi = {{plainlist| |

|||

*{{decrease}} 0.946 {{color|darkgreen|very high}} (2022)<ref name="auhdi">{{Cite web |date=13 March 2024 |title=Human Development Report 2023/2024 |url=https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2023-24reporten.pdf|url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240313164319/https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2023-24reporten.pdf |archive-date=13 March 2024 |access-date=21 April 2024 |publisher=[[United Nations Development Programme]] |language=en}}</ref> ([[List of countries by Human Development Index|10th]]) |

|||

*{{decrease}} 0.860 {{color|darkgreen|very high}} [[List of countries by inequality-adjusted HDI|IHDI (14th)]] (2022)<ref name="auhdi"/>}} |

|||

| cpi = {{steady}} 75 out of 100 points (2023, [[Corruption Perceptions Index|14th rank]]) |

|||

| labor = {{plainlist| |

|||

*{{increase}} 14.5 million (September 2024)<ref name="empRates-abs"/> |

|||

*{{increase}} 77.6% employment rate (Q3-2023)<ref>{{cite web |title=Employment rate |url=https://data.oecd.org/emp/employment-rate.htm?context=AUS |website=data.oecd.org |publisher=OECD |access-date=22 June 2024}}</ref>}} |

|||

| occupations = {{plainlist| |

|||

* Services: 78.8% |

|||

* Construction: 9.2% |

|||

* Manufacturing: 7.5% |

|||

* Agriculture: 2.5% |

|||

* Mining: 1.9% (2017)<ref name="indins2018" /> |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

| average gross salary = A$7,890 / $5,454.58 PPP monthly<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/7dab7e4b-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/7dab7e4b-en | title=Home}}</ref> (2022) |

|||

|average gross salary = {{plainlist| |

|||

| average net salary = A$6,076 / $4,200.25 PPP monthly<ref>{{cite web | url=https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/taxation/taxing-wages-2023_8c99fa4d-en#page172 | title=Taxing Wages 2023: Indexation of Labour Taxation and Benefits in OECD Countries | READ online}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/8c99fa4d-en/1/3/1/6/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/8c99fa4d-en&_csp_=f4d3c57328afb7f1cbd530cb119213be&itemIGO=oecd&itemContentType=book | title=Home }}</ref> (2022) |

|||

* AUD weekly (May 2017):<ref name="earnings-abs">{{cite web|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6302.0?opendocument&ref=HPKI|title=6302.0 – Average Weekly Earnings, Australia, May 2017|website=[[Australian Bureau of Statistics]]|date=17 August 2017|accessdate=24 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

| unemployment = {{plainlist| |

|||

{{unbulleted list| A$1,605 (full-time adult) | A$1,179 (all employees)}} |

|||

*{{steady}} 4.1% (September 2024)<ref name="empRates-abs">{{cite web|url=https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-australia/sep-2024 |title=6202.0 – Labour Force, Australia, September 2024 |website=[[Australian Bureau of Statistics]] |date=17 October 2024|access-date=19 October 2024}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

*{{decreasePositive}} 615.7 thousand unemployed (September 2024)<ref name="empRates-abs"/> |

|||

|unemployment = 5.5% (February 2018)<ref name="empRates-abs">{{cite web|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6202.0 |title=6202.0 – Labour Force, Australia, Sep 2017 |website=[[Australian Bureau of Statistics]] |date=19 October 2017 |accessdate=19 October 2017}}</ref> |

|||

*{{decreasePositive}} 9.5% youth unemployment (September 2024; 15 to 24 year-olds)<ref name="empRates-abs"/>}} |

|||

|industries = {{hlist |

|||

| industries = {{hlist |

|||

| [[Financial services|Financial]] and insurance services |

| [[Financial services|Financial]] and insurance services |

||

| Construction |

| Construction |

||

| Healthcare and [[social assistance]] |

| Healthcare and [[social assistance]] |

||

| Mining |

| Mining |

||

| Professional, [[scientific]] and technical services<ref name="busgov-proSciTech">{{cite web |url=https://www.business.gov.au/info/plan-and-start/develop-your-business-plans/industry-research/professional-scientific-and-technical-services-industry-fact-sheet |title=Professional, scientific & technical services industry fact sheet |website=business.gov.au |publisher=[[Australian Government]] |date=7 June 2017 | |

| Professional, [[scientific]] and technical services<ref name="busgov-proSciTech">{{cite web |url=https://www.business.gov.au/info/plan-and-start/develop-your-business-plans/industry-research/professional-scientific-and-technical-services-industry-fact-sheet |title=Professional, scientific & technical services industry fact sheet |website=business.gov.au |publisher=[[Australian Government]] |date=7 June 2017 |access-date=6 September 2017 |archive-date=6 September 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170906181208/https://www.business.gov.au/info/plan-and-start/develop-your-business-plans/industry-research/professional-scientific-and-technical-services-industry-fact-sheet |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

||

| Manufacturing<ref name="abs-NatlAccs-201706">{{cite report|author=Australian Bureau of Statistics|author-link=Australian Bureau of Statistics|date=6 September 2017|title=5206.0 – Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product (June Quarter 2017)|url =http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/meisubs.nsf/0/49FFA7822CD4303DCA258192001DA782/$File/52060_jun%202017.pdf|chapter=Industry Gross Value Added|pages=33, 36|access-date=26 October 2017 |

| Manufacturing<ref name="abs-NatlAccs-201706">{{cite report|author=Australian Bureau of Statistics|author-link=Australian Bureau of Statistics|date=6 September 2017|title=5206.0 – Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product (June Quarter 2017)|chapter-url =http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/meisubs.nsf/0/49FFA7822CD4303DCA258192001DA782/$File/52060_jun%202017.pdf|chapter=Industry Gross Value Added|pages=33, 36|access-date=26 October 2017 |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| exports = A$671.1 billion (2023)<ref name=abs_trade>{{cite web|title=International Trade: Supplementary Information, Calendar Year|url=https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/international-trade/international-trade-supplementary-information-calendar-year/2023|publisher=[[Australian Bureau of Statistics]]|access-date=11 May 2024}}</ref> |

|||

|edbr = {{decrease}} 18th (2019)<ref name="edbr-worldbank">{{cite web |url=http://www.doingbusiness.org/data/exploreeconomies/australia |title=Ease of Doing Business in Australia |website=''Doingbusiness.org'' |publisher=[[The World Bank]] |accessdate=24 November 2017}}</ref> |

|||

| export-goods = iron ore, coal, natural gas, gold, aluminium, beef, crude petroleum, copper, meat (non-beef)<ref name=abs_trade /> |

|||

|exports = $190.2 billion (2016)<ref name=wto_stat>{{cite web|title=Trade Profiles: Australia|url=http://stat.wto.org/CountryProfile/WSDBCountryPFView.aspx?Country=AU&Language=F|work=WTO Statistics Database|publisher=[[World Trade Organization]]|accessdate=5 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

| export-partners = {{ublist |

|||

|export-goods = iron ore, coal, [[Liquefied petroleum gas|petroleum gases]], gold, [[Corundum#Synthetic corundum|synthetic corundum]], wheat and [[meslin]], [[bovine]] meat, [[wool]], meat of [[sheep meat|sheep]] or [[goat meat|goat]]<ref name=wto_stat /> |

|||

| {{flag|China}}(+) 32.6% |

|||

|export-partners = {{ublist| {{flag|China}} 31.6%| {{flag|Japan}} 13.9%| {{flag|European Union}} 7.5%| {{flag|South Korea}} 6.7%| {{flag|United States}} 4.6% |Other 35.6%<ref name=wto_stat/> }} |

|||

| {{flag|Japan}}(-) 13.4% |

|||

|imports = $196.1 billion (2016)<ref name=wto_stat/> |

|||

| {{flag|South Korea}}(-) 6.5% |

|||

|import-goods = cars, petroleum, [[automatic data processing equipment]], [[medicaments]], other food preparations, cigars, wine, [[baked goods]], alcohol of less than 80% volume<ref name=wto_stat /> |

|||

| {{flag|India}}(+) 5.2% |

|||

|import-partners = {{ublist| {{flag|China}} 23.4%| {{flag|European Union}} 19.3%| {{flag|United States}} 11.5%| {{flag|Japan}} 7.7%| |

|||

{{flag| |

| {{flag|United States}}(+) 5.0%<ref name=abs_trade/>}} |

||

| imports = A$526.8 billion (2023)<ref name=abs_trade/> |

|||

|FDI = {{unbulleted list| Inward: $576.037 billion |Outward: $401.506 billion}} ([[UNCTAD]] 2016)<ref name="unctd-2017">{{cite web|title=Country Fact Sheet: Australia |series=World Investment Report 2017 |url=http://unctad.org/sections/dite_dir/docs/wir2017/wir17_fs_au_en.pdf |website=[[United Nations Conference on Trade and Development]] |accessdate=25 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

| import-goods = petroleum, cars, telecom equipment and parts, goods vehicles, computers, medicaments, gold, civil engineering equipment, furniture<ref name=abs_trade/> |

|||

|debt = 42.3% of GDP (October 2017)<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/GGXWDG_NGDP@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/AUS#as|title= General government gross debt|publisher=[[IMF]]|year=2017|accessdate=11 February 2017}}</ref> |

|||

| import-partners = {{ublist |

|||

|gross external debt = US$1.487 trillion (30 June 2017)<ref>{{cite web|title=1344.0 – International Monetary Fund – Special Data Dissemination Standard, 2017|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats%5Cabs@.nsf/0/F819B0F0ED6658B1CA257C76007C944E?Opendocument|website=[[Australian Bureau of Statistics]]|date=20 September 2017|accessdate=25 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

| {{flag|China}}(-) 20.5% |

|||

|revenue = $461 billion (2017 est.) |

|||

| {{flag|United States}}(+) 12.4% |

|||

|expenses = $484 billion (2017 est.) |

|||

| {{flag|Japan}}(+) 5.8% |

|||

|aid = ''donor'': [[Official development assistance|ODA]], $3.02 billion (2016)<ref name="oecd-aid">{{cite web|title=Development aid rises again in 2016 but flows to poorest countries dip |url=http://www.oecd.org/dac/development-aid-rises-again-in-2016-but-flows-to-poorest-countries-dip.htm |website=[[OECD]] |accessdate=25 September 2017 |date=11 April 2017 }}</ref> |

|||

| {{flag|South Korea}}(-) 5.2% |

|||

|credit = {{plainlist| |

|||

|{{flag|Singapore}}(+) 4.5%<ref name=abs_trade/>}} |

|||

* [[Standard & Poor's]]:<ref name="SnP2017-abc">{{cite web|last=Janda|first=Michael|title=Federal budget 2017: Standard & Poor's reaffirms Australia's AAA credit rating|url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/story-streams/federal-budget-2017/2017-05-17/federal-budget-2017-standard-and-poors-credit-rating/8533114|publisher=[[Australian Broadcasting Corporation]]|date=17 May 2017|accessdate=25 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

| current account = {{increase}} A$14.1 billion (2022)<ref>{{cite web|title=Balance of Payments and International Investment Position, Australia, Dec 2022|date=28 February 2023 |url=https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/international-trade/balance-payments-and-international-investment-position-australia/dec-2022|publisher=[[Australian Bureau of Statistics]]|access-date=18 March 2023}}</ref> |

|||

{{hlist|AAA |Outlook: Negative}} |

|||

| FDI = {{unbulleted list| Inward: $682.9 billion |Outward: $491.0 billion}} ([[UNCTAD]] 2018)<ref name="unctd-2019">{{cite web |title=Country Fact Sheet: Australia |series=World Investment Report 2019 |url=http://unctad.org/sections/dite_dir/docs/wir2019/wir19_fs_au_en.pdf |website=[[United Nations Conference on Trade and Development]] |access-date=3 August 2019 |archive-date=3 August 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190803083710/https://unctad.org/sections/dite_dir/docs/wir2019/wir19_fs_au_en.pdf |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Moody's]]:<ref name="Moodys2017">{{cite web|last=Uren|first=David|title=Australia on track to keep AAA rating, says Moody's|url=http://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/economics/australia-on-track-to-keep-aaa-rating-says-moodys/news-story/8f16dbdfd43cd5b7b0ef3a92d3889037|archive-url=http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:drThrdR91IEJ:www.theaustralian.com.au/business/economics/australia-on-track-to-keep-aaa-rating-says-moodys/news-story/8f16dbdfd43cd5b7b0ef3a92d3889037|website=[[The Australian]]|date=24 August 2017|archive-date=2017-09-23|accessdate=25 September 2017}}; {{cite web|agency=Australian Associated Press|author-link=Australian Associated Press|title=Australia's credit rating safe for now: Moody's|url=https://indaily.com.au/news/2017/03/09/australias-credit-rating-safe-for-now-moodys/|website=In Daily|date=9 March 2017|accessdate=25 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

| debt = 66.4% of GDP (October 2021)<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/profile/AUS|title= General government gross debt|publisher=[[IMF]]|year=2022|access-date=27 February 2022}}</ref> |

|||

| gross external debt = {{decreasePositive}} US$2.095 trillion (Q1, 2019)<ref>{{cite web|title=1344.0 – International Monetary Fund – Special Data Dissemination Standard, 2017|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats%5Cabs@.nsf/0/F819B0F0ED6658B1CA257C76007C944E?Opendocument|publisher=[[Australian Bureau of Statistics]] |access-date=2 July 2019}}</ref> |

|||

| revenue = A$668.1 billion (2023)<ref name="AUS_BUDGET"/> |

|||

| expenses = A$682.1 billion (2023)<ref name="AUS_BUDGET"/> |

|||

| balance = −0.2% (of GDP) (2019)<ref name="AUS_BUDGET">{{cite web|url=https://www.budget.gov.au/2019-20/content/overview.htm|title=Budget 2019-20|publisher=[[Department of the Treasury (Australia)|Department of the Treasury]]|access-date=3 August 2019|archive-date=3 April 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190403095034/https://www.budget.gov.au/2019-20/content/overview.htm|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>After [[Future Fund]] adjustments</ref> |

|||

| aid = ''donor'': [[Official development assistance|ODA]], $4.09 billion (2022)<ref name="oecd-aid">{{cite web|title=Australian Official Development Assistance budget summary 2022-23 |url=https://www.dfat.gov.au/about-us/corporate/portfolio-budget-statements/oda-budget-summary-2022-23 |website=[[OECD]] |access-date=7 November 2023 |date=10 March 2023}}</ref> |

|||

| credit = {{plainlist| |

|||

* [[Standard & Poor's]]:<ref name="SandPs2018">{{cite news |last1=Pupazzoni |first1=Rachel |title=S&P raises Australia's budget outlook to stable, reaffirms AAA credit rating |url=https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-09-21/australia-budget-outlook-stable-standard-&-poors-says/10290878 |work=ABC News |date=21 September 2018 |language=en-AU}}</ref> |

|||

{{hlist|AAA |Outlook: Stable}} |

{{hlist|AAA |Outlook: Stable}} |

||

* [[Moody's]]:<ref name="Moodys2017">{{cite web|last=Uren|first=David|title=Australia on track to keep AAA rating, says Moody's|url=http://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/economics/australia-on-track-to-keep-aaa-rating-says-moodys/news-story/8f16dbdfd43cd5b7b0ef3a92d3889037|website=[[The Australian]]|date=24 August 2017|access-date=25 September 2017}}{{dead link|date=February 2024|bot=medic}}; {{cite web|agency=Australian Associated Press|title=Australia's credit rating safe for now: Moody's|url=https://indaily.com.au/news/2017/03/09/australias-credit-rating-safe-for-now-moodys/|website=In Daily|date=9 March 2017|access-date=25 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Fitch Group|Fitch]]:<ref name="Fitch2017-reuters">{{cite web|author=Fitch Ratings|author-link=Fitch Ratings|title=Fitch Affirms Australia at 'AAA'/Stable|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/fitch-affirms-australia-at-aaa-stable/fitch-affirms-australia-at-aaa-stable-idUSFit999157|agency=[[Reuters]]|date=12 May 2017|accessdate=25 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

{{hlist|AAA |Outlook: Stable}} |

|||

* [[Fitch Group|Fitch]]:<ref name="Fitch2017-reuters">{{cite web|author=Fitch Ratings|author-link=Fitch Ratings|title=Fitch Affirms Australia at 'AAA'/Stable|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/fitch-affirms-australia-at-aaa-stable/fitch-affirms-australia-at-aaa-stable-idUSFit999157|work=[[Reuters]]|date=12 May 2017|access-date=25 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

{{hlist|AAA |Outlook: Stable}} |

{{hlist|AAA |Outlook: Stable}} |

||

}} |

}} |

||

|reserves |

| reserves = $66.58 billion (31 December 2017 est.)<ref name="CIAWFAS">{{cite web |url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/australia/ |title=The World Factbook |publisher=[[Central Intelligence Agency]] |website=CIA.gov |access-date=2 July 2019}}</ref> |

||

|cianame |

| cianame = australia |

||

|spelling |

| spelling = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

[[Australia]] is a [[Developed country|highly developed]] country with a [[mixed economy]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Griggs |first=Lynden |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1101177329 |title=Commercial and economic law in Australia |date=2018 |others=John McLaren, James Scheibner, George Cho, E. Eugene Clark |isbn=978-94-035-0701-9 |edition=3rd |location=Alphen aan den Rijn, the Netherlands |pages=337 |oclc=1101177329 |quote=Australia is a mixed market economy}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Nieuwenhuysen|first1=John|last2 = Lloyd|first2= Peter|last3=Mead|first3= Margaret |date=2001 |title=Reshaping Australia's Economy: Growth with Equity and Sustainability |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bAyB2IQWGREC&q=australian+market+economy |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |page=179 |isbn=978-0521011204}}</ref> As of 2023, Australia was the [[List of countries by GDP (nominal)|14th-largest national economy]] by [[nominal GDP]] ([[gross domestic product]]),<ref name="gdp-rank">{{cite web|title=GDP ranking|url=https://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/GDP-ranking-table|website=World Bank Open Data|publisher=[[World Bank]]|access-date=13 May 2019|date=April 2019}}</ref> the 19th-largest by [[Purchasing power parity|PPP-adjusted]] GDP,<ref name="gdpPPP-rank">{{cite web|title=GDP ranking, PPP based|url=https://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/GDP-PPP-based-table|website=World Bank Open Data|publisher=[[World Bank]]|access-date=13 May 2019|date=25 April 2019}}</ref> and was the [[List of countries by exports|21st-largest goods exporter]] and [[List of countries by imports|24th-largest goods importer]].<ref name="ciafactbook">{{cite web|title=AUSTRALIA-OCEANIA :: AUSTRALIA|url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/australia/|website=[[The World Factbook]]|publisher=[[CIA]]|access-date=25 September 2017|date=6 September 2017}}</ref> Australia took the record for the longest run of uninterrupted [[GDP growth]] in the [[developed world]] with the March 2017 [[financial quarter]]. It was the 103rd quarter and the 26th year since the country had a technical [[recession]] (two consecutive quarters of negative growth).<ref name="smh-Bagshaw-201706">{{cite web|last1=Bagshaw|first1=Eryk|last2=Massola|first2=James|title=GDP: Australia grabs record for longest time without a recession|url=https://www.smh.com.au/business/the-economy/gdp-australia-grabs-record-for-longest-time-without-a-recession-20170606-gwm0o2.html|website=[[The Sydney Morning Herald]]|access-date=6 September 2017|date=7 June 2017}}</ref> As of June 2021, the country's GDP was estimated at $1.98 trillion.<ref name="abs-ecoIndicators">{{cite web |title=Key economic indicators |url=https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/key-indicators |publisher=Australian Bureau of Statistics |access-date=16 September 2021}}</ref> |

|||

The Australian economy is dominated by its [[service sector]], which in 2017 comprised 62.7% of the GDP and employed 78.8% of the labour force.<ref name="indins2018">{{cite web |title=Industry Insights |url=https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/industry-insights |website=Office of the Chief Economist |date=22 May 2018 |publisher=Department of Industry, Innovation and Science |access-date=9 January 2020 |archive-date=28 February 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190228050805/https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/industry-insights |url-status=dead}}</ref> At the height of the mining boom in 2009–10, the total value-added of the mining industry was 8.4% of GDP.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/1301.0~2012~Main%20Features~Mining%20Industry~150|title=Mining Industry – Economic Contribution|publisher=ABS|access-date=7 April 2015}}</ref> Despite the recent decline in the mining sector, the Australian economy has remained resilient and stable<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.smh.com.au/business/markets/currencies/aussie-jumps-on-gdp-data-20160302-gn8768.html|title=Aussie jumps on surprising economic strength|work=[[The Sydney Morning Herald]]|date=2 March 2016|access-date=4 March 2016|archive-date=2 March 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160302133656/http://www.smh.com.au/business/markets/currencies/aussie-jumps-on-gdp-data-20160302-gn8768.html|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.9news.com.au/national/2016/03/02/03/37/economy-likely-ended-2015-on-soft-note|title=Economy puts aside post-mining boom blues|work=[[Nine Network]] News|date=2 March 2016|access-date=4 March 2016}}</ref> and did not experience a recession from 1991 until 2020.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/business-39124272 |title=Australia goes 25 years with recession |publisher=[[BBC]] |date=1 March 2017 |access-date=26 July 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/03/economy/australia-recession/index.html|title=Australia suffers first recession in 29 years|publisher=[[CNN]] |date=3 June 2020 |access-date=16 July 2020}}</ref> Among [[OECD]] members, Australia has a highly efficient and strong [[Social security in Australia|social security system]], which comprises [[Welfare state#Effects|roughly 25% of GDP]].<ref name="Kenworthy">{{Cite journal |jstor = 3005973|title = Do Social-Welfare Policies Reduce Poverty? A Cross-National Assessment|journal = Social Forces|volume = 77|issue = 3|pages = 1119–1139|last1 = Kenworthy|first1 = Lane|year = 1999|doi = 10.2307/3005973|url = http://www.lisdatacenter.org/wps/liswps/188.pdf|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20130810134045/http://www.lisdatacenter.org/wps/liswps/188.pdf|archive-date = 10 August 2013|url-status = live}}</ref><ref name="Bradley et al.">{{Cite journal |jstor = 3088901|title = Determinants of Relative Poverty in Advanced Capitalist Democracies|journal = American Sociological Review|volume = 68|issue = 1|pages = 22–51|last1 = Moller|first1 = Stephanie|last2 = Huber|first2 = Evelyne|last3 = Stephens|first3 = John D.|last4 = Bradley|first4 = David|last5 = Nielsen|first5 = François|year = 2003|doi = 10.2307/3088901}}</ref><ref name="Australia_welfare">{{Cite web | url=http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SOCX_AGG | title=Social Expenditure – Aggregated data|work=[[OECD]] }}</ref> |

|||

The '''economy of Australia''' is a large [[mixed-market]] economy, with a GDP of A$1.69 trillion as of 2017.<ref name="abs-ecoIndicators">{{cite web|title=1345.0 – Key Economic Indicators, 2017|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/mf/1345.0?opendocument?opendocument#from-banner=LN|website=[[Australian Bureau of Statistics]]|accessdate=6 September 2017}}</ref> In 2018 Australia overtook [[Switzerland]], and became the country with the largest median wealth per adult.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Urs|first=Rohner|date=October 2018|title=Global Wealth Report 2018|url=http://publications.credit-suisse.com/tasks/render/file/index.cfm?fileid=B4A3FC6E-942D-C103-3D14B98BA7FD0BCC|journal=Credit Suisse - Research Institute|language=English|publisher=Credit Suisse|volume=|pages=7|via=}}</ref> Australia's total wealth was AUD$8.9 trillion as of June 2016.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.businessinsider.com.au/australian-household-wealth-now-stands-at-8-9-trillion-2016-9 |title=Australian household wealth now stands at $8.9 trillion |publisher=businessinsider.com.au |accessdate=26 July 2017}}</ref> In 2016, Australia was the 14th-largest national economy by [[nominal GDP]],<ref name="gdp-rank">{{cite web|title=GDP ranking|url=https://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/GDP-ranking-table|website=World Bank Open Data|publisher=[[World Bank]]|accessdate=6 September 2017|date=1 July 2017}}</ref> 20th-largest by [[Purchasing power parity|PPP-adjusted]] GDP,<ref name="gdpPPP-rank">{{cite web|title=GDP ranking, PPP based|url=https://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/GDP-PPP-based-table|website=World Bank Open Data|publisher=[[World Bank]]|accessdate=6 September 2017|date=1 July 2017}}</ref> and was the 25th-largest goods exporter and 20th-largest goods importer.<ref name="ciafactbook">{{cite web|title=AUSTRALIA-OCEANIA :: AUSTRALIA|url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/geos/as.html|website=[[The World Factbook]]|publisher=[[CIA]]|accessdate=25 September 2017|date=6 September 2017}}</ref> Australia took the record for the longest run of uninterrupted [[GDP growth]] in the developed world with the March 2017 [[financial quarter]], the 103rd quarter and marked 26 years since the country had a technical [[recession]] (two consecutive quarters of negative growth).<ref name="smh-Bagshaw-201706">{{cite web|last1=Bagshaw|first1=Eryk|last2=Massola|first2=James|title=GDP: Australia grabs record for longest time without a recession|url=http://www.smh.com.au/business/the-economy/gdp-australia-grabs-record-for-longest-time-without-a-recession-20170606-gwm0o2.html|website=[[The Sydney Morning Herald]]|accessdate=6 September 2017|date=7 June 2017}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Australian Securities Exchange]] in [[Sydney]] is the 16th-largest [[stock exchange]] in the world in terms of domestic [[market capitalisation]]<ref name="dfat-top20">{{cite web|url=http://dfat.gov.au/trade/resources/Pages/australia-is-a-top-20-country.aspx|title=Australia is a top 20 country|date=18 May 2017|website=[[Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia)|Australian Government: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade]]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170906224623/http://dfat.gov.au/trade/resources/Pages/australia-is-a-top-20-country.aspx|archive-date=6 September 2017|url-status=dead|access-date=6 September 2017}}</ref> and has one of the largest [[interest rate derivatives]] markets in the [[Asia-Pacific|Asia-Pacific region]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Corporate Overview|url=http://www.asx.com.au/about/corporate-overview.htm|website=[[Australian Securities Exchange]]|access-date=6 September 2017|archive-date=17 April 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190417114058/https://www.asx.com.au/about/corporate-overview.htm|url-status=dead}}</ref> Some of Australia's largest companies include [[Commonwealth Bank]], [[BHP]], [[CSL Limited|CSL]], [[Westpac]], [[National Australia Bank|NAB]], [[ANZ Bank|ANZ]], [[Fortescue (company)|Fortescue]], [[Wesfarmers]], [[Macquarie Group]], [[Woolworths Group (Australia)|Woolworths Group]], [[Rio Tinto (corporation)|Rio Tinto]], [[Telstra]], [[Woodside Energy]] and [[Transurban]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=ASX Listed Companies (Full List) - Market Index|url=https://www.marketindex.com.au/asx-listed-companies|access-date=2021-05-14|website=MarketIndex.com.au|language=en}}</ref> The currency of Australia and its territories is the [[Australian dollar]], which it shares with several Pacific nation states. |

|||

The Australian economy is dominated by its [[service sector]], comprising 61.1% of the GDP and employing 79.2% of the labour force in 2016.<ref name="industrySectors-2016">{{cite web |url=https://www.industry.gov.au/Office-of-the-Chief-Economist/Publications/AustralianIndustryReport/assets/Australian-Industry-Report-2016-Chapter-2.pdf |title=Australian Industry Report 2016, Chapter 2: Economic Conditions |website=[[Department of Industry, Innovation and Science|Australian Government: Department of Industry, Innovation and Science]] |page=33 |accessdate=5 September 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170905234451/https://www.industry.gov.au/Office-of-the-Chief-Economist/Publications/AustralianIndustryReport/assets/Australian-Industry-Report-2016-Chapter-2.pdf |archive-date=5 September 2017 |dead-url=yes |df=dmy-all }}</ref> East Asia (including [[ASEAN]] and Northeast Asia) is a top export destination, accounting for about 64% of exports in 2016.<ref name=austrade-exports2016>{{cite web|last=Thirlwell|first=Mark|title=Australia's export performance in 2016|url=https://www.austrade.gov.au/news/economic-analysis/australias-export-performance-in-2016|website=[[Austrade]]|accessdate=10 September 2017|date=16 June 2017}}</ref> Australia has the eighth-highest total estimated value of natural resources, valued at US$19.9 trillion in 2016.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.investopedia.com/articles/markets-economy/090516/10-countries-most-natural-resources.asp|title=10 Countries with the Most Natural Resources|date=12 September 2016|last=Anthony|first=Craig|website=[[Investopedia]]}}</ref> At the height of the mining boom in 2009–10, the total value-added of the mining industry was 8.4% of GDP.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/1301.0~2012~Main%20Features~Mining%20Industry~150|title=Mining Industry – Economic Contribution|publisher=ABS|accessdate=7 April 2015}}</ref> Despite the recent decline in the mining sector, the Australian economy has remained resilient and stable<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.smh.com.au/business/markets/currencies/aussie-jumps-on-gdp-data-20160302-gn8768.html|title=Aussie jumps on surprising economic strength|work=[[The Sydney Morning Herald]]|date=2 March 2016|accessdate=4 March 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.9news.com.au/national/2016/03/02/03/37/economy-likely-ended-2015-on-soft-note|title=Economy puts aside post-mining boom blues|work=[[Nine Network]] News|date=2 March 2016|accessdate=4 March 2016}}</ref> and has not experienced a recession since July 1991.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/business-39124272 |title=Australia goes 25 years with recession |publisher=[[BBC]] |date=1 March 2017 |accessdate=26 July 2017}}</ref> |

|||

Australia's economy is strongly intertwined with the countries of [[East Asia|East]] and [[Southeast Asia]], also known as [[ASEAN#ASEAN Plus Three|ASEAN Plus Three]] (APT), accounting for about 64% of exports in 2016.<ref name=austrade-exports2016>{{cite web|last=Thirlwell|first=Mark|title=Australia's export performance in 2016|url=https://www.austrade.gov.au/news/economic-analysis/australias-export-performance-in-2016|website=[[Austrade]]|access-date=10 September 2017|date=16 June 2017|archive-date=11 September 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170911030005/https://www.austrade.gov.au/news/economic-analysis/australias-export-performance-in-2016|url-status=dead}}</ref> China in particular is Australia's main export and import partner by a wide margin.<ref name="AUCN">{{cite web |url=https://www.cnbc.com/2020/12/29/trade-war-with-china-australias-economy-after-covid-19-pandemic.html |title=Australia's growth may 'never return' to its pre-virus path after trade trouble with China, says economist |last=Tan |first=Weizhen |date=29 December 2020 |website=cnbc.com |publisher=[[CNBC]] |access-date=10 February 2021 |quote=China is by far Australia's largest trading partner, accounting for 39.4% of goods exports and 17.6% of services exports between 2019 and 2020, research firm [[Capital Economics]] said.}}</ref> Australia is a member of the [[Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation|APEC]], [[G-20 major economies|G20]], [[Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development|OECD]] and [[World Trade Organization|WTO]]. The country has also entered into [[Free trade agreements of Australia|free trade agreements]] with [[Association of Southeast Asian Nations|ASEAN]], Canada, Chile, China, South Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Peru, Japan, Singapore, Thailand and the United States.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.austrade.gov.au/Free-Trade-Agreements/default.aspx |title=International agreements on trade and investment |publisher=[[Austrade]] |access-date=11 September 2011 |archive-date=25 June 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130625022838/http://www.austrade.gov.au/Free-Trade-Agreements/default.aspx |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.customs.gov.au/site/page6010.asp |title=Free trade agreements – rules of origin |publisher=Australian Customs and Border Protection Services |access-date=8 February 2015}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/not-yet-in-force/pafta/Pages/peru-australia-fta.aspx|title = Peru-Australia Free Trade Agreement}}</ref> The [[Closer Economic Relations|ANZCERTA]] agreement with New Zealand has greatly increased integration with the [[economy of New Zealand]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.austrade.gov.au/ANZCERTA/default.aspx |title=Australia New Zealand Closer Economic Agreement (ANZCERTA) |publisher=Austrade.gov.au |date=1 January 2007 |access-date=11 September 2011 |archive-date=4 June 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080604022245/http://www.austrade.gov.au/ANZCERTA/default.aspx |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Australian Securities Exchange]] in [[Sydney]] is the 16th-largest [[stock exchange]] in the world in terms of domestic [[market capitalisation]]<ref name="dfat-top20">{{cite web|url=http://dfat.gov.au/trade/resources/Pages/australia-is-a-top-20-country.aspx|title=Australia is a top 20 country|date=18 May 2017|website=[[Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia)|Australian Government: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade]]|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170906224623/http://dfat.gov.au/trade/resources/Pages/australia-is-a-top-20-country.aspx|archivedate=6 September 2017|deadurl=yes|accessdate=6 September 2017}}</ref> and has the largest [[interest rate derivatives]] market in Asia.<ref>{{cite web|title=Corporate Overview|url=http://www.asx.com.au/about/corporate-overview.htm|website=[[Australian Securities Exchange]]|accessdate=6 September 2017}}</ref> Some of Australia's large companies include but are not limited to: [[Wesfarmers]], [[Woolworths Limited|Woolworths]], [[Rio Tinto Group]], [[BHP Billiton]], [[Commonwealth Bank]], [[National Australia Bank]], [[Westpac]], [[Australia and New Zealand Banking Group|ANZ]], [[Macquarie Group]], [[Telstra]] and [[Caltex]] Australia.<ref name="top10Corp-smh-2016">{{cite news|url=http://www.smh.com.au/business/retail/coles-owner-wesfarmers-moves-up-to-australias-top-company-by-revenue-20160306-gnc449.html|title=Australia's 10 Largest Companies |last=Hatch |first=Patrick |work=[[The Sydney Morning Herald]] |date=7 March 2016 |access-date=6 September 2017}}</ref> The currency of Australia and its territories is the Australian dollar which it shares with several Pacific nation states. |

|||

Australia is a member of the [[Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation|APEC]], [[G-20 major economies|G20]], [[Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development|OECD]] and [[World Trade Organization|WTO]]. The country has also entered into [[List of free trade agreements|free trade agreements]] with [[Association of Southeast Asian Nations|ASEAN]], Canada, Chile, China, South Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Peru, Japan, Singapore, Thailand and the United States.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.austrade.gov.au/Free-Trade-Agreements/default.aspx |title=International agreements on trade and investment |publisher=[[Austrade]] |accessdate=11 September 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.customs.gov.au/site/page6010.asp |title=Free trade agreements – rules of origin |publisher=Australian Customs and Border Protection Services |accessdate=8 February 2015}}</ref><ref>http://dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/not-yet-in-force/pafta/Pages/peru-australia-fta.aspx</ref> The [[Closer Economic Relations|ANZCERTA]] agreement with New Zealand has greatly increased integration with the [[economy of New Zealand]] and in 2011 there was a plan to form an Australasian Single Economic Market by 2015.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.austrade.gov.au/ANZCERTA/default.aspx |title=Australia New Zealand Closer Economic Agreement (ANZCERTA) |publisher=Austrade.gov.au |date=1 January 2007 |accessdate=11 September 2011}}</ref> |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

{{Main|Economic history of Australia}} |

{{Main|Economic history of Australia}} |

||

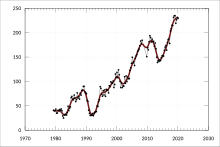

[[File:ABS-5206.0-AustralianNationalAccounts-NationalIncomeExpenditureProduct-KeyAggregatesAnalyticalSeriesAnnual-GdpPerCapita-ChainVolumeMeasures PercentageChanges-A2305033W.svg|thumb|left|Annual percentage growth in real (chain volume) [[GDP per capita]] since 1961]] |

|||

===20th century=== |

===20th century=== |

||

{{Main|Australian settlement}} |

{{Main|Australian settlement}} |

||

{{Missing information|section|something|date=February 2014}} |

|||

Australia's average GDP growth rate for the period 1901–2000 was 3.4% annually. As opposed to many neighbouring Southeast Asian countries, the process towards independence was relatively peaceful and thus did not have significant negative impact on the economy and standard of living.<ref>{{cite book|author=Baten, Jörg |title=A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present.|date=2016|publisher=Cambridge University Press|page=288|isbn=9781107507180}}</ref> Growth peaked during the 1920s, followed by the 1950s and the 1980s. By contrast, the late 1910s/early 1920s, the 1930s, the 1970s and early 1990s were marked by financial crises. |

Australia's average GDP growth rate for the period 1901–2000 was 3.4% annually. As opposed to many neighbouring Southeast Asian countries, the process towards independence was relatively peaceful and thus did not have significant negative impact on the economy and standard of living.<ref>{{cite book|author=Baten, Jörg |title=A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present.|date=2016|publisher=Cambridge University Press|page=288|isbn=9781107507180}}</ref> Growth peaked during the 1920s, followed by the 1950s and the 1980s. By contrast, the late 1910s/early 1920s, the 1930s, the 1970s and early 1990s were marked by financial crises. |

||

====Economic liberalisation==== |

====Economic liberalisation==== |

||

[[File:ABC Dollar Float.ogv|thumb|left|[[ABC News (Australia)|ABC News]] report, featuring [[Paul Keating]], on the first day of trading with a floating Australian dollar.]] |

|||

[[File:ABS-5206.0-AustralianNationalAccounts-NationalIncomeExpenditureProduct-KeyAggregatesAnalyticalSeriesAnnual-GdpPerCapita-ChainVolumeMeasures PercentageChanges-A2305033W.svg|thumb|left|Annual percentage growth in real (chain volume) [[GDP per capita]] since 1961]] |

|||

[[File:GDP per capita development in Australia and New Zealand.svg|thumb|Real GDP per capita development in Australia and New Zealand]] |

|||

From the early 1980s onwards, the Australian economy has undergone intermittent [[Economic liberalization|economic liberalisation]]. In 1983, under prime minister [[Bob Hawke]], but mainly driven by treasurer [[Paul Keating]], the Australian dollar was floated and financial [[deregulation]] was undertaken. |

From the early 1980s onwards, the Australian economy has undergone intermittent [[Economic liberalization|economic liberalisation]]. In 1983, under prime minister [[Bob Hawke]], but mainly driven by treasurer [[Paul Keating]], the Australian dollar was floated and financial [[deregulation]] was undertaken. |

||

====Early 1990s recession==== |

====Early 1990s recession==== |

||

{{Main|Early 1990s recession}} |

{{Main|Early 1990s recession|Early 1990s recession in Australia}} |

||

The early 1990s recession came swiftly after the [[Black Monday (1987)|Black Monday of October 1987]], as a result of a stock collapse of unprecedented size which caused the [[Dow Jones Industrial Average]] to fall by 22.6%. This collapse, larger than the [[Wall Street Crash of 1929|stock market crash of 1929]], was handled effectively by the global economy and the stock market began to quickly recover. But in North America, the lumbering [[Savings and loan association|savings and loans]] industry was facing decline, which eventually led to a [[savings and loan crisis]] which compromised the well-being of millions of US people. The following recession thus impacted the many countries closely linked to the |

The early 1990s recession came swiftly after the [[Black Monday (1987)|Black Monday of October 1987]], as a result of a stock collapse of unprecedented size which caused the [[Dow Jones Industrial Average]] to fall by 22.6%. This collapse, larger than the [[Wall Street Crash of 1929|stock market crash of 1929]], was handled effectively by the global economy and the stock market began to quickly recover. But in North America, the lumbering [[Savings and loan association|savings and loans]] industry was facing decline, which eventually led to a [[savings and loan crisis]] which compromised the well-being of millions of US people. The following recession thus impacted the many countries closely linked to the US, including Australia. Paul Keating, who was [[Treasurer of Australia|treasurer]] at the time, famously referred to it as "the recession that Australia had to have."<ref>[http://www.australianpolitics.com/executive/keating/keating-chronology.shtml Paul Keating – Chronology] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110926220100/http://www.australianpolitics.com/executive/keating/keating-chronology.shtml |date=26 September 2011}} at australianpolitics.com</ref> During the recession, GDP fell by 1.7%, employment by 3.4% and the unemployment rate rose to 10.8%.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.theage.com.au/news/business/the-real-reasons-why-it-was-the-1990s-recession-we-had-to-have/2006/12/01/1164777791623.html?page=3|title=The real reasons why it was the 1990s recession we had to have|work=[[The Age (newspaper)|The Age]]|date=2 December 2006|access-date=8 January 2014|archive-date=12 April 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140412054240/http://www.theage.com.au/news/business/the-real-reasons-why-it-was-the-1990s-recession-we-had-to-have/2006/12/01/1164777791623.html?page=3|url-status=dead}}</ref> However, the recession did assist in reducing long-term inflation rate expectations and Australia has maintained a low inflation environment since the 1990s to the present day. |

||

===Mining=== |

===Mining=== |

||

{{Main|Mining in Australia}} |

{{Main|Mining in Australia}} |

||

Mining has contributed to Australia's high level of economic growth, from the [[Australian gold rushes|gold rush]] in the 1840s to the present day. The opportunities for large profits in pastoralism and mining attracted considerable amounts of British capital, while expansion was supported by enormous government outlays for transport, communication, and urban infrastructures, which also depended heavily on British finance. As the economy expanded, large-scale immigration satisfied the growing demand for workers, especially after the end of convict transportation to the eastern mainland in 1840. Australia's mining operations secured continued economic growth and Western Australia itself benefited strongly from mining iron ore and gold from the 1960s and 1970s which |

Mining has contributed to Australia's high level of economic growth, from the [[Australian gold rushes|gold rush]] in the 1840s to the present day. The opportunities for large profits in pastoralism and mining attracted considerable amounts of British capital, while expansion was supported by enormous government outlays for transport, communication, and urban infrastructures, which also depended heavily on British finance. As the economy expanded, large-scale immigration satisfied the growing demand for workers, especially after the end of convict transportation to the eastern mainland in 1840. Australia's mining operations secured continued economic growth and Western Australia itself benefited strongly from mining iron ore and gold from the 1960s and 1970s which fuelled the rise of suburbanisation and consumerism in [[Perth]], the capital and most populous city of Western Australia, as well as other regional centres. |

||

===Global financial crisis=== |

===Global financial crisis=== |

||

{{Main|Great Recession|Great Recession in Oceania#Australia|Financial crisis of 2007–2008}} |

|||

{{Main|2007–2012 global financial crisis}} |

|||

{{further|Rudd Government (2007–10)}} |

{{further|Rudd Government (2007–10)}} |

||

The Australian government stimulus package ($11.8 billion) helped to prevent a recession.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Junankar|first1=P.|title=Australia: The Miracle Economy|journal=IZA Discussion Papers 7505, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA)|year=2013}}</ref> |

The Australian government stimulus package ($11.8 billion) helped to prevent a recession.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Junankar|first1=P.|title=Australia: The Miracle Economy|journal=IZA Discussion Papers 7505, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA)|year=2013}}</ref> |

||

The [[World Bank]] expected Australia's GDP growth rate to be 3.2% in 2011 and 3.8% in 2012.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://blogs.crikey.com.au/thestump/2011/01/13/world-bank-expects-australian-gdp-growth-of-3-2-in-2011-and-3-8-in-2012/ |title=World Bank expects Australian GDP growth of 3.2% in 2011 and 3.8% in 2012 | The Stump |publisher=Blogs.crikey.com.au |date=13 January 2011 | |

The [[World Bank]] expected Australia's GDP growth rate to be 3.2% in 2011 and 3.8% in 2012.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://blogs.crikey.com.au/thestump/2011/01/13/world-bank-expects-australian-gdp-growth-of-3-2-in-2011-and-3-8-in-2012/ |title=World Bank expects Australian GDP growth of 3.2% in 2011 and 3.8% in 2012 | The Stump |publisher=Blogs.crikey.com.au |date=13 January 2011 |access-date=24 July 2012 |archive-date=6 January 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120106083849/http://blogs.crikey.com.au/thestump/2011/01/13/world-bank-expects-australian-gdp-growth-of-3-2-in-2011-and-3-8-in-2012 |url-status=dead}}</ref> The economy expanded by 0.4% in the fourth quarter of 2011, and expanded by 1.3% in the first quarter of 2012.<ref>{{cite news| url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-17270827 |work=BBC News| title=Australia's economy expands 0.4% in the fourth-quarter | date=7 March 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://au.ibtimes.com/articles/349011/20120606/australia-posts-1-3-gdp-aussie-dollar.htm |title=Australia Posts 1.3% GDP; Aussie Dollar Soars|work=International Business Times |date=6 June 2012 |access-date=24 July 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120608081833/http://au.ibtimes.com/articles/349011/20120606/australia-posts-1-3-gdp-aussie-dollar.htm |archive-date=8 June 2012}}</ref> The growth rate was reported to be 4.3% year-on-year.<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/economics/gdp-growth-stronger-than-expected/story-e6frg926-1226385990494 | first=Adam | last=Creighton | title=GDP growth surges 1.3pc for first quarter | date=6 June 2012 | work=The Australian}}</ref> |

||

The [[International Monetary Fund]] in April 2012 predicted that Australia would be the best-performing major advanced economy in the world over the next two years; the Australian Government Department of the Treasury anticipated "forecast growth of 3.0% in 2012 and 3.5% in 2013",<ref name="aap-Apr2012-imf">{{cite web|agency=Australian Associated Press|url=http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/1643247/Australian-economy-to-outperform-the-world-IMF |title=Australian economy to outperform the world: IMF |website=[[Special Broadcasting Service]] |date=18 April 2012 |access-date=24 July 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120423083438/http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/1643247/Australian-economy-to-outperform-the-world-IMF|archive-date=2012-04-23}}</ref> the [[National Australia Bank]] in April 2012 cut its growth forecast for Australia to 2.9% from 3.2%.,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://au.ibtimes.com/articles/326290/20120411/nab-cuts-growth-forecast-australia-2-9.htm |title=NAB Cuts Australia's Growth Forecast to 2.9%|work=International Business Times |date=11 April 2012 |access-date=24 July 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120413191710/http://au.ibtimes.com/articles/326290/20120411/nab-cuts-growth-forecast-australia-2-9.htm |archive-date=13 April 2012}}</ref> and [[JPMorgan Chase|JP Morgan]] in May 2012 cut its growth forecast to 2.7% in calendar 2012 from a previous forecast of 3.0%, also its forecast for growth in 2013 to 3.0% from 3.3%.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.wsj.com/article/BT-CO-20120524-718299 |work=The Wall Street Journal |title=JP Morgan Cuts Australian 2012 GDP Forecast To 2.7% Vs 3.0% |date=24 May 2012 |access-date=13 March 2017 |archive-date=1 April 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190401083237/https://www.wsj.com/articles/BT-CO-20120524-718299 |url-status=dead}}</ref> [[Deutsche Bank]] in August 2012, and [[Société Générale]] in October 2012, warned that there is risk of recession in Australia in 2013.<ref>{{cite news| url=https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10000872396390444443504577602690621428420?mod=googlenews_wsj | work=The Wall Street Journal | first=James | last=Glynn | title=Deutsche Bank Warns of Australian Recession Risk | date=21 August 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.businessinsider.com/dylan-grice-australia-2012-10|title=Dylan Price predicts an Australian recession in 2013|work=Business Insider}}</ref> |

|||

While Australia's overall national economy grew, some non-mining states and Australia's non-mining economy experienced a recession.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://theconversation.com/national-economy-grows-but-some-non-mining-states-in-recession-12670 |title=National economy grows but some non-mining states in recession |work=The Conversation |access-date=22 March 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.couriermail.com.au/business/mining-punches-through-recession/story-fn7kjcme-1226320756339 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120416091909/http://www.couriermail.com.au/business/mining-punches-through-recession/story-fn7kjcme-1226320756339 |archive-date=16 April 2012 |title=Mining punches through recession |work=Courier Mail|author=Syvret, Paul |date=7 April 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-04-23/non-mining-states-27going-backwards27/3967622 |title=Non-mining states going backwards|publisher=ABC |access-date=22 March 2013}}</ref> |

|||

===2020 recession=== |

|||

The [[International Monetary Fund]] in April 2012 predicted that Australia would be the best-performing major advanced economy in the world over the next two years; the Australian Government Department of the Treasury anticipated "forecast growth of 3.0% in 2012 and 3.5% in 2013",<ref name="aap-Apr2012-imf">{{cite web|agency=Australian Associated Press|author-link=Australian Associated Press|url=http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/1643247/Australian-economy-to-outperform-the-world-IMF |title=Australian economy to outperform the world: IMF |website=[[Special Broadcasting Service]] |date=18 April 2012 |accessdate=24 July 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120423083438/http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/1643247/Australian-economy-to-outperform-the-world-IMF|archive-date=2012-04-23}}</ref> the [[National Australia Bank]] in April 2012 cut its growth forecast for Australia to 2.9% from 3.2%.,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://au.ibtimes.com/articles/326290/20120411/nab-cuts-growth-forecast-australia-2-9.htm |title=NAB Cuts Australia's Growth Forecast to 2.9%|work=International Business Times |date=11 April 2012 |accessdate=24 July 2012 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120413191710/http://au.ibtimes.com/articles/326290/20120411/nab-cuts-growth-forecast-australia-2-9.htm |archivedate=13 April 2012 }}</ref> and [[JPMorgan Chase|JP Morgan]] in May 2012 cut its growth forecast to 2.7% in calendar 2012 from a previous forecast of 3.0%, also its forecast for growth in 2013 to 3.0% from 3.3%.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.wsj.com/article/BT-CO-20120524-718299.html |work=The Wall Street Journal |title=JP Morgan Cuts Australian 2012 GDP Forecast To 2.7% Vs 3.0% }}{{dead link|date=June 2016|bot=medic}}{{cbignore|bot=medic}}</ref> [[Deutsche Bank]] in August 2012, and [[Société Générale]] in October 2012, warned that there is risk of recession in Australia in 2013.<ref>{{cite news| url=https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10000872396390444443504577602690621428420?mod=googlenews_wsj | work=The Wall Street Journal | first=James | last=Glynn | title=Deutsche Bank Warns of Australian Recession Risk | date=21 August 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.businessinsider.com/dylan-grice-australia-2012-10|title=Dylan Price predicts an Australian recession in 2013|work=Business Insider}}</ref> |

|||

{{Main|COVID-19 recession#Australia}} |

|||

In September 2020, it was confirmed that due to the effects of the [[COVID-19 pandemic in Australia|COVID-19 pandemic]], the Australian economy had gone into [[recession]] for the first time in nearly thirty years, as the country's [[Gross domestic product|GDP]] fell 7 per cent in the June 2020 quarter, following a 0.3 per cent drop in the March quarter.<ref name="nyt-recession">{{cite news |last1=Kwai |first1=Isabella |title=Australia's First Recession in Decades Signals Tougher Times to Come |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/02/business/australia-recession.html |access-date=22 September 2020 |work=The New York Times |date=2 September 2020}}</ref><ref name="afr-recession">{{cite news |title=Australia's recession in seven graphs |url=https://www.afr.com/policy/economy/australia-s-recession-in-five-graphs-20200902-p55rkw |access-date=22 September 2020 |work=Australian Financial Review |date=2 September 2020 |language=en}}</ref><ref name="abc-recession">{{cite news |title='Economy held together with duct tape' as Australia officially enters recession |url=https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-09-02/australian-recession-confirmed-as-economy-shrinks-in-june-qtr/12619950 |access-date=22 September 2020 |work=ABC News |date=2 September 2020 |language=en-AU}}</ref> It officially ended at the beginning of December 2020.<ref>{{Cite web|title=How Australia's GDP recovery compares to nations around the world|url=https://www.9news.com.au/world/australia-technically-not-in-a-recession-how-gdp-recovery-compares-to-the-rest-of-the-world/b1e11322-1d9b-42d0-8081-5d9f947b5181|access-date=2020-12-02|website=www.9news.com.au|date=2 December 2020}}</ref> |

|||

While Australia's overall national economy grew, some non-mining states and Australia's non-mining economy experienced a recession.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://theconversation.com/national-economy-grows-but-some-non-mining-states-in-recession-12670 |title=National economy grows but some non-mining states in recession |publisher=The Conversation |accessdate=22 March 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.couriermail.com.au/business/mining-punches-through-recession/story-fn7kjcme-1226320756339 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120416091909/http://www.couriermail.com.au/business/mining-punches-through-recession/story-fn7kjcme-1226320756339 |archivedate=16 April 2012 |title=Mining punches through recession |work=Courier Mail|author=Syvret, Paul |date=7 April 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-04-23/non-mining-states-27going-backwards27/3967622 |title=Non-mining states going backwards|publisher=ABC |accessdate=22 March 2013}}</ref> |

|||

== Data == |

== Data == |

||

{{Update|date=October 2024}} |

|||

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2017. Inflation under 2 % is in green.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2018/01/weodata/weorept.aspx?sy=1980&ey=2023&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=193&s=NGDP_RPCH,PPPGDP,PPPPC,PCPIPCH,LUR,GGXWDG_NGDP&grp=0&a=&pr.x=88&pr.y=12|title=Report for Selected Countries and Subjects|website=www.imf.org|language=en-US|access-date=2018-09-11}}</ref> |

|||

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2023 (with IMF staff estimates in 2024–2027). Inflation under 5% is in green.<ref name="weo-database-2022-october-gdp-inflation-unemployment-debt">{{cite web | url=https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2022/October/weo-report?c=193,&s=NGDP_RPCH,NGDPD,PPPGDP,NGDPDPC,PPPPC,PCPIPCH,LUR,GGXWDG_NGDP,&sy=1980&ey=2027&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1 | title=World Economic Outlook database: October 2022 |publisher=[[International Monetary Fund]] |access-date=2022-10-21}}</ref> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" |

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" |

||

!Year |

!Year |

||

!GDP |

|||

!GDP<br /><small>(in Bil. US$ PPP)</small> |

|||

<small>(in bil. US$PPP)</small> |

|||

!GDP per capita |

|||

!GDP growth<br /><small>(real)</small> |

|||

<small>(in US$PPP)</small> |

|||

!GDP |

|||

!Unemployment <br /><small>(in Percent)</small> |

|||

<small>(in bil. US$nominal)</small> |

|||

!GDP per capita |

|||

<small>(in US$ nominal)</small> |

|||

!GDP growth |

|||

<small>(real)</small> |

|||

!Inflation rate |

|||

<small>(in percent)</small> |

|||

!Unemployment |

|||

<small>(in percent)</small> |

|||

!Government debt |

|||

<small>(in % of GDP)</small> |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|1980 |

|1980 |

||

|155. |

|155.4 |

||

|10, |

|10,498.0 |

||

|162.8 |

|||

|{{Increase}}2.9 % |

|||

|11,000.1 |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}10.1 % |

|||

|{{Increase}}2.9% |

|||

|6.1 % |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}10.1% |

|||

|6.1% |

|||

|n/a |

|n/a |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1981 |

|1981 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}177.1 |

||

|{{Increase}}11, |

|{{Increase}}11,776.5 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}188.3 |

||

|{{Increase}}12,520.0 |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}9.5 % |

|||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}4.1% |

||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}9.5% |

|||

|{{DecreasePositive}}5.8% |

|||

|n/a |

|n/a |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1982 |

|1982 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}188.2 |

||

|{{Increase}}12. |

|{{Increase}}12,307.7 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Decrease}}186.9 |

||

|{{Decrease}}12,226.6 |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}11.4 % |

|||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}0.1% |

||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}11.4% |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}7.2% |

|||

|n/a |

|n/a |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1983 |

|1983 |

||

|{{Increase}}194. |

|{{Increase}}194.6 |

||

|{{Increase}}12, |

|{{Increase}}12,569.1 |

||

|{{Decrease}} |

|{{Decrease}}179.4 |

||

|{{Decrease}}11,584.2 |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}10.0 % |

|||

|{{ |

|{{Decrease}}-0.5% |

||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}10.0% |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}10.0% |

|||

|n/a |

|n/a |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1984 |

|1984 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}214.4 |

||

|{{Increase}}13, |

|{{Increase}}13,678.0 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}197.0 |

||

|{{Increase}}12,566.6 |

|||

|{{increaseNegative}}4.0 % |

|||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}6.3% |

||

|{{Increase}}4.0% |

|||

|{{DecreasePositive}}9.0% |

|||

|n/a |

|n/a |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1985 |

|1985 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}233.3 |

||

|{{Increase}}14, |

|{{Increase}}14,671.4 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Decrease}}174.3 |

||

|{{Decrease}}10,960.2 |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}4.0 % |

|||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}5.5% |

||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}6.7% |

|||

|{{DecreasePositive}}8.3% |

|||

|n/a |

|n/a |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1986 |

|1986 |

||

|{{Increase}}243. |

|{{Increase}}243.8 |

||

|{{Increase}}15, |

|{{Increase}}15,106.9 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}181.4 |

||

|{{Increase}}11,237.7 |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}9.1 % |

|||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}2.4% |

||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}9.1% |

|||

|{{DecreasePositive}}8.1% |

|||

|n/a |

|n/a |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1987 |

|1987 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}262.1 |

||

|{{Increase}}15, |

|{{Increase}}15,984.6 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}213.0 |

||

|{{Increase}}12,989.9 |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}8.5 % |

|||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}4.9% |

||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}8.5% |

|||

|{{Steady}}8.1% |

|||

|n/a |

|n/a |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1988 |

|1988 |

||

|{{Increase}}282. |

|{{Increase}}282.8 |

||

|{{Increase}}16, |

|{{Increase}}16,949.7 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}270.9 |

||

|{{Increase}}16,235.1 |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}7.3 % |

|||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}4.3% |

||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}7.3% |

|||

|{{DecreasePositive}}7.2% |

|||

|n/a |

|n/a |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|1989 |

|1989 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}307.6 |

||

|{{Increase}}18, |

|{{Increase}}18,159.0 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}308.1 |

||

|{{Increase}}18,191.4 |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}7.6 % |

|||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}4.6% |

||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}7.6% |

|||

|17.1 % |

|||

|{{DecreasePositive}}6.1% |

|||

|17.0% |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|1990 |

|1990 |

||

|{{Increase}}323. |

|{{Increase}}323.8 |

||

|{{Increase}}18, |

|{{Increase}}18,859.9 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}323.8 |

||

|{{Increase}}18,859.6 |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}7.2 % |

|||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}1.5% |

||

|{{ |

|{{IncreaseNegative}}7.2% |

||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}6.9% |

|||

|{{DecreasePositive}}16.4% |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|1991 |

|1991 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}331.4 |

||

|{{Increase}}19, |

|{{Increase}}19,070.9 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}324.2 |

||

|{{Decrease}}18,656.5 |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}3.3 % |

|||

|{{ |

|{{Decrease}}-1.0% |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}3.3% |

||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}9.6% |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}21.6% |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|1992 |

|1992 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}347.7 |

||

|{{Increase}}19, |

|{{Increase}}19,802.5 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Decrease}}317.9 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Decrease}}18,106.7 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}2.6% |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}1.0% |

||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}10.7% |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}27.6% |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|1993 |

|1993 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}369.9 |

||

|{{Increase}}20, |

|{{Increase}}20,877.2 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Decrease}}309.2 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Decrease}}17,447.6 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}3.9% |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}1.8% |

||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}10.9% |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}30.7% |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|1994 |

|1994 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}396.1 |

||

|{{Increase}}22, |

|{{Increase}}22,138.3 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}353.2 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}19,736.3 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}4.8% |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}1.9% |

||

|{{DecreasePositive}}9.7% |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}31.7% |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|1995 |

|1995 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}416.4 |

||

|{{Increase}}22, |

|{{Increase}}22,980.0 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}378.9 |

||

|{{Increase}}20,908.4 |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}4.6 % |

|||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}3.0% |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}4.6% |

||

|{{DecreasePositive}}8.5% |

|||

|{{DecreasePositive}}31.2% |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|1996 |

|1996 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}441.1 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}24,064.7 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}424.4 |

||

|{{Increase}}23,153.8 |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}2.7 % |

|||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}4.0% |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}2.7% |

||

|{{Steady}}8.5% |

|||

|{{DecreasePositive}}29.4% |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|1997 |

|1997 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}469.4 |

||

|{{Increase}}25, |

|{{Increase}}25,357.9 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}426.2 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Decrease}}23,023.6 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}4.6% |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}0.2% |

||

|{{DecreasePositive}}8.4% |

|||

|{{DecreasePositive}}25.9% |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|1998 |

|1998 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}496.7 |

||

|{{Increase}}26, |

|{{Increase}}26,555.0 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Decrease}}381.1 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Decrease}}20,374.7 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}4.7% |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}0.9% |

||

|{{DecreasePositive}}7.7% |

|||

|{{DecreasePositive}}23.7% |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|1999 |

|1999 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}525.6 |

||

|{{Increase}}27, |

|{{Increase}}27,782.8 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}411.5 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}21,748.0 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}4.3% |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}1.4% |

||

|{{DecreasePositive}}6.9% |

|||

|{{DecreasePositive}}22.6% |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|2000 |

|2000 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}554.2 |

||

|{{Increase}}28, |

|{{Increase}}28,953.2 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Decrease}}399.7 |

||

|{{Decrease}}20,879.2 |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}4.5 % |

|||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}3.1% |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}4.5% |

||

|{{DecreasePositive}}6.3% |

|||

|{{DecreasePositive}}19.5% |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|2001 |

|2001 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}581.8 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}30,010.1 |

||

|{{ |

|{{Decrease}}377.5 |

||

|{{Decrease}}19,473.7 |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}4.4 % |

|||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}2.7% |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}4.4% |

||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}6.8% |

|||

|{{DecreasePositive}}17.1% |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|2002 |

|2002 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}615.5 |

||

|{{Increase}}31, |

|{{Increase}}31,393.8 |

||

|{{Increase}} |

|{{Increase}}425.1 |

||

|{{Increase}}21,683.5 |

|||

|{{IncreaseNegative}}3.0 % |

|||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}4.2% |

||

|{{ |

|{{Increase}}3.0% |

||

|{{DecreasePositive}}6.4% |

|||