University of Mississippi: Difference between revisions

Finaskundil (talk | contribs) |

rankings |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Public university near Oxford, Mississippi, US}} |

|||

{{redirect|Ole Miss|the University of Mississippi athletics program|Ole Miss Rebels}} |

|||

{{Good article}} |

|||

{{distinguish|Mississippi State University}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date= |

{{Use mdy dates|date=July 2021}} |

||

{{Infobox university |

{{Infobox university |

||

| name |

| name = University of Mississippi |

||

| |

| image = University of Mississippi seal.svg |

||

| image_upright = 0.72 |

|||

| image_size = 150 |

|||

| established = {{start date and age|February 24, 1844}}<!--Please do NOT change this date. 1848 is NOT correct.--> |

|||

| established = 1848 |

|||

| motto = ''Pro scientia et sapientia'' ([[Latin]]) |

| motto = ''Pro scientia et sapientia'' ([[Latin language|Latin]]) |

||

| mottoeng = For knowledge and wisdom |

| mottoeng = "For knowledge and wisdom" |

||

| logo = University of Mississippi logo.svg |

|||

| type = [[State university system|Public]]<br />[[Flagship]]<br />[[Sea-grant]]<br />[[Space-grant]] |

|||

| logo_upright = 1.0 |

|||

| academic_affiliations = [[Oak Ridge Associated Universities|ORAU]]<br />[[Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities|APLU]]<br />[[Southeastern Universities Research Association|SURA]] |

|||

| type = [[Public university|Public]] [[research university]] |

|||

| chancellor = Larry Sparks (interim)<ref>{{cite web|url=https://news.olemiss.edu/ihl-board-trustees-appoints-um-vice-chancellor-serve-interim-chancellor/|title=IHL: Board of Trustees appoints UM Vice Chancellor to serve as Interim Chancellor|website=University of Mississippi News}}</ref> |

|||

| chancellor = [[Glenn Boyce]] |

|||

| city = [[University, Mississippi|University]] |

|||

| provost = Noel E. Wilkin |

|||

| state = [[Mississippi]] |

|||

| city = [[Oxford, Mississippi|Oxford]] |

|||

| country = U.S. |

|||

| state = [[Mississippi]] |

|||

| coor = {{Coord|34.365|N|89.538|W|region:US-MS_type:edu_dim:2000|display=inline,title}} |

|||

| campus = Remote town<ref>{{cite web |url=https://nces.ed.gov/collegenavigator/?q=Mississippi&s=all&id=176017 |title=IPEDS-University of Mississippi |access-date=December 30, 2023 |archive-date=December 30, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231230172011/https://nces.ed.gov/collegenavigator/?q=Mississippi&s=all&id=176017 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

| campus = [[Rural]] (small [[college town]]) 2,000+ acres |

|||

| campus_size = {{cvt|3497|acre|km2}} |

|||

| faculty = 871 |

|||

| students = 24,710 (for 2023-2024 year)<ref>{{cite web |url=https://irep.olemiss.edu/fall-2023-2024-enrollment/ |title=Office of Institutional Research, Effectiveness, and Planning | Fall 2023-2024 Enrollment }}</ref> |

|||

| students = 23,258 (fall 2017)<ref name="factbook1"/> |

|||

| endowment = $840 million (2023) |

|||

| endowment = $715 million (2018)<ref>{{cite web|url=https://news.olemiss.edu/university-endowment-builds-time-high-715-million/ |title=University Endowment Builds to All-time High of $715 Million - Ole Miss News|website=Ole Miss News}}</ref> |

|||

| budget = $670 million (2024)<ref>https://adminfinance.olemiss.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/74/2023/11/Revenues-and-Expenditures.pdf {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240213220741/https://adminfinance.olemiss.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/74/2023/11/Revenues-and-Expenditures.pdf |date=February 13, 2024 }} {{Bare URL PDF|date=August 2024 }}</ref> |

|||

| budget = $2.448 billion (2016)<ref>{{cite web|url=https://olemiss.edu/aboutum/facts.html |title= About UM: Facts - University of Mississippi|website=The University of Mississippi Facts & Statistics}}</ref> |

|||

| |

| sports_nickname = [[Ole Miss Rebels|Rebels]] |

||

| sporting_affiliations = [[NCAA Division I]] – [[Southeastern Conference|SEC]] |

| sporting_affiliations = {{hlist|[[NCAA Division I]] [[NCAA Division I Football Bowl Subdivision|FBS]] – [[Southeastern Conference|SEC]]|[[Patriot Rifle Conference|PRC]]}} |

||

| website = {{URL|www.olemiss.edu|olemiss.edu}} |

|||

| colors = Cardinal red, navy blue<ref>{{cite web|title=Licensing FAQ's|url=http://csm.olemiss.edu/licensing/|publisher=Department of Licensing–University of Mississippi|accessdate=July 11, 2016}}</ref><br>{{color box|#C8102E}} {{color box|#13294B}} |

|||

| website = {{url|www.olemiss.edu}} |

|||

| logo = University of Mississippi logo.svg |

|||

| logo_size = 250 |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''University of Mississippi''' ([[Epithet|byname]] '''Ole Miss''') is a [[Public university|public]] [[research university]] in [[Oxford, Mississippi]], United States, with a [[University of Mississippi Medical Center|medical center]] in [[Jackson, Mississippi|Jackson]]. It is Mississippi's oldest public university and is the state's largest by enrollment.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Journal |first=BLAKE ALSUP Daily |title=MSU, USM see increased enrollment as state numbers decline |url=https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/university-of-mississippi-2440 |access-date=January 15, 2022 |website=Daily Journal |language=en |archive-date=January 15, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220115023522/https://www.djournal.com/news/education/msu-usm-see-increased-enrollment-as-state-numbers-decline/article_91c6b17e-ce1d-58e8-8402-d937ecdf7613.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

'''The University of Mississippi''' (colloquially known as '''Ole Miss''') is a [[Public university|public]] [[research university]] in [[Oxford, Mississippi]]. Including the [[University of Mississippi Medical Center]] in [[Jackson, Mississippi|Jackson]], it is the state's largest university by enrollment.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://irep.olemiss.edu/fall-2017-2018-enrollment/|title=Office of Institutional Research, Effectiveness, and Planning {{!}} fall-2017-2018-enrollment|website=irep.olemiss.edu|language=en-US|access-date=June 27, 2018}}</ref> The university was chartered by the [[Mississippi Legislature]] on February 24, 1844, and four years later admitted its first enrollment of 80 students. The university is classified as an "R1: Doctoral University—Very High Research Activity" by the [[Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education|Carnegie Foundation]] and has an annual [[Research|research and development]] budget of $121.6 million.<ref name="Washington Post 2016">{{cite web | title=In new sorting of colleges, Dartmouth falls out of an exclusive group | website=Washington Post | date=February 4, 2016 | url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/grade-point/wp/2016/02/04/in-new-sorting-of-colleges-dartmouth-falls-out-of-an-exclusive-group/ | access-date=June 9, 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://carnegieclassifications.iu.edu/lookup/view_institution.php?unit_id=176017|title=The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education|publisher=Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research|date=2017|accessdate=November 3, 2017}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/profiles/site?print=true&method=rankingBySource&ds=herd|title=Rankings by total R&D expenditures|last=National Science Foundation|first=|date=|website=|access-date=|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180820082334/https://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/profiles/site?print=true&method=rankingBySource&ds=herd|archive-date=August 20, 2018|dead-url=yes|df=mdy-all}}</ref> The university ranked 145 in the 2018 edition of the US News Rankings of Best National Universities.<ref name="Profile, Rankings and Data 2017">{{cite web | title=How Does University of Mississippi Rank Among America's Best Colleges? | website=Profile, Rankings and Data | date=October 3, 2017 | url=https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/university-of-mississippi-2440 | access-date=June 9, 2018}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Mississippi Legislature]] chartered the university on February 24, 1844, and in 1848 admitted its first 80 students. During the [[American Civil War|Civil War]], the university operated as a [[Confederate States of America|Confederate]] hospital and narrowly avoided destruction by [[Ulysses S. Grant]]'s forces. In 1962, during the [[civil rights movement]], [[Ole Miss riot of 1962|a race riot]] occurred on campus when [[Racial segregation in the United States|segregationists]] tried to prevent the enrollment of African American student [[James Meredith]]. The university has since taken measures to improve its image. The university is closely associated with writer [[William Faulkner]] and owns and manages his former Oxford home [[Rowan Oak]], which with other on-campus sites [[Barnard Observatory]] and [[Lyceum–The Circle Historic District]], is listed on the [[National Register of Historic Places]]. |

|||

Across all its campuses, the university comprises some 23,258 students.<ref name="factbook1">{{Cite web|url=https://news.olemiss.edu/um-welcomes-new-returning-students-fall-semester/|title=UM Welcomes New and Returning Students for Fall Semester|last=Ole Miss News|first=|date=|website=|access-date=}}</ref> In addition to the main campus in Oxford and the medical school in Jackson, the university also has campuses in [[Tupelo, Mississippi|Tupelo]], [[Booneville, Mississippi|Booneville]], [[Grenada, Mississippi|Grenada]], and [[Southaven, Mississippi|Southaven]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.outreach.olemiss.edu/regional/|title=The University of Mississippi Regional Campuses|website=www.outreach.olemiss.edu|access-date=June 27, 2018}}</ref> About 55 percent of its undergraduates and 60 percent overall come from Mississippi, and 23 percent are minorities; international students respectively represent 90 different nations.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://olemiss.edu/aboutum/facts.html|title=The University of Mississippi Facts and Statistics|publisher=University of Mississippi|date=January 15, 2016}}</ref> It is one of the 33 colleges and universities participating in the [[National Sea Grant Program]] and a participant in the [[National Space Grant College and Fellowship Program]].<ref name="NASA 2015">{{cite web | title=National Space Grant College and Fellowship Program | website=NASA | date=July 28, 2015 | url=http://www.nasa.gov/offices/education/programs/national/spacegrant/home/index.html | access-date=June 9, 2018}}</ref> |

|||

Ole Miss is [[Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education|classified]] as "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity". It is one of 33 institutions participating in the National Sea Grant Program and also participates in the National Space Grant College and Fellowship Program. Its research efforts include the National Center for Physics Acoustics, the National Center for Natural Products Research, and the Mississippi Center for Supercomputing Research. The university operates the country's only federally contracted [[Food and Drug Administration]] (FDA)-approved cannabis facility. It also operates interdisciplinary institutes such as the [[Center for the Study of Southern Culture]]. Its athletic teams compete as the [[Ole Miss Rebels]] in the [[National Collegiate Athletic Association]]'s (NCAA) [[NCAA Division I|Division I]] [[Southeastern Conference]]. |

|||

Ole Miss was a center of activity during the [[Civil rights movement|American civil rights movement]] when a [[Ole Miss riot of 1962|race riot]] erupted in 1962 following the attempted admission of [[James Meredith]], an [[African Americans|African-American]], to the [[Racial segregation in the United States|segregated]] campus.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.npr.org/2012/10/01/161573289/integrating-ole-miss-a-transformative-deadly-riot|title=Integrating Ole Miss: A Transformative, Deadly Riot|work=NPR.org|access-date=2018-07-09|language=en}}</ref> While the university was successfully integrated that year, the use of [[Confederate States of America|Confederate]] symbols and motifs has remained a controversial aspect of the school's identity and culture.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/09/us/ole-miss-confederacy.html|title=Ole Miss Edges Out of Its Confederate Shadow, Gingerly|access-date=2018-07-09|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.npr.org/2014/10/25/358871799/ole-miss-debates-campus-traditions-with-confederate-roots|title='Ole Miss' Debates Campus Traditions With Confederate Roots|work=NPR.org|access-date=2018-07-09|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/confederacy-still-haunts-campus-ole-miss-n820881|title=The Confederacy still haunts the campus of Ole Miss|work=NBC News|access-date=2018-07-09|language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://wreg.com/2017/08/16/ole-miss-to-change-building-name-add-plaques-to-give-confederate-context/|title=Ole Miss to change building name, add plaques to give Confederate context|date=2017-08-16|work=WREG.com|access-date=2018-07-09|language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://a.espncdn.com/page2/s/caple/030916.html|title=ESPN.com - Page2 - Mississippi's mascot mess|website=a.espncdn.com|access-date=2018-07-09}}</ref> In response the university has attempted to take proactive measures to rebrand its image, including effectively banning [[Modern display of the Confederate flag|the display of Confederate flags]] in [[Vaught–Hemingway Stadium|Vaught-Hemingway Stadium]] in 1997, officially abandoning the [[Colonel Reb]] mascot in 2003, and removing "[[Dixie (song)|Dixie]]" from the [[The Pride of the South|Pride of the South]] marching band's repertoire in 2016.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.cnn.com/US/9710/25/ole.miss/|title=CNN - Flag ban tugs on Ole Miss traditions - October 25, 1997|website=www.cnn.com|access-date=2018-07-09}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/20/us/20mascot.html|title=Ole Miss Shelves Mascot Fraught With Baggage|last=Brown|first=Robbie|access-date=2018-07-09|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.msnewsnow.com/Global/story.asp?S=1478331&nav=2CSfITZj|title=Ole Miss is Without a Mascot|access-date=2018-07-09|language=en|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180709153623/http://www.msnewsnow.com/Global/story.asp?S=1478331&nav=2CSfITZj|archive-date=July 9, 2018|dead-url=yes|df=mdy-all}}</ref> In 2018, following a racially charged rant on social media by an alum and academic building namesake, former Chancellor [[Jeffrey Vitter]] reaffirmed the university's commitment to "honest and open dialogue about its history", and in making its campuses "more welcoming and inclusive".<ref name="Ryback 2017">{{cite web | last=Ryback | first=Timothy W. | title=What Ole Miss Can Teach Universities About Grappling With Their Pasts | website=The Atlantic | date=September 19, 2017 | url=https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/09/what-ole-miss-can-teach-universities-about-grappling-with-their-pasts/540324/ | access-date=June 12, 2018}}</ref> |

|||

The [[List of University of Mississippi alumni|university's alumni, faculty, and affiliates]] include 27 [[Rhodes Scholars]], 10 [[Governor (United States)|governors]], 5 [[United States Senate|US senators]], a [[head of government]], and a [[Nobel Prize Laureate]]. Other alumni have received accolades in the arts such as [[Emmy Awards]], [[Grammy Awards]], and [[Pulitzer Prizes]]. Its [[University of Mississippi Medical Center|medical center]] performed the first human lung transplant and [[Xenotransplantation|animal-to-human heart transplant]]. |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

{{Main|History of the University of Mississippi}} |

|||

===Founding |

===Founding and early history=== |

||

{{multiple image |

|||

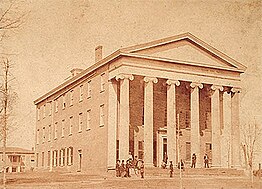

[[File:Olemisslyceum.jpg|thumb|right|The Lyceum, [[William Nichols (architect)|William Nichols]], architect (1848)]] |

|||

| align = left |

|||

[[File:The Dead House, University of Mississippi (circa 1937).jpg|thumb|right|The "Dead House" was built before the Civil War and was used as a morgue during the war. Bodies were carried from the Dead House across campus to the Civil War Cemetery, which contains more than 430 graves. The building was demolished in 1958, and Farley Hall--which contains the Meek School of Journalism and New Media--was erected in its place.<ref>{{cite web |last=Steube|first=Christina|title=Some Older Areas of Campus Have a Spooky Past|publisher=The University of Mississippi|date=October 31, 2014 |url=http://news.olemiss.edu/haunted-history/}}</ref>]] |

|||

| total_width = 400 |

|||

| image1 = Frederick Augustus Porter Bernard cph.3b31295.jpg |

|||

| alt1 = Frederick A. P. Barnard, a spectacled and bearded man |

|||

| image2 = 1861 Lyceum.jpg |

|||

| alt2 = The Lyceum in 1861 |

|||

| footer = [[Frederick Augustus Porter Barnard|Frederick A. P. Barnard]], the last [[Antebellum South|antebellum]] chancellor, and the [[Lyceum (Mississippi)|Lyceum]] in 1861 |

|||

}} |

|||

The [[Mississippi Legislature]] chartered the University of Mississippi on February 24, 1844<!---DO NOT CHANGE THIS DATE!!!-->.<ref name="Fowler 1941, p. 213">[[#Fowler|Fowler (1941)]], p. 213.</ref> Planners selected an isolated, rural site in [[Oxford, Mississippi|Oxford]] as a "sylvan exile" that would foster academic studies and focus.<ref name="cohodas5">[[#Cohodas|Cohodas (1997)]], p. 5.</ref> In 1845, residents of [[Lafayette County, Mississippi|Lafayette County]] donated land west of Oxford for the campus and the following year, architect [[William Nichols (architect)|William Nichols]] oversaw construction of an academic building called the [[The Lyceum (Mississippi)|Lyceum]], two dormitories, and faculty residences.<ref name="Fowler 1941, p. 213"/> On November 6, 1848, the university, offering a [[Classics|classical]] curriculum, opened to its first class of 80 students,<ref name="cohodas5"/><ref name="history"/> most of whom were children of elite slaveholders, all of whom were white, and all but one of whom were from Mississippi.<ref name="cohodas5"/><ref>{{cite news|last=Andrews|first=Becca|date=July 1, 2020|title=The Racism of "Ole Miss" Is Hiding in Plain Sight|url=https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2020/07/racism-university-mississippi-nickname-ole-miss-confederate-history-elma-meeks/|work=Mother Jones|access-date=August 1, 2021|archive-date=July 9, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210709002552/https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2020/07/racism-university-mississippi-nickname-ole-miss-confederate-history-elma-meeks/|url-status=live}}</ref> For 23 years, the university was Mississippi's only public institution of higher learning<ref>{{cite web|title=History|url=http://www.olemiss.edu/info/history.html|publisher=University of Mississippi|access-date=December 14, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130404053703/http://www.olemiss.edu/info/history.html|archive-date=April 4, 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref> and for 110 years, its only comprehensive university.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.forbes.com/colleges/university-of-mississippi-main-campus/?sh=1210fd8365a7|title=University of Mississippi Main Campus|website=Forbes|access-date=June 28, 2021|archive-date=June 29, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210629020429/https://www.forbes.com/colleges/university-of-mississippi-main-campus/?sh=1210fd8365a7|url-status=live}}</ref> In 1854, the [[University of Mississippi School of Law]] was established, becoming the fourth state-supported law school in the United States.<ref name="law">{{cite web|url=https://law.olemiss.edu/about/history/|title=History|website=School of Law|publisher=University of Mississippi|access-date=July 4, 2021|archive-date=July 3, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210703014433/https://law.olemiss.edu/about/history/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

The Mississippi Legislature chartered the University of Mississippi on February 24, 1844. The university opened its doors to its first class of 80 students four years later in 1848. For 23 years, the university was Mississippi's only public institution of higher learning, and for 110 years it was the state's only comprehensive university.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.olemiss.edu/info/history.html |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130404053703/http://www.olemiss.edu/info/history.html|archivedate=April 4, 2013|title=The University of Mississippi - History|publisher=Olemiss.edu|accessdate=December 14, 2012}}</ref> Politician [[Pryor Lea]] was a founding trustee.<ref name="nrhpdocleasprings">{{cite web|url={{NRHP url|id=75001754}}|title=National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Lea Springs |publisher=[[National Park Service]]|author= |date= |accessdate=June 14, 2018}} With {{NRHP url|id=75001754|photos=y|title=accompanying pictures|quote=Because of his strong interest in education it is not surprising that he was one of the co-founders of the University of Mississippi and member of its first board of trustees.}}</ref> |

|||

Early president [[Frederick Augustus Porter Barnard|Frederick A. P. Barnard]] sought to increase the university's stature, placing him in conflict with the more-conservative board of trustees.<ref name="Cohodas 1997 pp. 6">[[#Cohodas|Cohodas (1997)]], pp. 6–7.</ref> The only result of Barnard's hundred-page 1858 report to the board was the university head's title being changed to "chancellor".<ref>[[#Cohodas|Cohodas (1997)]], p. 7.</ref> Barnard was a Massachusetts-born graduate of [[Yale University]]; his northern background and [[Union (American Civil War)|Union]] sympathies made his position contentious—a student assaulted his slave and the state legislature investigated him.<ref name="Cohodas 1997 pp. 6"/> Following the election of US President [[Abraham Lincoln]] in 1860, Mississippi became the second state to secede; the university's mathematics professor [[Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar]] drafted the [[Mississippi Secession Ordinance|articles of secession]].<ref>[[#Cohodas|Cohodas (1997)]], p. 8.</ref> Students organized into a military company called the "[[University Greys]]", which became Company A, [[11th Mississippi Infantry Regiment]] in the [[Confederate States Army]].<ref name="cohodas9">[[#Cohodas|Cohodas (1997)]], p. 9.</ref> Within a month of the [[American Civil War|Civil War]]'s outbreak, only five students remained at the university, and by late 1861, it was closed. In its final action, the board of trustees awarded Barnard a [[Doctor of Divinity|doctorate of divinity]].<ref name="cohodas9"/> |

|||

When the university opened, the campus consisted of six buildings: two dormitories, two faculty houses, a steward's hall, and the [[Lyceum-The Circle Historic District|Lyceum]] at the center. Constructed from 1846 to 1848, the Lyceum is the oldest building on campus. Originally, the Lyceum housed all of the classrooms and faculty offices of the university. The building's north and south wings were added in 1903, and the Class of 1927 donated the clock above the eastern portico. The Lyceum is now the home of the university's administration offices. The columned facade of the Lyceum is represented on the official crest of the university, along with the date of establishment.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.olemiss.edu/tours/lm-text.html|title=Virtual Tours - The University of Mississippi|publisher=Olemiss.edu|date=October 1, 2006|accessdate=December 14, 2012}}</ref> |

|||

Within six months, the campus had been converted into a Confederate hospital; the Lyceum was used as the hospital and a building that had stood on the modern-day site of Farley Hall operated as its morgue.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://news.olemiss.edu/haunted-history/ |title=Haunted History |date=October 31, 2014 |access-date=September 9, 2022 |archive-date=April 24, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210424203125/https://news.olemiss.edu/haunted-history/ |url-status=live }}</ref> In November 1862, the campus was evacuated as General [[Ulysses S. Grant]]'s [[Union Army|Union forces]] approached. Although Kansan troops destroyed much of the medical equipment, a lone remaining professor persuaded Grant against burning the campus.<ref>[[#Cohodas|Cohodas (1997)]], p. 10.</ref>{{efn|group=note|Chancellor Barnard's friendship with General [[William Tecumseh Sherman]] may have also helped save the campus.<ref>[[#Sansing|Sansing (1999)]], p. 112.</ref>}} Grant's forces left after three weeks and the campus returned to being a Confederate hospital. Over the war's course, more than 700 soldiers were buried on campus.<ref name="cohodas11">[[#Cohodas|Cohodas (1997)]], p. 11.</ref> |

|||

In 1854, the university established the fourth state-supported, public law school in the United States, and also began offering engineering education.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.engineering.olemiss.edu/about/index.html|title=School of Engineering • About Us|publisher=Engineering.olemiss.edu|accessdate=December 14, 2012}}</ref> |

|||

===Post-war=== |

|||

With the outbreak of the [[American Civil War|Civil War]] in 1861, classes were interrupted when almost the entire student body (135 out of 139 students) from the University of Mississippi enlisted in the [[Confederate States of America|Confederate]] army, forming an infantry group nicknamed the University Greys.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.civilwar.org/education/civil-war-casualties.html?referrer=https://www.google.com/|title=Civil War Casualties|accessdate=April 30, 2016}}</ref> However, all 135 students were killed during the war, a 100% casualty rate. Most died during the battles of Gettysburg and Vicksburg. |

|||

[[File:SarahMcGeheeIsom.tif|thumb|upright|alt=A woman in collegiate garb|The University of Mississippi was the first college in the Southeast to hire a female faculty member: [[Sarah McGehee Isom]] in 1885.]] |

|||

The University of Mississippi reopened in October 1865.<ref name="cohodas11"/> To avoid rejecting veterans, the university lowered admission standards and decreased costs by eliminating tuition and allowing students to live off-campus.<ref name="history"/> The student body remained entirely white: in 1870 the chancellor declared that he and the entire faculty would resign rather than admit "negro" students.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Roland |first1=Dunbar |title=The Official and Statistical Register of the State of Mississippi, Volume 4 |date=December 11, 2023 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pLC0kgvJJG4C&dq=jess+stockstill+picayune&pg=PA912 |access-date=August 4, 2023 |archive-date=November 10, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231110200610/https://books.google.com/books?id=pLC0kgvJJG4C&dq=jess%20stockstill%20picayune&pg=PA912 |url-status=live }}</ref> In 1882, the university began admitting women<ref>[[#Cohodas|Cohodas (1997)]], p. 18.</ref> but they were not permitted to live on campus or attend law school.<ref name="history"/> In 1885, the University of Mississippi hired [[Sarah McGehee Isom]], becoming the first [[Southeastern United States|southeastern US]] college to hire a female faculty member.<ref name="history"/><ref name="isom">{{cite web |url=https://sarahisomcenter.org/about-1 |title=History |website=Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies |publisher=University of Mississippi |access-date=July 24, 2021 |archive-date=July 24, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210724182727/https://sarahisomcenter.org/history |url-status=live }}</ref> Nearly 100 years later, in 1981, the Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies was established in her honor.<ref name="history"/><ref name="isom"/> |

|||

The Lyceum was used as a hospital during the Civil War for both [[Union (American Civil War)|Union]] and Confederate soldiers, especially those who were wounded at the [[battle of Shiloh]]. Two hundred-fifty soldiers who died in the campus hospital were buried in a cemetery on the grounds of the university.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://maps.google.com/maps/place?q=Confederate+Cemetery&cid=1000215249802079370|title=Confederate Cemetery - About - Google |publisher=Maps.google.com|date=|accessdate=December 14, 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.civilwarcenter.olemiss.edu/cemeteries_csa.html|title=The Center for Civil War Research|publisher=|accessdate=May 29, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

The university's byname "Ole Miss" was first used in 1897, when it won a contest of suggestions for a yearbook title.<ref name="cnn">{{cite news |last=McLaughlin |first=Elliott C. |date=July 27, 2021 |title=The Battle over Ole Miss: Why a flagship university has stood behind a nickname with a racist past |url=https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/27/us/ole-miss-university-mississippi-name-controversy/index.html |publisher=CNN |access-date=May 13, 2021 |archive-date=December 4, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201204060212/https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/27/us/ole-miss-university-mississippi-name-controversy/index.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The term originated as a title domestic slaves used to distinguish the mistress of a plantation from "young misses".<ref>[[#Sansing|Sansing (1999)]], pp. 168–169.</ref> Fringe origin theories include it coming from a diminutive of "Old Mississippi",<ref>[[#Cabaniss|Cabaniss (1949)]], p. 129.</ref><ref>[[#Eagles|Eagles (2009)]], p. 17.</ref><ref name="sansing168"/> or from the name of the "Ole Miss" train that ran from [[Memphis, Tennessee|Memphis]] to [[New Orleans]].<ref name="cnn"/><ref>{{cite news |last=Elmore |first=Albert Earl |date=October 24, 2014 |title=Scholar Finds Evidence 'Ole Miss' Train Key in Establishing University Nickname |url=https://www.hottytoddy.com/2014/10/24/scholar-finds-evidence-ole-miss-train-key-in-establishing-university-nickname/ |work=Hotty Toddy |access-date=May 13, 2021 |archive-date=October 30, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201030185645/https://www.hottytoddy.com/2014/10/24/scholar-finds-evidence-ole-miss-train-key-in-establishing-university-nickname/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Within two years, students and alumni were using "Ole Miss" to refer to the university.<ref>[[#Sansing|Sansing (1999)]], p. 169.</ref> |

|||

During the post-war period, the university was led by former Confederate [[general]] [[A.P. Stewart]], a [[Rogersville, Tennessee]] native. He served as Chancellor from 1874 to 1886.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.olemiss.edu/depts/chancellor/inauguration/chancellors.html|title=2010 Chancellor's Inauguration - The University of Mississippi|publisher=Olemiss.edu|date=|accessdate=December 14, 2012 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20121202013004/http://www.olemiss.edu/depts/chancellor/inauguration/chancellors.html|archivedate=December 2, 2012}}</ref> |

|||

Between 1900 and 1930, the Mississippi Legislature introduced bills aiming to relocate, close, or merge the university with [[Mississippi State University]]. All such legislation failed.<ref>[[#Sansing|Sansing (1999)]], Ch. 8.</ref> During the 1930s, the governor of Mississippi [[Theodore G. Bilbo]] was politically hostile toward the University of Mississippi, firing administrators and faculty, and replacing them with his friends<ref name="barrett23" /> in the "Bilbo purge".<ref>[[#Sansing|Sansing (1999)]], p. 240.</ref> Bilbo's actions severely damaged the university's reputation, leading to the temporary loss of its accreditation. Consequently, in 1944, the [[Constitution of Mississippi]] was amended to protect the university's board of trustees from political pressure.<ref name="barrett23">[[#Barrett|Barrett (1965)]], p. 23.</ref> During [[World War II]], the University of Mississippi was one of 131 colleges and universities that participated in the national [[V-12 Navy College Training Program]], which offered students a path to a Navy commission.<ref name="list-of-v-12">{{cite web |url=http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/Admin-Hist/115-8thND/115-8ND-23.html |title=U.S. Naval Administration in World War II |publisher=HyperWar Foundation |access-date=September 29, 2011 |archive-date=January 12, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120112105122/http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/Admin-Hist/115-8thND/115-8ND-23.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

The university became [[coeducational]] in 1882 and was the first such institution in the Southeast to hire a female faculty member, [[Sarah McGehee Isom]], doing so in 1885.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.olemiss.edu/depts/sarah_isom_center/aboutsarahisom.html|title=Sarah Isom Center for Women |publisher=Olemiss.edu|accessdate=December 14, 2012 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110818085158/http://www.olemiss.edu/depts/sarah_isom_center/aboutsarahisom.html|archivedate=August 18, 2011}}</ref> |

|||

===Integration=== |

|||

The student yearbook was published for the first time in 1897. A contest was held to solicit suggestions for a yearbook title from the student body. Elma Meek, a student, submitted the winning entry of "Ole Miss." Meek's source for the term is unknown; some historians theorize she made a diminutive of "old Mississippi" or derived the term from "ol' missus," an African-American term for a plantation's "old mistress."<ref>''The Mississippian'', May 13, 1939, "Ole Miss Takes Its Name From Darky Dialect, Not Abbreviation of State"</ref><ref>{{cite book|first=J. A.|last=Cabaniss|title= The University of Mississippi; Its first hundred years|year=1949|publisher=University & College Press Of Mississippi|isbn=978-0-87805-000-0}}p. 129</ref><ref>{{cite book |first=Charles |last=Eagles|title=The Price of Defiance: James Meredith and the Integration of Ole Miss|year=2009|publisher=The University of North Carolina Press|isbn=978-0-8078-3273-8}}p. 17</ref><ref>{{cite book|first=David|last= Sansing|title=The University of Mississippi: A Sesquicentennial History |year=1999 |publisher=University Press of Mississippi|isbn=978-1-57806-091-7}} p. 168</ref> This sobriquet was not only chosen for the yearbook, but also became the name by which the university was informally known.<ref>[http://www.olemiss.edu/depts/smc/yearbook.html ''The Ole Miss'' Student Yearbook] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131001151111/http://www.olemiss.edu/depts/smc/yearbook.html |date=October 1, 2013 }}</ref> "Ole Miss" is defined as the school's intangible spirit, which is separate from the tangible aspects of the university.<ref>{{cite book|first=Frank E.|last=Everett|title=Frank E. Everett Collection (MUM00123)|year=1962|publisher=The Department of Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.olemisssports.com/trads/ole-miss-trads.html|title=OLE MISS Official Athletic Site - Traditions|publisher=Olemisssports.Com|accessdate=December 14, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160630004439/http://www.olemisssports.com/trads/ole-miss-trads.html|archive-date=June 30, 2016|dead-url=yes|df=mdy-all}}</ref> |

|||

{{Further|Ole Miss riot of 1962}} |

|||

[[File:James Meredith OleMiss.jpg|thumb|alt=James Meredith accompanied by federal officials on either side before the columns of the Lyceum|[[James Meredith]] accompanied by federal officials on campus]] |

|||

In 1954, the [[Supreme Court of the United States|U.S. Supreme Court]] ruled in ''[[Brown v. Board of Education]]'' [[Racial segregation in the United States|racial segregation]] in public schools was unconstitutional.<ref>[[#Roberts|Roberts & Klibanoff (2006)]], pp. 61–62.</ref> Eight years after the ''Brown'' decision, all attempts by African American applicants to enroll had failed.<ref name="bryant60">[[#Bryant|Bryant (2006)]], p. 60.</ref><ref>[[#Cohodas|Cohodas (1997)]], p. 114.</ref> Shortly after the 1961 inauguration of President [[John F. Kennedy]], [[James Meredith]]—an African American [[United States Air Force|Air Force]] veteran and former student at [[Jackson State University]]—applied to the University of Mississippi.<ref name="cohodas112">[[#Cohodas|Cohodas (1997)]], p. 112.</ref> After months of obstruction by Mississippi officials, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered Meredith's enrollment, and the [[United States Department of Justice|Department of Justice]] under Attorney General [[Robert F. Kennedy]] entered the case on Meredith's behalf.<ref name="bryant60"/><ref>[[#Roberts|Roberts & Klibanoff (2006)]], p. 276.</ref> On three occasions, either governor [[Ross R. Barnett]] or lieutenant governor [[Paul B. Johnson Jr.]] physically blocked Meredith's entry to the campus.<ref>[[#Heymann|Heymann (1998)]], p. 282.</ref><ref>[[#Roberts|Roberts & Klibanoff (2006)]], p. 288.</ref> |

|||

The university began medical education in 1903, when the [[University of Mississippi School of Medicine]] was established on the Oxford campus. In that era, the university provided two-year pre-clinical education certificates, and graduates went out of state to complete doctor of medicine degrees. In 1950, the Mississippi Legislature voted to create a four-year medical school. On July 1, 1955, the University Medical Center opened in the capital of [[Jackson, Mississippi]], as a four-year medical school. The [[University of Mississippi Medical Center]], as it is now called, is the health sciences campus of the University of Mississippi. It houses the University of Mississippi School of Medicine along with five other health science schools: nursing, dentistry, health-related professions, graduate studies and pharmacy (The School of Pharmacy is split between the Oxford and University of Mississippi Medical Center campuses).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.umc.edu/medical_center/overview.html|title=Overview - University of Mississippi Medical Center|publisher=Umc.edu|date=November 3, 2011|accessdate=December 14, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120222200427/http://www.umc.edu/medical_center/overview.html|archive-date=February 22, 2012|dead-url=yes|df=mdy-all}}</ref> |

|||

The [[United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit]] held both Barnett and Johnson Jr. in contempt, and issued fines exceeding $10,000 for each day they refused to enroll Meredith.<ref>{{Cite news |agency=Associated Press |date=November 7, 1987 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1987/11/07/obituaries/ross-barnett-segregationist-dies-governor-of-mississippi-in-1960-s.html?sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all |work=The New York Times |title=Ross Barnett, Segregationist, Dies; Governor of Mississippi in 1960's |access-date=May 27, 2010 |archive-date=April 24, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210424203209/https://www.nytimes.com/1987/11/07/obituaries/ross-barnett-segregationist-dies-governor-of-mississippi-in-1960-s.html?sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all |url-status=live }}</ref> On September 30, 1962, President Kennedy dispatched 127 [[United States Marshals Service|U.S. Marshals]], 316 deputized [[United States Border Patrol|U.S. Border Patrol]] agents, and 97 federalized [[Federal Bureau of Prisons]] personnel to escort Meredith.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.usmarshals.gov/news/chron/2012/093012.htm |title=U.S. Marshals Mark 50th Anniversary of the Integration of 'Ole Miss' |website=U.S. Marshals Service |publisher=U.S. Department of Justice |access-date=April 24, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200523031013/https://www.usmarshals.gov/news/chron/2012/093012.htm |archive-date=May 23, 2020 |url-status=dead }}</ref> After nightfall, far-right former Major General [[Edwin Walker]] and outside agitators arrived, and a gathering of segregationist students before the Lyceum became a violent mob.<ref>[[#Sansing|Sansing (1999)]], p. 302.</ref><ref name="roberts292">[[#Roberts|Roberts & Klibanoff (2006)]], p. 292.</ref><ref>[[#Scheips|Scheips (2005)]], p. 102.</ref> Segregationist rioters threw [[Molotov cocktail]]s and [[Acid attack|bottles of acid]], and fired guns at federal marshals and reporters.<ref>[[#Roberts|Roberts & Klibanoff (2006)]], pp. 291–292.</ref><ref>[[#Scheips|Scheips (2005)]], p. 105.</ref> 160 marshals would be injured, with 28 receiving gunshot wounds,<ref>{{cite web |last1=Rateshtari |first1=Roya |title=The U.S. Marshals and the Integration of the University of Mississippi {{!}} U.S. Marshals Service |url=https://www.usmarshals.gov/who-we-are/history/historical-reading-room/us-marshals-and-integration-of-university-of-mississippi |website=www.usmarshals.gov |date=June 17, 2020 |access-date=August 31, 2024 |archive-date=March 29, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240329001244/https://www.usmarshals.gov/who-we-are/history/historical-reading-room/us-marshals-and-integration-of-university-of-mississippi |url-status=live }}</ref> and two civilians—French journalist [[Paul Guihard]] and Oxford repairman Ray Gunter—were killed by gunfire.<ref>[[#Wickham|Wickham (2011)]], pp. 102–112.</ref><ref name="Time"/> Eventually, 13,000 soldiers arrived in Oxford and quashed the riot.<ref>[[#Roberts|Roberts & Klibanoff (2006)]], p. 297.</ref> One-third of the federal officers—166 men—were injured, as were 40 federal soldiers and National Guardsmen.<ref name="Time">{{cite magazine |title=The States: Though the Heavens Fall |magazine=Time |url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,829233-5,00.html |access-date=October 3, 2007 |date=October 12, 1962 |archive-date=October 14, 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071014014142/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,829233-5,00.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> More than 30,000 personnel were deployed, alerted, and committed in Oxford—the most in American history for a single disturbance.<ref>[[#Scheips|Scheips (2005)]], pp. 120−121.</ref> |

|||

Several attempts were made via the executive and legislative branches of the Mississippi state government to relocate or otherwise close the University of Mississippi. The Mississippi Legislature between 1900 and 1930 introduced several bills aiming to accomplish this, but no such legislation was ever passed by either house. One such bill was introduced in 1912 by Senator William Ellis of Carthage, Mississippi, which would have merged the college with then-Mississippi A&M.<ref>David Sansing, The History of the University of Mississippi: A Sesquicentennial History, Ch. 8</ref> However, this measure was soundly defeated, despite the bill only seeking to form an exploratory committee. In February 1920, 56 members of the legislature arrived on campus and discussed with students and faculty the idea of consolidating MS A&M, MS College of Women and Ole Miss to be located in Jackson, rather than appropriate $750,000.00 of funds requested by then-Chancellor Joseph Powers which were needed to repair dilapidated and structurally unsound buildings on the campus, which was discovered following the partial collapse of a dormitory in 1917 and a scathing review of other buildings later that same year by the state architect.<ref>David Sansing, The History of the University of Mississippi: A Sesquicentennial History, Ch. *</ref> These funds, plus an additional $300,000.00 were appropriated to the school, which was used to build 4 male dormitories, a female dormitory and a pharmacy building, which partially resolved a longstanding issue of inadequate dormitory space for students. During the 1930s, [[Governor of Mississippi|Mississippi Governor]] [[Theodore G. Bilbo]], a populist, tried to move the university to [[Jackson, Mississippi|Jackson]]. Chancellor [[Alfred Hume]] gave the state legislators a grand tour of Ole Miss and the surrounding historic city of Oxford, persuading them to keep it in its original setting. |

|||

Meredith enrolled and attended a class on October 1.<ref>{{cite news |title=1962: Mississippi race riots over first black student |work=BBC News |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/october/1/newsid_2538000/2538169.stm |access-date=October 2, 2007 |date=October 1, 1962 |archive-date=October 5, 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071005031808/http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/october/1/newsid_2538000/2538169.stm |url-status=live }}</ref> By 1968, Ole Miss had around 100 African American students,<ref>[[#Sansing|Sansing (1999)]], p. 321.</ref> and by the 2019–2020 academic year, African Americans constituted 12.5 percent of the student body.<ref name="demo">{{cite web |url=https://irep.olemiss.edu/fall-2019-2020-enrollment/ |title=Fall 2019-2020 Enrollment |website=Office of Institutional Research, Effectiveness, and Planning |publisher=University of Mississippi |access-date=June 2, 2021 |archive-date=June 2, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210602214300/https://irep.olemiss.edu/fall-2019-2020-enrollment/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

During [[World War II]], UM was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the [[V-12 Navy College Training Program]], which offered students a path to a Navy commission.<ref name="list-of-v-12">{{cite web|url=http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/Admin-Hist/115-8thND/115-8ND-23.html |title=U.S. Naval Administration in World War II|publisher=HyperWar Foundation|accessdate=September 29, 2011|year=2011}}</ref> |

|||

===Recent history=== |

|||

===Integration of 1962 and legacy=== |

|||

[[File:Rowan Oak.JPG|thumb|alt=A white house set among trees|The university owns [[Rowan Oak]], former home of [[Nobel Prize in Literature|Nobel Prize]]-winning writer [[William Faulkner]] and a [[National Historic Landmark]].<ref name="nrhpinv2">{{Cite journal |title=National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: William Faulkner Home, Rowan Oak |url={{NHLS url |id=68000028}} |date=March 30, 1976 |author=Polly M. Rettig and John D. McDermott |publisher=National Park Service |access-date=July 20, 2022 }}</ref>]] |

|||

[[File:James Meredith OleMiss.jpg|thumb|right|James Meredith walking to class at the University of Mississippi, accompanied by [[United States Marshals Service|U.S. Marshals]]]] |

|||

In 1972, Ole Miss purchased [[Rowan Oak]], the former home of [[Nobel Prize in Literature|Nobel Prize]]–winning writer [[William Faulkner]].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.rowanoak.com/about/history/ |title=History |website=Rowan Oak |publisher=University of Mississippi |access-date=March 23, 2021 |archive-date=March 10, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210310085413/https://www.rowanoak.com/about/history/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last=Luesse |first=Valerie Fraser |date=September 25, 2020 |title=The Haunted History of William Faulkner's Rowan Oak |url=https://www.southernliving.com/travel/mississippi/rowan-oak |work=Southern Living |access-date=March 23, 2021 |archive-date=February 25, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210225053719/https://www.southernliving.com/travel/mississippi/rowan-oak |url-status=live }}</ref> The building has been preserved as it was at Faulkner's death in 1962. Faulkner was the university's postmaster in the early 1920s and wrote ''[[As I Lay Dying]]'' (1930) at the university powerhouse. His Nobel Prize medallion is displayed in the university library.<ref>{{cite news |last=Boyer |first=Allen |date=June 3, 1984 |title=William Faulkner's Mississippi |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/travel/1984/06/03/william-faulkners-mississippi/79c5a57b-af93-47ec-a5e5-1bebedd45468/ |newspaper=The Washington Post |access-date=March 23, 2021 |archive-date=June 25, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210625173035/https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/travel/1984/06/03/william-faulkners-mississippi/79c5a57b-af93-47ec-a5e5-1bebedd45468/ |url-status=live }}</ref> The university hosted the inaugural Faulkner and [[Yoknapatawpha County|Yoknapatawpha]] Conference in 1974. In 1980, [[Willie Morris]] became the university's first writer in residence.<ref name="history">{{cite web |url=https://mississippiencyclopedia.org/entries/university-of-mississippi/ |title=University of Mississippi |website=The Mississippi Encyclopedia |access-date=April 29, 2021 |archive-date=August 13, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200813102848/https://mississippiencyclopedia.org/entries/university-of-mississippi/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

{{See also|Ole Miss riot of 1962}} |

|||

[[Desegregation]] came to Ole Miss in the early 1960s with the activities of [[United States Air Force]] veteran [[James Meredith]] from [[Kosciusko, Mississippi]]. Even Meredith's initial efforts required great courage. All involved knew how violently [[William David McCain]] and the white political establishment of Mississippi had recently reacted to similar efforts by [[Clyde Kennard]] to enroll at Mississippi Southern College (now the [[University of Southern Mississippi]]).<ref name="Funding">''The Funding of Scientific Racism: Wickliffe Draper and the Pioneer Fund'' by William H. Tucker, University of Illinois Press (May 30, 2007), pp 165-66.</ref><ref name="Confederacy">{{cite book|title=Neo-Confederacy: A Critical Introduction|editor-first1=Euan|editor-last1=Hague|editor-first2=Heidi|editor-last2=Beirich|editor-first3=Edward H.|editor-last3=Sebesta|publisher=University of Texas Press|date=2008|isbn=978-0-2927-7921-1|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LfWdaR9wHEEC|pp=284–285}}</ref><ref name="report">{{cite web |url=http://www.splcenter.org/intel/intelreport/article.jsp?aid=135|title=Sons of Confederate Veterans in its own Civil War | Southern Poverty Law Center|publisher=Splcenter.org |accessdate=December 14, 2012}}</ref><ref name="Evers">''Medgar Evers'' by Jennie Brown, Holloway House Publishing, 1994, pp. 128-132.</ref> |

|||

In 2002, Ole Miss marked the 40th anniversary of integration with a yearlong series of events, including an oral history of the university, symposiums, a memorial, and a reunion of federal marshals who served at the campus.<ref name="Byrd">{{cite news |first=Shelia Hardwell |last=Byrd |title=Meredith ready to move on |agency=Associated Press |work=Athens Banner-Herald |url=http://www.onlineathens.com/stories/092102/new_20020921041.shtml |date=September 21, 2002 |access-date=October 2, 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071016065534/http://www.onlineathens.com/stories/092102/new_20020921041.shtml |archive-date=October 16, 2007 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last=Halbfinger |first=David M. |date=September 27, 2002 |title=40 Years After Infamy, Ole Miss Looks to Reflect and Heal |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2002/09/27/us/40-years-after-infamy-ole-miss-looks-to-reflect-and-heal.html |work=The New York Times |access-date=June 23, 2021 |archive-date=April 23, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190423161142/https://www.nytimes.com/2002/09/27/us/40-years-after-infamy-ole-miss-looks-to-reflect-and-heal.html |url-status=live }}</ref> In 2006, the 44th anniversary of integration, a [[Statue of James Meredith|statue of Meredith]] was dedicated on campus.<ref>{{Cite news |agency=Associated Press |date=October 2, 2006 |title=Ole Miss dedicates civil rights statue |url=https://www.deseret.com/2006/10/2/19977165/ole-miss-dedicates-civil-rights-statue |work=Deseret News |access-date=July 2, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210311211541/https://www.deseret.com/2006/10/2/19977165/ole-miss-dedicates-civil-rights-statue |archive-date=March 11, 2021 |url-status=live }}</ref> Two years later, the site of the 1962 riots was designated as a [[National Historic Landmark]].<ref name="nhlnom">{{Cite book |url=http://www.nps.gov/history/nhl/Fall07Nominations/Lyceum.pdf |title=National Historic Landmark Nomination: Lyceum |date=January 23, 2007 |first1=Gene |last1=Ford |first2=Susan Cianci |last2=Salvatore |publisher=National Park Service |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090226084158/http://www.nps.gov/history/nhl/Fall07Nominations/Lyceum.pdf |archive-date=February 26, 2009 }}</ref> The university also held a yearlong program to mark the 50th anniversary of integration in 2012.<ref>{{cite news |first=Campbell |last=Robertson |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/01/us/university-of-mississippi-commemorates-integration.html?ref=universityofmississippi&_r=0 |work=The New York Times |title=University of Mississippi Commemorates Integration |date=September 30, 2012 |access-date=February 20, 2017 |archive-date=April 24, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210424203136/https://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/01/us/university-of-mississippi-commemorates-integration.html?ref=universityofmississippi&_r=0 |url-status=live }}</ref> The university hosted the [[United States presidential election debates, 2008#September 26: First presidential debate (University of Mississippi)|first presidential debate of 2008]]—the first presidential debate held in Mississippi—between Senators [[John McCain]] and [[Barack Obama]].<ref>{{cite news |last=Dewan |first=Shaila |date=September 23, 2008 |title=Debate Host, Too, Has a Message of Change |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/24/us/24miss.html |work=The New York Times |access-date=April 29, 2021 |archive-date=April 29, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210429181411/https://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/24/us/24miss.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |via=McClatchy newspapers |date=September 22, 2008 |title=Debates give University of Mississippi a chance to highlight racial progress |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/sep/22/uselections2008.race |work=The Guardian |access-date=April 29, 2021 |archive-date=April 29, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210429181411/https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/sep/22/uselections2008.race |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

Meredith won a lawsuit that allowed him admission to The University of Mississippi in September 1962. He attempted to enter campus on September 20, September 25, and again on September 26,<ref>[http://www.jfklibrary.org/meredith/chron_main.html] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091112203712/http://www.jfklibrary.org/meredith/chron_main.html|date=November 12, 2009}}</ref> only to be blocked by Mississippi Governor [[Ross R. Barnett]], who proclaimed that "...No school in our state will be integrated while I am your Governor. I shall do everything in my power to prevent integration in our schools." <ref>[https://www.successpoint.ae/campus-life/] {{URL|successpoint.ae|Success Point College|date=April 09, 2019}}</ref> |

|||

Ole Miss retired its mascot [[Colonel Reb]] in 2003, citing its Confederate imagery.<ref>{{cite news |last=Martin |first=Michael |date=February 25, 2010 |title=Ole Miss Retires Controversial Mascot |url=https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=124081743 |work=NPR |access-date=April 5, 2021 |archive-date=April 24, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210424203206/https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=124081743 |url-status=live }}</ref> Although a grass-roots movement to adopt ''[[Star Wars]]'' character [[Admiral Ackbar]] of the [[Rebel Alliance]] gained significant support,<ref>{{cite magazine |last=Malinowski |first=Erik |date=September 8, 2010 |title=Ole Miss' Admiral Ackbar Campaign Fizzles |url=https://www.wired.com/2010/09/ole-miss-admiral-ackbar/ |magazine=Wired |access-date=April 5, 2021 |archive-date=January 30, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210130212446/https://www.wired.com/2010/09/ole-miss-admiral-ackbar/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |first1=Larry |last1=Hartstein |first2=Ty |last2=Tagami |date=March 1, 2010 |title=Admiral Ackbar for Ole Miss mascot spurs backlash |url=https://www.ajc.com/entertainment/celebrity-news/admiral-ackbar-for-ole-miss-mascot-spurs-backlash/mLpbHwbEjzarKjx17EMyzN/ |work=The Atlanta Journal-Constitution |access-date=August 29, 2021 |archive-date=June 5, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190605024512/https://www.ajc.com/entertainment/celebrity-news/admiral-ackbar-for-ole-miss-mascot-spurs-backlash/mLpbHwbEjzarKjx17EMyzN/ |url-status=live }}</ref> [[Rebel Black Bear]], a reference to Faulkner's short story ''[[Go Down, Moses (book)#The Bear|The Bear]]'', was selected in 2010.<ref>{{cite news |last=Stevens |first=Stuart |date=October 31, 2015 |title=Between Ole Miss and Me |url=https://www.thedailybeast.com/between-ole-miss-and-me |work=The Daily Beast |access-date=June 28, 2021 |archive-date=July 1, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210701193349/https://www.thedailybeast.com/between-ole-miss-and-me |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="shark"/> The Bear was replaced with another mascot, [[Tony the Landshark]], in 2017.<ref name="shark">{{cite news |date=October 6, 2017 |title=Ole Miss adopts Landshark as new official mascot for athletic events |url=https://www.espn.com/college-football/story/_/id/20939377/ole-miss-rebels-retire-rebel-bear-mascot-replaced-landshark |publisher=ESPN |access-date=April 5, 2021 |archive-date=December 11, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201211133810/https://www.espn.com/college-football/story/_/id/20939377/ole-miss-rebels-retire-rebel-bear-mascot-replaced-landshark |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last=Lee |first=Maddie |url=https://www.clarionledger.com/story/sports/college/ole-miss/2018/08/11/ole-miss-unveils-its-landshark-mascot-meet-rebels-day/966506002/ |title=Ole Miss unveils its Landshark mascot, a melding of Rebels history and Hollywood design |work=The Clarion Ledger |access-date=September 8, 2018 |archive-date=April 24, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210424203207/https://www.clarionledger.com/story/sports/college/ole-miss/2018/08/11/ole-miss-unveils-its-landshark-mascot-meet-rebels-day/966506002/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Beginning in 2022, football coach [[Lane Kiffin]]'s dog Juice became the de facto mascot.<ref>{{cite news |last=Suss |first=Nick |date=August 12, 2022 |title=How Lane Kiffin's dog, Juice, has become the face of Ole Miss football |url=https://finance.yahoo.com/news/lane-kiffins-dog-juice-become-175246429.html |work=USA Today |access-date=November 13, 2022 |archive-date=September 3, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240903080850/https://sports.yahoo.com/lane-kiffins-dog-juice-become-175246429.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine |last=King |first=Ben |date=October 5, 2022 |title=Lane Kiffin's Dog 'Juice' Agrees to NIL Deal With The Grove Collective |url=https://www.si.com/college/olemiss/football/ole-miss-rebels-nil-deal-juice-kiffin |magazine=Sports Illustrated |access-date=November 13, 2022 |archive-date=November 13, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221113190816/https://www.si.com/college/olemiss/football/ole-miss-rebels-nil-deal-juice-kiffin |url-status=live }}</ref> In 2015, the university removed the [[Flag of Mississippi|Mississippi State Flag]], which included the Confederate battle emblem,<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.cnn.com/2015/10/26/us/ole-miss-confederate-state-flag-removed-campus/index.html |title=Ole Miss removes state flag from campus |date=October 26, 2015 |first=Eliott C. |last=McLaughlin |publisher=CNN |access-date=May 10, 2019 |archive-date=April 24, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210424203122/https://www.cnn.com/2015/10/26/us/ole-miss-confederate-state-flag-removed-campus/index.html |url-status=live }}</ref> and in 2020, it relocated a prominent Confederate monument.<ref>{{cite news |last=Pettus |first=Emily Wagster |date=July 14, 2020 |title=Ole Miss moves Confederate statue from prominent campus spot |url=https://apnews.com/article/us-news-ap-top-news-oxford-mississippi-ms-state-wire-d5824d7b24b9d7af5976da60741d4a28 |work=Associated Press |access-date=August 2, 2021 |archive-date=June 2, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210602175814/https://apnews.com/article/us-news-ap-top-news-oxford-mississippi-ms-state-wire-d5824d7b24b9d7af5976da60741d4a28 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

After the [[United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit]] held both Barnett and Lieutenant Governor [[Paul B. Johnson, Jr.]] in contempt, with fines of more than $10,000 for each day they refused to allow Meredith to enroll,<ref>{{Cite news| url=https://www.nytimes.com/1987/11/07/obituaries/ross-barnett-segregationist-dies-governor-of-mississippi-in-1960-s.html?sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all|work=The New York Times|title=Ross Barnett, Segregationist, Dies; Governor of Mississippi in 1960's|date=November 7, 1987|accessdate=May 27, 2010}}</ref> Meredith, escorted by a force of [[United States Marshals Service|U.S. Marshals]], entered the campus on September 30, 1962.<ref>[http://www.eotu.uiuc.edu/pedagogy/grogers/GRP/Meredith_1.htm] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100706035016/http://www.eotu.uiuc.edu/pedagogy/grogers/GRP/Meredith_1.htm|date=July 6, 2010}}</ref> |

|||

==Campus== |

|||

Two people were killed by gunfire during the riot, a French journalist, [[Paul Guihard]] and an Oxford repairman, Ray Gunter.<ref>{{cite book |last=Doyle |first=William|title=An American Insurrection|year=2001|publisher=Doubleday|location=New York, NY|isbn=978-0385499699|page=215}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |title=The Civil Rights Movement: Struggle and Resistance|author=Riches, William T. Martin|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan, 2004}}</ref> One-third of the US Marshals, 166 men, were injured, as were 40 soldiers and National Guardsmen.<ref name="Time">{{cite news|title=The States: Though the Heavens Fall |work=TIME |url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,829233-5,00.html|accessdate=October 3, 2007|date=October 12, 1962}}</ref> |

|||

===Oxford campus=== |

|||

After control was re-established by federal forces, Meredith, thanks to the protection afforded by federal marshals, was able to enroll and attend his first class on October 1. Following the [[riot]], elements of an [[Army National Guard]] division were stationed in Oxford to prevent future similar violence. While most Ole Miss students did not riot prior to his official enrollment in the university, many harassed Meredith during his first two semesters on campus.<ref name="cohodas">''The band played Dixie: Race and the liberal conscience at Ole Miss'', Nadine Cohodas, (1997), New York, Free Press</ref> |

|||

{{wide image|File:Panorama of Courtyard with Lyceum Building - University of Mississippi - Oxford - Mississippi - USA.jpg|alt=Panoramic view of the courtyard behind the Lyceum|align-cap=center|1089px|Panoramic view of the courtyard behind the [[Lyceum (Mississippi)|Lyceum]] (1848)}} |

|||

The University of Mississippi's Oxford campus is partially located in Oxford and partially in [[University, Mississippi]], a [[census-designated place]].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www2.census.gov/geo/maps/DC2020/DC20BLK/st28_ms/place/p2875520_university/DC20BLK_P2875520.pdf |title=2020 census - census block map: University CDP, MS |publisher=[[U.S. Census Bureau]] |access-date=August 14, 2022 |quote=Univ of Mississippi (blue text) |archive-date=August 14, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220814055324/https://www2.census.gov/geo/maps/DC2020/DC20BLK/st28_ms/place/p2875520_university/DC20BLK_P2875520.pdf |url-status=live }}<br />{{cite web |url=https://www2.census.gov/geo/maps/DC2020/DC20BLK/st28_ms/place/p2854840_oxford/DC20BLK_P2854840.pdf |title=2020 CENSUS - CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Oxford city, MS |publisher=[[U.S. Census Bureau]] |access-date=August 14, 2022 |quote=Univ of Mississippi |page=1 (PDF p. 2/5) |archive-date=July 21, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220721211613/https://www2.census.gov/geo/maps/DC2020/DC20BLK/st28_ms/place/p2854840_oxford/DC20BLK_P2854840.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> The main campus is situated at an altitude of around {{Convert|500|feet|meters|abbr=out}}, and has expanded from {{Convert|1|sqmi|ha|abbr=out|spell=in}} of land to around {{Convert|1,200|acre|sqmi ha|abbr=out}}. The campus' buildings are largely designed in a [[Georgian architecture|Georgian architectural style]]; some of the newer buildings have a more contemporary architecture.<ref name="catalog.olemiss.edu">{{Cite web |url=https://catalog.olemiss.edu/university/buildings |title=About the University of Mississippi |website=UM Catalog |publisher=University of Mississippi |access-date=May 8, 2021 |archive-date=May 8, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210508215524/https://catalog.olemiss.edu/university/buildings |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

According to first-person accounts, students living in Meredith's dorm bounced basketballs on the floor just above his room through all hours of the night. When Meredith walked into the cafeteria for meals, the students eating would all turn their backs. If Meredith sat at a table with other students, all of whom were white, they would immediately move to another table.<ref name="cohodas"/> Many of these events are featured in the 2012 ESPN documentary film ''[[30 for 30#Volume II|Ghosts of Ole Miss]]''. |

|||

[[File:Barnard Observatory angled view.jpg|thumb|upright=1.2|alt=Barnard Observatory|[[Barnard Observatory]] (1859) was designed to house the world's largest telescope.]] |

|||

====Historical observations and remembrances==== |

|||

In 2002 the university marked the 40th anniversary of integration with a yearlong series of events titled "Open Doors: Building on 40 Years of Opportunity in Higher Education." These included an oral history of Ole Miss, various symposiums, the April unveiling of a $130,000 memorial, and a reunion of federal marshals who had served at the campus. In September 2003, the university completed the year's events with an international conference on race. By that year, 13% of the student body identified as African American. Meredith's son Joseph graduated as the top doctoral student at the School of Business Administration.<ref name="Byrd">{{cite news|author=Shelia Hardwell Byrd|title=Meredith ready to move on|agency=Associated Press, at Athens Banner-Herald (OnlineAthens)|url=http://www.onlineathens.com/stories/092102/new_20020921041.shtml|date=September 21, 2002|accessdate=October 2, 2007|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071016065534/http://www.onlineathens.com/stories/092102/new_20020921041.shtml|archive-date=October 16, 2007|dead-url=yes|df=mdy-all}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Historical Landmark Plague.jpg|thumb|right|upright|A plaque outside the Meek School of Journalism and New Media declaring campus a historic landmark in journalism by the [[Society of Professional Journalists]]]] |

|||

At the campus' center is "[[Lyceum–The Circle Historic District|The Circle]]", which consists of eight academic buildings organized around an ovaloid common. The buildings include the Lyceum (1848), the "Y" Building (1853), and six later buildings constructed in a [[Neoclassical Revival]] style.<ref name="nhlnom"/> The Lyceum was the first building on the campus and was expanded with two wings in 1903. According to the university, the Lyceum's bell is the oldest academic bell in the United States.<ref name="catalog.olemiss.edu"/> Near the Circle is [[The Grove (Ole Miss)|The Grove]], a {{Convert|10|acre|ha|abbr=out|adj=on}} plot of land that was set aside by chancellor [[Robert Burwell Fulton]] {{Circa|1893}}, and hosts up to 100,000 [[Tailgate party|tailgaters]] during home games.<ref>{{cite news |last=Anderson |first=Seph |date=April 17, 2013 |title=The Grove at Ole Miss: Where Football Saturdays Create Lifelong Memories |url=https://bleacherreport.com/articles/1607602-the-grove-at-ole-miss-where-football-saturdays-create-lifelong-memories |work=Bleacher Report |access-date=May 4, 2021 |archive-date=April 12, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200412210653/https://bleacherreport.com/articles/1607602-the-grove-at-ole-miss-where-football-saturdays-create-lifelong-memories |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="tailgate">{{cite news |last=Gentry |first=James K. |date=October 31, 2014 |title=Tailgating Goes Above and Beyond at the University of Mississippi |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/01/sports/ncaafootball/tailgating-goes-above-and-beyond-at-the-university-of-mississippi.html |work=The New York Times |access-date=May 4, 2021 |archive-date=May 6, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210506010818/https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/01/sports/ncaafootball/tailgating-goes-above-and-beyond-at-the-university-of-mississippi.html |url-status=live }}</ref> [[Barnard Observatory]], which was constructed under Chancellor Barnard in 1859, was designed to house the world's largest telescope. Due to the Civil War's outbreak, however, the telescope was never delivered and was instead acquired by [[Northwestern University]].<ref name="catalog.olemiss.edu"/><ref>[[#Sansing|Sansing (1999)]], p. 91.</ref> The observatory was listed on the [[National Register of Historic Places]] in 1978.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/78001607 |title=Barnard Observatory |website=NPGallery Digital Asset Management System |publisher=National Park Service |access-date=June 27, 2021 |archive-date=June 27, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210627225920/https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/78001607 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Sansing 1999 p. 315">[[#Sansing|Sansing (1999)]], p. 315.</ref> The first major building built after the Civil War was Ventress Hall, which was constructed in a [[Romanesque Revival architecture|Victorian Romanesque]] style in 1889.<ref name="catalog.olemiss.edu"/> |

|||

Six years later, in 2008, the site of the riots, known as [[Lyceum-The Circle Historic District]], was designated as a [[National Historic Landmark]].<ref name="nhlnom">{{Cite book|url=http://www.nps.gov/history/nhl/Fall07Nominations/Lyceum.pdf|title=National Historic Landmark Nomination: Lyceum|date=January 23, 2007|author=Gene Ford and Susan Cianci Salvatore|publisher=National Park Service |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20090226084158/http://www.nps.gov/history/nhl/Fall07Nominations/Lyceum.pdf|archivedate=February 26, 2009}}</ref> The district includes: |

|||

* The [[Lyceum-The Circle Historic District|Lyceum]] |

|||

* The [[Lyceum-The Circle Historic District|Circle]], including its flagpole and Confederate Monument. |

|||

* [[Croft Institute for International Studies]], also known as the "Y" Building |

|||

* Brevard Hall, also known as the "Old Chemistry" Building |

|||

* Carrier Hall |

|||

* Shoemaker Hall |

|||

* Ventress Hall |

|||

* Bryant Hall |

|||

* Peabody Hall |

|||

From 1929 to 1930, architect [[Frank P. Gates]] designed 18 buildings on campus, mostly in [[Georgian Revival architecture|Georgian Revival architectural style]], including (Old) University High School, Barr Hall, Bondurant Hall, Farley Hall (also known as Lamar Hall), Faulkner Hall, and Wesley Knight Field House.<ref name="clarionledgerobit">{{cite news |title=Frank Gates Dies Here; Rites Today |url=https://www.newspapers.com/image/185654466/?terms=%22Frank%2BGates%22 |access-date=November 7, 2017 |work=The Clarion Ledger |date=January 3, 1975 |page=7 |via=Newspapers.com |url-access=registration |archive-date=April 24, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210424203159/https://www.newspapers.com/image/185654466/?terms=%22Frank%2BGates%22 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="missdepartmentgates">{{cite web |title=Gates, Frank P., Co. (b.1895 - d.1975) |url=http://www.apps.mdah.ms.gov/Public/rpt.aspx?rpt=artisanSearch&Name=Gates%2C%20Frank%20P.%2C%20Co.&City=Any&Role=Any |website=Mississippi Department of Archives and History |access-date=November 7, 2017 |archive-date=April 24, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210424203201/https://www.apps.mdah.ms.gov/Public/rpt.aspx?rpt=artisanSearch&Name=Gates%2C+Frank+P.%2C+Co.&City=Any&Role=Any |url-status=live }}</ref> During the 1930s, the many building projects at the campus were largely funded by the [[Public Works Administration]] and other federal entities.<ref>[[#Sansing|Sansing (1999)]], pp. 252–253.</ref> Among the notable buildings built in this period is the dual-domed [[Kennon Observatory]] (1939).<ref>{{cite web |url=https://physics.olemiss.edu/kennon/ |title=Kennon Observatory |website=Department of Physics and Astronomy |publisher=University of Mississippi |access-date=August 3, 2021 |archive-date=August 4, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210804034731/https://physics.olemiss.edu/kennon/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

Additionally, on April 14, 2010, the university campus was declared a [[National Historic Sites (United States)|National Historic Site]] by the [[Society of Professional Journalists]] to honor reporters who covered the 1962 riot, including the late [[France|French]] reporter [[Paul Guihard]], a victim of the riot.<ref name="jmitchell">{{Cite news|url=http://blogs.clarionledger.com/jmitchell/2010/04/14/ole-miss-declared-national-historic-site/|title=Ole Miss declared National Historic Site|author=Jerry Mitchell|publisher=''[[The Clarion-Ledger]]''|date=April 14, 2010|accessdate=April 14, 2010 |deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://www.webcitation.org/5ozPEcbPo?url=http://blogs.clarionledger.com/jmitchell/2010/04/14/ole-miss-declared-national-historic-site/ |archivedate=April 14, 2010|df=}}</ref> |

|||

Two large modern buildings—the Ole Miss Union (1976) and Lamar Hall (1977)—caused controversy by diverging from the university's traditional architecture.<ref>[[#Sansing|Sansing (1999)]], pp. 315–316.</ref> In 1998, the Gertrude C. Ford Foundation donated $20 million to establish the Gertrude C. Ford Center for the Performing Arts,<ref>{{cite web |url=https://fordcenter.org/about/ |title=About |website=Gertrude C. Ford Center for the Performing Arts |publisher=University of Mississippi |access-date=July 22, 2021 |archive-date=January 26, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210126173210/https://fordcenter.org/about/ |url-status=live }}</ref> which was the first building on campus to be solely dedicated to the performing arts.<ref>[[#Sansing|Sansing (1999)]], p. 350.</ref> As of 2020, the university was constructing a {{Convert|202000|sqft|m2|adj=on}} [[STEM]] facility, the largest single construction project in the campus' history.<ref>{{cite news |last=Hahn |first=Tina H. |date=February 8, 2020 |title=Record-setting construction project at Ole Miss: Business leaders commit to STEM education |url=https://www.clarionledger.com/story/news/local/2020/02/08/ole-miss-stem-facility-construction-donation-duff-brothers/4667053002/ |work=The Clarion Ledger |access-date=May 19, 2021 |archive-date=June 2, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210602175747/https://www.clarionledger.com/story/news/local/2020/02/08/ole-miss-stem-facility-construction-donation-duff-brothers/4667053002/ |url-status=live }}</ref> The university owns and operates the [[University of Mississippi Museum]], which comprises collections of American fine art, Classical antiquities, and Southern folk art, as well as historic properties in Oxford.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://museum.olemiss.edu/about/history/ |title=History |website=The University of Mississippi Museum |publisher=University of Mississippi |access-date=July 22, 2021 |archive-date=April 13, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210413162640/https://museum.olemiss.edu/about/history/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Ole Miss also owns [[University-Oxford Airport]], which is located north of the main campus.<ref name="catalog.olemiss.edu"/> |

|||

North Mississippi Japanese Supplementary School, a [[Hoshuko|Japanese weekend school]], is operated in conjunction with Ole Miss, with classes held on campus.<ref name=HoshukoEN>"[http://usjp.olemiss.edu/english/ Japanese Supplementary School] {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220217042126/https://usjp.olemiss.edu/english/ |date=February 17, 2022 }}." OGE-US Japan Partnership, University of Mississippi. Retrieved on February 25, 2015.</ref><ref>"[http://usjp.olemiss.edu/maps/ 周辺案内] {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220217042123/https://usjp.olemiss.edu/maps/ |date=February 17, 2022 }}." North Mississippi Japanese Supplementary School at The University of Mississippi. Retrieved on April 1, 2015.</ref> It opened in 2008 and was jointly established by several Japanese companies and the university. Many children have parents who are employees at [[Toyota]] facilities in [[Blue Springs, Mississippi|Blue Springs]].<ref>{{cite web |last=McArthur |first=Danny |url=https://www.djournal.com/news/local/a-wide-perspective-learning-japanese-american-culture-through-language-and-education/article_e07e1b48-386b-5002-bf77-2a0bc23ccd26.html |title=A wide perspective': Learning Japanese, American culture through language and education |newspaper=Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal |date=October 24, 2021 |access-date=February 16, 2022 |archive-date=February 17, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220217040318/https://www.djournal.com/news/local/a-wide-perspective-learning-japanese-american-culture-through-language-and-education/article_e07e1b48-386b-5002-bf77-2a0bc23ccd26.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

From September 2012 to May 2013, the university marked its 50th anniversary of integration with a program called ''Opening the Closed Society'', referring to ''Mississippi: The Closed Society'', a 1964 book by James W. Silver, a history professor at the university.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/01/us/university-of-mississippi-commemorates-integration.html?ref=universityofmississippi&_r=0|work=The New York Times |first=Campbell|last=Robertson|title=University of Mississippi Commemorates Integration|date=September 30, 2012}}</ref> The events included lectures by figures such as Attorney General [[Eric H. Holder Jr.]] and the singer and activist [[Harry Belafonte]], movie screenings, panel discussions, and a "walk of reconciliation and redemption."<ref>[http://news.olemiss.edu/um-commemorates-50-years-of-integration/#.UQd15PJ0E04 Calendar Set for 50 Years of Integration at Ole Miss]. News.olemiss.edu (September 25, 2012). Retrieved on 2013-08-17.</ref> [[Myrlie Evers-Williams]], widow of Medgar Evers, slain civil rights leader and late president of the state NAACP, closed the observance on May 11, 2013, by delivering the address at the university's 160th commencement.<ref name="Mitchell">{{cite news |last=Mitchell|first=Jerry|title=Ole Miss honors Evers-Williams|url=http://www.clarionledger.com/article/20130512/NEWS01/305120048/Ole-Miss-honors-Evers-Williams|accessdate=May 29, 2013|newspaper=Clarion Ledger|date=May 11, 2013}}</ref><ref name="Mitchell"/> |

|||