Mount Shasta: Difference between revisions

m add {{Use mdy dates|date=January 2025}} |

|||

| (176 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Stratovolcano in California, United States}} |

|||

{{About|the volcano in California|the town|Mount Shasta, California|other peaks named Shasta|List of peaks named Shasta}} |

{{About|the volcano in California|the town|Mount Shasta, California|other peaks named Shasta|List of peaks named Shasta}} |

||

{{Use mdy dates|date=January 2025}} |

|||

{{Infobox mountain |

{{Infobox mountain |

||

| name = Mount Shasta |

| name = Mount Shasta |

||

| native_name = {{Native name list|tag1=sht|name1=Waka-nunee-Tuki-wuki|tag2=kyh|name2=Úytaahkoo}} |

|||

| photo = MtShasta aerial.JPG |

|||

| photo = MtShasta aerial.JPG |

|||

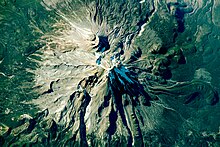

| photo_caption = Aerial view of Mount Shasta from the southwest, with sun low in the west |

|||

| photo_caption = Aerial view of Mount Shasta from the southwest |

|||

| elevation_system = NAVD88 |

|||

| elevation_system = [[NAVD88]] |

|||

| elevation = {{convert|14,179|ft|0|abbr=on}} |

|||

| elevation = {{convert|14,179|ft|0|abbr=on}} |

|||

| elevation_ref = <ref name=NGS>{{cite ngs|pid=MX1016|name=MT SHASTA|accessdate=January 6, 2016}}</ref> |

|||

| elevation_ref = <ref name=NGS>{{cite ngs|pid=MX1016|name=MT SHASTA|access-date=January 6, 2016}}</ref> |

|||

| prominence = {{convert|9,772|ft|0|abbr=on}} |

|||

| prominence = {{convert|9,772|ft|0|abbr=on}} |

|||

| prominence_ref = <ref name=PB>{{cite web|url=http://www.peakbagger.com/peak.aspx?pid=2477|title=Mount Shasta, California|publisher=Peakbagger.com|accessdate=January 6, 2016}}</ref> |

|||

| prominence_ref = <ref name=PB>{{cite web|url=http://www.peakbagger.com/peak.aspx?pid=2477|title=Mount Shasta, California|publisher=Peakbagger.com|access-date=January 6, 2016|archive-date=April 17, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190417140436/https://www.peakbagger.com/peak.aspx?pid=2477|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| isolation = {{convert|335|mi|0|abbr=on}} |

|||

| isolation = {{convert|335|mi|0|abbr=on}} |

|||

| isolation_ref = <ref name=PB /> |

|||

| |

| isolation_ref = <ref name=PB /> |

||

| parent_peak = [[North Palisade]]<ref name=PB /> |

|||

| listing = {{unbulleted list |

|||

|[[List of peaks by prominence|World most prominent peaks]] 96th |

| listing = {{unbulleted list |

||

|[[List of peaks by prominence|World most prominent peaks]] 96th |

|||

|[[List of the highest major summits of North America|North America highest peaks]] 48th |

|[[List of the highest major summits of North America|North America highest peaks]] 48th |

||

|[[List of the most prominent summits of North America|North America prominent peak]] 18th |

|[[List of the most prominent summits of North America|North America prominent peak]] 18th |

||

|[[List of the most prominent summits of the United States|US most prominent peaks]] 11th |

|[[List of the most prominent summits of the United States|US most prominent peaks]] 11th |

||

|[[List of the most isolated major summits of North America|North America isolated peaks]] 28th |

|[[List of the most isolated major summits of North America|North America isolated peaks]] 28th |

||

|[[List of the highest major summits of the United States|US highest major peaks]] 34th |

|[[List of the highest major summits of the United States|US highest major peaks]] 34th |

||

|[[List of highest mountain peaks of California|California highest major peaks]] 5th |

|[[List of highest mountain peaks of California|California highest major peaks]] 5th |

||

|[[List of California fourteeners|California fourteeners]] 5th |

|[[List of California fourteeners|California fourteeners]] 5th |

||

|[[List of |

|[[List of California county high points|California county high points]] 5th |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| location = [[Shasta–Trinity National Forest]], [[California]], [[United States|U.S.]] |

| location = [[Shasta–Trinity National Forest]], [[California]], [[United States|U.S.]] |

||

| map = USA California#USA |

| map = USA California#USA |

||

| map_caption = Location in California, U.S. |

| map_caption = Location in California, U.S. |

||

| map_size = 220 |

| map_size = 220 |

||

| label_position = left |

| label_position = left |

||

| range = [[Cascade Range]] |

| range = [[Cascade Range]] |

||

| coordinates = {{coord|41.409196033|N|122.194888358|W|type:mountain_region:US-CA_scale:100000|format=dms|display=inline,title}} |

| coordinates = {{coord|41.409196033|N|122.194888358|W|type:mountain_region:US-CA_scale:100000|format=dms|display=inline,title}} |

||

| coordinates_ref = <ref name=NGS /> |

| coordinates_ref = <ref name=NGS /> |

||

| range_coordinates = |

| range_coordinates = |

||

| topo = [[United States Geological Survey|USGS]] Mount Shasta |

| topo = [[United States Geological Survey|USGS]] Mount Shasta |

||

| type = [[Stratovolcano]] |

| type = [[Stratovolcano]] |

||

| age = About 593,000 years |

| age = About 593,000 years |

||

| volcanic_arc = [[Cascade Volcanoes|Cascade Volcanic Arc]] |

| volcanic_arc = [[Cascade Volcanoes|Cascade Volcanic Arc]] |

||

| last_eruption = |

| last_eruption = 1250<ref name="gvp">{{cite gvp|name=Shasta|vn=323010|access-date=2021-06-28}}</ref> |

||

| first_ascent = 1854 by E. D. Pearce and party<ref name="selters_zanger" /> |

| first_ascent = 1854 by E. D. Pearce and party<ref name="selters_zanger" /> |

||

| easiest_route = Avalanche Gulch ("John Muir") route: [[Scree|talus]]/snow climb<ref name="selters_zanger" /> |

| easiest_route = Avalanche Gulch ("John Muir") route: [[Scree|talus]]/snow climb<ref name="selters_zanger" /> |

||

| embedded = {{designation list | embed = yes |

| embedded = {{designation list | embed = yes |

||

| designation1 = NNL |

|||

| designation1_date = 1976 |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Mount Shasta''' ([[Karuk language|Karuk]]: ''Úytaahkoo'' |

'''Mount Shasta''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|ʃ|æ|s|t|ə}} {{respell|SHASS|tə}}; [[Shasta people|Shasta]]: ''Waka-nunee-Tuki-wuki'';<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.siskiyous.edu/library/shasta/documents/AB_Ch15.pdf |title=College of the Siskiyous - Mount Shasta Annotated Bibliography |access-date=2021-10-11 |archive-date=2022-02-12 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220212042048/https://www.siskiyous.edu//library/shasta/documents/AB_Ch15.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> [[Karuk language|Karuk]]: ''Úytaahkoo'')<ref>{{Cite web |last=Bright |first=William |author2=Susan Gehr |title=Karuk Dictionary and Texts |access-date=2012-07-06 |url=http://linguistics.berkeley.edu/~karuk/karuk-dictionary.php? |archive-date=2012-07-11 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120711223614/http://linguistics.berkeley.edu/~karuk/karuk-dictionary.php? |url-status=live }}</ref> is a [[Volcano#Volcanic activity|potentially active]]<ref>{{cite web | access-date=2017-03-29 | url=https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/old.1997/fs165-97/fs165-97.pdf | title=Living with Volcanic Risk in the Cascades | author=Dan Dzurisin | author2=Peter H. Stauffer | author3=James W. Hendley II | author4=Sara Boore | author5=Bobbie Myers | author6=Susan Mayfield | language=en-US | website=[[USGS]] | date=1997 | page=2 | archive-date=2017-05-25 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170525092907/https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/old.1997/fs165-97/fs165-97.pdf | url-status=live }}</ref> [[stratovolcano]] at the southern end of the [[Cascade Range]] in [[Siskiyou County, California]]. At an elevation of {{convert|14,179|ft|0|abbr=on}}, it is the second-highest peak in the Cascades and the [[List of California fourteeners|fifth-highest in the state]]. Mount Shasta has an estimated volume of {{convert|85|mi3|km3|abbr=off|sp=us}}, which makes it the most voluminous volcano in the [[Cascade Volcanoes|Cascade Volcanic Arc]].<ref>{{cite book | last = Orr | first = Elizabeth L. |author2=William N. Orr | title = Geology of the Pacific Northwest | publisher = The McGraw-Hill Companies | year = 1996 | location = New York | page = 115 | isbn = 978-0-07-048018-6 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|publisher=USGS|url=http://vulcan.wr.usgs.gov/Volcanoes/Shasta/description_shasta.html|title=Mount Shasta and Vicinity, California|access-date=2009-10-22|archive-date=2013-02-20|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130220180039/http://vulcan.wr.usgs.gov/Volcanoes/Shasta/description_shasta.html|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

The mountain and surrounding area are part of the [[Shasta–Trinity National Forest]]. |

The mountain and surrounding area are part of the [[Shasta–Trinity National Forest]]. |

||

== Description == |

== Description == |

||

Mount Shasta is connected to its satellite cone of [[Shastina]], and together they dominate the landscape. Shasta rises abruptly to tower nearly {{convert|10000|ft|m|-3}} above its surroundings.<ref name="selters_zanger" /> On a clear winter day, the mountain can be seen from the floor of the [[Central Valley (California)|Central Valley]] {{convert|140|mi|km}} to the south.<ref>In 1878 the [[ |

The origin of the name "[[Shasta people#Origin of name|Shasta]]" is vague, either derived from a [[Shasta people|people]] of a name like it or otherwise garbled by early Westerners. Mount Shasta is connected to its satellite cone of [[Shastina]], and together they dominate the landscape. Shasta rises abruptly to tower nearly {{convert|10000|ft|m|-3}} above its surroundings.<ref name="selters_zanger" /> On a clear winter day, the mountain can be seen from the floor of the [[Central Valley (California)|Central Valley]] {{convert|140|mi|km}} to the south.<ref>In 1878 the [[United States Coast and Geodetic Survey]] triangulated between heliotropes atop Mount Shasta and Mount St. Helena, {{convert|192|mi|km}} south.</ref> The mountain has attracted the attention of poets,<ref name="Miller">{{cite book | last = Miller | first = Joaquin |author2=Malcolm Margolin |author3=Alan Rosenus | title = Life amongst the Modocs: unwritten history | publisher = Urion Press (distributed by Heyday Books) | year=1996 | orig-year = 1873 | location = Berkeley | isbn = 978-0-930588-79-3 }}</ref> authors,<ref name=muir>{{cite book|author-link=John Muir|last=Muir|first=John|year=1923|chapter=Letters, 1874–1888, of a personal nature, about Mount Shasta|editor-last=Bade|editor-first=William Frederic|title=The Life and Letters of John Muir|location=New York|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Co.|volume=II|pages=29–41, 49–50, 82–85, 219}}</ref> and presidents.<ref name=roosevelt>{{cite book|author-link=Theodore Roosevelt|last=Roosevelt|first=Theodore|chapter=Letter to Harrie Cassie Best, dated Nov. 12, 1908, White House|editor-link=George Wharton James|editor-last=James|editor-first=George Wharton|year=1930|title=Harry Cassie Best: Painter of the Yosemite Valley, California Oaks, and California Mountains|page=18}}</ref> |

||

The mountain consists of four overlapping dormant volcanic cones that have built a complex shape, including the main summit and the prominent [[satellite cone]] of {{convert|12330|ft|m|adj=on|abbr=on}} Shastina |

The mountain consists of four overlapping dormant volcanic cones that have built a complex shape, including the main summit and the prominent and visibly conical [[satellite cone]] of {{convert|12330|ft|m|adj=on|abbr=on}} Shastina. If Shastina were a separate mountain, it would rank as the fourth-highest peak of the Cascade Range (after [[Mount Rainier]], Rainier's [[Liberty Cap (Washington)|Liberty Cap]], and Mount Shasta itself).<ref name="selters_zanger" /> |

||

Mount Shasta's surface is relatively free of deep glacial [[erosion]] except, paradoxically, for its south side where Sargents |

Mount Shasta's surface is relatively free of deep glacial [[erosion]] except, paradoxically, for its south side where Sargents Ridge<ref>{{cite web | url=https://edits.nationalmap.gov/apps/gaz-domestic/public/search/names/265849 | title=Sargents Ridge | website=[[Geographic Names Information System]] | publisher=[[United States Geological Survey]] | access-date=2008-04-19 | archive-date=2023-11-04 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231104224413/https://edits.nationalmap.gov/apps/gaz-domestic/public/search/names/265849 | url-status=live }}</ref> runs parallel to the [[U-shaped valley|U-shaped]] Avalanche Gulch. This is the largest glacial valley on the volcano, although it does not now have a glacier in it. There are seven named [[glacier]]s on Mount Shasta, with the four largest ([[Whitney Glacier|Whitney]], [[Bolam Glacier|Bolam]], [[Hotlum Glacier|Hotlum]], and [[Wintun Glacier|Wintun]]) radiating down from high on the main summit cone to below {{convert|10000|ft|m|-2|abbr=on}} primarily on the north and east sides.<ref name="selters_zanger">{{cite book | last = Selters | first = Andy |author2=Michael Zanger | title = The Mount Shasta Book | edition = 3rd | publisher = [[Wilderness Press]] | year = 2006 | isbn = 978-0-89997-404-0 }}</ref> The Whitney Glacier is the longest, and the Hotlum is the most voluminous glacier in the state of California. Three of the smaller named glaciers occupy [[Cirque (landform)|cirques]] near and above {{convert|11000|ft|m|-2|abbr=on}} on the south and southeast sides, including the [[Watkins Glacier|Watkins]], [[Konwakiton Glacier|Konwakiton]], and [[Mud Creek Glacier|Mud Creek]] glaciers.{{citation needed|date=September 2012}} |

||

== History == |

== History == |

||

The oldest-known [[human settlement]] in the area dates to about 7,000 years ago.{{citation needed|date=September 2012}} |

The oldest-known [[human settlement]] in the area dates to about 7,000 years ago.{{citation needed|date=September 2012}} |

||

At the time of Euro-American contact in the |

At the time of Euro-American contact in the 1810s, the Native American tribes who lived within view of Mount Shasta included the [[Shasta people|Shasta]], [[Okwanuchu]], [[Modoc people|Modoc]], [[Achomawi]], [[Atsugewi]], [[Karuk]], [[Klamath people|Klamath]], [[Wintu]], and [[Yana people|Yana]] tribes. |

||

A historic eruption of Mount Shasta in 1786 may have been observed by [[Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse|Lapérouse]], but this is disputed. [[Smithsonian |

A historic eruption of Mount Shasta in 1786 may have been observed by [[Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse|Lapérouse]], but this is disputed. [[Smithsonian Institution]]'s [[Global Volcanism Program]] says that the 1786 eruption is discredited, and that the last known eruption of Mount Shasta was around 1250 AD, proved by uncorrected [[radiocarbon]] dating.<ref>{{cite gvp|name=Shasta: Eruptive History|vtab=Eruptions|vn=323010|access-date=2021-06-28}}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine |url=https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/californias-mount-shasta-loses-a-historical-eruption/ |title=California's Mount Shasta Loses a Historical Eruption |first=Jennifer |last=Leman |date=August 20, 2019 |magazine=[[Scientific American]] |publisher=Springer Nature America |access-date=August 5, 2021 |archive-date=July 29, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210729215332/https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/californias-mount-shasta-loses-a-historical-eruption/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

Although |

Although earlier Spanish explorers are likely to have sighted the mountain, the first written record and description was made in May 20, 1817 by Spaniard Narciso Durán, a member of the Luis Antonio Argüello expedition into the upper areas of the Sacramento River Valley, who wrote "At about ten leagues to the northwest of this place we saw the very high hill called by soldiers that went near its slope Jesus Maria, It is entirely covered with snow."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Duran |first=Narciso Fray |title=Expedition on the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers in 1817: Diary of Fray Narciso Duran. |publisher=University of California |year=1911 |language=EN |url=https://www.siskiyous.edu/library/shasta/documents/AB_Ch5.pdf}}</ref> [[Peter Skene Ogden]] (a leader of a [[Hudson's Bay Company]] trapping brigade) in 1826 recorded sighting the mountain, and in 1827, the name "Sasty" or "Sastise" was given to nearby [[Mount McLoughlin]] by Ogden.<ref>{{cite web | title = History | publisher = [[College of the Siskiyous]] | year = 1989 | url = http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/his/index.htm | access-date = 2010-03-31 | url-status = dead | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100308200255/http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/his/index.htm | archive-date = 2010-03-08 }}</ref> An 1839 map by David Burr lists the mountain as Rogers Peak.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~1614~140001:Map-of-the-United-States-Of-North-A?sort=pub_list_no_initialsort,pub_date,pub_list_no,series_no&qvq=q:Oregon;sort:pub_list_no_initialsort,pub_date,pub_list_no,series_no;lc:RUMSEY~8~1&mi=25&trs=1585|title=Map of the United States Of North America. - David Rumsey Historical Map Collection|website=www.davidrumsey.com|access-date=2018-07-02|archive-date=2018-07-02|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180702204514/https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~1614~140001:Map-of-the-United-States-Of-North-A?sort=pub_list_no_initialsort,pub_date,pub_list_no,series_no&qvq=q:Oregon;sort:pub_list_no_initialsort,pub_date,pub_list_no,series_no;lc:RUMSEY~8~1&mi=25&trs=1585|url-status=live}}</ref> This name was apparently dropped, and the name Shasta was transferred to present-day Mount Shasta in 1841, partly as a result of work by the [[United States Exploring Expedition]]. |

||

[[File:Mount Shasta Farm.jpg|thumb|left|Mount Shasta seen from south of [[Weed, California]]]] |

[[File:Mount Shasta Farm.jpg|thumb|left|Mount Shasta seen from south of [[Weed, California]]]] |

||

Beginning in the 1820s, Mount Shasta was a prominent landmark along what became known as the [[Siskiyou Trail]], which runs at Mount Shasta's base. |

Beginning in the 1820s, Mount Shasta was a prominent landmark along what became known as the [[Siskiyou Trail]], which runs at Mount Shasta's base. The Siskiyou Trail was on the track of an ancient trade and travel route of Native American footpaths between California's [[Central Valley (California)|Central Valley]] and the [[Pacific Northwest]]. |

||

The [[California Gold Rush]] brought the first Euro-American settlements into the area in the early 1850s, including at [[Yreka, California]] and [[Upper Soda Springs]]. The first recorded ascent of Mount Shasta occurred in 1854 (by Elias Pearce), after several earlier failed attempts. In 1856, the first women (Harriette Eddy, Mary Campbell McCloud, and their party) reached the summit.<ref>{{cite |

The [[California Gold Rush]] brought the first Euro-American settlements into the area in the early 1850s, including at [[Yreka, California]] and [[Upper Soda Springs]]. The first recorded ascent of Mount Shasta occurred in 1854 (by Elias Pearce), after several earlier failed attempts. In 1856, the first women (Harriette Eddy, Mary Campbell McCloud, and their party) reached the summit.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.siskiyous.edu/library/shasta/documents/upshasta.pdf |title=Up Shasta in '56 |newspaper=Sisson Mirror |date=March 18, 1897 |at=p.2 col.3 |access-date=October 4, 2014 |archive-date=October 6, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141006092024/http://www.siskiyous.edu/library/shasta/documents/upshasta.pdf |url-status=live }} The ''Shasta Courier'' reprints from its files of 1856.</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/bib/B11.htm |website=Mount Shasta Annotated Bibliography |title=Mountaineering: 19th Century |access-date=2014-10-04 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141006114702/http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/bib/B11.htm |archive-date=2014-10-06 }}</ref> |

||

[[File:King WhitneyGlacier.jpg|thumb|right|[[Clarence King]] exploring the [[Whitney Glacier]] in 1870]]By the 1860s and 1870s, Mount Shasta was the subject of scientific and literary interest. In 1854 [[John Rollin Ridge]] titled a poem "Mount Shasta." A book by California pioneer and entrepreneur [[James Mason Hutchings|James Hutchings]], titled ''Scenes of Wonder and Curiosity in California'', contained an account of an early summit trip in 1855.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/scenes_of_wonder_and_curiosity/mount_shasta.html|title=Scenes of Wonder and Curiosity in California|year=1862|first=James M|last=Hutchings|author-link=James Hutchings|access-date=2008-05-01|archive-date=2007-10-25|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071025073812/http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/scenes_of_wonder_and_curiosity/mount_shasta.html|url-status=live}}</ref> The summit was achieved (or nearly so) by [[John Muir]], [[Josiah Whitney]], [[Clarence King]], and [[John Wesley Powell]]. In 1877, Muir wrote a dramatic popular article about his surviving an overnight blizzard on Mount Shasta by lying in the hot sulfur springs near the summit.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.siskiyous.edu/library/shasta/documents/snowstormonmtshasta.pdf|title=Snow-Storm on Mount Shasta|website=siskiyous.edu|access-date=23 October 2017|archive-date=25 May 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170525094037/http://www.siskiyous.edu/library/shasta/documents/snowstormonmtshasta.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> This experience was inspiration to [[Kim Stanley Robinson]]'s short story "Muir on Shasta". |

|||

[[File:King WhitneyGlacier.jpg|thumb|right|[[Clarence King]] exploring the [[Whitney Glacier]] in 1870]] |

|||

By the 1860s and 1870s, Mount Shasta was the subject of scientific and literary interest. In 1854 [[John Rollin Ridge]] titled a poem "Mount Shasta." A book by California pioneer and entrepreneur [[James Mason Hutchings|James Hutchings]], titled ''Scenes of Wonder and Curiosity in California'', contained an account of an early summit trip in 1855.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/scenes_of_wonder_and_curiosity/mount_shasta.html|title=Scenes of Wonder and Curiosity in California|year=1862|first=James M|last=Hutchings|authorlink=James Hutchings}}</ref> The summit was achieved (or nearly so) by [[John Muir]], [[Josiah Whitney]], [[Clarence King]], and [[John Wesley Powell]]. In 1877, Muir wrote a dramatic popular article about his surviving an overnight blizzard on Mount Shasta by lying in the hot sulfur springs near the summit.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.siskiyous.edu/library/shasta/documents/snowstormonmtshasta.pdf|title=Snow-Storm on Mount Shasta|website=siskiyous.edu|accessdate=23 October 2017}}</ref> This experience was inspiration to [[Kim Stanley Robinson]]'s short story "Muir on Shasta". |

|||

The 1887 completion of the [[Central Pacific Railroad]], built along the line of the Siskiyou Trail between California and Oregon, brought a substantial increase in tourism, lumbering, and population into the area around Mount Shasta. Early resorts and hotels, such as [[Shasta Springs]] and [[Upper Soda Springs]], grew up along the Siskiyou Trail around Mount Shasta, catering to these early adventuresome tourists and mountaineers. |

The 1887 completion of the [[Central Pacific Railroad]], built along the line of the Siskiyou Trail between California and Oregon, brought a substantial increase in tourism, lumbering, and population into the area around Mount Shasta. Early resorts and hotels, such as [[Shasta Springs]] and [[Upper Soda Springs]], grew up along the Siskiyou Trail around Mount Shasta, catering to these early adventuresome tourists and mountaineers. |

||

| Line 78: | Line 79: | ||

In the early 20th century, the [[Pacific Highway (US)|Pacific Highway]] followed the track of the Siskiyou Trail to the base of Mount Shasta, leading to still more access to the mountain. Today's version of the Siskiyou Trail, [[Interstate 5]], brings thousands of people each year to Mount Shasta. |

In the early 20th century, the [[Pacific Highway (US)|Pacific Highway]] followed the track of the Siskiyou Trail to the base of Mount Shasta, leading to still more access to the mountain. Today's version of the Siskiyou Trail, [[Interstate 5]], brings thousands of people each year to Mount Shasta. |

||

From February 13–19, 1959, the [[Mount Shasta Ski Park|Mount Shasta Ski Bowl]] obtained the record for the most snowfall during one storm in the U.S., with a total of {{convert|15.75|ft|cm}}.<ref>{{cite web|title=Sierra Snowfall|website=Welcome to the Storm King|publisher=Mic Mac Publishing|date=28 January 2011|url=http://www.thestormking.com/Weather/Sierra_Snowfall/sierra_snowfall.html}}</ref> |

From February 13–19, 1959, the [[Mount Shasta Ski Park|Mount Shasta Ski Bowl]] obtained the record for the most snowfall during one storm in the U.S., with a total of {{convert|15.75|ft|cm}}.<ref>{{cite web|title=Sierra Snowfall|website=Welcome to the Storm King|publisher=Mic Mac Publishing|date=28 January 2011|url=http://www.thestormking.com/Weather/Sierra_Snowfall/sierra_snowfall.html|access-date=28 January 2011|archive-date=8 January 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110108210857/http://thestormking.com/Weather/Sierra_Snowfall/sierra_snowfall.html|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

Mount Shasta was declared a [[National Natural Landmark]] in December 1976.<ref>{{cite web |

Mount Shasta was declared a [[National Natural Landmark]] in December 1976.<ref>{{cite web| website=NPS: Nature & Science » National Natural Landmarks| title=Mount Shasta| url=http://www.nature.nps.gov/nnl/site.cfm?Site=MOSH-CA| access-date=2008-04-07| publisher=[[National Park Service]]| archive-date=2011-10-16| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111016090714/http://nature.nps.gov/nnl/site.cfm?Site=MOSH-CA| url-status=dead}}</ref> |

||

The "Shasta Gulch" is referenced in the lyrics to the 1994 song "Unfair" by cult indie rock band [[Pavement (band)|Pavement]]. |

|||

=== Legends === |

=== Legends === |

||

{{Main|Legends of Mount Shasta}} |

{{Main|Legends of Mount Shasta}} |

||

[[File:Sunrise on Mount Shasta.jpg|thumb|Sunrise |

[[File:Sunrise on Mount Shasta.jpg|thumb|Sunrise over Mount Shasta]] |

||

The lore of some of the [[Klamath Tribes]] in the area held that Mount Shasta is inhabited by the Spirit of the Above-World, Skell, who descended from heaven to the mountain's summit at the request of a Klamath chief. Skell fought with Spirit of the Below-World, Llao, who resided at [[Mount Mazama]] by throwing hot rocks and lava, probably representing the volcanic eruptions at both mountains.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://oe.oregonexplorer.info/craterlake/history.html |title=History of Crater Lake |publisher=Oregon Explorer | |

The lore of some of the [[Klamath Tribes]] in the area held that Mount Shasta is inhabited by the Spirit of the Above-World, Skell, who descended from heaven to the mountain's summit at the request of a Klamath chief. Skell fought with Spirit of the Below-World, Llao, who resided at [[Mount Mazama]] by throwing hot rocks and lava, probably representing the volcanic eruptions at both mountains.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://oe.oregonexplorer.info/craterlake/history.html |title=History of Crater Lake |publisher=Oregon Explorer |access-date=2012-04-21 |archive-date=2019-02-26 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190226011051/http://oe.oregonexplorer.info/craterlake/history.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

||

Italian settlers arrived in the early 1900s to work in the mills as stonemasons and established a strong Catholic presence in the area. |

Italian settlers arrived in the early 1900s to work in the mills as stonemasons and established a strong Catholic presence in the area. [[Mount Shasta, California|Mount Shasta City]] and [[Dunsmuir, California]], small towns near Shasta's western base, are focal points for many of these, which range from a [[Buddhism|Buddhist]] monastery ([[Shasta Abbey]], founded by [[Houn Jiyu-Kennett]] in 1971) to modern-day Native American rituals. A group of Native Americans from the [[McCloud River]] area practice rituals on the mountain.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.pbs.org/pov/inthelightofreverence/|title=In The Light of Reverence|website=POV|publisher=Public Broadcasting Service|access-date=2017-09-05|archive-date=2017-08-20|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170820185407/http://www.pbs.org/pov/inthelightofreverence/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

Mount Shasta has also been a focus for non-Native American legends, centered on a hidden city of advanced beings from the lost continent of [[Lemuria (continent)|Lemuria]].<ref name=lemuria>{{cite web|url=http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/fol/lem/index.htm|title=The Origin of the Lemurian Legend|website=Folklore of Mount Shasta|publisher=College of the Siskiyous|url-status=dead| |

Mount Shasta has also been a focus for non-Native American legends, centered on a hidden city of advanced beings from the lost continent of [[Lemuria (continent)|Lemuria]].<ref name=lemuria>{{cite web|url=http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/fol/lem/index.htm|title=The Origin of the Lemurian Legend|website=Folklore of Mount Shasta|publisher=College of the Siskiyous|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120919063057/http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/fol/lem/index.htm|archive-date=2012-09-19}}</ref> The legend grew from an offhand mention of Lemuria in the 1880s, to a description of a hidden Lemurian village in 1925. In 1931, [[Harvey Spencer Lewis]], using the pseudonym Wishar S[penle] Cerve,<ref>{{cite book|last1=Cerve|first1=Wishar S.|title=Lemuria, The Lost Continent Of the Pacific|date=1931|publisher=[[AMORC]]|at=title page|url=https://f5db1a33c5d48483c689-1033844f9683e62055e615f7d9cc8875.ssl.cf5.rackcdn.com/Lemuria%20-%20Wishar%20Cerve.pdf|access-date=2021-09-28|archive-date=2022-03-27|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220327082340/https://f5db1a33c5d48483c689-1033844f9683e62055e615f7d9cc8875.ssl.cf5.rackcdn.com/Lemuria%20-%20Wishar%20Cerve.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Melton|first1=J. Gordon|author-link1=J. Gordon Melton|title=Religious leaders of America: a biographical guide to founders and leaders of religious bodies, churches, and spiritual groups in North America|edition=2nd Revised |date= March 1999|publisher=Cengage Gale|isbn=978-0810388789|page=332}}</ref> wrote ''Lemuria: the lost continent of the Pacific'', published by [[AMORC]], about the hidden Lemurians of Mount Shasta that cemented the legend in many readers' minds.<ref name=lemuria /> |

||

In August 1987, believers in the spiritual significance of the [[Harmonic Convergence]] described Mount Shasta as one of a small number of global "power centers".<ref>{{cite web | title = Harmonic Convergence | publisher = [[College of the Siskiyous]] | year = 1989 | url = http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/fol/har/index.htm | |

In August 1987, believers in the spiritual significance of the [[Harmonic Convergence]] described Mount Shasta as one of a small number of global "power centers".<ref>{{cite web | title = Harmonic Convergence | publisher = [[College of the Siskiyous]] | year = 1989 | url = http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/fol/har/index.htm | access-date = 2010-03-31 | url-status = dead | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100527184532/http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/fol/har/index.htm | archive-date = 2010-05-27 }}</ref> Mount Shasta remains a focus of "[[New Age]]" attention.<ref>{{cite web | title = Legends: Ascended Masters | publisher = [[College of the Siskiyous]] | year = 1989 | url = http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/bib/B17.htm | access-date = 2010-03-31 | url-status = dead | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100330040045/http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/bib/B17.htm | archive-date = 2010-03-30 }}</ref> |

||

According to [[Guy Ballard]], while hiking on Mount Shasta, he encountered a man who, introducing himself as the [[Count of St. Germain]], is said to have started Ballard on the path to discovering the teachings that would become the [["I AM" Activity]] religious movement.<ref>{{cite book| title=Encyclopedia of Sacred Places |date= 2011}}</ref> |

|||

In 2009, a group of hikers were making their way up Mt. Shasta when they reported seeing a flying humanoid creature with batlike features. They described what they saw as a man “stocky as Hulk Hogan, with leathery wings fifty feet from one end to the other and the face of a bat.”<ref>{{Cite web |last=Ropers |first=Jesse |date=19 March 2022 |title=Batsquatch! A Brief History of a Local Cryptid |url=https://pacsentinel.com/batsquatch/ |access-date=3 January 2025 |website=The Pacific Sentinel}}</ref> Despite the conflicting details, both accounts have been added to the legend of Batsquatch as additional proof. |

|||

in 2024, a 20 foot bronze statue of the Virgin Mary was built in the Ski Park. The statue was built in memory of Ray Merlo, husband and business partner of the Ski Park’s owner, Robin Merlo. Ray Merlo passed away from cancer in 2020.<ref>{{Cite news |date=10 December 2024 |title=Mt. Shasta Ski Park Mother Mary statue completed |url=https://kobi5.com/news/mt-shasta-ski-park-mother-mary-statue-completed-259399/ |access-date=3 January 2025 |work=[[KOBI Television (Channel 5)]]}}</ref> |

|||

==Climate== |

|||

{{Weather box |

|||

|location = Mount Shasta 41.4096 N, 122.2001 W, Elevation: {{cvt|13396|ft}} (1991–2020 normals) |

|||

|single line = y |

|||

|Jan high F = 9.5 |

|||

|Feb high F = 12.2 |

|||

|Mar high F = 16.5 |

|||

|Apr high F = 23.8 |

|||

|May high F = 32.1 |

|||

|Jun high F = 41.0 |

|||

|Jul high F = 49.6 |

|||

|Aug high F = 49.4 |

|||

|Sep high F = 43.9 |

|||

|Oct high F = 30.8 |

|||

|Nov high F = 15.7 |

|||

|Dec high F = 8.4 |

|||

|Jan low F = -10.2 |

|||

|Feb low F = -8.0 |

|||

|Mar low F = -6.3 |

|||

|Apr low F = -2.4 |

|||

|May low F = 4.6 |

|||

|Jun low F = 11.5 |

|||

|Jul low F = 18.1 |

|||

|Aug low F = 16.5 |

|||

|Sep low F = 8.9 |

|||

|Oct low F = 1.9 |

|||

|Nov low F = -4.7 |

|||

|Dec low F = -9.6 |

|||

|precipitation colour = green |

|||

|Jan precipitation inch = 13.12 |

|||

|Feb precipitation inch = 13.3 |

|||

|Mar precipitation inch = 14.48 |

|||

|Apr precipitation inch = 7.25 |

|||

|May precipitation inch = 5.45 |

|||

|Jun precipitation inch = 3.56 |

|||

|Jul precipitation inch = 0.55 |

|||

|Aug precipitation inch = 0.42 |

|||

|Sep precipitation inch = 1.66 |

|||

|Oct precipitation inch = 10.14 |

|||

|Nov precipitation inch = 18.31 |

|||

|Dec precipitation inch = 30.21 |

|||

|source=PRISM Climate Group<ref>{{cite web|url=http://prism.oregonstate.edu/explorer/|title=PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University|publisher=PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University|quote=To find the table data on the PRISM website, start by clicking ''Coordinates'' (under ''Location''); copy ''Latitude'' and ''Longitude figures'' from top of table; click ''Zoom to location''; click ''Precipitation, Minimum temp, Mean temp, Maximum temp''; click ''30-year normals, 1991-2020''; click ''800m''; click ''Retrieve Time Series'' button.|access-date=2023-09-28|archive-date=2019-07-25|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190725164937/http://prism.oregonstate.edu/explorer/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

== Geology == |

== Geology == |

||

[[File:Mount Shasta ISS068-E-17084.jpg|thumb|Mount Shasta photographed by a crew member during the [[International Space Station]]'s [[Expedition 68|68th expedition]], in October 2022]] |

|||

[[File:MountShasta2016orthophoto-LIDARslope50.tif|thumb|2016 60 cm [[orthophoto]] mosaic overlaid on 3 m [[slope]] map (derived from [[digital elevation model]]). Scale 1:50,000.]] |

|||

About 593,000 years ago, [[andesite|andesitic]] lavas erupted in what is now Mount Shasta's western flank near McBride Spring. Over time, an ancestral Mount Shasta [[stratovolcano]] was built to a large but unknown height; sometime between 300,000 and 360,000 years ago the entire north side of the [[volcano]] collapsed, creating an enormous [[landslide]] or [[debris avalanche]], {{convert|6.5|mi3|km3|0|abbr=on}}<ref name =eov>{{cite book | last = Sigurdsson | first = Haraldur | authorlink = Haraldur Sigurdsson | title = Encyclopedia of Volcanoes | publisher = Academic Press | series = | year = 2001 | doi = | isbn = 978-0-12-643140-7 }}</ref> in volume. The slide flowed northwestward into [[Shasta Valley]], where the [[Shasta River]] now cuts through the {{convert|28|mi|km|adj=mid|-long}} flow. |

|||

About 593,000 years ago, [[andesite|andesitic]] lavas erupted in what is now Mount Shasta's western flank near McBride Spring. Over time, an ancestral Mount Shasta [[stratovolcano]] was built to a large but unknown height; sometime between 300,000 and 360,000 years ago the entire north side of the [[volcano]] collapsed, creating an enormous [[volcanic landslide|landslide]] or [[debris avalanche]], {{convert|6.5|mi3|km3|0|abbr=on}}<ref name =eov>{{cite book | last = Sigurdsson | first = Haraldur | author-link = Haraldur Sigurdsson | title = Encyclopedia of Volcanoes | publisher = Academic Press | year = 2001 | isbn = 978-0-12-643140-7 }}</ref> in volume. The slide flowed northwestward into [[Shasta Valley]], where the [[Shasta River]] now cuts through the {{convert|28|mi|km|adj=mid|-long}} flow. |

|||

What remains of the oldest of Mount Shasta's four cones is exposed at Sargents Ridge on the south side of the mountain. Lavas from the Sargents Ridge vent cover the Everitt Hill shield at Mount Shasta's southern foot. The last lavas to erupt from the vent were [[hornblende]]-[[pyroxene]] andesites with a hornblende [[dacite]] dome at its summit. Glacial erosion has since modified its shape.{{ |

What remains of the oldest of Mount Shasta's four cones is exposed at Sargents Ridge on the south side of the mountain. Lavas from the Sargents Ridge vent cover the Everitt Hill shield at Mount Shasta's southern foot. The last lavas to erupt from the vent were [[hornblende]]-[[pyroxene]] andesites with a hornblende [[dacite]] dome at its summit. Glacial erosion has since modified its shape.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Christiansen |first1=Robert L. |last2=Calvert |first2=Andrew T. |last3=Champion |first3=Duane E. |last4=Gardner |first4=Cynthia A. |last5=Fierstein |first5=Judith E. |last6=Vazquez |first6=Jorge A. |date=2020-08-10 |title=The remarkable volcanism of Shastina, a stratocone segment of Mount Shasta, California |journal=Geosphere |volume=16 |issue=5 |pages=1153–1178 |doi=10.1130/GES02080.1 |issn=1553-040X|doi-access=free |bibcode=2020Geosp..16.1153C }}</ref> |

||

The next cone to form is exposed south of Mount Shasta's current summit and is called Misery Hill. It was formed 15,000 to 20,000 years ago from pyroxene andesite flows and has since been intruded by a hornblende dacite dome.{{citation needed|date=September 2012}} |

The next cone to form is exposed south of Mount Shasta's current summit and is called Misery Hill. It was formed 15,000 to 20,000 years ago from pyroxene andesite flows and has since been intruded by a hornblende dacite dome.{{citation needed|date=September 2012}} |

||

[[File:Black Butte from Weed, California-750px.jpg|thumb|Nearby [[Black Butte (California)|Black Butte]], seen from Weed, California]] |

[[File:Black Butte from Weed, California-750px.jpg|thumb|Nearby [[Black Butte (Siskiyou County, California)|Black Butte]], seen from Weed, California]] |

||

There are many buried glacial scars on the mountain |

There are many buried glacial scars on the mountain that were created in recent glacial periods ("ice ages") of the present [[Wisconsin glaciation|Wisconsinian glaciation]]. Most have since been filled in with [[andesite]] [[lava]], [[pyroclastic flow]]s, and [[Scree|talus]] from lava domes. Shastina, by comparison, has a fully intact summit crater indicating Shastina developed after the [[Last glacial period|last ice age]]. Shastina has been built by mostly pyroxene andesite lava flows. Some 9,500 years ago, these flows reached about {{convert|6.8|mi|km|abbr=on}} south and {{convert|3|mi|km|abbr=on}} north of the area now occupied by nearby [[Black Butte (Siskiyou County, California)|Black Butte]]. The last eruptions formed Shastina's present summit about a hundred years later. But before that, Shastina, along with the then forming Black Butte dacite [[plug dome]] complex to the west, created numerous pyroclastic flows that covered {{convert|43|mi2|km2|abbr=on}}, including large parts of what is now [[Mount Shasta, California]] and [[Weed, California]]. Diller Canyon ({{convert|400|ft|m|-1|abbr=on|disp=or}} deep and {{convert|0.25|mi|m|abbr=on|disp=or}} wide) is an avalanche chute that was probably carved into Shastina's western face by these flows.{{citation needed|date=September 2012}} |

||

The last to form, and the highest cone, the Hotlum Cone, formed about 8,000 years ago. It is named after the Hotlum glacier on its northern face; its longest lava flow, the {{convert|500|ft|m|-thick|abbr= |

The last to form, and the highest cone, the Hotlum Cone, formed about 8,000 years ago. It is named after the Hotlum glacier on its northern face; its longest lava flow, the {{convert|500|ft|m|-thick|abbr=|sp=us|adj=mid|-1}} Military Pass flow, extends {{convert|5.5|mi|km|abbr=on}} down its northeast face. Since the creation of the Hotlum Cone, a dacite dome intruded the cone and now forms the summit. The rock at the {{convert|600|ft|m|-wide|abbr=|sp=us|adj=mid|-1}} summit crater has been extensively hydrothermally altered by sulfurous [[hot spring]]s and [[fumarole]]s there (only a few examples still remain).{{citation needed|date=September 2012}} |

||

In the last 8,000 years, the Hotlum Cone has erupted at least eight or nine times. About 200 years ago the last significant Mount Shasta eruption came from this cone and created a pyroclastic flow, a hot [[lahar]] (mudflow), and three cold lahars, which streamed {{convert|7.5|mi|km|abbr=on}} down Mount Shasta's east flank via Ash Creek. A separate hot lahar went {{convert|12|mi|km|abbr=on}} down Mud Creek. This eruption was thought to have been observed by the explorer [[Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse|La Pérouse]], from his ship off the California coast, in 1786, but this has been disputed.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/his/ |website=Mount Shasta Companion |title=History | |

In the last 8,000 years, the Hotlum Cone has erupted at least eight or nine times. About 200 years ago, the last significant Mount Shasta eruption came from this cone and created a pyroclastic flow, a hot [[lahar]] (mudflow), and three cold lahars, which streamed {{convert|7.5|mi|km|abbr=on}} down Mount Shasta's east flank via Ash Creek. A separate hot lahar went {{convert|12|mi|km|abbr=on}} down Mud Creek. This eruption was thought to have been observed by the explorer [[Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse|La Pérouse]], from his ship off the California coast, in 1786, but this has been disputed.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/his/ |website=Mount Shasta Companion |title=History |access-date=2010-03-31 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100829195745/http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/his/ |archive-date=2010-08-29 }}</ref> |

||

=== Volcanic status === |

=== Volcanic status === |

||

During the last 10,000 years, Mount Shasta has erupted an average of every 800 years, but in the past 4,500 years the volcano has erupted an average of every 600 years |

During the last 10,000 years, Mount Shasta has erupted an average of every 800 years, but in the past 4,500 years the volcano has erupted an average of every 600 years.<ref name="gvp " /> |

||

[[File:Diller Canyon.jpg|thumb|left|upright=1.25|Diller Canyon on Shastina from Weed]] |

[[File:Diller Canyon.jpg|thumb|left|upright=1.25|Diller Canyon on Shastina from Weed]] |

||

USGS seismometers and GPS receivers operated by UNAVCO form the monitoring network for Mount Shasta. The volcano has been relatively quiet |

USGS seismometers and GPS receivers operated by UNAVCO form the monitoring network for Mount Shasta. The volcano has been relatively quiet during the 21st century, with only a handful of small magnitude earthquakes and no demonstrable [[Deformation (volcanology)|ground deformation]]. Although geophysically quiet, periodic geochemical surveys indicate that volcanic gas emanates from a fumarole at the summit of Mount Shasta from a deep-seated reservoir of partly molten rock.<ref>https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/sir20185159|California’s Exposure to Volcanic Hazards Scientific Investigations Report 2018-5159 Prepared in cooperation with the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services and the California Geological Surve</ref> |

||

[[File:Mount Shasta west face.jpg|thumb|right|Mount Shasta's west face as seen from Hidden Valley high on the mountain. The west face gulley is an alternate climbing route to the summit.]] |

[[File:Mount Shasta west face.jpg|thumb|right|Mount Shasta's west face as seen from Hidden Valley high on the mountain. The west face gulley is an alternate climbing route to the summit.]] |

||

Mount Shasta can release [[volcanic ash]], |

Mount Shasta can release [[volcanic ash]], pyroclastic flows or [[dacite]] and [[andesite]] [[lava]]. Its deposits can be detected under nearby small towns. Mount Shasta has an explosive, eruptive history. There are [[fumarole]]s on the mountain, which show Mount Shasta is still alive.{{citation needed|date=September 2012}} |

||

The worst-case scenario for an eruption is a large pyroclastic flow, similar to that which occurred in the [[1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens]]. Since there is ice, such as [[Whitney Glacier]] and [[Mud Creek Glacier]], [[lahar]]s would also result. |

The worst-case scenario for an eruption is a large pyroclastic flow, similar to that which occurred in the [[1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens]]. Since there is ice, such as [[Whitney Glacier]] and [[Mud Creek Glacier]], [[lahar]]s would also result. |

||

The [[United States Geological Survey]] monitors |

The [[United States Geological Survey]] monitors Mount Shasta<ref>{{cite web|url=https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/volcanoes/mount_shasta/mount_shasta_monitoring_4.html|title=USGS: Volcano Hazards Program CalVO Mount Shasta|first=Volcano Hazards|last=Program|website=volcanoes.usgs.gov|access-date=23 October 2017|archive-date=11 July 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170711191818/https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/volcanoes/mount_shasta/mount_shasta_monitoring_4.html|url-status=live}}</ref> and rates it as a very high-threat volcano.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2005/1164/2005-1164.pdf|title=An Assessment of Volcanic Threat and Monitoring Capabilities in the United States: NVEWS Framework for a National Volcano Early Warning System|year=2005|publisher=USGS|access-date=2013-07-08|archive-date=2012-07-12|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120712175227/http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2005/1164/2005-1164.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

== Climbing == |

== Climbing == |

||

[[File:Shasta boulab.jpg|thumb|right|upright|Mount Shasta's west face, June 2009]] |

[[File:Shasta boulab.jpg|thumb|right|upright|Mount Shasta's west face, June 2009]] |

||

The summer climbing season runs from late April until October, although many attempts are made in the winter.<ref name="selters_zanger" /> |

The summer climbing season runs from late April until October, although many attempts are made in the winter.<ref name="selters_zanger" /> Mount Shasta is also a popular destination for [[backcountry skiing]]. Many of the climbing routes can be descended by experienced skiers, and there are numerous lower-angled areas around the base of the mountain.<ref name="selters_zanger" /> |

||

No quota system currently exists for climbing Mount Shasta, and reservations are not required. However, climbers must obtain a summit pass and a wilderness permit to climb the mountain.<ref>{{cite web| url = http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/stnf/home/?cid=stelprdb5353013| title = Mount Shasta Wilderness Permits and Summit Passes| publisher = U.S. Forest Service| access-date = 2014-01-26| archive-date = 2014-02-04| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140204042734/http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/stnf/home/?cid=stelprdb5353013| url-status = live}}</ref> |

|||

The most popular route on Mount Shasta is Avalanche Gulch route, which begins at the Bunny Flat Trailhead and gains about {{convert|7300|ft}} of elevation in approximately {{convert|11.5|mi}} round trip. The crux of this route is considered to be to climb from Lake Helen, at approximately {{convert|10443|ft}}, to the top of Red Banks. The Red Banks are the most technical portion of the climb, as they are usually full of snow/ice, are very steep, and top out at around {{convert|13000|ft}} before the route heads to Misery Hill.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.shastaavalanche.org/general-route-description/avalanche-gulch |

|||

| title = Avalanche Gulch |

|||

| publisher = Mount Shasta Avalanche Center |

|||

| accessdate = 2016-02-17}}</ref> |

|||

The Casaval Ridge route is a steeper, more technical route on the mountain's southwest ridge best climbed when there's a lot of snow pack. This route tops out to the left (north) of the Red Banks, directly west of Misery Hill. So the final sections involve a trudge up Misery Hill to the summit plateau, similar to the Avalanche Gulch route.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.summitpost.org/casaval-ridge/155538 |

|||

| title = Casaval Ridge |

|||

| publisher = SummitPost |

|||

| accessdate = 2014-02-16}}</ref> |

|||

No quota system currently exists for climbing Mount Shasta, and reservations are not required. However, climbers must obtain a summit pass and a wilderness permit to climb the mountain. Permits and passes are available at the ranger station in Mount Shasta and the ranger station in McCloud, or climbers can obtain self-issue permits and passes at any of the trailheads 24 hours a day.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/stnf/home/?cid=stelprdb5353013 |

|||

| title = Mount Shasta Wilderness Permits and Summit Passes |

|||

| publisher = U.S. Forest Service |

|||

| accessdate = 2014-01-26 }}</ref> |

|||

==Notable people== |

|||

*Jack Trout, Entrepreneur, Historian, Writer, Northern California celebrity & personality, famous worldwide fly fishing guide & outfitter. Started Rambow Worms at age 16 in Portola. Born in Portola 1967. Graduate of Portola High School. Appeared on a series of [[ESPN]] Fly Fishing Shows in the 1990's & Early 2000, Was featured on KNBR 680 SF, The Fishing Hole on Sundays. Currently resides in Mount Shasta, California. News contributor for the Plumas News, Mountain Messenger, Sierra Booster & other publications throughout California. Author Fodors Travel Books Chile & Argentina. Mystery Writer Dianne Harman wrote two books about Jack Trout solving murder mysteries on his fly fishing trips worldwide, one called Murder In Cuba & A Best Seller on Amazon called, [https://www.amazon.com/Murdered-Argentina-Jack-Trout-Mystery-ebook/dp/B01IO3T9HE Murdered In Argentina]. <ref>https://cdlib.org/cdlinfo/2014/03/06/hathitrust-a-gold-mine-for-researchers/ Jack Trout Saddle Ridge Gold Coin Mystery.]Retrieved March 6, 2014</ref><ref>[https://www.sfgate.com/sports/article/The-secret-to-success-on-the-Upper-Sac-A-guy-2915198.php The secret to success on the Upper Sac / A guy named Trout knows how to land the best river trout.]Retrieved Thursday, May 31, 2001.</ref><ref>https://www.plumasnews.com/how-the-winter-west-was-won/ How The Winter West Was Won Snowshoe Thompson]Retrieved December 18, 2018.</ref><ref>[https://www.plumasnews.com/eastern-plumas-offers-visitors-lots-to-do/]Retrieved July 24, 2019.</ref> <ref>[https://www.amazon.com/Murdered-Argentina-Jack-Trout-Mystery-ebook/dp/B01IO3T9HE </ref>] |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

* [[List of mountain peaks of California]] |

* [[List of mountain peaks of California]] |

||

* [[List of |

* [[List of California fourteeners]] |

||

* [[List of California county high points]] |

|||

* [[List of Ultras of the United States]] |

* [[List of Ultras of the United States]] |

||

* [[List of volcanoes in the United States]] |

* [[List of volcanoes in the United States]] |

||

| Line 161: | Line 201: | ||

* {{cite journal|last= Crandell |first= D. R. |author2=C. D. Miller |author3=H. X. Glicken |author4=R. L. Christiansen |author5=C. G. Newhall |date= March 1984 |title= Catastrophic debris avalanche from ancestral Mount Shasta volcano, California |journal= Geology |volume= 12 |issue= 3 |pages=143–146 |

* {{cite journal|last= Crandell |first= D. R. |author2=C. D. Miller |author3=H. X. Glicken |author4=R. L. Christiansen |author5=C. G. Newhall |date= March 1984 |title= Catastrophic debris avalanche from ancestral Mount Shasta volcano, California |journal= Geology |volume= 12 |issue= 3 |pages=143–146 |

||

|doi = 10.1130/0091-7613(1984)12<143:CDAFAM>2.0.CO;2 |issn= 0091-7613 |bibcode = 1984Geo....12..143C }} |

|doi = 10.1130/0091-7613(1984)12<143:CDAFAM>2.0.CO;2 |issn= 0091-7613 |bibcode = 1984Geo....12..143C }} |

||

* {{cite book |author1=Crandell, D.R. |author2=Nichols, D.R. |title=Volcanic hazards at Mount Shasta, California |publisher=U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey |location=Reston, VA |year=1987 |

* {{cite book |author1=Crandell, D.R. |author2=Nichols, D.R. |title=Volcanic hazards at Mount Shasta, California |publisher=U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey |location=Reston, VA |year=1987 }} |

||

* {{cite book | last = Harris | first = Stephen L. | title = Fire Mountains of the West: The Cascade and Mono Lake Volcanoes |edition=3rd | publisher = [[Mountain Press Publishing Company]] | year = 2005 | isbn = 978-0-87842-511-2 }} |

* {{cite book | last = Harris | first = Stephen L. | title = Fire Mountains of the West: The Cascade and Mono Lake Volcanoes |edition=3rd | publisher = [[Mountain Press Publishing Company]] | year = 2005 | isbn = 978-0-87842-511-2 }} |

||

* Lamson, Berenice (1984). "[https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/2111/ Mount Shasta : a regional history]". ''University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations'': 140. |

* Lamson, Berenice (1984). "[https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/2111/ Mount Shasta : a regional history]". ''University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations'': 140. |

||

* {{cite web |url=http://www.siskiyous.edu/library/Shasta/index.htm |publisher=College of the Siskiyous Library|title=Mount Shasta Collection | |

* {{cite web |url=http://www.siskiyous.edu/library/Shasta/index.htm |publisher=College of the Siskiyous Library|title=Mount Shasta Collection |access-date=2012-04-21}} |

||

* {{cite web|url=http://www.siskiyous.edu/library/shasta/factsheet| |

* {{cite web|url=http://www.siskiyous.edu/library/shasta/factsheet|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051103133841/http://www.siskiyous.edu/library/shasta/factsheet/|author=Miesse, William C.|title=Mount Shasta Fact Sheet|access-date=2006-02-11|archive-date=2005-11-03|publisher=College of the Siskiyous Library|date=June 17, 2005}} |

||

* {{cite web|website=Mount Shasta Annotated Bibliography|title=The Name 'Shasta'|author=Miesse, William C|url=http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/bib/B14.htm| |

* {{cite web|website=Mount Shasta Annotated Bibliography|title=The Name 'Shasta'|author=Miesse, William C|url=http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/bib/B14.htm|access-date=2006-02-11|publisher=College of the Siskiyous Library|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060515120955/http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/bib/B14.htm|archive-date=2006-05-15}} |

||

* {{cite book |author1=Peterson, Robyn |author2=Miesse, William C. |title=Sudden and solitary: Mount Shasta and its artistic legacy, 1841–2008 |publisher=Turtle Bay Exploration Park |location=Redding |year=2008 |

* {{cite book |author1=Peterson, Robyn |author2=Miesse, William C. |title=Sudden and solitary: Mount Shasta and its artistic legacy, 1841–2008 |publisher=Turtle Bay Exploration Park |location=Redding |year=2008 |isbn=978-1-59714-088-1 |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/suddensolitarymo00mies }} |

||

* {{cite web |url=http://www.diggles.com/pgs/2001/PGS_Field_Trip_2001.pdf |title=Peninsula Geological Society and Stanford GES-052Q combined field trip, Mount Shasta–Klamathnorthern Coast Range area, NW California, 05/17–05/20/2001 |

* {{cite web |url=http://www.diggles.com/pgs/2001/PGS_Field_Trip_2001.pdf |title=Peninsula Geological Society and Stanford GES-052Q combined field trip, Mount Shasta–Klamathnorthern Coast Range area, NW California, 05/17–05/20/2001 |publisher=Peninsula Geological Society |access-date=2012-04-21}} |

||

* {{cite book | editor1-last = Wood | editor1-first = Charles A. | editor2-first= Jürgen |editor2-last = Kienle | title = Volcanoes of North America | publisher = [[Cambridge University Press]] | year = 1990 | isbn = 978-0-521-43811-7 }} |

* {{cite book | editor1-last = Wood | editor1-first = Charles A. | editor2-first= Jürgen |editor2-last = Kienle | title = Volcanoes of North America | publisher = [[Cambridge University Press]] | year = 1990 | isbn = 978-0-521-43811-7 }} |

||

* {{cite book | last = Zanger | first = Michael | title = Mount Shasta: History, Legend, Lore | publisher = Celestial Arts | year = 1992 | isbn = 978-0-89087-674-9 }} |

* {{cite book | last = Zanger | first = Michael | title = Mount Shasta: History, Legend, Lore | publisher = Celestial Arts | year = 1992 | isbn = 978-0-89087-674-9 }} |

||

| Line 174: | Line 214: | ||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

{{Commons and category |Mount Shasta |Mount Shasta}} |

{{Commons and category |Mount Shasta |Mount Shasta}} |

||

* {{cite web |url=http://www.snowcrest.net/camera/ |title=Live webcam |publisher=SnowCrest Inc. | |

* {{cite web |url=http://www.snowcrest.net/camera/ |title=Live webcam |publisher=SnowCrest Inc. |access-date=2019-05-03}} |

||

* {{cite web |url=http://www.mountshastasissonmuseum.org/index.htm |title=Sisson Museum | |

* {{cite web |url=http://www.mountshastasissonmuseum.org/index.htm |title=Sisson Museum |access-date=2011-05-08 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090202193715/http://www.mountshastasissonmuseum.org/index.htm |archive-date=2009-02-02 }} |

||

* {{cite summitpost |id=150188 |name=Mount Shasta | |

* {{cite summitpost |id=150188 |name=Mount Shasta |access-date=2011-05-07}} |

||

* {{cite bivouac |id=9144 |name=Mount Shasta | |

* {{cite bivouac |id=9144 |name=Mount Shasta |access-date=2011-05-07}} |

||

* {{cite web |url=http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/geo/ |title=Geology of Mount Shasta |publisher=College of the Siskiyous | |

* {{cite web |url=http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/geo/ |title=Geology of Mount Shasta |publisher=College of the Siskiyous |access-date=2011-05-08 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110629185147/http://www.siskiyous.edu/shasta/geo/ |archive-date=2011-06-29 }} |

||

* {{cite web |url=http://vimeo.com/12878599| |

* {{cite web |url=http://vimeo.com/12878599|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100707095329/http://vimeo.com/12878599|archive-date=2010-07-07 |title=Summiting the Volcano |publisher=Vimeo.com |access-date=2011-05-08}} |

||

* {{cite web |url=http://vimeo.com/8138267 |title=Land of the Giants |publisher=Vimeo.com | |

* {{cite web |url=http://vimeo.com/8138267 |title=Land of the Giants |date=12 December 2009 |publisher=Vimeo.com |access-date=2011-05-08}} |

||

* {{cite web |url=http://www.timberlinetrails.net/ShastaAboveRedBanks.html |title=Mount Shasta Climbing Above Red Banks |publisher=Timberline Trails | |

* {{cite web |url=http://www.timberlinetrails.net/ShastaAboveRedBanks.html |title=Mount Shasta Climbing Above Red Banks |publisher=Timberline Trails |access-date=2011-05-08 |archive-date=2014-07-02 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140702163347/http://timberlinetrails.net/ShastaAboveRedBanks.html |url-status=dead }} |

||

* "[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qt64AOPyK5M&t=3s Mt. Shasta Climb-Clear Creek Route]" YouTube.com 18 Aug 2016 |

|||

* [http://volcano.si.edu/volcano.cfm?vn=323010 Smithsonian Institute, Global Volcanism Program, Shasta]: volcano information |

|||

{{NA highest}}{{NA prominent}}{{NA isolated}} |

|||

{{navboxes top}} |

|||

{{NA highest}} |

|||

{{NA prominent}} |

|||

{{NA isolated}} |

|||

{{California highest}} |

{{California highest}} |

||

{{California Fourteeners}} |

{{California Fourteeners}} |

||

{{Volcanoes of California}} |

|||

{{Glaciers of Mount Shasta|nocat=1}} |

{{Glaciers of Mount Shasta|nocat=1}} |

||

{{Cascade volcanoes}} |

{{Cascade volcanoes}} |

||

{{California}} |

{{California}} |

||

{{navboxes bottom}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Shasta, Mount}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Shasta, Mount}} |

||

[[Category:Mount Shasta| ]] |

[[Category:Mount Shasta| ]] |

||

| Line 198: | Line 245: | ||

[[Category:National Natural Landmarks in California]] |

[[Category:National Natural Landmarks in California]] |

||

[[Category:Native American mythology of California|Mount Shasta]] |

[[Category:Native American mythology of California|Mount Shasta]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Dormant volcanoes]] |

||

[[Category:Potentially active volcanoes]] |

|||

[[Category:Protected areas of Siskiyou County, California]] |

[[Category:Protected areas of Siskiyou County, California]] |

||

[[Category:Religious places of the |

[[Category:Religious places of the Indigenous peoples of North America|Shasta]] |

||

[[Category:Sacred mountains]] |

[[Category:Sacred mountains of the Americas]] |

||

[[Category:Shasta-Trinity National Forest]] |

[[Category:Shasta-Trinity National Forest]] |

||

[[Category:Stratovolcanoes of the United States]] |

[[Category:Stratovolcanoes of the United States]] |

||

| Line 209: | Line 255: | ||

[[Category:Volcanoes of Siskiyou County, California]] |

[[Category:Volcanoes of Siskiyou County, California]] |

||

[[Category:Shastan languages]] |

[[Category:Shastan languages]] |

||

[[Category:Locations in Native American mythology]] |

|||

[[Category:Stratovolcanoes of California]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 05:58, 6 January 2025

| Mount Shasta | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Mount Shasta from the southwest | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 14,179 ft (4,322 m)[1] NAVD88 |

| Prominence | 9,772 ft (2,979 m)[2] |

| Parent peak | North Palisade[2] |

| Isolation | 335 mi (539 km)[2] |

| Listing | |

| Coordinates | 41°24′33″N 122°11′42″W / 41.409196033°N 122.194888358°W[1] |

| Naming | |

| Native name | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Shasta–Trinity National Forest, California, U.S. |

| Parent range | Cascade Range |

| Topo map | USGS Mount Shasta |

| Geology | |

| Rock age | About 593,000 years |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Volcanic arc | Cascade Volcanic Arc |

| Last eruption | 1250[3] |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1854 by E. D. Pearce and party[4] |

| Easiest route | Avalanche Gulch ("John Muir") route: talus/snow climb[4] |

| Designated | 1976 |

Mount Shasta (/ˈʃæstə/ SHASS-tə; Shasta: Waka-nunee-Tuki-wuki;[5] Karuk: Úytaahkoo)[6] is a potentially active[7] stratovolcano at the southern end of the Cascade Range in Siskiyou County, California. At an elevation of 14,179 ft (4,322 m), it is the second-highest peak in the Cascades and the fifth-highest in the state. Mount Shasta has an estimated volume of 85 cubic miles (350 cubic kilometers), which makes it the most voluminous volcano in the Cascade Volcanic Arc.[8][9] The mountain and surrounding area are part of the Shasta–Trinity National Forest.

Description

[edit]The origin of the name "Shasta" is vague, either derived from a people of a name like it or otherwise garbled by early Westerners. Mount Shasta is connected to its satellite cone of Shastina, and together they dominate the landscape. Shasta rises abruptly to tower nearly 10,000 feet (3,000 m) above its surroundings.[4] On a clear winter day, the mountain can be seen from the floor of the Central Valley 140 miles (230 km) to the south.[10] The mountain has attracted the attention of poets,[11] authors,[12] and presidents.[13]

The mountain consists of four overlapping dormant volcanic cones that have built a complex shape, including the main summit and the prominent and visibly conical satellite cone of 12,330 ft (3,760 m) Shastina. If Shastina were a separate mountain, it would rank as the fourth-highest peak of the Cascade Range (after Mount Rainier, Rainier's Liberty Cap, and Mount Shasta itself).[4]

Mount Shasta's surface is relatively free of deep glacial erosion except, paradoxically, for its south side where Sargents Ridge[14] runs parallel to the U-shaped Avalanche Gulch. This is the largest glacial valley on the volcano, although it does not now have a glacier in it. There are seven named glaciers on Mount Shasta, with the four largest (Whitney, Bolam, Hotlum, and Wintun) radiating down from high on the main summit cone to below 10,000 ft (3,000 m) primarily on the north and east sides.[4] The Whitney Glacier is the longest, and the Hotlum is the most voluminous glacier in the state of California. Three of the smaller named glaciers occupy cirques near and above 11,000 ft (3,400 m) on the south and southeast sides, including the Watkins, Konwakiton, and Mud Creek glaciers.[citation needed]

History

[edit]The oldest-known human settlement in the area dates to about 7,000 years ago.[citation needed]

At the time of Euro-American contact in the 1810s, the Native American tribes who lived within view of Mount Shasta included the Shasta, Okwanuchu, Modoc, Achomawi, Atsugewi, Karuk, Klamath, Wintu, and Yana tribes.

A historic eruption of Mount Shasta in 1786 may have been observed by Lapérouse, but this is disputed. Smithsonian Institution's Global Volcanism Program says that the 1786 eruption is discredited, and that the last known eruption of Mount Shasta was around 1250 AD, proved by uncorrected radiocarbon dating.[15][16]

Although earlier Spanish explorers are likely to have sighted the mountain, the first written record and description was made in May 20, 1817 by Spaniard Narciso Durán, a member of the Luis Antonio Argüello expedition into the upper areas of the Sacramento River Valley, who wrote "At about ten leagues to the northwest of this place we saw the very high hill called by soldiers that went near its slope Jesus Maria, It is entirely covered with snow."[17] Peter Skene Ogden (a leader of a Hudson's Bay Company trapping brigade) in 1826 recorded sighting the mountain, and in 1827, the name "Sasty" or "Sastise" was given to nearby Mount McLoughlin by Ogden.[18] An 1839 map by David Burr lists the mountain as Rogers Peak.[19] This name was apparently dropped, and the name Shasta was transferred to present-day Mount Shasta in 1841, partly as a result of work by the United States Exploring Expedition.

Beginning in the 1820s, Mount Shasta was a prominent landmark along what became known as the Siskiyou Trail, which runs at Mount Shasta's base. The Siskiyou Trail was on the track of an ancient trade and travel route of Native American footpaths between California's Central Valley and the Pacific Northwest.

The California Gold Rush brought the first Euro-American settlements into the area in the early 1850s, including at Yreka, California and Upper Soda Springs. The first recorded ascent of Mount Shasta occurred in 1854 (by Elias Pearce), after several earlier failed attempts. In 1856, the first women (Harriette Eddy, Mary Campbell McCloud, and their party) reached the summit.[20][21]

By the 1860s and 1870s, Mount Shasta was the subject of scientific and literary interest. In 1854 John Rollin Ridge titled a poem "Mount Shasta." A book by California pioneer and entrepreneur James Hutchings, titled Scenes of Wonder and Curiosity in California, contained an account of an early summit trip in 1855.[22] The summit was achieved (or nearly so) by John Muir, Josiah Whitney, Clarence King, and John Wesley Powell. In 1877, Muir wrote a dramatic popular article about his surviving an overnight blizzard on Mount Shasta by lying in the hot sulfur springs near the summit.[23] This experience was inspiration to Kim Stanley Robinson's short story "Muir on Shasta".

The 1887 completion of the Central Pacific Railroad, built along the line of the Siskiyou Trail between California and Oregon, brought a substantial increase in tourism, lumbering, and population into the area around Mount Shasta. Early resorts and hotels, such as Shasta Springs and Upper Soda Springs, grew up along the Siskiyou Trail around Mount Shasta, catering to these early adventuresome tourists and mountaineers.

In the early 20th century, the Pacific Highway followed the track of the Siskiyou Trail to the base of Mount Shasta, leading to still more access to the mountain. Today's version of the Siskiyou Trail, Interstate 5, brings thousands of people each year to Mount Shasta.

From February 13–19, 1959, the Mount Shasta Ski Bowl obtained the record for the most snowfall during one storm in the U.S., with a total of 15.75 feet (480 cm).[24]

Mount Shasta was declared a National Natural Landmark in December 1976.[25]

The "Shasta Gulch" is referenced in the lyrics to the 1994 song "Unfair" by cult indie rock band Pavement.

Legends

[edit]

The lore of some of the Klamath Tribes in the area held that Mount Shasta is inhabited by the Spirit of the Above-World, Skell, who descended from heaven to the mountain's summit at the request of a Klamath chief. Skell fought with Spirit of the Below-World, Llao, who resided at Mount Mazama by throwing hot rocks and lava, probably representing the volcanic eruptions at both mountains.[26]

Italian settlers arrived in the early 1900s to work in the mills as stonemasons and established a strong Catholic presence in the area. Mount Shasta City and Dunsmuir, California, small towns near Shasta's western base, are focal points for many of these, which range from a Buddhist monastery (Shasta Abbey, founded by Houn Jiyu-Kennett in 1971) to modern-day Native American rituals. A group of Native Americans from the McCloud River area practice rituals on the mountain.[27]

Mount Shasta has also been a focus for non-Native American legends, centered on a hidden city of advanced beings from the lost continent of Lemuria.[28] The legend grew from an offhand mention of Lemuria in the 1880s, to a description of a hidden Lemurian village in 1925. In 1931, Harvey Spencer Lewis, using the pseudonym Wishar S[penle] Cerve,[29][30] wrote Lemuria: the lost continent of the Pacific, published by AMORC, about the hidden Lemurians of Mount Shasta that cemented the legend in many readers' minds.[28]

In August 1987, believers in the spiritual significance of the Harmonic Convergence described Mount Shasta as one of a small number of global "power centers".[31] Mount Shasta remains a focus of "New Age" attention.[32]

According to Guy Ballard, while hiking on Mount Shasta, he encountered a man who, introducing himself as the Count of St. Germain, is said to have started Ballard on the path to discovering the teachings that would become the "I AM" Activity religious movement.[33]

In 2009, a group of hikers were making their way up Mt. Shasta when they reported seeing a flying humanoid creature with batlike features. They described what they saw as a man “stocky as Hulk Hogan, with leathery wings fifty feet from one end to the other and the face of a bat.”[34] Despite the conflicting details, both accounts have been added to the legend of Batsquatch as additional proof.

in 2024, a 20 foot bronze statue of the Virgin Mary was built in the Ski Park. The statue was built in memory of Ray Merlo, husband and business partner of the Ski Park’s owner, Robin Merlo. Ray Merlo passed away from cancer in 2020.[35]

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Mount Shasta 41.4096 N, 122.2001 W, Elevation: 13,396 ft (4,083 m) (1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 9.5 (−12.5) |

12.2 (−11.0) |

16.5 (−8.6) |

23.8 (−4.6) |

32.1 (0.1) |

41.0 (5.0) |

49.6 (9.8) |

49.4 (9.7) |

43.9 (6.6) |

30.8 (−0.7) |

15.7 (−9.1) |

8.4 (−13.1) |

27.7 (−2.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | −10.2 (−23.4) |

−8.0 (−22.2) |

−6.3 (−21.3) |

−2.4 (−19.1) |

4.6 (−15.2) |

11.5 (−11.4) |

18.1 (−7.7) |

16.5 (−8.6) |

8.9 (−12.8) |

1.9 (−16.7) |

−4.7 (−20.4) |

−9.6 (−23.1) |

1.7 (−16.8) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 13.12 (333) |

13.3 (340) |

14.48 (368) |

7.25 (184) |

5.45 (138) |

3.56 (90) |

0.55 (14) |

0.42 (11) |

1.66 (42) |

10.14 (258) |

18.31 (465) |

30.21 (767) |

118.45 (3,010) |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group[36] | |||||||||||||

Geology

[edit]

About 593,000 years ago, andesitic lavas erupted in what is now Mount Shasta's western flank near McBride Spring. Over time, an ancestral Mount Shasta stratovolcano was built to a large but unknown height; sometime between 300,000 and 360,000 years ago the entire north side of the volcano collapsed, creating an enormous landslide or debris avalanche, 6.5 cu mi (27 km3)[37] in volume. The slide flowed northwestward into Shasta Valley, where the Shasta River now cuts through the 28-mile-long (45 km) flow.

What remains of the oldest of Mount Shasta's four cones is exposed at Sargents Ridge on the south side of the mountain. Lavas from the Sargents Ridge vent cover the Everitt Hill shield at Mount Shasta's southern foot. The last lavas to erupt from the vent were hornblende-pyroxene andesites with a hornblende dacite dome at its summit. Glacial erosion has since modified its shape.[38]

The next cone to form is exposed south of Mount Shasta's current summit and is called Misery Hill. It was formed 15,000 to 20,000 years ago from pyroxene andesite flows and has since been intruded by a hornblende dacite dome.[citation needed]

There are many buried glacial scars on the mountain that were created in recent glacial periods ("ice ages") of the present Wisconsinian glaciation. Most have since been filled in with andesite lava, pyroclastic flows, and talus from lava domes. Shastina, by comparison, has a fully intact summit crater indicating Shastina developed after the last ice age. Shastina has been built by mostly pyroxene andesite lava flows. Some 9,500 years ago, these flows reached about 6.8 mi (10.9 km) south and 3 mi (4.8 km) north of the area now occupied by nearby Black Butte. The last eruptions formed Shastina's present summit about a hundred years later. But before that, Shastina, along with the then forming Black Butte dacite plug dome complex to the west, created numerous pyroclastic flows that covered 43 sq mi (110 km2), including large parts of what is now Mount Shasta, California and Weed, California. Diller Canyon (400 ft or 120 m deep and 0.25 mi or 400 m wide) is an avalanche chute that was probably carved into Shastina's western face by these flows.[citation needed]

The last to form, and the highest cone, the Hotlum Cone, formed about 8,000 years ago. It is named after the Hotlum glacier on its northern face; its longest lava flow, the 500-foot-thick (150 m) Military Pass flow, extends 5.5 mi (8.9 km) down its northeast face. Since the creation of the Hotlum Cone, a dacite dome intruded the cone and now forms the summit. The rock at the 600-foot-wide (180 m) summit crater has been extensively hydrothermally altered by sulfurous hot springs and fumaroles there (only a few examples still remain).[citation needed]

In the last 8,000 years, the Hotlum Cone has erupted at least eight or nine times. About 200 years ago, the last significant Mount Shasta eruption came from this cone and created a pyroclastic flow, a hot lahar (mudflow), and three cold lahars, which streamed 7.5 mi (12.1 km) down Mount Shasta's east flank via Ash Creek. A separate hot lahar went 12 mi (19 km) down Mud Creek. This eruption was thought to have been observed by the explorer La Pérouse, from his ship off the California coast, in 1786, but this has been disputed.[39]