Sanaa: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Undid revision 1267786791 by 178.202.191.71 (talk): That isn't a government type? |

||

| (327 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Capital and largest city of Yemen}} |

|||

{{other uses|Sanaa (disambiguation)}} |

|||

{{EngvarB|date=April 2021}} |

|||

{{short description|the largest city in yemen}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2024}} |

|||

{{Other uses}} |

|||

{{Infobox settlement |

{{Infobox settlement |

||

<!--See the Table at Infobox settlement for all fields and descriptions of usage--> |

<!--See the Table at Infobox settlement for all fields and descriptions of usage.--> |

||

<!-- Basic info ----------------> |

<!-- Basic info ---------------->| name = Sanaa |

||

| native_name = {{Script/Arabic|صَنْعَاء}} |

|||

|name = Sanaa |

|||

| nickname = ʾAmānat Al-ʿĀṣimah ({{Script/Arabic|أَمَانَة ٱلْعَاصِمَة}}) |

|||

| |

| other_name = |

||

| settlement_type = [[Capital city]] |

|||

|nickname =أمانة العاصمة |

|||

| |

| motto = <!-- images and maps -----------> |

||

| |

| image_skyline = {{multiple image |

||

| total_width = 290 |

|||

<!-- images and maps -----------> |

|||

| |

| border = infobox |

||

| perrow = 1/2/2 |

|||

| photo1a = Sanaa, Yemen (7).jpg |

|||

| caption_align = center |

|||

| photo2a = Alsalh-24-2-2014 (16481824622).jpg |

|||

| |

| image1 = Banner Sana (esVoy).jpg |

||

| caption1 = The skyline of the [[Old City of Sanaa]] |

|||

| photo3a = Bab-ul-Yemen, Sana'a (2286002741).jpg |

|||

| image2 = Sana'a (2286825748).jpg |

|||

| photo3b = The entrance of National Museum in Sana'a.JPG |

|||

| caption2 = Houses in the old city |

|||

| size = 275 |

|||

| image3 = Al Saleh Mosque - Sana'a 2013.jpg |

|||

| spacing = 2 |

|||

| caption3 = [[Al-Saleh Mosque]] |

|||

| color = transparent |

|||

| image4 = PluieSanaa.JPG |

|||

| border = 0 |

|||

| caption4 = Rainy day in Sanaa |

|||

| image5 = Bab-ul-Yemen, Sana'a (2286002741).jpg |

|||

| caption5 = [[Bab al Yemen]] |

|||

| image6 = National Museum of Yemen.jpg |

|||

| caption6 = [[National Museum of Yemen]] |

|||

| image7 = Al-Bakirya Mosque, Sana'a (2286904368).jpg |

|||

| caption7 = [[Al-Bakiriyya Mosque]] |

|||

| image8 = Sanaa - aser (16294882888).jpg|Sanaa - aser (16294882888) |

|||

| caption8 =View of Sanaa |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

| image_caption = |

|||

|image_caption = Clockwise from top:<br /> Sanaʽa skyline, the Old City, [[National Museum of Yemen]], [[Bab al-Yaman]], [[Al Saleh Mosque]] |

|||

|image_flag |

| image_flag = |

||

|flag_size |

| flag_size = |

||

|image_seal |

| image_seal = |

||

|seal_size |

| seal_size = |

||

|image_shield |

| image_shield = |

||

|shield_size |

| shield_size = |

||

|image_blank_emblem |

| image_blank_emblem = |

||

|blank_emblem_type |

| blank_emblem_type = |

||

|blank_emblem_size |

| blank_emblem_size = |

||

|image_map |

| image_map = Sana'a City Map.png |

||

|mapsize |

| mapsize = |

||

|map_caption |

| map_caption = Map of the city |

||

| |

| image_map1 = Amanat Al Asimah in Yemen.svg |

||

| map_caption1 = Sanaa in the [[Yemen|Republic of Yemen]] |

|||

|pushpin_label_position = right |

|||

| |

| pushpin_map = Yemen#West Asia |

||

| pushpin_label_position = right |

|||

|pushpin_mapsize = |

|||

| |

| pushpin_relief = yes |

||

| pushpin_mapsize = |

|||

<!-- Location ------------------> |

|||

| pushpin_map_caption = <!-- Location ------------------> |

|||

|subdivision_type = [[List of sovereign states|Country]] |

|||

| subdivision_type = [[List of sovereign states|Country]] |

|||

|subdivision_name = {{YEM}} |

|||

| subdivision_name = {{flag|Yemen}} |

|||

|subdivision_type1 = Administrative division |

|||

| subdivision_type1 = [[Governorates of Yemen|Governorate]] |

|||

|subdivision_name1 = Capital's secretariat |

|||

| subdivision_name1 = Amanat Al-Asemah |

|||

|subdivision_type2 = |

|||

| subdivision_type2 = |

|||

|subdivision_name2 = |

|||

| subdivision_name2 = |

|||

| parts_type = [[Yemeni Crisis (2011–present)|Occupation]] |

|||

<!-- Politics ----------------->| government_footnotes = |

|||

| parts_style = para |

|||

| government_type = |

|||

| p1 = {{flagicon image|Houthis Logo.png}} [[Houthis]] |

|||

| leader_title = |

|||

<!-- Politics -----------------> |

|||

| leader_name = |

|||

|government_footnotes = |

|||

| leader_title1 = <!-- for places with, say, both a mayor and a city manager --> |

|||

|government_type = Local |

|||

| |

| leader_name1 = |

||

| |

| leader_title2 = |

||

| leader_name2 = |

|||

|leader_title1 = <!-- for places with, say, both a mayor and a city manager --> |

|||

| established_title = <!-- Settled --> |

|||

|leader_name1 = |

|||

| established_date = |

|||

|leader_title2 = |

|||

| established_title2 = <!-- Incorporated (town) --> |

|||

|leader_name2 = |

|||

| established_date2 = |

|||

|established_title = <!-- Settled --> |

|||

| established_title3 = <!-- Incorporated (city) --> |

|||

|established_date = |

|||

| established_date3 = 1167 |

|||

|established_title2 = <!-- Incorporated (town) --> |

|||

<!-- Area --------------------->| area_magnitude = |

|||

|established_date2 = |

|||

| |

| unit_pref = <!--Enter: Imperial, if Imperial (metric) is desired --> |

||

| |

| area_footnotes = |

||

| area_total_km2 = 126<!-- ALL fields dealing with measurements are subject to automatic unit conversion--> |

|||

<!-- Area ---------------------> |

|||

| area_land_km2 = <!--See table Template:Infobox settlement for details on automatic unit conversion--> |

|||

|area_magnitude = |

|||

| area_water_km2 = |

|||

|unit_pref = <!--Enter: Imperial, if Imperial (metric) is desired--> |

|||

| area_total_sq_mi = |

|||

|area_footnotes = |

|||

| area_land_sq_mi = |

|||

|area_total_km2 = 126<!-- ALL fields dealing with a measurements are subject to automatic unit conversion--> |

|||

| area_water_sq_mi = |

|||

|area_land_km2 = <!--See table @ Template:Infobox settlement for details on automatic unit conversion--> |

|||

| area_water_percent = |

|||

|area_water_km2 = |

|||

| area_urban_km2 = |

|||

|area_total_sq_mi = |

|||

| area_urban_sq_mi = |

|||

|area_land_sq_mi = |

|||

| area_metro_km2 = |

|||

|area_water_sq_mi = |

|||

| area_metro_sq_mi = |

|||

|area_water_percent = |

|||

| area_blank1_title = |

|||

|area_urban_km2 = |

|||

| area_blank1_km2 = |

|||

|area_urban_sq_mi = |

|||

| area_blank1_sq_mi = <!-- Population -----------------------> |

|||

|area_metro_km2 = |

|||

| population_as_of = 2017 |

|||

|area_metro_sq_mi = |

|||

| population_footnotes = <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cso-yemen.com/content.php?lng=english&id=690|title=Yemen Statistical Yearbook 2017|author=Central Statistics Organization|access-date=31 August 2020|archive-date=20 January 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210120130028/http://www.cso-yemen.com/content.php?lng=english&id=690|url-status=usurped}}</ref> |

|||

|area_blank1_title = |

|||

| population_note = |

|||

|area_blank1_km2 = |

|||

| population_total = 2,545,000 {{increase}} |

|||

|area_blank1_sq_mi = |

|||

| population_density_km2 = 20320 |

|||

<!-- Population -----------------------> |

|||

| population_density_sq_mi = |

|||

|population_as_of = 2012 |

|||

| population_metro = |

|||

|population_footnotes = |

|||

| population_density_metro_km2 = |

|||

|population_note = |

|||

| population_density_metro_sq_mi = |

|||

|population_total = 3,937,451 |

|||

| population_blank1_title = Ethnicities |

|||

|population_density_km2 = |

|||

| population_blank1 = |

|||

|population_density_sq_mi = |

|||

| population_blank2_title = Religions |

|||

|population_metro = 4,167,961 |

|||

| population_blank2 = |

|||

|population_density_metro_km2 = |

|||

| population_density_blank1_km2 = |

|||

|population_density_metro_sq_mi = |

|||

| population_density_blank1_sq_mi = <!-- General information ---------------> |

|||

|population_urban = |

|||

| population_demonym = Sanaani, San'ani |

|||

|population_density_urban_km2 = |

|||

| timezone = [[Arabia Standard Time]] |

|||

|population_density_urban_sq_mi = |

|||

| |

| utc_offset = +03:00 |

||

| |

| timezone_DST = (Not Observed) |

||

| coordinates = {{coord|15|20|54|N|44|12|23|E|region:YE|display=inline,title}} |

|||

|population_blank2_title = Religions |

|||

| elevation_footnotes = <!--for references: use tags--> |

|||

|population_blank2 = |

|||

| elevation_m = 2250 |

|||

|population_density_blank1_km2 = |

|||

| elevation_ft = <!-- Area/postal codes & others --------> |

|||

|population_density_blank1_sq_mi = |

|||

| postal_code_type = <!-- enter ZIP code, Postcode, postal code... --> |

|||

<!-- General information ---------------> |

|||

| postal_code = |

|||

|timezone = [[Arabia Standard Time|AST]] |

|||

| |

| area_code = |

||

| |

| blank_name = |

||

| |

| blank_info = |

||

| website = |

|||

|coordinates = {{coord|15|20|54|N|44|12|23|E|region:YE|display=inline,title}} |

|||

| footnotes = |

|||

|elevation_footnotes = <!--for references: use tags--> |

|||

| official_name = Sanaa Municipality<br/>{{Langx|ar|أَمَانَة ٱلْعَاصِمَة|ʾAmānat al-ʿĀṣimah}} |

|||

|elevation_m = 2250 |

|||

| population_est = 3,407,814 {{increase}} |

|||

|elevation_ft = |

|||

| pop_est_as_of = 2024 |

|||

<!-- Area/postal codes & others --------> |

|||

| pop_est_footnotes = <ref>{{cite web | url=https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/sanaa-population | title=Sanaa Population 2024 }}</ref> |

|||

|postal_code_type = <!-- enter ZIP code, Postcode, Post code, Postal code... --> |

|||

|postal_code = |

|||

|area_code = |

|||

|blank_name = |

|||

|blank_info = |

|||

|website = |

|||

|footnotes = |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Sanaa''' |

'''Sanaa''',{{efn|{{IPAc-en|s|ə|ˈ|n|ɑː}} {{respell|sə|NAH}}; {{langx|ar|{{Script/Arabic|صَنْعَاء}}}}, ''{{transliteration|ar|Ṣanʿāʾ}}'' {{IPA|ar|sˤɑnʕaːʔ|}}, <small>[[Yemeni Arabic]]:</small> {{IPA|ar|ˈsˤɑnʕɑ|}}; [[Ancient South Arabian script|Old South Arabian]]: 𐩮𐩬𐩲𐩥 ''Ṣnʿw''}}{{efn|also spelled '''Sana'a''' and '''Sana'''}} officially the '''Sanaa Municipality''',{{efn|{{langx|ar|{{Script/Arabic|أَمَانَة ٱلْعَاصِمَة}}|ʾAmānat al-ʿĀṣimah}}}} is the capital and largest [[List of cities in Yemen|city]] of [[Yemen]]. The city is the capital of the [[Sanaa Governorate]], but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. According to the [[Constitution of Yemen|Yemeni constitution]], Sanaa is the capital of the country,<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.dpa-international.com/news/international/yemens-embattled-president-declares-southern-base-temporary-capital-a-44650685-img-2.html|agency=DPA International|title=Yemen's embattled president declares southern base temporary capital|date=21 March 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150711155806/http://www.dpa-international.com/news/international/yemens-embattled-president-declares-southern-base-temporary-capital-a-44650685-img-2.html|archive-date=11 July 2015|url-status=dead}}</ref> although the seat of the Yemeni government moved to [[Aden]], the former capital of [[Democratic Yemen]], in the aftermath of the [[Houthi takeover in Yemen|Houthi occupation]]. Aden was declared the temporary capital by then-president [[Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi]] in March 2015.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.dw.de/yemens-president-hadi-declares-new-temporary-capital/a-18332197|agency={{Lang|de|Deutsche Welle}}|title=Yemen's President Hadi declares new 'temporary capital'|date=21 March 2015|access-date=21 March 2015|archive-date=5 June 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150605210805/http://www.dw.de/yemens-president-hadi-declares-new-temporary-capital/a-18332197|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

At an elevation of {{convert|2300|m|ft}},<ref name="Laughlin2008">{{cite book |last=McLaughlin |first=Daniel |title=Yemen |publisher=[[Bradt Travel Guides]] |chapter=3: Sanaʽa |page=67 |isbn=978-1-8416-2212-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eQvhZaEVzjcC&q=jabal+nuqum |year=2008 |access-date=26 September 2020 |archive-date=14 February 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230214213150/https://books.google.com/books?id=eQvhZaEVzjcC&q=jabal+nuqum |url-status=live }}</ref> Sanaa is one of the highest capital cities in the world and is next to the [[Sarawat Mountains]] of [[Jabal An-Nabi Shu'ayb]] and [[Jabal Tiyal]], considered to be the highest mountains in the [[Arabian Peninsula]] and one of the highest in the [[Middle East|region]]. Sanaa has a population of approximately 3,292,497 (2023), making it Yemen's largest city.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Sanaa Population 2023 |url=https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/sanaa-population |access-date=2023-08-14 |website=worldpopulationreview.com}}</ref> As of 2020, the greater Sanaa urban area makes up about 10% of Yemen's total population.<ref name="UN-Habitat">{{cite book |last1= |url=https://yemenportal.unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/01-Sanaa-City-Profile.pdf |title=Sana'a City Profile |date=2020 |publisher=United Nations Human Settlements Programme in Yemen |access-date=27 February 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210414041009/https://yemenportal.unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/01-Sanaa-City-Profile.pdf |archive-date=14 April 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

The Old City of |

The Old City of Sanaa, a [[UNESCO]] [[World Heritage Site]], has a distinctive architectural character, most notably expressed in its multi-story buildings decorated with geometric patterns. The [[Al Saleh Mosque]], the largest in the country, is located in the southern outskirts of the city. During the [[Yemeni civil war (2014–present)|conflict]] that raged in 2015, explosives hit UNESCO sites in the old city.<ref>{{cite web|last=Young|first=T. Luke|title=Conservation of the Old Walled City of Sanaʽa Republic of Yemen|url=http://web.mit.edu/akpia/www/AKPsite/4.239/sanaa/yemen.html|publisher=MIT|access-date=7 April 2011|archive-date=3 August 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180803125725/http://web.mit.edu/akpia/www/AKPsite/4.239/sanaa/yemen.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="HestlerSpilling2010">{{cite book|author1=Anna Hestler|author2=Jo-Ann Spilling|title=Yemen|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JNJiTaTaEocC&pg=PA16|year=2010|publisher=Marshall Cavendish|isbn=978-0-7614-4850-1|page=16|access-date=15 November 2015|archive-date=14 February 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230214213152/https://books.google.com/books?id=JNJiTaTaEocC&pg=PA16|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

Sanaa has been facing a long-term severe [[Water supply and sanitation in Yemen|water crisis]] {{asof|2023|lc=y}},<ref>{{Cite news |title=Yemen facing water shortage crisis |language=en-GB |work=BBC News |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/world-middle-east-23777176 |access-date=2023-04-16}}</ref> with water being drawn from its aquifer three times faster than it is replenished. The city is predicted to completely run out of water by around 2030,{{according to whom|date=December 2024}} making it the first national capital in the world to do so. Access to drinking water is very limited in Sanaa, and there are problems with water quality.<ref name="Al-Hamdi">{{cite book |last1=Al-Hamdi |first1=Mohamed I |title=Competition for Scarce Groundwater in the Sana'a Plain, Yemen. A Study of the Incentive Systems for Urban and Agricultural Water Use. |date=2000 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=90-5410-426-0 |pages=1–8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eOCcu2VAfDQC |access-date=15 February 2021}}</ref> |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

{{see also|Timeline of |

{{see also|Timeline of Sanaa}} |

||

===Ancient period=== |

===Ancient period=== |

||

According to |

According to [[Islam|Islamic]] sources, Sanaa was founded at the base of the mountains of [[Jabal Nuqum]]<ref name="Laughlin2008"/> by [[Shem]], the son of [[Noah]],<ref>Al-Hamdāni, al-Ḥasan ibn Aḥmad, ''The Antiquities of South Arabia: The Eighth Book of Al-Iklīl'', Oxford University Press 1938, pp. 8–9</ref><ref>Minaret Building and Apprenticeship in Yemen, by Trevor Marchand, Routledge (27 April 2001), p. 1.</ref><ref name="Aithe30">Aithe, p. 30.</ref> after the latter's death. |

||

The name ''Sanaa'' is probably derived from the [[Sabaic]] root ''ṣnʿ'', meaning "well-fortified".<ref name="Smith 1997">{{cite book |last1=Smith |first1=G.R. |editor1-last=Bosworth |editor1-first=C.E. |editor2-last=van Donzel |editor2-first=E. |editor3-last=Heinrichs |editor3-first=W.P. |editor4-last=Lecomte |editor4-first=G. |title=The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol. IX (SAN-SZE) |date=1997 |publisher=Brill |location=Leiden |isbn=90-04-10422-4 |pages=1–3 |url=https://ia600603.us.archive.org/14/items/EncyclopaediaDictionaryIslamMuslimWorldEtcGibbKramerScholars.13/09.EncycIslam.NewEdPrepNumLeadOrient.EdEdComCon.BosDonHeinLec.etc.UndPatIUA.v9.San-Sze.Leid.EJBrill.1997..pdf |access-date=18 March 2022 |chapter=ṢANʿĀʾ}}</ref><ref name="Bosworth">{{cite book |last1=Bosworth |first1=C. Edmund |title=Historic Cities of the Islamic World |date=2007 |publisher=BRILL |isbn=9789047423836 |page=462 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CgawCQAAQBAJ&q=Sanaa+name+in+the+6th+century+yemen&pg=PA462 |language=en |access-date=16 October 2020 |archive-date=14 April 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210414084059/https://books.google.com/books?id=CgawCQAAQBAJ&q=Sanaa+name+in+the+6th+century+yemen&pg=PA462 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>Albert Jamme, inscriptions from Mahram Bilqis, p. 440.</ref> The name is attested in old Sabaean inscriptions, mostly from the 3rd century CE, as '''''ṣnʿw'''''.<ref name="Smith 1997"/> In the present day, a popular [[folk etymology]] says that the name ''Sanaa'' refers to "the excellence of its trades and crafts (perhaps the feminine form of the Arabic adjective ''aṣnaʿ'')".<ref name="Smith 1997"/> |

|||

The 10th-century [[Arab]] historian [[Abū Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdānī|al-Hamdani]] wrote that Sanaa's ancient name was '''''Azāl''''', which is not recorded in any contemporary Sabaean inscriptions.<ref name="Smith 1997"/> The name "Azal" has been connected to [[Uzal]], a son of [[Qahtanite|Qahtan]], a great-grandson of Shem, in the [[Bible|biblical]] accounts of the [[Book of Genesis]].<ref name=EB>{{cite EB1911|wstitle=Sana |volume=24 |pages=125–126}}</ref> |

|||

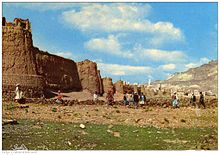

[[File:Sanaa old25.jpg|thumb|The walls of Sana'a in the 1950s]] |

|||

Al-Hamdani wrote that Sanaa was walled by the [[Sabaeans]] under their ruler [[Sha'r Awtar]], who also arguably built the [[Ghumdan Palace]] in the city. Because of its location, Sanaa has served as an urban hub for the surrounding tribes of the region and as a nucleus of regional trade in [[South Arabia|southern Arabia]]. It was positioned at the crossroad of two major ancient trade routes linking [[Ma'rib]] in the east to the [[Red Sea]] in the west.<ref name="Aithe30"/> |

|||

Appropriately enough for a town whose name means "well-fortified", Sanaa appears to have been an important military center under the Sabaeans.<ref name="Smith 1997"/> They used it as a base for their expeditions against the kingdom of [[Himyar]] further south, and several inscriptions "announce a triumphant return to Sanaa from the wars."<ref name="Smith 1997"/> Sanaa is referred to in these inscriptions both as a town (''hgr'') and as a ''maram'' (''mrm''), which, according to A. F. L. Beeston, indicates "a place to which access is prohibited or restricted, no matter whether for religious or for other reasons".<ref name="Smith 1997"/> The Sabaean inscriptions also mention the Ghumdan Palace by name.<ref name="Smith 1997"/> |

|||

The [[Arab]] historian [[Abū Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdānī|al-Hamdani]] wrote that Sanaʽa was walled by the [[Sabaeans]] under their ruler [[Sha'r Awtar]], who also arguably built the [[Ghumdan Palace]] in the city. Because of its location, Sanaʽa has served as an urban center for the surrounding tribes of the region, and as a nucleus of regional trade in [[South Arabia|southern Arabia]]. It was positioned at the crossroad of two major ancient trade routes linking [[Ma'rib]] in the east to the [[Red Sea]] in the west.<ref name="Aithe30"/> |

|||

When King Yousef Athar (or [[Dhu Nuwas]]), the last of the Himyarite kings, was in power, Sanaʽa was also the capital of the [[Kingdom of Aksum| |

When King Yousef Athar (or [[Dhu Nuwas]]), the last of the Himyarite kings, was in power, Sanaʽa was also the capital of the [[Kingdom of Aksum|Axumite]] viceroys.{{citation needed|date=March 2022}} Later tradition also holds that the [[Abyssinia]]n conqueror [[Abrahah]] built a Christian church in Sanaa.<ref name="Smith 1997"/> |

||

===Islamic era=== |

===Islamic era=== |

||

[[File:SanaaQuoranDoubleVersions.jpg|thumb|The [[Sanaʽa manuscript]], found in Sanaʽa in 1972, is one of the oldest [[Qur'an|Quranic]] manuscripts in existence]] |

[[File:SanaaQuoranDoubleVersions.jpg|thumb|The [[Sanaʽa manuscript]], found in Sanaʽa in 1972, is one of the oldest [[Qur'an|Quranic]] manuscripts in existence.]] |

||

From the era of [[Muhammad]] (ca. 622 CE) until the founding of independent sub-states in many parts of the Yemen Islamic [[Caliph]]ate, |

From the era of [[Muhammad]] (ca. 622 CE) until the founding of independent sub-states in many parts of the Yemen Islamic [[Caliph]]ate, Sanaa persisted as the governing seat. The [[Caliph]]'s deputy ran the affairs of one of Yemen's three [[Makhalif]]: Mikhlaf Sanaʽa, Mikhlaf [[Janad Region|al-Janad]], and Mikhlaf [[Hadhramaut]]. The city of Sanaa regularly regained an important status, and all Yemenite States competed to control it.{{citation needed|date=March 2019}} |

||

Imam [[Al-Shafi'i]], the 8th-century Islamic jurist and founder of the [[Shafi'i]] school of jurisprudence, visited |

Imam [[Al-Shafi'i]], the 8th-century Islamic jurist and founder of the [[Shafi'i]] school of jurisprudence, visited Sanaa several times. He praised the city, writing ''La budda min Ṣanʻāʼ'', or "Sanaa must be seen." In the 9th–10th centuries, it was written of the city that "the Yem separate from each other, empty of ordure, without smell or evil smells, because of the hard concrete [<nowiki/>[[adobe]] and [[Cob (material)|cob]], probably] and fine pastureland and clean places to walk." Later in the 10th-century, the Persian geographer [[Ibn Rustah]] wrote of Sanaa, "It is the city of Yemen; there cannot be found ... a city greater, more populous or more prosperous, of nobler origin or with more delicious food than it." |

||

In 1062 |

In 1062, Sanaa was taken over by the [[Sulayhid dynasty]] led by [[Ali al-Sulayhi]] and his wife, the popular [[Asma bint Shihab|Queen Asma]]. He made the city capital of his relatively small kingdom, which also included the [[Jabal Haraz|Haraz Mountains]]. The Sulayhids were aligned with the [[Ismaili Muslim]]-leaning [[Fatimid Caliphate]] of Egypt, rather than the [[Baghdad]]-based [[Abbasid Caliphate]] that most of [[Arabia]] followed. Al-Sulayhi ruled for about 20 years but he was assassinated by his principal local rivals, the [[Zabid]]-based Najahids. Following his death, al-Sulayhi's daughter, [[Arwa al-Sulayhi]], inherited the throne. She withdrew from Sanaa, transferring the Sulayhid capital to [[Jibla, Yemen|Jibla]], where she ruled much of Yemen from 1067 to 1138. As a result of the Sulayhid departure, the [[Hamdanids (Yemen)|Hamdanid]] dynasty took control of Sanaʽa.<ref name="McLaughlin16">McLaughlin, p. 16.</ref> Like the Sulayhids, the Hamdanids were Isma'ilis.<ref name="Smith 1997"/> |

||

In 1173 [[Saladin]], the [[Ayyubid]] sultan of Egypt, sent his brother [[Turan-Shah]] on an expedition to conquer Yemen. The Ayyubids gained control of Sanaʽa in 1175 and united the various Yemeni tribal states, except for the northern mountains controlled by the [[Zaydi]] imams, into one entity.<ref name="McLaughlin16"/> The Ayyubids switched the country's official religious allegiance to the [[Sunni Muslim]] Abbasids. During the reign of the Ayyubid ''[[emir]]'' Tughtekin ibn Ayyub, the city underwent significant improvements. These included the incorporation of the garden lands on the western bank of the Sa'ilah, known as Bustan al-Sultan, where the Ayyubids built one of their palaces.<ref>Elsheshtawy, p.92.</ref> |

In 1173, [[Saladin]], the [[Ayyubid]] sultan of Egypt, sent his brother [[Turan-Shah]] on an expedition to conquer Yemen. The Ayyubids gained control of Sanaʽa in 1175 and united the various Yemeni tribal states, except for the northern mountains controlled by the [[Zaydi]] imams, into one entity.<ref name="McLaughlin16"/> The Ayyubids switched the country's official religious allegiance to the [[Sunni Muslim]] Abbasids. During the reign of the Ayyubid ''[[emir]]'' Tughtekin ibn Ayyub, the city underwent significant improvements. These included the incorporation of the garden lands on the western bank of the Sa'ilah, known as Bustan al-Sultan, where the Ayyubids built one of their palaces.<ref>Elsheshtawy, p. 92.</ref> However, Ayyubid control of Sanaa was never very consistent, and they only occasionally exercised direct authority over the city.<ref name="Smith 1997"/> Instead, they chose [[Ta'izz]] as their capital, while [[Aden]] was their principal income-producing city. |

||

While the [[Rasulid]]s controlled most of Yemen, followed by their successors the [[ |

While the [[Rasulid]]s controlled most of Yemen, followed by their successors, the [[Tahirids (Yemen)|Tahirids]], Sanaa largely remained in the political orbit of the [[Zaydi]] imams from 1323 to 1454 and outside the former two dynasties' rule.<ref name="Bosworth463">Bosworth, p. 463.</ref> The [[Mamelukes]] arrived in Yemen in 1517. |

||

===Ottoman era=== |

===Ottoman era=== |

||

[[File:San'a şehir haritası (1874).png|thumb|Ottoman map of Sanaa, 1874]] |

|||

The [[Ottoman Empire]] entered Yemen in 1538 when [[Suleiman the Magnificent]] was [[Sultan]].<ref name="Dumper330"/> Under the military leadership of [[Özdemir Pasha]], the Ottomans conquered Sanaʽa in 1547.<ref name="Bosworth463"/> With Ottoman approval, European captains based in the Yemeni port towns of [[Aden]] and [[Mocha, Yemen|Mocha]] frequented Sanaʽa to maintain special privileges and capitulations for their trade. In 1602 the local Zaydi imams led by [[Al-Mu'ayyad Muhammad|Imam al-Mu'ayyad]] reasserted their control over the area,<ref name="Dumper330"/> and forced out Ottoman troops in 1629. Although the Ottomans fled during al-Mu'ayyad's reign, his predecessor [[al-Mansur al-Qasim]] had already vastly weakened the Ottoman army in Sanaʽa and Yemen.<ref name="Bosworth463"/> Consequently, European traders were stripped of their previous privileges.<ref name="Dumper330">Dumper, p.330.</ref> |

|||

The [[Ottoman Empire]] entered Yemen in 1538, when [[Suleiman the Magnificent]] was [[Sultan]].<ref name="Dumper330"/> Under the military leadership of [[Özdemir Pasha]], the Ottomans conquered Sanaa in 1547.<ref name="Bosworth463"/> With Ottoman approval, European captains based in the Yemeni port towns of [[Aden]] and [[Mocha, Yemen|Mocha]] frequented Sanaa to maintain special privileges and capitulations for their trade. In 1602, the local Zaydi imams led by [[Al-Mu'ayyad Muhammad|Imam al-Mu'ayyad]] reasserted their control over the area,<ref name="Dumper330"/> and forced out Ottoman troops in 1629. Although the Ottomans fled during al-Mu'ayyad's reign, his predecessor [[al-Mansur al-Qasim]] had already vastly weakened the Ottoman army in Sanaʽa and Yemen.<ref name="Bosworth463"/> Consequently, European traders were stripped of their previous privileges.<ref name="Dumper330">Dumper, p. 330.</ref> |

|||

The Zaydi imams maintained their rule over |

The Zaydi imams maintained their rule over Sanaa until the mid-19th century when the Ottomans relaunched their campaign to control the region. In 1835, Ottoman troops arrived on the Yemeni coast under the guise of [[Muhammad Ali of Egypt]]'s troops.<ref name="Dumper330"/> They did not capture Sanaa until 1872, when their troops led by [[Ahmed Muhtar Pasha]] entered the city.<ref name="Bosworth463"/> The Ottoman Empire instituted the [[Tanzimat]] reforms throughout the lands they governed. |

||

In |

In Sanaa, city planning was initiated for the first time, new roads were built, and schools and hospitals were established. The reforms were rushed by the Ottomans to solidify their control of Sanaʽa to compete with an expanding [[Egypt]], British influence in [[Aden]], and imperial Italian and French influence along the coast of [[Somalia]], particularly in the towns of [[Djibouti]] and [[Berbera]]. The modernization reforms in Sanaa were still very limited, however.<ref name="Dumper331"/> |

||

===North Yemen period=== |

===North Yemen period=== |

||

[[File:Dar al hajar edit.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Dar al-Hajar]], the residence of [[Imam Yahya]] in the Wādī Ẓahr ({{lang|ar|وادى ظهر}}) near Sanaʽa]] |

[[File:Dar al hajar edit.jpg|thumb|upright|left|[[Dar al-Hajar]], the residence of [[Yahya Muhammad Hamid ed-Din|Imam Yahya]] in the [[Wadi Zahr|Wādī Ẓahr]] ({{lang|ar|وادى ظهر}}) near Sanaʽa]] |

||

In 1904, as Ottoman influence was waning in Yemen, [[Yahya Muhammad Hamid ed-Din|Imam Yahya]] of the [[ |

In 1904, as Ottoman influence was waning in Yemen, [[Yahya Muhammad Hamid ed-Din|Imam Yahya]] of the [[Zaydism|Zaydi]] [[Imams of Yemen|Imam]]s took power in Sanaa. In a bid to secure [[Kingdom of Yemen|North Yemen]]'s independence, Yahya embarked on a policy of isolationism, avoiding international and Arab world politics, cracking down on embryonic liberal movements, not contributing to the development of infrastructure in Sanaa and elsewhere and closing down the Ottoman girls' school. As a consequence of Yahya's measures, Sanaa increasingly became a hub of anti-government organization and intellectual revolt.<ref name="Dumper331">Dumper, p. 331.</ref> |

||

In the 1930s, several organizations opposing or demanding reform of the Zaydi imamate sprung up in the city, particularly Fatat al-Fulayhi, a group of various Yemeni [[Muslim scholars]] based in Sanaʽa's Fulayhi Madrasa, and Hait al-Nidal ("Committee of the Struggle.") By 1936 most of the leaders of these movements were imprisoned. In 1941 another group based in the city, the Shabab al-Amr bil-Maruf wal-Nahian al-Munkar, called for a ''[[nahda]]'' ("renaissance") in the country as well as the establishment of a parliament with Islam |

In the 1930s, several organizations opposing or demanding reform of the Zaydi imamate sprung up in the city, particularly Fatat al-Fulayhi, a group of various Yemeni [[Muslim scholars]] based in Sanaʽa's Fulayhi Madrasa, and Hait al-Nidal ("Committee of the Struggle.") By 1936, most of the leaders of these movements were imprisoned. In 1941, another group based in the city, the Shabab al-Amr bil-Maruf wal-Nahian al-Munkar, called for a ''[[nahda]]'' ("renaissance") in the country as well as the establishment of a parliament with Islam as the instrument of Yemeni revival. Yahya largely repressed the Shabab and most of its leaders were executed following his son [[Ahmad bin Yahya|Imam Ahmad]]'s inheritance of power in 1948.<ref name="Dumper331"/> That year, Sanaa was replaced with [[Ta'izz]] as capital following Ahmad's new residence there. Most government offices followed suit. A few years later, most of the city's Jewish population emigrated to Israel.<ref name="R&S631"/> |

||

Ahmad began a process of gradual economic and political liberalization, but by 1961 |

Ahmad began a process of gradual economic and political liberalization, but by 1961, Sanaa was witnessing major demonstrations and riots demanding quicker reform and change. Pro-republican officers in the North Yemeni military sympathetic of [[Gamal Abdel Nasser]] of [[Egypt]]'s government and [[pan-Arabism|pan-Arabist]] policies staged a coup overthrowing the Imamate government in September 1962, a week after Ahmad's death.<ref name="Dumper331"/> Sanaa's role as a capital was restored afterward. |

||

<ref name="R&S631"/> Neighboring |

<ref name="R&S631"/> Neighboring Saudi Arabia opposed this development and actively supported North Yemen's rural tribes, pitting large parts of the country against the urban and largely pro-republican inhabitants of Sanaa.<ref name="Dumper331"/> The [[North Yemen Civil War]] resulted in the destruction of some parts of the city's ancient heritage and continued until 1968, when a deal between the republicans and the royalists was reached,<ref name="R&S631"/> establishing a presidential system. Instability in Sanaa continued due to continuing coups and political assassinations until the situation in the country stabilized in the late 1970s.<ref name="Dumper331"/> |

||

[[File:Taizz Road 1958.JPG|thumb|A 1958 view of Taizz Road, just outside the [[Bab al-Yaman]]]] |

|||

British writer [[Jonathan Raban]] visited in the 1970s and described the city as fortress-like, its architecture and layout resembling a [[labyrinth]]", further noting "It was like stepping out into the middle of a vast pop-up picturebook. Away from the street, the whole city turned into a maze of another kind, a dense, jumbled alphabet of signs and symbols." |

|||

The new government's modernization projects changed the face of Sanaa: the new [[Tahrir Square, Sanaa|Tahrir Square]] was built on what had formerly been the former imam's palace grounds, and new buildings were constructed on the north and northwest of the city. This was accompanied by the destruction of several of the old city's gates, as well as sections of the wall around it.<ref name="Lamprakos">{{cite journal |last1=Lamprakos |first1=Michele |title=Rethinking Cultural Heritage: Lessons from Sana'a, Yemen |journal=Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review |date=2005 |volume=16 |issue=2 |pages=17–37 |jstor=41747744 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/41747744 |access-date=14 February 2021 |archive-date=17 April 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210417182018/https://www.jstor.org/stable/41747744 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

After the end of the civil war in 1970, Sanaa began to expand outward.<ref name="Lamprakos"/> This was a period of prosperity in Yemen, partly due to the massive migration of Yemeni workers to the [[Arab states of the Persian Gulf|Gulf states]] and their subsequent sending of money back home. At first, most of the new development was concentrated around central areas like al-Tahrir, the modern centre; [[Bi'r al-Azab]], the Ottoman quarter; and [[Bab al-Yaman]], the old southern gate. However, this soon shifted to the city's outskirts, where an influx of immigrants from the countryside established new neighborhoods. Two areas in particular experienced major growth during this period: first, the area along Taizz Road in the south, and second, a broader area on the west side of the city, between Bi'r al-Azab and the new avenue called Sittin.<ref name="Le grand Sanaa">{{cite journal |last1=Stadnicki |first1=Roman |last2=Touber |first2=Julie |title=Le grand Sanaa Multipolarité et nouvelles formes d'urbanité dans la capitale du Yémen |journal=Annales de Géographie |date=2008 |volume=117 |issue=659 |pages=32–53 |doi=10.3917/ag.659.0032 |jstor=23457582 |doi-access=free }}</ref> A new ring road, built in the 1970s on the recommendation of the [[United Nations Development Programme]], encouraged land speculation and further contributed to the rapid expansion of Sanaa.<ref name="Lamprakos"/> |

|||

===Contemporary era=== |

|||

[[File:Jemen1988-142 hg.jpg|thumb|View of Wadi as-Sailah street in 1988, with the minaret of the [[Al-Mahdi Mosque, Sanaa|al-Mahdi Mosque]] visible in the background]] |

|||

Sanaa's new areas were physically different from the quarters of the old city. Many of the Yemenis who had migrated to the Gulf states had worked in construction, where they had become well-acquainted with Western and Egyptian techniques. When they returned to Yemen, they brought those techniques with them. New construction consisted of concrete and concrete block houses with multi-lite windows and plaster decorations, laid out in a grid pattern. Their amenities, including independence from extended families and the possibility of owning a car, attracted many families from the old city, and they moved to the new districts in growing numbers. Meanwhile, the old city, with its unpaved streets, poor drainage, lack of water and sewer systems, and litter (from the use of manufactured products, which was becoming increasingly common), was becoming increasingly unattractive to residents. Disaster struck in the late 1970s — water pipes were laid to bring water into the old city, but there was no way to pipe it out, resulting in huge amounts of groundwater building up in the old city. This destabilized building foundations and led to many houses collapsing.<ref name="Lamprakos"/> |

|||

===21st century=== |

|||

[[File:Attabari Elementary School is situated in the middle of the Old City of Sana'a, a UNESCO World Heritage site.jpg|thumb|Attabari Elementary School, Old City of Sanaʽa]] |

[[File:Attabari Elementary School is situated in the middle of the Old City of Sana'a, a UNESCO World Heritage site.jpg|thumb|Attabari Elementary School, Old City of Sanaʽa]] |

||

Following the [[Yemeni unification|unification of Yemen]], |

Following the [[Yemeni unification|unification of Yemen]], Sanaa was designated capital of the new Republic of Yemen. It houses the presidential palace, the [[Assembly of Representatives of Yemen|parliament]], the supreme court, and the country's government ministries. The largest source of employment is provided by governmental civil service. Due to massive rural immigration, Sanaa has grown far outside its Old City, but this has placed a huge strain on the city's underdeveloped infrastructure and municipal services, particularly water.<ref name="Dumper331"/> |

||

Sanaa was chosen as the 2004 [[Arab Cultural Capital]] by the [[Arab League]]. In 2008, the [[Al Saleh Mosque]] was completed. It holds over 40,000 worshippers. |

|||

In 2011, |

In 2011, Sanaa, as the Yemeni capital, was the centre of the [[Yemeni Revolution]], in which [[President of Yemen|President]] [[Ali Abdullah Saleh]] was ousted. Between May and November, the city was a battleground in what became known as the [[Battle of Sanaa (2011)|2011 Battle of Sanaa]]. |

||

On |

On May 21, 2012, Sanaa was [[2012 Sanaa bombing|attacked]] by a suicide bomber, resulting in the deaths of 120 soldiers. |

||

On |

On January 23, 2013, a drone strike near Al-Masna'ah village killed two civilians, according to a report<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/death-drones-report-eng-20150413.pdf|title=Death by Drone report|access-date=20 May 2018|archive-date=23 December 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181223035509/https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/death-drones-report-eng-20150413.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> issued by [[Radhya Al-Mutawakel]] and Abdulrasheed Al-Faqih and [[Open Society Foundations|Open Societies Foundations.]] |

||

===Houthi control (2014–present)=== |

|||

On 21 September 2014, during the [[Houthi insurgency in Yemen|Houthi insurgency]], the [[Houthis]] [[Battle of Sanaʽa (2014)|seized]] control of Sanaʽa. |

|||

{{main|Houthi takeover in Yemen|date=November 2022}} |

|||

[[File:Houthis-control 2014-2015.gif|350px|right|thumb|Houthi Expansion in Yemen from 2014 to 2015]] |

|||

On September 21, 2014, during the [[Houthi insurgency in Yemen|Houthi insurgency]], the [[Houthis]] [[Battle of Sanaa (2014)|seized]] control of Sanaa. |

|||

On |

On June 12, 2015, [[Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen|Saudi-led airstrikes]] targeting Shiite rebels and their allies in Yemen destroyed historic houses in the middle of the capital. A [[UNESCO World Heritage Site]] was severely damaged.<ref>{{cite news|last1=Gubash|first1=Charlene|last2=Smith|first2=Alexander|title=UNESCO Condemns Saudi-Led Airstrike on Yemen's Sanaa Old City|url=https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/unseco-condemns-suspected-saudi-led-airstrike-yemens-sanaa-old-city-n374216|work=[[NBC News]]|date=12 June 2015|access-date=7 October 2019|archive-date=7 January 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190107182646/https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/unseco-condemns-suspected-saudi-led-airstrike-yemens-sanaa-old-city-n374216|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

On |

On October 8, 2016, [[Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen|Saudi-led airstrikes]] targeted a hall in Sanaa where a funeral was taking place. At least 140 people were killed and about 600 were wounded. After initially denying it was behind the attack, the Coalition's Joint Incidents Assessment Team admitted that it had bombed the hall but claimed that this attack had been a mistake caused by bad information.<ref>{{cite news| url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/oct/15/saudi-led-coalition-admits-to-bombing-yemen-funeral| title=Saudi-led coalition admits to bombing Yemen funeral| date=15 October 2016| work=[[The Guardian]]| access-date=3 February 2017| archive-date=31 January 2017| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170131064759/https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/oct/15/saudi-led-coalition-admits-to-bombing-yemen-funeral| url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

In May 2017, according to the [[International Committee of the Red Cross]], an outbreak of [[cholera]] killed 115 people and left 8,500 ill.<ref>{{cite news|title=Houthis declares state of emergency in Sanaa over cholera outbreak|url=https://english.alarabiya.net/en/News/gulf/2017/05/14/115-dead-as-Yemen-cholera-outbreak-spreads.html|work=[[Al Arabiya]]|date=14 May 2017|access-date=15 May 2017|archive-date=17 May 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170517203304/http://english.alarabiya.net/en/News/gulf/2017/05/14/115-dead-as-Yemen-cholera-outbreak-spreads.html|url-status=live}}</ref> In late 2017, another [[Battle of Sanaa (2017)|Battle of Sanaa]] broke out between the Houthis and forces loyal to former President [[Ali Abdullah Saleh|Saleh]], who was killed. |

|||

On May 17, 2022, the first commercial flight in six years took off from [[Sanaa International Airport]] as part of a UN-brokered 60-day truce agreement struck between the Houthis and the internationally-recognized government the prior month.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-05-16 |title=First commercial flight in six years leaves Yemen's Sanaa amid fragile truce |url=https://www.france24.com/en/middle-east/20220516-first-commercial-flight-in-years-takes-off-from-yemen-s-sanaa-amid-fragile-truce |access-date=2022-05-17 |website=France 24 |language=en |archive-date=26 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220526181011/https://www.france24.com/en/middle-east/20220516-first-commercial-flight-in-years-takes-off-from-yemen-s-sanaa-amid-fragile-truce |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

==Geography and climate== |

==Geography and climate== |

||

[[File:جبل نقم - panoramio.jpg|thumb|Jabal Nuqm |

[[File:جبل نقم - panoramio.jpg|thumb|Jabal Nuqm or Jabal Nuqum ({{langx|ar|جَبَل نُقُم}}) of the Yemeni ''[[Sarawat Mountains|Sarawat]]'' in the area of Sanaa. Local legend has it that after the death of [[Noah]], his son [[Shem]] built the city at the base of this mountain.<ref name="Laughlin2008a"/>]] |

||

=== |

===Natural setting=== |

||

Sanaa is located on a plain of the same name, the '''Haql Sanaa''', which is over 2,200m above sea level. The plain is roughly 50–60 km long north–south and about 25 km wide, east–west, in the area north of Sanaa, and somewhat narrower further south. To the east and west, the Sanaa plain is bordered by cliffs and [[Al-Nahdayn Mountain|mountains]], with [[wadi]]s coming down from them. The northern part of the area slopes gently upward toward the district of [[Arhab]], which was historically known as ''al-Khashab''. Much of the Sanaa plain is drained by the [[Wadi al-Kharid]], which flows northward, through the northeastern corner of the plain, towards [[Jawf (Yemen)|al-Jawf]], which is a broad wadi that drains the eastern part of the Yemeni highlands. The southern part of the plain straddles the [[drainage divide|watershed]] between the al-Kharid and the [[Wadi Siham]], which flows southwest towards the Yemeni [[Tihama]].<ref name="Gazetteer">{{cite book |last1=Wilson |first1=Robert T.O. |title=Gazetteer of Historical North-West Yemen |date=1989 |publisher=Georg Olms AG |location=Germany |pages=7–9, 137, 244, 331 |isbn=9783487091952 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SnMrAAAAMAAJ |access-date=16 February 2021 |archive-date=6 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210506142001/https://www.google.com/books/edition/Gazetteer_of_Historical_North_West_Yemen/SnMrAAAAMAAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

Sanaa itself is located at the narrowest part of the plain, nestled between [[Jabal Nuqum]] to the east and the foothills of Jabal An-Nabi Shu'ayb, Yemen's tallest mountain, to the west. The mountain's peak is {{convert|25|km|mile|abbr=on}} west of Sanaa.<ref name="Gazetteer"/> Because of this position, with the city sandwiched between mountains to the east and west, most of Sanaa's expansion in recent decades has been along a north-south axis.<ref name="City Development Strategy"/> |

|||

Jabal Nuqum rises about {{convert|500|m|ft|abbr=off}} above Sanaa.<ref name="Gazetteer"/> According to the 10th-century writer [[Abu Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdani|Al-Hamdani]], the mountain was the site of an iron mine, although no trace of it exists today; he also mentions a particular type of [[onyx]] which came from Nuqum.<ref name="Gazetteer"/> [[Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi]] described a dam located at Nuqum; its location is not known.<ref name="Gazetteer"/> This dam probably served to divert the waters coming down from the western face of the mountain and prevent them from flooding the city of Sanaa.<ref name="Gazetteer"/> Such a flood is known to have happened in 692 (73 AH), before the dam was built, and it is described as having destroyed some of Sanaa's houses.<ref name="Gazetteer"/> Despite its proximity to the city, Jabal Nuqum does not appear to have been fortified until 1607 (1016 AH), when a fort was built to serve as a lookout point to warn of potential attackers.<ref name="Gazetteer"/> The main mountain stronghold during the Middle Ages was [[Jabal Barash]], further to the east.<ref name="Gazetteer"/> |

|||

Parts of the Sanaa plain have signs of relatively recent volcanic activity (geologically speaking), with volcanic cones and lava fields. One such area is located to the north, on the road to the [[Qa al-Bawn]], and the next plain to the north, located around [['Amran]] and [[Raydah]]. The modern route between the two plains passes to the west of [[Jabal Din]], a volcanic peak that marks the highest point between the two plains, although in medieval times the main route went to the east of the mountain.<ref name="Gazetteer"/> |

|||

===Architecture=== |

|||

Sanaa's Old City is renowned for its [[tower house]]s, which are typically built from stone and fired brick and can reach up to 8 stories in height. The doors and windows feature are decorated with [[plaster]] openings. They traditionally housed a single extended patrilineal family, with new floors being built as sons married and had children of their own. (New buildings would also sometimes be built on adjacent land.) The ground floor was typically used as grain storage and for housing animals. Most families no longer keep either animals or grain, so many homeowners set up shops on the ground floor instead. (This often leads to conflict with building inspectors, since doing so is prohibited by law.)<ref name="Lamprakos"/> Meanwhile, the uppermost story, called the ''mafraj'', is used as a second reception room and hosts afternoon qat chewing sessions.<ref name="Smith 1997"/> |

|||

Tower houses continue to be built in Sanaa, often using modern materials; often they are built from concrete blocks with decorative "veneers" of brick and stone.<ref name="Lamprakos"/> These "neo-traditional" tower houses are found in newer districts as well as the old city.<ref name="Le grand Sanaa"/> |

|||

Most new residences built in Sanaa, though, use newer styles of architecture. The most common are "new villas", which are low-rise houses with fenced yards; they are especially common in the southern and western parts of the city. The other main archetype is smaller, "Egyptian-style" houses, which are usually built with reinforced concrete. These are most commonly found in the northern and eastern parts of Sanaa.<ref name="Le grand Sanaa"/> |

|||

<gallery mode="packed"> |

|||

Tower-Houses_in_Old_Sana'a_(صنعاء_القديمة)_(2286023513).jpg|Several tower houses in Sanaa |

|||

Tower-Houses in Old Sana'a (2286137971).jpg|Tower houses |

|||

Tower-House in the Old City of Sana'a (2286782876).jpg|Closer view of a single tower house, showing the plaster decoration |

|||

Sana'a_in_the_1960s.jpg|Street scene in the 1960s, showing newer concrete-based architecture |

|||

مكتبة صنعاء الأثرية - panoramio.jpg|Sanaa Archaeological Library, showing a mix of styles: the windows evoke those of old tower houses, while the materials and structure are essentially modern. |

|||

Yem6.jpg|Contemporary monument in Sanaa, as-Sab'in street |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

===Cityscape=== |

|||

Generally, Sanaʽa is divided into two parts: the [[Old City District]] ("al-Qadeemah") and the new city ("al-Jadid.") The former is much smaller and retains the city's ancient heritage and mercantile way-of-living while the latter is an urban sprawl with many suburbs and modern buildings. The newer parts of the city were largely developed in the 1960s and onward when Sanaʽa was chosen as the republican capital.<ref name="R&S631"/> |

Generally, Sanaʽa is divided into two parts: the [[Old City District]] ("al-Qadeemah") and the new city ("al-Jadid.") The former is much smaller and retains the city's ancient heritage and mercantile way-of-living while the latter is an urban sprawl with many suburbs and modern buildings. The newer parts of the city were largely developed in the 1960s and onward when Sanaʽa was chosen as the republican capital.<ref name="R&S631"/> |

||

In recent decades, Sanaa has grown into a multipolar city, with various districts and suburbs serving as hubs of commercial, industrial, and social activity. Their development has generally been unplanned by central authorities. Many of them were initially set up by new arrivals from rural areas. Increasing land prices and commercial rents in the central city has also pushed many residents and commercial establishment outwards, towards these new hubs. [[Souk]]s have been especially important in the development of these areas.<ref name="Le grand Sanaa"/> |

|||

The following are the list of districts in the city: |

|||

{{col-begin}} |

|||

===Neighbourhoods=== |

|||

{{col-2}} |

|||

====Old City==== |

|||

{{Main|Old City of Sanaa}} |

|||

[[File:Bab Al Yemen Sanaa Yemen.jpg|thumb|The 1,000-year-old [[Bab al-Yaman|Bab Al-Yemen]] (Gate of The Yemen) at the centre of the old town]] |

|||

[[File:Old Sanaa, Yemen (10035455156).jpg|thumb|upright|Evening in the Old City]] |

|||

[[File:Old City Market, Sanaa (10035332343).jpg|thumb|Market in the Old City]] |

|||

[[File:Vegetable Garden in Old Sana'a (2286045031).jpg|thumb|Vegetable garden in the old city]] |

|||

The [[Old City District|Old City]] of Sanaʽa<ref name="Laughlin2008a">{{cite book |last=McLaughlin |first=Daniel |title=Yemen |publisher=[[Bradt Travel Guides]] |chapter=1: Background |page=3 |isbn=978-1-8416-2212-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eQvhZaEVzjcC |year=2008 |access-date=7 January 2019 |archive-date=14 February 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230214213157/https://books.google.com/books?id=eQvhZaEVzjcC |url-status=live }}</ref> is recognised as a [[UNESCO]] World Heritage Site. The old fortified city has been inhabited for more than 2,500 years and contains many intact architectural sites. The oldest, partially standing architectural structure in the Old City of Sanaʽa is [[Ghumdan Palace]]. The city was declared a [[World Heritage Site]] by the United Nations in 1986. Efforts are underway to preserve some of the oldest buildings some of which, such as the Samsarh and the [[Great Mosque of Sanaʽa]], is more than 1,400 years old. Surrounded by ancient clay walls that stand {{convert|9|-|14|m|ft}} high, the Old City contains more than 100 mosques, 12 ''hammams'' (baths), and 6,500 houses. Many of the houses resemble ancient skyscrapers, reaching several stories high and topped with flat roofs. They are decorated with elaborate friezes and intricately carved frames and stained-glass windows. |

|||

One of the most popular attractions is ''Suq al-Milh'' (Salt Market), where it is possible to buy salt along with bread, spices, raisins, cotton, copper, pottery, silverware, and antiques. The 7th-century [[Great Mosque of Sanaʽa|''Jāmiʿ al-Kabīr'']] (the Great Mosque) is one of the oldest mosques in the world. The ''[[Bab al-Yaman|Bāb al-Yaman]]''<ref name="Laughlin2008a" /> ("Gate of the Yemen") is an iconized entry point through the city walls and is more than 1,000 years old. Traditionally, the Old City was composed of several quarters (''hara''), generally centred on an endowed complex containing a mosque, a [[Turkish bath|bathhouse]], and an agricultural garden (''maqshama''). Human waste from households was disposed of via chutes. In the mountain air, it dried fairly quickly and was then used as fuel for the bathhouse. Meanwhile, the gardens were watered using [[gray water]] from the mosque's ablution pool.<ref name="Lamprakos" /> |

|||

=====Al-Tahrir===== |

|||

[[At Tahrir District|Al-Tahrir]] was designed as the new urban and economic hub of Sanaa during the 1960s. It is still the symbolic centre of the city, but economic activity here is relatively low. In the 21st century, development here pivoted more towards making it a civic and recreational centre.<ref name="Le grand Sanaa"/> |

|||

=====Bi'r al-Azab===== |

|||

An old Ottoman and Jewish quarter of Sanaa<ref name="Le grand Sanaa"/> located to the west of the old city, Bi'r al-Azab was first mentioned in historical sources in 1627 (1036 AH), in the ''[[Ghayat al-amanni]]'' of [[Yahya ibn al-Husayn]].<ref name="Gazetteer"/> |

|||

As part of central Sanaa, Bi'r al-Azab was one of the areas where new development was first concentrated during the 1970s. Today, it is mostly a residential and administrative district, with embassies, the office of the Prime Minister, and the chamber of deputies being located here.<ref name="Le grand Sanaa"/> |

|||

====Others==== |

|||

The area roughly between the two main circular roads around the city (Ring Road and Sittin) is extremely active, with a high population density and very busy souks. These areas are crossed by major commercial thoroughfares such as al-Zubayri and [[Abd al-Mughni Street]], and are extensively served by public transport. Particularly significant districts in this area include [[al-Hasabah]] in the north, [[Shumayla]] in the south, and [[Hayil, Yemen|Hayil]] in the west.<ref name="Le grand Sanaa"/> Al-Hasabah was formerly a separate village as described by medieval writers [[Abu Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdani|al-Hamdani]] and [[Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi|al-Razi]], but by the 1980s it had become a suburb of Sanaa.<ref name="Gazetteer"/> |

|||

The southwestern area on both sides of [[Haddah Road]] is a generally affluent area with relatively more reliable access to utilities like water and sanitation. Many residents originally moved here from Aden after Yemeni reunification in 1990. Since the 1990s, there has been development of high-rise buildings in this area.<ref name="Le grand Sanaa"/> |

|||

===Administration=== |

|||

{{see also|List of districts of Yemen}} |

|||

In 1983, as Sanaa experienced an explosion in population, the city was made into a governorate of its own, called '''Amanat al-Asimah''' (''"the Capital's Secretariat"''), by Presidential Decree No. 13.<ref name="UN-Habitat"/> This governorate was then subdivided into nine districts in 2001, by Presidential Decree No. 2; a tenth district, [[Bani Al Harith District]], was added within the same year.<ref name="UN-Habitat"/> However, the exact legal status of the new Amanat al-Asimah Governorate, and the hierarchy of administrative authority, was never made clear.<ref name="UN-Habitat"/> |

|||

Since then, the city of Sanaa has encompassed the following districts: |

|||

*[[Old City District]] |

|||

*[[Al Wahdah District]] |

*[[Al Wahdah District]] |

||

*[[As Sabain District]] |

*[[As Sabain District]] |

||

| Line 207: | Line 284: | ||

*[[Ma'ain District]] |

*[[Ma'ain District]] |

||

*[[Shu'aub District]] |

*[[Shu'aub District]] |

||

{{col-2}} [[File:Bab Al Yemen Sanaa Yemen.jpg|thumb|The 1,000-year-old [[Bab al-Yaman|Bab Al-Yemen]] (Gate of The Yemen) at the centre of the old town]] |

|||

;Old City |

|||

*[[Old City District]] |

|||

{{col-2}} |

|||

{{col-end}} |

|||

===Climate=== |

===Climate=== |

||

Sanaʽa features |

Sanaʽa features a cold [[desert climate]] ([[Köppen-Geiger climate classification system|Köppen]]: BWk).<ref name="Climate-Data.org">{{Cite web |url=http://en.climate-data.org/location/3171/ |title=Climate: Sanaa – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table |publisher=Climate-Data.org |access-date=2014-02-23 |archive-date=8 January 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140108002826/http://en.climate-data.org/location/3171/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Sanaʽa sees on average {{convert|265|mm|2|abbr=on}} of [[precipitation]] per year. Due to its high elevation, however, temperatures are much more moderate than many other cities on the [[Arabian Peninsula]]; average temperatures remain relatively constant throughout the year in Sanaa, with its coolest month being January and its warmest month July. Even considering this, as a result of its lower latitude and higher elevation, [[UV radiation]] from the sun is much stronger than in the hotter climates further north on the [[Arab peninsula]]. |

||

The city seldom experiences extreme heat or cold. Some areas around the city, however, can see temperatures fall to around {{convert|-9|C|0}} or {{convert|-7|C|0}} during winter. [[Frost]] usually occurs in the early winter mornings, and there is a slight [[wind chill]] in the city at elevated areas that causes the cold mornings to be bitter, including low [[humidity]]. The sun warms the city to the high {{convert |

The city seldom experiences extreme heat or cold. Some areas around the city, however, can see temperatures fall to around {{convert|-9|C|0}} or {{convert|-7|C|0}} during winter. [[Frost]] usually occurs in the early winter mornings, and there is a slight [[wind chill]] in the city at elevated areas that causes the cold mornings to be bitter, including low [[humidity]]. The sun warms the city to the high {{convert|20|-|22|C|abbr=on}} during the noontime but it drops drastically after nightfall to a low around {{convert|3|-|4|C|abbr=on}}. |

||

The city experiences many [[microclimate]]s from district to district because of its location in the |

The city experiences many [[microclimate]]s from district to district because of its location in the Sanaa basin and uneven elevations throughout the city. Summers are warm and it can cool swiftly at night, especially after rainfall. Sanaa receives almost all of its annual rainfall from April to August. Rainfall amounts vary from year to year; some years could see {{convert|500|–|600|mm|in|abbr=in}} of rainfall, while others barely get {{convert|150|mm|in|abbr=in}}. High temperatures have increased slightly during the summer over the past few years, while low temperatures and winter temperatures have also risen over the same period. |

||

{{Weather box |

{{Weather box |

||

| Line 224: | Line 296: | ||

|metric first=yes |

|metric first=yes |

||

|single line=yes |

|single line=yes |

||

|location=Sanaa, |

|location=Sanaa, elevation {{convert|2190|m|ft|abbr=on}} (1993–2014 normals) |

||

|Jan |

|Jan high C = 22.7 |

||

|Feb |

|Feb high C = 24.9 |

||

|Mar |

|Mar high C = 25.5 |

||

|Apr |

|Apr high C = 26.2 |

||

|May |

|May high C = 27.8 |

||

|Jun |

|Jun high C = 28.7 |

||

|Jul |

|Jul high C = 28.5 |

||

|Aug |

|Aug high C = 27.1 |

||

|Sep |

|Sep high C = 26.7 |

||

|Oct |

|Oct high C = 23.8 |

||

|Nov |

|Nov high C = 22.8 |

||

|Dec |

|Dec high C = 22.3 |

||

| year high C = |

|||

|Jan mean C = 15.1 |

|||

|Feb mean C = 17.8 |

|||

|Mar mean C = 19.3 |

|||

|Apr mean C = 20.5 |

|||

|May mean C = 22.3 |

|||

|Jun mean C = 23.6 |

|||

|Jul mean C = 23.6 |

|||

|Aug mean C = 22.6 |

|||

|Sep mean C = 21.4 |

|||

|Oct mean C = 18.1 |

|||

|Nov mean C = 16.7 |

|||

|Dec mean C = 15.3 |

|||

| year mean C = |

|||

|Jan low C = 7.5 |

|||

|Feb low C = 10.7 |

|||

|Mar low C = 13.1 |

|||

|Apr low C = 14.8 |

|||

|May low C = 16.8 |

|||

|Jun low C = 18.4 |

|||

|Jul low C = 18.6 |

|||

|Aug low C = 18.1 |

|||

|Sep low C = 16.2 |

|||

|Oct low C = 12.3 |

|||

|Nov low C = 10.6 |

|||

|Dec low C = 8.3 |

|||

| year low C = |

|||

|precipitation colour = green |

|||

|Jan precipitation mm = 3 |

|||

|Feb precipitation mm = 4 |

|||

|Mar precipitation mm = 17 |

|||

|Apr precipitation mm = 49 |

|||

|May precipitation mm = 22 |

|||

|Jun precipitation mm = 3 |

|||

|Jul precipitation mm = 41 |

|||

|Aug precipitation mm = 68 |

|||

|Sep precipitation mm = 9 |

|||

|Oct precipitation mm = 1 |

|||

|Nov precipitation mm = 7 |

|||

|Dec precipitation mm = 4 |

|||

|year precipitation mm = |

|||

|unit precipitation days = 1.0 mm |

|||

| Jan precipitation days = 0.0 |

|||

| Feb precipitation days = 0.2 |

|||

| Mar precipitation days = 1.4 |

|||

| Apr precipitation days = 3.3 |

|||

| May precipitation days = 1.9 |

|||

| Jun precipitation days = 0.4 |

|||

| Jul precipitation days = 3.2 |

|||

| Aug precipitation days = 3.0 |

|||

| Sep precipitation days = 0.1 |

|||

| Oct precipitation days = 0.4 |

|||

| Nov precipitation days = 0.4 |

|||

| Dec precipitation days = 0.1 |

|||

| year precipitation days = |

|||

|Jan |

|Jan humidity=42.0 |

||

|Feb |

|Feb humidity=38.6 |

||

|Mar |

|Mar humidity=43.2 |

||

|Apr |

|Apr humidity=43.6 |

||

|May |

|May humidity=35.5 |

||

|Jun |

|Jun humidity=30.6 |

||

|Jul |

|Jul humidity=40.0 |

||

|Aug |

|Aug humidity=43.9 |

||

|Sep |

|Sep humidity=31.9 |

||

|Oct |

|Oct humidity=34.2 |

||

|Nov |

|Nov humidity=38.8 |

||

|Dec |

|Dec humidity=40.7 |

||

|year humidity= |

|||

|source 1 = IEM<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url=https://mesonet.agron.iastate.edu/sites/monthlysum.php?station=OYSN&network=YE__ASOS |

|||

|title= [OYSN] Sanaa [1974-2017] Monthly Summaries |

|||

|publisher=The Iowa Environmental Mesonet |

|||

|access-date=21 December 2024}}</ref>[[Food and Agriculture Organization|FAO]] (precipitation)<ref name=FAO>{{cite web |

|||

| url = https://www.fao.org/land-water/land/land-governance/land-resources-planning-toolbox/category/details/fr/c/1028000/ |

|||

| title = World-wide Agroclimatic Data of FAO (FAOCLIM) |

|||

| publisher= Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations |

|||

| access-date = 12 November 2024}}</ref> |

|||

| source 2 = Meteomanz (precipitation days 2000–2015)<ref name=Meteomanz>{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://www.meteomanz.com/sy3?l=1&cou=2044&ind=41404&m1=01&y1=2000&m2=12&y2=2015 |

|||

| title = SYNOP/BUFR observations. Data by months |

|||

| publisher = Meteomanz |

|||

| access-date = 20 December 2024}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

==Culture== |

|||

|Jan mean C=12.6 |

|||

[[File:House Interior, Sanaa (10720986825).jpg|thumb|upright|A [[Majlis#Residential|majlis]] (sitting room) in Sanaa, 2013]] |

|||

|Feb mean C=14.1 |

|||

[[File:Store Models, Sanaa (10035280434).jpg|thumb|Store models showing traditional Sanʽani women's clothes]] |

|||

|Mar mean C=16.3 |

|||

[[File:Art Gallery, Sana'a, Yemen (15335689380).jpg|thumb|left|An art gallery in Sanaa]] |

|||

|Apr mean C=16.6 |

|||

{{See also|Culture of Yemen}} |

|||

|May mean C=18.0 |

|||

|Jun mean C=19.3 |

|||

|Jul mean C=20.0 |

|||

|Aug mean C=19.6 |

|||

|Sep mean C=17.8 |

|||

|Oct mean C=15.0 |

|||

|Nov mean C=12.9 |

|||

|Dec mean C=12.4 |

|||

===Music=== |

|||

|Jan low C=3.0 |

|||

Sanaa has a rich musical tradition and is particularly renowned for the musical style called ''al-Ghina al-San'ani'' ({{langx|ar|الغناء الصنعاني}} {{transliteration|ar|al-ġināʾ aṣ-Ṣanʿānī}}), or "the song of Sanaa", which dates back to the 14th century and was designated as a [[UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists|UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage]] in 2003.<ref name="Song of Sanaa">{{cite web |title=Song of Sana'a |url=https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/song-of-sanaa-00077 |website=UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage |access-date=3 March 2021 |archive-date=10 December 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201210130156/https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/song-of-sanaa-00077 |url-status=live }}</ref> This style of music is not exclusive to Sanaa, and is found in other areas of Yemen as well, but it is most closely associated with the city.<ref name="Song of Sanaa"/> It is one of about five regional genres or "colors" (''lawn'') of Yemeni music, along with [[Yafa'|Yafi]]'i, [[Lahej]]i, [[Aden]]i, and [[Hadhramaut|Hadhrami]].<ref name="Flagg 2007">{{cite book |last1=Miller |first1=Flagg |title=The Moral Resonance of Arab Media |date=2007 |publisher=Harvard University Press |location=Cambridge |isbn=978-0-932885-32-6 |pages=223, 225–6, 240, 245, 271 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qEa3rA3tQ-sC |access-date=25 January 2022 |archive-date=25 January 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220125073911/https://books.google.com/books?id=qEa3rA3tQ-sC |url-status=live }}</ref> It is often part of social events, including the [[samra (wedding)|samra]], or evening wedding party, and the [[magyal]], or daily afternoon gathering of friends.<ref name="Song of Sanaa"/> |

|||

|Feb low C=3.6 |

|||

|Mar low C=7.0 |

|||

|Apr low C=8.5 |

|||

|May low C=10.4 |

|||

|Jun low C=10.5 |

|||

|Jul low C=13.4 |

|||

|Aug low C=13.3 |

|||

|Sep low C=10.6 |

|||

|Oct low C=7.9 |

|||

|Nov low C=5.5 |

|||

|Dec low C=4.4 |

|||

The basic format consists of a singer accompanied by two instrumentalists, one playing the [[qanbus]] (Yemeni lute) and the other playing the [[sahn nuhasi]], which is a copper tray balanced on the musician's thumbs and played by being lightly struck by the other eight fingers.<ref name="Song of Sanaa"/> Lyrics are in both [[classical Arabic]] and [[Yemeni Arabic]] and are known for their wordplay and emotional content.<ref name="Song of Sanaa"/> Singers often use [[melisma]]tic vocals, and the arrangements feature pauses between verses and instrumental sections.<ref name="Flagg 2007"/> Skilled performers often "embellish" a song's melody to highlight its emotional tone.<ref name="Song of Sanaa"/> |

|||

|Jan record low C=-4 |

|||

|Feb record low C=-1 |

|||

|Mar record low C=1 |

|||

|Apr record low C=4 |

|||

|May record low C=1 |

|||

|Jun record low C=9 |

|||

|Jul record low C=5 |

|||

|Aug record low C=0 |

|||

|Sep record low C=3 |

|||

|Oct record low C=1 |

|||

|Nov record low C=-1 |

|||

|Dec record low C=-2 |

|||

In the earliest days of the recording industry in Yemen, from 1938 into the 1940s, Sanaani music was the dominant genre among Yemenis who could afford to buy [[phonograph record|record]]s and [[phonograph]]s (primarily in Aden).<ref name="Flagg 2007"/> As prices fell, Sanaani-style records became increasingly popular among the middle class, but at the same time, it began to encounter competition from other genres, including Western and Indian music as well as music from other Arab countries.<ref name="Flagg 2007"/> The earliest Sanaani recording stars generally came from wealthy religious families.<ref name="Flagg 2007"/> The most popular was 'Ali Abu Bakr Ba Sharahil, who recorded for [[Odeon Records]]; other popular artists included Muhammad and Ibrahim al-Mas, Ahmad 'Awad al-Jarrash, and Muhammad 'Abd al-Rahman al-Makkawi.<ref name="Flagg 2007"/> |

|||

|precipitation colour = green |

|||

|Jan precipitation mm=5 |

|||

|Feb precipitation mm=5 |

|||

|Mar precipitation mm=17 |

|||

|Apr precipitation mm=48 |

|||

|May precipitation mm=29 |

|||

|Jun precipitation mm=6 |

|||

|Jul precipitation mm=50 |

|||

|Aug precipitation mm=77 |

|||

|Sep precipitation mm=13 |

|||

|Oct precipitation mm=2 |

|||

|Nov precipitation mm=8 |

|||

|Dec precipitation mm=5 |

|||

===Theatre=== |

|||

|Jan rain days=2 |

|||

{{main article|Theatre in Yemen}} |

|||

|Feb rain days=3 |

|||

Yemen has a rich, lively tradition of theatre-going back at least a century. In Sanaa, most performances take place at the [[Cultural Center (Sanaa)|Cultural Center]]<ref name="Hennessey in journal">{{cite journal |last1=Hennessey |first1=Katherine |title=Drama in Yemen: Behind the Scenes at World Theater Day |journal=Middle East Report |date=2014 |issue=271 |pages=36–49 |jstor=24426557 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/24426557 |access-date=15 February 2021 |archive-date=15 April 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210415025328/https://www.jstor.org/stable/24426557 |url-status=live }}</ref> (''Markaz al-Thaqafi''),<ref name="Hennessey in book">{{cite book |last1=Hennessey |first1=Katherine |editor1-last=Lackner |editor1-first=Helen |title=Why Yemen Matters: A Society in Transition |date=2014 |isbn=9780863567827 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=R0EhBQAAQBAJ |access-date=14 February 2021 |chapter=Yemeni Society in the Spotlight: Theatre and Film in Yemen Before, During, and After the Arab Spring |archive-date=14 April 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210414044400/https://books.google.com/books?id=R0EhBQAAQBAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> which was originally designed as an auditorium instead of a theatre. It "possesses only the most basic of lighting and sound equipment, and the smallest of wings"<ref name="Hennessey in journal"/> and lacks space to store props or backdrops. Yet despite the scarce resources, "dramatic talent and creativity abound"<ref name="Hennessey in journal"/> and productions draw large, enthusiastic crowds who react on the action onstage with vigor: "uproarious laughter at clever lines, and deafening cheers for the victorious hero, but also occasional shouts of disagreement, cries of shock when an actor or actress breaks a taboo or expresses a controversial opinion."<ref name="Hennessey in journal"/> [[Katherine Hennessey]] draws attention to the fact that Yemeni women act alongside men onstage, write and direct plays ([[Nargis Abbad]] being one of the most popular), and make up a significant part of audiences, often bringing their children with them. She contrasts all these factors to the other countries on the Arabian peninsula: places like [[Qatar]] or [[Saudi Arabia]] have extensive resources and fancier facilities, but not much of a theatrical tradition, and casts and audiences are often segregated by gender.<ref name="Hennessey in journal"/> |

|||

|Mar rain days=4 |

|||

|Apr rain days=5 |

|||

|May rain days=5 |

|||

|Jun rain days=4 |

|||

|Jul rain days=4 |

|||

|Aug rain days=5 |

|||

|Sep rain days=3 |

|||

|Oct rain days=3 |

|||

|Nov rain days=2 |

|||

|Dec rain days=1 |

|||

Since Yemeni reunification in the early 1990s, the government has sponsored annual national theatre festivals, typically scheduled to coincide with [[World Theatre Day]] on March 27. In the 21st century, the actors and directors have increasingly come from Sanaa.<ref name="Hennessey in journal"/> In 2012, in addition to the festival, there was a national theatre competition, sponsored by [[Equal Access Yemen]] and [[Future Partners for Development]], featuring theatre troupes from around the country. It had two rounds; the first was held in six different governorates, and the second was held in Sanaa.<ref name="Hennessey in book"/> |

|||

|Jan humidity=39.3 |

|||

|Feb humidity=35.8 |

|||

|Mar humidity=38.5 |

|||

|Apr humidity=41.1 |

|||

|May humidity=36.0 |

|||

|Jun humidity=27.2 |

|||

|Jul humidity=40.1 |

|||

|Aug humidity=45.5 |

|||

|Sep humidity=29.9 |

|||

|Oct humidity=29.0 |

|||

|Nov humidity=38.1 |

|||

|Dec humidity=37.7 |

|||

|year humidity=36.5 |

|||

Sanaa's theatre scene was disrupted by war and famine in the 2010s; additionally, since the Houthis gained control of the city in 2014, they "have imposed strict rules on dress, gender segregation, and entertainment in the capital." In December 2020, however, a performance was held in Sanaa by one troupe, to offer respite and entertainment to people in a city suffering from the civil war and the ongoing [[Coronavirus in Yemen|coronavirus pandemic]]. Directed by [[Mohammed Khaled (director)|Mohammad Khaled]], the performance drew a crowd of "dozens of men, women and children."<ref name="2020 theatre performance">{{cite news |title=Theatre troupe bring smiles and comic relief to war-weary Yemenis |url=https://www.france24.com/en/middle-east/20201229-theatre-troupe-bring-smiles-and-comic-relief-to-war-weary-yemenis |access-date=15 February 2021 |work=France 24 |archive-date=15 February 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210215011431/https://www.france24.com/en/middle-east/20201229-theatre-troupe-bring-smiles-and-comic-relief-to-war-weary-yemenis |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||