Buffalo, New York: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edit by 2603:7000:3144:9000:3D68:49DF:50B8:3388 (talk) to last version by Boredintheevening |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|City in New York, United States}} |

|||

{{Infobox City |

|||

{{redirect|Buffalo, United States|other places|Buffalo (disambiguation)#United States{{!}}Buffalo § United States}} |

|||

| official_name = Buffalo, New York |

|||

{{Good article}} |

|||

| image_skyline = Buffalo_skyline_edit1.jpg |

|||

{{Use American English|date=October 2022}} |

|||

| nickname = City of Good Neighbors, Queen City, City of Light |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=October 2022}} |

|||

| image_flag = BuffaloNYFlag.jpg |

|||

{{Infobox settlement |

|||

| image_seal = BuffaloSeal.PNG |

|||

| |

| name = Buffalo |

||

| settlement_type = [[Administrative divisions of New York (state)#City|City]] |

|||

| map_caption = Location of Buffalo in New York State |

|||

| etymology = Named after the nearby [[Buffalo River (New York)|Buffalo Creek]], which was named by French and Moravian explorers<ref name="Beautiful" /><ref name = "River" /><ref name="Bison" /> |

|||

| subdivision_type = [[County]] |

|||

| nicknames = Queen City, City of Good Neighbors, City of No Illusions, Nickel City, Queen City of the Lakes, City of Light, The Electric City, City of Trees<ref>{{cite web |last1=Neville |first1=Anne |title=Who are we? Queen City, Flour City, Nickel City ... what's with all the nicknames for Buffalo? |url=https://buffalonews.com/news/who-are-we-queen-city-flour-city-nickel-city-whats-with-all-the-nicknames-for/article_7b5d66ea-f4b5-5a9a-ac5c-089f7b3f41e7.html |url-access=limited |website=[[The Buffalo News]] |access-date=26 May 2021 |language=en |date=August 16, 2009 |archive-date=June 22, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210622041718/https://buffalonews.com/news/who-are-we-queen-city-flour-city-nickel-city-whats-with-all-the-nicknames-for/article_7b5d66ea-f4b5-5a9a-ac5c-089f7b3f41e7.html |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| subdivision_name = [[Erie County, New York|Erie County]] |

|||

| |

| motto = |

||

| |

| image_skyline = {{multiple image |

||

| |

| border = infobox |

||

| perrow = 1/2/3/2 |

|||

| area_magnitude = 1 E9 |

|||

| |

| total_width = 300 |

||

| |

| caption_align = center |

||

| image1 = Buffalo Skyline from Drone 1 (cropped).jpg |

|||

| area_water = 30.8 |

|||

| caption1 = Buffalo skyline |

|||

| population_as_of = 2000 <ref>[http://www.demographia.com/db-metrocore2005.htm Metropolitan & Central City Population: 2000-2005]. ''Demographia.com'', accessed September 3, 2006.</ref> |

|||

| image2 = Peace Bridge.jpg |

|||

| population_note = |

|||

| caption2 = The [[Peace Bridge]] |

|||

| population_total = 292,648 |

|||

| image3 = KeyBank Center side view from Main Street at Prime Street, Buffalo, New York - 20210725.jpg |

|||

| population_metro = 1,254,066 |

|||

| caption3 = [[KeyBank Center]] |

|||

| population_density = 2782.4 |

|||

| |

| image4 = View of Buffalo City Hall (cropped).jpg |

||

| |

| caption4 = [[Buffalo City Hall]] |

||

| image5 = 20150827 61 NFTA Light Rail at Fountain Plaza (21990211710) (cropped).jpg |

|||

| timezone_DST = [[Eastern Daylight Time|EDT]] |

|||

| caption5 = [[Buffalo Metro Rail|NFTA Metro Rail]] |

|||

| utc_offset_DST = −4 |

|||

| |

| image6 = Hayes Hall crop.jpg |

||

| |

| caption6 = [[University at Buffalo]] |

||

| image7 = 2024.10.10 AKGCampusExteriorDronePhotos-1001.jpg |

|||

| website = [http://www.ci.buffalo.ny.us/ Buffalo, NY] |

|||

| caption7 = [[Buffalo AKG Art Museum]] in [[Delaware Park-Front Park System|Delaware Park]] |

|||

| footnotes = |

|||

| image8 = Buffalo Central Terminal, Paderewski Drive, Broadway-Fillmore, Buffalo, NY.jpg |

|||

| caption8 = [[Buffalo Central Terminal]] |

|||

}} |

|||

| image_flag = Flag of Buffalo, New York.svg |

|||

| flag_size = 110px |

|||

| image_seal = Seal of Buffalo, New York.svg |

|||

| seal_size = 90px |

|||

| image_map = {{maplink |

|||

| frame = yes |

|||

| plain = yes |

|||

| frame-align = center |

|||

| frame-width = 290 |

|||

| frame-height = 290 |

|||

| frame-coord = {{coord|qid=Q40435}} |

|||

| zoom = 10 |

|||

| type = shape |

|||

| marker = city |

|||

| stroke-width = 2 |

|||

| stroke-color = #0096FF |

|||

| fill = #0096FF |

|||

| id2 = Q40435 |

|||

| type2 = shape-inverse |

|||

| stroke-width2 = 2 |

|||

| stroke-color2 = #5F5F5F |

|||

| stroke-opacity2 = 0 |

|||

| fill2 = #000000 |

|||

| fill-opacity2 = 0 |

|||

}} |

|||

| map_caption = Interactive map of Buffalo |

|||

| pushpin_map = New York#USA |

|||

| pushpin_relief = yes |

|||

| coordinates = {{Coord|42|53|11|N|78|52|41|W|region:US-NY|display=inline,title}} |

|||

| subdivision_type = [[List of sovereign states|Country]] |

|||

| subdivision_name = {{flagdeco|USA}} United States |

|||

| subdivision_type1 = [[U.S. state|State]] |

|||

| subdivision_name1 = {{flagdeco|New York}} [[New York (state)|New York]] |

|||

| subdivision_type2 = Region |

|||

| subdivision_name2 = [[Western New York]] |

|||

| subdivision_type3 = [[List of metropolitan statistical areas|Metro]] |

|||

| subdivision_name3 = [[Buffalo–Niagara Falls metropolitan area|Buffalo–Niagara Falls]] |

|||

| subdivision_type4 = [[List of counties in New York|County]] |

|||

| subdivision_name4 = [[Erie County, New York|Erie]] |

|||

| government_type = [[Mayor–council government#Strong-mayor government form|Strong mayor-council]] |

|||

| governing_body = [[Buffalo Common Council]] |

|||

| leader_title = [[List of mayors of Buffalo, New York|Mayor]] |

|||

| leader_name = [[Christopher Scanlon]] ([[Democratic Party (United States)|D]]) (acting) |

|||

| leader_title1 = [[Deputy Mayor]] |

|||

| leader_name1 = Rashied McDuffie [[Democratic Party (United States)|(D)]] |

|||

| leader_title2 = [[New York State Senate|State Senators]] |

|||

| leader_name2 = April Baskin & [[Sean M. Ryan|Sean Ryan]] ([[Democratic Party (United States)|D]]) |

|||

| leader_title3 = [[New York State Assembly|Assemblymembers]] |

|||

| leader_name3 = William Conrad ([[Democratic Party (United States)|D]]), [[Crystal Peoples-Stokes]] ([[Democratic Party (United States)|D]]), [[Patrick B. Burke|Patrick Burke]] ([[Democratic Party (United States)|D]]), Patrick Chludzinski ([[Republican Party (United States)|R]]), & [[Jonathan Rivera|Jon Rivera]] ([[Democratic Party (United States)|D]]) |

|||

| leader_title4 = [[New York's 26th congressional district|U.S. Rep.]] |

|||

| leader_name4 = [[Timothy M. Kennedy (politician)|Tim Kennedy]] ([[Democratic Party (United States)|D]]) |

|||

| established_title = First settled (village) |

|||

| established_date = {{start date and age|1789}} |

|||

| established_title2 = Founded |

|||

| established_date2 = {{start date and age|1801}} |

|||

| established_title3 = Incorporated (city) |

|||

| established_date3 = {{start date and age|1832}} |

|||

| named_for = [[Buffalo River (New York)|Buffalo River]] |

|||

| unit_pref = Imperial |

|||

| area_total_sq_mi = 52.48 |

|||

| area_land_sq_mi = 40.38 |

|||

| area_water_sq_mi = 12.10 |

|||

| area_total_km2 = 135.92 |

|||

| area_land_km2 = 104.58 |

|||

| area_water_km2 = 31.34 |

|||

| elevation_footnotes = <ref name=gnis/> |

|||

| elevation_m = |

|||

| elevation_ft = 600 |

|||

| population_as_of = [[2020 United States Census|2020]] |

|||

| population_footnotes = |

|||

| pop_est_as_of = |

|||

| pop_est_footnotes = |

|||

| population_total = 278349 |

|||

| population_rank = US: [[List of United States cities by population|81st]] NY: [[List of cities in New York (state)|2nd]] |

|||

| population_density_km2 = 2661.58 |

|||

| population_density_sq_mi = 6893.41 |

|||

| population_urban = 948,864 (US: [[List of United States urban areas|50th]]) |

|||

| population_density_urban_km2 = 1,075.9 |

|||

| population_density_urban_sq_mi = 2,786.7 |

|||

| population_urban_footnotes = <ref name="urban area">{{cite web |url=https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/urban-rural.html|title=List of 2020 Census Urban Areas|website=census.gov|publisher=United States Census Bureau|access-date=July 22, 2023}}</ref> |

|||

| population_metro = 1,125,637 (US: [[List of metropolitan statistical areas|49th]])<ref name=PopEstCBSA>{{cite web |url=https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/technical-documentation/research/evaluation-estimates/2020-evaluation-estimates/2010s-totals-metro-and-micro-statistical-areas.html |title=Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals: 2010–2020 |work=2020 Population Estimates |publisher=[[US Census Bureau]], Population Division |access-date=June 28, 2021}}</ref> |

|||

| population_blank2_title = [[Combined statistical area|CSA]] |

|||

| population_blank2 = 1,201,500 (US: [[Combined statistical area|48th]]) |

|||

| population_demonyms = Buffalonian |

|||

| demographics_type2 = GDP |

|||

| demographics2_footnotes = <ref>{{Cite web|title=Total Gross Domestic Product for Buffalo-Cheektowaga-Niagara Falls, NY (MSA)|url=https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/NGMP15380|website=fred.stlouisfed.org}}</ref> |

|||

| demographics2_title1 = Buffalo–Niagara Falls (MSA) |

|||

| demographics2_info1 = $84.673 billion (2022) |

|||

| timezone = [[Eastern Time Zone|EST]] |

|||

| utc_offset = −05:00 |

|||

| timezone_DST = [[Eastern Daylight Time|EDT]] |

|||

| utc_offset_DST = −04:00 |

|||

| postal_code_type = [[ZIP code]] |

|||

| postal_code = 142XX |

|||

| area_code = [[Area code 716|716]], [[Area code 624|624]] |

|||

| blank_name = [[Federal Information Processing Standard|FIPS code]] |

|||

| blank_info = 36-11000 |

|||

| blank1_name = [[Geographic Names Information System|GNIS]] feature ID |

|||

| blank1_info = 0973345<ref name=gnis>{{GNIS|973345}}</ref> |

|||

| website = {{URL|https://www.buffalony.gov|buffalony.gov}} |

|||

| footnotes = |

|||

| area_footnotes = <ref name="TigerWebMapServer">{{cite web|title=ArcGIS REST Services Directory|url=https://tigerweb.geo.census.gov/arcgis/rest/services/TIGERweb/Places_CouSub_ConCity_SubMCD/MapServer|publisher=United States Census Bureau|access-date=September 20, 2022}}</ref> |

|||

| population_est = |

|||

| official_name = |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Buffalo''' is a [[Administrative divisions of New York (state)|city]] in the [[U.S. state]] of [[New York (state)|New York]] and the [[county seat]] of [[Erie County, New York|Erie County]]. It lies in [[Western New York]] at the eastern end of [[Lake Erie]], at the head of the [[Niagara River]] on the [[Canada–United States border|Canadian border]]. With a population of 278,349 according to the 2020 census, Buffalo is the [[List of municipalities in New York|second-most populous city]] in New York state after [[New York City]], and the [[List of United States cities by population|81st-most populous city]] in the U.S.<ref name="USCensusEst2020">{{cite web |url=https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/buffalocitynewyork/POP010220 |title=QuickFacts: Buffalo city, New York |access-date=2021-08-17}}</ref> Buffalo is the primary city of the [[Buffalo–Niagara Falls metropolitan area]], which had an estimated population of 1.2 million in 2020, making it the [[List of metropolitan statistical areas|49th-largest metro area]] in the U.S. |

|||

'''Buffalo''' is an [[United States|American]] city in [[Western New York|western]] [[New York|New York State]]. As of the census of 2000, the city had a total population of 292,648<ref>[http://www.demographia.com/db-metrocore2005.htm Metropolitan & Central City Population: 2000-2005]. ''Demographia.com'', accessed September 3, 2006.</ref>. It is the state's second-largest city, after [[New York City]], and is the [[county seat]] of [[Erie County, New York|Erie County]].{{GR|6}} It is also the economic and cultural center of the Buffalo-Niagara Region, a diverse [[metropolitan area]] with a population of 1.2 million people <ref>http://www.census.gov/acs/www/Products/Profiles/Single/2000/C2SS/Tabular/380/38000US12801.htm</ref>. Buffalo is also sometimes considered part of the [[Golden Horseshoe]][http://www.carleton.ca/polecon/scale/vance.pdf], an international metropolitan area of over 9.7 million people. |

|||

Before the 17th century, the region was inhabited by nomadic [[Paleo-Indians]] who were succeeded by the [[Neutral Confederacy|Neutral]], [[Erie people|Erie]], and [[Iroquois]] nations. In the early 17th century, the French began to explore the region. In the 18th century, Iroquois land surrounding [[Buffalo River (New York)|Buffalo Creek]] was ceded through the [[Holland Land Purchase]], and a small village was established at its headwaters. In 1825, after its harbor was improved, Buffalo was selected as the terminus of the [[Erie Canal]], which led to its incorporation in 1832. The canal stimulated its growth as the primary [[inland port]] between the Great Lakes and the Atlantic Ocean. [[Transshipment]] made Buffalo the world's largest [[grain trade|grain port]] of that era. After the coming of railroads greatly reduced the canal's importance, the city became the second-largest railway hub (after [[Chicago]]). During the mid-19th century, Buffalo transitioned to manufacturing, which came to be dominated by steel production. Later, [[deindustrialization]] and the opening of the [[St. Lawrence Seaway]] saw the city's economy decline and diversify. It developed its [[service industries]], such as health care, retail, tourism, logistics, and education, while retaining some manufacturing. In 2019, the [[gross domestic product]] of the Buffalo–Niagara Falls MSA was $53 billion (~${{Format price|{{Inflation|index=US-GDP|value=53000000000|start_year=2019}}}} in {{Inflation/year|US-GDP}}). |

|||

Buffalo lies at the eastern end of [[Lake Erie]], at the southern head of the [[Niagara River]], which connects Lake Erie and [[Lake Ontario]]. [[European American|European-Americans]] first settled there in the late-18th century. Growth was slow until the city became the western terminus of the [[Erie Canal]] some forty years later. By the turn of the next century, Buffalo was one of the country's leading cities, and by far its largest inland [[seaport|port]]. The huge [[grain elevator]]s and [[industry|industrial]] plants that the canal spawned began to disappear in the mid-20th century as the [[Saint Lawrence Seaway]] enabled water traffic to bypass the city. |

|||

The city's cultural landmarks include the [[Parks and recreation in Buffalo, New York|oldest urban parks system]] in the United States, the [[Buffalo AKG Art Museum]], the [[Buffalo History Museum]], the [[Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra]], [[Shea's Performing Arts Center]], the [[Buffalo Museum of Science]], and several [[list of festivals in Buffalo, New York|annual festivals]]. Its educational institutions include the [[University at Buffalo]], [[Buffalo State University]], [[Canisius University]], and [[D'Youville University]]. Buffalo is also known for its [[Lake-effect snow|winter weather]], [[Buffalo wing]]s, and three major-league [[Sports in Buffalo|sports teams]]: the National Football League's [[Buffalo Bills]], the National Hockey League's [[Buffalo Sabres]] and the National Lacrosse League's [[Buffalo Bandits]]. |

|||

Distancing itself from its industrial past, Buffalo is redefining itself as a cultural, banking, [[education|educational]], and [[medicine|medical]] center. The city was named by ''[[Reader's Digest]]'' as the third cleanest city in [[United States|America]] in 2005. [http://www.rd.com/content/openContent.do?contentId=15223&pageIndex=3] In 2001 [[USA Today]] named Buffalo the winner of its "City with a Heart" contest, proclaiming it the nation's "friendliest city." Also, in 1996 and 2002, Buffalo won the [[All-America City Award]]. |

|||

== |

==History== |

||

{{ |

{{Main|History of Buffalo, New York}} |

||

{{For timeline}} |

|||

=== Origin of name === |

|||

The City of Buffalo received its name from the [[creek]] that flows through it. However, the origin of the creek's name is unclear, with several unproven theories existing. One holds that the name is an [[Anglicisation|anglicized]] form of the [[France|French]] name ''Beau Fleuve'' (''beautiful river''), which was supposedly an exclamation uttered by [[Louis Hennepin]] when he first saw the stream; this is thought to be unlikely, as no period sources contain this quote. Early French explorers reported the abundance of [[American Bison|buffalo]] on the south shore of Lake Erie, but their presence on the banks of [[Buffalo River (New York)|Buffalo Creek]] is still a matter of debate, so the origin of the name of the creek is still uncertain. Neither the [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]] name ("Place of the Basswoods") or the French name ("River of Horses") survived, so the current name likely dates to the British occupation which began with the capture of [[Fort Niagara]] in 1759. Also given credence by local historians is the possibility that an interpreter mistranslated the Native American word for "[[beaver]]" as "buffalo" - the words being very similar - at a treaty-signing at present-day [[Rome, New York]] in 1784. The theory assumes that because there were beaver here, the creek was probably called Beaver Creek rather than Buffalo Creek. Another theory holds that a [[Seneca nation|Seneca]] Indian lived there, whose name meant "buffalo," and was translated as such by the English pioneers. The stream where he lived became Buffalo Creek. |

|||

===Pre-Columbian era to European exploration=== |

|||

=== Early history === |

|||

[[File:Wenro Territory ca1630 map-en.svg|thumb|left|alt=Color map of New York with Wenro territory highlighted from the mouth of Buffalo Creek east to the Genesee River|Approximate extent of [[Wenrohronon|Wenro]] territory {{Circa|1630}}]] |

|||

Prior to European colonization, the region's inhabitants were the ''Ongiara'', an Iroquois tribe called the ''Neutrals'' by French settlers, who found them helpful in mediating disputes with other tribes. |

|||

Before the [[European colonization of the Americas|arrival of Europeans]], nomadic [[Paleo-Indians]] inhabited the [[western New York]] region from the [[Lithic stage|8th millennium BCE]]. The [[Woodland period]] began around 1000 BC, marked by the rise of the [[Iroquois|Iroquois Confederacy]] and the spread of its tribes throughout the state.<ref name = "Thompson1977 113-120">{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/stream/geographyofnewyo00thom |url-access=registration |title=Geography of New York State |last=Thompson |first=John H. |publisher=[[Syracuse University Press]] |year=1977 |isbn=9780815621829 |pages=113–120 |chapter=The Indian |location=Syracuse, N.Y. |lccn=77004337 |oclc=2874807}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Ritchie |first1=William A. |title=The Archaeology of New York State |date=19 February 2014 |publisher=[[Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group]] |isbn=978-0-307-82049-5 |chapter=The Woodland Stage—Development of Ceramics, Agriculture and Village Life}}</ref> Seventeenth-century [[Jesuit missionaries]] were the first Europeans to visit the area.<ref name="Rundell1962 57-96" /> |

|||

During [[French colonization of the Americas|French exploration of the region]] in 1620, the region was sparsely populated and occupied by the [[Agrarian society|agrarian]] [[Erie people]] in the south and the [[Neutral Nation]] in the north, with a relatively small tribe, the [[Wenrohronon]], between and the [[Seneca people|Senecas]], an Iroquois tribe, occupying the land just east of the region.<ref name = "Thompson1977 113-120"/> The Neutral grew tobacco and [[hemp]] to trade with the Iroquois, who [[North American fur trade|traded furs]] with the French for European goods.<ref name = "Thompson1977 113-120" /> The tribes used animal- and war paths to travel and move goods across what today is New York State. (Centuries later, these same paths were gradually improved, then paved, then developed into major modern roads.)<ref name = "Thompson1977 113-120"/> Traditional Seneca oral legends, as recounted by professional storytellers known as Hagéotâ, were highly participatory. These tales were told only during winter, as they were believed to have the power to put even animals and plants to sleep, which could affect the harvest. At the conclusion, audience members typically offered gifts, such as tobacco, to the storyteller as a sign of appreciation.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Seneca Folk Tales {{!}} Early Americas Digital Archive (EADA) |url=https://eada.lib.umd.edu/text-entries/seneca-folk-tales/ |access-date=2024-10-07 |website=eada.lib.umd.edu}}</ref> During the [[Beaver Wars]] in the mid-17th century the Senecas conquered the Erie and Neutrals in the region.<ref>{{Cite journal |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/20086480 |title=The Indians of the Past and of the Present |journal=[[Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography]] |volume=46 |issue=3 |last=Donehoo |first=George P. |year=1922 |pages=177–198 |jstor=20086480 |access-date=June 11, 2021 |archive-date=June 11, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210611202413/https://www.jstor.org/stable/20086480 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Seneca">{{Cite journal |doi=10.1525/aa.1927.29.2.02a00050 |title=The Migrations of the Seneca Nation |last=Houghton |first=Frederick |date=1927 |journal=[[American Anthropologist]] |pages=241–250 |volume=29 |issue=2 |doi-access = free|issn=0002-7294}}</ref><ref name="AmHeritageBk">{{cite encyclopedia |year=1961 |title=The American Heritage Book of Indians |editor=Alvin M. Josephy, Jr |publisher=[[American Heritage Publishing|American Heritage Publishing Co., Inc.]] |lccn=61-14871 |page=189}}</ref> Native Americans did not settle along Buffalo Creek permanently until 1780, when displaced Senecas were relocated from [[Fort Niagara]].<ref name="Rundell1962 57-96">{{cite book |last1=Rundell |first1=Edwin F. |last2=Stein |first2=Charles W. |title=Buffalo: your city |chapter=Buffalo's Early History—The Village |pages=57–96 |date=1962 |publisher=Henry Stewart, Incorporated |edition=4th |oclc=3023258 |location=[[Buffalo and Erie County Public Library]]}}</ref> |

|||

Most of [[western New York]] was granted by [[Charles II of England]] to the [[Duke of York]] (later known as [[James II of England]]), but the first European settlement in what is now [[Erie County, New York|Erie County]] was by the French, at the mouth of [[Buffalo River (New York)|Buffalo Creek]] in 1758. Its buildings were destroyed a year later by the evacuating French after the British captured Fort Niagara. The British took control of the entire region in 1763, at the conclusion of the [[French and Indian War]]. |

|||

[[Louis Hennepin]] and [[René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle|Sieur de La Salle]] explored the upper Niagara and Ontario regions in the late 1670s.<ref name = "Becker1906 9-24">{{Cite book|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/sketchesofearlyb00beck |title=Sketches of early Buffalo and the Niagara region |chapter=La Salle and The Griffon |pages=9–24 |last=Becker |first=Sophie C. |publisher=McLaughlin Press |year=1906 |location=Buffalo, N.Y. |oclc=12629461}}</ref> In 1679, La Salle's ship, [[Le Griffon]], became the first to sail above Niagara Falls near [[Cayuga Creek]].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Brady |first1=Erik |title=Le Griffon never made it to port but lives on in a Buffalo park and the Canisius mascot |url=https://buffalonews.com/news/local/le-griffon-never-made-it-to-port-but-lives-on-in-a-buffalo-park-and/article_3f8ad5cb-4331-5bae-98b7-ed4da422c0e5.html |url-access=limited |website=[[The Buffalo News]] |access-date=5 June 2021 |language=en |date=July 8, 2019 |archive-date=6 June 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210606062653/https://buffalonews.com/news/local/le-griffon-never-made-it-to-port-but-lives-on-in-a-buffalo-park-and/article_3f8ad5cb-4331-5bae-98b7-ed4da422c0e5.html |url-status=live}}</ref> [[Louis-Armand de Lom d'Arce de Lahontan, Baron de Lahontan|Baron de Lahontan]] visited the site of Buffalo in 1687.<ref name="French&Place1860 279-294" /> A small French settlement along Buffalo Creek lasted for only a year (1758). After the [[French and Indian War]], the region was ruled by Britain.<ref name="Rundell1962 57-96" /> After the [[American Revolution]], the [[Province of New York]]—now a U.S. state—began westward expansion, looking for arable land by following the Iroquois.<ref name = "Thompson1977 407-423">{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/stream/geographyofnewyo00thom |url-access=registration |title=Geography of New York State |last=Thompson |first=John H. |publisher=[[Syracuse University Press]] |year=1977 |isbn=9780815621829 |pages=407–423 |chapter=Buffalo |location=Syracuse, N.Y. |lccn=77004337 |oclc=2874807}}</ref> |

|||

The first permanent white settlers in present day Buffalo were Cornelius Winney and "Black Joe" Hodges, who set up a log cabin store there in 1789 for trading with the Native American community. [[Netherlands|Dutch]] investors purchased the area from the Seneca Indians as part of the [[Holland Purchase]]. Although other Senecas were involved in ceding their land, the most famous today is [[Red Jacket]], who died in Buffalo in 1830. His grave is in [[Forest Lawn Cemetery, Buffalo|Forest Lawn Cemetery]]. Starting in 1801, parcels were sold through the [[Holland Land Company|Holland Land Company's]] office in [[Batavia, New York]]. The settlement was initially called Lake Erie, then Buffalo Creek, soon shortened to Buffalo. Holland Land Company agent [[Joseph Ellicott]] christened it New Amsterdam, but the name did not catch on. In 1808, [[Niagara County, New York|Niagara County]] was established with Buffalo as its county seat. Erie County was formed out of Niagara County in 1821, retaining Buffalo as the county seat. |

|||

New York and [[Massachusetts]] were vying for the territory which included Buffalo, and Massachusetts had the right to purchase all but a one-mile-(1600-meter)-wide portion of land. The rights to the Massachusetts territories were sold to [[Robert Morris (financier)|Robert Morris]] in 1791.<ref name="Sprague1882">{{Cite book |last=Buffalo Historical Society |title=Semi-centennial Celebration of the City of Buffalo: Address of the Hon. E. C. Sprague Before the Buffalo Historical Society, July 3, 1882 |publisher=[[Buffalo Historical Society]] |year=1882 |location=Buffalo, N.Y. |pages=17–21 |language=en}}</ref> Despite objections from Seneca chief [[Red Jacket]], Morris brokered a deal between fellow chief [[Cornplanter]] and the Dutch [[dummy corporation]] [[Holland Land Company]].{{efn|Foreign entities were not allowed to own land in New York State until 1798 (Goldman 1983a, p. 27).}}<ref name="Goldman1983 21-56" /><ref name="Reitano2016 66-96">{{Cite book |last=Reitano |first=Joanne R. |url= |title=New York State: peoples, places, and priorities: a concise history with sources |chapter=The Empire State: 1790–1830 |date=2016 |publisher=[[Routledge]] |isbn=978-1-136-69997-9 |location=New York |pages=66–96 |oclc=918135120 |ref=Reitano2016 |access-date=}}</ref> The [[Holland Land Purchase]] gave the Senecas three reservations, and the Holland Land Company received {{cvt|4000000|acre|km2}} for about thirty-three cents per acre.<ref name="Goldman1983 21-56" /> |

|||

[[Image:Electric_Building_-_Buffalo.jpg|thumb|left|The Electric Building - Buffalo, New York]] |

|||

<!-- this section is missing information on the first burning of the village of New Amsterdam --> |

|||

Permanent white settlers along the creek were prisoners captured during the [[American Revolutionary War|Revolutionary War]].<ref name = "Becker1906 106-117">{{Cite book|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/sketchesofearlyb00beck |title=Sketches of early Buffalo and the Niagara region |chapter=Buffalo Village |pages=106–117 |last=Becker |first=Sophie C. |publisher=McLaughlin Press |year=1906 |location=Buffalo, N.Y. |oclc=12629461}}</ref><ref name="Rundell1962 57-96" /> Early landowners were Iroquois interpreter Captain William Johnston, former enslaved man Joseph "Black Joe" Hodges and Cornelius Winney, a Dutch trader who arrived in 1789.<ref name="Rundell1962 57-96" /><ref name="Bingham1931 132-142">{{cite book |last1=Bingham |first1=Robert W. |title=The cradle of the Queen city: a history of Buffalo to the incorporation of the city |chapter=Captain William Johnston |series=Publications, Buffalo Historical Society,v. 31 |url=https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x000743988 |date=1931 |publisher=[[Buffalo Historical Society]] |location=Buffalo, N.Y. |pages=132–142 |hdl=2027/uva.x000743988 |oclc=364308016 |access-date=June 9, 2021 |archive-date=June 22, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210622041720/https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x000743988 |url-status=live}}</ref> As a result of the war, in which the Iroquois sided with the [[British Army during the American Revolutionary War|British Army]], Iroquois territory was gradually reduced in the late 1700s by European settlers through successive statewide treaties which included the [[Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1784)]] and the [[First Treaty of Buffalo Creek]] (1788).<ref name = "Thompson1977 140-171">{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/stream/geographyofnewyo00thom |url-access=registration |title=Geography of New York State |last=Thompson |first=John H. |publisher=[[Syracuse University Press]] |year=1977 |isbn=9780815621829 |pages=140–171 |chapter=Geography of Expansion |location=Syracuse, N.Y. |lccn=77004337 |oclc=2874807}}</ref> The Iroquois were moved onto reservations, including [[Buffalo Creek Reservation|Buffalo Creek]]. By the end of the 18th century, only {{cvt|338|mi2|acre km2 ha}} of reservations remained.<ref name="Brush1901">{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/iroquoispastpres00brus |page=87 |title=Iroquois Past and Present |last=Brush |first=Edward H. |publisher=Baker, Jones & Co. |year=1901 |location=Buffalo, N.Y.}}</ref> |

|||

=== The 19th century === |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="float:right; margin-left:3px; text-size:80%; text-align:right" |

|||

|align=center colspan=3| '''City of Buffalo <br>Population by year [http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0027.html]''' |

|||

|- |

|||

!Year |

|||

!Population |

|||

!Rank |

|||

|- |

|||

|1830 || 8,668 |

|||

|27 |

|||

|- |

|||

|1840 || 18,213 |

|||

|22 |

|||

|- |

|||

|1850 || 42,261 |

|||

|16 |

|||

|- |

|||

|1860 || 81,129 |

|||

|10 |

|||

|- |

|||

|1870 || 117,714 |

|||

|11 |

|||

|- |

|||

|1880 || 155,134 |

|||

|13 |

|||

|- |

|||

|1890 || 255,664 |

|||

|11 |

|||

|- |

|||

|1900 || 352,387 |

|||

|8 |

|||

|- |

|||

|1910 || 423,715 |

|||

|10 |

|||

|- |

|||

|1920 || 506,775 |

|||

|11 |

|||

|- |

|||

|1930 || 573,076 |

|||

|13 |

|||

|- |

|||

|1940 || 575,901 |

|||

|14 |

|||

|- |

|||

|1950 || 580,132 |

|||

|15 |

|||

|- |

|||

|1960 || 532,759 |

|||

|20 |

|||

|- |

|||

|1970 || 462,768 |

|||

|28 |

|||

|- |

|||

|1980 || 357,870 |

|||

|39 |

|||

|- |

|||

|1990 || 328,123 |

|||

|50 |

|||

|- |

|||

|2000 || 292,648 |

|||

|57 |

|||

|- |

|||

|2005 || 279,745 |

|||

|66 |

|||

|- |

|||

| align="center" colspan="3" | [[List of United States metropolitan statistical areas by population|Current Standing]] |

|||

|} |

|||

After the [[Treaty of Big Tree]] removed Iroquois title to lands west of the [[Genesee River]] in 1797, [[Joseph Ellicott]] surveyed land at the mouth of Buffalo Creek.<ref name = "Becker1906 106-117"/><ref name="Bingham1931 143-165">{{cite book |last1=Bingham |first1=Robert W. |title=The cradle of the Queen city: a history of Buffalo to the incorporation of the city |chapter=The Holland Land Company |series=Publications, Buffalo Historical Society,v. 31 |url=https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x000743988 |date=1931 |publisher=[[Buffalo Historical Society]] |location=Buffalo, N.Y. |pages=132–143 |hdl=2027/uva.x000743988 |oclc=364308016 |access-date=June 9, 2021 |archive-date=June 22, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210622041720/https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x000743988 |url-status=live}}</ref> In the middle of the village was an intersection of eight streets at present-day [[Niagara Square]]. Originally named New Amsterdam, its name was soon changed to Buffalo.<ref name="Fernald1910">{{Cite book |last=Fernald |first=Frederik Atherton |url=https://archive.org/details/indexguidetobuff00fern |title=The index guide to Buffalo and Niagara Falls |date=1910 |publisher=F. A. Fernald |others=[[The Library of Congress]] |location=Buffalo, N.Y. |pages=21 |access-date=November 30, 2017}}</ref> |

|||

In 1804, Joseph Ellicott, a principal agent of the Holland Land Company, designed a radial street and grid system that branches out from downtown like bicycle spokes, and is one of only three radial street patterns in the US. In 1810, the Town of Buffalo was formed from the western part of the [[Clarence, New York|Town of Clarence]]. On December 30, 1813, during the [[War of 1812]], British troops and their Native American allies first captured the village of [[Black Rock, Buffalo, New York|Black Rock]], and then the rest of Buffalo burning most of both to the ground. Buffalo gradually rebuilt itself and by 1816 had a new courthouse. In 1818, the eastern part of the town was lost to form the [[Amherst, New York|Town of Amherst]]. |

|||

=== Erie Canal, grain and commerce === |

|||

Upon the completion of the [[Erie Canal]] in 1825, Buffalo became the western end of the 524-mile waterway starting at [[New York City]]. At the time, Buffalo had a population of about 2,400 people. With the increased commerce of the canal, the population boomed and Buffalo was incorporated as a [[city]] in 1832. In 1853, Buffalo annexed Black Rock, which had been Buffalo's fierce rival for the canal terminus. During the 19th century, thousands of pioneers going to the western United States debarked from canal boats to continue their journey out of Buffalo by lake or [[rail transport]]. During their stopover, many experienced the pleasures and dangers of Buffalo's notorious Canal Street district. |

|||

[[File:Buffalo 1813 (cropped).jpg|thumb|left|alt=Sketch of a harbor in the early 1800s|Buffalo in 1813]] |

|||

The village of Buffalo was named for [[Buffalo River (New York)|Buffalo Creek]].{{Efn|Sources disagree on the creek's etymology.<ref name = "Beautiful">{{cite news |last1=Stefaniuk |first1=Walter |title=You asked us: the 868-3900 line to your desk at The Star: how Buffalo got its name |url=https://www.proquest.com/docview/436693160 |url-access=subscription |access-date=27 May 2021 |work=[[Toronto Star]] |date=September 24, 1992 |location=Toronto, Ont. |page=A7 |language=en |id={{ProQuest|436693160}} }}</ref><ref name = "River">{{cite news |last1=Okun |first1=Janice |title=Worldy setting, sophisticated choices, atmosphere at Beau Fleuve |url=https://www.proquest.com/docview/380815267 |url-access=subscription |access-date=27 May 2021 |work=[[The Buffalo News]] |date=March 19, 1993 |page=G32 |language=en |archive-date=26 November 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141126153049/http://search.proquest.com/docview/380815267 |id={{ProQuest|380815267}} |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Bison">{{cite news |author=Staff |title='Beau Fleuve' story doesn't wash |url=https://www.proquest.com/docview/381587989 |url-access=subscription |work=[[The Buffalo News]] |date=July 21, 1993 |page=B9 |access-date=May 29, 2021 |archive-date=May 27, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210527025137/https://www.proquest.com/docview/381587989 |id={{ProQuest|381587989}} |url-status=live }}</ref> Although its name possibly originated from French fur traders and Native Americans calling the creek ''Beau Fleuve'' ([[French language|French]] for "beautiful river"),<ref name="Beautiful"/><ref name="River"/> Buffalo Creek may have been named after the [[American bison|American buffalo]] (whose range may have extended into Western New York).<ref name="Bison"/><ref name="Bison_range">{{cite book |last1=Hornaday |first1=William T. |author-link=William Temple Hornaday |title=[[The Extermination of the American Bison]] |date=1889 |publisher=[[Government Printing Office]] |location=Washington D.C. |pages=385–386 |chapter-url=https://www.gutenberg.org/files/17748/17748-h/17748-h.htm#ii_geographical_distribution |access-date=August 20, 2015 |chapter=Geographic Distribution |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924203028/http://www.gutenberg.org/files/17748/17748-h/17748-h.htm#ii_geographical_distribution |archive-date=September 24, 2015}}</ref><ref name="Sprague1882" />}}<ref name = "Ketchum1865">{{cite book |last1=Ketchum |first1=William |author-link=William Ketchum (mayor) |title=An Authentic and Comprehensive History of Buffalo, with Some Account of Its Early Inhabitants, Both Savage and Civilized, Comprising Historic Notices of the Six Nations, Or Iroquois Indians, Vol. II |pages=63–65, 141 |chapter=Origin of the Name of Buffalo |date=1865 |publisher=Rockwell, Baker & Hill |location=Buffalo, N.Y. |isbn=9780665514968 |oclc=49073883}}</ref> British military engineer [[John Montresor]] referred to "Buffalo Creek" in his 1764 journal, the earliest recorded appearance of the name.<ref name="google">{{cite book |title=Buffalo Historical Society Publications |chapter=The Achievements of Captain John Montresor |author=Severance, Frank H. |author-link=Frank Severance |editor=[[Buffalo Historical Society]] |location=Buffalo, NY |date=1902 |publisher=Bigelow Brothers |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pBs8AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA15 |page=15 |access-date=August 14, 2015 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150916180643/https://books.google.com/books?id=pBs8AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA15 |archive-date=September 16, 2015}}</ref> A road to [[Pennsylvania]] from Buffalo was built in 1802 for migrants traveling to the [[Connecticut Western Reserve]] in Ohio.<ref name="French&Place1860 208-217">{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/gazetteerofstate04fren |title=Gazetteer of the State of New York |chapter=Chautauque County |pages=208–217 |last1=French |first1=J. H. |last2=Place |first2=Frank |publisher=R. Pearsall Smith |year=1860 |location=Syracuse, N.Y. |oclc=682410715}} |

|||

</ref> Before an east–west turnpike across the state was completed, traveling from Albany to Buffalo would take a week; a trip from nearby [[Williamsville, New York|Williamsville]] to Batavia could take over three days.<ref name="Turner1849">{{cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/pioneerhistoryof1849inturn |title=Pioneer history of the Holland Purchase of western New York |pages=401, 439, 494–495, 498 |last=Turner |first=Orsamus |publisher=Jewett, Thomas & Co. |year=1849 |location=Buffalo, N.Y. |oclc=14246512}}</ref>{{Efn|When traveling with an ox and wagon team.}} |

|||

British forces [[Battle of Buffalo|burned Buffalo]] and the northwestern village of [[Black Rock, Buffalo|Black Rock]] in 1813.<ref>{{Cite book |title=The U.S. Army in the War of 1812: An Operational and Command Study |last=Quimby |first=Robert |publisher=[[Michigan State University Press]] |year=1997 |isbn=978-0-87013-441-8 |oclc=868964185 |location=East Lansing, MI |pages=355}}</ref> The battle and subsequent fire was in response to the destruction of [[Niagara-on-the-Lake]] by American forces and other skirmishes during the [[War of 1812]].<ref>{{Cite news |last=Hammill |first=Luke |url=http://buffalonews.com/2017/11/29/the-buffalo-of-yesteryear-chictawauga-scajaquady-and-other-oddities-of-the-year-1860/ |url-access=limited |title=The Buffalo of Yesteryear: Chictawauga, Scajaquady and the 'morass' that was Buffalo |date=November 29, 2017 |work=[[The Buffalo News]] |access-date=November 29, 2017 |language=en-US |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171129200743/http://buffalonews.com/2017/11/29/the-buffalo-of-yesteryear-chictawauga-scajaquady-and-other-oddities-of-the-year-1860/ |archive-date=November 29, 2017}}</ref><ref name = "Becker1906 118-132">{{Cite book|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/sketchesofearlyb00beck |title=Sketches of early Buffalo and the Niagara region |chapter=The Burning of Buffalo |pages=118–132 |last=Becker |first=Sophie C. |publisher=McLaughlin Press |year=1906 |location=Buffalo, N.Y. |oclc=12629461}}</ref><ref name="Rundell1962 57-96" /> Rebuilding was swift, completed in 1815.<ref name="Severance1879">{{Cite book|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/publicationsofbu09seve |title=Publications of the Buffalo Historical Society |last=Severance |first=Frank H. |author-link=Frank Severance |location=Buffalo |publisher=Bigelow Bros. |others=Harold B. Lee Library |year=1879 |pages=334–356 |chapter=Papers relating to the Burning of Buffalo}}</ref><ref name = "Becker1906 118-132"/> As a remote outpost, village residents hoped that the proposed [[Erie Canal]] would bring prosperity to the area.<ref name="Goldman1983 21-56" /> To accomplish this, Buffalo's harbor was expanded with the help of [[Samuel Wilkeson]]; it was selected as the canal's terminus over the rival Black Rock.<ref name="Rundell1962 57-96" /> It opened in 1825, ushering in commerce, manufacturing and [[hydropower]].<ref name="Goldman1983 21-56" /> By the following year, the {{cvt|130|sqmi|km2|adj=on}} Buffalo Creek Reservation (at the western border of the village) was transferred to Buffalo.<ref name="Brush1901" /> Buffalo was incorporated as a city in 1832.<ref name="NPSBuffaloTimeline">{{Cite web |url=http://www.nps.gov/thri/buffalotimeline.htm |title=A Brief Chronology of the Development of the City of Buffalo |access-date = October 29, 2014 |website=[[National Park Service]] |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20141104091901/http://www.nps.gov/thri/buffalotimeline.htm |archive-date = November 4, 2014 |df=mdy-all}}</ref> During the 1830s, businessman [[Benjamin Rathbun]] significantly expanded its business district.<ref name="Goldman1983 21-56">{{Cite book |title=High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York |chapter=Ups and Downs during the Early Years of the Nineteenth Century |pages=21–56 |last=Goldman |first=Mark |publisher=[[State University of New York Press]] |year=1983a |isbn=9780873957342 |location=Albany, N.Y. |oclc=09110713}}</ref> The city doubled in size from 1845 to 1855. Almost two-thirds of the city's population was foreign-born, largely a mix of unskilled (or educated) [[Irish Americans|Irish]] and [[German Americans|German]] [[Catholic Church|Catholics]].<ref name="Goldman1983 72-97" /><ref name="Rundell1962 97-125">{{cite book |last1=Rundell |first1=Edwin F. |last2=Stein |first2=Charles W. |title=Buffalo: your city |chapter=Buffalo Becomes a Great City |pages=97–125 |date=1962 |publisher=Henry Stewart, Incorporated |edition=4th |oclc=3023258 |location=[[Buffalo and Erie County Public Library]]}}</ref> |

|||

Buffalo was a terminus of the [[Underground Railroad]], an informal series of safe houses for [[African-Americans]] escaping slavery in the mid-19th century. Buffalonians helped many fugitives cross the [[Niagara River]] to [[Fort Erie, Ontario]], [[Canada]] and freedom. |

|||

[[Fugitive slaves in the United States|Fugitive slaves]] made their way north to Buffalo during the 1840s.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Wesley |first1=Charles H. |author-link=Charles H. Wesley |title=The Participation of Negroes in Anti-Slavery Political Parties |journal=[[The Journal of Negro History]] |date=Jan 1944 |volume=29 |issue=1 |pages=43–44, 51–52, 55, 65 |jstor=2714753 |doi=10.2307/2714753 |s2cid=149675414}}</ref> Buffalo was a terminus of the [[Underground Railroad]], with many free Black people crossing the [[Niagara River]] to [[Fort Erie, Ontario]];<ref>{{Cite book |title=Underground Railroad in New York and New Jersey |publisher=[[Stackpole Books]] |date=May 14, 2014 |isbn=9780811746298 |first=William J. |last=Switala |page=126}}</ref> others remained in Buffalo.<ref name="Goldman1983 72-97">{{Cite book |title=High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York |chapter=Ethnics: Germans, Irish and Blacks |pages=72–97 |last=Goldman |first=Mark |publisher=[[State University of New York Press]] |year=1983 |isbn=9780873957342 |location=Albany, N.Y. |oclc=09110713}}</ref> During this time, Buffalo's port continued to develop. Passenger and commercial traffic expanded, leading to the creation of feeder canals and the expansion of the city's harbor.<ref name="Goldman1983 56-71" /> Unloading grain in Buffalo was a laborious job, and grain handlers working on [[lake freighter]]s would make $1.50 a day ({{Inflation|US|1.50|1845|fmt=eq}}{{Inflation/fn|US}}) in a six-day work week.<ref name="Goldman1983 56-71" /> Local inventor [[Joseph Dart]] and engineer [[Robert Dunbar]] created the [[grain elevator]] in 1843, adapting the steam-powered elevator. [[Dart's Elevator]] initially processed one thousand [[bushel]]s per hour, speeding global distribution to consumers.<ref name="Goldman1983 56-71">{{Cite book |title=High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York |chapter=The Impact of Commerce and Manufacturing on Mid-Nineteenth Century Buffalo |pages=56–71 |last=Goldman |first=Mark |publisher=[[State University of New York Press]] |year=1983 |isbn=9780873957342 |location=Albany, N.Y. |oclc=09110713}}</ref> Buffalo was the transshipment hub of the Great Lakes, and weather, maritime and political events in other Great Lakes cities had a direct impact on the city's economy.<ref name="Goldman1983 56-71" /> In addition to grain, Buffalo's primary imports included agricultural products from the Midwest (meat, whiskey, lumber and tobacco), and its exports included leather, ships and iron products. The mid-19th century saw the rise of new manufacturing capabilities, particularly with iron.<ref name="Goldman1983 56-71" /> |

|||

===The presidential connection=== |

|||

Several [[President of the United States|U.S. presidents]] had connections with Buffalo. [[Millard Fillmore]] took up permanent residence in Buffalo in 1822 before he became America's 13th president. He was also the first chancellor of the University of Buffalo, now known as [[University at Buffalo, The State University of New York|SUNY University at Buffalo]]. [[Grover Cleveland]], the 22nd and 24th President of the United States, lived in Buffalo from 1854 until 1882, and served as Buffalo's mayor from 1882 until 1883. [[William McKinley]] was shot by [[Leon Czolgosz]] on September 6, 1901 at the [[Pan-American Exposition]] in Buffalo, and died in Buffalo on the 14th. [[Theodore Roosevelt]] was then sworn in on September 14th, 1901 at the Ansley Wilcox Mansion, now the [[Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site]], becoming one of the few presidents to be sworn in outside of [[Washington, D.C.]]. |

|||

By the 1860s, many railroads terminated in Buffalo; they included the [[Buffalo, Bradford and Pittsburgh Railroad]], [[Buffalo and Erie Railroad]], the [[New York Central Railroad]], and the [[Lehigh Valley Railroad]].<ref name="French&Place1860 279-294">{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/gazetteerofstate04fren |title=Gazetteer of the State of New York |chapter=Erie County |pages=279–294 |last1=French |first1=J. H. |last2=Place |first2=Frank |publisher=R. Pearsall Smith |year=1860 |location=Syracuse, N.Y. |oclc=682410715}}</ref> During this time, Buffalo controlled one-quarter of all shipping traffic on Lake Erie.<ref name="French&Place1860 279-294"/> After the [[American Civil War|Civil War]], canal traffic began to drop as railroads expanded into Buffalo.<ref name="Goldman1983 124-142">{{Cite book |title=High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York |chapter=The Coming of Industry |pages=124–142 |last=Goldman |first=Mark |publisher=[[State University of New York Press]] |year=1983 |isbn=9780873957342 |location=Albany, N.Y. |oclc=09110713}}</ref> Unionization began to take hold in the late 19th century, highlighted by [[Great Railroad Strike of 1877|the Great Railroad Strike of 1877]] and [[Buffalo switchmen's strike|1892 Buffalo switchmen's strike]].<ref name="Goldman1983 143-175">{{Cite book |title=High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York |chapter=The Response to Industrialization: Life and Labor, Values and Beliefs |pages=143–175 |last=Goldman |first=Mark |publisher=[[State University of New York Press]] |year=1983 |isbn=9780873957342 |location=Albany, N.Y. |oclc=09110713}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Buffalo_City_Hall_-_001.jpg|thumb|220px|left|The city hall of Buffalo, NY - an art deco masterpiece]] |

|||

=== <span class="anchor" id="Steel, challenges and modern era"></span>Steel, challenges, and the modern era === |

|||

=== The 20th century === |

|||

[[File:Pan-American Exposition, Buffalo, 1901 (cropped).jpg|thumb|left|alt=Aerial view of the Pan-American Exposition|Pan-American Exposition, 1901]] |

|||

At the turn of the century, Buffalo was a growing city with a burgeoning [[economy]]. Immigrants came from [[Ireland]], [[Italy]], [[Germany]], and [[Poland]] to work in the [[Steel mill|steel]] and [[grain mill]]s which had taken advantage of the city's critical location at the junction of the [[Great Lakes]] and the Erie Canal. [[Hydroelectric power]] harnessed from nearby [[Niagara Falls]] made Buffalo the first American city to have widespread [[Incandescent light bulb|electric lighting]] yielding it the nickname, the "''City of Light''". Electricity was used to dramatic effect at the [[Pan-American Exposition]] in 1901. The Pan-American was also notable for being the scene of the aforementioned assassination of [[William McKinley|President William McKinley]]. |

|||

At the start of the 20th century, Buffalo was the world's leading grain port and a national flour-milling hub.<ref name="Goldman1983 196-223" /> Local mills were among the first to benefit from [[hydroelectricity]] generated by the Niagara River. Buffalo hosted the 1901 [[Pan-American Exposition]] after the [[Spanish–American War]], showcasing the nation's advances in art, architecture, and electricity. Its centerpiece was the Electric Tower, with over two million light bulbs, but some exhibits were [[jingoistic]] and racially charged.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Bewley |first1=Michele Ryan |title=The New World in Unity: Pan-America Visualized at Buffalo in 1901 |journal=[[New York History]] |date=2003 |volume=84 |issue=2 |pages=179–203 |jstor=23183322 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/23183322 |url-access=subscription |access-date=8 June 2021 |issn=0146-437X |archive-date=June 8, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210608081958/https://www.jstor.org/stable/23183322 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Goldman1983 3-20">{{Cite book |title=High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York |chapter=The Pan American Exposition: World's Fair as Historical Metaphor |pages=3–20 |last=Goldman |first=Mark |publisher=[[State University of New York Press]] |year=1983 |isbn=9780873957342 |location=Albany, N.Y. |oclc=09110713}}</ref><ref name="Reitano2016 162-191">{{Cite book |last=Reitano |first=Joanne R. |url= |title=New York State: peoples, places, and priorities: a concise history with sources |date=2016 |publisher=[[Routledge]] |isbn=978-1-136-69997-9 |location=New York |chapter=The Progressive State: 1900–28 |pages=162–191 |oclc=918135120 |ref=Reitano2016 |access-date=}}</ref> At the exposition, President [[William McKinley]] was [[Assassination of William McKinley|assassinated]] by [[anarchist]] [[Leon Czolgosz]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Markwyn |first1=Abigail |title=Spectacle and Politics in Buffalo and Philadelphia: The World's Fairs of 1901 and 1926 |journal=[[Reviews in American History]] |date=2018 |volume=46 |issue=4 |pages=624–630 |doi=10.1353/rah.2018.0094 |s2cid=150181280 |url=https://muse.jhu.edu/article/711872 |url-access=subscription |access-date=5 June 2021}}</ref> When McKinley died, [[Theodore Roosevelt]] was sworn in at the [[Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site|Wilcox Mansion]] in Buffalo.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Gee |first1=Derek |title=A Closer Look: Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural Site |url=https://buffalonews.com/multimedia/a-closer-look-theodore-roosevelt-inaugural-site/collection_cd666c13-cf48-5682-82dd-8a0de07e9690.html#3 |website=[[The Buffalo News]] |access-date=5 June 2021 |url-access=limited |language=en |date=February 24, 2021 |archive-date=6 June 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210606062654/https://buffalonews.com/multimedia/a-closer-look-theodore-roosevelt-inaugural-site/collection_cd666c13-cf48-5682-82dd-8a0de07e9690.html#3 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

The opening of the [[Peace Bridge]] linking Buffalo with [[Fort Erie, Ontario]] on August 7, 1927 was an occasion for significant celebrations. Those in attendance included Edward, [[Prince of Wales]] (later to become [[Edward VIII of the United Kingdom|Edward VIII]]), his brother Prince Albert George (later [[George VI of the United Kingdom|George VI]]), [[United Kingdom|British]] [[Prime Minister of the United Kingdom|Prime Minister]] [[Stanley Baldwin]], [[Prime Minister of Canada]] [[William Lyon Mackenzie King]], [[Vice President of the United States]] [[Charles G. Dawes]], and New York Governor [[Alfred E. Smith]]. |

|||

Attorney [[John G. Milburn|John Milburn]] and local industrialists convinced the [[Lackawanna Iron and Steel Company]] to relocate from [[Scranton, Pennsylvania]] to the town of [[West Seneca, New York|West Seneca]] in 1904. Employment was competitive, with many Eastern Europeans and Scrantonians vying for jobs.<ref name="Goldman1983 124-142" /> From the late 19th century to the 1920s, [[mergers and acquisitions]] led to distant ownership of local companies; this had a negative effect on the city's economy.<ref name = "Dillaway2006 25-39">{{Cite book |title=Power failure: politics, patronage, and the economic future of Buffalo, New York |chapter=Economic Power |pages=25–39 |last=Dillaway |first=Diana |date=2006 |publisher=[[Prometheus Books]] |isbn=978-1591024002 |location=Amherst, N.Y.}}</ref><ref name="Rundell1962 149-172" /> Examples include the acquisition of Lackawanna Steel by [[Bethlehem Steel]] and, later, the relocation of [[Curtiss-Wright]] in the 1940s.<ref name="Reitano2016">{{Cite book |last=Reitano |first=Joanne R. |url= |title=New York State: peoples, places, and priorities: a concise history with sources |date=2016 |publisher=[[Routledge]] |isbn=978-1-136-69997-9 |location=New York |chapter=The Stressed State: 1954–75 |pages=223–252 |oclc=918135120 |ref=Reitano2016 |access-date=}}</ref> The [[Great Depression]] saw severe unemployment, especially among the working class. [[New Deal]] relief programs operated in full force, and the city became a stronghold of labor unions and the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic Party]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Plesur |first1=Milton |last2=Adler |first2=Selig |last3=Lansky |first3=Lewis |title=An American historian: essays to honor Selig Adler |date=1980 |publisher=[[State University of New York at Buffalo]] |location=Buffalo, N.Y. |pages=204–213 |chapter=Buffalo and the Great Depression, 1929–1933 |oclc=6984440}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:BuffaloNY1922.jpg|thumb|Main Street and Lafayette Square, Buffalo, from a 1922 postcard]] |

|||

[[File:Thornberger hoists unloading ore, Lackawanna ore docks, Buffalo, N.Y. LC-D4-32179.jpg|thumb|alt=A black-and-white photograph of iron-ore rail cars at a ship dock|Iron ore unloaded at Buffalo, {{Circa|1900}}]] |

|||

Buffalo's [[Buffalo City Hall|City Hall]], an [[Art Deco]] masterpiece, was dedicated on July 1, 1932. It was the city's tallest building until 1970. |

|||

During [[World War II]], Buffalo regained its manufacturing strength as military contracts enabled the city to manufacture steel, chemicals, aircraft, trucks and ammunition.<ref name="Reitano2016" /> The [[1950 United States Census#City rankings|15th-most-populous US city in 1950]], Buffalo's economy relied almost entirely on manufacturing; eighty percent of area jobs were in the sector.<ref name="Reitano2016" /> The city also had over a dozen railway terminals, as railroads remained a significant industry.<ref name="Rundell1962 149-172">{{cite book |last1=Rundell |first1=Edwin F. |last2=Stein |first2=Charles W. |title=Buffalo: your city |chapter=Buffalo—Center of Commerce and Industry |pages=149–172 |date=1962 |publisher=Henry Stewart, Incorporated |edition=4th |oclc=3023258 |location=[[Buffalo and Erie County Public Library]]}}</ref> |

|||

The [[St. Lawrence Seaway]] was proposed in the 19th century as a faster shipping route to Europe, and later as part of a bi-national hydroelectric project with Canada.<ref name="Reitano2016" /> Its combination with an expanded [[Welland Canal]] led to a grim outlook for Buffalo's economy. After its 1959 opening, the city's port and barge canal became largely irrelevant. Shipbuilding in Buffalo wound down in the 1960s due to reduced waterfront activity, ending an industry which had been part of the city's economy since 1812.<ref name="Goldman1983 242-266">{{Cite book |title=High hopes: the rise and decline of Buffalo, New York |chapter=Paranoia: The Fear of Outsiders and Radicals During the 1950s and 1960s |pages=242–266 |last=Goldman |first=Mark |publisher=[[State University of New York Press]] |year=1983 |isbn=9780873957342 |location=Albany, N.Y. |oclc=09110713}}</ref> Downsizing of the steel mills was attributed to the threat of higher wages and unionization efforts.<ref name="Reitano2016" /> Racial tensions culminated in [[1967 Buffalo riot|riots in 1967]].<ref name="Reitano2016" /> [[Suburbanization]] led to the selection of the town of [[Amherst, New York|Amherst]] for the new [[University at Buffalo]] campus by 1970.<ref name="Reitano2016" /> Unwilling to modernize its plant, Bethlehem Steel began cutting thousands of jobs in Lackawanna during the mid-1970s before closing it in 1983.<ref name="Dillaway2006 25-39" /> The region lost at least 70,000 jobs between 1970 and 1984.<ref name="Dillaway2006 25-39" /> Like much of the [[Rust Belt]], Buffalo has focused on recovering from the effects of late-20th-century [[deindustrialization]].<ref name="Deindustrialization">{{cite journal |last1=Hobor |first1=George |title=Surviving the Era of Deindustrialization: The New Economic Geography of the Urban Rust Belt |journal=Journal of Urban Affairs |date=1 October 2013 |volume=35 |issue=4 |pages=417–434 |doi=10.1111/j.1467-9906.2012.00625.x |s2cid=154777044}}</ref> |

|||

The city's importance declined in the later half of the 20th century for several reasons, perhaps the most devastating being the opening of the [[St. Lawrence Seaway]] in 1957. Goods which had previously passed through Buffalo could now bypass it using a series of canals and locks, reaching the ocean via the [[St. Lawrence River]]. Another major toll was [[Suburbanization|suburban migration]], a national trend at the time. The city, which boasted over half a million people at its peak, has seen its population decline by some 50%, as industries shut down and people left the [[Rust Belt]] for the employment opportunities of the South and West. Erie County has lost population in every census year since 1970. The city also has the dubious distinction along with [[St. Louis, Missouri]] of being one of the few American cities to have had fewer people in the year 2000 than in 1900. |

|||

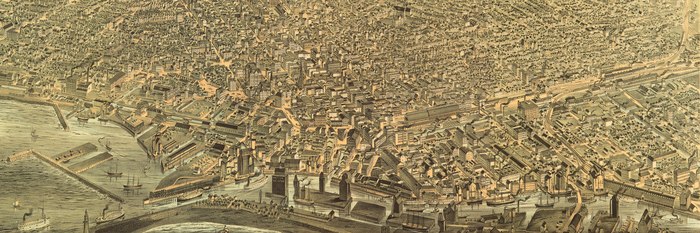

{{wide image|Buffalo waterfront 1880.tif|700px|alt=Aerial view of downtown Buffalo and its waterfront in 1880|Panorama of downtown Buffalo and its waterfront in 1880|align-cap=center}} |

|||

=== The 21st century === |

|||

On July 3, 2003, at the climax of a fiscal crisis, the Buffalo Fiscal Stability Authority was established[http://www.bfsa.state.ny.us/] to oversee the finances of the city. As a "hard control board," they have frozen the wages of city employees and must approve or reject all major expenditures. After a period of severe financial stress, Erie County, where Buffalo resides, was assigned a Fiscal Stability Authority on July 12, 2005. As a "soft control board," however, they act only in an advisory capacity.[http://www.ecfsa.state.ny.us]. Both Authorities were established by [[New York State]]. In November of 2005, [[Byron Brown]] was elected Mayor of Buffalo. He is the first African-American to hold this office. |

|||

==Geography== |

==Geography== |

||

=== Topography === |

|||

[[Image:Erie-Buffalo.png|right|thumb|175px|Position within Erie County.]] |

|||

[[File:NiagaraRiverNASA.jpg|thumb|left|Satellite image of the [[Niagara Peninsula]] and [[Niagara Frontier]]; Buffalo is at the lower right.|alt=A satellite photo shows two bodies of water and two peninsulas from space]] |

|||

Buffalo is located on the eastern end of [[Lake Erie]], opposite [[Fort Erie, Ontario]] in Canada, and at the beginning of the [[Niagara River]], which flows northward over [[Niagara Falls]] and into [[Lake Ontario]]. It is located at 42°54'17" North, 78°50'58" West (42.904657, -78.849405){{GR|1}}. |

|||

Buffalo is on the eastern end of [[Lake Erie]] opposite [[Fort Erie, Ontario]]. It is at the head of the Niagara River, which flows north over [[Niagara Falls]] into [[Lake Ontario]]. |

|||

The Buffalo metropolitan area is on the Erie/Ontario Lake Plain of the [[Eastern Great Lakes Lowlands]], a narrow [[plain]] extending east to [[Utica, New York]].<ref name = "Thompson1977 19-54"/><ref name="USGSMap" /> The city is generally flat, except for elevation changes in the University Heights and Fruit Belt neighborhoods.<ref>{{cite web |title=ACME Mapper 2.2: University Heights (689 feet) |url=https://mapper.acme.com/?ll=42.90311,-78.85904&z=17&t=T&marker0=42.90472%2C-78.84944%2CBuffalo%2C%20New%20York |website=ACME Mapper (Map) |access-date=8 June 2021 |archive-date=June 8, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210608195127/https://mapper.acme.com/?ll=42.90311,-78.85904&z=17&t=T&marker0=42.90472,-78.84944,Buffalo,%20New%20York |url-status=live}} and {{cite web |title=ACME Mapper 2.2: Fruit Belt (682 feet) |url=https://mapper.acme.com/?ll=42.90311,-78.85904&z=17&t=T&marker0=42.90472%2C-78.84944%2CBuffalo%2C%20New%20York |website=ACME Mapper (Map) |access-date=8 June 2021 |archive-date=June 8, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210608195127/https://mapper.acme.com/?ll=42.90311,-78.85904&z=17&t=T&marker0=42.90472,-78.84944,Buffalo,%20New%20York |url-status=live}}</ref> The [[Southtowns]] are hillier, leading to the Cattaraugus Hills in the [[Allegheny Plateau|Appalachian Upland]].<ref name = "Thompson1977 19-54">{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/stream/geographyofnewyo00thom |url-access=registration |title=Geography of New York State |last=Thompson |first=John H. |publisher=[[Syracuse University Press]] |year=1977 |isbn=9780815621829 |pages=19–54 |chapter=Land Forms |location=Syracuse, N.Y. |lccn=77004337 |oclc=2874807}}</ref><ref name = "USGSMap">{{cite map |first1=S. A. |last1=Bryce |first2=G. E. |last2=Griffith |first3=J. M. |last3=Omernik |first4=G. |last4=Edinger |first5=S. |last5=Indrick |first6=O. |last6=Vargas |first7=D. |last7=Carlson |title=Ecoregions of New York (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photograph)|trans-title = |map=|map-url = |date= |year=2010 |url=http://ecologicalregions.info/data/ny/NY_front.pdf |scale=1:1,250,000 |publisher=[[U.S. Geological Survey]] |location=Reston, VA |language= |access-date = |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210526063146/http://ecologicalregions.info/data/ny/NY_front.pdf |archive-date = May 26, 2021 |url-status = live}}</ref> Several types of shale, limestone and [[lagerstätte]]n are prevalent in Buffalo and its surrounding area, lining their [[stream bed]]s.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/ldpd_6985187_000 |title=Geologic map of the Buffalo quadrangle |last=Luther |first=D. D. |date=1906 |pages=12–13 |publisher=[[New York State Education Department]] |others=[[Columbia University Libraries]] |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

According to the [[United States Census Bureau]], the city has a total area of 136.0 [[square kilometre|km²]] (52.5 [[square mile|mi²]]). 105.2 km² (40.6 mi²) of it is land and 30.8 km² (11.9 mi²) of it is water. The total area is 22.66% water. |

|||

According to [[Fox Weather]], Buffalo is one of the top five snowiest large cities in the country, receiving, on average, 95 inches of snow annually. |

|||

==Climate== |

|||

{{wikinews|"Friday the 13" Buffalo, New York snow storm in pictures}} |

|||

Buffalo has a reputation for snowy winters. The region experiences a fairly humid, [[continental climate|continental-type]] climate, but with a definite [[maritime climate|maritime]] flavor due to strong modification from the [[Great Lakes]]. The transitional seasons are very brief in Buffalo and Western New York. |

|||

Although the city has not experienced any recent or significant [[earthquake]]s, Buffalo is in the [[Southern Great Lakes Seismic Zone]] (part of the [[Great Lakes tectonic zone]]).<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.buffalo.edu/news/releases/2000/03/4637.html |title=UB Geologists Find Evidence That Upstate New York Is Criss-Crossed By Hundreds Of Faults - University at Buffalo |website=[[University at Buffalo]] |language=en |access-date=January 11, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180112100857/http://www.buffalo.edu/news/releases/2000/03/4637.html |archive-date=January 12, 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Dineva |first1=S. |title=Seismicity of the Southern Great Lakes: Revised Earthquake Hypocenters and Possible Tectonic Controls |journal=[[Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America]] |date=2004-10-01 |volume=94 |issue=5 |pages=1902–1918 |doi=10.1785/012003007 |bibcode=2004BuSSA..94.1902D}}</ref> Buffalo has four [[Channel (geography)|channels]] within its boundaries: the Niagara River, Buffalo River (and Creek), [[Scajaquada Creek]], and the [[Black Rock Canal]], adjacent to the Niagara River.<ref name = "Smith1884">{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/historyofcityofb01smit/page/n23 |title=History of the city of Buffalo and Erie County: with ... biographical sketches of some of its prominent men and pioneers ... |last=Smith |first=Henry Perry |publisher=D. Mason & Co. |year=1884 |location=Syracuse, N.Y. |page=16}}</ref> The city's Bureau of Forestry maintains a database of over seventy thousand trees.<ref>{{cite web |title=TreeKeeper 8 System for Buffalo, NY |url=https://buffalony.treekeepersoftware.com/index.cfm?deviceWidth=2133 |website=City of Buffalo Bureau of Forestry |access-date=26 May 2021 |archive-date=May 26, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210526060957/https://buffalony.treekeepersoftware.com/index.cfm?deviceWidth=2133 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:BuffaloAvgTemps.png|left]] |

|||

According to the [[United States Census Bureau]], Buffalo has an area of {{cvt|52.5|sqmi|km2}}; {{cvt|40.38|sqmi|km2}} is land, and the rest is water.<ref name="2019USCensusQuickFacts" /> The city's total area is 22.66 percent water. In 2010, its population density was 6,470.6 per square mile.<ref name="2019USCensusQuickFacts" /> |

|||

[[Winter]]s in Western New York are generally cold and [[snowstorm|snowy]], but are changeable and include frequent thaws and [[rain]] as well. [[Snow]] covers the ground more often than not from Christmas into early March, but periods of bare ground are not uncommon. Over half of the annual snowfall comes from the [[lake effect snow|lake effect]] process and is very localized. [[Lake effect]] snow occurs when cold air crosses the relatively warm lake waters and becomes saturated, creating [[clouds]] and [[precipitation (meteorology)|precipitation]] downwind. Due to the prevailing [[winds]], areas south of Buffalo receive much more lake effect snow than locations to the north. The lake snow machine can start as early as mid October, peaks in December, then virtually shuts down after [[Lake Erie]] freezes in mid to late January. The most well-known snow storm in Buffalo's history, the [[Great Lakes Blizzard of 1977]], resulted from a combination of lake effect snow and high winds. Snow does not typically impair the city's operation, but can cause significant damage as with [[Lake Storm "Aphid"]]. |

|||

===Cityscape=== |

|||

Buffalo has the sunniest and driest summers of any major city in the [[Northeastern United States|Northeast]], but still has enough rain to keep [[vegetation]] green and lush.<ref>[http://www.erh.noaa.gov/buf/bufclifo.htm Buffalo's Climate]. ''National Weather Service''. Accessed July 5, 2006.</ref> Summers are marked by plentiful sunshine and moderate [[humidity]] and temperature. Obscured by the attention given to winter snowstorms is the fact that Buffalo benefits from other lake effects; namely free, natural air conditioning from Lake Erie. As a result, summers are often filled with gentle southwest breezes off the lake that temper the warmest days. Buffalo has never recorded a 100°F temperature, a distinction it shares with but a few other major metropolitan areas in the US (ironically, two of the others are [[Miami, Florida]] and [[Honolulu, Hawaii]]). Rainfall is moderate but typically occurs at night. The stabilizing effect of Lake Erie continues to inhibit [[thunderstorms]] and enhance sunshine in the immediate Buffalo area through most of July. August usually has more showers and is humid as the warmer lake loses its temperature-stabilizing influence. |

|||

{{see also|List of tallest buildings in Buffalo, New York|Architecture of Buffalo, New York}} |

|||

Buffalo's architecture is diverse, with a collection of 19th- and 20th-century buildings.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/16/arts/design/16ouro.html |url-access=limited |title=Saving Buffalo's Untold Beauty |last=Ouroussoff |first=Nicolai |author-link=Nicolai Ouroussoff |date=November 14, 2008 |work=[[The New York Times]] |access-date = September 19, 2014 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20141006193136/http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/16/arts/design/16ouro.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 |archive-date = October 6, 2014 |df=mdy-all}}</ref> Downtown Buffalo landmarks include [[Louis Sullivan]]'s [[Prudential (Guaranty) Building|Guaranty Building]], an early skyscraper;<ref>{{Cite web |title=Louis Sullivan still has a skyscraper in Buffalo, but Chicago has none |first=Blair |last=Kamin |author-link=Blair Kamin |website=[[Chicago Tribune]] |date=September 1, 2013 |url=http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2013-09-01/news/ct-met-kamin-sullivanbuffalo-0901-20130902_1_skyscrapers-auditorium-building-wainwright-building |access-date = September 23, 2015 |url-access = limited |url-status = dead |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20150925090648/http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2013-09-01/news/ct-met-kamin-sullivanbuffalo-0901-20130902_1_skyscrapers-auditorium-building-wainwright-building |archive-date = September 25, 2015 |df=mdy-all}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.nps.gov/tps/how-to-preserve/tech-notes/Tech-Notes-Mechanical01.pdf |title=Preservation Tech Notes: Guaranty Building |date=June 1989 |access-date = September 23, 2015 |website=[[National Park Service]] |last=E. Kaplan |first=Marilyn |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160113194900/http://www.nps.gov/tps/how-to-preserve/tech-notes/Tech-Notes-Mechanical01.pdf |archive-date = January 13, 2016 |df=mdy-all}}</ref> the [[Ellicott Square Building]], once one of the largest of its kind in the world;<ref>{{cite book |last1=Korom |first1=Joseph J. |title=The American Skyscraper, 1850-1940: A Celebration of Height |date=2008 |publisher=Branden Books |isbn=978-0-8283-2188-4 |page=213 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JVzYO1TyZ6AC&pg=PA213 |access-date=26 May 2021 |language=en |archive-date=June 22, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210622041737/https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_American_Skyscraper_1850_1940/JVzYO1TyZ6AC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=ellicott+square+building+largest&pg=PA213&printsec=frontcover |url-status=live}}</ref> the [[Art Deco]] [[Buffalo City Hall]] and the [[McKinley Monument]], and the [[Electric Tower]]. Beyond downtown, the [[Buffalo Central Terminal]] was built in the [[Broadway-Fillmore]] neighborhood in 1929; the [[Richardson Olmsted Complex]], built in 1881, was an [[Lunatic asylum|insane asylum]]<ref>{{cite book |last1=Ochsner |first1=Jeffrey Karl |title=H. H. Richardson: Complete Architectural Works |publisher=[[MIT Press]] |pages=78–79 |language=en |date=1982 |isbn=9780262650151 |oclc=8389021}}</ref> until its closure in the 1970s.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Buckley |first1=Eileen |title=Recalling treatment at Buffalo's former mental institution |url=https://news.wbfo.org/post/recalling-treatment-buffalo-s-former-mental-institution |website=[[WBFO]] |access-date=22 May 2021 |language=en |date=June 5, 2018 |archive-date=May 22, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210522223742/https://news.wbfo.org/post/recalling-treatment-buffalo-s-former-mental-institution |url-status=live}}</ref> [[Urban renewal]] from the 1950s to the 1970s spawned the [[Brutalist architecture|Brutalist]]-style [[Buffalo City Court Building]] and [[Seneca One Tower]], the city's tallest building.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Preparing for 38 floors of emptiness at One Seneca Tower |url=http://www.buffalonews.com/city-region/downtown-waterfront/preparing-for-38-floors-of-emptiness-at-one-seneca-tower-20131117 |url-access=limited |access-date = September 26, 2015 |date=November 17, 2013 |website=[[The Buffalo News]] |first=Melinda |last=Miller |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20150926101223/http://www.buffalonews.com/city-region/downtown-waterfront/preparing-for-38-floors-of-emptiness-at-one-seneca-tower-20131117 |archive-date = September 26, 2015 |df=mdy-all}}</ref> In the city's [[Parkside East Historic District|Parkside]] neighborhood, the [[Darwin D. Martin House]] was designed by [[Frank Lloyd Wright]] in his [[Prairie School]] style.<ref>{{cite web |title=Darwin Martin House State Historic Site |url=https://parks.ny.gov/historic-sites/darwinmartinhouse/details.aspx |website=[[New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation]] |publisher=[[State of New York]] |access-date=24 May 2021 |archive-date=January 16, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210116092839/https://parks.ny.gov/historic-sites/darwinmartinhouse/details.aspx |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

==Demographics== |

|||

Since 2016, Washington DC real estate developer [[Douglas Jemal]] has been acquiring, and redeveloping, iconic properties throughout the city.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://buffalonews.com/business/local/douglas-jemal-moves-full-speed-ahead-on-bevy-of-buffalo-projects/article_cab12e4c-ce20-11eb-a68d-afcda413165a.html |title=Douglas Jemal moves 'full speed ahead' on bevy of Buffalo projects |date=October 25, 2021}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:M&T_Bank_Center_&_Liberity_Building_-_Buffalo_NY.jpg|thumb|M&T Plaza & The Liberty Building - Buffalo, New York]] |

|||

{{wide image|Buffalo Skyline.jpg|alt=Panorama of downtown Buffalo, NY from Lake Erie|700px|Skyline of Buffalo, looking east from Lake Erie|align-cap=center}} |

|||

===City proper=== |

|||

As of the [[census]]{{GR|2}} of 2000, the city had a total population of 292,648. |

|||

===Neighborhoods=== |

|||

At that time there were 292,648 people, 122,720 [[households]], and 67,005 [[family|families]] residing in the city. The [[population density]] is 2,782.4/km² (7,205.8/mi²). There are 145,574 [[housing]] units at an average density of 1,384.1/km² (3,584.4/mi²). The [[Race (U.S. Census)|racial]] makeup of the city is 54.43% [[White (U.S. Census)|White]], 37.23% [[African American]], 0.77% [[Native American (U.S. Census)|Native American]], 1.40% [[Asian (U.S. Census)|Asian]], 0.04% [[Pacific Islander (U.S. Census)|Pacific Islander]], 3.68% from other races, and 2.45% from two or more races. 7.54% of the population are [[Hispanic American|Hispanic]] or [[Latino]] of any race. |

|||

{{Main|List of neighborhoods in Buffalo, New York}} |

|||

[[File:AllentownBuffalo1.jpg|thumb|[[Allentown, Buffalo|Allentown]]]] |

|||