Liberty ship: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tag: Reverted |

Palamabron (talk | contribs) |

||

| (219 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|US cargo ship class of WWII}} |

|||

{{about|the U.S. WWII Liberty class naval cargo ship|ships named "Liberty"|Liberty (ship)|the Liberty ship's successor|Victory ship}} |

|||

{{ |

{{about|the class of US cargo ship|ships named "Liberty"|Liberty (ship)}} |

||

{{Use American English|date=October 2013}} |

{{Use American English|date=October 2013}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2019}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2019}} |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

|Class after= |

|Class after= |

||

|Subclasses= |

|Subclasses= |

||

|Cost= [[United States dollar|US$]]2 million (${{formatnum:{{Inflation|US|2|1940|r=0}}}} million in {{CURRENTYEAR}})<ref name= "Wise-Baron p. 140">{{harvnb|Wise|Baron|2004| p=140}}</ref> |

|Cost= [[United States dollar|US$]]2 million (${{formatnum:{{Inflation|US|2|1940|r=0}}}} million in {{CURRENTYEAR}}) per ship<ref name= "Wise-Baron p. 140">{{harvnb|Wise|Baron|2004| p=140}}</ref> |

||

|Built range= |

|Built range= |

||

|In service range= |

|In service range= |

||

|In commission range= |

|In commission range= |

||

|Total ships building= |

|Total ships building= |

||

|Total ships planned=2,751 |

|Total ships planned=2,751 |

||

|Total ships completed=2,710 |

|Total ships completed=2,710 |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

{{Infobox ship characteristics |

{{Infobox ship characteristics |

||

|Hide header= |

|Hide header= |

||

|Header caption= |

|Header caption= |

||

|Ship class=[[Cargo ship]] |

|Ship class=[[Cargo ship]] |

||

|Ship type= |

|Ship type= |

||

|Ship tonnage={{GRT|7176}}, {{DWT|10865}}{{sfn|Sawyer|Mitchell|1985|p=39}} |

|||

|Ship tonnage= |

|||

|Ship displacement={{convert|14245|LT|MT}} |

|Ship displacement={{convert|14245|LT|MT}}{{sfn|Sawyer|Mitchell|1985|p=39}} |

||

|Ship tons burthen= |

|||

|Ship length={{Convert|441|ft|6|in|abbr=on}} |

|Ship length={{Convert|441|ft|6|in|abbr=on}} |

||

|Ship beam={{Convert|56|ft|10.75|in|1|abbr=on}} |

|Ship beam={{Convert|56|ft|10.75|in|1|abbr=on}} |

||

|Ship height= |

|Ship height= |

||

|Ship draft={{Convert|27|ft|9.25|in|1|abbr=on}} |

|Ship draft={{Convert|27|ft|9.25|in|1|abbr=on}} |

||

|Ship depth= |

|Ship depth= |

||

|Ship hold depth= |

|Ship hold depth= |

||

| Line 49: | Line 48: | ||

|Ship power= |

|Ship power= |

||

|Ship propulsion=*Two oil-fired boilers |

|Ship propulsion=*Two oil-fired boilers |

||

*triple-expansion steam engine |

* triple-expansion steam engine |

||

*single screw, {{Convert|2500|hp|abbr=on}} |

* single screw, {{Convert|2500|hp|abbr=on}} |

||

|Ship sail plan= |

|||

|Ship speed= {{Convert|11|-|11.5|kn|lk=in}} |

|Ship speed= {{Convert|11|-|11.5|kn|lk=in}} |

||

|Ship range={{Convert|20000|nmi|abbr=on}} |

|Ship range={{Convert|20000|nmi|abbr=on}} |

||

|Ship endurance= |

|Ship endurance= |

||

|Ship boats= |

|Ship boats= |

||

|Ship capacity= |

|||

|Ship capacity={{Convert|10856|MT|LT|0|abbr=on}} [[deadweight tonnage|deadweight]] (DWT)<ref name="davies"/> |

|||

|Ship troops= |

|Ship troops= |

||

|Ship complement=*38–62 [[United States Merchant Marine|USMM]] |

|Ship complement=*38–62 [[United States Merchant Marine|USMM]] |

||

*21–40 [[United States Navy Armed Guard|USNAG]] |

* 21–40 [[United States Navy Armed Guard|USNAG]]{{citation needed|date=September 2023}} |

||

|Ship crew= |

|Ship crew= |

||

|Ship time to activate= |

|Ship time to activate= |

||

| Line 71: | Line 69: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

|} |

|} |

||

'''Liberty ships''' were a [[ship class|class]] of [[cargo ship]] built in the United States during [[World War II]] under the [[Emergency Shipbuilding Program]]. Although British in concept,<ref name=Wardlow>{{cite book |last1=Wardlow |first1=Chester |year=1999 |title=The Technical Services – The Transportation Corps: Responsibilities, Organization, and Operations |series=United States Army in World War II |location=Washington, D.C. |publisher=[[United States Army Center of Military History|Center of Military History, United States Army]] |lccn=99490905 |page=156}}</ref> the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost construction. Mass-produced on an unprecedented scale, the Liberty ship came to symbolize U.S. wartime industrial output.<ref name=Flip60>{{cite book |last= Flippen |first= J. B. |date= April 2018 |title= Speaker Jim Wright |url= https://utpress.utexas.edu/books/flippen-speaker-jim-wright |location= Austin, Texas |publisher= [[University of Texas Press]] |page= 60 |isbn= 9781477315149 |quote= mass-produced during the war, the Liberty Ship had become a symbol of the miracle of American production |access-date= 29 November 2021 |archive-date= 17 June 2022 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20220617010700/https://utpress.utexas.edu/books/flippen-speaker-jim-wright |url-status= dead }}</ref> |

|||

'''Liberty ships''' were a [[ship class|class]] of [[cargo ship]] built in the [[United States]] during [[World War II]]. Though British in concept, the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost construction.<ref>{{cite video |

|||

| year =1942 |

|||

| title =Video: America Reports On Aid To Allies Etc. (1942) |

|||

| url =https://archive.org/details/gov.archives.arc.38937 |

|||

| publisher =[[Universal Newsreel]] |

|||

| accessdate =21 February 2012 |

|||

}}</ref> Mass-produced on an unprecedented scale, the Liberty ship came to symbolize U.S. wartime industrial output. |

|||

The class was developed to meet British orders for transports to replace ships that had been lost. Eighteen American [[shipyard]]s built 2,710 Liberty ships between 1941 and 1945 (an average of three ships every two days), easily the largest number of ships ever produced to a single design. |

The class was developed to meet British orders for transports to replace ships that had been lost. Eighteen American [[shipyard]]s built 2,710 Liberty ships between 1941 and 1945 (an average of three ships every two days),<ref name=usmmburn>{{cite web |url= http://www.usmm.org/libertyships.html |title= Liberty Ships built by the United States Maritime Commission in World War II |website= usmm.org |publisher= American Merchant Marine at War |access-date= 2021-11-28 |quote= (2,710 ships were completed, as one burned at the dock.) |archive-date= 9 May 2008 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20080509091805/http://www.usmm.org/libertyships.html |url-status= dead }}</ref> easily the largest number of ships ever produced to a single design. |

||

Their production mirrored (albeit on a much larger scale) the manufacture of "[[Hog Islander]]" and similar standardized ship types during World War I. The immensity of the effort, the number of ships built, the role of [[Rosie the Riveter|female workers]] in their construction, and the survival of some far longer than their original five-year design life combine to make them the subject of much continued interest. |

Their production mirrored (albeit on a much larger scale) the manufacture of "[[Hog Islander]]" and similar standardized ship types during World War I. The immensity of the effort, the number of ships built, the role of [[Rosie the Riveter|female workers]] in their construction, and the survival of some far longer than their original five-year design life combine to make them the subject of much continued interest. |

||

==History |

==History== |

||

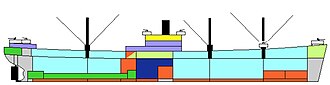

[[File:Libertyship linedrawing en.jpg|right|thumb|upright=1.4|Profile plan of a Liberty ship]] |

|||

===Design=== |

===Design=== |

||

[[File:Libertyship linedrawing en.jpg|right|thumb|upright=1.5|Profile plan of a Liberty ship]] |

|||

In 1936, the American [[Merchant Marine Act of 1936|Merchant Marine Act]] was passed to subsidize the annual construction of 50 commercial merchant vessels which could be used in wartime by the [[United States Navy]] as naval auxiliaries, crewed by [[United States Merchant Marine|U.S. Merchant Mariners]]. The number was doubled in 1939 and again in 1940 to 200 ships a year. Ship types included two tankers and three types of merchant vessel, all to be powered by [[steam turbine]]s. Limited industrial capacity, especially for reduction gears, meant that relatively few of these ships were built. |

|||

[[File:Planlibertyship.jpg|thumb|upright=1.5|alt=A colored diagram of compartments on a ship|A colored diagram of compartments on a Liberty ship, from the right side, front to the right |

|||

{{Div col|colwidth=10em}} |

|||

{{legend|#44ce35|Machinery spaces}} |

|||

{{legend|#fcfd1d|Command and control}} |

|||

{{legend|#f8632e|Liquid stores}} |

|||

{{legend|#a2fffe|Dry cargo}} |

|||

{{legend|#163098|Engine room}} |

|||

{{legend|#cbcbcb|Misc}} |

|||

{{legend|#cbfc82|Dry stores}} |

|||

{{legend|#9991fe|Habitation}} |

|||

{{Div col end}}]] |

|||

In 1936, the American [[Merchant Marine Act of 1936|Merchant Marine Act]] was passed to subsidize the annual construction of 50 commercial merchant vessels which could be used in wartime by the [[United States Navy]] as naval auxiliaries, crewed by [[United States Merchant Marine|U.S. Merchant Mariners]]. The number was doubled in 1939 and again in 1940 to 200 ships a year. Ship types included two tankers and three types of merchant vessel, all to be powered by [[steam turbine]]s. Limited industrial capacity, especially for reduction gears, meant that relatively few of these designs of ships were built. |

|||

However, in 1940, the British government ordered 60 [[Ocean ship|Ocean-class]] [[cargo ship|freighter]]s from American yards to replace war losses and boost the merchant fleet. These were simple but fairly large (for the time) with a single {{convert|2500|hp|kW}} [[compound steam engine]] of outdated but reliable design. Britain specified coal-fired plants, because it then had extensive coal mines and no significant domestic oil production.{{refn |During WW II, Nazi Germany made the exact same decision, when they decided to mass-produce coal-powered, steam-engine driven [[Kriegslokomotive]]s.<ref>[[National Geographic]], 2017. ''"Nazi Megastructures: Hitler's War Trains"''</ref> Despite electrical industrial technology having begun to replace stationary steam engines in the late 19th century, and [[Internal combustion engine]]s in two-railcar, high speed [[Diesel-electric transmission|Diesel-electric]] [[Diesel locomotive|locomotive]] and train sets, developed by [[Maybach]], were series produced in Germany since 1935, the war also made Germany short on oil, but still rich in coal, especially in the [[Ruhr|Ruhr region]], and thus mass-produced old-fashioned but very effective steam locomotives for transporting goods and people across the large conquered European area.}} |

|||

The predecessor designs, which included the "Northeast Coast, Open Shelter Deck Steamer", were based on a simple ship originally produced in [[Sunderland, Tyne and Wear|Sunderland]] by [[J.L. Thompson and Sons|J.L. Thompson & Sons]] based on a 1939 design for a simple [[tramp steamer]], which was cheap to build and cheap to run (see [[Silver Line (shipping company)|Silver Line]]). Examples include SS ''Dorington Court'' built in 1939.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.benjidog.co.uk/Court/Dorington%20Court%20%281939%29.html |title=Dorington Court (1939) |access-date=28 June 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150701004421/http://www.benjidog.co.uk/Court/Dorington%20Court%20%281939%29.html |archive-date=1 July 2015 |url-status=dead }}</ref> The order specified an {{convert|18|inch|m|adj=on}} increase in [[Draft (hull)|draft]] to boost displacement by {{convert|800|LT|MT}} to {{convert|10100|LT|MT}}. The accommodation, [[Bridge (nautical)|bridge]], and main engine were located amidships, with a tunnel connecting the main engine shaft to the propeller via a long aft extension. The first Ocean-class ship, SS ''Ocean Vanguard'', was [[Ceremonial ship launching|launched]] on 16 August 1941. |

|||

[[File:Liberty ship 140-ton VTE engine.jpg|thumb|upright|140-ton [[compound steam engine#Multiple-expansion engines|vertical triple expansion steam engine]] of the type used to power [[World War II]] Liberty ships, assembled for testing before delivery]] |

|||

The design was modified by the [[United States Maritime Commission]], in part to increase conformity to American construction practices, but more importantly to make it even quicker and cheaper to build. The US version was designated 'EC2-S-C1': 'EC' for Emergency Cargo, '2' for a ship between {{convert|400|and|450|ft|m}} long (Load Waterline Length), 'S' for steam engines, and 'C1' for design C1. The new design replaced much [[riveting]], which accounted for one-third of the labor costs, with [[welding]], and had oil-fired boilers. It was adopted as a Merchant Marine Act design, and production awarded to a conglomerate of West Coast engineering and construction companies headed by [[Henry J. Kaiser]] known as the [[Six Companies]]. Liberty ships were designed to carry {{convert|10000|LT|MT|sigfig=3}} of cargo, usually one type per ship, but, during wartime, generally carried loads far exceeding this.<ref>[http://www.usmm.org/capacity.html]- cite: American Merchant Marine at War; retrieved 20 July 2012</ref> |

|||

The design was modified by the [[United States Maritime Commission]], in part to increase conformity to American construction practices, but more importantly to make it even quicker and cheaper to build. The US version was designated 'EC2-S-C1': 'EC' for Emergency Cargo, '2' for a ship between {{convert|400|and|450|ft|m}} long (Load Waterline Length), 'S' for steam engines, and 'C1' for design C1. The new design replaced much [[riveting]], which accounted for one-third of the labor costs, with [[welding]], and had oil-fired boilers. It was adopted as a Merchant Marine Act design, and production awarded to a conglomerate of West Coast engineering and construction companies headed by [[Henry J. Kaiser]] known as the [[Six Companies]]. Liberty ships were designed to carry {{convert|10000|LT|MT|sigfig=3}} of cargo, usually one type per ship, but, during wartime, generally carried loads far exceeding this.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usmm.org/capacity.html|title=Capacity of One Liberty Ship|website=Usmm.org|access-date=11 March 2022}}</ref> |

|||

On 27 March 1941, the number of [[lend-lease]] ships was increased to 200 by the Defense Aid Supplemental Appropriations Act and increased again in April to 306, of which 117 would be Liberty ships. |

On 27 March 1941, the number of [[lend-lease]] ships was increased to 200 by the Defense Aid Supplemental Appropriations Act and increased again in April to 306, of which 117 would be Liberty ships. |

||

===Variants=== |

===Variants=== |

||

The basic EC2-S-C1 cargo design was modified during construction into three major variants with the same basic dimensions and slight variance in tonnage. One variant, with basically the same features but different type numbers, had four rather than five [[Hold (partition)|holds]] served by large hatches and [[kingpost]] with large capacity booms. Those four hold ships were designated for transport of tanks and boxed aircraft.<ref name=FRtab>{{cite |

The basic EC2-S-C1 cargo design was modified during construction into three major variants with the same basic dimensions and slight variance in tonnage. One variant, with basically the same features but different type numbers, had four rather than five [[Hold (partition)|holds]] served by large hatches and [[kingpost]] with large capacity booms. Those four hold ships were designated for transport of tanks and boxed aircraft.<ref name=FRtab>{{cite book |title=Federal Register |volume=11 |issue=161 |pages=8974 |publisher=U.S. Government |date=17 August 1946|url=https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1946-08-17/pdf/FR-1946-08-17.pdf |access-date=20 June 2019}}</ref> |

||

In the detailed Federal Register publication of the post war prices of Maritime Commission types the Liberty variants are noted as:<ref name=FRtab/> |

In the detailed Federal Register publication of the post war prices of Maritime Commission types the Liberty variants are noted as:<ref name=FRtab/> |

||

; EC2-S-AW1 |

|||

* EC2-S-AW1: Collier (All given names of notable coal seams as ''Banner Seam'', ''Beckley Seam'' and ''Bon Air Seam'') |

|||

: Collier (All given names of coal seams as ''[[SS Banner Seam]]'', ''[[Beckley Seam]]'' and ''[[Bon Air Seam]]'') |

|||

* Z-EC2-S-C2: Tank carrier (four holds, kingposts) — example {{SS|Frederic C. Howe}} |

|||

;Z-EC2-S-C2 |

|||

* Z-ET1-S-C3: Tanker — example [[SS Carl R. Gray|SS ''Carl R. Gray'']] with some becoming the Navy's {{sclass-|Armadillo|tanker|1}} |

|||

: Tank carrier (four holds, kingposts) – example {{SS|Frederic C. Howe}}{{efn|The Z-EC2-S-C2 Tank carrier type details had not been previously published until 17 August 1946 Federal Register.<ref name=FRtab/>}} |

|||

;Z-ET1-S-C3 |

|||

: [[T1 tanker]] – example [[SS Carl R. Gray|SS ''Carl R. Gray'']]. Eighteen were commissioned into USN in 1943 as the {{sclass|Armadillo|tanker|1}} |

|||

;Z-EC2-S-C5 |

|||

: Boxed aircraft transport (four holds, kingposts) – example {{SS|Charles A. Draper}}.{{efn|photo showing holds, kingposts}} Post war 16 of these Liberty ships were converted 1954–1958 into {{sclass|Guardian|radar picket ship|1}} |

|||

In preparation for the [[Normandy landings]] and afterward to support the rapid expansion of logistical transport ashore a modification was made to make standard Liberty vessels more suitable for mass transport of vehicles and in records are seen as "MT" for Motor Transport vessels. As MTs four holds were loaded with vehicles while the fifth was modified to house the drivers and assistants.<ref>{{cite book |last=Larson |first=Harold |title=The Army's Cargo Fleet In World War II |year=1945 |publisher=Office of the Chief of Transportation, Army Service Forces, U. S. Army |location=Washington, D.C. |pages=75–77 |url=https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a438107.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200803052404/https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a438107.pdf |url-status=live |archive-date=3 August 2020 |access-date=20 June 2019}}</ref> |

|||

The Z-EC2-S-C2 Tank carrier type details had not been previously published until 17 August 1946 Federal Register.<ref name=FRtab/> |

|||

The modifications into troop transports also were not given special type designations. |

|||

In preparation for the [[Normandy landings]] and afterward to support the rapid expansion of logistical transport ashore a modification was made to make standard Liberty vessels more suitable for mass transport of vehicles and in records are seen as "MT" for Motor Transport vessels. In that case four holds were loaded with vehicles while the fifth was modified to house the drivers and assistants.<ref>{{cite book |last=Larson |first=Harold |title=The Army's Cargo Fleet In World War II |year=1945 |publisher=Office of the Chief of Transportation, Army Service Forces, U. S. Army |location=Washington, D. C. |pages=75–77 |url=https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a438107.pdf |accessdate=20 June 2019}}</ref> |

|||

The modifications into troop transports also were not given special type designations. The troop transports are discussed below. |

|||

===Propulsion=== |

===Propulsion=== |

||

[[File:Liberty Ship Model (engine room detail).jpg|thumb|Engine room (model cutaway)]] |

[[File:Liberty Ship Model (engine room detail).jpg|thumb|Engine room (model cutaway)]] |

||

By 1941, the [[steam turbine]] was the preferred [[marine steam engine]] because of its greater efficiency compared to earlier reciprocating [[compound steam engine]]s. Steam turbine engines required very precise manufacturing techniques and balancing and a complicated [[reduction gear]], however, and the companies capable of manufacturing them already were committed to the large construction program for [[warship]]s. Therefore, a 140-ton<ref>''Live'' (the program of [[Project Liberty Ship]] provided for cruises of the Liberty ship {{SS|John W. Brown}}, 2013 edition, claims both that the engine weighed 135 tons (p. 10) fully assembled and that it weighed 140 tons (p. 11).</ref> [[vertical triple expansion]] steam engine of obsolete design was selected to power Liberty ships because it was cheaper and easier to build in the numbers required for the Liberty ship program and because more companies could manufacture it. Eighteen different companies eventually built the engine. It had the additional advantage of ruggedness and simplicity. Parts manufactured by one company were interchangeable with those made by another, and the openness of its design made most of its moving parts easy to see, access, and oil. The engine — {{convert|21|feet|m}} long and {{convert|19|feet|m}} tall — was designed to operate at 76 [[Revolutions per minute|rpm]] and propel a Liberty ship at about {{convert|11|knots}}.<ref>''Live'' (program of [[Project Liberty Ship]] provided for cruises of the Liberty ship {{SS|John W. Brown}}, 2013 edition, p. 10.</ref> |

|||

By 1941, the [[steam turbine]] was the preferred [[marine steam engine]] because of its greater efficiency compared to earlier reciprocating [[compound steam engine]]s. Steam turbine engines however, required very precise manufacturing techniques to machine their complicated [[Gear#Double helical|double helical reduction gears]], and the companies capable of producing them were already committed to the large construction program for [[warship]]s. Therefore, a {{convert|140|ST|adj=on}}<ref>''Live'' (the program of [[Project Liberty Ship]] provided for cruises of the Liberty ship {{SS|John W. Brown}}, 2013 edition, claims both that the engine weighed 135 tons (p. 10) fully assembled and that it weighed 140 tons (p. 11).</ref> [[vertical triple expansion]] steam engine, of obsolete design, was selected to power Liberty ships because it was cheaper and easier to build in the numbers required for the Liberty ship program, and because more companies could manufacture it. Eighteen different companies eventually built the engine. It had the additional advantage of ruggedness, simplicity and familiarity to seamen. Parts manufactured by one company were interchangeable with those made by another, and the openness of its design made most of its moving parts easy to see, access, and oil. The engine—{{convert|21|feet|m}} long and {{convert|19|feet|m}} tall—was designed to operate at 76 [[revolutions per minute|rpm]] and propel a Liberty ship at about {{convert|11|knots}}.<ref>''Live'' (program of [[Project Liberty Ship]] provided for cruises of the Liberty ship {{SS|John W. Brown}}, 2013 edition, p. 10.</ref> |

|||

===Construction=== |

===Construction=== |

||

The ships were constructed of sections that were welded together. This is similar to the technique used by [[Palmers Shipbuilding and Iron Company Limited|Palmer's]] at [[Jarrow]], northeast England, but substituted [[welding]] for [[ |

The ships were constructed of sections that were welded together. This is similar to the technique used by [[Palmers Shipbuilding and Iron Company Limited|Palmer's]] at [[Jarrow]], northeast England, but substituted [[welding]] for [[rivet]]ing. Riveted ships took several months to construct. The work force was newly trained as the yards responsible had not previously built welded ships. As America entered the war, the shipbuilding yards employed women, to replace men who were enlisting in the armed forces.{{sfn|Herman|2012|pp=135–136, 178–180}} |

||

<gallery mode="packed" heights="200" caption="The construction of a Liberty ship at the Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyards, Baltimore, Maryland, in March/April 1943"> |

<gallery mode="packed" heights="200" caption="The construction of a Liberty ship at the Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyards, Baltimore, Maryland, in March/April 1943"> |

||

File:Liberty ship construction 03 keel plates.jpg|Day 2 : Laying of the keel plates |

File:Liberty ship construction 03 keel plates.jpg|Day 2 : Laying of the keel plates |

||

File:Liberty ship construction 07 bulkheads.jpg|Day 6 : Bulkheads and girders below the second deck are in place |

File:Liberty ship construction 07 bulkheads.jpg|Day 6 : Bulkheads and girders below the second deck are in place. |

||

File:Liberty ship construction 09 lower decks.jpg|Day 10 : Lower deck being completed and the upper deck amidship erected |

File:Liberty ship construction 09 lower decks.jpg|Day 10 : Lower deck being completed and the upper deck amidship erected |

||

File:Liberty ship construction 10 upper decks.jpg|Day 14 : Upper deck erected and mast houses and the after-deck house in place |

File:Liberty ship construction 10 upper decks.jpg|Day 14 : Upper deck erected and mast houses and the after-deck house in place |

||

File:Liberty ship construction 11 prepared for launch.jpg|Day 24 : Ship ready for launching |

File:Liberty ship construction 11 prepared for launch.jpg|Day 24 : Ship ready for launching |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

[[File:SS Patrick Henry launching on Liberty Fleet Day, 27 September 1941 (26580977380).jpg|thumb|right|Launch of [[SS Patrick Henry|SS ''Patrick Henry'']], the first Liberty ship, on 27 September 1941]] |

|||

The ships initially had a poor public image owing to their appearance. In a speech announcing the emergency shipbuilding program President [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]] had referred to the ship as "a dreadful looking object", and [[Time (magazine)|''Time'']] called it an "Ugly Duckling". 27 September 1941 was dubbed [[Liberty Fleet Day (Victory Fleet Day)|Liberty Fleet Day]] to try to assuage public opinion, since the first 14 "Emergency" vessels were launched that day. The first of these was {{SS|Patrick Henry}}, launched by President Roosevelt. In remarks at the launch ceremony FDR cited [[Patrick Henry]]'s 1775 speech that finished "[[Give me liberty or give me death]]". Roosevelt said that this new class of ship would bring liberty to Europe, which gave rise to the name Liberty ship. |

|||

The first ships required about 230 days to build (''Patrick Henry'' took 244 days), but the median production time per ship dropped to 39 days by 1943.{{sfn|Davies|2004}} The record was set by {{SS|Robert E. Peary}}, which was launched 4 days and 15{{frac|1|2}} hours after the [[keel]] had been laid, although this [[publicity stunt]] was not repeated: in fact much fitting-out and other work remained to be done after the ''Peary'' was launched. The ships were made assembly-line style, from prefabricated sections. In 1943 three Liberty ships were completed daily. They were usually named after famous Americans, starting with the signatories of the [[United States Declaration of Independence|Declaration of Independence]]. 17 of the Liberty ships were named in honor of outstanding African-Americans. The first, in honor of [[Booker T. Washington]], was christened by [[Marian Anderson]] in 1942, and the {{SS|Harriet Tubman}}, recognizing the only woman on the list, was christened on 3 June 1944.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usmm.org/african-americans.html|title=African-Americans in the U.S. Merchant Marine and U.S. Maritime Service during World War II|website=Usmm.org|access-date=10 March 2022}}</ref> |

|||

The ships initially had a poor public image due to their appearance. In a speech announcing the emergency shipbuilding program President [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]] had referred to the ship as "a dreadful looking object", and [[Time magazine|''Time'' magazine]] called it an "Ugly Duckling". 27 September 1941, was dubbed [[Liberty Fleet Day (Victory Fleet Day)|Liberty Fleet Day]] to try to assuage public opinion, as the first 14 "Emergency" vessels were launched that day. The first of these was {{SS|Patrick Henry}}, launched by President Roosevelt. In remarks at the launch ceremony, FDR cited [[Patrick Henry]]'s 1775 speech that finished "[[Give me liberty or give me death]]". Roosevelt said that this new class of ships would bring liberty to Europe, which gave rise to the name Liberty ship. |

|||

Any group that raised [[war bond]]s worth $2 million could propose a name. Most bore the names of deceased people. The only living namesake was Francis J. O'Gara, the [[purser]] of {{SS|Jean Nicolet}}, who was thought to have been killed in [[Japanese submarine I-8#SS Jean Nicolet|a submarine attack]], but in fact survived the war in a Japanese [[prisoner of war]] camp. Not named after people were: {{SS|Stage Door Canteen}}, named after the [[United Service Organizations|USO]] club in New York; and {{SS|U.S.O.}}, named after the [[United Service Organizations]] (USO).<ref>[http://www.cr.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/116liberty_victory_ships/116facts1.htm Reading 1: Liberty Ships] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050308175723/http://www.cr.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/116liberty_victory_ships/116facts1.htm |date=8 March 2005 }} ''[[National Park Service]] Cultural Resources.''</ref> |

|||

[[File:SS John W. Brown aerial photo.jpg|thumb|left|Aerial photograph of the Liberty ship {{SS|John W. Brown}} outbound from the [[United States]] carrying a large deck cargo after her conversion to a "Limited Capacity [[Troopship]]." It probably was taken in the summer of 1943 during her second voyage.]] |

|||

[[File:Riveting the SS JOHN W BROWN.webm|thumb|left|Riveters from H. Hansen Industries work on the Liberty ship ''John W. Brown'' at Colonna's Shipyard, a ship repair facility located in the Port of [[Norfolk, Virginia]]. (December 2014)]] |

|||

The first ships required about 230 days to build (''Patrick Henry'' took 244 days), but the average eventually dropped to 42 days. The record was set by {{SS|Robert E. Peary}}, which was launched 4 days and 15{{frac|1|2}} hours after the [[keel]] was laid, although this [[publicity stunt]] was not repeated: in fact much fitting-out and other work remained to be done after the ''Peary'' was launched. The ships were made assembly-line style, from prefabricated sections. In 1943, three Liberty ships were completed daily. They were usually named after famous Americans, starting with the signatories of the [[United States Declaration of Independence|Declaration of Independence]]. In the 1940s, 17 of the Liberty Ships were named in honor of outstanding African-Americans. The first, in honor of [[Booker T. Washington]], was christened by [[Marian Anderson]] in 1942, and the {{SS|Harriet Tubman}}, recognizing the only woman on the list, was christened on 3 June 1944.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usmm.org/african-americans.html|title=African-Americans in the U.S. Merchant Marine and U.S. Maritime Service|last=|first=|date=|website=|publisher=|access-date=}}</ref> |

|||

Any group which raised [[war bond]]s worth $2 million could propose a name. Most bore the names of deceased people. The only living namesake was Francis J. O'Gara, the [[purser]] of {{SS|Jean Nicolet}}, who was thought to have been killed in a submarine attack, but, in fact, survived the war in a Japanese [[prisoner of war]] camp. Other exceptions to the naming rule were {{SS|Stage Door Canteen}}, named for the [[United Service Organizations|USO]] club in New York, and {{SS|U.S.O.}}, named after the organization itself.<ref>[http://www.cr.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/116liberty_victory_ships/116facts1.htm Reading 1: Liberty Ships] ''[[National Park Service]] Cultural Resources.''</ref> |

|||

Another notable Liberty ship was {{SS|Stephen Hopkins}}, which sank the German [[commerce raider]] {{Ship|German auxiliary cruiser|Stier||2}} in a ship-to-ship gun battle in 1942 and became the first American ship to sink a German surface combatant. |

Another notable Liberty ship was {{SS|Stephen Hopkins}}, which sank the German [[commerce raider]] {{Ship|German auxiliary cruiser|Stier||2}} in a ship-to-ship gun battle in 1942 and became the first American ship to sink a German surface combatant. |

||

[[File:Liberty Ship scaler HD-SN-99-02466.JPG|thumb|right|Eastine Cowner, a former waitress, at work on the Liberty ship {{SS|George Washington Carver}} at the Kaiser shipyards, Richmond, California, in 1943. One of a series taken by E. |

[[File:Liberty Ship scaler HD-SN-99-02466.JPG|thumb|right|Eastine Cowner, a former waitress, at work on the Liberty ship {{SS|George Washington Carver}} at the Kaiser shipyards, Richmond, California, in 1943. One of a series taken by E. F. Joseph on behalf of the [[Office of War Information]], documenting the work of [[African-American]]s in the war effort]] |

||

The wreck of {{SS|Richard Montgomery}} lies off the coast of [[Kent]] with {{convert|1,400|t|ST|order=flip|abbr=off|lk=on}} of [[explosive]]s still on board, enough to match a very small yield [[nuclear weapon]] should they ever go off.<ref> |

The wreck of {{SS|Richard Montgomery}} lies off the coast of [[Kent]] with {{convert|1,400|t|ST|order=flip|abbr=off|lk=on}} of [[explosive]]s still on board, enough to match a very small yield [[nuclear weapon]] should they ever go off.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dft.gov.uk/mca/2000_survey_report_montgomery.pdf|archive-url=http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20121107103953/http://www.dft.gov.uk/mca/2000_survey_report_montgomery.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-date=2012-11-07|title=Report on the Wreck of the SS Richard Montgomery|website=Webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk|access-date=2022-03-11}}</ref><ref name="Nuclear yield">{{cite web|title=Little Boy and Fat Man|url=https://www.atomicheritage.org/history/little-boy-and-fat-man|website=[[Atomic Heritage Foundation]]|access-date=24 December 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171224040030/https://www.atomicheritage.org/history/little-boy-and-fat-man|archive-date=24 December 2017|date=23 July 2014|quote=Little Boy yield: 15 kilotons / Fat Man yield: 21 kilotons}}</ref> {{SS|E. A. Bryan}} detonated with the energy of {{convert|2000|tonTNT|lk=on}} in July 1944 as it was being loaded, killing 320 sailors and civilians in what was called the [[Port Chicago disaster]]. Another Liberty ship that exploded was the rechristened {{SS|Grandcamp}}, which caused the [[Texas City Disaster]] on 16 April 1947, killing at least 581 people. |

||

Six Liberty ships were converted at [[Point Clear, Alabama]], by the [[United States Army Air Force]], into floating aircraft repair depots, operated by the [[Army Transport Service]], starting in April 1944. The secret project, dubbed "Project Ivory Soap", provided mobile depot support for [[B-29 Superfortress]] bombers and [[P-51 Mustang]] fighters based on [[Guam]], [[Iwo Jima]], and [[Okinawa]] beginning in December 1944. The six ARU(F)s (Aircraft Repair Unit, Floating), however, were also fitted with landing platforms to accommodate four [[Sikorsky R-4]] helicopters, where they provided medical evacuation of combat casualties in both the [[Philippine Islands]] and Okinawa.<ref> |

Six Liberty ships were converted at [[Point Clear, Alabama]], by the [[United States Army Air Force]], into floating aircraft repair depots, operated by the [[Army Transport Service]], starting in April 1944. The secret project, dubbed "Project Ivory Soap", provided mobile depot support for [[B-29 Superfortress]] bombers and [[P-51 Mustang]] fighters based on [[Guam]], [[Iwo Jima]], and [[Okinawa Island|Okinawa]] beginning in December 1944. The six ARU(F)s (Aircraft Repair Unit, Floating), however, were also fitted with landing platforms to accommodate four [[Sikorsky R-4]] helicopters, where they provided medical evacuation of combat casualties in both the [[Philippine Islands]] and Okinawa.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://cbi-theater-3.home.comcast.net/~cbi-theater-3/hoverfly/hoverfly.html|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20081022065117/http://cbi-theater-3.home.comcast.net/~cbi-theater-3/hoverfly/hoverfly.html|url-status=dead|title=The Hoverfly in CBI, Carl Warren Weidenburner|archive-date=22 October 2008|access-date=10 March 2022}}</ref> |

||

The last new-build Liberty ship constructed was {{SS|Albert M. Boe}}, launched on 26 September 1945 and delivered on 30 October 1945. She was named after the chief engineer of a [[United States Army]] freighter who had stayed below decks to shut down his engines after a 13 April 1945 explosion, an act that won him a posthumous [[Merchant Marine Distinguished Service Medal]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/a5/albert_m_boe.htm |title=SS ''Albert M. Boe'' |work=history.navy.mil |year=2004 | |

The last new-build Liberty ship constructed was {{SS|Albert M. Boe}}, launched on 26 September 1945 and delivered on 30 October 1945. She was named after the chief engineer of a [[United States Army]] freighter who had stayed below decks to shut down his engines after a 13 April 1945 explosion, an act that won him a posthumous [[Merchant Marine Distinguished Service Medal]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/a5/albert_m_boe.htm |title=SS ''Albert M. Boe'' |work=history.navy.mil |year=2004 |access-date=7 May 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=http://webarchive.loc.gov/all/20121007221940/http%3A//www%2Ehistory%2Enavy%2Emil/danfs/a5/albert_m_boe%2Ehtm |archive-date= 7 October 2012 }}</ref> In 1950, a "new" liberty ship was constructed by Industriale Maritime SpA, [[Genoa]], Italy by using the bow section of {{SS|Bert Williams||2}} and the stern section of {{SS|Nathaniel Bacon||2}}, both of which had been wrecked. The new ship was named {{SS|Boccadasse}}, and served until scrapped in 1962.<ref name=LibB>{{cite web |url=http://www.mariners-l.co.uk/LibShipsB.html |title=Liberty Ships – B |publisher=Mariners |access-date=6 January 2012}}</ref><ref name=LibN>{{cite web |url=http://www.mariners-l.co.uk/LibShipsN.html |title=Liberty Ships – N–O |publisher=Mariners |access-date=6 January 2012}}</ref> |

||

Several designs of mass-produced petroleum |

Several designs of mass-produced petroleum tanker were also produced, the most numerous being the [[T2 tanker]] series, with about 490 built between 1942 and the end of 1945. |

||

===Problems===<!-- This section is linked from [[Problems of the Liberty ship]] redirect --> |

===Problems===<!-- This section is linked from [[Problems of the Liberty ship]] redirect --> |

||

[[File:JeremiahO'Brienbow27may07.jpg|thumb|upright|{{SS| |

[[File:JeremiahO'Brienbow27may07.jpg|thumb|upright|{{SS|Jeremiah O'Brien}}]] |

||

The ship could break easily, the ship also cracks easily stated bellow. |

|||

====Hull cracks==== |

====Hull cracks==== |

||

[[File:TankerSchenectady.jpg|right|thumb|The {{SS|Schenectady}} split apart by [[brittle fracture]] while in harbor, 1943. It was a 152-meter-long T2 tanker.]] |

|||

Early Liberty ships suffered hull and deck cracks, and a few were lost due to such structural defects. During World War II there were nearly 1,500 instances of significant [[brittle fracture]]s. Twelve ships, including three of the 2,710 Liberties built, broke in half without warning, including {{SS|John P. Gaines}},<ref>[http://www.armed-guard.com/gaines.html Wreck of the SS ''John P Gaines'']</ref><ref>[http://www.iste.co.uk/data/doc_cbornfqmtxga.pdf X-FEM for Crack Propagation – Introduction] Article which includes clear photograph of a ship broken in half.</ref> which sank on 24 November 1943 with the loss of 10 lives. Suspicion fell on the shipyards, which had often used inexperienced workers and new welding techniques to produce large numbers of ships in great haste. |

|||

Early Liberty ships suffered hull and deck cracks, and a few were lost due to such structural defects. During World War II there were nearly 1,500 instances of significant [[brittle fracture]]s. Twelve ships, including three of the 2,710 Liberty ships built, broke in half without warning, including {{SS|John P. Gaines}},<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.armed-guard.com/gaines.html|title=John P Gaines|website=Armed-guard.com|access-date=10 March 2022|archive-date=23 January 2007|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070123125404/http://www.armed-guard.com/gaines.html|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>[http://www.iste.co.uk/data/doc_cbornfqmtxga.pdf X-FEM for Crack Propagation – Introduction] Article which includes clear photograph of a ship broken in half.</ref> which sank on 24 November 1943 with the loss of 10 lives. Suspicion fell on the shipyards, which had often used inexperienced workers and new welding techniques to produce large numbers of ships in great haste. |

|||

The [[Ministry of War Transport]] borrowed the British-built {{SS|Empire Duke||2}} for testing purposes.<ref name=UMA>{{cite journal |

The [[Ministry of War Transport]] borrowed the British-built {{SS|Empire Duke||2}} for testing purposes.<ref name=UMA>{{cite journal|pmc=2604477 |title=Asbestos and Ship-Building: Fatal Consequences |first1=John |last1=Hedley-Whyte |first2=Debra R |last2=Milamed |publisher=Ulster Medical Society |journal=Ulster Medical Journal |year=2008 |volume=77 |issue=September 2008 |pages=191–200 |pmid=18956802}}</ref> [[Constance Tipper]] of [[Cambridge University]] demonstrated that the fractures did not start in the welds, but were due to the [[embrittlement]] of the steel used.<ref name=Tipper>{{Cite web|url=http://www-g.eng.cam.ac.uk/125/1925-1950/tipper.html|title=Constance Tipper|website=G.eng.cam.ac.uk|access-date=10 March 2022}}</ref> When used in riveted construction, however, the same steel did not have this problem. Tipper discovered that at a certain temperature, the steel the ships were made of changed from being [[Ductility|ductile]] to [[brittle]], allowing cracks to form and propagate. This temperature is known as the [[Ductile-brittle transition temperature#Ductile-brittle transition temperature|critical ductile-brittle transition temperature]]. Ships in the North Atlantic were exposed to temperatures that could fall below this critical point.<ref>{{cite report|url=http://www.shippai.org/fkd/en/cfen/CB1011020.html |title=Case Details - Brittle fracture of Liberty Ships |website=Failure Knowledge Database|last=Kobayashi |first=Hideo|date=n.d.|quote= "The brittle fractures that occurred in the Liberty Ships were caused by low notch toughness at low temperature of steel at welded joint, which started at weld cracks or stress concentration points of the structure. External forces or residual stress due to welding progress the fracture. Almost all accidents by brittle fractures occurred in winter (low temperature). In some cases, residual stress is main cause of fracture." |publisher=Association for the Study of Failure}}</ref> The predominantly welded hull construction, effectively a continuous sheet of steel, allowed small cracks to propagate unimpeded, unlike in a hull made of separate plates riveted together. One common type of crack nucleated at the square corner of a hatch which coincided with a welded seam, both the corner and the weld acting as [[Stress concentration|stress concentrators]]. Furthermore, the ships were frequently grossly overloaded, greatly increasing stress, and some of the structural problems occurred during or after severe storms that would have further increased stress. Minor revisions to the hatches and various reinforcements were applied to the Liberty ships to arrest the cracking problem. These are some of the first structural tests that gave birth to the study of materials. The successor [[Victory ship]]s used the same steel, also welded rather than riveted, but spacing between frames was widened from {{convert|30|in|mm}} to {{convert|36|in|mm}}, making the ships less stiff and more able to flex.{{citation needed|date=September 2023}} |

||

=== |

==== Consequences and results ==== |

||

The sinking of the Liberty ships led to a new way of thinking about ship design and manufacturing. Ships today avoid the use of rectangular corners to avoid [[stress concentration]]. New types of steel were developed that have higher [[fracture toughness]], especially at lower temperatures. In addition, more talented and educated welders can produce welds without, or at least with fewer, flaws. While the context and time in which Liberty ships were constructed resulted in many failures, the lessons learned led to new innovations that allow for more efficient and safer shipbuilding today.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Zhang |first=Wei |date=December 2016 |title=Technical Problem Identification for the Failures of the Liberty Ships |journal=Challenges |language=en |volume=7 |issue=2 |pages=20 |doi=10.3390/challe7020020 |doi-access=free |issn=2078-1547}}</ref> |

|||

In September 1943 strategic plans and shortage of more suitable hulls required that Liberty ships be pressed into emergency use as troop transports with about 225 eventually converted for this purpose.<ref name=Wardlow>{{cite book |last1=Wardlow |first1=Chester |year=1956 |title=The Technical Services—The Transportation Corps: Movements, Training, And Supply |series=United States Army In World War II |location=Washington, DC |publisher=Center Of Military History, United States Army |isbn= |lccn=55060003 |pages=145–148}}</ref> The first general conversions were hastily undertaken by the [[War Shipping Administration]] (WSA) so that the ships could join convoys on the way to North Africa for [[Operation Torch]].<ref name=Wardlow /> Even earlier the [[South West Pacific Area (command)|Southwest Pacific Area command's]] U.S. Army Services of Supply had converted at least one, {{SS|William Ellery Channing||2}}, in Australia into an assault troop carrier with landing craft ([[Landing Craft Infantry|LCIs]] and [[LCVP (United States)|LCVs]]) and troops with the ship being reconverted for cargo after the Navy was given exclusive responsibility for amphibious assault operations.<ref>{{cite book |last=Masterson |first=Dr. James R. |authorlink= |title=U. S. Army Transportation In The Southwest Pacific Area 1941–1947 |year=1949 |publisher=Transportation Unit, Historical Division, Special Staff, U. S. Army |location=Washington, D. C. |isbn= |pages=570–571}}</ref> Others in the Southwest Pacific were turned into makeshift troop transports for New Guinea operations by installing field kitchens on deck, latrines aft between #4 and #5 hatches flushed by hoses attached to fire hydrants and about 900 troops sleeping on deck or in [[Deck (ship)#Common names for decks|'tween deck]] spaces.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bykofsky |first1=Joseph |last2=Larson |first2=Harold |year=1990 |title=The Technical Services—The Transportation Corps: Operations Overseas |series=United States Army In World War II |location=Washington, DC |publisher=Center Of Military History, United States Army |isbn= |lccn=56060000 |page=450}}</ref> While most of the Liberties converted were intended to carry no more than 550 troops, thirty-three were converted to transport 1,600 on shorter voyages from mainland U.S. ports to Alaska, Hawaii and the Caribbean.<ref name=WardlowOPS>{{cite book |last1=Wardlow |first1=Chester |year=1999 |title=The Technical Services—The Transportation Corps: Responsibilities, Organization, And Operations |series=United States Army In World War II |location=Washington, DC |publisher=Center Of Military History, United States Army |isbn= |lccn=99490905 |pages=300–301}}</ref> |

|||

== Service == |

|||

The issue of hull cracks caused concern with the [[United States Coast Guard]], which recommended that Liberty ships be withdrawn from troop carrying in February 1944 although military commitments required their continued use.<ref name=Wardlow /> The more direct problem was the general unsuitability of the ships as troop transports, particularly with the hasty conversions in 1943, that generated considerable complaints regarding poor mess, food and water storage, sanitation, heating / ventilation and a lack of medical facilities.<ref name=Wardlow /> After the Allied victory in North Africa, about 250 Libertys were engaged in transporting prisoners of war to the United States.<ref name=WardlowOPS /> By November 1943 the Army's Chief of Transportation, Maj. Gen. Charles P. Gross, and WSA, whose agents operated the ships, reached agreement on improvements, but operational requirements forced an increase of the maximum number of troops transported in a Liberty from 350 to 500.<ref name=Wardlow /> The increase in production of more suitable vessels did allow for returning the hastily converted Liberty ships to cargo-only operations by May 1944.<ref name=Wardlow /> Despite complaints, reservations, Navy requesting its personnel not travel aboard Liberty troopers and even Senate comment, the military necessities required use of the ships. The number of troops was increased to 550 on 200 Liberty ships for redeployment to the Pacific. The need for the troopship conversions persisted into the immediate postwar period in order to return troops from overseas as quickly as possible.<ref name=Wardlow /> |

|||

===Use |

===Use as troopships=== |

||

[[File:SS John W. Brown aerial photo.jpg|thumb|Aerial photograph of the Liberty ship {{SS|John W. Brown}} outbound from the United States carrying a large deck cargo after her conversion to a "Limited Capacity [[Troopship]]". It probably was taken in the summer of 1943 during her second voyage.]] |

|||

[[File:SS Lawton B. Evans Shell practice.jpg|thumb|upright|Seamen during shell loading practice aboard SS ''Lawton B. Evans'' in 1943]] |

|||

In September 1943 strategic plans and shortage of more suitable hulls required that Liberty ships be pressed into emergency use as troop transports with about 225 eventually converted for this purpose.<ref name=Wardlow1>{{cite book |last1=Wardlow |first1=Chester |year=1956 |title=The Technical Services – The Transportation Corps: Movements, Training, And Supply |series=United States Army In World War II |location=Washington, DC |publisher=Center Of Military History, United States Army |lccn=55060003 |pages=145–148}}</ref> The first general conversions were hastily undertaken by the [[War Shipping Administration]] (WSA) so that the ships could join convoys on the way to North Africa for [[Operation Torch]].<ref name=Wardlow /> Even earlier the [[South West Pacific Area (command)|Southwest Pacific Area command's]] U.S. Army Services of Supply had converted at least one, {{SS|William Ellery Channing||2}}, in Australia into an assault troop carrier with landing craft ([[Landing Craft Infantry|LCIs]] and [[LCVP (United States)|LCVs]]) and troops with the ship being reconverted for cargo after the Navy was given exclusive responsibility for amphibious assault operations.<ref>{{cite book |last=Masterson |first=Dr. James R. |title=U. S. Army Transportation In The Southwest Pacific Area 1941–1947 |year=1949 |publisher=Transportation Unit, Historical Division, Special Staff, U. S. Army |location=Washington, D. C. |pages=570–571}}</ref> Others in the Southwest Pacific were turned into makeshift troop transports for New Guinea operations by installing field kitchens on deck, latrines aft between #4 and #5 hatches flushed by hoses attached to fire hydrants and about 900 troops sleeping on deck or in [[Deck (ship)#Common names for decks|'tween deck]] spaces.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bykofsky |first1=Joseph |last2=Larson |first2=Harold |year=1990 |title=The Technical Services – The Transportation Corps: Operations Overseas |series=United States Army In World War II |location=Washington, DC |publisher=Center Of Military History, United States Army |lccn=56060000 |page=450}}</ref> While most of the Liberty ships converted were intended to carry no more than 550 troops, thirty-three were converted to transport 1,600 on shorter voyages from mainland U.S. ports to Alaska, Hawaii and the Caribbean.<ref name=WardlowOPS>{{cite book |last1=Wardlow |first1=Chester |year=1999 |title=The Technical Services – The Transportation Corps: Responsibilities, Organization, And Operations |series=United States Army In World War II |location=Washington, DC |publisher=Center Of Military History, United States Army |lccn=99490905 |pages=300–301}}</ref> |

|||

On 27 September 1942 the {{SS|Stephen Hopkins}} was the first (and only) US merchant ship to sink a German surface combatant during the war. Ordered to stop, ''Stephen Hopkins'' refused to surrender, so the heavily armed German [[commerce raider]] {{ship|German auxiliary cruiser|Stier||2}} and her tender {{MS|Tannenfels|1938|2}} with one machine gun opened fire. Although greatly outgunned, the crew of ''Stephen Hopkins'' fought back, replacing the [[United States Navy Armed Guard|Armed Guard]] crew of the ship's lone {{convert|4|inch|mm|adj=on}} gun with volunteers as they fell. The fight was short, and both ships were wrecks.<ref>Sawyer, L. A. and Mitchell, W. H. ''The Liberty Ships: The History of the "Emergency" Type Cargo Ships Constructed in the United States During the Second World War,'' Second Edition, pp. 13, 141–2, Lloyd's of London Press Ltd., London, England, 1985. {{ISBN|1-85044-049-2}}.</ref> |

|||

The problem of hull cracks caused concern with the [[United States Coast Guard]], which recommended that Liberty ships be withdrawn from troop carrying in February 1944 although military commitments required their continued use.<ref name=Wardlow /> The more direct problem was the general unsuitability of the ships as troop transports, particularly with the hasty conversions in 1943, that generated considerable complaints regarding poor mess, food and water storage, sanitation, heating / ventilation and a lack of medical facilities.<ref name=Wardlow /> After the Allied victory in North Africa, about 250 Liberty ships were engaged in transporting prisoners of war to the United States.<ref name=WardlowOPS /> By November 1943 the Army's Chief of Transportation, Maj. Gen. [[Charles P. Gross]], and WSA, whose agents operated the ships, reached agreement on improvements, but operational requirements forced an increase of the maximum number of troops transported in a Liberty from 350 to 500.<ref name=Wardlow /> The increase in production of more suitable vessels did allow for returning the hastily converted Liberty ships to cargo-only operations by May 1944.<ref name=Wardlow /> Despite complaints, reservations, Navy requesting its personnel not travel aboard Liberty troopers and even Senate comment, the military necessities required use of the ships. The number of troops was increased to 550 on 200 Liberty ships for redeployment to the Pacific. The need for the troopship conversions persisted into the immediate postwar period in order to return troops from overseas as quickly as possible.<ref name=Wardlow /> |

|||

On 10 March 1943 {{SS|Lawton B. Evans}} became the only ship ever to survive an attack by the {{GS|U-221}}.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.uboat.net/boats/successes/u221.html|title=Lawton B. Evans (American Steam merchant) – Ships hit by German U-boats during WWII|publisher=Gudmundur Helgason uboat.net |accessdate=30 November 2016}}</ref> The following year from 22 to 30 January 1944, ''Lawton B. Evans'' was involved in the [[Battle of Anzio]] in Italy. It was under repeated bombardment from shore batteries and aircraft throughout an eight-day period. It endured a prolonged barrage of shrapnel, machine-gun fire and bombs. The gun crew fought back with shellfire and shot down five German planes, contributing to the success of the landing operations.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SS_Lawton_B._Evans_Commendation.pdf|title=Pers-68-MH MM/822 62 83|publisher=Bureau Of Naval Personnel |accessdate=30 November 2016}}</ref> |

|||

===Combat=== |

|||

[[File:SS Lawton B. Evans Shell practice.jpg|thumb|upright|Seamen during shell loading practice aboard SS ''[[SS Lawton B. Evans|Lawton B. Evans]]'' in 1943]] |

|||

On 27 September 1942 the {{SS|Stephen Hopkins}} was the only US merchant ship to sink a German surface combatant during the war. Ordered to stop, ''Stephen Hopkins'' refused to surrender, so the heavily armed German [[commerce raider]] {{ship|German auxiliary cruiser|Stier||2}} and her tender {{MS|Tannenfels|1938|2}} with one machine gun opened fire. Although greatly outgunned, the crew of ''Stephen Hopkins'' fought back, replacing the [[United States Navy Armed Guard|Armed Guard]] crew of the ship's single {{convert|4|inch|mm|adj=on}} gun with volunteers as they fell. The fight was short, and both ships were wrecks.{{sfn|Sawyer|Mitchell|1985|pp=13, 141–142}} |

|||

On 10 March 1943 {{SS|Lawton B. Evans}} became the only ship to survive an attack by the {{GS|U-221}}.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.uboat.net/boats/successes/u221.html|title=Lawton B. Evans (American Steam merchant) – Ships hit by German U-boats during WWII|publisher=Gudmundur Helgason uboat.net |access-date=30 November 2016}}</ref> The following year from 22 to 30 January 1944, ''Lawton B. Evans'' was involved in the [[Battle of Anzio]] in Italy. It was under repeated bombardment from shore batteries and aircraft for eight days. It endured a prolonged barrage of shelling, machine-gun fire and bombs. The ship shot down five German planes.<ref>[[:commons:File:SS_Lawton_B._Evans_Commendation.pdf]]{{Circular reference|date=March 2024}}</ref> |

|||

===After the war=== |

===After the war=== |

||

[[File: |

[[File:Jeremiah_O.Brien_2022-c.jpg|thumb|left|SS ''Jeremiah O'Brien'', 2022]] |

||

More than 2,400 Liberty ships survived the war. Of these, 835 made up the postwar cargo fleet. Greek entrepreneurs bought 526 ships and Italians bought 98. Shipping magnates including [[John Fredriksen]]<ref>{{cite web |title= |

More than 2,400 Liberty ships survived the war. Of these, 835 made up the postwar cargo fleet. Greek entrepreneurs bought 526 ships and Italians bought 98. Shipping magnates including [[John Fredriksen]],<ref>{{cite web |title=John Fredriksen |url=https://nbl.snl.no/John_Fredriksen |work=Norsk Biografisk Lexsikon |date=25 February 2020 |access-date=9 July 2020 |language=no}}</ref> John Theodoracopoulos,<ref>The Shipping World and Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering News, 1952, p. 148.</ref> [[Aristotle Onassis]],<ref name=Elphick401>{{harvnb|Elphick|2006|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=4_V-uphhRPsC&pg=PA401 401]}}</ref> [[Stavros Niarchos]],<ref name=Elphick401/> [[Stavros George Livanos]], the Goulandris brothers,<ref name=Elphick401/> and the Andreadis, Tsavliris, Achille Lauro, Grimaldi and Bottiglieri families were known to have started their fleets by buying Liberty ships. [[Andrea Corrado]], the dominant Italian shipping magnate at the time, and leader of the Italian shipping delegation, rebuilt his fleet under the programme. Weyerhaeuser operated a fleet of six Liberty Ships (which were later extensively refurbished and modernized) carrying lumber, newsprint, and general cargo for years after the end of the war. |

||

Some Liberty ships were lost after the war to [[naval mine]]s that were inadequately cleared. ''Pierre Gibault'' was scrapped after hitting a mine in a previously cleared area off the Greek island of [[Kythira]] in June 1945,{{sfn|Elphick|2006|p=309}} and the same month saw ''Colin P. Kelly Jnr'' take mortal damage from a mine hit off the Belgian port of [[Ostend]].{{sfn|Elphick|2006|p=166}} In August 1945, ''William J. Palmer'' was carrying horses from New York to Trieste when she rolled over and sank 15 minutes after hitting a mine a few miles from destination. All crew members, and six horses were saved.{{sfn|Elphick|2006|p=271}} ''Nathaniel Bacon'' ran into a minefield off [[Civitavecchia]], Italy in December 1945, caught fire, was beached, and broke in two; the larger section was welded onto another Liberty half hull to make a new ship 30 feet longer, named ''Boccadasse''.{{sfn|Elphick|2006|p=108}} |

|||

The term "Liberty-size cargo" for {{convert|10000|LT|MT|sigfig=3}} may still be used in the shipping business.{{citation needed|date=April 2018}} |

|||

As late as December 1947, ''Robert Dale Owen'', renamed ''Kalliopi'' and sailing under the Greek flag, broke in three and sank in the northern [[Adriatic Sea]] after hitting a mine.{{sfn|Elphick|2006|p=402}} Other Liberty ships lost to mines after the end of the war include ''John Woolman'', ''Calvin Coolidge'', ''Cyrus Adler'', and ''Lord Delaware''.{{sfn|Elphick|2006|p=325}} |

|||

Some Liberty ships were lost after the war to [[naval mine]]s that were inadequately cleared. ''Pierre Gibault'' was scrapped after hitting a mine in a previously cleared area off the Greek island of [[Kythira]] in June 1945,<ref>Elphick, ''Liberty'', p. 309.</ref> and the same month saw ''Colin P. Kelly Jnr'' take mortal damage from a mine hit off the Belgian port of [[Ostend]].<ref>Elphick, ''Liberty'', p. 166.</ref> In August 1945, ''William J. Palmer'' was carrying horses from New York to Trieste when she rolled over and sank 15 minutes after hitting a mine a few miles from destination. All crew members, and six horses were saved.<ref>Elphick, ''Liberty'', p. 271.</ref> ''Nathaniel Bacon'' ran into a minefield off [[Civitavecchia]], Italy in December 1945, caught fire, was beached, and broke in two; the larger section was welded onto another Liberty half hull to make a new ship 30 feet longer, named ''Boccadasse''.<ref>Elphick, ''Liberty'', p. 108.</ref> |

|||

On April 16, 1947, a Liberty ship owned by the [[Compagnie Générale Transatlantique]] called the ''Grandcamp'' (originally built as the SS Benjamin R. Curtis) docked in Texas City, Texas to load a cargo of 2,300 tons of [[ammonium nitrate]] fertilizer. A fire broke out on board which eventually caused the entire ammonium nitrate cargo to explode. The massive explosion levelled Texas City and caused fires which detonated more ammonium nitrate in a nearby ship and warehouse. It was one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in US history. This incident is known as the [[Texas City disaster]] today.<ref>{{Cite web | url=http://www.local1259iaff.org/report.htm | title=Texas City Disaster Report }}</ref> |

|||

As late as December 1947, ''Robert Dale Owen'', renamed ''Kalliopi'' and sailing under the Greek flag, broke in three and sank in the northern [[Adriatic Sea]] after hitting a mine.<ref>Elphick, ''Liberty'', p. 402.</ref> Other Liberty ships lost postwar to mines include ''John Woolman'', ''Calvin Coolidge'', ''Cyrus Adler'', and ''Lord Delaware''.<ref>Elphick, ''Liberty'', p. 325.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Quartette 03 noaa casserley.jpg|thumb|Propeller of the Liberty ship ''Quartette'' which ran aground in 1952 on the [[Pearl and Hermes Atoll]] in the Pacific Ocean]] |

|||

In 1953, the [[Commodity Credit Corporation]] (CCC), began storing surplus grain in Liberty ships located in the [[Hudson River Reserve Fleet|Hudson River]], [[James River Reserve Fleet|James River]], Olympia, and Astoria [[National Defense Reserve Fleet]]'s. In 1955, 22 ships in the [[Suisun Bay Reserve Fleet]] were withdrawn to be loaded with grain and were then transferred to the Olympia Fleet. In 1956, four ships were withdrawn from the Wilmington Fleet and transferred, loaded with grain, to the Hudson River Fleet.<ref>{{cite book |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=9hZFermhcf4C |title= Department of Agriculture Appropriations for 1961 |date= 1960 |accessdate= 28 January 2020}}</ref> |

|||

On December 21, 1952, the SS ''Quartette'', a {{convert|422|ft|m|adj=mid|-long}} Liberty Ship of 7,198 [[gross register ton]]s, struck the eastern reef of the [[Pearl and Hermes atoll]] at a speed of {{Cvt|10.5|kn||0}}. The ship was driven further onto the reef by rough waves and {{Cvt|35|mph|}} winds, which collapsed the forward bow and damaged two forward holds.<ref>{{cite web|title=Papahānaumokuākea Expedition 2007: Liberty Ship SS Quartette |url=https://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/maritime/expeditions/pmnm/quartette.html |website=Sanctuaries.noaa.gov |access-date=June 11, 2018}}</ref> The crew was evacuated by the [[SS Frontenac Victory|SS ''Frontenac Victory'']] the following day. The [[salvage tug]] ''Ono'' arrived on December 25 to attempt to tow the ship clear, but persistent stormy weather forced a delay of the rescue attempt. On January 3, before another rescue attempt could be made, the ship's anchors tore loose and the ''Quartette'' was blown onto the reef, and deemed a [[total loss]]. Several weeks later, it snapped in half at the [[keel]] and the two pieces sank.<ref>{{cite web |title=Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument: Liberty Ship SS Quartette|website=Papahanaumokuakea.gov |url=https://www.papahanaumokuakea.gov/maritime/quartette.html |access-date=December 26, 2017}}</ref> The wreck site now serves as an [[artificial reef]] which provides a habitat for many fish species.<ref name="PMNM-PAHA">{{cite web|title=Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument: Pearl and Hermes Atoll|website=Papahanaumokuakea.gov |url=https://www.papahanaumokuakea.gov/visit/pearl.html|access-date=December 26, 2017}}</ref> |

|||

In 1953, the [[Commodity Credit Corporation]] (CCC), began storing surplus grain in Liberty ships located in the [[Hudson River Reserve Fleet|Hudson River]], [[James River Reserve Fleet|James River]], Olympia, and Astoria [[National Defense Reserve Fleet|National Defense Reserve Fleets]]. In 1955, 22 ships in the [[Suisun Bay Reserve Fleet]] were withdrawn to be loaded with grain and were then transferred to the Olympia Fleet. In 1956, four ships were withdrawn from the Wilmington Fleet and transferred, loaded with grain, to the Hudson River Fleet.<ref>{{cite book |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=9hZFermhcf4C |title= Department of Agriculture Appropriations for 1961 |date= 1960 |access-date= 28 January 2020}}</ref> |

|||

Between 1955 and 1959, 16 former Liberty ships were repurchased by the United States Navy and converted to the {{sclass-|Guardian|radar picket ship|1}}s for the [[Distant Early Warning Line#Atlantic and Pacific Barrier|Atlantic and Pacific Barrier]]. |

|||

Between 1955 and 1959, 16 former Liberty ships were repurchased by the United States Navy and converted to the {{sclass|Guardian|radar picket ship|1}}s for the [[Distant Early Warning Line#Atlantic and Pacific Barrier|Atlantic and Pacific Barrier]]. |

|||

In the 1960s, three Liberty ships and two Victory ships were reactivated and converted to [[technical research ship]]s with the [[hull classification symbol]] AGTR (auxiliary, technical research) and used to gather electronic intelligence and for radar picket duties by the United States Navy. The Liberty ships SS ''Samuel R. Aitken'' became {{USS|Oxford|AGTR-1|6}}, SS ''Robert W. Hart'' became {{USS|Georgetown|AGTR-2|6}}, SS ''J. Howland Gardner'' became {{USS|Jamestown|AGTR-3|6}} with the Victory ships being {{SS|Iran Victory}} which became {{USS|Belmont|AGTR-4|6}} and {{SS|Simmons Victory}} becoming {{USS|Liberty|AGTR-5|6}}.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.marad.dot.gov/sh/ShipHistory/Detail/4364 |title=''Samuel R. Aitken'' |author=Maritime Administration |date= |work=Ship History Database |publisher= U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration |accessdate=1 November 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.marad.dot.gov/sh/ShipHistory/Detail/4203 |title=''Robert W. Hart'' |author=Maritime Administration Vessel Status Card |date= |work=Ship History Database |publisher= U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration |accessdate=1 November 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.marad.dot.gov/sh/ShipHistory/Detail/2348 |title=''J. Howland Gardner'' |author=Maritime Administration Vessel Status Card |date= |work=Ship History Database |publisher= U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration |accessdate=1 November 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.marad.dot.gov/sh/ShipHistory/Detail/2307 |title=''Iran Victory'' |author=Maritime Administration Vessel Status Card |date= |work=Ship History Database |publisher= U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration |accessdate=1 November 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.marad.dot.gov/sh/ShipHistory/Detail/4577 |title=''Simmons Victory'' |author=Maritime Administration Vessel Status Card |date= |work=Ship History Database |publisher= U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration |accessdate=1 November 2014}}</ref> All of these ships were [[Ship decommissioning|decommissioned]] and struck from the [[Naval Vessel Register]] in 1969 and 1970. |

|||

In the 1960s, three Liberty ships and two Victory ships were reactivated and converted to [[technical research ship]]s with the [[hull classification symbol]] AGTR (auxiliary, technical research) and used to gather electronic intelligence and for radar picket duties by the United States Navy. The Liberty ships SS ''Samuel R. Aitken'' became {{USS|Oxford|AGTR-1|6}}, SS ''Robert W. Hart'' became {{USS|Georgetown|AGTR-2|6}}, SS ''J. Howland Gardner'' became {{USS|Jamestown|AGTR-3|6}} with the Victory ships being {{SS|Iran Victory}} which became {{USS|Belmont|AGTR-4|6}} and {{SS|Simmons Victory}} becoming {{USS|Liberty|AGTR-5|6}}.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.marad.dot.gov/sh/ShipHistory/Detail/4364 |title=''Samuel R. Aitken'' |author=Maritime Administration |work=Ship History Database |publisher=U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration |access-date=1 November 2014 |archive-date=4 November 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161104080755/https://www.marad.dot.gov/sh/ShipHistory/Detail/4364 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.marad.dot.gov/sh/ShipHistory/Detail/4203 |title=''Robert W. Hart'' |author=Maritime Administration Vessel Status Card |work=Ship History Database |publisher=U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration |access-date=1 November 2014 |archive-date=4 March 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304054847/http://www.marad.dot.gov/sh/ShipHistory/Detail/4203 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.marad.dot.gov/sh/ShipHistory/Detail/2348 |title=''J. Howland Gardner'' |author=Maritime Administration Vessel Status Card |work=Ship History Database |publisher=U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration |access-date=1 November 2014 |archive-date=4 March 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304054806/http://www.marad.dot.gov/sh/ShipHistory/Detail/2348 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.marad.dot.gov/sh/ShipHistory/Detail/2307 |title=''Iran Victory'' |author=Maritime Administration Vessel Status Card |work=Ship History Database |publisher=U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration |access-date=1 November 2014 |archive-date=4 March 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304114548/http://www.marad.dot.gov/sh/ShipHistory/Detail/2307 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.marad.dot.gov/sh/ShipHistory/Detail/4577 |title=''Simmons Victory'' |author=Maritime Administration Vessel Status Card |work=Ship History Database |publisher=U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration |access-date=1 November 2014 |archive-date=4 March 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304123950/http://www.marad.dot.gov/sh/ShipHistory/Detail/4577 |url-status=dead }}</ref> All of these ships were [[Ship decommissioning|decommissioned]] and struck from the [[Naval Vessel Register]] in 1969 and 1970. |

|||

USS ''Liberty'' was a ''Belmont''-class technical research ship (electronic spy ship) that was attacked by [[Israel Defense Forces]] during the 1967 [[Six-Day War]]. She was built and served in World War II as SS ''Simmons Victory'', as a Victory cargo ship. |

|||

[[File:Liberty Ships 1c.jpg|thumb|Liberty ships mothballed at Tongue Point, Astoria, Oregon, 1965]] |

|||

From 1946 to 1963 the [[United States Navy reserve fleets|Pacific Ready Reserve Fleet]] – Columbia River Group, retained as many as 500 ships.<ref>http://navy.memorieshop.com/Reserve-Fleets/Astoria/index.html</ref> |

|||

[[File:Liberty Ships |

[[File:Liberty Ships 2c.jpg|thumb|Liberty Ships mothballed at Tongue Point, Astoria, Oregon, 1965]] |

||

[[File: |

[[File:Novorossiysk IMO 5258585 G Hamburg 03-1974.jpg|thumb|''[[SS Edward Eggleston|Novorossiysk]]'', delivered 1943 to USSR, sailed until 1974]] |

||

From 1946 to 1963, the [[United States Navy reserve fleets|Pacific Ready Reserve Fleet]] – Columbia River Group, retained as many as 500 Liberty ships.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://navy.memorieshop.com/Reserve-Fleets/Astoria/index.html |title=Tongue Point Navy Ship Yard |access-date=24 April 2015 |archive-date=21 June 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150621004417/http://navy.memorieshop.com/Reserve-Fleets/Astoria/index.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

In 1946 Liberty ships were mothballed in the [[Hudson River Reserve Fleet]] near [[Tarrytown, New York|Tarrytown]], New York. At its peak in 1965 189 hulls were stored there. The last two were sold for scrap to Spain in 1971 and the reserve permanently shut down.<ref>The Hudson River National Defense Reserve Fleet [http://navalmarinearchive.com/research/hudson_ghost_fleet.html] "The fleet was at its peak with 189 ships in July of 1965."</ref><ref>Image: Mothball Fleet of WWII Liberty Ships in Hudson River off Jones Point 1957 [https://www.panoramio.com/photo/4164580 Picture of mothballed liberty ships]</ref> |

|||

In 1946, Liberty ships were [[Mothball#In popular culture|mothball]]ed in the [[Hudson River Reserve Fleet]] near [[Tarrytown, New York]]. At its peak in 1965, 189 hulls were stored there. The last two were sold for scrap to Spain in 1971 and the reserve permanently shut down.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://navalmarinearchive.com/research/hudson_ghost_fleet.html|title=Hudson River National Defense Reserve Fleet|website=Navalmarinearchive.com|access-date=11 March 2022|archive-date=7 April 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140407075147/http://navalmarinearchive.com/research/hudson_ghost_fleet.html|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>Image: Mothball Fleet of WWII Liberty Ships in Hudson River off Jones Point 1957 [https://www.panoramio.com/photo/4164580 Picture of mothballed liberty ships]</ref> |

|||

[[File:SS Hellas Liberty (restored).jpg|thumb|right|SS ''Hellas Liberty'' (ex-SS ''Arthur M. Huddell'') in June 2010]] |

|||

[[File:SS Hellas Liberty (restored).jpg|thumb|right|[[SS Arthur M. Huddell|SS ''Hellas Liberty'']] (ex-SS ''Arthur M. Huddell'') in June 2010]] |

|||

Only two operational Liberty ships, {{SS|John W. Brown}} and {{SS|Jeremiah O'Brien}}, remain. ''John W. Brown'' has had a long career as a [[school ship]] and many internal modifications, while ''Jeremiah O'Brien'' remains largely in her original condition. Both are [[museum ship]]s that still put out to sea regularly. In 1994, ''Jeremiah O'Brien'' steamed from San Francisco to England and France for the 50th anniversary of [[D-Day]], the only large ship from the original [[Operation Overlord]] fleet to participate in the anniversary. In 2008, {{SS|Arthur M. Huddell}}, a ship converted in 1944 into a pipe transport to support [[Operation Pluto]],<ref>{{cite web |last=Walker, Ashley (Historic American Engineering Record) |title=Operation "Pluto" – Arthur M. Huddell, James River Reserve Fleet, Newport News, Newport News, VA |publisher= Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 |year=2009 |url=https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/va2040.sheet.00020a/ |accessdate=5 October 2014}}</ref> was transferred to Greece and converted to a floating museum dedicated to the history of the Greek merchant marine;<ref>[http://www.hellasliberty.gr/ The Hellas Liberty Project] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090303132509/http://www.hellasliberty.gr/ |date= 3 March 2009 }}</ref> although missing major components were restored this ship is no longer operational. |

|||

Only two operational Liberty ships, {{SS|John W. Brown}} and {{SS|Jeremiah O'Brien}}, remain. ''John W. Brown'' has had a long career as a [[school ship]] and many internal modifications, while ''Jeremiah O'Brien'' remains largely in her original condition. Both are [[museum ship]]s that still put out to sea regularly. In 1994, ''Jeremiah O'Brien'' steamed from San Francisco to England and France for the 50th anniversary of [[D-Day]], the only large ship from the original [[Operation Overlord]] fleet to participate in the anniversary. In 2008, {{SS|Arthur M. Huddell}}, a ship converted in 1944 into a pipe transport to support [[Operation Pluto]],<ref>{{cite web |last=Walker, Ashley (Historic American Engineering Record) |title=Operation "Pluto" – Arthur M. Huddell, James River Reserve Fleet, Newport News, VA |publisher= Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. |year=2009 |url=https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/va2040.sheet.00020a/ |access-date=5 October 2014}}</ref> was transferred to Greece and converted to a floating museum dedicated to the history of the Greek merchant marine;<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.hellasliberty.gr/ |title=The Hellas Liberty Project |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090303132509/http://www.hellasliberty.gr/ |archive-date= 3 March 2009 }}</ref> although missing major components were restored this ship is no longer operational. |

|||