Concentrated solar power: Difference between revisions

m Open access bot: doi updated in citation with #oabot. |

|||

| (261 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Use of mirror or lens assemblies to heat a working fluid for electricity generation}} |

|||

{{distinguish|concentrator photovoltaics}} |

|||

{{Distinguish|concentrator photovoltaics}} |

|||

[[File:Crescent Dunes Solar December 2014.JPG|thumb|A [[solar power tower]] concentrating light via 10,000 mirrored [[Heliostat|heliostats]] spanning {{convert|13000000|sqft|km2|2|abbr=on|round=|spell=in}}.|alt=The mothballed Crescent Dunes Solar Energy Project]] |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=January 2021}} |

|||

[[File:Global Map of Direct Normal Radiation 01.png|thumb|upright=1.5|Global Direct Normal Irradiation.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://globalwindatlas.info/ |title=Global Wind Atlas.}}</ref>]] |

|||

[[File:Crescent Dunes Solar December 2014.JPG|thumb|A [[solar power tower]] at [[Crescent Dunes Solar Energy Project]] concentrating light via 10,000 mirrored [[heliostat]]s spanning {{convert|13000000|sqft|km2|2|abbr=on|round=|spell=in}}.|alt=An areal view of a large circle of thousands of bluish mirrors in a tan desert]] |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=August 2018}} |

|||

[[File:Ivanpah Solar Power Facility (2).jpg|thumb|The three towers of the [[Ivanpah Solar Power Facility]] ]] |

[[File:Ivanpah Solar Power Facility (2).jpg|thumb|The three towers of the [[Ivanpah Solar Power Facility]] ]] |

||

[[File:Solar Plant kl.jpg|thumb|Part of the 354 MW [[SEGS]] solar complex in northern [[San Bernardino County, California]] ]] |

[[File:Solar Plant kl.jpg|thumb|Part of the 354 MW [[SEGS]] solar complex in northern [[San Bernardino County, California]] ]] |

||

[[File:KhiSolarOneBirdView.jpg|thumb|Bird's eye view of [[Khi Solar One]], [[South Africa]] ]]'''Concentrated solar power''' ('''CSP''', also known as '''concentrating solar power''', '''concentrated solar thermal''') systems generate [[solar power]] by using mirrors or lenses to concentrate a large area of sunlight into a receiver.<ref name=":0">{{cite web |last1=Kimi |first1=Imad |title=Photovoltaic vs concentrated solar power the key differences |url=https://www.voltagea.com/2022/12/photovoltaic-vs-concentrated-solar-power.html |website=Voltagea |publisher=Dr. imad |access-date=29 December 2022}}</ref> [[Electricity]] is generated when the concentrated light is converted to heat ([[solar thermal energy]]), which drives a [[heat engine]] (usually a [[steam turbine]]) connected to an electrical [[power generator]]<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Boerema |first1=Nicholas |last2=Morrison |first2=Graham |last3=Taylor |first3=Robert |last4=Rosengarten |first4=Gary |date=1 November 2013 |title=High temperature solar thermal central-receiver billboard design |journal=Solar Energy |volume=97 |pages=356–368 |doi=10.1016/j.solener.2013.09.008|bibcode=2013SoEn...97..356B }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Law |first1=Edward W. |last2=Prasad |first2=Abhnil A. |last3=Kay |first3=Merlinde |last4=Taylor |first4=Robert A. |date=1 October 2014 |title=Direct normal irradiance forecasting and its application to concentrated solar thermal output forecasting – A review |journal=Solar Energy |volume=108 |pages=287–307 |doi=10.1016/j.solener.2014.07.008|bibcode=2014SoEn..108..287L }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Law |first1=Edward W. |last2=Kay |first2=Merlinde |last3=Taylor |first3=Robert A. |date=1 February 2016 |title=Calculating the financial value of a concentrated solar thermal plant operated using direct normal irradiance forecasts |journal=Solar Energy |volume=125 |pages=267–281 |doi=10.1016/j.solener.2015.12.031|bibcode=2016SoEn..125..267L }}</ref> or powers a [[thermochemical]] reaction.<ref name="Sunshine to Petrol">{{cite web |title=Sunshine to Petrol |url=http://energy.sandia.gov/wp/wp-content/gallery/uploads/S2P_SAND2009-5796P.pdf |publisher=Sandia National Laboratories |access-date=11 April 2013 |archive-date=19 February 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130219194404/http://energy.sandia.gov/wp/wp-content/gallery/uploads/S2P_SAND2009-5796P.pdf }}</ref><ref name="SunShot">{{cite web |title=Integrated Solar Thermochemical Reaction System |url=http://www1.eere.energy.gov/solar/sunshot/csp_sunshotrnd_pnnl.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130415082843/http://www1.eere.energy.gov/solar/sunshot/csp_sunshotrnd_pnnl.html |archive-date=2013-04-15 |website=U.S. Department of Energy |access-date=11 April 2013}}</ref><ref name="NYT41013">{{cite news |title=New Solar Process Gets More Out of Natural Gas |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/11/business/energy-environment/new-solar-process-gets-more-out-of-natural-gas.html |access-date=11 April 2013 |newspaper=The New York Times |date=10 April 2013 |first=Matthew L. |last=Wald }}</ref> |

|||

[[File:KhiSolarOneBirdView.jpg|thumb|Bird's eye view of [[Khi Solar One]], [[South Africa]] ]] |

|||

As of 2021, global installed capacity of concentrated solar power stood at 6.8 GW.<ref name="chinCSP"/> As of 2023, the total was 8.1 GW, with the inclusion of three new CSP projects in construction in China<ref name="auto">{{Cite web |title=China |url=https://www.solarpaces.org/worldwide-csp/csp-potential-solar-thermal-energy-by-member-nation/china/ |access-date=2023-08-12 |website=SolarPACES |language=en-US}}</ref> and in Dubai in the UAE.<ref name="auto"/> The U.S.-based National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), which maintains a global database of CSP plants, counts 6.6 GW of operational capacity and another 1.5 GW under construction.<ref>{{Cite web |title=CSP Projects Around the World |url=https://www.solarpaces.org/csp-technologies/csp-projects-around-the-world/ |access-date=2023-05-15 |website=SolarPACES |language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

'''Concentrated solar power''' ('''CSP''', also known as '''concentrating solar power''', '''concentrated solar thermal''') systems generate [[solar power]] by using mirrors or lenses to concentrate a large area of sunlight onto a receiver.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.solarpaces.org/how-csp-works/|title=How CSP Works: Tower, Trough, Fresnel or Dish|last=|first=|date=June 12, 2018|website=SolarPACES|url-status=live|archive-url=|archive-date=|access-date=November 29, 2019}}</ref> [[Electricity]] is generated when the concentrated light is converted to heat ([[solar thermal energy]]), which drives a [[heat engine]] (usually a [[steam turbine]]) connected to an electrical [[power generator]]<ref>{{cite journal |last=Boerema |first=Nicholas |last2=Morrison |first2=Graham |last3=Taylor |first3=Robert |last4=Rosengarten |first4=Gary |date=1 November 2013 |title=High temperature solar thermal central-receiver billboard design |journal=Solar Energy |volume=97 |pages=356–368 |doi=10.1016/j.solener.2013.09.008|bibcode=2013SoEn...97..356B }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Law |first=Edward W. |last2=Prasad |first2=Abhnil A. |last3=Kay |first3=Merlinde |last4=Taylor |first4=Robert A. |date=1 October 2014 |title=Direct normal irradiance forecasting and its application to concentrated solar thermal output forecasting – A review |journal=Solar Energy |volume=108 |pages=287–307 |doi=10.1016/j.solener.2014.07.008|bibcode=2014SoEn..108..287L }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Law |first=Edward W. |last2=Kay |first2=Merlinde |last3=Taylor |first3=Robert A. |date=1 February 2016 |title=Calculating the financial value of a concentrated solar thermal plant operated using direct normal irradiance forecasts |journal=Solar Energy |volume=125 |pages=267–281 |doi=10.1016/j.solener.2015.12.031|bibcode=2016SoEn..125..267L }}</ref> or powers a [[thermochemical]] reaction.<ref name="Sunshine to Petrol">{{cite web |title=Sunshine to Petrol |url=http://energy.sandia.gov/wp/wp-content/gallery/uploads/S2P_SAND2009-5796P.pdf |publisher=Sandia National Laboratories |accessdate=11 April 2013}}</ref><ref name="SunShot">{{cite web |title=Integrated Solar Thermochemical Reaction System |url=https://web.archive.org/liveweb/http://www1.eere.energy.gov/solar/sunshot/csp_sunshotrnd_pnnl.html |publisher=U.S. Department of Energy |accessdate=11 April 2013}}</ref><ref name="NYT41013">{{cite news |title=New Solar Process Gets More Out of Natural Gas |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/11/business/energy-environment/new-solar-process-gets-more-out-of-natural-gas.html |accessdate=11 April 2013 |newspaper=The New York Times |date=10 April 2013 |author=Matthew L. Wald}}</ref> |

|||

== Comparison between CSP and other electricity sources == |

|||

CSP had a global total installed capacity of 5,500 [[Megawatt|MW]] in 2018, up from 354 MW in 2005. [[Solar power in Spain|Spain]] accounted for almost half of the world's capacity, at 2,300 MW, despite no new capacity entering commercial operation in the country since 2013.<ref name="HeliosCSP">{{cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/concentrated-solar-power-increasing-cumulative-global-capacity-more-than-11-to-just-under-5-5-gw-in-2018/ |title=Concentrated Solar Power increasing cumulative global capacity more than 11% to just under 5.5 GW in 2018|accessdate=18 June 2019}}</ref> |

|||

As a thermal energy generating power station, CSP has more in common with [[thermal power station]]s such as coal, gas, or geothermal. A CSP plant can incorporate [[thermal energy storage]], which stores energy either in the form of [[sensible heat]] or as [[latent heat]] (for example, using [[molten salt]]), which enables these plants to continue supplying electricity whenever it is needed, day or night.<ref name=chcsp>{{cite web |url=https://www.solarpaces.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Blue-Book-of-Chinas-Concentrating-Solar-Power-Industry-2023.pdf |title=Blue Book of China's Concentrating Solar Power Industry 2023|access-date=6 March 2024}}</ref> This makes CSP a [[Dispatchable generation|dispatchable]] form of solar. Dispatchable [[renewable energy]] is particularly valuable in places where there is already a high penetration of photovoltaics (PV), such as [[solar power in California|California]],<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.solarpaces.org/chance-csp-california-outlaws-gas-fired-peaker-plants/ |title=New Chance for US CSP? California Outlaws Gas-Fired Peaker Plants|date=13 October 2017 |access-date=23 February 2018}}</ref> because demand for electric power peaks near sunset just as PV capacity ramps down (a phenomenon referred to as [[duck curve]]).<ref>{{cite web |last=Deign |first=Jason |title=Concentrated Solar Power Quietly Makes a Comeback |url=https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/concentrated-solar-power-quietly-makes-a-comeback |website=GreenTechMedia.com |date=24 June 2019}}</ref> |

|||

The United States follows with 1,740 MW. Interest is also notable in North Africa and the Middle East, as well as [[Solar power in India|India]] and China. |

|||

The global market was initially dominated by parabolic-trough plants, which accounted for 90% of CSP plants at one point.<ref name="saw2011">{{cite web |url=http://www.renewableenergyworld.com/rea/news/article/2011/09/renewables-bounced-back-in-2010-finds-ren21-global-report |title=Renewables Bounced Back in 2010, Finds REN21 Global Report |author=Janet L. Sawin |author2=Eric Martinot |name-list-style=amp |date=29 September 2011 |work=Renewable Energy World |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20111102183605/http://www.renewableenergyworld.com/rea/news/article/2011/09/renewables-bounced-back-in-2010-finds-ren21-global-report |archivedate=2 November 2011}}</ref> |

|||

Since about 2010, central power tower CSP has been favored in new plants due to its higher temperature operation — up to {{Convert|565|C|F|abbr=}} vs. trough's maximum of {{Convert|400|C||abbr=}} — which promises greater efficiency. |

|||

CSP is often compared to [[Growth of photovoltaics|photovoltaic]] solar (PV) since they both use solar energy. While solar PV experienced huge growth during the 2010s due to falling prices,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/as-concentrated-solar-power-bids-fall-to-record-lows-prices-seen-diverging-between-different-regions/ |title=As Concentrated Solar Power bids fall to record lows, prices seen diverging between different regions|access-date=23 February 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.kcet.org/news/redefine/rewire/solar/concentrating-solar/are-solar-power-towers-doomed-in-california.html |title=Are Solar Power Towers Doomed in California? |author=Chris Clarke |work=KCET|date=25 September 2015 }}</ref> solar CSP growth has been slow due to technical difficulties and high prices. In 2017, CSP represented less than 2% of worldwide installed capacity of solar electricity plants.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.ethz.ch/en/news-and-events/eth-news/news/2017/09/concentrating-solar-power.html |title=After the Desertec hype: is concentrating solar power still alive?|date=24 September 2017 |access-date= 24 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

Among the [[List of solar thermal power stations|larger CSP projects]] are the [[Ivanpah Solar Power Facility]] (392 MW) in the United States, which uses [[solar power tower]] technology without thermal energy storage, and the [[Ouarzazate Solar Power Station]] in Morocco,<ref>Louis Boisgibault, Fahad Al Kabbani (2020): [http://www.iste.co.uk/book.php?id=1591 ''Energy Transition in Metropolises, Rural Areas and Deserts'']. [[Wiley - ISTE]]. (Energy series) {{ISBN|9781786304995}}.</ref> which combines trough and tower technologies for a total of 510 MW with several hours of energy storage. |

|||

However, CSP can more easily store energy during the night, making it more competitive with [[dispatchable generation|dispatchable generators]] and baseload plants.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.solarpaces.org/csp-competes-with-natural-gas-not-pv/|title=CSP Doesn't Compete With PV – it Competes with Gas|date=11 October 2017 |access-date=4 March 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://cleantechnica.com/2019/06/04/concentrated-solar-power-costs-fell-46-from-2010-2018/ |title=Concentrated Solar Power Costs Fell 46% From 2010–2018|access-date=3 June 2019}}</ref><ref name="dub">{{cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/uaes-push-on-concentrated-solar-power-should-open-eyes-across-world/ |title=UAE's push on concentrated solar power should open eyes across world|access-date=29 October 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/concentrated-solar-power-dropped-50-in-six-months/ |title=Concentrated Solar Power Dropped 50% in Six Months|access-date=31 October 2017}}</ref> |

|||

The DEWA project in Dubai, under construction in 2019, held the world record for lowest CSP price in 2017 at US$73 per MWh<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://analysis.newenergyupdate.com/csp-today/acwa-power-scales-tower-trough-design-set-record-low-csp-price|title=ACWA Power scales up tower-trough design to set record-low CSP price|date=September 20, 2017|website=New Energy Update / CSP Today|access-date=November 29, 2019}}</ref> for its 700 MW combined trough and tower project: 600 MW of trough, 100 MW of tower with 15 hours of thermal energy storage daily. |

|||

As a thermal energy generating power station, CSP has more in common with thermal power stations such as coal, gas, or geothermal. A CSP plant can incorporate [[thermal energy storage]], which stores energy either in the form of sensible heat or as latent heat (for example, using [[molten salt]]), which enables these plants to continue to generate electricity whenever it is needed, day or night. This makes CSP a [[Dispatchable generation|dispatchable]] form of solar. Dispatchable [[renewable energy]] is particularly valuable in places where there is already a high penetration of photovoltaics (PV), such as [[solar power in California|California]]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.solarpaces.org/chance-csp-california-outlaws-gas-fired-peaker-plants/ |title=New Chance for US CSP? California Outlaws Gas-Fired Peaker Plants|accessdate=23 February 2018}}</ref> because an evening peak is created as PV ramps down at sunset (a phenomenon referred to as [[duck curve]]).<ref>{{cite web |last1=Deign |first1=Jason |title=Concentrated Solar Power Quietly Makes a Comeback |url=https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/concentrated-solar-power-quietly-makes-a-comeback |website=www.greentechmedia.com |date=24 June 2019}}</ref> |

|||

Base-load CSP tariff in the extremely dry [[Atacama region]] of [[Chile]] reached below $50/MWh in 2017 auctions.<ref name="chile">{{cite web |url=http://www.solarpaces.org/solarreserve-bids-csp-5-cents-chilean-auction/ |title=SolarReserve Bids CSP Under 5 Cents in Chilean Auction|date=29 October 2017 |access-date=29 October 2017}}</ref><ref name="Kraemer">{{cite web|url=https://cleantechnica.com/2017/03/13/solarreserve-bids-24-hour-solar-6-3-cents-chile/|title=SolarReserve Bids 24-Hour Solar At 6.3 Cents In Chile|date=13 March 2017|publisher=CleanTechnica|access-date=14 March 2017}}</ref> |

|||

== History == |

|||

CSP is often compared to [[Growth of photovoltaics|photovoltaic]] solar (PV) since they both use solar energy. While solar PV experienced huge growth in recent years due to falling prices,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/as-concentrated-solar-power-bids-fall-to-record-lows-prices-seen-diverging-between-different-regions/ |title=As Concentrated Solar Power bids fall to record lows, prices seen diverging between different regions|accessdate=23 February 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.kcet.org/news/redefine/rewire/solar/concentrating-solar/are-solar-power-towers-doomed-in-california.html |title=Are Solar Power Towers Doomed in California? |author=Chris Clarke |work=KCET}}</ref> Solar CSP growth has been slow due to technical difficulties and high prices. In 2017, CSP represented less than 2% of worldwide installed capacity of solar electricity plants.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.ethz.ch/en/news-and-events/eth-news/news/2017/09/concentrating-solar-power.html |title=After the Desertec hype: is concentrating solar power still alive?|accessdate= 24 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:1901 solar motor.jpg|thumb|upright|Solar steam engine for water pumping, near Los Angeles circa 1901]] |

|||

However, CSP can more easily store energy during the night, making it more competitive with [[dispatchable generation|dispatchable generators]] and baseload plants.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.solarpaces.org/csp-competes-with-natural-gas-not-pv/|title=CSP Doesn't Compete With PV – it Competes with Gas|accessdate=4 March 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://cleantechnica.com/2019/06/04/concentrated-solar-power-costs-fell-46-from-2010-2018/ |title=Concentrated Solar Power Costs Fell 46% From 2010–2018|accessdate=3 June 2019}}</ref><ref name="dub">{{cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/uaes-push-on-concentrated-solar-power-should-open-eyes-across-world/ |title=UAE's push on concentrated solar power should open eyes across world|accessdate=29 October 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/concentrated-solar-power-dropped-50-in-six-months/ |title=Concentrated Solar Power Dropped 50% in Six Months|accessdate=31 October 2017}}</ref> |

|||

The DEWA project in Dubai, under construction in 2019, held the world record for lowest CSP price in 2017 at $73 per MWh<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://analysis.newenergyupdate.com/csp-today/acwa-power-scales-tower-trough-design-set-record-low-csp-price|title=ACWA Power scales up tower-trough design to set record-low CSP price|last=Reuters|date=September 20, 2017|website=New Energy Update / CSP Today|url-status=live|archive-url=|archive-date=|access-date=November 29, 2019}}</ref> for its 700 MW combined trough and tower project: 600 MW of trough, 100 MW of tower with 15 hours of thermal energy storage daily. |

|||

Base-load CSP tariff in the extremely dry [[Atacama region]] of [[Chile]] reached below ¢5.0/kWh in 2017 auctions.<ref name="chile">{{cite web |url=http://www.solarpaces.org/solarreserve-bids-csp-5-cents-chilean-auction/ |title=SolarReserve Bids CSP Under 5 Cents in Chilean Auction|accessdate=29 October 2017}}</ref><ref name=Kraemer /> |

|||

== History == |

|||

[[File:1901 solar motor.jpg|thumb|Solar steam engine for water pumping, near Los Angeles circa 1901]] |

|||

A legend has it that [[Archimedes]] used a "burning glass" to concentrate sunlight on the invading Roman fleet and repel them from [[Syracuse, Sicily#Greek period|Syracuse]]. In 1973 a Greek scientist, Dr. Ioannis Sakkas, curious about whether Archimedes could really have destroyed the Roman fleet in 212 BC, lined up nearly 60 Greek sailors, each holding an oblong mirror tipped to catch the sun's rays and direct them at a tar-covered plywood silhouette {{convert|160|ft|m|abbr=on|order=flip}} away. The ship caught fire after a few minutes; however, historians continue to doubt the Archimedes story.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Thomas W. Africa |jstor=4348211 |title=Archimedes through the Looking Glass |date=1975 |journal=The Classical World |volume=68 |issue=5 |pages=305–308 |doi=10.2307/4348211}}</ref> |

A legend has it that [[Archimedes]] used a "burning glass" to concentrate sunlight on the invading Roman fleet and repel them from [[Syracuse, Sicily#Greek period|Syracuse]]. In 1973 a Greek scientist, Dr. Ioannis Sakkas, curious about whether Archimedes could really have destroyed the Roman fleet in 212 BC, lined up nearly 60 Greek sailors, each holding an oblong mirror tipped to catch the sun's rays and direct them at a tar-covered plywood silhouette {{convert|160|ft|m|abbr=on|order=flip}} away. The ship caught fire after a few minutes; however, historians continue to doubt the Archimedes story.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Thomas W. Africa |jstor=4348211 |title=Archimedes through the Looking Glass |date=1975 |journal=The Classical World |volume=68 |issue=5 |pages=305–308 |doi=10.2307/4348211}}</ref> |

||

In 1866, [[Auguste Mouchout]] used a parabolic trough to produce steam for the first solar steam engine. The first patent for a solar collector was obtained by the Italian Alessandro Battaglia in Genoa, Italy, in 1886. Over the following years, invеntors such as [[John Ericsson]] and [[Frank Shuman]] developed concentrating solar-powered dеvices for irrigation, refrigеration, and locomоtion. In 1913 Shuman finished a {{convert|55|hp|kW}} parabolic [[solar thermal energy]] station in Maadi, Egypt for irrigation.<ref>Ken Butti, John Perlin (1980) ''A Golden Thread: 2500 Years of Solar Architecture and Technology'', Cheshire Books, pp. 66–100, {{ISBN|0442240058}}.</ref><ref>{{cite web|first=CM|last=Meyer|url=http://eepublishers.co.za/article/from-troughs-to-triumph-segs-and-gas.html|title=From |

In 1866, [[Auguste Mouchout]] used a parabolic trough to produce steam for the first solar steam engine. The first patent for a solar collector was obtained by the Italian Alessandro Battaglia in Genoa, Italy, in 1886. Over the following years, invеntors such as [[John Ericsson]] and [[Frank Shuman]] developed concentrating solar-powered dеvices for irrigation, refrigеration, and locomоtion. In 1913 Shuman finished a {{convert|55|hp|kW}} parabolic [[solar thermal energy]] station in Maadi, Egypt for irrigation.<ref>Ken Butti, John Perlin (1980) ''A Golden Thread: 2500 Years of Solar Architecture and Technology'', Cheshire Books, pp. 66–100, {{ISBN|0442240058}}.</ref><ref>{{cite web |first=CM |last=Meyer |url=http://eepublishers.co.za/article/from-troughs-to-triumph-segs-and-gas.html |title=From Troughs to Triumph: SEGS and Gas |website=EEPublishers.co.za |access-date=22 April 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110807122351/http://eepublishers.co.za/article/from-troughs-to-triumph-segs-and-gas.html |archive-date=7 August 2011 }}</ref><ref>Cutler J. Cleveland (23 August 2008). [http://www.eoearth.org/article/Shuman,_Frank Shuman, Frank]. Encyclopedia of Earth.</ref><ref>Paul Collins (Spring 2002) [http://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/6/beautifulpossibility.php The Beautiful Possibility]. Cabinet Magazine, Issue 6.</ref> The first solar-power system using a mirror dish was built by [[Robert H. Goddard|Dr. R.H. Goddard]], who was already well known for his research on liquid-fueled rockets and wrote an article in 1929 in which he asserted that all the previous obstacles had been addressed.<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=FSgDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA22 "A New Invention To Harness The Sun"] ''Popular Science'', November 1929</ref> |

||

Professor Giovanni Francia (1911–1980) designed and built the first concentrated-solar plant, which entered into operation in Sant'Ilario, near Genoa, Italy in 1968. This plant had the architecture of today's power tower plants with a solar receiver in the center of a field of solar collectors. The plant was able to produce 1 MW with superheated steam at 100 bar and 500 °C.<ref>Ken Butti, John Perlin (1980) ''A Golden Thread: 2500 Years of Solar Architecture and Technology'', Cheshire Books, p. 68, {{ISBN|0442240058}}.</ref> The 10 MW [[The Solar Project|Solar One]] power tower was developed in Southern California in 1981. [[The Solar Project#Solar One|Solar One]] was converted into [[The Solar Project#Solar Two|Solar Two]] in 1995, implementing a new design with a molten salt mixture (60% sodium nitrate, 40% potassium nitrate) as the receiver working fluid and as a storage medium. The molten salt approach proved effective, and Solar Two operated successfully until it was decommissioned in 1999.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://large.stanford.edu/courses/2015/ph240/dodaro2/|title=Molten Salt Storage|website=large.stanford.edu|access-date=2019-03-31}}</ref> The parabolic-trough technology of the nearby [[Solar Energy Generating Systems]] (SEGS), begun in 1984, was more workable. The 354 MW SEGS was the largest solar power plant in the world |

Professor Giovanni Francia (1911–1980) designed and built the first concentrated-solar plant, which entered into operation in Sant'Ilario, near Genoa, Italy in 1968. This plant had the architecture of today's power tower plants, with a solar receiver in the center of a field of solar collectors. The plant was able to produce 1 MW with superheated steam at 100 bar and 500 °C.<ref>Ken Butti, John Perlin (1980) ''A Golden Thread: 2500 Years of Solar Architecture and Technology'', Cheshire Books, p. 68, {{ISBN|0442240058}}.</ref> The 10 MW [[The Solar Project|Solar One]] power tower was developed in Southern California in 1981. [[The Solar Project#Solar One|Solar One]] was converted into [[The Solar Project#Solar Two|Solar Two]] in 1995, implementing a new design with a molten salt mixture (60% sodium nitrate, 40% potassium nitrate) as the receiver working fluid and as a storage medium. The molten salt approach proved effective, and Solar Two operated successfully until it was decommissioned in 1999.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://large.stanford.edu/courses/2015/ph240/dodaro2/|title=Molten Salt Storage|website=large.stanford.edu|access-date=2019-03-31}}</ref> The parabolic-trough technology of the nearby [[Solar Energy Generating Systems]] (SEGS), begun in 1984, was more workable. The 354 MW SEGS was the largest solar power plant in the world until 2014. |

||

No commercial concentrated solar was constructed from 1990 when SEGS was completed until 2006 when the [[Compact linear Fresnel reflector]] system at Liddell Power Station in Australia was built. Few other plants were built with this design although the 5 MW [[Kimberlina Solar Thermal Energy Plant]] opened in 2009. |

No commercial concentrated solar was constructed from 1990, when SEGS was completed, until 2006, when the [[Compact linear Fresnel reflector]] system at Liddell Power Station in Australia was built. Few other plants were built with this design, although the 5 MW [[Kimberlina Solar Thermal Energy Plant]] opened in 2009. |

||

In 2007, 75 MW Nevada Solar One was built, a trough design and the first large plant since SEGS. Between |

In 2007, 75 MW Nevada Solar One was built, a trough design and the first large plant since SEGS. Between 2010 and 2013, Spain built over 40 parabolic trough systems, size constrained at no more than 50 MW by the support scheme. Where not bound in other countries, the manufacturers have adopted up to 200 MW size for a single unit,<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.solarpaces.org/power-china-has-begun-construction-of-the-worlds-only-200mw-tower-csp/ |title=Power China has begun construction of the world's only 200MW Tower CSP |date=22 March 2024 | website=www.solarpaces.org |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240322023607/https://www.solarpaces.org/power-china-has-begun-construction-of-the-worlds-only-200mw-tower-csp/ |archive-date=22 March 2024 |access-date=27 October 2024}}</ref> with a cost soft point around 125 MW for a single unit. |

||

Due to the success of Solar Two, a commercial power plant, called [[Gemasolar Thermosolar Plant|Solar Tres Power Tower]], was built in Spain in 2011, later renamed Gemasolar Thermosolar Plant. Gemasolar's results paved the way for further plants of its type. [[Ivanpah Solar Power Facility]] was constructed at the same time but without thermal storage, using natural gas to preheat water each morning. |

Due to the success of Solar Two, a commercial power plant, called [[Gemasolar Thermosolar Plant|Solar Tres Power Tower]], was built in Spain in 2011, later renamed Gemasolar Thermosolar Plant. Gemasolar's results paved the way for further plants of its type. [[Ivanpah Solar Power Facility]] was constructed at the same time but without thermal storage, using natural gas to preheat water each morning. |

||

| Line 40: | Line 35: | ||

Most concentrated solar power plants use the parabolic trough design, instead of the power tower or Fresnel systems. There have also been variations of parabolic trough systems like the [[Combined cycle#Integrated solar combined cycle (ISCC)|integrated solar combined cycle (ISCC)]] which combines troughs and conventional fossil fuel heat systems. |

Most concentrated solar power plants use the parabolic trough design, instead of the power tower or Fresnel systems. There have also been variations of parabolic trough systems like the [[Combined cycle#Integrated solar combined cycle (ISCC)|integrated solar combined cycle (ISCC)]] which combines troughs and conventional fossil fuel heat systems. |

||

CSP was originally treated as a competitor to photovoltaics, and Ivanpah was built without energy storage, although Solar Two |

CSP was originally treated as a competitor to photovoltaics, and Ivanpah was built without energy storage, although Solar Two included several hours of thermal storage. By 2015, prices for photovoltaic plants had fallen and PV commercial power was selling for {{frac|1|3}} of contemporary CSP contracts.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://ww2.kqed.org/news/2015/12/15/nrg-ivanpah-faces-chance-of-default-PGE-contract|title=Ivanpah Solar Project Faces Risk of Default on PG&E Contracts|work=KQED News|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160325144752/http://ww2.kqed.org/news/2015/12/15/nrg-ivanpah-faces-chance-of-default-PGE-contract|archive-date=25 March 2016}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://guntherportfolio.com/2013/04/esolar-sierra-suntower-a-history-of-concentrating-solar-power-underperformance/|title=eSolar Sierra SunTower: a History of Concentrating Solar Power Underperformance | Gunther Portfolio|website=guntherportfolio.com|date=5 April 2013 }}</ref> However, increasingly, CSP was being bid with 3 to 12 hours of thermal energy storage, making CSP a dispatchable form of solar energy.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/why-concentrating-solar-power-needs-storage-to-survive#gs.zD6uAiA|title=Why Concentrating Solar Power Needs Storage to Survive|access-date=21 November 2017}}</ref> As such, it is increasingly seen as competing with natural gas and PV with batteries for flexible, dispatchable power. |

||

== Current technology == |

== Current technology == |

||

CSP is used to produce electricity (sometimes called solar thermoelectricity, usually generated through [[steam]]). Concentrated |

CSP is used to produce electricity (sometimes called solar thermoelectricity, usually generated through [[steam]]). Concentrated solar technology systems use [[mirror]]s or [[lens (optics)|lens]]es with [[Optical motion tracking|tracking]] systems to focus a large area of sunlight onto a small area. The concentrated light is then used as heat or as a heat source for a conventional [[power plant]] (solar thermoelectricity). The solar concentrators used in CSP systems can often also be used to provide industrial process heating or cooling, such as in [[solar air conditioning]]. |

||

Concentrating technologies exist in four optical types, namely [[parabolic trough]], [[dish Stirling|dish]], [[Compact Linear Fresnel Reflector|concentrating linear Fresnel reflector]], and [[solar power tower]].<ref name=tomkonrad>[http://tomkonrad.wordpress.com/2006/12/07/they-do-it-with-mirrors-concentrating-solar-power/ Types of solar thermal CSP plants]. Tomkonrad.wordpress.com. Retrieved on 22 April 2013.</ref> Parabolic trough and concentrating linear Fresnel reflectors are classified as linear focus collector types, dish and solar tower |

Concentrating technologies exist in four optical types, namely [[parabolic trough]], [[dish Stirling|dish]], [[Compact Linear Fresnel Reflector|concentrating linear Fresnel reflector]], and [[solar power tower]].<ref name=tomkonrad>[http://tomkonrad.wordpress.com/2006/12/07/they-do-it-with-mirrors-concentrating-solar-power/ Types of solar thermal CSP plants]. Tomkonrad.wordpress.com. Retrieved on 22 April 2013.</ref> Parabolic trough and concentrating linear Fresnel reflectors are classified as linear focus collector types, while dish and solar tower are point focus types. Linear focus collectors achieve medium concentration factors (50 suns and over), and point focus collectors achieve high concentration factors (over 500 suns). Although simple, these solar concentrators are quite far from the theoretical maximum concentration.<ref name="IntroNio2e">{{cite book |first=Julio |last=Chaves |title=Introduction to Nonimaging Optics, Second Edition |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=e11ECgAAQBAJ |publisher=[[CRC Press]] |year=2015 |isbn=978-1482206739}}</ref><ref name="NIO">Roland Winston, Juan C. Miñano, Pablo G. Benitez (2004) ''Nonimaging Optics'', Academic Press, {{ISBN|978-0127597515}}.</ref> For example, the parabolic-trough concentration gives about {{frac|1|3}} of the theoretical maximum for the design [[Acceptance angle (solar concentrator)|acceptance angle]], that is, for the same overall tolerances for the system. Approaching the theoretical maximum may be achieved by using more elaborate concentrators based on [[nonimaging optics]].<ref name="IntroNio2e"/><ref name="NIO"/><ref>{{cite book |last=Norton |first=Brian |title=Harnessing Solar Heat |date=2013 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-94-007-7275-5}}</ref> |

||

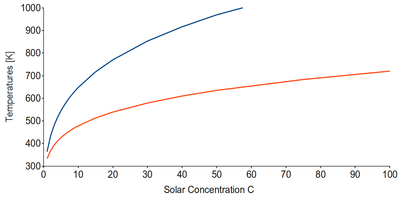

Different types of concentrators produce different peak temperatures and correspondingly varying thermodynamic efficiencies |

Different types of concentrators produce different peak temperatures and correspondingly varying thermodynamic efficiencies due to differences in the way that they track the sun and focus light. New innovations in CSP technology are leading systems to become more and more cost-effective.<ref>[http://www.popularmechanics.com/science/research/4288743.html?page=1 New innovations in solar thermal] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090421165638/http://www.popularmechanics.com/science/research/4288743.html?page=1 |date=21 April 2009 }}. Popularmechanics.com (1 November 2008). Retrieved on 22 April 2013.</ref><ref name="Yogender Pal Chandra">{{cite journal|last1=Chandra|first1=Yogender Pal|title=Numerical optimization and convective thermal loss analysis of improved solar parabolic trough collector receiver system with one sided thermal insulation|journal=Solar Energy |date=17 April 2017|volume=148|pages=36–48|doi=10.1016/j.solener.2017.02.051|bibcode=2017SoEn..148...36C}}</ref> |

||

In 2023, Australia’s national science agency [[CSIRO]] tested a CSP arrangement in which tiny ceramic particles fall through the beam of concentrated solar energy, the ceramic particles capable of storing a greater amount of heat than molten salt, while not requiring a container that would diminish heat transfer.<ref name=Freethink_20231112>{{cite news |last1=Houser |first1=Kristin |title=Aussie scientists hit milestone in concentrated solar power They heated ceramic particles to a blistering 1450 F by dropping them through a beam of concentrated sunlight. |url=https://www.freethink.com/energy/concentrated-solar-power-ceramic-particles |work=Freethink |date=12 November 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231115055619/https://www.freethink.com/energy/concentrated-solar-power-ceramic-particles |archive-date=15 November 2023 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

=== Parabolic trough === |

=== Parabolic trough === |

||

{{Main|Parabolic trough}} |

|||

[[File:Parabolic trough at Harper Lake in California.jpg|thumb|right|Parabolic trough at a plant near Harper Lake, California]] |

[[File:Parabolic trough at Harper Lake in California.jpg|thumb|right|Parabolic trough at a plant near Harper Lake, California]] |

||

[[File:Linear Parabolic Reflector Diagram (Concentrated Solar Power).svg|thumb|Diagram of linear parabolic reflector concentrating sun rays to heat working fluid]] |

|||

{{Main|Parabolic trough}} |

|||

A parabolic trough consists of a linear parabolic reflector that concentrates light onto a receiver positioned along the reflector's focal line. The receiver is a tube positioned at the longitudinal focal line of the parabolic mirror and filled with a working fluid. The reflector follows the sun during the daylight hours by tracking along a single axis. A [[working fluid]] (e.g. [[molten salt]]<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Vignarooban |first1=K. |last2=Xinhai |first2=Xu |year=2015 |title=Heat transfer fluids for concentrating solar power systems – A review |journal=Applied Energy |volume= 146|pages= 383–396|doi=10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.01.125|bibcode=2015ApEn..146..383V }}</ref>) is heated to {{convert|150|–|350|C|F}} as it flows through the receiver and is then used as a heat source for a power generation system.<ref name="Martin 2005">{{cite book |author1=Christopher L. Martin |author2=D. Yogi Goswami |title=Solar energy pocket reference |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tIFUAAAAMAAJ |date=2005 |publisher=Earthscan |isbn=978-1-84407-306-1 |page=45}}</ref> Trough systems are the most developed CSP technology. The [[Solar Energy Generating Systems]] (SEGS) plants in California, some of the longest-running in the world until their 2021 closure;<ref name=":1">{{Cite web |title=Solar thermal power plants - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) |url=https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/solar/solar-thermal-power-plants.php |access-date=2024-10-22 |website=www.eia.gov}}</ref> Acciona's [[Nevada Solar One]] near [[Boulder City, Nevada]];<ref name=":1" /> and [[Andasol]], Europe's first commercial parabolic trough plant are representative,<ref>{{Cite news |title=Earthprints: Andasol solar power station |url=https://widerimage.reuters.com/story/earthprints-andasol-solar-power-station |access-date=2024-10-22 |work=Reuters |language=en}}</ref> along with [[Plataforma Solar de Almería]]'s SSPS-DCS test facilities in [[Solar power in Spain|Spain]].<ref name="Plataforma">{{cite web |title=Linear-focusing Concentrator Facilities: DCS, DISS, EUROTROUGH and LS3 |publisher=Plataforma Solar de Almería |url=http://www.psa.es/webeng/instalaciones/parabolicos.html |access-date=29 September 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070928042703/http://www.psa.es/webeng/instalaciones/parabolicos.html |archive-date=28 September 2007}}</ref> |

|||

A parabolic trough consists of a linear parabolic reflector that concentrates light onto a receiver positioned along the reflector's focal line. The receiver is a tube positioned at the longitudinal focal line of the parabolic mirror and filled with a working fluid. The reflector follows the sun during the daylight hours by tracking along a single axis. A [[working fluid]] (e.g. [[molten salt]]<ref>{{cite journal |last=Vignarooban |first=K. |last2=Xinhai |first2=Xu |year=2015 |title=Heat transfer fluids for concentrating solar power systems – A review |journal=Applied Energy |volume= 146|pages= 383–396|doi=10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.01.125}}</ref>) is heated to {{convert|150|–|350|C|F}} as it flows through the receiver and is then used as a heat source for a power generation system.<ref name="Martin 2005">{{cite book |author1=Christopher L. Martin |author2=D. Yogi Goswami |title=Solar energy pocket reference |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tIFUAAAAMAAJ |date=2005 |publisher=Earthscan |isbn=978-1-84407-306-1 |page=45}}</ref> Trough systems are the most developed CSP technology. The [[Solar Energy Generating Systems]] (SEGS) plants in California, the world's first commercial parabolic trough plants, Acciona's [[Nevada Solar One]] near [[Boulder City, Nevada]], and [[Andasol]], Europe's first commercial parabolic trough plant are representative, along with [[Plataforma Solar de Almería]]'s SSPS-DCS test facilities in [[Solar power in Spain|Spain]].<ref name="Plataforma">{{cite web |title=Linear-focusing Concentrator Facilities: DCS, DISS, EUROTROUGH and LS3 |publisher=Plataforma Solar de Almería |url=http://www.psa.es/webeng/instalaciones/parabolicos.html |accessdate=29 September 2007 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20070928042703/http://www.psa.es/webeng/instalaciones/parabolicos.html |archivedate=28 September 2007}}</ref> |

|||

==== Enclosed trough ==== |

==== Enclosed trough ==== |

||

The design encapsulates the solar thermal system within a greenhouse-like glasshouse. The glasshouse creates a protected environment to withstand the elements that can negatively impact reliability and efficiency of the solar thermal system.<ref name="deloitte">Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Ltd, [http://www.deloitte.com/energypredictions2012 "Energy & Resources Predictions 2012"], 2 November 2011</ref> Lightweight curved solar-reflecting mirrors are suspended from the ceiling of the glasshouse by wires. A [[Solar tracker|single-axis tracking system]] positions the mirrors to retrieve the optimal amount of sunlight. The mirrors concentrate the sunlight and focus it on a network of stationary steel pipes, also suspended from the glasshouse structure.<ref>Helman, [https://www.forbes.com/forbes/2011/0425/features-glasspoint-greenhouses-green-energy-oil-from-sun.html "Oil from the sun"], "Forbes", 25 April 2011</ref> Water is carried throughout the length of the pipe, which is boiled to generate steam when intense solar radiation is applied. Sheltering the mirrors from the wind allows them to achieve higher temperature rates and prevents dust from building up on the mirrors.<ref name="deloitte"/> |

The design encapsulates the solar thermal system within a greenhouse-like glasshouse. The glasshouse creates a protected environment to withstand the elements that can negatively impact reliability and efficiency of the solar thermal system.<ref name="deloitte">Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Ltd, [http://www.deloitte.com/energypredictions2012 "Energy & Resources Predictions 2012"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130106174132/http://www.deloitte.com/energypredictions2012 |date=6 January 2013 }}, 2 November 2011</ref> Lightweight curved solar-reflecting mirrors are suspended from the ceiling of the glasshouse by wires. A [[Solar tracker|single-axis tracking system]] positions the mirrors to retrieve the optimal amount of sunlight. The mirrors concentrate the sunlight and focus it on a network of stationary steel pipes, also suspended from the glasshouse structure.<ref>Helman, [https://www.forbes.com/forbes/2011/0425/features-glasspoint-greenhouses-green-energy-oil-from-sun.html "Oil from the sun"], "Forbes", 25 April 2011</ref> Water is carried throughout the length of the pipe, which is boiled to generate steam when intense solar radiation is applied. Sheltering the mirrors from the wind allows them to achieve higher temperature rates and prevents dust from building up on the mirrors.<ref name="deloitte"/> |

||

[[GlassPoint Solar]], the company that created the Enclosed Trough design, states its technology can produce heat for [[Enhanced Oil Recovery]] (EOR) for about $5 per {{convert|1000000|BTU|kWh|abbr=on|order=flip}} in sunny regions, compared to between $10 and $12 for other conventional solar thermal technologies.<ref name="ehren chevron">Goossens, Ehren, [https://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-10-03/chevron-using-solar-thermal-steam-at-enhanced-oil-recovery-plant.html "Chevron Uses Solar-Thermal Steam to Extract Oil in California"], "Bloomberg", 3 October 2011</ref> |

[[GlassPoint Solar]], the company that created the Enclosed Trough design, states its technology can produce heat for [[Enhanced Oil Recovery]] (EOR) for about $5 per {{convert|1000000|BTU|kWh|abbr=on|order=flip}} in sunny regions, compared to between $10 and $12 for other conventional solar thermal technologies.<ref name="ehren chevron">Goossens, Ehren, [https://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-10-03/chevron-using-solar-thermal-steam-at-enhanced-oil-recovery-plant.html "Chevron Uses Solar-Thermal Steam to Extract Oil in California"], "Bloomberg", 3 October 2011</ref> |

||

| Line 62: | Line 59: | ||

=== Solar power tower === |

=== Solar power tower === |

||

{{Main|Solar power tower}} |

{{Main|Solar power tower}} |

||

[[File:Brigthsource Tower Ashalim.jpg|thumb|[[Ashalim Power Station]], Israel, on its completion the tallest solar tower in the world. It concentrates light from over 50,000 heliostats.]] |

[[File:Brigthsource Tower Ashalim.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Ashalim Power Station]], Israel, on its completion the tallest solar tower in the world. It concentrates light from over 50,000 heliostats.]] |

||

[[File:PS10 solar power tower.jpg|thumb|The [[PS10 solar power plant]] in [[Andalusia]], Spain |

[[File:PS10 solar power tower.jpg|thumb|The [[PS10 solar power plant]] in [[Andalusia]], Spain concentrates sunlight from a field of [[heliostat]]s onto a central solar power tower.]] |

||

A solar power tower consists of an array of dual-axis tracking reflectors ([[heliostat]]s) that concentrate sunlight on a central receiver atop a tower; the receiver contains a heat-transfer fluid, which can consist of water-steam or [[molten salt]]. Optically a solar power tower is the same as a circular Fresnel reflector. The working fluid in the receiver is heated to 500–1000 °C ({{convert|773|-|1273|K|F|disp=or}}) and then used as a heat source for a power generation or energy storage system.<ref name="Martin 2005"/> An advantage of the solar tower is the reflectors can be adjusted instead of the whole tower. Power-tower development is less advanced than trough systems, but they offer higher efficiency and better energy storage capability. Beam down tower application is also feasible with heliostats to heat the working fluid.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/three-solar-modules-of-worlds-first-commercial-beam-down-tower-concentrated-solar-power-project-to-be-connected-to-grid/ |title=Three solar modules of world's first commercial beam-down tower Concentrated Solar Power project to be connected to grid |accessdate=18 August 2019 }}</ref> |

|||

A solar power tower consists of an array of dual-axis tracking reflectors ([[heliostat]]s) that concentrate sunlight on a central receiver atop a tower; the receiver contains a heat-transfer fluid, which can consist of water-steam or [[molten salt]]. Optically a solar power tower is the same as a circular Fresnel reflector. The working fluid in the receiver is heated to 500–1000 °C ({{convert|773|-|1273|K|F|disp=or}}) and then used as a heat source for a power generation or energy storage system.<ref name="Martin 2005"/> An advantage of the solar tower is the reflectors can be adjusted instead of the whole tower. Power-tower development is less advanced than trough systems, but they offer higher efficiency and better energy storage capability. Beam down tower application is also feasible with heliostats to heat the working fluid.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/three-solar-modules-of-worlds-first-commercial-beam-down-tower-concentrated-solar-power-project-to-be-connected-to-grid/ |title=Three solar modules of world's first commercial beam-down tower Concentrated Solar Power project to be connected to grid |access-date=18 August 2019 }}</ref> CSP with dual towers are also used to enhance the conversion efficiency by nearly 24%.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.world-energy.org/article/43580.html |title=World's First Dual-Tower Concentrated Solar Power Plant Boosts Efficiency by 24% |access-date=22 July 2022}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Solar Two]] in [[Daggett, California|Daggett]], California and the CESA-1 in [[Plataforma Solar de Almeria]] Almeria, Spain, are the most representative demonstration plants. The [[PS10 solar power tower|Planta Solar 10]] (PS10) in [[Sanlucar la Mayor]], Spain, is the first commercial utility-scale solar power tower in the world. The 377 MW [[Ivanpah Solar Power Facility]], located in the [[Mojave Desert]], is the largest CSP facility in the world, and uses three power towers.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.brightsourceenergy.com/ivanpah-solar-project|title=Ivanpah - World's Largest Solar Plant in California Desert|website=www.brightsourceenergy.com}}</ref> Ivanpah generated only 0.652 TWh (63%) of its energy from solar means, and the other 0.388 TWh (37%) was generated by burning [[natural gas]]. |

|||

<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.eia.gov/electricity/data/browser/#/plant/57073|title=Electricity Data Browser|website=www.eia.gov}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.eia.gov/electricity/data/browser/#/plant/57074|title=Electricity Data Browser|website=www.eia.gov}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.eia.gov/electricity/data/browser/#/plant/57075|title=Electricity Data Browser|website=www.eia.gov}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Solar Two]] in [[Daggett, California|Daggett]], California and the CESA-1 in [[Plataforma Solar de Almeria]] Almeria, Spain, are the most representative demonstration plants. The [[PS10 solar power tower|Planta Solar 10]] (PS10) in [[Sanlucar la Mayor]], Spain, is the first commercial utility-scale solar power tower in the world. The 377 MW [[Ivanpah Solar Power Facility]], located in the [[Mojave Desert]], was the largest CSP facility in the world, and uses three power towers.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.brightsourceenergy.com/ivanpah-solar-project|title=Ivanpah - World's Largest Solar Plant in California Desert|website=BrightSourceEnergy.com}}</ref> Ivanpah generated only 0.652 TWh (63%) of its energy from solar means, and the other 0.388 TWh (37%) was generated by burning [[natural gas]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.eia.gov/electricity/data/browser/#/plant/57073|title=Electricity Data Browser|website=EIA.gov}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.eia.gov/electricity/data/browser/#/plant/57074|title=Electricity Data Browser|website=EIA.gov}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.eia.gov/electricity/data/browser/#/plant/57075|title=Electricity Data Browser|website=EIA.gov}}</ref> |

|||

[[Supercritical carbon dioxide]] can be used instead of steam as heat-transfer fluid for increased [[Electricity generation|electricity production]] efficiency. However, because of the high temperatures in [[arid]] areas where solar power is usually located, it is impossible to cool down carbon dioxide below its [[Critical point (thermodynamics)|critical temperature]] in the [[compressor]] inlet. Therefore, [[supercritical carbon dioxide blend]]s with higher critical temperature are currently in development. |

|||

=== Fresnel reflectors === |

=== Fresnel reflectors === |

||

{{Main|Compact |

{{Main|Compact linear Fresnel reflector}} |

||

Fresnel reflectors are made of many thin, flat mirror strips to concentrate sunlight onto tubes through which working fluid is pumped. Flat mirrors allow more reflective surface in the same amount of space than a parabolic reflector, thus capturing more of the available sunlight, and they are much cheaper than parabolic reflectors. Fresnel reflectors can be used in various size CSPs.<ref>[http://www.physics.usyd.edu.au/app/research/solar/clfr.html Compact CLFR]. Physics.usyd.edu.au (12 June 2002). Retrieved on 22 April 2013.</ref><ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20110721150750/http://www.ese.iitb.ac.in/activities/solarpower/ausra.pdf Ausra's Compact Linear Fresnel Reflector (CLFR) and Lower Temperature Approach]. ese.iitb.ac.in</ref> |

|||

Fresnel reflectors are made of many thin, flat mirror strips to concentrate sunlight onto tubes through which working fluid is pumped. Flat mirrors allow more reflective surface in the same amount of space than a parabolic reflector, thus capturing more of the available sunlight, and they are much cheaper than parabolic reflectors.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Land-Use competitiveness of photovoltaic and concentrated solar power technologies near the Tropic of Cancer |date=September 2022|doi=10.1016/j.solener.2022.07.051 |last1=Marzouk |first1=Osama A. |journal=Solar Energy |volume=243 |pages=103–119 |bibcode=2022SoEn..243..103M |s2cid=251357374 |doi-access=free }}</ref> Fresnel reflectors can be used in various size CSPs.<ref>[http://www.physics.usyd.edu.au/app/research/solar/clfr.html Compact CLFR]. Physics.usyd.edu.au (12 June 2002). Retrieved on 22 April 2013.</ref><ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20110721150750/http://www.ese.iitb.ac.in/activities/solarpower/ausra.pdf Ausra's Compact Linear Fresnel Reflector (CLFR) and Lower Temperature Approach]. ese.iitb.ac.in</ref> |

|||

Fresnel reflectors are sometimes regarded as a technology with a worse output than other methods. The cost efficiency of this model is what causes some to use this instead of others with higher output ratings. Some new models of Fresnel Reflectors with Ray Tracing capabilities have begun to be tested and have initially proved to yield higher output than the standard version.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Abbas |first1=R. |last2=Muñoz-Antón |first2=J. |last3=Valdés |first3=M. |last4=Martínez-Val |first4=J.M. |title=High concentration linear Fresnel reflectors |journal=Energy Conversion and Management |date=August 2013 |volume=72 |pages=60–68 |doi=10.1016/j.enconman.2013.01.039}}</ref> |

|||

Fresnel reflectors are sometimes regarded as a technology with a worse output than other methods. The cost efficiency of this model is what causes some to use this instead of others with higher output ratings. Some new models of Fresnel reflectors with Ray Tracing capabilities have begun to be tested and have initially proved to yield higher output than the standard version.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Abbas |first1=R. |last2=Muñoz-Antón |first2=J. |last3=Valdés |first3=M. |last4=Martínez-Val |first4=J.M. |title=High concentration linear Fresnel reflectors |journal=Energy Conversion and Management |date=August 2013 |volume=72 |pages=60–68 |doi=10.1016/j.enconman.2013.01.039|bibcode=2013ECM....72...60A }}</ref> |

|||

=== Dish Stirling === |

=== Dish Stirling === |

||

{{see also|Solar thermal energy#Dish designs}} |

|||

[[File:SolarStirlingEngine.jpg|thumb|[[Solar thermal energy#Dish designs|A dish Stirling]] ]] |

[[File:SolarStirlingEngine.jpg|thumb|[[Solar thermal energy#Dish designs|A dish Stirling]] ]] |

||

{{Main|Dish Stirling}} |

|||

A dish Stirling or dish engine system consists of a stand-alone [[parabolic reflector]] that concentrates light onto a receiver positioned at the reflector's focal point. The reflector tracks the Sun along two axes. The working fluid in the receiver is heated to {{convert|250|–|700|C|F}} and then used by a [[Stirling engine]] to generate power.<ref name="Martin 2005"/> Parabolic-dish systems provide high solar-to-electric efficiency (between 31% and 32%), and their modular nature provides scalability. The [[Stirling Energy Systems]] (SES), [[United Sun Systems International|United Sun Systems]] (USS) and [[Science Applications International Corporation|Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC)]] dishes at [[University of Nevada, Las Vegas|UNLV]], and [[Australian National University]]'s [[The Big Dish (solar thermal)|Big Dish]] in [[Canberra]], Australia are representative of this technology. A world record for solar to electric efficiency was set at 31.25% by SES dishes at the [[National Solar Thermal Test Facility]] (NSTTF) in New Mexico on 31 January 2008, a cold, bright day.<ref>[https:// |

A dish Stirling or dish engine system consists of a stand-alone [[parabolic reflector]] that concentrates light onto a receiver positioned at the reflector's focal point. The reflector tracks the Sun along two axes. The working fluid in the receiver is heated to {{convert|250|–|700|C|F}} and then used by a [[Stirling engine]] to generate power.<ref name="Martin 2005"/> Parabolic-dish systems provide high solar-to-electric efficiency (between 31% and 32%), and their modular nature provides scalability. The [[Stirling Energy Systems]] (SES), [[United Sun Systems International|United Sun Systems]] (USS) and [[Science Applications International Corporation|Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC)]] dishes at [[University of Nevada, Las Vegas|UNLV]], and [[Australian National University]]'s [[The Big Dish (solar thermal)|Big Dish]] in [[Canberra]], Australia are representative of this technology. A world record for solar to electric efficiency was set at 31.25% by SES dishes at the [[National Solar Thermal Test Facility]] (NSTTF) in New Mexico on 31 January 2008, a cold, bright day.<ref>[https://newsreleases.sandia.gov/releases/2008/solargrid.html Sandia, Stirling Energy Systems set new world record for solar-to-grid conversion efficiency], Sandia, Feb. 12, 2008. Retrieved on 21 October 2021.{{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130219193847/https://share.sandia.gov/news/resources/releases/2008/solargrid.html |date=19 February 2013 }}.</ref> According to its developer, Ripasso Energy, a Swedish firm, in 2015 its dish Stirling system tested in the [[Kalahari Desert]] in South Africa showed 34% efficiency.<ref name="Guardian51315">{{cite news |first=Jeffrey |last=Barbee |title=Could this be the world's most efficient solar electricity system? |url=https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/may/13/could-this-be-the-worlds-most-efficient-solar-electricity-system |access-date=21 April 2017 |work=The Guardian |date=13 May 2015 |quote=34% of the sun's energy hitting the mirrors is converted directly to grid-available electric power}}</ref> The SES installation in Maricopa, Phoenix, was the largest Stirling Dish power installation in the world until it was sold to [[United Sun Systems International|United Sun Systems]]. Subsequently, larger parts of the installation have been moved to China to satisfy part of the large energy demand. |

||

== Solar thermal enhanced oil recovery == |

|||

{{Main|Solar thermal enhanced oil recovery}} |

|||

Heat from the sun can be used to provide steam used to make heavy oil less viscous and easier to pump. Solar power tower and parabolic troughs can be used to provide the steam which is used directly so no generators are required and no electricity is produced. Solar thermal enhanced oil recovery can extend the life of oilfields with very thick oil which would not otherwise be economical to pump.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/csp-eor-developer-cuts-costs-on-1-gw-oman-concentrated-solar-power-project/ |title=CSP EOR developer cuts costs on 1 GW Oman Concentrated Solar Power project|accessdate= 24 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

== CSP with thermal energy storage == |

== CSP with thermal energy storage == |

||

{{See also|Thermal energy storage|Solar thermal energy}} |

{{See also|Thermal energy storage|Solar thermal energy}} |

||

In a CSP plant that includes storage, the solar energy is first used to heat the molten salt or synthetic oil which is stored providing thermal/heat energy at high temperature in insulated tanks.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.solarpaces.org/how-csp-thermal-energy-storage-works/|title=How CSP's Thermal Energy Storage Works - SolarPACES|date=10 September 2017|work=SolarPACES|accessdate=21 November 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.solarreserve.com/en/technology/molten-salt-energy-storage|title=Molten salt energy storage|accessdate=22 August 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170829132011/http://www.solarreserve.com/en/technology/molten-salt-energy-storage|archive-date=29 August 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref> Later the hot molten salt (or oil) is used in a steam generator to produce steam to generate electricity by steam [[turbo generator]] as per requirement.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.powermag.com/the-latest-in-thermal-energy-storage/|title=The Latest in Thermal Energy Storage |accessdate= 22 August 2017}}</ref> Thus solar energy which is available in daylight only is used to generate electricity round the clock on demand as a [[load following power plant]] or solar peaker plant.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/is-csp-viable-without-storage#gs.9UN2YLg|title=Concentrating Solar Power Isn't Viable Without Storage, Say Experts |accessdate= 29 August 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.solarpaces.org/study-solar-peaker-compete-with-gas/|title=How Solar Peaker Plants Could Replace Gas Peakers |accessdate= 2 April 2018}}</ref> The thermal storage capacity is indicated in hours of power generation at [[nameplate capacity]]. Unlike [[photovoltaics|solar PV]] or CSP without storage, the power generation from solar thermal storage plants is [[ancillary services (electric power)|dispatchable and self-sustainable]] similar to coal/gas-fired power plants, but without the pollution.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://reneweconomy.com.au/aurora-what-you-should-know-about-port-augustas-solar-power-tower-86715/|title=Aurora: What you should know about Port Augusta's solar power-tower |accessdate= 22 August 2017}}</ref> CSP with thermal energy storage plants can also be used as [[cogeneration]] plants to supply both electricity and process steam round the clock. As of December 2018, CSP with thermal energy storage plants generation cost have ranged between 5 c € / kWh and 7 c € / kWh depending on good to medium solar radiation received at a location.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/2018-the-year-in-which-the-concentrated-solar-power-returned-to-shine/|title=2018, the year in which the Concentrated Solar Power returned to shine |accessdate= 18 December 2018}}</ref> Unlike solar PV plants, CSP with thermal energy storage plants can also be used economically round the clock to produce only process steam replacing pollution emitting [[fossil fuels]]. CSP plant can also be integrated with solar PV for better synergy.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.dlr.de/dlr/en/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-10081/151_read-34003/#/gallery/28711|title=Controllable solar power – competitively priced for the first time in North Africa |accessdate= 7 June 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.solarpaces.org/morocco-breaks-new-record-with-800-mw-midelt-1-csp-pv-at-7-cents/|title=Morocco Breaks New Record with 800 MW Midelt 1 CSP-PV at 7 Cents |accessdate= 7 June 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.solarpaces.org/morocco-pioneers-pv-with-thermal-storage-at-800-mw-midelt-csp-project/|title=Morocco Pioneers PV with Thermal Storage at 800 MW Midelt CSP Project |accessdate= 25 April 2020}}</ref> |

|||

In a CSP plant that includes storage, the solar energy is first used to heat molten salt or synthetic oil, which is stored providing thermal/heat energy at high temperature in insulated tanks.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.solarpaces.org/how-csp-thermal-energy-storage-works/|title=How CSP's Thermal Energy Storage Works - SolarPACES|date=10 September 2017|work=SolarPACES|access-date=21 November 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.solarreserve.com/en/technology/molten-salt-energy-storage|title=Molten salt energy storage|access-date=22 August 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170829132011/http://www.solarreserve.com/en/technology/molten-salt-energy-storage|archive-date=29 August 2017}}</ref> Later the hot molten salt (or oil) is used in a steam generator to produce steam to generate electricity by steam [[turbo generator]] as required.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.powermag.com/the-latest-in-thermal-energy-storage/|title=The Latest in Thermal Energy Storage |date=July 2017 |access-date= 22 August 2017}}</ref> Thus solar energy which is available in daylight only is used to generate electricity round the clock on demand as a [[load following power plant]] or solar peaker plant.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/is-csp-viable-without-storage#gs.9UN2YLg|title=Concentrating Solar Power Isn't Viable Without Storage, Say Experts |access-date= 29 August 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.solarpaces.org/study-solar-peaker-compete-with-gas/|title=How Solar Peaker Plants Could Replace Gas Peakers |date=19 October 2017 |access-date= 2 April 2018}}</ref> The thermal storage capacity is indicated in hours of power generation at [[nameplate capacity]]. Unlike [[photovoltaics|solar PV]] or CSP without storage, the power generation from solar thermal storage plants is [[ancillary services (electric power)|dispatchable and self-sustainable]], similar to coal/[[gas-fired power plant]]s, but without the pollution.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://reneweconomy.com.au/aurora-what-you-should-know-about-port-augustas-solar-power-tower-86715/|title=Aurora: What you should know about Port Augusta's solar power-tower |date=21 August 2017 |access-date= 22 August 2017}}</ref> CSP with thermal energy storage plants can also be used as [[cogeneration]] plants to supply both electricity and process steam round the clock. As of December 2018, CSP with thermal energy storage plants' generation costs have ranged between 5 c € / kWh and 7 c € / kWh, depending on good to medium solar radiation received at a location.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/2018-the-year-in-which-the-concentrated-solar-power-returned-to-shine/|title=2018, the year in which the Concentrated Solar Power returned to shine |access-date= 18 December 2018}}</ref> Unlike solar PV plants, CSP with thermal energy storage can also be used economically around the clock to produce process steam, replacing polluting [[fossil fuels]]. CSP plants can also be integrated with solar PV for better synergy.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.dlr.de/dlr/en/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-10081/151_read-34003/#/gallery/28711|title=Controllable solar power – competitively priced for the first time in North Africa |access-date= 7 June 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.solarpaces.org/morocco-breaks-new-record-with-800-mw-midelt-1-csp-pv-at-7-cents/|title=Morocco Breaks New Record with 800 MW Midelt 1 CSP-PV at 7 Cents |access-date= 7 June 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.solarpaces.org/morocco-pioneers-pv-with-thermal-storage-at-800-mw-midelt-csp-project/|title=Morocco Pioneers PV with Thermal Storage at 800 MW Midelt CSP Project |access-date= 25 April 2020}}</ref> |

|||

CSP with thermal storage systems are also available using [[Brayton cycle]] with air instead of steam for generating electricity and/or steam round the clock. These CSP plants are equipped with [[gas turbine]] to generate electricity.<ref name="helioscsp.com">{{cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/247solar-and-masen-ink-agreement-for-first-operational-next-generation-concentrated-solar-power-plant/|title=247Solar and Masen Ink Agreement for First Operational Next Generation Concentrated Solar Power Plant|accessdate= 31 August 2019}}</ref> These are also small in capacity (<0.4 MW) with flexibility to install in few acres area.<ref name="helioscsp.com"/> Waste heat from the power plant can also be used for process steam generation and [[HVAC]] needs.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/247solar-modular-scalable-concentrated-solar-power-tech-to-be-marketed-to-mining-by-rost/ |title=247Solar modular & scalable concentrated solar power tech to be marketed to mining by ROST|accessdate=31 October 2019 }}</ref> In case land availability is not a limitation, any number of these modules can be installed up to 1000 MW with [[RAMS]] and cost advantage since the per MW cost of these units are cheaper than bigger size solar thermal stations.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/capex-of-modular-concentrated-solar-power-plants-could-halve-if-1-gw-deployed/ |title=Capex of modular Concentrated Solar Power plants could halve if 1 GW deployed|accessdate=31 October 2019 }}</ref> |

|||

CSP with thermal storage systems are also available using [[Brayton cycle]] generators with air instead of steam for generating electricity and/or steam round the clock. These CSP plants are equipped with [[gas turbine|gas turbines]] to generate electricity.<ref name="helioscsp.com">{{cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/247solar-and-masen-ink-agreement-for-first-operational-next-generation-concentrated-solar-power-plant/|title=247Solar and Masen Ink Agreement for First Operational Next Generation Concentrated Solar Power Plant|access-date= 31 August 2019}}</ref> These are also small in capacity (<0.4 MW), with flexibility to install in few acres' area.<ref name="helioscsp.com"/> Waste heat from the power plant can also be used for process steam generation and [[HVAC]] needs.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/247solar-modular-scalable-concentrated-solar-power-tech-to-be-marketed-to-mining-by-rost/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191028184401/http://helioscsp.com/247solar-modular-scalable-concentrated-solar-power-tech-to-be-marketed-to-mining-by-rost/ |url-status=dead |archive-date=28 October 2019 |title=247 solar modular & scalable concentrated solar power tech to be marketed to mining by Rost|access-date=31 October 2019}}</ref> In case land availability is not a limitation, any number of these modules can be installed, up to 1000 MW with [[RAMS]] and cost advantages since the per MW costs of these units are lower than those of larger size solar thermal stations.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/capex-of-modular-concentrated-solar-power-plants-could-halve-if-1-gw-deployed/ |title=Capex of modular Concentrated Solar Power plants could halve if 1 GW deployed|access-date=31 October 2019 }}</ref> |

|||

Centralized district heating round the clock is also feasible with [[Solar thermal energy| |

Centralized district heating round the clock is also feasible with [[Solar thermal energy|concentrated solar thermal]] storage plants.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://helioscsp.com/tibets-first-solar-district-heating-plant/ |title=Tibet's first solar district heating plant|access-date=20 December 2019 }}</ref> |

||

== Deployment around the world == |

== Deployment around the world == |

||

| Line 99: | Line 95: | ||

<!-- bar-chart of worldwide CSP capacity --> |

<!-- bar-chart of worldwide CSP capacity --> |

||

{{Image frame |

{{Image frame |

||

|width = 260 |

| width = 260 |

||

|align=left |

| align=left |

||

|pos=bottom |

| pos=bottom |

||

|content=<div style="margin:15px 0 -45px -60px; font-size:80%;">{{ #invoke:Chart | bar-chart |

| content=<div style="margin:15px 0 -45px -60px; font-size:80%;">{{ #invoke:Chart | bar-chart |

||

| width = 320 |

| width = 320 |

||

| height = 350 |

| height = 350 |

||

| Line 111: | Line 107: | ||

| x legends = 1984 : : : : : : 1990: : : : : 1995 : : : : : 2000 : : : : : 2005 : : : : : 2010 : : : : : 2015 : : : : |

| x legends = 1984 : : : : : : 1990: : : : : 1995 : : : : : 2000 : : : : : 2005 : : : : : 2010 : : : : : 2015 : : : : |

||

}}</div> |

}}</div> |

||

|caption = '''Worldwide CSP capacity since 1984 in MW<sub>p</sub>''' |

| caption = '''Worldwide CSP capacity since 1984 in MW<sub>p</sub>''' |

||

}} |

}} |

||

{| class="wikitable sortable floatright" style="text-align: right;" |

{| class="wikitable sortable floatright" style="text-align: right;" |

||

|+National CSP capacities in |

|+ National CSP capacities in 2023 (MW<sub>p</sub>) |

||

|- |

|- |

||

! Country !! Total !! Added |

! Country !! Total !! Added |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align=left|[[Spain]] || 2, |

| align=left| [[Spain]] || 2,304 || 0 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align=left|[[United States]] || 1, |

| align=left| [[United States]] || 1,480 || 0 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align=left|[[South Africa]] || |

| align=left| [[South Africa]] || 500 || 0 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align=left|[[Morocco]] || |

| align=left| [[Morocco]] || 540 || 0 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align=left|[[India]] || |

| align=left| [[India]] || 343 || 0 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align=left|[[China]] || |

| align=left| [[China]] || 570 || 0 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align=left|[[United Arab Emirates]] || |

| align=left| [[United Arab Emirates]] || 600 || 300 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align=left|[[Saudi Arabia]] || 50 || |

| align=left| [[Saudi Arabia]] || 50 || 0 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align=left|[[Algeria]] || 25 || 0 |

| align=left| [[Algeria]] || 25 || 0 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align=left|[[Egypt]] || 20 || 0 |

| align=left| [[Egypt]] || 20 || 0 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align=left|[[ |

| align=left| [[Italy]] || 13 || 0 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align=left|[[ |

| align=left| [[Australia]] || 5 || 0 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align=left| [[Thailand]] || 5 || 0 |

|||

! colspan=3 style="font-size: 0.85em; text-align: left; padding: 6px 0 4px 2px; font-weight: normal;" | ''Source'': [[REN21]] Global Status Report, 2017 and 2018<ref name="ren21-gsr-2017">[http://www.ren21.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/170607_GSR_2017_Full_Report.pdf Renewables Global Status Report], REN21, 2017</ref><ref name=REN2018>[http://www.ren21.net/gsr-2018/chapters/chapter_03/chapter_03/#sub_6 Renewables 2017: Global Status Report], REN21, 2018</ref><ref name="HeliosCSP" /> |

|||

|- |

|||

| colspan=3 style="font-size: 0.85em; padding: 6px 0 4px 2px; text-align:left;" | ''Source'': [[REN21]] Global Status Report, 2017 and 2018<ref name=ire/><ref name="ren21-gsr-2017">[http://www.ren21.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/170607_GSR_2017_Full_Report.pdf Renewables Global Status Report], REN21, 2017</ref><ref name=REN2018>[http://www.ren21.net/gsr-2018/chapters/chapter_03/chapter_03/#sub_6 Renewables 2017: Global Status Report], REN21, 2018</ref><ref name="HeliosCSP">{{cite web |title=Concentrated Solar Power increasing cumulative global capacity more than 11% to just under 5.5 GW in 2018 |url=http://helioscsp.com/concentrated-solar-power-increasing-cumulative-global-capacity-more-than-11-to-just-under-5-5-gw-in-2018/ |access-date=18 June 2019}}</ref> |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

The |

An early plant operated in Sicily at [[Adrano]]. The US deployment of CSP plants started by 1984 with the [[Solar Energy Generating Systems|SEGS]] plants. The last SEGS plant was completed in 1990. From 1991 to 2005, no CSP plants were built anywhere in the world. Global installed CSP-capacity increased nearly tenfold between 2004 and 2013 and grew at an average of 50 percent per year during the last five of those years, as the number of countries with installed CSP was growing. <ref name="ren21-gsr-2014" />{{rp|51}} In 2013, worldwide installed capacity increased by 36% or nearly 0.9 [[gigawatt]] (GW) to more than 3.4 GW. The record for capacity installed was reached in 2014, corresponding to 925 MW; however, it was followed by a decline caused by policy changes, the global financial crisis, and the rapid decrease in price of the photovoltaic cells. Nevertheless, total capacity reached 6800 MW in 2021.<ref name="chinCSP">{{cite web |title=Blue Book of China's Concentrating Solar Power Industry, 2021 |url=https://www.solarpaces.org/wp-content/uploads/Blue-Book-on-Chinas-CSP-Industry-2021.pdf |access-date=16 June 2022}}</ref> |

||

[[Solar power in Spain|Spain]] accounted for almost one third of the world's capacity, at 2,300 MW, despite no new capacity entering commercial operation in the country since 2013.<ref name="HeliosCSP" /> |

|||

CSP is also increasingly competing with the cheaper [[photovoltaic]] solar power and with [[concentrator photovoltaics]] (CPV), a fast-growing technology that just like CSP is suited best for regions of high solar insolation.<ref>PV-insider.com [http://news.pv-insider.com/concentrated-pv/how-cpv-trumps-csp-high-dni-locations How CPV trumps CSP in high DNI locations] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141122062102/http://news.pv-insider.com/concentrated-pv/how-cpv-trumps-csp-high-dni-locations |date=22 November 2014 }}, 14 February 2012</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cleantechinvestor.com/portal/solarpowercomment/10440-cpv-an-oasis-in-the-csp-desert.html |title=CPV - an oasis in the CSP desert? |author=Margaret Schleifer |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150518092811/http://www.cleantechinvestor.com/portal/solarpowercomment/10440-cpv-an-oasis-in-the-csp-desert.html |archivedate=18 May 2015 }}</ref> In addition, a novel solar CPV/CSP hybrid system has been proposed recently.<ref>Phys.org [http://phys.org/news/2015-02-solar-cpvcsp-hybrid.html A novel solar CPV/CSP hybrid system proposed], 11 February 2015</ref> |

|||

The United States follows with 1,740 MW. Interest is also notable in North Africa and the Middle East, as well as China and India. There is a notable trend towards developing countries and regions with high solar radiation with several large plants under construction in 2017. |

|||