Clay: Difference between revisions

Too simple to suggest it is just the choice of clay |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{other uses}} |

|||

{{Short description|Fine grained natural soil}} |

|||

[[Image:Gay head cliffs MV.JPG|right|thumb|250px|The Gay Head cliffs in [[Martha's Vineyard]] are made almost entirely of clay.]] |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=May 2020}} |

|||

{{Use British English|date=March 2021}} |

|||

[[File:Gay head cliffs MV.JPG|thumb|[[Gay Head Cliffs]] in [[Martha's Vineyard]] consist almost entirely of clay.]] |

|||

[[File:Clay-ss-2005.jpg|thumb|A [[Quaternary]] clay deposit in [[Estonia]], laid down about 400,000 years ago]] |

|||

'''Clay''' is a type of fine-grained natural [[soil]] material containing [[clay mineral]]s{{sfn|Olive|Chleborad|Frahme|Shlocker|1989}} (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. [[kaolinite]], [[aluminium|Al]]<sub>2</sub>[[Silicon|Si]]<sub>2</sub>[[Oxygen|O]]<sub>5</sub>([[hydroxide|OH]])<sub>4</sub>). Most pure clay minerals are white or light-coloured, but natural clays show a variety of colours from impurities, such as a reddish or brownish colour from small amounts of [[iron oxide]].{{sfn|Klein|Hurlbut|1993|pp=512–514}}{{sfn|Nesse|2000|pp=252–257}} |

|||

Clays develop [[plasticity (physics)|plasticity]] when wet but can be hardened through [[Pottery#Firing|firing]].{{sfn|Guggenheim|Martin|1995|pp=255–256}}{{sfn|Science Learning Hub|2010}}{{sfn|Breuer|2012}} Clay is the longest-known [[ceramic]] material. Prehistoric humans discovered the useful properties of clay and used it for making [[pottery]]. Some of the earliest pottery shards have been [[radiocarbon dating|dated]] to around 14,000 BCE,{{sfn|Scarre|2005|p=238}} and [[Clay tablet|clay tablets]] were the first known writing medium.{{sfn|Ebert|2011|p=64}} Clay is used in many modern industrial processes, such as [[paper]] making, [[cement]] production, and chemical [[filtration|filtering]]. Between one-half and two-thirds of the world's population live or work in buildings made with clay, often baked into brick, as an essential part of its load-bearing structure. In agriculture, clay content is a major factor in determining land [[arable land|arability]]. Clay soils are generally less suitable for crops due to poor natural drainage, however clay soils are more fertile, due to higher [[cation-exchange capacity]].<ref name="v874">{{cite book | title=Lockhart and Wiseman' s Crop Husbandry Including Grassland | chapter=Soil health and management | publisher=Elsevier | date=2023 | isbn=978-0-323-85702-4 | doi=10.1016/b978-0-323-85702-4.00023-6 | page=49–79}}</ref><ref name="x742">{{cite web | title=Cation Exchange Capacity and Base Saturation | website=UGA Cooperative Extension | date=2014-02-26 | url=https://extension.uga.edu/publications/detail.html?number=C1040&title=cation-exchange-capacity-and-base-saturation | access-date=2025-01-08}}</ref> |

|||

'''Clay''' is a term used to describe a group of hydrous [[aluminium]] [[Silicate minerals#Phyllosilicates|phyllosilicate]] (phyllosilicates being a subgroup of [[silicate minerals]]) [[mineral]]s (see [[clay minerals]]), that are typically less than 2 μm ([[micrometre]]s) in [[diameter]]. Clay consists of a variety of phyllosilicate minerals rich in [[silicon]] and [[aluminium]] [[oxide]]s and [[hydroxide]]s which include variable amounts of structural [[Water (molecule)|water]]. Clays are generally formed by the chemical [[weathering]] of silicate-bearing rocks by [[carbonic acid]] but some are formed by [[hydrothermal]] activity. Clays are distinguished from other small particles present in [[soil]]s such as [[silt]] by their small size, flake or layered shape, affinity for water and tendency toward high plasticity. |

|||

Clay is a very common substance. [[Shale]], formed largely from clay, is the most common sedimentary rock.{{sfn|Boggs|2006|p=140}} Although many naturally occurring deposits include both silts and clay, clays are distinguished from other fine-grained soils by differences in size and mineralogy. [[Silt]]s, which are fine-grained soils that do not include clay minerals, tend to have larger particle sizes than clays. Mixtures of [[sand]], [[silt]] and less than 40% clay are called [[loam]]. Soils high in ''swelling clays'' ([[expansive clay]]), which are clay minerals that readily expand in volume when they absorb water, are a major challenge in [[civil engineering]].{{sfn|Olive|Chleborad|Frahme|Shlocker|1989}} |

|||

== Grouping == |

|||

Depending upon academic source, there are three or four main groups of clays: [[kaolin]]ite, [[montmorillonite]]-[[smectite]], [[illite]], and [[chlorite]] (the latter group is not always considered a part of the clays and is sometimes classified as a separate group within the [[phyllosilicate]]s). There are about thirty different types of 'pure' clays in these categories but most 'natural' clays are mixtures of these different types, along with other weathered minerals. |

|||

== Properties == |

|||

== Historical and modern uses of clay == |

|||

[[ |

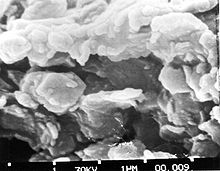

[[File:Clay magnified.jpg|thumb|A 23,500 times magnified electron micrograph of [[smectite]] clay]] |

||

The defining mechanical property of clay is its plasticity when wet and its ability to harden when dried or fired. Clays show a broad range of water content within which they are highly plastic, from a minimum water content (called the [[Atterberg limits|plastic limit]]) where the clay is just moist enough to mould, to a maximum water content (called the liquid limit) where the moulded clay is just dry enough to hold its shape.{{sfn|Moreno-Maroto|Alonso-Azcárate|2018}} The plastic limit of kaolinite clay ranges from about 36% to 40% and its liquid limit ranges from about 58% to 72%.{{sfn|White|1949}} High-quality clay is also tough, as measured by the amount of mechanical work required to roll a sample of clay flat. Its toughness reflects a high degree of internal cohesion.{{sfn|Moreno-Maroto|Alonso-Azcárate|2018}} |

|||

Clay is plastic when wet, which means it can be easily shaped. When dry, it becomes firm and when subject to high temperature, known as ''firing'', permanent physical and chemical reactions occur which, amongst other changes, causes the clay to be hardened. A fireplace or oven specifically designed for hardening clay is called a [[kiln]]. These properties make clay an ideal substance for making durable [[pottery]] items, both practical and decorative, with different types of clay and firing conditions often used in [[earthenware]], [[stoneware]] and [[porcelain]]. Early humans discovered the useful properties of clay in prehistoric times, and one of the earliest artifacts ever uncovered is a drinking vessel made of sun-dried clay. Depending on the content of the soil, clay can appear in various colors, from a dull gray to a deep orange-red. |

|||

Clay has a high content of clay minerals that give it its plasticity. Clay minerals are [[hydrate|hydrous]] [[aluminium]] [[Silicate minerals#Phyllosilicates|phyllosilicate minerals]], composed of aluminium and silicon ions bonded into tiny, thin plates by interconnecting oxygen and [[hydroxide]] ions. These plates are tough but flexible, and in moist clay, they adhere to each other. The resulting aggregates give clay the cohesion that makes it plastic.{{sfn|Bergaya|Theng|Lagaly|2006|pp=1-18}} In [[kaolinite]] clay, the bonding between plates is provided by a film of water molecules that [[hydrogen bond]] the plates together. The bonds are weak enough to allow the plates to slip past each other when the clay is being moulded, but strong enough to hold the plates in place and allow the moulded clay to retain its shape after it is moulded. When the clay is dried, most of the water molecules are removed, and the plates hydrogen bond directly to each other, so that the dried clay is rigid but still fragile. If the clay is moistened again, it will once more become plastic. When the clay is fired to the [[earthenware]] stage, a [[dehydration reaction]] removes additional water from the clay, causing clay plates to irreversibly adhere to each other via stronger [[covalent bonding]], which strengthens the material. The clay mineral kaolinite is transformed into a non-clay material, [[metakaolin]], which remains rigid and hard if moistened again. Further firing through the [[stoneware]] and [[porcelain]] stages further recrystallizes the metakaolin into yet stronger minerals such as [[mullite]].{{sfn|Breuer|2012}} |

|||

Clays [[sintering|sintered]] in fire were the first [[ceramic]], and remain one of the cheapest to produce and most widely used materials even in the present day. [[Brick]]s, cooking pots, art objects, [[dishware]] and even musical instruments such as the [[ocarina]] are all made with clay. Clay is also used in many industrial processes, such as [[paper]] making, [[cement]] production, [[pottery]], and chemical [[filter (chemistry)|filter]]ing. |

|||

The tiny size and plate form of clay particles gives clay minerals a high surface area. In some clay minerals, the plates carry a negative electrical charge that is balanced by a surrounding layer of positive ions ([[cation]]s), such as sodium, potassium, or calcium. If the clay is mixed with a solution containing other cations, these can swap places with the cations in the layer around the clay particles, which gives clays a high capacity for [[ion exchange]].{{sfn|Bergaya|Theng|Lagaly|2006|pp=1-18}} The chemistry of clay minerals, including their capacity to retain nutrient cations such as potassium and ammonium, is important to soil fertility.{{sfn|Hodges|2010}} |

|||

== Some varieties of clay == |

|||

[[Montmorillonite]], with a chemical formula of ([[Sodium|Na]],[[Calcium|Ca]])<sub>0.33</sub>([[Aluminium|Al]],[[Magnesium|Mg]])<sub>2</sub>[[Silicon|Si]]<sub>4</sub>[[Oxygen|O]]<sub>10</sub>([[Hydroxide|OH]])<sub>2</sub>'''·'''n[[Hydrogen|H]]<sub>2</sub>O, is typically formed as a weathering product of low silica rocks. Montmorillonite is a member of the smectite group and a major component of [[bentonite]]. |

|||

Clay is a common component of [[sedimentary rock]]. [[Shale]] is formed largely from clay and is the most common of sedimentary rocks.{{sfn|Boggs|2006|p=140}} However, most clay deposits are impure. Many naturally occurring deposits include both silts and clay. Clays are distinguished from other fine-grained soils by differences in size and mineralogy. [[Silt]]s, which are fine-grained soils that do not include clay minerals, tend to have larger particle sizes than clays. There is, however, some overlap in particle size and other physical properties. The distinction between silt and clay varies by discipline. [[Geologist]]s and [[soil scientist]]s usually consider the separation to occur at a particle size of 2 [[Micrometre|μm]] (clays being finer than silts), [[sedimentologist]]s often use 4–5 μm, and [[colloid]] [[chemist]]s use 1 μm.{{sfn|Guggenheim|Martin|1995|pp=255–256}} Clay-size particles and clay minerals are not the same, despite a degree of overlap in their respective definitions. [[Geotechnical engineering|Geotechnical engineers]] distinguish between silts and clays based on the plasticity properties of the soil, as measured by the soils' [[Atterberg limits]]. [[International Organization for Standardization|ISO]] 14688 grades clay particles as being smaller than 2 μm and silt particles as being larger. Mixtures of [[sand]], [[silt]] and less than 40% clay are called [[loam]]. |

|||

[[Varve]] (or ''varved clay'') is clay with visible annual layers, formed by seasonal differences in erosion and organic content. This type of deposit is common in former [[glacial lake]]s from an [[ice age]]. |

|||

Some clay minerals (such as [[smectite]]) are described as swelling clay minerals, because they have a great capacity to take up water, and they increase greatly in volume when they do so. When dried, they shrink back to their original volume. This produces distinctive textures, such as [[mudcrack]]s or "popcorn" texture, in clay deposits. Soils containing swelling clay minerals (such as [[bentonite]]) pose a considerable challenge for civil engineering, because swelling clay can break foundations of buildings and ruin road beds.{{sfn|Olive|Chleborad|Frahme|Shlocker|1989}} |

|||

[[Quick clay]] is a unique type of [[marine clay]], indigenous to the glaciated terrains of [[Norway]], [[Canada]], and [[Sweden]]. It is a highly sensitive clay, prone to [[liquefaction]] which has been involved in several deadly [[landslides]]. |

|||

== |

=== Agriculture === |

||

Clay is generally considered undesirable for agriculture. Clay soils are generally less suitable for crops due to poor natural drainage, and requires extensive works and management to make suitable for planting. However, clay soils are generally more fertile and can hold onto nutrients better than other soils due to their higher [[cation-exchange capacity]], allowing more land to remain in production rather than being left [[fallow]]. As clay tends to retain nutrients for longer before leaching them, this also means plants may require more fertilizer in clay soils compared to other soils.<ref name="v874"/><ref name="x742"/> |

|||

* [[Ceramic]] |

|||

* [[Clay (industrial plasticine)]] |

|||

* [[Clay court]] |

|||

* [[Clay minerals]] |

|||

* [[Clay pit]] |

|||

* [[Grain size]] |

|||

* [[List of minerals]] |

|||

* [[London clay]] |

|||

* [[Modelling clay]] |

|||

* [[Paperclay]] |

|||

* [[Plasticine]] |

|||

* [[Pottery]] |

|||

* [[Graham Cairns-Smith]], proposer of the "clay theory" for [[abiogenesis]] |

|||

== |

== Formation == |

||

[[File: Italian and African-American Clay Miners in Mine Shaft.jpg|thumb|Italian and African-American clay miners in mine shaft, 1910]] |

|||

Clay minerals most commonly form by prolonged chemical [[weathering]] of silicate-bearing rocks. They can also form locally from [[hydrothermal]] activity.{{sfn|Foley|1999}} Chemical weathering takes place largely by acid hydrolysis due to low concentrations of [[carbonic acid]], dissolved in rainwater or released by plant roots. The acid breaks bonds between aluminium and oxygen, releasing other metal ions and silica (as a gel of [[orthosilicic acid]]).){{sfn|Leeder|2011|pp=5-11}} |

|||

The clay minerals formed depend on the composition of the source rock and the climate. Acid weathering of [[feldspar]]-rich rock, such as [[granite]], in warm climates tends to produce kaolin. Weathering of the same kind of rock under alkaline conditions produces [[illite]]. [[Smectite]] forms by weathering of [[igneous rock]] under alkaline conditions, while [[gibbsite]] forms by intense weathering of other clay minerals.{{sfn|Leeder|2011|pp=10-11}} |

|||

There are two types of clay deposits: primary and secondary. Primary clays form as residual deposits in soil and remain at the site of formation. Secondary clays are clays that have been transported from their original location by water erosion and [[Deposition (geology)|deposited]] in a new [[sedimentary]] deposit.{{sfn|Murray|2002}} Secondary clay deposits are typically associated with very low energy [[Depositional environment|depositional environments]] such as large lakes and marine basins.{{sfn|Foley|1999}} |

|||

== Varieties == |

|||

The main groups of clays include [[kaolin]]ite, [[montmorillonite]]-[[smectite]], and [[illite]]. [[Chlorite group|Chlorite]], [[vermiculite]],{{sfn|Nesse|2000|p=253}} [[talc]], and [[pyrophyllite]]{{sfn|Klein|Hurlbut|1993|pp=514-515}} are sometimes also classified as clay minerals. There are approximately 30 different types of "pure" clays in these categories, but most "natural" clay deposits are mixtures of these different types, along with other weathered minerals.{{sfn|Klein|Hurlbut|1993|p=512}} Clay minerals in clays are most easily identified using [[Clay mineral X-ray diffraction|X-ray diffraction]] rather than chemical or physical tests.{{sfn|Nesse|2000|p=256}} |

|||

[[Varve]] (or ''varved clay'') is clay with visible annual layers that are formed by seasonal deposition of those layers and are marked by differences in [[erosion]] and organic content. This type of deposit is common in former [[glacial lake]]s. When fine sediments are delivered into the calm waters of these glacial lake basins away from the shoreline, they settle to the lake bed. The resulting seasonal layering is preserved in an even distribution of clay sediment banding.{{sfn|Foley|1999}} |

|||

[[Quick clay]] is a unique type of [[marine clay]] indigenous to the glaciated terrains of [[Norway]], [[North America]], [[Northern Ireland]], and [[Sweden]].{{sfn|Rankka|Andersson-Sköld|Hultén|Larsson|2004}} It is a highly sensitive clay, prone to [[Soil liquefaction|liquefaction]], and has been involved in several deadly [[landslide]]s.{{sfn|Natural Resources Canada|2005}} |

|||

== Uses == |

|||

[[File: Clay In A Construction Site.jpg|thumb|Clay layers in a construction site in [[Auckland]], New Zealand. Dry clay is normally much more stable than sand in excavations.]] |

|||

[[File:Diósgyőr - 2015.02.07 (145).JPG|thumb|upright|left|A 14th-century [[Stopper (plug)|bottle stopper]] made of [[fire clay|fired clay]]]] |

|||

[[Modelling clay]] is used in art and handicraft for [[sculpting]]. |

|||

Clays are used for making [[pottery]], both utilitarian and decorative, and construction products, such as bricks, walls, and floor tiles. Different types of clay, when used with different minerals and firing conditions, are used to produce earthenware, stoneware, and porcelain. Prehistoric humans discovered the useful properties of clay. Some of the earliest pottery shards recovered are from central [[Honshu]], [[Japan]]. They are associated with the [[Jōmon period|Jōmon]] culture, and recovered deposits have been [[radiocarbon dating|dated]] to around 14,000 BCE.{{sfn|Scarre|2005|p=238}} Cooking pots, art objects, dishware, [[smoking pipe (tobacco)|smoking pipes]], and even [[musical instrument]]s such as the [[ocarina]] can all be shaped from clay before being fired. |

|||

Ancient peoples in [[Mesopotamia]] adopted clay tablets as the first known writing medium.{{sfn|Ebert|2011|p=64}} Clay was chosen due to the local material being easy to work with and widely available.<ref>{{Cite web |title=British Library |url=https://www.bl.uk/history-of-writing/articles/a-brief-history-of-writing-materials-and-technologies#:~:text=The%20earliest%20material%20used%20to,drawn%20into%20with%20a%20stylus. |access-date=2023-05-09 |website=www.bl.uk |archive-date=12 September 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220912141816/https://www.bl.uk/history-of-writing/articles/a-brief-history-of-writing-materials-and-technologies#:~:text=The%20earliest%20material%20used%20to,drawn%20into%20with%20a%20stylus. |url-status=dead }}</ref> Scribes wrote on the tablets by inscribing them with a script known as [[cuneiform]], using a blunt [[reed (plant)|reed]] called a [[stylus]], which effectively produced the wedge shaped markings of their writing. After being written on, clay tablets could be reworked into fresh tablets and reused if needed, or fired to make them permanent records. Purpose-made clay balls were used as [[sling (weapon)#Ammunition|sling ammunition]].{{sfn|Forouzan|Glover|Williams|Deocampo|2012}} Clay is used in many industrial processes, such as [[paper]] making, [[cement]] production, and chemical [[filter (chemistry)|filtering]].{{sfn|Nesse|2000|p=257}} [[Bentonite]] clay is widely used as a mold binder in the manufacture of [[sand casting]]s.{{sfn|Boylu|2011}}{{sfn|Eisenhour|Brown|2009}} |

|||

{{external media |

|||

| title = Mass bathing in liquid clay |

|||

| topic = as a type of relaxation |

|||

| float = |

|||

| width = 230px |

|||

| video1 = {{YouTube|id=m7-vA-zOvJM|title=Video (10 minutes)}} |

|||

}} |

|||

[[File:Bain d'argile à Gogotinkpon au Bénin 01.jpg|thumb|Clay bath near [[lake Ahémé]] in [[Benin]]]] |

|||

=== Materials === |

|||

Clay is a common filler used in polymer [[nanocomposites]]. It can reduce the cost of the composite, as well as impart modified behavior: increased [[stiffness]], decreased [[Permeation|permeability]], decreased [[electrical conductivity]], etc.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kotal |first1=M. |last2=Bhowmick |first2=A. K. |title=Polymer nanocomposites from modified clays: Recent advances and challenges |journal=Progress in Polymer Science |date=2015 |volume=51 |pages=127–187 |doi=10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2015.10.001}}</ref> |

|||

=== Medicine === |

|||

Traditional uses of [[medicinal clay|clay as medicine]] go back to prehistoric times. An example is [[Armenian bole]], which is used to soothe an upset stomach. Some animals such as parrots and pigs ingest clay for similar reasons.{{sfn|Diamond|1999}} [[Kaolin|Kaolin clay]] and [[attapulgite]] have been used as anti-diarrheal medicines.{{sfn|Dadu|Hu|Cleeland|Busaidy|2015}} |

|||

=== Construction === |

|||

[[File:WMEE-exp2019-(113).jpg|thumb|left|A clay building in [[South Estonia]]]] |

|||

Clay as the defining ingredient of [[loam]] is one of the oldest [[building material]]s on [[Earth]], among other ancient, naturally occurring geologic materials such as stone and organic materials like wood.{{sfn|Grim|2016}} {{cn span|date=December 2020|Between one-half and two-thirds of the world's population, in both traditional societies as well as developed countries, still live or work in buildings made with clay, often baked into brick, as an essential part of their load-bearing structure.}} Also a primary ingredient in many [[natural building]] techniques, clay is used to create [[adobe]], [[cob (material)|cob]], [[cordwood]], and structures and building elements such as [[wattle and daub]], clay plaster, clay render case, clay floors and clay [[paints]] and [[ceramic building material]]. Clay was used as a [[mortar (masonry)|mortar]] in brick [[chimneys]] and stone walls where protected from water. |

|||

Clay, relatively [[permeability (fluid)|impermeable]] to water, is also used where [[Puddling (civil engineering)|natural seals]] are needed, such as in pond linings, the cores of [[dam]]s, or as a barrier in [[landfill]]s against toxic seepage (lining the landfill, preferably in combination with [[geotextile]]s).{{sfn|Koçkar|Akgün|Aktürk|2005}} Studies in the early 21st century have investigated clay's [[sorption|absorption]] capacities in various applications, such as the removal of [[heavy metals]] from waste water and air purification.{{sfn|García-Sanchez|Alvarez-Ayuso|Rodriguez-Martin|2002}}{{sfn|Churchman|Gates|Theng|Yuan|2006}} |

|||

== See also == |

|||

{{div col}} |

|||

* {{annotated link|Argillaceous minerals}} |

|||

* {{annotated link|Industrial plasticine}} |

|||

* {{annotated link|Clay animation}} |

|||

* {{annotated link|Clay chemistry}} |

|||

* {{annotated link|Clay court}} |

|||

* {{annotated link|Clay panel}} |

|||

* {{annotated link|Clay pit}} |

|||

* {{annotated link|Geophagia}} |

|||

* {{annotated link|Graham Cairns-Smith}} |

|||

* {{annotated link|London Clay}} |

|||

* {{annotated link|Modelling clay}} |

|||

* {{annotated link|Paper clay}} |

|||

* {{annotated link|Particle size}} |

|||

* {{annotated link|Plasticine}} |

|||

* {{annotated link|Vertisol}} |

|||

* {{annotated link|Clay–water interaction}} |

|||

{{div col end}} |

|||

== Notes == |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

== References == |

|||

* [http://www.minsocam.org/msa/collectors_corner/arc/nomenclaturecl1.htm Clay mineral nomenclature] ''American Mineralogist''. |

* [http://www.minsocam.org/msa/collectors_corner/arc/nomenclaturecl1.htm Clay mineral nomenclature] ''American Mineralogist''. |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Bergaya |first1=Faïza |last2=Theng |first2=B. K. G. |last3=Lagaly |first3=Gerhard |title=Handbook of Clay Science |date=2006 |publisher=Elsevier |isbn=978-0-08-044183-2 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uVbam9Snw5sC |language=en}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Boggs |first1=Sam |title=Principles of sedimentology and stratigraphy |date=2006 |publisher=Pearson Prentice Hall |location=Upper Saddle River, N.J. |isbn=0131547283 |edition=4th}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last1=Boylu |first1=Feridun |title=Optimization of foundry sand characteristics of soda-activated calcium bentonite |journal=Applied Clay Science |date=1 April 2011 |volume=52 |issue=1 |pages=104–108 |doi=10.1016/j.clay.2011.02.005|bibcode=2011ApCS...52..104B }} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last1=Breuer |first1=Stephen |title=The chemistry of pottery |journal=Education in Chemistry |date=July 2012 |pages=17–20 |url=https://www.qvevriproject.org/Files/2012.07.00_RSC_Breuer_ChemistryOfPottery.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/https://www.qvevriproject.org/Files/2012.07.00_RSC_Breuer_ChemistryOfPottery.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live |access-date=8 December 2020}} |

|||

* {{cite journal|title = Chapter 11.1 Clays and Clay Minerals for Pollution Control|publisher = Elsevier|journal = Developments in Clay Science|date = 2006|pages = 625–675|volume = 1|series = Handbook of Clay Science|first1 = G. J.|last1 = Churchman|first2 = W. P.|last2 = Gates|first3 = B. K. G.|last3 = Theng|first4 = G.|last4 = Yuan|editor-first = Benny K. G. Theng and Gerhard Lagaly|editor-last = Faïza Bergaya|doi=10.1016/S1572-4352(05)01020-2|isbn = 9780080441832}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last1=Dadu |first1=Ramona |last2=Hu |first2=Mimi I. |last3=Cleeland |first3=Charles |last4=Busaidy |first4=Naifa L. |last5=Habra |first5=Mouhammed |last6=Waguespack |first6=Steven G. |last7=Sherman |first7=Steven I. |last8=Ying |first8=Anita |last9=Fox |first9=Patricia |last10=Cabanillas |first10=Maria E. |title=Efficacy of the Natural Clay, Calcium Aluminosilicate Anti-Diarrheal, in Reducing Medullary Thyroid Cancer–Related Diarrhea and Its Effects on Quality of Life: A Pilot Study |journal=Thyroid |date=October 2015 |volume=25 |issue=10 |pages=1085–1090 |doi=10.1089/thy.2015.0166|pmid=26200040 |pmc=4589264 }} |

|||

* {{cite web |url = http://cogweb.ucla.edu/Abstracts/Diamond_99.html |title = Diamond on Geophagy |first1 = Jared M. |last1 = Diamond |work = ucla.edu |year = 1999 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20150528185034/http://cogweb.ucla.edu/Abstracts/Diamond_99.html |archive-date = 28 May 2015 |df = dmy-all}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HNHyiDm3__kC&q=Clay+tablets+were+the+first+known+writing+medium&pg=PA64|title=The New Media Invasion: Digital Technologies and the World They Unmake|last=Ebert|first=John David|date=31 August 2011|publisher=McFarland|isbn=9780786488186|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171224225732/https://books.google.com/books?id=HNHyiDm3__kC&pg=PA64&dq=Clay+tablets+were+the+first+known+writing+medium&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj-mMuxz5XVAhXixVQKHUpZCPQQ6AEIKTAB#v=onepage&q=Clay%20tablets%20were%20the%20first%20known%20writing%20medium&f=false|archive-date=24 December 2017}} |

|||

* Ehlers, Ernest G. and Blatt, Harvey (1982). 'Petrology, Igneous, Sedimentary, and Metamorphic' [[San Francisco]]: W.H. Freeman and Company. {{ISBN|0-7167-1279-2}}. |

|||

* {{cite journal |last1=Eisenhour |first1=D. D. |last2=Brown |first2=R. K. |title=Bentonite and Its Impact on Modern Life |journal=Elements |date=1 April 2009 |volume=5 |issue=2 |pages=83–88 |doi=10.2113/gselements.5.2.83|bibcode=2009Eleme...5...83E }} |

|||

* {{cite web|url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/info/clays/|last1=Foley |first1=Nora K.|date=September 1999|title=Environmental Characteristics of Clays and Clay Mineral Deposits|work=usgs.gov|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081208055734/http://pubs.usgs.gov/info/clays/|archive-date=8 December 2008}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last1=Forouzan |first1=Firoozeh |last2=Glover |first2=Jeffrey B. |last3=Williams |first3=Frank |last4=Deocampo |first4=Daniel |title=Portable XRF analysis of zoomorphic figurines, "tokens," and sling bullets from Chogha Gavaneh, Iran |journal=Journal of Archaeological Science |date=1 December 2012 |volume=39 |issue=12 |pages=3534–3541 |doi=10.1016/j.jas.2012.04.010|bibcode=2012JArSc..39.3534F }} |

|||

* {{cite journal|title = Sorption of As(V) by some oxyhydroxides and clay minerals. Application to its immobilization in two polluted mining soils|journal = Clay Minerals|date = 1 March 2002|pages = 187–194|volume = 37|issue = 1|doi = 10.1180/0009855023710027|first1 = A.|last1 = García-Sanchez|first2 = E.|last2 = Alvarez-Ayuso|first3 = F.|last3 = Rodriguez-Martin|df = dmy-all|bibcode = 2002ClMin..37..187G|s2cid = 101864343}} |

|||

* {{cite web|last1=Grim|first1=Ralph|year=2016|title=Clay mineral|url=https://www.britannica.com/science/clay-mineral|website=[[Encyclopædia Britannica]]|access-date=10 January 2016|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151209182021/https://www.britannica.com/science/clay-mineral|archive-date=9 December 2015}} |

|||

* {{Citation| last1 =Guggenheim| first1 =Stephen| last2 =Martin| first2 =R. T.| title =Definition of clay and clay mineral: Journal report of the AIPEA nomenclature and CMS nomenclature committees| journal =Clays and Clay Minerals| volume =43| pages =255–256| year =1995| doi =10.1346/CCMN.1995.0430213| issue =2|bibcode = 1995CCM....43..255G | s2cid =129312753| doi-access = }} |

|||

* Hillier S. (2003) "Clay Mineralogy." pp 139–142 In Middleton G.V., Church M.J., Coniglio M., Hardie L.A. and Longstaffe F.J. (Editors) ''Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks''. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht. |

|||

* {{cite web |last1=Hodges |first1=S.C. |year=2010 |title=Soil fertility basics |publisher=Soil Science Extension, North Carolina State University |url=http://www2.mans.edu.eg/projects/heepf/ilppp/cources/12/pdf%20course/38/Nutrient%20Management%20for%20CCA.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www2.mans.edu.eg/projects/heepf/ilppp/cources/12/pdf%20course/38/Nutrient%20Management%20for%20CCA.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live |access-date=8 December 2020}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Klein |first1=Cornelis |last2=Hurlbut | first2=Cornelius S. Jr. |title=Manual of mineralogy : (after James D. Dana) |date=1993 |publisher=Wiley |location=New York |isbn=047157452X |edition=21st}} |

|||

* {{cite web |last1=Koçkar |first1=Mustafa K. |last2=Akgün |first2=Haluk |last3=Aktürk |first3=Özgür |date=November 2005|url=http://www2.widener.edu/~sxw0004/abstract34.html |title=Preliminary evaluation of a compacted bentonite / sand mixture as a landfill liner material (Abstract)] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081204075553/http://www2.widener.edu/~sxw0004/abstract34.html |archive-date=4 December 2008 |website=Department of Geological Engineering, [[Middle East Technical University]], [[Ankara]], [[Turkey]]}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Leeder |first1=M. R. |title=Sedimentology and sedimentary basins : from turbulence to tectonics |date=2011 |publisher=Wiley-Blackwell |location=Chichester, West Sussex, UK |isbn=978-1-40517783-2 |edition=2nd}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last1=Moreno-Maroto |first1=José Manuel |last2=Alonso-Azcárate |first2=Jacinto |title=What is clay? A new definition of "clay" based on plasticity and its impact on the most widespread soil classification systems |journal=Applied Clay Science |date=September 2018 |volume=161 |pages=57–63 |doi=10.1016/j.clay.2018.04.011|bibcode=2018ApCS..161...57M |s2cid=102760108 }} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last1=Murray |first1=H. |year=2002 |title=Industrial clays case study |journal=Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development |volume=64 |pages=1–9 |url=http://whitemudresources.com/public/Hayn%20Murray%20Clays%20Case%20Study.pdf |access-date=8 December 2020 |archive-date=20 April 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210420140406/http://whitemudresources.com/public/Hayn%20Murray%20Clays%20Case%20Study.pdf |url-status=dead }} |

|||

* {{cite web | url=http://geoscape.nrcan.gc.ca/ottawa/landslides_e.php | title=Landslides | publisher=[[Natural Resources Canada]] | work=Geoscape Ottawa-Gatineau | date=7 March 2005 | access-date=2016-07-21 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051024191116/http://geoscape.nrcan.gc.ca/ottawa/landslides_e.php | archive-date=24 October 2005 | url-status=dead |ref={{harvid|Natural Resources Canada|2005}}}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Nesse |first1=William D. |title=Introduction to mineralogy |date=2000 |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=New York |isbn=9780195106916}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last1=Olive |first1=W.W. |last2=Chleborad |first2=A.F. |last3=Frahme |first3=C.W. |last4=Shlocker |first4=Julius |last5=Schneider |first5=R.R. |last6=Schuster |first6=R.L. |year=1989 |url=https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/Prodesc/proddesc_10014.htm |access-date=8 December 2020 |title=Swelling Clays Map of the Conterminous United States |journal=U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Investigations Series Map |volume=I-1940}} |

|||

* {{cite web | url=http://www.swedgeo.se/publikationer/Rapporter/pdf/SGI-R65.pdf | title=Quick clay in Sweden | publisher=Swedish Geotechnical Institute | work=Report No. 65 | date=2004 | access-date=20 April 2005 | last1=Rankka | first1=Karin | last2=Andersson-Sköld | first2=Yvonne | last3=Hultén | first3=Carina | last4=Larsson | first4=Rolf | last5=Leroux | first5=Virginie | last6=Dahlin | first6=Torleif | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050404064431/http://www.swedgeo.se/publikationer/Rapporter/pdf/SGI-R65.pdf | archive-date=4 April 2005 | url-status=dead}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Scarre |first1=C. |year=2005 |title=The Human Past |publisher=Thames and Hudson |location=London |isbn=0500290636}} |

|||

* {{cite web|title=What is clay|url=http://sciencelearn.org.nz/Contexts/Ceramics/Science-Ideas-and-Concepts/What-is-clay|website=Science Learning Hub|publisher=[[University of Waikato]]|access-date=10 January 2016|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160103182308/http://sciencelearn.org.nz/Contexts/Ceramics/Science-Ideas-and-Concepts/What-is-clay|archive-date=3 January 2016 |ref={{harvid|Science Learning Hub|2010}} }} |

|||

* {{cite journal |last1=White |first1=W.A. |year=1949 |title=Atterberg plastic limits of clay minerals |journal=American Mineralogist |volume=34 |issue=7–8 |pages=508–512 |url=http://www.minsocam.org/ammin/AM34/AM34_508.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.minsocam.org/ammin/AM34/AM34_508.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live |access-date=7 December 2020}} |

|||

==External links== |

== External links == |

||

{{Wiktionary}} |

|||

* WHO (2005), ''Bentonite, kaolin, and selected clay minerals'', number 231 ''in'' ‘Environmental Health Criteria’, WHO. Available from: http://www.who.int/entity/ipcs/publications/ehc/ehc231.pdf |

|||

{{Commons category|Clay}} |

|||

{{EB1911 poster|Clay}} |

|||

{{Wikiquote}} |

|||

* [http://www.minersoc.org/pages/groups/cmg/cmg.html The Clay Minerals Group of the Mineralogical Society] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170926234633/http://www.minersoc.org/pages/groups/cmg/cmg.html |date=26 September 2017 }} |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20090217000619/http://stoke.gov.uk/ccm/museums/museum/2006/gladstone-pottery-museum/information-sheets/clays-used-in-the-pottery-industry.en Information about clays used in the UK pottery industry] |

|||

* [http://www.clays.org/ The Clay Minerals Society] |

|||

* [http://digitalfire.com/4sight/education/organic_matter_in_clays_detailed_overview_325.html Organic Matter in Clays] |

|||

{{ |

{{soil type}} |

||

{{Geotechnical engineering|state=collapsed}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Clay| ]] |

||

[[Category:Types of soil]] |

|||

[[Category:Sculpture materials]] |

|||

[[Category:Natural materials]] |

[[Category:Natural materials]] |

||

[[Category:Pedology]] |

|||

[[Category:Sedimentology]] |

[[Category:Sedimentology]] |

||

[[Category:Sediments]] |

[[Category:Sediments]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Phyllosilicates]] |

||

[[Category:Soil-based building materials]] |

|||

[[bg:Глина]] |

|||

[[ca:Argila]] |

|||

[[cs:Jíl]] |

|||

[[da:Ler]] |

|||

[[de:Tonmineral]] |

|||

[[et:Savi]] |

|||

[[es:Arcilla]] |

|||

[[eo:Argilo]] |

|||

[[fr:Argile]] |

|||

[[id:Tanah liat]] |

|||

[[it:Argilla]] |

|||

[[he:חרסית]] |

|||

[[lv:Māli]] |

|||

[[lt:Molis (uoliena)]] |

|||

[[ms:Tanah liat]] |

|||

[[nl:Klei]] |

|||

[[ja:粘土]] |

|||

[[no:Leire]] |

|||

[[ug:سېغىز توپا]] |

|||

[[pl:Glina (skała)]] |

|||

[[pt:Argila]] |

|||

[[ro:Clay]] |

|||

[[ru:Глина]] |

|||

[[simple:Clay]] |

|||

[[fi:Savi]] |

|||

[[sv:Lera]] |

|||

[[vi:Đất sét]] |

|||

[[tr:Kil]] |

|||

[[uk:Глина]] |

|||

[[zh:黏土]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 01:50, 8 January 2025

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals[1] (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolinite, Al2Si2O5(OH)4). Most pure clay minerals are white or light-coloured, but natural clays show a variety of colours from impurities, such as a reddish or brownish colour from small amounts of iron oxide.[2][3]

Clays develop plasticity when wet but can be hardened through firing.[4][5][6] Clay is the longest-known ceramic material. Prehistoric humans discovered the useful properties of clay and used it for making pottery. Some of the earliest pottery shards have been dated to around 14,000 BCE,[7] and clay tablets were the first known writing medium.[8] Clay is used in many modern industrial processes, such as paper making, cement production, and chemical filtering. Between one-half and two-thirds of the world's population live or work in buildings made with clay, often baked into brick, as an essential part of its load-bearing structure. In agriculture, clay content is a major factor in determining land arability. Clay soils are generally less suitable for crops due to poor natural drainage, however clay soils are more fertile, due to higher cation-exchange capacity.[9][10]

Clay is a very common substance. Shale, formed largely from clay, is the most common sedimentary rock.[11] Although many naturally occurring deposits include both silts and clay, clays are distinguished from other fine-grained soils by differences in size and mineralogy. Silts, which are fine-grained soils that do not include clay minerals, tend to have larger particle sizes than clays. Mixtures of sand, silt and less than 40% clay are called loam. Soils high in swelling clays (expansive clay), which are clay minerals that readily expand in volume when they absorb water, are a major challenge in civil engineering.[1]

Properties

[edit]

The defining mechanical property of clay is its plasticity when wet and its ability to harden when dried or fired. Clays show a broad range of water content within which they are highly plastic, from a minimum water content (called the plastic limit) where the clay is just moist enough to mould, to a maximum water content (called the liquid limit) where the moulded clay is just dry enough to hold its shape.[12] The plastic limit of kaolinite clay ranges from about 36% to 40% and its liquid limit ranges from about 58% to 72%.[13] High-quality clay is also tough, as measured by the amount of mechanical work required to roll a sample of clay flat. Its toughness reflects a high degree of internal cohesion.[12]

Clay has a high content of clay minerals that give it its plasticity. Clay minerals are hydrous aluminium phyllosilicate minerals, composed of aluminium and silicon ions bonded into tiny, thin plates by interconnecting oxygen and hydroxide ions. These plates are tough but flexible, and in moist clay, they adhere to each other. The resulting aggregates give clay the cohesion that makes it plastic.[14] In kaolinite clay, the bonding between plates is provided by a film of water molecules that hydrogen bond the plates together. The bonds are weak enough to allow the plates to slip past each other when the clay is being moulded, but strong enough to hold the plates in place and allow the moulded clay to retain its shape after it is moulded. When the clay is dried, most of the water molecules are removed, and the plates hydrogen bond directly to each other, so that the dried clay is rigid but still fragile. If the clay is moistened again, it will once more become plastic. When the clay is fired to the earthenware stage, a dehydration reaction removes additional water from the clay, causing clay plates to irreversibly adhere to each other via stronger covalent bonding, which strengthens the material. The clay mineral kaolinite is transformed into a non-clay material, metakaolin, which remains rigid and hard if moistened again. Further firing through the stoneware and porcelain stages further recrystallizes the metakaolin into yet stronger minerals such as mullite.[6]

The tiny size and plate form of clay particles gives clay minerals a high surface area. In some clay minerals, the plates carry a negative electrical charge that is balanced by a surrounding layer of positive ions (cations), such as sodium, potassium, or calcium. If the clay is mixed with a solution containing other cations, these can swap places with the cations in the layer around the clay particles, which gives clays a high capacity for ion exchange.[14] The chemistry of clay minerals, including their capacity to retain nutrient cations such as potassium and ammonium, is important to soil fertility.[15]

Clay is a common component of sedimentary rock. Shale is formed largely from clay and is the most common of sedimentary rocks.[11] However, most clay deposits are impure. Many naturally occurring deposits include both silts and clay. Clays are distinguished from other fine-grained soils by differences in size and mineralogy. Silts, which are fine-grained soils that do not include clay minerals, tend to have larger particle sizes than clays. There is, however, some overlap in particle size and other physical properties. The distinction between silt and clay varies by discipline. Geologists and soil scientists usually consider the separation to occur at a particle size of 2 μm (clays being finer than silts), sedimentologists often use 4–5 μm, and colloid chemists use 1 μm.[4] Clay-size particles and clay minerals are not the same, despite a degree of overlap in their respective definitions. Geotechnical engineers distinguish between silts and clays based on the plasticity properties of the soil, as measured by the soils' Atterberg limits. ISO 14688 grades clay particles as being smaller than 2 μm and silt particles as being larger. Mixtures of sand, silt and less than 40% clay are called loam.

Some clay minerals (such as smectite) are described as swelling clay minerals, because they have a great capacity to take up water, and they increase greatly in volume when they do so. When dried, they shrink back to their original volume. This produces distinctive textures, such as mudcracks or "popcorn" texture, in clay deposits. Soils containing swelling clay minerals (such as bentonite) pose a considerable challenge for civil engineering, because swelling clay can break foundations of buildings and ruin road beds.[1]

Agriculture

[edit]Clay is generally considered undesirable for agriculture. Clay soils are generally less suitable for crops due to poor natural drainage, and requires extensive works and management to make suitable for planting. However, clay soils are generally more fertile and can hold onto nutrients better than other soils due to their higher cation-exchange capacity, allowing more land to remain in production rather than being left fallow. As clay tends to retain nutrients for longer before leaching them, this also means plants may require more fertilizer in clay soils compared to other soils.[9][10]

Formation

[edit]

Clay minerals most commonly form by prolonged chemical weathering of silicate-bearing rocks. They can also form locally from hydrothermal activity.[16] Chemical weathering takes place largely by acid hydrolysis due to low concentrations of carbonic acid, dissolved in rainwater or released by plant roots. The acid breaks bonds between aluminium and oxygen, releasing other metal ions and silica (as a gel of orthosilicic acid).)[17]

The clay minerals formed depend on the composition of the source rock and the climate. Acid weathering of feldspar-rich rock, such as granite, in warm climates tends to produce kaolin. Weathering of the same kind of rock under alkaline conditions produces illite. Smectite forms by weathering of igneous rock under alkaline conditions, while gibbsite forms by intense weathering of other clay minerals.[18]

There are two types of clay deposits: primary and secondary. Primary clays form as residual deposits in soil and remain at the site of formation. Secondary clays are clays that have been transported from their original location by water erosion and deposited in a new sedimentary deposit.[19] Secondary clay deposits are typically associated with very low energy depositional environments such as large lakes and marine basins.[16]

Varieties

[edit]The main groups of clays include kaolinite, montmorillonite-smectite, and illite. Chlorite, vermiculite,[20] talc, and pyrophyllite[21] are sometimes also classified as clay minerals. There are approximately 30 different types of "pure" clays in these categories, but most "natural" clay deposits are mixtures of these different types, along with other weathered minerals.[22] Clay minerals in clays are most easily identified using X-ray diffraction rather than chemical or physical tests.[23]

Varve (or varved clay) is clay with visible annual layers that are formed by seasonal deposition of those layers and are marked by differences in erosion and organic content. This type of deposit is common in former glacial lakes. When fine sediments are delivered into the calm waters of these glacial lake basins away from the shoreline, they settle to the lake bed. The resulting seasonal layering is preserved in an even distribution of clay sediment banding.[16]

Quick clay is a unique type of marine clay indigenous to the glaciated terrains of Norway, North America, Northern Ireland, and Sweden.[24] It is a highly sensitive clay, prone to liquefaction, and has been involved in several deadly landslides.[25]

Uses

[edit]

Modelling clay is used in art and handicraft for sculpting. Clays are used for making pottery, both utilitarian and decorative, and construction products, such as bricks, walls, and floor tiles. Different types of clay, when used with different minerals and firing conditions, are used to produce earthenware, stoneware, and porcelain. Prehistoric humans discovered the useful properties of clay. Some of the earliest pottery shards recovered are from central Honshu, Japan. They are associated with the Jōmon culture, and recovered deposits have been dated to around 14,000 BCE.[7] Cooking pots, art objects, dishware, smoking pipes, and even musical instruments such as the ocarina can all be shaped from clay before being fired.

Ancient peoples in Mesopotamia adopted clay tablets as the first known writing medium.[8] Clay was chosen due to the local material being easy to work with and widely available.[26] Scribes wrote on the tablets by inscribing them with a script known as cuneiform, using a blunt reed called a stylus, which effectively produced the wedge shaped markings of their writing. After being written on, clay tablets could be reworked into fresh tablets and reused if needed, or fired to make them permanent records. Purpose-made clay balls were used as sling ammunition.[27] Clay is used in many industrial processes, such as paper making, cement production, and chemical filtering.[28] Bentonite clay is widely used as a mold binder in the manufacture of sand castings.[29][30]

| Mass bathing in liquid clay | |

|---|---|

| as a type of relaxation | |

Materials

[edit]Clay is a common filler used in polymer nanocomposites. It can reduce the cost of the composite, as well as impart modified behavior: increased stiffness, decreased permeability, decreased electrical conductivity, etc.[31]

Medicine

[edit]Traditional uses of clay as medicine go back to prehistoric times. An example is Armenian bole, which is used to soothe an upset stomach. Some animals such as parrots and pigs ingest clay for similar reasons.[32] Kaolin clay and attapulgite have been used as anti-diarrheal medicines.[33]

Construction

[edit]

Clay as the defining ingredient of loam is one of the oldest building materials on Earth, among other ancient, naturally occurring geologic materials such as stone and organic materials like wood.[34] Between one-half and two-thirds of the world's population, in both traditional societies as well as developed countries, still live or work in buildings made with clay, often baked into brick, as an essential part of their load-bearing structure.[citation needed] Also a primary ingredient in many natural building techniques, clay is used to create adobe, cob, cordwood, and structures and building elements such as wattle and daub, clay plaster, clay render case, clay floors and clay paints and ceramic building material. Clay was used as a mortar in brick chimneys and stone walls where protected from water.

Clay, relatively impermeable to water, is also used where natural seals are needed, such as in pond linings, the cores of dams, or as a barrier in landfills against toxic seepage (lining the landfill, preferably in combination with geotextiles).[35] Studies in the early 21st century have investigated clay's absorption capacities in various applications, such as the removal of heavy metals from waste water and air purification.[36][37]

See also

[edit]- Argillaceous minerals – Fine-grained aluminium phyllosilicates

- Industrial plasticine – Modeling material which is mainly used by automotive design studios

- Clay animation – Stop-motion animation made using malleable clay models

- Clay chemistry – The chemical structures, properties and reactions of clay minerals

- Clay court – Type of tennis court

- Clay panel – Building material made of clay with some additives

- Clay pit – Open-pit mining for the extraction of clay minerals

- Geophagia – Practice of eating earth or soil-like substrates

- Graham Cairns-Smith – Scottish chemist (1931-2016)

- London Clay – Low-permeable marine geological formation

- Modelling clay – Any of a group of malleable substances used in building and sculpting

- Paper clay – Clay with cellulose fiber

- Particle size – Notion for comparing dimensions of particles in different states of matter

- Plasticine – Brand of modeling clay

- Vertisol – Clay-rich soil, prone to cracking

- Clay–water interaction – Various progressive interactions between clay minerals and water

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Olive et al. 1989.

- ^ Klein & Hurlbut 1993, pp. 512–514.

- ^ Nesse 2000, pp. 252–257.

- ^ a b Guggenheim & Martin 1995, pp. 255–256.

- ^ Science Learning Hub 2010.

- ^ a b Breuer 2012.

- ^ a b Scarre 2005, p. 238.

- ^ a b Ebert 2011, p. 64.

- ^ a b "Soil health and management". Lockhart and Wiseman' s Crop Husbandry Including Grassland. Elsevier. 2023. p. 49–79. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-85702-4.00023-6. ISBN 978-0-323-85702-4.

- ^ a b "Cation Exchange Capacity and Base Saturation". UGA Cooperative Extension. 26 February 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ a b Boggs 2006, p. 140.

- ^ a b Moreno-Maroto & Alonso-Azcárate 2018.

- ^ White 1949.

- ^ a b Bergaya, Theng & Lagaly 2006, pp. 1–18.

- ^ Hodges 2010.

- ^ a b c Foley 1999.

- ^ Leeder 2011, pp. 5–11.

- ^ Leeder 2011, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Murray 2002.

- ^ Nesse 2000, p. 253.

- ^ Klein & Hurlbut 1993, pp. 514–515.

- ^ Klein & Hurlbut 1993, p. 512.

- ^ Nesse 2000, p. 256.

- ^ Rankka et al. 2004.

- ^ Natural Resources Canada 2005.

- ^ "British Library". www.bl.uk. Archived from the original on 12 September 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ Forouzan et al. 2012.

- ^ Nesse 2000, p. 257.

- ^ Boylu 2011.

- ^ Eisenhour & Brown 2009.

- ^ Kotal, M.; Bhowmick, A. K. (2015). "Polymer nanocomposites from modified clays: Recent advances and challenges". Progress in Polymer Science. 51: 127–187. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2015.10.001.

- ^ Diamond 1999.

- ^ Dadu et al. 2015.

- ^ Grim 2016.

- ^ Koçkar, Akgün & Aktürk 2005.

- ^ García-Sanchez, Alvarez-Ayuso & Rodriguez-Martin 2002.

- ^ Churchman et al. 2006.

References

[edit]- Clay mineral nomenclature American Mineralogist.

- Bergaya, Faïza; Theng, B. K. G.; Lagaly, Gerhard (2006). Handbook of Clay Science. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-044183-2.

- Boggs, Sam (2006). Principles of sedimentology and stratigraphy (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0131547283.

- Boylu, Feridun (1 April 2011). "Optimization of foundry sand characteristics of soda-activated calcium bentonite". Applied Clay Science. 52 (1): 104–108. Bibcode:2011ApCS...52..104B. doi:10.1016/j.clay.2011.02.005.

- Breuer, Stephen (July 2012). "The chemistry of pottery" (PDF). Education in Chemistry: 17–20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- Churchman, G. J.; Gates, W. P.; Theng, B. K. G.; Yuan, G. (2006). Faïza Bergaya, Benny K. G. Theng and Gerhard Lagaly (ed.). "Chapter 11.1 Clays and Clay Minerals for Pollution Control". Developments in Clay Science. Handbook of Clay Science. 1. Elsevier: 625–675. doi:10.1016/S1572-4352(05)01020-2. ISBN 9780080441832.

- Dadu, Ramona; Hu, Mimi I.; Cleeland, Charles; Busaidy, Naifa L.; Habra, Mouhammed; Waguespack, Steven G.; Sherman, Steven I.; Ying, Anita; Fox, Patricia; Cabanillas, Maria E. (October 2015). "Efficacy of the Natural Clay, Calcium Aluminosilicate Anti-Diarrheal, in Reducing Medullary Thyroid Cancer–Related Diarrhea and Its Effects on Quality of Life: A Pilot Study". Thyroid. 25 (10): 1085–1090. doi:10.1089/thy.2015.0166. PMC 4589264. PMID 26200040.

- Diamond, Jared M. (1999). "Diamond on Geophagy". ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 28 May 2015.

- Ebert, John David (31 August 2011). The New Media Invasion: Digital Technologies and the World They Unmake. McFarland. ISBN 9780786488186. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017.

- Ehlers, Ernest G. and Blatt, Harvey (1982). 'Petrology, Igneous, Sedimentary, and Metamorphic' San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-1279-2.

- Eisenhour, D. D.; Brown, R. K. (1 April 2009). "Bentonite and Its Impact on Modern Life". Elements. 5 (2): 83–88. Bibcode:2009Eleme...5...83E. doi:10.2113/gselements.5.2.83.

- Foley, Nora K. (September 1999). "Environmental Characteristics of Clays and Clay Mineral Deposits". usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008.

- Forouzan, Firoozeh; Glover, Jeffrey B.; Williams, Frank; Deocampo, Daniel (1 December 2012). "Portable XRF analysis of zoomorphic figurines, "tokens," and sling bullets from Chogha Gavaneh, Iran". Journal of Archaeological Science. 39 (12): 3534–3541. Bibcode:2012JArSc..39.3534F. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.04.010.

- García-Sanchez, A.; Alvarez-Ayuso, E.; Rodriguez-Martin, F. (1 March 2002). "Sorption of As(V) by some oxyhydroxides and clay minerals. Application to its immobilization in two polluted mining soils". Clay Minerals. 37 (1): 187–194. Bibcode:2002ClMin..37..187G. doi:10.1180/0009855023710027. S2CID 101864343.

- Grim, Ralph (2016). "Clay mineral". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 December 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- Guggenheim, Stephen; Martin, R. T. (1995), "Definition of clay and clay mineral: Journal report of the AIPEA nomenclature and CMS nomenclature committees", Clays and Clay Minerals, 43 (2): 255–256, Bibcode:1995CCM....43..255G, doi:10.1346/CCMN.1995.0430213, S2CID 129312753

- Hillier S. (2003) "Clay Mineralogy." pp 139–142 In Middleton G.V., Church M.J., Coniglio M., Hardie L.A. and Longstaffe F.J. (Editors) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht.

- Hodges, S.C. (2010). "Soil fertility basics" (PDF). Soil Science Extension, North Carolina State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- Klein, Cornelis; Hurlbut, Cornelius S. Jr. (1993). Manual of mineralogy : (after James D. Dana) (21st ed.). New York: Wiley. ISBN 047157452X.

- Koçkar, Mustafa K.; Akgün, Haluk; Aktürk, Özgür (November 2005). "Preliminary evaluation of a compacted bentonite / sand mixture as a landfill liner material (Abstract)]". Department of Geological Engineering, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008.

- Leeder, M. R. (2011). Sedimentology and sedimentary basins : from turbulence to tectonics (2nd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-40517783-2.

- Moreno-Maroto, José Manuel; Alonso-Azcárate, Jacinto (September 2018). "What is clay? A new definition of "clay" based on plasticity and its impact on the most widespread soil classification systems". Applied Clay Science. 161: 57–63. Bibcode:2018ApCS..161...57M. doi:10.1016/j.clay.2018.04.011. S2CID 102760108.

- Murray, H. (2002). "Industrial clays case study" (PDF). Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development. 64: 1–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- "Landslides". Geoscape Ottawa-Gatineau. Natural Resources Canada. 7 March 2005. Archived from the original on 24 October 2005. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Nesse, William D. (2000). Introduction to mineralogy. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195106916.

- Olive, W.W.; Chleborad, A.F.; Frahme, C.W.; Shlocker, Julius; Schneider, R.R.; Schuster, R.L. (1989). "Swelling Clays Map of the Conterminous United States". U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Investigations Series Map. I-1940. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- Rankka, Karin; Andersson-Sköld, Yvonne; Hultén, Carina; Larsson, Rolf; Leroux, Virginie; Dahlin, Torleif (2004). "Quick clay in Sweden" (PDF). Report No. 65. Swedish Geotechnical Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2005. Retrieved 20 April 2005.

- Scarre, C. (2005). The Human Past. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0500290636.

- "What is clay". Science Learning Hub. University of Waikato. Archived from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- White, W.A. (1949). "Atterberg plastic limits of clay minerals" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 34 (7–8): 508–512. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2020.