Tristan da Cunha: Difference between revisions

Davidships (talk | contribs) →20th century: copyedit |

JackintheBox (talk | contribs) m →Religion: wikilink |

||

| (531 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ |

{{Short description|South Atlantic island group}} |

||

{{ |

{{Good article}} |

||

{{ |

{{About|the South Atlantic island group|the Portuguese explorer|Tristão da Cunha}} |

||

{{good article}} |

|||

{{EngvarB|date=October 2015}} |

{{EngvarB|date=October 2015}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date= |

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2024}} |

||

{{Infobox dependency |

{{Infobox dependency |

||

| name = Tristan da Cunha |

| name = Tristan da Cunha |

||

| Line 10: | Line 9: | ||

| linking_name = Tristan da Cunha |

| linking_name = Tristan da Cunha |

||

| image_flag = Flag of Tristan da Cunha.svg |

| image_flag = Flag of Tristan da Cunha.svg |

||

| flag_size = |

| flag_size = 130px |

||

| flag_link = Flag of Tristan da Cunha |

| flag_link = Flag of Tristan da Cunha |

||

| image_seal = Coat of arms of Tristan da Cunha.svg |

| image_seal = Coat of arms of Tristan da Cunha.svg |

||

| seal_size = |

| seal_size = 80px |

||

| seal_type = Coat of arms |

| seal_type = Coat of arms |

||

| seal_link = Coat of arms of Tristan da Cunha |

| seal_link = Coat of arms of Tristan da Cunha |

||

| motto = "Our faith is our strength" |

| motto = "Our faith is our strength" |

||

| anthem = "[[God Save the |

| anthem = "[[God Save the King]]"<br /><div |

||

style="display:inline-block;margin-top:0.4em;">[[File:U.S. Navy Band - God Save the King.oga]]</div> |

|||

| song = "[[Cutty Wren|The Cutty Wren]]" |

| song = "[[Cutty Wren|The Cutty Wren]]" |

||

| song_type = Territorial song |

| song_type = Territorial song |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

|caption = |

|caption = |

||

|places = |

|places = |

||

{{Location map~ |South Atlantic |

|||

|mark=Redpoint2.svg |

|||

|marksize=5 |

|||

|lat_deg=7 |lat_min=56 |lat_dir=S |lon_deg=14 |lon_min=22 |lon_dir=W |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |South Atlantic |

|||

|mark= BSicon lHST.svg |

|||

|marksize=3 |

|||

|lat_deg=7 |lat_min=56 |lat_dir=S |lon_deg=14 |lon_min=22 |lon_dir=W |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |South Atlantic |

|||

|mark=Redpoint2.svg |

|||

|marksize=5 |

|||

|lat_deg=15 |lat_min=57 |lat_dir=S |lon_deg=005 |lon_min=43 |lon_dir=W |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |South Atlantic |

|||

|mark=BSicon lHST.svg |

|||

|marksize=3 |

|||

|lat_deg=15 |lat_min=57 |lat_dir=S |lon_deg=005 |lon_min=43 |lon_dir=W |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Location map~ |South Atlantic |

{{Location map~ |South Atlantic |

||

|mark=Redpoint2.svg |

|mark=Redpoint2.svg |

||

| Line 94: | Line 74: | ||

| map_caption2 = Location of Tristan da Cunha archipelago (circled in red) in the southern [[Atlantic Ocean]] |

| map_caption2 = Location of Tristan da Cunha archipelago (circled in red) in the southern [[Atlantic Ocean]] |

||

| subdivision_type = [[Sovereign state]] |

| subdivision_type = [[Sovereign state]] |

||

| subdivision_name = |

| subdivision_name = {{flag|United Kingdom}} |

||

| established_title = First settlement |

| established_title = First settlement |

||

| established_date = 1810 |

| established_date = 1810 |

||

| established_title2 = Dependency of [[Cape Colony]] |

| established_title2 = Dependency of [[Cape Colony]] |

||

| established_date2 = 14 August 1816<ref name="Crawford1982">{{cite book|last=Crawford|first=Allan|title=Tristan da Cunha and the Roaring Forties|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_fIuAQAAIAAJ| |

| established_date2 = 14 August 1816<ref name="Crawford1982">{{cite book |last=Crawford |first=Allan |title=Tristan da Cunha and the Roaring Forties |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_fIuAQAAIAAJ |access-date=13 August 2013 |year=1982 |publisher=Charles Skilton |page=20 |isbn=9780284985897}}</ref> |

||

| established_title3 = Dependency of Saint Helena |

| established_title3 = Dependency of Saint Helena |

||

| established_date3 = 12 January 1938 |

| established_date3 = 12 January 1938 |

||

| Line 105: | Line 85: | ||

| official_languages = [[English language|English]] |

| official_languages = [[English language|English]] |

||

| capital = [[Edinburgh of the Seven Seas]] |

| capital = [[Edinburgh of the Seven Seas]] |

||

| coordinates = {{Coord|37|4|S|12| |

| coordinates = {{Coord|37|4|3|S|12|18|40|W|type:city}} |

||

| largest_settlement = capital |

| largest_settlement = capital |

||

| largest_settlement_type = largest settlement |

| largest_settlement_type = largest settlement |

||

| Line 112: | Line 92: | ||

| government_type = [[Devolution|Devolved]] [[Local government|locally governing]] [[Dependent territory|dependency]] under a [[constitutional monarchy]] |

| government_type = [[Devolution|Devolved]] [[Local government|locally governing]] [[Dependent territory|dependency]] under a [[constitutional monarchy]] |

||

| leader_title1 = [[Monarchy of the United Kingdom|Monarch]] |

| leader_title1 = [[Monarchy of the United Kingdom|Monarch]] |

||

| leader_name1 = [[ |

| leader_name1 = [[Charles III]] |

||

| leader_title2 = [[Governor of |

| leader_title2 = [[Governor of Tristan da Cunha|Governor]] |

||

| leader_name2 = |

| leader_name2 = [[Nigel Phillips]] |

||

| leader_title3 = [[Administrator of Tristan da Cunha|Administrator]] |

| leader_title3 = [[Administrator of Tristan da Cunha|Administrator]] |

||

| leader_name3 = Philip Kendall<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.tristandc.com/government/news-2023-09-26-philipkendallasi.php |title=Philip Kendall sworn-in as Tristan Administrator |first=Richard |last=Grundy |website=www.tristandc.com |access-date=2 October 2023 |archive-date=11 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231011014324/https://www.tristandc.com/government/news-2023-09-26-philipkendallasi.php |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

| leader_name3 = Fiona Kilpatrick and Stephen Townsend (job share) |

|||

| leader_title4 = [[Tristan da Cunha Island Council|Chief Islander]] |

| leader_title4 = [[Tristan da Cunha Island Council|Chief Islander]] |

||

| leader_name4 = James Glass<ref>{{cite web|title=Tristan da Cunha Chief Islander|url=http://www.tristandc.com/chiefislander.php|publisher=Tristan da Cunha Government & Tristan da Cunha Association| |

| leader_name4 = [[James Glass (Chief Islander)|James Glass]]<ref>{{cite web |title=Tristan da Cunha Chief Islander |url=http://www.tristandc.com/chiefislander.php |publisher=Tristan da Cunha Government & Tristan da Cunha Association |access-date=11 October 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140906000250/http://www.tristandc.com/chiefislander.php |archive-date=6 September 2014 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

| legislature = [[Tristan da Cunha Island Council|Island Council]] |

| legislature = [[Tristan da Cunha Island Council|Island Council]] |

||

| national_representation = [[Government of the United Kingdom]] |

| national_representation = [[Government of the United Kingdom]] |

||

| national_representation_type1 = Minister |

| national_representation_type1 = [[Minister of State for Europe, North America and Overseas Territories|Minister]] |

||

| national_representation1 = [[ |

| national_representation1 = [[Stephen Doughty]] |

||

| area_km2 = 207 |

| area_km2 = 207 |

||

| area_label2 = Main island |

| area_label2 = Main island |

||

| area_data2 = {{ |

| area_data2 = {{cvt|98|km2|sqmi}} |

||

| elevation_max_m = 2,062 |

| elevation_max_m = 2,062 |

||

| population_estimate = |

| population_estimate = 238<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.tristandc.com/population.php |title=Tristan da Cunha Population Update |first=Cynthia |last=Green |website=www.tristandc.com |access-date=28 November 2019 |archive-date=28 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191128111631/https://www.tristandc.com/population.php |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

| population_estimate_year = |

| population_estimate_year = 2023 |

||

| population_estimate_rank = |

| population_estimate_rank = |

||

| population_census = 293<ref name="census2016">{{cite web |url=http://www.sainthelena.gov.sh/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Census-2016-summary-report.pdf |title=Census 2016 – summary report |publisher=St. Helena Government |page=9 |date=June 2016 | |

| population_census = 293<ref name="census2016">{{cite web |url=http://www.sainthelena.gov.sh/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Census-2016-summary-report.pdf |title=Census 2016 – summary report |publisher=St. Helena Government |page=9 |date=June 2016 |access-date=23 January 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161017192624/http://www.sainthelena.gov.sh/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Census-2016-summary-report.pdf |archive-date=17 October 2016 |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

||

| population_census_year = 2016 |

| population_census_year = 2016 |

||

| population_density_km2 = 1.4 |

| population_density_km2 = 1.4 |

||

| Line 141: | Line 121: | ||

| date_format = dd/mm/yyyy |

| date_format = dd/mm/yyyy |

||

| drives_on = left |

| drives_on = left |

||

| calling_code = |

| calling_code = +44 20 ''(assigned [[Telephone numbers in Saint Helena and Tristan da Cunha|+290]])'' |

||

| postal_code_type = [[Postcodes in the United Kingdom#British Overseas Territories|UK postcode]] |

| postal_code_type = [[Postcodes in the United Kingdom#British Overseas Territories|UK postcode]] |

||

| postal_code = TDCU 1ZZ |

| postal_code = TDCU 1ZZ |

||

| Line 147: | Line 127: | ||

| cctld = {{hlist|[[.sh]]|[[.uk]]}} |

| cctld = {{hlist|[[.sh]]|[[.uk]]}} |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Tristan da Cunha''' ({{IPAc-en|ˌ|t|r|ɪ|s|t|ən|_|d|ə|_|ˈ|k|uː|n|(|j|)|ə}}), colloquially '''Tristan''', is a remote group of [[volcano|volcanic]] |

'''Tristan da Cunha''' ({{IPAc-en|ˌ|t|r|ɪ|s|t|ən|_|d|ə|_|ˈ|k|uː|n|(|j|)|ə}}), colloquially '''Tristan''', is a remote group of [[volcano|volcanic]] islands in the [[South Atlantic Ocean]]. It is the [[Extreme points of Earth|most remote]] inhabited [[archipelago]] in the world, lying approximately {{convert|1732|mi|km|order=flip}} from [[Cape Town, South Africa|Cape Town]] in [[South Africa]], {{convert|1514|mi|km|order=flip}} from [[Saint Helena]], {{convert|3949|km|mi|order=}} from [[Mar del Plata]]<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.google.com/search?q=tristan+da+cunha+to+mar+del+plata+distance |title=tristan da cunha to mar del plata distance - Google Search |website=www.google.com |access-date=1 January 2023 |archive-date=26 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231026130224/https://www.google.com/search?q=tristan+da+cunha+to+mar+del+plata+distance |url-status=live }}</ref> in [[Argentina]], and {{convert|2487|mi|km|order=flip}} from the [[Falkland Islands]].<ref name="howstuffworks.com">{{cite web |url=http://adventure.howstuffworks.com/most-remote-place1.htm |last=Winkler |first=Sarah |title=Where is the Most Remote Spot on Earth? Tristan da Cunha: The World's Most Remote Inhabited Island |website=[[How Stuff Works]] |access-date=28 December 2018 |date=25 August 2009 |archive-date=27 September 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090927152003/http://adventure.howstuffworks.com/most-remote-place1.htm |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.thoughtco.com/tristan-da-cunha-1435571 |title=Tristan da Cunha: The World's Most Remote Island |first=Matt |last=Rosenberg |website=ThoughtCo.com |date=6 March 2017 |access-date=28 December 2018 |archive-date=24 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220524054103/https://www.thoughtco.com/tristan-da-cunha-1435571 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

The territory consists of the inhabited island |

The territory consists of the inhabited island Tristan da Cunha, which has a diameter of roughly {{convert|11|km}} and an area of {{convert|98|km2}}; the wildlife reserves of [[Gough Island]] and [[Inaccessible Island]]; and the smaller, uninhabited [[Nightingale Islands]]. {{As of|October 2018}}, the main island has 250 permanent inhabitants, who all carry [[British Overseas Territories citizen]]ship.<ref name="tristandc.com">{{cite web |title=Tristan da Cunha Family News |url=https://www.tristandc.com/population.php |access-date=28 November 2021 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211121070744/https://www.tristandc.com/population.php |archive-date=21 November 2021}}</ref> The other islands are uninhabited, except for the South African personnel of a weather station on Gough Island. |

||

Tristan da Cunha is |

Tristan da Cunha is one of three constituent parts of the [[British Overseas Territories|British Overseas Territory]] of [[Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha]], with its own constitution.<ref name="Constitution">{{Cite web |url=http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2009/1751/schedule/made |title=The St. Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha Constitution Order 2009 |year=2009 |website=The National Archives |access-date=5 January 2019 |archive-date=11 May 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110511202653/http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2009/1751/schedule/made |url-status=live }}</ref> There is no [[airstrip]] on the main island; the only way of travelling in and out of Tristan is by ship, a six-day trip from [[South Africa]].<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.lonelyplanet.com/articles/tristan-da-cunha-a-journey-to-the-centre-of-the-ocean |title=Tristan da Cunha: a journey to the centre of the ocean |last=Corne |first=Lucy |website=Lonely Planet |language=en |access-date=9 April 2020 |archive-date=5 June 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200605115824/https://www.lonelyplanet.com/articles/tristan-da-cunha-a-journey-to-the-centre-of-the-ocean |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

| Line 158: | Line 138: | ||

===Discovery=== |

===Discovery=== |

||

[[File:Tristano da Acugna (Giovio Series) (cropped2).jpg|thumb|left|[[Portuguese Empire|Portuguese]] explorer and [[conquistador]] [[Tristão da Cunha]] is both the namesake of Tristan da Cunha and the first person to sight the island, in 1506.]] |

[[File:Tristano da Acugna (Giovio Series) (cropped2).jpg|thumb|left|[[Portuguese Empire|Portuguese]] explorer and [[conquistador]] [[Tristão da Cunha]] is both the namesake of Tristan da Cunha and the first person to sight the island, in 1506.]] |

||

The islands were first recorded as sighted in 1506 by [[Portugal|Portuguese]] explorer [[Tristão da Cunha]], though rough seas prevented a landing. He named the main island after himself, |

The uninhabited islands were first recorded as sighted in 1506 by [[Portugal|Portuguese]] explorer [[Tristão da Cunha]], though rough seas prevented a landing. He named the main island after himself, {{lang|pt|Ilha de Tristão da Cunha}}. It was later anglicised from its earliest mention on British [[Admiralty chart]]s to Tristan da Cunha Island. Some sources state that the Portuguese made the first landing in 1520, when ''Lás Rafael'', captained by Ruy Vaz Pereira, called at Tristan for water.<ref name="annals">{{cite book |url=http://www.tristan.it/TRISTAN/tristanlibri/tristan_annals.pdf |first1=Arnaldo |last1=Faustini |title=The Annals of Tristan da Cunha |date= 2003 |access-date=28 December 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150510041635/http://www.tristan.it/TRISTAN/tristanlibri/tristan_annals.pdf |archive-date=10 May 2015 |url-status=live |editor1-first=Paul |editor1-last=Carrol |translator1-first=Liz |translator1-last=Nysven |translator2-first=Larry |translator2-last=Conrad |page=9}}</ref> |

||

The first undisputed landing was made on 7 February 1643 by the crew of the [[Dutch East India Company]] ship ''Heemstede,'' captained by Claes Gerritsz Bierenbroodspot. The Dutch stopped at the island four more times in the next 25 |

The first undisputed landing was made on 7 February 1643 by the crew of the [[Dutch East India Company]] ship ''Heemstede,'' captained by Claes Gerritsz Bierenbroodspot. The Dutch stopped at the island four more times in the next 25{{nbsp}}years, and in 1656 created the first rough charts of the archipelago.<ref name=headland>{{cite book |last=Headland |first=J.K. |year=1989 |title=Chronological list of Antarctic expeditions and related historical events |location=Cambridge, UK |publisher=Cambridge University Press |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Sg49AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA63 |access-date=28 December 2018 |isbn=9780521309035}}</ref> |

||

The first full [[Geophysical survey|survey]] of the archipelago was made by crew of the French [[corvette]] ''Heure du Berger'' in 1767. The first scientific exploration was conducted by French naturalist [[Louis-Marie Aubert du Petit-Thouars]], who stayed on the island for three days in January 1793, during a French mercantile expedition from [[Brest, France]] to [[Mauritius]]. Thouars made botanical collections and reported traces of human habitation, including [[fireplaces]] and overgrown [[gardens]], probably left by Dutch explorers in the 17th century.<ref name=headland/> |

The first full [[Geophysical survey|survey]] of the archipelago was made by the crew of the French [[corvette]] ''Heure du Berger'' in 1767. The first scientific exploration was conducted by French naturalist [[Louis-Marie Aubert du Petit-Thouars]], who stayed on the island for three days in January 1793, during a French mercantile expedition from [[Brest, France]], to [[Mauritius]]. Thouars made botanical collections and reported traces of human habitation, including [[fireplaces]] and overgrown [[gardens]], probably left by Dutch explorers in the 17th century.<ref name=headland/> |

||

On his voyage out from Europe to East Africa and India in command of the [[Austrian East India Company|Imperial Asiatic Company of Trieste and Antwerp]] ship, ''Joseph |

On his voyage out from Europe to East Africa and India in command of the [[Austrian East India Company|Imperial Asiatic Company of Trieste and Antwerp]] ship, ''Joseph and Theresa'', [[William Bolts]] sighted Tristan da Cunha, put a landing party ashore on 2 February 1777 and hoisted the Imperial flag, naming it and its neighbouring islets the Brabant Islands.<ref>{{cite book |first=Nicolaus |last=Fontana |title=Tagebuch der Reise des k.k. Schiffes Joseph und Theresia nach den neuen österreichischen Pflanzorten in Asia und Afrika |translator-first=Joseph |translator-last=Eyerel |place=Dessau und Leipzig |year=1782}}<br/>re-published as {{cite book |editor-first=G. |editor-last=Pilleri |title=Maria Teresa e le Indie orientali: La spedizione alle Isole Nicobare della nave Joseph und Theresia e il diario del chirurgo di bordo |place=Bern, CH |publisher=Verlag de hirnanatomischen Institutes |year=1982 |page=9}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |first=Guillaume |last=Bolts |title=Précis de l'Origine, de la Marche et de la Chûte de la Compagnie d'Asie et d'Afrique dans les Ports du Littoral Autrichien |place=Liege |year=1785 |page=14}}<br/>cited in {{cite book |first=Ernest Jean |last=van Bruyssel |title=Histoire du commerce et de la marine en Belgique |place=Bruxelles |year=1865 |volume=3 |pages=295–299}}<br/>and cited in {{cite book |first=Jan |last=Brander |title=Tristan da Cunha, 1506–1902 |place=London|publisher=Unwin |year=1940 |pages=49–50}}<br/>and cited in article {{cite encyclopedia |encyclopedia=Biographie nationale ... de Belgique |place=Bruxelles |year=1905 |title=Charles Proli}}</ref> However, no settlement or facilities were ever set up there by the company.{{Citation needed|date=October 2023}} |

||

After the outbreak of the [[American Revolutionary War]] halted [[penal transportation]] to [[Thirteen Colonies]], British prisons started to [[Prison overcrowding|overcrowd]]. |

After the outbreak of the [[American Revolutionary War]] halted [[penal transportation]] to the [[Thirteen Colonies]], British prisons started to [[Prison overcrowding in the United Kingdom|overcrowd]]. As several stopgap measures proved to be ineffective, the British Government announced in December 1785 that it would proceed with the settlement of [[New South Wales]]. In September 1786 [[Alexander Dalrymple]], presumably goaded by Bolts's actions, published a pamphlet<ref>{{cite book |author-link=Alexander Dalrymple |first=A. |last=Dalrymple |title=A Serious Admonition to the Publick on the Intended Thief Colony at Botany Bay |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-19515009/view?partId=nla.obj-19595227#page/n2/mode/1up |page=2 |id=NLA part ID 19595227 |via=National Library of Australia |place=London |publisher=Sewell}}</ref> with an alternative proposal of his own for settlements on Tristan da Cunha, [[Île Saint-Paul|St. Paul]] and [[Île Amsterdam|Amsterdam]] islands in the Southern Ocean.{{Citation needed|date=October 2023}} |

||

Captain [[John Blankett]], R.N., also suggested independently to his superiors in August 1786 that convicts be used to establish a British settlement on Tristan.{{refn|{{cite letter |last=Blankett |first=John |

Captain [[John Blankett]], [[Royal Navy|R.N.]], also suggested independently to his superiors in August 1786 that convicts be used to establish a British settlement on Tristan.{{refn|{{cite letter |last=Blankett |first=John |author-link=John Blankett |recipient=Howe |subject=[settlement on Tristan da Cunha] |date=6 August 1786 |publisher=National Maritime Museum |place=Greenwich |id=HOW 3}}<br/> cited in Frost (1980)<ref name=Frost_1980/>{{rp|pages=119,216}} }} In consequence, the Admiralty received orders from the government in October 1789 to examine the island as part of a general survey of the South Atlantic and the coasts of southern Africa.{{refn|{{cite letter |last=Grenville |recipient=Admiralty Lords |subject=[general survey of the South Atlantic] |date=3 October 1789 |publisher=Public Record Office |id=ADM 1/4154: 43}}<br/>cited in Frost (1980)<ref name=Frost_1980>{{cite book |first=Alan |last=Frost |title=Convicts & Empire: A naval question, 1776–1811 |place=Melbourne |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=1980}}</ref>{{rp|pages=148, 220}} }} That did not happen, but an investigation of Tristan, Amsterdam and St. Paul was undertaken in December 1792 and January 1793 by [[George Macartney, 1st Earl Macartney|George Macartney]], Britain's first ambassador to China. During his voyage to China, he established that none of the islands were suitable for settlement.<ref>{{cite book |first=Helen H. |last=Robbins |title=Our First Ambassador to China |place=London |publisher=Murray |year=1908 |pages=197–210}}</ref> |

||

===19th century=== |

===19th century=== |

||

The first permanent settler was [[Jonathan Lambert]] of [[Salem, Massachusetts]], United States, who moved to the island in December 1810 with two other men, |

The first permanent settler was [[Jonathan Lambert (sailor)|Jonathan Lambert]] of [[Salem, Massachusetts]], United States, who moved to the island in December 1810 with two other men, to be joined later by a fourth.<ref name=mackay>{{cite book |last=Mackay |first=Margaret |year=1963 |title=Angry Island: The Story of Tristan da Cunha, 1506–1963 |location=London |publisher=Arthur Barker |page=30}}</ref> Lambert publicly declared the islands his property and named them the [[Islands of Refreshment]]. Three of the four men died in 1812 and [[Thomas Currie (settler)|Thomas Currie]] (Tommaso Corri, from [[Livorno]], [[Italy]]), one of the original three, remained as a farmer on the island.<ref>{{cite magazine |title=Tristan d'Acunha, etc.: Jonathan Lambert, late Sovereign thereof |magazine=Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine |volume=4 |issue=21 |date=Dec 1818 |pages=280–285 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tt_QAAAAMAAJ |via=Google Books}}</ref> |

||

On 14 August 1816, the United Kingdom [[Annexation|annexed]] the islands, making them a dependency of the [[Cape Colony]] in South Africa. This was explained as a measure to prevent the islands' use as a base for any attempt to free [[Napoleon|Napoleon Bonaparte]] from his prison on [[Saint Helena]].<ref name=Roberts1/> The occupation also prevented the United States from using Tristan da Cunha as a base for naval [[cruiser]]s, as it had during the [[War of 1812]].<ref name=mackay/> |

On 14 August 1816, the United Kingdom [[Annexation|annexed]] the islands by sending a garrison to secure possession, and making them a dependency of the [[Cape Colony]] in South Africa. This was explained as a measure to prevent the islands' use as a base for any attempt to free [[Napoleon|Napoleon Bonaparte]] from his prison on [[Saint Helena]].<ref name=Roberts1/> The occupation also prevented the United States from using Tristan da Cunha as a base for naval [[cruiser]]s, as it had during the [[War of 1812]].<ref name=mackay/> The garrison left the islands in November 1817, although some members of the garrison, notably [[William Glass]], stayed and formed the nucleus of a permanent population.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Flower |first=Robin |date=May 1935 |title=Tristan da Cunha Records |journal=[[British Museum Quarterly|The British Museum Quarterly]] |volume=9 |issue=4 |pages=121–123 |doi=10.2307/4421742 |jstor=4421742}}</ref> |

||

[[File:Augustus Earle, (Self Portrait) Solitude, Tristan da Cunha, 1824.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Augustus Earle, ''(Self Portrait) Solitude, watching the horizon at sun set, in the hopes of seeing a vessel, Tristan de Acunha (i.e. da Cunha) in the South Atlantic'', (1824): watercolour; {{cvt|17.5|x|25.7|cm}}. [[National Library of Australia]] ]] |

|||

{{Quote box |

{{Quote box |

||

| quote = On the fifteenth of July, the snow-clad mountains of Tristan da Cunha appeared, lighted by a brilliant morning-sun, and towering to a height estimated at between nine and ten thousand feet."<ref name=Roberts1>{{cite book |last=Roberts |first=Edmund |title=Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat |year=1837 |publisher=Harper & Brothers |location=New York |page=33 |url=http://www.wdl.org/en/item/7317/view/1/33/ |access-date=11 October 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131012040501/http://www.wdl.org/en/item/7317/view/1/33/ |archive-date=12 October 2013 |url-status=live |df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

| quote = On the fifteenth of July, the snow-clad mountains of Tristan da Cunha appeared, lighted by a brilliant morning-sun, and towering to a height estimated at between nine and ten thousand feet."<ref name=Roberts1>{{cite book |last=Roberts |first=Edmund |title=Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat |year=1837 |publisher=Harper & Brothers |location=New York |page=33 |url=http://www.wdl.org/en/item/7317/view/1/33/ |access-date=11 October 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131012040501/http://www.wdl.org/en/item/7317/view/1/33/ |archive-date=12 October 2013 |url-status=live |df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

||

| source = [[Edmund Roberts (diplomat)|Edmund Roberts]], ''Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat'', 1837 |

| source = [[Edmund Roberts (diplomat)|Edmund Roberts]], ''Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat'', 1837 |

||

| align = |

| align = right |

||

| width = |

| width = 20% |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The artist [[Augustus Earle]] spent eight months stranded there in 1824. He had been on the aging ship ''Duke of Gloucester'', bound for Calcutta, which had anchored there for three days due to a storm. Earle and a crew member were left when the ''Gloucester'' unexpectedly sailed. Earle tutored several children and painted until his supplies ran out. He was rescued in late November by the ship {{ship||Admiral Cockburn|1814 ship|2}} on its way to Hobart. |

|||

The islands were occupied by a garrison of [[Royal Marines|British Marines]], and a civilian population gradually grew. {{ship||Berwick|1795 ship|2}} stopped there on 25 March 1824 and reported that it had a population of twenty-two men and three women. The barque ''South Australia'' stayed there on 18–20 February 1836 when a certain Glass was Governor, as reported in a chapter on the island by W. H. Leigh.<ref>{{cite book |first=W. H., esq. |last=Leigh |title=Travels and Adventures in South Australia |place=London, UK |orig-year=1839 |edition=facsimile |publisher=The Currawong Press |year=1982}}</ref> |

|||

The islands were occupied by a garrison of [[Royal Marines|British Marines]], and a civilian population gradually grew. {{ship||Berwick|1795 ship|2}} stopped there on 25 March 1824 and reported that it had a population of twenty-two men and three women. The barque ''South Australia'' stayed there on 18–20 February 1836 when a certain Glass was governor, as reported in a chapter on the island by W. H. Leigh.<ref>{{cite book |first=W. H. |last=Leigh |title=Travels and Adventures in South Australia |place=London |orig-year=1839 |edition=facsimile |publisher=The Currawong Press |year=1982}}</ref> Also in 1836, the schooner ''Emily'' ran aground with the Dutch fisherman Pieter Groen from [[Katwijk]]. He stayed, married there, changed his name to Peter Green and in 1865 became spokesman/governor of the community. In 1856, there were already 97 people living there.{{Citation needed|date=October 2023}} |

|||

Whalers set up bases on the islands for operations in the Southern Atlantic. However, the opening of the [[Suez Canal]] in 1869, together with the gradual transition from sailing ships to coal-fired steam ships, increased the isolation of the islands, which were no longer needed as a stopping port for lengthy sail voyages, or for shelter for journeys from Europe to East Asia.<ref name=mackay/> A parson arrived in February 1851, the Bishop of Cape Town visited in March 1856 and the island was included within the diocese of Cape Town.<ref>Jan Brander, ''Tristan da Cunha, 1506-1902,'' London, Unwin, 1940</ref>{{rp|63–50}} |

|||

A [[parson]] arrived in February 1851, the Bishop of Cape Town visited in March 1856 and the island was included within the diocese of Cape Town.<ref>Jan Brander, ''Tristan da Cunha, 1506–1902,'' London, Unwin, 1940</ref>{{rp|63–50}} |

|||

In 1867, [[Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha|Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh]] and second son of [[Queen Victoria]], visited the islands. The main settlement, [[Edinburgh of the Seven Seas]], was named in honour of his visit.{{efn|The visit took place during the Duke of Edinburgh's [[circumnavigation]] undertaken while commanding HMS ''Galatea''. Tristan da Cunha post office issued four stamps in 1967 to celebrate the centenary of this visit.<ref>{{cite book |author=Courtney, Nicholas |year=2004 |title=The Queen's Stamps |isbn=0-413-77228-4 |page=28}}</ref>}} On 15 October 1873, the Royal Navy scientific survey vessel [[HMS Challenger (1858)|HMS ''Challenger'']] docked at Tristan to conduct geographic and zoological surveys on Tristan, [[Inaccessible Island]] and the [[Nightingale Islands]].<ref name=thomson>{{cite book |last= Thomson |first=C. Wyville |year= 1885 |title= Report on the Scientific Results of the Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger During the Years 1873–76 |location=London, UK |publisher=Her Majesty's Stationery Office |pages=240–252 |url=https://archive.org/details/reportonscientif02grearich/page/240 |access-date=28 December 2018}}</ref> In his log, Captain [[George Nares]] recorded a total of fifteen families and eighty-six individuals living on the island.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.foraminifera.eu/challenger135.php= |title=H.M.S. Challenger Station 135, Tristan da Cunha |accessdate=29 August 2016 |url-status=dead |archive-date=10 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200810133104/http://www.foraminifera.eu/challenger135.php= }}</ref> Tristan became a dependency of the British Crown in October 1875.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-14123532 |title=St. Helena, Ascension, Tristan da Cunha profiles |date=2018-05-14 |access-date=2020-01-12 |df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

|||

In 1867, [[Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha|Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh]] and second son of [[Queen Victoria]], visited the islands. The only settlement, [[Edinburgh of the Seven Seas]], was named in honour of his visit.{{efn|The visit took place during the Duke of Edinburgh's [[circumnavigation]] undertaken while commanding HMS ''Galatea''. Tristan da Cunha post office issued four stamps in 1967 to celebrate the centenary of this visit.<ref>{{cite book |author=Courtney, Nicholas |year=2004 |title=The Queen's Stamps |isbn=0-413-77228-4 |page=28 |publisher=Methuen}}</ref>}} On 15 October 1873, the Royal Navy scientific survey vessel [[HMS Challenger (1858)|HMS ''Challenger'']] docked at Tristan to conduct geographic and zoological surveys on Tristan, [[Inaccessible Island]] and the [[Nightingale Islands]].<ref name=thomson>{{cite book |last=Thomson |first=C. Wyville |year=1885 |title=Report on the Scientific Results of the Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger During the Years 1873–76 |location=London |publisher=Her Majesty's Stationery Office |pages=240–252 |url=https://archive.org/details/reportonscientif02grearich/page/240 |access-date=28 December 2018}}</ref> In his log, Captain [[George Nares]] recorded a total of fifteen families and eighty-six individuals living on the island.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.foraminifera.eu/challenger135.php |title=H.M.S. Challenger Station 135, Tristan da Cunha |access-date=29 August 2016 |url-status=dead |archive-date=14 December 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181214141940/http://foraminifera.eu/challenger135.php}}</ref> Tristan became a dependency of the British Crown in October 1875.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-14123532 |title=St. Helena, Ascension, Tristan da Cunha profiles |date=14 May 2018 |access-date=12 January 2020 |archive-date=17 March 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190317092054/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-14123532 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

Whalers set up bases on the islands for operations in the Southern Atlantic. However, the opening of the [[Suez Canal]] in 1869, together with the gradual transition from sailing ships to coal-fired steam ships, increased the isolation of the islands, which were no longer needed as a stopping port for lengthy sail voyages, or for shelter for journeys from Europe to East Asia.<ref name=mackay/> |

|||

{{Main article|Tristan da Cunha lifeboat disaster}} |

|||

{{Quote box |

|||

| quote = |

|||

Victims of the 1885 Lifeboat disaster: |

|||

* Joe Beetham |

|||

* Thomas & Cornelius Cotton |

|||

* Thomas Glass |

|||

* John, William & Alfred Green |

|||

* Jacob, William & Jeremiah Green |

|||

* Albert, James & William Hagan |

|||

* Samuel & Thomas Swain |

|||

| align = left |

|||

| width = 15% |

|||

}} |

|||

On 27 November 1885, the island suffered one of its worst tragedies after an iron [[barque]] named ''West Riding'' approached the island, whilst en route to [[Sydney]], Australia, from [[Bristol]].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Millington |first=Peter |title=The Lifeboat Disaster |url=https://www.tristandc.com/po/stamps201512.php |url-status=dead |access-date=18 April 2021 |publisher=Tristan da Cunha Government & Tristan da Cunha Association |archive-date=4 June 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190604195332/https://tristandc.com/po/stamps201512.php}}</ref> Due to the loss of regular trading opportunities, almost all of the island's able-bodied men approached the ship in a [[Lifeboat (rescue)|lifeboat]] attempting to trade with the passing vessel. The boat, recently donated by the British government, sailed despite rough waters and, although the lifeboat was spotted sailing alongside the ship for some time, it never returned. Various reports were given following the event, with rumours ranging from the men drowning,<ref>{{Cite web |last=Grundy |first=Richard |title=Tristan da Cunha Isolation & Hardship 1853–1942 |url=https://www.tristandc.com/history1853-1942.php |date=9 November 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210227075753/https://www.tristandc.com/history1853-1942.php |archive-date=27 February 2021 |access-date=18 April 2021 |publisher=Tristan da Cunha Government & Tristan da Cunha Association}}</ref> to reports of them being taken to Australia and sold as slaves.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Millington |first=Peter |title=The Lifeboat Disaster |url=https://www.tristandc.com/po/stamps201512.php |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151124234904/http://www.tristandc.com/po/stamps201512.php |url-status=dead |archive-date=24 November 2015 |access-date=18 April 2021 |website=www.tristandc.com |language=en-GB}}</ref> In total, 15 men were lost, leaving behind an island of widows. A plaque at [[St. Mary's Church, Edinburgh of the Seven Seas|St. Mary's Church]] commemorates the lost men.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Glass |first=Conrad |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=90yYAgAAQBAJ&q=tristan+st+marys+plaque+lifeboat&pg=PT143 |title=Rockhopper Copper |date=2014 |publisher=Polperro Heritage Press |isbn=978-0-9530012-3-1 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

===20th century=== |

===20th century=== |

||

After years of hardship since the 1880s and an especially difficult winter in 1906, the British government offered to evacuate the island in 1907. The Tristanians held a meeting and decided to refuse, despite the crown's warning that it could not promise further help in the future.<ref name="annals"/>{{page number|date=August 2020}} No ships called at the islands from 1909 until 1919, when [[HMS Yarmouth (1911)|HMS ''Yarmouth'']] finally stopped to inform the islanders of the outcome of [[World War I]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Tristan da Cunha Isolation & Hardship 1853–1942|url=http://www.tristandc.com/history1853-1942.php|publisher=Tristan da Cunha Government & Tristan da Cunha Association|accessdate=1 January 2019|df=dmy-all}}</ref> The [[Shackleton–Rowett Expedition]] stopped in Tristan for five days in May 1922, collecting geological and botanical samples before returning to [[Cape Town]].<ref name="annals"/>{{page number|date=August 2020}} Among the few ships that visited in the coming years were the [[RMS Asturias (1925)|RMS ''Asturias'']], a [[Royal Mail Steam Packet Company]] passenger liner, in 1927, and the ocean liners [[RMS Empress of France (1928)|RMS ''Empress of France'']] in 1928,<ref name="Stamps">{{cite web|url=http://www.tristandc.com/po/stamps201517.php|website=Tristan da Cunha|title=Tristan da Cunha Stamps|date=8 December 2015|access-date=2 January 2019}}</ref> {{RMS|Duchess of Atholl}} in 1929,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tristandc.com/news-2018-11-12-eBay-slides.php|website=Tristan da Cunha|title=Tristan da Cunha News: 1920s Lantern Slides of Tristan for Sale on eBay|last=Millington|first=Peter|access-date=2 January 2019}}</ref> and [[RMS Empress of Australia (1919)|RMS ''Empress of Australia'']] in 1935.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.shippingtandy.com/features/tristan-da-cunha/|website=Shipping Today & Yesterday Magazine|title=Tristan Da Cunha|last=Lawrence|first=Nigel|date=8 August 2017|access-date=2 January 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.kelleherauctions.com/php/chap_auc.php?site=1&lang=1&sale=4010&chapter=84&page=1|website=Daniel F. Kelleher Auctions LLC|title=Sale 4010 - Web/Internet - Outgoing Ship Mail|access-date=2 January 2019}}</ref> In 1936, ''[[The Daily Telegraph]]'' of London reported the population of the island was 167 people, with 185 cattle and 42 horses.<ref name=ken>{{cite book |last=Wollenberg |first=Ken |year=2000 |title=The Bottom of the Map |location=Bloomington, Indiana |publisher=Xlibris |chapter=Chapter XI: Tristan da Cunha |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HQOLAAAAQBAJ |access-date=28 December 2018|isbn=9781453565759 }}{{self-published source|date=December 2018}}</ref>{{Self-published inline|certain=yes|date=December 2018}} |

|||

====Hard winter of 1906==== |

|||

From December 1937 to March 1938, a [[Norway|Norwegian]] party made [[Norwegian Scientific Expedition to Tristan Da Cunha 1937-1938|a dedicated scientific expedition]] to Tristan da Cunha, and sociologist [[Peter A. Munch]] extensively documented island culture — he would later revisit the island in 1964–1965.<ref>{{cite web |title=Results of the Norwegian Scientific Expedition to Tristan da Cunha, 1937–1938 |year=1945 |url=http://otago.ourheritage.ac.nz/items/show/8301 |website=OUR Heritage |publisher=University of Otago |access-date=3 June 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150929002730/http://otago.ourheritage.ac.nz/items/show/8301 |archive-date=29 September 2015 |url-status=live |df=dmy-all}}</ref> The island was also visited in 1938 by [[W. Robert Foran]], reporting for the [[National Geographic Society]].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/digital-nomad/2011/04/22/holy-grail/ |website=National Geographic |title=Holy Grail |last=Evans |first=Andrew |date=22 April 2011 |access-date=2 January 2019}}</ref> [[W. Robert Foran|Foran's]] account was published that same year.<ref>{{cite magazine |author=Foran, W. Robert |author-link=W. Robert Foran |title=Tristan da Cunha, Isles of Contentment |magazine=National Geographic |date=November 1938 |pages=671–694}}</ref> On 12 January 1938 by [[letters patent]], Britain declared the islands a dependency of [[Saint Helena]], creating the [[Crown colony|British Crown Colony]] of [[Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha|Saint Helena and Dependencies]], which also included [[Ascension Island]].<ref>{{cite news |url=http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F50716FC355B107A93C6AB1788D85F418385F9&scp=4&sq=R.M.S.%20and%20Canadian%20Pacific&st=cse |title=Royal Gifts Gladden 172 on Lonely Atlantic Island |newspaper=[[The New York Times]] |place=New York, NY |at=second news section, p. N4 |date=24 March 1935 |access-date=15 October 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120127204633/http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F50716FC355B107A93C6AB1788D85F418385F9&scp=4&sq=R.M.S.%20and%20Canadian%20Pacific&st=cse |archive-date=27 January 2012 |url-status=live |df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

|||

After years of hardship since the 1880s and an especially difficult winter in 1906, the British government offered to evacuate the island in 1907. The Tristanians held a meeting and decided to refuse, despite the government's warning that it could not promise further help in the future.<ref name=annals |page=55/> |

|||

====Occasional pre-war visits==== |

|||

No ships called at the islands from 1909 until 1919, when [[HMS Yarmouth (1911)|HMS ''Yarmouth'']] stopped to inform the islanders of the outcome of [[World War I]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Tristan da Cunha Isolation & Hardship 1853–1942 |website=Tristan da Cunha |publisher=Tristan da Cunha Government & Tristan da Cunha Association |url=http://www.tristandc.com/history1853-1942.php |access-date=1 January 2019 |archive-date=15 January 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190115092129/http://www.tristandc.com/history1853-1942.php |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

The [[Shackleton–Rowett Expedition]] stopped in Tristan for five days in May 1922, collecting geological and botanical samples before returning to [[Cape Town]].<ref>{{cite book |url=http://www.tristan.it/TRISTAN/tristanlibri/tristan_annals.pdf |first1=Arnaldo |last1=Faustini |title=The Annals of Tristan da Cunha |date=14 September 2003 |access-date=18 February 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150510041635/http://www.tristan.it/TRISTAN/tristanlibri/tristan_annals.pdf |archive-date=10 May 2015 |url-status=live |editor1-first=Paul |editor1-last=Carrol |translator1-first=Liz |translator1-last=Nysven |translator2-first=Larry |translator2-last=Conrad |page=58}}</ref> Among the few ships that visited in the coming years were the [[RMS Asturias (1925)|RMS ''Asturias'']], a [[Royal Mail Steam Packet Company]] passenger liner, in 1927, and the [[CP_Ships|Canadian Pacific]] ocean liners [[RMS Empress of France (1928)|RMS ''Empress of France'']] in 1928,<ref name=Stamps>{{cite web |title=Tristan da Cunha Stamps |date=8 December 2015 |website=Tristan da Cunha |publisher=Tristan da Cunha Government & Tristan da Cunha Association |url=http://www.tristandc.com/po/stamps201517.php |access-date=2 January 2019 |archive-date=1 December 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211201123718/https://tristandc.com/po/stamps201517.php |url-status=live }}</ref> {{RMS|Duchess of Atholl}} in 1929,<ref>{{cite web |last=Millington |first=Peter |date=12 November 2018 |title=Tristan da Cunha News: 1920s Lantern Slides of Tristan for Sale on eBay |website=Tristan da Cunha |url=http://www.tristandc.com/news-2018-11-12-eBay-slides.php |access-date=2 January 2019 |archive-date=27 February 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210227095052/https://www.tristandc.com/news-2018-11-12-eBay-slides.php |url-status=live }}</ref> and [[RMS Empress of Australia (1919)|RMS ''Empress of Australia'']] in 1935.<ref>{{cite magazine |last=Lawrence |first=Nigel |date=8 August 2017 |title=Tristan da Cunha |magazine=Shipping Today & Yesterday Magazine |url=https://www.shippingtandy.com/features/tristan-da-cunha/ |access-date=2 January 2019 |archive-date=31 March 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220331232121/https://www.shippingtandy.com/features/tristan-da-cunha/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Outgoing Ship Mail |id=Sale 4010 – Web / Internet |publisher=Daniel F. Kelleher Auctions LLC |url=http://www.kelleherauctions.com/php/chap_auc.php?site=1&lang=1&sale=4010&chapter=84&page=1 |access-date=2 January 2019 |archive-date=16 January 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190116100452/http://www.kelleherauctions.com/php/chap_auc.php?site=1&lang=1&sale=4010&chapter=84&page=1 |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

In 1936, ''[[The Daily Telegraph]]'' of London reported that the population of the island was 167 people, with 185 cattle and 42 horses.<ref name=ken>{{cite book |last=Wollenberg |first=Ken |year=2000 |title=The Bottom of the Map |location=Bloomington, Indiana |publisher=Xlibris |chapter=Chapter XI: Tristan da Cunha |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HQOLAAAAQBAJ |access-date=28 December 2018 |isbn=9781453565759}}{{self-published source|date=December 2018}}</ref>{{Self-published inline|certain=yes|date=December 2018}} |

|||

From December 1937 to March 1938, a [[Norway|Norwegian]] party made [[Norwegian Scientific Expedition to Tristan Da Cunha 1937-1938|a dedicated scientific expedition]] to Tristan da Cunha, and sociologist [[Peter A. Munch]] extensively documented island culture; he visited the island again in 1964–1965.<ref>{{cite web |title=Results of the Norwegian scientific expedition to Tristan da Cunha, 1937–1938 |year=1945 |url=http://otago.ourheritage.ac.nz/items/show/8301 |website=Our Heritage |publisher=University of Otago |access-date=3 June 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150929002730/http://otago.ourheritage.ac.nz/items/show/8301 |archive-date=29 September 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref> The island was also visited in 1938 by [[W. Robert Foran]], reporting for the [[National Geographic Society]].<ref>{{cite magazine |last=Evans |first=Andrew |date=22 April 2011 |magazine=[[National Geographic (magazine)|National Geographic]] |title=Holy Grail |series=Travel |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/digital-nomad/2011/04/22/holy-grail/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190116100352/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/digital-nomad/2011/04/22/holy-grail/ |url-status=dead |archive-date=16 January 2019 |access-date=2 January 2019}}</ref> His account was published that same year.<ref>{{cite magazine |author=Foran, W.R. |author-link=W. Robert Foran |date=November 1938 |title=Tristan da Cunha, isles of contentment |magazine=[[National Geographic (magazine)|National Geographic]] |pages=671–694}}</ref> |

|||

On 12 January 1938 by [[letters patent]], Britain declared the islands a dependency of [[Saint Helena]], creating the [[Crown colony|British Crown Colony]] of [[Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha|Saint Helena and Dependencies]], which also included [[Ascension Island]].<ref>{{cite news |title=Royal gifts gladden 172 on lonely Atlantic island |date=24 March 1935 |newspaper=[[The New York Times]] |place=New York |at=second news section, p. N4 |url=http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F50716FC355B107A93C6AB1788D85F418385F9&scp=4&sq=R.M.S.%20and%20Canadian%20Pacific&st=cse |url-status=live |access-date=15 October 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120127204633/http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F50716FC355B107A93C6AB1788D85F418385F9&scp=4&sq=R.M.S.%20and%20Canadian%20Pacific&st=cse |archive-date=27 January 2012}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Gough and Inaccessible Islands-113067.jpg|thumb|[[Gough and Inaccessible Islands]] are a [[UNESCO]] [[World Heritage Site]].]] |

[[File:Gough and Inaccessible Islands-113067.jpg|thumb|[[Gough and Inaccessible Islands]] are a [[UNESCO]] [[World Heritage Site]].]] |

||

====World War II military development==== |

|||

During the [[Second World War]], Tristan was commissioned by the [[Royal Navy]] as the [[stone frigate]] {{HMS|Atlantic Isle}} and used as a secret [[signals intelligence]] station to monitor [[Nazi Germany|Nazi]] [[U-boat]]s (which were required to maintain radio contact) and shipping movements in the South [[Atlantic Ocean]]. This weather and radio station led to extensive new infrastructure being built on the island, including a school, a hospital, and a cash-based general store. The first colonial official sent to rule the island was [[Sir Hugh Elliott]] in the rank of Administrator (because the settlement was too small to merit a Governor) 1950-53. Development continued as the island's first canning factory expanded paid employment in 1949.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Tristan da Cunha Joining the Modern World 1942–1961|website=Tristan da Cunha|url=http://www.tristandc.com/history1942-1961.php|access-date=28 December 2018}}</ref> [[Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh]], [[Queen Elizabeth II|the Queen's]] [[Prince consort|consort]], visited the islands in 1957 as part of a world tour on board the royal yacht [[HMY Britannia|HMY ''Britannia'']].<ref>{{cite web |title=hrh the duke of edinburgh's antarctic tour. january 1957 |url=https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205164053 |publisher=Imperial War Museum |accessdate=2 July 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180702150756/https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205164053 |archive-date=2 July 2018 |url-status=live |df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

|||

During the [[Second World War]], Tristan was commissioned by the [[Royal Navy]] as the so-called "[[stone frigate]]" {{HMS|Atlantic Isle}} and used as a secret [[signals intelligence]] station, to monitor [[Germany|German]] [[U-boat]]s (which were required to maintain radio contact) and shipping in the South [[Atlantic Ocean]]. The weather and radio stations led to extensive new infrastructure being built on the island, including a school, a hospital, and a cash-based general store.<ref name=joining/> |

|||

The first colonial official sent to rule the island was [[Sir Hugh Elliott]] in the rank of administrator (because the settlement was too small to merit a governor) 1950–1953.{{Citation needed|date=August 2024}} Development continued as the island's first canning factory expanded paid employment in 1949.<ref name=joining>{{cite web |title=Tristan da Cunha joining the modern world 1942–1961 |website=Tristan da Cunha |url=http://www.tristandc.com/history1942-1961.php |access-date=28 December 2018 |archive-date=15 January 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190115092758/http://www.tristandc.com/history1942-1961.php |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

====Rare post-war ship visits==== |

|||

[[Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh]], [[Elizabeth II|the Queen's]] [[Prince consort|consort]], visited the islands in 1957 as part of a world tour on board the royal yacht [[HMY Britannia|HMY ''Britannia'']].<ref>{{cite web |title=H.R.H. the Duke of Edinburgh's Antarctic tour. January 1957 |publisher=Imperial War Museum |url=https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205164053 |access-date=2 July 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180702150756/https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205164053 |archive-date=2 July 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

On 2 January 1954, Tristan da Cunha was visited by the Dutch ship ''[[MS Achille Lauro|Willem Ruys]]'', a [[passenger-cargo liner]],<ref>{{cite web |title=Single ship report |id=5302635 |website=Miramar Ship Index |publisher=R.B. Haworth |location=Wellington, NZ |url=https://www.miramarshipindex.nz/ship/5302635 |access-date=22 December 2020 |url-access=subscription}}</ref> carrying science fiction writer [[Robert A. Heinlein]], his wife Ginny and other passengers. The ''Ruys'' was travelling from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to Cape Town, South Africa. The visit is described in Heinlein's book ''[[Tramp Royale]]''. The captain told Heinlein the island was the most isolated inhabited spot on Earth and ships rarely visited. Heinlein mailed a letter from there to [[L. Ron Hubbard]], a friend who also liked to travel, "for the curiosity value of the postmark". Biographer William H. Patterson, Jr. in his two volume ''Robert A. Heinlein In Dialogue with his Century'', wrote that lack of "cultural context" made it "nearly impossible to converse" with the islanders, "a stark contrast with the way they had managed to chat with strangers" while travelling in South America. Members of the crew bought penguins during their brief visit to the island.{{Citation needed|date=October 2023}} |

|||

====1961 eruption of Queen Mary's Peak==== |

|||

On 10 October 1961, the eruption of a [[parasitic cone]] of [[Queen Mary's Peak]], very close to Edinburgh of the Seven Seas, forced evacuation of all 264 people.<ref>{{cite gvp |name=Tristan da Cunha |vn=386010 |access-date=25 June 2021}}</ref><ref name=travel>{{cite web |title=A voyage to Tristan da Cunha |url=http://oxhc.co.uk/A-Voyage-to-Tristan.asp |access-date=29 August 2016 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160911070030/http://oxhc.co.uk/A-Voyage-to-Tristan.asp |archive-date=11 September 2016}}</ref> The evacuees took to the water in open boats, taken by the local lobster-fishing boats ''Tristania'' and ''Frances Repetto'' to uninhabited [[Nightingale Island]].<ref name=Life>{{cite magazine |last=Griggs |first=Lee |date=10 November 1961 |title=Violent end for a lonely island |magazine=[[Life (magazine)|Life]] |volume=51 |issue=19 |pages=21–22 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4VMEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA21 |access-date=31 October 2020}}</ref> |

|||

The next day, they were picked up by the diverted Dutch passenger ship ''Tjisadane'' that took them to [[Cape Town]].<ref name=Life/> The islanders later arrived in the U.K. aboard the liner [[MV Stirling Castle|M.V. ''Stirling Castle'']] to a big press reception and, after a short period at Pendell Army Camp in [[Merstham]], [[Surrey]], were settled in an old [[Royal Air Force]] camp near [[Calshot]], [[Hampshire]].<ref name=travel/><ref name=BDP04111961>{{cite news |title=Refugees from Tristan |date=4 November 1961 |newspaper=[[Birmingham Daily Post]] |issue=32151 |page=26 |via=British Newspaper Archive |url=https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002134/19611104/625/0026 |access-date=1 November 2020 |url-access=subscription}}</ref> |

|||

The following year, a [[Royal Society]] expedition reported that Edinburgh of the Seven Seas had survived. Most families returned in 1963.<ref>{{cite magazine |last=Gila |first=Oscar Alvarez |title=Refugees for the media, evacuees for the government: The 1961 Tristan da Cunha volcano eruption and its displaced inhabitants |magazine=Global Change and Resilience |place=Brno, Czech Republic |url=https://www.academia.edu/5748318}}{{Dead link|date=December 2021 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> |

|||

====Gough and Inaccessible Islands wildlife reserves==== |

|||

On 2 January 1954, Tristan da Cunha was visited by the Dutch ship ''Ruys'', a [[passenger-cargo liner]],<ref>{{cite web |title=Single Ship Report for "5302635" |url=https://www.miramarshipindex.nz/ship/5302635 |website=Miramar Ship Index (subscription)|publisher=R B Haworth |access-date=22 December 2020 |location=Wellington, New Zealand}}</ref> carrying science fiction writer [[Robert A. Heinlein|Robert A Heinlein]], his wife Ginny and other passengers. The ''Ruys'' was travelling from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to Cape Town, South Africa. The visit is described in Heinlein's book "''[[Tramp Royale]]''". The captain told Heinlein the island was the most isolated inhabited spot on Earth and ships rarely visited. Heinlein mailed a letter there to [[L. Ron Hubbard]], a friend who also liked to travel, "for the curiosity value of the postmark." Biographer William H Patterson, Jr. in his two volume "''Robert A Heinlein In Dialogue with his Century''," wrote that lack of "cultural context" made it "nearly impossible to converse" with the islanders, "a stark contrast with the way they had managed to chat with strangers" while travelling in South America. Members of the crew bought penguins during their brief visit to the island. |

|||

[[File:Cleaning oil off penguins after the spillage from the MS Oliva, Tristan da Cunha (7413022602).jpg|thumb|Cleaning oil off penguins after the spillage from the MS ''Oliva'', Tristan da Cunha ]] |

|||

[[Gough Island]] was inscribed as a [[UNESCO]] [[World Heritage Site]] in 1995 as Gough Island Wildlife Reserve.<ref>{{cite web |title=UNESCO Committee Decision |year=2004 |id=28COM 14B.17 |url=https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/100 |access-date=12 February 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190103004930/https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/100 |archive-date=3 January 2019}}</ref> This was further extended in 2004 as [[Gough and Inaccessible Islands]], with its marine zone extended from 3 to 12 nautical miles. |

|||

On 10 October 1961, the eruption of [[Queen Mary's Peak]] forced the evacuation of the entire population of 264 individuals.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://volcano.si.edu/volcano.cfm?vn=386010 |website=Global Volcanism Program |title=Tristan da Cunha |publisher=[[Smithsonian Institution]] |accessdate=28 December 2018}}</ref><ref name=travel>{{cite web |url=http://oxhc.co.uk/A-Voyage-to-Tristan.asp |title=Travel Tristan da Cunha |access-date=29 August 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160911070030/http://oxhc.co.uk/A-Voyage-to-Tristan.asp |archive-date=11 September 2016 |url-status=dead |df=dmy-all }}</ref> The evacuees took to the water in open boats and were taken by the local lobster-fishing boats ''Tristania'' and ''Frances Repetto'' to uninhabited [[Nightingale Island]].<ref name="Life">{{cite news |last1=Griggs |first1=Lee |title=Violent End for a Lonely Island |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4VMEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA21 |accessdate=31 October 2020 |work=[[Life (magazine)|Life]] |issue=Vol.51, No.19 |date=10 November 1961 |pages=21–22}}</ref> The following day they were picked up by the diverted Dutch passenger ship ''Tjisadane'' that took them to [[Cape Town]].<ref name=Time/> The islanders later arrived in the UK aboard the liner [[MV Stirling Castle|''Stirling Castle'']] to a big press reception and, after a short period at Pendell Army Camp in [[Merstham]], [[Surrey]], were settled in an old [[Royal Air Force]] camp near [[Calshot]], [[Hampshire]].<ref name="travel"/><ref name="BDP04111961">{{cite news |title=Refugees from Tristan |url=https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002134/19611104/625/0026 |accessdate=1 November 2020 |work=Birmingham Daily Post |issue=32151 |publisher=British Newspaper Archive (subscription) |date=4 November 1961 |page=26}}</ref> The following year a [[Royal Society]] expedition reported that Edinburgh of the Seven Seas had survived the eruption. Most families returned in 1963.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Gila |first=Oscar Alvarez |url=https://www.academia.edu/5748318 |title=Refugees for the media, evacuees for the government: The 1961 Tristan da Cunha volcano eruption and its displaced inhabitants |journal=Global Change and Resilience: From Impacts to Responses |place=Brno, Czech Republic}}</ref> |

|||

These islands have been [[Ramsar site]]s – wetlands of international importance – since 20 November 2008.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Gough Island |website=[[Ramsar Convention|Ramsar]] Sites Information Service |url=https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/1868 |access-date=25 April 2018 |archive-date=30 May 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180530035352/https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/1868 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Inaccessible Island |website=[[Ramsar Convention|Ramsar]] Sites Information Service |url=https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/1869 |access-date=25 April 2018 |archive-date=7 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220407015327/https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/1869 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

===21st century=== |

===21st century=== |

||

[[File:Tristan da Cunha, British overseas territory-20March2012.jpg|thumb|Tristan da Cunha in 2012]] |

[[File:Tristan da Cunha, British overseas territory-20March2012.jpg|thumb|Tristan da Cunha in 2012]] |

||

On 23 May 2001, the islands were hit by an [[extratropical cyclone]] that generated winds up to {{convert|120|mph|kph|order=flip}}. A number of structures were severely damaged, and numerous cattle were killed, prompting emergency aid provided by the British government.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/1311749/120-mph-storm-devastates-Tristan-da-Cunha.html |location=London, UK |work=The Daily Telegraph |first=Sandra |last=Barwick |title=120 mph storm devastates Tristan da Cunha |date=7 June 2001 |access-date=4 April 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180522131515/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/1311749/120-mph-storm-devastates-Tristan-da-Cunha.html |archive-date=22 May 2018 |url-status=live |df=dmy-all }}</ref> In 2005, the islands were given a United Kingdom [[post code]] (TDCU 1ZZ), to make it easier for the residents to order goods online.<ref>{{Cite news|date=2005-08-07|title=First postcode for remote UK isle|language=en-GB|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/4129636.stm|access-date=2020-06-11}}</ref> |

|||

On 23 May 2001, the islands were hit by an [[extratropical cyclone]] that generated winds up to {{convert|120|mph|kph|order=flip}}. A number of structures were severely damaged, and numerous cattle were killed, prompting emergency aid provided by the British government.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/1311749/120-mph-storm-devastates-Tristan-da-Cunha.html |location=London |work=The Daily Telegraph |first=Sandra |last=Barwick |title=120 mph storm devastates Tristan da Cunha |date=7 June 2001 |access-date=4 April 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180522131515/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/1311749/120-mph-storm-devastates-Tristan-da-Cunha.html |archive-date=22 May 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

On 13 February 2008, a fire destroyed the island's four power generators and fish canning factory, severely disrupting the economy. On 14 March 2008, new generators were installed and power restored, and a new factory opened in July 2009. While the replacement factory was built, [[MY Titanic|M/V ''Kelso'']] came to the island as a [[factory ship]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Factory Fire on 13 February 2008 |publisher=The Tristan da Cunha Website |url=http://www.tristandc.com/newsfactoryfire.php |accessdate=5 January 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Building a 21st century Tristan fishing factory |publisher=The Tristan da Cunha website |url=http://www.tristandc.com/newsfishfactorybuilding.php |accessdate=5 January 2019}}</ref> The St. Helena, Ascension, and Tristan da Cunha Constitution Order 2009 reorganized Tristan da Cunha as a constituent of the new British Overseas Territory of [[Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha]], giving Tristan and Ascension equal status with Saint Helena.<ref name="Constitution"/> |

|||

In 2005, the islands were given a United Kingdom [[post code]] (TDCU 1ZZ), to make it easier for the residents to order goods online.<ref>{{Cite news |date=7 August 2005 |title=First postcode for remote UK isle |language=en-GB |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/4129636.stm |access-date=11 June 2020 |archive-date=11 June 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200611064747/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/4129636.stm |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

On |

On 13 February 2008, a fire destroyed the island's four power generators and fish canning factory, severely disrupting the economy. On 14 March 2008, new generators were installed and power restored, and a new factory opened in July 2009. While the replacement factory was built, [[MY Titanic|M/V ''Kelso'']] came to the island as a [[factory ship]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Factory Fire on 13 February 2008 |publisher=The Tristan da Cunha Website |url=http://www.tristandc.com/newsfactoryfire.php |access-date=5 January 2019 |archive-date=8 March 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220308101526/https://www.tristandc.com/newsfactoryfire.php |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Building a 21st century Tristan fishing factory |publisher=The Tristan da Cunha website |url=http://www.tristandc.com/newsfishfactorybuilding.php |access-date=5 January 2019 |archive-date=18 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220818012229/https://www.tristandc.com/newsfishfactorybuilding.php |url-status=live }}</ref> The St. Helena, Ascension, and Tristan da Cunha Constitution Order 2009 reorganized Tristan da Cunha as a constituent of the new British Overseas Territory of [[Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha]], giving Tristan and Ascension equal status with Saint Helena.<ref name="Constitution"/> |

||

On 16 March 2011, the freighter {{Ship|MS|Oliva|}} ran aground on [[Nightingale Island]], spilling tons of heavy fuel oil into the ocean. The resulting oil slick threatened the island's population of [[rockhopper penguin]]s.<ref>{{cite web |title=MS Oliva runs aground on Nightingale Island |publisher=The Tristan da Cunha Website |url=http://www.tristandc.com/newsmsoliva.php |access-date=23 March 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110525021810/http://www.tristandc.com/newsmsoliva.php |archive-date=25 May 2011 |url-status=dead}}</ref> Nightingale Island has no fresh water, so the penguins were transported to Tristan da Cunha for cleaning.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/earth/hi/earth_news/newsid_9438000/9438609.stm |work=BBC News |title=Oil-soaked rockhopper penguins in rehabilitation |access-date=28 March 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130903053051/http://news.bbc.co.uk/earth/hi/earth_news/newsid_9438000/9438609.stm |archive-date=3 September 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

A total [[solar eclipse]] will pass over the island [[Solar eclipse of December 5, 2048|on 5 December 2048]]. The island is calculated to be on the centre line of the umbra's path for nearly three and a half minutes of totality.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/SEsearch/SEsearchmap.php?Ecl=20481205 |title=Total Solar Eclipse of 2048 December 05 |publisher=Eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov |accessdate=11 January 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140111022252/http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/SEsearch/SEsearchmap.php?Ecl=20481205 |archive-date=11 January 2014 |url-status=live |df=dmy-all }}</ref> |

|||

On 13 November 2020 it was announced that the {{convert|687247|km2|sqmi}} of the waters surrounding the islands will become a [[Marine protected area|Marine Protection Zone]]. The move will make the zone the largest no-take zone in the Atlantic and the fourth largest on the planet. The move follows 20 years of conservation work by the [[RSPB]] and the island government and five years of the UK government's Blue Belt programme support.<ref>{{cite web |first1=Richard |last1=Grundy |access-date=13 November 2020 |title=Tristan's Marine Protection Zone Announced |url=https://www.tristandc.com/government/news-2020-11-12-mpzgov13nov2020.php |website=www.tristandc.com |archive-date=13 November 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201113043130/https://www.tristandc.com/government/news-2020-11-12-mpzgov13nov2020.php |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |access-date=13 November 2020 |title=UK Overseas Territory becomes one of the world's biggest sanctuaries for wildlife |url=https://www.rspb.org.uk/about-the-rspb/about-us/media-centre/press-releases/tristan-da-cunha-mpa/ |website=The RSPB |archive-date=13 November 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201113075133/https://www.rspb.org.uk/about-the-rspb/about-us/media-centre/press-releases/tristan-da-cunha-mpa/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

On 13 November 2020 it was announced that the {{convert|687247|km2|sqmi}} of the waters surrounding the islands will become a [[Marine protected area|Marine Protection Zone]]. The move will make the zone |

|||

the largest no-take zone in the Atlantic and the fourth largest on the planet. The move follows 20 years of conservation work by the [[RSPB]] and the island government and five years of the UK government's Blue Belt program support.<ref>{{cite web|first1=Richard|last1=Grundy|accessdate=2020-11-13|title=Tristan's Marine Protection Zone Announced|url=https://www.tristandc.com/government/news-2020-11-12-mpzgov13nov2020.php|website=www.tristandc.com}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|accessdate=2020-11-13|title=UK Overseas Territory becomes one of the world's biggest sanctuaries for wildlife|url=https://www.rspb.org.uk/about-the-rspb/about-us/media-centre/press-releases/tristan-da-cunha-mpa/|website=The RSPB}}</ref> |

|||

A total [[solar eclipse]] will pass over the island [[Solar eclipse of December 5, 2048|on 5 December 2048]]. The island is calculated to be on the centre line of the umbra's path for nearly three and a half minutes of totality.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/SEsearch/SEsearchmap.php?Ecl=20481205 |title=Total Solar Eclipse of 2048 December 05 |publisher=Eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov |access-date=11 January 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140111022252/http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/SEsearch/SEsearchmap.php?Ecl=20481205 |archive-date=11 January 2014 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Settlement on Tristan (7089086383).jpg|thumb|725x725px|[[Edinburgh of the Seven Seas|Edinburgh of The Seven Seas]], the only settlement on the island. The parasitic cone from the 1961 eruption can be seen in the foreground, centre left.]] |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

==Geography== |

==Geography== |

||

| Line 219: | Line 251: | ||

[[File:Gough island top view.png|thumb|[[Gough Island]], Tristan da Cunha]] |

[[File:Gough island top view.png|thumb|[[Gough Island]], Tristan da Cunha]] |

||

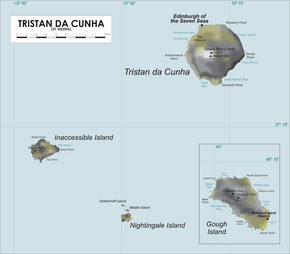

Tristan da Cunha is thought to have been formed by a long-lived centre of upwelling mantle called the [[Tristan hotspot]]. Tristan da Cunha is the main island of the Tristan da Cunha [[archipelago]], which consists of the following islands: |

Tristan da Cunha is thought to have been formed by a long-lived centre of upwelling mantle called the [[Tristan hotspot]]. Tristan da Cunha is the main island of the Tristan da Cunha [[archipelago]], which consists of the following islands:{{Citation needed|date=October 2023}} |

||

* Tristan da Cunha, the main and largest island, area: {{convert|98|km2|sqmi|1}}<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.thoughtco.com/tristan-da-cunha-1435571|website=ThoughtCo|title=Tristan da Cunha|last=Rosenberg|first=Mark|date=6 March 2017|access-date=5 January 2019}}</ref> ({{coord|37|6| |

* Tristan da Cunha, the main and largest island, area: {{convert|98|km2|sqmi|1}}<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.thoughtco.com/tristan-da-cunha-1435571 |website=ThoughtCo |title=Tristan da Cunha |last=Rosenberg |first=Mark |date=6 March 2017 |access-date=5 January 2019 |archive-date=24 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220524054103/https://www.thoughtco.com/tristan-da-cunha-1435571 |url-status=live }}</ref> ({{coord|37|6|54|S|12|17|6|W|type:isle|name=Tristan da Cunha}}) |

||

* [[Inaccessible Island]], area: {{ |

* [[Inaccessible Island]], area: {{cvt|14|km2|sqmi|1}} |

||

* [[Nightingale Islands]], area: {{ |

* [[Nightingale Islands]], area: {{cvt|3.4|km2|sqmi|1}} |

||

** [[Nightingale Island]], area: {{ |

** [[Nightingale Island]], area: {{cvt|3.2|km2|sqmi|1}} |

||

** [[Middle Island, Tristan da Cunha|Middle Island]], area: {{ |

** [[Middle Island, Tristan da Cunha|Middle Island]], area: {{cvt|0.1|km2|acre|0}} |

||

** [[Stoltenhoff Island]], area: {{ |

** [[Stoltenhoff Island]], area: {{cvt|0.1|km2|acre|0}} |

||

* [[Gough Island]] (''Diego Alvarez''), area: {{ |

* [[Gough Island]] (''Diego Alvarez''), area: {{cvt|91|km2|sqmi|0}}<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.sanap.ac.za/sanap_gough/sanap_gough.html |title=Gough Island |publisher=South African National Antarctic Programme |access-date=25 October 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081230015511/http://www.sanap.ac.za/sanap_gough/sanap_gough.html |archive-date=30 December 2008 }}</ref> |

||

Inaccessible Island and the Nightingale Islands are {{convert|35|km|mi|0}} [[boxing the compass|SW by W and SSW]] away from the main island, respectively, whereas Gough Island is {{convert|350|km|mi|0}} SSE.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Tristan da Cunha Outer Islands|url=https://www.tristandc.com/mapgroup.php|access-date=2020 |

Inaccessible Island and the Nightingale Islands are {{convert|35|km|mi|0}} [[boxing the compass|SW by W and SSW]] away from the main island, respectively, whereas Gough Island is {{convert|350|km|mi|0}} SSE.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Tristan da Cunha Outer Islands |url=https://www.tristandc.com/mapgroup.php |access-date=3 September 2020 |website=www.tristandc.com |archive-date=1 September 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200901222639/https://www.tristandc.com/mapgroup.php |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

[[File:Tristanfromspace.jpg|thumb|Tristan da Cunha on 6 February 2013, as seen from the International Space Station]] |

|||

The main island is generally mountainous. The only flat area is on the north-west coast, which is the location of the only settlement, [[Edinburgh of the Seven Seas]]. The highest point is the summit of a volcano called [[Queen Mary's Peak]] at an elevation of {{convert|2062|m|ft|0}}, high enough to develop snow cover in winter. The other islands of the group are uninhabited, except for a weather station with a staff of six on Gough Island, which has been operated by [[South Africa]] since 1956 and has been at its present location at Transvaal Bay on the southeast coast since 1963.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tristandc.com/gough.php|website=Tristan da Cunha|title=Tristan da Cunha Gough Island|access-date=5 January 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://dxnews.com/zd9a_gough/|website=DX News|title=ZD9A Gough Island|date=23 June 2016|access-date=5 January 2019}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Tristanfromspace.jpg|thumb|Tristan da Cunha on 6 February 2012, as seen from the International Space Station]] |

|||

The main island is generally mountainous. The only flat area is on the north-west coast, which is the location of the only settlement, [[Edinburgh of the Seven Seas]], and the agricultural area of [[Potato Patches]]. The highest point is the summit of a volcano called [[Queen Mary's Peak]] at an elevation of {{convert|2062|m|ft|0}}, high enough to develop snow cover in winter. The other islands of the group are uninhabited, except for a weather station with a staff of six on Gough Island, which has been operated by [[South Africa]] since 1956 and has been at its present location at Transvaal Bay on the southeast coast since 1963.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.tristandc.com/gough.php |website=Tristan da Cunha |title=Tristan da Cunha Gough Island |access-date=5 January 2019 |archive-date=3 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220803135555/https://www.tristandc.com/gough.php |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://dxnews.com/zd9a_gough/ |website=DX News |title=ZD9A Gough Island |date=23 June 2016 |access-date=5 January 2019 |archive-date=14 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220514091825/https://dxnews.com/zd9a_gough/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

[[File:View on Tristan da Cunha.jpg|thumb|center|1000x1000px|View of Tristan da Cunha]] |

|||

===Climate=== |

===Climate=== |

||

The archipelago has a Cfb, wet [[oceanic climate]], under the [[Köppen climate classification|Köppen system]], with mild temperatures and very limited sunshine but consistent moderate-to-heavy rainfall due to the persistent westerly winds.<ref>Kottek |