Hueco Tanks: Difference between revisions

Tom.Reding (talk | contribs) m +{{Authority control}} (1 ID from Wikidata), WP:GenFixes on |

Eah2beah2b (talk | contribs) →External links: added links to a video |

||

| Line 115: | Line 115: | ||

* [http://outdoorlifestyle.com/texas/hueco-tanks-state-park-000011.html Hueco Tanks] Picture of a hueco, description of the video the park makes campers view, and links. |

* [http://outdoorlifestyle.com/texas/hueco-tanks-state-park-000011.html Hueco Tanks] Picture of a hueco, description of the video the park makes campers view, and links. |

||

* {{Gnis|1338224|Hueco Tanks State Historic Site}} |

* {{Gnis|1338224|Hueco Tanks State Historic Site}} |

||

*[https://texasarchive.org/2019_00889 News story on Hueco Tanks] from [[WFAA]] on [[Texas Archive of the Moving Image]] |

|||

{{Protected areas of Texas}} |

{{Protected areas of Texas}} |

||

Revision as of 02:51, 26 June 2021

Hueco Tanks | |

East Mountain at Hueco Tanks | |

| Nearest city | El Paso, Texas |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 31°55′13″N 106°02′19″W / 31.92028°N 106.03861°W |

| Area | 860 acres (350 ha) |

| NRHP reference No. | 71000930[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Prehistoric | 1000-1499 AD |

| Historic Aboriginal | 1500-1824 |

| Added to NRHP | July 14, 1971 |

| Designated NHL | January 13, 2021 |

| Designated TSHS | June 12, 1969 |

Hueco Tanks is an area of low mountains and historic site in El Paso County, Texas, in the United States. It is located in a high-altitude desert basin between the Franklin Mountains to the west and the Hueco Mountains to the east. Hueco is a Spanish word meaning hollows and refers to the many water-holding depressions in the boulders and rock faces throughout the region. Due to the unique concentration of historic artifacts, plants and wildlife, the site is under protection of Texas law; it is a crime to remove, alter, or destroy them.[2]

The historic site is located approximately 32 miles (51 km) northeast of central El Paso, Texas, accessible via El Paso's Montana Avenue (U.S. Route 62/U.S. Route 180), by turning at RM 2775. The park consists of three syenite (a weak form of granite) mountains; it is 860 acres (350 ha) in area[3] and is popular for recreation such as birdwatching and bouldering. It is culturally and spiritually significant to many Native Americans. This significance is partially manifested in the pictographs (rock paintings) that can be found throughout the region, many of which are thousands of years old.[4]

Designation

Hueco Tanks State Park & Historic Site was obtained from the county by special deed on June 12, 1969, and by purchase of 121 additional acres on August 10, 1970. This site was opened to the public in May 1970. This 860.3-acre park is named for the large natural rock basins or "huecos" that have furnished a supply of trapped rainwater to dwellers and travelers in this arid region of west Texas for millennia.[5]

History

The park has gone through considerable changes during private and public ownership.The inscribed names of Texas Rangers and US Cavalrymen, as well as Native American artifacts and paintings, attest to its historic nature.[6]

This site had originally attracted people due to its critical resource needed to survive life in the desert-water. The huge rocks and boulders have cracks and are pocketed with holes-huecos that trap and hold rainwater for months at a time. Passing people found this out and had made it known for future travelers by encrypting the walls with pictures and symbols on the rocks.[7]

Early inhabitants

Human habitation of the area dates back 10,000 years with the arrival of the Desert Archaic Culture.[9] These people would have eaten mesquite beans, banana yucca and cactus fruits in Hueco Tanks.[10] The region was inhabited by various peoples, from the Paleo-Indians who used Folsom points to hunt the Megafauna of North America, to the people of the 'Jornada Mogollon' (pronounced mo-goi-YONE). This site was once a Jornada Mogollon village, according to an archaeological dig of the ground between North Mountain and West Mountain. By about 700 years ago, the population of the village could no longer be sustained by the small agricultural area surrounding Hueco Tanks. At this point, a population shift occurred and settlements were formed on the nearby playas to the south, west, and northwest. There, they flourished until about 1450 A.D. when the area suffered from a series of severe droughts.[11] Although it took time, by about 1600 A.D. the region was inhabited by the Apache people, who moved in from Canada (see the Athabascans).

Agriculture was introduced in the area sometime around 1000 A.D. and along with it, the development of the Jornada Mogollon Culture.[9] The Jornada people built a village in the area and grew corn.[12]

Later the area was occupied by Mescalero and Lipan Apaches and Jumano people.[9] Also using the area were Comanche, Kiowa and Tiguas.[9] Spanish and Mexican travelers were rare visitors to the area.[9] The Kiowa called the area the Tso-doi-gyata-de-dee, meaning "rock cave where they were surrounded."[13] In 1837, the Kiowa signed a treaty with the United States, however, shortly after Mexican soldiers forced them into a six-day siege in Hueco Tanks, during which most of them died.[13] The earliest known modern graffiti dates back to the 1840s.[12]

The area was visited by United States Boundary Commissioner, John R. Bartlett, in 1852 who recorded some of the pictographs.[9] Between 1858 and 1859, the Butterfield Overland Mail kept a stagecoach station in the area, but left when a better location was found to the south.[9] An El Paso businessman, Juan Armadariz, purchased much of the Hueco Tanks land to use for ranching in 1895.[14] Silverio Escontrías bought the land from Armendariz in 1898 and the family used it as a ranch and tourist attraction until 1956.[9] The early El Paso Archaeological Society (EPAS) began to campaign for the land to be turned into a park and in 1935, the National Park Service offered to buy the land from the Escontrías family, but they refused.[14] Fort Bliss leased land from the Escontrías family for training purposes in the 1940s and 50s.[14] The ranch went on the real estate market in 1956 and during this time, members of archaeological and historical societies raised awareness of the area's significance.[14] El Paso County took over the land in the mid-1960s.[9]

In 1968, it was discussed whether or not the park should be turned over to the Tiguas.[15] In 1969, the El Paso County commissioners decided to deed the park to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission.[16] It was made a Texas State Park in 1970.[3] The park's information center was made from the old Escontrías ranch house.[17] It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971.[9] Archaeological excavations conducted by George Kegley took place in the area between 1972 and 1973.[9] The park was named the Hueco Tanks State Historic Site in 1998.[9]

Pictographs

The first paintings made at Hueco Tanks were done by members of the Desert Archaic Culture, and depicted abstract designs.[10] These were created between 6000 and 3000 B.C.[10] Between 3000 BC and 450 A.D., pictures of animals and humans were drawn on the rocks.[18]

Most of the pictographs at Hueco Tanks are of Jornada Mogollon origin.[19] The drawings may have been used in praying for rain.[19] The Jornada's religion was influenced by Mesoamerican religions.[20] Many of the Hueco Tanks drawings depicted Tlaloc, a rain god and Quetzalcoatl.[20]

Modern graffiti by Anglo people started appearing when someone painted "1849" over some of the original pictographs.[21]

The first scientific overview of the rock paintings at Hueco Tanks happened in the summer of 1939 with Forrest and Lula Kirkland recording the art.[22] Most of the colors used in the paintings came from minerals in the area.[23] The paintings themselves became bound to the rock through the aging process.[22]

In 1972, the El Paso Archaeological Society (EPAS) and the Anthropology Club of the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) systematically documented the drawings, their current conditions and sometimes relocated and inspected the rock art.[24] The project discovered 300 previously unrecorded pictographs.[24] The findings of their work was published in A Rock Art Inventory at Hueco Tanks State Park (1974).[24] In 1988, park ranger Dave Parker and archeologist Ron Ralph plotted the location of all known pictographs.[24] A digital database of the art and its GPS coordinates was started in 1999 with Robert Mark and Evelyn Billo.[24]

Geology

The syenite pluton was formed 34-38 million years ago, as part of a larger range, the Hueco Mountains, which range in age to over 320 million years ago, when this area was covered by an inland sea. The pluton was eventually exposed through weathering to form the rock formations visible today, which jut from the desert floor. The tanks were once capable of containing a year's supply of water.[9] In addition to the tanks, there are several permanent springs and seasonal springs in the area.[25] The area receives less than 14 inches (360 mm) of rainfall a year.[26]

The syenite rock formation is covered with 'desert patina' (visible in the image below), the result of thousands of years of weathering of the rock surface by sun, sand, and water; the site is culturally and spiritually significant to many Native Americans, such as the Mescalero Apache, the Kiowa,[27] the Hopi, and the Pueblo people. This significance is partially manifested in the pictographs (rock paintings) that can be found throughout the region, some of which are thousands of years old. Hueco Tanks contains the single largest concentration of mask paintings by Native Americans in North America, of which hundreds exist at this site.[28]

Wildlife

Freshwater shrimp and spadefoot toads survive at the site; for this and other reasons, visitors are cautioned against touching the pools of water at Hueco Tanks to avoid destroying the eggs of these animals.[29][30] Other amphibians seen in the park include barred tiger salamanders.[26] Around 30 different species of reptiles live in the area.[26] In 2002, 222 different species of bird were documented at the site during the year.[25] Migratory birds such as waterfowl and songbirds pass through during migration seasons.[26] Several birds such as the prairie falcon, burrowing owl, white throated swift, black-chinned hummingbird, ash throated flycatcher, Crissal thrasher, blue grosbeak, Scott's oriole and lesser goldfinch all likely breed in the area.[26] The park is home today to mule deer, black bears, bobcats, gray fox, coyotes, badgers, ringtails, skunks, raccoons, mountain lions, black-tailed jackrabbits, desert cottontail, eastern cottontail, six species of bats and twenty species of rodents.[26][31]

Plants

Around the syenite outcrops, the park is surrounded by Chihuahuan Desert scrub with creosote bush as the dominant species.[25] The site contains enough water to support live oaks and junipers, species which survive from the last ice age. Other trees found in the area include netleaf hackberry, Texas mulberry, Mexican buckeye, Gregg acacia and Arizona oak.[25][32] Hueco Tanks has the only population in the United States of the plant Colubrina stricta.[26]

Rock climbing

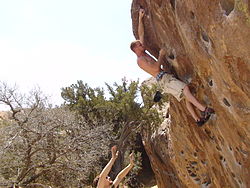

Hueco Tanks is widely regarded as one of the best areas in the world for bouldering[33] that is, rock climbing low enough to attempt without ropes for protection. It is unique for its rock type, the concentration and quality of the climbing. In any given climbing season, which generally lasts from October through March, it is common for climbers from across Europe, Asia, and Australia to visit the park. In February an outdoor bouldering competition known as the Hueco Rock Rodeo is held. The event is a world-class outdoor competition that attracts many professional climbers every year.[34] Since implementation of the Public Use Plan in June 2000,[35][36] following a brief closure of the entire park due to the park service's inability to manage the growing crowds of international climbers, more than two-thirds of the park is restricted to tours by volunteer or commercial guides. Only North Mountain is accessible without guides, and then only for about 70 people at any given time, except on the south side at ground level, which is closed to the public.[37] The park offers camping and showers for $12 per night (as of April 2020),[38] or, as is most popular for climbers, the nearby Hueco Rock Ranch offers camping where climbers can relax and socialize. This is also where commercial guides can be found, and where many volunteer guides stay during the climbing season.[citation needed]

See also

Notes

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Sutherland 1996 p.25

- ^ a b Rentería, Ramón (24 May 2011). "Ancient desert oasis - Hueco Tanks a monument to native cultures". Las Cruces Sun-News.

- ^ Mulvihill, K. "On Rock Walls, Painted Prayers to Rain Gods", The New York Times. September 19, 2008. Retrieved 9/19/08.

- ^ http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/state-parks/hueco-tanks/park_history

- ^ Video of Hueco Tanks State Historic Site and Climbing opportunities Archived 2007-11-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Texas Beyond History". Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ^ Sutherland 1996 p.18 and also title page.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Miles, Robert W.; Ralph, Ronald W. (15 June 2010). "Hueco Tanks State Historic Site". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ a b c Sutherland 1996, p. 8.

- ^ "Hueco Tanks." Texas Beyond History. Jan. 2008. Web. 22 Mar. 2011. <http://www.texasbeyondhistory.net/hueco/story.html>.

- ^ a b "Hueco Tanks". Texas Beyond History. January 2008. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- ^ a b Metz 1999, p. 275.

- ^ a b c d "Weaving the Story: The People of Hueco Tanks". Texas Beyond History. January 2008. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- ^ Metz 1993, p. 262.

- ^ Metz 1993, p. 263.

- ^ Metz 1999, p. 276.

- ^ Sutherland 1996, p. 9.

- ^ a b Knight, Bill (2 June 2017). "Hueco Tanks closes areas to protect pictographs". El Paso Times. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- ^ a b Sutherland 1996, p. 13.

- ^ Sutherland 1996, p. 6.

- ^ a b Sutherland 1996, p. 4.

- ^ Sutherland 1996, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e "Explorations and Archeological Investigations". Texas Beyond History. January 2008. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- ^ a b c d Zimmer 2002, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Natural Setting: A Rocky Oasis in the Desert". Texas Beyond History. January 2008. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- ^ Konate, a Kiowa was wounded at Hueco Tanks during an 1839 ambush by Mexican militia. Konate survived to return to his home in Oklahoma, where the story was preserved.

- ^ Forrest Kirkland & W.W. Newcomb (1967), Rock Art of the Texas Indians, Austin: University of Texas Press. Kirkland distinguishes two different styles of mask: 1) the outline mask 2) the solid mask.

- ^ Interpretive Center, Orientation Video, Hueco Tanks State Historic Site, 2009-12-26

- ^ Spadefoot toads have re-spawned in Hueco Tanks, September 2010, due to the heavy monsoon rains this year. —Ed Woton, Interpretive Guide, Hueco Tanks State Historic Site, Oct 17, 2010.

- ^ "Hueco Tanks State Park & Historic Site Nature — Texas Parks & Wildlife Department". tpwd.texas.gov.

- ^ "Hueco Tanks State Park & Historic Site Nature — Texas Parks & Wildlife Department". tpwd.texas.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-27.

- ^ "Rock Climbing Routes in Hueco Tanks State Historic Site, West Texas". RockClimbing.com. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- ^ "Hueco Rock Rodeo - Destination El Paso | El Paso, Texas". visitelpaso.com. Retrieved 2020-04-27.

- ^ "Hueco Tanks Public Use Plan Under Review". Rock and Ice. Retrieved 2020-04-27.

- ^ "Public Use Plan 2000" (PDF).

- ^ "Hueco Tanks State Park & Historic Site Park Activities — Texas Parks & Wildlife Department". tpwd.texas.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-27.

- ^ "Hueco Tanks State Park & Historic Site Campsites — Texas Parks & Wildlife Department". tpwd.texas.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-27.

References

- Gale Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes, Volume II, p203-205. (Mogollon)

- Metz, Leon C. (1993). El Paso Chronicles: A Record of Historical Events in El Paso, Texas. El Paso, Texas: Mangan Books. ISBN 9780930208325.

- Metz, Leon (1999). El Paso: Guided Through Time. El Paso, Texas: Mangan Books. ISBN 0930208374.

- Sutherland, Kay, Ph.D. (1996). Rock Paintings at Hueco Tanks State Historical Park (PDF). Austin, Texas: Texas Parks & Wildlife Department. PWD-BK-P4503-095D-1291.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Texas Parks & Wildlife Magazine, September 2004, The Rocks that Speak, Carol Flake Chapman, p41-45.

- Turquoise Ridge and Late Prehistoric Residential Mobility in the Desert Mogollon Region, Whalen, Michael E., Salt Lake City University of Utah Press, 1994.

- Zimmer, Barry R. (2002). Birds of Hueco Tanks State Historic Site: A Field Checklist (PDF). Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

External links

- Firecracker Pueblo discusses the extent of the Jornada Mogollon.

- "Hueco Tanks State Historic Site Park information". Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- South and West Texas: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary

- Hueco Rock Ranch for climbers.

- Ancient Rock Art is Reborn at Hueco Tanks State Park on YouTube (2012 video)

- Hueco Tanks State Historic Site

- Hueco Tanks Picture of a hueco, description of the video the park makes campers view, and links.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Hueco Tanks State Historic Site

- News story on Hueco Tanks from WFAA on Texas Archive of the Moving Image