Italian modern and contemporary architecture: Difference between revisions

LadyFarquaad (talk | contribs) Copy Editing and addition of wikilinks |

Wingedserif (talk | contribs) m multiple issues template |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Multiple issues| |

|||

{{refimprove|date=March 2010}} |

{{refimprove|date=March 2010}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Rough translation|Italian}} |

{{Rough translation|Italian}} |

||

}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

'''Italian modern and contemporary architecture''' refers to architecture in Italy during the 20th and 21st centuries. |

'''Italian modern and contemporary architecture''' refers to architecture in Italy during the 20th and 21st centuries. |

||

Revision as of 11:14, 28 April 2021

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

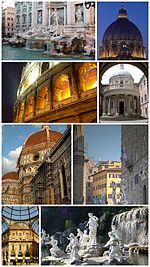

| Architecture of Italy |

|---|

|

| Periods and styles |

| Palaces and gardens |

| Notable works |

| Notable architects |

|

|

| By region |

| Other topics |

Italian modern and contemporary architecture refers to architecture in Italy during the 20th and 21st centuries.

Styles

Beginning of 20th century

The Art Nouveau style was introduced in Italy by figures such as Giuseppe Sommaruga and Ernesto Basile (the former designed the Palazzo Castiglioni and the latter expanded the Palazzo Montecitorio in Rome). The principles of this new style were published in 1914 in the Manifesto dell'Architettura Futurista (Manifesto of Futurist Architecture) by Antonio Sant'Elia. The Italian group of architects Gruppo 7 (1926) embraced Rationalism and Modernism principles. After the dissolution of the group, its distinguished figures Giuseppe Terragni (Casa del Fascio, Como), Adalberto Libera (Villa Malaparte in Capri) and Giovanni Michelucci (Santa Maria Novella Station in Florence, in collaboration) emerged. During the Fascist period, the so-called "Novecento movement" flourished, with figures such as Gio Ponti, Peter Aschieri, Giovanni Muzio. This movement was based on the rediscovery of imperial Rome. Marcello Piacentini, who was responsible for the urban transformations of several cities in Italy, and remembered for the disputed Via della Conciliazione in Rome, devised a form of "simplified Neoclassicism".

Fascism

The period of time following the end of World War II was marked by several architectural talents, such as Luigi Moretti, Carlo Scarpa, Franco Albini, Giò Ponti, and Tomaso Buzzi, amongst others, with various styles. Pier Luigi Nervi, for example, designed bold and concrete structures, and acquired an international reputation: his work also influenced Riccardo Morandi and Sergio Musmeci. In a series of interesting debates, brought forward by critics such as Bruno Zevi, Rationalism prevailed, of which the Rome Termini Station can be said to be a paradigmatic work. The neorealism of Giovanni Michelucci (designer of numerous churches in Tuscany), Charles Aymonino, Mario Ridolfi and others (INA-Casa neighbourhoods) was followed by the Neoliberty style (seen in earlier works of Vittorio Gregotti) and Brutalist architecture (Torre Velasca in Milan group BBPR, a residential building via Piagentina in Florence, Leonardo Savioli and works by Giancarlo De Carlo).

Modernism

Carlo Scarpa executed many modernist projects throughout the Veneto region and particularly in Venice. Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright did not build anything in Italy, as opposed to Alvar Aalto (Santa Maria Assunta (Riola) Church of the Assumption in Riola, Vergato), Kenzo Tange (towers of Bologna Fair, the floor of Naples central business district (CDN)) and Oscar Niemeyer (home of Mondadori in Segrate). The Postmodern style in architecture, anticipated by Paolo Portoghesi around 1960, can be seen in the "Teatro del Mondo" (Theatre of the World) built by Aldo Rossi for the Venice Biennale of 1980.

Rationalism also influenced Modernism in Italian architecture. Particularly, this design ethos reconciled the modern aesthetic ideals with religion, since this particular motif was not inimical to the priorities of the modern Italian architects. It gave rise to the so-called "secular-spirituality" – an element in Italian modernism – that focuses on the concept of enlightened rationalism.[1] Another aspect of Italian modernism involves the diversity of interpretations with respect to how modernity is experienced. For example, the northern regions interpreted unornamented design as a rejection of culture and style.[1]

Post-modernism

Among the principal architects working in Italy between the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st centuries were Renzo Piano (Stadio San Nicola in Bari, restructuring the Old Port of Genoa, Auditorium Parco della Musica in Rome, Padre Pio in San Giovanni Rotondo), Massimiliano Fuksas (skyscraper in the Piedmont region, Convention Center in the EUR), Gae Aulenti (the Railway Museum (Naples metro) of Naples underground), the Swiss Mario Botta (Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Trento and Rovereto, renovation of the Teatro alla Scala in Milan), Zaha Hadid (National Museum of the 21st Century Arts in Rome, skyscraper "Lo Storto" in Milan), Richard Meier (Church of God Merciful Father and the casket of the Ara Pacis, in Rome), Norman Foster (Campus Luigi Einaudi in Turin, and the Belfiore station in Florence), Daniel Libeskind (skyscraper "Il Curvo" in Milan) and Arata Isozaki (Palasport Olimpico in Turin, with Pier Paolo Maggiora and Marco Brizio, "Il Dritto" skyscraper in Milan).

One of the prominent features of the postmodernist architecture in Italy can be identified as a reaction to modernism and to the fascist regime, which appropriated classical architectural forms and modernity. After these periods, there was an identifiable attempt to search for new design directions. Emergent works began to demonstrate atmospheres of nostalgia and memory.[2] A group of young architects such as those who formed the group "La Tendenza" (e.g. Carlo Aymonino, Giorgio Grassi and Aldo Rossi) began to explore the question of memory and the glory of the Italian past, integrating their motifs in their works as physical presence and poetic content.[2] They endeavored to expose the weaknesses of modernism, such as their critique of urbanism.

See also

References

- ^ a b Lejeune, Jean-Francois; Sabatino, Michelangelo (2009). Modern Architecture and the Mediterranean: Vernacular Dialogues and Contested Identities. London: Routledge. p. 48. ISBN 0415776333.

- ^ a b Jones, Peter; Canniffe, Eamonn (2007). Modern Architecture Through Case Studies 1945 to 1990. Boston: Elsevier. p. 189. ISBN 9780750663748.