Geography of Laos: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 0 as dead.) #IABot (v2.0.8 |

||

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

The [[United Nations Development Programme]] warns: "Protecting the environment and sustainable use of natural resources in Lao PDR is vital for poverty reduction and economic growth."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.undplao.org/whatwedo/energy_env.php|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080311201841/http://www.undplao.org/whatwedo/energy_env.php|archive-date=11 March 2008|title=Energy & Environment for Sustainable Development |publisher=United Nations Development Programme|access-date=20 April 2011}}</ref> |

The [[United Nations Development Programme]] warns: "Protecting the environment and sustainable use of natural resources in Lao PDR is vital for poverty reduction and economic growth."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.undplao.org/whatwedo/energy_env.php|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080311201841/http://www.undplao.org/whatwedo/energy_env.php|archive-date=11 March 2008|title=Energy & Environment for Sustainable Development |publisher=United Nations Development Programme|access-date=20 April 2011}}</ref> |

||

In April 2011, ''[[The Independent]]'' newspaper reported that Laos had started work on the controversial [[Xayaburi Dam]] on the [[Mekong River]] without getting formal approval. Environmentalists say the dam will adversely affect 60 million people and Cambodia and Vietnam—concerned about the flow of water further downstream—are officially opposed to the project. The [[Mekong River Commission]], a regional intergovernmental body designed to promote the "sustainable management" of the river, famed for its [[Mekong Giant Catfish|giant catfish]], carried out a study that warned if Xayaburi and subsequent schemes went ahead, it would "fundamentally undermine the abundance, productivity and diversity of the Mekong fish resources".<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/green-living/mekong-ecology-in-the-balance-as-laos-quietly-begins-work-on-dam-2270082.html|title=Mekong ecology in the balance as Laos quietly begins work on dam|newspaper=The Independent|date= |

In April 2011, ''[[The Independent]]'' newspaper reported that Laos had started work on the controversial [[Xayaburi Dam]] on the [[Mekong River]] without getting formal approval. Environmentalists say the dam will adversely affect 60 million people and Cambodia and Vietnam—concerned about the flow of water further downstream—are officially opposed to the project. The [[Mekong River Commission]], a regional intergovernmental body designed to promote the "sustainable management" of the river, famed for its [[Mekong Giant Catfish|giant catfish]], carried out a study that warned if Xayaburi and subsequent schemes went ahead, it would "fundamentally undermine the abundance, productivity and diversity of the Mekong fish resources".<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/green-living/mekong-ecology-in-the-balance-as-laos-quietly-begins-work-on-dam-2270082.html|title=Mekong ecology in the balance as Laos quietly begins work on dam|newspaper=The Independent|date=20 April 2011|access-date=20 April 2011|location=London|first=Andrew|last=Buncombe|archive-date=23 April 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110423014601/http://www.independent.co.uk/environment/green-living/mekong-ecology-in-the-balance-as-laos-quietly-begins-work-on-dam-2270082.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> Neighbouring Vietnam warned that the dam would harm the [[Mekong Delta]], which is the home to nearly 20 million people and supplies around 50 percent of Vietnam's rice output and over 70 percent of both its [[seafood]] and fruit output.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://khampoua.wordpress.com/tag/laos-hydroelectric-project/|title=Vietnam worries about impacts from Laos hydroelectric project|publisher=Voices for the Laotian Who do not have Voices |access-date=20 April 2011}}</ref> By building dams Laos is willing to become the battery of Asia by selling electricity to its neighboring countries.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/09/laos-building-dams-negative-impacts-180911043821027.html|title=Laos to keep building dams despite negative impacts|website=www.aljazeera.com|access-date=11 September 2018}}</ref> |

||

[[Milton Osborne]], Visiting Fellow at the [[Lowy Institute for International Policy]] who has written widely on the Mekong, warns: "The future scenario is of the Mekong ceasing to be a bounteous source of fish and guarantor of agricultural richness, with the great river below China becoming little more than a series of unproductive lakes."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/world/mekong-dam-plans-threatening-the-natural-order/story-e6frg6ux-1226083709322|title=Mekong dam plans threatening the natural order|newspaper=The Australian|author=Osborne, Milton |date=29 June 2011}}</ref> |

[[Milton Osborne]], Visiting Fellow at the [[Lowy Institute for International Policy]] who has written widely on the Mekong, warns: "The future scenario is of the Mekong ceasing to be a bounteous source of fish and guarantor of agricultural richness, with the great river below China becoming little more than a series of unproductive lakes."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/world/mekong-dam-plans-threatening-the-natural-order/story-e6frg6ux-1226083709322|title=Mekong dam plans threatening the natural order|newspaper=The Australian|author=Osborne, Milton |date=29 June 2011}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 07:47, 6 August 2021

18°00′N 105°00′E / 18.000°N 105.000°E

Laos is an independent republic, and the only landlocked nation in Southeast Asia, northeast of Thailand, west of Vietnam. It covers 236,800 square kilometers in the center of the Southeast Asian peninsula and it is surrounded by Myanmar (Burma), Cambodia, the People's Republic of China, Thailand, and Vietnam. About seventy percent of its geographic area is made up of mountain ranges, highlands, plateaux, and rivers cut through.

Its location has often made it a buffer state between more powerful neighboring states, as well as a crossroads for trade and communication. Migration and international conflict have contributed to the present ethnic composition of the country and to the geographic distribution of its ethnic groups.

Topography

Most of the western border of Laos is demarcated by the Mekong river, which is an important artery for transportation. The Dong Falls at the southern end of the country prevent access to the sea, but cargo boats travel along the entire length of the Mekong in Laos during most of the year. Smaller power boats and pirogues provide an important means of transportation on many of the tributaries of the Mekong.

The Mekong has thus not been an obstacle but a facilitator for communication, and the similarities between Laos and northeast Thai society—same people, almost same language—reflect the close contact that has existed across the river for centuries. Also, many Laotians living in the Mekong Valley have relatives and friends in Thailand.

Prior to the twentieth century, Laotian kingdoms and principalities encompassed areas on both sides of the Mekong, and Thai control in the late nineteenth century extended to the left bank. Although the Mekong was established as a border by French colonial forces, travel from one side to the other has been significantly limited only since the establishment of the Lao People's Democratic Republic (LPDR, or Laos) in 1975.

The eastern border with Vietnam extends for 2,130 kilometres, mostly along the crest of the Annamite Chain, and serves as a physical barrier between the Chinese-influenced culture of Vietnam and the Indianized states of Laos and Thailand. These mountains are sparsely populated by tribal minorities who traditionally have not acknowledged the border with Vietnam any more than lowland Lao have been constrained by the 1,754-kilometre Mekong River border with Thailand. Thus, ethnic minority populations are found on both the Laotian and Vietnamese sides of the frontier. Because of their relative isolation, contact between these groups and lowland Lao has been mostly confined to trading.

Laos shares its short—only 541 kilometres—southern border with Cambodia, and ancient Khmer ruins at Wat Pho and other southern locations attest to the long history of contact between the Lao and the Khmer. In the north, the country is bounded by a mountainous 423-kilometre border with China and shares the 235-kilometre-long Mekong River border with Myanmar.

The topography of Laos is largely mountainous, with the Annamite Range in the northeast and east and the Luang Prabang Range in the northwest, among other ranges typically characterized by steep terrain. Elevations are typically above 500 metres with narrow river valleys and low agricultural potential. This mountainous landscape extends across most of the north of the country, except for the plain of Vientiane and the Plain of Jars in the Xiangkhoang Plateau.

The southern "panhandle" of the country contains large level areas in Savannakhét and Champasak provinces that are well suited for extensive paddy rice cultivation and livestock raising. Much of Khammouan Province and the eastern part of all the southern provinces are mountainous. Together, the alluvial plains and terraces of the Mekong and its tributaries cover only about 20% of the land area.

Only about 4% of the total land area is classified as arable. The forested land area has declined significantly since the 1970s as a result of commercial logging and expanded swidden, or slash-and-burn, farming.

List of mountains in Laos

- Phou Bia, 2,819 m

- Phu Xai Lai Leng, 2,720 m

- Rao Co, 2,286 m

- Phou Louey, 2,257 m, located at Lat/Lon {20.27057, 103.19746}

- Phu Soi Dao, 2,120 m

- Pu Ke, 2,079 m

- Shiceng Dashan, 1,830 m

- Dong Ap Bia, 937 m

Climate

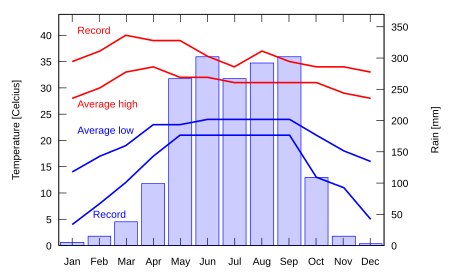

Laos has a tropical climate, with a pronounced rainy season from May through October, a cool dry season from November through February, and a hot dry season in March and April. Generally, monsoons occur at the same time across the country, although that time may vary significantly from one year to the next.

Rainfall varies regionally, with the highest amounts—3,700 millimeters (150 inches) annually—recorded on the Bolovens Plateau in Champasak Province. City rainfall stations have recorded that Savannakhét averages 1,440 millimeters (57 inches) of rain annually; Vientiane receives about 1,700 millimeters (67 inches), and Louangphrabang (Luang Prabang) receives about 1,360 millimeters (54 inches).

Rainfall is not always adequate for rice cultivation and the relatively high average precipitation conceals years where rainfall may be only half or less of the norm, causing significant declines in rice yields. Such droughts often are regional, leaving production in other parts of the country unaffected.

The average temperatures in January, coolest month, are, Luang Prabang 20.5 °C (minimum 0.8 °C), Vientiane 20.3 °C (minimum 3.9 °C), and Pakse 23.9 °C (minimum 8.2 °C); the average temperatures for April, usually the hottest month, are, Luang Prabang 28.1 °C (maximum 44.8 °C), Vientiane 39.4 °C). Temperature does vary according to the altitude, there is an average drop of 1.7 °C for every 1000 feet (or 300 meters). Temperatures in the upland plateux and in the mountains are considered lower than on the plains around Vientiane.

Laos is highly vulnerable to the effects of global climate change; nearly all provinces in Laos are at high risks from climate change.[1]

Agriculture

Agriculture in Laos is the most important sector of the economy. Five million out of 23,680,000 hectares of Laos's total land area is suitable for cultivation, and seventeen percent of the land area, between 850,000 and 900,000 hectares, is cultivated. Rice is the main crop grown during the rainy season both upland and wet. There is also a significant amount of fishing.

Agricultural cultivation is possible during with varying weather on a small portion of land area apart from the Vientiane plain and the lowlands along the Mekong Valley. These cultivated areas are situated in the valley cuts by the rivers or the plateau regions of Xieng Khouang in the North and in the Bolovens in the south. Typically there are only two ways to cultivate: either the wet-field paddy system practiced among the Lao Loum or lowland in Lao, or the swidden cultivation system practiced in the hills.

Population

Laos has a smaller population than most countries in South East Asia. The first comprehensive national population census of Laos was taken in 1985; it recorded a population of about 3.57 million. In 1987, the population was officially stated as 3,830,000 and the capital city, Vientiane, had a population of 120,000. The annual growth was estimated at between 2.6 and 3.0 percent. The national birth rate is estimated at about forty-five per 1,000, while the death rate estimates at around sixteen per 1,000. The fertility rates are higher between ages twenty and forty which highlights the average woman giving birth to an average of 6.8 children.

The overall population density was only eighteen persons per square kilometer, and in many districts the density was fewer than ten persons per square kilometer. Population density per cultivated hectare was considerably high ranging from 3.3 to 7.8 persons per hectare. The population is ethnically diverse, but a complete classification of all ethnic groups has never been undertaken. Discrepancies in the number of groups resulted from inconsistent definitions of what constitutes an ethnic group as opposed to a subgroup, as well as incomplete knowledge about the groups themselves.

Transportation routes

Because of its mountainous topography and lack of development, Laos has few reliable transportation routes. This inaccessibility has historically limited the ability of any government to maintain a presence in areas distant from the national or provincial capitals and has limited interchange and communication among villages and ethnic groups.

The Mekong and Nam Ou are the only natural channels suitable for large-draft boat transportation, and from December through May low water limits the size of the draft that may be used over many routes. Laotians in lowland villages located on the banks of smaller rivers have traditionally traveled in pirogues for fishing, trading, and visiting up and down the river for limited distances.

Otherwise, travel is by ox-cart over level terrain or by foot. The steep mountains and lack of roads have caused upland ethnic groups to rely entirely on pack baskets and horse packing for transportation.

The road system is not extensive. A rudimentary network begun under French colonial rule and continued from the 1950s has provided an important means of increased inter-village communication, movement of market goods, and a focus for new settlements. In mid-1994, travel in most areas was difficult and expensive, and most Laotians traveled only limited distances, if at all. As a result of ongoing improvements in the road system started during the early 1990s, it is expected that in the future villagers will more easily be able to seek medical care, send children to schools at district centers, and work outside the village.

In October 2015 the first highway through the country was completed connecting southern China to Thailand.[1]

Inland waterways, including the Mekong River, is the second most important source of transport network. About 4,600 kilometers of navigable waterways are located within the Mekong, the Ou, and nine other rivers. The Mekong River is only navigable for about seventy percent of its length due to rapids and low water levels in the dry season.

Residents in the lower lands and villages of smaller river banks have traditionally traveled in pirogues for fishing, trading, or visiting up and down the river for limited distances. The public and private trade associations handle river traffic. There are a series of warehouses and ports in Savannakhet, Xeno, and Vientiane. The river transportation has improved since government policy expanded trade with Vietnam and other rural regions.

Natural resources

Expanding commercial exploitation of forests, plans for additional hydroelectric facilities, foreign demands for wild animals and nonwood forest products for food and traditional medicines, and a growing population have brought new and increasing attention to the forests. Traditionally, forests have been important sources of wild foods, herbal medicines, and timber for house construction.

Soils are found commonly throughout the floodplains. Typically, soils are formed from alluvium deposited by the rivers as either sandy clay in light colors or sand clay with gray or yellow colors. Upland soils derive from granitic, schistose, or sandstone parent rocks more acidic and less fertile. Southern Laos has areas of laterite soils, and basaltic soils in the Bolovens Plateau.

Ecology

Flora

Northern Laos has tropical rainforests with broader-leaved evergreens and monsoon forests of mixed evergreen and in the south is filled with deciduous trees. In the monsoon forest, the ground is covered with tall, coarse grass. The trees mostly only reach their secondary growth. Typically, bamboo, scrub, and wild banana are abundant. Laos is also home to hundreds of species of orchids and palms.

Fauna

Forests and fields serve as support for wildlife. Wildlife in Laos includes nearly 200 species of mammals, about the same number for reptiles and amphibians, and about 700 varieties of birds. Common mammals are gaurs (wild oxen), deer, bears, and monkeys. Endangered animals include elephants, rhinoceroses, tigers, several types of wild oxen, monkeys, and gibbons. Snakes, skinks, frogs, and geckoes are abundant. Warblers, babblers, woodpeckers, thrushes, and large raptors inhabit the canopy and floor of the forest. Numerous species of birds live in the lowlands. Lastly, several of Laos's bird species are threatened, including most hornillo, ibises, and storks.

Environmental problems and illegal logging

Laos is increasingly suffering from environmental problems, with deforestation a particularly significant issue,[2] as expanding commercial exploitation of the forests, plans for additional hydroelectric facilities, foreign demand for wild animals and nonwood forest products for food and traditional medicines, and a growing population all create increasing pressure.

The United Nations Development Programme warns: "Protecting the environment and sustainable use of natural resources in Lao PDR is vital for poverty reduction and economic growth."[3]

In April 2011, The Independent newspaper reported that Laos had started work on the controversial Xayaburi Dam on the Mekong River without getting formal approval. Environmentalists say the dam will adversely affect 60 million people and Cambodia and Vietnam—concerned about the flow of water further downstream—are officially opposed to the project. The Mekong River Commission, a regional intergovernmental body designed to promote the "sustainable management" of the river, famed for its giant catfish, carried out a study that warned if Xayaburi and subsequent schemes went ahead, it would "fundamentally undermine the abundance, productivity and diversity of the Mekong fish resources".[4] Neighbouring Vietnam warned that the dam would harm the Mekong Delta, which is the home to nearly 20 million people and supplies around 50 percent of Vietnam's rice output and over 70 percent of both its seafood and fruit output.[5] By building dams Laos is willing to become the battery of Asia by selling electricity to its neighboring countries.[6]

Milton Osborne, Visiting Fellow at the Lowy Institute for International Policy who has written widely on the Mekong, warns: "The future scenario is of the Mekong ceasing to be a bounteous source of fish and guarantor of agricultural richness, with the great river below China becoming little more than a series of unproductive lakes."[7]

Illegal logging is also a major problem. Environmental groups estimate that 500,000 cubic metres (18,000,000 cu ft) of logs are being cut by Vietnam People's Army (VPA) forces, and companies it owns, in co-operation with the Lao People's Army and then transported from Laos to Vietnam every year, with most of the furniture eventually exported to western countries by the VPA military-owned companies.[8][9][10][11]

A 1992 government survey indicated that forests occupied about 48 percent of Laos's land area. Forest coverage decreased to 41 percent in a 2002 survey. Lao authorities have said that, in reality, forest coverage might be no more than 35 percent because of development projects such as dams, on top of the losses to illegal logging.[12]

Most of the deforestation during the 1980s stemmed from the northern region in which the poor destroyed about 300,000 hectares annually.[13] A study conducted in Savannakhet Province revealed a pattern in which the households extracting resources from the forest tended to be the rural poor.[14] It cross referenced the data collected from two groups, the poor and the wealthy to identify possible correlations between welfare and the dependency on the extraction of natural resources to support one's livelihood. Compared to the wealthy group, the poor had higher levels of exposure to environmental, health, and economic shocks in addition to having little capital such as education and financial assets.[14] While the poor depended more on nonwood commodities from the forest to increase food security, the wealthier group would harvest timber and wood for environmental income.[14] A study found a correlation between the loss of forest coverage with socio-economic development and physical factors, such as the elevation and slope of the land or its distance to main roads.[15] The closer a forest was situated to a main road, the increased chances of deforestation; the same applied to the proximity of villages to nearby forests.[15] Furthermore, high elevation areas in the mountains tended to faced higher deforestation rates compared to the flat lands or lower areas.[15] While there is a higher amount of settlements and villages in the lower flat lands, most of the human activities is concentrated in the higher areas thus explaining the different rates.[15] A plethora of environmental issues contributing to the deforestation include problems with the urban environment, mismanaged mineral exploitation, and careless development planning for industrial and transportation sectors.[16]

Among the many ongoing issues threatening Lao's ecosystem with deforestation, there is a growing concern about Invasive Alien Species (IAS) contributing to the environmental degradation and loss of biodiversity.[16] Bringing in alien species to promote economic development has brought notable success such as coffee, which is now one of Lao's main exports.[16] However, as non native plants or species proliferate, new diseases and pests also become an issue which upsets the natural balance of the ecosystem.[16] This prompts farmers to use extensive commercial herbicides to protect their crops from species such as the Mimosa Invisa and Mimosa Pigra weeds, further damaging the land in the long run.[16] Ever since the Golden Apple Snail (GAS) was introduced to Laos from Vietnam in 1994 as a new source of food, it has spread through waterways and human transport to 10 of Lao's 17 provinces causing many fields to become infested with snails.[16] One of the unintended consequences of this alien species being brought to Laos was the unforeseeable damage to rice paddies, prompting farmers to forgo hand-picking and instead use pesticides for the heavily infested fields leading to chemical runoff.[16] In addition to the chemical pollution in the water threatening the health of aquatic animals and people working in the paddies, many farmers also experienced severe injuries in the field from stepping on the snail shells.[16]

Laos had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 5.59/10, ranking it 98th globally out of 172 countries.[17]

Conservation efforts

Government intervention policies have been implemented to address concerns such as unsustainable timber harvesting, slash-and-burn cultivation, and the allocation of forestland to other purposes such as agriculture, industry, and infrastructure development.[13] The major causes of continued forest degradation from that point onward was not due to policy failure, but rather a lack of multiple factors which include: funding, law enforcement, experienced workers, and organization in the economic sector.[13] Despite all this, there have been other policy attempts and interventions that have been successful in aiding the problem. Reducing the rural population, allowing for tree plantation development, and transitioning from upland rice cultivation to commercial market oriented agricultural practices, contributed to the efforts increasing the amount of forest coverage in Laos.[18] Of the commercial market oriented agricultural practices, the one that saw great success in forest coverage increase is linked to the Southern region's rubber plantations, which has been increasing in number due to rubber being a valuable commodity giving farmers incentive to plant more trees.[15] While it did increase forest coverage, native forests and shifting cultivation lands were subject to change and decline as they transformed into rubber plantations especially during the boom periods of rubber prices, altering the overall biodiversity in the ecosystem.[15]

Government policies

As a means of regulating the country's environmental degradation, the Laos government implemented a new article to the Environmental Protection Law in 2013 that requires the natural resources and environment sector to develop a report every three years to assess the current state of the environment.[19] Amidst the implementation of new laws, however, to regulate the logging industry, there has not been much transparency regarding the provincial government's involvement with the smuggling and foreign investors.[20] Despite implementing the national export ban on timber in 2016, logs are still being smuggled on a regular basis to Lao's neighboring countries, particularly China and Vietnam to be used as materials for luxury furniture.[21] An anonymous witness account revealed that particular provincial governors are safeguarding the hidden illegal lumber, manipulating the reports, and hiding the total number of seized logs to protect the interests of their foreign investors.[21] As such there seems to be a lack of oversight in the ongoing matter.[20]

NGOs and activism

USAID also implemented a program called Lowering Emissions in Asia's Forests (LEAF) from 2011 to 2016 to reduce greenhouse gases and minimize the consequences of deforestation.[22] While USAID LEAF was overseeing one of the National Biodiversity Conservation Area (NBCA) in Nam Xam, Laos, Climate Protection Through Avoided Deforestation (CliPAD) also simultaneously initiated their project in the Nam Et-Phou Louey National Protected Area (NPA) which provided a complementary foundation for USAID LEAF to work upon.[22] USAID LEAF worked in conjunction with the CliPAD project to provide participatory land use planning as well as animal husbandry to prepare the communities for future provincial REDD+ strategies.[22] In introducing participatory land use planning into the provinces, districts developed management plans to allocate natural resources or approved land in a substantially more eco-friendly manner by allowing for better community security and conditions over forest resources.[22] They also were involved in monitoring livestock management for quality over quantity, and in doing so decreased the concerns of excessive forest grazing while collectively increasing community income.[22] They also were involved in monitoring livestock management for quality over quantity, and in doing so decreased the concerns of excessive forest grazing while collectively increasing community income. However, due to a lack of strong political leadership, the collaborative efforts between LEAF and CliPAD were impeded, resulting in LEAF downsizing the scope of the programs and processes.[22] Furthermore, constant regulatory and legislative changes continued to occur in the national and provincial levels, which discouraged the plans of LEAF, but ultimately shifted the focus more on the local level leading to successful outcomes with local stakeholders.[22]

Funded by the German government through the KfW development bank, the GIZ CliPAD project oversaw the creation of a national and provincial REDD+ framework through local-level mitigation measures and sustainable financing models.[23] Similarly to the USAID LEAF project, it provided support through capacity building measures such as conducting participatory land use planning in 87 villages.[23] In addition, it arranged law enforcement training for 162 officers from the Provincial Office of Forest Inspection as a means to effectively deal with poachers and illegal logging.[23] Local communities were prompted to apply the learned sustainable practices regarding natural resource management and explore alternative means of income, to reduce the dependency on the environment's natural resources.[23] In addition to the capacity building measures, CliPAD also provided support for establishing the necessary legal framework to launch REDD+ by aiding in the forest law revision process.[23]

Area and boundaries

Area:

total: 236,800 km²

land: 230,800 km²

water: 6,000 km²

Area - comparative: slightly larger than the US state of Minnesota

slightly smaller than half of the Canadian territory of the Yukon

slightly smaller than the United Kingdom

Land boundaries:

total: 5,083 km

border countries: Myanmar 235 km, Cambodia 541 km, the People's Republic of China 423 km, Thailand 1,754 km, Vietnam 2,130 km

Coastline: 0 km (landlocked)

Elevation extremes:

lowest point: Mekong River 70 m

highest point: Phou Bia 2,817 m

See also

References

- ^ Overland, Indra et al. (2017) Impact of Climate Change on ASEAN International Affairs: Risk and Opportunity Multiplier, Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) and Myanmar Institute of International and Strategic Studies (MISIS).

- ^ "Laos Environmental problems & Policy". United Nations Encyclopedia of the Nations. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Energy & Environment for Sustainable Development". United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 11 March 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ Buncombe, Andrew (20 April 2011). "Mekong ecology in the balance as Laos quietly begins work on dam". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 23 April 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Vietnam worries about impacts from Laos hydroelectric project". Voices for the Laotian Who do not have Voices. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Laos to keep building dams despite negative impacts". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ Osborne, Milton (29 June 2011). "Mekong dam plans threatening the natural order". The Australian.

- ^ Environmental Investigation Agency (26 September 2012) "Laos' forests still falling to 'connected' businesses"

- ^ "U.S. furniture demand drives illegal logging in Laos". illegal-logging.info. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ CleanBiz.Asia News (31 July 2011) "Vietnam army accused of illegal timber trading in Laos" http://www.cleanbiz.asia/news/vietnam-army-accused-illegal-timber-trading-laos#.VKmlVKLZqSo[permanent dead link]

- ^ Radio Australia News (3 October 2012) "Laos failing to act on illegal logging, says environmental agency"

- ^ "Illegal Logging Increasingly Prevalent in Laos". voanews.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ a b c Kim, Se Bin; Alounsavath, Oupakone (2015-03-13). "Forest policy measures influence on the increase of forest cover in northern Laos". Forest Science and Technology. 11 (3): 166–171. doi:10.1080/21580103.2014.977358. ISSN 2158-0103. S2CID 140650841.

- ^ a b c Nguyen, Trung Thanh; Do, Truong Lam; Grote, Ulrike (2018-07-20). "Natural resource extraction and household welfare in rural Laos" (PDF). Land Degradation & Development. 29 (9): 3029–3038. doi:10.1002/ldr.3056. ISSN 1085-3278.

- ^ a b c d e f Clarke, Kenneth; Ostendorf, Bertram; Lewis, Megan; Phompila, Chittana; Phompila, Chittana; Lewis, Megan; Ostendorf, Bertram; Clarke, Kenneth (March 2017). "Forest Cover Changes in Lao Tropical Forests: Physical and Socio-Economic Factors are the Most Important Drivers". Land. 6 (2): 23. doi:10.3390/land6020023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pallewatta, Nirmalie Alexis T. Gutierrez; Reaser, Jamie K.; Gutierrez, Alexis T. (2003). "Invasive Alien Species in South-Southeast Asia" (PDF). www.doi.gov. The Global Invasive Species Programme. Retrieved 2018-12-15.

- ^ Grantham, H. S.; Duncan, A.; Evans, T. D.; Jones, K. R.; Beyer, H. L.; Schuster, R.; Walston, J.; Ray, J. C.; Robinson, J. G.; Callow, M.; Clements, T.; Costa, H. M.; DeGemmis, A.; Elsen, P. R.; Ervin, J.; Franco, P.; Goldman, E.; Goetz, S.; Hansen, A.; Hofsvang, E.; Jantz, P.; Jupiter, S.; Kang, A.; Langhammer, P.; Laurance, W. F.; Lieberman, S.; Linkie, M.; Malhi, Y.; Maxwell, S.; Mendez, M.; Mittermeier, R.; Murray, N. J.; Possingham, H.; Radachowsky, J.; Saatchi, S.; Samper, C.; Silverman, J.; Shapiro, A.; Strassburg, B.; Stevens, T.; Stokes, E.; Taylor, R.; Tear, T.; Tizard, R.; Venter, O.; Visconti, P.; Wang, S.; Watson, J. E. M. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity - Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1). doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ^ Bin, Kim Se; Alounsavath, Oupakone (2016-01-18). "Factors influencing the increase of forest cover in Luang Prabang Province, Northern Laos". Forest Science and Technology. 12 (2): 98–103. doi:10.1080/21580103.2015.1075437. ISSN 2158-0103.

- ^ Environmental Protection Law (Revised). Vientiane, Laos: National Assembly of Laos. 2012. p. 10.

- ^ a b "Laos: Illegal Timber Exports | Global Legal Monitor". www.loc.gov. Johnson, Constance. 2016-12-16. Retrieved 2018-10-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b "Logging Continues in Laos as Provinces Ignore Export Ban". Radio Free Asia. Retrieved 2018-12-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Lowering Emissions in Asia's Forests". Winrock International.

- ^ a b c d e Kallabinski, Jens; Koch, Sebastian (April 2017). "Climate Protection Through Avoided Deforestation [Fact Sheet]" (PDF). Giz. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 8, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

"Laos". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, n.d. Web. 13 Nov. 2016.

Kittikhoun, Anoulak. "Small State, Big Revolution: Geography and the Revolution in Laos". Theory & Society 38.1 (2009): 25-55. Print.

Savada, Andrea Matles, et al. Laos : A Country Study. 3rd ed. ed. Washington, DC: Washington, DC : Federal Research Division, Library of Congress : For sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. G.P.O, 1995. Print.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Laos: A Country Study. Federal Research Division.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Laos: A Country Study. Federal Research Division. This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.