Kim family (North Korea): Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Reverted Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

m Kkkk8901 moved page Kim family (North Korea) to Kim Dynasty (North Korea): Ten Principles for the Establishment of a Monolithic Ideological System 10th Article 10 Paragraph 2 |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 13:32, 28 September 2021

| Kim Dynasty Mount Paektu bloodline | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | North Korea |

| Place of origin | Mangyongdae, Pyongyang |

| Founded | 9 September 1948 |

| Founder | Kim Il-sung |

| Current head | Kim Jong-un |

| Titles | Supreme Leader of North Korea |

| Style(s) |

|

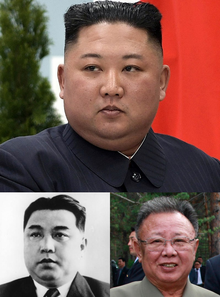

| Members | Kim Il-sung, Kim Jong-il, Kim Jong-un |

| Connected members | Kim Il-sung's wives: Kim Il-sung's sons:

Kim Il-sung's daughters:

Kim Jong-il's wives: Kim Jong-il's sons: Kim Jong-il's daughters:

Kim Jong-un's wife: Ri Sol-ju |

| Traditions | Juche |

| Estate(s) | Residences of North Korean leaders |

| (Mount) Paektu bloodline | |

| Chosŏn'gŭl | |

|---|---|

| Hancha | |

| Revised Romanization | Baekdu-hyeoltong |

| McCune–Reischauer | Paektu-hyŏlt'ong |

|

|---|

|

|

The Kim Dynasty referred to as the Mount Paektu bloodline in the ideological discourse of the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK), is a three-generation lineage of North Korean leadership descending from the country's first leader, Kim Il-sung. In 1948, Kim Il-sung came to rule the North after the end of Japanese rule in 1945 split the region. He began the Korean War in 1950 in a failed attempt to reunify the Korean Peninsula. In the 1980s, Kim Il-sung had developed a cult of personality closely tied to the North Korean state philosophy of Juche. Following his death in 1994, Kim's cult of personality was passed on to his son, Kim Jong-il and then to his grandson Kim Jong-un.

In 2013, Clause 2 of Article 10 of the "Ten Principles for the Establishment of a Monolithic Ideological System" adopted by the government, states that the Party and revolution must be carried "eternally" by the "Paektu bloodline".[1]

Overview

Unlike governance in other current or former socialist or communist republics, North Korea's governance is comparable to a royal family; a de-facto absolute monarchy.[2] The Kim family has ruled North Korea since 1948[3] for three generations,[4] and still little about the family is publicly confirmed.[5] Kim Il-sung rebelled against Japan's rule of Korea in the 1930s, which led to his exile in the Soviet Union. Korea was divided after Japan's defeat in World War II. Kim came to lead the Provisional People's Committee for North Korea (a Soviet-backed provisional government), becoming the first premier of its new government, the "Democratic People's Republic of Korea" (commonly known as North Korea), in 1948. He started the Korean War with a massive invasion of the "Republic of Korea" (South Korea) on 25 June 1950 with hopes to militarily reunify the peninsula.[6]

Kim developed a personality cult that contributed to his nearly uncontested 46-year totalitarian rule[6] and extended to his family, including his mother Kang Pan-sok (known as the "mother of Korea"), his brother Kim Yong-ju ("the revolutionary fighter") and his first wife Kim Jong-suk (the "mother of the revolution").[2] The strong and absolute leadership of a solitary great leader, known as the Suryong, is central to the North Korean ideology of Juche.[7] Four years after Kim Il-sung's 1994 death, a constitutional change wrote the presidency out of the constitution and named him as Eternal President of the Republic in order to honor his memory forever.[6] Kim Il-sung was known as the Great Leader,[8] and his eldest son and successor, Kim Jong-il,[6] became known as the Dear Leader[8] and later the Great General.[9] Kim Jong-il altogether had over 50 titles.

Kim Jong-il was appointed to the Workers Party's Politburo (and its Presidium), Secretariat and the Central Military Commission at the 6th Workers Party Congress in October 1980,[10] which formalized his role as heir apparent.[6] He led their military beginning in 1990,[11] and had a 14-year grooming period before he became North Korea's ruler.[2] Kim Jong-il had a sister, Kim Kyung-hee, who was North Korea's first female four-star general[12] and married to Jang Sung-taek, who was the second most powerful person in North Korea before his December 2013 execution for corruption.[13] Kim Jong-il had four partners,[13] and at least five children with three of them.[14] His third and youngest son, Kim Jong-un, succeeded him.[13] Scholar Virginie Grzelczyk wrote that the Kim family represented "one of the last bastions of totalitarianism as well as perhaps 'the first Communist Dynasty'".[15]

The North Korean government denies that there is a personality cult surrounding the Kims. Rather, it claims that the people's devotion to the Kims is a manifestation of genuine hero worship.[16]

The Kim family (Kim Il-sung, Kim Jong-il and Kim Jong-un) has been described as a de facto absolute monarchy[17][18][19] or "hereditary dictatorship".[20]

In 2013, Clause 2 of Article 10 of the new edited Ten Fundamental Principles of the Korean Workers' Party states that the party and revolution must be carried "eternally" by the "Paektu (Kim's) bloodline".[21]

Ancestry

Kim Il-sung was born in Mangyongdae-guyok to Methodist parents.[22] His father Kim Hyong-jik was 15 when he married Kang Pan-sok two years his elder.[23] Kim Hyong-jik had attended a school founded by Protestant missionaries, which influenced his own family. Kim Hyong-jik became a father at the age of 17, and left school to work as a teacher in a nearby school he once attended. He later practiced Chinese herbal medicine as a doctor. Kim Hyong-jik protested against Japanese rule, and was arrested several times for his activism. He was a founding member of the Korean National Association in 1917, participated in the 1919 March 1st Movement, and fled Korea for Manchuria with his wife and young Kim Il-sung in 1920. There is a teacher's college named after him in Pyongyang.[22]

Kim Hyong-jik's own parents, Kim Bo-hyon and Li Bo-ik,[22] were described as "patriots" by the Editorial Committee of the Short Biography of Kim Il Sung.[24]

Kim Il-sung

Kim Il-sung married twice and had six children. He met his first wife, Kim Jong-suk, in 1936, marrying her in 1940. She bore sons Kim Jong-il (born 1941 or 1942) and Kim Man-il (born 1944), and daughter Kim Kyong-hui (born 1946) before dying while bearing a stillborn daughter in 1949. Kim Jong-suk was born 24 December 1917 in Hoeryong in (North) Hamgyo’ng Province. Her family and she fled Korea to Yanji, Jilin (Kirin) Province around 1922.[25] In October 1947, Kim Jong-suk presided over the establishment of a school for war orphans in South P’yo’ngan Province, which became the Mangyo’ngdae Revolutionary School. When the school opened in west Pyongyang one year after its foundation, Kim Jong-suk also unveiled the country's first statue to Kim Il-sung. In 1949, Kim Jong-suk was once again pregnant. She continued public activities, but her health diminished. She died on 19 September 1949 due to complications from pregnancy. Kim Il-sung had three children with his second wife, Kim Song-ae: Kim Kyong-il (born 1951), Kim Pyong-il (born 1953), and Kim Yong-il (born 1955).[26] He had two younger brothers, Kim Chol-ju and Kim Yong-ju and a sister.[25]

When Kim Il-sung's first wife died, Kim Song-ae was not recognized as Kim Il-sung's wife for several years. Neither partnerships had public weddings.[27] Born Kim So’ng-p’al in the early 1920s in South P’yo’ngan Province, Kim Song-ae began her career as a clerical worker in the Ministry of National Defense where she first met Kim Il-sung in 1948. She was hired to work in his residence as an assistant to Kim Jong-suk. In addition to doing secretarial work for the Kims, she also looked after Kim Jong-il and Kim Kyong-hui. After Kim Jong-suk's 1949 death, Kim Song-ae began managing Kim Il-sung's household and domestic life.[28]

In 1953, Kim Song-ae gave birth to her first child with Kim Il-sung, a daughter named Kim Kyong-jin (Kim Kyo’ng-chin). She went on to have at least two other children with him, sons Kim Pyong-il (b. 1954) and Kim Yong-il (b. 1955).[25]

Kim Kyong-hui became North Korea's first female four-star general.[12] Her husband Jang Sung-taek was the second most powerful person in Korea before his December 2013 execution for corruption.[13] Their 29-year-old daughter overdosed on sleeping pills in 2006 while in Paris.[29] It has also been reported that Kim Yong-il, who was dispatched to serve in Germany, died from cirrhosis of the liver in 2000.[30]

Kim Jong-il

Kim Jong-il had four partners,[13] and at least five children with three of them.[14] He married his first wife, Hong Il-chon, at the behest of Kim Il-sung in 1966. They had one daughter, Kim Hye-kyung (born 1968), before divorcing in 1969.[31] He later fathered Kim Jong-nam (born 1971) with his first consort, film star Song Hye-rim. Due to Song being a divorcee, Kim concealed the relationship and son from his father.[32] In 1974, Kim Jong-il married his second wife, Kim Young-suk. They had two daughters, Kim Sol-song (born 1974) and Kim Chun-song (born 1976).[25] Kim Jong-il divorced her in 1977, after she lost his personal interest. In 1980, Kim Jong-il married his third wife, Ko Yong-hui. Ko was the de facto First Lady of North Korea from Kim Jong-il’s becoming of leader in 1994 until her death in 2004. The couple had two sons, Kim Jong-chul (born 1981) and Kim Jong-un (born 1982, 1983, or 1984), and one daughter, Kim Yo-jong (born 1987).[26] After Ko Yong-hui’s death, Kim Jong-il was married to his personal secretary, Kim Ok.[13] The two were married until Kim Jong-il’s death, and did not have any children. The two half-brothers Kim Jong-un and Kim Jong-nam never met, because of the ancient practice of raising potential successors separately.[33][34] From the early 1980s onward, Kim Jong-il dichotomized the Kim Family between its main, or central, branch (won kaji) and its side, or extraneous, branch (kyot kaji). The main branch referred to Kim Il-sung’s family with Kim Jong-suk and publicly included Kim Jong-il and Kim Kyong-hui. The side branch referred to Kim Il-sung’s family with Kim Sung-ae and included the three children from their marriage.[25]

Kim Jong-un's two older brothers were considered "black sheep" of the family.[29] Kim Jong-nam likely fell out of favor when caught in a plot to visit Tokyo Disneyland in 2001,[13][29] though Kim Jong-nam himself stated that he was not favored due to advocating for reform in the government.[35] He had a reputation as a troublemaker within the family,[5] and publicly stated in 2011 that North Korea should transition out of his family's rule.[29] On 14 February 2017, Kim Jong-nam was assassinated with the chemical nerve agent VX at Kuala Lumpur International Airport in Malaysia.[36][37] Two women, an Indonesian and a Vietnamese, smeared the agent on Kim Jong-nam's face; both women were released after it was determined that they had been tricked by North Korean operatives, who had told them that the act was a prank for a Japanese comedy program and that the substance was lotion.[38][39] Four North Koreans fled Malaysia on the day of the murder.[38] Kim Jong-nam was survived by his wife and two children. His son, Kim Han-sol, has also criticized the regime. In an interview with Finnish media in 2012, Kim Han-sol openly criticized the reclusive regime and the government saying that he has always dreamed that one day he would return to his homeland to "make things better". Ever since the death of his father, his whereabouts have been unknown.[40]

The middle son, Kim Jong-chul, was reportedly not considered in succession considerations due to his unmasculine characteristics.[29] He is also known to be reserved.[5]

Kim Jong-un

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2020) |

Kim Jong-un became North Korea's Supreme Leader on 29 December 2011.[26] He married Ri Sol-ju in either 2009 or 2010, and the couple reportedly had a daughter, Kim Ju-ae, in 2012.[13] His sister Kim Yo-jong had fallen out of favor with her brother for a few years but in 2017, she was elevated by Kim Jong-un to the powerful Central Committee of the Workers' Party of Korea. Kim Jong-un made an effort to distinguish himself from the reputations of his father and brothers, and has promoted the image of an academic who possesses a masculine and extroverted demeanor.[5] In April 2020, unconfirmed[41] rumours of Kim Jong-un's death or severe disability following a botched coronary PCI (angioplasty) began to circulate in the world's media. Kim Jong-un was sighted on May 1, 2020 at a ribbon-cutting ceremony to open a new fertilizer factory, but there is talk about him using a body double.[42]

Possible Successors

Power struggles within the family have, in some instances, been violent , with Kim Jong-il's brother-in-law Jang Song-thaek, and Kim Jong-un's half-brother, Kim Jong-nam, having been killed by the regime via execution and assassination, respectively.[43]

Kim Yo-jong

Kim Yo-jong, the younger sister of Kim Jong-un, is considered a "rising star" within North Korean politics.[43] She has been groomed since an early age, and has represented North Korea in the 2018 Winter Olympics in South Korea, becoming the first member of the Kim family to visit since the end of the war, and has also played a key role behind the scenes.[43] She met US President Donald Trump in 2018.

Kim Pyong-il

Kim Pyong-il is the last living son of the country's founder, Kim Il-sung. After losing out to Kim Jong-il, he spent four decades as an ambassador to various European countries, until returning in 2019.[44] He is thought of as having an advantage over Kim Yo-jong thanks to his gender, but simultaneously carrying a disadvantage due to his lack of connections.[44] He has an adult son, Kim In-kang, and an adult daughter, Kim Ung-song.[45]

Unlikely heirs

Kim Jong-chul, the older brother of Kim Jong-un, has been described as "lacking in ambition" and to be more interested in Eric Clapton and playing guitars.[43]

Kim Il-sung's surviving brother, Kim Yong-ju, turned 100 years old in 2020.[46] Yong-ju has two biological and two adopted children.[47]

Kim Jong-un's reported daughter, Kim Ju-ae, is still a young child, as such, she is considered to be ineligible to succeed her father.[48][49]

Family tree

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Paektu Mountain

- List of leaders of North Korea

- North Korean cult of personality

- O family

- Politics of North Korea

- Jeongju Gim (Kim)

References

Citations

- ^ The Twisted Logic of the N.Korean Regime Archived 13 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Chosun Ilbo, 13 August 2013, Accessed date: 11 January 2017.

- ^ a b c "Next of Kim". The Economist. 23 September 2010. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ "Kim tells N Korean army to ready for combat". Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera Media Network. 25 December 2013. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ Mullen, Jethro (9 September 2013). "Dennis Rodman tells of Korea basketball event, may have leaked Kim child's name". CNN. Archived from the original on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d Milevsky, Avidan (12 April 2013). "Dynamics in the Kim Jong Family and North Korea's Erratic Behavior". The Huffington Post. AOL. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Kim Il-Sung (president of North Korea)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2013. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ Lee 2004, p. 1–7.

- ^ a b Choe, Sang-hun (25 October 2013). "Following Dear Leader, Kim Jong-un Gets Title From University: Dr. Leader". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 December 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ Behnke, Alison (2008). Kim Jong Il's North Korea.

- ^ Kim 1982, p. 142.

- ^ "Kim Jong Il (North Korean political leader)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2013. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ a b Bishop, Rachel (31 August 2017). "Mystery deepens over Kim Jong-un's once-powerful aunt and key aide as fears grow she's "critically ill" in hospital". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "North Korea's secretive 'first family'". BBC News Asia. BBC. 13 December 2013. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ a b Choe, Sang-hun; Fackler, Martin (14 January 2009). "North Korea's Heir Apparent Remains a Mystery". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 November 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ Grzelczyk 2012, p. 37.

- ^ Jason LaBouyer "When friends become enemies — Understanding left-wing hostility to the DPRK" Lodestar. May/June 2005: pp. 7–9. Korea-DPR.com. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- ^ Young W. Kihl, Hong Nack Kim. North Korea: The Politics of Regime Survival. Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 2006. p. 56.

- ^ Robert A. Scalapino, Chong-Sik Lee. The Society. University of California Press, 1972. p. 689.

- ^ Bong Youn Choy. A history of the Korean reunification movement: its issues and prospects. Research Committee on Korean Reunification, Institute of International Studies, Bradley University, 1984. Pp. 117.

- ^ Moghaddam, Fathali M. (2018). "The Shark and the Octopus: Two Revolutionary Styles". In Wagoner, Brady; Moghaddam, Fathali M.; Valsiner, Jaan (eds.). The Psychology of Radical Social Change: From Rage to Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-1-108-38200-7.

- ^ "The Twisted Logic of the N.Korean Regime". english.chosun.com. The Chosun Ilbo. 13 August 2013. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Corfield, Justin (2013). Historical Dictionary of Pyongyang. Anthem Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0-85728-234-7.

- ^ Martin 2007, p. 14.

- ^ Editorial Committee for the Short Biography of Kim Il Sung; Chʻulpʻansa, Oegungmun (1973). Kim Il Sung: short biography. Foreign Languages Publishing House. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e "Kim Family". North Korea Leadership Watch.

- ^ a b c "The Kim Family Tree". Time. Time Inc. Archived from the original on 17 January 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ Martin 2007, p. 187.

- ^ "Kim Song Ae (Kim So'ng-ae)". North Korea Leadership Watch. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Shenon, Philip (19 December 2011). "Inside North Korea's First Family: Rivals to Kim Jong-un's Power". The Daily Beast. The Newsweek Daily Beast Company. Archived from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ "The Life and Execution of Kim Hyun". Daily NK. 10 August 2009. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ "Hong Il-ch'o'n (Hong Il Chon) | North Korea Leadership Watch". www.nkleadershipwatch.org. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ "Song Hye Rim (So'ng Hye-rim) | North Korea Leadership Watch". www.nkleadershipwatch.org. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ Demetriou, Danielle (17 February 2017). "Kim Jong-nam received 'direct warning' from North Korea after criticising regime of half-brother Kim Jong-un". The Telegraph. United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ McKirdy, Euan (16 February 2017). "North Korea's ruling family: Who is Kim Jong Nam?". U.S.: CNN. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ "Kim Jong-nam Says N.Korean Regime Won't Last Long". english.chosun.com (in Korean). Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ Park, Ju-min; Sipalan, Joseph (14 February 2017). "North Korean leader's half brother killed in Malaysia". Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ "Kim Jong-un's half-brother 'assassinated with poisoned needles at airport'". The Independent. 14 February 2017.

- ^ a b Kim Jong-nam: Vietnamese woman freed in murder case, BBC News (3 May 2019).

- ^ Hannah Ellis-Petersen, Kim Jong-nam death: suspect Siti Aisyah released after charge dropped, The Guardian (11 March 2019).

- ^ "Kim Han Sol, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un's estranged nephew, tired of life on the run: Reports". The Straits Times. 10 October 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Beresford, Jack (26 April 2020). "North Korea ruler Kim Jong-un 'dead' or in 'vegetative state', according to reports". The Irish Post. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "North Korea state media says Kim Jong Un is working with no days off". 19 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d White, Edward; Manson, Katrina (27 April 2020). "How Kim's sister could be next in line to rule North Korea". www.ft.com. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ a b hermesauto (29 April 2020). "Kim Jong Un's uncle suddenly relevant after four decades abroad". The Straits Times. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ https://nkreports.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/biography-of-kim-pyong-il-nicolas-levi.pdf

- ^ Jeong, Andrew (5 February 2021). "Kim Jong Un's Family Tree: What You Need to Know About North Korea's Dynasty". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ "Kim Yong Ju". The New York Times. 5 July 1972.

- ^ "North Korean leader Kim Jong-un's wife makes first appearance in a year". BBC News. 17 February 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ Mark, Michelle. "What we know about Kim Jong Un's 3 possible heirs". Business Insider. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

Sources

- Grzelczyk, Virginie (Winter 2012). "In the Name of the Father, Son, and Grandson: Succession Patterns and the Kim Dynasty". The Journal of Northeast Asian History. 9 (2). Northeast Asian History Foundation: 35–68. Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- Kim, Nam-Sik (Spring–Summer 1982). "North Korea's Power Structure and Foreign Relations: an Analysis of the Sixth Congress of the KWP". The Journal of East Asian Affairs. 2 (1). Institute for National Security Strategy: 125–151. JSTOR 23253510.

- Lee, Kyo Duk (2004). "The Successor Theory of North Korea". In Son, Gi-Woong (ed.). 'Peaceful Utilization of the DMZ' as a National Strategy (Report). Korean Institute for National Reunification. ISBN 898479225X.

- Martin, Bradley K. (2007). Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-4299-0699-9.

Further reading

- Buzo, Adrian (1999). The Guerilla Dynasty: Politics and Leadership in North Korea. London: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-415-3.

- Lintner, Bertil (2005). Great Leader, Dear Leader: Demystifying North Korea Under the Kim Clan. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. ISBN 978-974-9575-69-7.

External links

Media related to Kim dynasty (North Korea) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kim dynasty (North Korea) at Wikimedia Commons