Battle of Monett's Ferry: Difference between revisions

Add Action at Monett's, paragraph 1. |

Add Action at Monett's, paragraph 2. |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

===Action at Monett's=== |

===Action at Monett's=== |

||

Brigadier General [[Cuvier Grover]]'s XIX Corps division, 3,000 soldiers, had been left to garrison Alexandria during the initial Union advance.{{sfn|Winters|1987|p=334}} After the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Banks ordered three of Grover's regiments to join him at Grand Ecore. These troops arrived under the command of Brigadier General [[Henry Warner Birge]].{{sfn|Brooksher|1998|p=164}} On the morning of 23 April, the wound Franklin received at Mansfield rendered him unfit for duty, so he handed command over to Emory.{{sfn|Winters|1987|p=362}} Emory began his march at 4:30 am and advanced {{cvt|3|mi|km|1}} before his troops ran into Bee's skirmishers, which were driven across the Cane River.{{sfn|Brooksher|1998|p= |

Brigadier General [[Cuvier Grover]]'s XIX Corps division, 3,000 soldiers, had been left to garrison Alexandria during the initial Union advance.{{sfn|Winters|1987|p=334}} After the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Banks ordered three of Grover's regiments to join him at Grand Ecore. These troops arrived under the command of Brigadier General [[Henry Warner Birge]].{{sfn|Brooksher|1998|p=164}} On the morning of 23 April, the wound Franklin received at Mansfield rendered him unfit for duty, so he handed command over to Emory.{{sfn|Winters|1987|p=362}} Emory began his march at 4:30 am and advanced {{cvt|3|mi|km|1}} before his troops ran into Bee's skirmishers, which were driven across the Cane River.{{sfn|Brooksher|1998|p=176}} |

||

Emory's troops saw that they lost the race to the crossing. They faced the apparently strongly-held bluffs on the south bank while realizing there was a Confederate force behind them as well. One Union soldier recalled, "A general despondency pervaded the whole army." Furthermore, the area right in front of the bluff was cleared of trees and under potential crossfire from Confederate artillery. For his part, Bee was startled by seeing 15,000 Union soldiers in front of his force of 2,000. Nevertheless, Bee was determined to hold his ground. He and the other Confederate leaders believed that Monett's Ferry was the only place where the Cane River could be forded.{{sfn|Brooksher|1998|pp=176–177}} |

|||

Banks's advance party, commanded by Brig. Gen. [[William H. Emory]], encountered Brig. Gen. [[Hamilton P. Bee]]'s cavalry division near Monett's Ferry, or Cane River Crossing, on the morning of April 23. Bee had been ordered to dispute Emory's crossing, and he placed his men so that natural features covered both his flanks. Reluctant to assault the rebels in their strong position, Emory demonstrated in front of the Confederate lines. Among the troops supporting Emory in this effort were members of the [[47th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment]], the only regiment from the Keystone State to fight in the Union's 1864 Red River Campaign across Louisiana.<ref>Snyder, Laurie. ''[https://47thpennsylvania.wordpress.com/category/civil-war/louisiana/red-river-campaign/ Red River Campaign (Louisiana, March to May 1864)]'', in ''47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment's Story'', retrieved online March 31, 2017.</ref> |

Banks's advance party, commanded by Brig. Gen. [[William H. Emory]], encountered Brig. Gen. [[Hamilton P. Bee]]'s cavalry division near Monett's Ferry, or Cane River Crossing, on the morning of April 23. Bee had been ordered to dispute Emory's crossing, and he placed his men so that natural features covered both his flanks. Reluctant to assault the rebels in their strong position, Emory demonstrated in front of the Confederate lines. Among the troops supporting Emory in this effort were members of the [[47th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment]], the only regiment from the Keystone State to fight in the Union's 1864 Red River Campaign across Louisiana.<ref>Snyder, Laurie. ''[https://47thpennsylvania.wordpress.com/category/civil-war/louisiana/red-river-campaign/ Red River Campaign (Louisiana, March to May 1864)]'', in ''47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment's Story'', retrieved online March 31, 2017.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 03:54, 24 January 2023

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Djmaschek (talk | contribs) 22 months ago. (Update timer) |

| Battle of Monett's Ferry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War | |||||||

Map shows Monett's Ferry Battlefield core and study areas by the American Battlefield Protection Program. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Nathaniel P. Banks William H. Emory |

Richard Taylor Hamilton P. Bee | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| US Army Department of the Gulf, Red River Expeditionary Force XIII Corps, XIX Corps, Elements of the XVI Corps and XVII Corps from the Army of the Tennessee. plus additional troops | Bee's Cavalry Division: Major’s, Bagby’s, Debray’s, and Terrell’s brigades of cavalry and McMahan’s, Moseley’s, J. A. A. West’s, and Nettles’ batteries | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 25,000 to 30,000 | 2500 to 3000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 200 | 400 | ||||||

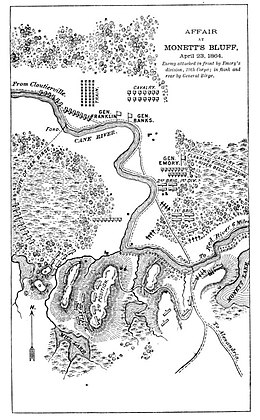

The Battle of Monett's Ferry or Monett's Bluff (23 April 1864) saw a Confederate States Army force led by Brigadier General Hamilton P. Bee attempt to block a numerically superior Union Army column under Brigadier General William H. Emory during the Red River Campaign of the American Civil War. Confederate commander Major General Richard Taylor set a trap for the retreating army of Major General Nathaniel P. Banks near the junction of the Cane River with the Red River. Taylor assigned Bee's troops to plug up the only outlet from the trap while Taylor's other forces closed in from the rear and sides.

Emory responded by sending a brigade to cross the river upstream and turn Bee's right flank. After some fighting, Bee ordered a retreat, fearing that his troops were about to be surrounded. This allowed Banks' army to escape the trap and reach temporary safety at Alexandria, Louisiana. Taylor was so disappointed that he relieved Bee from command, despite the fact that Bee's subordinates agreed with his decision to withdraw. However, the campaign was not yet over.

Background

Campaign

The Red River campaign was undertaken because President Abraham Lincoln wanted a Union foothold in Texas to deter the French-supported ruler Maximilian I of Mexico from meddling in the war. The aim was to establish a corridor up the Red River to Texas and Major General Henry Halleck ordered Banks to lead the operation. Major General William B. Franklin led 17,000 Union soldiers up Bayou Teche to Alexandria, to meet Major General Andrew Jackson Smith with 10,000 troops and Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter's fleet of gunboats and river transports. Meanwhile, Major General Frederick Steele with 15,000 men moved south from Little Rock, Arkansas, planning to rendezvous with Banks near Shreveport, Louisiana. Banks was defeated by Taylor's Confederate army at the Battle of Mansfield on 8 April 1864, though his troops repulsed Taylor's attack at the Battle of Pleasant Hill on 9 April.[1]

At this time, Taylor's superior, General Edmund Kirby Smith took away most of Taylor's infantry to fight Steele's column, leaving Taylor with only 5,200 troops. Banks' army waited at Grand Ecore near Natchitoches until 15 April when it was rejoined by Porter's fleet, which was now returning downriver. Banks decided to abandon the campaign because Smith's troops were already overdue to be returned to Major General William T. Sherman and because Steele was unlikely to join them. Banks' army left Grand Ecore on 21 April heading for Alexandria. Porter struggled to get his fleet downriver because of low water.[2]

Forces

Operations

Banks was unaware that most of Taylor's infantry was no longer present. Historian John D. Winter asserted that Banks might have advanced to capture Shreveport. To prepare for the march to Alexandria, all unneeded blankets, overcoats, and gear were burned by the Union soldiers. The march began on the afternoon of 21 April.[3] The Union cavalry led the way, screening the front, right, and rear. It was followed by, in order, the XIX Corps, XIII Corps, and XVII Corps, while the XVI Corps formed the rearguard.[4] Placed in charge of the march, Franklin demanded that a rapid pace be maintained. By 7 pm on 22 April, the leading element of the column reached Cloutierville, having marched over 40 mi (64 km). Smith's troops arrived at 3 am on 23 April, having skirmished with Confederate pursuers. They also burned every building along the route.[3] One Union soldier wrote, "At one time, I counted 15 burning houses or mills."[4]

In 1864, the Cane River (also called the Old River) split from the Red River near Grand Ecore and flowed generally southeast. The Cane River ran roughly parallel and west of the Red River before flowing into the Red River again near Colfax. After leaving Grand Ecore, Banks' army crossed the Cane River at Natchitoches into what was essentially an island. The only outlet from the island at the southeastern end was at Monett's Ferry.[5]

Taylor was outnumbered by Banks by 25,000 to 5,000, yet he devised a plan to trap the Union army. Taylor knew that Monett's Ferry made an excellent defensive position. On the south bank at the ferry there were high hills, lakes, and forests. By nightfall on 20 April, Taylor had Bee's cavalry division marching toward Monett's Ferry. Taylor ordered Brigadier General James Patrick Major's cavalry to join Bee, while keeping Brigadier General William Steele's cavalry to pursue the Union army.[6] Brigadier General Camille de Polignac's infantry division moved to block a western exit from the island at Cloutierville while Brigadier General St. John Richardson Liddell's force was positioned at Colfax to block Banks' army from crossing to the north bank of the Red River.[7] After Brigadier General Thomas Green was killed at the Battle of Blair's Landing on 12 April,[8] Bee assumed command of Taylor's cavalry corps because he outranked Major who was more experienced.[9]

Battle

Rearguard skirmish

On the evening of 22 April, when Brigadier General John A. Wharton's Confederate cavalry tried to attack the Federal rearguard near Cloutierville, a minor panic ensued when the cavalrymen believed they were being outflanked. Despite the efforts of Lieutenant Colonel D. C. Giddings[5] of the 21st Texas Cavalry Regiment,[10][note 1] the cavalry retreated. This proved to be fortuitous because the Union rearguard was lying in ambush. The Confederates followed at a distance and were able to put out the fires set in Cloutierville by Smith's infantry.[5]

In the predawn hour of 23 April, Captain John M. T. Barnes'[11] 1st Louisiana Regular Battery[12] briefly shelled the Union rearguard south of Cloutierville. When this provoked the Federal cavalry to deploy, they were charged by Colonel George W. Carter's Confederate cavalry brigade and driven back 1,200 yd (1,097 m). However, Union artillery fire caused the Confederate horsemen to pull back and the Union retrograde movement continued.[13]

Action at Monett's

Brigadier General Cuvier Grover's XIX Corps division, 3,000 soldiers, had been left to garrison Alexandria during the initial Union advance.[14] After the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Banks ordered three of Grover's regiments to join him at Grand Ecore. These troops arrived under the command of Brigadier General Henry Warner Birge.[15] On the morning of 23 April, the wound Franklin received at Mansfield rendered him unfit for duty, so he handed command over to Emory.[3] Emory began his march at 4:30 am and advanced 3 mi (4.8 km) before his troops ran into Bee's skirmishers, which were driven across the Cane River.[16]

Emory's troops saw that they lost the race to the crossing. They faced the apparently strongly-held bluffs on the south bank while realizing there was a Confederate force behind them as well. One Union soldier recalled, "A general despondency pervaded the whole army." Furthermore, the area right in front of the bluff was cleared of trees and under potential crossfire from Confederate artillery. For his part, Bee was startled by seeing 15,000 Union soldiers in front of his force of 2,000. Nevertheless, Bee was determined to hold his ground. He and the other Confederate leaders believed that Monett's Ferry was the only place where the Cane River could be forded.[17]

Banks's advance party, commanded by Brig. Gen. William H. Emory, encountered Brig. Gen. Hamilton P. Bee's cavalry division near Monett's Ferry, or Cane River Crossing, on the morning of April 23. Bee had been ordered to dispute Emory's crossing, and he placed his men so that natural features covered both his flanks. Reluctant to assault the rebels in their strong position, Emory demonstrated in front of the Confederate lines. Among the troops supporting Emory in this effort were members of the 47th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, the only regiment from the Keystone State to fight in the Union's 1864 Red River Campaign across Louisiana.[18]

Meanwhile, two other Union brigades went in search of another crossing, one of which successfully found a ford, crossed, and attacked the rebels in their flank, forcing Bee to retreat. Banks's men laid pontoon bridges and, by the next day, had all crossed the river.[19]

Aftermath

The Confederates at Monett's Ferry missed an opportunity to destroy or capture Banks's army. According to General Richard Taylor, the errors made by Bee were as follows: Sending Terrell's and Buschel's regiments back to Beasley to guard a wagon train "For the safety of which I had amply provided for", taking no steps to artificially increase the strength of his position, (Presumably by building earthworks or other fortifications), in massing his troops to the center "Where the enemy were certain not to make any decided effort" instead of concentrating on his flanks, and finally, in retreating his entire force 30 miles to Beasley upon being forced back instead of attacking the disorganized Union column.[20] In Hamilton P. Bee's defense, in addition to fatigue on his horses and men from non-stop fighting since the Battle of Mansfield on April 8, 1864 and being outnumbered 10 to 1 and almost out of supplies and ammunition, there was no time to entrench, and Bee wrote that he chose to save his force in order to fight another day rather than see his entire force enveloped and annihilated with an impossible task resulting in the needless loss of irreplaceable troops.[21] Blame for the Confederate tactical and strategic defeat has been debated ever since.

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ Brooksher states Giddings led the 25th Texas, but according to Oates, he led the 21st Texas Cavalry in Carter's brigade. (Oates, p. 124)

- Citations

- ^ Boatner 1959, pp. 685–687.

- ^ Boatner 1959, p. 687.

- ^ a b c Winters 1987, p. 362.

- ^ a b Brooksher 1998, p. 173.

- ^ a b c Brooksher 1998, p. 174.

- ^ Brooksher 1998, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Brooksher 1998, p. 177.

- ^ Brooksher 1998, p. 157.

- ^ Brooksher 1998, p. 169.

- ^ Oates 1994, p. 176.

- ^ Brooksher 1998, p. 175.

- ^ Bergeron 1989, p. 18.

- ^ Brooksher 1998, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Winters 1987, p. 334.

- ^ Brooksher 1998, p. 164.

- ^ Brooksher 1998, p. 176.

- ^ Brooksher 1998, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Snyder, Laurie. Red River Campaign (Louisiana, March to May 1864), in 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment's Story, retrieved online March 31, 2017.

- ^ John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963, ISBN 0-8071-0834-0, pp. 335, 362

- ^ United States. War Dept, Henry Martyn Lazelle, Leslie J. Perry 'The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies' pg. 580-581

- ^ After action report by Hamilton P. Bee to W. R. Boggs, Chief of Staff, Trans-Mississippi Dept., done on August 17, 1864 at Seguin, Texas in United States. War Dept, Henry Martyn Lazelle, Leslie J. Perry 'The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies' Series I, Volume XXXIV, Part 1, 612-614. [1]

References

- Bergeron, Arthur W. Jr. (1989). Guide to Louisiana Confederate Military Units 1861-1865. Baton Rouge, La.: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2102-9.

- Blessington, Joseph P. (1875). "The Campaigns of Walker's Texas Division". New York, N.Y.: Lange, Little & Co. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- Boatner, Mark M. III (1959). The Civil War Dictionary. New York, N.Y.: David McKay Company Inc. ISBN 0-679-50013-8.

- Brooksher, William Riley (1998). War Along the Bayous: The 1864 Red River Campaign in Louisiana. Washington, D.C.: Brassey's. ISBN 1-57488-139-6.

- Oates, Stephen B. (1994) [1961]. Confederate Cavalry West of the River. Austin, Tex.: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-71152-2.

- Official Records (1891). "The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies' Series I, Volume XXXIV, Part I". U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- Winters, John D. (1987) [1963]. The Civil War in Louisiana. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-0834-0.

Further reading

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service- CWSAC Report Update