Poggio Civitate: Difference between revisions

I added information about the Orientalizing Period. |

|||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

== Orientalizing Period == |

== Orientalizing Period == |

||

=== '''History of Excavations |

=== '''History of Excavations in the Orientalizing Period''' === |

||

In 1970, archaeologists discovered foundations underneath the floor level of the Archaic Building which predated the building.<ref name=":04">{{Cite journal |last=Tuck |first=Anthony |date=2001 |title=An Orientalizing Period Complex at Poggio Civitate (Murlo): A Preliminary View |journal=Journal of the Etruscan Foundation |volume=8 |issue=3 |pages=37-38}}</ref> Subsequently, as excavation continued, archaeologists excavated three buildings: Orientalizing Complex 1 (OC1) in 1970, Orientalizing Complex 2 (OC2) in 1980, and Orientalizing Complex 3 (OC3) from 1996-1999.<ref name=":04" /> However, the discovery of even earlier foundations, structures now called the Early Phase Orientalizing Period Complex (EPOC), showed that OC1, OC2, and OC3 dated to the intermediate phase of the Orientalizing period.<ref name=":14">{{Cite book |last=Tuck |first=Anthony |title=Poggio Civitate |publisher=University of Texas Press |year=2021 |isbn=978-1-4773-2296-3 |location=Austin |pages=25}}</ref> This dating schema was further supported by ceramics discovered in the Orientalizing Complex buildings.<ref name=":14" /> |

In 1970, archaeologists discovered foundations underneath the floor level of the Archaic Building which predated the building.<ref name=":04">{{Cite journal |last=Tuck |first=Anthony |date=2001 |title=An Orientalizing Period Complex at Poggio Civitate (Murlo): A Preliminary View |journal=Journal of the Etruscan Foundation |volume=8 |issue=3 |pages=37-38}}</ref> Subsequently, as excavation continued, archaeologists excavated three buildings: Orientalizing Complex 1 (OC1) in 1970, Orientalizing Complex 2 (OC2) in 1980, and Orientalizing Complex 3 (OC3) from 1996-1999.<ref name=":04" /> However, the discovery of even earlier foundations, structures now called the Early Phase Orientalizing Period Complex (EPOC), showed that OC1, OC2, and OC3 dated to the intermediate phase of the Orientalizing period.<ref name=":14">{{Cite book |last=Tuck |first=Anthony |title=Poggio Civitate |publisher=University of Texas Press |year=2021 |isbn=978-1-4773-2296-3 |location=Austin |pages=25}}</ref> This dating schema was further supported by ceramics discovered in the Orientalizing Complex buildings.<ref name=":14" /> |

||

Revision as of 19:20, 8 May 2023

Murlo | |

View of Poggio Civitate (left), Poggio Aguzzo (center) and Murlo (right). | |

| Location | Murlo, Siena, Italy |

|---|---|

| Region | Tuscany |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Abandoned | late sixth century BC |

| Periods | Orientalizing period - Archaic period |

| Cultures | Etruscan civilization |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1966-present |

| Archaeologists | Kyle Meredith Phillips Jr.; Erik Nielsen; Anthony Tuck |

| Condition | ruined |

| Public access | yes |

| Website | The Poggio Civitate Archaeological Project |

Poggio Civitate is a hill in the commune of Murlo, Siena, Italy and the location of an ancient settlement of the Etruscan civilization. It was discovered in 1920, and excavations began in 1966 and have uncovered substantial traces of activity in the Orientalizing and Archaic periods as well as some material from both earlier and later periods.

Iron Age

Limited Iron Age (Villanovan) architectural and artifactual evidence suggests that there was Iron Age activity and possibly Iron Age occupation at Poggio Civitate during the mid-8th to early 7th centuries BCE.[1][2]

Iron Age Hut

On an area of the site known as Civitate C, a trench labeled Civitate C 7 (CC7) uncovered the post holes and countersunk floor of a curvilinear, ovoid hut of approximately five by seven meters.[3][4] After its period of use, this structure appears to have been reused as a midden, including a deposit of over one thousand murex shells (Bolinus brandaris), possibly used for small scale dye production.[5][6][7]

Iron Age Artifacts

Artifacts, such as fragments of coil-made pottery, an Iron Age technology, suggest a presence of Iron Age Etruscans on Poggio Civitate.[8][9][10][11] An impasto handle fragment has a typology and decorations reminiscent of Iron Age (Villanovan) cover bowls for biconical urns.[12] There are also fragments of bronze fibulae of an Iron Age design.[13][14][15][16] These artifacts have been recovered from an area of the site known as Civitate A as well as from a trench labeled Tesoro 27, which sounded below the ground level of the Intermediate Orientalizing Complex 2(OC2)/Workshop.[17][18][19]

Orientalizing Period

History of Excavations in the Orientalizing Period

In 1970, archaeologists discovered foundations underneath the floor level of the Archaic Building which predated the building.[20] Subsequently, as excavation continued, archaeologists excavated three buildings: Orientalizing Complex 1 (OC1) in 1970, Orientalizing Complex 2 (OC2) in 1980, and Orientalizing Complex 3 (OC3) from 1996-1999.[20] However, the discovery of even earlier foundations, structures now called the Early Phase Orientalizing Period Complex (EPOC), showed that OC1, OC2, and OC3 dated to the intermediate phase of the Orientalizing period.[21] This dating schema was further supported by ceramics discovered in the Orientalizing Complex buildings.[21]

The Early Phase Orientalizing Complex

Once archaeologists differentiated between the Early and Intermediate Phase Orientalizing complexes, they attributed two buildings to the Early Phase Orientalizing Period. The first building was identified as Early Phase Orientalizing Complex 4 (EPOC4). It is located in the west part of the site, and materials found at the site suggest it has a domestic function.[21] Early Phase Orientalizing Complex 5 (EPOC5) is located to the southeast of EPOC4. Unfortunately, EPOC5 is poorly preserved, so the function of the building is more difficult to deduce.[21]

Orientalizing Complex 3/Tripartite Building (OC3)

The Orientalizing Complex 3 (OC3/Tripartite Building) was built around 650 BCE. The building has a terracotta roof, which was relatively rare for Tripartite style buildings during this time.[22] “The building has three adjacent rooms, oriented roughly E-W, measuring roughly 9.2 x 23.2 m, with exceptionally wide rubble foundations (W 1.5 m)”[23]. Tripartite buildings have a long rectangular shape that is divided into thirds. Each section of the building is divided by pillars. These pillars create three distinct halls. The walls of OC3 are much thicker than OC1 and OC2, hinting at the fact that the builders might have been unsure about the thickness of walls needed to support the terracotta roof.[24] Therefore OC3 could have been built before OC1 and OC2. Similar styles of terracotta roofs across OC1 and OC3 allude that both buildings were built during a similar time and supplied by the local workshop. The building itself is believed to have been used as a temple or religious building due to the floor plan being very similar to that of Etruscan temples, with a large central room twice the size of the two side rooms. Items such as bucchero vessels with muluvanice-inscriptions, burned animal bones, and seeds found in and near OC3 also support the theory that the building was an early version of a temple.[25] The OC3/Tripartite building was destroyed in a fire in 590-580 BCE, the same fire also destroyed OC1 and OC2.[26]

Industries in Non-elite Orientalizing Architecture

Evidence was found for several industries in the non-elite Orientalizing Period architecture in the area known as Civitate A. Evidence of processing and carving of animal carcasses has been found near Structure 1 of Civitate A, including worked bone and antlers that show evidence of the striations associated with a rigid saw. 15 spindle whorls[27] of varying sizes were discovered, which were likely used to produce the thread of wool due to the amount of sheep bones discovered nearby. A singular loom weight[28] was discovered in Structure 1. 31 rocchetti,[29] which were used as spools or bobbins in textile work, were also found. Evidence of metal working is represented by the large quantity of slag[30] found near Structure 1. Crucible fragments, a possible furnace, and bronze artifacts such as pins and fibulae[31] were found that show more evidence of metal working in Civitate A.[32]

Archaic Period

The Archaic period, lasting from the 7th century BCE to the mid 6th century BCE, saw an enhanced revitalization of the previously destroyed building complex of the Orientalizing period.[33] Prior to the creation of the new Archaic building, survivors salvaged any debris that remained and flattened the plateau, known as Piano Del Tesoro, or the "Plateau of the Treasure", to begin construction.[34][33] The monumental building included elaborate decorations, including frieze plaques with motifs such as a banquet and horse race, gutters, and terracotta statues such as the “Cowboy” akroterion and sphinx akroterion.[35] In the mid-6th century BCE, the building was destroyed and abandoned.[33]

The Archaic Phase Building

Sometime in the early 6th century BCE a "monumental complex" was constructed on Poggio Civitate, a term for large buildings or sets of buildings with uncertain function found in Etruscan architecture. It consisted of a courtyard surrounded by a colonnade on three sides and probably a shrine and a possible throne on the fourth.[36] Surrounding the colonnade and courtyard were four blocks of rooms.[36] The rooms were covered by 30,000 square feet (2,800 m2) of terracotta roof tiles.[36]

The building was elaborately decorated. The walls and rooflines contained terracotta statues (including the Murlo cowboy) and friezes.[36] One of these friezes depicts a banquet scene common to art of archaic Italy.[36] The scene depicts four servants serving guests reclining on couches as well as hunting dogs.[36] One guest is playing the lyre while a mixing bowl is situated in the center of two couches.[36] Others depict mythical, divine, or real humans and animals.[36] Also depicted are processions, horse races, and warriors marching behind leaders in chariots.[36] Some scenes depict ceremonies and business being conducted, in one of these a human figurine carries a lituus, a curved staff serving as a symbol of office in Etruria and Latium.[36]

The use of the building is unclear. One possible use was as the residence of the ruler or leading family of the town. Fine pottery fragments were discovered, so symposia and banquets likely occurred at the site.[36]

Activities and Industries in the Archaic Phase Building

A few common examples of artifacts are found in the Archaic Building which might indicate activities and industries of the building, despite its complicated stratigraphy and excavation history.[37] Grinding stones are also present at the site, suggesting processing of perhaps grain or other products.[38] Slingstones and arrow tips were found, possibly indicating that the residents of Poggio Civitate manufactured or at least used these weapon types.[39][40] There are signs that banquets were held within the building, attested by the iconography of a terracotta frieze plaque found that showcases this kind of event.[41] Another set of artifacts found within the Archaic Building was bucchero, a more expensive banqueting ware.[42] There were also signs of impasto wares.[43] Additionally, there were remnants found of what seems to be a stone altar.[44] This was found near the southern wall of the Archaic Building, which is where an earlier structure, called the Orientalizing Complex 3/Tripartite Building was located, which scholars believe to be a focus of religious activity.[45] Both loom weights and spindle whorls were found at the site, indicating that it is likely that textiles were commonly produced at Poggio Civitate.[46][47]

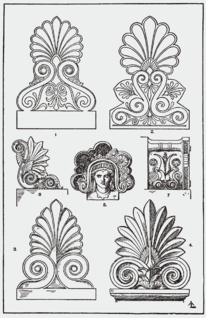

Archaic Akroteria (Acroteria)

An akroterion (acroterion) is an architectural ornament. In the archaic period, akroterion consisted of a highly decorative crowning located on the peaks and at angles or corners of buildings.[48] Akroteria were crafted out of a variety of materials, including marble, terracotta, and limestone but references to bronze akroteria have also been discovered.[48] Humanoid elements such as fragments of ears made of terracotta can even be found among the archaic artifacts of Poggio Civitate.[49] Artistic elements on akroteria can be first seen as far back as the 7th century BC.[48] In earlier periods, some of what became archaic akroteria, were seen as terracotta antefixes on edges and corners of roofing, but later development brought full fledged statues and highly artisitic design on these corners and peaks.[50] The famous "Murlo Cowboy" akroteria of Poggio Civitate is an example of archaic acroteria that is a decorative statue.[51] It has also been argued that these akroteria statues created an aura of power and wealth that would impact both those living within and around the buildings they adorned.[51]

Archaic Period Building Sima

There have been over 206 fragments of both lateral and raking sima found in the debris of the Archaic Building and both sima types prove to be scattered throughout the site.[52] Poggio Civitate's Archaic Building sima was made from terracotta pressed into molds. It was adorned with detailed faces or animals in the Archaic style.[52] Many of the lateral sima's was depicted gorgon's as well as molds of water spouts and human heads.[53] On the contrary, the raking sima was decorated with animals.[54] These also edged the gables. There were many different representations throughout the site, some of which might be mythological, which are said to be used to protect the buildings from evil.[55] The simas were attached to the wooden roof beams of the Archaic Building to ensure their security and they were placed around the structure with the decorative details facing downward so all entering the building could see.[56] Lateral sima was the most common type from the Archaic Period at the Poggio Civitate site due to the fact that the Archaic building had more lateral areas than area on roof gables to which sima was attached.

Archaic Seated Figures Frieze Plaque

At the dig site of the Archaic Building on the plateau of Piano del Tesoro, a terracotta frieze plaque was found depicting figures seated one in front of another.[57] This frieze plaque, along with the other found at this site, are dated to 600 BCE-535 BCE.[58] The plaque measures about 0.239 meters in height, 0.543 meters in width, and has a thickness of about 0.025 meters.[58] Like many frieze plaques dated to the Archaic period of Etruscan society, the plaque depicting the seated figures is made of terracotta; more specifically the clay is classified as coarse.[58][59] Oftentimes, these decorative plaques depicted the figures of gods or people worshipping gods.[60]

Assembly Scene

The scene depicted on this particular frieze plaque is viewed as a scene of an assembly.[57] Archaeologists and researchers can definitively classify this scene as an assembly based on the furniture the figures are seated on. The third figure from the right is sitting on a cylindrical throne, which is a distinction of status from the 7th century BCE.[60] Along with this unique throne style, the remainder of the seated figures are seated on folding stools with four double-curved animal legs.[59] These stools are staples of assembly scenes involving both gods and mortals.[60] Based on these details and depiction of figures, an interpretation has been made that the plaque contains representations of the gods Zeus, Hera, and Athena.[61] These three gods are commonly depicted together in various pieces from this same time period.[61] Anthony Tuck, an archaeologist from the University of Massachusetts who excavates the site, has argued that the assembly scene depicts a hieros gamos.[62] Although figures on frieze plaques such as this one often portray deities, it is important to note that there has been no concrete evidence suggesting that this particular assembly scene is an ancient Etruscan or Italian mythological representation.[63]

The Destruction

The Archaic Phase Building of Poggio Civitate, which had been recently constructed, was destroyed in the mid- to late sixth century BCE in a single event, along with the rest of the settlement at Poggio Civitate.[64][65] This destruction was thorough and complete, and parts of the structure and the roof of the Archaic Phase Building were broken and scattered in wells and depressions across the site.[66] There is evidence that certain parts of the Archaic Phase Building were targeted in this destruction, specifically decorative architectural terracotta features (frieze plaques, sima, and akroteria) depicting the elite family that most likely ruled Poggio Civitate towards the end of the Archaic Period.[65] These aspects were largely parts of the roof structure and they were destroyed systematically. They were then discarded to the western side of the Archaic Phase Building in a pit in the ground.[65] More general pieces of the destroyed building, especially broken roof tiles and other debris were thrown into wells discovered west of the building; one of these wells additionally contained a partially destroyed travertine altar that weighed more than 300 kilograms.[65][67] The walls of the building were left either partially destroyed, or vulnerable to the elements and then decayed over time.[65] There was a single known casualty of the destruction: one fragment of a human skull, who is assumed to have been an individual killed during the event, was found lying outside one of the wells filled with debris.[65][68]

Possible Theories:

Connections have been made between the destruction of the Archaic Phase Building and a growing concern about the defense of the settlement: some scholars even point out that the structures (like watchtowers) that were being constructed resemble defensive buildings of colonial America.[65] There is also evidence, in the form of wells that were constructed immediately prior to the destruction, that there was an sharp increase in people moving closer to the Archaic Phase Building, perhaps for security or protection from outside threat.[65] It is possible that this was a result of prior failed attacks on the settlement. One theory for the complete destruction of Poggio Civitate is a political interaction. The sixth century BCE was a violent time in Roman history; Etruscan, Latin, and Umbrian city-states that were most commonly ruled by elite families were engaged in constant conflict.[65] These elite families wanted to extend their power, and often absorbed or destroyed neighboring city-states. Some scholars believe that Chiusi, one example of these rising city-states, was responsible for the destruction at Poggio Civitate because of a series of Tarqiunian style tomb paintings discovered in Chiusi that implied violence between rivaling city-states (possibly Poggio Civitate).[65] The specific targeting of artwork portraying the supposed elite family of Poggio Civitate during the destruction also adds potential credibility to this theory. Another theory that exists is that a ritual destruction of Poggio Civitate occurred. This theory is derived from evidence that an agger, or an artificial mound of earth, was constructed after the destruction of the Archaic Phase Building as a symbolic marker.[69] This agger could have been separating the destroyed structures and uninhabitable land from the land that could continue to be inhabited after the destruction, and that the people of Poggio Civitate themselves had participated in this ritualistic destruction, or "unfounding" of their settlement.[69] This could offer another explanation for the targeting of artwork depicting the elite family; the people of Poggio Civitate wanted to destroy and rebuild their settlement under new leadership. One scholar, Nancy de Grummond, points out that certain aspects of the Archaic Phase Building (the walls) were still standing near the agger at the time of discovery, possibly revealing that the destruction was not so thorough after all and could have been motivated by something other than violence or conquest as the first theory suggests.[69] There is no concrete evidence definitively proving any hypothesis.

Abandonment:

After the final, thorough destruction of Poggio Civitate, it is thought that the site was never reoccupied. There is evidence of people passing through the area, such as a couple Medieval coins and pottery fragments, but no evidence of any type of permanent settlement post-destruction.[65][70][71] Nancy de Grummond argues instead that the agger was constructed after the destruction of the Archaic Phase Building on Piano del Tesoro, and could indicate that there was a plan for people to occupy the hill post-destruction, or that people may have in fact continued to inhabit it.[69] This theory is difficult to prove because descriptions and surveys of the agger contain many inconsistencies. So far, there has been no conclusive evidence of settlement on Piano del Tesoro after the destruction of Poggio Civitate, but the volume of artifacts found at the site decreases significantly after the date of destruction.

Directors of excavation

- Kyle M. Phillips – Bryn Mawr College (1966-1973)[72]

- Erik Nielsen & Kyle M. Phillips (1973-1981 co-directors)

- Erik Nielsen – President of Franklin University Switzerland (1973-1996)

- Erik Nielsen & Anthony Tuck (1997-2011 co-directors)

- Anthony Tuck – Associate Professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst (2011–Present)[73]

Further reading

O'Donoghue, E. “The Mute Statues Speak: The Archaic Period Acroteria from Poggio Civitate (Murlo).” Taylor & Francis. Accessed April 11, 2023. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1179/1461957112Y.0000000029.

Delivorrias, A. "Acroterion." Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press. Date of access 2 April 2023, https://www-oxfordartonline-com.holycross.idm.oclc.org/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000000376

Rendeli, Marco. "Acquarossa." Grove Art Online. 2003; Accessed 2 April 2023. https://www-oxfordartonline-com.holycross.idm.oclc.org/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000000368.

Rendeli, Marco. "Poggio Civitate." Grove Art Online. 2003; Accessed 2 April 2023. https://www-oxfordartonline-com.holycross.idm.oclc.org/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000068269.

References

- ^ Coppolaro Nowell, Tuck, and Soederberg. L'avventura etrusca di Murlo : 50 anni di scavi a Poggio Civitate = 50 years of excavations at Poggio Civitate = Etruscan Murlo. pp. 98–100. ISBN 978-88-98816-31-6. OCLC 1045338747.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tuck, Anthony. Poggio Civitate (Murlo). pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-4773-2296-3. OCLC 1343103543.

- ^ "Civitate C 7".

- ^ Tuck, Anthony (2021). Poggio Civitate (Murlo). Austin. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-4773-2296-3. OCLC 1255711175.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Murex Shell Fragments".

- ^ "Murex Shell Fragments".

- ^ Tuck, Anthony (2021). Poggio Civitate (Murlo). Austin. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-1-4773-2296-3. OCLC 1255711175.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Impasto Vessel Fragments".

- ^ "Storage Vessel Rim Fragment".

- ^ "Coil-made Rim Fragments".

- ^ "Carinated impasto bowl".

- ^ "Decorated Impasto Bowl Handle".

- ^ "Bronze Leech Fibula Fragment".

- ^ "Incised Bronze Leech Fibula Fragment".

- ^ "Bronze Leech Fibula Fragment".

- ^ "Bronze Leech Fibula Fragment".

- ^ "Civitate A".

- ^ "Tesoro 27 (Trench)".

- ^ Collins, Abbey (1988). "AC III".

- ^ a b Tuck, Anthony (2001). "An Orientalizing Period Complex at Poggio Civitate (Murlo): A Preliminary View". Journal of the Etruscan Foundation. 8 (3): 37–38.

- ^ a b c d Tuck, Anthony (2021). Poggio Civitate. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4773-2296-3.

- ^ Winter, Nancy A. (2019-11-05). "Finding a Home for a Roof in Production within the Building History of Poggio Civitate (Murlo)". Etruscan Studies. 22 (1–2): 65–94. doi:10.1515/etst-2019-0004. ISSN 2163-8217.

- ^ Tuck, Anthony; Wallace, Rex (2013-01-01). "Letters and Non-Alphabetic Characters on Roof Tiles from Poggio Civitate (Murlo)". Etruscan Studies. 16 (2). doi:10.1515/etst-2013-0014. ISSN 2163-8217.

- ^ Tuck, Anthony; Wallace, Rex (2013-01-01). "Letters and Non-Alphabetic Characters on Roof Tiles from Poggio Civitate (Murlo)". Etruscan Studies. 16 (2). doi:10.1515/etst-2013-0014. ISSN 2163-8217.

- ^ Tuck, Anthony; Wallace, Rex (2013-01-01). "Letters and Non-Alphabetic Characters on Roof Tiles from Poggio Civitate (Murlo)". Etruscan Studies. 16 (2). doi:10.1515/etst-2013-0014. ISSN 2163-8217.

- ^ Winter, Nancy A. (2019-11-05). "Finding a Home for a Roof in Production within the Building History of Poggio Civitate (Murlo)". Etruscan Studies. 22 (1–2): 65–94. doi:10.1515/etst-2019-0004. ISSN 2163-8217.

- ^ "Spindle Whorl".

- ^ "Loom Weight Fragment".

- ^ "Rocchetto Fragment".

- ^ "Terra Cotta Pan Tile Fragment with Adhered Slag".

- ^ "Bronze Fibula Fragment".

- ^ Tuck, Anthony; Kreindler, Kate; Huntsman, Theresa. "Excavations at Poggio Civitate (Murlo) During the 2012--2013 Seasons: Domestic Architecture and Selected Finds From the Civitate A Property Zone". Etruscan Studies: Journal of the Etruscan Foundation. 16 (2): 287–306.

- ^ a b c A Companion to the Etruscans, edited by Sinclair Bell, and Alexandra A. Carpino, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2016. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/holycrosscollege-ebooks/detail.action?docID=4189531.

- ^ "The Poggio Civitate Archaeological Project". The Poggio Civitate Archaeological Project. Retrieved 2023-04-25.

- ^ Ginge, Birgitte. American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 97, no. 3, 1993, pp. 583–84. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/506382. Accessed 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Boatwright, Mary; Gargola, Daniel; Lenski, Noel; Talbert, Richard (2012). "Archaic Italy and the Origins of Rome". The Romans: From Village to Empire (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-19-973057-5.

- ^ Tuck, Anthony (2021). Poggio Civitate (Murlo) (Cities and Communites of the Etruscans). University of Texas Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-1477322949.

- ^ "Possible Stone Tool".

- ^ "Slingstones".

- ^ "Iron Arrow Point".

- ^ Tuck, Anthony (2021). Poggio Civitate (Murlo) (Cities and Communities of the Etrsucans). University of Texas Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-1477322949.

- ^ "Bucchero".

- ^ Tuck, Anthony (2021). Poggio Civitate (Murlo) (Cities and Communities of the Etruscans). University of Texas Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-1477322949.

- ^ Tuck, Anthony (2021). Poggio Civitate (Murlo) (Cities and Communities of the Etruscans). University of Texas Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-1477322949.

- ^ Tuck, Anthony (2021). Poggio Civitate (Murlo) (Cities and Communites of the Etrsucans). University of Texas Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-1477322949.

- ^ "Loom Weight".

- ^ "Spindle Whorl".

- ^ a b c Delivorrias, A. (2003), "Acroterion", Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 2023-04-11

- ^ "PC 19670421 from Europe/Italy/Poggio Civitate/Tesoro/Tesoro 1T/1967, ID:20". opencontext.org. Retrieved 2023-04-18.

- ^ Rendeli, Marco (2003), "Poggio Civitate", Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 2023-04-11

- ^ a b O'Donoghue, Eóin (2013-05-01). "The Mute Statues Speak: The Archaic Period Acroteria from Poggio Civitate (Murlo)". European Journal of Archaeology. 16 (2): 268–288. doi:10.1179/1461957112Y.0000000029. ISSN 1461-9571.

- ^ a b Phillips, Kyle Meredith (1993). In the hills of Tuscany : recent excavations at the Etruscan site of Poggio Civitate (Murlo, Siena). Philadelphia, Pa.: University Museum, University of Pennsylvania. ISBN 0-934718-96-2. OCLC 26503692.

- ^ https://opencontext.org/subjects/7bf7d3da-1d48-482f-6fad-ad5252b5f5ed

- ^ "PC 19680674 from Europe/Italy/Poggio Civitate/Civitate A/Civitate A 2H/1968, ID:161". opencontext.org. Retrieved 2023-05-04.

- ^ Spivey, Nigel (April 1996). "Etruria - R. D. De Puma, J. P. Small (edd.): Murlo and the Etruscans: Art and Society in Ancient Etruria. (Wisconsin Studies in Classics.) Pp. xxxi + 251; copiously illustrated. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1994. Cased, £40.50. - M. Blumhofer: Etruskische Cippi: Untersuchungen am Beispiel von Cerveteri. Arbeiten zu Archäologie. Pp. xix + 266; 39 plates. Cologne, Weimar, Vienna: Böhlau Verlag, 1993. Cased, DM 148". The Classical Review. 46 (1): 133–135. doi:10.1093/cr/46.1.133. ISSN 0009-840X.

- ^ Jannot, Jean-René (1995). "Les Étrusques à Murlo: deux livres récents - KYLE MEREDITH PHILLIPS Jr., IN THE HILLS OF TUSCANY. RECENT EXCAVATIONS AT THE ETRUSCAN SITE OF POGGIO CIVITATE (MURLO) (The University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 1993). 146 p. ISBN 0-934718-96-2. - RICHARD DANIEL DE PUMA AND JOCELYN PENNY SMALL (Edt.), MURLO AND THE ETRUSCANS (University of Wisconsin Press, Madison1994). 251 p., 212 ills. ISBN 0-299-13910-7. $45". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 8: 330–334. doi:10.1017/s1047759400016135. ISSN 1047-7594.

- ^ a b Rathje, Annette (2007). "Murlo, Images and Archaeology". Etruscan Studies: Journal of the Etruscan Foundation. 10 – via Umass.edu.

- ^ a b c Tuck, Anthony (2012). "PC 19680271 from Europe/Italy/Poggio Civitate/Civitate A/Civitate A 2/1968, ID:485". Open Context. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b Tuck, Anthony (2012). "19680777.jpg from Europe/Italy/Poggio Civitate/Civitate A/Civitate A 2H/1968, ID:161/PC 19680777". Open Context. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b c Turfa, Jean (2003). "Etruscan". Oxford Art Online. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b Gantz, T.N. (2 May 2023). "Divine Triads on an Archaic Etruscan Frieze Plaque from Poggio Civitate". Studi Etruschi. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ Tuck, Anthony (2006). "The Social and Political Context of the 7th Century Architectural Terracottas at Poggio Civitate (Murlo)". Deliciae Fictiles III. Architectural Terracottas in Ancient Italy: New Discoveries and Interpretations.

- ^ Menichetti, M. (1994). Archaeologia del Potere. Milan.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Nielson, Warden (2017). Etruscology. Alessandro Naso. Boston. pp. Chapter 71. ISBN 978-1-934078-49-5. OCLC 1012851705.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Tuck, Anthony (2021). Poggio Civitate (Murlo). ISBN 978-1-4773-2296-3. OCLC 1255711175.

- ^ "Civitate A 2".

- ^ "Large Worked Stone Fragment (Possible Altar)".

- ^ "Cranium Fragment".

- ^ a b c d NANCY T. DE GRUMMOND (1997-06-01). "POGGIO CIVITATE: A TURNING POINT". Etruscan Studies. 4 (1): 23–40. doi:10.1515/etst.1997.4.1.23. ISSN 2163-8217.

- ^ "Medieval Coin".

- ^ "Medieval Handle Fragment".

- ^ de Puma, Richard; Small, Jocelyn Penny (1993). "Biography of Kyle Meredith Phillips, Jr". Murlo and the Etruscans Art and Society in Ancient Etruria (1st ed.). University of Wisconsin Press. pp. xxvi–xxviii. ISBN 978-0-299-13910-0.

- ^ Tuck, Anthony. Classics Department Biography Page.

External links

- Poggio Civitate excavation project

- Poggio Civitate excavation database

- Harris, W., R. Talbert, T. Elliott, S. Gillies (14 July 2021). "Places: 413216 (Murlo)". Pleiades. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)