Vairocana: Difference between revisions

Add Rocana buddha meaning Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

Vairocana is not to be confused with Vairocana [[Mahabali]], son of [[Virochana]]. Vairocana Mahabali attained to sahaja nirvikalpa samadhi in Yoga Vasishta. |

Vairocana is not to be confused with Vairocana [[Mahabali]], son of [[Virochana]]. Vairocana Mahabali attained to sahaja nirvikalpa samadhi in Yoga Vasishta. |

||

Rocana Buddha is the "enjoyment body" or "Sambhogakaya body" of the tri-kaya of Buddha, while Vairocana Buddha is the "Dharmakaya body". And Shakyamuni Buddha is the " |

Rocana Buddha is the "enjoyment body" or "Sambhogakaya body" of the tri-kaya of Buddha, while Vairocana Buddha is the "Dharmakaya body". And Shakyamuni Buddha is the "Nirmanakaya body" or physical body. |

||

==Literary and historical development== |

==Literary and historical development== |

||

Revision as of 02:15, 25 August 2023

| Vairocana | |

|---|---|

The Spring Temple Buddha, a colossal statue of Vairocana, in Lushan County, Henan, China. It has a total height of 153 meters (502 ft), including the 25 meter (82 ft) lotus throne which the statue stands on. | |

| Sanskrit | वैरोचन

Vairocana |

| Burmese | ဗုဒ္ဓဘုရားရှင် |

| Chinese | 大日如来

(Pinyin: Dàrì Rúlái) 毘盧遮那佛 (Pinyin: Pílúzhēnà Fó) |

| Japanese | 大日如来 (romaji: Dainichi Nyorai) 毘盧遮那仏 (romaji: Birushana Butsu) |

| Korean | 대일여래 大日如来(RR: Daeil Yeorae) 비로자나불 毘盧遮那仏(RR: Birojana Bul) |

| Mongolian | ᠮᠠᠰᠢᠳᠠ ᠭᠡᠢᠢᠭᠦᠯᠦᠨ ᠵᠣᠬᠢᠶᠠᠭᠴᠢ Машид гийгүүлэн зохиогч Masida geyigülün zohiyaghci ᠪᠢᠷᠦᠵᠠᠨ ᠠ᠂ ᠮᠠᠰᠢᠳᠠ ᠭᠡᠢᠢᠭᠦᠯᠦᠨ ᠵᠣᠬᠢᠶᠠᠭᠴᠢ᠂ ᠭᠡᠭᠡᠭᠡᠨ ᠭᠡᠷᠡᠯᠲᠦ Бярузана, Машид Гийгүүлэн Зохиогч, Гэгээн Гэрэлт Biruzana, Masida Geyigülün Zohiyaghci, Gegegen Gereltü |

| Thai | พระไวโรจนพุทธะ (RTGS: Phra wị ro ca na phuth ṭha) |

| Tibetan | རྣམ་པར་སྣང་མཛད་ Wylie: rnam par snang mdzad THL: Nampar Nangdze |

| Vietnamese | Đại Nhật Như Lai 大日如来 Tỳ Lư Xá Na 毘盧遮那 Tỳ Lô Giá Na Phật 毗盧遮那佛 |

| Information | |

| Venerated by | Mahayana, Vajrayana |

| Attributes | Śūnyatā |

Vairocana (also Mahāvairocana, Template:Lang-sa) is a cosmic buddha from Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. Vairocana is often interpreted, in texts like the Avatamsaka Sutra, as the dharmakāya[1][2][3] of the historical Gautama Buddha. In East Asian Buddhism (Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese Buddhism), Vairocana is also seen as the embodiment of the Buddhist concept of śūnyatā. In the conception of the 5 Jinas of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, Vairocana is at the centre and is considered a Primordial Buddha.

Vairocana is not to be confused with Vairocana Mahabali, son of Virochana. Vairocana Mahabali attained to sahaja nirvikalpa samadhi in Yoga Vasishta.

Rocana Buddha is the "enjoyment body" or "Sambhogakaya body" of the tri-kaya of Buddha, while Vairocana Buddha is the "Dharmakaya body". And Shakyamuni Buddha is the "Nirmanakaya body" or physical body.

Literary and historical development

Vairocana Buddha is first introduced in the Brahmajala Sutra:

Now, I, Vairocana Buddha am sitting atop a lotus pedestal; On a thousand flowers surrounding me are a thousand Sakyamuni Buddhas. Each flower supports a hundred million worlds; in each world a Sakyamuni Buddha appears. All are seated beneath a Bodhi-tree, all simultaneously attain Buddhahood. All these innumerable Buddhas have Vairocana as their original body.[4]

Vairocana is also mentioned in the Avatamsaka Sutra; however, the doctrine of Vairocana is based largely on the teachings of the Mahavairocana Tantra (also known as the Mahāvairocana-abhisaṃbodhi-tantra) and to a lesser degree the Vajrasekhara Sutra (also known as the Sarvatathāgatatattvasaṃgraha Tantra).

In the Avatamsaka Sutra, Vairocana is described as having attained enlightenment immeasurable ages ago and residing in a world purified by him while he was a bodhisattva. He also presides over an assembly of countless other bodhisattvas. He may be considered the celestial existence (saṃbhogakāya) of Gautama Buddha, who came to be as Vairochana's earthly rebirth from his previous existence in Tushita heaven.[5] Similarly, the Brahmajala Sutra also states that Shakyamuni was originally named Vairochana, regarding the former as a physical incarnation (nirmāṇakāya) of the latter.[5]

Vairocana is also mentioned as an epithet of Gautama Buddha in the Samantabhadra Meditation Sutra, who dwells in a place called "Always Tranquil Light".[6] In the Śūraṅgama mantra (Chinese: 楞嚴咒; pinyin: Léngyán Zhòu) taught in the Śūraṅgama sutra (Chinese: 楞嚴經; pinyin: Léngyán Jīng), an especially influential dharani in the Chinese Chan tradition, Vairocana is mentioned to be the host of the Buddha Division in the centre, one of the five major divisions which dispels the vast demon armies of the five directions.[7]

Vairocana is the Primordial Buddha in the Chinese schools of Tiantai, Huayan and Tangmi, also appearing in later schools including the Japanese Kegon, Shingon and esoteric lineages of Tendai. In the case of Huayan and Shingon, Vairocana is the central figure.

In Chinese and Japanese Buddhism, Vairocana was gradually superseded as an object of reverence by Amitābha, due in large part to the increasing popularity of Pure Land Buddhism, but veneration of Vairocana still remains popular among adherents.

During the initial stages of his mission in Japan, the Catholic missionary Francis Xavier was welcomed by the Shingon monks since he used Dainichi, the Japanese name for Vairocana, to designate the Christian God. As Xavier learned more about the religious nuances of the word, he substituted the term Deusu, which he derived from the Latin and Portuguese Deus.[8][9]

The Shingon monk Dohan regarded the two great Buddhas, Amitābha and Vairocana, as one and the same Dharmakāya Buddha and as the true nature at the core of all beings and phenomena. There are several realizations that can accrue to the Shingon practitioner of which Dohan speaks in this connection, as James Sanford points out:

[T]here is the realization that Amida is the Dharmakaya Buddha, Vairocana; then there is the realization that Amida as Vairocana is eternally manifest within this universe of time and space; and finally there is the innermost realization that Amida is the true nature, material and spiritual, of all beings, that he is 'the omnivalent wisdom-body, that he is the unborn, unmanifest, unchanging reality that rests quietly at the core of all phenomena".[10]

Helen Hardacre, writing on the Mahavairocana Tantra, comments that Mahavairocana's virtues are deemed to be immanently universal within all beings: "The principle doctrine of the Dainichikyo is that all the virtues of Dainichi (Mahāvairocana) are inherent in us and in all sentient beings."[11]

Mantras and Dharanis

Numerous mantras, seed syllables and dharanis are associated with Vairocana Buddha.

A common basic mantra is the following:[12]

oṃ vairocana hūṃ

The five elements mantra or five syllables mantra (Japanese: goji shingon) symbolizes how all things in the universe are emanations of Vairocana (symbolized here by the letter A which is associated with the fifth element - consciousness):[13]

a vi ra hūṃ khaṃ

The Mantra of Light, popular in Shingon, is:

oṃ amogha vairocana mahāmudra maṇipadma jvāla pravarttaya hūṃ

The Sarvadurgatiparishodana dharani (Complete removal of all unfortunate rebirths), also known as Kunrig mantra in Tibetan Buddhism. This dharani is found in the Sarvadurgatiparishodana tantra which depicts Vairocana at the center of a mandala surrounded by the other four tathagatas.[14] The dharani is as follows:[15][16]

OṂ NAMO BHAGAVATE SARVA DURGATI PARIŚODHANA RĀJĀYA TATHĀGATĀYA ARHATE SAMYAKSAṂBUDDHAYA TADYATHĀ OṂ ŚODHANE ŚODHANE SARVA PĀPAṂ VIŚODHANE ŚUDDHE VIŚUDDHE SARVA KARMA AVARAṆA VIŚUDDHE SVĀHĀ

Statues

With regard to śūnyatā, the massive size and brilliance of Vairocana statues serve as a reminder that all conditioned existence is empty and without a permanent identity, whereas the Dharmakāya is beyond concepts.

The Spring Temple Buddha of Lushan County, Henan, China, with a height of 126 meters, is the second tallest statue in the world (see list of tallest statues).

The Daibutsu in the Tōdai-ji in Nara, Japan, is the largest bronze image of Vairocana in the world.

The larger of the Buddhas of Bamiyan in Afghanistan that were destroyed was also a depiction of Vairocana.

In Java, Indonesia, the ninth-century Mendut temple near Borobudur in Magelang was dedicated to the Dhyani Buddha Vairocana. Built by the Shailendra dynasty, the temple featured a three-meter tall stone statue of Vairocana, seated and performing the dharmachakra mudrā. The statue is flanked with statues of the bodhisattvas Avalokiteśvara and Vajrapani.

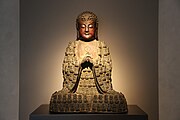

Gallery

-

Tang dynasty statue of Vairocana (Dàrì Rúlái) at Longmen Grottoes, Luoyang, Henan, China. The statue was completed in the year 676 and is 17.14 m high and has 2 m long ears.

-

Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279 CE) cliff carving of Vairocana (centre), with Manjushri (left), and Samantabhadra (right) among the Dazu Rock Carvings at Mount Baoding, Dazu District, Chongqing, China.

-

Ming dynasty statues of Vairocana (center), flanked on the far left by Amitabha and on the right by Bhaisajyaguru. Projecting tongues from Vairocana's throne are petals that symbolize his radiance in infinite directions.

-

Ming dynasty (1368–1644) statue of Vairocana in Huayan Temple in Datong, Shanxi, China, one out of a set of statues of the Five Tathāgatas.

-

Jin Dynasty (1115–1234) statue of Vairocana in Shanhua Temple in Datong, Shanxi, China, one out of a set of statues of the Five Tathāgatas.

-

Tang dynasty bronze statue of Vairocana. 8th century.

-

Copper alloy statue of Vairocana, made in China during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Displayed at the Cantor Center for Visual Arts.

-

Ming dynasty bronze statue of Vairocana. Displayed at the Buddhism Sculpture Gallery in Aurora Museum, Pudong, Shanghai.

-

Statue of Vairocana, made in China during the Qing dynasty. 19th century. Made of jade, gilt bronze, enamel, pearls and kingfisher feathers. Displayed at the Royal Ontario Museum.

-

Vairocana statue in Sam Poh Wan Futt Chi, a Chinese Buddhist temple in Cameron Highlands, Pahang, Malaysia.

-

Shrine to Vairocana in Zhusheng Temple, Hunan, China.

-

Seated iron statue of Vairocana in Borimsa Temple, on Gaji mountain in Jangheung County, South Jeolla, South Korea.

-

A gilt-bronze statue of Vairocana Buddha, one of the National Treasures of South Korea, at Bulguksa.

-

Multi-headed Sarvavid Vairochana, Central Tibet, circa late 13th – early 14th century.

-

Vairocana statue in Northern Vietnam, 19th century AD, Nguyễn dynasty.

See also

Sources

- ^ 佛光大辭典增訂版隨身碟,中英佛學辭典 - "三身" (Fo Guang Great Dictionary Updated USB Version, Chinese-English Dictionary of Buddhist Studies - "Trikāya" entry)

- ^ "Birushana Buddha. SOTOZEN-NET Glossary". Retrieved 2015-09-12.

- ^ Buswell, Robert Jr; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2013). Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 949–950. ISBN 9780691157863.

- ^ "YMBA's translation of Brahma Net Sutra". Archived from the original on March 5, 2005. Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- ^ a b Xing, Guan (2005). The Concept of the Buddha: Its Evolution from Early Buddhism to the Trikāya Theory. Psychology Press. p. 169-171. ISBN 978-0-41533-344-3.

- ^ Reeves 2008, pp. 416, 452

- ^ The Śūraṅgama sūtra : a new translation. Hsüan Hua, Buddhist Text Translation Society. Ukiah, Calif.: Buddhist Text Translation Society. 2009. ISBN 978-0-88139-962-2. OCLC 300721049.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Francis Xavier and the Land of the Rising Sun: Dainichi and Deus, Matthew Ropp, 1997.

- ^ Elisonas, Jurgis (1991). "7 - Christianity and the daimyo". In Hall, John Whitney; McClain, James L. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Japan. Vol. 4. Cambridge Eng. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 307. ISBN 9780521223553.

- ^ James H. Sanford, 'Breath of Life: The Esoteric Nembutsu' in Tantric Buddhism in East Asia, ed. by Richard K. Payne, Wisdom Publications, Boston, 2006, p. 176

- ^ Helen Hardacre, 'The Cave and the Womb World', in Tantric Buddhism in East Asia (Wisdom Publications, Boston, 2006), p. 215

- ^ "Vairocana-Mahāvairocana mantras and seed syllables". www.visiblemantra.org. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ Stone, Jacqueline I. (2016). Right Thoughts at the Last Moment: Buddhism and Deathbed Practices in Early Medieval Japan, p. 499. University of Hawaii Press.

- ^ Huntington, John C.; Bangdel, Dina. The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art, p. 106. Serindia Publications, Inc., 2003.

- ^ FPMT, 2021. Ten Powerful Mantras for the Time of Death.

- ^ Baruah, Bibhuti (2000) Buddhist Sects and Sectarianism, pp. 205-206. Sarup & Sons.

Bibliography

- Birmingham, Vessantara (2003). Meeting The Buddhas, Windhorse Publications, ISBN 0-904766-53-5.

- Cook, Francis H. (1977). Hua-Yen Buddhism: The Jewel Net of Indra, Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Cook, Francis H. (1972). 'The meaning of Vairocana in Hua-Yen Buddhism, Philosophy East and West 22 (4), 403-415

- Park, Kwangsoo (2003). A Comparative Study of the Concept of Dharmakaya Buddha: Vairocana in Hua-yen and Mahavairocana in Shingon Buddhism, International Journal of Buddhist Thought and Culture 2, 305-331

- Reeves, Gene (2008). The Lotus Sutra: A Contemporary Translation of a Buddhist Classic. Somerville: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0-86171-571-8.

External links

- Sacred Visions: Early Paintings from Central Tibet, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Vairocana (see index)