I, Libertine: Difference between revisions

Don Columbia (talk | contribs) →Creation: Per the cited reference, there is no evidence that it appeared on the NYT list. Indeed, I looked; it didn't. |

Don Columbia (talk | contribs) →Creation: Per cited reference, there is no evidence of it actually appearing on the NYT lists in 1956. Indeed, it isn't; I looked. |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

== Creation == |

== Creation == |

||

Shepherd was annoyed at the way [[bestseller]] lists were compiled in the mid-1950s. These lists were determined from sales figures and from the number of requests for new and upcoming books at bookstores. Shepherd urged his listeners to enter bookstores and ask for a non-existent book. He fabricated the author (Frederick R. Ewing) of this imaginary novel, concocted a title (''I, Libertine''), and outlined a basic plot for his listeners to use on bookstore clerks. Fans of the show took it further, planting references to the book and author so widely that demand for the book led to claims of its inclusion on [[The New York Times Best Seller list|''The New York Times'' Best Seller list]].<ref>{{Cite web |date=September 26, 2017 |title=8 Notable Attempts to Hack the New York Times Bestseller List |url=https://lithub.com/8-notable-attempts-to-hack-the-new-york-times-bestseller-list/ |access-date=March 2, 2022 |first=Emily|last=Temple|website=[[Literary Hub]] |language=en-US}}</ref> |

Shepherd was annoyed at the way [[bestseller]] lists were compiled in the mid-1950s. These lists were determined from sales figures and from the number of requests for new and upcoming books at bookstores. Shepherd urged his listeners to enter bookstores and ask for a non-existent book. He fabricated the author (Frederick R. Ewing) of this imaginary novel, concocted a title (''I, Libertine''), and outlined a basic plot for his listeners to use on bookstore clerks. Fans of the show took it further, planting references to the book and author so widely that demand for the book led to claims of its inclusion on [[The New York Times Best Seller list|''The New York Times'' Best Seller list]].<ref>{{Cite web |date=September 26, 2017 |title=8 Notable Attempts to Hack the New York Times Bestseller List |url=https://lithub.com/8-notable-attempts-to-hack-the-new-york-times-bestseller-list/ |access-date=March 2, 2022 |first=Emily|last=Temple|website=[[Literary Hub]] |language=en-US}} "[T]here’s no evidence that this is true."</ref> |

||

== Publication == |

== Publication == |

||

Revision as of 01:46, 7 February 2024

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2015) |

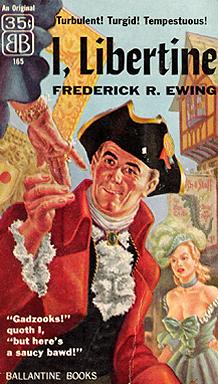

Cover of first edition (paperback) | |

| Author | Frederick R. Ewing (Theodore Sturgeon) |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Frank Kelly Freas |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Historical fiction |

| Publisher | Ballantine Books |

Publication date | 1956 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardcover & paperback) |

| Pages | 151 |

I, Libertine is a historical novel that began as a practical joke by late-night radio raconteur Jean Shepherd who aimed to lampoon the process of determining best-selling books. After generating substantial attention for a novel that did not actually exist, Shepherd approved a 1956 edition of the book written mainly by Theodore Sturgeon—which became an actual best-seller, with all profits donated to charity.

Creation

Shepherd was annoyed at the way bestseller lists were compiled in the mid-1950s. These lists were determined from sales figures and from the number of requests for new and upcoming books at bookstores. Shepherd urged his listeners to enter bookstores and ask for a non-existent book. He fabricated the author (Frederick R. Ewing) of this imaginary novel, concocted a title (I, Libertine), and outlined a basic plot for his listeners to use on bookstore clerks. Fans of the show took it further, planting references to the book and author so widely that demand for the book led to claims of its inclusion on The New York Times Best Seller list.[1]

Publication

Bookstores became interested in carrying Ewing's novel, which allegedly had been banned in Boston. When publisher Ian Ballantine, novelist Theodore Sturgeon, and Shepherd met for lunch, Ballantine hired Sturgeon to write a novel based on Shepherd's outline. Betty Ballantine completed the final chapter after Sturgeon fell asleep, exhausted, on the Ballantines' couch, having tried to meet the deadline in one marathon typing session.

On September 13, 1956, Ballantine Books published I, Libertine simultaneously in hardcover and paperback editions with Shepherd pictured as Ewing, looking as dissolute as possible, on the back cover author's photograph. The proceeds from book sales were donated to charity.[2] A few weeks before publication, The Wall Street Journal officially "exposed" the hoax, already an open secret.[3]

Plot

I, Libertine tells the story of a social climber who styles himself as Lance Courtenay. Most of the plot is closely based on the life of Elizabeth Chudleigh. An afterword states that "The story of Elizabeth Chudleigh is substantially true ...", which could easily be taken as being part of the hoax, ironically.[4]

Cover painting

The front cover displays a quote: "'Gadzooks,' quoth I, 'but here's a saucy bawd!'". The cover painting by Frank Kelly Freas includes hidden images and inside jokes: The sign on the tavern, Fish & Staff, has a shepherd's staff and an image of a sturgeon, referencing both Sturgeon and Shepherd. A portion of the word often spoken on the air by Shepherd – "Excelsior!" – can be seen on the paperback cover in a triangular area at extreme left, where it is part of the decoration on the coach door. The entire word is visible on the hardcover dust jacket, which features more of the illustration.

See also

- Atlanta Nights – another hoax book created in an attempt to manipulate the publishing process.

- J. R. Hartley – author of another fictitious book, written after it became famous.

References

- ^ Temple, Emily (September 26, 2017). "8 Notable Attempts to Hack the New York Times Bestseller List". Literary Hub. Retrieved March 2, 2022. "[T]here’s no evidence that this is true."

- ^ An interview with Shepherd on the hoax from Long John Nebel's radio show, WFMU's Beware of the Blog, June 25, 2008. Archived August 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Henderson, Carter (August 1, 1956). "Ballantine Books Makes Hoax Come True". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on April 27, 2002. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ T. H. White, The Age of Scandal, Faber & Faber, 2011, ISBN 978-0571274765.

External links

- Cover with link to documents

- "I, Libertine". flicklives.com. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011.

- History and back cover scan

- "I, Libertine". flicklives.com. Archived from the original (audiobook) on 2006-06-13. Retrieved 2006-09-04.

- Powell, J. Mark (April 25, 2015). "The Bestseller Book That Didn't Exist: how the Author of a Beloved Christmas Classic Pulled Off the Hoax of the Century". Retrieved August 3, 2015.