Perrin number: Difference between revisions

Supplement: signature |

Signature: recent discoveries |

||

| Line 183: | Line 183: | ||

ENDFOR |

ENDFOR |

||

Show the |

Show the result |

||

PRINT v(2), v(1), v(0) |

PRINT v(2), v(1), v(0) |

||

PRINT u(0), u(1), u(2) |

PRINT u(0), u(1), u(2) |

||

| Line 191: | Line 191: | ||

If {{math|P(−n) {{=}} −1}} and {{math|P(n) {{=}} 0}} then ''n'' is a [[probable prime]], that is: actually prime or a strong Perrin pseudoprime. |

If {{math|P(−n) {{=}} −1}} and {{math|P(n) {{=}} 0}} then ''n'' is a [[probable prime]], that is: actually prime or a strong Perrin pseudoprime. |

||

Shanks ''et al.'' |

Shanks ''et al.'' observed that for all strong pseudoprimes they found, the final state of the above six registers (the "signature" of ''n'') equals the initial state 1,−1,3, 3,0,2.<ref>{{harvtxt|Adams|Shanks|1982|p=275}}, {{harvtxt|Kurtz|Shanks|Williams|1986|p=694}}. This was later confirmed for {{math|n < 10{{sup|14}}}} by Steven {{harvtxt|Arno|1991}}.</ref> Unfortunately, the same is true for {{math|≈ 1'''/'''6}} of all primes, so the two sets cannot be distinguished on the strength of this test alone.<ref>The signature does give discriminating information for the remaining two types of primes. Corresponding pseudoprimes, which are extremely sparse, have only recently been discovered. {{harvtxt|Stephan|2019}}</ref> In that case, they suggested to also use the [[Supergolden_ratio#Narayana sequence|Narayana-Lucas sister sequence]] with recurrence relation {{math|A(n) {{=}} A(n − 1) + A(n − 3)}} and initial values |

||

In that case, for higher confidence, one could also use the [[Supergolden_ratio#Narayana sequence|Narayana-Lucas sister sequence]] with recurrence relation {{math|A(n) {{=}} A(n − 1) + A(n − 3)}} and initial values |

|||

u(0):= 3, u(1):= 1, u(2):= 1 |

u(0):= 3, u(1):= 1, u(2):= 1 |

||

| Line 333: | Line 331: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

*{{cite arXiv |

*{{cite arXiv |

||

| last = Stephan |

| last = Stephan | first = Holger |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| title = Millions of Perrin pseudoprimes including a few giants |

| title = Millions of Perrin pseudoprimes including a few giants |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| eprint = 2002.03756v1 |

| eprint = 2002.03756v1 |

||

}} |

|||

*{{citation |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| title = Perrin pseudoprimes. Data sets |

|||

| publisher = [[Weierstrass Institute]] |

|||

| location = Berlin |

|||

| date = 2019 |

|||

| doi = 10.20347/WIAS.DATA.4 |

|||

| doi-access = free |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

Revision as of 17:19, 26 February 2024

In mathematics, the Perrin numbers are a doubly infinite constant-recursive integer sequence with characteristic equation x3 = x + 1. The Perrin numbers bear the same relationship to the Padovan sequence as the Lucas numbers do to the Fibonacci sequence.

Definition

The Perrin numbers are defined by the recurrence relation

and the reverse

The first few terms in both directions are

| n | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

| P(n) | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 12 | 17 | 22 | 29 | 39 | 51 | 68 | 90 | 119 | ...[1] |

| P(-n) | ... | -1 | 1 | 2 | -3 | 4 | -2 | -1 | 5 | -7 | 6 | -1 | -6 | 12 | -13 | 7 | 5 | -18 | ...[2] |

Perrin numbers can be expressed as sums of the three initial terms

The first fourteen prime Perrin numbers are

| n | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 12 | 20 | 21 | 24 | 34 | 38 | 75 | ...[3] |

| P(n) | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 17 | 29 | 277 | 367 | 853 | 14197 | 43721 | 1442968193 | ...[4] |

History

In 1876 the sequence and its equation were initially mentioned by Édouard Lucas, who noted that the index n divides term P(n) if n is prime.[5] In 1899 Raoul Perrin asked if there were any counterexamples to this property.[6] The first P(n) divisible by composite index n was found only in 1982 by William Adams and Daniel Shanks.[7] They presented a detailed investigation of the sequence, with a sequel appearing four years later.[8]

Properties

The Perrin sequence also satisfies the recurrence relation Starting from this and the defining recurrence, one can create an infinite number of further relations, for example

The generating function of the Perrin sequence is

The sequence is related to sums of binomial coefficients by

- .[9]

Perrin numbers can be expressed in terms of partial sums

The Perrin numbers are obtained as integral powers n ≥ 0 of the matrix

and its inverse

The Perrin analogue of the Simson identity for Fibonacci numbers is given by the determinant

The number of different maximal independent sets in an n-vertex cycle graph is counted by the nth Perrin number for n > 2.[10]

Binet formula

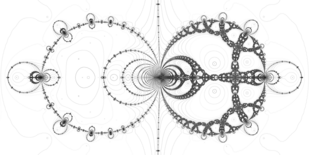

The solution of the recurrence can be written in terms of the roots of characteristic equation . If the three solutions are real root p (with approximate value 1.324718 and known as the plastic ratio) and complex conjugate roots q and r, the Perrin numbers can be computed with the Binet formula which also holds for negative n.

The polar form is with Since the formula reduces to either the first or the second term successively for large positive or negative n, and numbers with negative subscripts oscillate. Provided p is computed to sufficient precision, these formulas can be used to calculate Perrin numbers for large n.

Expanding the identity gives the important index-doubling rule by which the forward and reverse parts of the sequence are linked.

Perrin primality test

Query 1484. The curious proposition of Chinese origin which is the subject of query 1401[11] would provide, if it is true, a more practical criterium than Wilson's theorem for verifying whether a given number m is prime or not; it would suffice to calculate the residues with respect to m of successive terms of the recurrence sequence

un = 3un−1 − 2un−2 with initial values u0 = −1, u1 = 0.[12]

I have found another recurrence sequence that seems to possess the same property; it is the one whose general term is

vn = vn−2 + vn−3 with initial values v0 = 3, v1 = 0, v2 = 2. It is easy to demonstrate that vn is divisible by n, if n is prime; I have verified, up to fairly high values of n, that in the opposite case it is not; but it would be interesting to know if this is really so, especially since the sequence vn gives much less rapidly increasing numbers than the sequence un (for n = 17, for example, one finds un = 131070, vn = 119), which leads to simpler calculations when n is a large number.

The same proof, applicable to one of the sequences, will undoubtedly bear upon the other, if the stated property is true for both: it is only a matter of discovering it.[13]

The Perrin sequence has the Fermat property: if p is prime, P(p) ≡ P(1) ≡ 0 (mod p). However, the converse is not true: some composite n may still divide P(n). A number with this property is called a Perrin pseudoprime.

The question of the existence of Perrin pseudoprimes was considered by Malo and Jarden,[14] but none were known until Adams and Shanks found the smallest one, 271441 = 5212 (the number P(271441) has 33150 decimal digits).[15] Jon Grantham later proved that there are infinitely many Perrin pseudoprimes.[16]

The seventeen Perrin pseudoprimes below 109 are

- 271441, 904631, 16532714, 24658561, 27422714, 27664033, 46672291, 102690901, 130944133, 196075949, 214038533, 517697641, 545670533, 801123451, 855073301, 903136901, 970355431.[17]

Adams and Shanks noted that primes also satisfy the congruence P(−p) ≡ P(−1) ≡ −1 (mod p). Composites for which both properties hold are called restricted Perrin pseudoprimes. There are only nine such numbers below 109.[18]

While Perrin pseudoprimes are rare, they overlap with Fermat pseudoprimes. Of the above seventeen numbers, four are also base 2 Fermatians. In contrast, the Lucas pseudoprimes are anti-correlated. Presumably, combining the Perrin and Lucas tests would make a primality test as strong as the reliable BPSW test which has no known pseudoprimes – though at higher computational cost.

Pseudocode

The 1982 Adams and Shanks O(log n) Strong Perrin primality test.[19]

Two integer arrays u(3) and v(3) are initialized to the lowest terms of the Perrin sequence, with positive indices t = 0, 1, 2 in u( ) and negative indices t = 0,−1,−2 in v( ).

The main double-and-add loop, originally devised to run on an HP-41C pocket calculator, efficiently computes P(n) mod n and the reverse P(−n) mod n.

The subscripts of the Perrin numbers are doubled using the identity P(2t) = P2(t) − 2P(−t). The resulting gaps between P(±2t) and P(±2t ± 2) are closed by applying the defining relation P(t) = P(t − 2) + P(t − 3).

Initial values LET u(0):= 3, u(1):= 0, u(2):= 2 LET v(0):= 3, v(1):=−1, v(2):= 1 INPUT integer n, the odd positive number to test SET integer h:= most significant bit of n FOR k:= h − 1 DOWNTO 0 Double the indices of the six Perrin numbers. FOR i = 0, 1, 2 temp:= u(i)^2 − 2v(i) (mod n) v(i):= v(i)^2 − 2u(i) (mod n) u(i):= temp ENDFOR Copy P(2t + 2) and P(−2t − 2) to the array ends and use in the IF statement below. u(3):= u(2) v(3):= v(2) Overwrite P(2t ± 2) with P(2t ± 1) temp:= u(2) − u(1) u(2):= u(0) + temp u(0):= temp Overwrite P(−2t ± 2) with P(−2t ± 1) temp:= v(0) − v(1) v(0):= v(2) + temp v(2):= temp IF n has bit k set THEN Increase the indices of both Perrin triples by 1. FOR i = 0, 1, 2 u(i):= u(i + 1) v(i):= v(i + 1) ENDFOR ENDIF ENDFOR Show the result PRINT v(2), v(1), v(0) PRINT u(0), u(1), u(2)

Successively P(−n − 1), P(−n), P(−n + 1) and P(n − 1), P(n), P(n + 1) (mod n).

If P(−n) = −1 and P(n) = 0 then n is a probable prime, that is: actually prime or a strong Perrin pseudoprime.

Shanks et al. observed that for all strong pseudoprimes they found, the final state of the above six registers (the "signature" of n) equals the initial state 1,−1,3, 3,0,2.[20] Unfortunately, the same is true for ≈ 1/6 of all primes, so the two sets cannot be distinguished on the strength of this test alone.[21] In that case, they suggested to also use the Narayana-Lucas sister sequence with recurrence relation A(n) = A(n − 1) + A(n − 3) and initial values

u(0):= 3, u(1):= 1, u(2):= 1 v(0):= 3, v(1):= 0, v(2):=−2

The same doubling rule applies and the formulas for filling the gaps are

temp:= u(0) + u(1)

u(0):= u(2) − temp

u(2):= temp

temp:= v(2) + v(1)

v(2):= v(0) − temp

v(0):= temp

Here, n is a probable prime if A(−n) = 0 and A(n) = 1.

Kurtz et al. found no overlap between the odd pseudoprimes for the two sequences below 50∙109 and supposed that 2277740968903 = 1067179 ∙ 2134357 is the smallest composite number to pass both tests.[22]

Notes

- ^ Sloane, N. J. A. (ed.). "Sequence A001608". The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. OEIS Foundation.

- ^ (sequence A078712 in the OEIS)

- ^ (sequence A112881 in the OEIS)

- ^ (sequence A074788 in the OEIS)

- ^ Lucas (1878)

- ^ Perrin (1899)

- ^ Adams & Shanks (1982)

- ^ Kurtz, Shanks & Williams (1986)

- ^ (sequence A001608 in the OEIS)

- ^ Füredi (1987)

- ^ Tarry (1898)

- ^ equivalently un = 2n − 2. (sequence A000918 in the OEIS)

- ^ Perrin (1899) translated from the French

- ^ Malo (1900), Jarden (1966)

- ^ Adams & Shanks (1982, p. 255)

- ^ Grantham (2010), Stephan (2020)

- ^ (sequence A013998 in the OEIS)

- ^ (sequence A018187 in the OEIS), (sequence A275612 in the OEIS), (sequence A275613 in the OEIS)

- ^ Adams & Shanks (1982, p. 265, 269-270)

- ^ Adams & Shanks (1982, p. 275), Kurtz, Shanks & Williams (1986, p. 694). This was later confirmed for n < 1014 by Steven Arno (1991).

- ^ The signature does give discriminating information for the remaining two types of primes. Corresponding pseudoprimes, which are extremely sparse, have only recently been discovered. Stephan (2019)

- ^ Kurtz, Shanks & Williams (1986, p. 697)

References

- Lucas, E. (1878). "Théorie des fonctions numériques simplement périodiques". American Journal of Mathematics (in French). 1 (3). Johns Hopkins University Press: 229−231. doi:10.2307/2369311. JSTOR 2369311.

- Tarry, G. (1898). "Question 1401". L'Intermédiaire des Mathématiciens. 5. Gauthier-Villars et fils: 266−267.

- Perrin, R. [in French] (1899). "Question 1484". L'Intermédiaire des Mathématiciens. 6. Gauthier-Villars et fils: 76−77.

- Malo, E. (1900). "Réponse à 1484". L'Intermédiaire des Mathématiciens. 7. Gauthier-Villars et fils: 280−282, 312−314.

- Jarden, Dov (1966). Recurring sequences (PDF) (2 ed.). Jerusalem: Riveon LeMatematika. pp. 86−93.

- Adams, William; Shanks, Daniel (1982). "Strong primality tests that are not sufficient". Mathematics of Computation. 39 (159). American Mathematical Society: 255−300. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1982-0658231-9. JSTOR 2007637.

- Kurtz, G.C.; Shanks, Daniel; Williams, H.C. (1986). "Fast primality tests for numbers less than 50∙109". Mathematics of Computation. 46 (174). American Mathematical Society: 691−701. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1986-0829639-7. JSTOR 2008007.

- Füredi, Zoltán (1987). "The number of maximal independent sets in connected graphs". Journal of Graph Theory. 11 (4): 463−470. doi:10.1002/jgt.3190110403.

- Arno, Steven (1991). "A note on Perrin pseudoprimes". Mathematics of Computation. 56 (193). American Mathematical Society: 371−376. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1991-1052083-9. JSTOR 2008548.

- Grantham, Jon (2010). "There are infinitely many Perrin pseudoprimes". Journal of Number Theory. 130 (5): 1117−1128. arXiv:1903.06825. doi:10.1016/j.jnt.2009.11.008.

- Stephan, Holger (2020). "Millions of Perrin pseudoprimes including a few giants". arXiv:2002.03756v1.

- Stephan, Holger (2019), Perrin pseudoprimes. Data sets, Berlin: Weierstrass Institute, doi:10.20347/WIAS.DATA.4