Draft:History of Varanasi: Difference between revisions

Loveforwiki (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: harv-error Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Loveforwiki (talk | contribs) Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

[[Narendra Modi]], prime minister of India since 2014, has represented [[Varanasi (Lok Sabha constituency)|Varanasi]] in the [[Parliament of India]] since [[2014 Indian general election|2014]]. Modi inaugurated the Shri Kashi Vishwanath Corridor project, which aimed to enhance the city's spiritual vibrancy by connecting many ghats to the temple of Kashi Vishwanath, in December 2021.<ref>{{Cite news|date=13 December 2021|title=Kashi Vishwanath Corridor {{!}} A Look At Varanasi's Transformation Under PM Modi|language=en-GB|work=outlook india|url=https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/india-news-kashi-vishwanath-corridor-a-look-at-varanasis-transformation-under-pm-mod |

[[Narendra Modi]], prime minister of India since 2014, has represented [[Varanasi (Lok Sabha constituency)|Varanasi]] in the [[Parliament of India]] since [[2014 Indian general election|2014]]. Modi inaugurated the Shri Kashi Vishwanath Corridor project, which aimed to enhance the city's spiritual vibrancy by connecting many ghats to the temple of Kashi Vishwanath, in December 2021.<ref>{{Cite news|date=13 December 2021|title=Kashi Vishwanath Corridor {{!}} A Look At Varanasi's Transformation Under PM Modi|language=en-GB|work=outlook india|url=https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/india-news-kashi-vishwanath-corridor-a-look-at-varanasis-transformation-under-pm-mod |

||

==References== |

|||

{{reference}} |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

Revision as of 11:52, 6 July 2024

Mythology

According to Hindu mythology, Varanasi was founded by Shiva,[1] one of three principal deities along with Brahma and Vishnu. During a conflict between Brahma and Shiva, one of Brahma's five heads was torn off by Shiva. As was the custom, the victor carried the slain adversary's head in his hand and let it hang down from his hand as an act of ignominy, and a sign of his own bravery. A bridle was also put into the mouth. Shiva thus dishonoured Brahma's head, and kept it with him at all times. When he came to the city of Varanasi in this state, the hanging head of Brahma dropped from Shiva's hand and disappeared in the ground. Varanasi is therefore considered an extremely holy site.[2]

The Pandavas, the protagonists of the Hindu epic Mahabharata, are said to have visited the city in search of Shiva to atone for their sins of fratricide and brahmahatya that they had committed during the Kurukshetra War.[3] It is regarded as one of seven holy cities (Sapta Puri) which can provide Moksha; Ayodhya, Mathura, Haridwar, Kashi, Kanchi, Avanti, and Dvārakā are the seven cities known as the givers of liberation.[4] The princesses Ambika and Ambalika of Kashi were wed to the Hastinapura ruler Vichitravirya, and they later gave birth to Pandu and Dhritarashtra. Bhima, a son of Pandu, married a Kashi princess Valandhara and their union resulted in the birth of Sarvaga, who later ruled Kashi. Dhritarasthra's eldest son Duryodhana also married a Kashi princess Bhanumati, who later bore him a son Lakshmana Kumara and a daughter Lakshmanā.[5]

The Cakkavatti Sīhanāda Sutta text of Buddhism puts forth an idea stating that Varanasi will one day become the fabled kingdom of Ketumati in the time of Maitreya.[6]

Ancient period

Excavations in 2014 led to the discovery of artefacts dating back to 800 BCE. Further excavations at Aktha and Ramnagar, two sites in the vicinity of the city, unearthed artefacts dating back to 1800 BCE, supporting the view that the area was inhabited by this time.[7]

During the time of Gautama Buddha, Varanasi was part of the Kingdom of Kashi.[8] The celebrated Chinese traveller Xuanzang, also known as Hiuen Tsiang, who visited the city around 635 CE, attested that the city was a centre of religious and artistic activities, and that it extended for about 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) along the western bank of the Ganges.[8][9] When Xuanzang visited Varanasi in the 7th century, he named it "Polonise" (婆羅痆斯) and wrote that the city had some 30 temples with about 30 monks.[10] The city's religious importance continued to grow in the 8th century, when Adi Shankara established the worship of Shiva as an official sect of Varanasi.[11]

Medieval period

Chandradeva, founder of the Gahadavala dynasty made Banaras a second capital in 1090.[12] In 1194 CE, the Ghurid conqueror Muizzuddin Muhammad Ghuri defeated the forces of Jayachandra in a battle near Jamuna and afterwards ravaged the city of Varnasi in the course of which many temples were destroyed.[13]

Varanasi remained a centre of activity for intellectuals and theologians during the Middle Ages, which further contributed to its reputation as a cultural centre of religion and education. Several major figures of the Bhakti movement were born in Varanasi, including Kabir who was born here in 1389,[14] and Ravidas, a 15th-century socio-religious reformer, mystic, poet, traveller, and spiritual figure, who was born and lived in the city and employed in the tannery industry.[15] [1]

Early Modern to Modern periods (1500–1949)

-

A lithograph by James Prinsep of a Brahmin placing a garland on the holiest location in the city

-

A painting by Lord Weeks (1883) of Varanasi, viewed from the Ganges

-

An illustration (1890) of a bathing ghat in Varanasi

Numerous eminent scholars and preachers visited the city from across India and South Asia. Guru Nanak visited Varanasi for Maha Shivaratri in 1507,Kashi(Varansi) p that played a large role in the founding of Sikhism.[16]

In 1567 or thereabouts, the Mughal emperor Jallaludin Muhammad Akbar sacked the city of Varanasi on his march from Allahabad (modern Prayagraj).[17] However, later the Kachwaha Rajput rulers of Amber (Mughal vassals themselves) most notably under Raja Man Singh rebuilt various temples and ghats in the city.[18]

The Raja of Jaipur established the Annapurna Mandir, and the 200-metre (660 ft) Akbari Bridge was also completed during this period.[19] The earliest tourists began arriving in the city during the 16th century.[20] In 1665, the French traveller Jean-Baptiste Tavernier described the architectural beauty of the Vindu Madhava temple on the side of the Ganges. The road infrastructure was also improved during this period. It was extended from Kolkata to Peshawar by Emperor Sher Shah Suri; later during the British Raj it came to be known as the famous Grand Trunk Road. In 1656, Emperor Aurangzeb ordered the destruction of many temples and the building of mosques, causing the city to experience a temporary setback.[9] However, after Aurangzeb's death, most of India was ruled by a confederacy of pro-Hindu kings. Much of modern Varanasi was built during this time, especially during the 18th century by the Maratha and Bhumihar Brahmin rulers.[21] The kings governing Varanasi continued to wield power and importance through much of the British Raj period, including the Maharaja of Benares, or simply called by the people of Benares as Kashi Naresh.[22][23]

The Kingdom of Benares was given official status by the Mughals in 1737, and the kingdom started in this way and continued as a dynasty-governed area until Indian independence in 1947, during the reign of Vibhuti Narayan Singh. In the 18th century, Muhammad Shah ordered the construction of an observatory on the Ganges, attached to Man Mandir Ghat, designed to discover imperfections in the calendar in order to revise existing astronomical tables. Tourism in the city began to flourish in the 18th century.[20] As the Mughal suzerainty weakened, the Benares zamindari estate became Banaras State, thus Balwant Singh of the Narayan dynasty regained control of the territories and declared himself Maharaja of Benares in 1740.[24] The strong clan organisation on which they rested, brought success to the lesser known Hindu princes.[25] There were as many as 100,000 men backing the power of the Benares rajas in what later became the districts of Benares, Gorakhpur and Azamgarh.[25] This proved a decisive advantage when the dynasty faced a rival and the nominal suzerain, the Nawab of Oudh, in the 1750s and the 1760s.[25]

An exhausting guerrilla war, waged by the Benares ruler against the Oudh camp, using his troops, forced the Nawab to withdraw his main force.[25] The region eventually ceded by the Nawab of Oudh to the Benares State, a subordinate of the East India Company, in 1775, who recognised Benares as a family dominion.[26][27] In 1791 under the rule of the British, resident Jonathan Duncan founded a Sanskrit College in Varanasi.[28] In 1867, the establishment of the Varanasi Municipal Board led to significant improvements in the city's infrastructure and basic amenities of health services, drinking water supply and sanitation.[29]

Rev. M. A. Sherring in his book The Sacred City of Hindus: An account of Benaras in ancient and modern times published in 1868 refers to a census conducted by James Prinsep and put the total number of temples in the city to be around 1000 during 1830s. He writes,[30]

The history of a country is sometimes epitomised in the history of one of its principal cities. The city of Benaras represents India religiously and intellectually, just as Paris represents the political Sentiments of France. There are few cities in the world of greater antiquity, and none that have so uninterruptedly maintained their ancient celebrity and distinction.

Author Mark Twain wrote in 1897 of Varanasi,[31]

Benares is older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend, and looks twice as old as all of them put together.

Benares became a princely state in 1911,[26] with Ramnagar as its capital, but with no jurisdiction over the city proper. The religious head, Kashi Naresh, has had his headquarters at the Ramnagar Fort since the 18th century, also a repository of the history of the kings of Varanasi, which is situated to the east of Varanasi, across the Ganges.[32] The Kashi Naresh is deeply revered by the local people and the chief cultural patron; some devout inhabitants consider him to be the incarnation of Shiva.[33]

Annie Besant founded the Central Hindu College, which later became a foundation for the creation of Banaras Hindu University in 1916. Besant founded the college because she wanted "to bring men of all religions together under the ideal of brotherhood in order to promote Indian cultural values and to remove ill-will among different sections of the Indian population."[34]

Varanasi was ceded to the Union of India in 1947, becoming part of Uttar Pradesh after Indian independence.[35] Vibhuti Narayan Singh incorporated his territories into the United Provinces in 1949.[36]

-

Maharaja of Benares, 1870s

-

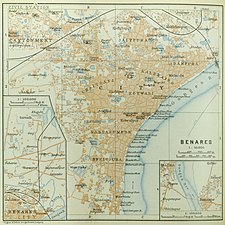

Map of the city, c. 1914

-

An 1895 photograph of the Varanasi riverfront

-

The lanes of Varanasi are bathed in a plethora of colours.

21st-century

Narendra Modi, prime minister of India since 2014, has represented Varanasi in the Parliament of India since 2014. Modi inaugurated the Shri Kashi Vishwanath Corridor project, which aimed to enhance the city's spiritual vibrancy by connecting many ghats to the temple of Kashi Vishwanath, in December 2021.<ref>{{Cite news|date=13 December 2021|title=Kashi Vishwanath Corridor | A Look At Varanasi's Transformation Under PM Modi|language=en-GB|work=outlook india|url=https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/india-news-kashi-vishwanath-corridor-a-look-at-varanasis-transformation-under-pm-mod

References

- ^ Melton 2007, p. 29.

- ^ Edward Sachau, 1910, Alberuni's India Archived 3 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine, p. 147, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd.

- ^ Bansal 2008, pp. 48–49.

- ^ "Garuḍa Purāṇa XVI 114". Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ "Kashi Varanasi - Sannidhi The Presence". 7 July 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Singh, Rana (2003). Where the Buddha Walked: A Companion to the Buddhist Places of India. Indica Books. p. 123. ISBN 9788186569368. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ "Banaras (Inde): new archaeological excavations are going on to determine the age of Varanasi". Archived from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ a b Pletcher 2010, pp. 159–160.

- ^ a b Berwick 1986, p. 121.

- ^ Eck 1982, p. 57.

- ^ Bindloss, Brown & Elliott 2007, p. 278.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 32–3. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- ^ Satish Chandra (2007). Medieval India:800-1700. Orient Longman. p. 71. ISBN 978-81-250-3226-7. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

In 1194, Muizzuddin returned to India. He crossed the Jamuna with 50,000 cavalry and moved towards Kanauj. A hotly contested battle between Muizzuddin and Jaichandra was fought at Chandawar near Kanauj. We are told that Jaichandra had almost carried the day when he was killed by an arrow, and his army was totally defeated. Muizzuddin now moved on to Banaras which was ravaged, a large number of temples there being destroyed

- ^ Das 1991, p. 17.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 1999, p. 910.

- ^ Gandhi 2007, p. 90.

- ^ S. Roy (1974). "AKBAR". In R. C. Majumdar (ed.). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Mughal empire. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. pp. 119–120. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

Akbar then marched to Allahabad and onto Banaras which was sacked because it closes its gates against him

- ^ Rima Hooja (2006). A history of Rajasthan. Rupa & Company. pp. 493–495. ISBN 978-8129108906. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

Among the architectural legacies left by Man Singh are the palaces within Amber fort, Man Mandir, Man Chat and Sarovar Ghat at Varanasi, the Govind Dev temple at Vrindaban, and temples at Pushkar, Manpur, Puri, etc. He also built forts at Salimpur (Bengal), Manihari (Bihar), Ramgarh (Dhoondhar), founded the towns of Akbarnagar (Rajmahal), Manpur (near Gaya), and the small township of Baikunthpur (now called Baikathpur, in Bihar's Patna district), and carried out massive repairs and fresh construction, including of palaces, at the fort of Rohtas

- ^ Mitra 2002, p. 182.

- ^ a b Prakash 1981, p. 170.

- ^ Schreitmüller 2012, p. 284.

- ^ Limited, Eicher Goodearth (2002). Good Earth Varanasi City Guide. Eicher Goodearth Limited. p. 124. ISBN 978-81-87780-04-5.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "When Kashi Naresh suggested India establish Varanasi as a free city, like the Vatican". Moneycontrol. 14 August 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ Bayly, C. A. (19 May 1988). Rulers, Townsmen and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion, 1770–1870. CUP Archive. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-0-521-31054-3. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d Bayly, Christopher Alan (1983). Rulers, Townsmen, and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion, 1770–1870. Cambridge University Press. p. 489 (at p 18). ISBN 978-0-521-31054-3.

- ^ a b Benares (Princely State) Archived 21 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine – A Document about Maharajas of Varanasi

- ^ Aitchison, Chalres Umpherston (1857). "Translation of the Proposed Articles of the Treaty with the Nabob Ausuf-ul-Dowla,— 21st May 1775: Article 5". A Collection Of Treaties, Engagements And Sanads. Vol. 2. Delhi: Mittal Publications. p. 107. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

the English Company shall, after one month and a half from the date of this Treaty, take upon them the sovereignty and possession of the districts under Rajah Cheyt Sing, as hereunder specified, viz- Sircar Benares

- ^ Real Corp 2007.

- ^ Kochhar 2015, p. 247.

- ^ Matthew Atmore Sherring. "3". The Sacred City of the Hindus An Account of Benares in Ancient and Modern Times (First ed.). London: Trübner & Company. p. 41.

- ^ Twain 1897, p. Chapter L.

- ^ "A review of Varanasi". Blonnet.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2009. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ Mitra 2002, p. 216.

- ^ Sharma & Sharma 2001, p. 197.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Varunwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Uttar Pradesh – The British period". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2021.