2021 in archosaur paleontology: Difference between revisions

Macrochelys (talk | contribs) |

BigBoi1003 (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 514: | Line 514: | ||

|{{Flag|United Kingdom}} |

|{{Flag|United Kingdom}} |

||

|A non-hadrosaurid [[Ankylopollexia|hadrosauriform]]. The type species is ''B. simmondsi''. |

|A non-hadrosaurid [[Ankylopollexia|hadrosauriform]]. The type species is ''B. simmondsi''. |

||

|[[File:Brighstoneus.png|frameless]] |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| |

| |

||

Revision as of 17:46, 23 August 2024

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

This article records new taxa of fossil archosaurs of every kind that are scheduled described during the year 2021, as well as other significant discoveries and events related to paleontology of archosaurs that are scheduled to occur in the year 2021.

General research

- A study on the relationship between full potential joint mobility and the poses used during locomotion in extant American alligator and helmeted guineafowl, evaluating its implications for reconstructions of locomotion of extinct archosaurs, is published by Manafzadeh, Kambic & Gatesy (2021).[1]

- A study on the femoral shape variation and on the relationship between femoral morphology and locomotor habits in early archosaurs and non-archosaur archosauriforms is published by Pintore et al. (2021).[2]

- A study estimating moment arms for major pelvic limb muscles in extant and fossil archosaurs, aiming to investigate the idea that bird-line archosaurs switched from hip-based to knee-based locomotion between Archosauria (especially Neotheropoda) and Aves, is published by Allen, Kilbourne & Hutchinson (2021).[3]

- A study aiming to determine how ontogenetic changes in skeletal anatomy influence muscle size, leverage, orientation, and locomotor function during the development of flight in extant chukar partridge is published by Heers et al. (2021), who evaluate the implications of their findings on current knowledge of how extinct winged theropods might have achieved bird-like behaviors before acquiring fully bird-like anatomies.[4]

- A study on jumping mechanics and performance in extant elegant crested tinamou, and on its implications for inferences of jumping abilities in extinct animals such as dromaeosaurid dinosaurs, is published by Bishop et al. (2021).[5]

- A study on the morphological diversity and evolution of the semicircular canals of the inner ear in extant and fossil archosaurs is published by Bronzati et al. (2021).[6]

- A study on the evolution of eggshell thickness in non-avian dinosaurs and birds is published by Legendre & Clarke (2021).[7]

- A study on the evolution of birdlike locomotor abilities and hearing acuity, as indicated by the anatomy of the inner ear in extant and fossil reptiles and birds, is published by Hanson et al. (2021);[8] the conclusions of the study are subsequently contested by David, Bronzati & Benson (2022).[9][10]

- A study assessing the accuracy of bite force estimates in extinct archosaurs and mammals is published by Sakamoto (2021).[11]

- A study on the composition of the assemblage of isolated archosaur (dinosaur and crocodyliform) teeth and osteoderms from the Upper Cretaceous Cerro Fortaleza Formation (Argentina), and on its implications for the knowledge of the archosaur biodiversity in southern Patagonia during the Late Cretaceous, is published by Paulina-Carabajal et al. (2021).[12]

- A study on evolution of the expression of carotenoids in skin and other integumentary structures of archosaurs is published by Davis & Clarke (2021).[13]

- A study on the ossification patterns of the respiratory turbinate in extant birds, and on their implications for the identification of the positions and form of possible osteological correlates of the respiratory turbinate in non-avian dinosaurs, is published by Tada & Tsuihiji (2021).[14]

- Revision of the Mesozoic and Cenozoic record of large, unwebbed bird and bird-like footprints is published by Lockley, Abbassi & Helm (2021).[15]

Pseudosuchians

New Pseudosuchian taxa

| Name | Novelty | Status | Authors | Age | Type locality | Country | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Blanco |

An allodaposuchid eusuchian, a species of Allodaposuchus. |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Yoshida et al. |

A goniopholidid crocodyliform, a species of Amphicotylus. |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Nicholl et al. |

Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian) |

A peirosaurid crocodylomorph. The type species is A. taouzensis. |

| |||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Darlim, Montefeltro & Langer |

Bauru Basin |

A baurusuchid crocodylomorph. The type species is A. escharafacies. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

In press |

Salih et al. |

A dyrosaurid crocodylomorph. The type species is B. kababishensis. |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Novas et al. |

An early member of Mesoeucrocodylia. The type species is B. mallingrandensis. |

| ||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Ruiz et al. |

A sphagesaurid crocodylomorph, a species of Caipirasuchus. |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Stocker, Brochu & Kirk |

A caiman. The type species is C. wilsonorum. |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Pinheiro et al. |

A sphagesaurian crocodylomorph. The type species is C. civali |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Sachs, Young, Abel, & Mallison |

A metriorhynchid thalattosuchian, a species of Cricosaurus. |

|||||

| Cricosaurus puelchorum[26] | Sp. nov | Valid | Herrera, Fernández & Vennari | Early Cretaceous (Berriasian) | Vaca Muerta | A metriorhynchid thalattosuchian, a species of Cricosaurus. Announced in 2020; the final version of the article naming it was published in 2021. |

| |

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Herrera, Aiglstorfer & Bronzati |

A metriorhynchid thalattosuchian, a species of Cricosaurus. | |||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Shan et al. |

An alligatoroid belonging to the group Orientalosuchina. The type species is D. hsui. |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Marinho et al. |

Late Cretaceous |

A notosuchian crocodylomorph. The type species is E. viridi. Announced in 2021; the final version of the article naming it was published in 2022. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Tolchard et al. |

A non-crocodylomorph loricatan. The type species is E. recurvidens. |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Ristevski et al. |

A tomistomine crocodylian. The type species is G. maunala. |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Czepiński et al. |

An aetosaur. The type species is K. silvestris. |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Bravo, Pol & García-López |

Mealla Formation | A sebecid mesoeucrocodylian, a species of Sebecus. | ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Rummy et al. |

A paralligatorid crocodyliform. The type species is Y. longshanensis. Announced in 2021; the final version of the article naming it was published in 2022. |

Crocodylomorph research

- A study on the morphological diversity of skull and jaw shape in crocodylomorphs throughout their evolutionary history is published by Stubbs et al. (2021).[35]

- A study on the evolution of the skull morphology in crocodyliforms is published by Felice, Pol & Goswami (2021).[36]

- A study on the anatomy, phylogenetic relationships and stratigraphy of the holotype specimen of Notochampsa istedana is published by Dollman et al. (2021).[37]

- A study on the skull anatomy and phylogenetic placement of Eopneumatosuchus colberti is published by Melstrom, Turner & Irmis (2021).[38]

- A study on the bite force in mesoeucrocodylians throughout their evolutionary history is published by Gignac, Smaers & O'Brien (2021).[39]

- A study on feeding habits of notosuchians from the Upper Cretaceous Bauru Group (Brazil), as indicated by stable carbon and oxygen isotope data from tissues of notosuchians from two sites from Bauru Group, is published by Klock et al. (2021).[40]

- Description of coprolites from the Upper Cretaceous Adamantina Formation (Brazil) found in association with skeletons of baurusuchid and sphagesaurid crocodylomorphs, and a study on the implications of these coprolites for the knowledge of the diet of these crocodylomorphs, is published by de Oliveira et al. (2021).[41]

- A study on the morphological variation in the dentition of uruguaysuchid crocodylomorphs is published by Figueiredo & Kellner (2021).[42]

- A study on the bone histology and growth dynamics of Araripesuchus, based on data from specimens from the La Buitrera Palaeontological Area (Río Negro Province, Argentina), is published by Fernández Dumont et al. (2021).[43]

- A study on the resistance to stress of the skull of Araripesuchus gomesii, and on its implications for the knowledge of likely diet of this crocodylomorph, is published by Nieto et al. (2021).[44]

- New partially preserved skull of Campinasuchus dinizi is described from the Fazenda São José (Adamantina/Vale do Rio do Peixe Formation, Brazil) by Darlim et al. (2021), who evaluate the implications of this specimen for the knowledge of the distribution of baurusuchids in the Late Cretaceous of South America.[45]

- The first known baurusuchid yearling is described from the Adamantina Formation (Brazil) by dos Santos et al. (2021).[46]

- New baurusuchid specimen, providing new information on the skeletal growth in baurusuchids, is described from the Upper Cretaceous Adamantina Formation (Brazil) by Marchetti et al. (2021).[47]

- A study on the anatomy of the endocranial structures of Zulmasuchus querejazus, and on its implications for the knowledge of the head posture, hearing capabilities and likely lifestyle of this sebecid, is published by Pochat-Cottilloux et al. (2021).[48]

- New soft tissue records for thalattosuchians are reported from the Late Jurassic localities of Wattendorf and Painten (Bavaria, Germany) by Spindler et al. (2021), who interpret their findings as indicating the skin of metriorhynchids lacked any traces of scales or scutes and instead showed folded and transverse fibers.[49]

- A study on the nasal and paranasal anatomy of thalattosuchians, and on its implications for the knowledge of the evolution of the paranasal sinus system and nasopharyngeal ducts in Thalattosuchia, is published by Cowgill et al. (2021).[50]

- Description of the cranial and endocranial anatomy of Macrospondylus bollensis is published by Wilberg et al. (2021).[51]

- A study on the innervation of the rostrum of metriorhynchoid thalattosuchians, and on its implications for the knowledge of the somatosensory abilities of these crocodylomorphs, is published by Bowman et al. (2021).[52]

- Isolated metriorhynchid tooth crowns, representing some of the most recent known occurrences of Metriorhynchidae worldwide, are described from the Valanginian Kopřivnice Formation (Czech Republic) by Madzia et al. (2021), who interpret these specimens as evidence of the presence of two distinct lineages of geosaurin metriorhynchids in the area of Czech Republic during the Early Cretaceous.[53]

- A study on the anatomy of the braincase of a metriorhynchid specimen belonging or related to the species "Metriorhynchus" brachyrhynchus, and on the evolution of neurosensory and endocranial systems of metriorhynchids, is published by Schwab et al. (2021).[54]

- A study on the anatomy of the snout of Dakosaurus andiniensis, and on the evolution of the facial anatomy of thalattosuchians, is published by Fernández & Herrera (2021), who interpret their findings as indicative of presence of anatomical adaptations likely helping drainage of nasal glands (probably excreting salt).[55]

- A study on histology and stable isotope geochemistry of the fossil material of Goniopholis and Dyrosaurus, and on their implications for the knowledge whether these crocodylomorphs were ectotherms or endotherms, is published by Faure-Brac et al. (2021).[56]

- A study on the evolution of tethysuchian and gavialoid crocodylomorphs from the Campanian to the Thanetian is published by Jouve (2021).[57]

- A study on the histology of the humeri and femora of Hyposaurus rogersii is published by Pellegrini et al. (2021).[58]

- A study on the anatomy of the braincase and inner ear of Rhabdognathus aslerensis is published by Erb & Turner (2021).[59]

- A study on the anatomy of the postcranial skeleton of Cerrejonisuchus improcerus is published by Scavezzoni & Fischer (2021), who also provide new information on the anatomy of the postcranial skeletons of Congosaurus bequaerti and Hyposaurus rogersii, and provide evidence of a distinctive postcranial anatomy of dyrosaurids among crocodyliforms.[60]

- New fossil material of Deltasuchus motherali, providing new information on changes in the skeleton of this crocodyliform during the ontogeny, and indicative of dietary shifts from juvenile to adult, is described from the Cenomanian Woodbine Formation (Texas, United States) by Drumheller et al. (2021), who also study the phylogenetic relationships of D. motherali, and identify an endemic clade of Appalachian crocodyliforms, which they name Paluxysuchidae.[61]

- Redescription and a study on the phylogenetic relationships of Duerosuchus piscator is published by Narváez et al. (2021).[62]

- A study on the phylogenetic relationships and the evolutionary history of crocodilians is published by Rio & Mannion (2021).[63]

- New fossil material of Deinosuchus, representing one of the earliest records of this genus in North American reported to date, is described from the Campanian Menefee Formation (New Mexico, United States) by Mohler, McDonald & Wolfe (2021).[64]

- Description of the crocodyliform fossil material from the Eocene (Lutetian) Ikovo locality (Ukraine), including the easternmost record of diplocynodontines in Europe reported to date, is published by Kuzmin & Zvonok (2021), who also review the fossil record and biogeography of crocodyliforms from the Paleocene and Eocene of Europe.[65]

- Description of additional fossil material of Tsoabichi greenriverensis from the Eocene Green River Formation, providing further evidence for its caimanine affinities, and a study on the evolutionary history of caimanines is published by Walter et al. (2021).[66]

- Cidade & Rincón (2021) report the first occurrence of Acresuchus pachytemporalis from the Miocene Urumaco Formation (Venezuela), expanding known geographic distribution of this species.[67]

- Description and a study on the taxonomic status of the crocodylians from the Neogene Irrawaddy Formation (Myanmar), including one of the oldest records of the genus Gavialis reported to date, is published by Iijima et al. (2021).[68]

- Revision of the taxonomy and a study on the phylogenetic relationships of the Miocene tomistomines from Italy and Malta is published by Nicholl et al. (2021).[69]

- A study on the phylogenetic relationships of Voay robustus, based on mitochondrial genomic data, is published by Hekkala et al. (2021).[70]

- Description of a new skull of Crocodylus anthropophagus from the DK site at Olduvai (Tanzania), representing the oldest fossil of a member of this species reported to date, and a study on the phylogenetic relationships of this species is published by Azzarà et al. (2021)[71]

Aetosaur research

- Description of the braincase of Aetosauroides scagliai, based on data from specimens from the Upper Triassic Candelária Sequence (Brazil), is published by Paes Neto et al. (2021).[72]

- Description of the skull Aetosauroides scagliai, and a study on the likely diet and paleobiology of this aetosaur, is published by Paes Neto et al. (2021).[73]

- A study on the anatomy of the axial skeleton of Aetosauroides is published by Paes-Neto et al. (2021), who propose that Polesinesuchus aurelioi is a junior synonym of Aetosauroides scagliai.[74]

- An incomplete, largely articulated postcranial skeleton of a basal aetosaur, possibly distinct from Aetosauroides scagliai, and preserving anatomical features which aren't often preserved in aetosaur specimens (including extensive appendicular armor and a well-preserved caudal ventral carapace), is described from the Upper Triassic Ischigualasto Formation (Argentina) by Hecket, Martínez & Celeskey (2021).[75]

- An osteoderm of Typothorax coccinarum with punctures and scores which are likely bite marks is described from the Upper Triassic Chinle Formation (Arizona, United States) by Drymala, Bader & Parker (2021), who interpret this finding as supporting the hypothesis that aetosaurs were prey items of large archosauromorphs.[76]

- Reyes, Parker & Marsh (2021) describe the first complete articulated skull of Typothorax coccinarum from the Owl Rock Member of the Chinle Formation (Petrified Forest National Park), and evaluate the implications of this specimen for the knowledge of the relationships and morphological diversity of aetosaurs.[77]

- A study on the biomechanical properties of the skull of Neoaetosauroides engaeus is published by Taborda, Desojo & Dvorkin (2021).[78]

- Revision of isolated braincases of Desmatosuchus from the Placerias Quarry locality in the Chinle Formation (Arizona, United States) is published by von Baczko et al. (2021), who report the presence of two species of Desmatosuchus (D. spurensis and D. smalli) at the Placerias Quarry.[79]

General pseudosuchian research

- A study on the phylogenetic relationships of pseudosuchian archosaurs, aiming to determine drivers of body size evolution in this group, is published by Stockdale & Benton (2021);[80] the study is subsequently criticized by Benson et al. (2022).[81][82]

- The first occurrence of the track type "Chirotherium" lulli (inferred to be produced by a pseudosuchian archosaur) from western North America is reported from the Owl Rock Member of the Chinle Formation (Utah, United States) by Milner et al. (2021).[83]

- A study on the skeletal anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Revueltosaurus callenderi is published by Parker et al. (2021).[84]

- A study on the skull anatomy and likely feeding habits of Effigia okeeffeae is published by Bestwick et al. (2021).[85]

Non-avian dinosaurs

New non-avian dinosaur taxa

| Name | Novelty | Status | Authors | Age | Type locality | Country | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ajnabia[86] | Gen. et sp. nov | Valid | Longrich et al. | Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) | Ouled Abdoun Basin | A lambeosaurine hadrosaurid. The type species is A. odysseus. Announced in 2020; the final version of the article naming was published in 2021. |

| |

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Rubilar-Rogers et al. |

A lithostrotian titanosaur sauropod. The type species is A. licanantay. |

| ||||

|

Gen. et comb. nov |

Valid |

Silva Junior et al. |

A titanosaur sauropod; a new genus for "Aeolosaurus" maximus. |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Disputed |

Hocknull et al. |

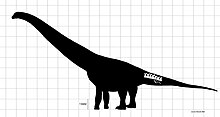

A titanosaur sauropod. The type species is A. cooperensis. Considered to be an indeterminate diamantinasaurian and a possible junior synonym of Diamantinasaurus matildae by Beeston et al. (2024).[90] |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

De Souza et al. |

A noasaurid theropod. The type species is B. leopoldinae. |

| ||||

| Brighstoneus[92] | Gen. et sp. nov | Valid | Lockwood et al. | Early Cretaceous (Barremian) | Wessex Formation | A non-hadrosaurid hadrosauriform. The type species is B. simmondsi. |

| |

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Barker et al. |

Early Cretaceous (Barremian) |

A spinosaurid theropod. The type species is C. inferodios. |

| |||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Averianov & Sues |

A sauropod of uncertain phylogenetic placement. Originally described as a rebbachisaurid, but subsequently argued to be a member of Titanosauria.[95] The type species is D. kingi. |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Müller |

A basal theropod. The type species is E. jacuiensis. Announced in 2020; the final version of the article naming it was published in 2021. |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Prieto-Márquez and Carrera Farias |

A non-hadrosaurid hadrosauromorph. The type species is F. thyrakolasus. |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Díez Díaz et al. |

Late Cretaceous (Campanian) |

A titanosaur sauropod. Genus includes new species G. meridionalis. Announced in 2020; the final version of the article naming it was published in 2021. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Wang et al. |

Early Cretaceous |

A titanosaur sauropod. The type species is H. xinjiangensis. |

| |||

| Issi[100] | Gen. et sp. nov | Beccari et al. | Late Triassic (Norian) | Malmros Klint Formation | A plateosaurid sauropodomorph. The type species is I. saaneq. |  | ||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Averianov and Lopatin |

A velociraptorine dromaeosaurid. The type species is K. sogdianus. |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Averianov & Lopatin |

Late Cretaceous (Campanian) |

An alvarezsaurid theropod. The type species is K. magnificus. |

||||

| Kuru[103] | Gen. et sp. nov | Valid | Napoli et al. | Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) | Barun Goyot Formation | A dromaeosaurid theropod. The type species is K. kulla. |  | |

| Kurupi[104] | Gen. et sp. nov | Valid | Iori et al. | Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) | Marília Formation | An abelisaurid theropod. The type species is K. itaata. |  | |

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Gianechini et al. |

A furileusaurian abelisaurid. The type species is L. aliocranianus. | |||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Dalman et al. |

A centrosaurine ceratopsid, possibly a member of the tribe Nasutoceratopsini. The type species is M. sealeyi. |

| ||||

| Gen. et sp. nov | Valid | Rolando et al. | Late Cretaceous (Campanian-Maastrichtian) | Allen Formation | A titanosaur sauropod. The type species is M. arriagadai. Announced in 2021; the final version of the article naming it was published in 2022. | |||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Ji & Zhang |

Early Cretaceous |

A basal member of Iguanodontia. The type species is N. guangxiensis. Announced in 2021; the final version of the article naming it was published in 2022. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Gallina, Canale, & Carballido |

The earliest known titanosaur sauropod found. The type species is N. zapatai. |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Tan et al. |

A mamenchisaurid sauropod, a species of Omeisaurus. Announced in 2020; the final version of the article naming was published in 2021. | |||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

McDonald et al. |

A saurolophine hadrosaurid belonging to the tribe Brachylophosaurini. The type species is O. incantatus. |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Pei et al. |

A troodontid theropod. The type species is P. neimengguensis. Announced in 2021; the final version of the article naming it must be published in 2022. |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Spiekman et al. |

A basal theropod. The type species is P. milnerae |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Santos-Cubedo et al. |

A styracosternan hadrosauroid. The type species is P. sosbaynati |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Upchurch et al. |

A sauropod belonging to the family Mamenchisauridae. The type species is R. turpanensis. |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Barker et al. |

Early Cretaceous (Barremian) |

A spinosaurid theropod. The type species is R. milnerae. |

| |||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Turner, Montanari & Norell |

A dromaeosaurid theropod. The type species is S. devi. |

| ||||

| Sierraceratops[117] | Gen. et sp. nov | Valid | Dalman, Lucas Jasinski, & Longrich | Late Cretaceous (latest Campanian–Maastrichtian) | Hall Lake Formation | ( |

A chasmosaurine ceratopsid. The type species is S. turneri. Announced in 2021; the final version of the article naming it must be published in 2022. |  |

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Wang et al. |

Early Cretaceous |

Shengjinkou Formation |

A sauropod belonging to the family Euhelopodidae. The type species is S. sinensis. |

| ||

|

Gen. et comb. nov |

Valid |

Evans et al. |

Late Cretaceous |

Ulansuhai Formation |

A pachycephalosaur previously classified as Stegoceras. The type species is "Troodon" bexelli Bohlin (1953). |

|||

| Spicomellus[119] | Gen. et sp. nov | Valid | Maidment et al. | Middle Jurassic (Bathonian-Callovian) | El Mers Group | An ankylosaur. The type species is S. afer. | ||

| Stegouros[120] | Gen. et sp. nov | Soto-Acuña et al. | Late Cretaceous (Campanian-Maastrichtian) | Dorotea Formation | An ankylosaur. The type species is S. elengassen. |

| ||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Sellés et al. |

A troodontid theropod. The type species is T. insperatus. |

| ||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Park et al. |

Late Cretaceous (Campanian-Maastrichtian) |

An ankylosaurid, a species of Tarchia. |

| |||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Ramírez-Velasco et al. |

A lambeosaurine hadrosaurid belonging to the tribe Parasaurolophini. The type species is T. galorum. |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Dubious |

Tanaka et al. |

Late Cretaceous (Turonian) |

A theropod of uncertain affinities; originally assigned to the group Carcharodontosauria, but Sues, Averianov & Britt (2022) subsequently argued that it lacked unambiguous diagnostic features of that clade.[125] The type species is U. uzbekistanensis. |

| |||

| Vectiraptor[126] | Gen. et sp. nov | In press | Longrich, Martill, & Jacobs | Early Cretaceous (Barremian) | Wessex Formation | A dromaeosaurid theropod. The type species is V. greeni. | ||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Kobayashi et al. |

A basal hadrosaurid. The type species is Y. izanagii. |

| ||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Brum et al. |

An unenlagiine dromaeosaurid. The type species is Y. lopai. |

|

Research

General

- A study on the impact of the disparity between neonates and adults on the structure and diversity of dinosaur communities is published by Schroeder, Lyons & Smith (2021), who claim that communities with giant theropods lacked carnivores weighing 100 to 1000 kg, and argue that juveniles of giant theropod species likely filled the mesocarnivore niche, resulting in reduced overall taxonomic diversity;[129] their conclusions are subsequently contested by Benson et al. (2022).[130][131]

- Evidence of cessation of longitudinal skeletal growth in non-avian dinosaurs, inferred from a study of the articular surfaces of long bones, is presented by Rothschild & Witzmann (2021).[132]

- A study aiming to determine the survivorship curves of Albertosaurus sarcophagus, Gorgosaurus libratus, Daspletosaurus torosus, Tyrannosaurus rex, Maiasaura peeblesorum and Psittacosaurus lujiatuensis in populations with an age distribution which was stable in shape over time is published by Griebeler (2021).[133]

- A study aiming to determine whether the presence of keratan sulfate is exclusive evidence for the presence of medullary bone in dinosaur fossils (and therefore whether it can be used to identify dinosaur specimens as gravid females) is published by Canoville et al. (2021).[134]

- A study on the variation in tail anatomy and length across the Dinosauria is published by Hone, Persons & Le Comber (2021).[135]

- A study on the possibilities of determination of the presence of sexual dimorphism in dinosaurs, evaluating whether the previous method used for dinosaurs correctly recognizes living animals as dimorphic, is published by Motani (2021).[136]

- A study on the role of climate in shaping the geographic distribution of Mesozoic dinosaurs is published by Chiarenza et al. (2021).[137]

- Review of the fossil record of Carnian dinosaurs from South America is published by Novas et al. (2021), who also interpret Chindesaurus, Daemonosaurus and Tawa as likely late-surviving members of Herrerasauria.[138]

- A study on dinosaur trackways that show changes in direction from Jurassic and Cretaceous sites in North and South America, Europe and Asia is published by Lockley et al. (2021).[139]

- Fossil trackways made by theropods, ornithopods and possibly ankylosaurs, are reported from the Folkestone Formation of the Lower Greensand Group by Hadland et al (2021), representing the youngest known footprints of non-avian dinosaurs known from the United Kingdom.[140]

- A new dinosaur trackway is reported from the Early Cretaceous Eumeralla Formation (Wattle Hill, Australia), by Romilio and Godfrey (2021), who report the presence of ornithopod and bird-like tracks, as well as a large theropod footprint possibly belonging to the ichnogenus Megalosauropus.[141]

- A study on the climate of the Lufeng area (China) during the Early Jurassic, and on the relations between the global distribution of dinosaur fossils and climate during the Jurassic, is published by Shen et al. (2021).[142]

- A study on the relationships between diet, tooth complexity and tooth replacement rates in Late Jurassic dinosaurs is published by Melstrom, Chiappe & Smith (2021).[143]

- Description of the fossil material of a tyrannosauroid theropod and an early member of the family Hadrosauridae from the Upper Cretaceous Merchantville Formation (Delaware and New Jersey, United States), possibly representing new taxa, and a study on the phylogenetic affinities of these dinosaurs is published by Brownstein (2021).[144]

- Druckenmiller et al. (2021) report the discovery of a diverse assemblage of herbivorous and carnivorous non-avian dinosaurs, including perinatal and very young specimens, from the Upper Cretaceous Prince Creek Formation (Alaska, United States), and interpret this finding as indicating that most, if not all, dinosaurs from this assemblage were nonmigratory year-round Arctic residents.[145]

- A study on the distribution of dinosaurs across the latest Cretaceous of North America is published by García‐Girón et al. (2021).[146]

- A study aiming to determine whether plant-eating dinosaurs could have moved seeds long distances is published by Perry (2021).[147]

- Dinosaur tracks with elongated metatarsal marks and superficially human-like appearance are interpreted by Lallensack, Farlow & Falkingham (2021) as more likely to be caused by deep penetrations of the foot in soft sediment than by a plantigrade mode of locomotion.[148]

- A study on changes of diversity of dinosaurs belonging to the families Ankylosauridae, Ceratopsidae, Hadrosauridae, Dromaeosauridae, Troodontidae and Tyrannosauridae during the Late Cretaceous is published by Condamine et al. (2021), who interpret their findings as indicative of a decline of non-avian dinosaur diversity during the last 10 million years of the Cretaceous period, and attempt to determine possible causes of this decline.[149]

- The study published by Bonsor et al. (2020), aiming to determine whether non-avian dinosaurs were in long-term decline prior to the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event,[150] is criticized by Sakamoto, Benton & Venditti (2021).[151]

- A study on a dinosaur nesting site preserved in the Upper Cretaceous Wido Volcanics (Wi Island, South Korea) is published by Kim et al. (2021; final version published in 2022), providing new information on how these dinosaurs chose their nesting sites.[152]

Saurischians

- New fossil material of theropod and sauropod dinosaurs, including a caudal vertebra with pneumatic internal structures rarely observed outside Late Cretaceous South American saltasaurines, is described from the Campanian Quseir Formation (Egypt) by Salem et al. (2021).[153]

- Evidence indicating that some mid-sized dendroolithid eggs were laid by a therizinosauroid theropod is presented by Kundrát & Cruickshank (2021), who also report the discovery of putative embryonic remains (possibly of a titanosaur sauropod) in a faveoloolithid egg.[154]

- Putative large-sized sauropodomorph specimen from the Carnian strata at the 'Cerro da Alemoa' locality (southern Brazil) is reinterpreted as a herrerasaurid specimen (the largest dinosaur reported from the Candelária Sequence to date) by Garcia et al. (2021).[155]

- Putative tracks of a large-bodied predatory dinosaur from the Upper Triassic Blackstone Formation (Australia) are reinterpreted by Romilio et al. (2021) as sharing characteristics with the sauropodomorph ichnogenus Evazoum, and possibly representing the first evidence of basal sauropodomorph dinosaurs from Australia.[156]

Theropods

- A study aiming to determine whether the knowledge of patterns of species abundance and clade diversity in theropod dinosaurs is significantly impacted by the diagnosability of their fossils is published by Cashmore, Butler & Maidment (2021).[157]

- A study on the evolution of vision and hearing modalities in theropod dinosaurs is published by Choiniere et al. (2021), who interpret their findings as indicative of early evolution of nocturnal predation in alvarezsauroid theropods.[158]

- A study on changes of feeding mechanics of theropods throughout their evolutionary history is published by Ma et al. (2021).[159]

- Bishop et al. (2021) create three-dimensional simulations of gait in Coelophysis bauri, and interpret their findings as indicative of a crucial and dynamic role of the tail in the locomotion of this theropod.[160]

- A vertebra of a non-coelophysoid, non-averostran neotheropod which may be 15 million years older than Dilophosaurus wetherilli is described from the Lower Jurassic (Hettangian) Whitmore Point Member of the Moenave Formation (Utah, United States) by Marsh et al. (2021), who interpret this finding as indicating that not all contemporaneous theropod traces were made by coelophysoids.[161]

- McMenamin (2021) describes a humerus of a neotheropod from the Portland Formation of the Early Jurassic (Massachucetts, USA) older and larger than Dilophosaurus, and interpret it as a large piscovorous creature based on the locale's ecology.[162]

- An assemblage of over 100 theropod footprints of various size and morphology is described from the Lower Jurassic Fengjiahe Formation (China) by Li et al. (2021), representing the track site with the largest number of theropod footprints in Yunnan reported to date.[163]

- New fossil material of ceratosaur theropods, probably representing one of the oldest known record of abelisaurids, is described from the Upper Jurassic Cañadón Calcáreo Formation (Argentina) by Rauhut & Pol (2021).[164]

- A study on the skeletal anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Xenotarsosaurus bonapartei is published by Ibiricu et al. (2021).[165]

- Two new furileusaurian abelisaurid specimens from the Santonian Bajo de la Carpa Formation (Argentina), providing new information on the abundance of abelisaurids in this area and on variety of abelisaurid morphotypes that coexisted in the north of Argentine Patagonia during the Late Cretaceous, are described by Méndez et al. (2021; final version published in 2022).[166]

- Description of the preserved integument of Carnotaurus sastrei is published by Hendrickx & Bell (2021).[167]

- Revision of the phylogenetic affinities and evolutionary significance of Saltriovenator zanellai and Scipionyx samniticus is published by Cau (2021), who interprets his findings as raising doubts on the systematic status of theropod specimens assigned to the family Compsognathidae, which might turn out to be immature individuals belonging to various lineages of large-bodied tetanurans, with the holotype specimen of S. samniticus possibly being an immature carcharodontosaurid.[168]

- Two trackways belonging to fast-running theropods (probably basal tetanurans) are described from the Lower Cretaceous Enciso Group (Spain) by Navarro-Lorbés et al. (2021), who present the speeds of locomotion calculated for both trackways, which are among the top speeds ever calculated for non-avian theropod tracks, and interpret one of the trackways as produced by a dinosaur with the ability to make and control substantial speed changes while running.[169]

- Spinosaurid neck vertebrae distinct from known vertebrae of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus and exhibiting an unusual combination of positionally variable characters are described from the Kem Kem Group (Morocco) by McFeeters (2021), who interprets this finding as evidence of a greater degree of intraspecific variation in the vertebrae of S. aegyptiacus than previously recognized, or alternatively, evidence for the occurrence of two spinosaurid taxa in the Kem Kem Group.[170]

- Spinosaurid caudal vertebrae are described from the Lower Cretaceous Sao Khua Formation (Thailand) by Samathi, Sander & Chanthasit (2021), who also reinterpret the putative ceratosaur Camarillasaurus cirugedae as a spinosaurid.[171]

- A study on the diversity of the premaxillae shape in spinosaurids, an on its implications for the knowledge of the phylogenetic relationships of the spinosaurids, is published by Lacerda, Grillo & Romano (2021).[172]

- Hone & Holtz (2021) evaluate the evidence for the competing interpretations of the ecology of Spinosaurus, and reject the interpretation of this theropod as a specialised aquatic pursuit predator.[173]

- Pahl and Ruedas (2021) suggest that carnosaurs like Allosaurus were primarily scavengers that fed on sauropod carcasses, which they consider to be analogous to whale falls;[174] however, their conclusions are criticized by Kane et al. (2023)[175] but later defended by Pahl and Ruehdas (2023).[176]

- A study on the histology and geochemistry of a tibia and a femur of a specimen or specimens of Allosaurus fragilis from the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry (Utah, United States), and on its implications for the knowledge of the growth strategy of this species, is published by Ferrante et al. (2021).[177]

- Caudal vertebra of a theropod with affinities to Carcharodontosauria is described from the Upper Jurassic Sergi Formation by Bandeira et al. (2021), representing the first unambiguous record of a dinosaur from the Jurassic of Brazil reported to date.[178]

- A study on the phylogenetic affinities of putative carcharodontosaurid teeth from the Upper Cretaceous strata in northern and central Patagonia, and on their implications for the knowledge of the timing of extinction of carcharodontosaurids in South America, is published by Meso et al. (2021).[179]

- Description of new fossil material of Phuwiangvenator yaemniyomi from the Lower Cretaceous Sao Khua Formation (Thailand), and a study on its implications for the knowledge of the early evolution of Megaraptora, is published by Samathi et al. (2021).[180]

- A study on the skeletal anatomy of Aerosteon riocoloradensis is published by Aranciaga Rolando et al. (2021).[181]

- Fragmentary specimens of tyrannosaurid theropods from the Dinosaur Park Formation of the Alberta, Canada) in the collection of the San Diego Natural History Museum were described by Yun (2021).[182]

- Bones of tyrannosaurid theropods with extensive tooth marks matching the teeth of tyrannosaurids are described from the Upper Cretaceous of the San Juan Basin (northwestern New Mexico, United States) by Dalman & Lucas (2021), who interpret this finding as evidence for cannibalistic behavior among tyrannosaurids.[183]

- Caneer, Moklestad & Lucas (2021) describe structures which are not readily assignable to any known ichnotaxon from the Upper Cretaceous of the Raton Basin (New Mexico), and interpret them as one footprint and two forearm/hand prints probably produced by a large tyrannosaurid theropod standing up from a prone position.[184]

- Perinatal tyrannosaurid bones and teeth are described from the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation (Montana, United States) and Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Alberta, Canada) by Funston et al. (2021), who evaluate the implications of these findings for the knowledge of the minimum hatchling size of tyrannosaurids, their nesting habits and development of their teeth.[185]

- A study on tyrannosaurid tracks from the Campanian Wapiti Formation (Alberta, Canada), evaluating the implications of these tracks for the knowledge of changes in pedal anatomy of tyrannosaurids during their ontogeny, is published by Enriquez et al. (2021).[186]

- Tyrannosaurid fossil material is described from the Blagoveshchensk and Kundur fossil localities (Amur Region, Russia) by Bolotsky, Ermatsans & Bolotsky (2021).[187]

- A study on possible causes of monopolization of large carnivore guilds in Asian and American dinosaur assemblages by tyrannosaurids in the latest Cretaceous is published by Holtz (2021).[188]

- A study on the morphology, frequency, and ontogeny of facial bite marks in tyrannosaurid specimens is published by Brown, Currie & Therrien (2021), who interpret the ontogenetic distribution of bite scars in the studied specimens as possible evidence of agonistic behaviour associated with the onset of sexual maturity.[189]

- A study on changes of mandibular biomechanical properties and tooth morphology in Albertosaurus sarcophagus and Gorgosaurus libratus during their ontogeny is published by Therrien et al. (2021), who interpret their findings as indicating the occurrence of ontogenetic dietary shift in albertosaurine tyrannosaurids.[190]

- A study on the mechanical properties of the mandibles of tyrannosaurine tyrannosaurids representing different ontogenetic stages (including small juvenile) is published by Rowe & Snively (2021).[191]

- New bone bed containing at least four specimens of Teratophoneus curriei or a related tyrannosaurid is described from the Campanian Kaiparowits Formation (Utah, United States) by Titus et al. (2021), who study the taphonomy of this bone bed, and evaluate its implications for the knowledge whether known accumulations of tyrannosaurid specimens represent time-averaged or forced accumulations, or whether they are evidence of gregariousness of tyrannosaurids.[192]

- A metatarsal of juvenile tyrannosaurid theropod from the Dinosaur Park Formation of the Alberta, Canada, possibly referable to Daspletosaurus torosus was described by Yun (2021).[193]

- A study on the anatomy of the braincases of two specimens of Daspletosaurus is published by Paulina Carabajal et al. (2021).[194]

- A study aiming to calculate population variables such as abundance at any one time, species persistence and total number of individuals that ever lived for Tyrannosaurus rex is published by Marshall et al. (2021);[195] the study is subsequently criticized by Meiri (2022).[196][197]

- A study aiming to estimate the natural frequency of the vertical swaying of the tail and the preferred walking speed and step frequency of Tyrannosaurus rex is published by van Bijlert, van Soest & Schulp (2021).[198]

- A study on the morphology of the neurovascular canal in the dentary of Tyrannosaurus rex is published by Kawabe & Hattori (2021).[199]

- A study attempting to determine bite force of a juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex, based on mechanical tests designed to replicate bite marks attributed to juvenile specimens of this species, is published by Peterson, Tseng & Brink (2021).[200]

- A study on the taphonomic and geochemical history of the Tyrannosaurus rex specimen MOR 1125 is published by Ullmann et al. (2021).[201]

- A study on the anatomy of the postcranial skeleton and on the phylogenetic relationships of Pelecanimimus polyodon is published by Cuesta et al. (2021), who name a new clade Macrocheiriformes, defined as Pelecanimimus and all derived ornithomimosaurs.[202]

- New ornithomimid fossil material, providing new information on the distal tarsal morphology in ornithomimids, is described from the Campanian Kaiparowits Formation (Utah, United States) by Nottrodt & Farke (2021).[203]

- A study on pelvic musculature in non-avian maniraptorans is published by Rhodes, Henderson & Currie (2021).[204]

- A study on the neuroanatomy of a new alvarezsauroid skeleton in the collection of the Henan Geological Museum (China) is published by Agnolín et al. (2021).[205]

- A study on the skeletal anatomy, probable musculature and likely function of tails of alvarezsaurian theropods is published by Meso et al. (2021).[206]

- A study on growth strategies and body miniaturization in the evolutionary history of alvarezsauroid theropods is published by Qin et al. (2021).[207]

- A study on the osteology of Fukuivenator paradoxus is published by Hattori et al. (2021), who described previously undescribed elements and reinterpret this genus as a basal therizinosaur.[208]

- A study on the anatomy of the postcranial skeleton of Beipiaosaurus inexpectus is published by Liao et al. (2021).[209]

- Reevaluation of putative blood cells preserved in the holotype specimen of Beipiaosaurus inexpectus is published by Korneisel et al. (2021), who interpret putative blood cells as more likely to be diagenetic structures.[210]

- Reconstructions of the muscular system of the hindlimb, forelimb and the shoulder girdle of Nothronychus are presented by Smith (2021).[211][212]

- Zheng et al. (2021) study cellular and nuclear preservation in femoral articular cartilage of a specimen of Caudipteryx from the Yixian Formation (China).[213]

- Partial skeleton of Elmisaurus rarus, preserving elements overlapping with known fossil material of Nomingia gobiensis, is described from the Upper Cretaceous Nemegt Formation (Mongolia) by Funston et al. (2021), who interpret this specimen as indicating that N. gobiensis is likely a junior synonym of E. rarus.[214]

- A study on the body mass of Anzu wyliei is published by Atkins-Weltman, Snively & O'Connor (2021).[215]

- A caenagnathid metatarsal is described from the Campanian Mesaverde Formation (Wyoming, United States; representing the first record of a caenagnathid from this formation) by Yun & Funston (2021), who evaluate the implications of this specimen for the knowledge whether reported differences in metatarsal morphology between "Macrophalangia" and Chirostenotes were merely allometric in nature, or whether they might represent phylogenetically informative variation.[216]

- An exceptionally preserved, articulated oviraptorid embryo, found inside an elongatoolithid egg in a posture previously unrecognized in a non-avian dinosaur but sharing aspects of bird-like tucking postures, is described from the Upper Cretaceous Hekou Formation (China) by Xing et al. (2021);[217] however, the conclusions of the authors are subsequently contested by Deeming & Kundrát (2022), who argue that this specimen was not close to hatching, and that the positioning of its head relative to its body cannot bear any relationship to hatching position of this animal.[218]

- Cau et al. (2021) report the identification of additional elements of the pectoral apparatus of the holotype specimen of Halszkaraptor escuilliei, including the furcula, and evaluate its implications for the knowledge of the evolution of the avian furcula.[219]

- A study on the anatomy of the skeleton of Unenlagia comahuensis is published by Novas et al. (2021).[220]

- A study on the vertebral pneumaticity in Unenlagia comahuensis is published by Gianechini & Zurriaguz (2021).[221]

- Description of a new troodontid specimen from the Upper Cretaceous Wulansuhai Formation (China), and a study on the phylogenetic relationships and evolutionary history of the Late Cretaceous troodontids, is published by Wang et al. (2021).[222]

- A unique troodontid nest is described by Maipig et al. (2021), preserving a unique spiral pattern of eggs embedded vertically into substrate.[223]

- Multi-individual aggregates of mammal skeletons are described from the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation (Montana, United States) by Freimuth et al. (2021), who interpret these aggregates as the oldest known mammal-bearing regurgitalites, probably produced by Troodon formosus.[224]

- A study on the anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Borogovia gracilicrus is published by Cau & Madzia (2021).[225]

- Brown, Tanke & Hone (2021) describe a hadrosaurid bone from the Campanian Dinosaur Park Formation (Alberta, Canada) preserved with bite marks produced by a small- to medium-sized theropod dinosaur, deviating from the majority of known theropod tooth marks and indicative of a behavior similar to mammalian gnawing.[226]

- Revision of the biodiversity of theropods from the Dinosaur Park Formation is published by Cullen et al. (2021).[227]

- Exquisitely preserved, ornamented partial eggs with theropod affinities, representing some of the smallest Mesozoic eggs reported to date, are described from the Campanian Kaiparowits Formation (Utah, United States) by Oser et al. (2021), who name a new ootaxon Stillatuberoolithus storrsi.[228]

Sauropodomorphs

- Review of the diversity and composition of South American sauropodomorph faunas throughout the Late Triassic is published by Pol et al. (2021).[229]

- A study on the evolution of the olfactory system in sauropodomorph dinosaurs, as indicated by the ratio between the size of the olfactory bulbs and cerebral hemispheres in sauropodomorph endocasts, is published by Müller (2021).[230]

- A study on the timing of the earliest occurrence of Triassic sauropodomorphs in their northernmost range (Fleming Fjord Formation, Greenland), and on possible relationship between climate changes and early sauropodomorph dispersal to the temperate belt of the Northern Hemisphere, is published by Kent & Clemmensen (2021).[231]

- Probable tracks of large sauropodomorphs dinosaurs, potentially representing the largest known tracks belonging to the ichnogenus Eosauropus reported to date, are described from the Upper Triassic (likely Rhaetian) Blue Anchor Formation (Penarth, south Wales, United Kingdom) by Falkingham et al. (2021).[232]

- A study on the evolution of the morphological diversity of sauropodomorph dinosaurs is published by Apaldetti et al. (2021).[233]

- New skull material of Plateosaurus, including the first two juvenile skulls of members of this genus, is described from the locality of Frick (Switzerland) by Lallensack et al. (2021), who attempt to determine whether the locality of Frick and German localities of Trossingen and Halberstadt contain specimens of Plateosaurus belonging to a single species.[234]

- A study on the skeletal growth during the ontogeny in Massospondylus carinatus is published by Chapelle, Botha & Choiniere (2021).[235]

- A study on the age of the fossil material of Yunnanosaurus youngi is published by Ren et al. (2021).[236]

- A study on the cranial anatomy of Anchisaurus polyzelus and the development of cranial characters in sauropodomorph ontogeny is published by Fabbri et al. (2021)[237]

- An assemblage including over 100 eggs and skeletal specimens of 80 specimens of Mussaurus patagonicus, ranging from embryos to fully-grown adults, is described from the Laguna Colorada Formation (Argentina) by Pol et al. (2021), who assign an Early Jurassic (Sinemurian) maximum age for the Mussaurus bearing sediments, and interpret this assemblage as likely evidence of colonial nesting habits, presence of social cohesion throughout the different stages of the lifespan, and age-based social partitioning within a herd structure in Mussaurus.[238]

- An extensive Late Jurassic sauropod tracksite, preserving the longest continuous sequence of sauropod pes prints reported to date and representing a rare record of a >180° turn made by the sauropod trackmaker to completely change direction and cross its own trackway, is described from a high altitude locality near Ouray (Colorado, United States) by Goodell et al. (2021).[239]

- A study on the anatomy of the axial skeleton of Bagualia alba is published by Gomez, Carballido & Pol (2021).[240]

- New fossil material of Shunosaurus, providing new information on the development of the skeleton of this sauropod during its ontogeny, is described from the Middle Jurassic Shaximiao Formation (China) by Ma et al. (2021).[241]

- A study on the skeletal anatomy of the holotype of Patagosaurus fariasi is published by Holwerda, Rauhut & Pol (2021).[242]

- A new specimen of Haplocanthosaurus with expanded neural canals is described by Wedel et al. (2021).[243]

- A study on the anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Amphicoelias altus is published by Mannion, Tschopp & Whitlock (2021).[244]

- The paleohistology of two dicraeosaurids from the La Amarga Formation (Argentina) is studied by Winholdz and Cerda (2021), who find that the holotype specimen of Amargatitanis macni belonged to a more mature individual than the holotype of Amargasaurus cazaui.[245]

- Fossilized skin of a juvenile member of the genus Diplodocus, providing evidence of new scale shapes and patterns never before seen in diplodocids, is described from the Mother's Day Quarry (Bighorn Basin, Montana, United States) by Gallagher, Poole & Schein (2021).[246]

- A study on the anatomy of the braincase of a diplodocid sauropod (possibly Leinkupal laticauda) from the Lower Cretaceous Bajada Colorada Formation (Argentina) is published by Garderes et al. (2021; final version published in 2022).[247]

- Redescription of the anatomy of the braincase of Limaysaurus tessonei is published by Paulina-Carabajal & Calvo (2021).[248]

- A description of well preserved fossil material of Camarasaurus, including an articulated, nearly-complete skull, and an analysis of variability within the genus based on cranial allometry trends is published by Woodruff et al. (2021).[249]

- Partial sauropod maxilla, possibly belonging to a brachiosaurid, is described from the Cretaceous (Albian–Cenomanian) Longjing Formation (northeast China) by Liao et al. (2021).[250]

- Sauropod tracks probably produced by non-titanosaurian titanosauriforms are described from the Rupelo Formation (Spain) by Torcida Fernández-Baldor et al. (2021), who evaluate the paleoenvironmental and paleoecological implications of this finding, and name a new ichnotaxon Iniestapodus burgensis.[251]

- A study on tooth replacement rates in early somphospondylans, as indicated by data from a dentary from the Lower Cretaceous (Aptian–Albian) Haoling Formation (China), is published by Chang et al. (2021).[252]

- A study aiming to determine whether titanosaur osteoderms could act as defensive structures is published by Silva Junior et al. (2021; final version published in 2022).[253]

- Description of the anatomy of the referred specimen of Diamantinasaurus matildae and a study on the phylogenetic relationships of this species is published by Poropat et al. (2021), who name a new clade Diamantinasauria, which includes it alongside Savannasaurus and Sarmientosaurus.[254]

- Fossil material of a giant titanosaur sauropod, distinct from Andesaurus and probably exceeding Patagotitan in size, is described from the Cenomanian Candeleros Formation (Argentina) by Otero et al. (2021).[255]

- Revision of known fossil material of Pellegrinisaurus powelli and a study on the skeletal anatomy, bone histology and phylogenetic relationships of this sauropod are published by Cerda et al. (2021).[256]

- New titanosaur remains, possibly belonging to a member of Colossosauria distinct from previously known taxa, are described from the Upper Cretaceous Portezuelo Formation (Argentina) by Bellardini et al. (2021).[257]

- A study on the anatomy of the axial skeleton of Rinconsaurus caudamirus is published by Pérez Moreno et al. (2021).[258]

- A study on the composition of several gastroliths from the Morrison are published by Malone, Strasser, Malone, D'Emic, Brown, and Craddock, who point to the differences between them and the surrounding rock and similarities to another site 1,000 km eastwards to suggest evidence of migration in sauropod dinosaurs.[259]

- Description of new fossil material and a study on the phylogenetic relationships of Tengrisaurus starkovi is published by Averianov, Sizov & Skutschas (2021).[260]

- Aureliano et al. (2021) report preservation of histological structure related to an avian-like air sac system in a vertebra of a saltasaurid titanosaur from the Upper Cretaceous São José do Rio Preto Formation (Bauru Group, Brazil).[261]

- Evidence of the preservation of nitrogen-bearing organic molecules (identified as proteinaceous moieties) in titanosaur eggshell from the Maastrichtian Lameta Formation (India) is presented by Dhiman et al. (2021).[262]

- A study on the stable isotope compositions of titanosaurian eggshells, bone and an associated tooth sampled in three Late Cretaceous nesting sites from La Rioja Province (Argentina), evaluating their implications for the knowledge of the body temperature of titanosaur sauropods, their diet, and the environmental conditions they needed reproduce, is published by Leuzinger et al. (2021).[263]

Ornithischians

- Revision of the phylogenetic nomenclature of ornithischian dinosaurs is published by Madzia et al. (2021), who name new clades Corythosauria, Euceratopsia, Saphornithischia, Panoplosaurini and Struthiosaurini.[264]

- New fossil material of ornithischians, including remains of basal euiguanodontian and hadrosaurid ornithopods and the southernmost record of ankylosaurs from South America reported to date, is described from the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian–Maastrichtian) Chorrillo Formation (Argentina) by Rozadilla et al. (2021), who evaluate the implications of these fossils for the knowledge of the evolutionary history of ankylosaurs and hadrosaurids in South America.[265]

- A study on the Late Cretaceous ornithischian assemblage of western North America, aiming to examine the prediction that juveniles of large herbivores competitively excluded small herbivorous species, and that the small species that were able to coexist alongside the juveniles of larger species did so because of their unique occupation of niche space, is published by Wyenberg-Henzler, Patterson & Mallon (2021).[266]

- Radermacher et al. (2021) describe a new, fully articulated skeleton of Heterodontosaurus tucki, preserving a suite of novel postcranial features unknown in any other ornithischian dinosaur, and evaluate the implications of this specimen for the knowledge of the evolution of ornithischian respiratory biology.[267]

Thyreophorans

- A study on the skeletal anatomy and bone histology of Scutellosaurus lawleri, providing new data on the morphology and new life reconstruction for this dinosaur, is published by Breeden et al. (2021).[268]

- A stegosaurian humerus is described from the Cañadón Calcáreo Formation (Argentina) by Rauhut, Carballido & Pol (2021), extending the fossil record of Stegosauria to the Late Jurassic of South America.[269]

- A study on the morphology, macro- and microwear, and microanatomy of the stegosaur teeth from the Teete locality (Lower Cretaceous Batylykh Formation; Sakha, Russia), evaluating their implications for the knowledge of the paleobiology of the Teete stegosaur, is published by Skutschas et al. (2021).[270]

- The smallest stegosaur track reported to date, co-occurring with the tracks of larger individuals, is described from the Lower Cretaceous Tugulu Group (Xinjiang, China) by Xing et al. (2021).[271]

- The type locality and holotype of Dracopelta zbyszewskii are reinterpreted by Russo & Mateus (2021), who also chronicle the history of the holotype.[272]

- Riguetti et al. (2021) describe nodosaurid tracks from the Maastrichtian El Molino Formation (Bolivia), increasing known diversity of ankylosaur tracks from South America.[273]

- Several fragmentary skulls and skull elements of Hungarosaurus, providing new information on the morphological diversity, development and possible function of the ornamentation of nodosaurid skulls, are described by Ősi et al. (2021).[274]

- A study on dental microwear and jaw movement of Jinyunpelta, and on its implications for the knowledge of the evolution of the feeding mechanism of ankylosaurids, is published by Kubo et al. (2021).[275]

- Articulated postcranial skeleton of an indeterminate ankylosaurid dinosaur is described from the Barun Goyot Formation (Mongolia) by Park et al. (2021), who interpret this specimen as indicating that Asian ankylosaurids evolved rigid bodies with a reduced number of pedal phalanges, as well as the existence of at least two forms of flank armor in ankylosaurids, and discuss possible adaptations for digging in ankylosaurids.[276]

Cerapods

- A study on the skeletal anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Haya griva is published by Barta & Norell (2021).[277]

- Duncan et al. (2021) describe ornithopod jaws from the Lower Cretaceous Eumeralla Formation (Australia), and evaluate the implications of these fossils for the knowledge of the diversity of Early Cretaceous ornithopods from this area.[278]

- A study on the anatomy of the manus of Tenontosaurus tilletti is published by Hunt, Cifelli & Davies (2021).[279]

- A study on the accumulated remains of Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki from the Upper Jurassic Tendaguru Formation (Tanzania) is published by Hübner et al. (2021), who interpret two large bonebeds as most likely resulting from two independent catastrophic mortality events.[280]

- A study on the anatomy of the braincase and probable brain size in Proa valdearinnoensis is published by Knoll et al. (2021).[281]

- A specimen of Gobihadros mongoliensis preserving features of cessation of growth, indicating that it reached the terminal size and advanced age, is described from the Upper Cretaceous Bayan Shireh Formation (Mongolia) by Słowiak et al. (2021), who diagnose this specimen as affected by calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease, making it the first known non-avian dinosaur specimen affected with this disease.[282]

- Redescription of the anatomy and a study on the phylogenetic relationships of Lophorhothon atopus, based on data from the holotype and from a new specimen, is published by Gates & Lamb (2021).[283]

- A study on the anatomy of the postcranial skeleton of Tanius sinensis is published by Borinder et al. (2021).[284]

- Description of new fossil material of Tethyshadros insularis from the Villaggio del Pescatore fossil site (Italy), a study on the age of this site and on the phylogenetic affinities of T. insularis, and a reevaluation of claims about the evolution of insular dwarfism in Late Cretaceous hadrosauroids, is published by Chiarenza et al. (2021).[285]

- Description of new fossil material of hadrosaurids from the Upper Cretaceous Lago Colhué Huapí Formation (Argentina), and a study on the environment inhabited by these hadrosaurids and on the influence of paleoenvironmental conditions on South American hadrosaurid distribution, is published by Ibiricu et al. (2021).[286]

- Holland et al. (2021) describe an assemblage of late juvenile hadrosaurid specimens from the Spring Creek Bonebed (Alberta, Canada), representing the first record of lambeosaurines from the Wapiti Formation and possibly indicating that age segregation was a life history strategy among hadrosaurids.[287]

- Revision of the type material and a study on the phylogenetic affinities of Latirhinus uitstlani is published by Ramírez-Velasco, Espinosa-Arrubarrena & Alvarado-Ortega (2021);[288] a study on the taphonomy of the skeletal elements in the holotype of L. uitstlani designated by the aforementioned authors, on the skeletal composition of the holotype, on the diagnostic utility of the characters used by Ramírez-Velasco, Espinosa-Arrubarrena & Alvarado-Ortega (2021) for referring other specimens to different hadrosaurid clades, and on the phylogenetic affinities of L. uitstlani is subsequently published by Serrano-Brañas & Prieto-Márquez (2021).[289]

- Redescription of Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus, based on data from a new skull from the Campanian Fruitland Formation (New Mexico, United States), is published by Gates, Evans & Sertich (2021).[290]

- A study on the injuries of the holotype specimen of Bonapartesaurus rionegrensis, and on their implications for the knowledge of its paleobiology, is published by Cruzado-Caballero et al. (2021).[291]

- Five new partial skulls of Maiasaura peeblesorum, providing information on the acquisition of the crest and changes to the surrounding cranial elements during the ontogeny of this dinosaur, are described from the Campanian Two Medicine Formation (Montana, United States) by McFeeters, Evans & Maddin (2021).[292]

- A study aiming to determine the taxonomic validity of the species Sphaerotholus buchholtzae and S. edmontonensis is published by Woodruff et al. (2021).[293]

- Vinther, Nicholls & Kelly (2021) describe the first fossil cloacal vent in an exceptionally preserved non-avian dinosaur specimen (a specimen of Psittacosaurus from the Early Cretaceous Jehol deposits of Liaoning, China).[294]

- A study on jaws and teeth of juvenile and adult specimens of Psittacosaurus lujiatunensis, aiming to determine whether this dinosaur underwent a dietary shift during its ontogeny, is published by Landi et al. (2021).[295]

- A study on the ontogenetic changes in the femoral histology of Psittacosaurus sibiricus is published by Skutschas et al. (2021).[296]

- A study on the whole-skull shape in a large sample of specimens of Protoceratops andrewsi is published by Knapp, Knell & Hone (2021), who argue that the frill of P. andrewsi shows several characteristics consistent with a socio-sexual trait.[297]

- A study on the anatomy of a specimen of Protoceratops andrewsi from the Bayan Zag locality (Djadochta Formation, Mongolia), interpreted as most likely to be a large immature female, and on its implications for explanation of the polymorphism in the fossil material attributed to P. andrewsi and for diagnosing P. andrewsi from vertebrae considering the age and sex of compared specimens, is published by Tereshchenko (2021).[298]

- Description of a skull of a subadult specimen of Einiosaurus procurvicornis from the Two Medicine Formation (Montana, United States), and a study on the implications of this specimen for the knowledge of the sequence and timing of development of primary cranial ornaments in eucentrosauran ceratopsids, is published by Wilson & Scannella (2021).[299]

- A study on the dentition of Stegoceras validum and Thescelosaurus neglectus, and on its implications for the knowledge of the feeding behavior of these ornithischians, is published by Hudgins, Currie & Sullivan (2021).[300]

- A study on the biodiversity patterns of Late Cretaceous hadrosaurids and ceratopsids from the western interior of North America, evaluating whether the fossil record provides evidence of faunal provinciality of these dinosaurs, is published by Maidment et al. (2021).[301]

Birds

New Bird taxa

| Name | Novelty | Status | Authors | Age | Type locality | Country | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Tennyson & Tomotani |

A kiwi. |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Mather et al. |

Late Oligocene |

A member of the family Accipitridae. The type species is A. sylvestris. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Mayr |

A member of the family Archaeotrogonidae. The type species is A. anglicus. |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Campbell & Bocheński |

Late Pleistocene |

A woodpecker. The type species is B. minimus. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Campbell & Bocheński |

Late Pleistocene |

La Brea Tar Pits |

A woodpecker. The type species is B. garretti. |

|||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

In press |

O'Connor et al. |

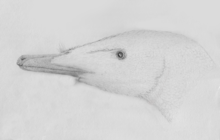

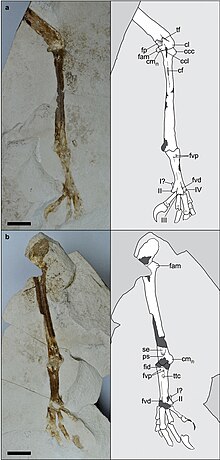

Early Cretaceous |

An early member of Ornithuromorpha. The type species is B. zhangi. The generic name "Brachydontornis" is also used by the authors. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

In press |

Li et al. |

Early Cretaceous |

A member of Enantiornithes. The type species is B. macrohyoideus. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Zelenkov |

Late Paleocene-early Eocene |

Naran-Bulak Formation |

A member of the family Presbyornithidae. The type species is B. anatoides. |

|||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Zelenkov |

Early Eocene |

A member of Gruiformes showing the greatest similarity with modern limpkin. The type species is B. aramoides. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Zelenkov |

Early Eocene |

A member of Galliformes showing morphological similarities with Argillipes aurorum and members of the family Quercymegapodiidae. The type species is B. magnus. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Zelenkov |

Early Eocene |

Bird described on the basis of a coracoid, morphologically intermediate between those of Walbeckornis and members of the family Messelornithidae. The type species is B. walbeckornithoides. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Zelenkov |

Early Eocene |

A small galliform bird showing morphological similarities with members of the families Quercymegapodiidae and Gallinuloididae. The type species is B. transitoria. |

||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Degrange et al. |

Chapadmalal Formation |

A large buzzard, a species of Buteo. |

||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Suárez & Olson |

Quaternary (probably late Pleistocene) |

A species of Buteogallus. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

In press |

Bocheński et al. |

A passerine, an early member of Suboscines. The type species is C. nargizia. |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

El Adli et al. |

A pelican. The type species is E. aegyptiacus. |

|||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Clark & O'Connor |

A member of Enantiornithes. The type species is F. prehendens. |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Salvador, Anderson & Tennyson |

Holocene |

A species of Gallirallus. |

||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Giovanardi, Ksepka & Thomas |

Glen Massey Formation |

A penguin, a species of Kairuku. |

||||

|

Comb nov |

valid |

A plotopterid. |

| |||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Carvalho et al. |

Early Cretaceous (Aptian) |

An early member of Ornithuromorpha. The type species is K. mater. |

||||

|

Sp. nov |

In press |

Worthy et al. |

Miocene |

Bannockburn Formation |

A member of the family Anatidae from the St Bathans fauna. |

|||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Jadwiszczak, Reguero & Mörs |

Eocene (Priabonian) |

Submeseta Formation |

A small-sized penguin. The type species is M. sobrali. |

|||

|

Sp. nov |

In press |

Zelenkov & González |

Late Pleistocene |

A species of Margarobyas. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

In press |

O'Connor et al. |

Early Cretaceous |

Xiagou Formation |

An early member of Ornithuromorpha. The type species is M. ductrix. |

|||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Campbell & Bocheński |

Late Pleistocene |

La Brea Tar Pits |

A woodpecker, a species of Melanerpes. |

|||

| Neimengornis[323] | Gen. et sp. nov | Wang et al. | Early Cretaceous | Jiufotang Formation | A member of Jeholornithiformes. The type species is N. rectusmim. | |||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Louchart & Duhamel |

Early Oligocene |

A member of Gruoidea related to the limpkin and cranes. The type species is P. tourmenti. |

||||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Mayr |

Early Eocene |

A relative of Psittacopes, Pumiliornis and Morsoravis. The type species is P. bergdahli. |

||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Boev |

Early Pleistocene |

A species of Pica. |

||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Tennyson & Tomotani |

A species of Procellaria. |

|||||

|

Sp. nov |

Valid |

Mayr |

Eocene (Ypresian) |

London Clay |

A species of the messelasturid Tynskya. |

|||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Degrange et al. |

Eocene (Ypresian) |

A member of the stem group of Coracii. The type species is U. tambussiae. |

| ||||

| Vinchinavis[330] | Gen. et sp. nov | Valid | Tambussi et al. | Miocene | Toro Negro | A large eagle. The type species is V. paka. Announced in 2020; the final version of the article naming it was published in 2021. | ||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

Valid |

Wang et al. |

Early Cretaceous |

A member of Enantiornithes belonging to the family Pengornithidae. The type species is Y. kompsosoura. |

| |||

|

Gen. et sp. nov |

In press |

Xu et al. |

Late Cretaceous |

A member of Enantiornithes. The type species is Y. junchangi. |

Research

- The study on the phylogenetic relationships and powered flight potential of early birds and their closest relatives published by Pei et al. (2020), arguing that the potential for powered flight evolved at least three times (once in birds and twice in dromaeosaurids),[333] is criticized by Serrano & Chiappe (2021).[334][335]

- Review of the most relevant events in limb evolution across the dinosaur-bird transition and the origins of bird flight is published by Nebreda, Hernández Fernández & Marugán-Lobón (2021).[336]

- A study on the diversification rates of birds throughout their evolutionary history is published by Yu, Zhang & Xu (2021).[337]

- A study on the evolution of the brain in birds, based on data from extant and recently extinct birds, Archaeopteryx and non-avian coelurosaurian theropods, is published by Watanabe et al. (2021).[338]

- A study aiming to infer the diets of the last common ancestor of living birds, based on data from digestive system-related genes, is published by Wu (2021), who interprets his findings as indicative of a diet shift from carnivory to herbivory at the non-avian archosaur-to-bird transition, and evaluates possible implications of this diet shift for the evolution of early birds.[339]

- Review of methods used to determine diet in modern and fossil birds, evaluating their utility for determination of diets of Mesozoic birds, is published by Miller & Pittman (2021).[340]

- A study on patterns and modes of the evolution of skeletal morphology and limb proportions in Mesozoic birds is published by Wang et al. (2021).[341]

- A study on the variation in tooth crown shape of Mesozoic birds, and its implications for the knowledge of their diets, is published by Zhou et al. (2021).[342]

- A study on the impact of tooth loss on the diversification of Mesozoic birds is published by Brocklehurst & Field (2021), who find no evidence for a link between toothlessness and accelerated cladogenesis, as well as no evidence for models whereby acquisitions of toothlessness among Mesozoic birds were driven by an overarching selective trend.[343]

- Review of the variability of bone histology in basal members of Avialae is published by Monfroy & Kundrát (2021).[344]

- A study on the ecomorphology of extant and fossil birds, aiming to determine whether the ecologies of Mesozoic birds can be inferred on the basis of data from measurements of their forelimbs and hindlimbs, is published by Bell et al. (2021).[345]

- The study published by Kaye, Pittman & Wahl (2020), reporting evidence interpreted by the authors as indicative of the feather moulting in the Thermopolis specimen of Archaeopteryx,[346] is criticized by Kiat et al. (2021).[347][348]

- A study on the cellular preservation in the calcified cartilage of specimens of Confuciusornis and Yanornis from the Early Cretaceous Jehol biota (northeast China) is published by Bailleul & Zhou (2021).[349]

- A study on the nanostructures of the melanosomes sampled from a specimen of Eoconfuciusornis from the Lower Cretaceous Huajiying Formation (China) is published by Pan et al. (2021), who interpret their findings as evidence of brilliant iridescent plumage color in Eoconfuciusornis.[350]

- A study on the histology of the scapulocoracoid in Confuciusornis is published by Wu et al. (2021).[351]

- New enantiornithine specimen with a well-preserved skull, retaining the plesiomorphic dinosaurian palate and diapsid temporal configurations indicative of an akinetic skull, is described from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation (China) by Wang et al. (2021), who evaluate the implications of this specimen for the knowledge of the evolution of bird skulls.[352]