Douglas Coupland: Difference between revisions

| Line 317: | Line 317: | ||

[[Category:Emily Carr University of Art and Design alumni]] |

[[Category:Emily Carr University of Art and Design alumni]] |

||

[[Category:Canadian LGBTQ dramatists and playwrights]] |

[[Category:Canadian LGBTQ dramatists and playwrights]] |

||

[[Category:Canadian |

[[Category:Canadian LGBTQ novelists]] |

||

[[Category:20th-century Canadian sculptors]] |

[[Category:20th-century Canadian sculptors]] |

||

[[Category:Canadian male sculptors]] |

[[Category:Canadian male sculptors]] |

||

Revision as of 03:01, 25 September 2024

Douglas Coupland | |

|---|---|

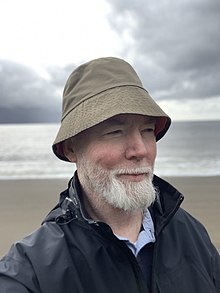

Douglas Coupland in Haida Gwaii (2022) | |

| Born | December 30, 1961 CFB Baden–Soellingen, West Germany |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Literary movement | |

| Notable works |

|

| Website | |

| coupland | |

Douglas Coupland[a] OC OBC RCA (born 30 December 1961) is a Canadian novelist, designer, and visual artist. His first novel, the 1991 international bestseller Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture, popularized the terms Generation X and McJob. He has published 13 novels, two collections of short stories, seven non-fiction books, and a number of dramatic works and screenplays for film and television. He is a columnist for the Financial Times,[3] as well as a frequent contributor to The New York Times, e-flux journal, DIS Magazine, and Vice.[4] His art exhibits include Everywhere Is Anywhere Is Anything Is Everything, which was exhibited at the Vancouver Art Gallery,[5] and the Royal Ontario Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art, now the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto Canada,[6] and Bit Rot at Rotterdam's Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art,[7] as well as the Villa Stuck.[8]

Coupland is an Officer of the Order of Canada, and a member of the Order of British Columbia.[9][10] He published his thirteenth novel Worst. Person. Ever. in 2012. He also released an updated version of City of Glass and the biography Extraordinary Canadians: Marshall McLuhan.[11] He was the presenter of the 2010 Massey Lectures, with a companion novel to the lectures published by House of Anansi Press: Player One – What Is to Become of Us: A Novel in Five Hours. Coupland has been long-listed twice for the Scotiabank Giller Prize in 2006 and 2010, was a finalist for the Writers' Trust Fiction Prize in 2009, and was nominated for the Hubert Evans Non-Fiction Prize in 2011 for Extraordinary Canadians: Marshall McLuhan.[12][13][14]

Early life

Coupland was born on December 30, 1961, at RCAF Station Baden-Soellingen in West Germany, the second of four sons of Douglas Charles Thomas Coupland, a medical officer in the Royal Canadian Air Force, and C. Janet Coupland, a graduate in comparative religion from McGill University. In 1965, the Coupland family moved to West Vancouver, where Coupland's father opened a private family medical practice at the completion of his military tour.

Coupland describes his upbringing as producing a "blank slate".[15] "My mother comes from a sour-faced family of preachers who from the 19th century to well into the 20th scoured the prairies thumping Bibles. Her parents tried to get away from that but unwittingly transmitted their values to my mother. My father's family weren't that different."[15]

Graduating from Sentinel Secondary School in West Vancouver in 1979, Coupland went to McGill University with the intention of (like his father) studying the sciences, specifically physics.[16] Coupland left McGill at the year's end and returned to Vancouver to attend art school.

At the Emily Carr College of Art and Design on Granville Island in Vancouver, in Coupland's words, "I ... had the best four years of my life. It's the one place I've felt truly, totally at home. It was a magic era between the hippies and the PC goon squads. Everyone talked to everyone and you could ask anybody anything."[17] Coupland graduated from Emily Carr in 1984 with a focus on sculpture, and moved on to study at the European Design Institute in Milan, Italy and the Hokkaido College of Art & Design in Sapporo, Japan.[17] He also completed courses in business science, fine art, and industrial design in Japan in 1986.

Established as a designer working in Tokyo, Coupland developed a skin condition brought on by Tokyo's summer climate, and returned to Vancouver.[17] Before leaving Japan, Coupland had sent a postcard ahead to a friend in Vancouver. The friend's husband, a magazine editor, read the postcard and offered Coupland a job writing for the magazine.[17] Coupland began writing for magazines as a means of paying his studio bills.[18] Reflecting on his becoming a writer, Coupland has admitted that he became one "By accident. I never wanted to be a writer. Now that I do it, there's nothing else I'd rather do."[19] He has stated that he has not been employed since 1988.[20]

Literary works

Generation X

From 1989 to 1990, Coupland lived in the Mojave Desert working on a handbook about the birth cohort that followed the baby boom.[21] He received a $22,500 advance from St. Martin's Press to write the nonfiction handbook. Instead, Coupland wrote the novel Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture.[22] It was rejected in Canada before being accepted by an American publishing house in 1991.[23] Reflecting on the writing of his debut novel years later, Coupland said, "I remember spending my days almost dizzy with loneliness and feeling like I'd sold the family cow for three beans. I suppose it was this crippling loneliness that gave Gen X its bite. I was trying to imagine a life for myself on paper that certainly wasn't happening in reality."[24]

Not an instant success, the novel steadily increased in sales, eventually attracting a following behind its core idea of "Generation X". Over his own protestations, Coupland was dubbed the spokesperson for a generation,[25] stating in 2006 "I was just doing what I do and people sort of stuck that on to me. It's not like I spend my days thinking that way."[26] The terms Generation X and McJob, used by Coupland in the novel, ultimately entered the vernacular.[27][28]

Shampoo Planet through Life After God

Shampoo Planet was published by Pocket Books in 1992. It focused on the generation after Generation X, the group called "Global Teens" in his first novel and now generally labeled Generation Y (or Millennials).[22] Coupland permanently moved back to Vancouver soon after the novel was published. He had spent his "twenties scouring the globe thinking there had to be a better city out there, until it dawned on [him] that Vancouver is the best one going".[29] He wrote a collection of small books, which together were compiled, after the advice of his publisher, into the book Life After God. This collection of short stories, with its focus on spirituality, initially provoked polarized reaction before eventually revealing itself as a bellwether text for the avant-garde sensibility identified by Ferdinand Mount as "Christian post-Christian".[30]

Microserfs through All Families Are Psychotic

In 1994, Coupland was working for the newly formed magazine Wired. While there, Coupland wrote a short story about the life of the employees at Microsoft Corporation. This short work provided the inspiration for a novel, Microserfs. To research the culture that the novel depicted, Coupland had moved to Palo Alto, California and immersed himself in Silicon Valley life.[31]

Coupland followed Microserfs with his first collection of non-fiction pieces, in 1996. Polaroids from the Dead is a manifold of stories and essays on diverse topics, including: Grateful Dead concerts; Harolding; Kurt Cobain's death; the visiting of a German reporter; and a comprehensive essay on Brentwood, California, written at the time of the O. J. Simpson murder case and the anniversary of Marilyn Monroe's death.

The same year, Coupland toured Europe to promote Microserfs, but the high workload brought on fatigue and mental strain.[32][33] He reportedly incorporated his experience with depression during this period into his novel, Girlfriend in a Coma. Coupland noted that this was his last novel to be "... written as a young person, the last constructed from notebooks full of intricate observations".[34]

In 1998, Coupland contributed the short story "Fire at the Ativan Factory" to the collection Disco 2000, and the same year, wrote the liner notes for Saint Etienne's album Good Humor. In 2000, he published the novel Miss Wyoming.

Coupland then published his photographic paean to Vancouver: City of Glass. The book incorporates sections from Life After God and Polaroids from the Dead into a visual narrative, formed from photographs of Vancouver locations and life supplemented by stock footage mined from local newspaper archives.

Coupland's novel All Families Are Psychotic tells the story of a dysfunctional family from Vancouver coming together to watch their daughter Sarah, an astronaut, launch into space.

Souvenir of Canada through Worst. Person. Ever.

The promotional rounds for All Families are Psychotic were underway when the September 11 attacks took place. In a play called September 10 performed later at Stratford-upon-Avon by the Royal Shakespeare Company, Coupland felt that this was the last day of the 1990s, and the new century had now truly begun.[35][36]

The first book that Coupland published after the September 11 attacks was Souvenir of Canada, which expanded his earlier City of Glass to incorporate the whole of Canada. There are two volumes in this series, which was conceived as an explanation to non-Canadians of uniquely Canadian things.

Coupland's book Hey Nostradamus! describes a fictitious high school shooting similar to the Columbine High School in 1999.[37] Coupland relocates the events to a school in North Vancouver, Canada.

Coupland followed Hey Nostradamus! with Eleanor Rigby. Similarly to the titular original written and sung by The Beatles, the novel examines loneliness.[38] The novel received some positive acclaim as a more mature work, a notable example being novelist Ali Smith's review of the book for the Guardian newspaper.[24]

Using the format of City of Glass and Souvenir of Canada, Coupland released a book for the Terry Fox Foundation titled Terry. It is a photographic look back on the life of Fox, the result of Coupland's exhaustive research through the Terry Fox archives, including thousands of emotional letters from Canadians written to Fox during his one-legged marathon across Canada on Highway 1.

The third work of fiction in this period, written concurrently with the non-fiction Terry,[39] is another re-envisioning of a previous book. jPod, billed as Microserfs for the Google generation, is his first Web 2.0 novel. The text of jPod recreates the experience of a novel read online on a notebook computer. jPod was a popular success, giving rise to a CBC Television series for which Coupland wrote the script. The series lasted one season before cancellation.

Coupland's The Gum Thief, followed jPod in 2007. The Gum Thief was Coupland's first foray into the standard epistolary novel format following the 'laptop diaries'/'blog' formats of Microserfs and jPod.

Coupland published Generation A in late 2009. In terms of style, Generation A "mirrors the structure of 1991's Generation X as it champions the act of reading and storytelling as one of the few defenses we still have against the constant bombardment of the senses in a digital world".[40] The novel takes place in the near future, after bees have become extinct, and focuses on five people from around the globe who are connected by being stung.

Coupland's contribution for the 2010 Massey Lectures, as opposed to a standard long essay, was 50,000 word novel entitled Player One – What Is to Become of Us: A Novel in Five Hours. Coupland wrote the novel as five hour-long lectures aired on CBC Radio from November 8 to 12, 2010.[41] According to Coupland, the novel "... presents a wide array of modes to view the mind, the soul, the body, the future, eternity, technology, and media" and is set "In a B-list Toronto airport hotel's cocktail lounge in August of 2010."[42]

The lecture/novel was published in its own right on October 7, 2010.[43] House of Anansi Press advance publicity for the novel stated that

Coupland's 2010 Massey Lecture is a real-time, five-hour story set in an airport cocktail lounge during a global disaster. Five disparate people are trapped inside: Karen, a single mother waiting for her online date; Rick, the down-on-his-luck airport lounge bartender; Luke, a pastor on the run; Rachel, a cool Hitchcock blonde incapable of true human contact; and finally a mysterious voice known as Player One. Slowly, each reveals the truth about themselves while the world as they know it comes to an end. In the tradition of Kurt Vonnegut and J. G. Ballard, Coupland explores the modern crises of time, human identity, society, religion, and the afterlife. The book asks as many questions as it answers, and readers will leave the story with no doubt that we are in a new phase of existence as a species – and that there is no turning back.[43]

On September 20, 2010, Player One was announced as part of the initial longlist for the 2010 Scotiabank Giller Prize literary award,[44][45][46] Coupland's second long-listing for the prize after being long-listed in 2006 with jPod.[47]

Coupland followed Player One with a second short story collection, this time in collaboration with the artist Graham Roumieu, entitled Highly Inappropriate Tales for Young People. The publisher described the book as "seven pants-peeingly funny stories featuring seven evil characters you can't help but love".[48]

Worst. Person. Ever. was released in Canada and the UK in October 2013, and in the US in April 2014.[49]

Awards and recognition

Coupland has been described as "... possibly the most gifted exegete of North American mass culture writing today."[50] and "one of the great satirists of consumerism".[51]

In 2015, he was made a member of France's Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.[52] In 2017, Coupland was awarded the 2017 Lieutenant Governor's Award for Literary Excellence.[53][54] Coupland was made a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 2007.[55][56] In 2013, he was made an Officer of the Order of Canada "for his contributions to our examination of the contemporary human condition as a novelist, cultural commentator and artist".[9] In 2014, Coupland was made a member of the Order of British Columbia.[10]

Coupland received an honorary Doctor of Letters from the Emily Carr University of Art and Design (2001),[57] an honorary Doctor of Letters from Simon Fraser University (2007),[58] an honorary degree from the University of British Columbia (2010),[59] an Honorary Doctor of Laws from Mount Allison University (2011),[60] and an honorary doctorate degree from OCAD University (2013).[61]

In 2010, the University of British Columbia announced that it had acquired Coupland's personal archives, the culmination of a project that began in 2002.[62] The archives, which Coupland plans to continue to add to in the future, currently consist of 122 boxes and features about 30 metres of textual materials,[63] including manuscripts, photos, visual art, fan mail, correspondence, press clippings, audio/visual material and more.[63] One of the most notable inclusions in the collection includes the first hand-written manuscript of ‘Generation X,' scrawled on loose-leaf notebook paper and strewn with margin notes.[62] In a statement issued on the UBC website Coupland said, "I am honoured that UBC has accepted my papers. I hope that within them, people in the future will find patterns and constellations that can’t be apparent to me or to anyone simply because they are there, and we are here...The donation process makes me feel old and yet young at the same time. I’m deeply grateful for UBC’s support and enthusiasm."[63] A new consignment of materials including "[...] everything from doodles and fan mail to a bejeweled hornet’s nest to a Styrofoam leg for the archive arrived in July 2012[...]" arrived for sorting in July 2012.[64] The sorting and categorisation of the new material was documented through the UBC School of Archival and Information Studies blog.[65]

Visual arts

In 2000, Coupland resumed a visual arts practice dormant since 1989. His is a post-medium practice that employs a variety of materials. A common theme in his work is a curiosity with the corrupting and seductive dimensions of pop culture and 20th century pop art, especially that of Andy Warhol. Another recurring theme is military imagery, the result of growing up in a military family at the height of the Cold War. He is represented by the Daniel Faria Gallery in Toronto. In June 2010 he announced his first efforts as a clothing designer by collaborating with Roots Canada on a collection that is a representation of classic Canadian icons. The Roots X Douglas Coupland collection was announced in The Globe and Mail and featured clothing, art installations, sculpture, custom designed art and retail spaces. In 2011, he began a series titled Slogans for the Twenty-first Century, catchphrases published on brightly coloured backgrounds that were first used as a promotional tool for an event at the Waldorf, a Vancouver nightclub.[66] This series was expanded in 2021 and titled Slogans for the Class of 2030 in collaboration with Google Arts & Culture. An algorithm was created by inputting Coupland's 30 years of written work that then created its own pithy statements.[67]

In 2004, the dormant Saarinen-designed TWA Flight Center (now Jetblue Terminal 5) at John F. Kennedy International Airport briefly hosted an art exhibition called Terminal 5,[68] curated by Rachel K. Ward[69] and featuring the work of 18 artists[70] including Coupland.

In September 2010, Coupland, working with Toronto's PLANT Architect, won the art and design contract for a new national monument in Ottawa. Canadian Fallen Firefighters Memorial was erected for the Canadian Fallen Firefighters Foundation, and completed in January, 2014.[71][72]

Other notable works are:

In October 2012, the 60-foot tall Infinite Tires was erected as part of Vancouver's public art program to accompany the opening of a Canadian Tire store. The construct was linked to the concept of Romanian artist Constantin Brâncuși's Infinite Column.[73]

In 2014, Coupland announced plans to construct in south Vancouver a gold-coloured replica of Stanley Park's Hollow Tree.[74] Golden Tree was unveiled on August 6, 2016[75][76]

In 2015, Coupland became Google's Artist in Residence at the Google Cultural Institute in Paris.[77]

Public works

Canada

Alberta

- Northern Lights, 2020, Telus Sky Building, Calgary[78]

British Columbia

- Golden Tree, 2016, Marine Drive and Cambie Street, Vancouver

- Bow Tie, 2015, Park Royal, West Vancouver

- Infinite Tire, 2012, SW Marine Drive and Ontario Street, Vancouver

- Terry Fox Memorial, 2011, Terry Fox Plaza, BC Place Stadium, Vancouver

- Digital Orca, 2009, Jack Poole Plaza, Vancouver

- Charm Bracelet, 2020, The Amazing Brentwood, Burnaby

Ontario

- Lone Pine Sunset, 2019, Parliament station, O-Train, Ottawa

- Four Seasons, 2014, Don Mills Road and Sheppard Avenue East, Toronto

- Canadian Fallen Firefighters Memorial, 2012, 220 Lett Street, Ottawa

- Group Portrait 1957, 2011, The Robert McLaughlin Gallery, Oshawa

- Super Nova, 2009, Shops at Don Mills, North York

- Monument to the War of 1812, 2008, Fleet and Bathurst streets, Toronto

- The Red Canoe, 2008, Canoe Landing Park, Toronto

- Heart-shaped Stone, 2008, Canoe Landing Park, Toronto

- Float Forms, 2007, Canoe Landing Park, Toronto

Museum exhibitions

In 2014, the Vancouver Art Gallery organized a major retrospective of Coupland's art, entitled everywhere is anywhere is anything is everything.[79][80] The Vancouver iteration of the show was captured on Google Street View.[81] In 2015, the exhibition was shown in Toronto in two venues: the Royal Ontario Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art (now the Museum of Contemporary Art, Toronto).[82] The monograph from the exhibition was published by Black Dog Publishing, London.[83]

Between 2015 and 2017, Bit Rot was exhibited. It is described as "A internationally traveling art exhibition, a catalogue accompanying that exhibition and a very large compendium of essays and fiction to be published in October 2016".[84] It was shown in Rotterdam at the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art from September 11, 2015, to January 3, 2016.[7] Bit Rot was then exhibited at the Villa Stuck in München from September 29, 2016, to January 8, 2017.[8]

In 2016, Assembling the Future was exhibited at The Manege in St. Petersburg, Russia. The exhibition was organized and curated by Marcello Dantas.[85][86]

Also in 2016, Coupland's works were exhibited in It's All Happening So Fast : A Counter-History of the Modern Canadian Environment at the Canadian Centre for Architecture.[87]

In 2018, Coupland collaborated with Ocean Wise to highlight ocean plastic pollution in Vortex, a major sculpture exhibition that was unveiled at Vancouver Aquarium in Vancouver, Canada on May 18. This year-long exhibition ran until April 30, 2019.[88][89]

On June 29, 2018, The National Portrait opened at the Ottawa Art Gallery in Ottawa, Ontario. This large-scale exhibition was made from hundreds of 3D-printed portraits which Coupland created from volunteers at Simons stores across Canada from July 2015 until April 2017. Each volunteer received a hand-sized version of their own 3D-printed bust. The exhibition ran until August 19, 2018.[90][91]

In addition to showing his own works in museum exhibitions, Coupland curated Super City for the Canadian Centre for Architecture in 2005;[92] further, he curated Welcome to the Age of You for the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto with Hans-Ulrich Obrist in 2019.

Select group exhibitions

- Beyond Words, The Dox Centre for Contemporary Art, Prague, 2023

- Art in the Age of Anxiety, Sharjah Art Foundation, 2020

- It's Urgent, LUMA Foundation, Arles, 2020

- IN FOCUS: Statements, Copenhagen Contemporary, 2020

- Electronic Superhighway, Whitechapel Gallery, London, 2017

- It's All Happening So Fast, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal, 2016

- The Heart Is a Deceitful Above All Things, HOME Contemporary Arts Centre, Manchester, 2015[93]

- The Fab Mind, 21 21 Design Sight, the Issey Miyake Foundation, Tokyo, 2014 [94]

- Do It, Ciclo (Cycle), Centro Cultural do Brasil, São Paulo, 2013[95]

- Billboard, Biennial of the Americas, Denver, 2013[96]

- Supersurrealism, 2012 Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 2012[97]

- Posthastism, Pavilion Gallery, Beijing, 2011 [98]

Journalism

Coupland has written extensively for Vice magazine and writes a column for the FT Magazine.[99][100] He also regularly contributes to Edge.org.[101] and has contributed to Artforum[102] and Flash Art[103] and online art journals, such as e-flux[104] and DIS Magazine.[105]

Design work

In the summer of 2010, Coupland, in collaboration with Roots Canada, designed a well-received collection of summer streetwear for men and women, and a line of leather and non-leather accessories. The collection was sold in the avant garde clothing store Colette in Paris in September 2010.

Television

In 2007, Coupland worked with the CBC to write and executive-produce a television series based on his novel jPod. Its 13 one-hour episodes aired in Canada in 2007. The show was cancelled despite a major viewer-initiated campaign to save it.[106]

Girlfriend in a Coma is being developed as a limited series.

Film

2005 marked the release of a documentary about Coupland called Souvenir of Canada. In it, Coupland works on a grand art project about Canada, recounts his life, and muses about various aspects of Canadian identity.

2006 brought the release of Everything's Gone Green, a comedy film starring Paulo Costanzo, directed by Paul Fox, and written by Coupland. The film was produced by Radke Films and True West Films. The distributor is THINKFilm in Canada and Shoreline Entertainment elsewhere. The film, Coupland's first screenplay, won the award for best Canadian feature film at the 2006 Vancouver International Film Festival.

Charity

Coupland is involved with Canada's Terry Fox Foundation. In 2005, Douglas & McIntyre published Terry, Coupland's biographical collection of photos and text essays about the life of legendary one-legged Canadian athlete Terry Fox. All proceeds from the book are donated to the foundation for cancer research. Terrys format is similar to that of Coupland's City of Glass and Souvenir of Canada books. Its release coincided with the 25th anniversary of Terry Fox's 1980 Marathon of Hope.

Coupland codesigned Canoe Landing Park, an eight-hectare urban park in downtown Toronto adjacent to the Gardiner Expressway. The park, opened 2009, is embedded with a one-mile run called the Terry Fox Miracle Mile. The Miracle Mile contains art from Terry.[107]

Coupland has raised money for the Vancouver Art Gallery and the Western Canada Wilderness Committee by participating in advertising campaigns.

Coupland is also a regular contributor to Wikipedia; during his appearance at the Cheltenham Literary Festival (UK) in 2013, to promote his novel Worst.Person.Ever., Coupland said that he gives $200 a year to the online encyclopaedia.

Personal life

Coupland lives and works in West Vancouver, British Columbia.[108]

Bibliography

Novels

- Worst. Person. Ever. (October 2013)[49]

- Player One (2010) (Novel adapted from 2010 to 2011 Massey Lectures, long-listed for the Giller Prize)

- Generation A (2009) (finalist for the 2009 Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize)

- The Gum Thief (2007)

- jPod (2006) (1st Hardcover Ed. ISBN 0-679-31424-5) (long-listed for the Giller Prize)

- Eleanor Rigby (2004)

- Hey Nostradamus! (2003)

- God Hates Japan (2001) (Published only in Japan, in Japanese with little English. Japanese title is 神は日本を憎んでる (Kami ha Nihon wo Nikunderu))

- All Families Are Psychotic (2001)

- Miss Wyoming (2000)

- Girlfriend in a Coma (1998)

- Microserfs (1995)

- Shampoo Planet (1992)

- Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture (1991)

Short stories and story collections

- Binge (2021)

- Highly Inappropriate Tales for Young People (2011) (with Graham Roumieou)

- "Fire At The Ativan Factory" (1998), short story featured in Disco 2000

- Life After God (1994)

Non-fiction

- It's All Happening So Fast: A Counter-History of the Modern Canadian Environment (2017) (Contributor)[109]

- Photography at MoMA: 1920 to 1960 (2016) (Contributor)[110]

- Machines Will Make Better Choices Than Humans (2016) (Foreword: Michel Van Dartel)

- Bit Rot (catalog, 2015; expanded edition, 2016)

- The Age of Earthquakes: A Guide to the Extreme Present (2015) (with Shumon Basar and Hans Ulrich Obrist)

- Kitten Clone: Inside Alcatel-Lucent (2014)

- Shopping in Jail: Ideas Essays and Stories for the Increasingly Real 21st Century (2013)

- Extraordinary Canadians: Marshall McLuhan (2009)

- Terry (2005)

- Souvenir of Canada 2 (2004)

- School Spirit (2002)

- Souvenir of Canada (2002)

- City of Glass (2000) (updated version 2010)

- Polaroids from the Dead (1996)

Drama and screenplays

- All Families Are Psychotic (2009) Announced on 9 February 2016, based on the novel of the same name.

- jPod (2008) (TV series) Premiered January 8, 2008 on CBC]. Canceled on March 7, 2008. Final airing April 4, 2008.

- Everything's Gone Green (2007)

- Souvenir of Canada (2005) (writing and narration)

- September 10 (2004)

- Douglas Coupland: Close Personal Friend (1996)

Criticism and interpretation

Essays

- Doody, Christopher. "X-plained: The Production and Reception History of Douglas Coupland’s Generation X." Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada 49.1 (2011): 5–34.

- Jensen, Mikkel. "Miss(ed) Generation: Douglas Coupland’s Miss Wyoming. Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine Culture Unbound 3 (2011): 455–474.

- McCampbell, Mary. "GOD IS NOWHERE. GOD IS NOW HERE: The Co-existence of Hope and Evil in Douglas Coupland's Hey Nostradamus. Yearbook of English Studies 39.1 (2009): 137–154.

- Dalton-Brown, Sally. "The Dialectics of Emptiness: Douglas Coupland's and Viktor Pelevin's Tales of Generation X and P." Forum for Modern Language Studies 42.3 (2006): 239–48.

- Steen, Marc. "Reading Microserfs : A story of research and development as a search for identity." Proceedings of SCOS 2005 Conference ( Stockholm, 8–10 July 2005): 220–232.

- Katerberg, William H. "Western Myth and the End of History in the Novels of Douglas Coupland." Western American Literature 40.3 (2005): 272–99.

- Tate, Andrew. "'Now-here is My Secret': Ritual and Epiphany in Douglas Coupland's Fiction." Literature & Theology: An International Journal of Religion, Theory, and Culture 16.3 (2002): 326–38.

- Forshaw, Mark. "Douglas Coupland: In and Out of 'Ironic Hell'." Critical Survey 12.3 (2000): 39–58.

- McGill, Robert. "The Sublime Simulacrum: Vancouver in Douglas Coupland's Geography of Apocalypse." Essays on Canadian Writing 70 (2000): 252–76.

- McCampbell, Mary. "Consumer in a Coma: Douglas Coupland's Rewriting of the Contemporary Apocalypse" in Spiritual Identities: Literature and the Post-Secular Imagination . Eds. Arthur Bradley, Jo *Carruthers, and Andrew Tate.

Books

- Zurbrigg, Terri Susan. X = What? Douglas Coupland, Generation X, and the Politics of Postmodern Irony. VDM Verlag, 2008.

- Giles, Paul. The Global Remapping of American Literature. Princeton University Press, 2011 [contains discussion incorporating City of Glass, Generation X, Shampoo Planet, Polaroids from the Dead, Microserfs, Girlfriend in a Coma, Miss Wyoming, and J-Pod].

- Hutchinson, Colin. Reaganism, Thatcherism and the Social Novel. Palgrave Macmillan., 2008 [contains sections covering Generation X, Shampoo Planet, and Microserfs].

- Tate, Andrew. Douglas Coupland. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007 [emphasis on religious elements].

- Grassian, Daniel. Hybrid Fictions: American Literature and Generation X. McFarland & Co Inc, 2003 [contains lengthy discussion of Microserfs ].

See also

Notes

- ^ Pronounced /ˈkoʊplənd/ KOHP-lənd.[2]

References

- ^ "Douglas Coupland". Bookclub. 7 March 2010. BBC Radio 4. Archived from the original on 9 April 2011. Retrieved 2014-01-18.

- ^ Steve Lohr, "No More McJobs for Mr. X", The New York Times, May 29, 1994

- ^ "Douglas Coupland". www.ft.com. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 25 December 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ "Douglas Coupland · About & Contact". Douglas Coupland. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ "Vancouver Art Gallery". www.vanartgallery.bc.ca. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ "Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto Canada – Douglas Coupland: everywhere is anywhere is anything is everything". museumofcontemporaryart.ca. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Bit Rot, Douglas Coupland, Friday 11 September 2015 – Sunday 3 January 2016". Archived from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Museum Villa Stuck: Douglas Coupland. Bit Rot". www.villastuck.de. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Governor General Announces 90 New Appointments to the Order of Canada". December 30, 2013. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ^ a b "Author Douglas Coupland among 25 recipients of Order of B.C." Vancouver Sun. 30 May 2014. Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 28 Jul 2015.

- ^ "Extraordinary Canadians". Archived from the original on 2011-03-07. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- ^ "John Vaillant, Douglas Coupland among writers nominated for BC Book Prizes | Afterword | National Post". Arts.nationalpost.com. 2011-03-10. Archived from the original on 2012-07-07. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ "BC Book Prizes". Bcbookprizes.ca. Archived from the original on 2011-09-02. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ "Coupland, Bowering on shortlist for B.C. Book Prizes". Archived from the original on March 18, 2011. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ a b Wark, Penny."Trawling for Columbine". The Times, September 12th, 2003.

- ^ Colman, David. "Take a Sharp Turn at Fiorucci". The New York Times, September 30, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Jackson, Alan. "I didn't get where I am today without ..." The Times, June 17, 2006.

- ^ "The week in Reviews:Talkin' about his generation". The Observer, April 26, 1998.

- ^ "The author who coined a generation, Douglas Coupland". coupland.tripod.com. University Wire. February 1, 2001. Archived from the original on October 13, 2018. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- ^ "Douglas Coupland: 'The nine to five is barbaric'". The Guardian, March 30, 2017.

- ^ Barker, Pat. "Behind the Lines". The Times, October 9, 2007.

- ^ a b Dafoe, Chris. "Carving a profile from a forgotten generation". The Globe and Mail, November 9, 1991.

- ^ McLaren, Leah. "Birdman of BC". The Globe and Mail, September 28, 2006.

- ^ a b Coupland, Douglas (September 26, 2009). "Guardian book club: week three". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ Muro, Mark. "'Baby Busters' resent life in Boomers' debris". The Boston Globe, November 10, 1991.

- ^ Coupland, Douglas (June 4, 2006). "Ask the author". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ^ Cunningham, Guy Patrick (2015). "Generation X". In Ciment, James (ed.). Postwar America: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural, and Economic History, Volume 2. Routledge. p. 596. ISBN 978-1-317-46235-4.

The expression was later popularized by the American author Douglas Coupland, who borrowed it for the title of his 1991 novel Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture.

- ^ Smith, Vicki, ed. (2013). Sociology of Work: An Encyclopedia, Volume 2. SAGE Publications. pp. 1019–1020. ISBN 978-1-4522-7618-2.

The term [McJob] was popularized by Douglas Coupland's 1991 novel Generation X.

- ^ Coupland, Douglas. City of Glass

- ^ Mount, Ferdinand (2008-03-05). "The downfall of a pessimist". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 2009-01-11. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ^ Grimwood, Jon Courtenay. "Nerds of the cyberstocracy". The Independent, November 13, 1995

- ^ Smith, Stephen. "Dictators and comas". [he Globe and Mail, March 14, 1998.

- ^ "Dealing with the X factor". The Age, July 30, 2005.

- ^ Wheelwright, Julie. "Talking About Which Generation?" The Independent, February 12, 2000.

- ^ Gill, Alexandra. "Mirror, mirror on the page". The Globe and Mail, December 30, 2004.

- ^ "A slacker hero hits the stage". The Globe and Mail, July 31, 2004.

- ^ Anthony, Andrew. "Close to the Edge". The Observer, August 24, 2003.

- ^ "Dealing with the X factor". The Age, July 30, 2005.

- ^ Ken Macqueen (2006-05-08). "Douglas Coupland: Playing with the Google generation | Macleans.ca - Culture - Books". Macleans.ca. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ "Generation A". Archived from the original on July 15, 2009. Retrieved April 19, 2009.

- ^ "Coupland submits novel (!) for 2010 Massey Lecture". Archived from the original on 2011-08-20. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ Whittall, Zoe (2010-04-29). "Q&A with Douglas Coupland about his upcoming Massey Lectures title | Quillblog | Quill & Quire". Quillandquire.com. Archived from the original on 2010-07-04. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ a b "TITLES". Anansi.ca. 2011-04-01. Archived from the original on 2011-03-12. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ lrojas@capitalc.ca (2011-10-21). "Home". Scotiabank Giller Prize. Archived from the original on 2011-11-13. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ "Canada's Giller Prize reveals nominees". The Independent. London. September 20, 2010. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ Barber, John (September 20, 2010). "Small presses dominate Giller long list". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on September 25, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ "2010 Scotiabank Giller Prize longlist revealed | Afterword | National Post". Arts.nationalpost.com. 2010-09-20. Archived from the original on 2012-07-10. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ "Highly Inappropriate Tales for Young People". Archived from the original on 2012-02-09. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- ^ a b "Douglas Coupland – Worst Person Ever cover art and synopsis reveal". Upcoming4.me. July 26, 2013. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013.

- ^ Elek, John (May 21, 2006). "When Ronald McDonald did dirty deeds". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ King, Edward (September 20, 2009). "Generation A by Douglas Coupland: review". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 6, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ^ "Douglas Coupland, chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres". La France au Canada. 5 May 2015. Archived from the original on 12 August 2015. Retrieved 28 Jul 2015.

- ^ "BC Book Prizes". www.bcbookprizes.ca. Archived from the original on 2017-04-10. Retrieved 2017-04-10.

- ^ "Vancouver's Douglas Coupland lands Lieutenant Governor's Award for Literary Excellence". Vancouver Sun. 2017-04-04. Archived from the original on 2017-04-10. Retrieved 2017-04-10.

- ^ "New members 2007". Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. Archived from the original on 28 May 2007. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Douglas Coupland RCA. "Royal Canadian Academy of Arts – Académie royale des arts du Canada". Rca-arc.ca. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ "Emily Carr Announces 2010 Honorary Doctorate and Emily Award Recipients | Emily Carr University". Ecuad.ca. Archived from the original on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ "SFU 2007 Honorary Degree Recipients". Archived from the original on May 31, 2008. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- ^ "Rick Mercer, John Furlong, Douglas Coupland to receive honorary degrees from UBC". 3 May 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-05-03.

- ^ "Mount Allison University Honorary Degree Recipients". Archived from the original on June 9, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ OCAD University to confer honorary degrees on Douglas Coupland and Duke Redbird Archived June 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Ocadu.ca (2013-05-30). Retrieved on 2013-07-26.

- ^ a b "CTV British Columbia – Douglas Coupland donates archives to UBC – CTV News". Ctvbc.ctv.ca. 2010-05-20. Archived from the original on 2011-08-16. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ a b c "UBC Library welcomes Douglas Coupland archives « UBC Public Affairs". Publicaffairs.ubc.ca. 2010-05-20. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ Samson, Natalie. (2012-07-27) Quill & Quire » Behind the scenes at UBC’s Douglas Coupland archives Archived February 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Quillandquire.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-26.

- ^ New at Rare Books & Special Collections | Updates, announcements, and new resources Archived 2012-06-14 at the Wayback Machine. Blogs.ubc.ca. Retrieved on 2013-07-26.

- ^ Dundas, Deborah (May 22, 2020). "Douglas Coupland's slogans define our experience and bring us together". Toronto Star. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ Henry, Chris (June 29, 2021). "Douglas Coupland fuses AI and art to inspire students". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ "TWA Terminal Named as One of the Nation's Most Endangered Places". Municipal Art Society New York, February 9th, 2004. Archived from the original on 2009-08-12. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- ^ "A Review of a Show You Cannot See". Designobvserver.com, Tom Vanderbilt, January 14, 2005. Archived from the original on 2012-12-05.

- ^ "Now Boarding: Destination, JFK". The Architects Newspaper, September 21, 2004. Archived from the original on 2010-12-06.

- ^ Canadian Fallen Firefighter's Foundation's article about the contract awarding for the new national monument Archived January 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Canadian Fallen Firefighters Memorial: Douglas Coupland: Douglas Coupland". 6 December 2019. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ Thomson, Stephen (4 October 2012). "Douglas Coupland unveils new public artwork in Vancouver". The Georgia Straight. Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ^ "Douglas Coupland creating replica of Stanley Park Hollow Tree". CBC.ca. 14 March 2014. Archived from the original on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ^ "Douglas Coupland's Golden Tree Unveiled in Vancouver". August 6, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ "Public Art Archives -- Douglas Coupland: Douglas Coupland". Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ "Google Art Project jumped at chance to work with Douglas Coupland". Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Gilligan, Melissa (22 April 2019). "Dazzling light show at Calgary's Telus Sky skyscraper debuts Saturday". Global News. Corus Entertainment. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ everywhere is anywhere is anything is everything Archived 2014-08-11 at the Wayback Machine, Vancouver Art Gallery, retrieved 2014-08-08.

- ^ Griffin, Kevin (May 30, 2014), "Douglas Coupland: The future is everything", Vancouver Sun, archived from the original on January 31, 2019, retrieved January 26, 2019

- ^ "Explore Vancouver Art Gallery". Retrieved 30 July 2015.[dead link]

- ^ "Douglas Coupland: everywhere is anywhere is anything is everything". Archived from the original on 26 July 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "Douglas Coupland". Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "Bit Rot | Exhibit | Villa Stücke". Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ "Assembling the Future". coupland.com. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ "LEXUS HYBRID ART. ANTICIPATION. ASSEMBLING THE FUTURE 12 OCTOBER – 25 OCTOBER". Manege. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA). "It's All Happening So Fast". www.cca.qc.ca. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- ^ "Douglas Coupland · VORTEX". Douglas Coupland. Archived from the original on 2018-06-14. Retrieved 2018-07-19.

- ^ "Douglas Coupland's Vortex Coming to Vancouver Aquarium – Ocean Wise's AquaBlog". www.aquablog.ca. 30 January 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-07-19. Retrieved 2018-07-19.

- ^ "Douglas Coupland · The National Portrait". Douglas Coupland. Archived from the original on 2018-07-19. Retrieved 2018-07-19.

- ^ "The National Portrait – Ottawa Art Gallery". oaggao.ca. Archived from the original on 2018-07-19. Retrieved 2018-07-19.

- ^ Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA). "Super City". www.cca.qc.ca. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- ^ "The heart is deceitful above all things". 22 May 2015. Archived from the original on 2 August 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "The Fab Mind". Archived from the original on 2017-12-16. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "In São Paulo for the Bienal? Make time for these..." September 1, 2014. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "Biennial of the Americas". Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "Supersurrealism". Archived from the original on 14 September 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "Douglas Coupland Included in Beijing Posthastism". Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Coupland, Douglas (16 July 2015). "We are data: the future of machine intelligence". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 28 July 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "List of FT Magazine Articles". Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "Douglas Coupland". Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "Wildest Dreams". November 2017. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ "Me. You. Us. Them". Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ "Douglas Coupland". Archived from the original on 12 August 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "Creep". 2015. Archived from the original on 30 July 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "Save jPod". 2007. Archived from the original on 2019-08-06. Retrieved 2019-11-24.

- ^ "National Post Article on Miracle Mile". Nationalpost.com. Archived from the original on 2012-09-03. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ Kurutz, Steven (2009-08-12). "Saving the House Next Door". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2012-02-25. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- ^ "It's All Happening So Fast: A Counter-History of the Modern Canadian Environment". coupland.com. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ "Photography at MoMA: 1920 to 1960". coupland.com. Archived from the original on 2018-01-08. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

External links

- Official website

- Douglas Coupland's NY Times Blog: Time Capsules

- "Coupland, Douglas 1961– (Douglas Campbell Coupland)." Contemporary Authors, New Revision Series. Gale. 2008.

- Douglas Coupland at IMDb

- Douglas Coupland's entry in The Canadian Encyclopedia

- 2013 essay by Coupland on the writing of Generation X

- 1961 births

- Living people

- 20th-century Canadian novelists

- 21st-century Canadian novelists

- 21st-century Canadian dramatists and playwrights

- Canadian male novelists

- Canadian gay writers

- Canadian gay artists

- McGill University alumni

- Members of the Order of British Columbia

- Officers of the Order of Canada

- People from West Vancouver

- Wired (magazine) people

- Canadian fashion designers

- Artists from British Columbia

- Postmodern writers

- Emily Carr University of Art and Design alumni

- Canadian LGBTQ dramatists and playwrights

- Canadian LGBTQ novelists

- 20th-century Canadian sculptors

- Canadian male sculptors

- 20th-century Canadian male artists

- Canadian male screenwriters

- Canadian male dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century Canadian male writers

- 21st-century Canadian male writers

- 20th-century Canadian screenwriters

- 21st-century Canadian screenwriters

- 21st-century Canadian LGBTQ people

- Members of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts

- Gay screenwriters

- Gay dramatists and playwrights

- Gay novelists

- Screenwriters from British Columbia