Crohn's disease: Difference between revisions

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

====Renal and urological==== |

====Renal and urological==== |

||

[[Nephrolithiasis]], [[obstructive uropathy]], and [[Fistula|fistulization]] of the urinary tract directly result from the underlying disease process. Nephrolithiasis is due to calcium oxalate or uric acid stones. Calcium oxalate |

[[Nephrolithiasis]], [[obstructive uropathy]], and [[Fistula|fistulization]] of the urinary tract directly result from the underlying disease process. Nephrolithiasis is due to calcium oxalate or uric acid stones. Calcium oxalate stones due to hyperoxaluria are typically associated with either distal ileal CD or ileal resection. Oxalate absorption increases in the presence of unabsorbed fatty acids in the colon. The fatty acids compete with oxalate to bind calcium, displacing the oxalate, which can then be absorbed as unbound sodium oxalate across colonocytes and excreted into the urine. Because sodium oxalate only is absorbed in the colon, calcium-oxalate stones form only in patients with an intact colon. Patients with an [[ileostomy]] are prone to formation of uric-acid stones because of frequent dehydration. The sudden onset of severe abdominal, back, or flank pain in patients with IBD, particularly if different from the usual discomfort, should lead to inclusion of a renal stone in the differential diagnosis.<ref name="Manifestations" /> |

||

[[Urology|Urological]] manifestations in patients with IBD may include ureteral calculi, enterovesical [[fistula]], perivesical infection, perinephric abscess, and obstructive uropathy with [[hydronephrosis]]. Ureteral compression is associated with retroperitoneal extension of the phlegmonous inflammatory process involving the [[Ileum|terminal ileum]] and [[cecum]], and may result in [[hydronephrosis]] severe enough to cause [[hypertension]].<ref name="Manifestations" /> |

[[Urology|Urological]] manifestations in patients with IBD may include ureteral calculi, enterovesical [[fistula]], perivesical infection, perinephric abscess, and obstructive uropathy with [[hydronephrosis]]. Ureteral compression is associated with retroperitoneal extension of the phlegmonous inflammatory process involving the [[Ileum|terminal ileum]] and [[cecum]], and may result in [[hydronephrosis]] severe enough to cause [[hypertension]].<ref name="Manifestations" /> |

||

Revision as of 21:33, 26 September 2024

Crohn's disease is a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that may affect any segment of the gastrointestinal tract.[3] Symptoms often include abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, abdominal distension, and weight loss.[1][3] Complications outside of the gastrointestinal tract may include anemia, skin rashes, arthritis, inflammation of the eye, and fatigue.[1] The skin rashes may be due to infections as well as pyoderma gangrenosum or erythema nodosum.[1] Bowel obstruction may occur as a complication of chronic inflammation, and those with the disease are at greater risk of colon cancer and small bowel cancer.[1]

Although the precise causes of Crohn's disease (CD) are unknown, it is believed to be caused by a combination of environmental, immune, and bacterial factors in genetically susceptible individuals.[3][13][14][15] It results in a chronic inflammatory disorder, in which the body's immune system defends the gastrointestinal tract, possibly targeting microbial antigens.[14][16] While Crohn's is an immune-related disease, it does not seem to be an autoimmune disease (the immune system is not triggered by the body itself).[17] The exact underlying immune problem is not clear; however, it may be an immunodeficiency state.[16][18][19]

About half of the overall risk is related to genetics, with more than 70 genes involved.[1][20] Tobacco smokers are three times as likely to develop Crohn's disease as non-smokers.[6] It often begins after gastroenteritis.[1] Other conditions with similar symptoms include irritable bowel syndrome and Behçet's disease.[1]

There is no known cure for Crohn's disease.[1][3] Treatment options are intended to help with symptoms, maintain remission, and prevent relapse.[1] In those newly diagnosed, a corticosteroid may be used for a brief period of time to improve symptoms rapidly, alongside another medication such as either methotrexate or a thiopurine used to prevent recurrence.[1] Cessation of smoking is recommended for people with Crohn's disease.[1] One in five people with the disease is admitted to the hospital each year, and half of those with the disease will require surgery at some time during a ten-year period.[1] While surgery should be used as little as possible, it is necessary to address some abscesses, certain bowel obstructions, and cancers.[1] Checking for bowel cancer via colonoscopy is recommended every few years, starting eight years after the disease has begun.[1]

Crohn's disease affects about 3.2 per 1,000 people in Europe and North America;[12] it is less common in Asia and Africa.[21][22] It has historically been more common in the developed world.[23] Rates have, however, been increasing, particularly in the developing world, since the 1970s.[22][23] Inflammatory bowel disease resulted in 47,400 deaths in 2015,[24] and those with Crohn's disease have a slightly reduced life expectancy.[1] It tends to start in adolescence and young adulthood, though it can occur at any age.[25][1][3][26] Males and females are equally affected.[3]

Name controversy

The disease was named after gastroenterologist Burrill Bernard Crohn, who in 1932, together with Leon Ginzburg (1898–1988) and Gordon D. Oppenheimer (1900–1974) at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, described a series of patients with inflammation of the terminal ileum of the small intestine, the area most commonly affected by the illness.[27] Why the disease was named after Crohn has controversy around it.[28][29] While Crohn, in his memoir, describes his original investigation of the disease, Ginzburg provided strong evidence of how he and Oppenheimer were the first to study the disease.[30]

Signs and symptoms

| Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Defecation | Often porridge-like,[31] sometimes steatorrhea |

Often mucus-like and with blood[31] |

| Tenesmus | Less common[31] | More common[31] |

| Fever | Common[31] | Indicates severe disease[31] |

| Fistulae | Common[32] | Seldom |

| Weight loss | Often | More seldom |

Gastrointestinal

Many people with Crohn's disease have symptoms for years before the diagnosis.[33] The usual onset is in the teens and twenties, but can occur at any age.[26][1] Because of the 'patchy' nature of the gastrointestinal disease and the depth of tissue involvement, initial symptoms can be more subtle than those of ulcerative colitis.[citation needed] People with Crohn's disease experience chronic recurring periods of flare-ups and remission.[34] The symptoms experienced can change over time as inflammation increases and spreads. Symptoms can also be different depending on which organs are involved. It is generally thought that the presentation of Crohn's disease is different for each patient due to the high variability of symptoms, organ involvement, and initial presentation.

Perianal

Perianal discomfort may also be prominent in Crohn's disease. Itchiness or pain around the anus may be suggestive of inflammation of the anus, or perianal complications such as anal fissures, fistulae, or abscesses around the anal area.[1] Perianal skin tags are also common in Crohn's disease, and may appear with or without the presence of colorectal polyps.[35] Fecal incontinence may accompany perianal Crohn's disease.

Intestines

The intestines, especially the colon and terminal ileum, are the areas of the body affected most commonly. Abdominal pain is a common initial symptom of Crohn's disease,[3] especially in the lower right abdomen.[36] Flatulence, bloating, and abdominal distension are additional symptoms and may also add to the intestinal discomfort. Pain is often accompanied by diarrhea, which may or may not be bloody. Inflammation in different areas of the intestinal tract can affect the quality of the feces. Ileitis typically results in large-volume, watery feces, while colitis may result in a smaller volume of feces of greater frequency. Fecal consistency may range from solid to watery. In severe cases, an individual may have more than 20 bowel movements per day, and may need to awaken at night to defecate.[1][37][38][39] Visible bleeding in the feces is less common in Crohn's disease than in ulcerative colitis, but is not unusual.[1] Bloody bowel movements are usually intermittent, and may be bright red, dark maroon, or even black in color. The color of bloody stool depends on the location of the bleed. In severe Crohn's colitis, bleeding may be copious.[37]

Stomach and esophagus

The stomach is rarely the sole or predominant site of CD. To date there are only a few documented case reports of adults with isolated gastric CD and no reports in the pediatric population. Isolated stomach involvement is very unusual presentation accounting for less than 0.07% of all gastrointestinal CD.[40] However, the esophagus and stomach are increasingly understood to be affected in patients with intestinal CD. Recent studies suggest upper GI involvement occurs in 13-16% of cases, typically presenting after distal symptoms.[41][42][43] Upper gastrointestinal symptoms may include difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), upper abdominal pain, and vomiting.[44]

Oropharynx (mouth)

The mouth may be affected by recurrent sores (aphthous ulcers). Recurrent aphthous ulcers are common; however, it is not clear whether this is due to Crohn's disease or simply that they are common in the general population. Other findings may include diffuse or nodular swelling of the mouth, a cobblestone appearance inside the mouth, granulomatous ulcers, or pyostomatitis vegetans. Medications that are commonly prescribed to treat CD, such as anti-inflammatory and sulfa-containing drugs, may cause lichenoid drug reactions in the mouth. Fungal infection such as candidiasis is also common due to the immunosuppression required in the treatment of the disease. Signs of anemia such as pallor and angular cheilitis or glossitis are also common due to nutritional malabsorption.[45]

People with Crohn's disease are also susceptible to angular stomatitis, an inflammation of the corners of the mouth, and pyostomatitis vegetans.[46]

Systemic

Like many other chronic, inflammatory diseases, Crohn's disease can cause a variety of systemic symptoms.[1] Among children, growth failure is common. Many children are first diagnosed with Crohn's disease based on inability to maintain growth.[47] As it may manifest at the time of the growth spurt in puberty, as many as 30% of children with Crohn's disease may have retardation of growth.[48] Fever may also be present, though fevers greater than 38.5 °C (101.3 °F) are uncommon unless there is a complication such as an abscess.[1] Among older individuals, Crohn's disease may manifest as weight loss, usually related to decreased food intake, since individuals with intestinal symptoms from Crohn's disease often feel better when they do not eat and might lose their appetite.[47] People with extensive small intestine disease may also have malabsorption of carbohydrates or lipids, which can further exacerbate weight loss.[49]

Extraintestinal

Crohn's disease can affect many organ systems beyond the gastrointestinal tract.[50]

| Crohn's disease |

Ulcerative colitis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient deficiency | Higher risk | ||

| Colon cancer risk | Slight | Considerable | |

| Prevalence of extraintestinal complications[51][52][53] | |||

| Iritis/uveitis | Females | 2.2% | 3.2% |

| Males | 1.3% | 0.9% | |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis |

Females | 0.3% | 1% |

| Males | 0.4% | 3% | |

| Ankylosing spondylitis |

Females | 0.7% | 0.8% |

| Males | 2.7% | 1.5% | |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum |

Females | 1.2% | 0.8% |

| Males | 1.3% | 0.7% | |

| Erythema nodosum | Females | 1.9% | 2% |

| Males | 0.6% | 0.7% | |

Visual

Inflammation of the interior portion of the eye, known as uveitis, can cause blurred vision and eye pain, especially when exposed to light (photophobia).[54] Uveitis can lead to loss of vision if untreated.[50]

Inflammation may also involve the white part of the eye (sclera) or the overlying connective tissue (episclera), which causes conditions called scleritis and episcleritis, respectively.[54]

Other very rare ophthalmological manifestations include: conjunctivitis, glaucoma, and retinal vascular disease.[55]

Gallbladder and liver

Crohn's disease that affects the ileum may result in an increased risk of gallstones. This is due to a decrease in bile acid resorption in the ileum, and the bile gets excreted in the stool. As a result, the cholesterol/bile ratio increases in the gallbladder, resulting in an increased risk for gallstones.[54] Although the association is greater in the context of ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease may also be associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis, a type of inflammation of the bile ducts.[56]

Liver involvement of Crohn's disease can include cirrhosis and steatosis. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, NAFLD) are relatively common and can slowly progress to end-stage liver disease. NAFLD sensitizes the liver to injury and increases the risk of developing acute or chronic liver failure following another liver injury.[55]

Other rare hepatobiliary manifestations of Crohn's disease include: cholangiocarcinoma, granulomatous hepatitis, cholelithiasis, autoimmune hepatitis, hepatic abscess, and pericholangitis.[55]

Renal and urological

Nephrolithiasis, obstructive uropathy, and fistulization of the urinary tract directly result from the underlying disease process. Nephrolithiasis is due to calcium oxalate or uric acid stones. Calcium oxalate stones due to hyperoxaluria are typically associated with either distal ileal CD or ileal resection. Oxalate absorption increases in the presence of unabsorbed fatty acids in the colon. The fatty acids compete with oxalate to bind calcium, displacing the oxalate, which can then be absorbed as unbound sodium oxalate across colonocytes and excreted into the urine. Because sodium oxalate only is absorbed in the colon, calcium-oxalate stones form only in patients with an intact colon. Patients with an ileostomy are prone to formation of uric-acid stones because of frequent dehydration. The sudden onset of severe abdominal, back, or flank pain in patients with IBD, particularly if different from the usual discomfort, should lead to inclusion of a renal stone in the differential diagnosis.[55]

Urological manifestations in patients with IBD may include ureteral calculi, enterovesical fistula, perivesical infection, perinephric abscess, and obstructive uropathy with hydronephrosis. Ureteral compression is associated with retroperitoneal extension of the phlegmonous inflammatory process involving the terminal ileum and cecum, and may result in hydronephrosis severe enough to cause hypertension.[55]

Immune complex glomerulonephritis presenting with proteinuria and hematuria has been described in children and adults with CD or UC. Diagnosis is by renal biopsy, and treatment parallels the underlying IBD.[55]

Amyloidosis (see endocrinological involvement) secondary to Crohn's disease has been described and is known to affect the kidneys.[55]

Pancreatic

Pancreatitis may be associated with both UC and CD. The most common cause is iatrogenic and involves sensitivity to medications used to treat IBD (3% of patients), including sulfasalazine, mesalamine, 6-mercaptopurine, and azathioprine. Pancreatitis may present as symptomatic (in 2%) or more commonly asymptomatic (8–21%) disease in adults with IBD.[55]

Cardiovascular and circulatory

Children and adults with IBD have been rarely (<1%) reported developing pleuropericarditis either at initial presentation or during active or quiescent disease. The pathogenesis of pleuropericarditis is unknown, although certain medications (e.g., sulfasalazine and mesalamine derivatives) have been implicated in some cases. The clinical presentation may include chest pain, dyspnea, or in severe cases pericardial tamponade requiring rapid drainage. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have been used as therapy, although this should be weighed against the hypothetical risk of exacerbating the underlying IBD.[55]

In rare cases, cardiomyopathy, endocarditis, and myocarditis have been described.[55]

Crohn's disease also increases the risk of blood clots;[54] painful swelling of the lower legs can be a sign of deep venous thrombosis, while difficulty breathing may be a result of pulmonary embolism.

Respiratory

Laryngeal involvement in inflammatory bowel disease is extremely rare. Only 12 cases of laryngeal involvement in Crohn's disease have been reported as of 2019[update]. Moreover, only one case of laryngeal manifestations in ulcerative colitis has been reported as of the same date.[57] Nine patients complained of difficulty in breathing due to edema and ulceration from the larynx to the hypopharynx.[58] Hoarseness, sore throat, and odynophagia are other symptoms of laryngeal involvement of Crohn's disease.[59]

Considering extraintestinal manifestations of CD, those involving the lung are relatively rare. However, there is a wide array of lung manifestations, ranging from subclinical alterations, airway diseases and lung parenchymal diseases to pleural diseases and drug-related diseases. The most frequent manifestation is bronchial inflammation and suppuration with or without bronchiectasis. There are a number of mechanisms by which the lungs may become involved in CD. These include the same embryological origin of the lung and gastrointestinal tract by ancestral intestine, similar immune systems in the pulmonary and intestinal mucosa, the presence of circulating immune complexes and auto-antibodies, and the adverse pulmonary effects of some drugs.[60] A complete list of known pulmonary manifestations include: fibrosing alveolitis, pulmonary vasculitis, apical fibrosis, bronchiectasis, bronchitis, bronchiolitis, tracheal stenosis, granulomatous lung disease, and abnormal pulmonary function.[55]

Musculoskeletal

Crohn's disease is associated with a type of rheumatologic disease known as seronegative spondyloarthropathy.[54] This group of diseases is characterized by inflammation of one or more joints (arthritis) or muscle insertions (enthesitis).[54] The arthritis in Crohn's disease can be divided into two types. The first type affects larger weight-bearing joints such as the knee (most common), hips, shoulders, wrists, or elbows.[54] The second type symmetrically involves five or more of the small joints of the hands and feet.[54] The arthritis may also involve the spine, leading to ankylosing spondylitis if the entire spine is involved, or simply sacroiliitis if only the sacroiliac joint is involved.[54]

Crohn's disease increases the risk of osteoporosis or thinning of the bones.[54] Individuals with osteoporosis are at increased risk of bone fractures.[61]

Dermatological

Crohn's disease may also involve the skin, blood, and endocrine system. Erythema nodosum is the most common type of skin problem, occurring in around 8% of people with Crohn's disease, producing raised, tender red nodules usually appearing on the shins.[54][62][63] Erythema nodosum is due to inflammation of the underlying subcutaneous tissue, and is characterized by septal panniculitis.[62]

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a less common skin problem, occurring in under 2%,[63] and is typically a painful ulcerating nodule.[62][50]

Clubbing, a deformity of the ends of the fingers, may also be a result of Crohn's disease.[64]

Other very rare dermatological manifestations include: pyostomatitis vegetans, erythema multiforme, epidermolysis bullosa acquista (described in a case report), and metastatic CD (the spread of Crohn's inflammation to the skin[46]).[55] It is unknown if Sweet's syndrome is connected to Crohn's disease.[55]

Neurological

Crohn's disease can also cause neurological complications (reportedly in up to 15%).[65] The most common of these are seizures, stroke, myopathy, peripheral neuropathy, headache, and depression.[65]

Central and peripheral neurological disorders are described in patients with IBD and include peripheral neuropathies, myopathies, focal central nervous system defects, convulsions, confusional episodes, meningitis, syncope, optic neuritis, and sensorineural loss. Autoimmune mechanisms are proposed for involvement with IBD. Nutritional deficiencies associated with neurological manifestations, such as vitamin B12 deficiency, should be investigated. Spinal abscess has been reported in both a child and an adult with initial complaints of severe back pain due to extension of a psoas abscess from the epidural space to the subarachnoid space.[55]

Psychiatric and psychological

Crohn's disease is linked to many psychological disorders, including depression and anxiety, denial of one's disease, the need for dependence or dependent behaviors, feeling overwhelmed, and having a poor self-image.[66]

Many studies have found that patients with IBD report a higher frequency of depressive and anxiety disorders than the general population; most studies confirm that women with IBD are more likely than men to develop affective disorders and show that up to 65% of them may have depression and anxiety disorder.[67][68]

Endocrinological or hematological

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia, a condition in which the immune system attacks the red blood cells, is also more common in Crohn's disease and may cause fatigue, a pale appearance, and other symptoms common in anemia.

Secondary amyloidosis (AA) is another rare but serious complication of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), generally seen in Crohn's disease. At least 1% of patients with Crohn's disease develop amyloidosis. In the literature, the time lapse between the onset of Crohn's disease and the diagnosis of amyloidosis has been reported to range from 1 to 21 years.

Leukocytosis and thrombocytopenia are usually due to immunosuppressant treatments or sulfasalazine. Plasma erythropoietin levels often are lower in patients with IBD than expected, in conjunction with severe anemia.[55]

Thrombocytosis and thromboembolic events resulting from a hypercoagulable state in patients with IBD can lead to pulmonary embolism or thrombosis elsewhere in the body. Thrombosis has been reported in 1.8% of patients with UC and 3.1% of patients with CD. Thromboembolism and thrombosis are less frequently reported among pediatric patients, with three patients with UC and one with CD described in case reports.[55]

In rare cases, hypercoagulation disorders and portal vein thrombosis have been described.[55]

Malnutrition symptoms

People with Crohn's disease may develop anemia due to vitamin B12, folate, iron deficiency, or due to anemia of chronic disease.[69][70] The most common is iron deficiency anemia[69] from chronic blood loss, reduced dietary intake, and persistent inflammation leading to increased hepcidin levels, restricting iron absorption in the duodenum.[70] As Crohn's disease most commonly affects the terminal ileum where the vitamin B12/intrinsic factor complex is absorbed, B12 deficiency may be seen.[70] This is particularly common after surgery to remove the ileum.[69] Involvement of the duodenum and jejunum can impair the absorption of many other nutrients including folate. People with Crohn's often also have issues with small bowel bacterial overgrowth syndrome, which can produce micronutrient deficiencies.[71][72]

Complications

Intestinal damage

Crohn's disease can lead to several mechanical complications within the intestines, including obstruction,[73] fistulae,[74] and abscesses.[75] Obstruction typically occurs from strictures or adhesions that narrow the lumen, blocking the passage of the intestinal contents. A fistula can develop between two loops of bowel, between the bowel and bladder, between the bowel and vagina, and between the bowel and skin. Abscesses are walled-off concentrations of infection, which can occur in the abdomen or in the perianal area. Crohn's is responsible for 10% of vesicoenteric fistulae, and is the most common cause of ileovesical fistulae.[76]

Symptoms caused by intestinal stenosis, or the tightening and narrowing of the bowel, are also common in Crohn's disease. Abdominal pain is often most severe in areas of the bowel with stenosis. Persistent vomiting and nausea may indicate stenosis from small bowel obstruction or disease involving the stomach, pylorus, or duodenum.[37]

Intestinal granulomas are a walled-off portions of the intestine by macrophages in order to isolate infections. Granuloma formation is more often seen in younger patients, and mainly in the severe, active penetrating disease.[77] Granuloma is considered the hallmark of microscopic diagnosis in Crohn's disease (CD), but granulomas can be detected in only 21–60% of CD patients.[77]

Cancer

Crohn's disease also increases the risk of cancer in the area of inflammation. For example, individuals with Crohn's disease involving the small bowel are at higher risk for small intestinal cancer.[78] Similarly, people with Crohn's colitis have a relative risk of 5.6 for developing colon cancer.[79] Screening for colon cancer with colonoscopy is recommended for anyone who has had Crohn's colitis for at least eight years.[80]

Some studies suggest there is a role for chemoprotection in the prevention of colorectal cancer in Crohn's involving the colon; two agents have been suggested, folate and mesalamine preparations.[81] Also, immunomodulators and biologic agents used to treat this disease may promote developing extra-intestinal cancers.[82]

Some cancers, such as acute myelocytic leukaemia have been described in cases of Crohn's disease.[55] Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL) is a rare, lethal disease generally seen in young male patients with inflammatory bowel disease. TNF-α Inhibitor treatments (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, natalizumab, and etanercept) are thought to be the cause of this rare disease.[83]

Major complications

Major complications of Crohn's disease include bowel obstruction, abscesses, free perforation, and hemorrhage, which in rare cases may be fatal.[84][85]

Other complications

Individuals with Crohn's disease are at risk of malnutrition for many reasons, including decreased food intake and malabsorption. The risk increases following resection of the small bowel. Such individuals may require oral supplements to increase their caloric intake, or in severe cases, total parenteral nutrition (TPN). Most people with moderate or severe Crohn's disease are referred to a dietitian for assistance in nutrition.[86]

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is characterized by excessive proliferation of colonic bacterial species in the small bowel. Potential causes of SIBO include fistulae, strictures, or motility disturbances. Hence, patients with Crohn's disease are especially predisposed to develop SIBO. As result, CD patients may experience malabsorption and report symptoms such as weight loss, watery diarrhea, meteorism, flatulence, and abdominal pain, mimicking acute flare in these patients.[72]

Pregnancy

Crohn's disease can be problematic during pregnancy, and some medications can cause adverse outcomes for the fetus or mother. Consultation with an obstetrician and gastroenterologist about Crohn's disease and all medications facilitates preventive measures. In some cases, remission occurs during pregnancy. Certain medications can also lower sperm count or otherwise adversely affect a man's fertility.[87]

Ostomy-related complications

Common complications of an ostomy (a common surgery in Crohn's disease) are: mucosal edema, peristomal dermatitis, retraction, ostomy prolapse, mucosal/skin detachment, hematoma, necrosis, parastomal hernia, and stenosis.[88]

Etiology

The etiology of Crohn's disease is unknown. Many theories have been disputed, with four main theories hypothesized to be the primary mechanism of Crohn's disease. In autoimmune diseases, antibodies and T lymphocytes are the primary mode of inflammation. These cells and bodies are part of the adaptive immune system, or the part of the immune system that learns to fight foreign bodies when first identified.[89] Autoinflammatory diseases are diseases where the innate immune system, or the immune system we are genetically coded with, is designed to attack our own cells.[90] Crohn's disease likely has involvement of both the adaptive and innate immune systems.[91]

Autoinflammatory theory

Crohn's disease can be described as a multifactorial autoinflammatory disease. The etiopathogenesis of Crohn's disease is still unknown. In any event, a loss of the regulatory capacity of the immune apparatus would be implicated in the onset of the disease. In this respect interestingly enough, as for Blau's disease (a monogenic autoinflammatory disease), the NOD2 gene mutations have been linked to Crohn's disease. However, in Crohn's disease, NOD2 mutations act as a risk factor, being more common among Crohn's disease patients than the background population, while in Blau's disease NOD2 mutations are linked directly to this syndrome, as it is an autosomal-dominant disease. All this new knowledge in the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease allows us to put this multifactorial disease in the group of autoinflammatory syndromes.[90]

Some examples of how the innate immune system affects bowel inflammation have been described.[91] A meta-analysis of CD genome-wide association studies revealed 71 distinct CD-susceptibility loci. Interestingly, three very important CD-susceptibility genes (the intracellular pathogen-recognition receptor, NOD2; the autophagy-related 16-like 1, ATG16L1 and the immunity-related GTPase M, IRGM) are involved in innate immune responses against gut microbiota, while one (the X-box binding protein 1) is involved in regulation of the [adaptive] immune pathway via MHC class II,[92] resulting in autoinflammatory inflammation. Studies have also found that increased ILC3 can overexpress major histocompatibility complex (MHC) II. MHC class II can induce CD4+ T cell apoptosis, thus avoiding the T cell response to normal bowel micro bacteria. Further studies of IBD patients compared with non-IBD patients found that the expression of MHC II by ILC3 was significantly reduced in IBD patients, thus causing an immune reaction against intestinal cells or normal bowel bacteria and damaging the intestines. This can also make the intestines more susceptible to environmental factors, such as food or bacteria.[91]

The thinking is that because Crohn's disease has strong innate immune system involvement and has NOD2 mutations as a predisposition, Crohn's disease is more likely an autoinflammatory disease than an autoimmune disease.[91]

Immunodeficiency theory

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: All current sources are from 2010. (May 2024) |

A substantial body of data has emerged in recent years to suggest that the primary defect in Crohn's disease is actually one of relative immunodeficiency.[93] This view has been bolstered recently by novel immunological and clinical studies that have confirmed gross aberrations in this early response, consistent with subsequent genetic studies that highlighted molecules important for innate immune function. The suggestion therefore is that Crohn's pathogenesis actually results from partial immunodeficiency, a theory that coincides with the frequent recognition of a virtually identical, non-infectious inflammatory bowel disease arising in patients with congenital monogenic disorders impairing phagocyte function.[93]

Risk factors

| Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking | Higher risk for smokers | Lower risk for smokers[94] |

| Age | Usual onset between 15 and 30 years[95] |

Peak incidence between 15 and 25 years |

While the exact cause or causes are unknown, Crohn's disease seems to be due to a combination of environmental factors and genetic predisposition.[96] Crohn's is the first genetically complex disease in which the relationship between genetic risk factors and the immune system is understood in considerable detail.[97] Each individual risk mutation makes a small contribution to the overall risk of Crohn's (approximately 1:200). The genetic data, and direct assessment of immunity, indicates a malfunction in the innate immune system.[98] In this view, the chronic inflammation of Crohn's is caused when the adaptive immune system tries to compensate for a deficient innate immune system.[99]

Genetics

Crohn's has a genetic component.[101] Because of this, siblings of known people with Crohn's are 30 times more likely to develop Crohn's than the general population.[102]

The first mutation found to be associated with Crohn's was a frameshift in the NOD2 gene (also known as the CARD15 gene),[103] followed by the discovery of point mutations.[104] Over 30 genes have been associated with Crohn's; a biological function is known for most of them. For example, one association is with mutations in the XBP1 gene, which is involved in the unfolded protein response pathway of the endoplasmic reticulum.[105][106] The gene variants of NOD2/CARD15 seem to be related with small-bowel involvement.[107] Other well documented genes which increase the risk of developing Crohn's disease are ATG16L1,[108] IL23R,[109] IRGM,[110] and SLC11A1.[111] There is considerable overlap between susceptibility loci for IBD and mycobacterial infections.[112] Genome-wide association studies have shown that Crohn's disease is genetically linked to coeliac disease.[113]

Crohn's has been linked to the gene LRRK2 with one variant potentially increasing the risk of developing the disease by 70%, while another lowers it by 25%. The gene is responsible for making a protein, which collects and eliminates waste product in cells, and is also associated with Parkinson's disease.[114]

Immune system

There was a prevailing view that Crohn's disease is a primary T cell autoimmune disorder; however, a newer theory hypothesizes that Crohn's results from an impaired innate immunity.[115] The later hypothesis describes impaired cytokine secretion by macrophages, which contributes to impaired innate immunity and leads to a sustained microbial-induced inflammatory response in the colon, where the bacterial load is high.[14][98] Another theory is that the inflammation of Crohn's was caused by an overactive Th1 and Th17 cytokine response.[116][117]

In 2007, the ATG16L1 gene was implicated in Crohn's disease, which may induce autophagy and hinder the body's ability to attack invasive bacteria.[108] Another study theorized that the human immune system traditionally evolved with the presence of parasites inside the body and that the lack thereof due to modern hygiene standards has weakened the immune system. Test subjects were reintroduced to harmless parasites, with positive responses.[118]

Microbes

It is hypothesized that maintenance of commensal microorganism growth in the GI tract is dysregulated, either as a result or cause of immune dysregulation.[119][120]

There is an apparent connection between Crohn's disease, Mycobacterium, other pathogenic bacteria, and genetic markers.[121][122] A number of studies have suggested a causal role for Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP), which causes a similar disease, Johne's disease, in cattle.[123][124] In many individuals, genetic factors predispose individuals to Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection. This bacterium may produce certain compounds containing mannose, which may protect both itself and various other bacteria from phagocytosis, thereby possibly causing a variety of secondary infections.[125]

NOD2 is a gene involved in Crohn's genetic susceptibility. It is associated with macrophages' diminished ability to phagocytize MAP. This same gene may reduce innate and adaptive immunity in gastrointestinal tissue and impair the ability to resist infection by the MAP bacterium.[126] Macrophages that ingest the MAP bacterium are associated with high production of TNF-α.[127][128]

Other studies have linked specific strains of enteroadherent E. coli to the disease.[129] Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC), more common in people with CD,[130][131][129] have the ability to make strong biofilms compared to non-AIEC strains correlating with high adhesion and invasion indices[132][133] of neutrophils and the ability to block autophagy at the autolysosomal step, which allows for intracellular survival of the bacteria and induction of inflammation.[134] Inflammation drives the proliferation of AIEC and dysbiosis in the ileum, irrespective of genotype.[135] AIEC strains replicate extensively inside macrophages inducing the secretion of very large amounts of TNF-α.[136]

Mouse studies have suggested some symptoms of Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, and irritable bowel syndrome have the same underlying cause. Biopsy samples taken from the colons of all three patient groups were found to produce elevated levels of a serine protease.[137] Experimental introduction of the serine protease into mice has been found to produce widespread pain associated with irritable bowel syndrome, as well as colitis, which is associated with all three diseases.[138] Regional and temporal variations in those illnesses follow those associated with infection with the protozoan Blastocystis.[139]

The "cold-chain" hypothesis is that psychrotrophic bacteria such as Yersinia and Listeria species contribute to the disease. A statistical correlation was found between the advent of the use of refrigeration in the United States and various parts of Europe and the rise of the disease.[140][141][142]

There is also a tentative association between Candida colonization and Crohn's disease.[143]

Still, these relationships between specific pathogens and Crohn's disease remain unclear.[144][145]

Environmental factors

The increased incidence of Crohn's in the industrialized world indicates an environmental component. Crohn's is associated with an increased intake of animal protein, milk protein, and an increased ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids.[146] Those who consume vegetable proteins appear to have a lower incidence of Crohn's disease. Consumption of fish protein has no association.[146] Smoking increases the risk of the return of active disease (flares).[6] The introduction of hormonal contraception in the United States in the 1960s is associated with a dramatic increase in incidence, and one hypothesis is that these drugs work on the digestive system in ways similar to smoking.[147] Isotretinoin is associated with Crohn's.[148][149][150]

Although stress is sometimes claimed to exacerbate Crohn's disease, there is no concrete evidence to support such claim.[3] Still, it is well known that immune function is related to stress.[151] Dietary microparticles, such as those found in toothpaste, have been studied as they produce effects on immunity, but they were not consumed in greater amounts in patients with Crohn's.[152][153] The use of doxycycline has also been associated with increased risk of developing inflammatory bowel diseases.[154][155][156] In one large retrospective study, patients who were prescribed doxycycline for their acne had a 2.25-fold greater risk of developing Crohn's disease.[155]

Pathophysiology

| Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Cytokine response | Associated with Th17[157] | Vaguely associated with Th2 |

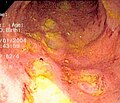

During a colonoscopy, biopsies of the colon are often taken to confirm the diagnosis. Certain characteristic features of the pathology seen point toward Crohn's disease; it shows a transmural pattern of inflammation, meaning the inflammation may span the entire depth of the intestinal wall.[1]

Granulomas, aggregates of macrophage derivatives known as giant cells, are found in 50% of cases and are most specific for Crohn's disease. The granulomas of Crohn's disease do not show "caseation", a cheese-like appearance on microscopic examination characteristic of granulomas associated with infections, such as tuberculosis. Biopsies may also show chronic mucosal damage, as evidenced by blunting of the intestinal villi, atypical branching of the crypts, and a change in the tissue type (metaplasia). One example of such metaplasia, Paneth cell metaplasia, involves the development of Paneth cells (typically found in the small intestine and a key regulator of intestinal microbiota) in other parts of the gastrointestinal system.[158][159]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of Crohn's disease can sometimes be challenging,[33] and many tests are often required to assist the physician in making the diagnosis.[37] Even with a full battery of tests, it may not be possible to diagnose Crohn's with complete certainty; a colonoscopy is approximately 70% effective in diagnosing the disease, with further tests being less effective. Disease in the small bowel is particularly difficult to diagnose, as a traditional colonoscopy allows access to only the colon and lower portions of the small intestines; introduction of the capsule endoscopy[160] aids in endoscopic diagnosis. Giant (multinucleate) cells, a common finding in the lesions of Crohn's disease, are less common in the lesions of lichen nitidus.[161]

-

Endoscopic image of Crohn's colitis showing deep ulceration

-

CT scan showing Crohn's disease in the fundus of the stomach

-

Section of colectomy showing transmural inflammation

-

Resected ileum from a person with Crohn's disease

Classification

Crohn's disease is one type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It typically manifests in the gastrointestinal tract and can be categorized by the specific tract region affected.

Gastroduodenal Crohn's disease causes inflammation in the stomach and the first part of the small intestine called the duodenum. Jejunoileitis causes spotty patches of inflammation in the top half of the small intestine, called the jejunum.[162] The disease can attack any part of the digestive tract, from mouth to anus. However, individuals affected by the disease rarely fall outside these three classifications, with presentations in other areas.[1]

Crohn's disease may also be categorized by the behavior of disease as it progresses. These categorizations formalized in the Vienna classification of the disease.[163] There are three categories of disease presentation in Crohn's disease: stricturing, penetrating, and inflammatory. Stricturing disease causes narrowing of the bowel that may lead to bowel obstruction or changes in the caliber of the feces. Penetrating disease creates abnormal passageways (fistulae) between the bowel and other structures, such as the skin. Inflammatory disease (or nonstricturing, nonpenetrating disease) causes inflammation without causing strictures or fistulae.[163][164]

Endoscopy

A colonoscopy is the best test for making the diagnosis of Crohn's disease, as it allows direct visualization of the colon and the terminal ileum, identifying the pattern of disease involvement. On occasion, the colonoscope can travel past the terminal ileum, but it varies from person to person. During the procedure, the gastroenterologist can also perform a biopsy, taking small samples of tissue for laboratory analysis, which may help confirm a diagnosis. As 30% of Crohn's disease involves only the ileum,[1] cannulation of the terminal ileum is required in making the diagnosis. Finding a patchy distribution of disease, with involvement of the colon or ileum, but not the rectum, is suggestive of Crohn's disease, as are other endoscopic stigmata.[165] The utility of capsule endoscopy for this, however, is still uncertain.[166]

Radiologic tests

A small bowel follow-through may suggest the diagnosis of Crohn's disease and is useful when the disease involves only the small intestine. Because colonoscopy and gastroscopy allow direct visualization of only the terminal ileum and beginning of the duodenum, they cannot be used to evaluate the remainder of the small intestine. As a result, a barium follow-through X-ray, wherein barium sulfate suspension is ingested and fluoroscopic images of the bowel are taken over time, is useful for looking for inflammation and narrowing of the small bowel.[165][167] Barium enemas, in which barium is inserted into the rectum and fluoroscopy is used to image the bowel, are rarely used in the work-up of Crohn's disease due to the advent of colonoscopy. They remain useful for identifying anatomical abnormalities when strictures of the colon are too small for a colonoscope to pass through, or in the detection of colonic fistulae (in this case contrast should be performed with iodate substances).[168]

CT and MRI scans are useful for evaluating the small bowel with enteroclysis protocols.[169] They are also useful for looking for intra-abdominal complications of Crohn's disease, such as abscesses, small bowel obstructions, or fistulae.[170] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is another option for imaging the small bowel as well as looking for complications, though it is more expensive and less readily available.[171] MRI techniques such as diffusion-weighted imaging and high-resolution imaging are more sensitive in detecting ulceration and inflammation compared to CT.[172][173]

Blood tests

A complete blood count may reveal anemia, which commonly is caused by blood loss leading to iron deficiency or by vitamin B12 deficiency, usually caused by ileal disease impairing vitamin B12 absorption. Rarely autoimmune hemolysis may occur.[174] Ferritin levels help assess if iron deficiency is contributing to the anemia. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein help assess the degree of inflammation, which is important as ferritin can also be raised in inflammation.[175]

Other causes of anemia include medication used in treatment of inflammatory bowel disease, like azathioprine, which can lead to cytopenia, and sulfasalazine, which can also result in folate deficiency. Testing for Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) has been evaluated to identify inflammatory diseases of the intestine[176] and to differentiate Crohn's disease from ulcerative colitis.[177] Furthermore, increasing amounts and levels of serological antibodies such as ASCA, antilaminaribioside [Glc(β1,3)Glb(β); ALCA], antichitobioside [GlcNAc(β1,4)GlcNAc(β); ACCA], antimannobioside [Man(α1,3)Man(α)AMCA], antiLaminarin [(Glc(β1,3))3n(Glc(β1,6))n; anti-L] and antichitin [GlcNAc(β1,4)n; anti-C] associate with disease behavior and surgery, and may aid in the prognosis of Crohn's disease.[178][179][180][181]

Low serum levels of vitamin D are associated with Crohn's disease.[182] Further studies are required to determine the significance of this association.[182]

Comparison with ulcerative colitis

The most common disease that mimics the symptoms of Crohn's disease is ulcerative colitis, as both are inflammatory bowel diseases that can affect the colon with similar symptoms. It is important to differentiate these diseases, since the course of the diseases and treatments may be different. In some cases, however, it may not be possible to tell the difference, in which case the disease is classified as indeterminate colitis.[1][37][38]

| Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Terminal ileum involvement | Commonly | Seldom |

| Colon involvement | Usually | Always |

| Rectum involvement | Seldom | Usually (95%)[94] |

| Involvement around the anus |

Common[183] | Seldom |

| Bile duct involvement | No increase in rate of primary sclerosing cholangitis | Higher rate[184] |

| Distribution of disease | Patchy areas of inflammation (skip lesions) | Continuous area of inflammation[94] |

| Endoscopy | Deep geographic and serpiginous (snake-like) ulcers | Continuous ulcer |

| Depth of inflammation | May be transmural, deep into tissues[183][185] | Shallow, mucosal |

| Stenosis | Common | Seldom |

| Granulomas on biopsy | May have non-necrotizing non-peri-intestinal crypt granulomas[183][186][187] | Non-peri-intestinal crypt granulomas not seen[188] |

Differential diagnosis

Other conditions with similar symptoms as Crohn's disease includes intestinal tuberculosis, Behçet's disease, ulcerative colitis, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug enteropathy, irritable bowel syndrome and celiac disease.[10] Irritable bowel syndrome is excluded when there are inflammatory changes.[10] Celiac disease cannot be excluded if specific antibodies (anti-transglutaminase antibodies) are negative,[189][190] nor in absence of intestinal villi atrophy.[191][192]

Management

| Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Mesalazine | Less useful[193] | More useful[193] |

| Antibiotics | Effective in long-term[194] | Generally not useful[195] |

| Surgery | Often returns following removal of affected part |

Usually cured by removal of colon |

There is no cure for Crohn's disease and remission may not be possible or prolonged if achieved. In cases where remission is possible, relapse can be prevented and symptoms controlled with medication, lifestyle and dietary changes, changes to eating habits (eating smaller amounts more often), reduction of stress, moderate activity, and exercise. Surgery is generally contraindicated and has not been shown to prevent relapse. Adequately controlled, Crohn's disease may not significantly restrict daily living.[196] Treatment for Crohn's disease involves first treating the acute problem and its symptoms, then maintaining remission of the disease.

Lifestyle changes

Certain lifestyle changes can reduce symptoms, including dietary adjustments, elemental diet, proper hydration, and smoking cessation. Recent reviews underlined the importance to adopt diets that are best supported by evidence, even if little is known about the impact of diets on these patients.[197][198] Diets that include higher levels of fiber and fruit are associated with reduced risk, while diets rich in total fats, polyunsaturated fatty acids, meat, and omega-6 fatty acids may increase the risk of Crohn's.[199] Maintaining a balanced diet with proper portion control can help manage symptoms of the disease. Eating small meals frequently instead of big meals may also help with a low appetite. A food diary may help with identifying foods that trigger symptoms. Despite the recognized importance of dietary fiber for intestinal health, some people should follow a low residue diet to control acute symptoms especially if foods high in insoluble fiber cause symptoms, e.g., due to obstruction or irritation of the bowel.[196] Some find relief in eliminating casein (a protein found in cow's milk) and gluten (a protein found in wheat, rye and barley) from their diets. They may have specific dietary intolerances (not allergies), for example, lactose.[200] Fatigue can be helped with regular exercise, a healthy diet, and enough sleep, and for those with malabsorption of vitamin B12 due to disease or surgical resection of the terminal ileum, cobalamin injections. Smoking may worsen symptoms and the course of the disease, and stopping is recommended. Alcohol consumption can also worsen symptoms, and moderation or cessation is advised.[196]

Medication

Acute treatment uses medications to treat any infection (normally antibiotics) and to reduce inflammation (normally aminosalicylate anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids). When symptoms are in remission, treatment enters maintenance, with a goal of avoiding the recurrence of symptoms. Prolonged use of corticosteroids has significant side-effects; as a result, they are, in general, not used for long-term treatment. Alternatives include aminosalicylates alone, though only a minority are able to maintain the treatment, and many require immunosuppressive drugs.[183] It has been also suggested that antibiotics change the enteric flora, and their continuous use may pose the risk of overgrowth with pathogens such as Clostridium difficile.[201]

Medications used to treat the symptoms of Crohn's disease include 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) formulations, prednisone, immunomodulators such as azathioprine (given as the prodrug for 6-mercaptopurine), methotrexate,[202] and anti-TNF therapies and monoclonal antibodies, such as infliximab, adalimumab,[38] certolizumab,[203] vedolizumab, ustekinumab,[204] natalizumab,[205][206]risankizumab-rzaa, and upadacitinib[207] Hydrocortisone should be used in severe attacks of Crohn's disease.[208] Biological therapies are medications used to avoid long-term steroid use, decrease inflammation, and treat people who have fistulas with abscesses.[36] The monoclonal antibody ustekinumab appears to be a safe treatment option, and may help people with moderate to severe active Crohn's disease.[209] The long term safety and effectiveness of monoclonal antibody treatment is not known.[209] The monoclonal antibody briakinumab is not effective for people with active Crohn's disease and it is no longer being manufactured.[209]

The gradual loss of blood from the gastrointestinal tract, as well as chronic inflammation, often leads to anemia, and professional guidelines suggest routinely monitoring for this.[210][211][212]

Immunosuppressant therapies, infection risks and vaccinations

Many patients affected by Crohn's disease need immunosuppressant therapies, which are known to be associated with a higher risk of contracting opportunistic infectious diseases and of pre-neoplastic or neoplastic lesions such as cervical high-grade dysplasia and cancer.[213][214] Many of these potentially harmful diseases, such as Hepatitis B, Influenza, herpes zoster virus, pneumococcal pneumonia, or human papilloma virus, can be prevented by vaccines. Each drug used in the treatment of IBD should be classified according to the degree of immunosuppression induced in the patient. Several guidelines suggest investigating patients’ vaccination status before starting any treatment and performing vaccinations against Vaccine-preventable disease when required.[215] Compared to the rest of the population, patients affected by IBD are known to be at higher risk of contracting some vaccine-preventable diseases such as flu and pneumonia.[216] Nevertheless, despite the increased risk of infections, vaccination rates in IBD patients are known to be suboptimal and may also be lower than vaccination rates in the general population.[217][218]

Surgery

Crohn's cannot be cured by surgery, as the disease eventually recurs, though it is used in the case of partial or full blockage of the intestine.[219] Surgery may also be required for complications such as obstructions, fistulas, or abscesses, or if the disease does not respond to drugs. After the first surgery, Crohn's usually comes back at the site where the diseased intestine was removed and the healthy ends were rejoined; it can also come back in other locations. After a resection, scar tissue builds up, which can cause strictures, which form when the intestines become too small to allow excrement to pass through easily, which can lead to a blockage. After the first resection, another resection may be necessary within five years.[220] For patients with an obstruction due to a stricture, two options for treatment are strictureplasty and resection of that portion of bowel. There is no statistical significance between strictureplasty alone versus strictureplasty and resection in cases of duodenal involvement. In these cases, re-operation rates were 31% and 27%, respectively, indicating that strictureplasty is a safe and effective treatment for selected people with duodenal involvement.[221]

Postsurgical recurrence of Crohn's disease is relatively common. Crohn's lesions are nearly always found at the site of the resected bowel. The join (or anastomosis) after surgery may be inspected, usually during a colonoscopy, and disease activity graded. The "Rutgeerts score" is an endoscopic scoring system for postoperative disease recurrence in Crohn's disease. Postsurgical remission per the Rutgeerts score is graded as i0; while mild postsurgical recurrences are graded i1 and i2, and moderate to severe recurrences are graded i3 and i4.[222] Fewer lesions result in a lower grade. Based on the score, treatment plans can be designed to give the patient the best chance of managing the recurrence of the disease.[223]

Short bowel syndrome (SBS, also short gut syndrome or simply short gut) is caused by the surgical removal of part of the small intestine. It usually develops in those patients who have had half or more of their small intestines removed.[224] Diarrhea is the main symptom, but others may include weight loss, cramping, bloating, and heartburn. Short bowel syndrome is treated with changes in diet, intravenous feeding, vitamin and mineral supplements, and treatment with medications. In some cases of SBS, intestinal transplant surgery may be considered; though the number of transplant centres offering this procedure is quite small and it comes with a high risk due to the chance of infection and rejection of the transplanted intestine.[225]

Bile acid diarrhea is another complication following surgery for Crohn's disease in which the terminal ileum has been removed. This leads to the development of excessive watery diarrhea. It is usually thought to be due to an inability of the ileum to reabsorb bile acids after resection of the terminal ileum and was the first type of bile acid malabsorption recognized.[226]

Microbiome modification

The use of oral probiotic supplements to modify the composition and behaviour of the gastrointestinal microbiome has been researched to understand whether it may help to improve remission rate in people with Crohn's disease. However, only two controlled trials were available in 2020, with no clear overall evidence of higher remission nor lower adverse effects, in people with Crohn's disease receiving probiotic supplementation.[227]

Mental health

Crohn's may result in anxiety or mood disorders, especially in young people who may have stunted growth or embarrassment from fecal incontinence.[228] Counselling as well as antidepressant or anxiolytic medication may help some people manage.[228]

As of 2017[update] there is a small amount of research looking at mindfulness-based therapies, hypnotherapy, and cognitive behavioural therapy.[229] A meta analysis of interventions to improve mood (including talking therapy, antidepressants, and exercise) in people with inflammatory bowel disease found that they reduced inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and faecal calprotectin. Psychological therapies reduced inflammation more than antidepressants or exercise.[230][231]

Alternative medicine

It is common for people with Crohn's disease to try complementary or alternative therapy.[232] These include diets, probiotics, fish oil, and other herbal and nutritional supplements.

- Acupuncture is used to treat inflammatory bowel disease in China, and is being used more frequently in Western society.[233] At this time, evidence is insufficient to recommend the use of acupuncture.[232]

- A 2006 survey in Germany found that about half of people with IBD used some form of alternative medicine, with the most common being homeopathy, and a study in France found that about 30% used alternative medicine.[234] Homeopathic preparations are not proven with this or any other condition,[235][236][237] with large-scale studies finding them to be no more effective than a placebo.[238][239][240]

- There are contradicting studies regarding the effect of medical cannabis on inflammatory bowel disease,[241] and its effects on management are uncertain.[242]

Prognosis

Crohn's disease is a chronic condition for which there is no known cure. It is characterised by periods of improvement followed by episodes when symptoms flare up. With treatment, most people achieve a healthy weight, and the mortality rate for the disease is relatively low. It can vary from being benign to very severe, and people with CD could experience just one episode or have continuous symptoms. It usually reoccurs, although some people can remain disease-free for years or decades. Up to 80% of people with Crohn's disease are hospitalized at some point during the course of their disease, with the highest rate occurring in the first year after diagnosis.[11] Most people with Crohn's live a normal lifespan.[243] However, Crohn's disease is associated with a small increase in risk of small bowel and colorectal carcinoma (bowel cancer).[244]

Epidemiology

The percentage of people with Crohn's disease has been determined in Norway and the United States and is similar at 6 to 7.1:100,000. The Crohn's & Colitis Foundation of America cites this number as approx 149:100,000; NIH cites 28 to 199 per 100,000.[245][246] Crohn's disease is more common in northern countries, and with higher rates still in the northern areas of these countries.[247] The incidence of Crohn's disease is thought to be similar in Europe but lower in Asia and Africa.[245] It also has a higher incidence in Ashkenazi Jews[1][248] and smokers.[249]

Crohn's disease begins most commonly in people in their teens and 20s, and people in their 50s through to their 70s.[1][37][26] It is rarely diagnosed in early childhood. It usually affects female children more severely than males.[250] However, only slightly more women than men have Crohn's disease.[251] Parents, siblings or children of people with Crohn's disease are 3 to 20 times more likely to develop the disease.[252] Twin studies find that if one has the disease there is a 55% chance the other will too.[253]

The incidence of Crohn's disease is increasing in Europe[254] and in newly industrialised countries.[255] For example, in Brazil, there has been an annual increase of 11% in the incidence of Crohn's disease since 1990.[255]

History

Inflammatory bowel diseases were described by Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682–1771) and by Scottish physician Thomas Kennedy Dalziel in 1913.[256]

Ileitis terminalis was first described by Polish surgeon Antoni Leśniowski in 1904, although it was not conclusively distinguished from intestinal tuberculosis.[257] In Poland, it is still called Leśniowski-Crohn's disease (Template:Lang-pl). Burrill Bernard Crohn, an American gastroenterologist at New York City's Mount Sinai Hospital, described fourteen cases in 1932, and submitted them to the American Medical Association under the rubric of "Terminal ileitis: A new clinical entity". Later that year, he, along with colleagues Leon Ginzburg and Gordon Oppenheimer, published the case series "Regional ileitis: a pathologic and clinical entity". However, due to the precedence of Crohn's name in the alphabet, it later became known in the worldwide literature as Crohn's disease.[27]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ (August 2012). "Crohn's disease". Lancet. 380 (9853): 1590–1605. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60026-9. PMID 22914295.

- ^ "Crohn's disease". Autoimmune Registry Inc. Archived from the original on June 15, 2022. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Crohn's Disease". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Archived from the original on December 8, 2019. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ Baumgart DC, Carding SR (May 2007). "Inflammatory bowel disease: cause and immunobiology". Lancet. 369 (9573): 1627–40. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60750-8. PMID 17499605.

- ^ Mawdsley JE, Rampton DS (October 2005). "Psychological stress in IBD: new insights into pathogenic and therapeutic implications". Gut. 54 (10): 1481–91. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.064261. PMC 1774724. PMID 16162953.

- ^ a b c Cosnes J (June 2004). "Tobacco and IBD: relevance in the understanding of disease mechanisms and clinical practice". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Gastroenterology. 18 (3): 481–496. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2003.12.003. PMID 15157822.

- ^ Koutroubakis IE (February 1999). "Appendectomy, tonsillectomy, and risk of inflammatory bowel disease". Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 42 (2): 225–230. doi:10.1007/BF02237133. PMID 10211500. S2CID 31528819. Archived from the original on June 13, 2019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Frisch M, Gridley G (October 2002). "Appendectomy in adulthood and the risk of inflammatory bowel diseases". Scand J Gastroenterol. 37 (10): 1175–7. doi:10.1080/003655202760373380. PMID 12408522.

- ^ Weili Sun, Xiao Han, Siyuan Wu, Chuanhua Yang (June 1, 2016). "Tonsillectomy and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 31 (6): 1085–94. doi:10.1111/jgh.13273. ISSN 1440-1746. PMID 26678358. S2CID 2625962. Archived from the original on August 16, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Inflammatory Bowel Disease" (PDF). World Gastroenterology Organization. August 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 14, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, Regueiro MD, Gerson LB, Sands BE (April 2018). "ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn's Disease in Adults". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 113 (4): 481–517. doi:10.1038/ajg.2018.27. PMID 29610508. S2CID 4568430.

- ^ a b Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, et al. (January 2012). "Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review". Gastroenterology. 142 (1): 46–54.e42, quiz e30. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. PMID 22001864. S2CID 206223870. Archived from the original on October 7, 2022. Retrieved October 7, 2022.

- ^ Cho JH, Brant SR (May 2011). "Recent insights into the genetics of inflammatory bowel disease". Gastroenterology. 140 (6): 1704–12. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.046. PMC 4947143. PMID 21530736.

- ^ a b c Dessein R, Chamaillard M, Danese S (September 2008). "Innate immunity in Crohn's disease: the reverse side of the medal". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 42 (Suppl 3 Pt 1): S144–7. doi:10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181662c90. PMID 18806708.

- ^ Stefanelli T, Malesci A, Repici A, Vetrano S, Danese S (May 2008). "New insights into inflammatory bowel disease pathophysiology: paving the way for novel therapeutic targets". Current Drug Targets. 9 (5): 413–8. doi:10.2174/138945008784221170. PMID 18473770.

- ^ a b Marks DJ, Rahman FZ, Sewell GW, Segal AW (February 2010). "Crohn's disease: an immune deficiency state". Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 38 (1): 20–31. doi:10.1007/s12016-009-8133-2. PMC 4568313. PMID 19437144.

- ^ Casanova JL, Abel L (August 2009). "Revisiting Crohn's disease as a primary immunodeficiency of macrophages". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 206 (9): 1839–43. doi:10.1084/jem.20091683. PMC 2737171. PMID 19687225.

- ^ Lalande JD, Behr MA (July 2010). "Mycobacteria in Crohn's disease: how innate immune deficiency may result in chronic inflammation". Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 6 (4): 633–641. doi:10.1586/eci.10.29. PMID 20594136. S2CID 25402952.

- ^ Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Korzenik JR (November 2006). "Crohn's disease: innate immunodeficiency?". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 12 (42): 6751–5. doi:10.3748/wjg.v12.i42.6751. PMC 4087427. PMID 17106921.

- ^ Barrett JC, Hansoul S, Nicolae DL, Cho JH, Duerr RH, Rioux JD, et al. (August 2008). "Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn's disease". Nature Genetics. 40 (8): 955–962. doi:10.1038/ng.175. PMC 2574810. PMID 18587394.

- ^ Prideaux L, Kamm MA, De Cruz PP, Chan FK, Ng SC (August 2012). "Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: a systematic review". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 27 (8): 1266–80. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07150.x. PMID 22497584. S2CID 205468282.

- ^ a b Hovde Ø, Moum BA (April 2012). "Epidemiology and clinical course of Crohn's disease: results from observational studies". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 18 (15): 1723–31. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i15.1723. PMC 3332285. PMID 22553396.

- ^ a b Burisch J, Munkholm P (July 2013). "Inflammatory bowel disease epidemiology". Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 29 (4): 357–62. doi:10.1097/MOG.0b013e32836229fb. PMID 23695429. S2CID 9538639.

- ^ GBD 2015 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". The Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ Shih IL, Lee TC, Tu CH, Chang CC, Wang YF, Tseng YH, et al. (December 1, 2016). "Intraobserver and interobserver agreement for identifying extraluminal manifestations of Crohn's disease with magnetic resonance enterography". Advances in Digestive Medicine. 3 (4): 174–180. doi:10.1016/j.aidm.2015.05.004. S2CID 70796090.

- ^ a b c "Crohn's Disease: Get Facts on Symptoms and Diet". eMedicineHealth. Archived from the original on October 20, 2007.

- ^ a b Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD (May 2000). "Regional ileitis: a pathologic and clinical entity. 1932". The Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, New York. 67 (3): 263–8. PMID 10828911.

- ^ Van Hootegem P, Travis S (July 9, 2020). "Is Crohn's Disease a Rightly Used Eponym?". Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 14 (6): 867–871. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz183. ISSN 1873-9946. PMID 31701137. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ Mulder DJ, Noble AJ, Justinich CJ, Duffin JM (May 2014). "A tale of two diseases: The history of inflammatory bowel disease". Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 8 (5): 341–8. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2013.09.009. PMID 24094598. S2CID 13714394.

- ^ Ginzburg L (May 1986). "Regional enteritis: Historical perspective". Gastroenterology. 90 (5): 1310–1. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(86)90419-1. PMID 3514360.

- ^ a b c d e f "Inflammatorisk tarmsjukdom, kronisk, IBD". internetmedicin.se (in Swedish). January 4, 2009. Archived from the original on August 20, 2010.

- ^ Hanauer SB, Sandborn W (March 2001). "Management of Crohn's disease in adults". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 96 (3): 635–43. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.3671_c.x (inactive November 2, 2024). PMID 11280528. S2CID 31219115.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ a b Pimentel M, Chang M, Chow EJ, Tabibzadeh S, Kirit-Kiriak V, Targan SR, et al. (December 2000). "Identification of a prodromal period in Crohn's disease but not ulcerative colitis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 95 (12): 3458–62. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03361.x. PMID 11151877. S2CID 2764694.

- ^ National Research Council (2003). "Johne's Disease and Crohn's Disease". Diagnosis and Control of Johne's Disease. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/10625. ISBN 978-0-309-08611-0. PMID 25032299. NBK207651. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- ^ Taylor BA, Williams GT, Hughes LE, Rhodes J (August 1989). "The histology of anal skin tags in Crohn's disease: an aid to confirmation of the diagnosis". International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 4 (3): 197–9. doi:10.1007/BF01649703. PMID 2769004. S2CID 7831833.

- ^ a b "What I need to know about Crohn's Disease". www.niddk.nih.gov. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Crohn Disease at eMedicine

- ^ a b c Podolsky DK (August 2002). "Inflammatory bowel disease". The New England Journal of Medicine (Submitted manuscript). 347 (6): 417–29. doi:10.1056/NEJMra020831. PMID 12167685. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ Mueller MH, Kreis ME, Gross ML, Becker HD, Zittel TT, Jehle EC (August 2002). "Anorectal functional disorders in the absence of anorectal inflammation in patients with Crohn's disease". The British Journal of Surgery. 89 (8): 1027–31. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02173.x. PMID 12153630. S2CID 42383375.

- ^ Ingle SB, Hinge CR, Dakhure S, Bhosale SS (May 16, 2013). "Isolated gastric Crohn's disease". World Journal of Clinical Cases. 1 (2): 71–73. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v1.i2.71. ISSN 2307-8960. PMC 3845940. PMID 24303469.

- ^ Greuter T, Piller A, Fournier N, Safroneeva E, Straumann A, Biedermann L, et al. (August 25, 2018). "Upper Gastrointestinal Tract Involvement in Crohn's Disease: Frequency, Risk Factors, and Disease Course". Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 12 (12): 1399–1409. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy121. ISSN 1873-9946. PMID 30165603.

- ^ Laube R, Liu K, Schifter M, Yang JL, Suen MK, Leong RW (February 2018). "Oral and upper gastrointestinal Crohn's disease". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 33 (2): 355–364. doi:10.1111/jgh.13866. ISSN 0815-9319. PMID 28708248.

- ^ Pimentel AM, Rocha R, Santana GO (March 7, 2019). "Crohn's disease of esophagus, stomach and duodenum". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 10 (2): 35–49. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v10.i2.35. ISSN 2150-5349. PMC 6422852. PMID 30891327.

- ^ Fix OK, Soto JA, Andrews CW, Farraye FA (December 2004). "Gastroduodenal Crohn's disease". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 60 (6): 985. doi:10.1016/S0016-5107(04)02200-X. PMID 15605018.

- ^ Antonelli E, Bassotti G, Tramontana M, Hansel K, Stingeni L, Ardizzone S, et al. (January 2021). "Dermatological Manifestations in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases". J Clin Med. 10 (2): 364. doi:10.3390/jcm10020364. PMC 7835974. PMID 33477990.

- ^ a b Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J (January 3, 2017). "Metastatic Crohn's Disease: An Approach to an Uncommon but Important Cutaneous Disorder". BioMed Research International. 2017: e8192150. doi:10.1155/2017/8192150. ISSN 2314-6133. PMC 5239966. PMID 28127561.

- ^ a b Beattie RM, Croft NM, Fell JM, Afzal NA, Heuschkel RB (May 2006). "Inflammatory bowel disease". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 91 (5): 426–432. doi:10.1136/adc.2005.080481. PMC 2082730. PMID 16632672.

- ^ Büller HA (February 1997). "Problems in diagnosis of IBD in children". The Netherlands Journal of Medicine (Submitted manuscript). 50 (2): S8–11. doi:10.1016/S0300-2977(96)00064-2. PMID 9050326. Archived from the original on August 28, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ O'Keefe SJ (1996). "Nutrition and gastrointestinal disease". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. Supplement. 220: 52–9. doi:10.3109/00365529609094750. PMID 8898436.

- ^ a b c Harbord M, Annese V, Vavricka SR, Allez M, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Boberg KM, et al. (March 2016). "The First European Evidence-based Consensus on Extra-intestinal Manifestations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease". Journal of Crohn's & Colitis. 10 (3): 239–254. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv213. PMC 4957476. PMID 26614685.

- ^ Greenstein AJ, Janowitz HD, Sachar DB (September 1976). "The extra-intestinal complications of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: a study of 700 patients". Medicine. 55 (5): 401–412. doi:10.1097/00005792-197609000-00004. PMID 957999.

- ^ Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Yu N (April 2001). "The prevalence of extraintestinal diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 96 (4): 1116–1122. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03756.x. PMID 11316157.

- ^ Harbord M, Annese V, Vavricka SR, Allez M, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Boberg KM, et al. (March 2016). "The First European Evidence-based Consensus on Extra-intestinal Manifestations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease". Journal of Crohn's & Colitis. 10 (3): 239–254. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv213. PMID 26614685.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Trikudanathan G, Venkatesh PG, Navaneethan U (December 2012). "Diagnosis and therapeutic management of extra-intestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease". Drugs. 72 (18): 2333–49. doi:10.2165/11638120-000000000-00000. PMID 23181971. S2CID 10078879.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Jose FA, Heyman MB (February 2008). "Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 46 (2): 124–133. doi:10.1097/MPG.0b013e318093f4b0. ISSN 0277-2116. PMC 3245880. PMID 18223370.

- ^ Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N (July 30, 2004). "The Gastrointestinal Tract". Robbins and Cotran: Pathologic Basis of Disease (7th ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Elsevier Saunders. p. 847. ISBN 978-0-7216-0187-8.

- ^ Loos E, Lemkens P, Poorten VV, Humblet E, Laureyns G (January 2019). "Laryngeal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease". Journal of Voice. 33 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.09.021. PMID 29605161. S2CID 4565046.

- ^ Hasegawa N, Ishimoto SI, Takazoe M, Tsunoda K, Fujimaki Y, Shiraishi A, et al. (July 2009). "Recurrent hoarseness due to inflammatory vocal fold lesions in a patient with Crohn's disease". The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. 118 (7): 532–5. doi:10.1177/000348940911800713. PMID 19708494. S2CID 8472904.

- ^ Li CJ, Aronowitz P (March 2013). "Sore throat, odynophagia, hoarseness, and a muffled, high-pitched voice". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 80 (3): 144–145. doi:10.3949/ccjm.80a.12056. ISSN 0891-1150. PMID 23456463. S2CID 31002546.

- ^ Lu DG, Ji XQ, Liu X, Li HJ, Zhang CQ (January 7, 2014). "Pulmonary manifestations of Crohn's disease". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (1): 133–141. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.133. ISSN 1007-9327. PMC 3886002. PMID 24415866.

- ^ Bernstein M, Irwin S, Greenberg GR (September 2005). "Maintenance infliximab treatment is associated with improved bone mineral density in Crohn's disease". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 100 (9): 2031–5. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50219.x. PMID 16128948. S2CID 28982700.