The Nun's Story (film): Difference between revisions

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Rozsaphile1 (talk | contribs) →Pre-production: Lowercase |

||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

With progress being made on the script, the production turned its attention to Europe, where the film was shot, and where cooperation with religious organizations was crucial. Producer [[Henry Blanke]] soon learned that the [[Catholic Church in Belgium]] were not impressed with the book, finding it injurious to religious vocations, and it would not cooperate with the production in any form.{{r|mpaa|p=37-38}} After recovering from an automobile accident, John Vizzard went to work on his European connections, hoping to convince [[Leo Joseph Suenens]], auxiliary bishop of [[Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Mechelen–Brussels|Mechelen]] to relinquish his objections. Father Leo Lunders helped facilitate these conversations.{{r|mpaa|p=40-48}} In September 1957, Lunders asked the Belgian Office of Warner Brothers who would be cast as Doctor Fortunati. Lunders objected to the proposals of [[Montgomery Clift]] and [[Raf Vallone]], suggesting someone older.{{r|mpaa|p=49}} Vizzard traveled to Europe in October 1957 to help with negotiations. At this point, Harold C. Gardiner became aware of the production and lent his enthusiasm and support. Together with Lunders, who soon was contracted as the film's ecclesiastical advisor, Vizzard won over Monsignor Suenens, but still needed to convince the Mother General of the [[Sisters of Charity of Jesus and Mary]] in Ghent.{{r|mpaa|p=50-64}} The Sisters provided a lengthy set of objections and their own version of the script. Many of these suggestions were in some way accounted for. For example, the Sisters did not want the film to feature the clickers that they typically used to signal each other. They worried that European audiences would find this strange or even comedic. Eventually the Sisters agreed to allow observation of their order and guidance for the production. They wanted their help to remain private and refused to appear on camera. With support growing, the cast and crew began to make their way to Europe for preparation and photography.{{r|mpaa|p=65-123}} |

With progress being made on the script, the production turned its attention to Europe, where the film was shot, and where cooperation with religious organizations was crucial. Producer [[Henry Blanke]] soon learned that the [[Catholic Church in Belgium]] were not impressed with the book, finding it injurious to religious vocations, and it would not cooperate with the production in any form.{{r|mpaa|p=37-38}} After recovering from an automobile accident, John Vizzard went to work on his European connections, hoping to convince [[Leo Joseph Suenens]], auxiliary bishop of [[Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Mechelen–Brussels|Mechelen]] to relinquish his objections. Father Leo Lunders helped facilitate these conversations.{{r|mpaa|p=40-48}} In September 1957, Lunders asked the Belgian Office of Warner Brothers who would be cast as Doctor Fortunati. Lunders objected to the proposals of [[Montgomery Clift]] and [[Raf Vallone]], suggesting someone older.{{r|mpaa|p=49}} Vizzard traveled to Europe in October 1957 to help with negotiations. At this point, Harold C. Gardiner became aware of the production and lent his enthusiasm and support. Together with Lunders, who soon was contracted as the film's ecclesiastical advisor, Vizzard won over Monsignor Suenens, but still needed to convince the Mother General of the [[Sisters of Charity of Jesus and Mary]] in Ghent.{{r|mpaa|p=50-64}} The Sisters provided a lengthy set of objections and their own version of the script. Many of these suggestions were in some way accounted for. For example, the Sisters did not want the film to feature the clickers that they typically used to signal each other. They worried that European audiences would find this strange or even comedic. Eventually the Sisters agreed to allow observation of their order and guidance for the production. They wanted their help to remain private and refused to appear on camera. With support growing, the cast and crew began to make their way to Europe for preparation and photography.{{r|mpaa|p=65-123}} |

||

The cast and crew included few if any Catholics. Fred Zinnemann was Jewish. Audrey Hepburn and Edith Evans were [[Christian Science|Christian Scientists]]. Robert Anderson was a Protestant, and Peggy Ashcroft was agnostic.<ref name="Zinnemann" /> Given the eventual support of most local religious organizations, the production was able to observe and participate in many real religious ceremonies and traditions. Before principal photography, the leading actresses spent time embedded in [[Assumptionists|Assumptionist]] |

The cast and crew included few if any Catholics. Fred Zinnemann was Jewish. Audrey Hepburn and Edith Evans were [[Christian Science|Christian Scientists]]. Robert Anderson was a Protestant, and Peggy Ashcroft was agnostic.<ref name="Zinnemann" /> Given the eventual support of most local religious organizations, the production was able to observe and participate in many real religious ceremonies and traditions. Before principal photography, the leading actresses spent time embedded in [[Assumptionists|Assumptionist]] convents in Paris. |

||

The production also corresponded regularly with Kathryn Hulme, the author of the source material. The Kathryn Hulme collection at Yale University contains 37 of these letters.<ref name="collection">{{cite journal |last1=May |first1=Anne |title=The Kathryn Hulme Collection |journal=The Yale University Library Gazette |volume=53 |issue=3 |pages=129–134 |jstor=40858678 |year=1979 }}</ref> To prepare for her role, Audrey Hepburn met with both Hulme and Marie Louise Habets, the inspiration for the novel and film. The three spent a considerable amount of time together, apparently becoming known as "The 3-H Club". Hepburn and Habets had some surprising similarities. Both had Belgian roots and had experienced personal trauma during World War II, including losing touch with their fathers and having their brothers imprisoned by Germans.<ref name="cath">{{cite journal |last=Campbell |first=Debra |title=The Nun's Story: Another Look at the Postwar Religious Revival |journal=American Catholic Studies |volume=119 |issue=Winter 2008 |pages=103–108 |jstor=44195197 |year=2008 }}</ref> Habets later helped nurse Hepburn back to health following her near-fatal horse-riding accident on the set of the 1960 film ''[[The Unforgiven (1960 film)|The Unforgiven]]''. |

The production also corresponded regularly with Kathryn Hulme, the author of the source material. The Kathryn Hulme collection at Yale University contains 37 of these letters.<ref name="collection">{{cite journal |last1=May |first1=Anne |title=The Kathryn Hulme Collection |journal=The Yale University Library Gazette |volume=53 |issue=3 |pages=129–134 |jstor=40858678 |year=1979 }}</ref> To prepare for her role, Audrey Hepburn met with both Hulme and Marie Louise Habets, the inspiration for the novel and film. The three spent a considerable amount of time together, apparently becoming known as "The 3-H Club". Hepburn and Habets had some surprising similarities. Both had Belgian roots and had experienced personal trauma during World War II, including losing touch with their fathers and having their brothers imprisoned by Germans.<ref name="cath">{{cite journal |last=Campbell |first=Debra |title=The Nun's Story: Another Look at the Postwar Religious Revival |journal=American Catholic Studies |volume=119 |issue=Winter 2008 |pages=103–108 |jstor=44195197 |year=2008 }}</ref> Habets later helped nurse Hepburn back to health following her near-fatal horse-riding accident on the set of the 1960 film ''[[The Unforgiven (1960 film)|The Unforgiven]]''. |

||

Revision as of 17:41, 1 October 2024

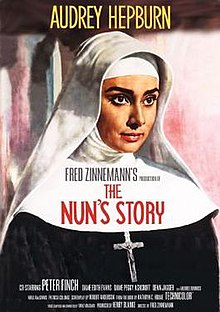

| The Nun's Story | |

|---|---|

Original film poster | |

| Directed by | Fred Zinnemann |

| Screenplay by | Robert Anderson |

| Based on | The Nun's Story 1956 novel by Kathryn Hulme |

| Produced by | Henry Blanke |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Franz Planer |

| Edited by | Walter Thompson |

| Music by | Franz Waxman |

Production company | Warner Bros. |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 152 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.5 million[1] |

| Box office | $12.8 million[1] |

The Nun's Story is a 1959 American drama film directed by Fred Zinnemann and starring Audrey Hepburn, Peter Finch, Edith Evans, and Peggy Ashcroft. The screenplay was written by Robert Anderson, based on the popular 1956 novel of the same name by Kathryn Hulme. The film tells the life of Gabrielle Van Der Mal (Hepburn), a young woman who decides to enter a convent and make the many sacrifices required by her choice.

The film is a relatively faithful adaptation of the novel, which was based on the life of Belgian nun Marie Louise Habets. Latter portions of the film were shot on location in the Belgian Congo and feature Finch as a cynical but caring surgeon.[2] The film was a financial success and was nominated for eight Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Actress for Hepburn.[1][3]

Plot

Gabrielle "Gaby" Van Der Mal (Audrey Hepburn), whose father, Hubert (Dean Jagger), is a prominent surgeon in Belgium, enters a convent of nursing sisters in the late 1920s, hoping to serve in the Belgian Congo. After receiving the religious name of Sister Luke, she undergoes her postulancy and novitiate which foreshadow her future difficulties with the vow of obedience. She takes her first vows and is sent to the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp.

After passing her courses with high marks, along with some spiritual conflict, she silently resists the Mother Superior's request to purposely fail her final exam as a proof of her humility. Despite finishing fourth in her class of 80, she is not assigned to the Congo but sent to a European mental hospital, where she assists with the most difficult and violent cases, wasting her tropical medicine skills. A violent patient with psychosis (Colleen Dewhurst) tricks Sister Luke into opening the cell door in violation of the rules. She attacks Sister Luke, who barely escapes and once again faces the shame of her disobedience.

Eventually she takes her solemn vows, and she is sent to her long-desired posting in the Congo. Once there, she is disappointed that she will not be nursing the natives, but will instead work in a segregated whites/European patient hospital. She develops a strained but professional relationship with the brilliant, atheistic surgeon there, Dr. Fortunati (Peter Finch). Eventually, the work strains and spiritual struggles cause her to succumb to tuberculosis. Fortunati, not wanting to lose a competent nurse and sympathetic to her desire to stay in the Congo, engineers a treatment plan that allows her to remain there rather than having to convalesce in Europe.

After Sister Luke recovers and returns to work, Fortunati is forced to send her to Belgium as the only nurse qualified to accompany a VIP who has become mentally unstable. She spends an outwardly reflective but inwardly restless period at the motherhouse in Brussels before the superior general gives her a new assignment. Due to the impending war in Europe, she cannot return to the Congo, and she is assigned as a surgical nurse at a hospital near the Dutch border.

While at her new assignment, Sister Luke's struggle with obedience becomes impossible for her to sustain as she is repeatedly forced into compromises to cope with the reality of the Nazi occupation, including that they have killed her father. No longer able to continue as a nun, she requests, and she is granted a dispensation from her vows. She is last seen changing into lay garb and exiting the convent through a back door.

Cast

- Audrey Hepburn as Sister Luke (Gabrielle "Gaby" Van Der Mal)

- Peter Finch as Dr. Fortunati

- Edith Evans as Rev. Mother Emmanuel

- Peggy Ashcroft as Mother Mathilde

- Dean Jagger as Dr. Hubert Van Der Mal

- Mildred Dunnock as Sister Margharita

- Beatrice Straight as Mother Christophe

- Patricia Collinge as Sister William

- Rosalie Crutchley as Sister Eleanor

- Ruth White as Mother Marcella

- Barbara O'Neil as Mother Didyma

- Margaret Phillips as Sister Pauline

- Patricia Bosworth as Simone

- Colleen Dewhurst as "Archangel Gabriel"

- Stephen Murray as Chaplain (Father Andre)

- Lionel Jeffries as Dr. Goovaerts

- Niall MacGinnis as Father Vermeuhlen

- Eva Kotthaus as Sister Marie

- Molly Urquhart as Sister Augustine

- Dorothy Alison as Sister Aurelie

- Richard O'Sullivan as Pierre Van Der Mal (uncredited)

- Jeanette Sterke as Louise Van Der Mal

- Errol John as Illunga

- Diana Lambert as Lisa

- Orlando Martins as Kalulu

Production

Pre-production

Warner Brothers was in touch with the Production Code Office as early as March 23, 1956, regarding a possible film adaptation of The Nun's Story. Warners provided Jack Vizzard of the Production Code Office with a 20-page synopsis of the novel, which had yet to be published.[4] Vizzard became one of the production's early allies. The first step of development was domestic approval, ensuring that the film could be released in the United States. Vizzard initially suggested only two mandatory changes. In particular he objected to the scene in which Sister Luke's clothes are torn off by a mental patient passing as the Archangel Gabriel and a discussion of anal suppositories. More generally Vizzard wondered if the film's themes might alienate Catholics.[4]: 22

The novel was published on June 1, 1956, to great acclaim. Although the book was popular among devout followers of many religions, it proved somewhat divisive: Some praised its intimate and empathetic view of religious conviction, and others worried that it might discourage potential postulants. One vocal proponent was Harold C. Gardiner, the literary editor of the Jesuit Magazine America.[5]

On September 12, 1956, Columbia Pictures also reached out to the Production Code Office regarding The Nun's Story. The Production Code Office replied by forwarding the same memo that had been sent to Warners with an additional postscript warning of religious disillusionment.[4]: 23-33 Eventually Warners secured the rights to the book, and Robert Anderson and Fred Zinnemann signed to write and direct the film. Zinnemann had been introduced to the source material by actor Gary Cooper, and he was immediately interested in an adaptation. Reportedly there was little traction from studios until Audrey Hepburn expressed her interest.[6]

On August 14, 1957, Warners submitted the script for The Nun's Story to the Production Code Office. It was reviewed in conference with Monsignor John Devlin, the head of the Los Angeles chapter of the National Legion of Decency. One conclusion was that "The present script, although being substantially acceptable, lacked showing some of the true and proper joy of religious life. It contains a somberness of mood that approaches the Jansenistic. An effort will be made to supply the one and eliminate the other." Some specific criticisms were entered, and it was suggested that an effort be made to show that Gabrielle enters religious life with a false ideal and that she is essentially not cut out to be a nun, a common Christian framing of the source material.[4]: 34-35

With progress being made on the script, the production turned its attention to Europe, where the film was shot, and where cooperation with religious organizations was crucial. Producer Henry Blanke soon learned that the Catholic Church in Belgium were not impressed with the book, finding it injurious to religious vocations, and it would not cooperate with the production in any form.[4]: 37-38 After recovering from an automobile accident, John Vizzard went to work on his European connections, hoping to convince Leo Joseph Suenens, auxiliary bishop of Mechelen to relinquish his objections. Father Leo Lunders helped facilitate these conversations.[4]: 40-48 In September 1957, Lunders asked the Belgian Office of Warner Brothers who would be cast as Doctor Fortunati. Lunders objected to the proposals of Montgomery Clift and Raf Vallone, suggesting someone older.[4]: 49 Vizzard traveled to Europe in October 1957 to help with negotiations. At this point, Harold C. Gardiner became aware of the production and lent his enthusiasm and support. Together with Lunders, who soon was contracted as the film's ecclesiastical advisor, Vizzard won over Monsignor Suenens, but still needed to convince the Mother General of the Sisters of Charity of Jesus and Mary in Ghent.[4]: 50-64 The Sisters provided a lengthy set of objections and their own version of the script. Many of these suggestions were in some way accounted for. For example, the Sisters did not want the film to feature the clickers that they typically used to signal each other. They worried that European audiences would find this strange or even comedic. Eventually the Sisters agreed to allow observation of their order and guidance for the production. They wanted their help to remain private and refused to appear on camera. With support growing, the cast and crew began to make their way to Europe for preparation and photography.[4]: 65-123

The cast and crew included few if any Catholics. Fred Zinnemann was Jewish. Audrey Hepburn and Edith Evans were Christian Scientists. Robert Anderson was a Protestant, and Peggy Ashcroft was agnostic.[6] Given the eventual support of most local religious organizations, the production was able to observe and participate in many real religious ceremonies and traditions. Before principal photography, the leading actresses spent time embedded in Assumptionist convents in Paris.

The production also corresponded regularly with Kathryn Hulme, the author of the source material. The Kathryn Hulme collection at Yale University contains 37 of these letters.[7] To prepare for her role, Audrey Hepburn met with both Hulme and Marie Louise Habets, the inspiration for the novel and film. The three spent a considerable amount of time together, apparently becoming known as "The 3-H Club". Hepburn and Habets had some surprising similarities. Both had Belgian roots and had experienced personal trauma during World War II, including losing touch with their fathers and having their brothers imprisoned by Germans.[8] Habets later helped nurse Hepburn back to health following her near-fatal horse-riding accident on the set of the 1960 film The Unforgiven.

Zinnemann also continued his usual practices of collaborating with the film's writer on the second draft of the screenplay (but not receiving a writing credit) and meeting with each major actor for an in-depth discussion of his or her character.[9]

Patricia Bosworth learned that she was pregnant on the same day that she was cast as Simone. She underwent an underground abortion immediately before leaving for Rome and began to hemorrhage while on the plane. Production was delayed as she recovered.[10]

The cast was completed by Colleen Dewhurst, making her first screen appearance and Renée Zinnemann, the wife of the director who played the assistant of the Mother Superior (Edith Evans).[11][6]

Principal photography

The film was shot partially in the then Belgian Congo, now Democratic Republic of the Congo, with production based in then Stanleyville, now Kisangani. Some scenes were shot in Yakusu, a nearby center of missionary and medical activity where cast and crew met the famous missionary Stanley George Browne.[12] Fred Zinnemann had originally intended to film only the African scenes in color, with Europe rendered in stark black and white.[13] There was originally a scene towards the end of the film depicting three men endangered by quicksand and rapidly rising water, but it was never filmed due to adverse conditions.[9]

Interior scenes for the Belgian portions of the film were shot in Rome at Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia and Cinecittà on sets designed by Alexandre Trauner.[6] Extras for these scenes were recruited from the ballet corps of the Rome Opera company. Zinnemann wanted actors who were capable of precise and coordinated movement.[13]

Belgian exteriors were shot on location in Bruges, but the novel was set in Ghent.[6]

Post-production

According to Zinnemann, composer Franz Waxman's dislike of the Catholic Church was a conspicuous influence on early drafts of the score. This is part of the reason why the final scene has no score, an uncommon stylistic choice for the era.[14] Regardless of Waxman's work, Zinnemann had always wanted the film to end in silence.[13][9]

The original theatrical trailer for the film contains a brief shot of Gabrielle and her father sitting at a cafe. The shot is an excerpt from a scene that was removed from the final cut. The scene is alluded to in the final film when Dr. Van Der Mal mentions a restaurant reservation at the beginning of the film. Zinnemann removed the scene because he felt it was redundant and hindered the pace of the film's opening.[9]

Release

The film premiered at Radio City Music Hall on June 18, 1959.[1][15] In April 1959, the film was screened at the Paris Warner Brothers office for nuns and religious officials who had helped with the film's preparations. Despite mostly not speaking English, the audience was reportedly captivated.[4]: 143-145 The film premiered in Italy on October 10, 1959, at Cinema Fiammetta with Audrey Hepburn and Mel Ferrer in attendance.[16]

The Nun's Story received its first official North American DVD release on April 4, 2006.

Hulme's and Habets' relationship was the subject of The Belgian Nurse, a radio play by Zoe Fairbairns, first broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on January 13, 2007.[17]

Reception

On Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 85% based on reviews from 20 critics.[18]

The Nun's Story was a major box office success. Produced on a budget of $3.5 million, it grossed $12.8 million at the domestic box office,[1] earning $6.3 million in theatrical rentals in the U.S.[19] The Nun's Story was considered, for a time, to be the most financially successful of Hepburn's films and the one the actress often cited as her favorite.

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times praised The Nun's Story as an "amazing motion picture" and "a thoroughly tasteful film," writing that "Mr. Zinnemann has made this off-beat drama describe a parabola of spiritual afflatus and deflation that ends in a strange sort of defeat. For the evident point of this experience is that a woman gains but also loses her soul, spends and exhausts her devotion to an ideal she finds she cannot hold."[15]

The National Legion of Decency classified the film as A-II, "Morally Unobjectionable for Adults and Adolescents" with the observation that, "This entertainment film, noble, sensitive, reverent, and inspiring in its production, is a theologically sound and profound analysis of the essential meaning of religious vocation through the story of a person who objectively lacked the fundamental qualification for an authentic religious calling. If the film fails to capture the full meaning of religious life in terms of its spiritual joy and all-pervading charity, this must be attributed to the inherent limitations of a visual art."[20]

According to correspondences in the Kathryn Hulme collection at Yale University, both Mary Louise Habets and Kathryn Hulme were pleased with the film and its success.[7]

The film was nominated for Academy Awards in eight categories, but received no Oscars in the year that Ben-Hur swept the awards. Fred Zinnemann was honored as best director by both the New York Film Critics and the National Board of Review.

In 2020 America again praised the film, celebrating it as Hepburn's most overlooked work and contrasting it with some of her less devout roles. There is no mention of the magazine's late literary editor Father Gardiner and his support for the source material and involvement in the adaptation.[21]

Accolades

References

- ^ a b c d e Box Office Information for The Nun's Story. The Numbers. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- ^ "The Nun's Story (1959)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- ^ "The 32nd Academy Awards (1960) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "THE NUN'S STORY, 1959". Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Sullivan, Rebecca (2005). Visual habits : nuns, feminism, and American postwar popular culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 95–123. ISBN 0802039359.

- ^ a b c d e Zinnemann, Fred (1992). A life in the movies : an autobiography. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. ISBN 0-684-19050-8.

- ^ a b May, Anne (1979). "The Kathryn Hulme Collection". The Yale University Library Gazette. 53 (3): 129–134. JSTOR 40858678.

- ^ Campbell, Debra (2008). "The Nun's Story: Another Look at the Postwar Religious Revival". American Catholic Studies. 119 (Winter 2008): 103–108. JSTOR 44195197.

- ^ a b c d Zinnemann, Fred; Nolletti Jr., Alfred (1994). "Conversation with Fred Zinnemann". Film Criticism. 18/19 (3/1): 7–29. JSTOR 44076035.

- ^ NPR Staff (January 28, 2017). "Renowned Biographer Patricia Bosworth Writes a Chapter from Her Own Life". NPR. Washington, D.C.: National Public Radio, Inc. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ^ "The Nun's Story (1959) - Notes". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- ^ "Wellcome Library for the History of Medicine & Understanding". Leprosy History. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ a b c Zinnemann, Fred; Neve, Brian (1997). "A Past Master of His Craft: An Interview with Fred Zinnemann". Cinéaste. 23 (1): 15–19. JSTOR 41688984.

- ^ Phillips, Gene (1999). "Waxing Silent". Film Comment. 35 (3): 2. JSTOR 43455378.

- ^ a b Crowther, Bosley (19 June 1959). "The Dedicated Story of a Nun; Audrey Hepburn Stars in Music Hall Film Kathryn Hulme Novel Sensitively Depicted". New York Times. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ "Audrey Hepburn e Mel Ferrer entrano al cinema Fiammetta, intorno una gran folla - campo medio". Archivio Luce. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ "Zoe Fairbairns - The Belgian Nurse". BBC Radio 4 Extra. BBC. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ "The Nun's Story (1959)". Rotten Tomatoes. 18 July 1959. Retrieved 2024-05-27.

- ^ "1959: Probable Domestic Take", Variety, January 6, 1960 p 34.

- ^ Motion Pictures Classified by National Legion of Decency: February, 1936 - October, 1959. New York: National Legion of Decency. 1959. p. 294.

- ^ Little, Nadra (January 24, 2020). "'The Nun's Story': Revisiting Audrey Hepburn's most overlooked film". America: The Jesuit Review. No. February 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ "The 32nd Academy Awards (1960) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-21.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1960". BAFTA. 1960. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ "12th DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "The Nun's Story – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "2nd Annual GRAMMY Awards". Grammy.com. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ "1959 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1959 New York Film Critics Circle Awards". New York Film Critics Circle. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Awards Winners". wga.org. Writers Guild of America. Archived from the original on 2012-12-05. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

External links

- 1959 films

- 1959 drama films

- 1950s American films

- 1950s English-language films

- American drama films

- English-language drama films

- Films about Catholic nuns

- Films about nurses

- Films based on American novels

- Films directed by Fred Zinnemann

- Films scored by Franz Waxman

- Films set in the 1920s

- Films set in 1930

- Films set in Belgian Congo

- Films set in Belgium

- Films set in convents

- Films shot in Bruges

- Religious drama films

- Warner Bros. films